The French Path: Early Major-Minor Theory from Jean Rousseau to Saint-Lambert*

Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers

KEYWORDS: Rousseau, Delair, Frère, Loulié, Masson, Nivers, Campion, Saint-Lambert, major-minor theory, church keys, key signatures, Méthode claire, France

ABSTRACT: This article examines the contributions of pre-Rameauvian French writers in theorizing the early major-minor system, starting with an important document of early major-minor theory: the Méthode claire, certaine et facile pour apprendre à chanter la musique (1683, 6/1707) by the singing master and viol player Jean Rousseau (1644–1699). Rousseau’s Méthode claire was the first continental treatise to entirely replace eight- and twelve-tonality systems with their major-minor successor. Not only do its pedagogical precepts for solmization open a fascinating window onto early major-minor theory, but the theoretical reorientation it proposes reverberated through subsequent French treatises: in the innovative ways in which French writers strove to theorize growing tonal resources, in their privileging of certain scale types, in the orderings they imposed on the major-minor tonalities, and in their attempts to systematize key signatures. The article thus illuminates the pioneering efforts of a generation of theorists that includes Denis Delair, François Campion, and Monsieur de Saint-Lambert to adapt received notions of tonal space to a new, major-minor context.

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1.1] The gradual crystallization of the major-minor system near the end of the seventeenth century is a topic that historians of music theory continually revisit in the conviction that this complex process is better grasped by deploying multiple, overlapping perspectives than by outlining a single, teleological narrative. This article highlights the innovations of a generation of French theorists who, for the first time in continental Europe, laid the groundwork for the theory of major-minor tonality. In the first part of this essay, I examine an important but little-known document of early major-minor theory: the Méthode claire, certaine et facile pour apprendre à chanter la musique (A Clear, Sure, and Easy Method For Learning to Sing, 1683, 6/1707) by the singing master and viol player Jean Rousseau (1644–1699).

[1.2] Solmization circa 1700 was a topic of great interest to teachers and theorists alike, one that both spurred and helped shape novel notions surrounding major-minor tonality. This was perhaps especially pronounced in France, where pedagogues developed and popularized a distinctive solmization approach, which they called “méthode du si,” and which they adapted to the changing tonal landscape of the time. As we will see, Rousseau’s Méthode claire is one of the earliest extant works to promote this approach; what is more, it was the first continental treatise to entirely replace eight- and twelve-tonality systems with a major-minor one.(1) Its pedagogical admonitions and precepts for solmization thus open a fascinating window onto early major-minor theory. In particular, Rousseau’s Méthode claire marks the point where the French tradition began to branch off from what Harold Powers (1998) has called “the route from psalmody to tonality”: namely, the treatise breaks off from a nexus of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century writings and compositions that emphasized a particular group of eight tonalities called “church keys” (not to be confused with the ecclesiastical modes, as will be discussed below), and which played a central role in the formation of major-minor tonality. As we will see, from the Méthode claire on, French writers increasingly cut their ties with church-key theory, ties that would remain securely fastened for several more decades elsewhere in Europe.

[1.3] The second part of the article outlines how Rousseau’s theoretical reorientation reverberated through a number of subsequent French treatises: in the ways French writers strove to theorize a growing wealth of tonal resources, in their privileging of certain scale types, in the orderings they imposed on major-minor tonalities, and in their attempts to systematize key signatures. And as writings by Denis Delair, Etienne Loulié, Alexandre Frère, Charles Masson, François Campion, and Monsieur de Saint-Lambert show, these efforts at classification and systematization distinguish French theorists from their Italian and German contemporaries. Rousseau’s Méthode claire was thus an inaugurating gesture: it heralded the pioneering efforts of a generation of theorists who—with characteristically French rigueur— adapted received notions of tonal space to a new, major-minor context.

Church Keys: A Brief Overview

[2.1] Late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century music theory was characterized by a bewildering plurality of approaches, including studies on acoustics, thorough-bass manuals, counterpoint treatises, plainchant tutors, lexicons, and singing and instrumental methods—disparate strands of musica theoria and musica pratica that would not be woven into a unified theory until Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Traité de l’harmonie of 1722.(2) Understandings of tonal organization were particularly fragmented. In France, traditional modal theory was in decline, progressively ousted by concepts related to the “church keys,” a set of eight tonalities distinct from the ecclesiastical modes. The church keys emerged in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as part of the liturgy of the Catholic Divine Office (or Liturgy of the Hours), the set of daily prayers prescribed by the Church for the canonical hours. This liturgy was grounded in the singing of psalms and antiphons. Whereas the latter were modal, the former were sung according to specific—and non-modal—melodic formulas called “psalm tones.” Psalm tones in turn gave rise to settings for the organ; these polyphonic elaborations featured soggetti and cadence points that were adapted to the psalm tones’ characteristic melodic structures rather than those of the corresponding modal antiphons. The resulting tonalities thus no longer depended on modal considerations such as ambitus and interval species. Adriano Banchieri first codified the church keys in his Cartella musicale of 1614.(3)

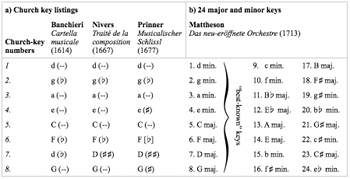

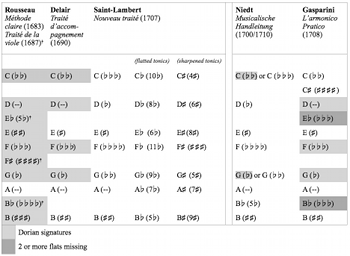

Table 1. 17th-century church-key listings and Mattheson’s 24 major/minor keys

(click to enlarge)

[2.2] In his foundational essay “From Psalmody to Tonality,” Harold Powers charted the cosmopolitan path that these church keys (which he called “psalm-tone tonalities”(4)) followed, from Banchieri onwards through seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century treatises and compositions from Italy, France, and Germany, up to their eventual absorption into the 24-key major and minor system (Powers 1998). Other scholars, including Joel Lester (1989), Gregory Barnett (1998, 2002), Michael Dodds (1999), and Robert Bates (1986), have investigated various stages along this route, and in so doing have shed new light on the theoretical and compositional significance of the church keys in the three main continental traditions. As Powers has shown, musicians often tabulated the finals, key signatures, and cadence points of these tuoni ecclesiastici, Kirchentöne, or Tons de l’Église, as they were variously called. Table 1a shows a selection of church-key listings from throughout the seventeenth century. The influence of the church keys also spread beyond sacred music. For example, as Barnett (1998) has argued, they permeated late seicento and early settecento sonata sets, both in matters of tonal ordering and internal organization. Their evolution culminated, in Powers’s account, in Johann Mattheson’s listing of the twenty-four major and minor keys in Das neu-eröffnete Orchestre (1713, 60–64), as shown in Table 1b. Mattheson’s listing begins with the eight church-key finals and expands outward to encompass the remaining keys. For Mattheson, the first eight keys are “easily the best known and most prominent [ones]”: their centrality in his map of major-minor tonality is unmistakable.

[2.3] To a point, the French tradition reflected these general developments: the Tons de l’Église served as an ordering scheme for the collections of such organ masters as Jean Titelouze, Nicolas Gigault, Nicolas Lebègue, Jacques Boyvin, André Raison, Louis-Nicolas Clérambault, and Guillaume Gabriel Nivers.(5) They also figured prominently in Nivers’s 1667 Traité de la composition de Musique, which prefaces its chapters on part-writing and fugue by noting that although “older theorists have prescribed twelve Modes to us, the most common division [now] is that of eight Modes or Church Tones.”(6) That this eminent organist, composer, and theorist regarded the church keys as the tonal framework most relevant for practical composition attests to their centrality in France in the years leading up to Rousseau’s Méthode claire. Their quasi-total exclusion from the latter, as we are about to see, is therefore all the more conspicuous.

Rousseau’s Méthode claire: a solmization tutor in its tonal context

[3.1] Since none of Rousseau’s music survives, posterity remembers him mainly as a theorist and pedagogue.(7) His Méthode claire is a practical singing manual devoted to teaching fundamentals (note names, sight-singing, the basics of meter and rhythm, and various vocal ornaments) with a particular emphasis—half its length—on solmization. Though it is now almost forgotten, the volume unquestionably garnered some international repute in its day: Mattheson praised it in Der vollkommene Capellmeister and Johann Gottfried Walther considered it worth mentioning in his seminal Musicalisches Lexicon (Mattheson 1739, 173–74; Walther 1732, 535). It also enjoyed respectable commercial success, with possibly as many as seven editions published by 1707, though some are doubtful or lost. As Robert A. Green has shown, the Méthode claire has a complex and somewhat obscure publication history (Green 1979, 22–34). Its first extant edition dates from 1683; a 1678 edition, which François-Joseph Fétis mentions in his Biographie universelle des musiciens, may have been lost, though Green believes that Fétis could simply have been mistaken (Fétis 1867, 7:333). An enlarged “fourth edition,” the second earliest extant, appeared in Paris in 1691. The book was also reedited a number of times in the Netherlands. The modern Minkoff reprint of the Méthode claire, for example, is based on a 1707 Amsterdam edition by Mortier; however, Green notes that this was a pirated version that contains a number of mistakes. Unless specified otherwise, I will refer to the expanded 1691 Paris edition, the most complete and authentic of the extant editions.

[3.2] The full, delightfully verbose title of the 1691 Paris edition reads A Clear, Sure, and Easy Method For Learning to Sing: in all the Natural and Transposed Tones; in all Kinds of Meters; with Rules for Portamento and Cadence, even when they are not indicated. And a Clarification of many Problems which must be understood for Perfection in the Art.(8) The title makes it clear that Rousseau’s treatise belongs to the practical vein of music theory that began, in the later seventeenth century, to eclipse more speculative approaches. This paradigm shift also saw major-minor theory edge out modality in mainstream theoretical discourse.(9) The Méthode claire, Rousseau’s first work (a Traité de la viole would follow in 1687), epitomizes this transition: its teachings unfold in a tonal space entirely organized into major and minor keys, a state of affairs that quickly became the norm in French writings. Rousseau made no claim to originality vis-à-vis the major-minor framework he adopted; for him, it was a fait accompli that required neither explanation nor justification. That the French were at the forefront of major-minor thinking even before Rousseau is clear from Antonio Bertali’s remarks in his Instructio musicali Domini Antonii Berthali (1676): “In the end I share the French opinion with many other virtuosi that there are no more than two keys [Toni], one with B moll, and the other with quadro. For example in D minor or in D major, in G minor or in G major, and I show the proof of this in that I can deduce from these two keys each of the twelve that I have established.”(10) Such early and seemingly uncontroversial adoption of a major-minor framework was by no means evident outside of France. German theorists, for instance, were reticent about jettisoning modal theory; as late as Johann Philipp Kirnberger, they continued to stress its importance for composition and performance.(11)

[3.3] Rousseau’s nonchalant adoption of major and minor keys in his Méthode claire went hand in hand with an equally nonchalant overlook of church keys. The 1683 edition of the treatise makes no mention whatsoever of them; rather, Rousseau refers exclusively to major and minor keys. The church keys do make a cameo appearance in the Eclaircissement sur plusieurs difficultez (Clarification of Several Difficulties) that Rousseau appended to the 1691 edition. Barnett (2002, 434) has underscored the historical importance of the Eclaircissement’s “Thirteenth Question,” where Rousseau literally folds the church keys into the major-minor system:

Thirteenth Question

How can one tell that a piece of music is in the first [church] tone, second tone, etc., up to the eight?

To satisfy in some way this question but not to expand further than I should in this work, I will say only that if a piece of music is in D la re minor, it is in the first tone; in G re sol minor, it is in the second; in A mi la minor, it is in the third, in E si mi minor, it is in the fourth tone.(12)

And so forth, up to the eighth church key (paired with G ré sol major). Here, as Barnett points out—and seemingly for the first time in history—the entire set of psalm-tone tonalities is recast in the major-minor vocabulary that would subsequently dominate French tonal discourse. Rousseau refrains, however, from elaborating further, since the church keys “concern composition more than singing” and therefore “fall outside the scope of this work.”(13) Thus, while he acknowledges their saliency in the tonal landscape of his day, Rousseau does not regard them as an appropriate tonal framework for marshalling his pupils over the hurdles of modern solmization. Insofar as the Méthode claire embodies a moment in which traditional tonal perspectives yield to forward-looking ones, it provides the first intimation of the church keys’ waning influence in French theoretical and pedagogical texts. This is not to say, of course, that Méthode claire’s melting of church keys into major-minor tonalities points to a simple process by which the latter straightforwardly displaced or succeeded to the former. Church keys—as well as modes—remained well alive far into the eighteenth century, as several church musicians continued to sing, play the organ, teach, compose, or conduct choirs while maintaining these older traditions. French writers, however, embraced the new major-minor tonal worldview with remarkable and unequalled zeal and consistency. As we shall see, Rousseau’s resolute grounding of various concepts and approaches previously linked to the church keys, and even to modality, in major-minor tonality constitutes perhaps the most intriguing aspect of his treatise.

The French path branches off: “Natural/transposed” keys

and the “méthode du si” in the Méthode claire

[4.1] The eventual integration of the eight church keys into the twenty-four major/minor keys, as Powers and Barnett have elegantly demonstrated, had to do with the various additional tonalities yielded through transposition. In Italian and German writings in particular, the church keys often constituted a basic core to which other tonalities were then related transpositionally. For instance, in his 1687 set of Versetti per tutti li tuoni for organ, Giovanni Battista Degli Antonii proposes two levels of transposition for each church key, a tone or a semitone above and below, resulting in eight “natural” (naturali) and sixteen “transposed” (trasportati) tonalities. Georg Falck’s 1688 Idea boni cantoris provides another example: Falck begins by listing the church-key finals, which he calls the “regular” tones or modes, and then adds eight other “ficta or transposed modes or tones” for which he specifies the major or minor quality of the third (e.g., “A dur. ob tertiam Maj.” Lester 1989, 83–84; Dodds 1999, 187–90). Note that in both Degli Antonii and Falck, a

[4.2] Of course, French church musicians, too, had obtained “transposed” tonalities from the eight Tons de l’Église: Nivers’s Livre d’Orgue Contenant Cent Pieces de tous les Tons de l’Eglise, for instance, opens with a chart entitled “Tables des 8 Tons de l’Eglise, au naturel et transposez” that presented the church keys at four levels of transposition to accommodate different choirs of high and low voices (Nivers 1665). Nonetheless, French theorists soon began to systematize tonal resources in their own distinctive way. In so doing, they did not discard the concept of natural and transposed tonalities—pace Dahlhaus’s claims that “in the case of major-minor tonality, the distinction between ‘transposed’ and ‘untransposed’ scales misses the mark,” and that “as a relative distinction it is meaningless; as an absolute distinction it fails entirely” (Dahlhaus 1990, 154–55). In fact, as an absolute distinction, the natural/transposed dichotomy played a significant role in fledgling major-minor theory, where it served to classify and conceptualize a rapidly growing number of keys. Practical manuals often dealt with the challenge of transposing at sight to a variety of tonalities featuring disconcerting multi-accidental signatures, and Rousseau and others proposed that a group of natural, simple keys serve as models for the less familiar transposed ones. “Naturalizing” transposed keys (réduire au naturel) thus became a widespread preoccupation for French writers.(14) But while Rousseau preserved the existing natural/transposed dichotomy (which persisted into the eighteenth-century), from the Méthode claire onwards that division was decoupled from the church keys’ influence. Moreover, although seventeenth-century handbooks throughout Europe addressed the issue of multi-accidental signatures and taught performers to read unfamiliar or crowded signatures by mentally substituting simpler ones, French musicians also developed a particular solmization method of their own—a pedagogical idiosyncrasy that, in Rousseau’s hands, dovetailed with the emergence of certain basic tenets of early major-minor theory. As we will see, Rousseau tailored this existing solmization approach to suit a new tonal context and at the same time implanted the natural/transposed dichotomy into major-minor tonality. The Méthode claire is thus the ideal place to detect the first signs of the French theoretical egression from the road between psalmody and tonality.

Figure 1. Rousseau, “De la nomination des Notes” (Méthode claire, 3); Nivers, “7 voix”(Méthode facile, 6)

(click to enlarge)

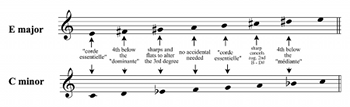

Figure 2. Rousseau’s “Two ways” (Méthode claire, 5; cf. Nivers, Méthode facile, 18)

(click to enlarge)

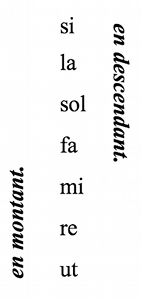

[4.3] The “clear, sure, and easy” approach to solmization of which the Méthode claire boasts is the méthode du si, a technique that replaced hexachords and mutations by a seven-syllable scale, the gamme du si, superimposed over the traditional durus and mollis (or b quarre and b mol in Rousseau’s words) background scales ( Floirat et. al. 1999; Anderson 1979). Seven-syllable solmization in itself was not a French innovation; several theorists, including Ramos de Pareja, Anselm of Flanders, Hubert Waelrant, Johannes Lippius, and Marin Mersenne, had already proposed hepta- and octosyllabic systems, these last sometimes with alternate syllables for B and

[4.4] So far Rousseau had not strayed from the principles expounded by the Maistre celebre de Paris, but he was about to extend their reach considerably. A primary difference between the treatises is the tonal context to which the theorists anchor their doctrines. Although not a plainchant tutor per se, the older Méthode begins by linking solmization (intonation) to ecclesiastical practice:

The principles of music are based on the diversity of notes and the variety of their shapes. These are its two parts: the diversity of notes concerns solmization, and the variety of shapes concerns rhythm and meter.

Regarding the first part, music is in no respect different from plainchant, because the manner of solmizing is the same. . . . In a word, plainchant is the first part of music, and someone who has learned [only] this first part, only understands plainchant.(19)

In his 1699 Méthode certaine pour apprendre le plainchant de l’Église, which Cohen believes is an extended edition of the anonymous treatise of 1666, Nivers once more employs the méthode du si to teach students to sing antiphons and responses. Rousseau, on the other hand, makes no mention whatsoever of plainchant; rather, each of the thirteen tonalities outlined in the various exercises of his Méthode claire is explicitly major or minor in mode.

[4.5] A second important difference between the respective Méthodes is the topic of transposed keys, which the older author omits entirely. Rousseau, in contrast, invokes the méthode du si and the gamme double precisely to address the “difficulties that were introduced into music some time ago, such as different transpositions which

It must first be stated as a principle that there are b-mol natural keys [Tons naturels par b mol] as well as♮ -quarre natural keys [Tons naturels par♮ quarre]. . . . The b-mol natural keys are those where a flat is written after the clef, where the note would be called si if it were natural, but where it is called fa because of the flat. The♮ -quarre natural keys are those where no flats or sharps are written after the clef. Therefore, all other keys that have more than one flat near the clef . . . are b-mol transposed, and those who have one or many sharps near the clef are♮ -quarre transposed.(21)

Table 2. Rousseau’s Méthode claire: 13 major and minor keys

(click to enlarge)

When read with the Méthode claire’s thirteen keys in mind, the “Tenth Question” makes clear—its circumlocutions notwithstanding—that Rousseau privileged a set of core keys distinct in both number and scale types from those featured in the other treatises I have surveyed. Since Rousseau’s natural keys have either one flat or none (and no sharps), five tonalities in the Méthode claire correspond to this definition: D minor (--), A minor (--), C major (--), G minor (

[4.6] Rousseau’s conception of the Tons transposez also marked a departure from the traditional practices regulating transpositional relationships between church keys. As Barnett has stressed, transposing a church key often yielded a new key with a different signature type and scale structure. For example, in his abovementioned 1687 Versetti, Degli Antonii proposed church key 3, a (--), as the equivalent una voce più alta to the naturale church key g (

In order to sing the transposed keys of C sol ut with a minor third and B fa si with a major third [i.e., B-flat major] as though they were natural, ut must be said on the degree where si in the b quarre column would be said. From there one can proceed to the other notes without worrying about the other flats at the clef. In F ut fa minor third, sol should be said on this same degree of si. In the b-quarre transposed keys, si should be said on the degree of fa in G re sol with a major third.

And so on for the remaining transposed keys. Ever the meticulous pedagogue, he also offers an alternate set of instructions:

To make this easier: in the case of b-mol transposed keys where the flat applies to two different scale degrees, ut must be said on the degree where si would be said in the b quarre column. . . .

When a sharp applies to one scale degree in b-quarre transposed keys, si must be said on the same degree as that of fa.(24)

In other words, Rousseau provides the appropriate solmization syllable for

[4.7] With characteristic thoroughness, Rousseau recognized that the success of his alternate set of instructions (i.e., “to make this easier,” etc.) depended on whether the signature of a transposed piece presents what he considered to be a correct signature. (For example, in an excerpt in E-flat major signed incorrectly with two flats rather than three, a vocalist following his guidelines would pair ut with

It is true that one often encounters pieces of music where the flats and sharps are not marked properly after the clef in the transposed keys; this often causes difficulty for students, and it makes it impossible for them to use the rules that we have given to naturalize transposed keys.(25)

Rousseau then goes on to recapitulate the signatures of his thirteen keys, and he adds that in pieces having deficient signatures, the missing flats or sharps will be noted as accidentals throughout and can thus be assumed at the clef. With this last loophole closed, the Méthode claire has achieved its primary goal: to allow one to sing “the different transpositions . . . without confusion and in a very natural way.”(26)

[4.8] By privileging a natural/transposed categorization whose implications of primacy and derivation differed in important respects from those accruing to the church keys, Rousseau’s treatise constitutes a pivotal juncture leading off Powers’s route from psalmody to tonality. Beginning with the Méthode claire, the church keys no longer served as strongly as a point of tonal reference or a source for transposed tonalities in French treatises. And while Rousseau’s reasons for privileging his set of natural keys over the “majorized/minorized” church keys of his “Thirteenth Question” were eminently tied to solmization, other French authors would soon discard church keys in other contexts as well. In his Nouveau traité des règles de la composition (1699), Charles Masson explained:

Older writers employed the term “Mode,” but most modern writers use “Ton” instead of “Mode,” because the different ways to sing chants de l’Église are called “Tons.” But in order to be able to come more quickly to composition, I will present only two modes, the major mode and the minor mode.(27)

Rousseau’s Méthode claire thus offers a revealing lens through which to examine early major-minor thought. Its author strikes a sensitive balance between pedagogical dictates—mostly in the body of the Méthode—and more generalized theoretical statements—especially in the Éclaircissement. The work deftly fuses tradition and innovation by drawing on an existing solmization approach but extending that approach’s principles to address tonalities reaching further into transpositional territory than those for which it was initially conceived. Here tonality inheres in a network of dichotomies that Rousseau intertwines with keen practical flair: the novel distinction between major and minor, the Guidonian one between hard (par b quarre) and soft (par b mol), and the hierarchical one between transposed and natural. These dichotomies would have half-lives of varying lengths, but even the relatively short-lived par b quarre/b mol and natural/transposed distinctions remained in use for some decades more. For indeed, as we will see below, the Méthode claire laid a firm foundation on which its successors erected a major–minor theory evincing distinctive national traits. The question of proper signatures that Rousseau broached in the “Tenth Question” would soon emerge as a major concern among French theorists, even outside the context of solmisation. Likewise, Rousseau’s hierarchical organization of the major and minor keys would resonate in subsequent writers’ theorizing of signatures and in their reconfigurations of his concepts of naturalness and transposition. Later theorists continued to flesh out Rousseau’s map of major-minor tonality and to explore how the keys involved could be categorized and understood to relate to one another.

“The road to the asylum”: key signatures after Rousseau

[5.1] The three scale types (one major and two minor) that Rousseau’s keys all evince quickly became the standard for subsequent theorists. Indeed, a characteristic feature of French treatises at the turn of the eighteenth century is the uniformity of their key-signature schemes. If we survey the tonal resources laid out in contemporaneous German and Italian sources, we often find discrepancies in key-signature notation between treatises, as well as a blending of complete and so-called incomplete key signatures within single treatises. In contrast, rationalizing key signatures was a matter of great interest (and sometimes, it appears, of real anxiety!) for French theorists, who endeavored to fix the proper number of sharps or flats for each key and to compile various tables and listings for performers to memorize.

[5.2] Accordingly, French writers austerely chastised unruly composers—especially Italians—who neglected to write proper signatures. In his 1690 Traité d’acompagnement pour le théorbe, et le clavessin, Denis Delair noted disapprovingly that “one frequently finds [Italian pieces] . . . in which the flats or sharps natural to the mode of the piece are not marked,” and in 1716 François Campion reprimanded, “all those Italians do not agree on how to notate signatures. Some write more or fewer sharps and flats than the others. . . . I do not approve of that.” Alexandre Frère likewise berated reprobate composers in his Transpositions de musique réduites au naturel, insisting that “all the necessary flats and sharps for each key should be placed beside the clef in their proper number . . . but the way in which composers write sometimes creates difficulties for us.”(29)

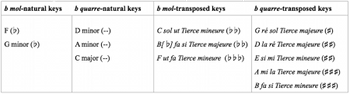

Table 3. Major-key signatures

(click to enlarge)

Table 4. Minor-key signatures

(click to enlarge)

[5.3] Modern writers have long interpreted these inconsistent signatures, so pervasive in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, as remnants of modal practice. More recently, Barnett has sensitively suggested that signatures with missing or supernumerary accidentals should be understood as an outgrowth of the church keys and their transpositions—an argument that is, of course, unobjectionable with respect to the German and Italian traditions (Barnett 2002, 429). But since French writers after Rousseau employed other keys than the Tons de l’Église as models for transposition, it is perhaps unsurprising that the evolution in their signature types followed a distinctive path. Table 3 shows a sample of key signatures for major keys from a variety of treatises circa 1700. In the French treatises, all keys appear with complete signatures as early as Rousseau’s Méthode claire. Major-mode signatures outside France, on the other hand, as often as not reflected their roots in church keys or were simply less homogeneous. For instance, in Daniel Speer’s Grund-richtiger Unterricht (1697), three out of seven major keys feature “incomplete” signatures. In Francesco Gasparini’s L’armonico pratico al cimbalo (1708), this number rises to seven out of ten major keys.(30)

[5.4] It would take minor key signatures some decades to arrive at the uniformity that the major ones enjoyed from the start, although there were still fewer discrepancies in French treatises than non-French ones. Table 4 shows that the former feature a mix of “complete” and “incomplete” (or Dorian) signatures, in accordance with the two types of minor scales that Rousseau advocated. Outside France, the discrepancies grew with the complexity of the signatures: witness Gasparini’s “enharmonic and chromatic” keys, which lack up to three flats. In contrast, each signature in Monsieur de Saint-Lambert’s Nouveau traité de l’accompagnement du clavecin, de l’orgue et des autres instruments (published a year before Gasparini’s) bears every last flat or sharp, even in such outlandish signatures as F-flat major and B-sharp minor. Campion warned in colorful language against those who might attempt to compose in such extravagant keys. Deriding the unnamed author of a piece in D-flat minor, he quips: “if he modulates to the minor sixth of this octave, which is B double-flat, and if he continues in this fashion from modulation to modulation, he could pave the road to the asylum [Petites Maisons] with flats.”(31)

[5.5] Seventeenth-century French theorists, of course, saw nothing incomplete (or insane) about Dorian signatures, since they reckoned “mode” primarily from a key’s mediant degree. Indeed, “major” and “minor” were, at least at first, simply abbreviations for “major third” and “minor third.” As Rousseau put it, “C sol ut minor and C sol ut minor third are the same thing.”(32) This definition remained unchallenged until the end of the century, with Masson echoing it all but exactly in his Nouveau traité.(33) Both “complete” and Dorian signatures thus provided the necessary mode-defining information: in all flat Dorian signatures, the last accidental is precisely the one that inflects the mediant. Whether to add the “missing flat” or to remove the “extra sharp” affecting the submediant in Dorian signatures was a subject of debate. Frère, for one, insisted on Dorian signatures for all minor tonalities; Campion, on the other hand, omitted the “extra sharp” in minor signatures (e.g.

Remarks on the sixth note of a minor key, in descending motion.

The sixth note of a minor key, in descending motion, is the flat. . . . That is undoubtedly why many Italians write a flat at the key signature in the D octave, which does not seem right to me, because from the dominant, or the fifth note of a key, we ascend by whole tone when approaching the sharpened leading-tone, and we descend [to the fifth] by semitone through the flatted note found on the sixth note of the key . . . ; in consequence, the flat must not be written near the clef since it is accidental. . . . In the A octave, the F is sharp when ascending, and natural when descending, thus acting as a flatted note.(34)

Thus, Campion regarded the accidental pertaining to the sixth degree as a fluctuating one, and as such, held that it was not mode-defining and did not belong in the signature. With this principle, he provided a rationale for eliminating, in most treatises, the “extra sharp” of sharp Dorian signatures a few decades before the “missing flat” in flat Dorian ones appeared consistently. In a later Addition to his treatise, Campion devised a taxonomy for these two types of minor scales, calling those modeled on D la ré minor the réyennes scales and those modeled on the scale of A mi la minor the layennes. Insisting on just one type of octave species for the minor mode, he resolutely decreed, was nothing less than “vicious” (Campion 1730, 46–49).

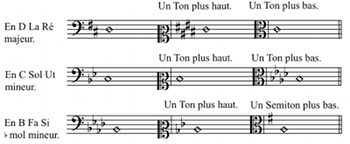

Figure 3. Delair’s “principles of the flats or sharps that are put at the beginning of the clefs”

(click to enlarge)

[5.6] Though Campion’s layenne/réyenne distinction did not enter mainstream use, his comments testify to ongoing efforts to systematize signatures, tighten their relationship to scale structure, and flesh out the concept of mode beyond that articulated by Rousseau. In this last respect, Denis Delair’s discussion of signatures proved a harbinger of change: Delair began to detach signatures from the process of transposition and to link them to scale degrees instead. Thus he provides a detailed explanation of why various keys required particular sharps or flats, and of how to determine these. He does so by appealing to the cordes essentielles, or “essential notes” of a key, i.e. the finale, médiante, and dominante.(35) Delair posits three principles or fondements for arriving at proper signatures, or the “principles of the flats or sharps that are put at the beginning of the clefs,” which Figure 3 summarizes (Delair 1690, 53–54; trans. Mattax 1991, 131). The first principle, which Delair calls “the sharps and flats written by the clef, to change the nature of the thirds,” ensures that the inflection of the mediant appears in the key signature. Second, signatures must establish a perfect fourth below each corde essentielle to allow for cadential motion to it.(36) Finally, additional sharps or flats should correct any augmented seconds that might crop up in the scale. Delair’s principles are not quite watertight; he still had to resort to ad hoc explanations for two of his signatures: the key of F major, he says, demands one flat to cancel the tritone between F and B, while B-flat major needs an

[5.7] In his Nouveau traité, Saint-Lambert finally achieved a definition of mode that is entirely scale-degree based and reflected in all signatures. He posits no less than forty-two (!) major and minor keys, one for each of the seven litterae and for their seven sharpened and seven flatted versions, in both major and minor: i.e., C major, C minor; C-sharp major, C-sharp minor; C-flat major, C-flat minor; and so on. Further, he discards Dorian signatures altogether and instead selects the natural minor as his model:

The Mode of an Air is major when the Third, Sixth, & Seventh from the final or tonic note are major.

The Mode is minor when the Third, Sixth, & Seventh from the final are minor.

The Second, Fourth, Fifth, & Octave are of the same species in the major Mode as in the minor [Mode].(38)

[5.8] Saint-Lambert thus ensured complete signatures in all keys. (Only the Czech theorist Thomas Balthasar Janowka preceded him in this respect, in his 1701 Clavis ad thesaurum magnae artis musicae. Jean-Pierre Freillon-Poncein had also already listed forty-two major and minor keys in his La veritable manière d’apprendre à jouer en perfection du haut-bois, de la flûte et du flageolet; however, his minor keys all bore Dorian signatures (1700, 51–53). Not all subsequent writers would agree; as we have seen, Campion still insisted, nine years later, that a flatted sixth degree need not figure in the signature. But it was Saint-Lambert’s model that Rameau adopted in the Supplément to his Traité de l’harmonie. While he applauded Frère for fostering consistency in signatures by reducing all minor keys to a ré octave, Rameau himself settled on the la octave (1722, 11 in the Supplément).(39) The uniform signatures that Saint-Lambert advocated also reflect different kinds of relationships between keys than those found in his predecessors’ treatises. In Rousseau and others, for example, E minor

Natural keys and ordered key schemes after Rousseau

[6.1] Rousseau’s natural/transposed dichotomy proved prophetic: his successors continued to speak of “natural” major and minor keys even when they expanded or modified that concept. Frère and Étienne Loulié, for instance, both restrict the Tons naturels to the unsigned major and minor scales. In his Éléments ou principes de musique (1696), Loulié stipulates that “Transposed Music is that which has one or more sharps or flats immediately following the clef. Natural Music is that which has neither sharps nor flats immediately after the clef” (Loulié 1696, 26; trans. Cohen 1965, 22). Similarly, Frère called the keys of C major

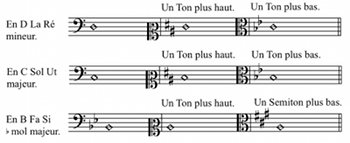

Figure 4a. Rousseau’s first series (Traité de la viole, 1687)

(click to enlarge)

Figure 4b. Rousseau’s second series (Traité de la viole, 1687)

(click to enlarge)

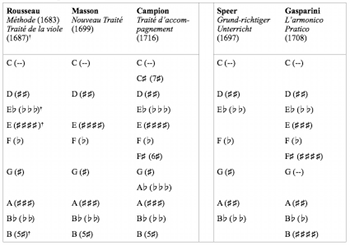

Table 5. French orderings of tonalities

(click to enlarge)

[6.2] Ultimately, a somewhat different series of keys replaced the church-key derived sets prevalent in Italian and German treatises in French writings. This set first appears in another work by Rousseau, the Traité de la viole of 1687, in a section devoted to sight transposition. As Figure 4 shows, Rousseau posits two series of seven (Fig. 4a) and eleven (Fig. 4b) keys respectively; he then transposes each series by ascending and descending seconds, thirds, and fourths.(40) The church keys serve even less here as a referential set than in the Méthode claire. The keys in the first series take as their tonics the notes of a D-minor scale (D, C,

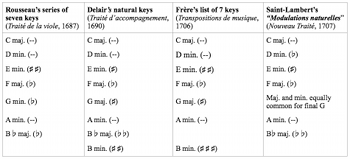

[6.3] What is remarkable is that this seven-key series shows up in near-exact form in a number of subsequent French treatises (Table 5). To begin with, Delair’s natural keys correspond to Rousseau’s first series, with the addition of B minor; as a result, Delair has tonics on all the litterae of the gamme double. Only the mode for the G final differs, having one sharp instead of one flat. Delair, too, orders his keys in scalar fashion, but ascending from C. A similar seven-key series also appears in Frère’s Transpositions de musique. There, Frère twice lists a set of finals spelling out a C-major scale (thus including the final B but not

[6.4] Finally, in his Nouveau traité, Saint-Lambert specifically singles out Rousseau’s first series. His forty-two keys are arranged in six ascending series of seven keys (major and minor keys with unaltered tonics, major and minor keys with sharpened tonics, and major and minor keys with flatted tonics; see his configuration for minor keys in Table 4 above). Privileging abstract systematization over concrete usage, Saint-Lambert specifies that “among these tonalities there are some . . . that perhaps have never been pressed into service; but I wished to omit none from the Demonstration—because the majority of our Composers, by now employing many [tonalities] not previously in use, may finally render them all equally commonplace.”(42) But there are also seven tonalities that, Saint-Lambert points out, are so familiar to musicians that it is not even necessary to state their mode since it is “understood” and “natural”:

There are, nevertheless, some modulations that are tacitly understood because they are considered to be natural to particular tonalities.

When one says that an Air is in C Sol Ut without mentioning its modulation, one implies that it is in major.

When one says that [an Air] is in D La Re, one implies that its mode is minor.(43)

E minor, F major and A minor are the other keys of such “common use” (usage commun) that their mode is automatically known. The tonic G does not imply one mode more than the other, but Saint-Lambert gives B-flat major as another conventional “modulation,” adding that the somewhat less usual

[6.5] The captivating mixture of traditional and forward-looking perspectives in Saint-Lambert’s Nouveau traité is an appropriate point to conclude this account of French theory’s idiosyncratic path from psalmody to tonality. Written some thirty years after Rousseau’s singing tutor, Saint-Lambert’s text allows us to witness the adoption, development, and obsolescence of the main tenets advanced in the Méthode claire, and to observe the impulse towards systematization that marked French theory between Rousseau and Rameau. The distinction between naturel and transposez, with its “par b mol/par b quarre” acolytes, is a case in point. While it evolved over time, for some thirty years it remained an inescapable distinction both for teaching solmization and for conceptually mapping an expanding tonal territory. That Saint-Lambert orders his tonalities by whether their tonics are natural, flat, or sharp shows that the categories “par b mol” and “par b quarre” still retained some salience in the early eighteenth century. The epithet “transposed” that used to precede these locutions, however, vanished entirely. While Saint-Lambert does emphasize a group of keys “in common use” that harks back to Rousseau’s first series in the Traité de la viole, nowhere in the Nouveau traité do these or other tonalities serve as a reference for transposition. For Saint-Lambert, the concept of “transposition” no longer names a category of keys, identifiable by such external characteristics as the contents of their signatures (as in Rousseau) or the inflection of their mediants (as in Delair); instead, it refers exclusively to the operation that maps one scale onto another. This is not to say that all keys are now equal: vestiges of older hierarchical relationships remain in Saint-Lambert’s designation of seven of his keys as “common” and twenty-seven others as “rare.” But in the end, the visual impression left by his strict ascending schemes downplays any perception of transpositional relationships between the “common” keys and the remaining thirty-five—as well as bespeaking a pronounced esprit de système. The once cardinal natural/transposed distinction has all but disappeared, and we have now reached the point where, in Dahlhaus’s phrase, an absolute demarcation between untransposed and transposed keys has become untenable. Not coincidentally, the tool that Rousseau used to deal with transposed keys—the méthode du si with its concomitant gamme double—also became obsolete at precisely this time. Loulié tolled its death knell in the Elements, arguing that it was time to “abandon the resources and the tones of the b mol column” (rompre ainsi les chemins & les voix de Bemol) in favor of a simple scale (gamme simple; Loulié 1696, 48). By the time Jean-Jacques Rousseau mentioned the gamme françoise in his Dictionnaire, it had already become an archaism.

[6.6] From the moment Rousseau limited the number of scale types to three in the Méthode claire, the mounting concern of French theorists for an internally coherent major-minor system became evident. It shines through their efforts to elaborate the notions of major and minor, such that these modes came to explicitly determine every scale degree of a key rather than just its mediant. Theorists also sought to tighten the link between key identity and key signature: that the latter may be key-defining was still a novel idea at the time, and also a very French one. Rather than mixing and matching tonics and variable signatures, French writers offered rationales for flats and sharps “immediatement après la Clef” and ironed out inconsistencies therein, even bringing this exactness to bear even on purely imagined tonalities. Saint-Lambert’s complete signatures for his twenty-three pairs of major and minor parallel keys in ascending order are an eloquent manifestation of the French inclination to prioritize systematization over tradition.

[6.7] Finally, comparing the key schemes that Saint-Lambert and Mattheson compiled within five years of one another speaks to the marginalization of the church keys in French major-minor theory and to the distinct path—among the many that crisscrossed the European theoretical landscape—that French theorists forged towards the modern twenty-four key system. The keys that Saint-Lambert thought most familiar in 1707, his tons communs for the seven litterae, do not coincide with Mattheson’s eight “best known” keys of 1713, the major/minor versions of the church keys. And Saint-Lambert’s strict ascending scheme, in stark contrast to Mattheson’s church-key-derived set, exemplifies the scalar ordering that several French writers had come to adopt, both in vocal and in instrumental tutors. French treatises at the end of the Grand Siècle exhibit an ever-growing body of keys that, rather than proliferating from a crux of eight church keys, expand out of a smaller group of tonalities of more consistent scale-types. French theorists organized these expanding tonal resources by systematically building keys on scale degrees, while ensuring that each key had its parallel major or minor or its chromatically inflected counterpart. Thanks to the sensitivity with which Rousseau and his successors adapted their terminology and pedagogical methods to the major-minor system, the path they cleared on the way to twenty-four major-minor keys is striking in its logic, cogency, and originality.

Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers

University of Ottawa

School of Music

50, University

Ottawa, ON (Canada) K1N 6N5

jpedneau@uottawa.ca

Works Cited

Anderson, Gene. 1979. “La gamme du si: A Chapter in the History of Solmization.” Indiana Theory Review 3 (1): 40–47.

Atcherson, Walter T. 1973. “Key and Mode in Seventeenth-Century Music Theory Books.” Journal of Music Theory 17 (2): 204–32.

Barnett, Gregory. 1998. “Modal Theory, Church Keys, and the Sonata at the End of the Seventeenth Century.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 51 (2): 245–81.

—————. 2002. “Tonal Organization in Seventeenth-Century Music Theory.” In The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, ed. Thomas Christensen, 407–55. Cambridge University Press.

Bates, Robert Frederick. 1986. “From Mode to Key: A Study of Seventeenth-Century French Liturgical Organ Music and Music Theory.” PhD diss., Stanford University.

Brossard, Sébastien de. 1705. “MODO.” In Dictionaire de Musique, contenant une Explication des Termes Grecs, Latins, Italiens & François les plus usitez dans la Musique. 2nd ed. Ballard. Facsimile: F. Knuf, 1965.

Campion, François. 1716. Traité d’accompagnement et de composition selon la règle des octaves de musique. Veuve G. Adam and the author. Facsimile: Minkoff, 1976.

—————. 1730. Addition au Traité d’accompagnement et de composition par la régle de l’octave. Veuve Ribou, Boivin, Le Clerc, and the author. Facsimile: Minkoff, 1976

Cohen, Albert, trans. 1961. Treatise on the Composition of Music. Institute of Mediaeval Music.

—————. 1965. Elements or Principles of Music. Institute of Mediaeval Music.

Cohen, Albert. 1966. “Survivals of Renaissance Thought in French Theory 1610–1670: A Bibliographical Study.” In Aspects of Medieval and Renaissance Music: A Birthday Offering to Gustave Reese, ed. Jan LaRue, Martin Bernstein, Hans Lenneberg, and Victor Fell Yellin, 82–95. Norton.

—————. 1972. “Symposium on Seventeenth-Century Music Theory: France.” Journal of Music Theory 16 (1–2): 16–35.

Dalhaus, Carl. 1990. Studies on the Origin of Harmonic Tonality. Trans. Robert O. Gjerdingen. Princeton University Press.

Degli Antonii, Giovanni Battista. 1687. Versetti per tutti li tuoni naturali, come trasportati per l’organo, Op. 2. Monti.

Delair, Denis. 1690. Traité d’acompagnement pour le théorbe, et le clavessin. Paris. Facsimile: Minkoff, 1972. Trans. with commentary by Charlotte Mattax as Accompaniment on Theorbo and Harpsichord: Denis Delair’s Treatise of 1690. Indiana University Press, 1991.

Dodds, Michael R. 1999. “The Baroque Church Tones in Theory and Practice.” PhD diss., University of Rochester.

Falck, Georg. 1688. Idea boni cantoris. W. M. Endter.

Federhofer, Hellmut. 1958. “Zur handschriftlichen Überlieferung der Musiktheorie in Österreich in der zweiten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts.” Die Musikforschung 11 (3): 264–79.

Fétis, François-Joseph. 1867. Biographie universelle des musiciens et bibliographie générale de la musique. 2nd ed., vol 7. Firmin Didot.

Floirat, Bernard, Anetta Janiaczyk, Diana Ligeti, Nicolas Meeùs, Isabelle Poinloup, Marie-Laure Ragot, and Monika Stern. 1999. “La ‘gamme double française’ et la méthode du si.” Musurgia 6 (3): 29–44.

Freillon-Poncein, Jean-Pierre. 1700. La veritable manière d’apprendre à jouer en perfection du haut-bois, de la flûte et du flageolet. Jacques Collombat. Facsimile: Minkoff, 1971.

Frère, Alexandre. 1706. Transpositions de musique réduites au naturel. C. Ballard.

Gasparini, Francesco. 1708. L’armonico pratico al cimbalo. Antonio Bortoli. Facsimile: Broude, 1967.

Green, Robert A. 1979. “Annotated Translation and Commentary of the Works of Jean Rousseau: A Study of Late Seventeenth-Century Musical Thought and Performance Practice.” PhD diss., Indiana University.

Gruber, Albion. 1969. “Evolving Tonal Theory in Seventeenth-Century France.” PhD diss., University of Rochester.

Horsley, Imogene. 1967. Introduction to Charles Masson’s Nouveau Traité des regles pour la composition de la musique. 2nd ed. Da Capo.

Howell, Almonte C. 1958. “French Baroque Organ Music and the Eight Church Tones.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 11 (2–3): 106–18.

Janowka, Thomas Balthasar. 1701. Clavis ad thesaurum magnae artis musicae. G. Labaun. Facsimile: F. Knuf, 1973.

L’Affilard, Michel. 1705. Principes très-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique. 5th ed. C. Ballard. First published 1694. Facsimile: Minkoff, 1971.

Lester, Joel. 1978. “The Recognition of Major and Minor Keys in German Theory: 1680–1730.” Journal of Music Theory 22 (1): 65–103.

—————. 1989. Between Modes and Keys: German Theory 1592–1802. Pendragon.

Loulié, Étienne. 1696. Elements ou principes de musique mis dans un nouvel ordre. C. Ballard. Facsimile: Minkoff, 1971. Trans. and ed. by Albert Cohen as Elements or Principles of Music. Institute of Mediaeval Music, 1965.

Masson, Charles. 1699. Nouveau traité des regles pour la composition de la musique. 2nd ed. Paris: Ballard. Facsimile: 1967, Da Capo.

Mattax, Charlotte, trans. 1991. Accompaniment on Theorbo and Harpsichord: Denis Delair’s Treatise of 1690. Indiana University Press.

Mattheson, Johann. 1713. Das neu-eröffnete Orchestre. B. Schiller. Facsimile: G. Olms, 1997.

—————. 1739. Der vollkommene Capellmeister. Christian Herold.

Milliot, Sylvette. 1991–92. “Du nouveau sur Jean Rousseau, maître de musique et de viole (1644–1699).” Recherches sur la musique française classique 27: 35–42.

Nivers, Guillaume Gabriel. 1665. Livre d’Orgue Contenant Cent Pieces de tous les Tons de l’Eglise. The author and Ballard. Facsimile: J.M. Fuzeau, 1987.

—————. 1667. Traité de la Composition de Musique. The author and Ballard. Trans. and ed. by Albert Cohen as Treatise on the Composition of Music. Institute of Mediaeval Music, 1961.

—————. 1666. Méthode facile pour apprendre à chanter la musique. Par un Maistre celebre de Paris. R. Ballard.

Parker, Mark M. 1988. “Transposition and the Transposed Modes in Late-Baroque France.” PhD diss., University of North Texas.

Powell, John S., trans. 1991. A New Treatise on Accompaniment with the Harpsichord, the Organ, and with other Instruments. Indiana University Press.

Powers, Harold. 1998. “From Psalmody to Tonality.” In Tonal Structures in Early Music, ed. Cristle Collins Judd, 275–340. Garland.

Rameau, Jean-Philippe. 1722. “Supplément.” In Traité de l’harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels. J.B.C. Ballard. Facsimile: Broude, 1965.

Rousseau, Jean. 1683. Méthode claire, certaine et facile pour apprendre à chanter la musique. The author and C. Ballard.

—————. 1691. Méthode claire, certaine et facile pour apprendre à chanter la musique. 4th ed. The author and C. Ballard.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1768. Dictionnaire de musique. Veuve Duchesne. Facsimile: Actes Sud, 2007.

Saint-Lambert, Monsieur de. 1707. Nouveau traité de l’accompagnement du clavecin, de l’orgue, et des autres instruments. C. Ballard. Facsimile: Minkoff, 1972. Trans. and ed. by John S. Powell as A New Treatise on Accompaniment with the Harpsichord, the Organ, and with other Instruments. Indiana University Press, 1991.

Seidel, Wilhelm. 1986. “Französische Musiktheorie im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert.” In Geschichte der Musiktheorie, vol. 9, 1–140. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Simpson, Christopher. 1678. A Compendium of Practical Musick. 3rd ed. M[ary] C[lark] for Henry Brome.

Speer, Daniel. 1697. Grund-richtiger, kurtz, leicht und nöthiger jetzt wolvermehrter Unterricht der musicalischen Kunst. Kühnen.

Tolkoff, Lyn. 1973. “French Modal Theory before Rameau.” Journal of Music Theory 17 (1): 150–63.

Walther, Johann Gottfried. 1732. Musikalisches Lexicon, oder Musikalische Bibliothec. Wolfgang Deer.

Footnotes

* I would like to thank Peter Schubert for his generous advice on various aspects of this project as well as the anonymous reviewers of this article for their helpful responses. Translations from the French are mine unless otherwise indicated.

Return to text

1. As Horsley (1967, vii) has pointed out, Rousseau was preceded in this respect only by Christopher Simpson’s A Compendium of Practical Musick (London, 1678). See also Tolkoff (1973).

Return to text

2. For a still-pertinent survey of these multiple strands in France, as well as a useful inventory of seventeenth-century French treatises, see Cohen 1972.

Return to text

3. Banchieri called the church keys “tuoni ecclesiastici.” This brief summary of the emergence, nature, and dissemination of the church keys, as well as Table 1 below, draw principally on Harold Powers’s and Gregory Barnett’s much more comprehensive accounts thereof. See Powers 1998 and Barnett 1998, 2002.

Return to text

4. Walter T. Atcherson (1973), who initiated a wave of interest in these tonalities, initially called them “pitch-key modes”; Joel Lester (1978) coined the term “church keys.”

Return to text

5. On this topic, see Howell 1958.

Return to text

6. Nivers 1667, 18; trans. Cohen 1961, 18. “Les anciens nous ont prescrit douze Modes. Mais la plus commune division est des huit Modes ou Tons de l’Eglise.”

Return to text

7. On Rousseau’s biography, see Milliot 1991–92.

Return to text

8. Méthode claire, certaine et facile, Pour apprendre à chanter la Musique. Sur les Tons naturels & sur les Tons transposez; à toutes sortes de Mouvemens: Avec les Régles du Port de Voix, & de la Cadence, lors mesme qu’elle n’est pas marquée. Et un éclaircissement sur plusieurs difficultez nécessaires à sçavoir pour la perfection de l’Art. Trans. slightly modified from Green 1979, 186.

Return to text

9. This paradigm shift is discussed at more length in Seidel 1986 and Barnett 2002, 430–35.

Return to text

10. Lester 1989, 105; Federhofer 1958, 275. “Pro ultimo bin ich neben viellen anderen virtuosi der französischen Meinung, dass nit mehr als zwey Toni seindt, einer per B moll, der ander per quadro von ihnen genendt. V[erbi] g[ratia]: aus den D Moll oder D Duro, aus den G Moll oder G Duro und seze die Proba hierbey, dass ich aus den 2 Ton alle die 12, so ich auffgesetzt, heraus pringen kan.” For a discussion of the evolution of major-minor thinking in France before Rousseau, see Gruber 1969.

Return to text

11. The ongoing use and composition of modal chorales in Lutheran, German-speaking areas as late as Kirnberger was a factor in prolonging the prominence of modal theory in German writings.

Return to text

12. Rousseau 1691, 34–35 in the Éclaircissement; trans. Green 1979, 266. “Treizieme Question. Comment connoît-on qu’une Piéce de Musique est du premier Ton, du second Ton, etc. jusqu’au huitiéme. Cette question s’étend trop loin pour en donner l’explication dans toute son étenduë. . . . Cependant pour satisfaire en quelque maniere à cette demande, mais aussi pour ne pas m’étendre plus que je le dois dans cet ouvrage, je dirai seulement qu’une Piéce de Musique en D la ré mineur est du premier Ton, qu’en G ré sol mineur, elle est du second Ton, en A mi la mineur, elle est du troisiéme Ton, en E si mi mineur, elle est du quatriéme Ton.”

Return to text

13. “Cette question . . . regarde plus la Composition que le Chant. . . . Cela ne regarde pas cet ouvrage.”

Return to text

14. A thorough discussion of the concept of transposition in early French major-minor writings is found in Parker 1988.

Return to text

15. Rousseau, Preface to 1691; trans. Green 1979, 189. “Je fais en cela comme le Lierre, qui voulant pousser sa cime vers le Ciel, s’attache à un gros Arbre, l’embrasse, & à la faveur de cét appuy, se glisse & se pousse jusqu’à ses branches les plus élevées.”

Return to text

16. [Nivers], Preface to 1666. “Or est-il qu’il y a 7 sons differents dans la Musique: donc il doit y avoir 7 differents noms. Et par consequent il y a de l’abus & du defaut à l’ancienne Methode qui admet 7 sons, & n’admet que 6 noms.”

Return to text

17. Rousseau 1691, 5. “Il y a deux Voix; sçavoir b mol & b quarre: tout ce que l’on chante est par l’une ou l’autre des deux.” Rousseau would later call these voix “roads” (chemins; Rousseau 1691, 16 in the Éclaircissement).

Return to text

18. L’Affilard 1705, n.p.; Rousseau 1768, 226–27. As Floirat et al. remark, the disposition of this double scale led to the renaming of the notes in French writings. For example, the medieval denomination A la mi re became A mi la; G sol ré ut and G ut became G ré sol, etc. ( Floirat et. al. 1999, 31).

Return to text

19. [Nivers] 1666, 5. “Les Principes de la Musique sont establies sur la diversité des sons, & sur la varieté des figures. Ce sont ses deux parties, la diversité des sons regarde l’Intonation, & la varieté des figures regarde la mesure. Quant à la premiere partie, la Musique ne differe en rien du Plainchant, parce que l’Intonation est la mesme. . . . [E]n un mot le Plainchant est la premiere partie de la Musique; & quand on aura apris cette premiere partie, on ne sçaura justement que le Plainchant.” In the second part of the book, the author addresses the remaining “principles of music,” namely rhythm and meter.

Return to text

20. Rousseau, Preface to 1691, n.p.; trans. Green 1979, 189. “Des difficultez qui ont esté introduites depuis quelque temps dans la Musique, comme les différentes Transpositions, qui . . . font de la peine à plusieurs personnes.”

Return to text

21. My emphasis. Rousseau 1691, 25–26 in the Éclaircissement. “Il faut d’abord poser pour principe, qu’il y a des Tons naturels tant par b mol que par

Return to text

22. Nivers 1665. “Voix haultes telles que sont celles des Religieuses en faveur desquelles il faut transposer.”

Return to text

23. Rousseau does not use the natural key of A minor as a model for transposition, and does not justify his preference for the ré–ré scale over the la–la as the referential minor structure. Nor does he give special instructions regarding the solmization of A minor. With its empty signature, the latter thus belongs to the keys that are sung along the scale “par b quarre”: along with C major and D minor, C is do, D is ré, etc.

Return to text

24. Rousseau 1691, 22–23; trans. slightly modified from Green 1979, 204. “Pour chanter au naturel les Tons transposez en C sol ut Tierce mineure, & B fa si Tierce majeure, il faut dire Ut sur le degré où l’on diroit Si par b quarre, & de là procéder aux autres Notes sans s’embarrasser de la Clef & des bb qui dominent; & en F ut fa Tierce mineure, il faut dire Sol sur le mesme degré du Si. Aux Tons transposez par b quarre, il faut en G ré sol Tierce majeure dire Si sur le degré du Fa.” “Pour rendre cecy plus facile. Aux Tons transposez par b mol lorsque le b domine sur deux degrez différens, il faut dire Ut sur le degré où l’on diroit Si par b quarre. . . . Aux Tons transposez par b quarre, lorsque le Diéze domine sur un seul degré, il faut prendre Si sur ce mesme degré qui est celuy du Fa.”

Return to text

25. Rousseau 1691, 25 in the Éclaircissement. “Il est vray que l’on trouve souvent des Piéces de Musique où les b mols & les Diézes ne sont pas marquez regulierement aprés la Clef dans les Tons transposez, ce qui cause souvent de l’embarras à ceux qui apprennent, & qui les met dans l’impossibilité de pouvoir se servir des Regles que nous avons donné pour naturaliser les Tons transposez.”

Return to text

26. Preface to Rousseau 1691; Green 1979, 189. “Les différentes Transpositions . . . sans embarras, & d’une maniere fort naturelle.”

Return to text

27. Masson 1699, 9. “Les Anciens se servoient du terme de Mode, mais la plus grande partie des Modernes ont mis en usage celuy de Ton en la place de celuy de Mode, à cause que les differentes maniéres des Chants de l’Eglise s’appellent Tons. Mais afin de faciliter les moyens de parvenir plus promptement à la Composition, je ne montrerai que deux Modes, fçavoir le Mode majeur, & le Mode mineur.”

Return to text

28. Delair 1690, 54; trans. Mattax 1991, 131; Campion 1716, 14. “Sans ladite connoissance, il seroit impossible d’acompagner la pluspart des pieces Italiennes, d’autant que l’on en trouve souvent de transposées, où les bemols, ou diezes, naturels au ton dont est la piece ne sont point marquez.” “Tous les Italiens ne s’accordent point, pour armer leurs clefs. Les uns y mettent plus, ou moins de diézes, & de bèmols, que les autres . . . [c]e que je n’approuve point.”

Return to text

29. Frère 1706, 27–28. “Si tous les Bemols & les Diézes necessaires dans chaque modulation étoient mis prés de la clef dans leur juste quantité . . . mais la maniere d’écrire de ceux qui composent, nous jette quelquefois dans des difficultez.” Frère advocated Dorian signatures for all minor tonalities, a relatively outmoded stance by 1706. In addition to the question of complete/incomplete signatures, a number of signature inconsistencies could have visually puzzled musicians or created difficulties for beginners in deciphering the key. For example, a sharp or flat sometimes appeared in the signature on all the instances of a given pitch-class on a staff: e.g., in a piece with a two-flat signature, a bass clef could actually show three flats (low

Return to text

30. Parker has noted that “the usage versus the non-usage of Mixolydian signatures for the major tones seems to have been one of the chief distinctions between the notational practices of Italian and French musicians” (1988, 521). Let me emphasize that the topic at hand is standardization of key signatures. Notwithstanding which signature was used, composers and theorists could and of course did insert as many accidentals as needed for the requisite harmonies and melodies—in other words, a work in D minor with an empty signature would obviously not signify a diminished vi chord on the raised sixth degree.

Return to text

31. Campion 1716, 50. “Ainsi de modulation en modulation, il pourroit metre des bémols jusqu’aux Petites Maisons.” The Petites Maisons, a Paris asylum then situated on the rue de Sèvres, welcomed the insane, paupers, and patients suffering from venereal diseases until end of the eighteenth century.

Return to text

32. Rousseau 1691, 26 in the Éclaircissement. “C sol ut mineur, ou tierce mineure, c’est la mesme chose.”

Return to text

33. Masson wrote: “On pourra dire, pour faire entendre le Mode majeur, tierce majeure, & pour faire entendre le Mode mineur, tierce mineure” (1699, 12).

Return to text

34. Campion 1716, 13. “La sixiéme du ton mineur en descendant est le bémol . . . C’est sans doute cette consideration, qui fait mettre à beaucoup d’Italiens un bémol à la clef dans l’octave du ré, ce qui ne me paroît pas juste, en ce que, de la dominante ou de la cinquiéme du ton, on monte à la huitiéme par degrez majeurs, en passant sur le diéze sensible de l’octave; & on descend par degrez mineurs en passant sur le bémol . . . ; par consequent le bémol ne doit point estre [à] la clef, puisqu’il est accidentel . . . Dans l’octave du la, le fa est diéze en montant, & en descendant il est naturel, & est sensé bémol.”

Return to text

35. These terms were already in use in the modal vocabulary of Salomon de Caus and Antoine Parran.

Return to text

36. Delair’s singling out of the first, third and fifth degrees as cadence points in both major and minor keys goes back to Zarlino’s modal teachings, but theorists of Delair’s generation broke with that tradition. Masson, for example, precludes cadences on the mediant in the major. Masson 1699, 21–22.

Return to text

37. The concept of cordes essentielles returned, this time specifically in relation to mode, in Sébastien de Brossard’s article MODO in his Dictionnaire de Musique (first edition in 1703). By introducing a new variety of cordes, the “natural” ones that raise the leading-tone and lower the submediant in minor, Brossard can be credited as the first French theorist to present a description of the harmonic minor. See Brossard 1705, 50.

Return to text

38. Saint-Lambert 1707, 26; trans. Powell 1991, 47–48. “Le Mode d’un Air est majeur quand la tierce, la sixiéme, & la septiéme de la finale ou note tonique sont majeures. Le Mode est mineur quand la tierce, la sixiéme, & la septiéme de la finale sont mineures. La seconde, la quarte, la quinte, & l’octave sont de la même espece dans le Mode majeur, que dans le mineur.”

Return to text

39. Though in the body of the Traité Rameau does use Dorian signatures, he specifies in the Supplément that he did so in order to conform to common use and to avoid coming across as a pesky reformer (un réformateur ennuyeux). It is better, he explains, to model all minor keys on A minor and solmize their tonic as la, and he lists the twenty-four major and minor keys with their “modern” signatures.

Return to text

40. For a detailed discussion of Rousseau’s transposition models, see Parker 1988, 345–56.

Return to text

41. Since Rousseau allows natural keys to have one flat, the key of

Return to text

42. Saint-Lambert 1707, 27; trans. slightly modified from Powell 1991, 49–50. “Parmi ces tons il y en a . . . même quelques uns qui n’ont peut-être jamais été mis en œuvre; mais je n’en ay voulu omettre aucun dans la Demonstration, parceque la plus part de nos Compositeurs en employant maintenant plusieurs qui n’étoient point en usage auparavant, il se pourra bien faire qu’ils viendront enfin à les rendre tous aussi communs les uns que les autres.”

Return to text

43. Saint-Lambert 1707, 26; trans. slightly altered from Powell 1991, 48. “Il y a neanmoins des modulations qu’on sousentend ordinairement sans les exprimer, parce qu’on les regarde comme naturelles à certains tons. Quand on dit qu’un Air est en C Sol Ut, sans parler de sa modulation, on sousentend qu’elle est majeure. Quand on dit qu’il est en Re La Re, on sousentend que son mode est mineur.”

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits:

14247