Some (Dis)Assembly Required: Modularity in the Keyboard Improvisation Pedagogy of Jacob Adlung and Johann Vallade

Derek Remeš

KEYWORDS: eighteenth-century music, keyboard improvisation, thoroughbass, central and south Germany, Jacob Adlung, Johann Vallade, modularity, voice-leading pattern, Satzmodell, schema, Anweisung zum Improvisieren, organ tutor, concatenation, historically informed pedagogy, prelude, rule of the octave, sequence, cadence

ABSTRACT: In 2010, researchers at the Bach-Archiv Leipzig rediscovered a manuscript treatise by the central German organist and theorist Jacob Adlung titled “Anweisung zum Fantasieren” (Instruction in Improvisation), dating from c. 1726–27. The treatise, which is investigated here for the first time in print, contains twenty-eight typical baroque voice-leading patterns. Although Adlung demonstrates the variation of these patterns in detail, he remains largely silent regarding their concatenation into larger structures. Two publications by Adlung’s south-German contemporary Johann Vallade represent the ideal complement to Adlung’s treatise, since both authors rely on the principle of modularity, but in a reciprocal manner: Adlung demonstrates and varies individual patterns (a bottom-up approach), while Vallade begins with complete pieces and breaks them into smaller parts (a top-down approach). Thus I suggest that Vallade’s pieces can be productively understood as models for the concatenation of Adlung’s patterns—a sort of missing appendix to Adlung’s instruction. By viewing these authors’ methods as complementary, we gain a more complete picture of how keyboard improvisation and composition were taught in the eighteenth century, which has important implications for historically informed analysis.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.26.1.5

Copyright © 2020 Society for Music Theory

[1] Legos, Ikea furniture, and fast food—these and countless other things consist of modules. A system is considered modular when its components contain elements with relatively strong connections within each component and relatively weak connections between components.(1) While individual modules (a Lego piece, an Ottoman, or a hamburger) can be easily separated and recombined with others in a variety of flexible configurations, they are less easily broken down into their constituent elements. Of course, a hamburger is both a module at the level of the meal (being paired with fries and a drink), while at the same time containing its own modules (bread, meat, cheese, etc.) that could be rearranged in other ways. Here we come upon the issue of infinite regression. Because most structures are multidimensional, modularity is best defined as a degree of interconnectedness of elements at a given hierarchical level. Modules thus arise wherever elements can be related into groups. In fact, it is these groupings that give rise to structural strata in the first place. The principle of modularity has applications within innumerable domains of knowledge, including software design, mathematics, manufacturing, and—as it turns out—baroque keyboard improvisation.(2)

[2] The last two decades have witnessed a surge of scholarly interest in historical music theory and pedagogy, particularly of the eighteenth century. Taken as a whole, this “early theory revival” has helped prompt a reconsideration of the ontological status of common binaries such as craft vs. art, modularity vs. organicism, and small-scale vs. large-scale analysis.(3) These issues need not be summarized further here. It is worth noting, however, that questions surrounding improvisation in particular have provided important stimuli for scholars such as Robert Gjerdingen, Giorgio Sanguinetti, Ludwig Holtmeier, and Felix Diergarten.(4) Through their work and that of many others, it has become generally recognized that composers ranging from the medieval age through the nineteenth century very often developed their abilities through “real-time composition,” and that this skill is founded on the combination and embellishment of pre-defined patterns, which nowadays go by the names of schemata, voice-leading patterns, or Satzmodelle. Of course, this model of creativity has more in common with jazz and the like than with nineteenth-century notions of genius. Yet the precise relationship between improvisational training and composition remains a delicate question that is best answered on a case-by-case basis and will not be taken up directly here. It remains certain, however, that engaging with historical improvisation practices has changed our understanding of early music (broadly defined) and has the potential to keep changing it.

[3] Whereas much research in recent decades has focused on the eighteenth-century Italian partimenti tradition, the present article aims to widen the purview of the early theory revival to include other European traditions.(5) Instead of focusing on the cembalo-oriented partimento tradition, here we will explore a related yet nevertheless distinct south- and central-German thoroughbass tradition oriented around the organ and the Church. The immediate aim of the present article is to contextualize a newly discovered manuscript treatise by Jacob Adlung (1699–1762) by illustrating how his method of teaching keyboard improvisation relies upon the principle of modularity in a manner similar to the little-known pedagogy of another German organist, Johann Vallade (c. 1722–80). I will show how the two authors’ methodologies form a complementary pair, in that Adlung begins by defining individual components (a bottom-up approach), whereas Vallade starts with a complete composition and models its deconstruction (a top-down approach). In short, I suggest that Vallade’s method of concatenation can be productively applied to Adlung’s modules. Or put differently still: Vallade models for us the aspirations of Adlung’s method, since Vallade’s works are intended to be “notated improvisations.” That both musicians use essentially the same components speaks to their stylistic proximity and justifies a comparison. At the same time, the fact that they use the same voice-leading models speaks to the ubiquity of the modular approach at this time. The explication of Adlung’s and Vallade’s methods has immediate ramifications for analysis, improvisation, and pedagogy today and thus will be useful not only for historically inclined theorists, but also for practitioners and teachers interested in eighteenth-century music.(6)

[4] For Adlung, the principle of modularity has direct parallels with the practice of commonplace books, which were used since antiquity to train lawyers, politicians, and clergy in the art of rhetoric.(7) A commonplace book acted as a repository of quotations and topics culled from other sources. The goal was to compile ideas in order to later incorporate them into one’s own speaking or writing. As a professor of languages, Adlung was certainly well acquainted with this literary tradition.(8) For example, in the “Anweisung,” Adlung reveals his practice of copying useful passages into his own Fantasir Buch, or “Improvisation Book,” for future reference (c. 1726–27, 8). And in another instance, Adlung suggests that the pupil carry a book of themes upon which to improvise fugally (1758, 751). Adlung also recommends that the beginning improviser study a collection of works by Johann Heinrich Buttstedt (a student of Pachelbel) entitled Musicalische Clavierkunst und Vorrathskammer (Musical Keyboard-Art and Store-Room, 1713), which is itself envisioned as a commonplace book (c. 1726–27, 83). And elsewhere in the “Anweisung,” Adlung writes that,

When the best and most useful from an author has been excerpted, lay it aside, for it is of no use to you [yet], and take another [work] and do the same, just like the bees, who suck the best nectar from this flower, then from that one, making an agreeable mixture. If this exercise is executed well and often, one can in a short time gather a beautiful stockpile [of ideas].(9)

Given this wealth of evidence, it is readily apparent that Adlung’s “Anweisung” can be understood as a commonplace book. Adlung’s bottom-up approach presents the individual components; Vallade’s top-down approach models their concatenation. Let us begin by examining Adlung’s newly discovered treatise in greater detail.

Defining Modules: Adlung’s “Anweisung zum Fantasieren” (c. 1726–27)

[5] Rediscovered by members of the Bach-Archiv Leipzig in 2010, the “Anweisung zum Fantasieren” (Instruction in Improvising) was first discussed publicly at a conference in Basel, Switzerland, in 2018.(10) Michael Maul has dated the now-lost original manuscript to c. 1726–27 and has identified the Bach-Archiv copy as the work of Johann Christoph Weingärtner (1771–1833).(11) According to his autobiography, Adlung studied moral philosophy with Weingärtner’s grandfather at the University of Erfurt, which suggests a possible link. Regardless, in 1726 the twenty-some-year-old Adlung completed his degree in Jena, where he had studied philosophy, philology, and theology at the university beginning in 1723. During this time he received permission from Johann Nikolaus Bach (J. S. Bach’s cousin and teacher of F. E. Niedt, among others) to practice on the organ at the Michaeliskirche.(12) Whether this indicates a student-teacher relationship remains an open question. Upon the death of J. H. Buttstedt, in 1727, Adlung returned to his native Erfurt to take up the post of organist at the Predigerkirche. There he would remain, later simultaneously serving as professor of languages at the Erfurt Gymnasium, until his death in 1762. Adlung was apparently very active as an instructor, teaching 218 keyboard pupils between 1728 and 1762 by his own account. Prior to the rediscovery of the “Anweisung,” Adlung was known primarily from his two published works: the Anleitung zu der musikalischen Gelahrtheit (1758), which treats a wide variety of topics, including keyboard improvisation; and the Musica mechanica organoedi (1768), an encyclopedic work on organ construction and design, published posthumously (though apparently written as early as 1726). Adlung claims to have written other theoretical works, but these were apparently destroyed in a house fire in 1726, the same fire that destroyed the original manuscript of the “Anweisung.”

[6] Adlung’s treatise comprises ninety-two dense pages of musical examples furnished with sporadic textual commentary; the following provides an overview.(13) The bulk of the “Anweisung” consists of the “Doctrine of the Fundamentals of Improvising,” a list of thirty-four “rules” (Regulae), most of which are brief sequential patterns. Only the first three and the last three rules consist of mostly written explanation without musical examples (or with just very short ones). Briefly paraphrased, the first three rules are:

- The patterns should be varied through changes in register;

- Introduce variety by playing both with and without pedal (one brief example); and

- “Counterpoint” (i.e. invertible counterpoint at the octave) is the “most beautiful stratagem on the keyboard and, in fact, in composition.”(14)

As we will see, invertible counterpoint at the octave is indeed one of the primary strategies Adlung uses to vary the rules. At the end of the “Doctrine,” the last three rules address the questions:

- “How does one start and continue?”;

- “How does one get to another key?” (one brief example); and

- “How does one make a close?” (five brief examples).(15)

Example 1. The first bars of the unornamented “Rules” in Adlung’s “Anweisung zum Fantasieren” (ms. c. 1726–1727)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

The majority of Adlung’s treatise falls between these opening and closing sections. Unlike the six framing rules, the remainder (nos. 4–31) mostly take the form of musical examples with minimal commentary. Highlighting their importance, Adlung begins rule 4 with the statement: “Now we come to the rules, or the matter itself.”(16) The opening bars of the initial, unornamented instances of rules 4–31 are shown in Example 1.

[7] As we can see, all rules are given in C major, and nearly every one is a sequential voice-leading pattern, often containing a suspension chain. The number of voices varies from two to six, with three or four being the norm. Some rules remain purely diatonic, while others use chromaticism or even modulate. Only rules 27–30 are not really sequential, at least in the classic sense. Although more certainly could be said regarding Adlung’s choice and arrangement of patterns, there does not appear to be an overarching organizational system, except that some of the easier and most common patterns are given earlier on. The reader will surely have noticed that many rules use the “circle of fifths” progression. Yet Adlung makes no mention of such interrelationships between patterns, perhaps since his theoretical outlook does not identify chordal roots or track root progressions: the notions that dissonant harmonies have chordal roots and that root progressions are syntactically meaningful did not begin to reach Germany in any significant way until after the mid-eighteenth century.(17) Yet Adlung is by no means atheoretical. For instance, rules 4 and 5 in Example 1 employ parallel thirds and sixths respectively, and Adlung recognizes the invertible relationship between the two, as he does between other patterns. Indeed, such a procedure shows the application of rule 3. More interestingly, Adlung conceives of rule 6 as a combination of the previous two rules, resulting in alternating thirds and sixths. (To my knowledge, this is a novel idea in the treatises of the time.) Let us take a closer look at rule 6 as a microcosm of the entire treatise.

Example 2. Adlung’s twenty-five variations on Rule 6 from the previous example

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[8] Example 2 shows the twenty-five variations Adlung makes on rule 6. The purpose of Example 2 is to provide some idea of the scope of Adlung’s “Anweisung,” since most of the remaining twenty-seven rules are varied in a similarly lengthy fashion. The first variation (no. 2) is designated “Counterpoint,” since it uses invertible counterpoint at the octave—the most basic form of variation for Adlung. Translations of his remaining commentary are given in brackets.(18) From Example 2, we can easily see how unornamented voice-leading patterns provide the basis for innumerable variations, a fact constantly emphasized within the commonplace tradition. When one accounts for the myriad possible orderings of modules, which themselves can be varied in countless ways, the result is truly staggering. Such combinatorial thinking provides a strong counter-argument to the claim that modular methods of musical improvisation and composition are lacking in originality.

[9] Adlung’s variation technique, however, is not the main emphasis of this article.(19) Rather, our focus is the modular principle underlying Adlung’s approach. In this regard I would like to consider a paragraph from the Anleitung in which Adlung describes his “Anweisung.”(20) First, he writes that those who are seeking a copy of the “Anweisung” should cease to do so because the work is useless without his personal instruction. Second, we learn that Adlung decided not to publish the “Anweisung” because the many examples would be too expensive to print, and it was only intended for beginners anyway. Third, he sheepishly admits that the “Anweisung” did not turn out as he had hoped, since he wrote it while still a student, when he “couldn’t tell his right hand from his left.” Lastly, though he planned to compose an updated work on improvisation after the house fire destroyed the original, he had not yet found opportunity to do so (and ultimately would not). Based on these comments, it would seem authors were as apprehensive then as they are now about publishing materials for beginners. Yet the fact that the “Anweisung” was intended for beginners is central to its historical and practical value—it provides a rare window into the expectations for an organist of beginning-to-average skill in German-speaking lands in the early eighteenth century. That Adlung wrote the work while still a student is, in my opinion, no reason to disregard it. Though it is certainly less refined than Adlung’s published works, its emphasis on musical examples, rather than textual explanation, makes it particularly valuable for practitioners today.

[10] After studying the “Anweisung” in its entirety, I consider Adlung’s claim that it was useless without his personal instruction to be a gross exaggeration, at least from the point of view of a modern reader. Besides his embarrassment at the continued propagation of one of his student works, one might speculate that Adlung sought to prevent further spread of the “Anweisung” via manuscript copies because, contrary to his own claim, the work is in fact somewhat self-standing. As a result, Adlung would have lost out on teaching income if students obtained an “unauthorized” copy. On the other hand, perhaps we should not discard his apprehension entirely, for there may be other factors in play. One reason for Adlung’s caution against independent use could be that, although he spends many pages defining voice-leading patterns and their variation, he remains almost totally silent regarding how to combine them into larger structures. This amounts to a glaring gap in his method when judged from the manuscript alone. Naturally, one imagines Adlung would have discussed the combination of modules in private lessons. Thus the suspicion arises: Did Adlung purposely omit any discussion of concatenation in order to ensure that students still had to pay for private lessons? We will probably never know. It is in this regard that I suggest Vallade’s publications are particularly valuable because they provide historically and methodologically fitting models of how to combine Adlung’s rules: Vallade’s works are like missing appendices to the “Anweisung.” Yet before we explore Vallade’s publications, it will be helpful first to define what types of voice-leading patterns, or “modules,” were generally available to the baroque keyboardist.

Categorizing Modules: Scalar, Sequential Leaps, and Cadential Bass Motion

[11] As one would expect in eighteenth-century Germany, thoroughbass provides the conceptual and practical basis of both Adlung’s and Vallade’s approaches to keyboard improvisation.(21) For instance, in both the “Anweisung” and the Anleitung, Adlung lists four skills that every organist must master: (1) thoroughbass, (2) chorales, (3) Italian tablature (i.e., modern staff notation), and (4) improvisation (c. 1726–27, 3–4; 1758, 625). In the Anleitung he writes that, “We begin with thoroughbass as the foundation of the other sections [topics], at least concerning harmony.”(22) Moreover, he advises that it is better to begin instruction in improvisation by orienting around the bass voice, not the melody, for this is simpler for beginners.(23) That Vallade, too, held thoroughbass to be central to his method will soon become apparent.

[12] Because of the centrality of the bass voice in both Adlung’s and Vallade’s methods, I will divide the components of each author’s pedagogical system into three categories depending on the motion of the bass voice: (1) scalar motion, (2) sequential leaping motion, and (3) cadential motion.(24) Adlung implicitly seems to identify the same three categories when, after introducing the type of harmony that each bass degree should take, he writes that,

Thus results already a little fantasy, when one mixes stepwise bass motion ascending and descending with leaps. And each chord will at all times be pleasing to the ear if one makes a proper cadence at the end [emphasis added].(25)

The implication is that Adlung’s approach to improvisation pedagogy resonates with an analytical method oriented around the three categories of scalar, sequential, and cadential bass motion. Let us first examine scalar bass motion.

Example 3. Heinichen’s Schemata Modorum, or bass scale harmonization, from Der General-Bass (1728, 736)

(click to enlarge)

[13] The importance of the rule of the octave (hereinafter, RO) in eighteenth-century music-making has received renewed attention thanks to the historical turn in music theory scholarship in recent decades.(26) As I have shown elsewhere, the concept of bass scale harmonization outlined by Johann David Heinichen (1683–1729) differs in significant ways from most contemporaneous formulations of the RO (Remeš 2019b). These differences have important implications for Adlung’s method of keyboard improvisation. Heinichen’s version, which he calls the Schemata Modorum, is given in Example 3. As he notes, the principal difference between the Schemata and the RO is that the former uses exclusively consonant harmonies (5/3 or 6/3 chords), except for the descending fourth degree, which takes a 6/4/2 chord, since this is a transitus, or passing note in the bass. In contrast, the RO as given by Francesco Gasparini (1661–1727) and Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) includes dissonant chords (6/4/3, 6/4/2, and 6/5/3), which, Heinichen writes, “are only applicable so long as the notes march along in the order in which they are written,” because the dissonances must resolve down by step.(27) Heinichen argues that his use of (almost) exclusively consonant harmonies offers an advantage to the improviser, since one is free to leap from any bass note to any other (even from 6/3 chords). How does this relate to Adlung? In his Anleitung, Adlung provides a list of thoroughbass treatises. Regarding Heinichen’s magnum opus, Der General-Bass in der Composition (1728), he writes that, “This is one of the best books that we have on thoroughbass” (Adlung 1758, 633). Indeed, the improvisation method that Adlung outlines in the Anleitung bears striking similarities to Heinichen’s in that Adlung too defines the typical harmony for each bass degree (the Sitz, or “seat” of each chord, as it was called at this time), then begins with scalar bass motion, followed by leaps and increased dissonance (Adlung 1758, 737–51). Given these similarities and the historical proximity between Adlung and Heinichen, I will orient my analysis of scalar bass segments around Heinichen’s concept of Schemata, not the RO as it is given in French or Italian sources.

Example 4. The three Hauptgänge (sequential bass motions) in Adlung’s Anleitung (1758, Tab. VII, Figs. 47, 49–51)

(click to enlarge)

[14] The second analytical category of bass motion is sequential leaps.(28) It has already been mentioned that the majority of Adlung’s rules in Example 1 use sequential motion. The importance of such voice-leading patterns is highlighted again when Adlung identifies three Hauptgänge (primary passages) in his Anleitung. These are shown in Example 4. Adlung gives these sequences in a few variations; Example 4 is only a selection. He writes, however, that the version given in Example 4a with 6/5 chords is one of the most beautiful of all sequences (Adlung 1758, 742). Example 4b may be used with or without 7 chords (hence their placement in brackets). Adlung advises that the player need not use the complete sequence through the whole octave, but may play only shorter segments, and after descending with the first two sequences, Example 4c can be used to ascend (Adlung 1758, 744). In discussing these sequences, I have opted to avoid the vocabulary of contemporary schemata theory in order to sidestep connotations related to music cognition. In order to avoid an overabundance of analytical labels, I will simply refer to sequences in the order they are found in Examples 1 and 4. Of course, these examples do not claim to be comprehensive, only historically prescient for an introduction to Adlung’s and Vallade’s methods.(29)

Example 5. Walther’s three cadence types in Musicalisches Lexicon (1732, 124–25)

(click to enlarge)

Example 6. Kellner’s illustration of clausulae in Treulicher Unterricht (2nd ed., 1737, 23)

(click to enlarge)

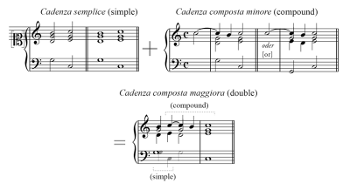

[15] The final analytical category is that of cadences. Strictly speaking, one could collapse cadential motion into the previous two categories if we are only taking the bass voice’s motion into account. But it seems that Adlung and Vallade viewed cadences as independent contrapuntal phenomena, and thus, cadences will receive their own category here. As mentioned already, Adlung’s final rule in the “Anweisung” addresses how to make a close. The two cadences he gives have bass degrees “five to one” or “four to one” with 5/3 chords, and always include a 4-3 suspension (on the penultimate chord in the first case, on the final chord in the second case). But Adlung includes no analytical terms for these cadences,(30) but since he later developed a friendship with Johann Gottfried Walther (1684–1748), from whom he borrowed many theoretical works, I will turn to Walther’s definitions of cadences in his Musicalisches Lexicon (1732, 124–25). These are shown in Example 5 and are equated with the typical eighteenth-century categories of simple, compound, and double (Diergarten 2015, 67; Menke 2011). The semplice contains no dissonance; the composta minore (“compound”) contains a dissonance (5/4, 6/5, or 6/4); and the composta maggiora (“double”) can be understood as the combination of the previous two (though Walther does not comment upon this relationship). In another of Walther’s works, he defines cadences based on the older, seventeenth-century method of identifying which clausula is located in the bass.(31) But since Walther’s examples are numerous, I have opted to save space by merely giving David Kellner’s (1670–1748) concise depiction of clausulae in Example 6. I choose Kellner because his extremely popular treatise, Treulicher Unterricht im General-Bass (1732), is essentially a digest of Heinichen’s Der General-Bass, meaning that Kellner, Heinichen, Adlung, and Walther all occupied the same general historical milieu.(32)

Having outlined the three types of bass motion—scalar, sequential, and cadential—we now turn to Vallade’s models for combining them.

Concatenating Modules: Two Treatises by Johann Vallade

[16] Unlike Adlung, who was active in central Germany (Erfurt and Jena), his younger contemporary Vallade worked in south Germany. There is no indication that their paths ever crossed. Indeed, little is known about Vallade’s life except that he was organist of the small church in Mendorf (located roughly between Nürnberg and Munich) beginning around 1747, where he apparently remained until his death. Yet despite his relative obscurity, Vallade published two noteworthy didactic collections of keyboard works, both published in Augsburg: Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium auf die Orgel (1755) and Der Praeludierende Organist (1757).(33) Let us begin by examining the later work.

[17] The preface to Der Praeludierende Organist consists of a brief fictional dialogue between master and student (à la Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum [1725], among other didactic works). After initial pleasantries, the student admits that, although he has composed reams of preludes, he cannot yet make a cadence in the middle of a piece. Though this may seem to us like an odd problem, the master is nevertheless certain that his instruction is capable of teaching this skill, which is apparently intended for improvising, not written composition, given the title of the work. The remainder of Der Praeludierende Organist consists of twenty-eight preludes in all major and minor keys, including some enharmonic repetitions. Each piece comprises two facing pages, the second of which always contains an “Appendix of Cadences.” Every prelude is subdivided by double bar lines that mark segments ranging from about two to eight measures. At the end of each segment there is a note indicating which of the cadences could be played at this particular moment. In this way, the player gains a high degree of flexibility, which is ideal for the church service, where one must often “fill time” by improvising until the next liturgical action occurs and also be ready to stop in an instant, a fact Adlung comments upon.(34) Should Vallade’s notated prelude be too long, the fictional master in the preface notes that one can shorten a prelude at any double bar line by skipping to the corresponding cadence. Alternatively, should the notated prelude be too short, one can repeat any segment or jump forward or back as needed from the symbol ✽ or ✠ to the corresponding symbol in another place. Thus, each piece is construed as a set of interlocking modules that can be arranged in a variety of flexible configurations.

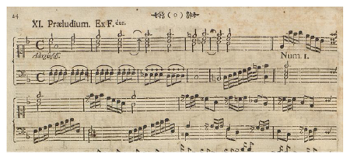

Example 7. Vallade, “Praeludium F Dur” from Der praeludierende Organist (1757, 24–25)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 8. Vallade, “Praeludium F Dur” from Der Praeludierende Organist (1757, 24–25) with analytical annotations

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[18] Example 7 gives Vallade’s complete Prelude in F major in facsimile. As mentioned already, cadences in the original publication are listed on the facing page, which is practical when one can see both folios. Example 8 reproduces Example 7 in modern notation with the cadences relocated directly after each subsection in order to facilitate easier comparison. Vallade’s Prelude consists of a slow introduction (marked Adagiosiss. because, as the master notes, beginners always play too fast), a conclusion, and ten intervening sections. Section two has the ✠ symbol, meaning one may jump forward to section ten at this point (or vice versa). Section seven provides a similar “portal” to the final chord (or vice versa). In both cases, a linkage is possible because the harmonies are the same. In Vallade’s model, this is apparently all that is required in order to create a link between two modules—a far remove from any notion of Romantic-era organicism!

[19] Below each staff throughout Example 8 I have added a modular analysis based on the three categories outlined above—scalar (referring to Heinichen’s Schemata), sequential, or cadential. For instance, “Adlung 15; b” refers to Adlungs rule 15 from Example 1 and bass line (b) from Example 4. Surprisingly, nearly every beat of Vallade’s prelude can be easily reduced to one of these categories. Moreover, it would seem that Adlung’s three Hauptgänge represent Vallade’s preferred sequences—indeed, one of them appears in each of the ten sections (the sequence from Example 4a appears particularly often). Adlung advises in his Anleitung that sequences are well-suited to modulation, a fact Vallade exploits.(35) Recall that Adlung warned earlier that his “Anweisung” would be of no use without his assistance. In this regard, Vallade’s prelude seems to provide an excellent model of concatenation, particularly regarding Adlung’s recommendation to “not be a slave to the sequences,” but to “link them together.”(36) The double cadence (Walther’s composta maggiore) is clearly Vallade’s favorite in the cadential category, concluding all of the cadential sections except section five, which uses a compound cadence (Walther’s composta minore). The Prelude in F major is completely typical of the pieces in Der praeludierende Organist, and thus provides both a sense of the complete publication and a rough estimation that one could expect to find similarly frequent occurrences of Adlung’s Hauptgänge and the double cadence in Vallade’s other preludes—and indeed this turns out to be the case.

[20] Vallade’s other didactic publication, Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium, employs a different pedagogical method than the one just outlined, yet the principle of modularity still underlies its approach. The “three-part exercise” of the title refers to the procedure by which Vallade first gives a complete prelude, then extracts its foundational figured bass line, and finally gives a short fugue in the same key. We will focus on the first two steps, excluding the fugues, which do not appear to share obvious thematic relationships with the preludes.(37) According to the work’s lengthy title, the purpose of the excerpted thoroughbass line is to provide rudimentary instruction to rural teachers and novices in the “highly important skill” of improvising a prelude.(38) The idea is that, after learning to play Vallade’s prelude (step one), the student would then invent another realization to the figured bass line given in step two.

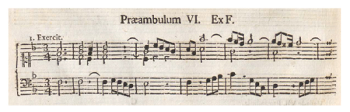

Example 9. Vallade, “Preludium IV. Ex. F [Dur]” from Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium auf die Orgel (1755, 10–11)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

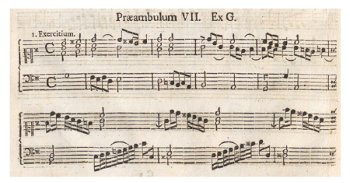

Example 10. Vallade, “Preludium VII. Ex. G [Dur]” from Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium auf die Orgel (1755, 12–13)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[21] Examples 9 and 10 show two representative pieces from the Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium. My analyses appear in Examples 11 and 12, respectively. At the top is Vallade’s original prelude; in the middle is his thoroughbass reduction; and on the bottom is my reduction to a (mostly) consonant, diatonic framework. This last step simply makes the analysis more transparent. As in Example 8, I have analyzed the modules with annotations below the staff, and as before, both pieces can be conveniently understood almost entirely within the three categories outlined above. After having learned Vallade’s prelude, the student would then attempt to improvise in a similar style over the extracted thoroughbass line. Perhaps even more usefully, Vallade’s method provides a model for how the student could interact with other works: first learn the piece, then extract a figured bass line from it, and finally improvise upon the new bass line. In this way, the figured-bass reduction itself could function as an entry in the pupil’s commonplace book. At the same time, the modular analysis of the bass provides another source of commonplaces at a smaller structural level.

Example 11. Vallade, “Preludium IV. Ex. F [Dur]” from Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium auf die Orgel (1755, 10–11) (click to enlarge and see the rest) | Example 12. Vallade, “Preludium VII. Ex. G [Dur]” from Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium auf die Orgel (1755, 12–13) (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

[22] In this article I have argued that the top-down instruction of Vallade’s two publications can be understood as complimentary to the bottom-up method found in Adlung’s “Anweisung.” That many of Adlung’s voice-leading patterns appear in Vallade’s works is in itself not that surprising, given that many such patterns can be found in various thoroughbass traditions throughout Europe at this time. Yet the extent to which Adlung’s and Vallade’s methods rely on the principle of modularity, together with the fact that Vallade’s preludes consist almost exclusively of scalar, sequential, and cadential bass patterns, is indeed notable. Both of their treatises are valuable in that they provide a rare window into eighteenth-century German improvisational instruction at a quite basic level. This is particularly useful in today’s research because it gives a better sense of the average musician’s ability level in this period. This, in turn, can help set more realistic standards for today’s keyboardists, who should, I believe, not feel discouraged if their improvisations do not reach the level of the most complex works of, say, J. S. Bach. The modular approach outlined here also provides a tangible inroad for historically oriented improvisation instruction today. In this regard we should keep in mind that, even after recommending that the beginning improviser consult a publication by Johann Anton Kobrich (1714–1791) intended to teach the skill of preluding, Adlung still admits that, “It is doubtful whether one can be successful [in learning to improvise] without rules, merely through [studying] keyboard works.”(39) It seems that, in Adlung’s view, imitation alone is not enough. Instead, the improvising mind requires concrete directives, which, in Adlung’s method, apparently take the form of brief, brick-like segments that can be concatenated in a variety of flexible configurations. Indeed, at least once Adlung likens the improviser to a builder (1758, 733). Even the rather mundane voice-leading modules like those outlined in Adlung’s “Anweisung” can—whether borrowed or original—provide a reliable scaffolding for an infinite variety of sound edifices.

Derek Remeš

Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Schönbühlstrasse 26

6020 Emmenbrücke

Switzerland

derek.remes@hslu.ch

Works Cited

Adlung, Jacob. c. 1726–27. “Anweisung zum Fantasieren.” ms. Bach-Archiv Leipzig. L-LEb, Rara II-658-C. A translation and modern edition edited by Derek Remeš is in preparation and is expected to be published by the end of 2020.

—————. 1758. Anleitung zu der musikalischen Gelahrtheit.

—————. 1768. Musica mechanica organoedi, 2 vols. Edited by Johann Friedrich Agricola.

Bach, C. P. E. 1753–62. Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen. 2 parts.

Baldwin, Carliss Y., and Kim B. Clark. 2000. Design Rules: Volume 1. The Power of Modularity. MIT Press.

Bassani, Florian. 2018. “Partimentofugen in deutschen Quellen.” In Compendium Improvisation: Fantasieren nach historischen Quellen des 17. und 18. Jahrhunders, ed. Markus Schwenkreis, 199–210. Schwabe.

Buttstedt, Johann Heinrich. 1713. Musicalische Clavierkunst und Vorrathskammer. 2nd. ed. 1716. Preserved in D-DS Mus. ms. 1410.

Byros, Vasili. 2015. “Prelude on a Partimento: Invention in the Compositional Pedagogy of the German States in the Time of J. S. Bach.” Music Theory Online 21 (3).

Callahan, Michael. 2010. “Improvising Motives: Applications of Michael Wiedeburg’s Pedagogy of Modular Diminution.” Intégral 24: 29–56.

Christensen, Thomas. 1992. “The ‘Règle de l’Octave’ in Thorough-Bass Theory and Practice.” Acta Musicologica 64 (2): 91–117.

—————. 1996. “Johann Nikolaus Bach als Musiktheoretiker.” Bach-Jahrbuch 82: 93–100.

—————. 2004. “Fundamentum, fundamental, basse fondamentale.” In Handwörterbuch der musikalischen Terminologie. Steiner.

—————. 2008. “Fundamentum Partiturae: Thorough Bass and Foundations of Eighteenth-Century Composition Pedagogy.” In The Century of Bach and Mozart: Perspectives on Historiography, Composition, Theory, and Performance in Honor of Christoph Wolff, ed. Thomas Forest Kelly and Sean Gallagher, 17–40. Harvard University Press.

Diergarten, Felix. 2015. “Beyond ‘Harmony’: The Cadence in the Partitura Tradition.” In What Is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire, ed. Markus Neuwirth and Pieter Bergé, 59–84. Leuven University Press.

Frescobaldi, Girolamo. 1616. Primo Libro di Toccate.

—————. 1624. Il primo Libro di Capricci fatti sopra diversi soggetti e arie.

—————. 1635. Fiori Musicali, op. 12.

Froebe, Folker. 2008. “‘Ein einfacher und geordneter Fortgang der Töne, dem verschiedene Fugen, Themen und Passagen zu entlocken sind’. Der Begriff der ‘phantasia simplex’ bei Mauritius Vogt und seine Bedeutung für die Fugentechnik um 1700.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 5 (2–3): 195–247.

Fux, Johann Joseph. 1725. Gradus ad Parnassum. Ghelen. Translated into German and edited by Lorenz Mizler as Gradus ad Parnassum oder Anführung zur Regelmäßigen Musikalischen Composition. Author, 1742.

Gingras, Bruno. 2008. “Partimento Fugue in Eighteenth-Century Germany: A Bridge Between Thoroughbass Lessons and Fugal Composition.” Eighteenth-Century Music 51 (1): 51–74.

Gronau, Daniel Magnus. 2016. Ms. Akc. 4125 at the Danzig Library at the Polish Academy of Sciences. Modern edition: Daniel Magnus Gronau (1699–1747): 517 Fugues. 2 vols. Edited by Adrzej Mikolaj Szadejko. Akademia Muzyczna im. Stanisława Moniuszki w Gdańsku.

Guido, Massimiliano, ed. 2017. Studies in Historical Improvisation: From Cantare super Librum to Partimenti. Routledge.

Heinichen, Johann David. 1728. Der General-Bass in der Composition.

Holtmeier, Ludwig. 2007. “Heinichen, Rameau, and the Italian Thoroughbass Tradition: Concepts of Tonality and Chord in the Rule of the Octave.” Journal of Music Theory 51 (1) (Spring): 5–49.

—————. 2017. Rameaus Langer Schatten: Studien zur deutschen Musiktheorie des 18. Jahrhunderts. Olms.

Jans, Markus. 2007. “Towards a History of the Origin and Development of the Rule of the Octave.” In Towards Tonality: Aspects of Baroque Music Theory, 119–44. Leuven University Press.

Johnson, Cleveland. 1990. “A Keyboard Diminution Manual in Bártfa Manuscript 27: Keyboard Figuration in the Time of Scheidt.” In Church, Stage, and Studio: Music and its Contexts in Seventeenth-Century Germany, ed. Paul Walker, 279–348. UMI Research Press.

Kellner, David. 1732. Treulicher Unterricht im General-Bass. 2nd ed., Herold, 1737. Translated in vol. 1 of Remeš 2019a.

Kobrich, Johann Anton. n.d. Leicht zu erlernender, vielfachen Nuzen bringender Kirchen Ton; das ist XXXVI kurze Praeludia von welchen [

Lester, Joel. 2007. “Thoroughbass as a Path to Composition in the Early Eighteenth Century.” In Towards Tonality: Aspects of Baroque Music Theory, ed. Dirk Moelants, 145–68. Leuven University Press.

Menke, Johannes. 2010. “The Skill of Musick. Handleitungen zum Komponieren in der historischen Satzlehre an der Schola Cantorum Basiliensis.” Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis 34: 149–67.

—————. 2011. “Die Familie der cadenza doppia.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 8 (3): 398–401.

—————. 2019. “Vision, Abenteuer und Auftrag: Wulf Arlts historische Satzlehre.” In Beredte Musik: Konversationen zum 80. Geburtstag von Wulf Arlt, ed. Martin Kirnbauer, 277–81. Schwabe Verlag.

Muffat, Georg. 1695–98. Florilegium Primum and Florilegium Secundum.

Muffat, Georg. 1699. Regulae concentuum partiturae. Ms. Edited with an introduction by Hellmut Federhofer and translated as An Essay on Thoroughbass. American Institut of Musicology, 1961.

Niedt, Friedrich Erhard. 1700–1717. Musicalische Handleitung. 3 vols. 1700, 1706, and 1717. Vol. 1 reissued in 1710. Vol. 2 reissued in 1721 and ed. Johann Mattheson. Vol. 3 published posthumously in 1717 and ed. Mattheson. Translated by Pamela Poulin and Irmgard Taylor as F. E. Niedt, The Musical Guide Parts I–III (1700–1721). Oxford University Press, 1989.

Poglietti, Alessandro. 1676. Compendium: oder kurzer Begriff und Einführung zur Musica, sonderlich einem Organisten dienlich. Facsimile: Compendium, Ms. 1676. Cornetto, 2008.

Poulin, Pamela, trans. 1994. J. S. Bach’s Precepts and Principles for Playing the Thorough-Bass or Accompanying in Four Parts, Leipzig, 1738. Clarendon Press.

Prendl, Christoph. 2017. Die Musiklehre Alessandro Pogliettis. Florian Noetzel.

Remeš, Derek. 2018. “Anweisung zum Fantasieren: Symposium zur Praxis und Theorie der Improvisation im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, Basel, 19–21 March 2018.” Conference Report. Eighteenth-Century Music 16 (1): 89–92. doi:10.1017/S1478570618000477.

—————. 2019a. Realizing Thoroughbass Chorales in the Circle of J. S. Bach. Vol. 1: Sources from J. S. Bach, C. P. E. Bach, and D. Kellner, with a Primer by D. Remeš. Vol. 2: The Sibley Chorale Book. Wayne Leupold Editions.

—————. 2019b. “Four Steps Towards Parnassus: Johann David Heinichen’s Method of Keyboard Improvisation as a Model of Baroque Compositional Pedagogy.” Eighteenth-Century Music 16 (2): 133–54.

—————. 2019c. “New Sources and Old Methods: Reconstructing the Theoretical Paratext of J. S. Bach’s Pedagogy.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 16 (2): 51–94.

—————. 2019d. “Compendium of Voice-Leading Patterns from the 17th and 18th Centuries to Play, Sing, and Transpose at the Keyboard.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy. Resources Section. Future updates available at http://derekremes.com/wp-content/uploads/compendium_english.pdf.

—————. 2020. “Exploring the Contrapuntal Potential of Keyboard Thoroughbass in Today's Music Theory Classroom.” In Das Universalinstrument: “Angewandtes Klavierspiel” aus historischer und zeitgenössischer Perspektive / The Universal Instrument: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on “Applied Piano,” ed. Philipp Teriete and Derek Remeš, 179–215. Schriften der Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, Band 9. Olms.

Sanguinetti, Giorgio. 2010. “Partimento-fugue: The Neapolitan Angle.” In Partimento and Continuo Playing in Theory and Practice, ed. Dirk Moelants, 71–118. Leuven University Press.

—————. 2012. The Art of Partimento: History, Theory, and Practice. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2013. “Diminution and Harmonic Counterpoint in Late-Eighteenth-Century Naples: Vincent Lavigna’s Studies with Fedele Fenaroli.” Journal of Schenkerian Studies 7: 1–31.

Schubert, Peter. 2010. “Musical Commonplaces in the Renaissance.” In Music Education in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, ed. Russel E Murray, Jr., Susan Forscher Weiss, and Cynthia J. Cyrus, 161–92. Indiana University Press.

Schwenkreis, Markus, ed. 2018. Compendium Improvisation: Fantasieren nach historischen Quellen des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts. Schwabe.

Sorge, Georg Andreas. 1745–47. Vorgemach der musicalischen Composition, 3 vols.

Telemann, Georg Philipp. 1730. Fast allgemeines Evangelisch-Musicalisches Lieder-Buch.

Vallade, Johann Baptist Anton. 1755. Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium auf die Orgel, oder VII. PRAEAMBULA und Fugen, nach dem heutigen Goût. Wobey nach jedem Praeambulo der General-Bass heraus gesezet zu sehen ist, um die höchst-nöthige Praeludir-Kunst mit puren Ziffern zu erlernen. Denen Land-Schulmeistern, und überhaupt allen jungen Organisten zur Ubung aufgesezet.

—————. 1757. Der Præludierende Organist, oder: Neue, und nach dem heutigen Gusto eingerichtete Præludien und Cadenzen in doppelten A. B. C. D. E. F. G. beyde Tone mit der Terz major und minor, so vortheilhaft und leicht eingerichtet, daß man ohne weitere Anweisung eines Lehrmeisters nicht allein die höchst-nöthige PRAELUDIER-Kunst vollkommen erlernen; und nach Nothdurft und Belieben durch angewiesene Zeichen und Nimern, ein Præludium verlängern, sondern auch mitten im Præludieren, alle 4. 5. oder 6. Tact, selbst eine Cadenz, sowohl Major als Minor formiren und finden kann.

Walther, Johann Gottfried. 1708. Praecepta der musicalischen Composition, ms. D-WRtl. Edited by Peter Benary. Breitkopf & Härtel, 1955.

—————. 1732. Musicalisches Lexicon.

Wolff, Christoph, ed. 1998. The New Bach Reader. W. W. Norton & Company.

Wollny, Peter. 2008. “On Johann Sebastian Bach’s Creative Process: Observations from His Drafts and Sketches.” In The Century of Bach and Mozart: Perspectives on Historiography, Composition, Theory, and Performance in Honor of Christoph Wolff, ed. Thomas Forest Kelly and Sean Gallagher, 217–38. Harvard University Press.

Footnotes

1. This definition is based in part on Baldwin and Clark (2000, 63).

Return to text

2. Wollny (2008, 226–27) argues that modularity is central to J. S. Bach’s compositional process. Remeš 2019c also contends that chorale melodies and cadences in J. S. Bach’s circle were understood in terms of modules.

Return to text

3. I proposed the term “early theory revival” in Remeš 2018 to describe the recent historicizing turn in Anglo-American music theory as a continuation of trends that began in Basel in the 1980’s with the emergence of historische Satzlehre in German-speaking circles. See also Menke 2019.

Return to text

4. The essay collections edited by Massimiliano Guido (2017) and Markus Schwenkreis (2018) also deserve mention.

Return to text

5. This article is by no means the first to explore the German thoroughbass tradition. For a recent publication, see Byros 2015.

Return to text

6. See Remeš 2020 for a pedagogical method based on these principles.

Return to text

7. Regarding commonplace books, see Schubert 2010. Muffat (1695) and Frescobaldi (1616, 1624, 1635) are outgrowths of the commonplace tradition.

Return to text

8. Adlung writes in the “Anweisung” that the pupil must not be thievish (diebisch) and copy works in secret, lest he be found out and provoke the master’s annoyance (c. 1726–27, 8). The high value placed on access to musical manuscripts for copying is evidenced in an anecdote related in J. S. Bach’s obituary: while in Ohrdruf, Bach was caught secretly copying manuscripts from his brother’s collection (apparently by moonlight), something his brother had explicitly prohibited him from doing (Wolff 1998, 299).

Return to text

9. “Wenn nun aus einem Autore das beste und nu?tzlichste excerpirt ist, so lege es bey Seite, denn nun ist es dir nichts nutze, und nimm ein anders und verfahre auch gleicherweise, nicht anders als die Bienen, welche bald aus diesen, bald aus jenen Blumen den besten Saft saugen, und sodann eine angenehme Vermische[?] anstellen. Wenn nun diese Arbeit so fein oft getrieben wird, so kann man sich in kurzer [Zeit] einen schönen Vorrath sammeln” (Adlung c. 1726–27, 6).

Return to text

10. Remeš 2018 gives a conference report.

Return to text

11. Michael Maul, “Jacob Adlungs ‘Anweisung zum Fantasieren’ und ihr Kontext.” Unpublished conference paper presented at the conference, “Anweisung zum Fantasieren: Symposium zur Praxis und Theorie der Improvisation im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, Schola Cantorum Basiliensis” in Basel, Switzerland, 19–21 March 2018. Paper obtained via email communication with the author on March 30, 2018.

Return to text

12. Adlung (1768, 2: vi). Regarding J. N. Bach’s role as theorist and teacher, see Christensen 1996.

Return to text

13. I plan to publish a modern edition and English translation of Adlung’s “Anweisung” in 2020.

Return to text

14. “Reg. I. Weil doch alles darauf ankommt, daß es nicht immer einerley klingen soll, so befleißige man sich Abwechselungen zu machen, die in die Ohren fallen als was neues, wenn es gleich fast immer einerley ist; und geschieht nach der ersten Regel, wenn man die Hände nicht immer an einem Orte hat, sondern bald oben, bald in der tiefe spielet, und man die Hände bald von einander hält, bald zusammenkommen läßt, da werden die Fleckchen [Sätze] die man spielt als etwas anders klingen und in der That ist es wohl immer einerley, nur daß man es in unterschiedenen Octaven gespielet hat, die Exempel werden unten vorkommen. Regl. II. Man gewöhne sich das Pedal bey Zeite an, denn dadurch kann man allerley Veränderungen machen, nehmlich, wenn man erst ein Fleckchen mit dem Pedal gemacht hat, so spiele man hernach eben dieses ohne Pedal, hernach wenn man will kann man das Pedal wieder anschlagen gg. [?] so wird es als etwas neues hervor kommen. Reg. III. Wenn man die Stimmen versetzen lernt, daß die obere Stimme bald hinunter, bald in die Mitte gesetzt wird, die unterste Stimme bald in die mitte, bald oben, die mittlere Stimme bald oben, bald unten. Man nennet dieses sonst den Contrapunct, und ist der schönste Kunstgriff auf dem Clavier, und überhaupt in der Composition” (Adlung c. 1726–27, 15-16). “Rule I: Since everything depends upon it not always sounding the same, one makes an effort to introduce variations that seem to be different to the ear, even when they are almost the same. This can be done by means of the first rule, which says to vary the position of the hands, first playing in the high register, then in the lower, first with the hands far from one another, then near. In this way, the fragments [literally: little flecks] that one plays sound different even though it is actually always the same, only that one plays in different octaves. Examples of this are found below [not shown here]. Rule II: One gradually gains proficiency with the pedal, for through the pedal one can make all sorts of variations. For example, if one has first played a fragment with the pedal, then one plays it afterwards without the pedal, and later, if desired, one can play the pedal again. In this way, the pedal will seem to be something new. Rule III. One learns to invert the voices so that the upper voice is set in the bottom, then the middle; the lowest voice goes to the middle, then the top; the middle voice goes to the top, then the bottom. This is called counterpoint and it is the most beautiful device on the keyboard and in all composition.” All translations are my own unless stated otherwise.

Return to text

15. “Wenn man nun spielen will, wie fängt man an, und wie fährt man fort? [

Return to text

16. “Reg. IV. Nun kommen wir auf die Regel oder Sache selbst” (Adlung c. 1726–27, 16).

Return to text

17. Remeš 2019c develops this argument in greater detail.

Return to text

18. Between the second and third variation Adlung inserts this text, (which did not fit in the example): “Hier merke Anfangs 1.) daß nothwendig 3erley variationes sich hier machen lassen weil es auch 2stimmig gespielt wird, und zwar α) oben, β) unten, γ) oben und unten zugleich, 2.) daß man das Pedal hier nicht sowohl in einem Ton mit brummen lassen könne, sondern es muß entweder gar stille schweigen, oder mit der linken Hand allezeit fortgehen. 3.) daß die vorigen 2 Regeln allezeit aufwärts und unterwärts gegolten haben, diese aber geht nur unterwärts an, wollte man es aufwärts appliciren so würde es nicht wohl in die Ohren und in die Faust fallen; die Veränderungen des obigen Exempels sollen folgende seyn” (Adlung c. 1726–27, 23). “Note here at the beginning (1) that there are necessarily three kinds of variations to be made here because there are two voices, i.e., [a variation] above, below, and above and below simultaneously; (2) that the pedal cannot remain held on a single tone, but must either remain silent or double the left hand; (3) that the two previous rules have always applied to both ascending and descending motion, but this [rule six] only descends; if one wanted to apply it in ascending it would not be fitting to the ear or the hand. The variations on the above example are as follows.”

Return to text

19. The classic work on early eighteenth-century diminution is the second volume of Niedt (1700–1717). See also Johnson 1990, Callahan 2010, and Sanguinetti 2013

Return to text

20. “Einige meiner heisigen Bekannten werden dabey gedenken: wo bleibt denn des Verfassers Anweisung zum Fantasiren, so sich in den Händen einiger Schüler befindet, und geschrieben einen ziemlichen Quartband ausmacht? Hierauf dient folgendes: weil dieses werk nur geschrieben, so würde dessen Anführung vergeblich seyn, indem den Lesern, so nicht bey mir in der Lehre stehen, solches nichts helfen könnte. Zum zweyten würde ich dem Verleger dieses Werkes nicht gefällig seyn, wenn ich solche Ausführung zum allgemeinen Gebrauch allhier einrücken wollte, als wobey eine grosse Menge Kupfertafeln nöthig wär, welche Kostbarkeit den allgemeinen Nuzen meines Buchs mehr verhindern als befördern würde. Drittens ist auch solche Ausführung gar keine solche, wie ich sie wünsche. Ich habe solche noch entworfen einem Scholaren zum Dienste, welcher nechst GOtt die vornehmste Stüze meiner zeitlichen Glückseligkeit zu nennen, und zwar zu einer Zeit, da ich als ein Schüler des hiesigen Gymnasii selbst das Rechte von dem Linken nicht wuste zu unterscheiden, auch die Absicht nicht hatte, daß es in fremde Hände kommen sollte. Wie denn, nachdem mein Exemplar verbrannt, ich solches vor mich nicht einmal wieder abschreiben lassen, weil ich stets gedacht, es sollten sich etwa die Zeiten so fügen, daß ich eine andere Art der Ausführung könnte entwerfen; worauf ich aber bis iezo vergeblich hoffe. Und also muß ich zwar geschehen lassen, daß jene Vorschläge aus einer Hand in die andere kommen; doch sehe ich es ungern. Zumal da die Abschreiber stets mehr Fehler einschleichen lassen, daß endlich dieses verstümmelte Werk mir (zumal bey Unverständigen) mehr Schande als Ruhm zuwege bringen dörfte (Adlung 1758, 734–35, note e). No translation is given because this quotation is discussed in detail in the body of this article.

Return to text

21. For instance, both Telemann and Heinichen associate thoroughbass with improvisation and composition (Telemann 1730, 185; Heinichen 1728, 913). According to C. P. E. Bach, J. S. Bach also started his students out with thoroughbass (Wolff 1998, 399). Christensen (2004, 13–14) compiles historical accounts of thoroughbass as a foundation of composition. See also Lester 2007.

Return to text

22. “Wir machen also hier den Anfang mit dem Generalbass, als dem Grunde zu den übrigen Theilen, wenigstens was die Harmonie anlangt [

Return to text

23. “Hier wird mancher tadeln, daß meine Anweisung sich erst um den Baß bekümmere, da die Melodie den Vorzug haben solle; aber hierauf dienet, daß diese Art, nach der Melodie die Bässe zu machen, schon mehr voraus sezt, und vor die Anfänger zu schwer scheint, weil man solche nicht so wohl in Regeln vorstellen kann. Mit der Zeit bricht man aber auch diese Kosen” (Adlung 1758, 751). “Here some are certain to complain that my instruction first addresses the bass, since the melody should be privileged. But to this one says that this method of making bass lines after the melody has more prerequisites, and seems too difficult for beginners, since one has has difficulty visualizing this [process] in terms of rules. With time, however, one overcomes these crutches.”

Return to text

24. The choice of categories was influenced in part by the first five chapters of Schwenkreis 2018, 22–132), as well as the teachings of Mauritius Vogt (1669–1730) as discussed in Froebe 2008. Remeš (2019d) also organizes its voice-leading patterns along this three-part division. Andreas Sorge also orients his sixteen rules for beginning improvisers in part around the motion of the bass voice (1745, 3:422–25). I single out Sorge because Adlung 1758 (734) recommends Sorge’ss rules for beginners. Moreover, a document with ties to J. S. Bach’s teaching in Leipzig (the “Precepts and Principles”) also outlines sequential motion and cadences, though admittedly makes no mention of improvisation (Poulin 1994, 46–56). For more on the modular nature of the cadences in the “Precepts and Principles,” see Remeš 2019c.

Return to text

25. “Hieraus entsteht schon eine kleine Fantasie, wenn man den Baß bald Stufenweise steigen und fallen läßt, bald macht man Sprünge, und die Griffe werden jederzeit wohl zu hören seyn, wenn man einen förmlichen Schluß am Ende hinzu thut” (Adlung 1758, 740).

Return to text

26. See Christensen 1992, Jans 2007, Holtmeier 2007 and 2017, and Sanguinetti 2012 (113–25).

Return to text

27. “Da hingegen die Schemata beyder Autorum viel speciale Signaturen angeben, die nicht länger gelten, als die Noten sein in der Ordnung marchiren, wie sie hingeschrieben worden” (Heinichen 1728, 765).

Return to text

28. C. P. E. Bach also discusses sequential bass motion in connection with keyboard improvisation in his Versuch (1753, 2:323).

Return to text

29. Another useful historical source of thoroughbass “modules” for improvisation is Poglietti 1676, discussed in Prendl 2017.

Return to text

30. The title page of Vallade (1757) refers to major and minor cadences. Vallade never defines these terms in any more detail, probably because he assumed they were common knowledge. We find definitions in Muffat 1699: major has degrees “five to one” in the bass, minor has degrees “four to one” in the bass. That both Adlung and Vallade discuss the same types of cadences represents yet another link between their treatises.

Return to text

31. Walther 1708 (295–98). For more on Walther’s method of cadential classification, see Remeš 2019c.

Return to text

32. See the introduction to Remeš 2019a for more background on Kellner’s 1732 treatise; vol. 1 of this publication gives the first English translation of Treulicher Unterricht.

Return to text

33. Regarding the importance of Augsburg as a south-German publishing hub, see Christensen 2008 and Diergarten 2015.

Return to text

34. “Ein Spieler, zumal vor einer Musik, hat keine abgemessene Zeit. Wenn er etwas langes angefangen, so winkt der Musikdirector, daß es Zeit sey anfzuhören, welches bey uns augenblicklich geschehen muß, ob ich wohl weis, daß an manchen Orten man wartet, bis dem Organisten gefällt zu schliessen” (Adlung 1758, 731). “A player, especially of a written work, has no predetermined time-frame. If he tarries a little longer, then the music director signals that it is time to stop, and this must occur in an instant here [in this region], even though I am well aware that in some places one waits until the organist decides to come to a close.” Some works by Girolamo Frescobaldi are designed to accommodate such flexibility, such that the organist could stop at any number of predefined sectional boundaries. See the prefaces to Primo Libro di Toccate (1616) and Il primo Libro di Capricci (1624).

Return to text

35. “Diese Gänge führen auch leicht in andere Tonarten” (Adlung 1758, 744). “These passages lead easily to other keys.”

Return to text

36. “Bey solchen bisherigen Gängen ist der Scholar zu warnen, daß er kein Sclav davon werde, sondern sich nur dann und wann deren bediene, auch solche ordentlich zusammen hänge” (Adlung 1758, 749). “With the passages discussed up until now, the pupil is to be warned that he should not be a slave to them, but should only make use of them here and there, also linking them together in an orderly manner.”

Return to text

37. There is growing scholarly interest in the ways in which imitative genres can also be expressed in thoroughbass notation. See Bassani 2018 (199–210), Sanguinetti 2010, 71–118), Gingras 2008, and Gronau 2016.

Return to text

38. The complete title page reads: “Dreyfaches musicalisches Exercitium auf die Orgel, oder VII. PRAEAMBULA und Fugen, nach dem heutigen Goût. Wobey nach jedem Praeambulo der General-Bass heraus gesezet zu sehen ist, um die höchst-nöthige Praeludir-Kunst mit puren Ziffern zu erlernen. Denen Land-Schulmeistern, und überhaupt allen jungen Organisten zur Ubung aufgesezet.” “Three-Part Musical Exercise on the Organ, or Seven Preludes and Fugues in the Modern Style. Whereby after each Prelude, the Thoroughbass is Extracted and Can Be Seen, in Order to Learn the Highly-Necessary Art of Preluding with Only Figures. Prepared for School Teachers in the Country and for the Instruction of All Young Organists.”

Return to text

39. “Aber ob es ohne Regeln durch blosse Clavierstücke geschehen könne, ist schon vorher gezweifelt worden” (Adlung 1758, 734). See Kobrich n.d..

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2020 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

16900