Movement, Music, Feminism: An Analysis of Movement-Music Interactions and the Articulation of Masculinity in Tyler, the Creator’s ‘Yonkers’ Music Video

Maeve Sterbenz

KEYWORDS: Movement, embodiment, feminist analysis, hip hop

ABSTRACT: Traditionally, explicit discussion of listeners’ bodies and personal experiences does not often appear in the realm of music analytical observations. One of the reasons for this omission is the masculinist bias that, prior to the 1990s, characterized much of the field, and that tended to dismiss metaphorical language, overtly subjective musical descriptions, and the role of the body in musical practices all at once. A primary goal of feminist music theory has been to combat this bias by acknowledging many different kinds of bodily experiences as vital to music analysis. In this paper, I suggest an analytical approach that examines interactions between human movement and music in detailed terms, in service of a feminist aim to take bodies seriously. Specifically, I aim to show how music-analytical attention can be productively directed towards the performing bodies that move to music in multimedia pieces by offering a close reading of a music video by the rapper Tyler, The Creator. My analysis focuses on the relationship between Tyler’s movement and the music and on this relationship’s role in informing ways that we might read his self-positioning and identity formation. In so doing, I hope to flesh out a new feminist approach to analysis. This approach centralizes the role of moving bodies, acknowledges the subjective nature of listening experiences, and examines, primarily by way of queer theory, political potentials inherent to the movement-music interaction.

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1] When I hear music, I am very likely to move my body. Listening to a favorite piece of mine, I might draw my chest inwards slowly, sinking into a compelling bass line, or jerk my knee slightly upwards and catch my breath in anticipation of a satisfying musical arrival. I might simply mouth along to a song’s lyrics, taking pleasure in the feeling of the words. I often relate to music as if it were an environment that I can navigate with my body. The environment may present itself to me as an open landscape to freely explore, or an obstacle course to overcome. Each musical moment is a particular kind of situation that affords diverse possibilities for movement. This process of embodied navigation is, for me, one of the most powerfully affecting ways of engaging with sound.

[2] Traditionally, the field of music theory has not considered accounts of the kinds of musical experiences I have just described as integral or even relevant to music-theoretical inquiry. Perhaps because they are considered “imprecise and embarrassingly personal” (Guck 1994, 28) or “profoundly self-absorbed, and decidedly un-shareable” (Kozak 2015, [4.1]), explicit discussion of listeners’ bodies and personal experiences does not frequently appear in the realm of music analytical observations. As Marion A. Guck (1994), Suzanne G. Cusick (1994a and 1994b), and others have argued, one of the reasons for this omission is the masculinist bias that characterized much of the field prior to the 1990s, and that tended to dismiss metaphorical language, overtly subjective musical descriptions, and the role of the body in musical practices all at once. One of the primary goals of feminist music theory for the past two decades has been to combat this bias by acknowledging many different kinds of bodily experiences as vital to music analysis. In this paper, I suggest an analytical approach that examines interactions between human movement and music in detailed terms, in service of a feminist aim to take bodies seriously.

[3] Movement and music are intimately connected activities, and in works that contain both human movement and music, such as choreographed dance and music video, the two media productively interact to create emergent experiences for an observer. It is my view that this interaction warrants close analytical study. Here, I aim to show how music-analytical attention can be productively directed towards the performing bodies that move to music in multimedia pieces by offering a close reading of a music video by the rapper Tyler, The Creator. My analysis focuses on the relationship between Tyler’s movement and the music and on this relationship’s role in informing ways that we might read his self-positioning and identity formation.

[4] Music and movement both serve as media through which various kinds of identities, social relations, politics, and cultural values are articulated. Rather than transcendent, ahistorical art objects, music and the movement it inspires are inextricably linked to their cultural and historical contexts, such that the structural and formal properties of the works reflect their sociopolitical dimensions. Since the advent of New Musicology, many scholars, informed by feminist thought and critical theory, have sought to expand the definition of music analysis to include an explicit focus on these sociopolitical dimensions.(1) Similarly, I contend that sociopolitical meanings can be read into the interaction between movement and music.

[5] Any close reading of movement-music relationships hinges on the situated and embodied perspective of an observer and, as such, is necessarily subjective. Instead of dismissing movement-music analysis on this basis, I, like other feminist music theorists, acknowledge the interpretive nature of my observations, working under the assumption that enough of them might be understood, if not shared or independently reached, by readers to enrich their own engagements with the piece.

[6] The expressive potential of the moving body is vast, and watching movement that is set to music can have significant and complex effects on listening. I experience Tyler, The Creator’s performance in his “Yonkers” video not simply as a moving shape with an observable relationship to the music’s structure, but with an affective sense of the many tensions, flexions, and exertions involved in creating those shapes, as well as some of the body languages by which those movements signify. In what follows, I aim to provide a detailed account of how Tyler’s body interacts with his music. In so doing, I hope to flesh out a new feminist approach to analysis. This approach centralizes the role of moving bodies, acknowledges the subjective nature of listening experiences, and examines, primarily by way of queer theory, political potentials inherent to the movement-music interaction.

Example 1. Tyler, The Creator, “Yonkers” music video

(click to watch video)

Example 2. Tyler, The Creator, “Yonkers” lyrics

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[7] Tyler Okonma is a young California rapper better known by the stage name Tyler, The Creator, from the hip-hop collective Odd Future. He has gained much popularity since his 2011 debut album Goblin, which featured one of his most well-known tracks, “Yonkers.” Tyler’s rap in “Yonkers” is loosely structured as a dialogue between himself and a therapist, and his verses tend to take the form of thoughts and reflections on various topics. The video, on the other hand, is presented as a single shot that presents a linear series of events, which might lead the viewer to ascribe some narrative significance to developments in the music. The complete video can be found in Example 1, and the video’s lyrics can be found in Example 2.(2) The majority of the video consists simply of Tyler sitting on a stool rapping to the viewer, but this is interrupted periodically by progressively more intense dramatic developments, which seem largely unrelated to the content of his lyrics. On a large scale, overall changes in his bodily attitude as well as developments in the video’s plot help to demarcate the large formal sections, or, on a few occasions, to obscure their boundaries in interesting ways. On a small scale, minute details of synchronization and body language contribute to an impression of Tyler as alternately awkward, lame, anxious, aggressive, and defeated. His movements elicit nuanced hearings of his vocal flow and aspects of the song’s form.

[8] At first glance, the relationship between movement and music in this video might not seem to warrant analytical attention. Tyler never dances per se, nor does he even entrain his body to sound in the usual ways (e.g. bobbing along, swaying, snapping, tapping, etc.). The possibilities for movement-music analysis appear to be limited in a context where body movements seem to function more as action in a solo narrative than as a response to musical cues. His movements often look awkward, ineffectual, or strange in relation to the accompanying music. Sometimes the relationship between movement and music seems to be contradictory or indifferent. Actually, however, Tyler’s movements provoke a rich and nuanced hearing of the piece for me, and it is precisely in these apparent failures to synchronize his movements to the music in an obvious way and to convey the cool confidence that his lyrics purport that I locate the video’s peculiar and potent political possibilities. In the “Yonkers” video, Tyler fails to present himself as archetypically hetero-masculine, fails to confront the viewer, fails to achieve self-actualization, and ultimately, by the end of the video, he fails to live. It is in these moments of failure that he charts artistic and political alternatives to the status quo. Before exploring the notion of failure in more depth, let us examine the opening bars of the music video.

Figure 1. Tyler, The Creator, “Yonkers” intro silhouette

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. “I’m a fuckin’ walkin’ paradox, no I’m not”

(click to watch video)

[9] The opening of the video is sparse, both musically and visually. We hear a simple, common hip-hop drumbeat, a screechy synthesizer giving approximately

[10] Though he sits perfectly still, we can already observe a productive music-movement relationship. If we interpret Tyler’s dark stillness as a failure—that is, failure to engage with the sound, failure to entertain, failure to be fully seen—we become aware that the sense of the opening sound as sparse is in fact created, or at least emphasized, by the lack of movement. The angular posture, the prolonged stillness, and the ominously obscure figure draw attention to the tinny, harsh timbres. Imagine instead that the lights were already on Tyler’s face, and he was moving and mouthing along to the pitch-shifted interjections. Or alternatively, imagine that he was bobbing energetically to the beat. Such modifications would redirect the focus away from the thinned-out, severe nature of the musical accompaniment and towards the rich low-register vocals or the commonplace rhythmic structure.

[11] Four measures in, the bass enters powerfully. Simultaneously the lights come on and Tyler’s body suddenly activates. He straightens up, turning to face the camera, and his body language is open, direct, and almost confrontational (see Example 3). This turns out to be an important moment: brief as it is, it is the only moment in the entire video that he is fully successful at confidently confronting the viewer. The hand on which he had previously rested his chin bursts open abruptly on the downbeat, lending some fanfare to the opening bass note. As he delivers the first line, “I’m a fuckin’ walkin’ paradox,” his movement imbues the music with a sense of confidence, as if being a “fuckin’ paradox” gave him a kind of untouchable mysteriousness or glamorous exceptionalism. Almost immediately, however, this jig is up, as Tyler admits, “no I’m not,” quickly turning his gaze away from the camera, lowering his chin, and shrinking back into his shoulders. Beyond a clever joke on the notion of paradox, this line initiates the self-defeating, loser ethos that runs through the video. The opening bass note, which initially brought the promise of confident strength, sinks a half step just as Tyler corrects himself, “no I’m not,” as if musically sounding out the sense of letdown brought about by the realization.

[12] Already we can see text, music, and movement interacting to form a complex picture of a conflicted black masculinity. Within the first measure of rapping, Tyler flips manically from aggressive self-inflation to self-deprecating defeat. This turns out to be just the beginning of a series of productive failures that take place within the movement-music relationship. While these failures contribute to pervasive feelings of loss, awkwardness, emasculation, humiliation, and apathy, they also serve as openings for the subversive and playful. Here, we can bolster our understanding of this subversiveness with recourse to queer theory.

[13] Jack Halberstam suggests that failure can be a queer political attitude, which enables radical alternatives to normative ways of being and patterns of thought.(3) For Halberstam, when one fails to succeed under the models of success defined by the dominant culture, one creates the potential to inhabit the world differently:

Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world. (Halberstam 2011, 2)

Halberstam identifies many different ways of creatively failing, including losing, forgetting, and stagnating, as well as exercising stupidity, negativity, and immaturity. For the purposes of the present analysis, a few specific types of failure that are especially appropriate lenses for the “Yonkers” video are worth special mention. I group them into two broad categories: (1) light-hearted failures, including overt stupidity, silliness, and illegibility, and (2) bleak failures, including abjection, anti-futurism, and self-annihilation. Stupidity and silliness present opportunities to confuse privileged relationships. The queer political dimension of stupidity lies in its irreverence to the forms of knowledge production that establish such relationships. In some contexts, stupidity and silliness result in a kind of nonsense whose queerness takes the form of illegibility. Halberstam implores readers to “resist mastery” and “privilege the naïve or nonsensical” (Halberstam 2011, 11–12).

[14] On the other hand, queer failure can take on a darker meaning as the loser’s nihilistic or abject view from the bottom. This view “lays claim to rather than rejects concepts like emptiness, futility, limitation, ineffectiveness, sterility, unproductiveness” (Halberstam 2011, 110). Halberstam identifies queer political potential in an anti-futurist negativity that does not invest in the heterosexist optimism of the continued family line, but rather invests in “antireproductive logics” and in abjection (108). In an even darker turn, Halberstam explores the self-annihilating negativity of what he calls “radical passivity.” He also locates passive and nihilistic failure in feminist theory and art. Halberstam outlines a “shadow feminism,” which “speaks in the language of self-destruction, masochism, [and] an antisocial feminitity” (124). From this perspective, acts of passivity and self-annihilation become political acts that “[refuse] purpose” (132), “[surrender] to a form of unbeing” (131), and seek to dismantle the feminine subject. As an example of radical passivity, he cites Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece,” wherein she provides the audience with scissors and allows them to cut off bits of her clothing. The performance positions Ono as a radically submissive anti-master, and aligns her work with a feminist genealogy that invests in “antisocial” and “anti-authorial” modes (140). For Halberstam, passivity and self-annihilation take on political significance as a queer or feminist response to the liberal politics of futurity, action, and progressiveness.

[15] Failure, as an analytical framework, can illuminate some of the more radical aspects of the “Yonkers” video. While not precluding critique (after all, Tyler proves successful in the normative sense in a number of arenas, and his work is not without misogynistic and homophobic messages), this reading highlights some aspects of Tyler’s public image that possess a surprising potential for feminist and queer politics. In particular, my focus here is on the ways in which the movement-music relationship contributes to his creative failings, both silly and abject. As such, I isolate two types of movement failures: the failure to effectively synchronize, and the failure to convey through body language the machismo that is sometimes suggested by his lyrics.

[16] At times, reading failure into a movement-music relationship might seem like an arbitrary decision, and in many cases, it is. The point is not so much to make a case for failure as the only reasonable reading of the piece, but rather, using a purposefully limited definition of failure, to apply the concept as an analytical lens in order to see what falls out. Not unlike a music-theoretical tool such as Schenkerian or set-theoretical analysis, we could say that, while the piece might lend itself especially well to this lens, it is ultimately an analytical decision to run the piece through a flexible failure “sieve,” in order to arrive at a more detailed interpretation of it.(4)

[17] It might seem odd to provide a queer or feminist reading of a video that, in many ways, resists such a reading. Tyler, The Creator has received criticism for the often misogynistic and homophobic content of his lyrics, including his frequent use of the word “faggot,” in this song and others (Eate 2013). Some of his failures at conventionality in the “Yonkers” video might arguably be interpreted as part of a hyper-masculine display, or as mere shock value, rather than as radical or queer. Indeed, I maintain that Tyler’s works and public image simultaneously contain elements of both dominant masculinity (predicated on the subjugation of others) and a radical queer rejection of this archetype. By doing a queer reading, my aim is not to speculate about Tyler’s sexuality, but to read a political potential into the music video—a potential that is not a fixed property of the work, but that exists in the interpretive space between work, context, and viewer.

Figure 2. Four photographs from Tyler, The Creator’ Instagram account, including a Cherry Bomb album cover (top left)

(click to enlarge)

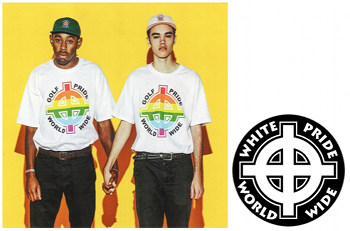

Figure 3. A photograph from Tyler, The Creator’s Instagram account (left), and the “White Pride” symbol (right)

(click to enlarge)

[18] The political dimensions of the video become more apparent when considered alongside his image as a celebrity figure. Instagram has provided one of the platforms through which Tyler curates his public image. His Instagram account often features revolting, stupid, or nonsense images, as well as images of failure, usually presented with little or no context (see Figure 2).

[19] For instance, in his April 15, 2015 post, which promoted the release of his album Cherry Bomb, he displayed one of the record’s album covers, featuring the pissed-in jeans, limp hands, and unlit cigarette of an anonymous person. This album cover, like many of his other Instagram posts, conveys a kind of humorous apathy in regard to more conventional macho or cool posturing. The pathetic humiliation normally associated with pants-pissing, in tandem with the lame body language of the limp hands, too defeated to even light a cigarette, takes much of the sense of ego out of the image. In fact, macho or cool posturing do not feature in any of the five Cherry Bomb album covers, which range from silly to lame to slightly disturbing.

[20] A queer analytical framework might seem more apropos when these silly, even gross images are considered alongside some of Tyler’s more overtly political public statements. In another Instagram picture posted a few weeks after the album cover, he advertised a T-shirt he was selling as part of his Odd Future clothing line (see Figure 3), and in the caption, directed fans to a brief article he had written about the shirt.(5) The shirt features a re-appropriated White Pride symbol in rainbow colors, a widely-known symbol of gay pride, and reading “Golf Pride World Wide.”

[21] In the picture, Tyler and another man wear the shirt while holding hands. The two men seem to convey not so much a defiant statement of pride in the face of adversity as a somewhat meek, apathetic stance. Beyond same-sex handholding alone, the image comes across as queer in its normcore dorkiness; rather than a liberal rhetoric of triumphant overcoming, the image displays a couple of meek-looking losers taking the mick out of an offensive symbol. In the article Tyler published in his online magazine, Golf Media, he wrote about the thought process by which he arrived at the shirt’s design:

Now it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to know that these guys aren’t fans of Blacks, Gays, Asians or anything else that doesn’t fit in the “white” box. Now having the thought process that i have, i asked myself some questions: What if a black guy wore this logo on a shirt? Would he be promoting self hate? Would he be taking the power out of a shape? What if a gay guy wore this on a shirt? Would he promoting Homophobia? Then BAM! I Had it. Throw a little rainbow in the logo. . . and take a photo with a white guy in it and we have an amazing photo. The thing that tops it off is the homo erotic tone of the hand holding, which to some degree HAS to piss off the guys who takes this logo serious. This made the photo even more important to me, because it was me playing with the idea of taking the power out of something so stupid. (Okonma 2015) [sic.]

He goes on to address the homophobic reputation he acquired throughout his career for frequently using the word “faggot,” arguing that his use of the word is a similar attempt to “take the power out of something.” Both the shirt’s design and its homoerotic advertising reflect not only a rejection of homophobia and racism, but also of positivity and progressive politics. In fact, in an ego-diffusing move, Tyler does not even stand firmly behind his own experiment: “Or maybe my whole idea on this is stupid. Who knows, but why not try it out?” (Okonma 2015). Duri Long argues that Tyler, The Creator’s music and public image reflect not simply apathy but an openly nihilistic attitude, wherein he regularly invests in nihilistic themes including the rejection of higher values, the devaluation of life and property, and a loss of hope (Long 2014). Through a Halberstamian lens, this nihilism might take on radically queer meanings.

[22] Still, in many ways Tyler invests in prevailing and often violent modes of masculinity. At times, his lyrics also explicitly invoke misogynistic anger. Penelope Eate has argued that narratives of rape and misogynistic violence in Tyler, The Creator’s music function as therapeutic performances through which he can allay anxiety related to the pressure of appearing conventionally masculine (Eate 2013). In Eate’s study of Tyler’s works as of 2013, she observes that his lyrics often consist of “lurid rape fantasies which detail the stalking, abduction, murder and sexual violation of women” (2013, 530). She categorizes these fantasies into three types:

Such scenarios, within the narrative conceptualization of Tyler, The Creator’s recorded material, are presented as a form of punishment for rejecting romantic advances (‘Sarah’, ‘She’), as a furtherance of more benign anti-social behaviour (‘Ass Milk’, ‘Tron Cat’) or as a strategy to knowingly play into and commodify culturally embedded fears of the Black man as ‘brute’ (‘VCR’, ‘Transylvania’). (Eate 2013, 530)

Still, Eate acknowledges Tyler’s frequent and “surprisingly transparent” admissions of his own masculine failings and feelings of self-loathing, which position these fantasies as opportunities “to work through feelings of disempowerment or as a way to construct a specifically deviant masculine subjectivity in opposition to established patriarchal norms” (2013, 543). While Eate does not excuse the misogynistic content of these fantasies, she positions them as reactions to, and acknowledgements of, various emasculating humiliations that pervade black male experience. She suggests that “rather than the cultural expression of one who comfortably occupies a place of privilege,” the fantasies participate in Tyler’s construction of a peculiar version of black masculinity in the face of a “failure to satisfy social constructed ideals of Black manhood” (543). Thus, the even most misogynistic and aggressive dimensions of Tyler’s masculine identity point to the failure that is its queer flipside. In some ways, Tyler’s public persona as a loser participates in the articulation of a misogynistic and homophobic status quo, but at the same time, certain aspects are surprisingly subversive, and those are the aspects I intend to explore here. With this in mind, let us now turn back to the music video.

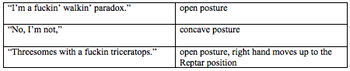

[23] Overall, it is rare that Tyler employs speech-independent gestures or referent-related gestures. That is, rarely do his gestures help clarify or modify the semantic meaning of his words. In the second line of the rap, however, he uses his hand to form the number three just after he delivers the word “threesomes,” and then a second later he folds his hand to resemble a dinosaur head around the time he says “triceratops” and “Reptar,” the dinosaur toy from the cartoon Rugrats (see Example 3). While these offer some successfully communicative body language, they fail to synchronize either to the vocal delivery or the accompanying music in an obvious way. His hand moves in a controlled way, subtly changing directions at very precise moments, yet for the most part, this precision is awkwardly out of sync with any obvious musical cues, including basic aspects such as the pulse. In fact, I find the exact timing of these movements rather difficult to replicate in my own body. The movements lie somewhere in between everyday movements that would lend the rapping a conversational quality and more dance-like movements that might ordinarily befit a music video. The only seemingly musically motivated movements are the shift of the gaze into the camera just when the phrase begins, and the emphasis on the word “fuckin’” as the three-finger gesture quickly gives way to a subtle flash of his whole hand.

Table 1. Vocal flow and movement groupings

(click to enlarge)

[24] On a slightly large scale, units of movement correspond loosely to musical groupings created by Tyler’s flow. The assonance of “-dox,” “-not,” and “-tops” creates a long–short–long grouping of the vocal phrase, and the grouping is loosely replicated in the larger movement changes (see Table 1). This vowel sound returns in the words “mockin’” and “rock,” but this time it occurs on the beat, rather than off the beat as it did in the three previous instances. While the rhythm of the vocal delivery is rather square and repetitive—every syllable lasts either an eighth or a sixteenth note—the irregular placement of these internal rhymes creates an unpredictable and dynamic flow. The movement that initially draws attention to this grouping structure helps to highlight this complexity.

[25] Tyler’s movement also obscures other possible groupings that are more regular and predictable, such as the one created by the emphatic repetition of the word “fuckin’” followed by the word “mockin’,” which all fall on beat three of the first three measures. Some of his movements are simultaneous with this repetition: he looks up in the first measure, and then opens his hand from three fingers to five in the second measure. But the hand movement is rather subtle as compared to the larger movement changes that emphasized the other grouping, and the word “mockin’” is not really emphasized in his movements at all. The synchronization of his movements highlights these competing groupings, while also rendering the more irregular, subtle one the stronger of the two. Similarly, the relative lack of movement change throughout the Reptar-hand section obscures the would-be obvious aural parallel between “Reptar” and “rock stars.” The next section of the verse is demarcated by the sudden presence of a cockroach on Tyler’s hand, and this change emphasizes the start of a new measure. Imagine instead that the introduction of the cockroach occurred a beat earlier, so that it coincided with “rock stars.” Such an alteration could suggest a different way of grouping the vocal flow, where “rock start” was overtly related to “Reptar” as the beginning of a group. The synchronization of Tyler’s movement flits rapidly between the metrical structure and different grouping structures in the vocal flow, as well as to nothing in particular. He never maintains a consistent pattern long enough for the viewer to entrain to it, and the result appears somewhat graceless and feverish.

[26] Although the lyrics in the first three lines are arguably quite boastful, these strangely timed body movements convey a kind of ineffective awkwardness. His gaze momentarily returns to the viewer at “threesomes,” and his hand gestures in these opening lines engage the viewer by way of serving a loosely communicative function, but he quickly averts his gaze, and the largely asynchronous nature of his arm movements make the gesticulations feel absent-minded. Compounding this feeling is the disconnect between hand and gaze. While the ostensible reason for looking away from the viewer is to follow the path of his hand, his gaze actually looks up at nothing initially, and his hand eventually arrives in the vacant spot. While his gaze and hand finally click into place at the word “rappin’,” he almost immediately loses focus on his hand, which absent-mindedly carries on with the Reptar gesture. The Reptar hand opens and closes its “mouth” in a rhythm that continues to be irregular and awkward-looking, but which is actually almost completely synchronized with the alliterative “r-” sounds in the rap. The movement is subtle, and the sense of synchronization is loose. The combination lends this alliteration a kind of stuttering, rather than deliberate, quality.

[27] One of the effects of all this movement-music awkwardness is that Tyler fails at the kind of strong movements or musical coordination that would convey the cool confidence his lyrics suggest. The relationship between music and movement, even in this very brief opening, prevents him from appearing fully convincing in his boastful claims. If confidence and posturing are a requisite part of archetypical masculinity, especially within the hip-hop genre, Tyler’s movements fail to realize this archetype.

[28] Shortly after the start of the rap when his left hand disappeared from the frame, it reappears holding a cockroach, without any interruption to the flow of his movement. The introduction of the cockroach is smooth and, in a different sort of failure at conventionality, his body language remains unperturbed as if the bug were relatively unremarkable. Though this is one of the more eventful moments in the video’s plot, it does not mark any significant musical change. It occurs three measures into the first verse before any change in vocal flow or instrumentation has occurred. Still, the appearance of the cockroach coincides with the descent by a semitone of the bass line, which, like its first occurrence at “no I’m not,” lends this melodic gesture a somewhat sinister effect. Tyler plays with the cockroach ominously during a verse wherein his movement remains highly controlled, but largely monotonous and out of sync with obvious musical cues. For the next three measures, he carefully follows the cockroach with his eyes and hands, and the stoic, uninterrupted motion lends a sense of continuity to his vocal flow.

[29] Compared to the gesture-filled and fidgety opening, the appearance of the cockroach downplays some of the divisions that might have been created by the rhyming structure. The changing metrical position and rearrangement of soft rhyming syllables, such as “deaf rock stars,” “wars dread locks,” “bed rock har-,“ and “crack rock,” in tandem with the steady, controlled movement, gives the impression of a kind of monotonously delivered tongue-twister. There is also a square rhyming structure created by the placement of “Flintstone” and “fish bones” on the fourth beat of two consecutive measures, but again this regularity is obscured by Tyler’s movements in favor of a more fluid feeling. The verse is divided into two smaller sections (eight measures and four measures) by a noticeable change in his the style of his flow starting with “Swallow the cinnamon. I’m’a scribble this sinnin’ shit

[30] Suddenly, he bites down on the cockroach in an abrupt gesture that on a large scale roughly coincides with a move to a new musical section (the instrumental hook) and the return of the screechy synthesizer. But there is not a whole lot of fanfare to this move, despite its shock value. Rather than emphatically mirror the intensity of the synth timbre, he puts the bug in his mouth with perfunctory effort just after the big musical change. He hardly moves or alters his body language. This music-movement relationship gives the impression that Tyler does not triumphantly conquer the cockroach in a masculine display. Rather, he appears to force it on himself masochistically. Sure enough, he humiliatingly vomits it back up, and eventually returns to his stool, apparently defeated, to deliver the next verse.

[31] The vomiting section serves as an interesting case in point for the observation that synchronization between sound and music can have important effects on the perception of both. In particular, the perception of Tyler’s vomiting as an extemporaneous response to eating the cockroach is greatly helped by the fact that the retches and heaves and so forth, while constituting some of the largest and most emphatic body movements we have seen so far, do not have any special relationship to the music. Imagine instead a very slightly different timing wherein the heaves were synchronized with perceptually strong moments in the metrical structure. Despite the universally understood body language of vomiting, this section would look much more like part of the performance than an involuntary break from it. By comparison, notice the slightly different effect created by the body movements over which Tyler has more control, namely the two wrist flicks just after he wipes his mouth. These fall on the beat, and the first one marks a downbeat. While he still has not yet returned to full “performance” mode, these hand flicks have a subtly stronger relationship to the music than the involuntary vomiting movements.

[32] Nonetheless, the body language of the vomiting gestures has a musical effect. The hunched-over, seizing body lends some tension and urgency to the screeching synthesizer that dominates this section musically. The line between musically motivated versus “nonartistic” or “everyday” body movement is blurry here, and throughout the video. In many cases, it is simply the presence of music and synchronizations with the music that give otherwise unremarkable body movements a deliberate or dance-like quality. Similarly, movements that look more deliberate than ordinary movements, but whose musical motivations and synchronizations are obscure, give the impression of awkwardness or strangeness.

[33] In the absence of the music video, this screechy-synthesizer section seems to serve a relatively conventional formal function as an instrumental hook between verses. The cockroach-vomiting scene that accompanies this section, however, gives the impression that the hook section is unintentionally blank. That is, it appears as if Tyler must momentarily break from his performance because he could not manage to keep the bug down. He fills the instrumental section with apparently extemporaneous action in the music video’s narrative that accounts for the empty space, which might otherwise have posed a problem to the video’s real-time format.

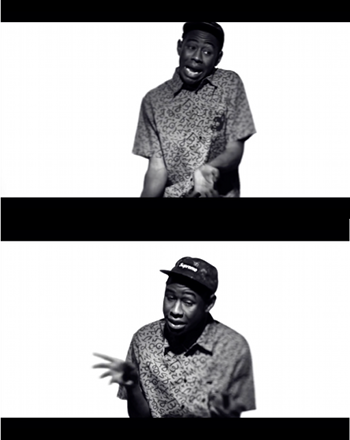

Figure 4. “Sheesh I already got mine” (top), and “Wasting my damn time” (bottom) from “Yonkers”

(click to enlarge)

[34] Just as Tyler returns to the stool, the next verse begins. In much of the next verse, he resumes the kind of sheepish body language and fidgety gestures that characterized the first verse. And again, this kind of movement is subtly at odds with his relatively aggressive and boastful lyrics. Though his body appears to be relaxed overall, there are a few brief moments when he tenses up awkwardly (see Figure 4). These moments of tension occur at random intervals that do not allow the viewer to latch onto any particular pattern, and as such, they give the impression of being genuine, involuntary emotional reactions to the content of his lyrics.

[35] Like the first verse, the second verse is split into a group of twelve measures and a group of four. In the last four measures of the verse, the instrumental track thins out somewhat, but the screechy synthesizer from the vomiting scene returns. Whereas the violence of eating and vomiting the cockroach emphasized the severity of the synthesizer’s timbre, in this section, Tyler’s gentle and inward-focused body language does a lot to soften the grating effect of the synthesizer. Tyler also momentarily explicitly addresses masculinity and sexuality in this section. He raps “I slipped myself some pink Xanies / and danced around the house in allover print panties / my mom’s gone that fuckin’ broad will never understand me / I’m not gay, I just wanna boogie to some Marvin.” Again, his movement here is somewhat fidgety, and lacks any emphatic synchronization to the vocal delivery or the instrumental track. His body language is closed off, introverted and sheepish. As he unbuttons his shirt, he seems to indulge in the vulnerability of nakedness. Imagine instead confident body language and sharp synchrony with the music. He would be rather more convincing in his hetero-masculine assertions. Instead, however, in a rhetorical move that simultaneously conveys humorous self-awareness and self-deprecating despondency, the movement that actually occurs emphasizes the effeminate and queer aspects of his persona.

Example 4. “Fuck her” from “Yonkers”

(click to watch video)

[36] The imaginary therapist (one of Tyler’s alter egos) with whom he is in dialogue throughout the song then asks, “What you think of Hayley Williams?” The question distracts him from the task of unbuttoning his shirt and triggers a sudden shift from the sheepishness and relatively loose relationship between movement and music that characterized the previous verses to hyper-aggression and a sharp, synchronous correlation between movement and sound. Tyler leans forward abruptly and emphatically as he says the word “fuck” (see Example 4), emphasizing beat 2 and mirroring the sharpness of the simultaneous snare attack, then sits back up and articulates the next eighth-note beat just as emphatically with a small bounce in his chair.

[37] He performs two similar, but progressively weaker, movements on beats 3 and 4. In the next measure, his hand swoops up on beat 1 in a gesture that possesses anacrustic potential energy towards the “airplane” hand shape that is achieved sharply on the snare hit on beat 2 (see Example 2). Tyler’s movement thus articulates a metrical displacement where beat 2 serves a downbeat-like function by virtue of being an emphatic point of arrival. On beat 3 his hand falls down past his face in a relatively fluid and unemphasized movement, and lands sharply in a fixed shape on beat 4, continuing the pattern of strong emphasis on weak beats (see Example 2). His movements draw attention to aspects of his vocal flow and to the force of the snare timbre, while creating tension with the underlying metrical structure. Thus, even in this singular moment of overt aggression and synchronization, Tyler’s movements remain, in at least one dimension, awkward and tense. At the end of the verse he apparently remembers his milder, passive self as he finally completes the act of taking off his shirt, though now with impatient, distracted quickness. Especially given the lack of eye contact, his movements seem to express more a sense of internal conflict than a confrontational attitude.

[38] In the narrative arc of the video, this emotional outburst seems, perhaps primarily in retrospect, to serve as a climactic episode from which Tyler never fully recovers. While the outburst is positioned as a kind of interruption, and he appears to calm down and resume delivering more reasoned, articulate thoughts, his blackened-over eyes betray the fact that something crucial has changed. For the first time he looks straight at the viewer for an extended period of time, but he is protected, by the effect on his eyes, from making true eye contact. Chest fully exposed now, he passively returns to his milder delivery style. The drastic change in movement creates a much more significant boundary between parts 1 and 2 of the third verse—i.e., between the first four aggressive measures and the last eight meekish measures—than between the second verse and the third verse. Movement plays a significant role in my perception of the song’s form. The anticlimactic return to sheepish body language and awkward synchronization give the impression of emasculating defeat.

Figure 5. “Yonkers” ending

(click to enlarge)

[39] In a shocking final failure, Tyler gives up entirely and commits suicide. As we see his body dangle ominously, his legs kick frantically before going still (see Figure 5). Though the movement is ostensibly an extemporaneous response to the situation and not musical, the wild jerking is reminiscent of the fidgeting awkward movement that characterized earlier parts of the video, and lends a frenetic quality to the screechy synthesizer. This movement is also reminiscent of the vomiting section, and thus highlights the repetitive nature of the song’s large-scale form. And of course, none of the movement in the video is extemporaneous, natural, or unfiltered. Tyler’s movement, unpolished as it appears, is performed and deliberate. Failure here is not a loss of control, but a controlled move away from what is expected, conventional, useful, positive, appropriate, or productive.(6)

[40] In the final moments of the video, Tyler mimes an ultimate self-destruction that is the endpoint of a trajectory initiated by the self-effacing and thoroughly negative attitude demonstrated even within the first few seconds of the video. In the face of racist and sexist systems of oppression that often demand brutishness and arrogance of black masculinity, Tyler chooses annihilation, futility, and passivity. In a refusal of respectability politics, progressivism, and looking on the bright side, he fails. Beyond lyrics or visuals alone, the relationship between movement and music plays a crucial role in the way Tyler articulates this politically queer narrative.

[41] Like feminist theory more broadly, feminist music theory cannot be singularly expressed as a monolithic perspective. The influences of feminist thought on music theory have resulted in a number of different approaches to music study, many of which reach across disciplines. The foregoing study is enabled by several of these approaches, and diverse but interrelated strands of feminist music theory converge in my analysis. In closing, I would like to acknowledge three in particular that emerge as especially important: (1) an explicit focus on embodiment, (2) an intersubjectivist approach to analysis that acknowledges the epistemological limitations on any situated individual, and (3) critical theory as a lens for understanding sociopolitical dimensions of artworks.

[42] Of the many feminist interventions in music theory research since the 1990s, perhaps one of the most wide-reaching has been the acknowledgment of the crucial and inextricable link between music’s audible dimension and the body. In her essay “Feminist Theory, Music Theory, and the Mind/Body Problem,” Cusick critiqued traditional music theory for denying embodiment with a view of music listening as a “mind-mind” exchange, wherein music analysts “describe practices of the mind (the composer’s choices) for the sake of informing practices of other minds (who will assign meaning to the resulting sounds)” (1994b, 16). Like Cusick, Cook (2013), Cox (2011), Fisher and Lochhead (2002), and LeGuin (2005) have stressed the importance of the embodied knowledge that arises from music performance, arguing that such knowledge can significantly enrich analytical practice. Others scholars, like Mead (1999), Bowman (2004) and Kozak (2015), have emphasized the inherently embodied nature of listening as a crucial dimension of musical experience. According to Bowman, a given musical situation affords a range of possible ways of moving to it or “orient[ing] the body” to it, and this embodied resonance is at the core of all musical activity (2004, 42).

[43] Kozak acknowledges the difficulty that subjectivity poses to the project of taking listeners’ bodies seriously. Each listener’s body is unique, and differences in training, ability, and stature ensure that no single listener’s embodied experiences can be universalized. Kozak’s study, therefore, informed by research in embodied cognition, uses motion-capture technology that collects movement acceleration data from a range of listeners, drawing conclusions about listening experiences based on the ways in which many different listeners move to music. For Kozak, motion-capture tools and data analysis provide a “methodologically robust” solution to the threat of solipsistic subjectivity (2015, [5.1]).

[44] Another strand of feminist music theory has provided a different, and equally robust, means of addressing this threat, however. The listener’s physical body is but one of many factors which render any given listener a situated, rather than objective or impartial, observer, and feminist music theorists have long acknowledged the personal and subjective nature of musical experiences. Guck, in her article “Analysis as Interpretation: Interaction, Intentionality, Invention,” outlines an analytical approach that focuses on the particular experiences that music affords individuals:

Because music is designed to be used by people and to effect change in us, I look for analysis of the human-music interaction that articulates what the music does to or for us—for instance, that it confuses, astonishes, or moves us—and how it does so. (2006, 206–7)

Guck proposes that analysis should reflect a “meeting between an individual and some music” (194), and she contends that, while all music-analytical claims are interpretive on some level, they can still be intersubjectively shared. Rejecting the perspective that holds that the validation of music-analytical claims rests on their objectivity, Guck shows how divergent analytical approaches can yield equally informative analytical results, even when those approaches appear to be based in personal, impressionistic, or metaphorical observations, rather than impartial or formalist ones. Following Guck and others,(7) my analytical approach emerges from the perspective that experiences can be intersubjectively shared with readers. The analytical process becomes one of “directing the reader’s attention towards a way of hearing the music in question” (Guck 2006, 201).

[45] The study of dance or movement and music has primarily been approached from ethnographic or historical perspectives, where the analytical focus tends to revolve around questions of how the music and movement are put together by choreographers and composers, or how one art form shapes the production or reception of the other. Perhaps because of the central role of bodies, music theory has not often addressed dance or movement. Foregoing developments in the field of music theory informed by feminist thought have enabled me to develop a hybrid methodology by which I can combine movement analysis, music analysis, and critical theory in a close reading of a single work.

[46] My analytical observations depend upon my embodied knowledge, which lends me a sense of what it might feel like to move as Tyler moves. The foregoing analysis involved an intensive kind of labor, which is familiar to any music theorist who has listened to a passage over and over again, or painstakingly pored over a score, but which, in its differences from traditional modes of analysis, points to the many and fruitful avenues that feminist thought can open up for music theory. I moved through Tyler’s gestures precisely and repetitively, and as a result, focused acutely on the sensations that they engendered. Ultimately, my engagement with the music was much the better for it. In directing my analytical attention towards movement-music relationships, I discovered new and rich analytical resources, and ultimately engaged with the music more closely than I otherwise might have.

[47] Admitting the body into music-theoretical inquiry should be motivated not only by the political stance that hopes to avoid the oppressive side effects of the “mind-mind” exchange model, but also by the diversity and richness of music-analytical observation that it provokes. In recent years, many music studies have emerged that foreground the role of the body in music practice, listening, and analysis. While not all of these studies espouse explicitly feminist aims, arguably, the topic’s current popularity within the field was enabled by interventions of feminist theory in music theory. While the political aims of feminist music theory should not be overlooked or diluted, it should equally be acknowledged that feminist approaches to music analysis, such as those that foreground embodiment, are valuable not only for the ways in which they resist marginalizing intellectual practices, but also, crucially, for the ways in which they improve and expand upon our understandings of music and musical experience. Simply put, feminist music theory can make for better music theory.

Maeve Sterbenz

Columbia University

Department of Music

MC 1813, 2960 Broadway

New York, NY 10027

mas2219@columbia.edu

Works Cited

Bowman, Wayne. 2004. “Cognition and the Body: Perspectives from Music Education.” In Knowing Bodies, Moving Minds: Towards Embodied Teaching and Learning, edited by Liora Bresler, 29–50. Springer.

Callahan, Daniel. 2012. “The Dancer from the Music: Choreomusicalities in Twentieth-century American Modern Dance.” PhD diss., Columbia University.

Cook, Nicholas. 2013. Beyond the Score: Music as Performance. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2001. “Theorizing Musical Meaning.” Music Theory Spectrum 23 (2): 170–95.

Cox, Arnie. 2011. “ Embodying Music: Principles of the Mimetic Hypothesis.” Music Theory Online 17.2.

Cumming, Naomi. 2000. The Sonic Self: Musical Subjectivity and Signification. Indiana University Press.

Cusick, Suzanne G. 1994a. “On a Lesbian Relationship with Music: A Serious Effort Not to Think Straight.” In Queering the Pitch: The New Gay and Lesbian Musicology, edited by Philip Brett, Elizabeth Wood, and Gary C. Thomas, 67–83. Routledge.

Cusick, Suzanne G. 1994b. “Feminist Theory, Music Theory, and the Mind/Body Problem.” Perspectives of New Music 32 (1): 8–27.

Dibben, Nicola. 1999. “Representations of Femininity in Popular Music.” Popular Music 18 (3): 331–55.

Dubiel, Joseph. 2004. “Uncertainty, Disorientation, and Loss of Responses to Musical Structure.” In Beyond Structural Listening?, edited by Andrew Dell’Antonio, 173–200. University of California Press.

Eate, Penelope. 2013. “Scribblin’ Sinnin’ Sh*t: Narratives of Rape as Masculine Therapeutic Performance in the Strange Case For and Against Tyler, The Creator.” Journal of African American Studies 17: 529–45.

Fisher, George, and Judy Lochhead. 2002. “Analyzing from the Body.” Theory and Practice 27: 37–67.

Gilbert, Jeremy, and Ewan Pearson. 2002. Discographies: Dance, Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound. Routledge.

Gopinath, Sumanth. 2011. “Reich in Blackface: ‘O Dem Watermelons’ and Racial Minstrelsy in the 1960s.” Journal of the Society for American Music 5 (2): 139–93.

Guck, Marion A. 2006. “Analysis as Interpretation.” Music Theory Spectrum 28 (2): 191–209.

—————. 1994. “A Woman’s (Theoretical) Work.” Perspectives of New Music 32 (1): 28–43.

Halberstam, Jack. 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press.

Hisama, Ellie. 2014. “‘Diving into the Earth’: The Musical Worlds of Julius Eastman.” In Rethinking Difference in Music Scholarship, edited by Olivia Bloechl, Melanie Lowe, and Jeffrey Kallberg, 260–86. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2001. Gendering Musical Modernism: The Music of Ruth Crawford, Marion Bauer, and Miriam Gideon. Cambridge University Press.

Jordan, Stephanie. 2007. Stravinsky Dances: Re-visions Across a Century. Dance Books.

Joseph, Charles M. 2011. Stravinsky’s Ballets. Yale University Press.

Kendall, Gustavia Yvonne. 2004. “Theatre, Dance, and Music in Late Cinquecento Milan.” Early Music 32 (1): 74–95.

Kozak, Mariusz. 2015. “ Listeners’ Bodies in Music Analysis: Gestures, Motor Intentionality, and Models.” Music Theory Online 21.3.

Kramer, Lawrence. 2011. Interpreting Music. University of California Press.

Le Guin, Elisabeth. 2005. Boccherini’s Body: An Essay in Carnal Musicology. University of California Press.

Little, Meredith, and Natalie Jenne. 2001. Dance and the Music of J.S. Bach. Indiana University Press.

Long, Duri. 2014. “Listen to the Story: Banksy, Tyler the Creator, and the Growing Nihilistic Mindset.” Journal of Hip Hop Studies 1 (1): 81–120.

Mawer, Deborah. 2006. The Ballets of Maurice Ravel: Creation and Interpretation. Ashgate.

McClary, Susan. 2012. “Dancing Bodies.” In Desire and Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century Music, 193–238. University of California Press.

—————. 1994. “Constructions of Subjectivity in Schubert’s Music.” In Queering the Pitch, edited by Phillip Brett, Elizabeth Wood, and Gary Thomas, 205–34. Routledge.

McKee, Eric. 2012. Decorum of the Minuet, Delirium of the Waltz: A Study of Dance-Music Relations in 3/4 Time. Indiana University Press.

Mead, Andrew. 1999. “Bodily Hearing: Physical Metaphors and Musical Understanding.” Journal of Music Theory 43 (1): 1–19.

Meintjes, Louise. 2004. “Shoot the Sergeant, Shatter the Mountain: The Production of Masculinity in Zulu Ngoma Song and Dance in Post-apartheid South Africa.” Ethnomusicology Forum 13 (2): 173–201.

Okonma, Tyler. 2015. “May 2015.” Golf Wang (blog), Golf Media, http://golfwang.tumblr.com/post/118414277368/it-was-a-period-in-time-where-all-i-wanted-to-do.

Scherzinger, Martin. 2001. “Negotiating the Music-Theory/African-Music Nexus: A Political Critique of Ethnomusicological Anti-Formalism and a Strategic Analysis of the Harmonic Patterning of the Shona Mbira Song Nyamaropa.” Perspectives of New Music 39 (1): 5–117.

Turino, Thomas. 2008. “Old Time Music and Dance: Cohorts and Cultural Formations.” In Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation, 155–88. University of Chicago Press.

Tyler, the Creator. “Yonkers.” YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XSbZidsgMfw.

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. 2008. “Dance Topoi, Sonic Analogues, and Musical Grammar: Communicating with Music in the Eighteenth Century.” In Communication in Eighteenth-Century Music, edited by Danuta Mirka and Kofi Agawu, 283–309. Cambridge University Press.

Footnotes

1. See, for example, Cook 2001, Dibben 1999, Gopinath 2011, Hisama 2001 and 2014, Kramer 2011, McClary 1994, Scherzinger 2001.

Return to text

2. The music video excises the last verse of the song as it was released on the EP Goblin. Example 2 only shows the lyrics that are in the music video.

Return to text

3. Jack Halberstam was known as Judith Halberstam at the time of the book’s publication.

Return to text

4. For example, there are other ways, besides failure, of interpreting the dark unmoving opening of the music video. We might read it as expectant instead, but applying the concept of failure draws out a particular way of hearing it that I would like to explore. We might consider the entire video under different lenses that I have largely suppressed here, such as abjection or apathy, which would yield alternate ways of hearing. Analyzing the video with failure in mind opens the door to interpretive possibilities that I find surprising and exciting.

Return to text

5. This is one of a few such anti-homophobic posts on Tyler’s Instagram, including a rainbow flag and an unflattering photo of Samuel Truett Cathy, the Chick-fil-A CEO who received media attention for homophobic hiring practices and public remarks.

Return to text

6. Given its thoroughly enculturated nature, body movement is never natural nor unfiltered, but always learned and cultivated. I am grateful to Mariusz Kozak for his astute observation that Tyler’s movements fail to do what is culturally expected: that is, to entrain his body to music in normative ways, and the contrived nature of this failure might be read as a failure in and of itself.

Return to text

7. See, for example, Cumming 2000 and Dubiel 2004.

Return to text

8. For recent examples of historically-informed studies of dance and music, see Callahan 2012, Jordan 2007, Joseph 2011, Kendall 2004, Little and Jenne 2001, Mawer 2006, McClary 2012, McKee 2012, and Zbikowski 2008. For recent examples of ethnographic research that provide accounts of the social spaces and cultures that dance musics create, see Gilbert and Pearson 2002, Meintjes 2004, and Turino 2008.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

20878