What is Musical Meaning? Theorizing Music as Performative Utterance*

Andrew J. Chung

KEYWORDS: musical meaning, semiotics, J. L. Austin, performative utterance, speech-act theory, philosophy of language, experimental music

ABSTRACT: In this article, I theorize a new conception of musical meaning, based on J. L. Austin’s theory of performative utterances in his treatise How to Do Things with Words. Austin theorizes language meaning pragmatically: he highlights the manifold ways language performs actions and is used to “do things” in praxis. Austin thereby suggests a new theoretic center for language meaning, an implication largely developed by others after his death. This article theorizes an analogous position that locates musical meaning in the use of music “to do things,” which may include performing actions such as reference and disclosure, but also includes, in a theoretically rigorous fashion, a manifold of other semiotic actions performed by music to apply pressure to its contexts of audition. I argue that while many questions have been asked about meanings of particular examples of music, a more fundamental question has not been addressed adequately: what does meaning mean? Studies of musical meaning, I argue, have systematically undertheorized the ways in which music, as interpretable utterance, can create, transform, maintain, and destroy aspects of the world in which it participates. They have largely presumed that the basic units of sense when it comes to questions of musical meaning consist of various messages, indexes, and references encoded into musical sound and signifiers. Instead, I argue that a considerably more robust analytic takes the basic units of sense to be the various acts that music (in being something interpretable) performs or enacts within its social/situational contexts of occurrence. Ultimately, this article exposes and challenges a deep-seated Western bias towards equating meaning with forms of reference, representation, and disclosure. Through the “performative” theory of musical utterance as efficacious action, it proposes a unified theory of musical meaning that eliminates the gap between musical reference, on the one hand, and musical effects, on the other. It offers a way to understand musical meaning in ways that are deeply contextual (both socially and structurally): imbricated with the human practices that not only produce music but are produced by it in the face of its communicative capacities. I build theoretically with the help of various examples drawn largely from tonal repertoires, and I follow with lengthier analytical vignettes focused on experimental twentieth and twenty-first century works.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.25.1.2

Copyright © 2019 Society for Music Theory

0. Preliminaries

[0.1.1] While music theorists and musicologists have asked many questions about the meanings found in particular pieces of music, and how they got there, less thoroughly have scholars interrogated what it is for music to be meaningful. This article develops such an account, based upon theories of language efficacy offered by ordinary language philosophy—in particular, J. L. Austin’s idea of performative utterances ([1962] 1975). Via this thought, I argue that musical meaning is best understood not as a matter of how musical structures, objects, or processes represent, refer to, or otherwise map onto, either extramusical or music-internal correlates. It is better understood as a matter of how music, as something we can interpret, is used to generate effects and to perform meaningful actions with meaningful consequences, to which we find ways to comport our listening, performing, or otherwise “musicking” selves, to use a coinage of Christopher Small’s.(1) This way of thinking posits that the categories we frequently appeal to when discussing musical meaning—expression, disclosure, referentiality, symbolism, signification, and the like—are limited in their adequacy to address musical meaning. These are simply a few ways to negotiate the pressures applied to us by the communicative efficacy and actional character of music’s “utterances,” albeit historically and discursively important ones.(2) A more robust position is to take the acts that music performs within the contexts in which it occurs as the basic units of sense for the inquiry into musical meaning. Considering theories of Austin’s performative language theory, I argue that the linguistic turn in musical studies—and more recent disavowals of it—need to be rethought, and I propose that the concept of music as performative utterance supplies the condition of possibility for music’s meaningfulness.

[0.1.2] The task of this essay is not to make metaphysical or ontological pronouncements claiming that music is utterance, that it is communication, or that it is language-like, and it certainly does not endorse the notion that music is reducible to or exhausted by its meaning. Instead, this essay has the more modest goal of defending an account of what exactly is taking place if we choose to construe music as meaningful, when we find it to be communicative, when we decide to consider it as utterance, and when we endorse some version of the idea that music gains richness and contour through its meanings (without denying that rich surpluses exceed them). The difference between these two sorts of claims is that the metaphysical/ontological claim would profess to be true regardless of whether or not one accepts the music-language analogy and the model of music as communication or utterance. Yet, for music to be able to mean, communicate, or utter at all requires a cooperation on our part, to hear and interpret it as such. The metaphysical/ontological claim is incoherent: a signal, such as a beep from a household appliance, is not a signal in virtue of some sort of deep, ultimate identity we can appeal to—it can only function as a signal for us if we are disposed to relate to it in that way.

[0.1.3] It is certainly far from universally accepted that verbal utterance and linguistic communication are universally valid, incontrovertible models for understanding music. Indeed, rejecting these models seems to be increasingly popular, with numerous examples of recent scholarship abandoning music-language parallels along with notions of “meaning” and semiosis. I want to return to that fork in the road to rethink what was jettisoned there when Joseph Kerman’s (1980) disciplinary injunction towards criticism, hermeneutics, and meaning was unshouldered, and to consider what may never have been fully picked up at all. I sympathize with the desire to question the long-standing privilege of representation in humanistic thought, but I remain wary of the pendulum’s swing in the opposite direction towards the nondiscursive, non-semiotic aspects of music and its ineffable sensuosity. The arc of a pendulum, of course, passes through a territory between the vertices of its swing: at the bottom of the pendulum’s arc is where it has the most momentum. My goal is to theorize this in-between and to interrogate the impetus to “get out” of the semiotic (or to dig our heels into it). Clarifying a more robust center from which to evaluate the music-language/utterance/communication analogy will enable us to accept or reject that model on more reflective grounds.

[0.1.4] Extrapolating from Austin’s work provides a theory of musical meaning based on an intuitively familiar idea: music performs actions and has effects for its listeners. Austin’s performative language theory occasions a deeper consideration of the “performative” as an analytic rubric, a consideration that extends beyond more familiar applications of the term, which include the study of music in performance, musical performers, and the musical performance network. It clarifies distinctions between meanings that can be assimilated to music’s representational capacities, and ones that, strictly speaking, cannot. It makes precise distinctions between the acts that music performs and the effects it can lead to and theorizes the conditions under which these can arise.

[0.1.5] Below, I will first demonstrate some theoretical lacunae to which prevailing conceptions of musical meaning fall victim, before summarizing major points and implications of Austinian theory and ordinary language philosophy more broadly with a diversity of basic musical examples. I will analyze the entangled multiplicity of ways in which the terms “performative” and “performativity” have been construed before offering a set of maxims about musical meaning based on Austin’s theorization of language efficacy. Finally, I will offer brief analytical vignettes of pieces by European composers Michael Beil and Peter Ablinger to demonstrate a few ways in which conceptual tools drawn from Austinian theory and ordinary language philosophy might provide analytic points of entry into music that places conceptual roadblocks before standard hermeneutic circumspection and forms of score-based analysis. It will be impossible to treat this topic comprehensively in a single article, so the goal here will be to simply motivate and explain some resources for more powerfully thinking musical meaning, thereby suggesting further avenues for application that will have to go underexplored.

[0.1.6] For the purposes of this article, music will not be taken as an abstract entity. It will be considered in terms of real instances of its taking place, or real acts of its being imagined to take place. I aim to define “musical sound” in great generality without erecting any categorically exclusionary borders as to what does and does not count as music. My particular training and expertise lead me frequently to discuss works and performances. The Western work concept will be implicit across much of the discussion. However, I by no means endorse the view that music is a universal, transhistorical doing answerable always to Western ideas of works, and I reject the idea that it is a practice that all cultures (either across the world or across time) construe in the same way according to the same definitional constraints. The extent of music’s separateness from other practices—such as language, science, exhibition artwork, dance, theater, ritual/theological practices, etc.—has always been up for contestation, and the lines are drawn differently depending on which cultures or authorities one consults on this matter. What I do maintain is that any occurrence of real or imagined musical sound considered as such, however defined, is a doing (rather than, strictly, a thing) that interfaces with the goals, concerns, and activities of its practitioners. The goal of this essay is to theorize robustly how meaning comes from that doing. First, however, it is necessary to clarify the shortcomings of prevailing orientations towards musical meaning.

1.1 Meaning-as-Mapping

[1.1.1] In recent years, it has become increasingly common among some music scholars to take their leave of ideas of musical meaning, music-language parallels, and the investigation of music in view of its semiotic aspects. Clemens Risi writes: “Using the theories of performativity as a starting point, a shift of the theoretical and analytical perspectives takes place: the transition from representation to presence, from referentiality to materiality, from symbolic sense and semiotic meaning to experience and sensual feeling” (2011, 285). In Sensing Sound, Nina Eidsheim remarks in a similar hue: “Trapping music in the limited definition that follows from [what she calls] the figure of sound (that is, a stable signifier pointing to a static signified) constitutes an unethical relationship to music. According to my definition, having an ethical relationship to music means . . . realizing that music consists not only of inanimate materials, but also of the materiality that is the human body” (2015, 21).(3) These are strong claims against investigating categories of musical meaning. In Risi’s view, these categories pertaining to meaning are buttressed by shopworn and dissatisfyingly abstract perspectives. In Eidsheim’s view, their very use in our discourses might enact a disfiguring and unethical violence to the sensuous fact of music’s materiality and embodiment, siphoning our attention away from the ways in which sonic vibrations produce material effects on others.(4)

[1.1.2] Other scholars, however, continue to embrace the study of music’s parallels to language and its signifying character, as the enthusiastic development of topic-theoretic research, studies of musical narrativity, and continued hermeneutic work attests. This antagonism around the axis of the linguistic turn reflects recent trends in humanistic thought broadly. As literary theorist Toril Moi puts it, “a number of new theory formations—affect theory, new materialism, posthumanism, and so on—began their struggle to throw off the yoke of the ‘linguistic turn,’” in contrast to those who continue to seek meaning and signification in literature and culture (2017, 17).(5)

[1.1.3] Both styles of thought schematized above, either in moods skeptical towards or welcoming of the linguistic turn, actually share a deep commonality. Both tend to construe forms of reference, representation, and disclosure (structured in the image of the signifier-signified relation), to be paradigmatic of meaning as such.(6) This paradigm, which I will call the ideology of meaning-as-mapping, can be observed in two forms. One form involves maneuvers like construing musical meaning in terms of expressive contents that music maps to, mapping music’s formal features to a narrative, identifying the disclosure of philosophical commitments in musical sound, and so forth. Diverse scholarly programs invoke iterations of this structure as a foundational premise even as they look far beyond it: from Adorno’s (1978) idea of social exigencies being expressed immanently in music,(7) to the criticism and hermeneutics that Joseph Kerman (1980) called for some years later; from studies of musical narrativity and topic theory, even to cognitive metaphor theories of musical gesture.

[1.1.4] Another form of this paradigm posits meaning-as-mapping as the underlying framework in order to neutralize it. Some scholars motivate materialist, affective, and “performative” paradigms by elevating their virtues above those of representation, reference, and semiotic meaning. Leo Treitler describes the related view that “music is said to be otherworldly and inscrutable, to demand exegesis and defy it. In the very posing of the question of meaning there is an implication of its pointlessness, of the impossibility of finding answers” (2011, 4). Advancing the idea that music is a system of empty or floating signifiers without signifieds, or a sensuous medium that constantly exceeds signification is, however, still to construe the signifier-signified mapping as the essence of musical and linguistic signs.(8) This view takes the declarative, propositional semantics of assertions as the essence of language meaning, adding the proviso that music can only ever approximate denotative or connotative functions of language, if it can at all. Within this logic, one of the foundational assumptions is, to ventriloquize Moi, “that language [or music] as such either ‘refers’ or ‘fails to refer.’ It is as if ‘language’ [or music] just sits there as a huge, lumbering structure that constantly refers, or fails to” (2017, 121).

[1.1.5] Meaning-as-mapping, in other words, is a framework in which the basic units of sense are referential, symbolic, or semantic relations. Granted, this idea is typically heavily qualified. Lawrence Kramer writes: “What is objectively ‘present’ in the work . . . is not a specific meaning but the availability or potentiality of meanings” (2002, 118). Carolyn Abbate (2004, 516) looks to Jankélévitch to affirm that musical meaning in its pluripotentiality arises in the messy and contingent interface between listening subject and sounding music, not in some sort of immanent encoding.(9) But these are still affirmations of meaning-as-mapping that supplement meaning-as-mapping with additional structure. This framework invokes a dichotomous logic that separates what music “says” or “tells” from what it does.(10)

[1.1.6] This essay develops another path altogether, inspired in part by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s strategy of rejecting both the embrace of and turn away from an idea on the grounds that both hold in common a limited picture of the idea in question (see Moi 2017, 12). Leonard Meyer isolates the crux of this limited picture of musical meaning-as-mapping: “The debates as to what music communicates have centered around the question of whether music can designate, depict, or otherwise communicate referential concepts, images, experiences and emotional states” (1956, 32). If we presume this picture of music’s meaning and communicative potential as a given fact, certain conceptual problems arise.

1.2 The Problem of Musical Meaning

[1.2.1] Meyer makes a startling claim: “Because it has not appeared problematical to them, referentialists have not as a rule explicitly considered the problem of musical meaning” (1956, 33).(11) I take Meyer to be saying that a variety of questions have been asked about how music refers to the world, while certain more fundamental questions remain to be addressed. In order to advance any claims about the meanings we find in music, what is first required is an understanding of meaning. The concept of meaning acts as a handy tool for the challenge of uncovering meanings from often recalcitrant and always semantically underdetermined works and musical phenomena.(12) Any subsequent arguments, whether for or against a notion of musical meaning outside of itself (or at all), therefore always proceed from certain presumptions concerning what meaning means—what it is for something to mean, what it means for music to say something, how we ask about meaning, and even how we might quarantine musical meaning and cast it off from our concerns. Thus, inquiries frequently race past a yet more fundamental question: What is it for music to have meaning? This derives from a question of greater generality: What does meaning mean?(13)

[1.2.2] These are vexed questions. To mean serves a sort of copular function in this thinking: too basic and fundamental to grasp analytically. Meyer lamented “a lack of clarity as to the nature and definition of meaning itself” (32), and an element of the difficulty he points out stems from the fact that a preunderstanding of meaning is the condition of possibility for setting into motion any questions about meaning to begin with. There is a structural problem to the question of “what meaning means” and others like it. As philosopher Mary-Jane Rubenstein explains, the thing which “stands under every investigation is precisely what investigation cannot understand” (2012, 2). The question “what does ‘meaning’ mean?” makes significant presumptions at the instant it is asked because its very form is structured according to a referential logic that seeks the [“what”] that maps to [the concept of meaning] through the relation designated by the verb “to mean.” The referential logic and mapping-based form of the question make it difficult to separate referential mapping from meaning as such.(14)

[1.2.3] Wittgenstein once wrote: “A picture [of what meaning consists in] held us captive. And we couldn’t get outside it, for it lay in our language, and language seemed only to repeat it to us inexorably” ([1953] 1958, §115). That is, it is impossible to approach the topic of musical meaning in scholarly discourse innocent of preconceptions about meaning. Because these discourses take place in language (albeit language about non-language), we will genuinely find ourselves running up against connotations that adhere viscously to a vocabulary more suited to received notions. We see straight past our preconceptions regarding “meaning” and related terms because we are accustomed to their stickiness and hence they resist becoming apparent. This amounts to a forgetting of meaning as such. Recognizing this forgetting, however, marks an opportunity to better see the foundational assumptions and presuppositions we make about meaning and how we ask about it, to see these naturalized habits as ideological, to see their distorting effects—and to see alternatives.(15)

[1.2.4] Let me adapt a metaphor from Heidegger’s thinking. Musical meaning is a tree that grows leaves such as New-Musicology-style hermeneutics, post-Nattiez music semiotics, 18th-century musical topic theory, accounts of gestural meaning and narrativity—and even the turn towards music’s sensuous ineffability, away from the investigation of meaning. We can learn something of the tree from sampling its leaves. But beneath lies a soil from which the tree nourishes itself—a soil that remains concealed and buried when we approach from the canopy, branches, bark, and roots. We cannot properly assay this soil until we have a way of pushing past meaning-as-mapping.

2.1 Ordinary Language Philosophy: Meaning-as-Use

[2.1.1] Oxford philosopher of language J. L. Austin theorized an alternative to meaning-as-mapping, arguing for meaning-as-use in his treatise, How to Do Things with Words ([1962] 1975), from which developed the concepts of speech-acts and performative utterance. His work shares certain deep affinities with the work of Wittgenstein in Philosophical Investigations ([1953] 1958). They develop versions of the radical position that meaning is not primarily about mappings between signifiers and signifieds, but that it is fundamentally about the uses, effects, and actions that utterances are recruited to perform, in concert with the care we exercise over how they affect our goals, concerns, and activities we are involved with. These are pillars of what is now known as ordinary language philosophy: a philosophy of language that derives its insights not from analysis of language’s abstract structures, but from the ways language is actually deployed in daily life.

[2.1.2] Ordinary language philosophy challenges the doxa that words and sentences “simply have a given core meaning,” as Moi (2017, 40) puts it, showing how the circumstances of use imbue language with meaning in a myriad of ways. This insight implies that the primary distinction recognized between music and language—that language involves one-to-one mappings between signifier and signified while music cannot—relies upon a characterization of language that language itself regularly contravenes. Ordinary language philosophy suggests ways to construe the music-language metaphor in ways that are not hampered by the shortcomings of this picture of language meaning. An analogous conception of musical meaning neither rejects nor invalidates insights based on meaning-as-mapping, but simply draws a wider circle around them, logically subsuming them.

[2.1.3] By theorizing the communicative functions of music-as-utterance using ordinary language philosophy’s concept of performative utterance, I propose that ideas of musical effects and musical signs are not incommensurable or antinomic. Music’s efficacy might have precisely to do with ideas of musical meaning and the semiotic, language-character of music, not just its sensuous immediacy. I propose that what counts in a discourse on musical meaning might concern much more than, for instance, the disclosure of narratives within sonata movements, or how a composition’s harmonic devices might comment on the political circumstances of its era. Musical meaning is underwritten by praxis: how we use music to do things and how we comport ourselves to the pressures that musical meaning applies to our goals, concerns, and activities.

[2.1.4] A number of predecessors in the field directly inspire the Austinian focus of this work. Ethnomusicologists Judith Kubicki (1999), Deborah Wong (2001), and Jim Sykes (2018) invoke Austinian theory to analyze ritual efficacies of Taizé liturgical singing, courtly Thai Buddhist performances, and Sri Lankan berava music, respectively.(16) Philip Rupprecht (2001) analyzes musical settings of speech-acts in Britten’s libretti. Justin London (1996) and music sociologist Tia DeNora (1986) both suggest that the music-language metaphor can be made more robust by expanding beyond semantic theories to consider pragmatic theories of speech-acts.(17) Austin’s work can be generalized for musical study, towards approaches including and beyond music-text relations, targeted approaches to fieldwork, and hermeneutic claims. Ultimately, without a use-theoretic perspective on musical meaning, we do not possess a framework adequate to the notion that music can even mean anything at all, except in a limited sense.

[2.1.5] The theoretical account of the grounds of musical meaning outlined below will ultimately resemble what philosophers of language call a “foundational theory” of meaning: not a theory devoted to accounting for any particular meanings that we may find and how they got there (a “semantic theory”), but one that provides an account of the underpinnings in virtue of which there can be meaning in the first place.(18) As such, this project does not amount to the construction of a machine that processes musical works or performances (or fragments of them) and extracts nuggets of meaning. It offers little in the way of pronouncements on method or musical analysis. Instead, it will provide a foundational account of what it is to construe music as meaningful, will provide a robust theoretical account of music’s communicative actions and efficacies, and will advance an argument that will enable us to consider what music “says” and what it “does” in a unified fashion.

2.2 Austin’s Speech-Act Theory within Ordinary Language Philosophy

[2.2.1] Austin’s theoretical project in his seminal treatise, How to Do Things with Words, centers around a particular historical corrective: “It was for too long the assumption of philosophers that the business of a ‘statement’ can only be to ‘describe’ some state of affairs, or to ‘state some fact’, which it must do either truly or falsely” ([1962] 1975, 1). Somewhat earlier, Wittgenstein pointed out similarly that we have fixated upon dealing with meaning “as if meaning were an aura the word brings along with it and retains in every kind of use” ([1953] 1958, §117). Austin refers to this tendency as a sort of “descriptive fallacy” ([1962] 1975, 3) originating in a fixation upon what he calls the constative dimension of utterance: what utterance discloses and how it references states of affairs in the world. But, he observes, “it has come to be commonly held that many utterances which look like statements are either not intended at all, or only intended in part, to record or impart straightforward information about the facts” ([1962] 1975, 2). That is, declarative statements typically do more than simply declaring or stating. They also possess efficacy and they can do things, “prescribing conduct or influencing it in special ways” ([1962] 1975, 3).

[2.2.2] Austin refers to this dimension—in which we “do things with words” and create effects with them—as the “performative” dimension of utterance, in contrast to its constative dimension. His fundamental point is that language not only represents or discloses the world, but that it also has a (per)formative effect in creating, destroying, transforming, or maintaining aspects of reality. Preliminarily, Austin gives the following examples of performative utterances or speech-acts:(19)

- Saying “I do” at one’s wedding to effect the marriage, rather than to merely predicate about it.

- Saying “I name this ship the Queen Elizabeth” as when smashing a bottle of champagne against the hull of the vessel to perform an act of naming/christening.

- Writing “I give and bequeath my watch to my brother” in one’s last will and testament to perform the act of bequeathing.

- Saying “I bet you sixpence it will rain tomorrow” to actually make the bet and not merely describe it (Austin [1962] 1975, 5).

[2.2.3] These examples illustrate four different acts that four specific utterances can perform, acts of: committing oneself in marriage, naming a ship, legally bequeathing a possession, and betting on an event. The particular acts that a sentence performs or is construed to perform are called the illocutionary forces or acts of a sentence: literally, what specific thing is done in virtue of a locution’s being uttered (il-locution). Promisingly for this study, linguist Manfred Bierwisch recognized: “There are many non-verbal acts having the same illocutionary force . . . as certain corresponding speech-acts” (1980, 3).(20) Austin names five classes of illocutionary acts that utterances can perform, which we can examine for present purposes by way of some basic musical examples. I use Austin’s taxonomy (rather than others which have since been proposed) not because his stands as the final word on grouping different illocutionary acts into distinct families, nor because their names are particularly important, but simply to illustrate a variety of ways in which speech-act theory can translate into construing music as utterance.

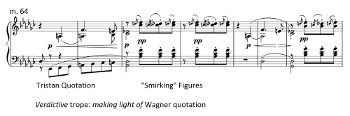

Example 1. Debussy, Golliwog’s Cakewalk, mm. 64–70, illustrating a trope used as a verdictive act of musical utterance

(click to enlarge)

[2.2.4] Illocutions of Austin’s first category are called verdictives, acts in which utterance is used to place judgment upon phenomena. One example of a musical verdictive might be in the quotation of Wagnerian voice-leading and seventh-chord syntax in Debussy’s “Golliwog’s Cakewalk,” and the “smirking” jocular figures that follow (Example 1). Debussy juxtaposes the gravitas of the Tristan quotation against light figurations inspired by an American vernacular dance. This juxtaposition is an example of what Robert Hatten (2004) would refer to as a trope, combining two basic meaningful units into a more sophisticated complex. This juxtaposition amounts perhaps to an act of burlesquing: causing serious material to appear absurd or exaggerated through ironic or parodic juxtaposition with comic material (recall that Debussy’s performance markings hyperbolically read “avec une grande émotion” here). Whether or not Debussy’s quotation was intended as a mockery of Tristan and Isolde or was meant as a value judgment upon it, the conditions under which we interpret it include our contextual enculturation into practices of irony and parody presumably shared by the composer in his context. This trope of the Wagner quotation (initially at the pc-level of the original Tristan chord) and the smirking figures, by virtue of the norms of irony and parody, can plausibly be interpreted as an act of making light of the Tristan quotation. The verdictive act performed in this quotation brings with it the performance other simultaneous acts—for instance, quoting, depicting, or reminding audiences of Richard Wagner. Moreover, any given performance of the piece may further accomplish a variety of situationally contingent acts.

Example 2a. Tristan Prelude mm. 15–23, original

(click to enlarge)

Example 2b. Tristan Prelude mm. 15–23 (piano reduction) recomposed to break a commissive act

(click to enlarge)

[2.2.5] Another of Austin’s categories of illocutionary acts is the category of commissives, acts in which utterance is used to commit to certain courses of action. In this connection, we might think of a simple dominant pedal in Western tonal syntax. It sets up a psychological expectation further buttressed by its syntactical function and its phrase-rhythmic weight, thereby committing to certain courses of metric, harmonic, and voice-leading action. It gives something like a promise to resolve in a certain way at a certain time—a promise which may be kept, deferred, or broken (though a lack of expected resolution is hardly the moral equivalent of a broken promise). The depiction of longing, so commonly attributed to Tristan and Isolde, depends precisely on the commissive, promissory force of the many dominants it approaches over its course. We might say that the Tristan Prelude’s repeated acts of withholding resolution to local tonics accumulate. They collectively perform a higher-order act of committing to an idiom of tonic evasion. The Prelude’s mm. 15–23 is given in Example 2a. Listening from the beginning of the prelude, consider how disjunctive it would be for the 4–3 suspension onto dominant-functioning B major at m. 23 to resolve “properly” to E minor before taking off in a chromatic ascent into m. 24, as recomposed in Example 2b. The bizarrely hollow quality of this resolution is at once a recognition of an act of committing to an idiom in the first twenty-two measures, and the disavowal of that commitment at m. 23.

[2.2.6] Closely related to commissives are what Austin calls exercitives, acts in which utterance is used to exercise power or influence and avow the consequences of that exercise of influence. Austin further glosses exercitive acts as “decision[s] that something is to be so, as distinct from judgment[s] that it is so” ([1962] 1975, 155). In this connection, we might return to the Tristan Prelude. Its continual evasions of local tonics—in favor of transposed approaches to the dominant, deceptive resolutions, tonal non-sequiturs to foreign dominants and the like—function to normalize the cadence-avoiding idiom of the opera. In these evasions of tonic arrival, there is a decision that a certain harmonic and contrapuntal state of affairs is to be so for the duration of the work (it inaugurates a condition of longing for constantly-evaded tonics), and that a syntactical state of affairs governed by traditional diatonic procedures of phrase structuration/succession was not to be so. For further illustrations, we might think of more functional uses of music, like the use of military marches to coordinate troop movements and footfall, or how the playing of reveille acts as a signal at countless sleepaway camps to start one’s day. Note here that whether one is evaluating concert music in ways that theorists and musicologists are accustomed to doing, or evaluating “functional” musics, the Austinian perspective partially flattens this distinction and describes both in terms of music being used to accomplish various things and as taking place against the backdrop of our goals, activities, and concerns.

Example 3. Carter, Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux I, mm. 1–6. “Boulez” cipher as AITC, used as a behabitive act of celebration/commemoration

(click to enlarge)

[2.2.7] Verdictives, commissives, and exercitives are followed by what Austin calls behabitives, acts in which utterance is used to accomplish certain social functions in reaction to the behavior of others as in thanking, congratulating, welcoming, and so forth. As simple examples, we could cite as musical behabitives the three pieces Elliott Carter wrote for birthdays of Pierre Boulez: Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux I (1985, flute and clarinet), Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux II (1994, flute, clarinet, and marimba), and Retrouvailles (2000, piano solo). All three pieces start with an all-interval tetrachord (AITC; set-class 4-z29), one transposition of which forms a musical cipher for “Boulez,” using a mixture of French and German note names: B-(flat) [o], U(t), L(a), E [z] =

[2.2.8] Finally, illocutions of Austin’s fifth category are called expositives, and these analogize to acts of reference, expression, and disclosure through music. Thus, any uses of music to refer to things, like the oft-cited parade of topical references at the opening of Mozart’s F-Major Sonata, K. 332, are acts of reference and uses of musical sound to point to particular extra-musical signifieds.(23) This fifth category hints at a major implication of Austin’s thought, which is that constative tasks of referring to, and predicating about states of affairs are always already performative utterances because they are acts.

[2.2.9] Austin found that many sentences without the explicit structural characteristics of performative formulas (such as his initial four examples of performative utterances), nonetheless implicitly perform speech-acts anyway.(24) For instance, in saying, “I’m cold,” you may implicitly be saying, “I hereby request that you shut the window,” “I assert that I am aware of the temperature,” “I judge the caulking to be shoddy,” all of the above, and so on.(25) Whatever particular illocution the utterance of “I’m cold” performs will be a matter of a variety of contextual features, and any particular utterance may perform multiple different illocutionary acts simultaneously.

[2.2.10] It is not simply the case that a speech-act works by virtue of being uttered; certain social conditions allow or otherwise help an utterance to perform certain acts, and thereby to result in its effects. In the literature on speech-acts and performative utterances, the situational conditions that encourage or allow for the successful accomplishment of performative speech-acts are called their felicity conditions ([1962] 1975, 12–24). Thus, one cannot sentence a prisoner to death without being a judge, nor can a judge utter “I hereby sentence you to die by hanging” without doing so as the judge in a capital punishment proceeding and without having been first delivered a corresponding verdict by the jury.(26) Similarly, to return again to Debussy and Tristan, the fact that mm. 2–4 of Golliwog’s Cakewalk enharmonically respells the first instance of the Tristan chord (F,

[2.2.11] The efficacy of speech-acts stands to be determined in terms of appropriateness and inappropriateness to context as well as effectiveness or ineffectiveness in context.(28) As Pierre Bourdieu explains, this efficacy “does not reside . . . in the discourse itself, but rather in the social [felicity] conditions of production and reproduction of . . . language” (1991, 113). Bourdieu continues, “the symbolic efficacy of words is exercised only in so far as the person subjected to it recognizes the person who exercises it as authorized to do so” (116). The potentials for musical utterances to perform various illocutionary acts are not inherent properties of the music itself, nor are they under the sole authorship of a composer’s intentions. They instead require an implicit “ratification” as well by the jury of the public to whom they are addressed. This “ratification” occurs via our proclivities to recognize these acts and respond appropriately, even if implicitly.

[2.2.12] As literary theorist Douglas Robinson contends, “There is no such thing as an utterance that does not perform a speech act. All language does things. All saying is also a doing” (Robinson 2005, 45). There is no such thing, then, as categorically “performative music” or “constative music.” Anytime music is interpreted as meaningful, we are catching it in the act of a doing. Likewise, there is, strictly speaking, no such thing as “performative musical analysis” or “constative musical analysis”—although the analyst certainly may adopt a primarily performative-based or constative-based attitude. Jeffrey Swinkin demonstrates this attitudinal shift: “Take a structural attribution in the form ‘musical entities x and y are related in z way’. . . . I argue that one does better to view this attribution not as an objective fact but as an implicit directive [an exercitive act]: ‘hear x and y as related in terms of z; imagine that relation obtains. . . . It implicitly beseeches the listener to hear something a particular way” (Swinkin 2016, 21–22). Performativity and constativity are best understood not as taxonomic designations. They instead name attitudes of taking interest in music in view of its performative action-character and efficacy, or in view of its constative capacity to disclose and depict.

2.3 Two Further Refinements: The Act-Effect Distinction and the Status of Intentions

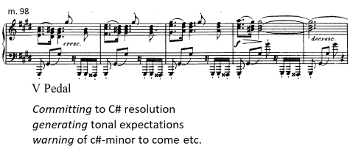

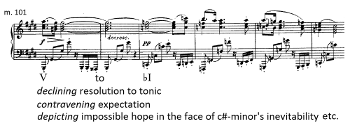

Example 4. Schubert D. 960/ii, mm. 98–102, illustrating some illocutionary acts performed by the dominant pedal

(click to enlarge)

[2.3.1] Illocutionary acts should be distinguished from what are called their perlocutionary effects—literally, what effect is achieved by the locution’s being uttered (per-locution). Austinian theory makes the crucial insight that the acts produced by an utterance are distinct from the effects they engender. Consider the moment in the second movement of Schubert’s D. 960 piano sonata that begins with the dominant pedal on

[2.3.2] Perlocutionary effects are considerably more theoretically slippery than illocutionary acts—one reason why it stands to reason that the lynchpin of Austin’s theory of speech-acts is not the theory of language’s effects per se but the illocutionary theory of actions and their relation to various effects. Suffice it to say for now that some perlocutionary effects may be expected, intended, or conventional, while others may be less so. The turn to C major as above may (predictably) cause a listener to experience surprise, possibly astonishment; it might cause an analyst to think back to the corresponding spot in the A-section when a G# dominant gave way to E major; it is conceivable (but much less likely) that it could cause one to experience fright because of a peculiar association between C major and a childhood trauma, for instance. These possibilities demonstrate simply that perlocutionary effects are deeply contingent and demand to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.(29)

Example 5. Schubert D. 960/ii, mm. 101–106, illustrating some illocutionary acts performed by motion from V to

(click to enlarge)

[2.3.3] We can speak of the movement here from V to, literally,

[2.3.4] For the study of music’s communicativity, Austin’s concept of illocutionary acts provides an important insight: musical utterances perform actions beyond the level of intramusical mapping and extramusical reference, on the one hand, and its affective, psychological, motoric, behavioral, emotional, ideational consequences, on the other hand. These two dimensions were recognized in Schubert’s time as criteria for musical meaning, as in a famous letter of Mendelssohn’s concerning meanings in his Songs without Words: “The thoughts which are expressed to me by music are not too indefinite to be put into words, but on the contrary, too definite. . . . The same words never mean the same thing to different people. Only the song can say the same thing, can arouse the same feelings in one person as in another” (cited in Treitler 2011, 5). This account is telling, despite its uncomfortably universalizing idea that musical sound always strikes people in the same ways, because it acknowledges both (constative) expression and (perlocutionary) arousal of feelings through musical sound.(30) However, the concept of illocutionary acts addresses a logical lacuna in Mendelssohn’s remarks: it enables us to recognize the actions performed by musical utterance, which are logically prior to the effects or consequences resulting from musical utterance.(31) Analysis of illocutionary acts, as distinct from their perlocutionary effects, thus enables us to bridge a gap between musical denotations/connotations and their consequences, effects, and affective perlocutionary results.

[2.3.5] Another refinement to the theoretical framework sketched above concerns the status of the meanings intended by speakers, composers, performers, writers, and analysts. The speech-act theoretic perspective would imply that the intentions of speakers and composers alike do not hold a monopoly on meanings. Yet, it seems absurd to say that intended meanings do not matter at all, dispossessed in favor of utter contextualism. The efficacy of performative utterances cannot be totally known and controlled by a willful subject, but neither can responsibility for speech-acts’ effects be placed entirely on the abstract shoulders of “context.” (32) The agency and efficacy of performative utterances is best understood as situated within what philosopher José Medina describes as a hybrid notion involving the “dialectical relation between contextual constraints and discursive freedom” (2006, xiii). Further questions follow from this hybrid account of utterance’s efficacy: what contextual features (and which contexts in the first place) encourage us to perceive and take an interest in some illocutionary forces of an utterance over all the others, and what relevant perlocutionary sequellae follow? When are intended meanings sufficient to analyze the efficacy of utterances, and when do the meaningful efficacies of utterances exceed intended functions?(33) For whom, and under what conditions, do music’s action’s result in certain meaningful consequences rather than others?

[2.3.6] Austin’s novel way of studying language (by looking at the actions that language performs in ordinary situations of its usefulness) has dramatic implications, including an important figure-ground reversal. The uses of signs—to create, transform, maintain, or destroy various conditions in the world through their efficacy—do not simply accrue on top of what they “say” or “mean,” as the old view would have it. Instead, “saying” and “meaning” are fundamentally uses to which sign are put (uses which might amount to further acts). Judy Lochhead points out that recent philosophy, including Austin’s, “recognizes that words do not transparently represent the world; rather, they contribute to the fabric of the world in a dynamic and ongoing process of discourse,” (Gallope et al. 2012, 235). Linguistic anthropologist Michael Silverstein words it more strongly: “Reference itself is just one, perhaps actually a minor one, among the ‘performative’ or ‘speech-act’ functions of speech. We often use basically ‘descriptive’ linguistic structure to accomplish other communicative goals; description happens to be one of those goals, one that overlaps in formal structure of signals with other functional ends” (1976, 14).

[2.3.7] In their challenge to the paradigm of meaning-as-mapping, Austin and Wittgenstein expose the ideological character of the prioritization of the constative functions of signs, thereby disrupting the smooth , tacit operation of this ideology.(34) As philosopher Nancy Bauer argues, Austin’s theoretical pursuits point “to a dimension of our sentences apart from which they not only would not do anything but also would not mean anything, except, perhaps, in seriously impoverished ways” (2015, 88). Speech-act theory certainly suggests some ways to follow through on Martin Stokes’s (1994) injunction that we must look at what music does as much as what it represents. But more accurately, it proffers a new logic, allowing us to look at “representing” as one among many things one can do with music. This ultimately opens out into reordering what we think of as musical meaning by disrupting the surety with which we conflate representational structures with meaning as such.(35) The arguments advanced by ordinary language philosophy propose a fundamental philosophical corrective: that a new center within the study of language and signs might be found in the ways they are used to apply pressure to the world, and how we—as part of the world that signs help to make—find ways to comport ourselves to those pressures according to our goals, activities, and concerns.(36)

[2.3.8] Moi explains, “once ordinary language philosophy has finished its analysis, we no longer have any reason to construct an elaborate theory of how to avoid or get past representation. In other words: when representation loses its status as the definition of ‘language’ as such,’ it no longer seems urgent to elaborate complex theories to find a way around it” (2017, 14). Ordinary language philosophy invites us to thoroughly rethink how we conceive of music-language parallels and enjoins us to rethink the grounds upon which we motivate other programs of study such as affect theory or new materialist studies by rejecting those parallels.(37) Dealing adequately with the thought of Austin, Wittgenstein, and related thinkers requires us to hold in abeyance our previous intuitions about whether or not ideas of language, semiotics, and communication are productive models for understanding musical meaning. These thinkers repour the very foundations of the analogy that supports those models, and enjoin us to rethink both the acceptance and rejection of those models, since both have occurred—according to this logic—on the basis of a flawed picture of what language meaning, communication, and utterance consist in. Pace Jankélévitch ([1959] 1996) and his insistence upon an absolute difference between music and language, traversing that span may well look different from a different crossing, and when equipped with different technologies.(38)

3.1 Beyond (But Not Against!) Constativity in Musical Scholarship

[3.1.1] The bias towards thinking of the meaning of interpretable objects and utterances in a constative fashion is a deep-rooted aspect of Western thinking. The elucidation of this bias is one of Michael Silverstein’s characteristic concerns. He explains why linguistic anthropology privileges language above the other anthropologically meaningful aspects of situations in which language is produced, pointing out that:

The ultimate justification for the segmentation of speech from other signaling media lies in one of the purposive uses that seems to distinguish speech behavior from all other communicative events, the function of pure reference, or, in terms more culturally bound than philosophical, the function of description or ‘telling about’. . . . It is this referential function of speech and its characteristic sign mode, the semantico-referential sign, that has formed the basis for linguistic theory and linguistic analysis in the Western tradition. (Silverstein 1976, 14)

This suggests that tendencies to view musical meaning in similar terms—in a (relatively) referential frame concerned with getting to know what musical sound “tells” us—are likely historically and ideologically contingent consequences of the tendency to conceive of language in terms of a single chief function: referentiality. However, this by no means represents a transcultural, universal model of “the way meaning is.”

[3.1.2] We can present empirical counter-evidence to the idea of meaning-as-mapping and constativity as transcultural, universal precepts about meaning. In a working paper, Silverstein recounts some of his fieldwork in Australia:

My aboriginal friends in Northwestern Australia, for example, the Worora people, had no idea what I was talking about . . . when I said, ‘What does that mean?’ or ‘How do you say. . . ?’ . . . What’s so interesting is that the concept of giving an equivalent to something like English language or Creole meaning was not something that ever occurred to them. Or if I asked the other way around, hearing a word and saying . . . ‘What does that mean?’—I would get an answer like ‘I would never say that in front of my mother’s brother.’ (Silverstein 2014, 2)

Silverstein later concludes that his aboriginal ethnographic subjects privilege a use-theoretic concept of meaning: the way one does things with words is the most basic way for language to mean in Worora linguistic culture. He recalls: “It was their system of understanding praxis, of contextualized usage, and that was their system of meaning” (2). Silverstein in no way denies that there is a dimension of language meaning that is denotative, and semantic, and productively stands to be understood that way, but argues that the vast majority of “language-ing” (cf. Christopher Small’s musick-ing) falls outside the purview of the constative, semantic view of language.

[3.1.3] According to Silverstein, the idea that linguistic meaning is fundamentally based on a denotational structure—in which the most central elements are the mappings between words, concepts, and things— is itself a sort of cultural belief system that has been so wildly successful in the West as to become seemingly universal.(39) His fieldwork suggest that our tendencies in conceptualizing the very question of how music means are also contingent, likely conditioned by this cultural belief system that privileges the denotational capabilities of language.

3.2 Examples of Constative Orientations

[3.2.1] At this point, it will be informative to demonstrate the variety of forms that constative approaches to musical meaning can take. The aim of this sample of constative-oriented inquiries into musical meaning is not to describe constative approaches to meaning as any less virtuous than ones based on performative utterance, but rather to show the underlying commonalities between sometimes widely disparate logics of constativity and to argue on behalf of the greater logical generality of the performative utterance concept. Philosopher Stephen Davies summarizes constative logic and its prevalence within the discourse on musical meaning. I have underlined constructions that point to this bias:

The debate concerning musical meaning has been limited to considering what music conveys, how it does so, and what it means for it to do so. These questions ask what music refers to (or denotes, signifies, stands for), or what it represents (or depicts, describes), or what is expressed through it. Without playing down their differences, one can see that these notions all imply a conception of meaning according to which a meaning-bearer communicates a content that exists independently of itself. (Davies 2011, 71)(40)

[3.2.2] Before the disciplinary turn to musical meaning and criticism of the early 1990s, the groundwork had already been laid for largely constative explorations of musical meaning in a number of earlier works. A signature example of this understanding of meaning appears in Deryck Cooke’s (1959) The Language of Music. Cooke denies strict semantic claims, arguing that no dictionary of musical objects can be formulated. But he also argues that certain gestures are part of a vocabulary of the emotions, demonstrating how musical figurations from a wide historical range appear in similar expressive contexts. He applies a linguistic ideology that locates meaning in transhistorical, stable “essences” of meaningful units. Wilson Coker’s Music and Meaning (1972), known for its bipartite theory of congeneric and extrageneric musical reference, similarly relies on locating meaning in a stable nucleus of sorts, bracketing out context and privileging the semantic: “The sentient attitudes that music expresses are there objectively in tone and rhythm as such” (1972, 148). Jerrold Levinson (1981) speculatively articulates a set of criteria for assessing truth or falsity conditions in music: musical object X expresses thing Y, genuine musical expressions are those that are intended, music expresses that X and Y go together, music expresses that X is followed by Y. All of these early efforts locate the connection between musical and linguistic meaning around forms of mapping. A formidable sub-discipline of music semiotics has subsequently matured.(41)

Example 6. Schubert, “Du bist die Ruh,’” melodic climax and aftermath, mm. 56–65

(click to enlarge)

[3.2.3] A very different manifestation of meaning-as-mapping informs cognitive theory having to do with body-derived image schemas. The cornerstone examples of this theoretical work aim to provide cognitive-psychological accounts of the constative functions of music qua utterance, proposing a mechanism by which musical objects pick out their narrative, imagistic, or verbal correlates. For example, in Candace Brower’s (2000) essay, “A Cognitive Theory of Musical Meaning,” basic schemas such as MUSICAL EVENTS ARE ACTIONS and A MUSICAL WORK IS A JOURNEY prop up connections between particular musical objects and particular embodied experiences, or between particular musical works and particular journey plot-structures. She discusses Schubert’s “Du bist die Ruh’” and demonstrates how the music, via the image schemas associated with it, discloses meanings that poet Friedrich Rückert’s text does not. For instance, she applies the CONTAINER schema to analyze the final two phrases of the song, which feature dramatic melodic ascents that tonicize the subdominant (Example 6). I have underlined constructions buttressed by constative meaning claims:

In the poem, the eyes and heart are represented as metaphorical containers, filled, respectively, with the radiance of the beloved and feelings of joy. What the words do not specifically describe, yet the music conveys, is the expansion of these two metaphorical containers. It is not until we hear the final words of the text, O füll’ es ganz! (O fill it full!) that we fully grasp the meaning of the climactic phrase. Its remarkable expansion conveys the image of these two bodily containers being filled to their fullest extent, an image that becomes increasingly vivid as we approach the end of the phrase (Brower 2000, 369).

Here, the music discloses and depicts various meanings in conjunction with its text via the mediation of a schema involving a CONTAINER being filled to its brim, also invoking ASCENT or VERTICALITY schemas that draw on embodied experiences of rising and falling motions caused by the Earth’s gravity. In this analysis, the song tells about an implied energetics of filling the eyes and heart full and discloses its schematic bases as well. Cognitive image schema theory may offer a psychological mechanism derived from embodied, actional experience by which to account for musical meanings, but the theory operates in service of accounting for semantic mappings between musical objects and particular referents.

[3.2.4] Other constative logics apply to musical meaning in the hands of a variety of authors associated with the “New Musicology” and the turn in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s towards producing scholarship about musical meanings. Susan McClary (1994) writes that Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony reveals things about gender constructions in the early 1800’s, that in it, Schubert expresses personal difference and discloses a model of male sexuality that would later undergo certain marginalizations. Music is figured here according to what linguists would call a “conduit metaphor” (Reddy 1979), where music is involved in the delivery of packets of decodable information. “Although we often speak of Schubert as if he managed to transmit his own subjective feelings directly into his music,” McClary writes, “these ‘feelings’ had to be constructed painstakingly from the stuff of standard tonality” (1994, 222). It is not that McClary or others are uninterested in music’s effects, its consequences, and the actions that it performs. Quite the contrary: McClary’s essay is about how music works in fashioning subjectivities. However, the overall frame of thought seems to be one in which it is necessary first to invoke a theory of how music as utterance represents the world, after which we can move on to thinking about how that musical utterance affects, shapes, and creates action in the world. It is this ordering that I want to call into question. The disclosures of music (and language) are always already preceded by their usability to disclose and their situatedness within lived scenarios that motivate those disclosures.(42)

[3.2.5] Constativity does not need to involve extramusical referentiality at all. Constativity proceeds through the logic of the meaning-as-mapping framework and thus may pertain as well to intramusical meaning. Leonard Meyer’s (1956) account of intramusical meaning depends on a mapping produced by psychological and enculturated processes of expectation. Meyer calls this form of intramusical meaning “embodied meaning,” yet he recruits an essentially referentialist logic in identifying as the crux of intramusical meaning the mapping between particular musical stimuli and their structural consequences or sequellae.

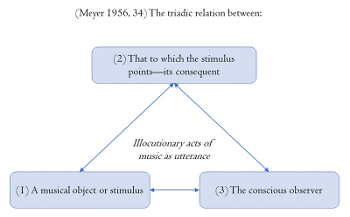

3.3 Towards Performative, Act-Centered Approaches

[3.3.1] However, Meyer’s views can be difficult to characterize since he was aiming to theorize nothing less than musical experience. Meyer’s psychological and behaviorist framework characterizes an acoustical datum in music and the expectations it generates by relating them as stimulus (i.e., musical object) and response (expectational structures). While the act-dimension of musical meaning is not fully demarcated and specified in Meyer’s account, his discussion of musical meaning suggests it. Meyer heavily qualifies his attribution of musical meaning to expectational mappings: “It is pointless to ask what the intrinsic meaning of a single tone or series of tones is. . . . They become meaningful only insofar as they point to, indicate, or imply something beyond themselves. . . . Meaning, then, is not in either the stimulus, or what it points to, or the observer” (1956, 34). That is, a musical entity’s meaning is not an inherent property of the music itself, nor is it reducible to the effects or consequences it generates, nor is it entirely a matter of the subjective proclivities of any unique listener.

Example 7. Meyer’s triadic relation between musical stimulus, musical referent, and listening subject, bound conceptually by the illocutionary acts of music as utterance

(click to enlarge)

[3.3.2] Meyer is articulating something in defining the negative space around it. He eventually concludes that meaning lies in the “triadic relationship” between the musical object, that to which the musical object points (its “consequent”), and an enculturated listening subject.(43) It stands to reason that we could go one step further and understand the foundation that subtends these three nodes as the illocutionary acts of intramusically meaningful tonal structures. These relations are schematized in Example 7. Musically meaningful structures, in Meyer’s account, prompt enculturated expectations; they suggest or imply particular stylistically sanctioned consequents. By this logic, an act of generating expectations is implicated in musical meaningfulness, alongside the musical objects and expectations themselves. This is a subtle but necessary proviso. A listener’s recognition of an expectational structure would be an example of what Austin called uptake: the recognition and attribution of a particular illocutionary act as pertaining to an utterance. Logically prior to this uptake, then, would be that which is taken up: the illocutionary act of suggesting, implying, or prompting an expected structure, an act which, like Austin’s speech-acts, depends on certain felicity conditions being met—here, minimally, the enculturation of the listener into systems of tonal syntax.

[3.3.3] David Lewin’s (1987) transformational theory, particularly the much-discussed “transformational attitude,” also prioritizes a notion of acts. Lewin’s overall vision of a methodological shift towards attending to the act-dimension of his topic mirrors fortuitously Austin’s vision of a methodological shift towards the act-dimension of his. The raison-d’être of transformational theory was to challenge the objectification of musical entities even as basic as a dominant chord, locating the idea of the dominant in its act-character, which stands anterior to its object-character. For Lewin, the dominant is not merely a label for a collection of notes in a syntactically determinate position. It is more than a label for a set of tendencies, and ultimately even more than way of referencing what he calls “kinetic intuitions” (bringing Meyer’s embodied meaning to mind), though he does not deny any of these positions outright. Instead, Lewin specifies the dominant as a transformational operation that drives transformational graph-networks, as an act that directs tonal gravity towards the tonic. Though Lewin’s account does not explicitly address itself to issues of musical meaning, we can attend to a nascent illocutionary force potential ascribed to the dominant as a tonal transformation. It proposes a tonic resolution; it anticipates scale-degrees 1, 3, and 5; it primes a directed motion to the contextual I harmony, it drives the transformational network. These illocutions of the dominant may then be followed by various perlocutionary sequellae: actually achieving the tonic and confirming tonal expectations, forestalling the tonic and prolonging an expectational structure, splitting the difference with a deceptive resolution, and so forth.(44)

[3.3.4] Music analysis is no stranger to the notion of act-potential when dealing with musical objects and their functionality in context, yet there is a mismatch between this implicit recognition of performative act-potential and the broad tendency to make explicit attributions of constative meaning-as-mapping to musical objects when “meaning” comes to be at issue. Accounts of musical meaning that privilege forms of symbolism and referentiality ultimately fail to underwrite musical efficacy and can only gloss any relevant effects that take place as a lacquer on top of that which is disclosed in musical utterance.

[3.3.5] Contrasting the performative, speech-act theoretic attitude with the constative attitude, we might (semi)-formally characterize musical meaning statements like so:

(Constative): the meaning of {MUSICAL OBJECT} is: mapping to {α, β, γ . . .}

(Performative): the meaning of {MUSICAL OBJECT} is: that it does {X, Y, Z, . . .}

The performative, use-theoretic idea of meaning sketched above suggests a grounding for a more general and encompassing account of musical meaning: the constative frame’s “mapping to {α, β, γ . . .}” is a proper subset of the performative frame’s {X, Y, Z, . . .}, a set encompassing the different forms of “doing things” with and in the face of music’s communicativity and meaningfulness. As Wittgenstein argues, it is impossible to disaggregate “the meaning itself” from “doing things” with signs: “How is what [signs] signify supposed to come out other than in the kind of use they have?” ([1953] 1958, §10). Moi, elaborating upon Wittgenstein’s position, writes: “It would be easy to conclude that we are to attend to what we do with words rather than what they mean. But if that were our conclusion, we wouldn’t be getting the point after all, for here the word ‘rather’ gives us the wrong idea” (2017, 28–29). Instead, the perspective elaborated here eliminates the binary opposition between what music “says” and what it “does,” categorizing both as forms of action.

4.1 Theorizing “Performativity” as a Critical Term

[4.1.1] Literary theorists Andrew Parker and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick say it best: the questions raised by “J. L. Austin’s How to Do Things With Words . . . have resonated through the theoretical writings of the past three decades in a carnivalesque echolalia” (Parker and Sedgwick 1995, 1). The decades since the publication of Austin’s treatise have witnessed an unusually wide dissemination of concepts of performativity at large, and a dissemination of the specifically Austinian valences of speech-act theory into not only linguistics and analytic philosophy of language, but also into continental theory and poststructuralist thought via Jacques Derrida ([1972] 1988) and Judith Butler (1997), as well as into anthropology, theater, film, photography, performance studies, theology, and even economic theory. Parker and Sedgwick note that, “given these divergent developments, it makes abundant sense that performativity’s recent history has been marked by cross-purposes. For while philosophy and theater now share ‘performative’ as a common lexical item, the term has hardly come to mean the same thing for each” (1995, 2).

[4.1.2] Fields of musical scholarship in recent decades have made ample use of Austin’s terminology without necessarily activating the specifically Austinian valences and commitments they carry. This is one of the special problems the case of music poses for a speech-act theoretical account of its meanings: how to productively understand interacting but conceptually distinct usages of the term “performative.” Ethnomusicologist Alejandro Madrid sums up the situation in relation to the work of scholars in performance studies:

When most musicians talk about ‘performativity’ they have in mind something quite different from what scholars in performance studies do. . . . The type of performance questions entertained by [traditional music scholarship] remain within the realm of the rendition of a musical text, the ‘how’ to make such texts accessible to listeners, musical performances as texts, or at best, how the notions of performance and composition might collapse in improvisation. In such a context, the term “performativity” refers to the means by which music is created or re-created in performance. (Madrid 2009, [2])

With Madrid, I argue that when we speak of “performativity”, we are speaking, in principle, of two construals of the term, combined in some ratio. One usage, not necessarily operating in view of Austin’s work, links “performativity” to performances, metaphors of the stage, and theatricality. Another usage, which does operate in view of Austin’s work, links “performativity” to the much more everyday idea of performing actions and deeds.

[4.1.3] (P1-PERFORMATIVITY): P1-Performativity refers to performers and their bodies, the liveness of performances, the fact of presence, and the materiality or eventhood of performing. It refers to how performance takes place on stages before audiences, requiring the expenditure of human conduct to happen, and calling attention to the presence of those who perform actions. Under this rubric, we might talk about specific performances and stagings of musical works, the theatricality and artifice involved in doing the performance, or how works and situations of music-making reveal the (perhaps virtuosic) efforts and enactments of presence required to produce them. Centrally at issue for the thinking that implements P1-Performative logic is a dichotomy between materiality, presence, and the body, on the one hand; and categories of the ideational, conceptual, and the mind, on the other hand.

[4.1.4] (P2-PERFORMATIVITY): P2-Performativity instead highlights semiotic efficacy. If P1-Performativity asks what sorts of actions, presences, and conduct lie behind and result in acts of music making, events of speaking, theatrical performances, works of visual art, and so on, then P2-Performativity asks how action and conduct emanate outward from things like pieces of music, painting, sculpture, or staged performances. If linguistic speech-act theory asks how saying something counts as doing something under the rubric of P2-Performativity, then in the general case this rubric seeks to account for how semiotic entities (linguistic or non-linguistic) possess abilities to produce realities and regulate their scenes of address, contexts of witness, situations of hearing, and so forth. P2-Performativity is externally directed: it refers to how a sign or discourse segment manages some aspect of the reality it takes place in, whether fictional or actual. Centrally at issue for the thinking that implements P2-Performative logic is the constative/performative distinction from Austin’s work.

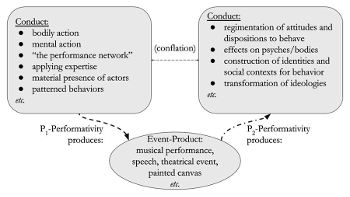

Example 8. Graphic illustration of the distinction between P1-Performativity and P2-Performativity

(click to enlarge)

[4.1.5] As Example 8 illustrates below, P1-Performativity and P2-Performativity designate distinctly different mechanisms for speaking of “performativity” in relation to the musical, verbal, or artistic object of consideration. Example 8 notes a certain conflation that can occur when speaking pre- theoretically about what aspects of music, language, and other forms of utterance are “performative.” This theorization of the term “performativity” ultimately has in mind the goal of better enabling scholars of performing arts and scholars of language to engage in dialogues around a contested term.

[4.1.6] P1-Performativity emphasizes the fundamentally performed nature of music, its liveness and its theatricality. Stephen Rumph, for example, describes Fauré’s allusions to theatrical song styles in his own songwriting as performative, thereby drawing on the “performative” to activate theatrical resonances of stage presence and artifice: “Like many French composers, Fauré drew upon theatrical song in his mélodies, introducing a performative element that encourages distance as well as absorption” (2015, 558). Nicholas Cook describes “the analysis of musical performance as a model for the performativity of analytical writing in general” (1999, 251), suggesting that reading analytical writing can be like witnessing a virtuoso artist commanding a stage. P1-Performativity, in the hands of these authors, is a way of invoking metaphors of stage and theater.

[4.1.7] P1-Performativity is frequently mobilized by the discipline’s recent tide of attention to the carnal, material aspects of music and music making. Roman Ivanovitch deploys the term “performative” in connection with the physical body and liveness of the virtuoso performer: “Showcasing sheer performative prowess, and built from the common fund of stock figuration, sequential patterns, and cadential clichés, it is easy to see how these spots underscore the fragile nature of the pact the concerto makes between ‘virtuosity’ and ‘substance’” (2008, 183). Anna Gawboy introduces the term “performativity” in her remarks on Charles Wheatstone’s concertina to refer to the (imperfect) adaptation of the instrument to the bodies that would wield it: “Wheatstone’s button designs, then, can be appreciated from a purely practical standpoint. However, the slight awkwardness presented by each layout suggests that performativity was not the sole consideration” (2009, 174).

[4.1.8] The logic of P1-Performativity states that human action and performer conduct are inputs from which the event of music making results. It foregrounds a shift from attending to musical works-as-texts to focusing on the efforts that performers expend to realize musical works. This rubric thereby allows us to challenge the hegemony of a work-centric and composer-centric orientation to the study of music. In contradistinction to theories of linguistic performativity and Austinian speech-act theory, however, P1-Performativity maintains close ties with a logic of constativity and disclosure. When describing musical works or events as P1-Performative as above, we are essentially describing how the works disclose the bodies or actions of performers, or how they make reference to the theater and stage. It should be noted that Austin would have roundly dismissed any thinking in terms of the ways in which “performative” utterance resembles theater and stage shows, having once described the speech-acts made in a theatrical work or fictional setting as “etiolated,” “hollow,” and “void” ([1962] 1975, 22).

[4.1.9] A musical P2-Performativity does not attempt to overwrite the claims of P1-Performativity but accounts for entirely different processes. P1-Performativity describes what bodily, actional inputs result in the utterance/text/work as an output, while P2-Performativity accounts for the utterance/text/work as an input to then document what further situations are created as a result. P2-Performativity documents how sign systems accomplish various communicative aims beyond semantic tasks of representing reality or disclosing information: realizing social and material practices, managing experiential and epistemic realities, constructing identities and interpellating subjects, enacting power, and even inflicting injury. However, this is an analytic distinction, not an empirical one: neither P1-Performativity or P2-Performativity occur without the other. Thus, in any given situation, we may be interested in either P1-Performativity or P2-Performativity and their logics, but it would be a category mistake to claim that any music is P1-Performative or P2-Performative to the exclusion of the other. Both concepts of performativity are necessarily active in any situation of music making or music use.

[4.1.10] Another way to describe the intellectual project associated with P2-Performativity would be to say that it frames semiosis and discourse as ritual and ceremony, a recognition that developed in social scientific research prior to its interactions with ordinary language philosophy and Austin-inspired linguistics.(45) Such understandings of “performativity” have influenced anthropologically-inclined performance studies research (Turner 1982; Schechner 1985; Phelan 1993; Jackson 2004.) Any speech-act or performative utterance, be it verbal language, music, or otherwise, is imbued with the power to produce and manage realities by virtue of being spoken, produced, or uttered under the correct contextual conditions. Pierre Bourdieu calls this the “social magic” of performativity: “magical” in the sense that the efficacy of performative semiosis is secured not through expending physical or mechanical efforts, but rather through an incantation of sorts (Bourdieu 1991; Butler 1999). We might describe the P2-Performative efficacy of a musical utterance with the metaphor philosopher Mats Furberg uses to describe linguistic performatives: “Their speaker as it were presses a button in a social machine” (1967, 453).

[4.1.11] A third theoretical vantage point that hybridizes P1-Performativity and P2-Performativity should be clarified. Posthumanist thinkers Donna Haraway (1988) and Karen Barad (2003) describe what they call the “material-semiotic” nature of discursive practices, stipulating that the production of discourses and signs involves material bodies (including, but not limited to, human bodies). Discourses may then go on to act upon and entail consequences for lived and, hence, material practices. This conception of performativity lies at the heart of, for instance, the bodily, material-discursive performativity of identities. Judith Butler’s (2002) work on the bodily performativity of gender, identity, and collective publics highlights the ways in which bodily acts “stage” eminently material performances of identity (P1-Performativity) and highlights how these acts go on to have entailing effects in that they affirm, manage, and constitute the formation of the subject (P2-Performativity). In her afterword to Shoshana Felman’s The Scandal of the Speaking Body, Butler writes that discursive-bodily acts “draw on the body to articulate their claims, to institute the realities of which they speak” (113).

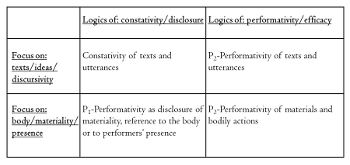

Example 9. The material-semiotic matrix of oppositions structuring performativity concepts

(click to enlarge)