Harmonizing Chorales Systematically: A Translation of G. H. Stölzel’s Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht (Brief and Thorough Instruction), ms. ca. 1719–49

Derek Remeš

KEYWORDS: chorale harmonization, German Baroque, translation, trias harmonica, thoroughbass, counterpoint, pedagogy

ABSTRACT: This article provides the first English translation of a little-known manuscript treatise by the central-German composer and Capellmeister, Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel (1690–1749), titled Kürzer und gründliche Unterricht (Brief and Thorough Instruction, ca. 1719–49). Stölzel’s method frames speculative theory (trias harmonica and the tabula tradition) practically in terms of thoroughbass in order to provide simple instruction on how to invent the bass and middle voices to an original chorale melody. In the second half of the treatise, Stölzel uses thoroughbass to describe not only harmony, but also counterpoint. He does so by explaining various dissonant intervallic constellations in terms of the traditional terms “agent” and “patient,” which describe the two voices involved in a dissonant syncopatio. Stölzel’s treatise thus has both historical and practical value, since his method of chorale harmonization can provide welcome guidance for today's students and pedagogues.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.26.3.7

Copyright © 2020 Society for Music Theory

Part One:

- Introduction [1.1]

- Summary of Stölzel’s Method [2.1]

- Systematic Investigation of Stölzel’s Method [3.1]

- Sample Chorales Harmonized with Stölzel’s Method [4.1]

- Works Cited

Part Two:

- G. H. Stölzel’s Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht (Brief and Thorough Instruction)

- Editorial Principles [5.1]

- Translation and Modern Edition

Part One

Introduction

[1.1] Chorale harmonization has been an integral part of Western musical training for over two centuries. Yet one often hears complaints from students and colleagues alike that chorale harmonization remains a vexing and exasperating process. In part due to such difficulties, some critics, like the authors of the 2014 Manifesto published by the College Music Society, would prefer to see the chorale’s role downplayed in music theory curricula.(1) The Manifesto reflects a growing movement in the English-speaking music theory community at large towards a more culturally inclusive, less technical, and more market-driven curriculum. Chorales—often seen as outdated, overly complex, and irrelevant to today’s musicians—are among the most common candidates for the chopping block.(2) Such criticism is indeed necessary and desirable for the continued relevance of music theory in college curricula, for only through such debate do we come to re-evaluate our collective priorities and methods. It is not the goal of this article to mount a rigorous defense of the enduring pedagogical value of chorales and part writing.(3) Rather, the objective here is to showcase a little-known eighteenth-century source that offers strikingly clear and simple principles by which one can systematically harmonize a chorale. The source offers what is to my knowledge the earliest description of how to invent a bass line to a given chorale melody.(4) Part One of this article outlines the historical context and pedagogical value of the source while also summarizing its contents and developing some of the concepts found therein. Part Two is a parallel translation with modern musical examples and editorial commentary. In sum, this article aims to bring historical theory and modern pedagogy into productive dialogue in hopes of alleviating some of the frustrations that present-day students and teachers frequently encounter when harmonizing chorales.

[1.2] The source under consideration is Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel’s (1690–1749) undated manuscript treatise, Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht (Brief and Thorough Instruction).(5) The scribe of the treatise is currently unknown. Stölzel was a prolific central-German composer, who, after study in Leipzig and travel to Italy and Prague, eventually settled in Gotha in 1719, where he remained until his death in 1749. Since the title page of the Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht names Stölzel as Capellmeister in Gotha, we can date it at least within the years 1719–49. That Stölzel quotes Johann David Heinichen’s 1711 treatise, rather than Heinichen’s 1728 treatise, suggests a potential date between 1719 and 1728, since after 1728 Stölzel presumably would have cited Heinichen’s more recent work, but this remains mere speculation. One assumes Stölzel compiled the “Unterricht” for the numerous pupils who studied with him during this time (Bert 2016). Stölzel’s renown as a composer is attested by the fact that Lorenz Mizler, who admitted him into his Correspondierende Societät der musikalischen Wissenschaften in 1739 (ten years before J. S. Bach), ranked him above Bach in the pantheon of German composers (Hennenberg 2001).

[1.3] The present article may be understood as a contribution to a growing body of literature aimed at reassessing our understanding of the pedagogical role of the chorale in eighteenth-century Germany.(6) Recent philological discoveries have revealed the existence of a long-overlooked pedagogical tradition involving a simple, thoroughbass-centered kind of chorale harmonization. This more basic style differs from that found in J. S. Bach’s vocal chorale settings, which have been held up as idealized microcosms of baroque counterpoint for centuries. Many newly discovered sources also contain multiple basses under each chorale melody, a technique apparently used not only by organists accompanying multiple verses of a chorale in the church service, but also by budding composers in order to develop their variation technique. Interestingly, this thoroughbass-centered, multiple-bass chorale tradition has strong ties to J. S. Bach’s circle of pupils.(7) Through C. P. E. Bach’s account, we know that chorale harmonization played an integral role in his father’s teaching: C. P. E. describes how his father’s students would first add middle voices to an outer-voice framework and then compose their own basses and middle voices.(8) Since Stölzel was a contemporary of Bach, this article opens yet another compelling avenue of inquiry into historical methods of chorale harmonization in Bach’s day. Yet at the same time, we need not reference Bach in order to find historical and pedagogical value in Stölzel’s treatise.

[1.4] It is worth noting that chorale harmonization in itself is not actually Stölzel’s primary goal. Rather, as the full title of his treatise conveys, his goal is to teach the reader “in a short time how to compose a contrapunctum simplex, but without sixths, in four voices.”(9) Simplex means note-against-note counterpoint using only consonant intervals. In this context, the chorale merely provides the point of departure in Stölzel’s method. Yet there certainly would have been easier ways to start instruction for beginners (Stölzel’s target audience), such as with figured bass (as Bach did with his pupils; see note 8). Stölzel probably framed his compositional method within the tradition of chorale harmonization because many of his pupils were likely beginning organists. By combining four-part composition with chorale harmonization, Stölzel thus increased the potential usefulness of his method. The key to Stölzel’s method of inventing a bass line below a given chorale involves a blending of practical and speculative theory: the tabula naturalis and the trias harmonica, respectively. The following is a brief overview of these traditions.

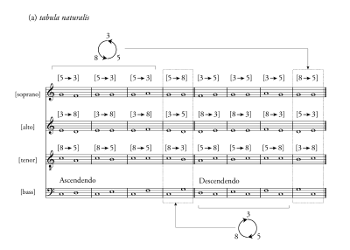

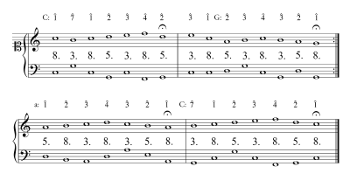

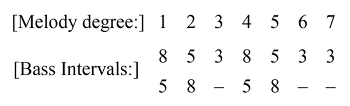

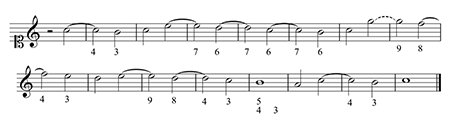

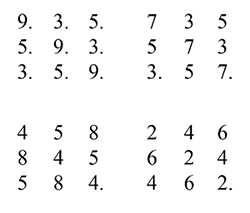

Example 1. Johann Walther’s two tabulae ([1708] 1955, 105–107)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[1.5] The tabula tradition surfaces in various seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century treatises.(10) One of the latest (and historically closest to Stölzel) is Johann Walther’s manuscript treatise, Praecepta der Musicalischen Composition ([1708] 1955). Walther’s formulation of the tabulae is shown in Example 1 (with editorial annotations). The tabulae serve essentially to “automate” the composition of upper voices to a given type of bass motion, either ascending or descending. It is assumed that one begins with two pitches in the bass and one or more notes over the first bass pitch. For instance, the soprano voice begins with a fifth in the far upper-left corner in Example 1a. If the bass ascends by a second, third, or fourth, the soprano should proceed to a third against the bass. As the editorial circles show, the intervallic progressions rotate according to set patterns. Note that the patterns associated with the ascending and descending melodic fifth in the bass actually correspond to the opposite circle. This point is fairly obvious, considering that an ascending fifth inverts to a descending fourth (yet Walther makes no mention of this inconsistency). For simplicity, we will focus on the tabula naturalis in Example 1a, which tabulates the “natural” intervallic progressions. But Walther and other authors also give a tabula necessitatis, which shows the exceptions to the “natural” cases and is only to be used when “necessary.” This is shown in Example 1b. In essence, the necessitatis table reverses the direction of the intervallic progressions shown in the circles in Example 1a. With ascending bass motions, for example, a fifth above the bass now proceeds to an octave above the bass—that is, the intervals shown in the circle now rotate clockwise rather than counter-clockwise.

[1.6] As we can see, the tabula tradition as shown in Example 1 uses exclusively the intervals 3, 5, and 8, or those corresponding to the trias harmonica. Most authors who treat the tabula make note of this relationship. Since the emergence of the trias harmonica in German-speaking lands in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth-centuries, particularly in the writings of Johannes Lippius (1585–1612), it served as a means of conceptualizing the triad within Christian symbolism of the trinity. To what extent the primarily speculative trias harmonica tradition impacted practical composition training throughout the seventeenth-century remains an open question. By the early eighteenth century, trias harmonica theory was on the wane, often being replaced by a more practical approach centered around thoroughbass. But remnants of trias harmonica theory nevertheless played a central role in Stölzel’s method, as we will see in the following section.

Summary of Stölzel’s Method

[2.1] Stölzel’s method of inventing a bass line to a chorale involves first defining the scale degrees of the chorale melody within the major/minor key paradigm, not the modal system. This is somewhat unusual, since older chorale melodies emerged within the modal system and were still understood as modal by many eighteenth-century authors.(11) Since the only treatise Stölzel cites is Heinichen’s Neu erfundene und Gründliche Anweisung (Newly Invented and Foundational Instruction) of 1711, it would seem Stölzel was probably influenced by Heinichen’s emphasis on scale degrees within the major/minor system. Thus, although Stölzel is traditional in his focus on the trias harmonica, he is also progressive in embracing major/minor keys. As far as I know, Stölzel’s method is unique in that he begins by having pupils compose their own chorale melody. This raises the question of whether today’s pedagogues may also wish to preface their instruction on chorale harmonization with a brief discussion of melodic composition. Stölzel’s three rules for composing original chorale melodies are as follows (presumably with a preliminary choice of either a major or minor key):

- The melody may begin with , , or .

- The melody must end with .

- Mostly move by step, sometimes by third or fourth, and very rarely larger than a fourth (ca. 1719–49, 2v–3r).

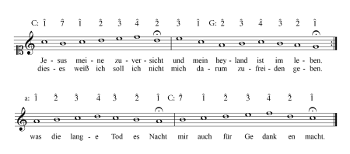

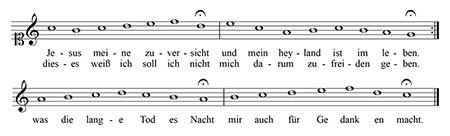

Example 2. Stölzel’s original chorale melody to the text “Jesus meine Zuversicht” (ca. 1719–49, 3r) with his analysis of modulations and scale degrees shown as editorial commentary

(click to enlarge)

[2.2] Additionally, Stölzel writes that in order to compose a chorale melody, the pupil must know that major keys modulate normally to iii, V, and vi (unusually to ii and IV), while minor keys modulate normally to III and v (unusually to VII, iv, and very seldom to VI). This information is taken directly from Heinichen’s 1711 treatise and is the only instance where Stölzel cites another work.(12) Equipped with this knowledge, the pupil is to compose an original melody, presumably to a pre-existing text, which could be borrowed from another chorale. The text determines the phrase length of each line if we assume a purely syllabic setting, as is the case in most chorales. Stölzel’s original chorale melody to the text “Jesus meine Zuversicht” is shown in Example 2. Annotations reflect Stölzel’s own analysis of the modulations and scale degrees. Presumably, the means by which one tonicizes the above-mentioned neighboring keys is to have the chorale phrase end on scale-degree one of that key.

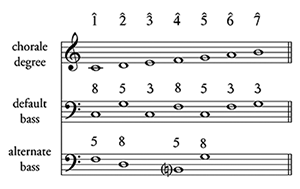

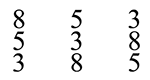

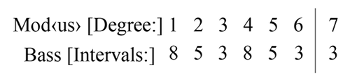

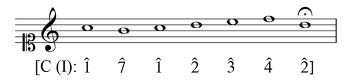

Example 3. Editorial summary of Stölzel’s default and alternate bass intervals below each scale degree in the chorale (ca. 1719–49, 4r)

(click to enlarge)

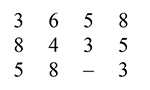

[2.3] What follows is to my knowledge the earliest systematic description of how to invent a bass line to a given chorale melody. Stölzel defines default intervals—3, 5, or 8—that should be added below each scale degree as the bass line. These intervals are determined via the trias harmonica. He also allows for alternate intervals. The rule is that those degrees that have a default 5 have an alternate 8 and vice versa. Example 3 is my summary of these rules in notation. In brief, all melodic degrees may take 5 or 8 below them, except for , , and , which always take 3 (actually a tenth in context). Stölzel makes no note of the fact that the fifth below is a diminished fifth.(13) In this portion of his treatise, he treats the diminished fifth as a consonance, which is a point of difference between Stölzel and Heinichen, who, while admitting that the diminished fifth may enter unprepared, emphasizes that it is nevertheless a dissonance because it still requires resolution (Heinichen 1728, 107).

Example 4. Stölzel’s bassline composed to the chorale in Example 2 using the intervals in Example 3 (ca. 1719–49, 7r)

(click to enlarge)

[2.4] Using the above prescriptions, Stölzel produces the bass line shown in Example 4. Oddly enough, he prohibits consecutive harmonic intervals of all kinds, even parallel thirds (the exception being the consecutives arising through repeated notes) (ca. 1719–49, 5r). But later in his treatise, when discussing the use of the interval of the sixth, he allows for parallel thirds and sixths (ca. 1719–49, 16v). Stölzel also says that the first note of phrase three must take 5 below it to prevent parallel octaves with the last tone of phrase two (ca. 1719–49, 6v). That is, the rules of counterpoint still apply between phrase boundaries. Finally, he advises that , , and are particularly suited for changing keys (ca. 1719–49, 7r). Presumably Stölzel means that these degrees should be taken as the first degree in the new key, as seen in the modulation to G major in phrase two and back to C major in phrase four (see Example 2).

[2.5] The next step is the “translation” of Arabic numerals into notation. This represents a crucial juncture in Stölzel’s method, for the compositional referent shifts from the upper voice to the bass line:

§. 11. In diesen unten gesezten Zahlen steken so wohl die Melodie als der Bass. dahero wir nun die obern fahren laßen, als welche uns hiemit ihre dienste völlig gethan haben, daß wir sie also weiter nicht nöthig haben. doch aber zu zeigen wie in denen erwehnten Zahlen die Melodie u‹nd› zugleich der Bass stekt, wird es nöthig seyn, dieselben in Noten vorzustellen (ca. 1719–49, 7v).

§. 11. The melody as well as the bass is hidden in the figures [in Example 4] in the lower row. Thus, we will now ignore the upper row as though their purpose had been served and we had no more use for them. But in order to show how the melody and the bass are hidden in the mentioned figures, it will be necessary to give them in notation.

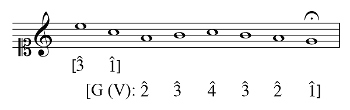

Example 5. Stölzel’s translation of the previous example into staff notation (ca. 1719–49, 8v–8r)

(click to enlarge)

[2.6] Example 5 shows Stölzel’s realization of this process of “translation.” Presumably, his comment that the melody is “hidden” in the figures refers to the fact that, after copying out the bass line, the figures can be used to reconstruct the melody. Next, he asks, “How is one to invent the middle voices, namely the alto and the tenor?”(14) The significance of this question is that, like J. S. Bach’s method of teaching chorale composition, one first composes the bass line in its entirety before adding middle voices. Thus, the alto and tenor voices are methodologically and conceptually reliant on the bass, not the chorale melody. This can be seen in Stölzel’s above statement that one can now ignore the chorale’s scale degrees, “as though their purpose had been served.” That is to say, it would be pointless to make any inferences regarding the middle voices until the bass has been established. Thus from here on, the pupil’s attention is focused on the bass alone.

[2.7] The above-mentioned shift from chorale melody to bass line is significant because it makes the transition from intervallic thinking below a given upper voice to thoroughbass-oriented thinking above a bass line. For this reason, it should come as no surprise that C. P. E. Bach’s description of his father’s teaching (see note 8) contains the statement, “Next he taught them to invent their own basses.” To “harmonize” a melody in Bach’s thoroughbass-centered approach requires first establishing a bass line. Of course, thoroughbass theory is silent on how one would accomplish this, since thoroughbass practice assumes that the bass line is always predetermined. This is probably the reason that Stölzel turns to trias harmonica theory for this pivotal first step of inventing the bass. From here on, he reckons consonance and dissonance from the bass upwards, as in thoroughbass practice (though he treats the diminished fifth as a consonance for now).

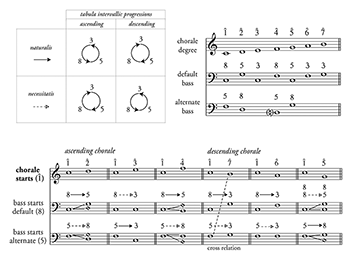

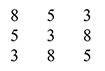

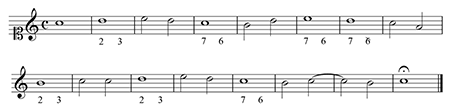

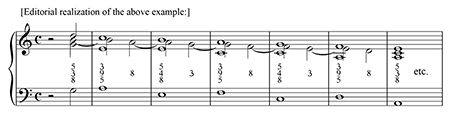

Example 6. The three chords (actually thoroughbass figures) representing Stölzel’s “secret”

(click to enlarge)

Example 7. (a) Stölzel’s application of the “three chords” to Example 4 and (b) his translation into staff notation (ca. 1719–49, 8v–9v)

(click to enlarge)

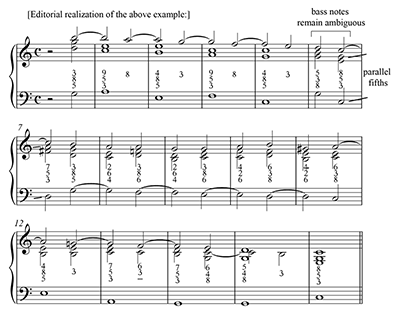

[2.8] Next, Stölzel says that the “secret” to inventing the alto and tenor lies in the three chords shown in Example 6, which represent thoroughbass figures of the trias harmonica in four voices in close position. One takes the chorale melody’s vertical intervals given in Example 5 and matches each one to the highest interval in one of the three chords in Example 6. The remaining figures form the alto and tenor voices in close position below the melody. This will result in a trias harmonica with doubled bass and the upper three voices in close position. See Example 7a for Stölzel’s example of how this is done; Example 7b shows Stölzel’s translation of these figures into staff notation.

[2.9] Stölzel advises that such a bare setting is in need of embellishment:

§. 14. dieses ist also eine Composition à 4 über das lied [“]Jesus meine Zuversicht[”]. welche nach denen regulis harmoniæ nicht zu tadeln, und durch angewendete transitus u‹nd› andere figuren hin u‹nd› wieder agreable zu machen ist. Und dergleichen sind auß diesen gegebenen wenigen principiis unzehlig zu machen (ca. 1719–49, 9v).

§. 14. This is a four-voice composition on the [original melody to the] chorale, “Jesus meine Zuversicht.” It is proper according to the rules of harmony, [yet] can be made more pleasing through the addition of transitus [passing notes] and other figures. Such figures, which are derived from these few principles, are innumerable.

Precisely which “principles” Stölzel is referring to is unclear. Presumably he means the method just described, by which he derived the bass line and the inner voices using the intervals of the trias harmonica.

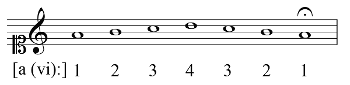

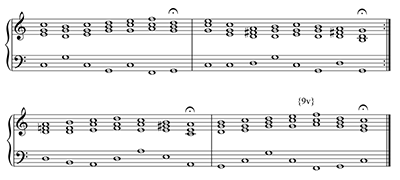

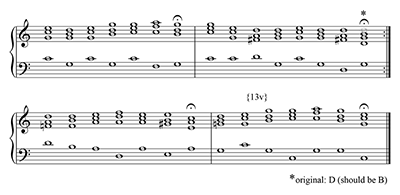

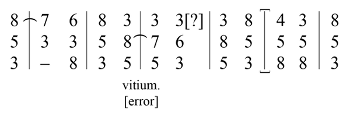

Example 8. Stölzel’s two alternate realizations starting in fifth position and third position (ca. 1719–49, 11r–13v)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.10] Next, Stölzel shows how the upper voices can be swapped, as seen in Example 8. That Stölzel emphasizes this technique is likely the influence of Heinichen. In both his 1711 and his 1728 treatises, Heinichen gives many of the thoroughbass examples in all three starting positions. A position refers to the starting interval between the outer voices: either an octave, third, or fifth (assuming the first harmony is a 8/5/3 chord). The most interesting thing about Example 8 is that, even when the diminished fifth is present in the outer voices (see the pointing hand in Example 8b), Stölzel does not resolve it inward to a third. This likely results from a desire to simplify his method for beginners, since Stölzel is certainly aware that the diminished fifth is a dissonance.(15)

[2.11] Thus far, Stölzel’s approach has limited the pupil exclusively to 8/5/3 chords. In contradiction to the title of the treatise (which claims that sixths will be excluded), he next introduces how to use the sixth. This is governed by the following rules:

[1] N.B. wenn in denen Mittel-Parthien ein hemitonium so per gradum steiget vorkömt, kan solches in den Bass gesezet u‹nd› der Bass-Sonus an deßen Stelle in die Mittel Parthie gesezet werden. So hat man den ersten Gebrauch der Sexten. oder kürzen wenn der andere u‹nd› fünffte Thon die Qvinte mit der 3. majori unter sich haben[.]

[2] Nb wenn statt der natürlichen hemitoniorum die Melodie p‹er› tonum steiget, zum Exempel e fis, oder h cis hat unter dem fis u‹nd› cis die sexte statt.

[3] Nb wenn die Melodie in einem tone liegen bleibt, und der Bass auß der octave per tertiam steigt kan die lezte Note die Sextam haben.

[4] Nb wenn die Melodie per hemitonium steiget hat bey der ersten Note die 6te statt.

[5] Nb wenn die Melodie auß dem Fundament-Thon umb ein hemitonium fält, gleich aber wieder in den Fundament Thon gehet, kan der mittelste die Sexte haben.

[6] Es können alle 7 tone die Sexte [m]it 3. verimdtelt[??] haben. so wohl ascendendo als descendendo nach ein ander haben (ca. 1719–49, 15v–16r).

~ ~ ~

[1] N.B. When an ascending [chromatic] semitone appears in the middle parts, this can be set in the bass and the bass note can be set where the middle voice was [the two can be inverted]. In this way one achieves the first use of the sixth [when a third is inverted]. Or, put briefly, when the second and fifth degrees have a fifth below them and a major third above this fifth [then the third can be placed in the bass].

[2] N.B. When the melody ascends by whole tone instead of by diatonic semitone, e.g. e–

f♯ or b–c♯ , then thef♯ andc♯ have a sixth below them.[3] N.B. When the melody repeats a tone and the bass ascends by third from the octave [below this melody tone], the last [bass] note can [sic will] have the sixth.

[4] N.B. When the melody ascends by semitone, the first note has a sixth [below it].

[5] N.B. When the melody descends by semitone from the first degree and immediately returns to the first degree, the middle note can have the sixth.

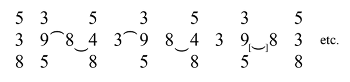

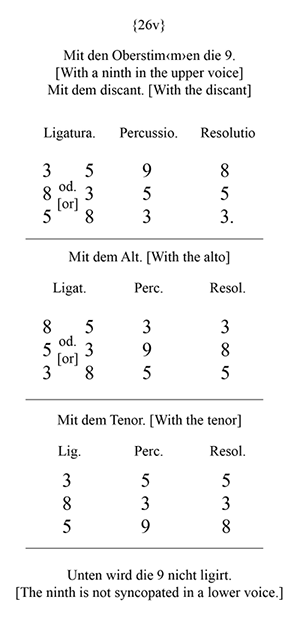

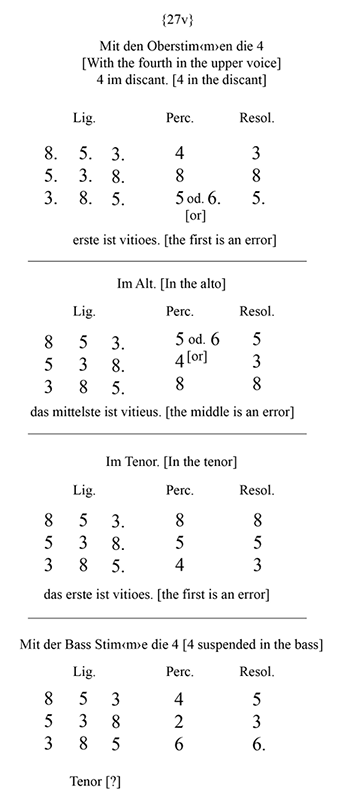

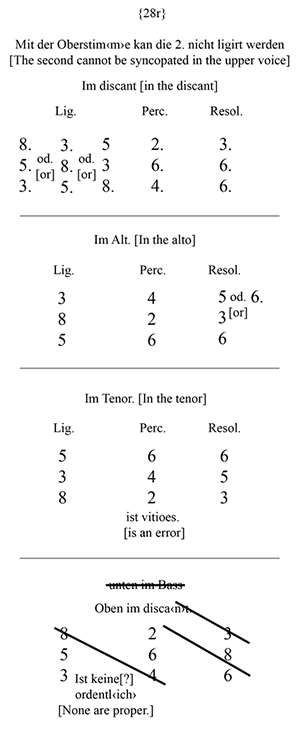

[6] All seven degrees may have the sixth [below them] with third [above this bass note] consecutively, both ascending and descending.

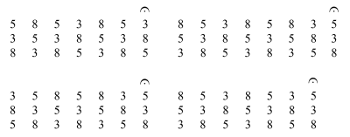

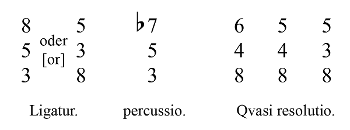

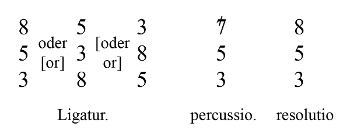

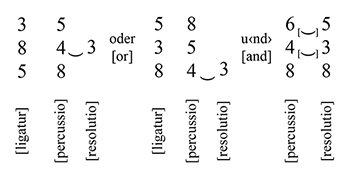

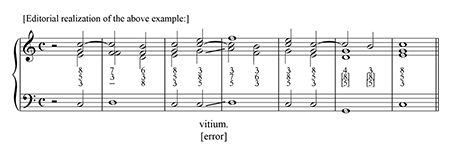

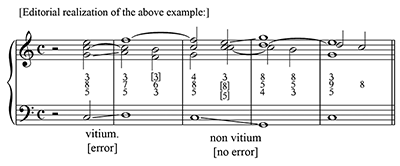

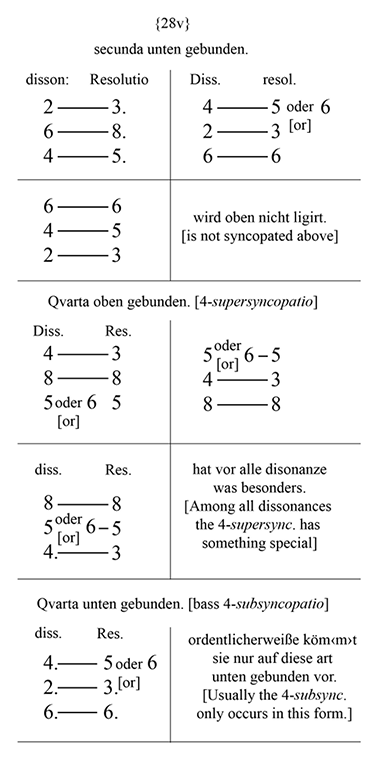

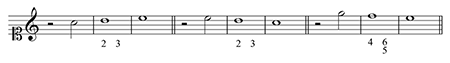

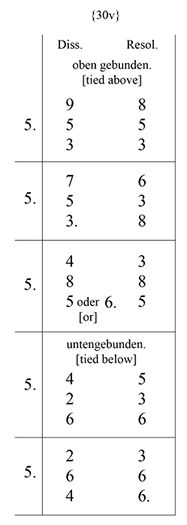

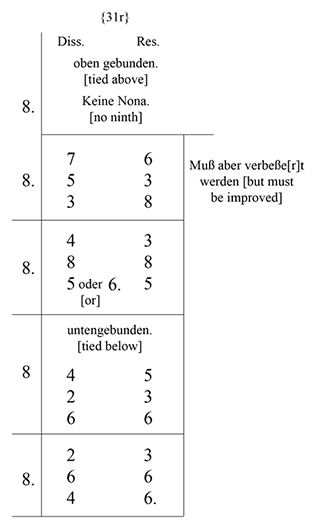

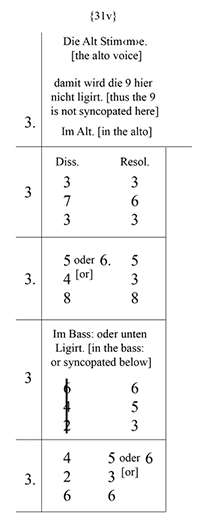

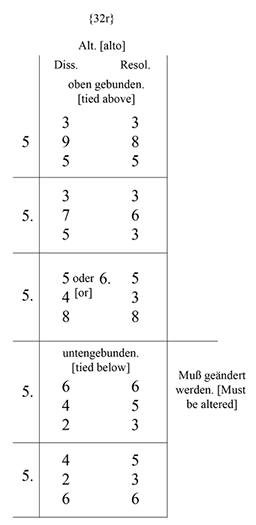

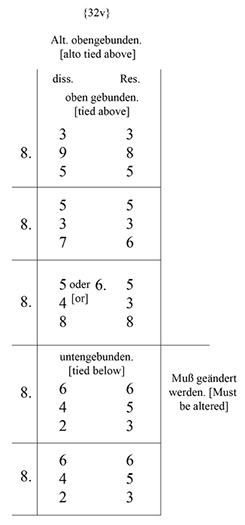

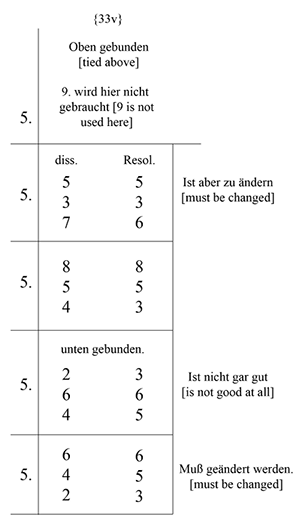

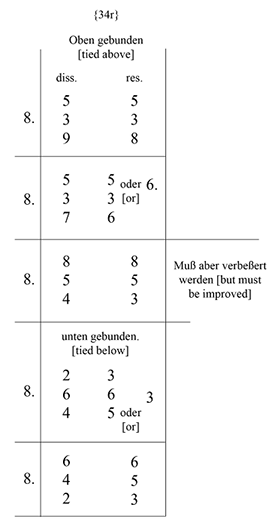

[2.12] Following this, Stölzel introduces the concepts of transitus regularis (unaccented passing) and transitus irregularis (accented passing), which always occur between the interval of a third (ca. 1719–49, 16v). The remainder of the treatise (folios 17r to 34r) explains the use of syncopatio dissonances, or what Stölzel calls ligatur. Both syncopatio and ligatur are historical terms for a suspension, but with important differences. Whereas a suspension implies the delayed arrival of a chord tone, both syncopatio and ligatur were understood dyadically as an intervallic, rather than a chordal, phenomenon. Stölzel systematically describes syncopatio dissonances for the intervals 2, 5, 7, and 9 in the discant, alto, tenor, and bass voices with different types of auxiliary voices and resolutions. When the tied voice is on top, one speaks of supersyncopatio; when it is in the bass, one speaks of subsyncopatio.(16) Though Stölzel no longer discusses chorale melodies in his treatise, the implication is that the instruction on syncopatio dissonances represents the above-mentioned “innumerable” figures, which are to be applied to the settings in Examples 7 and 8. Overall, Stölzel’s entire description of syncopatio dissonances is valuable for the modern reader, as it demonstrates the traditional, seventeenth-century manner of understanding dissonance as a dyadic, rather than a harmonic, event.

Systematic Exploration of Stölzel’s Method

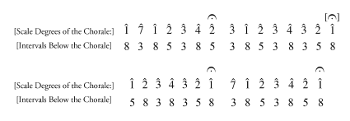

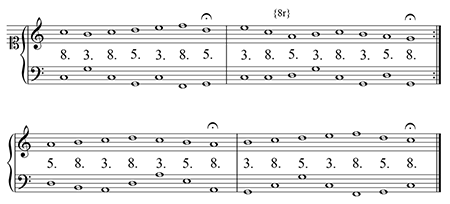

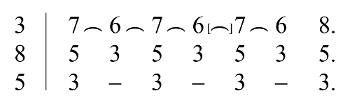

[3.1] I would like to return to Example 3 since, as stated already, it represents the earliest systematic explanation of how to compose a bass line to a chorale melody. It may have already occurred to the reader that there are not that many possible progressions. With this in mind, I set out to answer the question: How do Stölzel’s available bass intervals interact with the available progressions of the tabula tradition? What piqued my curiosity in particular was Stölzel’s restriction that the pupil’s original chorale melodies not make melodic leaps larger than a fourth—the underlying logic of two tabulae also applies up to the interval of a fourth; at the fifth, intervallic pattern reverses, as shown in Example 1.

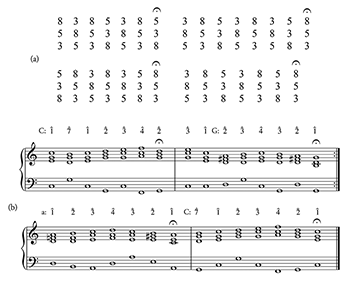

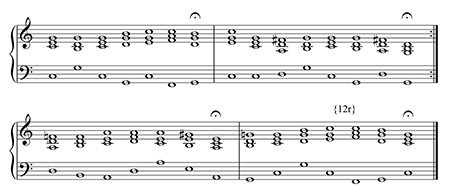

Example 9. A systematic exploration of the available major-key interval progressions in Stölzel’s method (see Example 3) and their interaction with the tabula tradition (Example 1)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.2] Example 9 catalogues all available two-voice progressions in a major key, modeled in C major. Each staff shows the six available melodic progressions of the chorale (by second, third, or fourth), either ascending or descending. Repeated notes in the chorale were not considered. The middle staff begins with Stölzel’s “default” interval as shown in Example 3; the third staff begins with his “alternate” interval. Diamond-shaped noteheads represent invalid progressions based on the following principles:

- parallel 5–5 and 8–8 progressions are not allowed;

- contrary 5–5 and 8–8 progressions are allowed;

- similar motion to 5 or 8 is allowed when one voice moves by step;(17)

- no melodic diminished 5 or augmented 4 is allowed in either voice;

- an outer-voice diminished 5 need not resolve in any particular way (see Example 8).

[3.3] I decided to allow for cross relations (i.e., augmented or diminished intervals between consecutive notes in opposite voices). While these would normally be prohibited in a strict two-voice setting, it is assumed that two middle voices will eventually be added, resulting in a four-voice setting. A fuller texture helps ameliorate cross relations.

[3.4] I analyzed each of the resulting valid progressions in Example 9 according to whether they fit the naturalis intervallic pattern or the necessitatis intervallic pattern given in Example 1 for ascending and descending motion. An arrow with a solid line indicates the naturalis pattern, a dashed line the necessitatis pattern. The motivation was the hypothesis that Stölzel’s method may be based on a sort of “tabula for chorales.” I expected to find some correlation between Stölzel’s method and the tabulae patterns, but they seem not to correlate. Still, the exercise was not in vain. It is interesting to see that, of 102 possible progressions, only 84 are valid according to the above proscriptions. (Only 80 would be valid if we added Stölzel’s prohibition of identical consecutive intervals of all kinds.) That is, Stölzel’s method as shown in Example 3 is not an absolute guarantee that the resulting bass line will be valid, if we assume the above-mentioned conditions.

Sample Chorales Harmonized with Stölzel’s Method

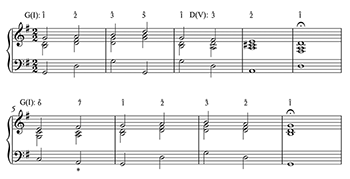

Example 10. The chorale “Gott des Himmels und der Erde” harmonized using Stölzel’s method

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.1] In this section, we examine two chorales that I harmonized using Stölzel’s method. The goal is to model the application of Stölzel’s method for use in today’s classroom. The first setting, shown in Example 10, uses the chorale “Gott des Himmels und der Erde” (Zahn [1889–93] 1963, 2:460). Like Stölzel, I began by analyzing the scale degrees of the chorale melody, without any concern for common tones between keys. Inferring from Stölzel’s instruction, I took the ends of all phrases to be in their respective keys. Measures 5–6 posed a problem, since and in the chorale both take a third (or tenth) in Stölzel’s method, which could create parallel fifths and octaves after the middle voices are added. So for the

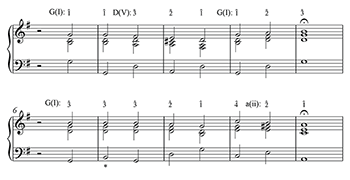

Example 11. The chorale “Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir” harmonized using Stölzel’s method

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.2] Example 11 is a setting of the chorale “Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir” (Zahn [1889–93] 1963, 1:134). Here I followed the same working strategy as in the previous example. The third phrase avoids a cadence in G major by interpreting the cadence in E minor. As in Example 10, the outer-voice consecutive perfect intervals in contrary motion (here 8–8) straddling mm. 3–4 were allowed.

[4.3] Neither Example 10 nor Example 11 are particularly brilliant. The bass lines are at times what G. P. Telemann referred to as a “timpani harmony” (Pauken-Harmonie) (1730, 183). Nevertheless, the settings are competent and thus represent an excellent starting point for beginners. Note especially that the resulting setting is quite different from J. S. Bach’s highly ornate, vocal Choralgesänge, which are very often held up as historically informed models. Stölzel’s settings—along with a whole host of recently surfaced sources—suggest that this type of simpler, keyboard-based chorale setting was actually the norm in the eighteenth-century, since it was organists who had to accompany chorale singing in the church service. By restricting the compositional possibilities to such a high degree, Stölzel offers a very practical method that is easy to implement. Further, it can be incrementally expanded by allowing for more exceptions, like 6/3 chords, chromaticism, and transitus and syncopatio dissonances. Stölzel’s treatise thus offers a method of chorale harmonization that is at once historically rooted and practicable. Such incorporation of historical teaching methods into present-day curricula offers a promising path forward for pedagogues who wish to continue teaching chorale harmonization.

Part Two

G. H. Stölzel’s Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht (Brief and Thorough Instruction)

Editorial Principles

[5.1] The manuscript of Stölzel’s Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht was deciphered with the help of Maria Richter, a professional transcriber of historical German texts (quellenlese.de). Her stated editorial principles, which I have adopted in the English translation as well, are as follows:

- no distinction is made between German and Latin words in the transcription, except when a section’s header is Latin, in which case it is given in italics;

- ‹…› indicates editorial completion of an incomplete word;

- «…» indicates original text added after the original text (i.e. as marginalia);

- […] indicates editorial additions, and in select occasions, a translation;

- {…} indicates missing text.

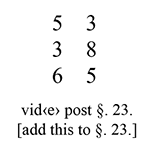

[5.2] Original folio numbers are given in the left-hand column in curved brackets thus: {2r}. In the tables that conclude the “Unterricht,” the translation is simply given in square brackets: […]. Struck text in the original is also struck in the reproduction. As in Part One, the translation in the right-hand column uses Arabic numerals with carets to indicate scale degrees. The relationship of neighboring keys to the main key is shown as a Roman numeral, even though this is not the case in the original: C(I), G(V), a(vi), etc.

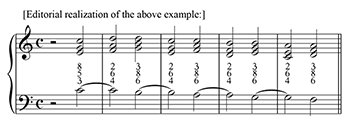

[5.3] Stölzel’s rather odd and to my knowledge unique form of notation deserves mention. Often, he only gives the intervals of the three voices above the bass, without including the bass line. I have included editorial realizations for most of these examples. The trick to understanding this notation, I believe, is to use the syncopatio dissonances as a point of reference. As Stölzel notes, the syncopatio will be prepared by common tone and resolved down by step. From this one can infer the other voices. Lastly, it would seem that the treatise may have been compiled in a hurry, since, in a few instances, there are addenda referring to earlier paragraphs. This, together with various scratched out passages, suggest that the treatise was prepared only informally and was therefore perhaps used in private instruction. To this end, it remains uncertain whether the scribe is Stölzel himself or perhaps one of his pupils.

G. H. Stölzel’s Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht (Brief and Thorough Instruction)

Transcription and Translation

|

Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht, wie ein Liebhaber der Music, welcher die Intervalla Musica kennet, und durch die Noten aufzuschreiben weiß, In einer kurzen Zeit, einen Contrapunctum Simplicem, doch ohne Sexten, mit vier Stim‹m›en zu sezen Erlernen kan. Vom Capellmeister Stölzel in Gotha |

Brief and thorough instruction on how a lover of music who understands musical intervals and knows how to notate all the notes can learn in a short time how to compose a contrapunctum simplex [1:1 consonant setting], but without sixths, in four voices. From the Capellmeister {G. H.} Stölzel in Gotha(18) |

{2r} Musica noster Amor. |

Music, our love. |

§. 1. wer sich dieser leichten Methode zu Erlernung eines vierstimmigen Contrapuncti Simplicis ohne Sexten, bedienen will. Muß vorhero nothwendig die außweichungen der Tone wißen. |

§. 1. Whoever wishes to make use of this simple method of four-voice contrapunctum simplex without sixths must first know the modulatory options of the keys. |

§. 2. hiezu dienet folgende einzige Regul. Alle Tone dur weichen ordentlich aus in 3 5 u‹nd› 6 außer ordentlich in 2 u‹nd› 4. Hingegen alle Tone moll weichen ordentlich auß in 3. 5. außer ordentlich in 7 4 u‹nd› sehr selten in 6‹b.› Heinichens anweisung zum GeneralBass. p‹agina› 211. |

§. 2. In this the following rule is useful: all major keys modulate normally to the keys iii, V, and vi, unusually to ii and IV; in contrast, all minor keys modulate normally to III and v, unusually to VII, iv, and very seldom VI. [See J. D.] Heinichen’s Anweisung zum General-Bass [[1711] 2012], p. 211[–12].(19) |

|

{2v} §. 3. Hat er sich hierinnen und zwar nur in denen Tonen, so er zu seinen Entzwek für nöthig hält; veste gesezet; so fängt er nunmehro an eine Melodie zu sezen. Wobey er folgende Reguln zu Observiren hat.

|

§. 3. If he [the pupil] has become proficient in identifying those keys that are necessary for the task, then he can begin to compose a melody, wherein he should observe the following rules:

|

Z‹um› E‹xempel› wir wollen über ein bekandtes lied eine Melodie sezen. |

For example, we should like to set a melody over a well-known song [i.e., chorale text]. |

{3v} Indieser Melodie ist nach der 1. Regul observirt worden daß Sie in der Octave anfängt oder wie wir künfftig reden werden, im ersten Clavi des Modi C. und in diesem Modo modulirt diese Melodie biß auf die zehende Note, über der ersten Sylbe des wortes Heyland. da sie in den Modum G dur oder in die Qvinte außweichet. Über den worten "was die lange Todes Nacht, weicht sie aus in A moll oder die Sexte, hernach biß zum Ende bleibet sie in dem Fundament-Modo. |

This melody observes the first rule in that it starts with the octave [], or as we will say from now on, in the first degree of C [major]. The melody modulates in the key of C until the tenth note over the first syllable of the word “Heyland,” where it modulates to the key of G major, or to the [key of] V. Over the word, “was die lange Todes Nacht,” the melody modulates to A minor, or vi, after which it remains in the main key.(21) |

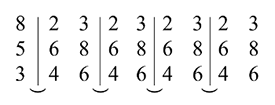

§. 4. Unter diese Melodie soll nun ein Bass nebst zweyen Mittel Stim‹m›en Alt u‹nd› Tenor {4r} gesezt werden. da dann auf{f} alle Noten des Modi genau{e} Achtung zu geben ist, wie nehml‹ich› solche in Ansehung des Basses accompagnirt werden. |

§. 4. A bass and two middle voices, alto and tenor, shall now be set under this melody, whereby one must determine precisely the scale degrees or all notes when setting the bass. |

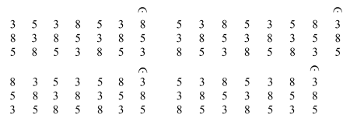

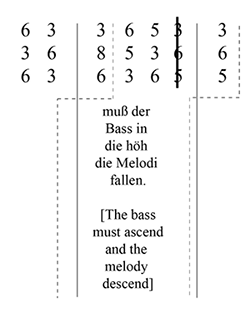

§. 5. Ist demnach zu wißen, daß ordentlicher u‹nd› natürlicher weiße der erste Thon des Modi die Octave zum Bass, der andere die 5te u‹nd› der drite die tertie, der 4te wieder die Octave der 8te [sic, 5te!] die 5te u‹nd› der sechßte abermahls die tertie, endlich der siebende als das hemitonium unter dem Fundament Clavi die 3tie ingleichen zum Bass hat. welches aus folgenden Zahlen auf einmahl zu sehen ist. {4v} |

§. 5. Thus one must know that it is common and natural for the first degree of the key to have an octave [below it] in the bass, the second degree the fifth [below it], the third degree the third [below it], the fourth degree again the octave [below it], the eighth [recte: fifth!] degree the fifth [below it], and sixth degrees once more the third [below it], and finally the seventh as the semitone under the fundamental [first] degree has the third [below it] in the bass. This can be seen in the following figures.(22) |

§. 6. weil aber bey gewißen umständen, nothwendig diese Ord[n]ung unter brochen werden muß, so ist nöthig daß wir eine Regul darüber abfaßen, welche in folgenden worten bestehet: |

§. 6. Since in certain situations one must necessarily deviate from the above arrangement, it is therefore necessary that we draw up a rule concerning it, which can be formulated as follows: |

Die Tone welche die 8ve unter sich haben, können auch die 5te unter sich leiden, und diejenigen, welchen die 5te kan zum Basse dienen, denen kan auch die 8ve solchen dienst thun. hingegen, wo die tertia einmahl stehet bleibt sie un veränderlich. |

The [melody] tones that have an octave below them can also have a fifth under them, and those [tones] for which the bass can have a fifth may also have an octave, [but] where the third is set, no other option is possible.(23) |

Die Regul ist leicht zu behalten; doch in folgenden Zahlen liegt sie auch {5r} vor den Augen. |

The rule is easy enough to remember, but it is [nevertheless] given again in the following figures: |

§. 7. Nun mehro können wir zu obiger Melodie den Bass sezen, wenn wir nur noch folgende Regul voran gesezet haben. Zwey gleiche Zahlen als 1.1. 2.2. 3 3. 4.4. etc. können hier ein ander nicht folgen; Es wäre denn, daß die Melodie einen Sonum mehr als einmahl mit ebendenselben Bass repetirte. |

§. 7. Now we can compose a bass to the above melody if we merely adhere to the following rule: two of the same figures [intervals], such as 1.1., 2.2., 3.3., or 4.4., etc. may not follow consecutively unless the melody repeats its pitch more than once with the same bass [note].(24) |

{5v} §. 8. doch nunmehro zum werk. |

§. 8. And now we return to the melody: |

diese sieben Noten, werden nun in denen Zahlen nach der Ord[n]ung wie sie im Modo liegen folgender Gestalt vorgestellet. |

These seven notes are now presented as figures in the following way according to their ordering in the key: |

diese 8 Noten sehen In denen Zahlen also auß: Es ist oben schon gesagt worden daß der Modus bey der gehenden Note außweiche, und zwar ins G dur oder in {6r} die qvinte, dahero dann die zehende Note nicht mehr in den Modum C dur gehöret per conseqvens auch nicht mehr, wie vorhin die sechste, sondern numehro in dem neuen Modo die andere ist, und so fort mit denen übrigen. dahero

der Bass also stehet: |

These eight notes appear thus as degrees: It was already mentioned above that the key changes when the stepwise notes begin [on the third note: a], namely in G major or in the [key of the] fifth [degree]. Thus, the tenth note [the third note in the above example] no longer belongs to C major. As a result, it is no longer the sixth degree, but now in the new key it becomes the second degree, and so forth with the remaining [notes]. Thus, the bass would also be as follows: |

diese sieben Noten sind nach dem Modo A moll als worein nunmehro die Melodie tritt, zu zehlen. Doch weil die lezte

von denen vor[i]gen die 8ve unter sich hat, so kan der obigen gegebenen Regul zu Folge die Octave {6v} nicht noch einmal folgen sondern […?] kan die qvinte an statt der Octave nehmen; und weil die folgende 2«dere» note des Modi der natürlichen Ord[n]ung nach die 5te unter sich haben solte; doch aber zu vor hero schon eine qvinte vorher gehet; so kan die 8ve drunter stehen mit hin u‹nd› wenn in folgenden die Ord[n]ung wieder natürl‹ich› fortgeführet

wird, stehen die Bass-Zahlen also: |

These seven notes can be described in the key of A minor in the following way. But because the last [note] of the previous [phrase] has an octave below it, the octave may not follow again according to the above rule [i.e., no parallel perfect intervals even between phrases]. Instead, [the first pitch of the third phrase] can take the fifth instead of the octave. And because the following second degree should have a fifth below it according to the natural arrangement, but now is preceded by a fifth, the second degree can take an octave beneath it. Thus, when the arrangement [of bass intervals] is made in the natural manner, the bass figures [intervals] appear thus: |

diese sieben Noten weil sie wiederum in den Modum C dur gehören, sehen in {7r} Zahlen also aus: |

Because these seven notes belong again to C major, they appear in this way as degrees: |

§. 9. Hiebey ist noch mit zu nehmen, daß die mit der 3tie alleine accompagnirten Noten so wohl zum Changement der Modorum als auch zu derselben Retour in den haupt Modum gar sehr incliniren. welches zu einen großen avertissement dienen kan. «‹…› vide infra.» |

§. 9. Here one should be aware that notes only accompanied by a third [, , ] are very suited to both a change of key, as well as a return to the main key, which is a significant advantage.(25) |

§. 10. Nunmehro wollen wir unsere Zahlen in eine Reyhe bringen. |

§. 10. Now we wish to bring our figures in the same row: |

§. 11. In diesen unten gesezten Zahlen steken so wohl die Melodie als der Bass. dahero wir nun die obern fahren laßen, als welche uns hiemit ihre dienste völlig gethan haben, daß wir sie also weiter nicht nöthig haben. doch aber zu zeigen wie in denen erwehnten Zahlen die Melodie u‹nd› zugleich der Bass stekt, wird es nöthig seyn, dieselben in Noten vorzustellen. |

§. 11. The melody as well as the bass is hidden in the figures in the lower row. Thus, we will now ignore the upper row as though their purpose had been served and we had no more use for them. But in order to show how the melody and the bass are hidden in the mentioned figures [the lower row], it will be necessary to give them [both rows] in notation.(26) |

hieraus ist zu sehen, daß die Zahlen allezeit richtig das Intervallum welches der Bass u‹nd› discant miteinander machen anzeigen. |

From this one can see that the figures indicate correctly at all times the interval that is formed by the bass and the discant. |

§. 12. Izo fragt sichs, wie nun die Mittel Stim‹m›e[n] als der Alt u‹nd› Tenor dazu zu erfinden seyn? Dieses Geheimniß aber liegt in folgenden dreyen Säzen vor {8v} Augen. |

§. 12. The question then arises: How is one to invent the middle voices, namely the alto and the tenor? This secret lies in the following three chords [which represent thoroughbass figures]: |

§. 13. Die Operation wird folgender Gestalt verrichtet. Man sezet unter jede Zahl welche bekandter maßen schon den Bass u‹nd› Discant in sich faßet, in der Ord[n]ung welche obige 3 Säze zeigen, noch zwey Zahlen, so müßen solche zum Alt u‹nd› Tenor dienen. unser Exempel sieht also aus: |

§. 13. The procedure takes the following form: one sets the remaining two figures in the above ordering beneath that figure which is already indicated between the bass and the discant. These serve as the alto and tenor. Our example appears as follows:(27) |

In Noten stehen diese Zahlen wie folget. |

These figures appear like this in notation: [original is in open score with c-clefs] |

§. 14. dieses ist also eine Composition à 4 über das lied Jesus meine Zuversicht. welche nach denen regulis harmoniæ nicht zu tadeln, und durch angewendete transitus u‹nd› andere figuren hin u‹nd› wieder agreable zu machen ist. Und dergleichen sind auß diesen gegebenen wenigen principiis unzehlig zu machen. {10r} |

§. 14. This is a four-voice composition on the [original melody to the] chorale [text], “Jesus meine Zuversicht.” It is proper according to the rules of harmony, [yet] can be made more pleasing through the addition of transitus and other figures. Such figures, which are derived from these few principles, are innumerable.(28) |

§. 15. wegen derer hin u‹nd› wieder anzuwendenden Signorum ‹ |

§. 15. Space does not permit the listing of rules for the use of accidentals [key signatures other than C major and A minor], which occasionally come into use. One must already have gained proficiency with this topic. Only this should be added: that [to form a scale] in every key, the fifth degree required a major third [above it] and the second degree requires a minor third [above it]. Similarly, in any minor key, the fourth and first degrees require a minor third [above them], but in a major key [both fourth and first degrees] require a major third. |

§. 16. Auß unserer Melodie aber wenn die Cadenzen verändert würden, köndte{n} noch zwey andere Melodien entspringen. wir wollen Sie erstlich ohne Veränderung der Cadenzen ansehen. |

§. 16. If the cadences were altered in our melody, two different melodies could result. [But] We would like to examine them first without altered cadences.(29) |

§. 17. die andere Melodie entspringet aus der ersten folgender gestalt. wenn der Alt zum discant, der Tenor zum Alt u‹nd› der Discant zum Tenor gemacht wird. oder wen{n} unter die Zahlen der Alt Stim‹m›e nach obigen drey Säzen zwey Zahlen gesezet werden. Im lezten Fall sieht das werk {11r} also aus. |

§. 17. The second melody is derived from the first in this way: when the alto is made into the discant, the tenor into the alto, and the discant into the tenor. Or [put another way], when two figures are set above the figures belonging to the alto voice in the above three chords. In the latter case, the composition would look like this:(30) |

In denen Noten aber folgender Gestalt. |

In notation, the setting looks like this [originally in open score with c-clefs]. |

Si Volti {11v} |

See the following page. |

§. 18. die dritte Melodie entspringet aus der Ersten auf diese weiße, wenn nehml‹ich› der Tenor zum Discant der Discant zum Alt, und der Alt zum Tenor gemacht wird. oder wenn unter die Zahlen des Tenors nach denen dreyen Säzen jedesmahl zwey andere Zahlen ge-{12v}-sezt werden. und in diesem falle steht die Harmonie also: |

§. 18. The third melody derives from the first one in this way: when, namely, the tenor is made into the discant, the discant into the alto, and the alto into the tenor. Or [put another way], when two figures are set above the figures belonging to the tenor voice in the above three chords. In this case the harmony would appear thus: |

In Noten also: {13r} |

In notation it looks like this [originally in open score with c-clefs]: |

§. 19. So man aber diese Melodien würklich brauchen wolte; So müsten nothwendig die Clausuln verändert werden, und zwar vornehml‹ich› diejenigen welche in dem Fundament-Thon des Modi darinnen die Melodie sich befindet geschiehet. Mit denen andern in {14r} der qvinte hattees[?] so viel nicht zu sagen. welches aber nebst dem Gebrauch der Sexte, und der Dissonantien, umb einen liebhaber dieses ersten Fundamentes nicht confus zu machen, billig außgesezt bleibet. |

§. 19. But if one really wanted to use these melodies, the clausulae would need to be altered, specifically those in which the melody closes in the first degree of the key. We need not address those clausulae closing in the fifth. This topic, together with the use of sixths and dissonances, is omitted here in order that the amateur not be confused regarding basic, foundational knowledge.(31) |

§. 20. Inzwischen kan dieses wenige anlaß geben, die wunderliche u‹nd› beständig harmonieuse verwechselung derer in triade harmonica liegenden dreyen sonorum etwas genauer an zusehen, und den Gott der Ord[n]ung {14v} in solcher betrachtung zuverehren. |

§. 20. Nevertheless, this gives reason to observe in greater detail the wonderful and invariable harmonic inversion of the three pitches of the trias harmonica and to praise the God of order in this regard. |

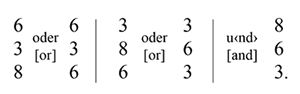

das Accompagnement der Sexte ist folgendes |

The accompaniment of the sixth is as follows.(32) |

{15r} ad §. 9. das gewißeste Merkmahl der außschweiffung des Modi ist, das hemitonium unter dem ersten Thon oder der siebende Thon jedes Modi. So offt man nun in der Melodie ein hemitonium, außer denen [«2 hemitonie»] so natürlich in jeden Modo sind, sezet so offt ist es eine Marqve daß der Thon auß weicht. wann nach dem unter dem Fundament-Thone liegenden hemitonio ein ganzer Thon descendendo «oder ascendendo» folgt, oder wenn solches hemitonium umb einen Grad fält [=steigt] «oder fält.», denn von Natur muß es steigen, changirt der Modus. das lezte ascendendo gielt auch beyn ander hemitonio unter der qvarte. |

Addendum to §. 9. above. The surest sign of modulation is the semitone below the first degree, or the seventh degree of any key. Every time one sets a semitone in the melody [via the addition of an accidental], except for the two [diatonic] semitones that occur in every key naturally [between - and - in major, - and - in minor], this is a sign that the key modulates. When a whole tone descent or [semitone] ascent follows after the [chromatic] , or when it descends by step [?], then by nature it [] must ascend, which changes the mode. The last ascent also applies to the other semitone below the fourth [between - in major].(36) |

{15v} N‹ota› b‹ene› wenn in denen Mittel-Parthien ein hemitonium so per gradum steiget vorkömt, kan solches in den Bass gesezet u‹nd› der Bass-Sonus an deßen Stelle in die Mittel Parthie gesezet werden. So hat man den ersten Gebrauch der Sexten. oder kürzen wenn der andere u‹nd› fünffte Thon die Qvinte mit der 3. majori unter sich haben |

N.B. When an ascending semitone appears in the middle parts, this can be set in the bass and the bass note can be set where the middle voice was [the two can be inverted]. In this way one achieves the first use of the sixth [when a third is inverted]. Or, put briefly, when the second and fifth degrees have a fifth below them and a major third above this fifth. |

N‹ota› b‹ene› wenn statt der natürlichen hemitoniorum die Melodie p‹er› tonum steiget, zum Exempel e fis, oder h cis |

N.B. When the melody ascends by whole tone instead of by diatonic semitone, e.g. e– |

N‹ota› b‹ene› wenn die Melodie in einem tone liegen bleibt, und der Bass {16r} auß der octave per tertiam steigt kan die lezte Note die Sextam haben. |

N.B. When the melody repeats a tone and the bass ascends by third from the octave [below this melody tone], the last [bass] note can [will] have the sixth. |

N‹ota› b‹ene› wenn die Melodie per hemitonium steiget hat bey der ersten Note die 6te statt. |

N.B. When the melody ascends by semitone, the first note has a sixth [below it]. |

N‹ota› b‹ene› wenn die Melodie auß dem Fundament-Thon umb ein hemitonium fält, gleich aber wieder in den Fundament Thon gehet, kan der mittelste die Sexte haben. |

N.B. When the melody descends by semitone from the first degree and immediately returns to the first degree, the middle note can have the sixth. |

Es können alle 7 tone die Sexte [m]it 3. verimdtelt[??] haben. so wohl ascendendo als descendendo nach ein ander haben. {16v} |

All seven degrees may have the sixth [below it] with third [above this bass note] consecutively ascending as well as descending [i.e. three-voice fauxbourdon]. |

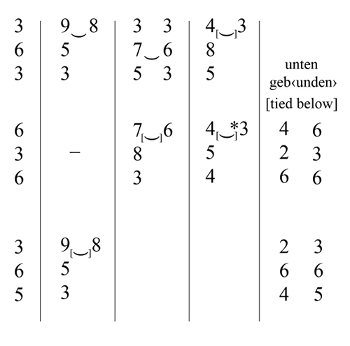

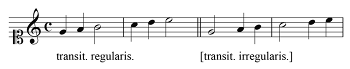

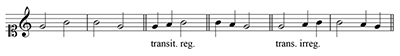

Von den Dissonanzen in transitus ordentl‹ich› wenn die Stim‹m›en per gradus gehen muß eine «Note» gut u‹nd› die andere kan falsch seyn. gehen sie aber per saltus müßen sie alle gut seyn. gehen ihrer zwey mit ein ander muß es in tertien oder in 6ten geschehen. und das ist der transitus regularis. irregularis besteht nur in halbe{n[?]} tertiæ steigt d«ies»er auf «oder ab» so kan eine falsche an statt der guten gelten |

Regarding transitus dissonances when the voices move stepwise, one note must be good and the other can be false [i.e. accented and unaccented]. But if the voices move by leap then they must all be good [accented]. When two voices move parallel this must occur in thirds or sixths. This is the transitus regularis [unaccented passing]. Irregularis consists of a half note that fills in a third ascending or descending. This way one [note] can be false instead of good.(37) |

N‹ota› b‹ene› was bey geschwinden Mesuren angeht, geht in langsamen [n]icht an |

N.B. What is possible [regarding transitus notes] in fast tempos is not allowed in slow ones. |

Transitus bestehet nach der Composition in einer tertia, ist[?] entweder regularis oder irregularis. regularis hat die guten noten an ungleichen, irregularis aber die falschen an des[?] orten[?]. et vice versa. hemit‹onium›[?] |

In composition, transitus consists of a third and is either regularis or irregularis. Regularis has the good notes on odd beats, but here the irregularis has false notes, and vice versa. |

{17r} Von dem ordentlichen und natürlichen Gebrauch der dißonanzen in Ligatur. |

Regarding the proper and natural use of ligature dissonances [syncopatio] |

§. 1. Die dissonantzen welche sind 2 4 7 und 9, werden in der Ober und Unter Stim‹m›e ja auch in denen Mittel-Stim‹m›en gebraucht. |

§. 1. Dissonances, which are 2, 4, 7, and 9, are used in the upper, lower, and even in the middle voices. |

§. 2. Alle arten der dissonanzen sind entweder Majores oder minores. |

§. 2. All kinds of dissonances are either major or minor [diminished/augmented or major/minor]. |

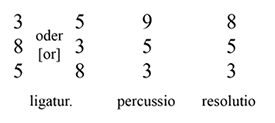

§. 3. Bey dem gebrauch der Dissonantzen ist vornehml‹ich› auf zwey Stim‹m›en Achtung zugeben. Nehml‹ich› auf partem patientem und partem agentem. |

§. 3. In the use of dissonances one must give particular attention to two voices, namely the patient part and the agent part.(38) |

§. 4. So dann ist zu merken des partis patientis Ligatur, percussio u‹nd› resolutio. |

§. 4. The patient part has a ligature [preparation], percussio [dissonance], and resolution. |

{17v} §. 5. Es ist ferner zu merken, daß pars patiens allezeit die Dissonanz ist, sie mag oben unten oder mitten stehen, und dahero bey der Resolution ordentlicher weiße sich allezeit umb einen grad erniedrigen muß, «pars agens aber ordentl‹icher› weiße stille stehet nehml‹ich› bey der repercussion u‹nd› Resolution.» |

§. 5. Moreover, the patient part is always the dissonance, whether it occurs in the upper, lower, or middle voice, and therefore must usually descend by step at the resolution. The agent part usually remains held at the repercussion and resolution.(39) |

§. 6. Weil wir hier nur das erste Fundament zuzeigen haben so merke man, daß die ligutur allezeit so wohl im Trippel- als schlechten Takt in arsi, percussio in thesi u‹nd› resolutio abermahls in arsi geschehen müße. |

§. 6. Because we are only covering the basics, one should note that the preparation must always occur as an upbeat, the percussio as a downbeat, and the resolution again as an upbeat in triple as well as duple meters.(40) |

§. 7. Sollen nun dissonanzen in der Ober Stim‹m›e gebraucht werden, so ist es nöthig daß man 1 solche Noten an {18r} denen §. 6 gezeigten Stellen des Takts ligire, damit sie die percussion außstehen können und hernach 2 umb einen grad entweder per tonum oder p‹er› hemitonium erniedrige. |

§. 7. Should the dissonance be used in the upper voice, it is necessary (1) that one suspend such notes [with a tie] as described in §. 6. so that the percussio may be evident, and afterwards (2) that this note descend by whole tone or semitone. |

§. 8. Die dissonantien müßen an Consonantien ligirt und durch Consonanzien resolvirt werden. oder es müßen vor solchen N‹ota› b‹ene› in eben derselben Stim‹m›e, erstl‹ich› Consonanzen liegen, u‹nd› auf dieselben N‹ota› b‹ene› in eben derselben Stim‹m›e, Consonanzen folgen. |

§. 8. The dissonances must be tied [prepared] as a consonance and resolved as a consonance. N.B. Or [recte: and] this must occur in the same voice, first being prepared as a consonance and following in the same voice as a consonance. |

§. 9. Die Secunda wird niemahl oben oder in der Oberstim‹m›e gebraucht, sondern an deren statt die Nona, so erfordert {18v} es wohl die Ord[n]ung daß wir von der nona anfangen. |

§. 9. The second is never used in an upper voice, but in its place the ninth is required. According to the [descending] ordering we will begin with the ninth. |

1. Vor der None kan entweder die 3. oder 5; niemahls aber die 8. liegen. |

1. The ninth is prepared either by a third or fifth, never by an octave. |

2. die None wird alle mahl in die 8ve resolviert. «wobey die Melodie allemahl p‹er› tonum absteigen muß ‹nicht› p‹er› |

2. The ninth always resolves to the octave, whereby the melody [containing the ninth] must always descend by whole tone and not by semitone.(41) |

§. 10. die qvarte wird oben also gebraucht. |

§. 10. The fourth is used in an upper voice.(42) |

1. Vor der qvarte kan 3. 5. und octave liegen. |

1. The fourth can be prepared by a third, fifth, or octave. |

2. wird alle mahl in 3 resolvirt; doch kan die Melodie so wohl p‹er› tonum als p‹er› hemitonium absteigen. |

2. [The fourth] always resolves to a third, but the melody can descend by whole tone or by semitone. |

{19r} §. 11. die 7 wird oben folgender gestalt angewendet. |

§. 11. The seventh is used in an upper voice as follows: |

1. vor der Septime kan 3. 5 u‹nd› 8ve liegen. |

1. The seventh can be prepared by an third, fifth, and octave. |

2. Wird alle mahl ordentlich in die Sext resolvirt, dabey die Melodie so wohl umb einen ton als hemitonium fallen kan. |

2. [The seventh] is usually resolved to the sixth, whereby the melody may descend by whole tone or by semitone. |

§. 12. dieses ist der ordentliche und natürliche Zustand der partis patientis in der Oberstim‹m›e, wenn wie wir hier zum Grund gesezet der Bass als Aggressor und beleidiger solches Theil unter währender per-{19v}-cussion hartnäkigt stille stehet. |

§. 12. This is the proper and natural behavior of the patient part in the upper voice when we set a foundational bass voice as the aggressor or the instigator, which holds stubbornly during the percussio [dissonance]. |

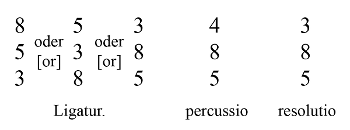

§. 13. Nun wollen wir es gerad umb kehren, und den Bass zur parte patiente den Discant aber zur parte agente machen. da sich denn der erste erniedrigen muß, und der andere als sein Offensor stille stehet, so lange die percussio u‹nd› Resolution wäret. |

§. 13. Now we wish to reverse it, making the bass into the patient part and the discant into the agent part. Here the former must descend and the latter, the offender, remains held through the percussio and resolution. |

§. 14. Die None wird nun im Basse gar nicht gebraucht sondern die Secunde. dahero wir davon den Anfang machen. |

§. 14. The ninth is never used in the bass, but instead the second. Thus, we begin with this. |

1. Vor der Secunde kan entweder die 3 oder 8ve liegen niemahls die 5te |

1. The second can be prepared by the third or octave, never by the fifth. |

2. wird allemahl in die {20r} 3. resolvirt mit dem Accompagnement der Sexte. dabey sich der Bass so wohl p‹er› tonum als per hemitonium erniedrigen |

2. [The second] is always resolved to the third, accompanied by a sixth, whereby the bass may descend both by whole tone and semitone. |

§. 15. Die qvarte wird im Basse folgender gestalt gebraucht. |

§. 15. The fourth is used in the bass as follows. |

1. die qvarte wird unten an die 3. 5. u‹nd› auch wohl 8ve gebunden |

1. The fourth is tied below with the third, fifth, and even the octave. |

2. Sie wird in die 5te resolvirt dabey sich der baß so wohl umb einen ton als umb ein hemitonium erniedrigen kan. |

2. The fourth resolves to the fifth, whereby the bass may descend by a whole tone and a semitone. |

{20v} §. 16. Die Septime kan ordentlicher weiße unten so wenig gebraucht werden, als die secunde oben. Denn wie die Secunde nicht ordentlich in Unisonum gehen und sich erniedrigen kan, also kan sich hier der Bass nicht in die 8vam erniedrigen. dahero er beym dem untern Gebrauch der Septimen gar stille stehen bleibet und da hat man folgende Gänge sonderl‹ich› zu merken. |

§. 16. The seventh can properly be used as infrequently in the lower voice as the second can in an upper voice. For, just as the second cannot properly descend to a unison, neither can the bass descend to the octave. Thus, it [the bass] remains held when a seventh is used in the lower voice. One should take note of the following passage: |

oder bey der 7 majore |

Or with the major seventh [resolving up]: |

alles bey liegenden Basse. {21r} |

Everything [in the above examples] is with a held bass. |

§. 17. Obgleich bey vielstimigen Sachen die resolutio Septimæ in Octavam noch möchte zu gebrauchen u‹nd› zu entschuldigen seyn; so ist doch dieser Gang und resolution sehr rar. |

§. 17. However, in many-voiced textures the resolution of the seventh to the octave is possible and can be admitted, but this phenomenon and resolution are very rare. |

§. 18. Von dem Gebrauch der Septimæ diminutæ und anderer[?] ist noch nicht Zeit zu reden. nun wollen wir sehen wie die Dissonanzen ordentlich in der Mitte gebraucht werden. |

§. 18. Time does not permit the discussion of the use of the diminished seventh and other [diminished intervals?]. Now we would like to see how dissonances can be properly used in the middle voices. |

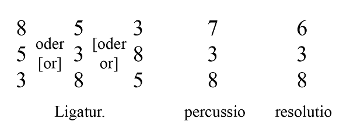

§. 19. Wenn die dritte chorda modi also ‹…› accompagnirt ist u‹nd› folgt die qvinta im‹m›edi-{21v}-ate drauf, so kan der Alt in der qvarte hangen bleiben, die sich wie ordentl‹ich› in die 3. resolvirt. |

§. 19. When the [interval of a] third [over the bass] is accompanied and the [interval of a] fifth [over the bass] follows immediately after, the alto can remain held with a fourth [as in the first example below], which properly resolves to the third.(43) |

Mit stärkerer Speiße wollen wir unsern liebhaber jetzt nicht beschweren. |

We do not wish to trouble our reader with more difficult passages [literally: stronger dishes]. |

§. 20. Auß dem was bißhero gesagt worden, wird mit leichter Müh zu ersehen seyn, daß 1. wie schon gesagt Sonus patiens allezeit der dissonirende Sonus sey, und daß die andern welche ihm zu nahe trette unter ein ander einig seyn. Z‹um› E‹xempel› das Complot der 2 u‹nd› qvarte ist nichts andern als die trias harmonica {22r} des Soni so nach dem beleidigten per gradum toni vel hemitonii folget. und diese en regard der unten gebundenen Stim‹m›e. welches auch erscheinet an der unten gebunden Septima als welche durch die triadem des im‹m›ediate unter dem gebundenen Sono liegenden Toni vel hemitoni[i], beleidigt wird. und weil sie sich ordentl‹icher› weiß zu solchen schlägt nicht so passable als die obere ist, welche sich von ihnen entfernet. In ansehung der ligirten u‹nd› percutirten oberstim‹m›e macht der Bass auch seine Factiones also ist die percutirte Septima von nichts anders als der Triade harmonica {22v} des im‹m›ediate über ihr liegenden Toni angegriffen. Und die Qvarte ob sie gleich die tertie ihr ordentl‹ich› nichts anzuhaben scheint, wird doch von der 8 u‹nd› 5 oder der alten griechischen triade harmonica zum weichen gezwungen. wie wohl man auch Gänge findet daß es die tertia mit ihr waget. Die None hat Triadem des im‹m›ediate unter ihr liegenden Toni. Conjungirt sich aber wie die Septime mit denen Feinden, doch mit mehrer raison, weil nehml‹ich› ein profitabler frirde {friede} ordentlich drauf folgt, der in einer Syzygia perfecta bestehet {23r} |

§. 20. From what has been said up to this point, it will be easy to understand that (1) the above-mentioned patient part is always the dissonant pitch, and that the other [parts] that venture too close to it are themselves unified [understood as a group]. For example, the composite of the second and fourth is nothing other than the trias harmonica of the pitch that follows after the semitone descent of the lower voice. The same applies to the seventh that is tied below [subsyncopatio], which is syncopated by the trias of the note just below the tied note and because it [the lower note] is usually not so suitable to being syncopated as the upper note, from which it [the lower note] distances itself. Regarding the tied and syncopated upper voice, the bass also makes its faction [forms a composite with the other pitches], such that what is grabbed is nothing other than the trias harmonica of the tone immediately above [the 7-subsyncopatio]. And the fourth, although it may seem unrelated to the third, is nevertheless forced to move by the octave and fifth or the old Greek trias harmonica. One also finds passages where the third dares to be present with the fourth. The ninth has the trias harmonica of the tone directly below it, but, like the seventh [subsyncopatio] makes company with the enemies [foreign tones], but with good reason, since a profitable peace follows afterwards consisting of the perfect concord.(44) |

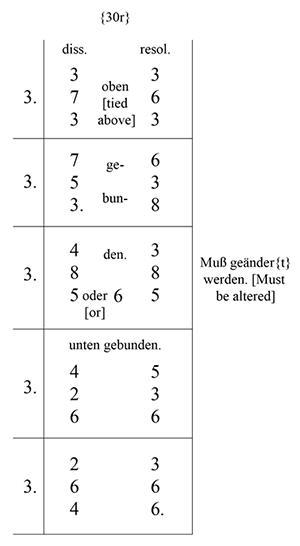

{§.} 21. So man nun auf diese weiße der Dissonantzen sich bedienen will, so ist es nöthig daß man die melodie darnach aggiustire. Z‹um› E‹xempel› in regard der Oberstim‹m›e sind bey folgenden Gängen der Melodie zu gebrauchen |

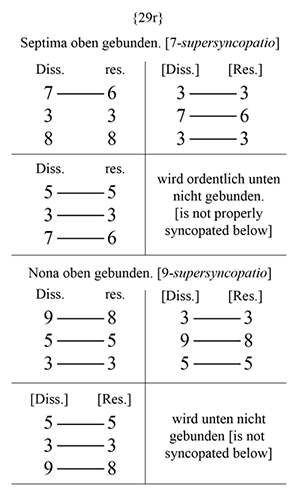

§. 21. In order that one can employ dissonances in the manner described above [in chorales], it is necessary that the melody be adjusted. For example, regarding the top voice, the following passages are available for use: |

{23v} In regard der unterstim‹m›e sind bey folgenden Gänger der Melodie die dissonanzen zu gebrauchen, wie etwa folget. |

Regarding the lower voice, dissonances may be used in the following types of melodic passages: |

beyde arten müßen nun zierlich verwechßelt werden. |

Both types [sub- and supersyncopatio] must now be used artfully in alternation. |

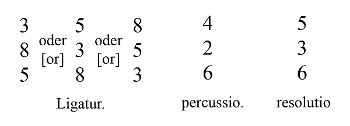

§. 22. Noch etwas wenig von der Continuation solcher Gänge kan hier mit angehänget werden. diese geschieht nicht füglicher, als wenn man an statt der 3 u‹nd› 6 maj‹orum› u‹nd› des hemitonii {24r} darein sich die Consonanzen zum Theil resolviren die 3. u‹nd› Sexten minores oder man lest die partem patientem da sie sich umb ein hemitonium erniedrigen soll, umb ein ganzen thon herunter doch nach beschaffenheitt des Modi. die lezte resolution aber muß alzeit major sey[n], oder zu lezt muß ich nur ein hemitonium fallen z‹um› E‹xempel› in der Oberstim‹m›e [m]it 7 |

§. 22. We can add yet a few remarks regarding the continuation [sequential use] of such passages. This cannot happen better than when, instead of the third, major sixth, and semitone, the consonances also at times resolve to minor thirds and minor sixths [in a suspension chain]. Or one allows the patient part that should descend by semitone instead descend by whole tone, but still in accordance with the key. But the last resolution must always be [to a] major [sixth], which is to say, I need only descend a semitone. For example, in the upper voice with a seventh: |

N‹ota› b‹ene› wenn der Bass umb ein hemitonium fält, steht auf solten {solchen?} lezten Sono die qvinte [n]icht gar zu wohl; es seyn dem {denn} major beym changement oder Schluß. |

N.B. When the bass descends by semitone, it is not very good to have the fifth over the last note [i.e. note of resolution] unless it is a perfect fifth in a change of key or cadence. |

In der unter stime mit 2 u‹nd› 4. |

A second and fourth in the lower voice. |

{24v} N‹ota› b‹ene› Die mit ‹ |

N.B. Notes that have a sharp [or a natural in flat keys] should not be repeated [doubled] with an octave. |

§. 23. Nun noch etwas weniges von vermischten Continuationib‹us›. da wechßelt man und bindet bald 9 bald 4 bald 2[?] Z‹um› E‹xempel› |

§. 23. Now yet a little something regarding mixed continuations [sequences]. Here one changes [the type of dissonance] and ties a ninth, then a fourth, then a second. For example: |

Unzehlich andere Arten werden durch Übung u‹nd› fleiß schon zum vorschein kom‹m›en. |

Innumerable other types [of dissonant progressions] will come to light through practice and diligence. |

{25r} ad §. 19. In gleichen wenn die discant Stim‹m›e mit dem Bass in 3. liegt. können statt der mit der 5[?]te accompagn‹irten/enden[?]› folgenden 8[?]ten Note Modi, der Discant u‹nd› Alt dieser in 4 u‹nd› jener in 6te hangen bleiben, und sich in 3 u‹nd› 5 resolviren. Z‹um› E‹xempel› |

Addendum to §. 19. In particular, when the discant voice makes a third above the bass, instead of accompanying the following first degree in the bass with the interval of a fifth, the discant and alto can hold over with a 6 and 4 respectively, resolving to 5 and 3. For example: |

Es bestehet alles in einer verwechßelung der Stim‹m›en welche sich in Reguln [n]icht lest ein schließen. Z‹um› E‹xempel› [m]it der None u‹nd› anderen dissonanzen in mittelstim‹m›en. |

Everything consists of an inversion of voices [double counterpoint], which cannot be accounted for in rules. For example, with the ninth and other dissonances in middle voices. |

{25v} Hat man nun oben behalten, daß alle dissonanzen müßen an Consonanzen gebunden und durch solche gelöset werden so kan man nach belieben operiren, Zum› [Exempel] |

It was stated above that all dissonances must be tied and resolved as consonances, and in this way one can proceed freely, for example: |

{26r} §. Nunmehro mochte es zeit seyn an die Accompag‹nements› zu denken welche bey der Resolution nicht liegen bleiben sondern fortgehen. Es ist noch Zeit |

§. We would now like to consider an accompaniment [i.e., agent voice] that does not hold during the resolution, but moves to a different note. There is yet time. [?](48) |

Ac‹c›ompagnement. |

Accompaniment |

{29v} Die unten gebundenen Dissonanzen sind bey folgenden Gänger der Melodie wohl zu brauchen |

The subsyncopatio dissonances can be used well by the following melodic motions. |

Derek Remeš

Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Arsenalstrasse 28a

6010 Kriens

Switzerland

derek.remes@hslu.ch

Works Cited

Bert, Siegmund. 2016. “Stölzel, Gottfried Heinrich.” MGG Online. https://www.mgg-online.com/mgg/stable/48705.

Buchner, Hans. 1974. Sämtliche Orgelwerke. Edited by Jost Harro Schmidt. 2 vols. Das Erbe deutscher Musik, vol. 54. H. Hitolff.

Burns, Lori. 1995. Bach’s Modal Chorales. Pendragon.

Campion, Thomas. (ca. 1612–14) 2003. A New Way of Making Fowre Parts in Counterpoint. Edited by Christopher R. Wilson. Ashgate.

Diergarten, Felix. 2017. “‘Aut propter devotionem, aut propter sonorositatem’: Compositional Design of Late Fifteenth-Century Elevation Motets in Perspective.” Journal of the Alamire Foundation 9: 61–88.

Hennenberg, F. 2001. “Stölzel [Stöltzel, Stözl], Gottfried Heinrich.” Grove Music Online. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000026841.

Heinichen, Johann David. (1711) 2012. Neu erfundene und Gründliche Anweisung. Translated by Benedikt Brillmayer and Casey Mongoven. Pendragon Press.

—————. 1728. Der General-Bass in der Composition. Christoph Matthai.

Herbst, Johann Andreas. 1643. Musica poëtica. Jeremiae Dümler.

Leaver, Robin A. and Derek Remeš. 2018. “J. S. Bach’s Chorale-Based Pedagogy: Origins and Continuity.” BACH: Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute 48 (2) and 49 (1): 116–50.

Marshall, Robert L. 1970. “How J. S. Bach Composed Four-Part Chorales.” The Musical Quarterly 56: 198–220.

McCormick, Susan Rebecca. 2015.“Johann Christian Kittel and the Long Overlooked Multiple Bass Chorale Tradition.” PhD diss., Queen’s University Belfast.

Müller-Blattau, Josef, ed. (1963) 1973. Die Kompositionslehre Heinrich Schützens in der Fassung seines Schülers Christoph Bernhard. Kassel: Bärenreiter. Translated by Walther Hilse as “The Treatises of Christoph Bernhard.” In The Music Forum, vol. 3, edited by William J. Mitchell and Felix Salzer, 1–196. Columbia University Press.

Niedt, Friedrich Erhard. (1700–17) 1989. Musicalische Handleitung. 3 vols. Vol. 1 reissued 1710. Vol. 2 reissued in 1721, edited by Johann Mattheson. Vol. 3 published posthumously in 1717, edited by Mattheson. Translated as: F. E. Niedt, The Musical Guide Parts I–III (1700–21). Edited by Pamela Poulin and Irmgard Taylor. Oxford University Press.

Remeš, Derek. 2017a. “J. S. Bach’s Chorales: Reconstructing Eighteenth-Century German Figured-Bass Pedagogy in Light of a New Source.” Theory and Practice 42: 29–53.

—————. 2017b. “Chorales in J. S. Bach’s Pedagogy: Recasting the First-Year Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum in Light of a New Source.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 31: 65–92.

—————. 2018. “Teaching Figured-Bass with Keyboard Chorales and C. P. E. Bach’s Neue Melodien zu einigen Liedern des neuen Hamburgischen Gesangbuchs (1787).” BACH: Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute 49 (2): 205–26.

Remeš, Derek, ed. 2019a. Realizing Thoroughbass Chorales in the Circle of J. S. Bach. 2 vols. Wayne Leupold Editions.

Remeš, Derek. 2019b. “Four Steps Toward Parnassus: Johann David Heinichen’s Method of Keyboard Improvisation as a Model of Baroque Compositional Pedagogy.” Eighteenth-Century Music 16 (2): 133–54.

—————. 2019c. “New Sources and Old Methods: Reconstructing the Theoretical Paratext of J. S. Bach’s Pedagogy.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie. 16 (2): 51–94.

—————. 2019d. “Thoroughbass Pedagogy Near J. S. Bach: Translations of Four New Manuscript Sources.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie. 16 (2): 95–165.

—————. 2020a. “Thoroughbass, Chorale, and Fugue: Teaching the Craft of Composition in J. S. Bach’s Circle.” PhD diss., Hochschule für Musik Freiburg (Germany).

—————. 2020b. “J. S. Bach and the Choralbuch Style of Harmonization: A New Pedagogical Paradigm.” In Rethinking Bach, edited by Bettina Varwig. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Forthcoming.

Sarath, Ed, David Myers, and Patricia Campbell. 2014. “Transforming Music Study from its Foundations: A Manifesto for Progressive Change in Undergraduate Preparation of Music Majors.” The College Music Society. https://www.music.org/pdf/pubs/tfumm/TFUMM.pdf.

Schonsleder, Wolfgang. (1631) 1684. Architectonice musices universalis. 2nd ed. Edler.

Schubert, Peter. 2018. “Thomas Campion’s ‘Chordal Counterpoint’ and Tallis’s Famous Forty-Part Motet.” Music Theory Online 24 (1). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.18.24.1/mto.18.24.1.schubert.html

Stölzel, G. H. ca. 1719–49. Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht. D-B, Mus.ms.theor. 839.

—————. 1725. Practischer Beweiß, wie aus einem […] Canone perpetuo […] viel und mancherley […] Canones perpetui à 4 zu machen seyn. D-B; Dr. o.O.

Telemann, G. P. 1730. Fast allgemeines Evangelisch-Musicalisches Lieder-Buch. Stromer.

Vogt, Florian. 2018. Die “Anleitung zur musikalischen Setzkunst” von Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel (1690–1749): Edition und Kommentar. Bockel Verlag.

Walther, Johann Gottfried. (1708) 1955. Praecepta der Musicalischen Composition. Edited by Peter Benary. Breitkopf & Härtel.

Werckmeister, Andreas. 1702. Harmonologia Musica oder Kurtze Anleitung Zur Musicalischen Composition. Calvisius.

Wiedeburg, Michael J. F. 1765–75. Der sich selbst informirende Clavierspieler. 3 vols. Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses.

Wolff, Christoph, ed. 1998. The New Bach Reader. Norton.

Zahn, Johannes. (1889–93) 1963. Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder aus den Quellen geschöpft und mitgeteilt. 6 vols. Olms.

Footnotes

1. The manifesto states that, “both the effectiveness of [four-part, Bach-style part writing] and the narrow horizons toward which it aims need to be carefully assessed from a contemporary, creative vantage point” (Sarath, Myers, and Campbell 2014, 12).

Return to text

2. For instance, there was a panel at the 2019 meeting of the Society for Music Theory titled “Corralling the Chorale: Moving Away From SATB Writing in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum.”

Return to text

3. I have attempted this in Remeš 2017b.

Return to text

4. Earlier examples, like Hans Buchner’s early fifteenth-century description of how to compose a countertenor-bassus below a chant melody, must be excluded, since these methods belong to modal practice and do not involve a bass line in the modern sense (Buchner 1974, 1:17–27). See also Remeš 2020a, 203–210.

Return to text

5. Florian Vogt’s German-language edition of another one of Stölzel’s treatises, the Anleitung zur musikalischen Setzkunst, also includes an overview of folios 1–16 (i.e., about half) of the Kurzer und gründlicher Unterricht (Vogt 2018, 126–54). Vogt’s excellent work piqued my curiosity, such that I wanted to investigate the remainder of Stölzel’s treatise and make it available for English-speaking audiences in its entirety.

Return to text

6. See McCormick 2015, Leaver and Remeš 2018, and Remeš 2017a, 2018, 2019a, 2019c, 2019d, 2020a, and 2020b.

Return to text

7. See Remeš 2019c and 2020a for more on these connections to J. S. Bach.

Return to text