Improvisatory Exercises as Analytical Tool: The Group Dynamics of the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza*

Valentina Bertolani

KEYWORDS: improvisation, analysis of improvisation, performance practice, Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza (GINC), Franco Evangelisti, Mario Bertoncini, Walter Branchi, John Heineman

ABSTRACT: Avant-garde improvised music tends to elude analytical attempts, which have so far mostly focused on transcribing and describing sound parameters (e.g., pitch, timbre, texture, etc.) in the extant recordings. However, this does not account for the irreducible immediacy of the improvisatory practice, whose recordings are just the tip of the iceberg of a more multifold and varied production (often not recorded). This issue, inherent to the type of creative process at hand, suggests that, when analyzing, we should also take into consideration what aesthetical principles influenced the choice of a succession of musical events over another.

The principles of action-reaction and of non-repetition of the musical material were the guiding elements of the improvisatory practice of the Italian Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza (GINC) in the period 1965–1969. To adhere to these principles, GINC created a set of exercises to be practiced by members during the rehearsals. In this article I will analyze three examples from a 1967 video recording of the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza using these exercises to understand and comment the choices made on the spot by the improvisers. This strategy affords a better awareness of the group actions within the improvisatory context.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.25.1.1

Copyright © 2019 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

[1.1] Recent analytical contributions on experimental improvised music have advocated for radical shifts in methodology, focusing on the improvisatory process and group interactions (e.g., Lewis 2013; Sheehy 2013; Steinbeck 2014). These new methodologies, which move beyond the traditional transcriptions of the recordings, open up perspectives that were ignored by older analytical techniques. This paper analyzes fragments of experimental collective improvisation by capturing the irreducible immediacy of the improvisatory practice. As a case study, this paper focuses on the Rome-based improvisational ensemble Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza (GINC) in the years 1965–1969. The guiding element of the improvisatory practice of the group was the principle of action-reaction. To adhere to this principle, GINC created a set of exercises practiced by members during the rehearsals. Using video evidence, my aim is to identify the application of the exercises used during practice and other contingent solutions found by the members while improvising. Studying these exercises allows us to become better aware of the group decisions within an improvisatory context. The music preserved by the corpus of GINC recordings represents just the surface of a more multifold and varied practice in which musicians engaged during private sessions.(1) Coupling the analysis of the recordings with a thorough investigation of the few traces of their private practice leads us towards a deeper, more holistic understanding of the group dynamics that were at play during the performances.

[1.2] The analytical approach used in this paper is informed by three recent works on improvisation, each of which conceptualize the decision-making moment as strongly interactive: Vincenzo Caporaletti’s theorization of the ATP (Audio-Tactile Principle), Paul Steinbeck’s research on the Art Ensemble of Chicago (AEC), and Chris Stover’s conceptualization of the “improvisational moment.” Stover recently theorized the “improvisational moment” using Deleuze and Guattari’s work: “the improvisational moment involves the singular way in which an event cuts into a now-ongoing context, itself an assemblage of a living present (as the now-ongoing occasion of the event) and a constellation of pasts, active and passive, of which the living present is the most contracted aspect” (2017, [3.9]). Hence, according to Stover, “decisions are constantly being made: some clearly active, some entirely passive products of habit, most somewhere in between (likewise with hearing: some hearing is direct and dynamic, some occurs subconsciously)” ([5.9]). GINC’s exercise-based training influenced both their active decision-making and their passive product of habits. Every gesture is a decision that is made in the living present. Hence, in the three following analytical examples, emphasis will be put on the decision-making process of the members. Stover also exemplifies some of the contexts that can play a role in the decision-making during the improvisational moment: the context of the tune; the context of the years of studying; the context of one’s own relationship with the music’s history (“how you interpret what it means to create a personal improvisational utterance within and around the nuances of jazz’s historical and micropolitical trajectories”); the context of your habits—products of thousands of hours of practice; the larger context of the now-ongoing performance, such as “the feeling in the room, the way the audience is responding”; the context of the exemplary recordings already existing, etc. ([2.16]).(2)

[1.3] In his article on the AEC, Steinbeck (2008) analyzes the improvisation of the Chicago collective as an interactive process and from a phenomenological point of view. The interactive process is analyzed by using the theoretical device the author calls an “interactive framework.” According to Steinbeck, this interactive framework is roughly analogous to the “style systems” identified by Leonard B. Meyer as they are “musical structures that are experienced interpersonally among a community of composers, performers, and auditors” (2008, 401). Dedicated rehearsal time allowed AEC members to internalize “musical systems, performance styles, and interactive frameworks that would ultimately resurface during the improvisational process” (405). By using this interactive framework, Steinbeck interprets AEC improvisations through group dynamics (e.g., the contrast between moments of consensus and “multi-centered” frameworks that require negotiations within the group) rather than just on the basis of the musical content of the recordings of the group’s improvisations (401–2). Moreover, the phenomenological perspective, based also on his experience as an improviser, allows Steinbeck to take into account “a large body of ‘implicit, practice-based knowledge’ in order to rapidly process musical sounds as meaningful and spontaneous in appropriate ways” (403). As noted by Steinbeck, the traditional phenomenological analysis is actually broadened by conversations with the group members done in the preliminary stages of the analysis (404).

[1.4] Caporaletti (2005) also identified similar dynamics in his study of the AEC. For example, Caporaletti’s concept of “signal form” (derived from Stockhausen’s Momentform; see Stockhausen 1963) is the consequence of behavioral negotiations in the moment, where transitions are signaled among the members by subtle variations understandable by the players embedded in that specific aesthetic environment (2005, 403). The creative process of improvisation postulated by Caporaletti is enriched by acknowledging the importance of contextual feedback between the improvisers and the audience (78, 110)—something similar to the importance of the “feeling in the room” and improvisers’ relationship to their own previous recordings, as discussed by Stover (2017, [2.6]). In the case of GINC, the feedback is not only between the performer and the audience, but also among the performers themselves. In fact, as we will see later, performers listen back to recordings of their sessions and discuss them as a group. Such discussions in turn affect future results in a never-ending loop of collective self-reflection.

2. Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza as a Case Study

[2.1] Nuova Consonanza was first born as an association promoting contemporary music in Rome. In 1964, thanks to the efforts of Franco Evangelisti and his meeting with the American composer and improviser Larry Austin (who founded the improvisation group NME—New Music Ensemble in California), GINC began its activity, and its first public performance was in 1965.(3) According to Austin, he was one of the catalysts for the creation of GINC: “In 1964–65 I went to Rome on a Creative Arts Institute grant from the University of California . . . the New Music Ensemble was continuing and they sent me tapes of their sessions and concerts. . . . I played the tapes for Franco Evangelisti . . . who was simply astounded: ‘What process are you using, what score?’ Nothing, I would reply” (Austin 2011, 1). Evangelisti was impressed by the NME; in the program notes for the first concert of GINC, he wrote: “[The New Music Ensemble,] which works in California, can be considered the first existing group in the Western system that works on actually contemporary schemes. For the creation of our group ‘NUOVA CONSONANZA’ the presence of Austin was crucial, and equally important was the cooperation among the fellow composers working in it.”(4)

[2.2] Initially, the members of the group varied, with some musicians participating only once (such as Larry Austin himself), some others participating intermittently (such as Frederic Rzewski), and others just attending the private sessions (like Cornelius Cardew and Giacinto Scelsi). Among the more stable members of GINC were Mario Bertoncini, Egisto Macchi, Roland Kayn, John Heineman, Ennio Morricone, and Walter Branchi. However, the theoretical underpinnings of the work of GINC were mostly presented by the charismatic figure of Franco Evangelisti, who acted as a spokesperson for the group and had the most influential international connections (Wagner 2004; Anderson 2011).

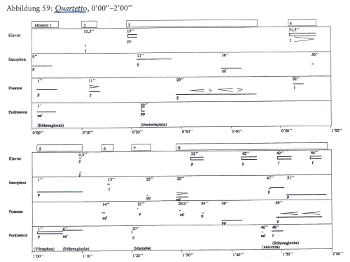

Examples 1a and 1b. Graphic rendition by Thorsten Wagner of “Quartetto” and schema with the description of sections

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Examples 2a and 2b. Graphic rendition by Ingrid Pustijanac of “RKBA 1675/I” and schema with the description of sections

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.3] Among the collectives of free improvisation active in North America and Europe in the 1960s and 1970s, GINC represents an interesting case study because of the existence of audio-visual evidence documenting the group’s work. The 1967 documentary by the Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR) is an astonishing document given the limited amount of recorded material of improvisational groups in the 1960s. Also, with exception to notable examples such as the analytical work on the Art Ensemble of Chicago by Steinbeck (2008, 2017), collective experimental improvisation is seldom analyzed in depth. Nevertheless, two analyses of GINC’s improvisations have been published: Wagner (2004) (Examples 1a and 1b) and Pustijanac (2016) (Examples 2a and 2b). Notwithstanding the twelve years separating these two analyses, they share some guiding principles: (1) both generate graphic transcriptions based exclusively on published recordings; (2) the transcriptions are based solely on the sonic material; (3) they decontextualize the recording from more general information about the improvisative/performance practice; (4) their analytical strategy is informed by a specific member of the group: Evangelisti for Wagner, Bertoncini for Pustijanac.

[2.4] Both graphical renditions comprehensively describe the sonic results in the tracks they analyze, but they do not account for the process that produced the result. Both operate segmentations of the tracks according to sound duration, sound material, dynamic shape and texture (parameters typically taken into account in the analytical tradition of Western concert music). Both also consider the “directionality” of the specific segment—that is, whether specific sections are static or more varied and the density of events (variously measured) in each section. In each case, the analyst seeks to establish an understanding of the overall formal structure of the published track. Indeed, both approach the recordings as stable representations of the musical material. However, this approach is problematic. Assimilating improvisation to composed music is not unusual. Namely, Steinbeck (2013) identifies three main fictions frequently used in improvisational studies, echoing Marion Guck’s (1994) identifications of “fictions” underlying the ways in which we talk about European concert music: (1) Improvisation as composition, (2) Improvisation as social practice, and (3) Improvisation as opposition. When “improvisation is like composition, our analyses tend to valorize the things we seek out in composed music, particularly relatedness and complexity. We are amazed that improvisers can conceive and perform such intricate music in real time. But then again, certain composers do their work at the keyboard or another instrument, and many musicians are equally skilled at composition and improvisation” (Steinbeck 2013, 4–5). This fiction is at the core of both Wagner’s and Pustijanac’s analysis.

[2.5] The authoritativeness of recordings as a source has long been discussed by music scholars. In the case of GINC recordings currently available, most researchers assume they are authoritative by default. In fact, we know very little about how these recordings were made, and even less about the studio editing that was applied to the tracks after the recording. Some of these editing choices are very evident to the ear;(5) some, harder to hear, may have remained undetected to date. Indeed, we cannot be sure whether the tracks on the recordings represent a single take from start to finish, or montages of different sessions edited together. The history of GINC recordings is further complicated by the ambivalence felt amongst GINC members about part of their discography. Some members consider the recordings to be unrepresentative of the subtle work done during the private sessions.(6) For these reasons, the assumption that the tracks represent complete and unmediated recordings of improvisational sessions as intended by the group is unwarranted.

[2.6] As opposed to Wagner’s and Pustijanac’s work on GINC, my analysis focuses on the group interactions and decision-making process. In particular, following Steinbeck’s work on the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the goal is to analyze the group improvisation of GINC as “networks of spontaneous, collective interactions” (2008, 399). Like Steinbeck, I will use insights from interviews with the performers, in addition to personal insights gained by working closely on Mario Bertoncini’s performance practice, in order to understand the recordings within the immediacy of the improvisational practice and larger context of production and aesthetics, including the immediacy and “in-the-moment individual and collective decisions” made by the members of GINC (Steinbeck 2008, 399).

3. The Principle of Action-Reaction: Practicing Improvisatory Exercises

[3.1] Two core ideas inform the performance practice and aesthetics of all members of GINC: the idea of the composer-performer and the guiding principle of action-reaction. This paper will focus primarily on the latter. The principle of action-reaction, so named by the members of the group themselves, governed the way in which members of GINC developed their group improvisations. It was largely tacit knowledge, embodied and shared among members of the group. As such, it is not discussed in texts by GINC and is only mentioned in passing in interviews and oral accounts. Roughly defined, the action-reaction principle meant that fellow improvisers should react to an action proposed, but in doing so they should avoid (1) repeating or mimicking that action, (2) repeating rhythmical or metrical patterns, and (3) using techniques and musical behaviors learned during traditional training years (this is paraphrased from Bertoncini in Gaddi 1993, 98).(7) This is not to say that repetitions never occurred in GINC performances, but rather that, when they did occur, the group would treat them as unwanted results that should be improved upon in future sessions. According to Bertoncini and Branchi (the GINC members who have addressed the issue of repetition most often), the prohibition of repetition focused mainly on metrical and rhythmical qualities of the sound rather than musical propositions (which sometimes circulated among performers, thanks to the exercise “economy of the material,” mentioned later).

[3.2] In order to avoid repetition and other traditional techniques, GINC members devised special techniques and solutions, both individually and collectively. For instance, at the individual level the pianist-composer Mario Bertoncini affirmed: “[While working with the Gruppo] I never touched the keyboard side of the piano because I was afraid that the stylistic elements I learned as a performer would emerge during improvisation” (Bertoncini in Gaddi 1993, 143).(8) However, he also recalls how fellow members such as Ennio Morricone or John Heineman, while playing their own instruments, still had the intelligence and sensitivity to go beyond the timbral possibilities inherent to the instruments themselves (Bertoncini in Gaddi 1993, 143).

[3.3] The members of GINC imposed on themselves an arduous training regimen that comprised two elements: collective exercises and collective listening sessions. Bertoncini stresses this point in his recollections: “All musical gestures were banned, for example clear rhythmic structures, repetitive patterns, harmonic intervals, melodic figures. And how can a musician avoid a melodic figure when he plays two notes? I have said, one can avoid the melodic figures with the help of the other members of the group” (Anderson 2013, 374).(9) Therefore, group training was a key element in the experience of GINC, as much as it was a key element in other similar collective experiences, such as the AEC, but also the NME, and the AMM.

[3.4] The members of the group devised several exercises that “trained the basic skills of reaction as a response and that improved the ability to listen” (Branchi 2014). These exercises are not “rules” or “schemes,” but rather descriptions of behaviors, as explained by Bertoncini: “Back then, I wrote some exercises and more unwritten ones were created; these were not forms, nor formulas or schemes: they were descriptions of behaviors within which we were completely independent” (Bertoncini in Gaddi 1993, 142).(10)

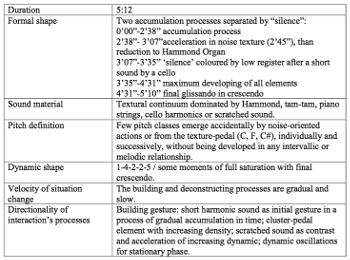

Example 3. Collective exercises used by GINC

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.5] To date, the most extensive report of the exercises is in Anderson (2013, 374–75). She notes that the group members worked on developing listening skills. “There were no schemes for improvisations, but exercises that trained the basic skills of reaction as a response and to improve the ability to listen” (Anderson 2013, 374). Building on this work, and based on an interview with GINC member Walter Branchi,(11) I have created a list of the exercises that were used in the group’s training sessions (Example 3).(12)

[3.6] According to Branchi, Exercise 1 was the most effective and important because it required the participants to learn how to listen to the other improvisers: “This exercise, with these limitations, forced you to listen to the others, no way out. Because you could not do certain things, you could not be the soloist, even if the proposition came from you . . . Mostly because the proposition was not made and then left, it was carried on, until the proposition was musically concluded and the others had to conclude, too. . . . In my opinion this was the most important exercise because it forced us to listen, to build on material that you are given and that you cannot anticipate, as it comes from someone else” (Branchi 2014).(13) In an earlier interview published in Gaddi, Branchi offered a more thorough description of the collective negotiation involved in this exercise: “The moment in which my proposition ends will be clear, so much so that the next proposition will follow immediately afterwards. This entails at least two advantages: it forces you to interact and it forces you to listen to everything that is going on—something that does not happen often with performers, who tend to listen to themselves, their proposition, without realizing what the others are doing” (Branchi in Gaddi 1993, 153).(14) Heineman also reinforces this point when he acknowledges that one of the most interesting aspects was to interact with “composers rather than soloists” (Heineman in Gaddi 1993, 164). According to Heineman, this was also the main point differentiating GINC from the American New Music Ensemble: “They [NME] had talented performers, but they were not composers.(15) So, their improvisation presented a soloist- and virtuoso-like disposition, while the key point in Nuova Consonanza was to collaborate with composers, even with people like Franco [Evangelisti] who played despite not being strictly a professional performer”(16) (Heineman in Gaddi 1993, 165). As Branchi recalls, the order was mostly chosen on the spot, deciding beforehand exclusively the line-up of the group. It is not that solo moments were strictly forbidden, but, as Heineman reports, no member of GINC would have transformed or interrupted the reaction to insert a solo moment (Heineman in Gaddi, 163).

[3.7] The group exercises also provided an opportunity for collective reflection. The members evaluated their performance by listening to the recorded sessions and discussing them as a group listening activity (Anderson 2013, 374). Branchi underscores this point: “Much was also built on group-based listening activities. That is, the improvisations we did, especially those that were exercises, were always re-listened to at the end, they were discussed. Then we asked ourselves, ‘Did it work? Or not? Why didn’t it work? You did this, you did that. . . ’ In short, these exercises were so strong, so binding that, when we were doing a so-called ‘free improvisation’ (so only the number of players was decided beforehand: the three of us, the two of us, the five of us, and so on), the constraints were so strong that we worked perfectly. It was almost as if we were talking to each other” (Branchi 2014).(17) This idea of conversation proposed by Branchi can be read as a touchstone in the group’s struggle to find a middle ground between the skillsets of the composer and the performer. According to their views on the role of the composer and of the performer, a self-indulgent virtuoso-like approach would be akin to speaking without listening. On the other hand, a normative composer-like approach would lead to expecting others to just listen and follow inputs. A conversation, instead, requires participants to both speak their mind and listen to what others have to say: exactly what the exercises are designed for.(18) This is why these exercises and their use in rehearsal resonate with Steinbeck’s concept of interactive frameworks described above. Moreover, they also describe the form of communication happening among the improvisers in what Caporaletti calls “signal form.”

[3.8] It is thus clear that the composers/improvisers in GINC were listening to the recorded sessions and using the exercises as self-reflective moments enabling a collective awareness of how their skills were evolving. My question, then, is: Can we transfer this knowledge into our analysis of the recordings? And what would an analysis informed by the exercises look like?

4. Three Excerpts

[4.1] The three examples presented here (referred to as Excerpt #1, Excerpt #2, and Excerpt #3) demonstrate how to use the exercises devised by GINC as an analytical tool. The work for this article was done exclusively on the video documentary shot by the Norddeutscher Rundfunk on the occasion of a concert in Rome in 1967. The concert took place after a few months of very little activity, because Evangelisti was in Germany on a DAAD scholarship and in the meanwhile the group gathered only occasionally (Branchi in Gaddi 1993, 150).

[4.2] GINC worked differently from many other groups. For example, Musica Elettronica Viva, another collective of improvisers active in Rome since 1966, used to perform every day and ended up renting a space and working together as a sort of hippy commune (Beal 2009, 105 and 109). Concerning the New Music Ensemble, the accounts are discordant: sometimes they had weekly sessions (Austin 2015), sometimes the group members met “almost every day . . . [W]e’d spend sometimes as much as six hours per day together, exhilarated!” (Austin 2011, 30). However, both of these accounts show continuity in their collective improvisatory practice (a continuity that was not interrupted during Austin’s sabbatical in Rome, 1964–65). The London-based AMM also had regular periodical meetings ranging from closed-door sessions to proper concerts. According to Callingham, “AMM . . . held weekly sessions . . . at the Royal College of Arts and the London School of Economics, between June 1965 and September 1966” (Callingham 2007, 23–24), suggesting again strong work continuity among the members of the group. This continuity allowed the members to grow a sense of group belonging and internalize techniques on a day-to-day basis.

[4.3] Instead, most of the time, GINC members were scattered all around Europe and usually reconvened when they had to prepare a specific gig. This is the case for the documentary: “In the four weeks before the concerts, the group met every day, not in order to study some precise pieces, but rather to define a range of improvisation possibilities and also to find a mutual language”—meaning the exercises (Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza 2006, 1:10–1:25).(19) The documentary enables the scholar to see the performers while they play and to pick up on their body language as well. However, the reader should bear in mind that the clips shown in the documentary do not constitute complete tracks. Rather, the documentary presents the music as a practice and not as a series of self-contained sessions that could give the impression of being intended by the group members as compositions.

Excerpt #1

Example 4. Video 1—DVD excerpt: 14:40–16:15

(click to watch video)

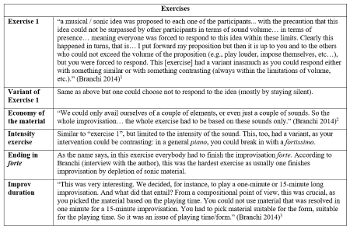

Example 5a. Video rendition of video-example 1 created with Acousmographe, GRM

(click to enlarge )

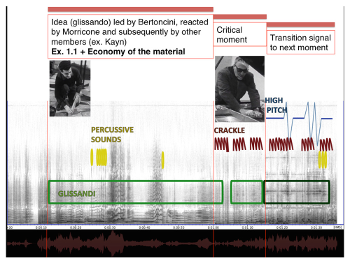

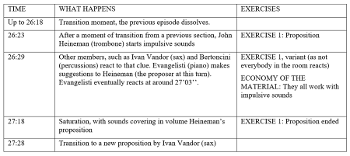

Example 5b. Visual rendition of video excerpt with major group dynamics and decision-making process

(click to enlarge )

Example 5c

(click to enlarge )

[4.4] In the characteristic texture of this excerpt (Example 4), we can isolate different voices (Example 5a). The core voice is made up of a series of glissandi (green) featured in several instruments: the rubbing tube (Mario Bertoncini), the sax (Ivan Vandor), and the electric organ (Roland Kayn). Occasionally, there are percussive sounds (yellow) outside of the video frame. The crackle (maroon) is produced by Franco Evangelisti’s brush scrub against the strings of the piano, and the high-pitched glissando (blue) is most likely Morricone’s trumpet mouthpiece. Although all of these sounds do vary, they do not evolve throughout the excerpt. Consequently, the entrance of a new layer is a very significant element. This image is created with Acousmographe, highlighting the sonic elements featured in Excerpt #1. Thus, this visual rendition suggests the creation of a sound object based on a process of accumulation.

[4.5] Such a reading (see again, Example 5a), however, would leave out some of the important features structuring Excerpt #1. Rather than focusing the analysis on just the sonic material, this article tries to make sense of the music material presented in the video excerpt from the perspective of the group dynamics that were informed and fostered by the exercises. The video excerpt opens with a transition moment from a previous section. After this, Bertoncini finds a glissando sound created by friction, namely by rubbing a tube against the floor (Example 5b).(20) The sound is explored for about 90 seconds. Within this specific example, the tube’s glissandos cover a range of approximately a twelfth (around C#–G#). The sound color varies from a more somber and less resonant effect to a brighter timbre. Other members react to that cue by working on glissando possibilities on their own instruments: Vandor on the sax, Morricone on the trumpet, and Kayn on the electric organ. Rhythmically, the glissando gestures are irregular and do not form a recognizable pattern. By referring to the exercises (Example 5c), it is possible to find a rationale behind these group interactions. In fact, they are using:

- Exercise 1: nobody gets louder than Bertoncini

- economy of the material: all work uniquely with glissandos.

[4.6] In the second part of Excerpt #1, Franco Evangelisti (on the piano) introduces a different sound: a scrub brush against the piano strings. The action stands out as a sound with very different features from the glissando part: made up mostly of disruptive and dissonant crackles. One might be tempted to think that Evangelisti’s action is a deliberate contradiction with regard to Bertoncini’s idea. However, I propose that Evangelisti’s action is not disconnected from the action led by Bertoncini. On the contrary, Evangelisti is trying to react to the action in a different way: not through the qualities of sound (the glissando element, like all other performers involved) but through the quality of the gesture (friction) by rubbing a brush against the string (mirroring Bertoncini’s tube rubbed against the floor). In my opinion, this reading is supported by the fact that Evangelisti is not completely alienated from the sound qualities of Bertoncini’s idea: indeed, he tries to react by rubbing a little bottle along the piano strings. This obviously generates a glissando, but Evangelisti discards it (my hypothesis is that he is looking for a less predictable, more innovative result). At first, Evangelisti’s reaction is not deemed satisfying by other members of the group. Eventually, this critical moment influences the group. The high-pitched sound at the very end signals that it is time to move to the next idea (echoing the signal form hypothesized by Caporaletti and discussed above).(21) The group abandons the action initiated by Bertoncini and moves on.

[4.7] Of course, my interest in Excerpt #1 is not to illustrate that Evangelisti did something wrong; he did not. Instead, this example conveys the ways in which GINC worked: both in private sessions and in public performances, they explored possibilities, giving themselves space to fail, rather than working in a some kind of teleological structure defined after the fact. Instead of analyzing these recordings as if they were fully composed sound objects, we should see them as moments of experimentation and aesthetic research by means of their collective artistic practice.

Excerpt #2

Example 6. Video 2—DVD excerpt: 26:22–27:50

(click to watch video)

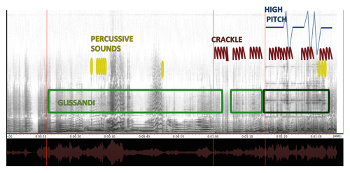

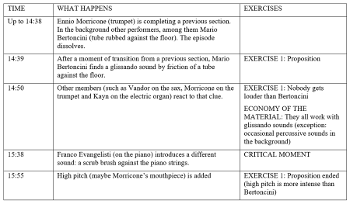

Example 7. Description of Example #2 with association to exercises

(click to enlarge )

[4.8] Excerpt #2 presents 90 seconds of improvisation featuring Heineman (trombone), Evangelisti (piano), Vandor (sax), and Bertoncini (drums) and other percussions off-camera (Example 6). The sonic result of this excerpt is very different from the one discussed in Excerpt #1. First, the improvisers are standing and moving around the space, changing their position relative to each other. The camera is pointed towards the piano, where the performers congregate as the improvisation goes on. Hence, in this example there is an interest in exploring spaces and resonances (testified also by a general orientation towards the inside of the piano, to create possible vibrations of the piano strings). Second, the texture is not layered and it is mostly constituted by impulsive sounds (trombone, piano, and drum) with no metrical regularity. This happens on top of a continuous and erratic pianissimo sound probably coming from the saxophone, which joins into the impulsive idea proposed by the trombone 40’’ into the example, roughly at the same time as the piano starts to participate. With the exception of the central part of the excerpt (about 00:20–00:32 into the video), the trombone moves in a narrow range (about a third). When the sax joins into the impulsive gesture, it uses the same pitches as the trombone. A transcription of the recording in score format would provide an accurate representation of the very simple instrumentation and a precise reading of the very irregular rhythmical impulses (to the fractions of second if using a software). On the one hand, this might help the analyst find hidden rhythmical patterns and specific pitches. However, these notated parameters are byproducts of a process. They were not planned in advance, but rather were chosen on the spot. Furthermore, we also know that if recognizable rhythmical patterns emerge in these exercises, they should be considered as “unwanted” results, according to the “non-repetition” aesthetic principle GINC held itself to.

[4.9] On the other hand, if we describe this fragment according to the exercises (Example 7), we can notice that, surprisingly, the connection with Excerpt #1 is very strong. Like this first example, this passage is an improvisation based on:

- Exercise 1: (This is a variant of the exercise, because other people are in the room and they are not playing). The exercise is led by John Heineman (trombone), presenting an impulsive idea. Other improvisers (especially Bertoncini, Vandor and Evangelisti) participate in the impulsive idea, without superimposing their sounds in volume.

- economy of the material exercise: the centrality of the idea of the impulsive sound is the reason for the sparse and non-layered sound result.

[4.10] Therefore, this example is actually the same in structure and intention as Excerpt #1, even though the material and the scoring are very different. This means that the exercises trained the behaviors of the members of GINC so that we can identify archetypical “interactive frameworks,” which use very different sound material but in ways that are nevertheless fundamentally the same.

Excerpt #3

[4.11] Excerpt #3, my last example, is important because it identifies the limits of an analysis based on the exercises. As important as it is, the information gleaned from a study of the exercises cannot explain everything that takes place in an improvisation, nor can it explain all of GINC improvisations. However, it is still informative because it shows alternative ways of using the same exercises, alternative ways of interacting among performers, and hints at possible critical moments and unfulfilled intentions.

Example 8. Video 3—DVD excerpt: 17:46–20:25

(click to watch video)

[4.12] The improvisers are Heineman (cello), Branchi (bass), and Bertoncini (percussions) (Example 8). The most problematic aspects of Excerpt #3 are: understanding who (if anyone) is leading the improvisation, and whether or not and in which form Exercise 1 is applied. Indeed, the montage of the documentary brings us directly into an action that is clearly already underway; therefore it is very hard to understand who proposed the idea to begin with, or if it was proposed at all. The impulsive gesture at 0:13 (18:01) (this gesture is out of the camera) by Mario Bertoncini—the bow hitting the cymbal and then generating a long bowed sound—and the fact that Heineman reacts so closely in time to it while looking intensely at Bertoncini suggests that Bertoncini may have been the initiator of the action.

[4.13] Excerpt #3 offers useful hints for discussing the problem of interaction among improvisers, another aspect at the core of exercise 1. Like Excerpt #2, this one features a smaller group of performers. In Excerpts #2 and #3, the smaller group and the performers’ distribution in space allow for more visual contact among the improvisers than we see in Excerpt #1 (see for example 00:40–1:08). Around 00:40 (if not earlier), Bertoncini is no longer the leader. The communication between Branchi and Heineman is so intense and the reactions so close (almost unison), that it is hard to know who is the initiator of the action and who is reacting, if anyone. Considering the solo moment Heineman has around 00:40 and the clear reaction Branchi has to Heineman’s sound around 1:06–1:08, I assume the leader is Heineman. (This case also shows how personality traits are important, as well: Heineman is an improviser who is certainly willing to take into account suggestions coming from the environment, even when he is clearly the leader, as it happened in Excerpt #2, when he followed Evangelisti’s directions). Similarly, at 2:06 the collaboration between Branchi and Heineman is so close that any understanding of what is happening using exercise 1 will fail miserably.

[4.14] However, this intense exchange among improvisers does not mean that suggestions are easier to pick up for the other participants every time they are made. For example, from 2:06 there is an increase in intensity from all the performers. Around 2:33–2:35, the specific montage of the documentary captures a gesture by Heineman inviting the other performers to finish abruptly in forte (as noted above, Branchi felt that this was one of the hardest exercises). However, even though the episode will finish a few seconds later, and generally both Branchi and Bertoncini will finish in forte, it seems that both Branchi and Bertoncini did not pick up Heineman’s suggestion—not immediately at least.

[4.15] Moreover, the sonic material used during the improvisation is treated differently than in previous examples and the “economy of the material” exercise is not used (or at least it is not used to the same extent as in the previous examples). This is particularly interesting, because, in contrast to the previous examples (characterized by an assembly of instruments with limited similarities), all three performers could have potentially worked with bowed sounds. Instead, the performers looked for variety in the production of sound. This strong differentiation of sound production among the three instrumentalists is particularly evident in several moments. For example, in the first 20–30 seconds, while Heineman is plucking strings on the cello, Branchi is working with specific pitches (G–F–A), while Bertoncini is the only one producing long bowed sound on the cymbals. However, the material is not completely unrelated, as the pitches used by Branchi are the same as those emerging from Bertoncini’s bowed sounds. A similar example occurs at the very end of this excerpt (from 2:07 onward): both Branchi and Heineman are performing quick, percussive staccato sounds, while Bertoncini continues with long, resonant bowed sounds produced on the cymbals. In this case, the “economy of the material” exercise certainly applies to the sounds produced by Branchi and Heineman, but not to Bertoncini. Obviously, there are also moments of great unity among the three performers (see, for example, 1:08–1:58). Hence, the “economy of the material” principle is not discarded completely; rather, it is just not applied continuously throughout the example like it was in previous examples.

5. Conclusions

Around this series of unwritten rules revolve many of the endless discussions that arose during the performing sessions. Integration is possible as long as everybody’s practice finds its own space of expression while complying with such obligations; eventually, even stealthily turning these rules—which are far from dogmatism—on their head. (Gaddi 1993, 64)(22)

[5.1] Using the exercises as a key to understand the extant recordings offers a glimpse of the immediacy of the creation, focusing on the behaviors cultivated with such care by the members of the group. Obviously, this method of analysis cannot be extended systematically to the entire duration of a recording, nor should it be, since the exercises were not applied consistently. Yet, it gives us access to what is undocumented, namely the training of action-reaction behavior before the public performance and the members’ learning curve and experimental attitude.

[5.2] More importantly, this method of analysis offers a practical example of how to challenge the relationship between analysis and improvisation. As August Sheehy writes: “With a shift in emphasis from thing to process, however, analysis and improvisation might be brought into a productive relation. To put this in the form of a question: If music analysis is first and foremost an activity, and improvisation is a way of acting, in what sense can analysis itself be understood as improvisational?” (2013, 4). Sheehy, Lewis, and Steinbeck suggest that, in our analyses, we focus on the very moment of discovery during improvisation, even if we were not there. This article and the three analytical examples offered were guided by the idea that we should “identify with the music’s co-creators rather than what is created” (Steinbeck 2014, 3). A deep form of participatory listening (and rehearsing, albeit just virtually) that does not focus on the sonic material as presented but rather on the decision-making process allows us to take the social and sensorial experience of the improvisers seriously.

Valentina Bertolani

University of Calgary

valentina.bertolani@gmail.com

Works Cited

Anderson, Christine. 2011. “Franco Evangelisti ‘ambasciatore musicale’ tra Italia e Germania.” In Musikstadt Rom: Geschichte, Forschung, Perspektiven, Beiträge der Tagung “Rom: Die ewige Stadt im Brennpunkt der aktuellen musikwissenschaftlichen Forschung” am Deutschen Historischen Institut in Rom, 28.–30. September 2004, ed. Markus Engelhardt, 499–516. Bärenreiter.

—————. 2013. Komponieren zwischen Reihe, Aleatorik und Improvisation: Franco Evangelistis Suche nach einer neuen Klangwelt. Wolke Verlag.

[Anonymous]. 1965. GINC program notes. Held at Fondazione Isabella Scelsi, Rome.

Austin, Larry. 2011. “Introduction.” In Source: Music of the Avant-Garde, 1966–1973, ed. Larry Austin and Douglas Kahn. University of California Press.

—————. 2015. Interview with the author. November 7, 2015.

Beal, Amy C. 2009. “‘Music Is a Universal Human Right’: Musica Elettronica Viva.” In Sound Commitments: Avant-Garde Music and the Sixties, ed. Robert Adlington, 99–116. Oxford University Press.

Branchi, Walter. 2014. Interview with the author and Luisa Santacesaria. August 11, 2014.

Callingham, Andrew Edward. 2007. “Spontaneous Music: The First Generation British Free Improvisers.” Ph.D. diss., University of Huddersfield. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/4659/

Caporaletti, Vincenzo. 2005. I processi improvvisativi nella musica: Un approccio globale. Libreria Musicale Italiana.

Farina, Maurizio. 2017. “Cronologia 1965–68.” In Nuova Consonanza Azioni / Reazioni, 61–63. Die Schachtel.

Gaddi, Piero. 1993. “Il Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza e la pratica dell'improvvisazione collettiva nel campo classico.” Dissertation, Università degli Studi di Bologna.

Guck, Marion A. 1994. “Analytical Fictions.” Music Theory Spectrum 16 (2): 217-30.

Lewis, George. 1996. “Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives.” Black Music Research Journal 16 (1): 91–122.

—————. 2013. “Critical Responses to ‘Theorizing Improvisation (Musically).’” Music Theory Online 19 (2).

Mastropietro, Alessandro. 2017. “Roma-Firenze 1965: due debutti (paralleli), documenti sonori, e riflessioni sul contesto sperimentale romano.” Paper presented at “Building on a shared vision...”: International Conference on the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza and collective improvisation from 1965 to the present, Rome, December 14–16, 2017.

Pustijanac, Ingrid. 2016. “New Graphic Representation for Old Musical Experience: Analyzing Improvised Music.” El oído pensante 4 (1): 1–16.

Saladin, Matthieu. 2014. Ésthetique de l’improvisation libre. Expérimentation musicale et politique. Paris: Les presses du réel.

Sheehy, August. 2013. “Improvisation, Analysis, and Listening Otherwise.” Music Theory Online 19 (2).

Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1963. “Momentform: Neue Beziehungen zwischen Auffu ̈hrungsdauer, Werkdauer und Moment.” In Texte zur elektronischen und instrumentalen Muzik, vol. 1: Aufsätze 1952–1962 zur Theorie des Komponierens. Cologne: DuMont Schauberg, 189–210.

Steinbeck, Paul. 2008. “‘Area by area the machine unfolds’: The Improvisational Performance Practice of the Art Ensemble of Chicago.” Journal of the Society for American Music 2 (3): 397–427.

—————. 2013. “Improvisational Fictions.” Music Theory Online 19 (2).

—————. 2014. “Improvisation, Identity, Analysis, Performance.” American Music Review 44 (1): 1–5.

—————. 2017. Message to Our Folks: The Art Ensemble of Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

Stover, Chris. 2017. “Time, Territorialization, and Improvisational Space.” Music Theory Online 23/1. http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.17.23.1/mto.17.23.1.stover.html

Wagner, Thorsten. 2004. Franco Evangelisti und die Improvisationsgruppe Nuova Consonanza: Zum Phänomen Improvisation in der neuen Musik der sechziger Jahre. Saarbrücken: Pfau.

Discography

DiscographyGruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza. 2006. Gruppo di Improvvisaizione Nuova Consonanza – Azioni. Milan: Die Schachtel DS13, 2 compact discs, 1 DVD and one booklet.

Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza. 2006. Gruppo di Improvvisaizione Nuova Consonanza – Azioni. Milan: Die Schachtel DS13, 2 compact discs, 1 DVD and one booklet.

Footnotes

* I wish to thank Mario Bertoncini for his continuous encouragement, Walter Branchi for his collaboration, the School of Creative and Performing Arts, University of Calgary, and the Killam Trust for supporting my research. I also wish to thank the reviewers who greatly helped me to improve this text.

Return to text

1. The tapes are rather numerous but very few of them are accessible. In fact, some recordings of improvisation sessions were published as albums in the 1960s and 1970s. Some tapes and a video documentary from 1967 were published in a CD box in 2006. Some early recordings held in the RAI archive were presented for the first time at a conference in Rome in December 2017 by Alessandro Mastropietro. Some tapes are in private archives and not yet published.

Return to text

2. Stover’s (2017) article clearly addresses a more jazz-oriented improvisation; still, even though not all of these contexts apply to the music at hand in this paper—such as the relation to the tune—this gives a very good description of the immediacy and complexity that characterize the improvisational moment.

Return to text

3. For an accurate chronology and a list of performers of GINC’s early activity, see Farina 2017.

Return to text

4. “[Il New Music Ensemble] che opera in California, si può considerare il primo esistente nel sistema occidentale che lavori su schemi veramente attuali. Per la formazione di questo gruppo ‘NUOVA CONSONANZA’, il primo del genere in Europa, la presenza di Austin è stata determinante, e così altrettanto valida la cooperazione di tutti i colleghi compositori che ne fanno parte.” All translations are my own, unless otherwise stated. The program notes (dating from 1965) are held at the Fondazione Isabella Scelsi in Rome among the Nuova Consonanza papers.

Return to text

5. See, for example, the track “Es War Einmal,” which ends with a fade out: there is no way of knowing if that was actually the end of the specific session. The track is currently published in the CD box “Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza – Azioni,” together with the video used for this analysis.

Return to text

6. See, for example, the 1970 LP The Feed-Back (Gaddi 1993, 43 and 146).

Return to text

7. These principles are consistent with the general practice of Eurological collective experiences at the time (Lewis 1996); for example similar principles and patterns are found in a comparative study of AMM, Spontaneous Music Ensemble, and MEV (Saladin 2014). My understanding of the principle of action-reaction comes mainly from extensive personal discussions with Bertoncini.

Return to text

8. “Il piano non l’ho mai toccato dalla parte della tastiera perché avevo paura che gli stilemi da me immagazzinati come esecutore emergessero durante l’improvvisazione.”

Return to text

9. “Irgendwelche musikalischen Gesten waren verbannt, zu klare rhythmische Strukturen zum Beispiel, sich wiederholende rhythmische Muster, harmonische Intervalle, melodische Figuren. Und wie kann ein Musiker, wenn er zwei Noten spielt, eine melodische Figur vermeiden? Ich habe gesagt, melodische Figuren kann man mit der Hilfe der anderen Mitglieder der Gruppe vermeiden.” Translation by Dr. Isabell Woelfel.

Return to text

10. “Io ho scritto a suo tempo degli esercizi ed altri, non scritti, ne sono stati fatti, esercizi che non erano forme, non formule né schemi: erano descrizioni di comportamenti entro ai quali eravamo completamente indipendenti.”

Return to text

11. Walter Branchi in conversation with the author and Luisa Santacesaria. August 11, 2014.

Return to text

12. Besides the larger number of exercises, the main difference with Anderson’s list is that she includes among the exercises that of playing an unfamiliar instrument in order to avoid musical stereotypes. However, as argued above, this is not a widespread habit among the members (see Bertoncini’s quote on the issue reported above). Furthermore, in Anderson’s list, the role of volume and intensity of the reaction to an idea is mentioned but does not have the core function suggested by Branchi; this is a new and important element for analytical purposes. For the importance of preparatory sessions and the use of the exercises see also Pustijanac (2016, 11–12).

Return to text

13. “Questo esercizio con queste limitazioni ti costringeva ad ascoltare gli altri, per forza. Perché non potevi fare certe cose, non potevi essere il solista, anche se la proposta veniva da te. Anche perché la proposta non era fatta e poi lasciata, veniva portato avanti il discorso, fino a che la proposta non si concludeva musicalmente e gli altri dovevano concludere, anche. . . . Questo era l’esercizio secondo me più importante perché costringe ad ascoltare, a costruire su materiale dato che è quello che tu non sai cosa sarà, che viene dall’altro.”

Return to text

14. “Sarà chiaro il momento in cui la mia proposta si chiude, tant’è vero che subito seguirà la proposta del successivo in maniera continua. Questo comporta per lo meno due vantaggi: di obbligare ad interagire e di obbligare ad ascoltare tutto ciò che sta succedendo—cosa che spesso non avviene con gli esecutori i quali tendono ad ascoltare se stessi, la propria proposta senza accorgersi di ciò che stanno facendo gli altri.”

Return to text

15. This is not entirely true. Some of the NME members were composition students at the University of California Davis.

Return to text

16. “Loro [NME] avevano esecutori bravissimi, che però non erano compositori. Quindi c’era un atteggiamento nell’improvvisare piuttosto basato sul solismo e il virtuosismo mentre il punto fondamentale in Nuova Consonanza era mettere insieme dei compositori, anche persone come Franco [Evangelisti] che suonavano pur non essendo prettamente degli esecutori.”

Return to text

17. “Molto era anche basato sull’ascolto. Cioè le improvvisazioni che noi facevamo, soprattutto quelle che erano esercizi, venivano riascoltate sempre alla fine, venivano discusse. Cioè si diceva, ‘Ha funzionato? Non ha funzionato? Perché non ha funzionato? Tu hai fatto questo, tu hai fatto quello. . . ’ Insomma questi esercizi erano talmente forti, talmente condizionanti che alla fine quando facevamo una improvvisazione così detta libera (cioè era deciso solo l’organico: noi tre, noi due, noi cinque ecc.), i condizionamenti erano così forti che funzionavano perfettamente. Era quasi come se stessimo parlando tra di noi.” Gaddi also discusses the importance of conversation-like performances and their occurrences in GINC (1993, 67–68).

Return to text

18. This reflection on the dichotomy performer/composer would be worthy of extensive discussion, but for the purposes of this article suffice it to say that the double profile performer/composer was probably theorized by Franco Evangelisti (starting 1959) to solve the problems posed by aleatoric works. According to him, being trained as composers helped GINC members become more aware of the qualities of the material chosen, and especially gave them more tools to follow the basic rules that were at the basis of the group, such as the lack of repetition and the quest for asymmetry.

Return to text

19. This increase in activity before a public session is not unusual for the group. Egisto Macchi recalls that before his first concert with GINC, they worked continuously, three or four times a week from June to September. (Macchi in Gaddi 1993, 169). This contradicts Christine Anderson, who reports that GINC met for sessions once per week (Anderson 2013, 374).

Return to text

20. This particular sound production is eventually described by Mario Bertoncini: “We amused ourselves, for example, by rubbing cardboard tubes against the floor, if the floor was suitable, or against the piano. I was doing duets with John at the trombone, releasing through these tubes [elephant-like] growls; it sounded like a tuba. We debunked both the humility of the floor and the nobility of the classical instrument” (Bertoncini in Gaddi 1993, 144; “Ci divertivamo, per esempio, con dei tubi di cartone sfregandoli sul pavimento, se questo era adatto, o nel pianoforte. Facevo dei duetti con John al trombone, sprigionando per mezzo di questi tubi dei ‘barriti’ analoghi: sembrava una tuba. Smitizzavano sia l’umiltà del pavimento che la nobiltà dello strumento classico”).

Return to text

21. The use of the mouthpiece is recurrent in GINC improvisations (see Gaddi 1993, 99)

Return to text

22. “Intorno a questa serie di regole non scritte ruotano molte delle interminabili discussioni suscitate durante le sedute di prova. L’integrazione è possibile finché l’attività di ognuno, confrontandosi con tali obblighi, riesce a trovare un proprio spazio di espressione, finendo, talvolta, anche col capovolgere furtivamente questi precetti, che sono ben lungi dall’essere dogmatismo.”

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2019 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

10241