Key Profiles in Bruckner’s Symphonic Expositions: “Ein Potpourri von Exaltationen”? *

Nathan Pell

KEYWORDS: Bruckner, symphonies, Schenker, sonata form, second themes, chromaticism, tonality

ABSTRACT: : Because of their novel harmonic and formal tendencies, Bruckner’s symphonies are often subjected to extravagant analytical practices. Schenker, himself a Bruckner student, viewed them as sublime, but ultimately unworkable, harmonic jumbles: “a potpourri of exaltations.” Darcy has argued that Bruckner’s second themes are largely presented in the “wrong” key, creating a nontraditional “suspension field ... [isolated] from the main line of ... symphonic discourse.” Taking this view as a point of departure, I show (1) that Bruckner’s second theme key choices do not break from tradition—they have precedent in earlier, more canonic literature; and (2) that distinct “profiles” emerge from them: I-to-V in opening movements, I-to-III-to-V in finales. These profiles suggest both that Bruckner conceived of deep structure as chromatically saturated, and that he varied the degree of saturation to differentiate between types of movements. Thus, Bruckner’s chromatic second themes—far from “suspending” a movement’s trajectory—represent powerful, energizing events en route to the dominant.

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

Bruckner’s reputation in this country is something of a mystery. We are told that he was a simple-minded peasant who wrote over-long and simple-minded symphonies; that he was, moreover, a “Wagnerian symphonist” and mystically linked with Mahler. The average intelligent

. . . musician is properly impressed by the German-Austrian musical tradition; but when he is told that in these countries Bruckner is treated as the equal of Brahms and indisputably the superior of Sibelius, he decides that there are aberrations of taste even in the most musical of nations. He expels Bruckner from his consciousness not so much because he dislikes Bruckner’s symphonies—for at best he has probably heard only the fourth and the seventh—but because he has been told by a variety of. . . historians, writing with patronizing conviction, that Bruckner was a well-meaning bore “written up” by the Wagnerites to impress the Brahmins (70).

[0] It may come as a surprise that the above paragraph was penned by an Englishman (Henry Raynor) writing in 1955; for, with a small handful of changes, it could have easily been written yesterday about the current tepid atmosphere of Bruckner reception in North America—although I should add that the symphonies have recently become a more regular presence in concert halls. The theoretical outlook on Bruckner has fallen more or less in step with the general apathy of the performance community. But when theorists have turned to Bruckner’s music, most have done so with a problematic attitude that is well illustrated by one of Raynor’s statements in particular—that Bruckner was a “Wagnerian

Fringe Tonality, Schenkerian Tonality

[1.1] The tendency to group Bruckner with a later band of composers (Strauss, Mahler, Sibelius) represents a significant undercurrent in Bruckner scholarship, specifically among authors concerned with the music’s tonality. The consensus seems to be that if Bruckner’s music is tonal, it is only tonal in an oblique, half-hearted way. Yes, Bruckner’s symphonies start and end in the same key and have many of the trappings of tonal music—but perhaps only as a courtesy to aid the listener. This approximates the view expressed by William Benjamin, concerning the Eighth Symphony:

The listener can construct the apparent monotonality of many late-romantic works but perhaps not experience it as such. In more specific terms, the fact of beginning and ending in the same key may lead to an experience only of return to, and not of the motion within or prolongation of that, properly speaking, constitutes monotonality. (1996, 237–38)

In other words, the music is implicitly or explicitly denied the distinction of ‘organic tonal unity’ that commonly differentiates monotonality from other, looser varieties of tonality.(1) We are left to wonder: Of what sort, then, is Bruckner’s tonality?

[1.2] On the other hand, perhaps this music really is best viewed as tonal in a far stricter way. Benjamin captures well the most central feature of this sort of tonality: “motion within,” or Auskomponierung, an integrative process whereby some voice-leading events are pressed into the service of elaborating others. It is in this sense that I will be referring to tonality throughout this article. Schenkerian analysis of course serves to confirm a work’s tonal unity, and as such can be understood to exert a conservative, “recuperative” (to use Joseph Straus’s [2011] term) force on the music it examines. However, paradoxically enough, the Schenkerian approach has tended to modernize Bruckner: in the Sixth Symphony, Timothy Jackson sees an “anticipatory tonic” in the development of the second movement (2001, 224);(2) analyzing the Fourth Symphony, Edward Laufer reads the entire first movement as an Anstieg (2001, 116).(3) These and other fairly exotic readings suggest that Laufer and Jackson consider Bruckner to occupy the outer fringes of Schenkerian tonality: an assessment which, in turn, seems to have led Julian Horton (among others) to believe that one cannot apply Schenker to Bruckner without extensively modifying the theory or losing fidelity to the music. On the one hand, “a Schenkerian analysis that demonstrates the absence rather than the presence of an Ursatz is effectively self-negating” (Horton 2004b, 93); but on the other hand, “if our aim is to show that Bruckner really composed in a Schenkerian manner after all, then we have simply succeeded in forcing him to submit to the hegemony of a single, encompassing theory” (264).(4) Consequently, recent authors have resorted to Schenker in dribs and drabs, and in a somewhat diluted form.(5)

[1.3] This brings us to Schenker’s own opinion of Bruckner—a position worth taking seriously if we mean to apply the analytic system Schenker himself created. Schenker took classes with Bruckner at the Vienna Conservatory and at the University (Federhofer 1982, 198). Moreover, we know from the lesson books that he played Bruckner symphonies with his students in four-hand arrangements (Schenker 1918–1919) and from Der Dreiklang that he knew all of the symphonies by heart.(6) He appears indeed to have enjoyed quite a bit of Bruckner’s music, at least on the surface. Nevertheless, throughout his life Schenker regarded him as a lesser composer who could not muster a sense of tonal unity because of his compartmentalized thematic processes. He believed that “the very force and splendor of the individual [themes appear] to work against their synthesis.” And he accused Bruckner of “[luxuriating] in the component parts” so as to “lose all sense of form and tonality.” As a result, Schenker found Bruckner’s symphonies to be written in “an exalted manner, reckoned in terms of exaltation, so to speak; a symphony by him, taken as a whole, represents a kind of a potpourri of exaltations (ein Potpourri von Exaltationen)” ([1905–1909] 2005, 116).(7)

[1.4] These problems of “form and tonality” have long hindered Bruckner’s acceptance into the analytic canon. As Horton has written, “canonical preoccupations, perhaps combined with a more general atmosphere of musicological disdain, have created a neglect among Anglo-American analysts that has only recently begun to be redressed” (2004b, 20). But Bruckner’s liminal status within the canon has had ramifications surpassing mere neglect: more generally, such “canonical preoccupations” embody the lasting half-life of Bruckner’s poor reception by his contemporaries. Just as Hanslick and Kalbeck strove to isolate Bruckner’s work from the Beethovenian symphonic tradition, the theoretical community has distanced Bruckner from analytical procedures used on more standard repertoire (Venegas 2017). Searching for a palpable musical basis for this distancing—and for a way forward from it—has become a significant distraction in the scholarship; as a result, many theoretical articles about Bruckner (this one included) are obliged to start with a lengthy prolegomenon that takes pains to justify the author’s chosen approach and that grapples with the attendant methodological pitfalls. These extra hurdles, in my view, have hamstrung analytic work on the symphonies by reinforcing the impression that they are somehow unamenable to traditional means of examination. The present study attempts to undo some of Hanslick’s handiwork, thereby helping to ratify Bruckner’s reputation as a composer of tonal music—as a composer we need not fear addressing with an analytic system rooted in tonality. I hope, in the process, to avoid further reifying the “tonal canon” that has marginalized Bruckner and a great many other composers.

[1.5] Indeed, it is my belief that by resisting the impulse to discount Bruckner’s tonality, we can uncover many relations in the music that the analytical literature has by and large overlooked. This applies specifically to Bruckner’s choices of key areas within sonata form; thus, a main goal of this study is to address Bruckner’s sonata-form design in rather strict Schenkerian terms. In the process, however, we must take care to avoid a dangerous aspect of Schenker’s thought: his equation of a work’s tonality with its quality. For him, as is well known, a piece that was not tonal was bad, and Schenker used his analytic method variously as a pedestal to valorize some works and as a cudgel to denigrate others. In fact, it was a favorite strategy of nineteenth-century critics to shore up value judgments, both positive and negative, with music theory as a bracing. I strongly believe that it is important to study the music one loves, and musicians should not be ashamed to use analysis to express their admiration. But I do not think that music theory should ever be weaponized; and furthermore, too tight a link between theory and criticism risks damaging the accuracy of both. Thus I believe that theoretical claims should stand on their own. I ask the reader to understand that when I engage with the assessments of Bruckner’s critics (Schenker among them), I try to do so based on the theoretical substance of their claims, decoupled from their nineteenth-century aesthetic baggage.

Formality and Deformation

[2.1] Bruckner’s sonata-form movements will serve as our window into these questions of tonality, and so let us consider his approach to form in more detail.(8) We are all undoubtedly familiar with the experience of mistaking a so-called transition theme for the “real” second theme in sonata movements by Haydn, Mozart, or Beethoven. These composers, and countless others, seem to enjoy a certain amount of compositional sleight of hand as to formal design—not to mention that they surely did not rely so heavily on these rigid demarcations as we do. However, such moments are exceedingly rare in Bruckner; often one finds oneself asking, “What key is this theme in?,” but never, “What is the theme?” As a result, Bruckner perhaps calls for less subtlety in this regard than other composers.

[2.2] However, these observations conceal a larger issue: ever since the 1870s, this formal straightforwardness has been cast in a far more negative light, and critics have persisted in lambasting Bruckner for packaging his harmonic innovations in stale forms. Tovey writes: “Bruckner conceived magnificent openings and Götterdämmerung climaxes, but dragged along with him throughout his life an apparatus of classical sonata forms as understood by a village organist” (1935, 121). Franz Schalk, Bruckner’s longtime pupil and assistant, delivered a similar and surprisingly damning assessment: “Nothing is more primitive than Brucknerian form

[2.3] But because this “hint of stiffness or formality” (Korstvedt 2004, 173) is deployed in so wide-ranging a chromatic environment, the opposite critique has also arisen, that of an assortment of “tonal shapes willfully strung one after another.”(10) Such claims about Bruckner’s bungled approach to form naturally bleed into a general gainsaying of his harmonic practice and organization that was first articulated by Eduard Hanslick: “It remains a psychological puzzle how this gentlest and most peaceable of all men

[2.4] Warren Darcy provides an interesting answer to these questions in “Bruckner’s Sonata Deformations” (1997). Here he addresses the Brucknerian sonata paradigm and explores how it differs from that of earlier composers. Bruckner’s daring harmonic decisions throughout a given movement can trigger various types of “sonata deformations”—a concept that would become a centerpiece of Darcy and James Hepokoski’s Elements of Sonata Theory (2006). A deformation is not a negative event, but rather a noticeable deviation from traditional practices that the movement must address in order to succeed (Darcy 1997, 257–58). One of the deformations proposed by Darcy is the so-called “alienated secondary theme zone,” which simply means that the second theme is presented in an unexpected key (271–74).(12) The expected key is determined by the mode of the movement: the dominant in major and the mediant in minor. For Darcy, second themes that diverge from this mold are not only unexpected, but disruptive: “Beginning with III/4 [the finale of the Third Symphony], most of Bruckner’s expositions make a point of presenting S [the second theme] in the ‘wrong’ key, representing a tonal dissonance that must be resolved, either within the secondary zone itself or later” (272). This ‘wrong key’ “is felt to be tonally alienated from the overall i–III or I–V progression” (272), and the resulting alienation deflects the course of the sonata form, suspending or defeating linear time (263) and creating what Darcy terms a “suspension field” (271). In addition to being presented in a foreign key area, these themes are often repetitive and lyrical, which Darcy sees as heightening the sense of alienation.(13) “The net result,” he concludes, “is to isolate the secondary theme zone from the main line of the default symphonic discourse. This does not mean that the movement as a whole will necessarily ‘fail,’ but it does suggest that ‘success’ is not to be won along the traditional lines of sonata discourse” (274).(14)

[2.5] I find myself skeptical about several of these principles, as they appear in the writings of Darcy and the century of critics that preceded him. In particular, I wonder whether Bruckner’s second themes are arrayed in truly non-traditional keys, and whether they are best felt as “alienated” and “wrong” in comparison to the eventual ascendance of the expected (or “right”) key. Despite my reservations, Darcy’s arguments lie at the very nexus of form and tonality. As such, he has provided us with excellent points for consideration, which I will address below.

[2.6] In the following study of Bruckner’s sonata form, I will evaluate Darcy’s conclusions, as encapsulated by the following guiding questions:

- To what extent is Bruckner’s treatment of key in sonata form “along the traditional lines of sonata discourse?” (Darcy 1997, 274).

- Are Bruckner’s second themes tonally alienated from the overall harmonic design of the sonata form? In other words, are they in the “wrong” key?

I hope to show that Bruckner’s treatment of sonata form is a natural continuation of earlier approaches; and that despite a tangle of harmonic complexity on the surface, a robust and coherent underlying harmonic structure supports the general form.

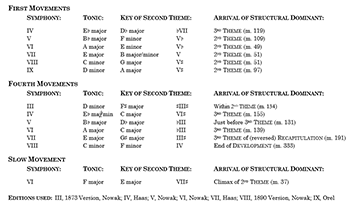

Example 1. Key Schemes of the Expositions

(click to enlarge)

[2.7] The corpus of Bruckner sonata forms that I will examine excludes all of the student works (such as the Study Symphony), as well as the String Quintet and the finale of the Ninth Symphony (which I will comment on only in passing). Although the latter is far more complete than is generally assumed, it is not widely available. I also exclude the Symphony in D minor (“Die Nullte”), the First and Second Symphonies, and the first movement of the Third Symphony. In these, Bruckner follows the so-called traditional sonata paradigm as we might expect: all three symphonies are in minor and the second themes are all in the mediant. What remains are the mature, complete, symphonic sonata-form movements featured in Example 1. Here I list the tonic of each movement, the key of the second theme, and the point at which the structural dominant arrives. For the purposes of this essay, I restrict my discussion to the exposition, except in those cases where the dominant arrives in the development.

Bruckner and Tradition

Example 2a. Formal Precedents for Bruckner’s Key Schemes

(click to enlarge)

Example 2b. Schenkerian Precedents (from Der Freie Satz) for Bruckner’s Voice Leading

(click to enlarge)

[3.1] I will start by touching briefly on the first question: Are Bruckner’s key choices “traditional”? We must first compare the symphonies with earlier music, both from a formal perspective (to determine the limits of mid-nineteenth-century sonata practice) and from a Schenkerian perspective (because I argue that this music uses strictly tonal voice leading to compose out middleground harmonies). In Example 2a, every sonata-form movement of Bruckner’s is shown to have a precedent in terms of its key scheme; of course, the voice leading differs widely from case to case, but there is something to be said for examining a work’s key design in broad strokes. From these analogies, I think we can conclude that Bruckner’s key choices are at least no great departure from the nineteenth-century practice of Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Chopin, and Brahms.(15) In order to show that Bruckner’s harmonies behave in ways that Schenker considered tonal, I have included in Example 2b a list of references to figures in Der freie Satz ([1935] 1979). A look at these figures will reveal that my graphs (in Examples 3 through 6 and the Appendix) contain nothing more progressive than may be seen in Schenker’s own examples, some of which are quite extravagant. These comparisons also shed light on a further consequence of Bruckner’s non-canonic status: a double standard that treats, say, a Mendelssohn as conservative, but a Bruckner as avant-garde. The similarities in harmonic and formal procedure between Bruckner and composers whose music resides firmly within the analytic canon should cause us to question the basis on which that canon rests and the wisdom of its rigid boundaries. At the very least, I hope Example 2 will serve to substantiate my claim that Bruckner should not be considered a modernist when very little that he does is without some precedent.

[3.2] So are Bruckner’s sonata-form movements traditional? Largely. Are they textbook? No. But it is hardly reasonable to always expect textbook devices in symphonies written in the late nineteenth century, not to mention that the Formenlehre textbook itself was even then still developing.(16) Updates to Sonata Theory, particularly the advent of dialogic form, have mitigated this problem; but I believe that any approach that centers around forms and deformations thereof puts the emphasis in the wrong place. Rather than merely asking, “What is the key scheme of the movement?,” I think it is more productive to examine how the keys a composer visits contribute to the overall logic of each particular symphony. Schenkerian analysis—the use of which is entirely appropriate owing to Bruckner’s more or less conventional voice leading—will prove instructive in evaluating the sui generis logic of the movements under consideration. Therefore, I will now move to our second guiding question: Are Bruckner’s second themes in the “wrong” key? I will show that, according to Bruckner’s own unique symphonic logic, his choices are very “right,” indeed almost inevitable in their own way, in terms of both form and tonal structure.

Bruckner’s Key Schemes: A Method in the Potpourri

[4.1] Returning to Example 1, note that I have not grouped movements by what symphony they belong to, nor by their mode. For indeed, these groupings shed no light on Bruckner’s key choices. Rather, the governing principle behind the key structure of Bruckner’s mature sonata forms proves to be position within the symphony. First movements express the key scheme I–V, finales for the most part I–III–V.(17) (Our only sonata-form slow movement passes through an entirely different key on its way to the dominant.) There are exceptions, most of which I will return to;(18) but the evidence shows a distinct difference in key schemes between Bruckner’s opening and closing movements.(19) As far as I am aware, this pattern has never been mentioned in the scholarly literature.(20) I should stress that this is somewhat of an idiosyncratic procedure, for normally key areas within a sonata form are determined by the mode of the tonic, regardless of the numeral that appears over the first page of each movement in the score. But it is not unusual to find a formal paradigm that applies to one type of movement but not to another. The sonata-rondo as finale is a ready example. In the case of Bruckner’s key schemes, I do not view this difference between opening and closing movements as a formal aberration. Rather it represents a formal reification of two aspects in particular of Bruckner’s symphonic writing: first, a considerable degree of modal mixture in the middleground and, second, a deep sensitivity to concerns of large-scale symphonic pacing.

Chromaticism as Formal Device

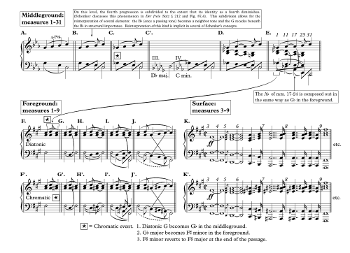

Example 3. Bruckner VIII: Finale Opening

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.2] It is well known that Bruckner’s music is chromatic. But I contend that this quality is best understood as a complete chromatic saturation of the tonic diatony, and that part of the explanation behind Bruckner’s key designs lies in the fact that he constantly found ways to incorporate mixture into the middleground. The integrity of chromatic events to Bruckner’s structural conception comes across with particular clarity at the beginning of the finale of the Eighth Symphony. The piece is in C minor, but this movement starts in

[4.3] Let us now examine the passage’s foreground chromaticism. Figures F through J focus on the composing-out of the initial

[4.4] From these opening measures, we can see how Bruckner keeps a watchful eye on his deployment of middleground chromaticism for formal reasons. In this case he forges a connection between the third and fourth movements—weakening a formal boundary by building a bridge across it. Bruckner also used large-scale mixture to solidify formal boundaries; and one way he differentiated between movements structurally was by choosing key schemes that treat first movements as if they were in major, and finales as if in minor. Not only does this build a formal parameter that acts across the span of the symphony, but it also creates a seamless impulse of chromaticism through the structural layers, sown in the middleground and brought to fruition in the foreground.

Chromaticism and Symphonic Length

[4.5] The rest of the formal explanation of Bruckner’s key choices has to do with length.(22) Bruckner was the first noteworthy symphonist since Beethoven to consistently push past the thirty- to forty-minute mark. When ideas are given more time to develop, naturally more development can and will occur. Permit me to frame this relation in allegorical terms. If a piece is to be a long one, Time seeks accommodation from Voice Leading; and Voice Leading duly expands, creating more content to fill the space Time has allotted. In particular, I would like to apply this idea to harmonic development: Is it coincidental that the works of the early nineteenth century that exhibit some of the boldest harmonic plans—Beethoven’s Waldstein or Hammerklavier Sonatas; Schubert’s Great C major Symphony or String Quintet in C major—are also the longest? I believe not. We can understand this correlation as an outgrowth of the nature of voice-leading content; the longer a stretch of voice leading, the more likely it is that the resources of an unmixed diatony will become exhausted. This is of course not to say that introducing chromaticism is the only way to expand voice-leading content to fill a certain amount of time: composers have many such resources at their disposal. But because of the tremendous capacity that chromatic elements have for attracting attention to themselves, it is difficult in large movements for composers to avoid monotony without incorporating them. Thus it is no wonder that the nineteenth century, in ever grander works, extended and varied the harmonic aspects of the formal frameworks inherited from the preceding century.(23) Chromaticism and length walk in lockstep.(24)

[4.6] Viewed this way, what might be a renegade harmonic stance in a five-minute piece—the famously problematic Mozart Minuet in D, K. 355 comes to mind (see Oster 1966, 34)—could be contextualized and mitigated into a more normal position when surrounded by more music, thus allowing longer music to have more thoroughly integrated chromatic events. I believe that this principle is crucial for understanding Bruckner’s symphonies: their second themes, though framed in highly chromatic keys in the finales, are made tonally acceptable by the vast temporal space Bruckner affords them. By the same token, their tremendous length can be understood to call for a greater degree of chromatic saturation.

[4.7] Equally important to Bruckner’s formal choices is the difference in scale between first movements and finales. It goes without saying that symphonic finales traditionally have brisker tempos and more rhythmically driven themes than their opening counterparts, to project a certain forward-driving dynamism. Usually finales are shorter as well. But Bruckner follows the trend epitomized by Beethoven’s later works—like the Ninth Symphony and

[4.8] We have yet to examine the issue from a truly Schenkerian perspective; but from a formal one, I hope to have shown so far that Bruckner’s second theme key choices are not random and that the lyric material of a movement is never in the “wrong” key—indeed I view these choices as necessary to an organic structure. The fact that Bruckner used middleground chromaticism as a formal parameter to differentiate first movements from finales reveals that the keys of his second themes are neither otiose, nor wholly unpredictable.

Key Profiles and Voice-Leading Coherence

[5.1] Up to this point, I have focused my discussion of sonata form around Bruckner’s “key schemes”: a blunt term referring to a succession of Roman numerals that indeed may have no structural significance. But from a Schenkerian stance, we cannot really determine the “foreign-ness” or “wrongness” of a given key choice until we have seen how it is incorporated into the voice-leading approach to the structural dominant (which is after all the goal of the first half of Schenker’s sonata form). And so I argue that these “key schemes” are instead better viewed as “key profiles”: a dynamic interaction of structural keys pressed into service by the voice leading that heralds the advent of the dominant.(26) As I noted before, Bruckner’s first movements go directly to the dominant, and thus do not require further comment, so now let us turn our attention to the finales.

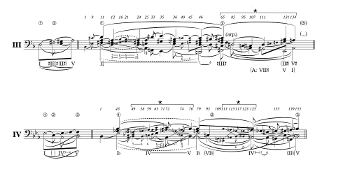

Example 4. Bass-Line Sketches of Bruckner’s Finale Expositions

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[5.2] Example 4 comprises bass-line sketches of six all of the Bruckner finales under consideration, with middleground sketches on the right and further reductions—distillations of what I consider the “key profiles”—on the left.(27) (Asterisks mark difficult passages that require more detailed graphs, which I provide in the Appendix. Click on an asterisk to jump to the relevant spot in the Appendix.) A survey of these readings (which should be viewed as just that) will reveal their most salient features. Four of the finales arpeggiate I–III–V: those of the Third, Fifth, Seventh, and Eighth Symphonies. The raised mediant (

[5.3] We can see from these key profiles that Bruckner's second themes always serve a distinct voice-leading purpose. Moreover, it is worth noting that all of the finales under consideration here have tonally open second theme groups: they do not cadence in the key in which they begin. In this regard, it is important to recall Schubert’s practice in the majority of his so-called “three-key” expositions, which was as instructive for Bruckner as it was for Brahms.(30) As we have seen, theories of form tend to treat tonally open second theme groups as harmonically marginal, because of a general belief that cadences (i.e., endings) define both form and tonal structure.(31) This view seems at odds with Bruckner’s very deliberate placement of his second themes, which always begin on their local tonic and on a hypermetric downbeat.(32) Therefore I find it more appropriate to consider the beginnings of Bruckner’s second groups as true points of formal articulation, tethered to the dominant through strong voice leading.(33)

[5.4] For this reason, I find it misleading to speak of the “isolation” or “wrongness” of Bruckner’s second themes. Indeed, their “rightness,” it seems to me, resides primarily in the variegated trajectories they enable Bruckner to create across his finale expositions: he introduces the second theme in a single monolithic stroke, but then allows the lyric material of the second group to wend its way little by little towards the third theme’s climactic dominant. Certainly the onset of the second theme’s “foreign” key can astonish the ear. The gap that leads into it, usually falling by a major third, might sound more like a chasm, and indeed the sheer novelty of the key might seem the perfect metaphor for remoteness. But I urge that we keep this sort of “in-the-moment” hearing in its proper place. For although these impressions surely exist, so too, in Bruckner’s mature music, exists the feeling that in a deeper sense we are being guided by the reliable hand of a sensitive craftsman. Thus the second key starts us on a journey towards a goal—the dominant—and the remoteness of its key generates voice-leading content, as I have argued above. When we listen to one of Bruckner’s second themes, then, it is important that we not become fixated on its exotic key, but rather that we also try to hear to the end of the tonal motion it initiates. Furthermore, while I would not disagree that their lyric characters often contrast markedly with the preceding material (and appreciate the attendant semiotic ramifications), these qualities should not be conflated with the themes’ tonal deployment. In other words, though these elements might display a sort of “expressive alienation,” I would refrain from singling them out through the theoretical concept of “tonal alienation,” once again because Bruckner integrates them completely into the voice leading.

[5.5] With these key profiles, we are examining how the dominant is approached through Bruckner’s voice leading, and as I mentioned above, this is indispensable for any Schenkerian treatment of the symphonies. But we have not yet shaken off Schenker’s claim that Bruckner’s themes do not add up, that although the voice leading may ‘check out,’ we nevertheless still have a “potpourri of exaltations” on our hands. To address this claim, we must delve deeper into a single movement and show the voice leading to be no mere coincidence, but rather a consequence of some more elemental thematic unity. We should be able to find fingerprints of this ‘intelligent design’ in a profound resonance between structural layers that shows the evolution of an idea as it passes through various stages of realization.

Example 5. Symphony VI: Adagio (Middleground)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 6. Symphony VI: Adagio (Foreground)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[5.6] For this demonstration I have chosen the Adagio from the Sixth Symphony, a beautiful sonata-form movement which is notable for its remarkably elegant voice leading and its unusual key scheme, the only one I have not yet discussed.(34) My deep-level graphs are given in Example 5; a more thorough examination of the movement’s voice leading and motivic construction is shown in Example 6.(35) To mention only a few aspects of my analysis: the second theme, in E major (the key of the leading tone), comes about through a chromatic harmonization of an unfolding of the dominant in the bass. The dominant harmony arrives in measure 37, after V7 of VI in E major is enharmonically redefined as an augmented sixth in the tonic key.(36)

[5.7] Perhaps even more interesting, however, is the origin of the upper voice

[5.8] The other two harmonizations of

Bruckner and Chromatic Tonality

[6.1] I return now to the subject of Bruckner’s tonality, with which I began. I wonder whether the dizzying effect of some nineteenth-century chromaticism has clouded our thinking as to its purpose. Specifically, I suspect that the role of chromaticism at the outer limits of tonal practice has been subject to some misapprehension owing to our belief that chromaticism serves to undercut a tonic’s strength (that is, the degree to which a tonic is heard to exert its control over non-tonic events). And perhaps we have been unduly concerned with what a tonic is rather than what it does: the tonal work of establishing proxies through which the tonic itself can act. I raise these as questions that seem to follow from my discussion of Bruckner’s chromatic key profiles, but to which I can only suggest the answers. However, because of their central and provocative nature, I think them worth exploring.

[6.2] It is generally assumed that the more obviously a tonic presents itself, the more recognizable its control, the stronger that tonic is. From this vantage point, Mozart’s tonic is indisputably stronger than Bruckner’s, for with Mozart the tonic’s governing status is rarely cast into doubt and no other keys ever present themselves as serious pretenders to its title. These little-challenged tonics do not need to do much tonal work to harness the musical elements around them; indeed the actions they do undertake are performed transparently and with ease.

[6.3] But what if these sorts of tonics are not the strongest?—even though they certainly appear to be. For music to be tonal, its tonic must control all the surrounding elements—no matter how far-flung—some through its own power, others by proxy. When a tonic’s gravity fails to be all-encompassing, tonal cohesion is lost; and so, even in the most harmonically remote passages, truly tonal music makes the presence of its main key felt—albeit, perhaps, dimly. It would seem, then, that we ought to measure the strength of a tonic by the degree to which it can exert its influence over material that is difficult to control, whose mastery requires the marshaling of immense tonal will. Victor Zuckerkandl was deeply sensitive to this struggle:

Tonality means

. . . the wielding of central power in the face of a perpetual challenge. Harmony puts means at the disposal of music that are capable of overthrowing a center and establishing a new one on a moment’s notice. With this the position of the tone at the center has become permanently unsafe. And the tonic meets the challenge and truly asserts its power by actually giving it away, letting other tones take possession of it, withdrawing from the foreground of events, but then, in the decisive moments, proving itself strong enough to regain the central place and force the movement back into its, the original tonic’s, orbit. . . . In a sense, the notion of tonality is at stake every time; the issue must be decided every time anew. Will the original center succeed or fail to reassert itself? (1959, 213–14)(37)

[6.4] There is no element that poses so great a threat to a tonic’s hegemony as chromaticism, which endangers the fulfillment of the tonic’s principal goal: to present the fullest possible expression of its diatony (that is, to compose itself out). For this reason, the composer of tonal music must handle chromatic elements with surpassing care, lest they overwhelm the tonic itself. Brahms’s student Gustav Jenner articulated his teacher’s thoughts on the matter beautifully: “the main point [for Brahms] was to express fully the primary key and to reveal its control over secondary keys through clear relationships. In this way, so to speak, the sum of all the keys employed in a piece appeared like an image of the primary key in a state of activity” (quoted in Schachter 1987, 299). According to Schenker, if chromatic keys (more properly, tonicized Stufen that undergo mixture) are used in this fundamentally supportive way and are not allowed “in any way [to] cancel the main key, we must obviously welcome them as an enormous increasing of compositional means, designed to enhance the effect of the diatonic system” ([1906] 1954, 298). Indeed, as I have argued above, Bruckner’s chromaticism should be regarded as a vital generator of content. But the chromaticism’s tonal benefits—of allowing for a richer expression of the diatony—would be for naught if the overall tonic itself were not strong enough to withstand it. It would seem to follow, then, that a tonic is strongest when it permits, directs, and fully encompasses a wide range of chromatically mixed elements—with the caveat that these chromatic elements ultimately subordinate themselves to the tonic in order to reinforce it. Thus Schenker’s proclamation: “the artist can never write too chromatically, in so far as it is his intention to illuminate and clarify the diatonic relations by chromatic contrasts” ([1906] 1954, 298–99).

[6.5] Should we accept it, this principle would call into question an oft-repeated narrative of tonality’s decline and fall. The traditional story (recall the words of Henry Raynor, which began this article) claims that the tonality of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries underwent increasingly concerted assaults from such composers as Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler, and Schoenberg (although the earliest to loosen somewhat the strictures of tonality was perhaps Schubert); and that, despite its continued cultivation in the late works of Brahms (although in a decidedly elliptical form), classical tonality did not survive long into the twentieth century. Under this view, the process that defeated tonality was one of dissolution, of attenuation, of fizzling out. The operative idea is that intrinsically foreign elements, like chromaticism, chipped away at tonality until only its shards remained.

[6.6] This story views the least challenged tonic as strongest, and essentially assumes that chromaticism can only serve to weaken a tonic’s pull. On the contrary, Schenker’s dictum, “the artist can never write too chromatically,” implies that tonality in fact became stronger throughout the nineteenth century, since its influx of chromaticism generally allowed composers to wield more powerful tonics, with the opportunity to integrate a far wider array of chromatic impulses. Thus, if we are to understand chromaticism in this way, the governing metaphor for the end of tonality would not be one of attenuation, but instead one of excess—think of the breaching of a dam or an immense structure collapsing under its own weight. As more was added to tonality’s edifice, the harder it became for even the firmest of tonics to sustain. Eventually, at some presumed tipping point, tonality finally gave way like an over-tall tower of blocks; and, as the nineteenth century grew more distant, it became increasingly difficult to discern from tonality’s scattered remnants the order in which they once stood. Of course, there was not a sole, singular moment in which tonality was summarily wiped from the map: rather a steady stream of “tonal ruptures” in the music of composers who were discovering new ways to create voice-leading content.(38) The eventual aggregate of these developments became the ‘straw that broke the camel’s back.’ I hasten to add, contra Schenker, that this must not be construed negatively.

[6.7] Note that the conception of tonality posited here holds, rather paradoxically, that the strongest tonic may well be nearly imperceptible at times—when it makes its presence known only at the very deepest removes of tonal hierarchy—because a tonic’s strength is not necessarily related to how obviously or how often it is presented on the music’s surface. Such a claim might seem curious, if not outright suspect, and a far cry from the common wisdom that Mozart’s tonics should be stronger than Bruckner’s because they are more keenly perceived. But even if we do accept this conception for the chromatic practice of Beethoven and Chopin, can we reasonably apply it to the music of Bruckner, whose rampant chromaticism has led over a century’s worth of commentators (both music critics and music theorists) to deny strenuously that it obeys the precepts of monotonality? More precisely, the question is: Do Bruckner’s chromatics reinforce the tonic, or do they defeat it? While the success of Bruckner’s chromaticism (which so deeply occupied his critics) must remain entirely subjective, I believe we can productively assess its purpose.

[6.8] The proof that Bruckner presses his chromaticism into the service of the tonic has been the principal subject matter of this essay. Recall in particular his second themes; far from deflecting the tonic’s motion towards the dominant, these themes use their chromatic content to sculpt a sinewy trajectory. Their beginnings firmly present themselves as a waypoint along this path, and the ensuing voice leading is—like Brahms’s—robust and goal-directed: successor to Mozart’s most artful transitions and Schubert’s three-key practice.

[6.9] Contrast this manner of composition with the tonic-defeating tonal ruptures of later music. Here the second theme is truly presented as “apart from” the exposition in terms of voice leading, and its tonal circumstances seem irreconcilable with Schenker’s insistence that middleground Stufen participate in the composing out of deeper structural harmonies.(39) Indeed, this can be taken as a condition of Schenkerian tonality. That Bruckner’s music can be shown to adhere to this organizing principle and to employ chromaticism in a fundamentally purposeful, supportive—indeed, tonal—way should encourage us to decouple Bruckner in our thinking from the generation of composers that followed him. And furthermore, it is high time that we approach Bruckner with the same suspension of tonal disbelief that we readily grant to other composers, in which we allow ourselves to be conducted through a blur of chromaticism by the hand of the composer—and indeed by the developing certainty of the tonic’s pull. Far from the destruction of monotonality,

What happens in every great composition of Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, and Bruckner, expressed in one formula, is the ultimate triumph of tonality. We observe the central power pass from tone to tone, new centers establish themselves for apparently unlimited stretches of time, the original tonic is completely lost sight of; but if we watch the path traveled by the center itself, there emerges from the detours and meanderings of an often seemingly erratic motion a clear pattern, which betrays the action of a force behind the scenes: it is the original center—which had merely withdrawn into the background and from there had secretly controlled the course of events, leading them to a point where it could finally come out again into the open and take over—revealing itself as the supreme power in the play, the center of centers. (Zuckerkandl 1959, 214)

[6.10] To be sure, Bruckner does not give us the patent tonality of earlier composers—often the sensation of harmonic grounding is fleeting. But it is there, and so his method should not be regarded as a departure from earlier Romantic techniques, but an extension of them. In fact, I have suggested that Bruckner’s tonality is stronger for being able to organically subordinate such disparate and mixed harmonic elements. As such, I find Schenker’s methods particularly well-suited to analyze Bruckner’s music precisely because they allow us to delineate both the basic tonal foundation of a piece and the intricate harmonic fabric that elaborates it.

Nathan Pell

The Graduate Center, City University of New York

365 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10016

npell@gradcenter.cuny.edu

Works Cited

Beach, David. 1983. “A Recurring Pattern in Mozart’s Music.” Journal of Music Theory 27 (1): 1–29.

Benjamin, William E. 1996. “Tonal Dualism in Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony.” In The Second Practice of Nineteenth-Century Tonality, edited by William Kinderman and Harald Krebs, 237–58. Nebraska University Press.

Betson, Nicholas. 2012. “Bruckner’s Formal Principle as Beyond the Sonata Principle.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, New Orleans.

Burstein, L. Poundie. 1998. “Surprising Returns: The

—————. 2005. “Unraveling Schenker’s Concept of the Auxiliary Cadence.” Music Theory Spectrum 27 (2): 159–86.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

Dahlhaus, Carl. 1980. “Issues in Composition,” translated by Mary & Arnold Whittall. In Between Romanticism and Modernism: Four Studies in the Music of the Later Nineteenth Century, 40–78. University of California Press.

Darcy, Warren. 1997. “Bruckner’s Sonata Deformations.” In Bruckner Studies, edited by Timothy L. Jackson and Paul Hawkshaw, 256–77. Cambridge University Press.

Drabkin, William. 2011. “Heinrich Schenker und die Symphonien Anton Bruckners.” In Johannes Brahms und Anton Bruckner im Spiegel der Musiktheorie: Bericht über das Internationale Symposium St. Florian 2008, edited by Christoph Hust, 45–55. Hainholz Verlag.

Federhofer, Hellmut. 1982. “Heinrich Schenkers Bruckner-Verständnis.” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 39 (3): 198–217.

—————. 1990. Heinrich Schenker als Essayist und Kritiker. Olms Verlag.

Gault, Dermot. 2011. The New Bruckner. Ashgate Publishing.

Grant, Aaron. Forthcoming. “Schubert’s Three-Key Expositions.” Ph.D. diss., University of Rochester.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press.

Hooper, Jason. 2011. “Heinrich Schenker’s Early Conception of Form, 1895–1914.” Theory and Practice 36: 35–64.

Horton, Julian. 2004a. “Recent Developments in Bruckner Scholarship.” Music and Letters 85 (1): 83–94.

—————. 2004b. Bruckner’s Symphonies: Analysis, Reception and Cultural Politics. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2005. “Bruckner’s Symphonies and Sonata Deformation Theory.” Journal of the Society for Musicology in Ireland 1: 5–17.

Howie, Crawford. 2002. Anton Bruckner: A Documentary Biography, Vol. II: Trial, Tribulation, and Triumph in Vienna. The Edwin Mellon Press.

Hunt, Graham. 2009. “The Three-Key Trimodular Block and Its Classical Precedents: Sonata Expositions of Schubert and Brahms.” Intégral 23: 65–119.

Jackson, Timothy L. 1997. “The Finale of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony and the Tragic Reversed Sonata Form.” In Bruckner Studies, edited by Timothy L. Jackson and Paul Hawkshaw, 140–208. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2001. “The Adagio of the Sixth Symphony and the Anticipatory Tonic Recapitulation in Bruckner, Brahms and Dvořák.” In Perspectives on Anton Bruckner, edited by Crawford Howie, Paul Hawkshaw, and Timothy Jackson, 206–27. Ashgate Publishing.

Jonas, Oswald. [1937] 1989. “Heinrich Schenker: Über Anton Bruckner.” Der Dreiklang: Monatsschrift für Musik 7; reprinted, Olms Verlag: 166–76.

[Jonas, Oswald and Felix Salzer]. [1937] 1989. “Der Nachlaß Heinrich Schenkers.” Der Dreiklang: Monatsschrift für Musik 1; reprinted, Olms Verlag: 17–22.

Kessler, Deborah. 2006. “Motive and Motivation in Schubert’s Three-Key Expositions.” In Structure and Meaning in Tonal Music: Festschrift in Honor of Carl Schachter, edited by L. Poundie Burstein and David Gagné, 259–76. Pendragon Press.

Korstvedt, Benjamin M. 2000. Bruckner: Symphony No. 8. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2001. “‘Harmonic Daring’ and Symphonic Design in the Sixth Symphony: An Essay in Historical Musical Analysis.” In Perspectives on Anton Bruckner, edited by Crawford Howie, Paul Hawkshaw, and Timothy Jackson, 185–205. Ashgate Publishing.

—————. 2004. “Between Formlessness and Formality: Aspects of Bruckner’s Approach to Symphonic Form.” In The Cambridge Companion to Bruckner, edited by John Williamson, 170–89. Cambridge University Press.

Kosseff-Jones, Ryan. 2017. “Mahlerian Tonality: Challenges to Classical Foreground Structures in the Music of Gustav Mahler.” Ph.D. diss., City University of New York.

Kraus, Joseph C. 1997. “Phrase Rhythm in Bruckner’s Early Orchestral Scherzi.” In Bruckner Studies, edited by Timothy L. Jackson and Paul Hawkshaw, 278–97. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2001. “Musical Time in the Eighth Symphony.” In Perspectives on Anton Bruckner, edited by Crawford Howie, Paul Hawkshaw, and Timothy Jackson, 259–69. Ashgate Publishing.

Kurth, Ernst. [1925] 1991. Bruckner, vol. 1. Hesse Verlag. Part 2, Ch. 2 (“Die symphonische Welle”) edited and translated by Lee Rothfarb as Chs. 6 (“Bruckner’s Form as Undulatory Phases”) and 7 (“Details of Bruckner’s Symphonic Waves”) in Ernst Kurth: Selected Writings, 151–87 and 188–207. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 1997. “Some Aspects of Prolongation Procedures in the Ninth Symphony (Scherzo and Adagio).” In Bruckner Studies, edited by Timothy L. Jackson and Paul Hawkshaw, 209–55. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2001. “Continuity in the Fourth Symphony (First Movement).” In Perspectives on Anton Bruckner, edited by Crawford Howie, Paul Hawkshaw, and Timothy Jackson, 114–44. Ashgate Publishing.

Lindberg, Kai. 2003. “Anton Bruckner: The Finale of the Fourth Symphony (1889 Version).” In A Composition as a Problem III: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Music Theory, Tallinn, March 9–10, 2001, edited by Mart Humal, 52–63. Scripta Musicalia.

—————. 2014. “Aspects of Form and Voice-Leading Structure in the First Movements of Anton Bruckner’s Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, and 3.” Ph.D. diss., University of the Arts Helsinki.

Oster, Ernst. 1966. “Mozart, Menuetto K.V. 355: A Schenkerian View.” Journal for Music Theory 10 (1): 32–52.

Phillips, John A. (ed.). 1999. Bruckner Sämtliche Werke B, Band IX/4: IX. Symphonie d-Moll, Finale (Unvollendet), Dokumentation des Fragments. Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag der Internationalen Bruckner-Gesellschaft Wien.

—————. 2001. “The Facts behind a ‘Legend’: The Ninth Symphony and the Te Deum.” In Perspectives on Anton Bruckner, edited by Crawford Howie, Paul Hawkshaw, and Timothy Jackson, 270–81. Ashgate Publishing.

Pomeroy, Boyd. 2011a. “Bruckner and the Art of Tonic Estrangement: The First Movement of the Seventh Symphony.” In Johannes Brahms und Anton Bruckner im Spiegel der Musiktheorie: Bericht über das Internationale Symposium St. Florian 2008, edited by Christoph Hust, 147–75. Hainholz Verlag.

—————. 2011b. “The Major Dominant in Minor-Mode Sonata Forms: Compositional Challenges, Complications, and Effects.” Journal of Schenkerian Studies 5: 59–103.

Puffett, Derrick. 1999. “Bruckner’s Way: The Adagio of the Ninth Symphony,” edited by Kathryn Bailey and William Drabkin. Music Analysis 18 (1): 5–99.

Ramirez, Miguel. 2013. “Chromatic-Third Relations in the Music of Bruckner: A Neo-Riemannian Perspective.” Music Analysis 32 (2): 155–209.

Raynor, Henry. 1955. “An Approach to Anton Bruckner.” The Musical Times 96 (2): 70–74.

Röder, Thomas. 2001. “Master and Disciple United: The 1889 Finale of the Third Symphony.” In Perspectives on Anton Bruckner, edited by Crawford Howie, Paul Hawkshaw, and Timothy Jackson, 93–113. Ashgate Publishing.

Rothstein, William. 2016. Review of Piano Sonata in E Major Op. 109. Beethoven’s Last Piano Sonatas: An Edition with Elucidation by Heinrich Schenker, translated, edited, and annotated John Rothgeb; Piano Sonata in Major Op. 110. Beethoven’s Last Piano Sonatas: An Edition with Elucidation by Heinrich Schenker, translated, edited, and annotated by John Rothgeb; Piano Sonata in C Minor Op. 111. Beethoven’s Last Piano Sonatas: An Edition with Elucidation by Heinrich Schenker, translated, edited, and annotated by John Rothgeb; Piano Sonata in A Major Op. 101. Beethoven’s Last Piano Sonatas: An Edition with Elucidation by Heinrich Schenker, translated, edited, and annotated by John Rothgeb. Music and Letters 97 (4): 661–63.

Schachter, Carl. 1983. “The First Movement of Brahms’s Second Symphony: The Opening Theme and Its Consequences.” Music Analysis 2 (1): 55–68.

—————. 1987. “Analysis by Key: Another Look at Modulation.” Music Analysis 6 (3): 289–318.

Schenker, Heinrich. (1905–1909) 2005. “Über den Niedergang der Kompositionskunst: eine technisch-kritische Untersuchung.” Unpublished. Edited and translated by William Drabkin as “The Decline of the Art of Composition: A Technical-Critical Study.” Music Analysis 24 (1–2): 33–232.

—————. [1906] 1954. Harmonielehre. J.G. Cotta Verlag. Edited by Oswald Jonas and translated by Elisabeth Mann Borgese as Harmony. University of Chicago Press.

—————. 1918–1919. “Lessonbook: [Hans] Weisse: 1918/19.” Oster Collection 3/3. Transcribed by Robert Kosovsky and translated by Sigrun Heinzelmann. In Schenker Documents Online, edited by Ian Bent and William Drabkin.

—————. [1930] 1997. “Beethovens Dritte Sinfonie zum erstenmal in ihrem wahren Inhalt dargestellt.” In Das Meisterwerk in der Musik III. Drei Masken Verlag, 29–101. Translated by Derrick Puffett and Alfred Clayton as “Beethoven’s Third Symphony: Its True Content Described for the First Time.” In The Masterwork in Music III, edited by William Drabkin, 10–68 and 80–115. Cambridge University Press.

—————. [1935] 1979. Der freie Satz. Universal Edition. Translated and edited by Ernst Oster as Free Composition. Longman Press.

Straus, Joseph N. 2011. Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music. Oxford University Press.

Swinden, Kevin. 2004. “Bruckner and Harmony.” In The Cambridge Companion to Bruckner, edited by John Williamson, 205–28. Cambridge University Press.

Tovey, Donald Francis. 1935. Essays in Music Analysis, vol. 2: Symphonies, Variations and Orchestral Polyphony. Oxford University Press.

Venegas, Gabriel. 2017. “Anton Bruckner’s Slow Movements: Dialogic Perspectives.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Arlington.

Webster, James. 1978. “Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity.” 19th-Century Music 2 (1): 18–35.

Weiss, Herman Robert. 1988. “Cadencing and Voice Leading in Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony.” Ph.D. diss., Brandeis University.

Zuckerkandl, Victor. 1959. The Sense of Music. Princeton University Press.

Footnotes

* I am exceedingly grateful to Robert Cuckson and William Rothstein for refining my ideas about Bruckner; to Hedi Siegel, David Loeb, Poundie Burstein, Joseph Straus, and Carl Schachter for helping me to communicate them; and to Christina Lee, Yuval Shapira, Timothy Mastic, Nicholas Betson, and Megan Lavengood for informal discussions of difficult issues. Jeffrey Hodes helped me write code to digitize my musical examples. Earlier versions of this article were read in 2013 at the Mannes in-house symposium (Papier-Mâché) and in 2014 at the Third Graduate Student Conference at Mannes College, the Annual Research Symposium at Indiana University, Approaches to Analysis and Interpretation at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, the First Annual Graduate Student Conference at Temple University, and the annual meetings of Music Theory Southeast and the New England Conference of Music Theorists. My thanks as well to those who commented on my paper at these events, and to the reviewers and staff at MTO.

Return to text

1. Several authors explicitly forego traditional tonal analysis of Bruckner because they believe the music to obey a different logic. These include: Horton (2004b, 160), Puffett (1999, 8–11), and Weiss (1988, 44–45). See the following decidedly non-prolongational graphs: Horton 2004b, 51–53, 81, 87, 116–41, 206–9, and 253; Puffett 1999, 51–99; and Benjamin 1996, 243, 249, and 251. Analysts may also implicitly deny Bruckner’s music a tonal basis by eschewing Schenkerian means for approaching the analysis. This seems to be the stance taken by Benjamin Korstvedt (2001, 188–99). Following Kurth, he provides graphs of “harmonic frameworks” without indicating voice-leading relations, implying that he finds tonal governance to operate more loosely in this music than in the tonal canon: “Bruckner’s harmonic style, with its range of modulation, its complex sonorities, and its rich chromaticism, mitigates against the establishment and maintenance of two tonal poles” (188). Instead, Korstvedt finds a substitute in “what Carl Dahlhaus termed ‘centripetal harmony’: open-ended harmony that strives to reach an ‘unheard’ tonal center, the absence of which constitutes a structural dissonance” (190–91). And Kevin Swinden (2004, 206) and Miguel Ramirez (2013, 160) have argued for a sort of patchwork containing both Schenkerian and neo-Riemannian elements.

Return to text

2. See also Jackson’s Examples 8.8–9, which show a long Anstieg to a Kopfton in m. 39 that lacks harmonic support (2001, 223); and his “augmented [triad] reading” for the finale of the Seventh Symphony (1997, 189).

Return to text

3. Laufer takes a similar approach to the Adagio of the Ninth Symphony (1997, 248). Here he is more explicit about the music articulating a structural descent after the Anstieg. It does not seem unreasonable to observe that Laufer appears to regard the Anstieg as even more form-generating than interruption in Bruckner’s music.

Return to text

4. See also Ramirez 2013, 159 for an excellent distillation of the problem.

Return to text

5. I should mention that a few of these authors occasionally display some misprision in one way or another of the Schenkerian project (see for instance Puffett 1999, 12). But there are some noteworthy exceptions; in particular Joseph Kraus (1997; 2001), Kai Lindberg (2003; 2014), and Boyd Pomeroy (2011a) have rendered Bruckner’s voice leading more conservatively. Pomeroy views the Schenkerian approach as a valuable tool for Bruckner analysis, but questions its total applicability: “Bruckner did indeed compose in a different way from Schenker’s 19th-century exemplars of the art of Auskomponierung” (2011a, 154). Unlike Pomeroy, I believe that Bruckner does string together structural middleground harmonies with tonal voice leading—Lindberg agrees (2014, 194). However, this determination can only be made by a very thorough examination of Bruckner’s foregrounds; in that respect, the present study represents only a first step.

Return to text

6. See [Jonas and Salzer] [1937] 1989: “und er [Schenker] kannte wirklich jeden Takt jeder Scarlatti-Sonate auswendig bis ins letzte, ebenso wie jeden Takt jeder Brucknersymphonie!” (17).

Return to text

7. Schenker’s love/hate relationship with Bruckner permeates his work from his years as a critic in the 1890s all the way until Der freie Satz (1935). Many of these writings are excerpted by Jonas in Der Dreiklang ([1937] 1989, 166–76); and Federhofer reprints in full Schenker’s reviews (in Die Zukunft and Die Zeit) from 1893 and 1896 (1990, 41–42, 57–61, and 197–205). Although Schenker admired Bruckner—and, in spite of his technical flaws, considered him a far greater composer than those who succeeded him—he seemed determined to offer his music as Gegenbeispiele in all three volumes of Neue Musikalische Theorien und Phantasien. In fact, the third volume—which ultimately became Der freie Satz—was originally meant to be a lengthy polemic against, among others, Bruckner; this polemic survives as “Über den Niedergang der Kompositionskunst” (quoted above). Schenker’s opinion of Bruckner is well captured by Laufer (1997, 209–11) and Pomeroy (2011a, 153–54). Drabkin reprints the only sketch Schenker is known to have made of a Bruckner piece, the Scherzo of the Third Symphony (2011, 48–49).

It is productive to consider Schenker’s assessment (“ein Potpourri von Exaltationen”) alongside that of his contemporary, Ernst Kurth. What Schenker criticized as a collection of well-written but disunified fragments—“leaping from peak to peak” ([1905–1909] 2005, 117)—Kurth praised, calling them “symphonic waves” (symphonische Wellen) and emphasizing that they embodied true organicism in their growth and succession ([1925] 1991, 279–355). To be sure, the divergence of their opinions about Bruckner largely stems from the fact that Schenker was more concerned with matters of tonal cohesion, Kurth with principles of energetics.

Return to text

8. An excellent overview of Bruckner’s general sonata-form practices can be found in Korstvedt 2004, 175–76.

Return to text

9. Specifically, Bruckner’s view of the exposition is simpler because it does not consider a modulating transition to constitute a separate section. See Hooper 2011: “Whereas Marx (1837–47), Lobe (1850), and Richter (1852) include a transition after the primary theme, thus resulting in a four-part exposition (i.e., using Lobe’s terms: Themagruppe-Übergangsgruppe-Gesanggruppe-Schlussgruppe), the exposition in Bruckner’s own conception of sonata form has only three parts: Eingangsperiode-Gesangsperiode-Schlußperiode und Anhang” (52). Korstvedt emphasizes the tremendous consistency of Bruckner’s sonata-form practices, calling them “highly characteristic” (2004, 175).

Return to text

10. A.W. Ambros in the Wiener Abendpost (October 28, 1873), quoted in Korstvedt 2004, 170. Along the same lines, Max Kiel wrote a 1902 essay entitled “Ist Bruckner Formlos?”

Return to text

11. From Hanslick’s Neue freie Presse review of “Um Mitternacht,” WAB 90 and of the String Quintet, WAB 112 (February 26, 1885). Hanslick’s views and language formed the nucleus around which the late nineteenth-century Brahmsian reception of Bruckner crystalized. Schenker’s opinion of Bruckner appears to be steeped in Hanslick’s rhetoric; indeed, Hanslick’s review, quoted above, could easily have been written by Schenker. But on the other hand, Schenker was by no means just another Viennese critic parroting the jargon of the Brahms camp; he (not modestly) deemed his own musical understanding incomparably superior to Hanslick’s, which perforce rendered his judgments all the more considered and nuanced, despite the external similarities (Rothstein 2016, 662).

Return to text

12. The “alienated” secondary theme zone is one of seven deformational types Darcy enumerates. He also theorizes a narrower sort of alienation that refers specifically to the relation between the key of the second theme and the harmony that prepares it. Although this discussion (1997, 272–74) is among the most valuable in his essay (and to my knowledge has not been built on by more recent writings), it does not directly concern our topic here.

Return to text

13. In Darcy’s conception, the tonal alienation of the key design is intertwined with the sort of expressive alienation the themes evince: “If the movement is playing out a minor-mode redemption paradigm, the secondary zone presents, in effect, a visionary world—perhaps Utopian, Arcadian, or eschatological—but in any case, an alternative world which, Bruckner seems to say, cannot possibly be realized in the here and now” (274). For Pomeroy, speaking about the Eighth and Ninth Symphonies’ first movements, the effect is of “idyllic transience and unsustainability” (2011b, 91). Although Korstvedt rejects Formenlehre approaches to the symphonies (2001, 186), he seems to share Darcy’s sense about Bruckner’s second themes. In reference to the Sixth Symphony’s first movement, he writes: “the second theme group

This idea of “alienation” seems to have been imported from the Schubert literature, where it has long been a common trope. For one (early) example out of many, see James Webster’s groundbreaking 1978 article “Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity”: “No earlier composer introduced such songful, almost otherworldly second themes into a sonata-form movement as Schubert” (20). And later: “Schubert places the second theme outside the dominant much more frequently than any earlier composer, and the correlation between his remote flat-side tonal relations and his lyrical second themes seems to be no accident. Both spring from a contemplative rather than an active, a self-contained rather than a dynamic rhythm” (24).

Return to text

14. Many of these concepts saw great refinement in the dozen years between Darcy’s authorship of “Bruckner’s Sonata Deformations” (1997) and the publication of Elements of Sonata Theory (2006). (My thanks to James Hepokoski for his helpful comments on these matters.) In the latter, the blanket label “deformations” is replaced with a three-tiered system of norms, lower-level defaults, and deformations (this last term reserved for only the most novel formal choices). The scope of these categories is dialogically conditioned, meaning that they adapt to changes in stylistic expectation. The “alienated secondary theme zone” does not exist in Elements of Sonata Theory’s treatment of the exposition. (It can exist in the recapitulation; see 2006, 245–47). However, the central idea underlying Darcy’s (1997) concept of “tonal alienation” in the exposition does survive in several Sonata Theory constructions, two of which are especially pertinent to the treatment of Bruckner’s second themes. One explicitly nineteenth-century option, an “S—SC” configuration, reads a dramatic break-down of the second theme, leading to a redemptive third theme. This idea was advanced by Hepokoski and Darcy (2006, 191) and considered at length by Betson (2012). Or, perhaps more traditionally, one might designate the second and third themes as “TM1” and “TM3” respectively within a “trimodular block.” (See Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 170–77.) By definition, these constructions view Bruckner’s second themes as unsuccessful and “wrong” because they fail to cadence in some key: “The purpose of S within the exposition is to reach and stabilize a perfect authentic cadence in the new key” (2006, 177). Thus, although Darcy’s concept of expositional alienation is not retained by Sonata Theory, the same ideas remain implicitly foundational to its approach.

Return to text

15. Certainly, few of these movements display a truly normal approach to sonata form. And as such, in Darcy’s (1997) terms they are indeed deformational. But I would question the extent that a sonata is “deformed” when so many examples feature so wide a range of irregularities. Rather, I prefer to think of these cases as inevitable outgrowths from a ‘path of least resistance’ determined by tonal voice-leading eventualities (such as the gravitation towards V in major, III in minor). Composers can and often do choose to follow a more difficult voice-leading path, testing the cohesive mettle of a naturally elastic medium. When they do so, they often create an excitation of the middleground voice leading that has dramatic implications in the foreground.

Return to text

16. Horton has considered the problem of nineteenth-century Formenlehre at length. Although his argumentation follows a different track than mine, his conclusion is similar: “the evidence for a body of work that fulfils rather than distorts the Formenlehre model (whatever that may be) remains patchy. It is, in truth, hard to find a canonical nineteenth-century sonata form that does not in some sense deviate from the models of Reicha, Marx, or Czerny” (2005, 10). As such, the proclivity of even the most broadly conceived Formenlehre model to oversimplify is hard to overcome; and thus in my view, Darcy’s Bruckner emerges too modern because his foils are too traditional.

Return to text

17. While I do choose in Example 1 to designate all of these dominants as structural in the deepest sense, I should hasten to add that they need not be read as such. For minor-mode movements whose expositions contain major dominants (i.e., the finale of the Third Symphony and the opening movements of the Eighth and Ninth), we could just as easily regard these dominants as Teilers—local expansions of the tonic through its upper fifth that are “back-relating” in the sense that they do not resolve to the final tonic. Pomeroy graphs the first movement of Bruckner’s Ninth in exactly this way (2011b, 92–93). This question cannot be treated briefly (especially with regard to the problematic Third Symphony finale), but it is of small consequence to my larger argument. Suffice it to say that I am inclined to treat all of Bruckner’s minor-mode expositional dominants as structural because of the analogy with his major-mode sonata forms. To regard dominants in minor as back-relating but dominants in major as structural is to conceive of the minor-mode symphonies as fundamentally different in construction from their major-mode siblings. I believe Bruckner most often operated according to the opposite principle, that of blurring the distinction between minor and major modes. Specifically, I read these dominants as generating the development section through a V—III—I arpeggiation, a technique pioneered by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven (Beach 1983; Schachter 1987, 296–98) and greatly favored by Bruckner.

Return to text

18. I will not discuss the exposition of the Fourth Symphony’s opening movement, for which see Laufer 2001, 116–28. I take different readings of several passages, but an approximate analogue to the level of detail I show in Example 4 can be found in his Example 36, page 128.

Return to text

19. The String Quintet follows this pattern as well. The second theme of its first movement is in the key of the dominant (m. 29), whereas the finale’s second theme is in the key of the leading tone (m. 33). The tonal plan of the Ninth Symphony’s finale is far harder to grasp because eight crucial measures in the development are missing. It is therefore impossible to tell whether the A major of m. 273 (the would-be structural dominant) is prolonged until m. 291, after which follows the retransition. However, the exposition survives intact and we can discern that it follows the same practice as Bruckner’s other finale expositions: the second theme (m. 83) is not in the dominant, but rather the major subdominant (G major). The exposition concludes in E minor (II) at m. 228. Crucial for developing an understanding of the finale—its compositional genius and the state of its sources—is the work of John A. Phillips. See in particular his 1999 performing edition and 2001 article.

Return to text

20. Other authors have presented descriptions or tables similar to my Example 1 (Darcy 1997, 272–74; Korstvedt 2004, 174). Yet the pattern has not emerged, I suspect, because they label key areas with letter names (e.g., D minor,

Return to text

21. I have found that there are surprisingly few real enharmonic shifts in Bruckner; usually the middleground behavior of chromatic notes allows a passage to be read either entirely in sharps or entirely in flats.

Return to text

22. Very few authors have considered the vast length of Bruckner’s symphonies from a theoretical standpoint. Korstvedt touches on the matter briefly, connecting “characteristic chromaticism, remote modulation, episodic formal approach, and expansive time scale” (2001, 195), but not making the point explicit. For similar observations, see Benjamin 1996, 237–38 and 253–54. Kraus, in the only extended treatment of time as a concept in Bruckner, attempts to uncover instances of what Jonathan Kramer has termed non-linear, multiply-directed, and vertical time (2001, 259–62). However, his focus and conclusions differ from mine.

Return to text

23. Dahlhaus provides a complementary perspective: “the shrinking of thematic material in inverse proportion to the ambition to create larger forms” led composers to rely on “real, modulatory sequence[s]

Return to text

24. What, then, of the numerous Scarlatti sonatas or Chopin mazurkas that behave quite oddly? I would guess that in a deeper sense, there is probably a difference in the way big and small movements deploy their chromaticism: that in large movements, a thread must exist that organically transfers chromaticism at fairly deep structural levels into the shallower levels, lest the foreground’s chromaticism seem haphazard or arbitrary—as if a late addition. When it is prepared in this way on deeper structural levels, the chromaticism tends to beget more chromaticism; and so the major chromatic events of a long movement are generally surrounded by others on the same voice-leading layer. In short pieces, however, the journey from background to foreground is more quickly accomplished, and there is less time to sprinkle and nurture chromaticism throughout the voice leading. As a result, it is more acceptable in short pieces for chromaticism to exist only on the shallowest layers, and what deeper chromatic events do exist are very often presented as singularities, without counterparts on their structural level. I hasten to add that these are provisional hunches that would require a great deal of research to substantiate—an avenue for future scholarship to be sure.

Return to text

25. See Tovey 1935, 77: “You must not expect Bruckner to make a finale ‘go’ like a classical finale. He is in no greater hurry at the end of a symphony than at the beginning.” Needless to say, I consider this a fundamental mishearing of the finales. Although none of Bruckner’s finales approaches a classical vivace or presto, he made all of them “go” at a considerably faster clip than their corresponding opening movements.

Return to text

26. As Carl Schachter notes (in reference to Brahms’s Second Symphony), “Such an explanation is preferable to one that merely names keys without trying to understand how they are connected” (1983, 62).

Return to text

27. To my knowledge, most of this material has not been analyzed graphically in prior scholarship. Foreground graphs of Bruckner are also quite rare. For voice-leading sketches of passages from the Third Symphony, see Horton 2004b, 51–53. For the Fourth, see Lindberg 2003, 54–62. For the Sixth, see Swinden 2004, 215–17. For the Seventh, see Jackson 1997, 188–89. And for the Eighth, see Horton 2004b, 87 and 140; Benjamin 1996, 239–45; and Ramirez 2013, 183–91.

Return to text

28. The finale of the Sixth Symphony provides an excellent illustration of how voice-leading agency—the tones themselves—can shape form. While the chromatic voice exchange to an augmented sixth is a typical voice-leading maneuver, it rarely occurs over such a protracted time span. This creates a need in the voice leading, one that Bruckner responded to on some level. By casting the second theme in C major (

Return to text

29. For reasons of space, I am not able to include very detailed prose explanations of the Appendix graphs, as I did for Example 3 above. I have provided only the most essential commentary, found in the boxed text surrounding the graphs. Clicking on blue asterisks will reveal the commentary. Clicking on green asterisks will reveal more figures. Here in the Appendix it seemed appropriate to use a wide array of analytic techniques—from figured bass or metrical reductions, to layered contrapuntal sketches, to middleground and foreground voice-leading graphs. A note about terminology: I use the word “surface” to refer to a minute structural layer between the foreground and the composer’s score, a layer that has the same voice-leading dispositions as the score.

Return to text

30. For explicit discussions of the latter connection, see Webster 1978, 26–31; and Schachter 1983, 65–66. Works by Schubert that contain three-key expositions can be classified into two broad groups: those in which the second key areas are tonally open (well-known examples include the C major String Quintet, D. 956 and the

Return to text

31. See, for example, Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 177 (quoted above in n14); and Caplin: “Music in the classical style is often characterized as highly goal directed, and many of the principal goals in a composition are the cadences marking the ends of themes and themelike units” (1998, 42). Caplin discusses three-key expositions briefly, calling the term “somewhat of a misnomer,” because “in the classical style, the ‘second’ key, the one beginning the subordinate theme, is rarely confirmed as such by cadential closure” (1998, 119).

Return to text

32. Schenker criticized this predilection of Bruckner’s in a sharply worded (and rather gratuitous) footnote from the section in Der freie Satz on auxiliary cadences: “Anton Bruckner was not capable of starting a musical thought, much less a whole first movement, with the aid of an auxiliary cadence. Thus the impression of a rigid succession of thought in his work: the ideas usually come in blocks, each one with a new tonic at the beginning” ([1935] 1979, 89). However, Schenker’s criticism is slightly misplaced: the first movement of the Eighth Symphony begins off-tonic. And almost all of Bruckner’s finales also begin with auxiliary cadences, as well as several of his third themes. Nevertheless, Schenker’s remark certainly holds true in regard to Bruckner’s second themes. Burstein discusses Schenker’s footnote as well, calling its “mean-spirited swipe” unjustified (2005, 168, fn 28).

Return to text

33. According to this more Schenkerian way of thinking, which privileges important tonal events with less regard to their precise formal function, a theme does not need to cadence in order to assert its key. This is surely true of the first theme in very many sonata forms, and for Bruckner (and oftentimes for Schubert and Brahms as well) it is also true of the second theme.

Return to text