Review of Massimiliano Guido, ed., Studies in Historical Improvisation from Cantare super Librum to Partimenti (Ashgate, 2017)

Gilad Rabinovitch

KEYWORDS: historical improvisation, sixteenth-century music, seventeenth-century music, eighteenth-century music, counterpoint, partimenti, figured bass, musicianship, pedagogy

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

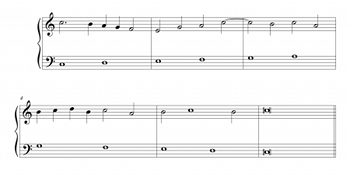

Example 1. Realization of partimento Gj 92 by Francesco Durante, mm. 1–8

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Canon module (after Froebe 2007, 35) adapted to match Durante’s context

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[1] The study of contrapuntal patterns and their diminutions was a common thread among historical music pedagogies. Medieval and Renaissance musicians learned counterpoint by memorizing intervallic combinations and internalizing surface patterns (Busse Berger 2005). The partimento “rules,” or patterns, of the eighteenth century (such as Francesco Durante’s “when the partimento ascends by half step, it takes the 6th”) were comparable to the formulas of the Klangschrittlehre tradition (Sachs 1971).(1) By providing an incipit for realizing the partimento Gj. 92 (Example 1), Durante tacitly taught a canon module (Example 2) associated with the long-standing tradition of improvised vocal counterpoint (surveyed in Froebe 2007). My realization continues the canon and responds to the ensuing bass patterns using Durante’s rules for realization. Thus, interrelationships among figured bass, contrapuntal skeletons, and diminution techniques pervaded centuries of musicianship pedagogy in Europe.

[2] Massimiliano Guido’s edited collection explores improvisational traditions and techniques from 1500 to 1750. Readers interested in historical improvisation from a theoretical, historical, or pedagogical point of view will benefit from the rich and concise case studies in this volume. Guido’s introduction explains the reciprocal relationship between scholarship and performance: historical teachings help us to reconstruct improvisatory practices, and improvisation nowadays enriches our understanding of the sources. It is therefore significant that several of the contributors are actively involved in reviving improvisatory traditions as performer-scholars. The collection, which stems from a 2013 conference in Venice, is in four parts, which deal with the art of musical memory, improvising vocal music, improvising keyboard music, and present-day pedagogy.

[3] Thomas Christensen’s essay, “The Improvisatory Moment,” reflects on the momentum of current improvisation studies—not only in historical improvisation, but also in jazz scholarship, music cognition, and ethnomusicology. He attributes this surge to the digital accessibility of recordings of improvised musics, as well as to the growing skepticism toward the work concept and the notated score—a skepticism that emanates from the writings of Carl Dahlhaus, Lydia Goehr, and Richard Taruskin. Christensen notes that improvisation research allows us (1) to recognize commonalities among improvised traditions; (2) to distinguish varieties of improvisation, stressing the multiplicity of regional dialects in Europe; (3) to recognize the central place of improvisation in studying and teaching Western music history, and reconsider periodization as a result;(2) and (4) to reform the pedagogy of music theory by incorporating improvisation. Reacting to the controversial manifesto of the College Music Society Task Force (Sarath et al. 2014), which calls for increased creativity and de-emphasis of the Western canon in collegiate music curricula, Christensen stresses that the improvisatory nature of European music in past eras makes distinctions between Western art music and other musical cultures “specious” (24).(3) Indeed, it is difficult to predict whether our twenty-first-century students will choose to perform or study historical European repertoires, hip-hop, gamelan, electronic music, or other traditions. Yet one would hope that they do so with the level of artistic and scholarly commitment necessary for reconstructing historical improvisation, and with the understanding that the predominantly dead-white-male periods in European music history do not represent exceptionalism in relation to other musics.

[4] Stefano Lorenzetti discusses contrapuntal commonplaces, focusing mainly on two treatises—Chiodino’s Arte pratica (1610) and Banchieri’s Cartella musicale ([1614] 1968)—along lines related to Peter Schubert’s 2010 study of commonplaces in the Renaissance. Both treatises provide mnemonic storehouses of contrapuntal combinations and diminution formulas, akin to rhetorical commonplaces that can be incorporated at an appropriate place in an oration. Banchieri states that he did not cite the authors of the one hundred passaggi to be memorized, since, in Lorenzetti’s words, “as loci communes, they are part of a collective memory socially ratified, that nourishes the inventio” (38). This is in line with the Erasmian notion of attaining individuality by drawing on models and fragmenting them. Lorenzetti’s chapter thus connects to the broad theme of creating a memorized storehouse of patterns to be used in creating music. The idea that individuality is achieved through employing models is at tension with romantic-modernist ideals of creativity and fits well with present-day skepticism toward the musical work of art.

Example 3. Reproduction of Guido’s Figure 3.1 (p. 47) and Example 3.1a (p. 49), which show two lines from Girolamo Diruta’s alio modo

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 4. Reproduction of Guido’s Example 3.1c (p. 49), which combines materials from the lines reproduced in Example 3 and additional ones

(click to enlarge)

[5] Guido starts his own chapter on memory by relating Diruta’s emphasis on hand positions and patterns (in Il Transilvano) to modern-day views of embodiment and procedural memory. He then discusses Diruta’s alio modo exemplars for diminutions against a hexachord and explores their combinatorial potential. Each of Diruta’s lines (Example 3) features consistent rhythmic figuration, whereas Guido’s adaptation (Example 4) combines segments from different original lines, demonstrating one creative way to engage with this source at the keyboard. Guido discusses the challenges facing today’s teachers of historical improvisation: adult learners of this “advanced” topic have less time to practice than historical students of counterpoint had. Moreover, we rely excessively on gadgetry rather than on memory. Finally, we live in a stylistically diverse musical environment compared with the relatively homogeneous environments in past eras.

[6] The contrast between the stylistic homogeneity of the past and the heterogeneity of the present could be stated in even stronger terms. Stylistic diversity fundamentally challenges today’s historical improvisers as well as their listeners. In one sense, the availability of a huge amount of material online—scores, treatises, recordings—could facilitate stylistic immersion with an efficiency never available before. Yet many modern-day listeners are not enculturated in early music styles; they use their technology to immerse themselves in other musical idioms. (This is, of course, just an observation, not a value judgment.(4)) Historical improvisation is thus a field with relatively few expert practitioners and enculturated listeners, unlike living improvisatory traditions that often involve audience feedback during the performance.(5) The audience’s reaction to Catherine Motuz’s and Rona Nadler’s impressive historical improvisation—to be discussed below—might be attributable to an outsider’s astonishment that such a musical feat could be pulled off at all, rather than to a deep implicit or explicit understanding of the underlying musical grammar.

[7] Philippe Canguilhem explores the practice of cantare super librum, which was prevalent throughout Europe from the fifteenth through the eighteenth century and elicited both positive and negative appraisals from authors of that time. He surveys examples of improvised counterpoint in theoretical treatises and identifies features that indicate that a composition is likely to be a written-out improvisation: a regularly metered cantus firmus in plainchant notation, certain liturgical functions (especially Introit and Alleluia movements), and no attributed author. He analyzes several examples of presumed improvised polyphony, culminating in an impressive Alleluia by Ghiselin Danckerts that “can give us an idea of the way papal singers were improvising toward the middle of the sixteenth century” (68).(6)

[8] Giuseppe Fiorentino’s contribution surveys learned and popular traditions of improvised polyphony in Spain during the Renaissance. In order to assess the level of training in improvised genres, he examines the curricula in Spanish cathedrals, which included training in performing plainchant (canto llano), written polyphonic music (canto de órgano), and improvised counterpoint (contrapunto). He provides notated examples of relatively easy and schematic improvisations in three voices from treatises by Lusitano (1553) and Aranda (1535). Fiorentino contrasts the learned style with the simpler fabordón, which could be extemporized by ear without rigorous training. Both Canguilhem’s and Fiorentino’s contributions are of a historical nature; readers with a more practical bent might jump ahead to Haymoz’s report on his experience with improvised vocal genres. Yet written-out improvisatory sources in any period—written treatises, partimenti, embellishments of Corelli’s sonatas, or cadenzas notated by W. A. Mozart—are keys for reconstructing historical improvisation. Even if such demonstrations are idealized portraits of reality—reflecting the unique abilities of a few elite experts—such sources might be the closest approximations of improvisations from the past.

Example 5. Reproduction of Haymoz’s Example 6.11 (p. 105), a transcription by Jacques Meegens of a 2005 improvisaion by Haymoz’s group

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[9] In his delightful chapter, Jean-Yves Haymoz recounts his experience of reconstructing improvised polyphony in genres including fauxbourdon, frottola, and canons. Constraining the choice of principal consonances for each voice to a “zone” of consonances with a cantus firmus (e.g., tenths and twelfths) makes it possible to add three or even four improvised voices. Example 5 shows a transcription of a five-voice improvisation by Haymoz’s group, a “work-in-progress” from 2005 when the group was starting to develop this technique; the group has since adopted more hand cues to clarify the bass singer’s intentions and avoid confusion such as what took place in m. 6. (The bass determines which contrapuntal combinations are possible with the referential cantus firmus in the tenor.) I find this chapter a most vivid demonstration of the necessary trial and error involved in reconstructing historical improvisation. A translation of Barnabé Janin’s (2014) didactic guide for this practice would be an excellent complement to Haymoz’s chapter, as it would allow performers and musicianship instructors to implement at least some of these techniques.

[10] Edoardo Bellotti discusses counterpoint and composition at the keyboard as taught in Banchieri’s Organo suonarino (1605–38) and Conclusioni nel suono dell’organo ([1609] 1981), and in Spiridion’s Nova Instructio (Spiridionis). He analyzes Banchieri’s use of clef changes and shorthand notation as one precursor to partimenti, alongside the versetti of Bernardo Pasquini and Bernardo Ricordati.(7) He shows how the memorization of stereotyped contrapuntal formulas (or schemata) permits their application in response to shorthand notations. Bellotti illuminates some hidden threads connecting counterpoint with figured and unfigured bass in the seventeenth century, which has been uncharted territory for many of us in our scholarship and teaching. He claims that modern-day curricula place too much emphasis on the “late Baroque” (i.e., early galant) for thoroughbass and inappropriately separate the study of counterpoint from “composing at the keyboard.” I agree with Bellotti’s appeal for multimodal and integrated learning from models: improvisation emulating any style can develop musicianship skills far beyond the written work normally required in college-level settings.

[11] Peter van Tour challenges the ordering of Durante’s partimenti used inter alia in Gjerdingen’s online edition (2005), which follows the nineteenth-century categorization: regole (i.e., basic “rules” or, more aptly, patterns), numerati (i.e., partimenti with figures), diminuiti (i.e., partimenti with guides to realizing their beginnings), and fugues. Based on extant eighteenth-century sources, van Tour reconstructs Durante’s two-stage training course: rules leading to the realization of figured partimenti, and then a more advanced study of sequential bass motions (moti del basso) leading to unfigured partimenti. He claims that the fugues are spurious. Van Tour also considers the recently discovered Gallipoli Manuscript, which includes 46 eighteenth-century realizations of advanced partimenti. As I eagerly anticipate receiving his edition, the samples provided in this chapter offer a glimpse of the importance of extravagant and varied keyboard diminutions in the late stages of partimento study.(8) Van Tour (2015) has already emphasized the role of written counterpoint alongside keyboard exercises in Neapolitan training; the present chapter reconstructs pedagogical scaffoldings for some of the more challenging partimenti, and demonstrates once again how philological debates are directly relevant to practical aspects of teaching historical improvisation.

[12] Giorgio Sanguinetti examines incomplete notations in partimenti and in Mozart’s piano concertos. Like van Tour, he stresses the role of diminutions in advanced stages of partimento study. He realizes Giacomo Tritto’s Lezzione 18 from his Partimenti e regole generali (1816), transforming the one-line notation into an idiomatic keyboard-sonata texture. Sanguinetti suggests that partimento training could be an antidote to modern-day training that emphasizes verbatim performances of musical scores. The dilemma of incomplete notations in Mozart’s keyboard concertos serves as an example: the notations sometimes appear to be missing details, yet adding notes raises the fear of “desecrating” Mozart’s text. Sanguinetti cites (160–61) Eva Badura Skoda’s (1996) reflections on the difficulty of acquiring a feeling for the fine details of Mozart’s style, which once again raises the issue of present-day stylistic heterogeneity.

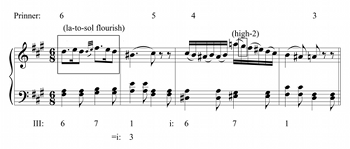

Example 6a. Recomposition of Mozart K. 488, 2nd movement, mm. 5–8

(click to enlarge)

Example 6b. Original version of Mozart K. 488, 2nd movement, mm. 5–8, with analysis of galant schemata

(click to enlarge)

[13] Keyboard diminutions and formulas are important threads connecting the historical teachings surveyed by Bellotti, van Tour, and Sanguinetti. Such teachings suggest types of musicianship that are virtually absent in today's mainstream “classical” training. The keyboard diminutions in period partimento realizations may seem to us simple in comparison with written-counterpoint exercises modeling, say, a Bach-style chorale-prelude—perhaps revealing our acquired Germanic biases—but partimento training led to extraordinary stylistic fluency in composition and improvisation. Moreover, the study of partimenti as well as galant schemata (as in Gjerdingen 2007) can also help us to acquire a feeling for Mozart’s High Classical bebop, as it were, in relation to earlier galant norms. For instance, if we regard mm. 5–8 of K. 488, movement 2, as derived from the interaction between the Prinner-riposte and Commas (i.e., segments of some version of the Rule of the Octave), we can view both the conventionality and the artifice of the original passage; see the recomposition in Example 6a. Mozart’s version (Example 6b) elaborates stock patterns in an ornate way, using the core galant tones as a focal thread. Gjerdingen’s Prinner-riposte offers a unique view of this passage through the galant conventions that preceded the High Classical style. Indeed, the High- Drop and the la-to-sol flourish—that is, subsidiary features associated with the Prinner’s core tones (Gjerdingen and Bourne 2015, 5.3.8–5.3.10)—allow us to understand highly conventional aspects of this fantastic achievement of Mozart’s musicianship. Though I have “desecrated” this sophisticated passage in a simplified recomposition—which, moreover, forsakes the idiomatic High- Drop—I believe that explorations at the intersection of scholarship, composition, and improvisation offer a path toward style-specific knowledge.(9)

Example 7. Transcription of an improvisation performed in 2014 by Catherine Motuz and Rona Nadler

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[14] In “Teaching theory through improvisation,” Peter Schubert reflects on a 2014 workshop at McGill University in which he taught students to improvise contraponto fugato—“placing a chosen short motive (called a passo) repeatedly against a cantus firmus (CF), filling in between the placements with free counterpoint” (176). Drawing on his experience teaching theory and musicianship in a regular academic setting, Schubert’s historically informed pedagogy combines embodiment, visualization, intuition, hearing, immediate feedback, and memory as the student imagines an acceptable next note. Schubert compares the implicit learning process to video games like “Candy Crush Saga,” and provocatively likens conventional theory pedagogy to a hypothetical video-game textbook. He thus revisits the issue of thinking in music as opposed to thinking about music (Schubert 2011, Graybill 2014). My transcription of Catherine Motuz and Rona Nadler’s “splendid” (183, fn. 18) improvisation from the 2014 workshop (Example 7) demonstrates the accomplishment of these musicians and the effectiveness of contraponto fugato pedagogy.(10) Improvising counterpoint in a live duo performance is a most rewarding contrast to written, rule-driven counterpoint assignments that lack participatory and aural engagement. Yet Motuz and Nadler’s improvisation also reveals some of the challenges of group improvisation. It might be advisable to use Haymoz’s technique of restricting each added line to a zone of consonances with the cantus firmus in order to avoid some of the problematic clashes and parallels that occur here—such as in m. 9, where the two added lines begin with the same motive in octaves, and in mm. 31–32, where the added sackbut line creates parallel octaves with the given cantus. One should bear in mind, of course, that these outstanding and pioneering musicians are involved in reviving traditions that had lain dormant for a very long time.

[15] Michael Callahan has written previously (2015) about incorporating keyboard improvisation into collegiate music theory pedagogy through electronic submission of audio clips. In this volume, he focuses on a graduate course in counterpoint, in which improvisational exercises introduce techniques to be explored later in more elaborate written exercises. The keyboard activities include basic partimento patterns, partial realizations of partimenti, and exemplars of diminutions inspired by Spiridion and Durante. Two-voice keyboard exercises explore polyphonic melody while keeping the activities manageable for non-pianists. The results here and in Callahan 2015 are particularly impressive given that his students are neither members of the historical-improvisation sect nor expert pianists; they demonstrate how arcane pedagogy and twenty-first-century technology combine to support the acquisition of musicianship skills.

[16] The rich panorama of historical techniques and traditions illuminated by Guido’s collection will be of interest to scholars, instructors, and practitioners alike. Indeed, it is the counterpoint among philological work, active music-making, and old teaching made new that generates such insight; the treatment of these traditions under one cover highlights connections between scholarship and practice on the one hand, and among different styles within the book’s chronological window (1500–1750) on the other hand. The collection’s biggest drawback is that it was published after detailed scholarship on some of these techniques and traditions had already existed, but this is mitigated by its new revelations, reflections, and points of convergence. The collection demonstrates that the project of historical improvisation can indeed succeed through the ongoing collective efforts of, and the dialogues between, scholars and practitioners.

[17] The study of historical improvisation—and of improvisation in general—has significant potential implications for teaching theory and musicianship. While the balance between analysis and creative work (such as model composition and improvisation) ought to depend on the desired learning outcomes, the assumption that explicit knowledge of harmony is a prerequisite for composition or improvisation (Marvin 2012, 258) is fundamentally at odds with the position that thinking in music should precede thinking about music (Schubert 2011). This dilemma merits further investigation, perhaps through empirical studies. It might be that many modern-day learners need explicit instruction in harmony and form before setting out to compose or improvise a minuet, for example, yet such instruction is at most a necessary but insufficient condition for stylistic fluency. An idiomatic knowledge of surface diminutions, underlying skeletons, and formal organization requires absorption of a host of exemplars, not just textbook formulations (Gjerdingen and Bourne 2015). Once again, the work of Callahan’s (2015) students leaves room for both optimism and further evaluation of the benefits and challenges of incorporating improvisation into general theory and musicianship curricula—that is, even without the specialized motivation of reconstructing historical improvisation.

[18] Historical pedagogies of improvisation also reveal new vantage points on music analysis by relating musical structure to teaching and learning. They permit us to explain the extravagant musical utterances of Monteverdi’s Orfeo in terms of a skeletal intervallic technique (Menke 2014, 75–76), and to reverse-engineer a Bach prelude using partimento models (Sanguinetti 2012, 342–46). By reconstructing improvisational methods of the past, we clarify the connections between how musicians were trained and what they created in a host of European styles.

Gilad Rabinovitch

Georgia State University School of Music

75 Poplar St., 5th floor

Atlanta, GA 30303

grabinovitch@gsu.edu

Works Cited

Aranda, Matheo de. 1535. Tractado de canto mensurable y contrapuncto. Galharde.

Badura-Skoda, Eva. 1996. “On Improvised Embellishments and Cadenzas in Mozart’s Piano Concertos.” In Mozart’s Piano Concertos: Text, Context, Interpretation, ed. Neal Zaslaw, 365–71. University of Michigan Press.

Banchieri, Adriano. 1605–38. L’organo suonarino. Ricciardo Amadino.

—————. (1609) 1981. Conclusioni nel suono dell’organo. Forni.

—————. (1614) 1968. Cartella musicale nel canto figurato, fermo & contrapunto. Forni.

Bourne, Janet. 2017. “Beethoven’s Middle Earth: Hearing Film Music Topics in Music of the Long Eighteenth Century.” Presentation at the Annual Meeting of Music Theory Southeast, Fort Myers, FL, March 4.

Busse Berger, Anna Maria. 2005. Medieval Music and the Art of Memory. University of California Press.

Byros, Vasili. 2015. “Prelude on a Partimento: Invention in the Compositional Pedagogy of the German States in the Time of J. S. Bach.” Music Theory Online 21 (3).

Callahan, Michael R. 2015. “Teaching and Learning Undergraduate Music Theory at the Keyboard: Challenges, Solutions, and Impacts.” Music Theory Online 21 (3).

Chiodino, Giovanni Battista. 1610. Arte pratica latina et volgare di far contrapunto à mente, & à penna. Ricciardo Amadino.

Christensen, Thomas. 2008. “Fundamenta Partiturae: Thorough Bass and Foundations of Eighteenth-Century Composition Pedagogy.” In The Century of Bach and Mozart: Perspectives on Historiography, Composition, Theory, and Performance, ed. Thomas F. Kelly and Sean Gallagher, 17–40. Harvard University Press.

Diruta, Girolamo. 1593–1625. Il Transilvano. Vincenti.

Froebe, Folker. 2007. “Satzmodelle des ‘Contrapunto alla mente’ und ihre Bedeutung für den Stilwandel um 1600.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 4: 13–55.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. 2005. Monuments of Partimenti. http://faculty-web.at.northwestern.edu/music/gjerdingen/partimenti/index.htm

—————. 2007. Music in the Galant Style. Oxford University Press.

Gjerdingen, Robert O., and Janet Bourne. 2015. “Schema Theory as a Construction Grammar.” Music Theory Online 21 (2).

Gjerdingen, Robert O., and David Perrott. 2008. “Scanning the Dial: The Rapid Recognition of Music Genres.” Journal of New Music Research 37 (2): 93–100.

Graybill, Roger. 2014. “Thinking ‘in’ and ‘about’ Music: Implications for the Theory Curriculum.” Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy 2. http://flipcamp.org/engagingstudents2/essays/graybill.html.

HaCohen, Ruth, and Naphtali Wagner. 1997. “The Communicative Force of Wagner’s Leitmotifs: Complementary Relationships between their Connotations and Denotations.” Music Perception 14 (4): 445–75.

Janin, Barnabé. 2014. Chanter sur le livre: manuel pratique d’improvisation polyphonique de la Renaissance: XVe et XVIe siècles. 2nd ed. Symétrie.

Lusitano, Vicente. 1553. Introdutione facilissima, & novissima, di canto fermo, figurato, contraponto semplice, & inconcerto. Antonio Blado.

Marvin, Elizabeth West. 2012. “The Core Curricula in Music Theory: Developments and Pedagogical Trends.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 26: 255–63.

Menke, Johannes. 2014. “‘Ex centro’ Improvisation: Sketches for a Theory of Sound Progressions in the Early Baroque.” In Improvising Early Music: The History of Musical Improvisation from the Late Middle Ages to the Early Baroque—Volume 11 of Collected Writings of the Orpheus Institute, ed. Dirk Moelants, 69–91. Leuven University Press.

Racy, Ali Jihad. 1998. “Improvisation, Ecstasy, and Performance Dynamics in Arabic Music.” In In the Course of Performance: Studies in the World of Musical Improvisation, ed. Bruno Nettl with Melinda Russell, 95–112. The University of Chicago Press.

Sachs, Klaus-Jürgen. 1971. “Zur Tradition der Klangschritt-Lehre. Die Texte mit der Formel ‘Si cantus ascendit

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. 2012. The Art of Partimento: History, Theory, and Practice. Oxford University Press.

Sarath, Ed, David Myers, Juan Chattah, Lee Higgins, Victoria Lindsay Levine, David Rudge, and Timothy Rice. 2014. “Transforming Music Study from its Foundations: A Manifesto for Progressive Change in the Undergraduate Preparation of Music Majors.” Report of the Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major, College Music Society.

Schubert, Peter. 2010. “Musical Commonplaces in the Renaissance.” In Musical Education in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, ed. Russell E. Murray, Jr., Susan Forscher Weiss, and Cynthia J. Cyrus, 161–92. Indiana University Press.

—————. 2011. “Thinking in Music.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 25: 217–33.

Spiridionis a Monte Carmelo. (1670–77) 2003–5, 2008. Nova Instructio pro pulsandis organis spinettis manuchordiis &c., ed. Edoardo Bellotti. Andromeda.

Tritto, Giacomo. 1816. Partimenti e regole generali. Artaria.

van Tour, Peter. 2015. Counterpoint and Partimento: Methods of Teaching Composition in Late Eighteenth-Century Naples. Uppsala Universitet.

Webster, James. 2004. “The Eighteenth Century as a Music-Historical Period?” Eighteenth-Century Music 1 (1): 47–60.

Wegman, Rob. 2014. “What is Counterpoint?” In Improvising Early Music: The History of Musical Improvisation from the Late Middle Ages to the Early Baroque—Volume 11 of Collected Writings of the Orpheus Institute, ed. Dirk Moelants, 9–68. Leuven University Press.

Footnotes

1. The Durante passage is translated in Gjerdingen 2005. See also Gjerdingen’s remarks (2007, 45) on the relationship between Prinner’s figured-bass manual and the tradition of describing contrapuntal motions with respect to a referential voice (cf. Christensen 2008).

Return to text

2. Christensen mentions that the improvisatory partimento tradition supports the stylistic unity of the eighteenth century (see also Webster 2004), and that improvised counterpoint challenges the stylistic watershed around 1600 due to the persistence of contrapuntal modules (as described in Froebe 2007).

Return to text

3. To be fair, the manifesto’s authors allude to the exemplary improvisatory ability of past European masters and even view it as a model for emulation. They write: “Were Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt alive today, their musical lives would likely more closely resemble those of today’s creative jazz artists and other improvisers-composers-performers than interpretive performance specialists whose primary focus is repertory created in, and for, another time and place” (Sarath et al. 2014, 12).

Return to text

4. Our modern-day ears affect our listening to both “structure” and “meaning.” For instance, Janet Bourne (2017) discusses the ways in which topical associations from film music affect the meaning that might emerge in a modern-day listener’s mind, even when listening to classical music (see also HaCohen and Wagner 1997). Experimental participants (i.e., college students) might not have much experience with early music, but often possess a nuanced and automatic sense of (sub)genre in familiar popular musics (Gjerdingen and Perrott 2008).

Return to text

5. See, for instance, the discussion of an improviser’s communication with the audience in Racy 1998.

Return to text

6. See also Wegman’s discussion of notated improvisations with a regularly metered cantus firmus serving as an anchor, often in anonymous sources and with the cantus in chant notation (2014, 48–68). Wegman has found such sources “almost too good to be true” (2014, 50), suggesting that the transcription process involved tacit corrections.

Return to text

7. Van Tour mentions Rome as a link: Spiridion studied there and Bernardo Pasquini taught Georg Muffat and Francesco Durante there (146, fn. 35).

Return to text

8. See also Sanguinetti 2012, 226–32.

Return to text

9. See also Byros 2015.

Return to text

10. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3FIlwKx-OYQ.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Sam Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

8297