Ways of Knowing the Body, Bodily Ways of Knowing

Peter A. Martens

KEYWORDS: performance, analysis, motion capture, rhythm perception

ABSTRACT: The central role of the body in producing music is hardly debatable. Likewise, the body has always played at least an implicit role in music theory, but has only been raised as a factor in music analysis relatively recently. In this essay I present a brief update of the body in music analysis via case studies, situated in the disciplines of music theory and music cognition, broadly construed. This current trajectory is part of a broader shift away from the musical score as the sole focus for analysis, which admittedly—though, in my view, delightfully—raises a host of challenging epistemological questions surrounding the interaction of performer (production) and listener (perception). While the concomitant research methodologies and technologies may be unfamiliar to scholars trained in humanities disciplines, I advocate for a full embrace of these approaches, either by individual researchers or in the form of cross-disciplinary collaboration.

Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory

[1] The impulse to include the body in music analysis is not particularly new, even within the modern field of music theory. Sixteen years ago, the lead Journal of Music Theory article by Andrew Mead (1999) advocated for “Bodily Hearing,” and since that time, essay collections edited by John Rink (2002) and the two Music and Gesture volumes edited by Anthony Gritten and Elaine King (2006 and 2011) have contained contributions by notable self-identified music theorists, whose focus is not just metaphorical musical gesture, but physical gesture as well.

[2] Not that the historical discipline has ever entirely ignored the body’s role in producing music—after all, the Greek lichanos (index finger) is used in early treatises to denote the second-highest position in tetrachords, the term drawn from the physical means by which these scale-steps were executed on a 7-stringed lyre. But some strands of theorizing or analyzing can be seen as ignoring the intuition or common-sense tenet that any “beholder” of music gleans a great quantity of information from even cursory attention to human movement. Consider the fifteen dots moving in two dimensions that comprise the Biomotion lab’s “Walker” demo.

[3] We can instantly identify the basic action taking place; by manipulating the sliders at the upper left of the demo we can alter the dots’ movements in ways that allow the viewer to infer more specific physical attributes, gender, and even emotional states. For example, if we move the sliders to the extreme positions of Male, Heavy, Relaxed, and Happy, we may recognize the gait of a large fellow who just gave a well-received presentation to the Society for Music Theory, and who is feeling pretty good about himself.

[4] Thus, even if we avoid taking account of the performing body for a particular analytical goal or in a particular analytical context, the body must be considered in order to make the avoidance explicit and justified. In most cases, however, analysis will benefit from integrating the body in precise ways; in this short essay I advocate for just that, by reviewing two current methods for exploring the music-body pairing.

[5] I begin with a technique that does not engage with visible bodies in motion per se, but that focuses on the artifacts of those bodies in the form of precise audio timings. A recent refinement of this general approach appears in Mitch Ohriner’s 2012 Music Theory Online article on grouping hierarchy in Chopin’s mazurkas (Example 1).

[6] Ohriner uses these data as evidence for differing conceptions of phrase structure on the part of the two performers. The fourth measure shown in the example is treated by Frederic Chiu as a mid-phrase slowing of the melodic rhythm, but with the potential phrase break undercut as Chiu accelerates the underlying pulse. By contrast, Vladimir Ashkenazy realizes the melody’s boundary-creating potential by emphasizing the slower melodic durations with a simultaneous slowing of the underlying pulse. It is a compelling example of a theorist/analyst treating performances themselves as analyses of a work, and in the present context we may leap to a logical next question: exactly what (gestural) means did the performers use to express these differing (musical) conceptions? Did their gestures actually differ? Does it matter if their gestures differed?

[7] A leading technique of recording physical gesture visually for analysis purposes is called Motion Capture (or MoCap; cf. Menache 2010, especially Chapter 1). This technology allows for the precise recording and measurement of movement in three dimensions. It has become indispensable to the motion picture and animation industries, and even at a medium-sized state university such as Texas Tech University there are currently four motion capture installations spread across different academic divisions—Psychology, Kinesiology & Sport Management, Mechanical Engineering, and the Library Informatics Media Lab—none, notably, located in the College of Visual and Performing Arts.

[8] Both audio timing profiles and motion capture quantify physical movement and represent it precisely for post-hoc study. For music analysis, both methods share strengths and weaknesses with traditional music notation. Audio timing data of course ignore visual information, often because none exists. Visual information is central to motion capture, but while it can capture the subtle inclination or shake of a pianist’s head, it cannot capture a simultaneous sublime expression on the pianist’s face.

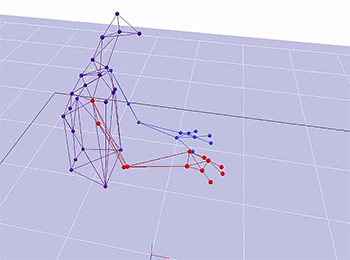

Example 2. Two motion-capture performances of “The Cowherd’s Song” by Edvard Grieg

(click to watch videos)

[9] As an example of these strengths and limitations, here are two short motion capture-generated animations from a recent study done on my campus by a multidisciplinary research group. You’ll see a pianist’s waist-up motion capture skeleton, recorded using 46 sensors. Example 2 shows two video performances by the same pianist of the same short piece, “The Cowherd’s Song” by Edvard Grieg. For the first performance the pianist was instructed to “think about performing the piece as correctly as you can.” For the second, the instructions were to “just think about enjoying yourself while playing the piece.”

[10] Eight paired performances of this type were shown to musician and non-musician subject groups while brain activation was recorded via fMRI. Subjects simultaneously answered a set of twelve questions about each performance that pertained to the engaging quality, emotional content, appropriateness of gesture, and tempo of the performance, as well as the gender of the performer.

[11] The two most interesting findings were that 1) the brain activation patterns for all subjects showed differences between correct and enjoyable performances, and 2) the pianists’ performance condition was evident quickly and consciously to musicians but not to non-musicians, based on the speed with which they responded to questions (Westney et al. 2015). Once again we see the remarkable amount of information that can be gleaned from stick figures—not simply physical characteristics such as size, gender, and age, but also emotive and performative mindsets.

[12] This type of data can be used in many ways. From this single data set, my pianist colleague has applied the work to his own pedagogy, the neuroscientist in the group is exploring how mirror neurons might be involved in conveying mood and attitude, the philosopher in the group has drawn observations about how music means, and lastly I am working to identify what gestures Grieg has essentially composed into the score, and by contrast which gestures are chiefly expressive in origin.(1)

[13] By way of conclusion, let me shift the focus from the performer’s body to the listener or analyst’s body. Please revisit the contrast between the Frederic Chiu and Vladimir Ashkenazy performances, and the three notationally equal durations of Chopin’s m. 4, as reproduced in Example 1 above. Research over the past ten years has shown that listeners perceive a set of three notes of equal duration as more equal if they are played with a small ritardando (e.g. Sadakata, Desain, and Honing 2006). This seems to be especially true when listeners are engaged physically with the rhythm, for instance by simply tapping along with a foot or a hand. Therefore, even though Chiu objectively slows down m. 4, we may have experienced little or no tempo change while we listened. Indeed, the same might be true for the performer himself; he was certainly engaged physically, and so may not have intended to slow down or noticed that he had done so.

[14] Current research seems to be telling us that performers and listeners are frequent accomplices in such rhythmic fictions (Honing 2013). In order for us as analysts to avoid inferring things that were not intended or are not perceptible, then, we might begin by engaging physically with the performance ourselves, putting into practice the increasingly familiar concept of “embodied cognition.” But this small example broadens out to a host of critical questions. What aspects of the performing body do we analyze? It is easy enough, conceptually, to jettison notated scores as the sole objects for analysis and principal bearers of musical meaning. As a discipline, however, we are perhaps still at the stage of vetting precise forms for these kinetic and kinesthetic data. Does the information found in objective timing profiles (as in Example 1) or in audio waveforms best capture the performing body? Is performers’ self-reportage reliable? If the listener is the ultimate arbiter of musical communication, are questionnaire responses inferior to physical responses simply because the latter approach uses bodies in motion to understand bodies in motion? In either case, do we prefer descriptions drawn from often-unique individual responses to the statistical power of group response means? And once we throw open the floodgates of subjectivity in any of these ways, does the ontology of the musical work disappear under countless layers of context?

[15] We music theorists are not shy about arguing methodology, from familiar brickbats such as the assumptions of recursion in hierarchical analysis or arbitrary segmentation procedures in post-tonal analysis to more recent gender- or culture-based discussions. I would argue that in general, however, our debates focus on the “how” of analysis, while we still largely take the “what” for granted. The research paradigms that I’ve mentioned or alluded to above remain most at home in foreign fields—music cognition being the least distant—that have a very different approach to the “what” of analyzing music, simply because their goal is not primarily to understand music. But for those of us who do embrace that notion as our primary goal, to what degree can we understand music without understanding basic cognition, language learning, or reflexive motor routines?

[16] If, as a field, we are committed to either knowing the body or knowing by means of the body, or both—acknowledging that one cannot be an expert in all fields—we, as individual scholars, need to establish inter- and cross-disciplinary research partnerships to expand our methodological horizons. In doing so we will have to overcome our own methodological inertia—our disciplinary reluctance, or, perhaps more charitably, our structural disciplinary incapacity to engage in collaborative research outside the confines of the humanities.

Peter A. Martens

Texas Tech University School of Music

Box 42033

Lubbock, TX 79409

peter.martens@ttu.edu

Works Cited

Gritten, Anthony and Elaine King, eds. 2006. Music and Gesture. Ashgate Press.

—————. 2011. New Perspectives on Music and Gesture. Ashgate Press.

Honing, Henkjan. 2013. “Structure and Interpretation of Rhythm in Music” In The Psychology of Music, 3rd ed. (D. Deutsch, ed.). 369-404.

Mead, Andrew. 1999. “Bodily Hearing: Physiological Metaphors and Musical Understanding.” Journal of Music Theory 43(1): 1–19.

Menache, Alberto. 2010. Understanding Motion Capture for Computer Animation. 2nd ed. Morgan Kaufmann Press.

Ohriner, Mitchell S. 2012. “Grouping Hierarchy and Trajectories of Pacing in Performances of Chopin’s Mazurkas.” Music Theory Online 18.1.

Rink, John, ed. 2002. Musical Performance: A Guide to Understanding. Cambridge University Press.

Sadakata, Makika, Peter Desain and Henkjan Honing. 2006. “The Bayesian Way to Relate Rhythm Perception and Production.” Music Perception 23(3): 269-288.

Westney, William, Cynthia M. Grund, Jesse Latimer, Amy Cloutier, James Yang, Michael O’Boyle, Jiancheng Hou and Dan Fang. 2015. “Musical Embodiment and Perception: Performances, Avatars and Audiences.” SIGNATA Annales des Sémiotique / Annals of Semiotics 6: 355–83.

Footnotes

1. This undertaking is made more challenging, but also more interesting, due to the existence of Grieg’s own audio recordings of his music, in which the composer treats time very freely by modern standards, and thus likely may have employed gestures very different from those of modern pianists.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2016 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

6727