Review of Theodor W. Adorno, Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen, edited by Klaus Reichert and Michael Schwarz (Suhrkamp, 2014)

Christoph Neidhöfer

KEYWORDS: Darmstadt, Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, Wagner, counterpoint, twelve-tone technique, serialism, timbre, informal music, material theory of form

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1] The close connection between the music philosophy of Theodor W. Adorno (1903–69) and the developments of the post-World War II musical avant-garde is as well known as it is complex. The influence went both ways: on the one hand, Adorno’s advocacy for the music of the Second Viennese School—his pointed criticism of twelve-tone technique notwithstanding—and his notion of “integral composition” constituted a strong force behind the proliferation of pluridimensional serial techniques. On the other hand, the paths taken by the musical avant-garde in the 1950s and 1960s drove Adorno continuously to revisit and expand his music philosophy. He tried to keep up with the most recent music and actively sought a critical dialogue with younger composers, but struggled at times to grasp the full extent of the latest advances in compositional technique and style. Among the locations where this dialogue took place were the “Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik” in Darmstadt, where Adorno served on the faculty or appeared as guest speaker several times between 1950 and 1966 (Tiedemann 2001). In five of these summer courses, Adorno was invited to present a series of lectures, which have been preserved in live recordings at the International Music Institute in Darmstadt. While Adorno reworked the second through fourth lecture cycles into articles that are well known (with a full transcription of the fifth cycle published posthumously), the content of the often more extensive lectures themselves had remained inaccessible outside the archives until the recent publication of these talks under the title Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen (“Kranichstein Lectures”), part of the edition of Adorno’s unpublished texts issued by the Theodor W. Adorno Archive.

[2] Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen, superbly edited by Klaus Reichert and Michael Schwarz, presents transcriptions of Adorno’s mostly freely spoken talks. (Kranichstein is the name of the hunting castle where the Darmstadt courses initially took place, from 1946 on, outside the almost completely destroyed city.) The 672-page volume is copiously annotated with 353 often extensive footnotes. It reproduces the notes from which Adorno gave the first, second, and fifth lecture cycles, and concludes with an editorial afterword, index, and detailed list of topics for each lecture. Furthermore, the book is accompanied by a DVD that contains the audio recordings of the lectures.

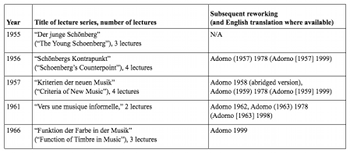

Figure 1. Adorno’s five Darmstadt lecture cycles

(click to enlarge)

[3] Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen features all multi-lecture series that Adorno gave at the Darmstadt festival; Figure 1 lists for each of these the year, title, number of lectures, and subsequent reworking in print, where applicable.(1) Not all of the lectures are documented in their entirety on the archival recordings, and hence in the editors’ transcriptions, due to tape changes or other circumstances. Most recordings last between 70 and 110 minutes each, adding up to over 24 hours of lecturing documented on the DVD. In what follows, I will survey a few of Adorno’s core arguments that run through these talks. Since virtually all of the topics are familiar, in one fashion or another, from Adorno’s writings, I will focus on how he presents his ideas in the Darmstadt context, on the occasionally provisional character of his argument, and on interesting details that Adorno eventually omitted from print versions of his talks.

[4] This edition is a real delight in how it brings alive the thought processes and arguments of the principal music philosopher associated with the Second Viennese School and the musical avant-garde. The recordings capture Adorno speaking quite slowly and choosing his words carefully, and while his sentences are often rather long, they are easier to follow than the characteristically long clauses in his writings because his vocabulary and sentence structures tend to be more straightforward in speech than in print. Occasionally, Adorno allows himself to put things more simply than befits an issue, or to choose a term that he says he would not use in writing, in order to move swiftly to the heart of a matter. He is quick at citing, seemingly spontaneously at times, specific musical features and passages to clarify a theoretical point, but he then sometimes omits such references later in the published version of an article, presumably for fear of underrepresenting the complexity of an issue. In the first two lecture series, Adorno demonstrates numerous musical examples at the piano, mostly from scores by Arnold Schoenberg. If ever anyone doubted Adorno’s musicality, these recordings of him performing excerpts from tonal and free atonal works with agility, superb touch, and evocative phrasing, as well as accompanying himself singing through songs by Schoenberg, will put such doubts to rest once and for all. Adorno—who, after his doctorate in philosophy in Frankfurt, had studied composition with Alban Berg and piano with Eduard Steuermann in Vienna from 1925 on—clearly loves this repertoire and is intimately familiar with it. He shows himself here at his best as a hands-on, practical music analyst when it comes to nuts-and-bolts analytical questions. He was critical of positivist music analysis and often shied away from it, but as we know from his monographs on Berg, Mahler, and Wagner and other writings, and as we can now witness here in his Darmstadt lectures, this was not for lack of analytical skill. The analyses he presents at the piano are generally straightforward to follow with the scores, which are easily available and not excerpted in this edition. Also not provided are transcriptions into staff notation of Adorno’s illustrations at the piano, where he alters a chord or a phrase in a passage in order to make an analytical point. Some of these illustrations are particularly insightful and I will discuss a few below.

[5] Since his Darmstadt audience consisted largely of composers, performers, music critics, and music theorists and analysts—the kind of practice-oriented audience he was indeed eager to address—Adorno limited the amount of abstract philosophical discourse, anchoring larger aesthetic issues to concrete musical questions and repertoire. Two broad issues run as leitmotivs through these lectures: the constant challenge of defining aesthetic categories in terms of concrete compositional techniques, and Adorno’s skepticism toward systematized techniques such as twelve-tone procedure, which in certain forms he found regressive. His take on these matters would have been familiar to readers of his Philosophy of New Music, first published in 1949 (Adorno [1949] 2006), but in 1950s Darmstadt his views entered a wider context, and gained fresh momentum, vis-à-vis the rapidly expanding procedures of integral serialism. These procedures, Adorno maintained, only exacerbated the dilemma of twelve-tone technique that he had already identified in Philosophy of New Music; he took the recent developments in serial technique as a sign that new music was growing old. His first lecture cycle in Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen followed the attack on integral serialism that he had presented recently in 1954–55 under the title of “The Aging of the New Music” (Adorno [1954/55] 2002), and in the face of the backlash against his critique, he returned repeatedly to this topic in his lectures.(2)

[6] It is in this context that we need to understand Adorno’s choice of topic for the 1955 lectures—the young (i.e., tonal) Schoenberg—a topic that, one might think, would hardly have been of burning interest to young avant-garde composers at the time, who were focused more on the latest serial achievements and who were, in terms of compositional technique, decidedly moving beyond Schoenberg. (Think of Boulez’s then recent Structures I from 1951–52 or Stockhausen’s Kontra-Punkte from 1952–53, for instance, and of Boulez’s 1951 article “Schoenberg is Dead” [Boulez [1952] 1991]). In “The Aging of the New Music,” Adorno had argued that the avant-garde had taken refuge in compositional techniques that no longer came with the “explosive power” that once characterized atonal music such as Webern’s Five Movements for String Quartet op. 5: “In the leveling and neutralization of its material [through integral serialism], the aging of the New Music becomes tangible: it is the arbitrariness of a radicalness for which nothing is any longer at stake” (Adorno [1954/55] 2002, 185). For Adorno, the avant-garde’s obsession with serialism was missing out on the kind of musical depth that is not guaranteed by that technique in the first place: “While New Music, and particularly Schoenberg’s achievement, is stamped as twelve-tone composition, and thus handily pigeonholed, the fact that a very large [part] and perhaps, qualitatively, the decisive part of this production was composed prior to the invention of this technique or independently of it, should give reason to pause” (ibid.). Adorno’s point was taken at the time to be regressive, which he contested and sought to clarify in his Darmstadt talks. What he meant was that the avant-garde needed to develop its own new categories to reach deeper musical meaning rather than perpetuating a technique that, in his opinion, had lost its original impetus. For Adorno, serialism made composition too easy and hence was no longer justified (15). Thus, by focusing on Schoenberg’s early music in the first lecture cycle, he explained,

“I would like to encourage especially young composers, the twelve-tone composers, to become, in a way, more self-critical in their own method by measuring what you do against the indescribable wealth and indescribable substance that we find precisely in the young Schoenberg—which are the foil for the asceticism [and] all of the refusals that Schoenberg later implemented” (15).(3)

[7] Adorno was not, and did not claim to be, in a position to spell out a concrete program for how to move forward until six years later in his 1961 talks on “Vers une musique informelle,” by which time Darmstadt had entered a new phase. The first three lecture cycles of 1955–57 (with their focus on Schoenberg, counterpoint, and criteria for new music, respectively), along with Adorno’s gradual catching up on the latest compositional developments during those years, constituted the preparation for formulating such a vision of “informal music,” a vision that was impacted by John Cage and “post-serial” thinking. In essence, “informal music” is that which moves beyond the achievements and shortcomings of new music from the recent past through “a rhythmic flexibility that up to now we can hardly imagine” (“eine Flexibilität des Rhythmus, von der wir uns bis jetzt überhaupt kaum eine Vorstellung machen,” 444); it reestablishes a “non-static experience of time” (“nicht-statische Zeiterfahrung”) so that music attains again a state of becoming (“daß dadurch die Musik wieder zu einem Werdenden wird,” 445), and so forth. Such an “informal music” did not yet exist, however, as Adorno explained at the end of the last lecture in 1961, because “the dream of music that governs us [

Example 1. Schoenberg, op. 2, no. 1, “Erwartung,” neighbor chord motion in piano of m. 1

(click to enlarge)

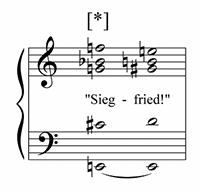

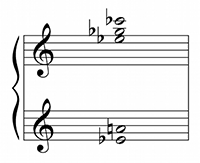

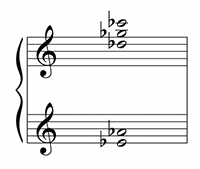

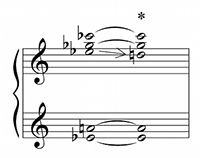

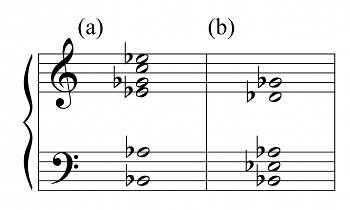

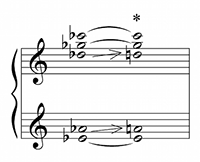

[8] In the first lecture cycle of 1955, on the works of the young Schoenberg, Adorno’s central thesis is that they have, in the spirit of Jugendstil, a tendency “to want simultaneously to break free of and to remain within” nineteenth-century conventions (“daß sie gleichzeitig ausbrechen und drinbleiben wollen,” 25). He illustrates this at the piano (27; DVD, track 1, starting at 46:38) with the neighboring chord that opens and returns throughout the first of the Four Songs op. 2, “Erwartung” (Example 1). Adorno shows how Schoenberg’s chord (Example 2) has a “much stronger lye” (“viel stärkere Beize”) than a more conventional neighboring dominant ![]()

![]()

Example 2. Schoenberg’s neighbor chord (click to enlarge) Example 4. Wagner, Götterdämmerung, Act 3, scene 1, neighbor-chord motion (click to enlarge) | Example 3. “Dominant (click to enlarge) Example 5. Quartal harmony (transcribed from recording) (click to enlarge) |

Example 6a. Adorno’s derivation of Schoenberg’s neighbor chord (*) from a “dominant (click to enlarge) Example 7. Adorno’s comparison of Schoenberg’s chord from m. 42 of Verklärte Nacht op. 4 (a) with quartal harmony (b) (transcribed from recording) (click to enlarge) | Example 6b. Adorno’s derivation of Schoenberg’s neighbor chord (*) from quartal harmony, illustrated (click to enlarge) Example 8. Adorno’s illustration of how Schoenberg could have sequenced the first-violin melody in mm. 34–35 of Verklärte Nacht (a), but chose not to do so (b) (transcribed from recording) (click to enlarge) |

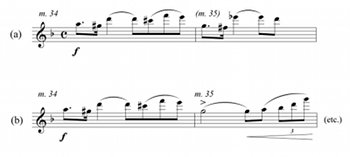

[9] Another element that Adorno singles out in Schoenberg’s early music is the composer’s “sensitivity against repetition” (“Empfindlichkeit gegen die Wiederholung,” 39) and his breaking of symmetries. This, as Adorno demonstrates at various points, has to do with the principle of “consequence” (“Konsequenz”) that drives Schoenberg’s music (101–2, 121–22). As examples, he illustrates irregular phrase structures in “Du wunderliche Tove!” from Gurrelieder (103; DVD, track 3, 53:16; page 58 in the vocal score prepared by Alban Berg) and several other variation techniques. Adorno explains at the piano how Schoenberg could have taken the first-violin motive in m. 34 of Verklärte Nacht and sequenced it in the following measure, as transcribed in Example 8a, but instead chose to continue “completely differently,” as shown in Example 8b (49; DVD, track 2, 6:47), because sequenced repetition would not have been justified here within the overall trajectory of this theme starting in m. 29.(7)

Example 9. Verklärte Nacht, mm. 75–76, first violin

(click to enlarge)

Example 10. Schoenberg, First String Quartet op. 7, mm. 97–102

(click to enlarge)

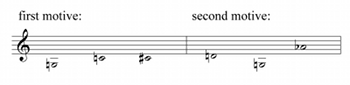

[10] Adorno takes a special liking to what he calls “axial rotation” (“Achsendrehung”), by which he means either a permutation of pitches or intervals, or an arrangement of pitches around a fixed axis, and which he associates with the broader concept of developing variation and the interplay of unity and variety in Schoenberg’s music. An example is what Adorno describes as “an entirely new motive” in mm. 75–76 of Verklärte Nacht (Example 9), “which, however, is related to the first main theme” (Example 8b) through similar melodic intervals of minor seconds, augmented fourth/diminished fifth, and minor/major third (52; DVD, track 2, 14:43).(8) The “axis” in “Achsendrehung” may actually be a specific pitch, as Adorno suggests about the second violin of the fugato from the First String Quartet op. 7 (Example 10). He analyzes the second motive as a “rotated” version (“achsengedreht”) of the first (Example 11) around the stationary G3 shared by the two. Without spelling out the criteria for his choices, he states: “Whereby I would say: [Example 11, first motive] corresponds now to [Example 11, second motive]. [D4] corresponds to [C4], [

Example 11. First and second motive from Schoenberg op. 7, mm. 98–100, second violin (click to enlarge) | Example 12. Illustration of Adorno’s derivation of the second motive from the first (click to enlarge) |

[11] Adorno’s analyses generally take a bottom-up approach, moving from motivic-thematic details to larger formal units, somewhat parallel to the path one imagines the compositional process may have taken.(10) Practicing analysis as he had learned it as a member of the Second Viennese School, he was well aware of the limitations of the motivic-thematic and harmonic methods of analysis that he was using, particularly their emphasis on individual features at the expense of a synoptic view of the whole work. In “On the Problem of Musical Analysis,” a talk that he gave toward the end of his life at the Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst in Frankfurt, Adorno concludes, after describing the character of Berg’s music as “that of permanent reabsorption back into itself”:

This means that such a structuring of the inner fiber of a music also calls for an analytical practice completely different from the long-established motivic-thematic approach [. . . ]. However, I don’t in the slightest flatter myself as in any way having succeeded in fulfilling this demand, and what I say here as criticism of analysis in general also applies without reservation as a criticism of all the countless analyses that I myself have ever produced (Adorno 2002, 177).(11)

In various writings and talks in the 1960s, Adorno outlined what he called a “material theory of form” that would reach beyond the form-functional classifications established by the Schoenberg school to include an expanded set of categories (such as “suspension,” “breakthrough,” “fulfillment,” etc. for Mahler’s music, but also more conventional form-functional types such as “statement,” “contrast,” and “dissolution”).(12) “These [i.e., dialectical] categories,” Adorno explains,

are more important than knowledge of the traditional forms as such, even though they have naturally developed out of the traditional forms and can always be found in them. [. . . ] It [i.e., such a ‘material theory of form’] would not, to be sure, be fixed and invariable—it would not be a theory of form for once and always, but would define itself within itself historically, according to the state of the compositional material, and equally according to the state of the compositional forces of production (Adorno 2002, 177–78).

Adorno concludes that “so far not even the beginnings of an approach have been made regarding such a ‘material theory of form’ (as opposed to the architectonic-schematic type of theory)” (Adorno 2002, 177), but I would argue that there are intimations in his Darmstadt lectures of how such an integral analysis could look. Many of the works that he discusses are ones that he has clearly analyzed for himself in their entirety, even though time did not permit him to deal with them fully. He has carefully considered an excerpt’s place and function within the entire work or movement and he specifically addresses this aspect when he does have the time to discuss entire movements, such as the first and fourth songs from Schoenberg’s op. 2, which he performs and comments on in their entirety. In op. 2, no. 1, for instance, Adorno discusses the “consequences” that the opening chord (Example 1) has for the rest of the song (30; DVD, track 1, 54:58). For him, the opening chord makes one “shiver” (“Schauer”), a sensation that cannot be triggered repeatedly by the same chord each time it reappears. The song’s tension, which remains unsolved according to Adorno, thus consists in the conflict created by the chord’s repetition in various transpositions; the chord is both the same and not the same as the song progresses.

[12] By focusing on the early tonal music of Schoenberg in the first lecture cycle, Adorno wants to demonstrate to young composers in Darmstadt how, when venturing into new territory, they need to be in full command of what came before and to be clear about precisely what they are leaving behind. He chooses the fourth song of op. 2, for instance, to show “what possibilities, indeed, of musical happiness and musical riches this composer really sacrificed by virtue of an urge [to break away] that was stronger than anything else” (44).(13) In the fifth lecture cycle (1966), Adorno reiterates the same point, now with respect to orchestration: “that one needs to be clear about what is being forgotten and what is no longer of interest” (472).(14) “There is a difference,” he insists, “between forgetting something simply because one just forgets it and forgetting something as the result of critical reflection” (473).(15)

[13] Throughout Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen, Adorno uses his analyses to corroborate criteria for what he believes to constitute good music. Stating in the second lecture series, for instance, that in bad counterpoint there is either too little or too much independence between voices (142), he insists that “counterpoint must be such that it overcomes, out of its own strength, so to speak, the moment of accident, that thus the added voices themselves in their relationship with the given voices have the character of necessity” (143).(16) Upholding developing variation and minimization of repetition (including sequence) as ideals, Adorno finds “the traditional means” of canonic imitation “extremely problematic” because they do not solve adequately the “problem” posed by counterpoint, which he defines as: “How can I write free and nevertheless binding counterpoint?” (145).(17) Basically, canonic imitation is too easy a solution and not “free” enough, and this explains his skepticism, already known from his earlier writings, towards Webern’s canonic techniques. In Schoenberg’s developing variation, on the other hand, Adorno observes that canonic artistry takes a backseat, with “imitative counterpoint almost always occur[ring] where there are dance types [

[14] Of the many further theses and criteria that Adorno sets forth in these lectures, suffice it to mention just three, from the fifth lecture cycle (1966) on the function of timbre in music. Orchestration has to be “structural instrumentation,” Adorno insists—that is, it must be motivated by the compositional structure and not consist of “an isolated presentation of colors” (“isolierte Präsentation von Farben,” 488). Intentional imbalance in orchestration can serve a specific function, such as in m. 121 of the third movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, where a double stop in the first violins is set against the rest of the orchestra. (Adorno draws a beautiful parallel here with a passage on the sublime in Kant’s Critique of Practical Reason, 466–67.) And when it comes to orchestration in certain works of the Second Viennese School, such as Berg’s Three Orchestra Pieces op. 6, Adorno gives as a rule of thumb “that as a general tendency no pitches of the same sound family should be directly superimposed” (509), but rather pitches with more or less different timbres.(20)

[15] Given its almost conversational style, its relatively slow pace, and its many musical illustrations, Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen can serve as a good introduction to Adorno’s music philosophy. We can sense at every turn Adorno’s reluctance to accept any answer that seems too straightforward, any procedure that makes composition too easy, or any analytical insight that does not take a holistic, dialectical approach. While Adorno’s greatest contributions remain largely speculative by their very nature—such as his visions of a “material theory of form” and an “informal music,” which propose solutions to the analytical and compositional problems he had identified over the course of his career—hearing him play and explain music does get us closer to what he was after. The lectures from 1956, 1957, and 1961 are often easier to understand than their published versions because the lectures are less dense and elliptical, and contain numerous clarifying examples as well as references to names that Adorno cut from the articles.(21) I would recommend reading these lectures before the corresponding articles.

[16] The editors’ meticulous transcriptions and annotations of Adorno’s talks in Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen are an impressive scholarly achievement and an invaluable addition to the Adorno literature. One would hope that an English edition of the volume might become available before long, perhaps accompanied by transcriptions of those of Adorno’s illustrations at the piano that go beyond what we can find in the printed scores—such as when, to the audience’s delight, he turns a passage from a Schoenberg song into a Wagnerian sequence (DVD, track 1, 1:28:00).

Christoph Neidhöfer

Schulich School of Music

McGill University

555 Sherbrooke Street West

Montreal, QC H3A 1E3

christoph.neidhofer@mcgill.ca

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. (1949) 2006. Philosophy of New Music, ed. and trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. University of Minnesota Press.

—————. (1954/55) 2002. “The Aging of the New Music,” trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor and Frederic Will. In Essays on Music, ed. Richard Leppert, 181–202. University of California Press.

—————. (1957) 1978. “Die Funktion des Kontrapunkts in der neuen Musik.” In Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 16, ed. Rolf Tiedemann with Gretel Adorno, Susan Buck-Morss, and Klaus Schultz, 145–69. Suhrkamp.

—————. (1957) 1999. “The Function of Counterpoint in New Music.” In Sound Figures, trans. Rodney Livingstone, 123–44. Stanford University Press.

—————. 1958. “Kriterien.” Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik 1: 7–16.

—————. (1958) 1978. “Musik und Technik.” In Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 16, ed. Rolf Tiedemann with Gretel Adorno, Susan Buck-Morss, and Klaus Schultz, 229–48. Suhrkamp.

—————. (1959) 1978. “Kriterien der neuen Musik.” In Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 16, ed. Rolf Tiedemann with Gretel Adorno, Susan Buck-Morss, and Klaus Schultz, 170–228. Suhrkamp.

—————. (1959) 1999. “Criteria of New Music.” In Sound Figures, trans. Rodney Livingstone, 145–96. Stanford University Press.

—————. (1960) 1992. Mahler. A Musical Physiognomy, trans. Edmund Jephcott. University of Chicago Press.

—————. (1960/61) 1998. “Mahler.” In Quasi una Fantasia. Essays on Modern Music, trans. Rodney Livingstone, 81–110. Verso.

—————. 1962. “Vers une musique informelle.” Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik 4: 73–102.

—————. (1963) 1978. “Vers une musique informelle.” In Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 16, ed. Rolf Tiedemann with Gretel Adorno, Susan Buck-Morss, and Klaus Schultz, 493–540. Suhrkamp.

—————. (1963) 1998. “Vers une musique informelle.” In Quasi una Fantasia. Essays on Modern Music, trans. Rodney Livingstone, 269–322. Verso.

—————. (1966) 1978. “Form in der neuen Musik.” In Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 16, ed. Rolf Tiedemann with Gretel Adorno, Susan Buck-Morss, and Klaus Schultz, 607–27. Suhrkamp.

—————. (1966) 2008. “Form in the New Music,” trans. Rodney Livingstone. Music Analysis 27 (2–3): 201–16.

—————. (1968) 1991. Alban Berg. Master of the Smallest Link, trans. Juliane Brand and Christopher Hailey. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 1999. “Funktion der Farbe in der Musik (1966).” In Darmstadt-Dokumente I (Musik-Konzepte Sonderband), ed. Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn, 263–312. edition text+kritik.

—————. 2002. “On the Problem of Musical Analysis,” trans. Max Paddison. In Essays on Music, ed. Richard Leppert, 162–80. University of California Press.

Borio, Gianmario. 1993. Musikalische Avantgarde um 1960. Entwurf einer Theorie der informellen Musik. Laaber.

—————. 2015. Review of Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen, by Theodor W. Adorno, ed. Klaus Reichert and Michael Schwarz. Twentieth-Century Music 12 (2): 261–68.

Borio, Gianmario, and Hermann Danuser, eds. 1997. “Chronik der Ferienkurse.” In Im Zenit der Moderne. Die Internationalen Ferienkurse für Neue Musik Darmstadt 1946–1966, with Pascal Decroupet, Inge Kovács, Andreas Meyer, and Wilhelm Schlüter, vol. 3, 513–638. Rombach Verlag.

Boulez, Pierre. (1952) 1991. “Schoenberg is Dead.” In Stocktakings from an Apprenticeship, collected by Paule Thévenin, trans. Stephen Walsh, 209–14. Clarendon Press.

Holtmeier, Ludwig. 2009. “Analyzing Adorno—Adorno Analyzing.” In Musiktheorie an ihren Grenzen: Neue und Alte Musik, ed. Angelika Moths, Markus Jans, John MacKeown, and Balz Trümpy, 69–84. Peter Lang.

Holtmeier, Ludwig, and Cosima Linke. 2011. “Schönberg und die Folgen.” In Adorno-Handbuch. Leben—Werk—Wirkung, ed. Richard Klein, Johann Kreuzer, and Stefan Müller-Doohm, 119–39. J. B. Metzler.

Metzger, Heinz-Klaus. (1958) 1960. “Intermezzo I (Just Who is Growing Old?).” Die Reihe 4: 63–80.

Tiedemann, Rolf. 2001. “Nur ein Gast in der Tafelrunde. Adorno in Kranichstein und Darmstadt 1950–1966.” Frankfurter Adorno Blätter 7: 177–86.

Vande Moortele, Steven. 2015. “The Philosopher as Theorist: Adorno’s materiale Formenlehre.” In Formal Functions in Perspective. Essays on Musical Form from Haydn to Adorno, ed. Steven Vande Moortele, Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers, and Nathan John Martin, 411–33. University of Rochester Press.

Footnotes

1. Adorno appeared at the Darmstadt summer courses in other years as well: in 1950, the year after he returned from exile, and in 1951, he served on the faculty teaching courses in music criticism (“Musikkritik”) and “free composition” (“Arbeitsgemeinschaft für freie Komposition”), respectively. In 1951 he also gave a talk on Webern at the Second International Twelve-Tone Congress that took place during the summer courses, as well as a talk on “Music, Technology, and Society” (“Musik, Technik und Gesellschaft,” incorporated in Adorno [1958] 1978). In 1954 he taught a course together with violinist Rudolf Kolisch and pianist and composer Eduard Steuermann on new music and performance (“Neue Musik und Interpretation [mit musikalischen Demonstrationen]”), and in 1965 he opened the Darmstadt festival with a lecture on “Form in New Music” (“Form in der Neuen Musik”), first published in the following year (Adorno [1966] 1978, English translation in Adorno [1966] 2008). These single lectures are not included in Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen. The programs of the Darmstadt courses of 1946–66 are listed in Borio and Danuser 1997.

Return to text

2. The most incisive contemporary critique of Adorno’s article is Metzger [1958] 1960.

Return to text

3. “Also, ich möchte schon versuchen, gerade die jungen Komponisten, die Zwölftonkomponisten dazu zu bringen, in gewisser Weise in ihrem eigenen Verfahren selbstkritischer zu werden, indem Sie das, was Sie tun, messen an dem unbeschreiblichen Reichtum und der unbeschreiblichen Substanz, die bei dem jungen Schönberg sich eben findet und die, ja, die die Folie ist oder die die Bedingung ist dann auch für die Askese, für alle die Refus, die Schönberg dann später vollzogen hat.” All English translations here of passages from Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen are mine. Adorno repeatedly invokes Paul Valéry’s concept of “refus,” whereby “the quality of a work of art essentially measures itself by its refusals, that is, by the things which it renounces” (“daß die Qualität eines Kunstwerks sich wesentlich mißt an seinen Refus, also an den Dingen, auf die es verzichtet,” 100; see also 579, footnote 52). In his lecture notes, Adorno writes: “Reference to what Sch[oenberg] sacrificed: the greatest and purest of the New German School composers gives up all his discoveries, the perfect points beyond itself. Only that this abundance and articulated language of form [in Gurrelieder] are given and preserved then lends all that came later its substantiality.” (“Hinweis auf das, was Sch geopfert hat: der größte und lauterste der neudeutschen Komponisten gibt alle seine Funde auf, das Vollkommene weist über sich hinaus. Nur daß diese Fülle und artikulierte Formsprache [in Gurrelieder] vorgegeben ist und aufbewahrt wird, verleiht allem Späteren dann seine Substantialität,” 546.)

Return to text

4. For an analysis and critique of Adorno’s concept of “informal music,” see Borio 1993, particularly 102–18 and 168–73.

Return to text

5. “Mit anderen Worten also, der Akkord ist in Wirklichkeit bereits ein quartiger Akkord, und er wäre am allereinfachsten zu erklären: [Example 5] als eine Alteration dieses Quartenakkords nach oben” (28).

Return to text

6. The issue of “historical tendencies” is complex, however, as Adorno explains in the context of the “problem of historicism” in the 1957 lectures (254–55).

Return to text

7. Adorno tends to praise composers who can do without sequences, such as when he speaks of Mahler’s “critical vigilance against empty formality like that of Bruckner’s sequences” (Adorno [1960] 1992, 67).

Return to text

8. “Bei ‘Etwas belebter’ auf Seite 10 kommt ein neues, ein ganz neues Motiv, das allerdings verwandt ist mit dem ersten Hauptthema” (52). As the page reference here suggests, Adorno likely played his examples directly from the full score. Gianmario Borio, in his review of Kranichsteiner Vorlesungen, points out an example of Adorno using “axial rotation” to mean, in the terminology of post-tonal theory, a transposed permutation of an ordered pitch-class set (Borio 2015, 264).

Return to text

9. “Wobei ich sagen würde: Es entspricht sich [Example 11, first motive] und nun das [Example 11, second motive]. Das [D4] und das [C4] entspricht sich, das [

Return to text

10. “Since the music has been composed from the bottom up, it must be heard from the bottom up” (Adorno [1960/61] 1998, 87).

Return to text

11. In his monograph on Berg, Adorno likewise emphasizes the need to analyze a work in both directions, from its totality to its details and vice versa: “In a compositional process in reverse, as it were, beginning with the end product, it is necessary to determine the objective properties of a composition’s quality by immersing oneself in the work as a whole and its microstructure” (Adorno [1968] 1991, 35).

Return to text

12. For a recent discussion of Adorno’s “material theory of form,” see Vande Moortele 2015. On Adorno’s analytical practice and its background, see Holtmeier 2009 and Holtmeier and Linke 2011.

Return to text

13. “[

Return to text

14. “[

Return to text

15. “Es ist ein Unterschied, ob man etwas vergißt, einfach weil man’s halt vergißt, oder ob man etwas vergißt aus kritischer Reflexion.”

Return to text

16. “[

Return to text

17. “Wie kann ich frei und doch verbindlich kontrapunktieren?”

Return to text

18. “[

Return to text

19. “Die Kontrapunktik erfüllt hier die ganz spezifische formale Funktion, die Abstraktheit oder Langeweile der Wiederholung zu vermeiden und trotzdem die Dichte innerhalb der Beziehungen der thematischen Bestandteile herzustellen, die in der traditionellen Musik nur durch die abstrakte Wiederholung der einander entsprechenden Formteile eigentlich erst hergestellt werden können.”

Return to text

20. “[

Return to text

21. Space does not allow me to illustrate this here, but interested readers may want to compare the following passages, for instance: 144–46 with Adorno [1957] 1978, 166 (on the problem of twelve-tone counterpoint); 334 with Adorno [1959] 1978, 206 (where readers of the article are purposely left in the dark as to whose string quartet Adorno is talking about—the lecture identifies it as that of Hans Erich Apostel); 311 with Adorno [1959] 1978, 196–97 (explanation of “[qualitative] level of form” [“Formniveau”]); and 437 with Adorno [1963] 1978, 504 (Adorno names the serial composer he is criticizing, Karel Goeyvaerts, in the lecture but not in the article). Occasionally, however, Adorno worked additional details into an article version, as in his discussion of technical features of Wozzeck (compare 370 with Adorno [1959] 1978, 220).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Sam Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

6303