Stepping Out: Hearing Balanchine *

Gretchen G. Horlacher

KEYWORDS: Balanchine, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky, Serenade, Orpheus, ballet, choreography, music and dance

ABSTRACT: This paper explores relationships between musical and balletic structure in Balanchine’s choreographies of Tchaikovsky’s op. 48 Serenade and Stravinsky’s Orpheus. It demonstrates how movement in music (phrase shapes, melodic directions) and movement in ballet (in individuals and in the corps de ballet) may respond to one another, especially in how each art form follows and alters its own conventions.

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

PART ONE: SERENADE

Figure 1. Dancers at the rise of the curtain in Serenade

(click to enlarge)

[1.1] Audiences often take in a collective breath upon seeing the curtain rise at the opening of Balanchine’s ballet Serenade, given as Figure 1. Based on Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings, music the choreographer had loved since his childhood, the curtain rises to the formation given in the figure, with the corps de ballet spread across the stage in a striking formation. The curtain rises at the third phrase of music, after two iterations of opening music, and the third begins in the same way. But this time we see seventeen female dancers in five diagonal rows, and each dancer stretches one arm diagonally away from her body with her head turned toward some distant point beyond the stage.

Figure 2. Ruthanna Boris’s diagram of Serenade’s opening formation

(click to enlarge)

[1.2] The five rows, arranged symmetrically in a double diamond shape, fill the stage with diagonal lines. On each side of the stage two outer rows are formed by three members of the corps, whereas the center diagonal holds five. This beautiful configuration, which Balanchine said reminded him of southern California orange groves (Homans 2010, 518), is remarkable in how it features the ballet corps—the accompanying dancers—as central. Ruthanna Boris, one of the original corps members, created a summary diagram of the configuration, shown as Figure 2, describing its special features as follows: “no one was behind anyone else, each body had its own visible position and its own surrounding space. It was totally unlike any group placement I had ever seen—the usual a faceless set of straight lines dancing behind a soloist. Mr. George Balanchine was making lines where everyone could be seen!”(1) Serenade was the first ballet Balanchine made on his new American company, and he needed a dance that served as a pedagogical model for the style of ballet he wanted them to learn: in his words, he wanted “to teach them how to be on the stage.”(2)

[1.3] Strikingly, the dancers remain completely still during the Serenade’s third phrase. However, they are not simply occupying space, even the exquisite space given to them. These dancers are each poised to move. In fact, they seem already to have moved: their right arms have already gained an upward diagonal while their left arms are still tightly at their sides. Each dancer holds her body midstream, with heads gazing toward a point beyond them.(3) In their upper bodies they have already become dancers, as if they have been listening and responding to the first two phrases of music before the curtain has risen. At the same time, their feet are not yet those of dancers. Their toes are pointed forward, firmly rooted to the ground, not yet having assumed one of the classic positions. While they stand stock still, they—and we—listen to the music begin a third time, as if waiting for a sign telling their lower bodies “how to be on the stage.”

Example 1. Tchaikovsky’s op. 48 Serenade, I, introduction (bars 1–36)

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Linear sketches for Serenade’s opening four phrases

(click to enlarge)

[1.4] To what have they been listening? I will suggest that they have been listening to how Tchaikovsky’s repeating phrase falls. As shown in Example 1, the melody of this “Andante non troppo” tempo strides deliberately downward toward the tonic, although its descending stepwise movement is broken into two stages. Here it will be helpful to look at the voice-leading sketch in Example 2.(4) Across the entire phrase, outer voices move downward in stepwise parallel tenths, transformed in the second phrase (at system 2 of Example 2) into parallel sixths as outer parts are exchanged. Whether in the top or bass voice, however, the melody’s descent stops first on ˆ3, an arrival first weakened by its harmonization on vi. It then doubles back up to fall a second time, continuing its journey in parallel tenths or sixths to reach an authentic cadence. This double descent strongly implies a closure through the entire scale down to the tonic, a completion interrupted only at the last moment when D rises up to E. The melodic interruption constitutes a reason to repeat the entire phrase, and hence arise phrases two, three, and four (each displayed on succeeding systems of Example 2). Tightly and lushly scored, the melody impels us onward, and as the curtain rises to its third repetition, we experience the palpable tension of dancers’ bodies held still in midstream. When will they move? Will they all move? What will happen to the beautiful symmetry of the diamond?

[1.5] Moreover, the music has also begun midstream: like the dancers, whose upper bodies first appear in a partial pose, the musicians begin on vi, in the middle of an emerging C major key area. The return to vi in the middle of the phrase becomes a reminder of that stylized beginning. Even in the second phrase, when a complete octave descent takes place in the bass, omitting the tonicization of vi, melodic closure is still denied. As the phrase begins a third time (on system 3 of Example 2), once again on vi, and now with the dancers in full view, we, as well as they, are primed for movement: this third initiation is imbued with energy, even as the dancers remain still. Our sense of anticipation is high: we cannot take our eyes away from the stage as we listen for the third repetition of the phrase to unfold.

[1.6] And the third phrase does not disappoint. This time, as if the music is responding to the dancers’ perfect stillness, it too stops short. As shown on the third system of Example 2, a half cadence on the dominant of vi (at the exclamation mark) comes early, in the sixth bar of a phrase that has normally lasted eight bars. After this surprising turn, the third phrase must again re-begin, this time from the very beginning, as shown in the fourth system of Example 2.

Video Example 1. Serenade, New York City Ballet

(click to watch)

[1.7] Finally the dancers begin to move, first slowly and gracefully, bringing their right arms over their heads to the left sides of the body. But not long after, their arms quickly begin to descend as described by dance journalist Tom Phillips, “[s]uddenly, the wrist curves and circles overhead, then downward through the center line of the body, followed by [a] gaze; the arms form a ballet fifth position at the hips.”(5) The descending movement of the dancers’ arms, stopping first at the shoulder, marks and complements the music’s arrival on the surprise half cadence on vi: we await and anticipate a resolution both in music and in the dancers’ bodies. Throughout the rest of the introduction the music will remain on V of vi, and it is during this musical stillness that the dancers move their arms first into a low fifth position, snap their feet into first position, and in the final four bars of the prolonged half cadence, move their entire bodies at once, finally bringing their feet into the fundamental fifth position. The complementary changes in pacing of music and dance join them intimately. Each art form draws upon its fundamental vocabulary, be that moving by step through a scale in the music, or placing arms and legs into fifth position in the ballet. Video Example 1 shows the opening with the New York City Ballet; the introduction continues through 1:48.(6)

[1.8] Martha Graham, whose modern-dance choreographies are in many ways a critique of twentieth-century ballet, claims that tears filled her eyes when the dancers’ feet “snapped into first position.”(7) Now the dancers have fully learned “how to be on stage:” even their feet have reached completion, and now too they have cadenced. Now that they are truly ready to dance, to move away from their spots, the music too is ready to begin its proper first theme.

[1.9] This analysis invites us to hear Tchaikovsky’s music and Balanchine’s choreography as a partnership. Pairing music and ballet’s singular ways of moving and being still, it finds a neoclassical elegance in the way each art form is heard and seen in relation to the other. We have seen a descending melody enliven a tonic prolongation, with carefully aggregated bodies filling out the stage. The unbalance of their pose cries out for movement as the music re-begins with phrases and as phrases repeat. As the dancers finally begin to move, the music retraces its steps only to find a new harmonic goal, one whose elongation supports them as they too ready their bodies for the main body of Tchaikovsky’s movement.

PART II: “See the music, hear the dance”

Figure 3. Choreographer George Balanchine and composer Igor Stravinsky at rehearsal of New York City Ballet production of “Agon” (New York, 1957)

(click to enlarge)

[2.1] Balanchine the choreographer was also Balanchine the highly trained musician. He adored the music of Tchaikovsky from an early age. His education in St. Petersburg and experience with the Ballets Russes exposed him to new choreographies, and his collaboration with Stravinsky in the 1928 Apollo taught him how Modernist musicians were reconceiving time both as static and driven. Pioneering the plotless ballet while maintaining a deep connection with the classicism of Marius Petipa’s great Tchaikovsky choreographies, Balanchine had an uncanny ability to integrate physical and musical movement as he explored the boundaries of temporality.(8) Borrowing a quotation from essayist Glenway Wescott, he gladly proclaimed that we should “see the music, hear the dance.”(9) Stravinsky said something quite similar in the Poetics: “it was not enough to hear music, but that it must also be seen,” adding that “from this point of view one might conceive the process of performance as the creation of new values that call for the solution of problems similar to those which arise in the realm of choreography. In both cases we give special attention to the control of gestures.” (1970, 128)

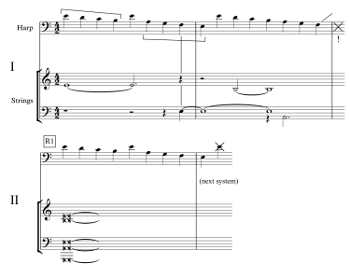

Example 3. Varied repetition in the opening of Stravinsky’s Orpheus

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.2] Balanchine’s stylistic gestures, such as limited, precise bodily movements, poses that expose the body, sudden changes in pace within the body, and the contrast of movement and stillness, all key features in the Serenade, became even more prominent in his collaboration with Stravinsky in the 1948 Orpheus.(10) While the music for Orpheus is familiar to musicians, the ballet received decidedly mixed reviews, due in part to its limited, non-virtuosic choreography.(11) Its opening is a case in point: for more than two minutes, Orpheus stands motionless with his back to the audience. Alastair Macaulay has written that the silent beginning is a hallmark for Balanchine: “Most Balanchine ballets begin with a tableau, as if movement had been interrupted. When movement does begin, it’s usually timed to take you by surprise,”(Macaulay 2016) an observation confirmed abundantly in key moments of this ballet. During Orpheus’s stillness, a symbol of his grief, we hear repetitions of the familiar opening, a manipulated descending Phrygian melody, as shown in Example 3, where each of the manipulated repetitions is identified by a new system of music.

[2.3] The Stravinsky-Balanchine version of the myth, a product of mid-century neoclassicism,(12) portrays its characters as doomed from the start. The ballet begins not with the joyous wedding of Eurydice and Orpheus, but after the bride is already dead. From the outset Orpheus embodies in his death-like stillness the unrelenting grief that living beings experience because their time on earth is finite. It is only music itself which is eternal; without either sight or his lyre, Orpheus cannot save Eurydice, and he himself is condemned to a violent death. The second of a trilogy of Greek ballets between two intimate collaborators, this version of Orpheus is filled with ritualistic mourning, a story whose ending cannot be changed, a recounting whose extraordinary grief arises not only in the individual circumstance of the doomed lovers but also in the inevitability of death for all. In the hands of Stravinsky and Balanchine, the deck is heavily stacked against Orpheus, for during the pivotal trip he is blinded by a mask: he cannot even see the direction in which he must go to escape hell.(13)

[2.4] Even though Orpheus does not move in the first scene, we experience, and he hears, the movement of a melody striving to complete a direct descent through the Phrygian scale. Consider the opening bars, given in Example 3: the opening lament tetrachord, attempts to repeat itself, but a return to E is followed by a skip down to A. That succeeding tetrachord completes the Phrygian scale, but not directly, and the nearly complete scale that follows cannot complete a move to the lower E. Instead it is interrupted by another lament tetrachord, and the cycle begins anew. On Example 3 the alignment of the varied repetitions shows how arrivals on the lower E come only from A (rather than an upper E), and that descents from the higher E always fail to reach the lower E.

[2.5] As with Serenade, we feel the tension accumulating as continued melodies point to where Orpheus needs to go—that is, to the Underworld. While Orpheus remains still, Stravinsky’s music remains confined but urgent in its movements. The re-beginnings of the melody, and their continued failures, become more pressing as Orpheus does not move. At the very end of this example, where a move to a lower register signals the Underworld to which Orpheus will soon travel, the descending melody stops for the first time, but on F rather than E, a stunning case of movement denied, as if even the music has given up on urging Orpheus to move.

[2.6] The only physical movement in this opening scene comes from Orpheus’s friends, who try to comfort him with an inanimate stick figure representing his dead wife Eurydice. Responding to the music and to Orpheus’s grief, their movements are confined to steps, but these are not typical balletic steps. Instead of moving toe to heel, these supposed dancers walk heel-to-toe, denying their powers as dancers. Nothing in this scene moves in a typical way. Here is the consummate musician, whose music can cause even rocks to move, seemingly deaf and paralyzed with grief. His lyre remains silent on the ground, and ultimately, the music itself stops its repetitions. The music has failed.(14) And so will Orpheus. During the course of the ballet, having failed to return Eurydice to life, Orpheus dies a hideous death, and thus in the final movement, entitled “Orpheus’s Apotheosis,” the leading dancer is not even present.

Example 4. Orpheus “Apotheosis,” opening and closing music

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

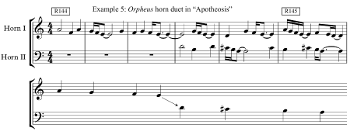

Example 5. Orpheus horn duet in “Apotheosis”

(click to enlarge)

[2.7] But his music returns. My final discussion describes how rising and falling steps, both in dance and music, exquisitely shape the ballet’s end. On Example 4a, the opening of the final movement, Orpheus’s theme finally completes a Phrygian scale at R144. From there, it begins to rise, now on D, as if responding a slower, more tentative rising melody in violin and trumpet. Something is afoot: we have reason to anticipate a responding movement on stage. In fact, Apollo, Orpheus’s father, enters carrying a greatly enlarged version of Orpheus’s mask, the item whose removal caused the deaths of both lovers. Apollo moves by step to stepwise melodies, but notably his steps are balletic, moving properly from toe to heel.

[2.8] Stravinsky supplies a reminder of the dead lovers in the Epilogue’s well-known horn fugue, also beginning also at R144. Stravinsky famously described this music to Nicholas Nabokov as a fugue cut off “with a pair of scissors,”(15) writing that the intervening harp music is “a reminder of

[2.9] Example 5 unites the two voices of the horn duet, suggesting that together they complete the span of an octave, something the two lovers could not themselves do. Is it too much to think that these two descending horn lines might represent the lives of Orpheus and Eurydice, whose lives can only be joined in musical representation? Apollo’s motions certainly support this idea: as the horns are interrupted, he strums Orpheus’s mask as if it were his lute, lifting, (as the score indicates) Orpheus’s “song heavenwards.” Finally, in the final bars of the dance (shown in Example 4b) rising and falling scales come into contrapuntal alignment to reach a final D major chord. On stage, Orpheus’s lyre takes on a life of its own, rising slowly from the ground to the heavens. While mortal life is finite, the movement of music lives on.(16)

Gretchen G. Horlacher

Indiana University-Bloomington

Jacobs School of Music

1203 E. Third St.

Bloomington, IN 47405

ghorlach@indiana.edu

Works Cited

Balanchine, George. 1947. “The Dance Element in Stravinsky’s Music.” Dance Index 6, no. 10–12: 250–56. http://eakinspress.com/danceindex/issueDetail.cfm?issue=danceindexunse_30.

—————. 1968. Balanchine’s New Complete Stories of the Great Ballets. Doubleday and Company.

Boris, Ruthanna. 2008. “Serenade.” In Reading Dance: A Gathering of Memoirs, Reportage, Criticism, Profiles, Interviews, and Some Uncategorizable Extras, ed. Robert Gottlieb, 1063–69. Pantheon Books.

Croce, Arlene. 2009. “Balanchine Said.” New Yorker Magazine, Jan. 26, 2009. http://archives.newyorker.com/?i=2009-01-26#.

Homans, Jennifer. 2010. Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet. Random House.

Joseph, Charles. 2002. Stravinsky and Balanchine: A Journey of Invention. Yale University Press.

Macaulay, Alastair. 2012. “How a God Finds Art (the Abridged Version).” New York Times, Sept. 19, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/20/arts/dance/apollo-orpheus-and-agon-at-city-ballet.html

—————. 2016. “ In Balanchine’s ‘Serenade,’ Rituals and Gestures of Autonomy.” New York Times, Oct. 6, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/07/arts/dance/in-balanchines-serenade-rituals-and-gestures-of-autonomy.html.

Michelman, Fran. 2007. “Marius Petipa.” http://www.abt.org/people/marius-petipa/.

Nabokoff, Nicholas. 1949. “Christmas with Stravinsky.” In Stravinsky, ed. Edwin Corle, 123–68. Duell, Sloan, and Pearce.

Nabokov, Nicholas. 1952. Old Friends and New Music. Little Brown.

Phillips, Tom. 2004. “Unblocking the Moonlight: Reflections on Serenade.” DanceView Times, Aug. 9, 2004. http://archives.danceviewtimes.com/2004/summer/06/serenade.htm.

Sorrin, Ellen. 2013. “From the Director, February 2013.” http://balanchine.com/from-the-director/

Steichen, James. 2012. The Stories of Serenade: Nonprofit History and George Balanchine’s “First Ballet in America.” Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies.

Stravinsky, Igor. 1970. Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons. Harvard University Press.

Volkov, Solomon. 1985. Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky: Interviews with George Balanchine. Translated by Antonina W. Bouis. Simon and Schuster.

Footnotes

* Note to readers: Copyright restrictions do not permit a direct reproduction of the videos of the ballets described below. Instead I provide time locations for a published DVD of the two ballets, as well as youtube links where available.

Return to text

1. Boris 2008, 1064. The diagram is reproduced on 1067. The arrows show where she and another dancer (Annabelle Lyons) each stood. The diagram is also reproduced in Steichen 2012. He remarks that “

Return to text

2. Sorrin 2013. Balanchine recounts how seventeen dancers showed up to the first class he offered, and how that group became the configuration.

Return to text

3. Phillips 2004. A former editor of the CBS Evening News, former Columbia professor of journalism, dance musician, and ballet student, Phillips writes that “Balanchine reportedly told them they were ‘blocking the moonlight.’”

Return to text

4. I thank my colleague Frank Samarotto for helping me create this sketch.

Return to text

5. Phillips 2004 continues as follows: “The heads lift, the arms rise and spread out in first port de bras, and the torso lifts as the right foot points to the side in battement tendu; the dancers breathe and expand,

Return to text

6. This version of Serenade features Darci Kistler. Unfortunately, the credits for the video are shown as the music begins. A second performance (from a New York City ballet production in 1957) is available commercially; the DVD “New York City Ballet in Montreal, Vol. I” (DVD 4571 by Video Artists International). The introduction runs from 0:38 to 2:47.

Return to text

7. Macaulay 2016. The entire quotation is “Martha Graham, seeing ‘Serenade’ for the first time, said her eyes filled with tears when the women suddenly all turned out their feet, heels together, into ballet’s first position: ‘It was simplicity itself, but the simplicity of a very great master—one who, we know, will later on be just as intricate as he pleases.’” Phillips 2004 also mentions this story.

Return to text

8. See Michelman 2007 for a short introduction to Petipa’s work.

Return to text

9. Croce 2009. Similarly, Balanchine 1947 recounts “It was in studying Apollo that I came first to understand how gestures, like tones in music and shades in painting, have certain family relations” (255).

Return to text

10. For a comprehensive study of the Stravinsky-Balanchine collaboration, see Joseph 2002. On 3 he cites remarks made by Balanchine (in a 1962 Canadian Broadcasting Company television documentary about Stravinsky): “We are representing [the] art of dancing, [the] art of body movement, in time, in space. It is the music, it is really time more than the melody, and our body must be subordinated to time—because without time, dance doesn’t exist. It must be order—it’s like a planet. Nobody criticizes the sun or moon or the earth because it is very precise, and that’s why it has life. If it’s not precise, it falls to pieces.”

Return to text

11. Joseph 2002, 209–10 details the poor early reception. Typical is Macaulay 2016: “When it was first performed in 1948 Balanchine’s ‘Orpheus’ carried a charge of genius that played a signal role in the foundation of New York City Ballet later that year. But that aura faded during the 1950s; to many it seemed a relic by the time it was revived for the company’s 1972 Stravinsky festival. Certainly it—not just the choreography but the Isamu Noguchi designs—looked largely quaint when I first watched it in 1980. Quaint it remains.”

Return to text

12. Balanchine 1968, 276. The choreographer refers to this version as “a contemporary version of the ancient myth.”

Return to text

13. The three ballets in the trilogy are Apollo (1928), Orpheus (1947), and Agon (1957).

Return to text

14. The ballet is commercially available on a DVD (“New York City Ballet in Montreal, Vol. I,” DVD 4571 by Video Artists International); it is taken from a New York City ballet production in 1957; the opening music is at 30:35–32:55.

Return to text

15. Nabokoff 1949 recounts “Here, you see, I cut off the fugue with a pair of scissors

Return to text

16. On DVD 4571 by Video Artists International; the closing scene occurs at 55:45–58:38.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2018 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Sam Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

8061