Review of Leslie A. Tilley, Making It Up Together: The Art of Collective Improvisation in Balinese Music and Beyond (The University of Chicago Press, 2019)

Marc Hannaford

KEYWORDS: improvisation, non-western music, Balinese music, interaction, analysis, local theory

Copyright © 2020 Society for Music Theory

[1] Improvisation is a ubiquitous component of music the world over. Scholars have detailed some of its multifarious forms and meanings, demonstrating that the practice of improvisation extends far beyond its hypervisibility in jazz.(1) Tilley’s Making It Up Together offers new and compelling perspectives in this expanding field of improvisation studies, as well as in ethnomusicology (Tilley’s home discipline) and music theory. It excavates improvisatory processes in a musical genre thought to be largely composed and offers a unique examination of intraensemble interaction. The book also proposes a new theory of improvisation applicable to practices beyond the book’s specific case studies, and its discussion of “local theory” suggests that we critically expand the theoretical underpinnings of our disciplines.

[2] Tilley’s two case studies come from Balinese music: (1) reyong norot, where four players, each with two mallets, improvise on a single row of pitched metal gongs as part of gamelan gong keybar; and (2) kendang arja, where two players each improvise on a two-headed drum as part of a gamelan geguntangan ensemble, which accompanies singers and dancers in a style once referred to as “Balinese Opera” (186). Readers may be familiar with these practices from previous explications by Tenzer (2000) and Perlman (2004), among others, who explore intricate interlocking rhythmic and melodic patterns in the music.

[3] Tilley offers many engaging ethnographic accounts throughout Making It Up, the first of which details her “discovery” of improvisation in these gamelan practices. During a brief intermission in one of Tilley’s daily kendang lessons, her teacher and one of his long-time friends—also a drummer—launched into a series of shifting interlocking rhythms that resemble but differ from familiar patterns. “[I]t’s kendang arja,” they explained in response to her queries, “We’re improvising.

Processes of Improvisation and Models

[4] Tilley employs an impressive combination of fieldwork, ethnography, transcription, interdisciplinary research (primarily in jazz studies, music cognition, sociology, and organizational studies), and detailed musical analysis to develop a theory of improvisation that comprises four processes: interpretation, embellishment, recombination, and expansion. Her focus on process over product recalls Goldman’s (2016) theorization of improvisation as “a way of knowing,” a phrase that Tilley also adopts. Interpretation comprises taking minor liberties with given material. Embellishment involves creating distinct variations while maintaining a clear relationship to the underlying structure. Recombination entails reordering known patterns or segments of patterns to various degrees. Finally, expansion denotes extending the conceptual space between given material and the improvisation, thus creating more complex—and eventually independent—relationships.

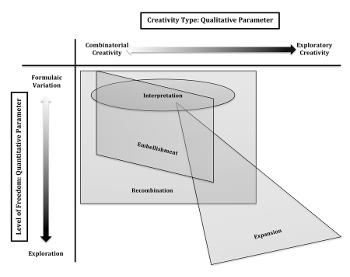

Example 1. Tilley’s Figure 1.13, “Relating Processes of Improvisation to Creativity Type and Level of Freedom”

(click to enlarge)

[5] The conceptual borders of Tilley’s processes overlap, a by-product of developing a model of improvisation intended to apply to many, varied improvisatory practices. This theoretical flexibility aids comparative analysis, but it occasionally leads to confusing theoretical explanation. Readers might experience this confusion most acutely as she situates these four processes using two axes: qualitative and quantitative (42), shown in Example 1.

[6] Tilley’s qualitative axis describes “creativity type,” featuring combinatorial creativity at one end and exploratory creativity at the other. Her quantitative axis traces “levels of freedom,” featuring formulaic variation at one end and exploration at the other. The terminological overlap between these axes—words derived from explore appear on both—requires further clarification. Additionally, the diagramming of her processes as variously shaped, overlapping fields within these axes generates other questions. As Example 1 shows, Tilley’s notion of “expansion” encompasses practices that vary drastically in their degree of quantitative or qualitative exploration, but she does not offer further explanation in her text. Similarly, “recombination” appears as a large field of activity that encompasses contrasting pairs of processual descriptors: formulaic variation that is either combinatory or qualitatively exploratory, and quantitative exploration that is either combinatorial or qualitatively exploratory. Additionally, the process of recombination encompasses all processes of interpretation and embellishment, a claim that is not intuitive to me and receives no attention. The reader is left to imagine and compare the kinds of improvisatory practices that correlate with each of these nodes. Detailed examples of each of these combinations and relations would help clarify the many relationships presented on this summative graph and facilitate the adoption of her model for future work. Luckily, this theoretical opacity does not detract from her detailed analyses.

[7] Tilley’s four improvisatory processes function in tandem with her notion of a “model,” a flexible but indispensable concept that provides the foundation for both improvised practice and analysis. Put simply, models are underlying structures that are interpreted, embellished, recombined, and expanded upon. They also vary in their level of detail, temporal scale, and number of voices. Tilley’s model ranges from “specific motifs [that are] only conservatively variable to more general guidelines of style conventions and aesthetic intentions” (27), a theorization she derives from key work by scholars such as Pressing (his “referent”) (1984) and Arom (his “skeleton”) (1991). Models could be such disparate structures as song and blues forms, scales, chords, sonata form, rhythmic schema, graphic scores, aesthetic frameworks, and general moods or narratives that structure a performance. The conceptual openness of this component of her theory is attractive and suggests applicability across a wide range of improvised music.

[8] Tilley distinguishes between models that are openly discussed and explicitly known, unspoken but consciously known, and unspoken and implicitly known (144). Her categories of explicit and implicit forms of knowing differentiate between instances where practitioners can definitively outline their model and instances where they cannot. Although musicians “know” the model in both cases, the form of this knowledge differs. Models may therefore function on different cognitive and discursive levels, and the analyst/ethnographer must ascertain both the model itself and the ways in which individuals know, learn, and share it. Tilley’s method of discovering models and processes for each of her case studies provides a detailed roadmap for analysts in similar fields: close listening, learning to play, immersion, transcription, and one-to-one interaction. This set of techniques is circular rather than linear: activities in one area continually inform and shape others.

[9] The model in her analysis of reyong norot, for example, is explicitly known but unspoken. It consists of the alternation between a given, primary melodic pitch and its scalar upper neighbor, with deviations from this undulation to idiomatically prepare for the next primary melodic pitch (77). In kendang arja, the model is implicit, unspoken, and multi-voiced. Roughly, it constitutes small cells that employ two kinds of drum strokes (“e” and “T” in Tilley’s analyses) in a pattern of either “eeT” or “eT,” as well as a basic organization of interlocking drum strokes. These pattens are framed by a hierarchical interactive relationship where one player adheres more closely to a fixed pattern of accents while the other improvises with more freedom. Tilley’s description of the process of finding these models and her explanation of the way they function as the basis for improvisation and interaction, as well as her analyses based on these models and processes, are some of the highlights of the book.

[10] This discussion of models furnishes us with frameworks for articulating both the nature of the structures that undergird improvisation and how analysts discover and use them, which are crucial for analytical studies of improvisation of all kinds. An analyst who fails to acknowledge a model’s genesis risks positing it as “given,” rather than a product of the musicians’ field of activity. Additionally, instances where the model is unspoken or implicit risk confirmation bias if an analyst ignores musicians’ perspectives—in other words, ignoring discursive levels makes us more likely to adopt a model that best fits our analytical project, rather than the one actually used by the improvisers.

[11] Finally, Tilley highlights musicians’ multifarious attitudes toward the model. Thus, knowing the model is insufficient, in itself, for analysis: improvisers also possess a genre sensitive “knowledge base” that informs the “allowable distance” from the model, as well as the “toolkit of available techniques” for improvisation (45). This contribution is significant for improvisation studies because it emphasizes that models are embedded in musical cultures and idioms, and that they function relationally. The way an improviser approaches and uses the model is therefore just as consequential as the nature of model itself.

Interaction

[12] Tilley proposes an analytical model for collective improvisation that accounts for the influence of both the model and one’s fellow performers (175). A model’s specificity, flexibility, and realization type, as well as a performer’s knowledge of it, are essential factors for determining the way that the model structures interaction. With respect to relations between performers, Tilley analyzes the character and prevalence of “co-performers’ direct influences on one another” (172). This approach facilitates analysis of multiple modes of interaction, including supportive, agonistic, overlapping, temporally conjunct, and temporally distant relationships. Tilley notes—drawing on Borgo’s notion of emergence (2007, 2016)—that one cannot reduce improvised interaction merely to a sum of individual parts. Similarly, interaction for Tilley is not directly analyzable in terms of improvisers’ individual intentions and explicit cognitive processes, a point she argues with reference to Csikszentmihalyi’s notion of flow (1996, 2014). Rather, in Tilley’s analysis, models and knowledge bases provide “group goals” that help balance control and unpredictability, as well as individual and collective action (153).

[13] Making It Up emphasizes interactions that emerge from players’ interlocking patterns and comparatively subtle variations. Tilley’s focus is on “the overall aesthetic of loose interlocking” (134), as well as on instrumental roles and the processes of interpretation, embellishment, and recombination (expansion plays a less prominent role in her analyses). Thus, her analyses of interaction differ markedly from influential paradigms in jazz studies, such as those by Monson (1996) and Berliner (1994). These scholars describe interaction as a kind of musical conversation mediated by instrumental roles and musicians’ individual approaches and musical personalities; they promote antiphonal structures and relations of similarly between musical phrases as markers of interaction. In reyong norot and kendang arja, however, such dialogic interactions occur rarely, leading to Tilley’s detailed and novel account.

[14] Tilley analyzes a passage in kendang arja, for example, in which two drummers segment and recombine standard patterns while simultaneously avoiding coincidences between their low accents and rhythmically propelling the music toward strong metric markers, an idiomatic feature of the style. Their interactions emerge from their simultaneous negotiations of the model, improvisatory processes, and instrumental roles. The musicians do not interact according to dialogic paradigms; instead, they pay close attention to one another’s musical flow while sharing common aesthetic goals. This work complements those preceding perspectives rather than countering them, and it helps expand our understanding of intraensemble interaction.

[15] As Tilley suggests, her theories of improvisation and interaction could productively apply to music beyond the context from which they emanate. In this regard I would like to see her frameworks applied to improvisation in nineteenth-century Western art music, partimenti traditions, Hindustani music, New Orleans jazz, and various experimental musical practices, among others. Careful comparative analyses, Tilley’s states in her conclusion, “can be illuminative without being reductive; we can find common processes of interaction and improvisation across multiple musical cultures, and these commonalities can actually help us better understand their particulars in each practice” (268).

Theorizing Theory

[16] Tilley’s contributions stem from her conversations with her teachers, fellow performers, and other Balinese musicians, which she calls “local theory” (18). “When musicians discuss their own performances,” she notes, “they do so articulately and in very specific musical detail. Although they may not use the same terminology that I do, [these musicians] are very interested in understanding and debating the aesthetics of a new composition’s structure, or the merits and weakness of a long improvisation” (17). Tilley’s observation contains important implications beyond Balinese music, because it suggests that our disciplines should acknowledge and account for the many theories of music that lie outside of established canons and discursive spheres.

[17] Seriously reckoning with “local theory” represents a vital mode of acknowledging and undermining the implicit (and sometimes explicit) whiteness of the epistemological frames that undergird music theory and ethnomusicology.(2) It thus helps compensate for the kind of “diversity work” that simply replaces traditional objects of analysis with those of “diverse” composers or performers but fails to uproot the theoretical structures at the foundation of our disciplines. Tilley’s book suggests that we must expand the purview of what counts as theory and who counts as a theorist. Doing so, I suggest, helps foster a more engaged music theory, following André’s recent coinage (2018, 193–209), and it makes space for greater epistemological diversity alongside (or in place of) the theories that our disciplines traditionally foreground.(3)

[18] Finally, and crucially, we must consider the dangers and limits of such efforts at epistemological expansion. Tilley adopts “local theory” as part of her argument for comparative analyses, but we should be careful not to adopt only those aspects of local theories that fit most easily within our discipline’s given epistemological frame. Doing so, I argue, reduces “local theories” to conventional frameworks and risks appropriating others’ work for our own professional and personal gain. We should thus consider our discipline’s current limits of recognition and ask what “ways of knowing” and subjectivities our discipline will not accept, as well as how dissolving these limits can expand our spheres of knowledge and scholarly communities. This line of inquiry represents an urgent component of the epistemological boundary-pushing in Tilley’s valuable monograph.

Marc Hannaford

University of Michigan

School of Music, Theatre & Dance

1100 Baits Dr.

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

marchann@umich.edu

Works Cited

André, Naomi. 2018. Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement. University of Illinois Press.

Arom, Simha. 1991. African Polyphony and Polyrhythm: Musical Structure and Methodology. Cambridge University Press.

Berkowitz, Aaron L. 2010. The Improvising Mind: Cognition and Creativity in the Musical Moment. Oxford University Press.

Berliner, Paul F. 1994. Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation. The University of Chicago Press.

Borgo, David. 2007. Sync or Swarm: Improvising Music in a Complex Age. Continuum.

—————. 2016. “The Ghost in the Music, or the Perspective of an Improvising Ant.” In The Oxford Handbook of Critical Improvisation Studies, ed. George E. Lewis and Benjamin Piekut, 91–111. Oxford University Press.

Boyd, Clifton, Catrina Kim, and Alissandra Reed. 2020. “After ‘Reframing Music Theory’: Doing the work.” Keynote address presented at the Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting, online, July.

Brown, Danielle. 2020. “An Open Letter on Racism in Music Studies.” My People Tell Stories (blog). June 12. https://www.mypeopletellstories.com/blog/open-letter.

Butler, Mark J. 2014. Playing with Something that Runs: Technology, Improvisation, and Composition in DJ and Laptop Performance. Oxford University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1996. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. Harper Collins Publishers.

—————. 2014. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology. Springer.

Everett, Yayoi Uno, Philip Ewell, Ellie M. Hisama, and Joseph Straus. 2019. “Reframing Music Theory.” Plenary session presented at the Society for Music Theory Annual Meeting, Columbus, OH, November 7–10.

Ewell, Philip. 2020. “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame.” Music Theory Online 26 (2). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.2/mto.20.26.2.ewell.html.

Goldman, Andrew J. 2016. “Improvisation as a Way of Knowing.” Music Theory Online 22 (4). http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.4/mto.16.22.4.goldman.html.

Gooley, Dana. 2020. Fantasies of Improvisation: Free Playing in Nineteenth-Century Music. Oxford University Press.

Lewis, George E. 2004. “Improvised Music After 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives.” In The Other Side of Nowhere: Jazz, Improvisation, and Communities in Dialogue, ed. Daniel Fischlin and Ajay Heble, 131–62. Wesleyan University Press.

—————. 2013. “Critical Responses to ‘Theorizing Improvisation (Musically).’” Music Theory Online 19 (2). http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.2/mto.13.19.2.lewis.html.

Lewis, George E., and Benjamin Piekut, eds. 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Critical Improvisation Studies. 2 vols. Oxford University Press.

Monson, Ingrid. 1996. Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction. The University of Chicago Press.

Perlman, Marc. 2004. Unplayed Melodies: Javanese Gamelan and the Genesis of Music Theory. University of California Press.

Pressing, Jeff. 1984. “Cognitive Processes in Improvisation.” Advances in Psychology 19 (c): 345–63.

Tenzer, Michael. 2000. Gamelan Gong Kebyar: The Art of Twentieth-century Balinese Music. The University of Chicago Press.

Footnotes

1. See Arom 1991; Berkowitz 2010; Butler 2014; Gooley 2020; Lewis 2004, 2013; Lewis and Piekut 2016.

Return to text

2. Not all “local music theory” is from BIPOC musicians and theorists, however.

Return to text

3. These points stem from the recent calls for serious and sustained anti-discriminatory engagement at the systemic levels of our disciplines, such as the 2019 plenary at the Society for Music Theory’s annual meeting, “Reframing Music Theory” (Everett et al. 2019), the plenary for the 2020 annual meeting for the Music Theory Society of New York State, “After ‘Reframing Music Theory’: Doing the Work” (Boyd, Kim, and Reed 2020), Ewell 2020, and Brown 2020.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2020 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4527