Review of David Damschroder, Tonal Analysis: A Schenkerian Perspective (W.W. Norton, 2017)

Benjamin K. Wadsworth

KEYWORDS: Schenker, Free Composition, graphic notation, Stufentheorie, Schubert, mental models

DOI: 10.30535/mto.24.3.13

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

[1] Schenkerian analysis challenges both teachers and learners. This is particularly true when its core tenets—counterpoint, melodic fluency, prolongation, and reduction—are discrepant with the more vertical orientation of students’ prior training in harmony (e.g., as presented in Kostka, Payne, and Almèn 2018). Some Schenkerian textbooks aim to bridge these two approaches by striking a compromise: Neumeyer and Tepping 1992 focuses on bass line analysis, for example, and a number of texts use applied-chord notation (V/x, V→x), even though Schenker labeled these chords as chromatic alterations within the prevailing key.(1) In contrast, David Damschroder’s new textbook, Tonal Analysis: A Schenkerian Perspective, makes a clean break from the core theory approach, instilling from the ground up only those analytical concepts and habits that have direct precedent in Schenker’s final work, Free Composition (1935).

[2] As indicated on the back cover, Tonal Analysis is shaped by the insight that Schenkerian structures are simple patterns. Tonal archetypes underlie each chapter. Like the schemata identified by Gjerdingen 2007 and later authors, Damschroder’s tonal patterns are idealized prototypes, although their historical underpinnings extend well beyond the stile galant and they are analyzed on deeper structural levels. The textbook focuses on tonal patterns from the beginning, framing these as simple prototypes whenever possible; this allows for an efficient, yet unhurried pace that contrasts with Forte and Gilbert 1982 and Cadwallader and Gagné 2011, in which extensive coverage of introductory and analytical topics requires a briefer introduction to the Ursatz and other structural patterns.

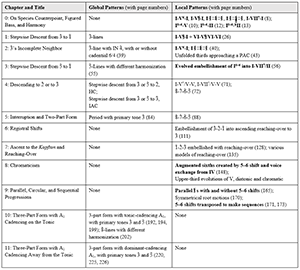

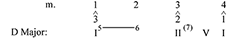

Figure 1. Global and Local Tonal Patterns in the Text

(click to enlarge)

[3] Figure 1 displays the patterns introduced in each chapter.(2) The global patterns include linear progressions in the soprano, their aligned bass lines and alternate harmonizations, and resulting forms. The local ones are short, contrapuntal embellishments of a single Stufe, called “evolutions.” In these evolutions, Damschroder traces the changing intervals above a Stufe’s root and connects stepwise pitches with dashes. Among the local patterns, the 5–6 shift is clearly the textbook’s prototypical instance of evolution: it is highlighted in bold in Figure 1. Some of its instances are familiar (e.g., holding the root of I constant) while others are less so (e.g., the I–![]()

[4] The tonal patterns pervade every chapter of Tonal Analysis. Chapter 0 presents a variety of tonic prolongations that feature the 5–6 shift. The - and -lines in chapters 1–4 set up the two-part, interrupted forms of chapter 5. Although chapters 6–9 cover less normative situations such as register shifts, ascending melodic motion, chromaticism, and non-functional progressions, Damschroder identifies common patterns wherever possible. (For instance, on p. 128 an initial stepwise ascent is the prototype for a reaching-over.) Sequences appear late in the book, in chapter 9, and not as a preliminary topic; this highlights their non-normative status in most tonal music, in contrast to Cadwallader and Gagné’s presentation (2011, 86–96). The final two chapters (10–11) deal with complete works in ternary form.

[5] Every chapter’s content is reinforced by interspersed practice analyses and more formal assignments that gradually increase in complexity, length, and rigor. Damschroder helpfully provides solutions in an appendix. Each chapter also includes examinations of Schenker’s own highly concentrated, often difficult analyses from Free Composition. Damschroder observes that Schenker’s analysis of a given work can be scattered across different locations (122); that his notation sometimes shows rhythm rather than hierarchy (35); and that this mixed use of notation can result in confusion as to an event’s structural level (47). A brief epilogue suggests a graded plan for further study, and appendices offer elements of analytical notation, solutions to practice exercises, a glossary of terms, a bibliography, and indexes of musical examples and concepts. As of this writing, a companion website is also under development.

[6] Tonal Analysis should prove a versatile textbook, suitable to a wide variety of introductory courses in Schenkerian analysis. When offered as an elective at the upper undergraduate or graduate level, an introductory course typically focuses on common-practice repertoire, issues of analysis and performance, and topics such as motivic parallelism and form. In its pacing, Tonal Analysis strikes an effective balance between upper-level undergraduate and graduate audiences. In my own undergraduate course, students and I spend about eight weeks building a basic competency at graphing with full notation. We practice with short period forms such as those covered in chapter 5 of Tonal Analysis. So, in a semester, we would be able to progress up through chapter 9, which covers sequences and their variants. I could imagine squeezing all twelve chapters into a course for graduate-level performers by taking two weeks each for chapters 0 and 1, and one week per chapter thereafter.

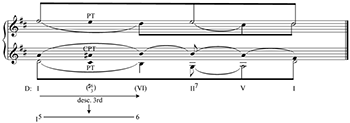

[7] Damschroder’s prose is precise and economical. Graphs are clearly notated and beautifully presented. Typographical errors, such as the caption to Example 1.7, are rare. The chosen repertoire, although sometimes too piano-heavy for my taste, tends to be short and accessible (e.g., Example 4.8), or at least expressively memorable (e.g., Example 5.3). Few concessions, however, are made to student inattention or lack of scholarly ambition: one senses, at times, the genre of the theoretical treatise. In the last few chapters, the analytical assignments would be difficult for students to comprehend without patient, lengthy study, especially if a predetermined structural framework (say, as revealed in a chapter’s title) is absent from the instructions and hints.(3)

[8] The book’s focus is harmonic-contrapuntal structure rather than motivic parallelism and expression, which sets it apart from Cadwallader and Gagné 2011, a book that begins with a chapter on motive. Reading Tonal Analysis, I found myself wishing for more discussions of expression as a payoff for hard analytical work, especially in the examinations of Schenker’s analyses, where Damschroder’s arguments sometimes bog down in descriptions of notational quirks and other technical issues.(4) It is not enough for students to know that Schenker, for instance, analyzed -lines or that these structures had various types of harmonic support. Instead, these graphs could help to show beginners why we study Schenker—perhaps to attend to the overall shape and direction of a musical work, or to inform a more convincing performance.

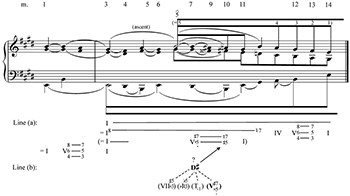

[9] Shifting now to Damschroder’s analytical method, his notational protocols are central to the textbook’s innovations. Here and in an extensive series of publications (2008, 2010, 2012, and others), he strips away analytical procedures that lack precedent in Schenker’s writings; reconsiders analytical labels, terminology, and issues of visual design with unprecedented thoroughness; and ensures consistency by jettisoning some of Schenker’s own alternative practices, such as figured-bass signatures showing inversions. In Tonal Analysis, the overarching aim is to guide and reorganize students’ thinking by offering a number of mental models—that is, spatially represented schemata—which is a first for a textbook on Schenkerian analysis. Core theory textbooks often assert an inconsistent hodgepodge of minimally abstract, self-explanatory harmonic labels: Roman numerals tethered to Arabic numerals, sometimes showing chord inversions and sometimes not; nicknames for chords such as “Neapolitan” and “French;” secondary dominants (e.g., V7/V); and chord qualities inscribed in Roman numerals, such as ii as a minor triad (Damschroder 2010, ix–x). Instances of these conventional labels are shown in line (a) of Example 1.

Example 1. A Comparison of Different Analytical Protocols (based on Damschroder’s Example 3.10, p. 56)

(click to enlarge)

[10] In comparison to conventional foreground notation, Damschroder’s protocols are simpler and more theoretically consistent. They discard concerns of chord spelling in favor of a quick global reading. As shown in Example 1, line (b), all Roman numerals are uppercase and accidentals to their upper right denote changes in chord quality. Roman numerals, representing Stufen, are organized hierarchically into rows, with more structural events higher and foreground ones lower and inside parentheses. Arabic numerals now show intervals above each harmony’s root, not its bass. Harmonic inversions are deemphasized since figured bass symbols are disassociated from Stufen: “I6,” for example, is now indicated by a ![]()

[11] Damschroder’s protocols, in total, comprise a significant innovation that may influence future undergraduate teaching. Like all pedagogical advances, however, they have a complex mixture of pedagogical benefits and drawbacks that must be weighed by prospective teachers. Parentheses are an efficient way of showing hierarchically subordinate chords. (This technique has been received well by my Form and Analysis students.) Furthermore, the protocols make it easier to analyze ambiguous root motions by third: descending-third motions such as I–VI can be understood as 5–6 shifts (9–13), and ascending-third ones as the simultaneous addition of a seventh and omission of the root (e.g., I–III as I–7/5/•). Added accidentals easily show chromatic third motions as well (e.g.,

Example 2. A Chromatic Passage by Schubert with Multiple Interpretations of a D-sharp Major Triad (based on Damschroder’s Example 8.9, p. 153)

(click to enlarge)

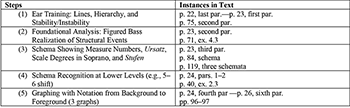

Example 3a. Reductive Process’s Steps and Instances in Text

(click to enlarge)

Example 3b. Step 1: Results of Ear Training (my reconstruction)

(click to enlarge)

Example 3c. Step 2: Sample Foundational Progression (p. 23)

(click to enlarge)

Example 3d. Step 3: Schema with Scale Degrees, Stufen, and Evolving Arabic Numbers (p. 23)

(click to enlarge)

Example 3e. Step 4: Recognition of Lower-Level Patterns (my reconstruction)

(click to enlarge)

Example 3f. Step 5: Graphing the Excerpt from Background to Foreground (pp. 24–25)

(click to enlarge)

[12] In addition, the protocols can heighten analytical rigidity and short-circuit the evaluation of harmonic context. VII

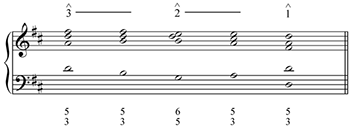

[13] The protocols set in motion a reductive procedure that is shown in Example 3a. An initial ear-training stage focuses on voice-leading lines and intuitions of stability and instability. This is followed by a figured-bass realization of structural events and then an overview of a structural soprano line, bass line, and Stufen, interpreting these as one or more global tonal patterns. A fourth stage recognizes local patterns. Finally, three notated graphs proceed from background to foreground. Detailed examination of this procedure reveals valuable ideas, but also some missing steps that should be included in later editions.(9) Damschroder illustrates this five-step process in an analysis of a four-bar phrase by Gluck (22–26). Example 3b displays my own reconstruction of the first step, which involves ear training using music notation: a decomposition of the surface melody into two coordinated stepwise melodies, one leading from down to 1 (upward stems), the other an “alto” line that harmonizes the soprano with thirds and then resolves to the unison D (downward stems). Step 2, in Example 3c, reveals a “foundational progression,” a figured-bass realization of structural harmonies and voice-leading lines. Ideally, step 2 should not telegraph the Ursatz to the student; its implicit presence here blunts the effect of the coming step 3, as shown in Example 3d. Step 3 converts the findings from the first two steps into a schema that includes soprano scale degrees, Stufen, and their evolutions. In the example, however, three unexplained decisions must have been assumed by now: (1) a Roman-numeral analysis following the protocols; (2) the match of the -line Ursatz to the excerpt; and (3) the identification of four Stufen, <I-(II)-V-I>, as structural harmonies. It would be valuable to address these missing steps explicitly in future editions. Next, in step 4, which I reconstruct in Example 3e using music notation, the student recognizes and interprets patterns on lower levels, such as the 5–6 shift in mm. 1–2. Embellishing chords are labeled according to the contrapuntal function of all voices in the texture. Step 5, shown in Example 3f, graphs the excerpt from background to foreground. Elements of this five-step procedure are implicit in graphs presented in the other chapters, but are rarely discussed outright.

[14] Overall, the procedure in Example 3 contains intriguing ideas; it could be tightened up, though, by adding in some missing steps. First, students could be asked to identify melodically fluent lines and to assign harmonic functions using the paradigm of <T-Intermediate-D-T>, as seen in Cadwallader and Gagné 2011 (34–39 and 41–56). Using these two vital concepts, a student could identify in the Gluck excerpt a phrase-initiating tonic in m. 1, a cadential II7 and V in m. 3, and a perfect authentic cadence in mm. 3–4. Identification of the Ursatz is thus much simpler. Second, the voice-leading lines identified in step 1 should be notated and evaluated for their advantages and problems, since rival hypotheses may arise in more difficult excerpts. Third, the exact mechanism for the I5–6 label is unclear in the book; it would be helpful to declare outright that descending-third root motions function as 5–6 shifts. Instructors should then discuss I–VI as I5–6 and practice similar cases, such as IV–II. Fourth, the implied mapping of Schenkerian concepts onto surface ones suggests the completion of a surface-level Roman-numeral analysis—with or without conventional labels—before step 1. Finally, I also suggest a guided transition in Example 3 between the pattern recognition in steps 3–4 and the introduction of graphic notation in step 5. My undergraduates usually need a glossary of notational devices, shown in a cheat sheet (Wadsworth 2016, 204–5); however, Damschroder’s Appendix I (243–45) uses only text.

[15] It is a strength of the book that the graphic demonstrations contain between three and five carefully planned voices, as opposed to the ad hoc presentation or even outright absence of inner voices in some textbooks, such as Neumeyer and Tepping 1992 (116). However, Tonal Analysis provides no patterns for inner voices. I would suggest that later editions include, for each of chapters 1–4, one or two graphs showing typical alto and tenor lines in treble clef and in close position. Usually, the alto line harmonizes with the soprano in lower thirds before converging with the soprano at the unison on . The tenor begins more variably, but then descends to a final . Additional voices, as seen previously in Example 1 (bass clef, upper line), are constructed ad hoc to avoid unwanted parallels with the other four.

[16] The gaps in Damschroder’s graphing procedure have two consequences. First, the text has to adopt structural assumptions unique to each exercise. Second, the student is deprived of opportunities to gain confidence and construct their own knowledge. When the given assumptions are plentiful and analytical exercises relatively simple (e.g., number 1 on p. 61), most students can bootstrap up to Damschroder’s high expectations; but when the primary tone is not assumed in advance, or when structural assumptions are more ad hoc, many students will likely struggle to produce graphs (e.g., number 7 on p. 140, which has registral shifts). Nevertheless, I acknowledge that structural assumptions—regardless of their degree of use—are necessary in an introductory Schenker class.

[17] Overall, Tonal Analysis is a landmark textbook in addressing Schenkerian analysis from the standpoint of students’ mental models. It is likely to be preferred by instructors who prioritize fidelity to Schenkerian theory, a consistent and compact organization, and direct student engagement with Schenker’s own analyses. The protocol-driven methodology allows students to arrive at global interpretations more rapidly, and tonal patterns speed up the graphing process. The book does present some difficulties for beginners, especially undergraduates, which will hopefully be addressed in later editions. Nonetheless, the text’s exemplary clarity and generous demonstrations should allow for effective supplementation. With repeated practice and thoughtful use, students should achieve a deeper understanding of Schenker’s thought, particularly in Free Composition.

Benjamin K. Wadsworth

Kennesaw State University

School of Music

Building 31, Room 111, MD 3201

471 Bartow Avenue

Kennesaw, GA 30144

bwadswo2@kennesaw.edu

Works Cited

Brown, Matthew. 1986. “The Diatonic and the Chromatic in Schenker’s ‘Theory of Harmonic Relations.’” Journal of Music Theory 30 (1): 1–33.

Cadwallader, Allen, and David Gagné. 2011. Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press.

Damschroder, David. 2008. Thinking about Harmony: Historical Perspectives on Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2010. Harmony in Schubert. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2012. Harmony in Haydn and Mozart. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2017. Tonal Analysis: A Schenkerian Perspective. W.W. Norton.

Forte, Allen, and Steven E. Gilbert. 1982. Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis. W.W. Norton.

Gjerdingen, Robert. 2007. Music in the Galant Style. Oxford University Press.

Kostka, Stefan, Dorothy Payne, and Byron Almèn. 2018. Tonal Harmony: With an Introduction to Twentieth-Century Music, 8th ed. McGraw-Hill.

Marvin, William. 2013. “The Fifth International Schenker Symposium, March 15–17, 2013.” Theory and Practice 37/38: 299–305.

Neumeyer, David, and Susan Tepping. 1992. A Guide to Schenkerian Analysis. Prentice Hall.

Pankhurst, Tom. 2008. SchenkerGUIDE: A Brief Handbook and Website for Schenkerian Analysis. Routledge.

Samarotto, Frank. 1993. “Review of A Guide to Schenkerian Analysis by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping.” Music Theory Spectrum 15 (1): 39–93.

Schenker, Heinrich. 1954. Harmony, ed. and annotated by Oswald Jonas, trans. Elisabeth Mann Borgese. University of Chicago Press.

—————. 1969. Five Graphic Music Analyses. Dover. Originally published in 1932 as Fünf Urlinie-Tafeln/Five Analyses in Sketchform. David Mannes Music School.

Schenker, Heinrich. 1979. Free Composition, trans. Ernst Oster. Longman.

Sly, Gordon. 2012. “Review of Harmony in Schubert by David Damschroder.” Music Theory Online 18 (2).

Wadsworth, Benjamin K. 2016. “Schenkerian Analysis for the Beginner.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 30: 177–220.

Footnotes

1. Samarotto (1993, 89–90) notes that Neumeyer and Tepping’s (1992) focus on bassline reduction neglects the interaction of soprano and bass. Applied-chord labels can be found in Neumeyer and Tepping 1992 (99), Cadwallader and Gagné 2011 (178), and Pankhurst 2008 (112).

Return to text

2. To aid the reader’s quick comprehension of the patterns, it has often been necessary—contra Damschroder’s approach—to use alternative analytical terminology such as secondary dominants and figured-bass numbers attached to Roman numerals.

Return to text

3. For instance, Exercise 7 on p. 140, which analyzes Mozart’s Piano Concerto K. 453, i, mm. 290–97, has hints that would be difficult for students to grasp. A superposition above the structural soprano is suggested without an adequate explanation of the underlying voice leading; the -line framework has to be inferred, unlike those in chapters 1–5; and the measure numbers, beats, and registers of most events are not specified.

Return to text

4. An example is the critique in chapter 3 of four Schenkerian analyses (65–68). An alternative would be to retain the first graph (3.1), which features many implied tones, and to replace the last three (3.2–3.4) with a single, more expansive one from Der Tonwille or Das Meisterwerk.

Return to text

5. This “non-modulatory analysis” is explained by Damschroder (2010, 7 and 14–15) as a diatonic context absorbing chromaticism, appropriate to repeated hearings of a work.

Return to text

6. Damschroder (2008, chapter 4) has previously traced this root-position approach back to earlier theorists such as Rameau and Sechter.

Return to text

7. As stated by Marvin (2013, 301), Schenker’s late theory does not accept as equivalent the V and VII Stufen. Damschroder (2017, 57) infers four isolated instances in Free Composition of dominant ninths with deleted roots in place of VII7. Schenker at this time, however, gave few explicit indications that VII7 implied V9/7/dot. A teacher using Damschroder’s textbook, if wanting to reject dominant ninths with deleted roots, should be prepared to accept a greater variety of Stufen, ranging from VII to applied-chord roots such as

Return to text

8. Brown (1986, table 4) reconstructs Schenker’s view that the I Stufe cannot have a chromatically altered root. Instructors and classes, however, may still debate alternative analytical methodologies or interpretations of Schenker’s writings.

Return to text

9. An alternative decomposition of the Schenkerian analytical process into steps increasing in complexity can be found in Wadsworth 2016, Example 4.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2018 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits:

5535