Schubert’s Development of Harmonic Motives in his Early String Quartets

Brian C. Black

KEYWORDS: Franz Schubert, harmonic motive, sonata form, string quartet, three-key exposition, deflected cadence strategy, William E. Caplin, theory of formal functions

ABSTRACT: This essay looks at Schubert’s handling of harmonic motives in the first movements of four of his early string quartets dating from the period of approximately 1811 until late 1814, when he was fourteen to seventeen years old. Despite their many structural problems, these pieces provide an insight into Schubert’s development as a composer of sonata form. Even in the earliest of the examples studied, the young composer attempts to draw affective and structural consequences across the form from the first harmonic event of the music, which thus functions motivically in the unfolding of the movement. As his approach becomes increasingly flexible over the period under discussion, such harmonic motives become a dynamic force in the form, influencing tonal relations and modulatory strategies as well as looking forward to certain aspects of his mature three-key expositions.

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

[1] While some aspects of Schubert’s instrumental music have been the subject of controversy over the last century and a half, his innovative approach to harmony has been widely admired.(1) One feature of this approach in particular—his use of harmonic motives—has gained a fair amount of attention in the last few decades. By “harmonic motive,” I mean a harmonic event or progression that resonates across the movement and influences its key relationships, modulatory strategies, and affective atmosphere. This recurring entity thus has a motivic status in the full sense of the word. It originates often in the first gesture of the movement and is pursued throughout the piece to become not just a subtle unifying element, but something that contributes to the overall meaning and effect of the music.

[2] Schubert’s manipulation of harmonic motives has been recognized in his mature music for some time now, from harmonic cross references, such as E.T. Cone’s “promissory note” or James Webster’s “sensitive sonority,”(2) to larger progressions as in Ivan Waldbauer’s (1998) “recurrent harmonic patterns.” Such procedures, however, were not a late development in his writing. They may be seen in many of his earliest string quartets, the body of work that will form the main focus of the present article. The principal aim of this study is to trace the development of Schubert’s use of harmonic motives in works from the very beginning of his engagement in large-scale instrumental composition and thus establish continuity with the works of his maturity.(3) The music studied here consists of the first movements of four of Schubert’s early quartets, D. 94 in D major and D. 36, 68, and 112, all in

The Problematic Aspects of the Early String Quartets

[3] The early quartets are among the first instrumental works Schubert composed. They occupy the period from roughly 1810, when he was thirteen, to 1816, when he was on the verge of a career as a free-lance composer. The overall structures of many of the first movements in these quartets show serious problems in large-scale design with respect to the norms of sonata form, especially in establishing a subordinate theme and key in what would be the exposition.(4) The earliest movements are marked by a tightly controlled and uniform motivic make-up that does not admit conventional tonal and thematic contrast in the first part of the form. In short, there is no subordinate key or theme, and the music is dominated by one basic motivic idea to the exclusion of virtually anything else.(5) The main line of development in the subsequent quartets from 1812 on is the gradual generation of both a contrasting key and theme in this section of the form; until in the String Quartet in B-flat major, D. 112, from September of 1814, we have a first-movement sonata form that is not only convincing as a structure but also wholly idiosyncratic in its handling of the

[4] Even in the very first quartet movements a striking harmonic feature of the opening idea assumes an important role in the form and is encountered repeatedly throughout the movement. What constitutes this feature varies in the movements under study. In D. 94, it is the contrast between the tonic and submediant chords, which is expanded into the contrast between the two tonal realms of the major and relative minor. In D. 36, it is the partial sequence of an ascending second, which plays a role in the movement’s principal modulations. Finally in D. 68 and 112, it is a particular chord progression, which underpins large sections of the form. In all cases the marked harmonic element accomplishes the important functions of harmonic motives—modulatory, referential and gestural—that I have identified elsewhere in Schubert’s mature sonata forms.(7) We will deal with these functions and how they are carried out in each case in the following discussion.

[5] The variety of the harmonic material Schubert uses in these movements and his handling of it reflect the experimental nature of the music in this stage of his career and his innovative spirit. It is often the single-minded pursuit of this material that creates such unusual and problematic structures.(8) In fact, Schubert’s handling of harmonic motives across the years studied in this article is closely related to the general development of his first-movement form. In the earliest stages the harmonic motive is associated with literal returns of the main melodic/motivic material. Gradually, however, a more fluid approach emerges, one in which the harmonic motive gains its independence from its original melodic configuration and becomes a substance that can be molded into different shapes for different form-functional contexts. Thus by the first movement of D. 112, where Schubert achieves both tonal and thematic contrast in the exposition, the main and subordinate themes exhibit rhythmic, melodic, and affective differentiation, while sharing a common harmonic background. Here the situation looks forward to the construction of the first movement of the late Piano Sonata in A major, D. 959, as identified by Ivan F. Waldbauer 1998, wherein the main and subordinate themes are variations on the same harmonic progression. To begin our investigation we will now turn to one of the earliest string quartets—D. 94, in D major, from either late 1811 or early 1812.(9)

D. 94 and the Emergence of a Harmonic Motive

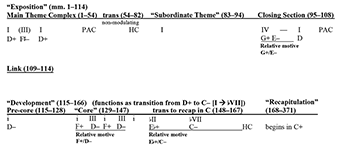

Example 1a. String Quartet in D major, D. 94, i; form of “exposition” and “development”

(click to enlarge)

Example 1b. Main theme complex and relative motive

(click to enlarge)

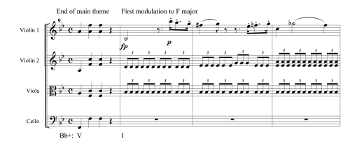

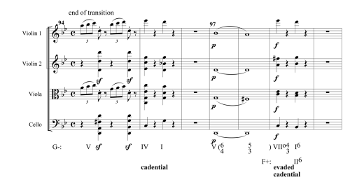

[6] The first movement of this quartet is very unusual with respect to its overall structure (see Example 1a and 1b).(10) Its basic subdivisions suggest an attempt at a sonata form, but they do not fulfil the respective functions found conventionally in such a form.(11) The “exposition” remains in the tonic, although it does feature a non-modulating transition followed by a new theme that begins in the tonic, feints towards the dominant (measures 87–91), then returns to the tonic (measures 92–94).(12) The “development” modulates from the parallel minor of the tonic (D) to its subtonic, C major. The “recapitulation” first establishes C major as a competing tonality. It is then dominated by a struggle between C and D major, with D major winning out shortly before the closing section/coda. Essentially the unusual features of the movement result from Schubert’s failure to establish a subordinate key in the “exposition.” The modulation to a contrasting key is thus displaced to the “development,” which now fulfills the function of a transition, while both the confirmation of the contrasting key and the return to the tonic must occupy the “recapitulation.”(13)

Example 2. String Quartet in D major, D. 94, i, main theme complex, mm. 1–17

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[7] The surface of the movement divides into intensely lyrical thematic material derived from the main theme complex and unsettled transitional material, which is often launched by a fanfare motive (measures 54–82). The lyrical quality of the thematic material is largely due to its characteristic harmonic motive, which consists of the contrast between the tonic and submediant chords as established in the main theme’s two presentation phrases (Example 2, measures 1–11). In this first statement of the motive, Schubert marks the move from I to VI as something striking: each harmony is prolonged for four bars as a static harmonic block involving the chord and its dominant in alternation over the chord’s sustained root. This construction allows the particular quality of each chord, above all its specific modal color, to shine out. The move from one block to the next thus acquires more power than a simple change of chord within a harmonic progression; instead it creates the impression of a shift from one harmonic plane to another—and this effect is intensified in later statements of the motive.(14) In fact it is this chiaroscuro of major to relative minor or reversed from minor to relative major that becomes the main identifying effect of the motive. In such appearances, the motive fulfills a gestural function to mark the various stages of the form.(15) Since the motive implies the contrast between a major tonality and its relative minor or vice versa, I will refer to it as the “relative motive.”

Example 3a. String Quartet in D major, D. 94, i, main theme complex, excursion to

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

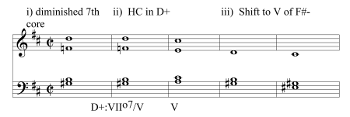

Example 3b. Shift to

(click to enlarge)

[8] The relative motive immediately returns in the second section of the main theme complex (Example 3a, measures 26–44), now in the dominant field, A major/

[9] In this

Example 4. String Quartet in D major, D. 94, i, end of “development section” / transition, modulation to C for “recapitulation,” mm. 146–73

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

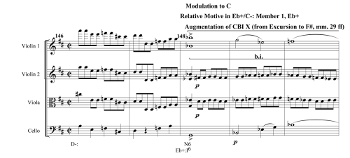

[10] In the central modulation to C major in the “development”/transition, the relative motive plays a dynamic role since it provides the mainspring for that modulation. The first part of the “development”/transition consists of an exploration of the relative motivic relationship now on the tonic minor D and its relative major F (measures 115–147), thus echoing the

[11] In this last instance, the tendency for the relative motive to suggest two tonal entities—the major and its relative minor—comes to full fruition as the music emerges from

[12] To summarize, the ubiquity and importance of the relative motive in the first movement of D. 94 is very evident. It is present in the opening measures of the main theme complex (in D major/B minor, measures 3–11), the complex’s internal excursion to

[13] In all of its recurrences the relative motive maintains the melodic material it was associated with in its initial statement—that is, the movement’s opening basic idea (measures 3–4), either repeated immediately or joined to the contrasting idea of CBI X.(19) In these appearances the relative motive plays two distinct roles. The first is gestural, in that the motive marks particular points in the form with a palpable, recurring affective atmosphere through its distinctive character. In D. 94 this character consists of what I referred to earlier as the chiaroscuro effect of the contrast between the tonic major and its relative minor, encapsulated in the modal difference between the tonic and submediant chords. In the first statement of the relative motive (measures 3–11), this contrast is heightened by maintaining

D. 36 and the Increasing Scope of the Harmonic Motive

Example 5. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge)

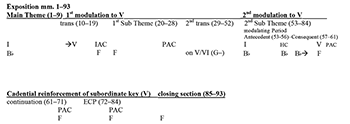

[14] The first movement of the String Quartet in B-flat major, D. 36 also presents an unusual structure in terms of sonata form. However, in comparison to D. 94 as well as to the other previous quartets, such as D. 18 and D. 32, it is marked by an important breakthrough: Schubert establishes both a distinct subordinate theme and key in the first part of the form, which I now label an exposition without qualification (see Example 5).(21) What creates the peculiarities in the form is the composer’s attempt to derive its principal material exclusively from its opening main theme.

Example 6. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge)

[15] The main theme itself is unusual. It consists of only four bars based on a statement-response design in which the basic idea of measures 1–2 is partially sequenced up a tone from tonic to supertonic in measures 3–4 (see Example 6). (22) A large portion of the movement is occupied with exact or varied repetitions of this four-bar unit, particularly in the exposition (see Example 5). Here the majority of the main-theme complex consists of contiguous statements of the main theme, either exact or varied (measures 5–20 and measures 32–41). The pattern is broken in measures 21–31, where a further variation of the main theme (measures 21–24) leads to a spinning out of its final motive (measures 25–27, etc.). This passage foreshadows the generation of the second subordinate theme (measures 56–64, etc.).(23)

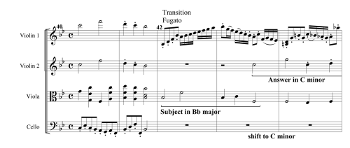

[16] The transition (measures 42–55) consists of a fugato on the basic idea of the main theme, which modulates from

[17] The exposition is the most complex part of the form, mixing monothematicism with a three-key design (

[18] The harmonic motive of the main theme consists of the partial sequence of measures 1–2 from the tonic,

Example 7. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[19] In the repetitions of the main theme during the course of the main theme group, the motive’s tendency to lean towards the supertonic is carefully contained within

Example 8. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge)

Example 9. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[20] So far all of the instances of the supertonic motive have been linked to appearances of the main theme or its components. At certain points, however, Schubert uses the motive in a less literal manner and without such a link. Here we turn to the conclusion of the second subordinate key area, F major, and the beginning of the development. References to the main theme in F major do not occur until the end of the exposition. In measures 83–87, a variation of the theme’s basic idea launches the concluding PAC of the second subordinate theme. This basic idea then becomes the codetta material for the closing section (measures 87–91). In both passages the supertonic motive is conspicuously absent. This is understandable since, as a dynamic and thus unsettling element of the movement’s opening thematic material, the motive is inappropriate at this stage of the form where F major is stabilized and confirmed as the concluding subordinate tonality of the exposition. Schubert, however, uses the supertonic motive on a broader scale to launch the development section, which begins with a direct move from F major, to its supertonic, G minor through the latter’s dominant (Example 8, measures 91–92b).(27) The development section’s retransition answers this ascending step from the dominant, F, with a sequential descent by step to the tonic ![]()

![]()

[21] In summary, D. 36 is dominated by its supertonic motive, which fulfills both a gestural and a modulatory role in the form. In the latter case, a major portion of local and broader tonal motion in this piece consists of direct movement by a major second. In most instances, the originating material of the main theme, specifically a sequence of its basic idea, is directly involved. Those instances where such a direct involvement is not present, however, as in the development section, represent something new in Schubert’s handling of harmonic motives, which becomes increasingly evident in the subsequent quartets.

D. 68 and Increasing Flexibility in Handling the Harmonic Motive

Example 10. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge)

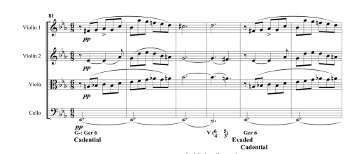

[22] In the next example, the first movement of the String Quartet in B-flat major, D. 68, from the summer of 1813, Schubert continues to treat harmonic motives with the flexibility we found in the development section of D. 36. While the use of harmonic motives is quite ingenious in D. 68, the movement’s structure is one of the most perplexing in all of the early string quartets.(29) This is true specifically of the exposition, which twice modulates to and cadences in the dominant key (see Example 10).

[23] The first part of the exposition consists of an unconventional main theme ending on the dominant (measures 1–9); a periodic hybrid structure modulating to the dominant key, F major, followed by two bars of prolongation of the new tonic (measures 10–19);(30) and a subordinate theme-like section in F, concluding with a PAC (measures 20–29, labeled 1st sub. theme in Example 10). The impression of a concise exposition to this point then disappears in a sudden turn to the dominant of G minor (measures 29–30); its prolongation (measures 31–52); and a second theme-like structure (a modulating period, labeled 2nd sub theme in Example 10), which begins back in the tonic and finally cadences in the dominant key (measures 53–60).(31) This key is reinforced by an unusual, harmonically complicated ECP (measures 72–84) and a closing section (measures 84–93). The remarkable exposition is followed by a short development section and a recapitulation that brings all of the non-tonic material of the exposition into the tonic. Thus, the overall form is conventional, despite the exposition’s highly unusual structure.

[24] What Schubert has done in the exposition is expand the transitional process across the whole core of that section. The abrupt, early modulation to the dominant is denied by the sudden move to and prolongation of the dominant of G minor. The second subordinate theme then returns unexpectedly to the tonic and replays the original modulation to the dominant, which is cadentially confirmed and further strengthened in the concluding passages of the section. The modulatory process thus runs across usually discrete sections, such as the subordinate theme area itself. Many of the resulting anomalies, however, can be understood in relation to how Schubert concentrates on and develops the harmonic material of the main theme.

Example 11. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

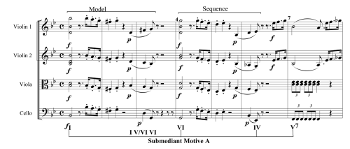

[25] The principal harmonic motive of the main theme consists of the large-scale progression I–VI–IV–V underpinning the theme as a whole (Example 11).(32) The most striking aspect of this motive is the initial move to the submediant through its applied dominant. This tonicization serves as a prominent marker. Thus, the full progression will be referred to as “submediant motive A.” In the main theme, the opening I–VI move is immediately sequenced down a third from VI to IV. The internal move to IV is not a defining element of the progression, however, for II or its major inflection, the V of V, are substituted for this harmony in later statements of the motive (submediant motive A1 and A2 respectively). This substitution allows for the motive to be used more flexibly in the form—specifically for situations involving a modulation to the dominant, which is accomplished by A2 (see below).

Example 12. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[26] A major portion of the exposition is made up of statements of the submediant motive. The first modulation to F, immediately following the main theme, is built on the A2 version, in which the music pivots on VI into the dominant key (Example 12, measures 14–18).(33) In this statement of the motive, the initial tonic is prolonged by the ![]()

![]()

Example 13. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[27] The submediant motive, both in its A1 and A2 form, also provides the harmonic foundation for the second subordinate theme (measures 53–60). The situation here is unusually complex and represents one of the most striking anomalies in the movement. The theme, a modulating period, enters in the home key of

[28] This scenario employs the harmonic elements of the submediant motive A on both the broad and local level. The initial move to the submediant through its dominant in the first bars of the main theme predicts the important role G minor and its dominant will play in the overall structure of the exposition. On the local level, the submediant motive appears in new guises at virtually every major stage and every level of the exposition, providing the material for all of the thematic units and the two modulations to F.

Example 14. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[29] The motive’s shift to the submediant constitutes a dynamic element in the form. In the exposition, it is emphasized because it provides the motor, so to speak, for the modulations to F, as that modulation’s crucial pivot chord. In the recapitulation, though, where maintenance of the focus on the home key is required, certain adjustments are necessary, above all in the material of the second subordinate theme (Example 14). Since this subordinate theme begins in the home key in the exposition, it can, and does, return at its original pitch in the recapitulation. Its consequent phrase, which modulated in the exposition, must then be altered to remain in

[30] In the first place, the arrival of the theme is prepared by the dominant of the home key, not that of the submediant. The theme’s antecedent matches such a regularization with one of its own: instead of beginning with the I–![]()

[31] Apart from the flexibility in Schubert’s handling of his harmonic material, there are two striking features of the movement that need to be addressed: the extremely long and complex modulatory process and the unusual effect of the arrival of the second subordinate theme. The two are linked together. Most of the interior of the exposition is taken up with a long prolongation of the dominant of G minor. This reference to G minor is itself motivic, being a characteristic element of the submediant motive throughout the movement. It also sets up the entrance of the second subordinate theme as a special surprise event, in which the opening D of the theme is imbued with an unexpected color in

D. 112: Schubert’s Handling of the Harmonic Motive and the Achievement of a Personal Style

[32] The B-flat major Quartet, D. 112, from September of 1814, is one of the finest of Schubert’s early quartets. In many respects its first movement represents a continuation and refinement of the processes encountered in D. 68. As in D. 68, the harmonic motive consists of the underlying chord progression of the main theme, which is then developed as the prime harmonic material of the whole movement in a manner that exhibits flexibility in moulding the material into new configurations. Furthermore, the same tonal relationships—between the tonic,

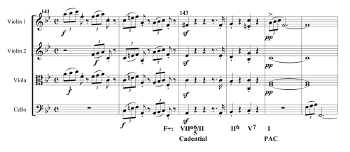

[33] Unlike D. 68, the harmonic motive of D. 112 does not fulfill an explicit modulatory function in that it does not provide the direct means of modulation to the subordinate key. Instead, its role is more referential.(36) By this term, I mean that the prominent melodic element of the motive in its first statement gradually increases in its significance from a melodic, to a harmonic, and then a tonal element in the unfolding of the form and references to this element at various stages help to define the tonal hierarchy of the movement. This is an important feature of Schubert’s handling of sonata form in his maturity.(37)

[34] In its referential capacity, however, the harmonic motive of D. 112 is still involved in the modulatory scheme, specifically as part of an innovative means of modulation I have referred to in previous articles as a “deflected-cadence” strategy (Black 2009, 2015). This is a procedure with an effect similar to the tonal feint discussed in D. 68, but involving paired cadences, in which a cadence is set up in one key, evaded or denied, and then started again, only to be deflected at the last moment into a new key. Again, this is a prominent feature of Schubert’s mature works.(38) D. 112 presents one of the first instances of its use in his instrumental music. The main focus of the following discussion shall thus fall upon the modulatory process and its relation to the harmonic motive in its referential role. We will begin by laying out the overall form of the music. Then we will define the harmonic motive and track its recurrences across the movement.

Example 15. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge)

[35] The structure of the movement’s exposition is somewhat unusual (see Example 15). This part of the form breaks into three distinct blocks, each contrasting in character yet dominated by the same harmonic background derived from the main theme and featuring long tonic pedals or prolongations. These blocks consist of the main theme (measures 1–34), an extensive and dramatic transition (measures 35–102), and the subordinate theme with its closing section (measures 103–156). The move from one block into the next is achieved by an intricate passage involving interlocking cadences. This passage launches the transition and returns to prepare the beginning of the subordinate theme. It is in both (1) the broader relationship of the two cadential passages framing the transition and in (2) the interlocking cadences preparing the subordinate theme that Schubert uses the deflected-cadence strategy mentioned above.

Example 16a. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 16b. The three forms of the supertonic

(click to enlarge)

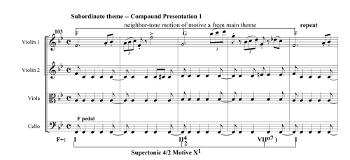

[36] The harmonic motive of the main theme grows out of the initial melodic gesture of the movement—the expanded F–G–F neighbor-tone figure presented in measures 1–3 and labeled “motive a” (Example 16a). This gesture saturates the main theme, where it is repeated first on the mediant degree (measures 4–6), then on the tonic (measures 7–13). In the concluding tonic statement, the figure’s underlying harmonic background, a I–![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Example 17a. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 17b. Interior of transition, segment in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[37] In the exposition of D. 112, the supertonic ![]()

![]()

Example 18. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[38] In the subordinate theme—a compound sentence—the first compound presentation is also built on the supertonic ![]()

[39] The short development section that ensues concentrates on the second compound presentation phrase of the subordinate theme. Thus, this part of the form is saturated with the supertonic ![]()

![]()

[40] One of the most impressive moments in the first movement of D. 112 is the arrival of the subordinate theme in F major in the exposition (measure 103). The unusual effect of this moment looks forward to the striking and innovative character of Schubert’s mature modulatory strategies, specifically those that create an entirely new atmosphere for the new theme. The modulatory scheme in D. 112 that creates this effect is quite complex, even convoluted, yet it is tied in motivically to the principal element of the supertonic ![]()

Example 19a. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[41] The transition itself (measures 35–105) is not only extensive but also unusual in its construction and general character.(43) It begins with an abrupt and direct move to the submediant, G minor, from the concluding

Example 19b. Interlocking cadences at the end of the transition, mm. 94–103

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[42] The PAC in G minor launches an extremely dramatic and unsettled section of music first in G minor (measures 45–70), then shifting back to

Example 19c. Cadential strategy of the transition with its G-

(click to enlarge)

[43] Essentially the modulation may be reduced to the transition’s beginning and end points, the interlocking cadences between measures 35 and 45, which initiate the move from

[44] This complex plan is derived motivically from the opening gesture of the main theme, the F–G–F neighbor-tone figure (Example 16a, measures 1–3, motive a). This figure is extremely important in the movement.(48) As mentioned above, it is the source of the supertonic ![]()

[45] The expansion of G, the central element of the F neighbor-tone figure, is extremely important in the modulatory scheme. The G minor ![]()

![]()

Example 20. String Quartet in

(click to enlarge)

[46] The G ![]()

The Early Quartets and Schubert’s Mature Three-Key Expositions

[47] In his influential article on Schubert’s sonata forms, James Webster, 1978 has drawn an interesting connection between the composer’s transitions and his three-key expositions, involving what Webster terms “double second groups”—a subordinate-theme region that is split between two keys and themes. The first key is often remote; the second is almost always the dominant. There are two possible types of construction. The first involves motion from an initial unstable key to a second subordinate key during the course of the first subordinate theme. A good example of this is the first movement of the String Quintet in C major, D. 956, where the first subordinate theme begins in

[48] In Webster’s thesis, the material of the first key in the double second group functions as a transition to the second key, despite its often intensely lyrical character.(52) According to him, this function is most obvious in those three-key expositions where the double second group begins with an unstable tonality, but he also sees the same underlying function in those cases where the first tonality is firmly grounded. Here Webster points out the dissociation between an apparently stable tonality and its tonal function as a transition, and isolates two idiosyncratic features of Schubert’s three-key expositions which undercut that stability: (1) the modulation to the first subordinate tonality often replaces the usual dominant preparation of the new key with an unconventional and abrupt move by common tone, juxtaposition of keys, or a tonal feint; (2) the home key maintains its presence until the last minute of the transition to the first subordinate key and is referenced again in the subsequent transition between the first and the second subordinate keys (1978, 23 and 30).(53)

[49] I disagree with Webster’s argument that the primary function of the first subordinate theme in a double second group is transitional. The situation is more complex in the mature three-key expositions and involves a tonal and thematic interplay across the exposition that marks the movement with its particular affective meaning. To confine the first subordinate theme to a predominantly transitional function thus seems to diminish its multifaceted role in the form. However, the last three quartet movements we have looked at, D. 32, D. 68, and D. 112, bear witness to a connection between Schubert’s later three-key expositions and his early experiments in the transitional modulatory process. This process, in fact, provides the proving ground for the specific features of the mature three-key expositions identified by Webster. And these features are in turn tied in to Schubert’s efforts to make the central harmonic motive of the main theme a generative force in the music.

[50] The most straight-forward example is D. 36. As mentioned earlier, this movement presents an early example of the first type of three-key expositions mentioned by Webster—one in which the initial key of the subordinate theme group quickly yields to the second key (see Example 7, page 2). Here the connection to Schubert’s transitional experiments based on the harmonic motive of the main theme is very clear.(54) The first subordinate key, C (measures 56–59), is a direct projection of the main theme’s supertonic motive onto the tonal level, while the main melodic material of the ensuing second subordinate theme is generated in the descending third sequence that leads from C to F major, the second subordinate key (measures 59–61). The whole process reflects the aim of the young Schubert to derive the entire movement from the melodic and harmonic material of his opening theme—a preoccupation that marks the first-movement forms of his early quartets up to this point as well.

[51] The situation in the other two quartet movements, D. 68 and D. 112, is more complicated as far as the modulatory strategy is concerned, but reveals similar connections between the experimental transitions in his early quartets and his mature three-key expositions. Unlike D. 36, neither case is a true three-key exposition where the first subordinate key marks the beginning of the first subordinate theme. Both D. 68 and D. 112 expand on an intermediate key (G minor) between the tonic (

[52] Concerning the motivic aspect of the modulatory process in D. 68 and D. 112, the composer’s attempt to tie the transition closely to the opening material of the movement is as evident as in D. 36: in D. 68, the modulation is directly generated from the harmonic motive of the main theme, and in D. 112, the modulation is based on a projection of the source of the main theme’s harmonic motive (the F–G–F neighbor-tone gesture) onto a tonal level. A continuity thus exists in these two cases with the tight monothematic tendency of the earliest quartet movements, as seen in D. 36, but this tendency is now refined and expanded in such a way as to enable the creation of something as radically innovative and expansive as the later three-key expositions and their mechanisms.

[53] There is one last detail that links D. 112 in particular with the emergence of Schubert’s mature three-key expositions in the Quartettsatz. This is the use of a shared harmonic element in the cadential passages that establish the different subordinate tonalities of the exposition. As we have seen in D. 112, the G minor ![]()

Example 21a. Quartettsatz in C minor, D. 703. Harmonic cadential links, modulation to (click to enlarge and see the rest) | Example 21b. Modulation to G major, mm. 81–93 (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Conclusion

[54] The quartet movements discussed in this article represent only a small sampling of the sonata forms Schubert wrote between 1810 and 1816, yet they provide a useful insight into his development as a composer, while revealing some of the basic tendencies in his approach to the form.(58) Rather than a potpourri of contrasting material and themes, there is a concentration on the material of each movement’s opening bars and an attempt to derive the whole piece from that material, which in each successive quartet movement becomes increasingly harmonically oriented and is eventually divorced from the initial melodic ideas it supports to become a constructive force in the form in its own right. Schubert’s handling of this harmonic motive leads to a highly original interpretation of sonata form. In fact, only rarely in the early quartets does there appear a thoroughly conventional structure, at least according to the models advanced by William Caplin or James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy.(59)

[55] Again it is in the harmonic sphere where Schubert is the most successful and where he produces his most idiosyncratic features. Of particular importance is the role his harmonic motives play in the transition. Here the motive becomes a dynamic element in the unfolding of the form, and the result is entirely unconventional with respect to the preceding Classical practice. Whereas previously, the harmonic underpinnings of such modulations were not usually tied in closely to motivic development within the form but followed certain conventional lines, now with Schubert they are deeply motivic, emerging from the opening gesture of the movement either explicitly, as in the first movement of D. 94 or D. 36, or more abstractly as in D. 112. The effect of such modulations is also decidedly un-Classical, as can be seen in the modulatory feint of D. 68 or the deflected-cadence strategy of D. 112, both of which produce a strikingly new atmosphere for the subordinate theme and key.(60) Thus in the early quartets, while there are certainly many sonata-form movements that are not yet successful as large-scale forms, the most important elements of Schubert’s musical personality are already forming and transforming the structure from within. It is these elements, growing out of his precocious development of harmonic motives in his early quartets, that blossom into the great beauties of his harmonic practice in his mature sonata forms.

Brian C. Black

The University of Lethbridge

Department of Music

4401 University Drive

Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada T1K 3M4

Works Cited

Beach, David. 1993. “Schubert’s Experiments with Sonata Form: Formal Design versus Underlying Structure.” Music Theory Spectrum 15: 1–18.

—————. 1994. “Harmony and Linear Progression in Schubert’s Music.” Journal of Music Theory 38: 1–20.

—————. 2017. Schubert’s Mature Instrumental Music: A Theorist’s Perspective. University of Rochester Press.

Black, Brian. 1997. “Schubert’s Apprenticeship in Sonata Form: The Early String Quartets.” Ph.D diss., McGill University.

—————. 2005. “Remembering a Dream: The Tragedy of Romantic Memory in the Modulatory Processes of Schubert’s Sonata Forms.” Intersection 25 (1–2): 202–228.

—————. 2009. “The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert’s Sonata Forms.” Intégral 23: 1–63.

—————. 2015. “Schubert’s ‘Deflected Cadence’ Transitions and the Classical Style.” In Formal Functions in Pespective, ed. Steven Vande Moortele, Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers, and Nathan John Martin, 165–197. University of Rochester Press.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

Chusid, Martin. 1962. “Schubert’s Overture for String Quintet and Cherubini’s Overture to Faniska.” JAMS 15: 78–84.

Cone, Edward T. 1986. “Schubert’s Promissory Note: An Exercise in Musical Hermeneutics.” In Schubert: Critical and Analytical Studies, ed. Walter Frisch,13–30. University of Nebraska Press.

Dahlhaus, Carl. 1979. “Formprobleme in Schuberts frühen Streichquartetten.” In Schubert Kongreß Wien 1978: Bericht, ed. Otto Brusatti, 191–97. Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt.

Damschroder, David. 2010. Harmony in Schubert. Cambridge University Press.

Deutsch, Otto Eric. 1946. Schubert: A Documentary Biography. J. M. Dent.

Fisk, Charles. 2001. Returning Cycles: Contexts for the Interpretation of Schubert’s Impromptus and Last Sonatas. University of California Press.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press.

Hunt, Graham. 2009. “The Three-Key Trimodular Block and its Classical Precedents: Sonata Expositions of Schubert and Brahms.” Intégral 23: 65–120.

Hyland, Anne M. 2009. “Rhetorical Closure in the First Movement of Schubert’s Quartet in C major, D. 46: A Dialogue with Deformation.” Music Analysis 28 (1): 111–142.

—————. 2014. “The ‘Tightened Bow’: Analysing the Juxtaposition of Drama and Lyricism in Schubert’s Paratactic Sonata-Form Movements.” In Irish Musical Analysis, ed. Gareth Cox and Julian Horton, 17–40. Four Courts Press.

Kerman, Joseph. 1986. “A Romantic Detail in Schubert’s Schwanengesang.” In Schubert: Critical and Analytical Studies, ed. Walter Frisch, 48–64. University of Nebraska Press.

Kopp, David. 2002. Chromatic Transformations in Nineteenth-Century Music. Cambridge University Press.

Rönnau, Klaus. 1982. “Zu Tonarten-Disposition in Schuberts Reprisen.” In Festschrift Heinz Becker, ed. Jürgen Schläder and Reinhold Quandt, 435–41. Laaber Verlag.

Salzer, Felix. 1928. “Die Sonatenform bei Franz Schubert.” Studien zur Musikwissenschaft 15 : 86–125.

Schubert, Franz. 1996. Franz Schubert: Sämtliche Kammermusik-Werke, vol. 2 Sämtliche Streichquartette. Edited by Walther Dürr et al. Bärenreiter.

Sly, Gordon. 1998. “The Architecture of Key and Motive in a Schubert Sonata.” Intégral 9: 67–89.

—————. 2001. “Schubert’s Innovations in Sonata Form: Compositional Logic and Structural Interpretation.” Journal of Music Theory 45 (1): 119–50.

Smith, Peter H. 2006. “Harmonic Cross-Reference and the Dialectic of Articulation and Continuity in Sonata Expositions of Schubert and Brahms.” Journal of Music Theory 50 (2): 143–79.

Tovey, Donald Francis. 1928. “Tonality.” Music and Letters 9: 341–63.

Waldbauer, Ivan. 1988. “Recurrent Harmonic Patterns in the First Movement of Schubert’s Piano Sonata in A Major, D. 959.” 19th-Century Music 12 (1): 64–73.

Webster, James. 1978. “Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity, Part I.” 19th-Century Music 2: 18–35.

Westrup, Jack. 1969. “The Chamber Music.” In The Music of Schubert, ed. Gerald Abraham, 88–110. Kennikat Press.

Whaples, Miriam K. 1968. “On Structural Integration in Schubert’s Instrumental Works.” Acta Musicologica 40 (2): 186–95.

Wollenberg, Susan. 1998. “Schubert’s Transitions.” In Schubert Studies, ed. Brian Newbould, 16–61. Ashgate.

—————. 2011. Schubert’s Fingerprints: Studies in the Instrumental Works. Ashgate.

Footnotes

1. Criticism of Schubert’s instrumental music can be traced back as far as his circle of friends during the years shortly after his death, as seen in Joseph von Spaun’s comment that “we shall never make a Mozart or a Haydn of him in instrumental or church composition” (Deutsch 1946, 895). Its most detailed formulation is found in Felix Salzer’s important essay on Schubert’s sonata forms (Salzer 1928). Even James Webster’s attempt to understand Schubert’s sonata forms in a more accurate and positive light proposes underlying weaknesses in his “inhibitions—against leaving the tonic, against establishing new keys by dominant preparation, at times against the dominant itself” (Webster 1978, 35). Concerning an appreciation of Schubert’s masterly handling of harmony, perhaps the most influential contribution here is Donald Francis Tovey’s article “Tonality” from Tovey 1928. Recently David Kopp (2002) and David Damschroder (2010) have provided a theoretical basis for re-evaluating some of the most innovative aspects of his harmonic writing. Kopp in particular has proposed a more functional approach to the analysis of chromatic third relations in Schubert’s music.

Return to text

2. For the harmonic implications of Cone’s promissory note, see Cone 1986, 18. Here Cone deals with the ramifications of the blocked resolution of a prominent chord and how that resolution is eventually carried out on the broader level of the form. For Webster’s discussion of the sensitive sonority, see Webster 1978, 28. Whaples (1968) was an early contributor to this topic when she pointed out that in the first movement of the String Quintet in C major, D. 596, the outline of the opening melodic material predicts the main keys of the exposition, C–

Return to text

3. In doing so, I will be applying the functions of harmonic motives I have identified in Schubert’s mature sonata forms (Black 2009) to specific instances of harmonic motivic manipulation in the early quartets, which I first discussed in my doctoral dissertation (Black 1997).

Return to text

4. Schubert himself dismissed his early quartets in a letter to his brother Ferdinand (Deutsch 1946, 362). Problems in the sonata-form movements in particular have been addressed by Dahlhaus 1979.

Return to text

5. This situation is found in the first movements of the Quartet in G minor/B-flat major, D. 18, the Quartet in C major, D. 32, and the Quartet in C major, D. 46. Neither D. 18 nor D. 32 moves to a new key in the first part of the form, while D. 46 does establish the dominant, albeit weakly and without articulating the new key with a fully formed subordinate theme. For a more detailed discussion of the general problem, as well as the individual movements concerned, see Black 1997. For an attempt to read the first movement of D. 46 as a sonata form involving innovative features with respect to Sonata Theory, see Hyland 2009.

Return to text

6. Although a personal voice may be found in this quartet movement, it is not yet a fully mature work on the same level as his last three quartets or the Quartettsatz in C minor, D. 703. Some scholars see problematic redundancies in the writing, as in Susan Wollenberg’s comments on the transitional process with its “over effortful emphasis on G minor” (Wollenberg 1998, 33).

Return to text

7. See Black 2009 for a detailed treatment of these three categories.

Return to text

8. I would like to thank one of the external readers of this article for his/her thought-provoking comments on this aspect of the quartets.

Return to text

9. For the reconsideration of the dating of this quartet see the notes to it in Schubert 1996, 27✱.

Return to text

10. Its structure has been widely criticized, the severest judgement being that of J. A. Westrup, who considers the movement “so diffuse that it is no longer possible to discern any form” (Westrup 1969, 89).

Return to text

11. Thus I am using the terms “exposition,” “development” and “recapitulation” for convenience rather than more awkward designations such as “first part,” “second part, first section,” and “second part, second section.” The quotation marks indicate that, although the composer may have intended a sonata form, the individual sections do not actually fulfill their usual functions in that form.

Return to text

12. This theme does not return later in the form. Any sort of thematic contrast, as weak as it is here, is an unusual feature at this stage of the composer’s development.

Return to text

13. See Black 1997, 94–113, for a more detailed discussion of this quartet.

Return to text

14. The character of this double presentation is quite different from that of a conventional Classical presentation based on tonic and dominant or subdominant statements of the basic idea, or even sequential statements on I and vi, as in the main theme of the second movement of Beethoven’s Violin Sonata in A major op. 30, no. 1, measures 1–4. Rather, the double presentation’s play of light and shade look forward to, for instance, the opening of Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture, where in measures 1 to 4 the music emerges from B minor (measures 1–2) briefly into the light of the D major statement of the basic idea (measures 3–4). In the Schubert Quartet movement, the shift to VI is accompanied by a move from pp to ppp, which helps create the feeling of the retreat into an interior realm at that point and thus further emphasizes the harmonic contrast.

Return to text

15. For a discussion of the gestural function of harmonic motives in Schubert’s music, see Black 2009, 16–25. The sections marked by this motive in the “exposition” are the first section of the main theme complex; that theme’s excursion to

Return to text

16. This is an early example of Schubert’s use of parallelism and harmonic redirection to achieve the striking effect of a sudden tonal shift. The D–

Return to text

17. Here the darkening to C minor is delayed until measure 158ff, since the entry into C is marked by the applied dominant seventh to IV in measure 156. This harmonic alteration adds more urgency in the shift to C at that point.

Return to text

18. From this point on much of the remainder of the music is taken up with the struggle between C major and D major involving transitional material from the first part of the form.

Return to text

19. It is this consistent return of the main thematic material in different keys that led Dahlhaus (1979, 193) to refer to the main theme’s behavior as that of a ritornello in his discussion of the movement’s form.

Return to text

20. For a more detailed discussion of the modulatory function of harmonic motives in Schubert’s music, see Black 2009, 8–15.

Return to text

21. The subordinate theme, however, is very closely derived from the main theme, as shall be shown below, and does not return in the recapitulation. For a more detailed discussion of the movement, see Black 1997, 119–127.

Return to text

22. By partial sequence I mean that measure 3 is a statement of measure 1 on the supertonic, while measure 4 is altered to reassert the tonic in a quasi-cadential manner.

Return to text

23. For a more detailed discussion of the generation of the second subordinate theme and its relation to measures 21–27, See Black 1997, 120–21 and Example 3.18.

Return to text

24. The String Overture in C minor D. 8, from June 1811, provides the earliest example of this type of exposition in Schubert’s sonata forms. See Chusid 1962 for its debt to Cherubini’s Overture to Faniska. For a discussion of D. 8’s form, see Black 1997, 83–91. James Webster has proposed the influence of Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, op. 62, on Schubert’s three-key expositions (Webster 1978, 26–27). Graham Hunt also discusses the possible influence of Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, as well as Cherubini’s Overture to Les Deux journées in his article on the three-key trimodular block in Schubert and Brahms, which includes a detailed treatment of Schubert’s use of such a structure across his career. See Hunt 2009, especially his useful table of Schubert’s early three-key expositions in Example 7, 83. Since his article is based on Hepokoski and Darcy’s Sonata Theory, whereas the present article follows Caplin’s theory of formal functions, there are some differences in our interpretations of the form of some of the movements discussed below. These differences will be dealt with as they arise.

Return to text

25. Anne M. Hyland has pointed out the same harmonic motive in Hyland 2014, 24–25. Her discussion makes very similar points to those in my earlier dissertation (Black 1997, 120–21).

Return to text

26. The first movement of the String Quartet in E-flat major, D. 87, provides an example of Schubert’s treatment of a similar supertonic tendency in his opening material. This later sonata form, however, has a much more conventional structure and a fully formed exposition. See Black 1997, 163–70, for a detailed discussion of these aspects of the movement.

Return to text

27. The opening of the development section is largely a transposition of the opening of the transition (compare measures 42–54 to measures 93–105). Thus the key structure of the transition,

Return to text

28. In fact, from a broader perspective, both the beginning and ending of the development involve three successive steps by a major second: ascending F–G–A (measures 91–96) and descending D–C–

Return to text

29. Although its design is so unconventional, the fact that the first part of D. 68 does modulate to and confirm a subordinate key as well as articulate it with a new theme allows it to be termed an exposition without reservations, unlike the situation in earlier first movements, such as D. 94, where there is no modulation to a subordinate key in the first part. One note of caution for those following the discussion with a score; the old Breitkopf & Härtel edition of the Complete Works (F. Schuberts Werke: kritisch durchgesehene Gesamtausgabe) reproduced in Dover editions and on IMSLP is notoriously unreliable as a text. In the present case, the editors reinstated 9 bars Schubert crossed out in the interior of the exposition (between the present bars 35 and 36).

Return to text

30. This section functions as a transition and is labeled as such in Example 10.

Return to text

31. This “theme” actually functions as the second transition, although it is constructed as a thematic unit. It comes closest here to the transition/subordinate theme fusion described in Caplin’s theory of formal functions (1998, 203).

Return to text

32. David Beach has discussed this specific progression as an extremely important and prominent element in Schubert’s mature instrumental music—a “hallmark of his harmonic practice”—both on a local and broad scale (2017, 7–11). Schubert’s intensive work on this motive in the first movement of D. 68 provides an early instance of its use.

Return to text

33. This progression is a common means of modulation to the dominant key in the Classical style, but in this movement it gains a broader motivic significance due to its origins in the main theme. This relationship is underlined by the return of the opening melodic gesture of the theme to launch the first transition (violin I, measures 10–11, repeated, measures 14–15).

Return to text

34. The reharmonization of this D, in fact, gently releases all of the pent-up tensions of the preceding dominant prolongation in G minor.

Return to text

35. See, for example, the modulation to F in the first movement of the Piano Trio in B-flat major, D. 898, measures 54–59. For a discussion of Schubert’s innovative modulatory strategies, see Wollenberg 1998 and 2011, as well as Black 2005.

Return to text

36. This restriction is due to the fact that in D. 112, the harmonic motive is a prolongational progression and does not include the possibility of a pivot-chord modulation found in D. 68’s harmonic motive.

Return to text

37. For a more detailed discussion of the referential function of harmonic motives in Schubert’s mature instrumental music, see Black 2009, 4–8 and below.

Return to text

38. For further information on this strategy as well as a discussion of how it is carried out in the first movement of D. 112, see Black 2015 and below.

Return to text

39. Here the expansion of the progression involves an internal move through the tonicized IV to the VIIo7, thus I–

Return to text

40. This tonic-supertonic-tonic neighbor-tone motive is a varied transposition of the fully harmonized statement of the motive in ![]()

Return to text

41. This shift grows out of the motivic supertonic chord. In the recapitulation, the last statement of the supertonic ![]()

Return to text

42. The situation is similar to what Waldbauer 1998 has discussed in the first movement of the Piano Sonata in A major, D. 959.

Return to text

43. There is, however, a certain ambiguity about this passage. While Dahlhaus (1979, 196) and Wollenberg (1998, 33–37) accept it as an extensive transition, Webster (1978, 26, n18) refers to the movement as an early example of the three-key exposition, thus implying that the passage functions as a subordinate theme. Graham Hunt also includes this movement in his list of Schubert sonata forms with three-key trimodular blocks in the exposition. I prefer to consider the passage a transition, due to its dynamic and unsettled character and its perfect authentic cadence in the tonic in measure 73. Moreover, there is no subsequent PAC in G minor to ground that key. This is not a normal cadential design for a subordinate theme. In fact, from the standpoint of William Caplin’s theory of formal functions, the cadence in the tonic

Return to text

44. All of the remaining cadential pairs involve the deflected-cadence strategy with an evaded cadence in one key answered by a perfect authentic cadence in another. This represents a significant departure from Classical practice, where both cadences are usually in the same key with the subsequent authentic cadence rectifying the preceding cadential evasion (see Black 1997, 184–91 and Black 2015, 177–80).

Return to text

45. Dahlhaus has pointed out the development-like character of this transition. Indeed, its use of a large-scale model-sequence process (involving the transposition of the supertonic ![]()

Return to text

46. The effect of the transition’s concluding cadential passage, with its evaded and then deflected cadence, is enhanced by the transition’s initiating cadential passage (measures 35–45). The interlocking cadences here set out a model of expectation—an evaded cadence followed by a PAC in the same key. This model is surprisingly overturned in the parallel cadences ending the transition when the second cadence suddenly shifts to F major.

Return to text

47. This is an important difference with the first movement of D. 68, where, after the suggestion of G minor through the prolongation of its dominant in the interior of the exposition, the music returns first to the tonic at the beginning of the second subordinate theme and then moves directly from the tonic to the dominant key of F.

Return to text

48. The chromatic descent from dominant to tonic, outlined in measures 3 and 6, is also an important motivic element in the movement. See Black 1997, 180–82 for a discussion of its role in the exposition.

Return to text

49. The defining F–G gesture does not occur here explicitly. The

Return to text

50. This type of projection of a surface detail onto the deeper level of the form in Schubert’s music is dealt with from a Schenkerian perspective by David Beach in his influential article on the Quartettsatz (1994), where he traces the opening descending tetrachord into the underlying tonal structure of the movement. It is also the subject of two important articles by Gordon Sly (1998, 2001). In the first article, he deals with the opening movement of the Violin Sonatina in G minor, D. 13 (1816). In the second, he discusses the first movements of the Piano Trio in B-flat major, D. 898 (1827) and the Fourth Symphony in C minor, D. 417 (1815), with specific reference to their off-tonic recapitulations. His introductory observation is relevant to the present essay: “in both cases a salient feature of the movement’s opening music—in the trio, a bassline and harmonic progression

Return to text

51. For a more detailed discussion of the referential function of harmonic motives in Schubert’s sonata forms with specific reference to the Quartettsatz and other examples, see Black 2009, 4–8. For a treatment of

Return to text

52. “In harmonic terms, the first section in a double second group always leads from the tonic to the dominant, and thus always constitutes a transition” (Webster 1978, 30).

Return to text

53. Webster (1978) considers these features to be indications of two supposed weaknesses in Schubert’s sonata forms—his “aversion” for the dominant (22), and his reluctance to leave the home key (30–31; see also 35). For a closely argued defense of Schubert’s three-key expositions, see Fisk 2001, 17–19. Here Fisk highlights the careful construction of the form which maintains the polarity of tonic and dominant keys in the exposition, while allowing the interplay of the subordinate tonalities to becomes a vehicle for the expression of yearning and alienation so central to the Romantic aesthetic. For a discussion of the role that harmonic motives play in projecting the hierarchy of tonalities in such expositions, see Black 2009.

Return to text

54. Here I disagree with Anne Hyland’s assertion that measures 56–61 constitute a “true TR” in the first movement of D. 36 (2014, 24). The underlying function may be that of a transition, but the exact statement of the main theme in C major (measures 56–59) is clearly thematic and does not have any of the rhetoric or character of a transition. Furthermore, it is prepared by a dominant prolongation in C (measures 52–55) that ends with a full medial caesura, thus setting up the expectation of a subordinate theme. The process recalls the end of the transition and the beginning of the subordinate theme in a Haydn monothematic sonata form.

Return to text

55. My conclusion in these instances differs from that of Graham Hunt (2009, Example 7), who includes the first movements of D. 68 and D. 112 in his list of early three-key expositions.

Return to text

56. In fact, Webster also accepts D. 112 as an early example of the three-key exposition in Schubert’s work (Webster 1978, 26, n18). I disagree for reasons given in footnote 43 above.

Return to text

57. One of the readers has pointed out the same process in another mature work of the composer, the Piano Sonata in C major D. 812 ‘Grand Duo’ for four hands. In the first movement, the

Return to text

58. See Black 1997 for a more detailed account of formal developments in the early quartets.

Return to text

59. See the first movement of the String Quartet in

Return to text

60. Klaus Rönnau was one of the first to call attention to the manner in which the subordinate key was approached as a motivic element associated with the subordinate theme. See Rönnau 1982, 436.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2018 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

16756