Review of Carl Schachter, The Art of Tonal Analysis: Twelve Lessons in Schenkerian Theory, ed. Joseph N. Straus (Oxford University Press, 2016)

David Temperley

KEYWORDS: Schenkerian analysis, linear progressions, key structure

Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory

[1] This collection of lectures from Carl Schachter’s final seminar at CUNY is a fitting capstone to his distinguished career as a music theorist. Each of the twelve lectures centers on an analytical exploration of one or two pieces, including works by Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Chopin; the book ends with a “Q and A” with students of the seminar. As Schachter is one of the most well-known advocates of Schenkerian theory, it is no surprise that the analyses reflect a Schenkerian perspective. But along the way, they touch on many other topics: other aspects of the works in question (rhythm, motive, form, performance); other pieces with similar features; biographical anecdotes about composers, Schenker, and Schachter himself; and matters still further afield, such as the Acoustical Society of America’s conventions for labeling pitches. The lectures assume a basic knowledge of Schenkerian theory—for example, there is no explanation for how to read a Schenkerian graph—but clearly an effort has been made to organize them in a pedagogically useful way, starting with basic concepts (e.g. the linear progression) and fairly small-scale observations and working up to larger, more complex structures.

[2] No one would call me a Schenkerian, and I have sometimes been quite critical of the Schenkerian approach (Temperley 2007 and 2011). But I have always felt that the most persuasive and compelling case for the theory was found in Carl Schachter’s work. So I had high hopes for this book, and I was not disappointed. All of the virtues of Schachter’s writing—its unpretentious eloquence, musical insight, and contagious enthusiasm—come through here as clearly as ever. As one would expect, too, the book makes a strong argument for the value and power of Schenkerian analysis. But the book also reinforced some of my doubts and concerns about the Schenkerian approach. In particular, the Schenkerian focus on high-level linear and contrapuntal features of a piece can cause other aspects—aspects that should surely be considered part of tonal analysis—to be underemphasized, if not completely ignored. Schachter (in this book and elsewhere) makes some efforts to address this problem, but it remains very much present. In what follows, I expand on these points, and offer some thoughts about other aspects of the book.

* * *

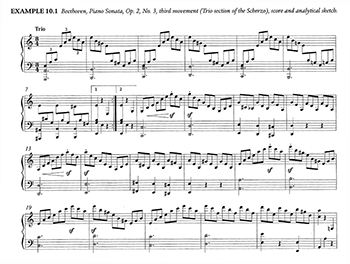

Example 1. Example 10.1 of ATA, just measures 1–24 (the whole of page 188)

(click to enlarge)

[3] A number of the discussions in The Art of Tonal Analysis (hereafter ATA) represent Schenkerian analysis at its best. Using Schenkerian graphs or sometimes just annotated scores, Schachter draws our attention to linear patterns and large-scale harmonic motions that are audible and compelling, and help us make sense of the music. A case in point is his analysis of the trio of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata op. 2 no. 3 (pages 187–91), shown here in Example 1. Schachter first suggests that we view the bass of the first phrase as moving from the A of measure 1 to the ![]()

[4] It is sometimes claimed that a linear progression must connect two chord-tones of a harmony that is being prolonged. Schachter endorses this view at the very beginning of the book (1), and sometimes invokes it as a reason for choosing one analysis over another (5, 93). Elsewhere, however, he points out linear motives that clearly do not meet this criterion. This is most notable in his analysis of the Adagio of Haydn’s Symphony No. 99. The primary motive in the analysis is a descending fourth, which occurs in various guises and transposition levels, either as B–A–G–

Example 2. Example 5.1 of ATA (page 90), just the fourth system (measures 16–20)

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. (A) Chopin, Prelude No. 12 in

(click to enlarge)

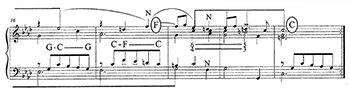

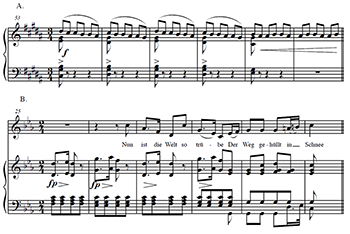

[5] Along these lines, I have suggested elsewhere (Temperley 2011) that it is useful to think of linear progressions and other Schenkerian concepts as schemata, in the sense proposed by Gjerdingen (2007). A schema is a conventional pattern that is defined by a cluster of features, and that may be invoked with varying degrees of strength or typicality. An advantage of this view is that it allows multiple, overlapping patterns–not in a conflicting, “either/or” relationship (to use Schachter’s own phrase [1990]), but coexisting within the same analysis. There are a number of points in ATA where I think this perspective would be helpful. In a Handel Courante, Schachter analyzes the cadence at the end of the first half as shown in Example 2, explaining the apparent harmonic changes within measures 18–19 as linear elaborations of a cadential V (95). While this analysis is plausible, surely the third beat of measure 18 is also serving a harmonic function—acting as a pre-dominant chord (iiø![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

[6] Despite their Schenkerian focus, Schachter’s discussions also consider many other aspects of the pieces in question. Issues of rhythm and meter arise in several analyses (3, 75, 80, 118), and the whole of Chapter 10 is devoted to this topic. Schachter also makes a number of valuable suggestions about performance, sometimes tied in with Schenkerian analysis (73, 77), sometimes not (148, 194–95). A discussion of how to perform the dotted eighths in Chopin’s E-major Prelude takes us into historical debates (C. P. E. Bach versus Quantz), documentary evidence (manuscripts and editions), and a brief look at a little-known variation by Chopin with striking similarities to the prelude. In a discussion of the Adagio of Mozart’s Violin Sonata K. 481, we learn about quatrain form (a very useful term that I had not encountered before), consider how a passage can function as both a codetta and a retransition, and explore a narrative interpretation of the piece as an interaction between a “passionate” violin and a “chaste and innocent” piano. This is just a small sample of the thoughtful and stimulating observations that appear throughout the book, on all manner of musical topics.

[7] I asserted earlier that Schenkerian analysis sometimes neglects important aspects of tonal structure. The aspects that I have in mind relate, in particular, to the concept of key. A tonal piece typically begins in its main key and then moves to one or more secondary keys before returning to the tonic. Within these secondary key sections, there may be still more local suggestions of other keys, creating a hierarchical structure, which I will simply call key structure. Another important aspect of key is relations between keys, which can be close or distant. A piece may take us on a journey through a number of secondary keys, understood both as “moves” from one key to the next—which may be small or large—and also in relation to the larger tonic. Also relevant is the issue of how keys are established or implied, which can be of great subtlety and interest. (See Temperley 2006 for further discussion of these issues.) To my mind, key structure is hugely important; it is largely this that allows a tonal piece to convey a large-scale sense of motion and drama. In Schenkerian analysis, key structure often receives little attention. The high-level prolongational events of a Schenkerian graph do sometimes correspond to key sections, which may give the impression that Schenkerian theory in some way includes or subsumes key analysis. But it does not; a prolonged harmony need not be a key section (the V of the Ursatz almost never is), and a key section may not correspond to a high-level prolonged harmony. Thus Schenkerian analysis not only neglects key structure but runs the risk of obscuring it, by asserting a kind of hierarchical structure that is superficially similar but actually quite different.

Example 4. Example 6.17 of ATA (page 122 in its entirety)

(click to enlarge)

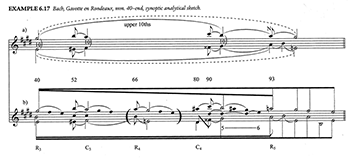

[8] It may seem odd to raise this issue here, since Schachter has in fact done more than most Schenkerians to acknowledge the importance of key structure. In his article “Analysis by Key” (1987), he concedes the neglect of key in Schenker’s own writings, acknowledges the independence of key structure from prolongational structure, and examines the interaction between these structures in a number of works. In ATA, too, Schachter sometimes seems to want to give more importance to key than Schenkerian theory would normally allow. In his analysis of the final section of the Rondeau of Bach’s E major Violin Partita (Example 4), the events of the high-level graph seem to indicate the key sections (tonic chords and their dominants); notably, the final descent of the Urlinie, included in the lower graph, is omitted in the upper one (though the return to E major in measures 64–72 is also omitted). In analyzing the Scherzo of Schubert’s

Example 5. Example 1.3 of ATA, measures 1–9 (page 4, just first system)

(click to enlarge)

[9] Schachter’s sensitivity to key is apparent, also, in his comments about key implication. A key can be implied with varying degrees of strength and confidence, and our initial tonal interpretation of a chord may be revised in light of subsequent events. Schachter is keenly aware of these subtle issues, and makes a number of excellent observations about them; for example, in the Schubert Scherzo, he observes that our initial hearing of the ![]()

![]()

Example 6. Schenker’s analysis of Chopin’s “Revolutionary” Etude, from Five Graphic Analyses, shown in ATA on page 39

(click to enlarge)

[10] All this suggests that Schachter is trying to steer Schenkerian analysis toward a greater appreciation of key structure, and for this he should be commended. In other cases, though, even Schachter’s discussions fail to do justice to key structure. A case in point is his analysis of Chopin’s “Revolutionary” Etude, which is largely an exegesis of Schenker’s own analysis in Five Graphic Analyses (1969). Schenker’s view of the form of the piece is encapsulated by the third level of his analysis, labeled “2.Schicht” (Example 6). By this view, the piece consists of four linear descents from (grouped in twos by the interruption); the first three descents stop at , and the fourth one continues to . A virtue of this analysis, as Schachter observes, is that it recognizes the descending fourth in the bass, 1–![]()

![]()

[11] Schachter also acknowledges a more conventional view of the form of the piece, in which the second linear descent constitutes a “contrasting middle.” He goes on:

In that view, the piece is in three main parts—it’s a ternary form. We have a first section that is a kind of period, with antecedent and consequent phrases. Then we have a middle section that is, in a sense, developmental in character (though it doesn’t have the harmonic structure of the usual development section). Finally, we have a sort of recapitulation, starting with the introduction (measure 41), a return of the main theme, slightly varied but still with an antecedent (measures 50–58) and a consequent (measures 60–77). The consequent phrase is extended and leads to the final resolution, both melodic and harmonic, in measure 88, followed by the eight-measure coda. (34)

Example 7. Chopin, Etude Op. 10 No. 12, bast 63–71 (left-hand figuration is not shown)

(click to enlarge)

Schachter concedes that this ternary view of the form has “a certain validity” (43). But neither this conventional analysis nor Schenker’s analysis captures what is, for me, the most important aspect of the “contrasting middle,” namely, the sequence of keys that it takes us through: ![]()

[12] As I have described it here, the form of the piece consists of an initial establishment of C minor, a journey through several other keys and back to the tonic (and the opening theme), and then a briefer sojourn to more distantly related keys before the final tonic return. This is what gives the piece its satisfying dramatic shape. I do not see any acknowledgment of this in Schachter’s discussion—either in Schenker’s graph, or in the more conventional “ternary” analysis that Schachter offers as an alternative.

Example 8. A recomposition of part of the “Revolutionary” Etude

(click to enlarge)

[13] There is nothing very novel in my observations about key structure in the “Revolutionary” Etude. (Indeed, Schenker mentions and rejects exactly this sort of key-based analysis in a footnote to his analysis.) Perhaps some would consider them obvious. Obvious or not, they deserve to be included in anything that purports to be a “tonal analysis” of the piece. Possibly Schachter would acknowledge the reality of at least some of what I have said, just as I acknowledge (grudgingly) Schenker’s descending fourth progressions; so the issue is, perhaps, which is more important. Consider a thought experiment. We could recompose the Chopin so that the

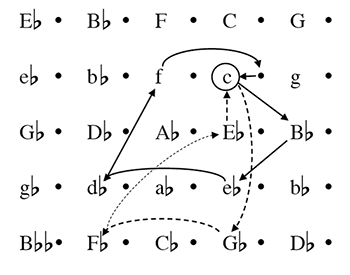

Figure 1. A key-space analysis of Chopin’s “Revolutionary” Etude

(click to enlarge)

[14] If we were to give greater attention to key structure in analysis, how would we do it? We could simply do it through informal description, as I have done here; key distances could similarly be described in informal terms, e.g. as “close” or “distant”. (To his credit, Schachter occasionally does describe key relations in this way—see 49 and 72, for example.) But what we really need is a more rigorous, systematic way of describing key structure—just as Schenkerian analysis provides a precise way of labeling linear progressions. Nothing of this kind is available, as far as I know; the whole topic of key remains woefully under-theorized. A useful starting point, though, is spatial representations of key. Figure 1 shows a diagram of the key structure of the Chopin Etude, using the two-dimensional key space first proposed by Gottfried Weber (1817–21; see also Schoenberg 1969; Krumhansl 1990; and Lerdahl 2001). The diagram shows the two journeys described earlier; the more dramatic nature of the second journey (shown with a dotted line) is apparent, both because it takes us further from the tonic, and because it involves larger moves between successive keys. This spatial representation is far from perfect. It has no way of conveying the duration of each key section (unlike Schenkerian analysis, which can represent duration using the horizontal axis), or the strength with which each key is established; also, each key is represented at multiple locations, requiring decisions (often arbitrary) about which representative to choose. But it is, as I said, a starting point; perhaps further theoretical work could improve on it. (I have added one theoretical innovation: a dot to the right of each key representing its dominant harmony, which I call the “five-dot.” This is useful for retransitional dominants, such as that in measures 41–48 of the Etude, where one feels that the key is tentatively implied but not yet fully established.)

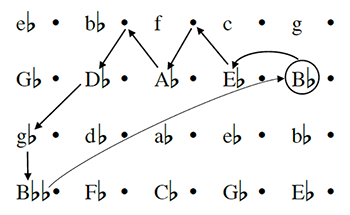

Figure 2. A key-space analysis of the Scherzo of Schubert’s Sonata in

(click to enlarge)

[15] Figure 2 shows a spatial analysis of another piece discussed by Schachter: the Scherzo of Schubert’s

* * *

[16] On practically every page of ATA, one is aware that one is reading a transcribed lecture rather than the usual scholarly prose. This is most evident in the book’s informal, conversational language. A great many paragraphs begin “Now let’s look at”, “Now I want to talk about”, “Let’s get back to”, or something of that nature. This is something we all do in lectures, but in in a conventional book we would probably strive to start paragraphs with more substantive “topic sentences.” The book is also more digressive than the typical music theory book, a bit less tightly organized and more “stream-of-consciousness”—again, as one might expect in a lecture. For me, these aspects of the book did not detract in the slightest from its clarity or impact, or from the pleasure of reading it. On the contrary, it is one of the most enjoyable music theory books I can remember reading (even when I strongly disagreed with it). It makes me think that music theorists should do this kind of thing more often—though I’m not sure that my own lectures would make such an entertaining read!

[17] The presentation and editing of the book is due to Joseph Straus, and is for the most part excellent. I found only a few typographical errors in the text and musical examples. No doubt it was not an easy task to take the original recordings of Schachter’s lectures and “smooth them out” (to use Straus’s words) in a way that preserved both their essential content and their informal character. There are just a few spots where I wonder if the transcription missed Schachter’s intended meaning. On page 68, Schachter notes that, in a major-key piece that moves to the subdominant, there is a danger that the tonic will sound like V of IV. We then read, “that wouldn’t be nearly as problematic in a minor key, because we usually don’t think of a minor chord (like IV

[18] Finally, let me return to an aspect of Schachter’s writing that I mentioned in the opening paragraphs: its enthusiasm. The book is peppered with superlatives, describing common-practice pieces and moments within them: “astonishing,” “amazing,” “wonderful,” “magnificent,” “fantastic.” This is a feature of Schachter’s other writings as well, and I have always appreciated it—perhaps because it is so unusual. (If we all did it, it might become rather tiresome!) Occasionally, he goes even further, as in these comments from the very end of the book (part of the “Q and A” session):

Why are there so few great composers and so few great pieces? Why is our core repertoire so small? And why has it remained so small even after the successes of the early music movement and even after 100 years of musical modernism? I think Schenker’s masterworks and his genius composers may have something to do with the nature of the musical language. Something very special happens in musical composition between around 1600 and 1920 for which there is no analog in the other arts. (280)

Some may find this view rather unfair to music outside the common-practice period (to say nothing of non-European music!). But I think even this should be forgiven. Surely it springs, simply, from Schachter’s deep affection for this body of music, the profound experiences it has given him, and his wish that others might also enjoy these experiences. I share these feelings, though I see this more as a matter of personal taste rather than anything absolute. In any case, the goal of bringing the pleasures of common-practice music to as many people as possible is surely a worthy one, and one to which Schachter’s work over the decades has made a huge contribution. For that, we should all salute him.

David Temperley

Eastman School of Music

26 Gibbs St.

Rochester, NY 14604

dtemperley@esm.rochester.edu

Works Cited

Gjerdingen, Robert. 2007. Music in the Galant Style. Oxford University Press.

Krumhansl, Carol. 1990. Cognitive Foundations of Musical Pitch. Oxford University Press.

Lerdahl, Fred. 2001. Tonal Pitch Space. Oxford University Press.

Schachter, Carl. 1990. “Either/Or.” In Schenker Studies, ed. Hedi Siegel, 165–80. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 1987. “Analysis by Key: Another Look at Modulation.” Music Analysis 6 (3): 289–318.

Schenker, Heinrich. 1969. Five Graphic Analyses. Dover.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1969 [1954]. Structural Functions of Harmony, ed. Leonard Stein. W.W. Norton.

Temperley, David. 2011. “Composition, Perception, and Schenkerian Theory.” Music Theory Spectrum 33 (2): 146–68.

—————. 2007. Music and Probability. MIT Press.

—————. 2006. “Key Structure in ‘Das alte Jahr vergangen ist.’” Journal of Music Theory 50 (1): 103–110.

Weber, Gottfried. 1817–21. Versuch einer geordneten Theorie der Tonsetzkunst. B. Schott.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2016 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

7793