Review of Yayoi Uno Everett, Reconfiguring Myth and Narrative in Contemporary Opera (Indiana University Press, 2015)

Wesley J. Bradford

KEYWORDS: narrative, opera, analysis, semiotics, myth

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1] Yayoi Uno Everett’s Reconfiguring Myth and Narrative in Contemporary Opera (hereafter RMNCO), a recent addition to Indiana University Press’s popular Musical Meaning and Interpretation series, demonstrates the theoretical and analytical potential within contemporary opera. Expanding upon Abbate 1991, Everett adapts work on musical narrative and semiotics (such as Almén 2008) to explore various productions of contemporary operas by Osvaldo Golijov, Kaija Saariaho, John Adams, and Tan Dun. She does not assume that her readers are intimately familiar with these operas, and provides enough context in each chapter to guide those who are interested primarily in the theoretical aspects of her analyses. Likewise, her theoretical discussions are generally clear and accessible enough that opera enthusiasts can develop a deeper appreciation for their favorite opera even without an in-depth knowledge of semiotics (although such knowledge is certainly beneficial). Therefore, Everett’s concise work can provide a point of entry into both modern opera and theories of narrative and semiotics.

[2] RMNCO is organized into five chapters plus a brief epilogue. Chapter 1 explains Everett’s methodology in depth; and each of chapters 2 through 5 offers, for an individual opera, an overview of its plot and production history, a musical analysis that considers the effects of staging and production, and finally some analytical conclusions. This format allows Everett to shift her analytical focus while retaining a clear structure, preventing readers from becoming lost in the flow of ideas. The analyses include informative graphics and annotated score excerpts, as well as some production photos. Unfortunately, and despite Everett’s references to the psychological importance of color (69–71), the photos are black and white, presumably due to publishing restrictions. RMNCO includes an index as well as a separate glossary of specialized terms used throughout the book. The index illustrates the breadth of topics intertwined in RMNCO and also serves as a useful resource on semiotic, musical, and narrative terms.

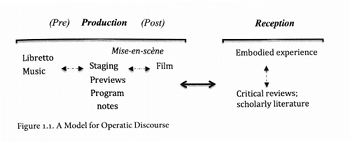

Example 1. Everett’s model for multimodal discourse (p. 3)

(click to enlarge)

[3] Everett’s analyses incorporate not only the music and libretto, but also the staging and production elements of an opera, resulting in a “multimodal” analysis. Her model is reproduced in Example 1. Building upon Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen’s (2001) discussion of modes of communication, she defines multimodality as the process of “decoding these [various sensory] elements from an interpreter’s standpoint” (3). She strives to develop a holistic discourse on opera in which consideration of the musical score and libretto is merely the first step. It is followed by attendance at a live performance or high-quality broadcast and by interviews of composers, directors, and/or librettists when possible (2). Everett thoroughly documents her analytical process and provides nuanced interpretations that incorporate music, text, lighting, costumes, and set design. The result is four satisfying analyses—each a kind of performance in its own right—that encompass the entire operatic experience. Considered together, the four unique perspectives highlight the flexibility of the multimodal analytical technique.

[5] From a musical perspective, Everett’s monograph engages directly with and extends recent work by Byron Almén (2008, 2012), Raymond Monelle (2000), Andrew Davis (2010), Carolyn Abbate (1991), and Robert Hatten (1994, 2004, 2012). Everett builds on Monelle’s and Davis’s uses of a Greimassian square to demonstrate dynamic changes in actantial roles within operatic narratives. Additionally, she expands upon Almén’s narrative archetypes, noting that operas such as Turandot “often resist being boiled down to one particular narrative archetype, due to the multiplicity of readings that arise from competing narrative trajectories” (23). Instead of attempting to place each opera neatly within a narrative category, Everett focuses on interpreting multiple transvaluations within each operatic narrative. Further, she argues that the multiple narrative trajectories and episodic formats of modern operas encourage audiences to consider deeper, allegorical meanings (29). While the reader may or may not agree with Everett’s allegorical conclusions, her flexible analytical process is consistently elegant throughout the book.

[6] In conjunction with narrative archetypes, theories of motives, semes, and topics also inform the analytical approach in RMNCO. For Everett, a seme is “a minimum unit of signification that shapes the expressive meaning of a motive, topic, phrase, or chordal unit” (26). She argues that “musical semes can be defined dynamically in relationship to other production components (film, objects, lighting, mime or dance) as conveyors of hidden, unconscious layers of meaning that emerge” (26). Unlike topical functions, semes are contextual and resist fixed categorization, changing over the course of a production. These semes, along with leitmotivs and topics (as defined by Monelle 2000: 17), constitute a significant part of Everett’s discussions, especially in chapters 4 and 5. With these tools, she points out subtle connections between music and other elements of the operatic experience, preparing readers to actively hear—or rehear—these modern works.

[7] The titular reference to “Reconfiguring” myth alludes to Everett’s goal of demonstrating interactions between modern opera and myth through her multimodal analyses. She draws on writers such as Lévi-Strauss (1969), Tarasti (1979), and Barthes (1972) to formulate a view of mythic narrative in modern opera, claiming that myth can identify particular historical figures yet place them in a setting that “gives the impression of having taken place in a time so far back that a precise date cannot be ascertained” (9). Each of the operas considered in RMNCO portrays specific historical events or figures either directly or indirectly, but modern opera, Everett argues, does not simply retell stories. Instead, these works, such as Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, foreground “metaphor and symbolism … turning historical subjects into textualized representations” (10). The operas move between the world of the real and that of the fantastic, and Everett guides readers through the implications and intertextual references of that journey.

[8] Chapter 2 contains a full analysis of Ainadamar by Osvaldo Golijov, an opera that has enjoyed a rich production history. It was premiered in 2003, reworked in 2005, and then staged eleven times over the course of 2007–8, as well as performed in concert and semi-staged productions. The variety of production styles suits Everett’s approach, as she is able to focus not only on the musical content, but also on the expressive effects of various staging techniques. The connections that she draws between narrative expressions and musical styles constitute this chapter’s most compelling analytical content. It is clear that, for Everett, Golijov’s compositional choices are a driving force behind the dramatic plot. After establishing these connections, Everett explores the effects of staging. The results of the multimodal analysis demonstrate the power of production decisions to manipulate the message of an opera as forged through the central relationship between music and drama. Her discussion of the effects of staging choices is hurt most in this chapter by the black-and-white photos intended to illustrate differences in lighting between various scenes. Her prose nonetheless provides enough information to convey her ideas.

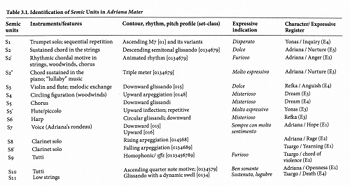

Example 2. Everett’s eleven semic units for Adriana Mater (p. 91)

(click to enlarge)

[9] Everett’s analysis of Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater in chapter 3 builds on Liisamaija Hautsalo’s (2011) work on topics in Saariaho’s music. However, instead of identifying topics, Everett notes eleven semic units that “carry psychological resonances, but resist fixed topical identification” (89). Example 2 reproduces Everett’s chart summarizing the semic units, which convincingly draw from Saariaho’s sketches as well as Everett’s own analysis of the music. After establishing the idea of semic units and the opera’s primary dramatic oppositions, she illustrates the interrelationships among the various occurrences of semic units in their performance context. This chapter contains more musical examples than any other chapter (11 in total), and the majority of the examples contain annotations detailing active semic units. In contrast to the analysis of Golijov, which focuses on production values, the discussion of Adriana Mater deals primarily with how Saariaho’s music embodies and comments on the libretto, illustrating a detail-oriented application of multimodal analysis.

[10] The third analytical chapter considers John Adams’s Doctor Atomic. It begins with a brief historical introduction to the opera and an overview of the quasi-Faustian plot. Questioning the correlation between Doctor Atomic and Faust quickly becomes a central theme of Everett’s analysis, along with a focus on signifiers of time. After considering topical ideas, musical intertextuality, and large-scale harmonic motion, Everett returns to the Faustian nature of the plot. She draws on Joseph Campbell’s mythic cycle and narrative ideas of transvaluation to determine that “Faustian intertexts are not literally present in Doctor Atomic, but figuratively present in the articulation of the individual and collective modes of striving” (157). Her argument is compelling; it emphasizes how Doctor Atomic lacks the final resolution of ascension for the hero, but instead falls into a “temporal collapse” (157). This analysis rests largely on the intricate temporal signifiers in Adams’s post-minimalist music. Everett places Adams’s musical procedures on a continuum that “ranges from non-referential to referential: ‘filler’ music, proto-topics, stylized quotation, and electronic collage” (134). Though this analysis largely eschews surface-level details, Everett clearly defines terms—including musical procedures and concepts such as musematic repetition, discursive repetition, ontological time, and psychological time—all while exploring the various referential levels of the music and libretto of Doctor Atomic.

[11] The final portion of the chapter focuses on the staging of two specific productions of Doctor Atomic: Peter Sellars’s 2007 version for the Netherlands Opera and Penny Woolcock’s 2008 interpretation for the Metropolitan Opera. Everett isolates four scenes to illustrate the dramatic differences between Sellars’s and Woolcock’s productions. She suggests that Sellars consistently aligns the various modes of presentation by linking visual, musical, and textual elements, creating a work with a single underlying message. Woolcock, in contrast, “purposefully avoids a facile synchronization among music, text, and visual media” (162), which results in a “collision” between historical and mythological references in the opera (163). Again, elements of time and myth are foregrounded in Everett’s discussion, highlighting the interrelationships among various modes of perception. In her conclusion, she again notes how the theme of striving underlies both Doctor Atomic and the Faust myth (although it is emphasized differently by various productions). The impact of the analysis is a testament to the robust and flexible nature of her analytical technique.

[12] In her final chapter, Everett explores Tan Dun’s The First Emperor, demonstrating another facet of multimodal analysis by centering the discussion on issues of culture and reception rather than staging. She notes that the opera underwent major revisions after its 2006 premiere due to mixed reviews. Like the other operas in this book (save perhaps for the Adams), The First Emperor is not widely known, and Everett devotes a generous discussion (more than five pages) to the reception history of the story that Tan Dun adapted. The length is warranted, however, because this history is a central part of her analysis. Her musical discussion then identifies various themes and leitmotifs that, rather than being associated with specific characters, assume roles at higher narrative levels, such as “fate,” “lament,” or “yearning.” The themes appear with various characters depending on the narrative action that accompanies the scene. Her analytic observations skillfully convey relationships between themes and demonstrate how the opera reflects Tan Dun’s aesthetic of “1+1=1,” in which two different cultural units can be combined into a seamless and unique whole (166). Everett also addresses how her work compares to the analysis of The First Emperor by Anthony Sheppard (2009). Both analyses take Puccini’s Turandot as a point of comparison, though Everett claims that hers highlights compositional differences while Shepphard’s emphasizes similarities. Her analysis concludes with an intriguing summary of correlations between musical elements (i.e., themes and leitmotifs) and higher-level narrative elements (e.g., yearning, prophecy, resistance).

[13] This last chapter also considers differences between American and Chinese cultural receptions of the opera. Everett notes that many Americans have criticized Tan Dun for not conforming The First Emperor to musical traditions of Western grand opera. Meanwhile, Chinese viewers criticize the opera’s negative view of the title role. Everett uses these conflicting viewpoints as an allegory for the relationship between art and politics. This final section adds yet another mode to Everett’s “multimodal” analysis style by incorporating political and allegorical intertexts into the artwork. While not examined as thoroughly as other modes, it recalls the attempt at a holistic understanding of opera shown in Example 1. As Everett emphasizes throughout her text, an opera’s cultural context and reception are just as vital to grasping its meaning as its sounding music, written score, and libretto.

[14] With relative brevity, RMNCO highlights the value of analytic breadth by incorporating multiple modes of perception. In applying these modes, Everett demonstrates the important analytical consequences of staging, text, music, intertextuality, and cultural interchanges. Her analyses serve as important reminders that a work of art, whether in the concert hall or on the stage, is not a static object; instead, it is constantly open to reinterpretation and appropriation by artists and audiences alike. The book is at its most compelling when the reach of its analytic methodology is at its widest. By not only suggesting a multimodal approach that incorporates narrative and other semiotic theories, but also demonstrating specific results of this analytical method, Everett suggests potential avenues for the analysis of other genres of music, theater, and the performing arts more generally. By bringing all of our senses into play and questioning the sources of meaning within the operatic genre, her book invites us to reconsider how we understand musical experiences.

Wesley J. Bradford

University of Louisiana at Lafayette

P.O. Box 43572

Lafayette, LA 70504

wbradford@louisiana.edu

Works Cited

Abbate, Carolyn. 1991. Unsung Voices: Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton University Press.

Almén, Byron. 2008. A Theory of Musical Narrative. Indiana University Press.

Almén, Byron, and Robert S. Hatten. 2012. “Narrative Engagement with Twentieth-Century Music: Possibilities and Limits.” In Music and Narrative Since 1900, ed. Michael L. Klein and Nicholas Reyland, 59–85. Indiana University Press.

Barthes, Roland. 1972. Mythologies, trans. Annette Lavers. Hill and Wang.

Davis, Andrew C. 2010. Il Trittico, Turandot, and Puccini’s Late Style. Indiana University Press.

Hatten, Robert S. 1994. Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, and Interpretation. Indiana University Press.

—————. 2004. Interpreting Musical Gestures, Topics, and Tropes: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert. Indiana University Press.

Hautsalo, Liisamaija. 2011. “Whispers from the Past: Musical Topics in Saariaho's Operas.” In Kaija Saariaho: Visions, Narratives, Dialogues, edited by Tim Howell, John Hargreaves, and Michael Rofe, 107–29. Ashgate.

Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. Hodder Education.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1969. The Raw and the Cooked, trans. John and Doreen Weightman. The University of Chicago Press.

Monelle, Raymond. 2000. The Sense of Music: Semiotic Essays. Princeton University Press.

Sheppard, W. Anthony. 2009. “Blurring the Boundaries: Tan Dun’s Tinte and The First Emperor.” The Journal of Musicology 26 (3): 285–326.

Tarasti, Eero. 1979. Myth and Music: A Semiotic Approach to the Aesthetics of Myth in Music, especially that of Wagner, Sibelius and Stravinsky. Mouton Publishers.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4420