Finding Love in Hopeless Places: Complex Relationality and Impossible Heterosexuality in Popular Music Videos by Pink and Rihanna

Marc Lafrance and Lori Burns

KEYWORDS: Pink, Rihanna, music video, popular music, cross-domain analysis, relationality, heterosexuality, liquid love

ABSTRACT: This paper presents an interpretive approach to music video analysis that engages with critical scholarship in the areas of popular music studies, gender studies and cultural studies. Two key examples—Pink’s pop video “Try” and Rihanna’s electropop video “We Found Love”—allow us to examine representations of complex human relationality and the paradoxical challenges of heterosexuality in late modernity. We explore Zygmunt Bauman’s notion of “liquid love” in connection with the selected videos. A model for the analysis of lyrics, music, and images according to cross-domain parameters (thematic, spatial & temporal, relational, and gestural) facilitates the interpretation of the expressive content we consider. Our model has the potential to be applied to musical texts from the full range of musical genres and to shed light on a variety of social and cultural contexts at both the micro and macro levels.

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1.1] This paper presents and applies an analytic model for interpreting representations of gender, sexuality, and relationality in the words, music, and images of popular music videos. To illustrate the relevance of our approach, we have selected two songs by mainstream female artists who offer compelling reflections on the nature of heterosexual love and the challenges it poses for both men and women. Unlike many love songs in the pop genre, Rihanna’s “We Found Love” (2011) and Pink’s “Try” (2012) do not romanticize relationships by perpetuating gender stereotypes and reinforcing clichés of heterosexual intimacy. Instead, the songs explore the struggle faced by both partners as they come to grips with the implications of intense emotional connection. In fact, we argue that each of the songs, and their accompanying videos, can be seen as powerful commentaries on love in late modernity—that is, at a time when conventions of gender and sexuality are in flux due to the rapidly changing nature of economic structures and social roles (Rosin 2012). Through a multi-layered integration of lyrics, music, and images, these commentaries defy dominant ideologies of gendered subjectivities and sexual normativities in the context of romantic love.

[1.2] The two videos share a number of common elements on the levels of form and content. With respect to form, both videos unfold in bleak and transient settings, both use color to express elevated states of feeling, and both show the vicissitudes of love to be intensely embodied experiences. With respect to content, both videos represent the male and female partners as engaged in a quest for sustainable relationships, both link sexual passion with physical aggression, both connect ecstasy and euphoria to conflict and destruction, and finally, both eschew a narrative of male domination and female subordination in favour of one of equal partnership—one in which men and women bear equal responsibility for a relationship’s successes and failures as well as its pleasures and pains. Of course, we are not suggesting that power relations privileging men and marginalizing women no longer exist. What we are suggesting, however, is that stories of male privilege and female marginalization are not the ones being told in these videos. They will, therefore, not be our focus here. Instead, our focus will be on making sense of how complex relationalities are bound up in the lived experience of heterosexual love as it is represented in these music videos by Pink and Rihanna.

Context: Love Songs in Late Modernity

[2.1] Popular musicologist Simon Frith declares emotions to be significant for popular music scholarship. More specifically, he claims that music is—first and foremost—“a way of managing the relationship between our public and private emotional lives” (Frith 2004, 39). Turning shortly thereafter to the subject of love songs, he explains:

It is often noted but rarely discussed that the bulk of popular songs are love songs. This is certainly true of twentieth-century popular music in the West; but most non-Western popular musics also feature romantic, usually heterosexual love lyrics. This is more than an interesting statistic; it is a centrally important aspect of how pop music is used. Why are love songs so important? Because people need them to give shape and voice to emotions that otherwise cannot be expressed without embarrassment or incoherence. Love songs are a way of giving emotional intensity to the sorts of intimate things we say to each other (and to ourselves) in words that are, in themselves, quite flat (39).

[2.2] Despite Frith’s claim that love is an important part of what propels popular music, representations of it have received relatively scarce attention in the academic literature. With the exception of Martin Stokes’s (2010) study of love as a form of cultural expression and B. Lee Cooper’s (2015) study of romance recordings, there has been very little work done on how love is represented in popular music, and even less on how these representations are bound up with issues of gender and sexuality. Our work seeks to fill this significant gap in the scholarship.(1)

[2.3] To fully understand the love songs of interest to us, it is important to situate them in the context of contemporary trends in popular music studies. In a recent article, Madaninka and Bartholomew (2014) examine top-40 chart data from 1971 to 2011 in order to track lyrical emphasis on lust (i.e., sexual desire) and/or love (i.e., romance). The authors demonstrate a significant shift in the topical focus of love songs, from a period of “love” themes in the 70s to 90s to a period of “lust” themes in the early postmillennium.(2) There can be no doubt that “Try” and “We Found Love” emerge at a moment when lyrics relating to love are on the decline and lyrics relating to lust are on the rise. Both songs buck this trend by exploring love relationships without exploring sexual desire. And although the video images associated with the songs do suggest sexual activity, this activity takes place in a context that is clearly characterized by romance.

[2.4] While it may be productive to consider how “Try” and “We Found Love” connect to the thematic trends identified by Madaninka and Bartholomew, the music analyst is in need of a more developed theoretical toolkit in order to fully understand the representations of gender, sexuality, and relationality that characterize the videos in question. We thus turn our attention now to the theoretical writings that have helped us to make sense of these representations.

Theory: Love and The Cultural Politics of Emotion

[3.1] When feminist media theorists study music videos, they often focus on how women are both subjected to and the subjects of power relations that grow out of what bell hooks (hooks 1997) calls “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” Concentrating on how women are represented in a range of sexist, heterosexist, and racist ways, feminist media theorists tend to avail themselves of theoretical tools such as the male gaze (Mulvey 1975, Kaplan 1987, Sturken and Cartwright 2009); the male imaginary (Jhally 2007); and symbolic annihilation (Clément 1979). All of these tools allow us to think critically about how “regimes of representation” (Attwood 2005) rely on gendered, sexualized, and racialized dynamics of domination and subordination. And while they are appropriate for making sense of macro-level phenomena relating to issues of power and discourse, they are somewhat less appropriate for micro-level phenomena relating to issues of experience and feeling. In other words, the feminist media-studies toolbox is unlikely to allow us to fully understand the representations of the challenges posed by intimacy and love in the two selected videos, particularly since these representations do not appear to be mediated in any meaningful way by oppressive overarching norms and values.

[3.2] With their emphasis on the personal experience of love, the songs we have chosen for analysis do not offer much in the way of opportunities for thinking about gender and sexuality in macro terms. And since feminist analyses of popular music in particular and popular culture in general tend to focus on the macro (i.e., power and discourse) more than the micro (i.e., experience and feeling), different analytical tools are required to think about the inner struggles that pervade songs like “Try” and “We Found Love.” Once again, this is not to say that the macro and the micro are not always already embedded in and entangled with one another. But feminist analyses that privilege the micro over the macro are rare in the burgeoning area of critical heterosexuality studies (Ingraham 1999 and 2005, Jackson 1999, Otnes and Pleck 2003). Our approach to the selected videos is original, at least in part, because it looks closely at the emotional and the intimate without losing sight of the ideological and the institutional.

[3.3] In order to better account for the micro-level experiences represented in “Try” and “We Found Love,” without losing sight of macro-level factors such as social and cultural context, we turn to the work of feminist cultural theorist Sarah Ahmed. In her influential book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Ahmed explores the structures and functions of powerful feelings such as love and hate, attraction and fear, desire and disgust. Writing in particular about the complexities of love as they relate to human experience, she explains: “[Whilst] love may be crucial to the pursuit of happiness, love also makes the subject vulnerable, exposed to, and dependent upon another, who in ‘not being myself’, threatens to take away the possibility of love” (2004, 125). Ahmed’s goal is to understand the social significance of feeling; that is, how individual experiences of emotion impact collective processes. More specifically, her aim is to “consider how the pull of love towards an other, who becomes an object of love, can be transferred towards a collective, expressed as an ideal or object” (124). In this way, Ahmed takes up the personal in order to better understand the political. Like Ahmed, Judith Butler sees love in far-reaching social terms. For Butler, love is inextricably bound up in the interactive and the intersubjective insofar as “[it] is not a state, a feeling, a disposition, but an exchange, uneven, fraught with history, with ghosts, with longings that are more or less legible to those who try to see one another with their own faulty vision” (2002, 64). For both Ahmed and Butler, then, love is seen to unfold in and through a variety of intersecting contexts. As a result, representations of it ought to be taken seriously by those interested in the study of gender and sexuality in popular music. Since music videos often explore human subjectivities as they are made and broken by romantic relationships, they are important sites for understanding both the individual and collective complexities of heterosexual love.

[3.4] While feminist cultural theorists inform our approach in all of the ways outlined above, it is the work of contemporary social theorist Zygmunt Bauman that seems to resonate most strongly with the video analyses presented in this study. Part of his far-reaching account of liquid modernity (2000), Bauman’s conceptualization of liquid love (2003) vitally informs our interpretative approach. In the following paragraphs, we outline the key elements—ambivalence and ambiguity, uncertainty and mobility, and insecurity and vulnerability—of Bauman’s definition of liquid love. With these elements in view, we then show how they can be used to make sense of what we see as “complex relationality” and “impossible heterosexuality” in the music videos by Pink and Rihanna.

[3.5] Ambivalence and Ambiguity. For Bauman, liquid love is characterized by a series of paradoxical impulses. In the introduction to his monograph, he writes:

This book’s central characters are men and women, our contemporaries, despairing at being abandoned to their own wits and feeling easily disposable, yearning for the security of togetherness and for a helping hand to count on in a moment of trouble, and so desperate to ‘relate’; yet wary of the state of ‘being related’ and particularly of being related ‘for good’, not to mention forever . . . (2003, viii).

Bauman goes on to argue that “in a liquid modern setting of life, relationships are perhaps the most common, acute, deeply felt, and troublesome incarnations of ambivalence” (viii). For Bauman, contemporary subjects are deeply invested in trying “to force [a] relationship to empower without disempowering, enable without disabling, fulfilling without burdening” (ix), even if doing so is, ultimately, impossible. Characterized by circularity and repetition, liquid love is fundamentally ambiguous.

[3.6] Uncertainty and Mobility. Like the inhabitants of liquid modern societies, liquid love is always on the move, propelled more by “connections” and “networks” than by secure attachments or lasting commitments that might once have been concretized in and formalized by solid social structures such as marriage and family. Bauman writes: “Perhaps this is why, rather than report their experience and prospects in terms of ‘relating’ and ‘relationships’, people speak ever more often

Being on the move, once a privilege and an achievement, becomes a must. Keeping up speed, once an exhilarating adventure, turns into an exhausting chore. Most importantly, that nasty uncertainty and that vexing confusion, supposed to be chased away thanks to speed, refuse to go. The facility of disengagement and termination-on-demand do not reduce the risks; they only distribute them, together with the anxieties they exhale, differently (xiii).

Suspended between wanting desperately to connect with others while at the same time wanting to remain free of the meaningful constraints that such a connection requires results in uncertainty: the lovers never know what, if anything, comes next as “next” no longer takes the solid, stable, and structural forms it once did.

[3.7] Insecurity and Vulnerability: Given its contradictory and mobile nature, it only stands to reason that liquid love is characterized by insecurity. Bauman claims that, in a liquid modern society, contemporary subjects are constantly in search of something to hold onto—something that will anchor them in solidity as they float about in a sea of liquidity. Often these subjects try to find security in love only to discover that, in its liquid forms, love augments rather than diminishes insecurity. Love leads to insecurity, according to Bauman, because it both creates and demands vulnerability. As Bauman puts it: “To love means opening up to that fate, that most sublime of all human conditions, one in which fear blends with joy into an alloy that no longer allows its ingredients to separate” (2003, 6–7). But in a society that seems less and less interested in secure or long-term attachments, the vulnerabilities associated with love give rise to a series of relational dilemmas; namely, that of trying to participate in love without seeking to control the other or be controlled by him or her. Love invites us to try to control it so that we might minimize our losses, but the minute we are successful in controlling it, love recedes and retracts. Love, and particularly liquid love, is in this way impossible.

Method: Doing Cross-Domain Analysis

[4.1] In order to explore the representations of liquid love in the selected videos, we apply an analytic model that allows us to interpret the constitutive elements of the lyrics, music, and images. The model allows us to reflect critically on the expressive content of these three domains according to four crosscutting parameters: thematic, spatial & temporal, relational, and gestural.(3) These parameters have been devised to facilitate the analysis of the dynamic workings of subjectivity and relationality. By applying these parameters to the video materials, we are able to consider the three domains at the same time and, in doing so, to account for their intricate and intersecting meanings in systematic terms.

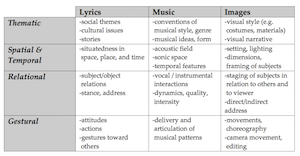

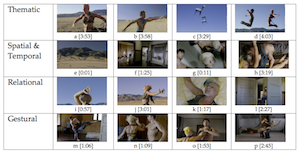

Figure 1. Cross-Domain Analysis Model

(click to enlarge)

[4.2] Figure 1 presents the three domains, and identifies relevant content therein, according to the four cross-domain parameters. The thematic parameter considers the social themes, cultural issues, and stories told in the lyrics; the conventions of style and genre in the music as well as the musical ideas and form; and the visual style and narrative of the video images. The spatial & temporal parameter considers the subject’s situatedness in terms of space, place, and time in the landscape of the lyrics; the placement of the musical sounds within the acoustic field as well as the sonic space and temporal features; and the setting and lighting of the video as well as its dimensions and framings. The relational parameter considers the ways in which the subjects interact with one another: it tracks the subject/object relations described in the lyrics as well as the stance and address of the subjects; the vocal and instrumental interactions in the musical texture as well as the dynamics, quality, and intensity of the interactive expressions; and the staging of the subjects in the visual field as well as how they relate to the camera in direct or indirect address.(4) And finally, the gestural parameter considers the attitudes and actions of the subject in the lyrics, the delivery and articulation of the musical patterns, and the physical movement and choreography of the subjects in the visual images as well as the mobility of the camera and the editing of shots. These four cross-cutting parameters serve to channel our interpretation of the expressive content of music videos so that we can understand it in relation to the elements of liquid love identified earlier: ambivalence and ambiguity, uncertainty and mobility, and vulnerability and insecurity. Ultimately, our analytic goal is to explore the cross-domain parameters so as to better understand the challenges of human relationality that are brought into view by the videos “Try” and “We Found Love.”

Analysis 1: Pink’s “Try” (The Truth About Love, 2012)

Contexts

[5.1] The Truth About Love was released in September 2012 as Pink’s sixth studio album and first #1 Billboard hit.(5) The album yielded six singles, four of which were released as videos. The world tour ran from February 2013 to January 2014, with over 140 shows. A live DVD of the Melbourne installment of the tour was released in November 2013.

[5.2] Throughout the album, Pink reflects on the complexities of love and, in doing so, questions its capacity for sustainability in the long term. Like her previous albums, The Truth About Love resists stereotypical representations of women and heterosexual relationships. Honesty is one of the themes that recur in the critical reception of the album. As Entertainment Weekly’s Kyle Anderson puts it, “Instead of playacting the expected pop archetypes—brat, vixen, victim—she presents herself as, well, herself: a knockabout girl who has done some living, not a precocious cipher playing a well-rehearsed role” (2012). The album was, moreover, widely celebrated for working against cultural conventions associated with pop. As Steven Erlewine writes, “nothing about it is neat, it shifts courses and refutes itself, it’s ‘nasty and salty,’ as Pink herself sings about true love. It’s weird and wilfully, proudly human, a big pop album about real emotions and one of Pink’s wildest rides” (2016).

[5.3] Presented as the third track of the album and released as the second single and video, the song “Try” asks difficult questions about whether lasting love is, in fact, possible.(6) The song was heralded as a power or stadium ballad, as Robert Copsey makes clear in his review for Digital Spy: “Future single ‘Try’ is a ballad of the stadium-filling, lighter-waving variety

[5.4] Directed by Floria Sigismondi, choreographed by the Golden Boyz, and featuring male dancer Colt Prattes, the video for “Try” was acclaimed for its artistic production and demanding dance form.(7) As Montgomery explains on MTV.com: “It is big, it is beautiful, it is definitely a work of art, and it is uniquely, unquestionably Pink. She pushes herself—and, really, the entire concept of what a pop video can be—to the limit, and pulls it off with effortless grace.” Despite the considerable athleticism demanded by the video, the artist staged a live performance of the song and its dance choreography at the American Music Awards in 2012.

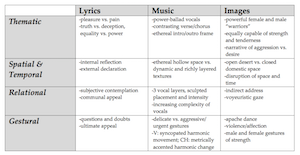

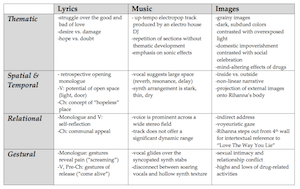

Figure 2. Summary of Cross-Domain Analytic Content for “Try”

(click to enlarge)

[5.5] In what follows, we present our cross-domain analysis in order to show exactly how Pink represents human relationalities and the possibilities—or, perhaps more precisely, impossibilities—of heterosexual love. Figure 2 summarizes the expressive content for “Try” according to the domains and parameters of the analytic model.

Lyrics

[5.6] The thematic elements of the lyrics suggest that experiences of both pleasure and pain are endemic to love (http://genius.com/Pink-try-lyrics). This suggestion is especially evident in the chorus, where the subject declares that the experience of desire causes harm. The song’s lyrics do more asking than answering, refusing to settle the issues they raise—issues such as how a love’s truths can “turn to lies” and why the passion with which love is associated seems to “come so easily” even when it is “not right.” In keeping with Bauman’s emphasis on the ambivalence of liquid love, the lyrics leave the listener not with a comforting resolution but with a series of unsettling contradictions suspended somewhere between elation and disappointment, desire and destruction, truth and deception. Like its thematic elements, the song’s spatial & temporal attributes are characterized by the uncertainty and mobility of liquid love. More specifically, the lyrics do not seem to be set anywhere in particular; there are no references to specific spaces or places. Instead, these settings need to be deduced through the lyrical statements, which are inwardly directed over the course of the verses (“sometimes I think that it’s better to never ask why”) and outwardly directed in the chorus (“you gotta get up and try”). Similarly, the lyrics give us no clear indication of the song’s temporality. Far from telling us a linear story with a beginning and an ending, the lyrics seem to indicate that the temporality in question here is circular in its repetitive sequence of love’s successes and failures. With respect to the song’s relational features, the verses represent the subject’s self-reflexivity as she contemplates her own experience, while the choruses reveal the subject’s communal address as she encourages the listener to keep believing in love. The gestural aspects of the lyrics illuminate a subject poised between individual actions that reflect the vulnerability and insecurity of liquid love in the verses (doubting, hoping, questioning, and regretting) and collective action in the chorus.

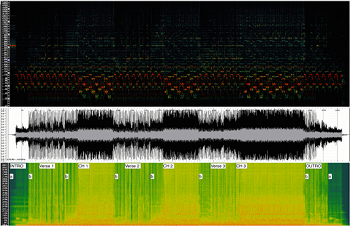

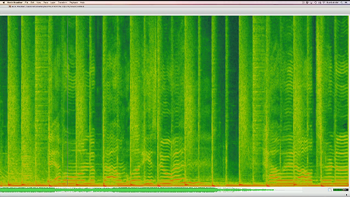

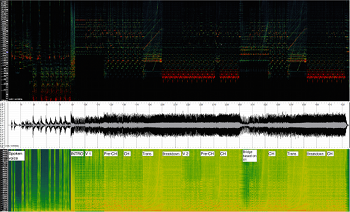

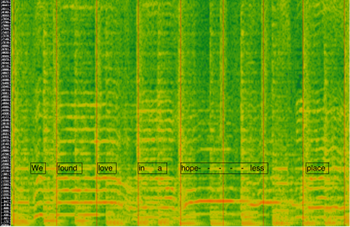

Figure 3. Pink, “Try,” Spectrograph and Wave Images (derived from Sonic Visualiser: peak frequency layer at 6500 Hz, wave layer, spectrum layer at 9000 Hz)

(click to enlarge)

Example 1. Sound clip of “Try,” intro, first section (a) (0:01–0:09)

Example 2. Sound clip of “Try,” intro, second section (b) (0:14–0:18)

Example 3. Sound clip of “Try,” verse 1, phrase 1 (0:24–0:28)

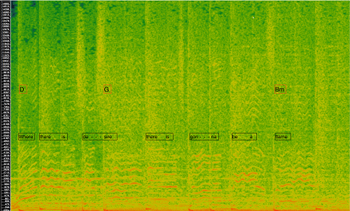

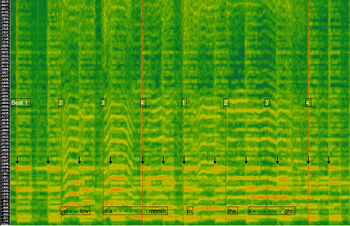

Figure 4. Verse 1, Phrase 1 (15 KHz)

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. Sonic Visualiser clip (spectrograph) of “Try,” verse 1, phrase 1 (0:24–0:28)

(click to watch video)

Figure 5. Chorus 1, Phrase 1 (15 KHz)

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Sound clip of “Try,” chorus, phrase 1 (0:50–0:55)

Example 6. Sonic Visualiser clip (spectrograph) “Try,” verse 1, phrase 1 (0:24–0:28)

(click to watch video)

Figure 6. Repetition of “try” in Chorus 1 (1:06)

(click to enlarge)

Example 7. Sound clip of “Try,” from chorus 1 (“try, try, try”) (1:06–1:09)

Example 8. Sound clip of “Try,” from chorus 2 (“try, try, try”) (2:08–2:11)

Example 9. Sound clip of “Try,” from chorus 3 (“try, try, try”) (3:06–3:09)

Figure 7. Video Stills from “Try”

(click to enlarge)

Music

[5.7] The overall musical form of the song is illustrated in Figure 3, with spectrographic images and the amplitude wave to offer a visual representation of the sound.(8) The reader is encouraged to listen to the music video track on Pink’s VEVO site, available here: (http://www.vevo.com/watch/pink/Try/USRV81200291).

[5.8] The first section (a) of the song intro (which begins at 0:01 in the music video) presents a low rounded bass against a high-register tremolo guitar and distant dark high-register piano (listen to Example 1).(9) There are no sounds in the mid-register, leaving a hollow and ethereal space. The second half (b) of the intro (0:15) introduces a dry forward kit that features an aggressive kick drum locked with the bass, a snare backbeat that allows the snare to sustain, and a distant vocal cry, “ah” (listen to Example 2).

[5.9] The hollow and ethereal effect of the intro is heard in strong contrast to the verse (0:24), which introduces a mid-register vocal (in the range of D4 to A4) characterized by a long and lush reverb. We hear the delay very clearly at the tail of each vocal phrase (listen to Example 3). Adding further depth to the lead vocal is an overdubbed layer an octave below to produce the effect of a vocal shadow. The layered vocals, in addition to the kit and bass, are centered in the mix and very focused, creating a mono effect. The spectrograph in Figure 4 shows the first phrase of the verse, revealing the prominence of the vocal, which has intensity in the mid-register that carries into the higher partials. The transparent texture allows for the full bloom of the vocal sound (watch Example 4), exposing the subject’s vulnerable self-questioning.

[5.10] The chorus (0:50) offers dynamic intensity, rich layers, a wide stereophonic spectrum, and an expanded pitch register. The opening phrase of the chorus, shown in Figure 5, features a resonant bass now doubled at the octave below and a denser texture that is filled out by the synths (listen to Example 5 and watch Example 6). Cutting through the dense texture, the heavily compressed and overdubbed lead vocal emerges powerfully in the upper octave (on D5). Still followed by its shadow, the lead vocal now occupies the full breadth of the stereo spectrum, as the vocals are both centered and panned left and right. The exception here is the word “try” (Figure 6): for this word, and its repetitions, the voice returns to the centered position and the overdubbing is stripped back to create a more intimate effect (listen to Example 7). We interpret the contrast between the expansive and intimate vocals as a musical representation of the subject’s efforts to strive for security despite the conditions of liquid love. As Bauman writes, “[Humans] of all ages and cultures are confronted with

[5.11] Also contributing to the intensity of the repeated vocal declaration “try” is its harmonic support. The harmonic design features a tonal ambiguity that is not uncommon in the pop-rock genre.(10) The verse is based on a two-bar progression that is heard four times. The progression, summarized as Bm–G–D / D–A–Bm, oscillates between B minor and D major in a way that leaves the question of tonal focus unresolved. The four-bar chorus pattern (G–D–A–Bm), heard three times, does not clarify the ambiguity. Although the vocal melody of the chorus outlines the harmony of D major (emphasizing D5, A4,

[5.12] As shown in Figure 3, the intro, verse, and chorus materials form the basis of the song. A structural frame is created by the return of the intro material (in reverse order) at the end of the song, and material from the intro (b) also returns before and after chorus 1 and chorus 2. The third verse and chorus are presented without the interruption of the intro phrase (b), allowing for an intensification of the vocal presentation in a narrative that we will describe below.

[5.13] The song develops a vocal narrative that contrasts the verse’s centered vocal—enhanced with lush reverb and shadowed by a lower vocal layer—with the chorus’s heavily compressed and overdubbed vocal that fills the stereo spectrum. In the second chorus the two vocal layers are enriched by a third vocal layer, which serves as a harmonizing upper line. For the third (and final) verse and chorus, that upper vocal layer is itself overdubbed to become a strong force in the vocal texture. Especially since there is no formal return to the quieter intro material between the final verse and chorus, this third vocal layer is allowed to increase in intensity and complexity, developing momentum throughout this final section of the song. In order to hear the trajectory of this accumulating vocal texture, the listener can compare the vocal layering in chorus 1 (listen again to Example 7) to the equivalent passages in chorus 2 (Example 8) and chorus 3 (Example 9).

[5.14] Having outlined the music-analytic content, we can now apply the cross-domain model. Returning to Figure 2, the thematic parameter leads us to reflect on the song’s style and genre. As we interpret the genre of a song, we connect it to music with which we are already familiar and, in doing so, identify the intertextual links that make these connections possible. As Jason Toynbee writes: “the new is generated through the selection, combination, and re-voicing of what is already there” (2001, 9). Here the song’s contrast between verse and chorus is a pop-rock convention. The fact that Pink makes use of this convention appears to account for why Cameron Adams (2012) refers to the song as “jacked-up 80s FM rock.” A power ballad that runs at a BPM of 104, the song can certainly be connected to earlier power ballads such as the Scorpions’ “Still Loving You” and Whitesnake’s “Is this Love?”(11) “Try” uses a similar strategy of contrast in the verse-chorus structure. As summarized in Figure 2, the song is framed by the ethereal texture of the opening and closing sections. The spatial & temporal parameter exposes the ethereal, hollow space versus the layered textures, and the centered focus versus the wide stereo spectrum. It also allows us to apprehend how the moderate tempo opens up temporal space for nuanced expression. Furthermore, Pink mobilizes her vocal space effectively to focus on the lower register (D4) in the verse structure and then expand her pitch space to the upper octave (D5) in the chorus. The relational parameter heightens our sensitivity to the interactions between and among the multiple vocal layers and the gradual intensification of the vocal texture in each successive verse-chorus statement. Finally, the gestural parameter facilitates analytic reflection on the gestural content of the song: for instance, the delicate gestures of the intro (a) in opposition to the urgency of the kit in the second part of the intro (b). It is through this analytic lens that we can also consider the harmonic gestures of the song; the ambiguity of tonal function between D and Bm and the contrapuntal tension between the vocal melody and its harmonic support lead the listener—as we are pulled along by the compelling counterpoint—to experience the effort that is the very theme of the song.

Images

[5.15] Figure 7 reproduces still images from the video organized within the parameters of the analytic model. Here the thematic parameter shows us male and female lovers as warriors in spaces that are derelict and desolate; they are anonymous and lonely places where we do not expect to find kinship ties or social bonds of any kind. Colorful dry paint is used throughout the video to mark the bodies of the female and male dancers. The paint accumulates on the surface of their skins as they make contact and, in doing so, inscribes and transcribes the history of their emotional interaction. These images establish the visual metaphor of love as a battlefield. The video’s story ends in a desert and shows two chairs thrown into the air. The female and male dancers then run towards one another, jumping high into the air, and moving quickly across the sky as they embark on a course that will almost certainly result in a crash. We never see the crash. The story is never resolved. The image of the two bodies up in the air, moving closely towards one another in what promises to end in a collision, is a symbolic representation of the uncertain nature of the relationship and all of its shifting possibilities and impossibilities.

[5.16] The space & time parameter invites us to observe how the video disrupts our understanding of conventional space. We see, for instance, images of the female and male subjects duplicated in an angled mirror, causing us to reflect on the self/other distinction, the split nature of subjectivity and the ambiguous staging of the bodies in space. In another scene, the image is inverted in such a way that the bodies appear to be occupying an impossible position, which makes us question who is in control and who is to blame for the conflict unfolding in front of us. Simply put, the video images represent the intense push and pull of the relationship—a relationship that is at once life-affirming and life-threatening as it plays out in and through a field of extreme stimulation and deep dissatisfaction.

[5.17] The relational parameter turns our attention to the fact that Pink—the performer—never emerges from behind the fourth wall nor gazes into the camera directly. We are given a voyeuristic window into the struggles of the relationship, but we do not make contact with the subjects of the story. What is more, the struggles between the subjects create a relational context in which each of the partners has all and none of the power. The balance of power between them shifts constantly, with both and neither of them emerging as the winner or the loser.

[5.18] Before the final scene, set in the empty desert, the video takes place in an abandoned, ramshackle house. Here the gestural parameter asks us to attend to the danse apache that the female and male dancers perform in the remote and unfinished home. Juxtaposing brutality and aggression with attraction and desire, the danse apache—which originated in early 20th century Paris—typically features a prostitute being treated violently by her pimp. During the 20th century, this dance form was adapted to a number of popular cultural contexts, including burlesque and cabaret, cartoons, and mainstream movies.(12) A well-known example can be found in one of the scenes from the film Moulin Rouge! (2001) and is based on the song “Roxanne” by The Police (1978).(13) Pink’s performance of the danse apache is interesting to us precisely because it does two key things for the video: first, it once again uses visual metaphor to allude to the fact that love is at once a completely intoxicating and enormously dangerous dance; and second, it shows us that both partners are agents with respect to what takes place between them. More specifically, the video suggests that while each partner is devoted and passionate, he or she is also cruel, demanding, and frightened. Both lovers show signs of tenderness and concern while at the same time engaging in aggressive and surprisingly violent acts. The male dancer does not appear to have greater control over the female, as was typical of the danse apache form. In Pink’s modern performance, many of the traditional gestures are borrowed, but the female dancer emerges with greater power and physical strength.

Interpretive Summary

[5.19] After having considered the domains of lyrics, music, and images individually, we will now illustrate how they can be understood to intersect. As we have already mentioned, our goal is to reveal how the constitutive elements of each domain shape and are shaped by the others. Pursuing the parameter of thematic content across the three domains in Figure 2, we see the lyrics juxtaposing pleasure and pain while pitting truth against deception and equality against power. These thematic lyrical contrasts are supported by music that is characterized by an oppositional orientation, insofar as it features the contrasting verse-chorus style of “jacked-up 80s FM rock.” Strengthening that effect, a strong formal opposition is also created by the contrast of the ethereal intro and outro that frame the dynamic verse-chorus form. In keeping with the theme of contrast and contradiction, the images juxtapose aggression and strength with vulnerability and tenderness. The spatial & temporal parameter allows us to connect the internal/external conflict of the lyrics with the extreme textural contrast in the music, as well as the visual contrast between the domestic environment and desolate desert space. The relational parameter reveals how the self-reflexive nature of the lyrics is transformed into a multi-layered vocal presentation in which the primary voice is shadowed, overdubbed, and harmonized to convey the intensity and complexity of the subject’s struggle. In the visual sphere, the retention of the fourth wall is consistent with the micro-level intimacy that the video represents. Finally, the gestural parameter facilitates analytic reflection on the nuanced impulses of the song. The musical effects of push and pull are in keeping with the lyrical doubts and appeals, as well as the visual representation of violence and affection that are central to the danse apache. The cross-domain analysis thus facilitates reflection on the connections between the expressive content of lyrics, music, and images, yielding a systematic interpretation of their multimodal intersections.

[5.20] Relying on a range of conventions that are grounded in the pop-rock genre, this music video tells a story of female and male lovers who are capable of not only extreme strength and aggression, but also tenderness and vulnerability. The message that emerges in and through the music video is one of an endless series of negotiations. By means of its intensely embodied dance choreography and the constantly shifting power relations between the two characters, the video makes clear that the lovers have no choice but to “try” to make love work. Both the woman and the man in this video are depicted as agents with fierce determination, irrepressible passion, and well-developed physical strength. At the same time, however, this is not a caricatured representation of heterosexual love. Instead, the multi-faceted and multi-layered expressive content of the video makes clear that love is a site of sometimes compulsive, often conflicted, and, above all, constantly changing relations.

Analysis 2: Rihanna’s “We Found Love” (Talk That Talk, 2011)

Contexts

[6.1] Rihanna’s sixth studio album, Talk That Talk, was released in November 2011. Though it did not reach the top spot on the U.S. Billboard 200, it debuted at #3 and reached #1 in several other countries, including Australia, Austria, New Zealand, Norway, Scotland, and Switzerland. The album yielded six singles, three music videos, and a documentary film featuring behind-the-scenes footage from the production of the album. In keeping with her earlier albums, the songs explore a range of genres, including pop, R&B, hip-hop, dance, house, electro, and synthpop. The album’s genre diversity has been recognized by the critical press. For instance, Jason Birchmeier of AllMusic described Rihanna as an “R&B and dance-pop singer whose stark, sexualized hit singles established her as one of the biggest pop stars in music history” (Birchmeier 2016). Similarly, New York Times contributor Jon Caramanica declared that the album placed Rihanna “squarely at the center of the pop genre best suited for a singer of her fundamental evanescence—dance music, which conveniently is the mode du jour of contemporary R&B and pop” (Caramanica et al. 2011).

[6.2] The album’s first single, “We Found Love,” held the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100 for ten weeks when it was released in 2011. It was Rihanna’s eleventh #1 single. The song was written and produced by well-known electro house DJ Calvin Harris. AllMusic’s Andy Kellman commended the singer’s “ecstatic vocals” on the track, but criticized Harris’s “shrill, plinky production” (2016). The song lyrics juxtapose the simplicity of falling in love with the difficulties of making it last within a context of addiction, pleasure seeking, and poverty. The central chorus hook, “We found love in a hopeless place,” captures the essence of this juxtaposition. The video, directed by Melina Matsoukas, begins with a voice-over monologue delivered by UK model/actress Agyness Deyn.(14) The monologue vividly describes the desperation of the relationship in a way that the song lyrics do not. For instance, lines such as “No one will ever understand how much it hurts” and “nothing can save you” make clear that this relationship has a dark side. And, indeed, the dark side is revealed throughout the video, which features scenes of intense sexual attraction, substance abuse, nonstop partying and explosive romantic conflict, set against the backdrop of a low-income housing project. The female character is played by Rihanna while the male character is played by UK model/actor Dudley O’Shaugnessy. The volatile nature of the on-screen relationship represented in the video caused some commentators to suggest that it might reflect the off-screen relationship Rihanna had with her then-boyfriend, hip-hop artist Chris Brown (THR Staff 2011).

Figure 8. Interpretive Summary, “We Found Love”

(click to enlarge)

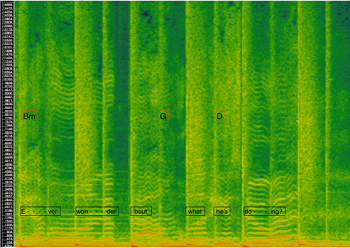

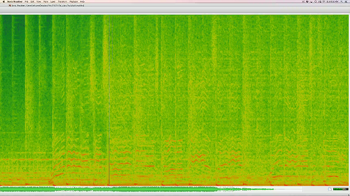

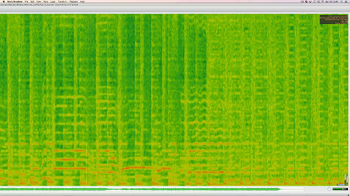

Figure 9. Rihanna, “We Found Love,” Spectrograph and Wave Images (derived from Sonic Visualiser: peak frequency layer at 7000 Hz, wave layer, spectrum layer at 9500 Hz)

(click to enlarge)

[6.3] In what follows, we present a cross-domain analysis of the video for “We Found Love” in order to show how it represents both the euphoric ups and the disastrous downs of a particularly fraught example of heterosexual relationality. Figure 8 summarizes the expressive content of the video according to the domains and parameters of the analytic model. The overall musical form of the song is illustrated in Figure 9, with spectrographic images and the amplitude wave to offer a visual representation of the sound. The reader is once again encouraged to listen to the music video track on Rihanna’s VEVO site, available here: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tg00YEETFzg).

Lyrics

[6.4] Like the lyrics for Pink’s “Try,” the thematic content of the lyrics for “We Found Love” emphasizes the paradoxical nature of love’s irresistible pleasures and inescapable pains (http://genius.com/Rihanna-we-found-love-lyrics). While the opening monologue makes this emphasis clear, the verses only hint at it (“As your shadow crosses mine”). It is, in fact, the chorus that constitutes the most direct commentary on the ambivalence and ambiguity of the liquid nature of the relationship insofar as it juxtaposes “falling in love” with “hopeless places.” Here the hopeless places refer not only to the broader social contexts in which the lovers find themselves but also to their ostensibly conflict-ridden emotional lives. Juxtapositions like these recur throughout the lyrics, where hopeful themes (“yellow diamonds,” “shine a light,” “open door”) are presented alongside doubtful themes (“I’ve gotta let it go,” “love and life I will divide”).(15) The spatial & temporal contexts are undefined and uncertain. We are informed only that the relationship unfolds in a “hopeless place”—a place that plays a prominent and ominously recurring role in the song. Temporally, the song seems to be situated in both the past and the present; that is, the monologue’s retrospective narration suggests that some time has passed since the relationship came to an end, while the verse and chorus lyrics suggest that the relationship is ongoing and that it still has the potential to last. In this regard, the lyrics are reminiscent of Bauman’s account of liquid love as a struggle between attachment and freedom, permanence and transience. The relational aspects of the lyrics indicate that the subject is both self-directed in her contemplative moments and other-directed when she adopts the first-person plural “we” to describe the shared experience of finding love. And finally, the gestural features of the monologue point to pain and vulnerability (“screaming,” “feeling hopeless”) while the rest of the lyrics point to intense moments of extreme gratification and powerful release (“come alive,” “letting go”).

Music

Example 10. Sound clip of “We Found Love,” monologue (0:20–0:31)

Example 11. Sound clip of “We Found Love,” intro and opening of verse 1 (0:48–1:14)

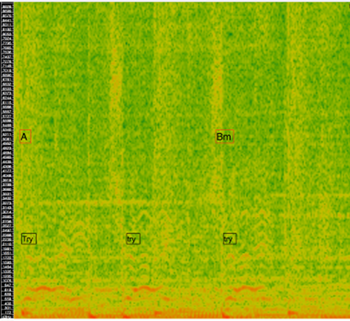

Figure 10. “We Found Love,” Verse 1, Phrases 1–2 (9000 Hz)

(click to enlarge)

Example 12. Sonic Visualiser clip (spectrograph) of “We Found Love,” verse 1, phrases 1–2 (0:59–1:06)

(click to watch video)

Figure 11. “We Found Love,” chorus hook, phrase 2 (9000 Hz)

(click to enlarge)

Example 13. Sound clip of “We Found Love,” chorus hook, transition, and breakdown (1:29–2:13)

Example 14. Sonic Visualiser clip (spectrograph) of “We Found Love,” chorus hook, falsetto (1:33–1:37)

(click to watch video)

Figure 12. Video Stills from “We Found Love”

(click to enlarge)

[6.5] The track opens with a transparent texture in which the voice-over monologue is supported by piano chords and a deep resonant bass drum that begins at 0:20 (listen to Example 10). The resonance and depth of sound is replaced by a startling crash of thunder at 0:49, which leads directly into the opening four-bar phrase of syncopated, mid-register synth stabs. As Rihanna’s voice enters for the verse, we hear an arresting contrast between the syncopated synth and her very smooth vocal line (listen to Example 11). The production of her voice is critical here: against the mechanical and stark synthesizers, a rich reverb masks her articulation so that a blurred and rounded effect characterizes all of her attacks. As her voice is also phased, the tail of her phrasing repeats in a reverberant delay. The result of these effects is that her voice is soft, airy, and warm against the grainy, edgy synth punches.

[6.6] The contrast between the rhythmic syncopation in the synth and the smoothness of her vocal line is evident in the spectrograph in Figure 10, which annotates the pulse of the

[6.7] While the vocal emerges as resonant, reverberant, layered, and smooth, the accompanying synth texture seems rather stark and empty. It delivers a number of electronic tricks that mark the electropop genre (i.e., the modulating effect in the transitions and the “four on the floor” kick drum of the dance breakdowns) but the synth backing does not have a great deal of textural depth or range (listen again to Example 10). As is evident in the upper spectrograph layer of Figure 9, the bass drop in the dance breakdown does not offer the same depth of frequency as the bass drum of the opening monologue. The effect of the backing track to Rihanna’s vocal is “thin,” which explains why Kellman referred to the synth chords as “plinky.” Analyzing these musical values in the context of our larger interpretive framework, we argue that the vibrant vocal conveys the subject’s emotional vulnerability while the cold and hollow synth texture expresses the lack of supporting depth in her intimate relations with her partner.

[6.8] Bearing the analysis of the music in mind, we can reflect on the thematic content of the song. Within the genre of electropop, the song can be connected to contemporaneous tracks such as Kesha’s “Blow” (Cannibal, 2011), Selena Gomez’s “Love You Like a Love Song” (When the Sun Goes Down, 2011), Britney Spears’s “Till The World Ends” (Femme Fatale, 2011), Maroon 5’s “Moves Like Jagger” (Hands All Over, 2011), and Christina Aguilera’s “Your Body” (Lotus, 2012). The genre of electropop features synthesizers, drum machines, and up-tempo dance beats, and is strongly associated with the dance club scene. The musical ideas and formal features are grounded in simplicity, with basic repetition that is not subjected to sophisticated thematic development. The sonic elements are favoured over the structural. In terms of spatial & temporal design, the arrangement that backs Rihanna’s voice is stark and dry, while her voice glides above with a reverberant quality. Analyzing the relational attributes, we note that while Rihanna’s voice emerges prominently in the texture, the track does not feature a wide range of dynamic intensity. As evidenced by the amplitude graph of Figure 9, we see that the overall dynamic range of the song (beginning at 00:50) is fairly consistent. The gestural parameter reveals the rhythmic tension that emerges between the vocal line and the synths, contributing to a sense of disconnection. On the whole, the song features an incongruity between the vocals and the synths, suggesting a gap that remains unfilled, and this effect is in keeping with the lyrical exploration of the “hopeless place.” What is more, the incongruity of the vocals and the synths can be seen to point to one of the most defining features of the relationship in question: namely, the co-existence of love and hate and, by extension, of romantic success and failure.

Images

[6.9] Figure 12 reproduces screenshots from the video, organized according to the parameters of the analytic model. The thematic features of the video images represent the lyrical content by juxtaposing the hopeful with the hopeless. The quality of the video image is grainy and the color palette is largely subdued, with bright effects of light and color in shots that feature drug-related activities. The drab reality of the housing project, the proximity of a building that is marked for demolition, and the abject state of their apartment point to an impoverished existence. The couple’s life in the apartment is dramatically contrasted with the bright scenes of a rave on the beach. Here the video images capture the paradoxical realities of their shared romantic lives: euphoric dancing, ecstatic sexual encounters, and ludic pleasures combined with raging arguments, dead-end thrill-seeking and poverty.(16) The story is framed by scenes in the apartment, opening with Rihanna looking out at the housing project, and closing with her leaving in anger. The activities outside the apartment suggest energy, freedom, and extreme jubilation, while the scenes inside the apartment represent the relationship’s ambivalence, conflict, and disorder. Matsoukas conveys the mind-altering effects of the drugs with a number of filmic techniques (i.e., sped-up camera motion, the spinning of the room around the subjects, and the use of light overexposure). Ultimately, drugs come to represent the relationship’s highs and lows as they metaphorize the relationship’s capacity to both intoxicate and incapacitate.

[6.10] Matsoukas manipulates our spatial & temporal sensibilities by offering a non-linear narrative and by juxtaposing and conflating the experiential disparity between inside and outside. The temporal sequence shifts from scenes in the apartment to scenes outside without a linear development of a timeline. The outside bleeds into the apartment as Rihanna is shown standing against the wall of the apartment, with the effect of external images being projected onto her body. For instance, at 3:29 (Figure 12h), the image of the demolition of a neighboring building is projected onto her body as she sings the words “hopeless place.”

[6.11] With respect to the relational parameter, the images convey the intensity of the gaze that the male and female subjects bring to bear on one another. Even when eye contact is captured by the camera, the spectator does not connect with the performers, as their gaze appears to remain within the confines of the video. Similarly, when Rihanna is filmed against the wall, singing the chorus, she does not make direct contact with the gaze of the camera, except for one scene that is worthy of special mention: in the bridge section, when the material of verse 1 returns (“yellow diamonds in the light”), Rihanna looks directly at the camera while the film that is broadcast onto her body features a blazing house on fire. Here we see a strong intertextual reference to her performance in Eminem’s video, “Love the Way You Lie” (2010), in which Rihanna stands outside of a burning home that was the scene of domestic violence.(17) Given Rihanna’s role as commentator in Eminem’s video, a role that stands outside of the story of abuse, it is important to recognize how she steps out from behind the fourth wall in “We Found Love.” In doing so, she signals her role, once again, as commentator, even though in this video she is immersed in the story.

[6.12] The gestural economy of the video is designed to contrast moments of sexual intimacy and relational conflict with moments of drug use and what we might see as a kind of emotional overdose. The juxtaposition of ecstatic and abject behaviors conveys the contradictory highs and lows of the emotional experience being represented. As their relationship suffers under the pressure of their life choices, the depictions of discontent and struggle intensify, ultimately leading to the end of the relationship (see 4:18 in Figure 12p). In “We Found Love” the subjects find themselves in a paradoxical situation: it is the thrill-seeking and risk-taking behaviors that bring them together, but it is those same behaviors that seem to tear them apart. Characteristic of liquid love, and not unlike the Pink video, the final scene remains uncertain. Though the female character is shown packing her bag in order to leave, the male partner is shown clinging to her leg, unwilling to let go. The female character eventually succeeds in leaving the room and shutting the door, but the very last shot of the video (4:25–4:29) suggests that she is still there, crying half-naked in the fetal position in the corner of the room. The final moments of the video, then, provide no linear resolution. Instead, they provide a visual account of the contradiction at the heart of their relationship: namely, that it, like the love relationships characteristic of liquid modern societies, constitutes an attachment that the video’s characters can neither abandon nor sustain.

Interpretive Summary

[6.13] The individual layers of this video (lyrics, music, images) intersect to communicate a story that is captured by the essence of the song’s hook, “We found love in a hopeless place.” Returning to Figure 8, we can examine the cross-cutting parameters to reveal how the domains of lyrics, music, and images intersect.

[6.14] The thematic parameter illuminates a lyrical struggle that is represented by a bleak visual narrative viewed in juxtaposition with the music of an up-tempo electropop track. Although that genre is typically shown to celebrate the club scene, Rihanna looks at the darker side of that story, bringing forward the destructive aspects of drug culture and unhealthy emotional dependency. We might be tempted to find an incongruity between the lyrical and visual portrayals of toxic relationships and the musical treatment of repetitive electropop. However, upon closer reflection, a repetitive design lacking in thematic development might be seen to correspond quite closely to the overall thematic statement that emerges. The spatial & temporal parameter leads us to reflect on the oppositional treatment of hope/hopelessness, inside/outside, and love/conflict, as portrayed in the lyrics and the visual images. In that regard, the use of sonic space reveals a striking disconnect between the spacious vocal treatment and the stark synth texture that might be seen as coherent with the lyrical and visual content. At the relational level, the track’s lack of dynamic energy might be interpreted in relation to the ambivalent relationship that we observe from a voyeuristic perspective. The most dynamic moment of address occurs when Rihanna connects to the spectator and delivers an intertextual message that cues us to the nature of her social commentary. The gestures portray extremes of emotion in the lyrics, which are in keeping with the extreme visual portrayal of intimacy, ecstasy, and collapse; here again, Rihanna’s gliding vocal tells one part of that story while the hollow synth gestures tell another.

Conclusions

[7.1] The model we have developed and applied in this paper provides a framework for the music analyst to consider expressive content across words, music, and images with the aim of interpreting the social and cultural meanings that arise from that content. With respect to “Try” and “We Found Love,” the meanings of interest to us pertain to human relationality and its vicissitudes in the context of heterosexual love. The model has the potential to be applied to music videos arising from other genres and to illuminate the complexities of a variety of social contexts at both the micro and macro levels. At the broadest level of interpretive concern, this approach facilitates critical reflections on the role of musical genres and styles in the representation of social and cultural contexts. This level of engagement asks spectators to question their assumptions about those contexts. The model parameters allow for a granular approach to music analysis in the domains of words, music, and images (thematic, spatial & temporal, relational, gestural) and can be drawn out individually for a detailed examination of a musical text. With these more general ideas in view, we invite the reader to explore the framework for its analytic and interpretive promise.

[7.2] As applied to the music videos analyzed here, the model sheds light on the dynamic development of words, music, and images, and more specifically facilitates the interpretation of human relationality in a context of liquid love. Our two videos pursue common thematic interests; however, the analysis reveals their many specificities. In Pink’s video, the physicality of the relationship is portrayed as equal, with aggressive behaviors emerging from both the male and female subjects. In this regard, we might understand Pink’s message to be progressive and her treatment of pop-rock discourses disruptive of normative representations of sexual relations. Rihanna’s video strains against the genre conventions of electropop by daring to show the dark side of drug culture, and by conveying an important social and cultural message about the damages done to human relationships in those circumstances. The brief but significant intertextual reference to her other work on the challenges of love tells the spectator to read “We Found Love” in the light of her role as a social critic in “Love the Way You Lie.”

[7.3] The stories being told in these videos are—without a doubt—about power, but the power in question is not one that is imposed by men upon women. It is, as we have already explained, a mobile power emblematic of what Bauman calls “liquid modernity.” In this context, according to Bauman, love too becomes liquid: it is committed and promiscuous, free and restrictive, omnipresent and elusive, owned and shared, permanent and transient. Bauman writes:

Having no permanent bonds, the denizen of our liquid modern society must tie whatever bonds they can to engage with others, using their own wits, skill and dedication. But none of these bonds are guaranteed to last. Moreover, they must be tied loosely so that they can be untied again, quickly and as effortlessly as possible, when circumstances change—as they surely will in our liquid modern society, over and over again (2003, i).

Liquid love makes paradoxical demands of the two female protagonists in our videos: it asks them to assert themselves while at the same time encouraging them to give themselves over to the other; it asks them to believe in the idea of a secure attachment even while they know that the contingencies that characterize their lives threaten to undermine the very possibility of such an attachment. As we show, this liquid love—with all of its mobile relations and perplexing paradoxes—is the love for which we must account in these two music videos by Pink and Rihanna.

Marc Lafrance

Concordia University

Department of Sociology and Anthropology

1455 DeMaisonneuve Blvd W

Montreal, QC

H3G 1M8

marclafrance@fastmail.fm

Lori Burns

University of Ottawa

School of Music

50 University

Ottawa, ON, K1N6N5

laburns@uottawa.ca

Works Cited

Adams, Cameron. 2012. “Biggest Pop Record May Be Year’s Best: Pink The Truth About Love.” The Daily Telegraph, 13 September. http://www.pressreader.com/australia/the-daily-telegraph-sydney/20120913/282359741902173.

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Routledge.

Anderson, Kyle. 2012. Review of Pink’s The Truth About Love. Entertainment Weekly, September 19. http://www.ew.com/article/2012/09/19/truth-about-love-review-pink.

Attwood, Feona. 2005. “‘Tits and Ass and Porn and Fighting’: Male Heterosexuality in Magazines for Men.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 8/1, 87–104.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Polity Press.

—————. 2003. Liquid Love. Polity Press.

Birchmeier, Jason. 2016. “Rihanna: Artist Biography.” http://www.allmusic.com/artist/rihanna-mn0000367188/biography.

Burns, Lori, Marc Lafrance, and Laura Hawley. 2008. “Embodied Subjectivities in the Lyrical and Musical Expression of PJ Harvey and Björk.” Music Theory Online 14.4. http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.4/mto.08.14.4.burns_lafrance_hawley.html.

Burns, Lori, and Marc Lafrance. 2017. “Gender, Sexuality and Technology in Beyoncé’s ‘Videophone’ (Featuring Lady Gaga).” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Popular Music and Gender, ed. Stan Hawkins, 102–16. Routledge Press.

Burns, Lori, and Jada Watson. 2013. “Spectacle and Intimacy in Live Concert Film: Lyrics, Music, Staging and Film Mediation in Pink’s Funhouse Tour (2009).” Music, Sound and the Moving Image 7/2, 103–40.

Butler, Judith. 2002. “Doubting Love.” In Take My Advice: Letters to the Next Generation From People Who Know a Thing or Two, ed. James L. Harmon, 62–66. Simon and Schuster.

Caramanica, Jon, Ben Ratliff, and Nate Chinen. 2011. “Rihanna’s ‘Talk That Talk’ Synth-Perfect for an Earlier Time.” The New York Times, November 21. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/22/arts/music/talk-that-talk-by-rihanna-music-review.html?_r=1.

Clément, Catherine. 1979. L’Opéra ou la défaite des femmes. Editions Grasset and Fasquelle.

Cooper, B. Lee. 2015. “The Hyperbolic Hit Parade: A Discographic Study of Extravagant Lyrical Assertions in Romantic Recordings.” Popular Music and Society 38/5, 611–24.

Copsey, Robert. 2012. Review of Pink’s The Truth About Love. Digital Spy, September 17. http://www.digitalspy.com/music/album-reviews/review/a406062/pink-the-truth-about-love-album-review/.

Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. 2016. Review of Pink’s The Truth About Love. AllMusic.com. http://www.allmusic.com/album/the-truth-about-love-mw0002404511.

Frith, Simon. 2004. “Towards an Aesthetic of Popular Music.” Popular Music: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies. Vol. IV: Music and Identity, ed. Simon Frith, 32–47. Routledge.

hooks, bell. 1997. Cultural Criticism and Transformation, dir. Sut Jhalley. DVD. 66 minutes. Media Education Foundation.

Ingraham, Chrys. 1999. White Weddings: Romancing Heterosexuality in Popular Culture. Routledge.

—————, ed. 2005. Thinking Straight: The Power, the Promise, and the Paradox of Heterosexuality. Routledge Press.

Jackson, Stevie. 1999. Heterosexuality in Question. Sage.

Jhally, Sut. 2007. Dreamworlds 3: Desire, Sex and Power in Music Video. Media Education Foundation. Transcript available at https://www.mediaed.org/assets/products/229/transcript_229.pdf.

Kaplan, E. Ann. 1987. Rocking Around the Clock. Methuen.

Kellman, Andy. 2016. Review of Rihanna’s “Talk That Talk.” Allmusic.com. http://www.allmusic.com/album/talk-that-talk-mw0002241043.

Madaninka, Yaasman, and Kim Bartholomew. 2014. “Themes of Lust and Love in Popular Music Lyrics from 1971 to 2011.” Sage Open, July-September, 1–8.

Montgomery, James. 2012. “Pink’s ‘Try’ Video Paints Passion, Tension and Precision.” MTV.com, October 10. http://www.mtv.com/news/1695245/pink-try-music-video/.

Moore, Allan. 2012. Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Ashgate.

Mulvey, Laura. 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16/3, 6–18.

Otnes, Celec, and Elizabeth Pleck. 2003. Cinderella Dreams: The Allure of the Lavish Wedding. University of California Press.

Rosin, Hanna. 2012. The End of Men: And the Rise of Women. Riverhead Books.

Stokes, Martin. 2010. The Republic of Love: Cultural Intimacy in Turkish Popular Music. University of Chicago Press.

Sturken, Marita, and Lisa Cartwright. 2009. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

TheNewLodge.com. 2011. “Rihanna in the New Lodge.” TheNewLodge.com, September 27. http://www.thenewlodge.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=50&Itemid=137.

THR Staff. 2011. “Rihanna’s ‘We Found Love’ Music Video References Chris Brown (Video).” The Hollywood Reporter, October 19. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/rihanna-we-found-love-chris-brown-250770.

Toynbee, Jason. 2001. “Creating Problems: Social Authorship, Copyright and the Production of Culture.” Pavis Papers in Social and Cultural Research, ed. David Hesmondhalgh. Open University Press.

Discography

Discography

Pink. 2012. The Truth About Love. RCA88725-45242-2.

Rihanna. 2011. Talk That Talk. Def Jam Recordings, SRP Records 602527878409.

Footnotes

1. Martin Stokes studies the role of love and intimacy in Turkish popular music, understanding these personal experiences as important sites of cultural expression: “Discredited by romanticism and modernism, the Western culture of sentiment either disappeared from view or was pushed to the ideological margins. But it has persisted as popular culture, where its dissonant registers of affective recognition constitute powerful, if politically ambivalent, claims about intimacy in the public sphere” (Stokes 2010, 189). B. Lee Cooper’s study of 1200 romance recordings from the late nineteenth century to the present day identifies the expressions of hyperbole in declarations of love (e.g., including words such as “always” and “forever”) and sees these expressions as “pretenses,” “dreams,” and “seductions” (Cooper 2015, 612). Cooper thus interprets the proclamations of love as hyperbolic strategies designed to attract the listener’s attention, to make bold assertions, and be persuasive, relegating these lyrics to the realm of entertainment rather than social relevance (Cooper 2015, 621).

Return to text

2. Madaninka and Bartholomew (2014) present the following findings: lyrics with love-only themes increased from the 70s to the mid-90s and then decreased dramatically; lyrics with lust-only themes increased over time, rising steadily from the mid-90s to 2011; and lyrics with combined references to lust and love decreased from the 70s to 2011. They observe that from the 70s to the 90s, themes of love without lust were most common, followed by combined themes of lust and love. Since the dawn of the postmillennium, however, lust-only themes surpassed love-only themes and combined lust/love themes. As the authors explain: “there was a notable shift from lust themes being present in the context of romantic feelings toward lust themes being presented in the absence of romance” (5).

Return to text

3. For examples of other multi-dimensional models, the reader is encouraged to consult Burns et al. 2008, Burns and Watson 2013, and Burns and Lafrance 2017.

Return to text

4. The relational parameter is particularly suitable for the analysis of the gaze because, as Sturken and Cartwright claim, “To gaze is to enter into a relational activity of looking” (2009, 94).

Return to text

5. The Truth About Love was Pink’s first #1 Billboard 200 album. It ranked as the third most successful debut in 2012, following Justin Bieber’s Believe and Madonna’s MDNA.

Return to text

6. “Try” is the only track on the album not authored by the artist. The song was written by Busbee and Ben West, and produced by Greg Kurstin.

Return to text

7. Floria Sigismondi is a Canadian filmmaker and videographer who has produced music videos for a wide range of musical genres and artists, including David Bowie, Justin Timberlake, Rise Against, Björk, The Cure, Sigur Rós, and many more.

Return to text

8. The spectrographs were derived from Sonic Visualiser using the peak frequency layer, the wave layer, and the spectrographic layer. The Sonic Visualiser program was developed at the Centre for Digital Music at Queen Mary University of London.

Return to text

9. Please note that all timecodes [0:00] listed in the paper are cued to the music video, for ease of reference.

Return to text

10. See, for instance, Moore 2012, 74–75.

Return to text

11. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CjRas1yOWvo and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GOJk0HW_hJw respectively.

Return to text

12. For an overview of the danse apache, please see http://www.jeredmorin.com/apache-dance/. The dance form circulated widely in popular culture, as exemplified in a scene from the 1935 film Charlie Chan in Paris (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-rX_SHIZaRI) as well as the infamous fighting ballet in Popeye’s 1934 episode “The Dance Contest” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f1CaEVY2SQ0).

Return to text

13. Pink would certainly know the scene from Moulin Rouge as she participated in the “Lady Marmalade” cover featured in the film.

Return to text

14. The video received a Grammy in 2012 and was also recognized at the MTV MVAs in 2012. Melina Matsoukas also produced Rihanna’s videos for “Hard,” “S&M,” “Rude Boy,” “Rockstar 101,” and “You Da One.” She has produced videos for major pop and R&B stars Beyoncé, Christina Aguilera, and Jennifer Lopez.

Return to text

15. It is important to note that “yellow diamonds” evoke a bright reflection, but might also refer to a type of ecstasy (MDMA) pill, thus offering another way to read the lyrics.

Return to text

16. The video was filmed in County Down, Northern Ireland, and in North Belfast. The area in North Belfast where the apartment scenes were shot is known as the New Lodge, a working class district with a lengthy political and socio-economic history. The website for The New Lodge lists the filming of the Rihanna video as a milestone moment (TheNewLodge.com 2011).

Return to text

17. Eminem, “Love the Way You Lie,” music video clip at [02:27] (https://youtu.be/uelHwf8o7_U?t=147).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

21450