Review of Justin Merritt and David Castro, Comprehensive Aural Skills: A Flexible Approach to Rhythm, Melody, and Harmony (Routledge, 2016) and Diane J. Urista, The Moving Body in the Aural Skills Classroom: A Eurhythmics Based Approach (Oxford, 2016)

Samantha M. Inman

KEYWORDS: aural skills, Dalcroze eurhythmics, pedagogy

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

[1] The abundance of resources available to aural-skills instructors continues to increase. While the two books reviewed here both organize content into separate modules on specific aspects of rhythm and pitch, they starkly contrast in terms of intended use and approach. In Comprehensive Aural Skills: A Flexible Approach to Rhythm, Melody, and Harmony, Justin Merritt and David Castro of St. Olaf College combine sight-singing and dictation material into a single volume, which could easily serve as the sole resource in a traditional aural-skills sequence. In contrast, The Moving Body in the Aural Skills Classroom: A Eurhythmics Based Approach by Diane J. Urista of the Cleveland Institute of Music is less a textbook for students than a guidebook for instructors on how to incorporate Dalcroze pedagogy into collegiate aural-skills classrooms. Below, I consider each book separately before concluding with some comparisons.

Comprehensive Aural Skills

[2] Comprehensive Aural Skills lives up to its name; together, the book and the companion website contain all the materials needed for an aural-skills curriculum. Unlike The Musician’s Guide to Aural Skills by Phillips, Murphy, Marvin, and Clendinning, CAS is not affiliated with a specific written theory textbook. In that way, its closest cousin on the market is probably Gary Karpinski’s Manual for Ear Training and Sight Singing and the Anthology for Sight Singing that he coauthored with Richard Kram. However, Merritt and Castro include a few post-tonal topics, so the pedagogical endpoint of their melodies is roughly equivalent to that in Cleland and Dobrea-Grindahl’s Developing Musicianship Through Aural Skills or Rogers and Ottman’s Music for Sight Singing.(1)

[3] The effectiveness of Merritt and Castro’s book partially originates in its excellent formatting and organization. Spiral binding allows the printed book to lie flat both on a desk and at a piano, and the 384-page volume is not unduly heavy, making it realistic for students to bring it to class daily. Its three main parts deal with rhythm, melody, and harmony, and each of them divides further into individual modules. Each module opens with up to a page of text discussing the target topic and practice strategies. Next come examples for sight reading and study, followed by blank staves for dictation exercises. Answers to all dictations in the printed chapters are provided in the back of the book, enabling independent dictation practice. The outstanding companion website contains recordings of all dictations included in the book. All recordings for a particular module are on the same web page, minimizing the layers of hierarchy needed to access a particular recording. Students can also download assignment pages and access recordings for homework and quizzes. The recordings feature a variety of acoustic instruments from the string, brass, woodwind, keyboard, and percussion families. Most of the sound clips are of excellent quality; only a few contain minor flaws in intonation or rhythm. Select melodic dictations feature two or three different recordings with different instruments and tempi. A short glossary at the end of the text provides brief definitions of the musical terms used throughout.

[4] The instructor login provides access to materials not available to students. These include a webpage aptly named “How to Use This Text,” in which Merritt and Castro advocate use of rhythmic solmization (providing a brief overview of takadimi as well as systems by Kodály, Gordon, and McHose and Tibbs) and compare movable-do solfège, fixed-do solfège, and scale-degree numbers. Although they prefer the movable-do system, the book could be easily used with any system. Indeed, the printed directions in each module refer to pitches via scale degrees in order to avoid favoring any solfège system. The online instructor resources also include keys for homework assignments and quizzes as well as material for five sight-singing exams. The included Curriculum Guide coordinates the rhythm, melody, and harmony modules and their associated assignments, quizzes, and exams, organizing the material into two four-semester plans, one with post-tonal materials and one without. Although it is possible to use only the provided materials in an aural-skills sequence, some instructors will likely want to supplement them with additional sight-singing and dictation tests.

Example 1

(click to enlarge)

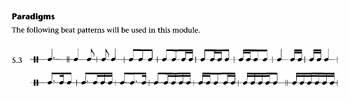

[5] In Part 1, which deals with rhythm, each of the ten modules begins with short paradigms that serve as the basic building blocks of the unit. Example 1 shows the paradigms for Module 5, which introduces compound meter. Paradigms are followed by an abundance of single-line rhythms and several duets for performance. In rhythmic dictation activities, the recording first establishes the meter with two measures of wood block, and then gives the target rhythm on snare drum. Two of the rhythmic modules might seem too fast-paced to some instructors: Module 1 already includes sixteenth notes and dotted rhythms, and Module 2 uses ties to imply occasional 3:4 polyrhythms. The latter is particularly puzzling, as the book omits concentrated study of polyrhythms more advanced than 2:3. However, syncopation receives far more attention here than in some books, and Part 1 concludes with asymmetrical meter. Missing elements include advanced polyrhythms and metric modulation, two topics important to the performance of modern repertoire.

[6] Each of the fourteen melody modules in Part 2 similarly builds from simple to complex: first schematic leaps (such as leaps within the tonic triad in Module 3), then single-line melodies and a few canons or duets, and finally blank staves for dictation. Many of the melodies were composed by the authors, and those from the literature are often identified by composer but not title, making it difficult for instructors to design any contextual listening activities from this material. In contrast to the rhythmic dictations, the melodic dictation recordings do not establish the meter in advance. However, the given staves provide clef, key signature, time signature, and usually the starting pitch. Chromaticism takes center stage in modules 6–11; for example, 9 and 11 are dedicated to modulation to closely related and distantly related keys, respectively. The last three modules turn to post-tonal material, covering diatonic modes, synthetic scales, and a brief introduction to sets and twelve-tone rows. While one of the authors’ suggested curricula allocates the entire fourth semester to post-tonal topics, the included material will likely be sufficient for just half of that without supplementation.

[7] Part 3, on harmony, covers the standard topics of the common practice in fifteen modules, beginning with tonic and dominant and ending with reinterpretations of vii°7. Unlike the parts on rhythm and melody, which provide approximately equal numbers of examples for singing and dictation, the harmony part overwhelmingly emphasizes dictation. Singing examples in each module are limited to short paradigms followed by two or three chorales from the literature, many by J. S. Bach. The instructions emphasize both the function of bass scale degrees and common harmonizations of melodic scale degrees. The dictation material within each module begins with paradigms three to four chords in length, expands to two-measure phrases, and culminates with longer phrases of about four measures. Some of the later progressions feature ornamentation—mostly passing tones, but also suspensions, anticipations, and neighbors. The answer keys show all four voices, leaving the instructor the option of requiring just outer voices or the entire texture. Clefs, starting key, and time signature are always provided for the students, and starting pitches are often given as well. V7 and vii°7 are always paired, not only in the diatonic module 4 but also in modules 8–10 on applied chords. Module 4 includes the submediant triad in some of the progressions even though it is not formally introduced and discussed until module 6. While passing and ![]()

![]()

[8] A few adjustments would have made the book even easier to use. While efficient use of space is mandatory for textbooks that students need to bring to class regularly, the staves included in the text are so small that some students will likely have difficulty writing neatly. Some instructors might object to the voice overlaps that appear frequently in the harmonic progressions. In dictation activities, too much information—including meter, number of measures, key signature, and starting pitch—is given to the students in the printed staves. This does not require the students to hear basic elements for themselves. While this weakness of the book can be sidestepped through the use of manuscript paper in class, students will still have all of this information provided when practicing outside of class. Omitting some of this information from the book would have given instructors more flexibility and control, too. Finally, the typographical errors that often plague the first edition of a textbook are present, including wrong printed notes (1.1), incorrect key signatures (5.8), and discrepancies between given solutions and the corresponding recordings (5.6, 5.27, and 6.21).

The Moving Body in the Aural Skills Classroom

[9] Urista describes The Moving Body in the Aural Skills Classroom as “a practical guide for undergraduate college teachers and students, intended either as a teaching manual or as an aural skills supplementary textbook for students” (1–2). Despite this dual intention, the book serves the first function far better than the second. While the header “Instructor’s Note” appears regularly, the content of the corresponding passages does not markedly differ from the rest of the text, which seems to be directed to teachers, not students. However, the word “supplementary” accurately signals that this book is not intended to serve as the sole resource for an aural-skills curriculum; instructors will need to look elsewhere for sight-singing and dictation material.

[10] Instead, Urista provides an overview of Dalcroze philosophy followed by instructions for an abundance of specific exercises divided by subject. Founded by Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865–1950), eurhythmics, which is named after the Greek word meaning “good flow” (3), uses movement and space to teach musical relationships and processes. While Dalcroze is perhaps best known for the study of rhythm, the complete approach also entails pitch. Urista’s introduction highlights the benefit of developing the ear, mind, and body together, claiming that this approach surpasses traditional methods in musicality and application: “Kinesthetic sensations we experience consciously through movement are later drawn upon subconsciously to enhance future listening and performing experiences” (10). Extensive citations situate the book in relation not only to Dalcroze sources, but also to mainstream aural-skills pedagogy, modern rhythmic theory, and cognition. All three of the main branches of Dalcroze eurhythmics—rhythm, solfège/ear training, and improvisation—receive attention in the six central chapters. These are followed by an index and two appendices, one dealing with “Practical Considerations” and the other listing the “Rules of Nuance, Phrasing, and Accentuation” that are alluded to throughout the book. These rules are particularly valuable in teaching students that many principles of interpretation are generalizable rather than tied to one specific performance of a specific piece.

[11] The first numbered chapter, entitled “Basics,” gives recommendations for how to encourage students to move musically and categorizes the five types of exercises threaded throughout the remainder of the book. The names of these exercise types are part of standard Dalcroze terminology. “Quick-Reaction” exercises require students to respond to unpredictable stimuli in real time, such as switching from stepping on quarter notes to stepping on eighth notes (and vice versa) based on verbal cues from the teacher. “Inhibition and Excitation” exercises ask students to shift between inaction and action, again in response to a verbal or musical cue. For instance, students walk to the beat while one musical texture is present and stand still when the texture changes. Such activities require concentration and build awareness of the function of rests. “Interference” exercises hone the ability to focus on select elements amid distractions, such as maintaining an internal hearing of a particular pitch throughout a highly chromatic chord progression. “Imitation and Canon” exercises build musical memory and the ability to listen to other musical lines while performing. Finally, “Disassociation” exercises involve fluently performing two opposing elements simultaneously, such as clapping a pattern of two-eighths-plus-quarter while stepping a pattern of quarter-plus-two-eighths.

[12] The principal contribution of the book is the set of exercises in Chapters 2–6. The Warm-ups (presented in Ch. 2) are perhaps the least useful of these, resembling icebreakers without content appropriate for a collegiate class. Far more successful are the chapters on Rhythm (Ch. 3) and on Pitch, Scale, and Melody (Ch. 4), which are substantially longer than the others. The chapters on Harmony (Ch. 5) and on Phrase and Forms (Ch. 6) are shorter, yet contain exercises valuable to a freshman-level course. Although Dalcroze traditionally uses fixed do, exercise descriptions are carefully formatted to be as ecumenical as possible regarding solmization systems. For instance, the “Do-to-Do scales” unique to Dalcroze pedagogy are here called “C-to-C scales.” The first part of each chapter covers terminology and methodology related to that subject. Exercises within a chapter are presented roughly in the order in which topics would appear in a course, though the self-contained nature of each activity enables reordering, adding, and deleting with ease. The flexibility in content and ordering constitutes one of the book’s greatest strengths, allowing any instructor to adapt few or many exercises to a particular class.

Example 2

(click to enlarge)

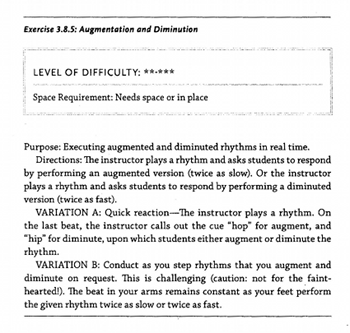

[13] Example 2 reproduces one of Urista’s exercises in order to highlight several features common throughout the book. Immediately following the title, a rating of 1–3 stars indicates the difficulty level. Next come any space requirements: some exercises require open classroom space and others are designed to be performed in place. Example 2 has variants suitable for rooms of different sizes. This clear labeling assists instructors with finding activities that work even within small or crowded classrooms. Most of the exercises require no special equipment, but some call for balls or bungee chords. Example 2 also illustrates the variation impulse threaded through the book. Approaching the same topic and basic activity through several variations (e.g., clapping, stepping, and conducting in different permutations) fosters fluency and allows the instructor to adapt the difficulty level to students’ needs in real time.

[14] In contrast to the cornucopia of ideas in the text, the companion website is unfortunately sparse. Given the difficulty of using prose to convey the dynamism, interactivity, and joy characteristic of the Dalcroze approach, this lost opportunity to provide illustrative videos constitutes the biggest weakness of the publication. Of the 140 or so exercises in the book, only ten have corresponding videos. Of those ten, six lack sounding music, giving the false impression that the Dalcroze approach is more physical than musical. Readers desiring further demonstrations of eurhythmics might turn to videos by others available on the Dalcroze Society of America website (http://www.dalcrozeusa.org) or YouTube, but it would have been preferable to watch Urista and her students enacting some of the specific exercises described in the book. Nevertheless, the clarity and organization of the printed directions still render the book valuable to a variety of aural-skills instructors, ranging from those wishing to infuse the embodied approach into their entire curriculum to those simply seeking additional activities in support of a specific topic.

Conclusion

[15] Both of these new volumes add significantly to the resources available to aural-skills pedagogues. Comprehensive Aural Skills effectively combines singing and dictation activities in rhythm, melody, and harmony into a single book, and the high quality of the recordings makes Merritt and Castro’s print-plus-digital package far more attractive than many automated dictation programs with low-quality MIDI. The inclusion of answer keys at the back of the book also makes this a viable resource for supplemental practice or even independent study. Instructors will still need to write dictation exams and likely additional material for sight-singing tests, but nearly everything else needed for a four-semester curriculum is provided. In contrast, The Moving Body in the Aural Skills Classroom does not seek to serve as an omnibus text. Instead, this book introduces the rich world of Dalcroze pedagogy in a format accessible even to those instructors with no experience in eurhythmics. The extensive catalog of exercises should prove useful in a wide variety of teaching contexts, allowing for flexible incorporation of any number of activities into any curriculum. While contrasting in intended use and approach, both books reviewed here merit careful consideration.

Samantha M. Inman

School of Music

Stephen F. Austin State University

Box 13043, SFA Station

Nacogdoches, TX 75962-3043

samantha.mae.inman@gmail.com

Works Cited

Cleland, Kent D., and Mary Dobrea-Grindahl. 2015. Developing Musicianship through Aural Skills: A Holistic Approach to Sight Singing and Ear Training, 2nd ed. Routledge.

Clendinning, Jane Piper, and Elizabeth West Marvin. 2016. The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis, 3rd ed. W. W. Norton.

Karpinski, Gary S. 2017. Manual for Ear Training and Sight Singing, 2nd ed. W. W. Norton.

Karpinski, Gary S., and Richard Kram. 2017. Anthology for Sight Singing, 2nd ed. W. W. Norton.

Phillips, Joel, Paul Murphy, Elizabeth West Marvin, and Jane Piper Clendinning. 2011. The Musician’s Guide to Aural Skills, 2nd ed. W. W. Norton.

Rogers, Nancy, and Robert W. Ottman. 2014. Music for Sight Singing, 9th ed. Pearson.

Footnotes

1. With the exception of Rogers and Ottman 2014, each text mentioned in this paragraph also features a companion website with sound recordings.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2018 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Samuel Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4973