Schoenberg’s Cinematographic Blueprint: A Programmatic Analysis of Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielscene (1929–1930)*

Orit Hilewicz

KEYWORDS: film music, program music, Arnold Schoenberg, music and emotions

ABSTRACT: This study examines Arnold Schoenberg’s only published music for film, Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielscene [Accompaniment to a Film Scene], op. 34 (1929–30). Although not composed for an existing film scene, evidence of Begleitungsmusik’s cinematic aspirations motivate this analysis, which approaches the composition as a cinematographic blueprint: a design (or program) for a scene that at the same time serves as its soundtrack. To examine this proposition, I collaborated with artist and filmmaker Stephen Sewell to create a film scene based on my analysis of the piece, which expresses the global narrative described in its program using rhythmic, textural, and structural strategies. While presenting analysis as film proves remarkably appropriate to this composition, in fact, analytical visualization can contribute to various interpretive approaches, allowing listeners to connect an analytical reading in real time to their experience.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.1.4

Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory

[1] Despite what its title may imply, Schoenberg’s Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielscene [Accompaniment to a Film Scene], op. 34 (1929–30) was not composed for a film, but for concert performance. The work’s subtitle comprises a terse program including three situations: “drohende Gefahr” [Threatening Danger], “Angst” [Fear], and “Katastrophe” [Catastrophe].(1) Yet even when considered as music for a nonexistent film, Begleitungsmusik is a surprising creation by the composer who famously derided films as “the lowest kind of entertainment

[2] This study synthesizes Begleitungsmusik’s programmatic and cinematic background by examining the work as Schoenberg’s blueprint for a film scene. I use the term “blueprint” to express the two ways in which this piece could fulfill its title: as music that accompanies a film scene, and also as a work that provides the basic dramatic foundation for a scene that Begleitungsmusik could accompany. Like an architectural blueprint that includes information such as proportion, function, and material, Begleitungsmusik provides the framework for a film scene in terms of its proportions and the thematic relationships between its sections. Rhythmic, textural, and structural elements in the piece express the global narrative described in its program using three expressive strategies: the composition’s theme and variations form, topics, and rhythmic imitation of a body expressing fear.

[3] Schoenberg’s relation to films was more complex than his disdainful remarks above suggest. In fact, he appreciated the medium’s artistic potential at least as much as he abhorred the film industry in general, and indeed the former sentiment seems to have generated the latter.(3) Indeed, analyzing Begleitungsmusik can illuminate Schoenberg’s approach to film music, if only for evidence of the composer’s concurrent fascination with the medium, a fascination that led Sabine Feisst to produce a comprehensive study of Schoenberg’s multifarious connections with the German and American film industries (1999). In her article, Feisst adduces multiple pieces of evidence to argue for Schoenberg’s genuine interest in the medium; in particular, she challenges the widely held view that Schoenberg was unrealistic in his botched negotiations with MGM Studios for the position of studio composer in the popular 1937 film The Good Earth.(4) Schoenberg was never hired to compose a film score. Begleitungsmusik is Schoenberg’s only piece of film music, and as such it should be examined in light of his statements on the genre.

[4] To examine my proposition that Begleitungsmusik is a cinematic blueprint, I collaborated with artist and filmmaker Stephen Sewell to create a film scene based on my analysis of the piece.(5) The scene is the product of analytical as well as creative work. For example, when designing the film scene’s dramatic unfolding and cinematic rhythm (created by editorial cuts and scene changes), I relied on the composition’s structure and proportions. The scene is a montage of brief fragments from contemporaneous films that express the program’s threatening danger, fear, and catastrophe.(6) Therefore, the film is the product of an analytical activity that not only comments on Schoenberg’s composition, but also expresses it creatively.(7)

“Music to no film”

[5] Published accounts and archival sources shed some light on Schoenberg’s motivations for composing Begleitungsmusik. Heinrichshofen Verlag, which used to publish score compilations of incidental music for silent film screenings, commissioned the piece for a jubilee series celebrating the first appearance of talking films.(8) Adorno and Eisler mention the piece as an exemplar of film music that depicts the three themes in its program, since it successfully overcomes the challenges that commercial film music often fails to overcome: creating dramatic interest without falling into cliché, while at the same time retaining musical complexity. New music, they contend, more effectively avoids film music’s potential pitfalls, and Begleitungsmusik as a twelve-tone work communicates its program especially forcefully (see Adorno and Eisler 1947, 24 and Eisler 1941, 591–92).

[6] Letters by Alban Berg and Otto Klemperer (who conducted Begleitungsmusik’s official premiere),(9) and Schoenberg’s reply to Klemperer, show that even if Schoenberg did not compose the piece for a film, he considered the possibility of creating a film to accompany Begleitungsmusik in concert. In a letter from May 18th, 1930, shortly after the piece was published, Alban Berg wrote to Schoenberg:

How magnificent for you! Once again a work is completed: the music for a film scene. I have it already, of course, and—after having studied it briefly—I am excited. It is obviously a complete artwork in itself without a film, however it would have been wonderful if you made a film for this piece to be synchronized with (or whatever it is called!). Such an undertaking, if you have any desire to do so, should be possible to accomplish quite easily in Berlin!(10)

[7] While I have found no indication that Schoenberg considered Berg’s idea seriously, Otto Klemperer seems to have had a more concrete plan, as is made clear in his 1930 proposal to make a film for Begleitungsmusik: “I have received the film music. I believe it will have an effect even as a concert piece. Do you think it is possible that an artist (perhaps Moholy) could create an abstract film for your music, to show at the concert with your piece? Or is that against your will?”(11) Schoenberg’s reply implies that he has already been thinking about this possibility:

I find your suggestion about the abstract film, after thinking it over and over, very tempting indeed, since it solves the problem of this “music to no film.” Only one thing, the horror of the Berlin staging of my two stage works, the abomination which was here committed because of lack of faith, missing talent, ignorance, and thoughtlessness and which has damaged my works very deeply in spite of the musical accomplishments, this horror is still making me shake all over too much, so that I must be very cautious. [. . . ] There seems to be only one way: that Mr. Moholy works on the film together with me (in that case there is at least one participant who can think of something). But perhaps that can be done? (Feisst 1999, 98)

[8] Schoenberg presumably composed Begleitungsmusik for the concert stage, even though he notably does not clarify this point to Klemperer. Yet he acknowledged the conundrum of a concert piece entitled “Accompaniment to a Film Scene.” His initial consent to Klemperer’s suggestion of a film for the piece, contingent upon Schoenberg’s approval and direction of the cinematic creation, shows that the composer was concerned with the film’s capacity to represent, or misrepresent, his work.(12)

[9] Further indication that Schoenberg was interested in film music around the time he composed Begleitungsmusik is provided by Walter Bailey, who produces a follow-up letter Schoenberg received from the German Association of Film Composers in November 1929, in which the Association responded to the composer’s request by offering to answer any questions he may have had about “talking pictures” (1984, 21–22). Without any other preserved correspondence on this matter, it is not known what questions Schoenberg posed to the association and whether they were eventually answered.

Creating a Film

[10] Over the years, few filmmakers attempted to use Begleitungsmusik as a soundtrack and realize its potential as film music. The most well-known example, by filmmaker duo Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, is entitled Einleitung zu Arnold Schönbergs Begleitmusik zu einer Lichtspielscene (Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene, 1972). It starts with an introduction to the composer and the piece, in which the narrator reads Schoenberg’s letters to Wassily Kandinsky from the early 1920s that condemn the painter’s anti-Semitic views. Begleitungsmusik is then played uninterrupted from beginning to end, accompanied by video images of WWII aircraft bombers and other war scenes. Viewers are to understand, then, that Begleitungsmusik’s program (like that of the piano concerto) is autobiographical, expressing Schoenberg’s concerns about the rise of antisemitism in Germany.

[11] When considering Schoenberg’s views on programmatic music, however, one doubts that he would limit his work to such specific interpretation. This is demonstrated, for example, in the famous letter he wrote Gustav Mahler, in which Schoenberg reflects on his impressions of Mahler’s Third Symphony after hearing it for the first time:

It was revealed to me as a stretch of wild and secret country, with eerie chasms and abysses neighboured by sunlit, smiling meadows, haunts of idyllic repose. I felt it as an event of nature, which after scourging us with its terrors puts a rainbow in the sky. What does it matter that what I was told afterwards of your ‘programme’ did not seem to correspond altogether with what I had felt? Whether I am a good or a bad indicator of the feelings an experience arouses in me is not the point. Must I have a correct understanding of what I have lived and felt? And I believe I felt your symphony. I shared in the battling for illusion; I suffered the pangs of disillusionment; I saw the forces of evil and good wrestling with each other; I saw a man in torment struggling towards inward harmony; I divined a personality, a drama, and truthfulness, the most uncompromising truthfulness. . . (Bailey 1984, 160; Schoenberg’s emphasis)

For Schoenberg, the essence of a work’s program is communicated to listeners not through a written text, but in performance. Schoenberg’s writings reveal that he considered the true poetic meaning of a text or a program as transmuted into the musical setting—and perceived by listeners—regardless of the composer’s intention. Therefore, as Schoenberg makes clear, a written text is not necessary for understanding a programmatic work’s poetic meaning, which is already embodied in the composition:

I had composed many of my songs straight through to the end without troubling myself in the slightest about the continuation of the poetic events, without even looking back to see just what was the real poetic content of my song. It then turned out, to my greatest astonishment, that I had never done greater justice to the poem than when, guided by my first direct contact with the sound of the beginning, I divined everything that obviously had to follow this first sound with inevitability. (Schoenberg 1975, 144)

More importantly, for Schoenberg, the musical expression of poetic meaning overrides the composer’s original motivations:

One has to hold to what a work of art intends to offer, and not to what is merely its intrinsic cause. Furthermore, in all music composed to poetry, the exactitude of the reproduction of events is as irrelevant to the artistic value as is the resemblance of a portrait to its model; after all, no one can check on this resemblance any longer after a hundred years, while the artistic effect still remains. (145)

In these remarks Schoenberg portrays a transformation from poetry to music as a process that takes place in a distinctly musical realm: Schoenberg set the text aside when he was working on the musical setting and concentrated on developing his musical ideas (which “had to follow this first sound with inevitability”), indeed, to such an extent that he was surprised at how closely his final setting reflected the meaning of the poem. His comments to Mahler from the perspective of a listener and his decidedly free approach to text setting as a composer imply that the two activities—composing and listening—express different, but related, understandings of a work’s poetic or dramatic content.

[12] While the threat of rising antisemitism in Europe may well have been on Schoenberg’s mind when he composed Begleitungsmusik, and although the piece could certainly support this particular interpretation, assigning such a specific narrative for the work would disagree with Schoenberg’s ideas on musical meaning in programmatic music. Therefore, we chose to present the composition’s themes abstractly. First conceived as an analytical tool, our film became a supplement that enhances analysis and expresses the composition’s dramatic structure.

Begleitungsmusik as a Blueprint

[13] Both Sabine Feisst and David Neumeyer interpret Begleitungsmusik as a succession of three cues in the manner of stock music for silent films. Yet this interpretation is complicated by the fact that the cues are not explicitly marked in the score and listening does not immediately suggest a clear starting point for each. The piece, then, not only affords some interpretive freedom but also encourages listeners to become filmmakers of sorts and imagine the scene that it might express.(13)

[14] While interpretive multiplicity can be exciting for an analyst, it also makes using Begleitungsmusik as a soundtrack difficult. In addition, ambiguity might be understood as supporting Hush’s statement that the piece was never meant to be used in film. Nonetheless, some aspects of the piece suggest that Schoenberg aimed to incorporate contemporary film music conventions as well as his own ideas about the sorts of compositional strategies that were appropriate for film music. Begleitungsmusik was composed in 1929–1930, when Schoenberg’s twelve-tone style was already underway, and his works from the time share structural, textural, and motivic features.(14) In this piece, Schoenberg departs from his characteristic practice in two respects that are revealing when considered in the context of its program. First, he diverges from his habit of using hexachordal combinatoriality as the work’s dominant structuring principle; in Begleitungsmusik, inversion around the first note is of equal significance.(15) Second, Schoenberg uses an unusually broad array of series forms in the piece—all twelve transpositions and inversions—juxtaposing closely related series forms, or alternatively distant series forms, at programmatically meaningful moments in the work. In the following paragraphs, I discuss the significance of each divergence.

[15] Hexachordal combinatoriality and inversion around the first note allow the greatest invariance between Begleitungsmusik’s series forms: combinatoriality leads to hexachordal invariance, and inversion leads to five invariant pitch classes between counterpart hexachords. Begleitungsmusik is one of a handful of Schoenberg works where the inversion that keeps only some subset of the hexachord invariant has structural importance; other compositions include the Suite for Piano, op. 25 and the Woodwind Quintet, op. 26.(16) Inversion around the first note is a dominating transformation also in the Violin Concerto, op. 36, relating between the first and second themes.(17)

[16] The second divergence from Schoenberg’s compositional habits is the unusually broad array of series forms used in the piece, which includes all twelve transpositions and inversions of the series. Since Schoenberg’s mature style is characterized by combinatoriality and invariance, his works tend to feature a limited number of series forms that are typically arranged in combinatorial areas. In the following analysis, I show that the work’s initial concentration on a limited collection of closely related series forms, and its later broadening of the forms used (while loosening the connection between them), suggest a dramatic shape to the piece and helps in understand it as an expression of its program and a blueprint for a scene.

Interpreting the Program

Example 1. Differing segmentations in three analyses

(click to enlarge)

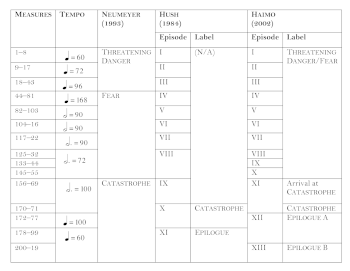

[17] Analysts differ in their interpretations of the way in which Begleitungsmusik expresses its program; their views are consolidated here in Example 1. Neumeyer (1993) divides the piece into three large-scale sections that express the program’s three themes in their order of appearance. Hush takes a different approach and examines the proposition that in Begleitungsmusik Schoenberg intended to explore “the technique of contraction as a means of controlling large-scale structures.”(18) Emphasizing continuity rather than segmentation, Hush avoids dividing the work into large-scale sections, and therefore does not assign programmatic labels to any of Begleitungsmusik’s episodes apart from Catastrophe, which for him is represented in a single episode. (Neumeyer, in contrast, views Catastrophe as a section made of three episodes.) While Hush sidesteps Begleitungsmusik’s programmatic ambiguity by largely refraining from interpreting this aspect of the piece, Haimo explicitly discusses the difficulty of identifying the program in the score.(19) He points out that Begleitungsmusik’s succinct program, as well as its absence of Leitmotifs, differs from the elaborate textural and motivic features that accompany Schoenberg’s earlier programmatic works, and remarks that one could assign Threatening Danger to the beginning of the work, and Catastrophe to its climactic moment because it “sounds like a catastrophe.”(20) Fear, however, has no clear indication in the score. Perhaps, Haimo stipulates, the changing texture and tempo in m. 44 indicate that Fear begins there. Yet he admits that this decision is complicated by other moments in the work that also feature significant temporal and textural changes, such as mm. 18, 27, and 82.

[18] Both Neumeyer’s and Haimo’s interpretations of the program assume that the piece includes three successive cues, each expressing the corresponding theme from the program. While one could hypothetically conceive of other possibilities for representing the musical program that do not segment the piece in this way, there are reasons to consider the work as featuring three distinct and consecutive programmatic sections. First, the three parts of the program feature a dramatic process in which danger leads to a sensation of fear and eventually culminates in catastrophe. This plot, admittedly general and abstract, could be realized in a film scene.(21) Second, Schoenberg’s notes for the piece suggest that he composed it to express such a process. In an early sketch of Begleitungsmusik’s programmatic structure, Schoenberg lists a series of eleven cues that present a detailed narrative with two possible endings—either catastrophe or salvation.(22)

[19] I interpret the programmatic unfolding of Begleitungsmusik similarly to Neumeyer, with Fear starting in m. 44 and Catastrophe in m. 156. Despite my sympathy to Haimo’s hesitation to interpret m. 44 as the start of Fear, this moment presents a starker departure from earlier material compared to mm. 18, 27, and 82 in texture and tempo. Texturally, this moment introduces the first ostinato in the piece, a stark textural change from the preceding. Further support for considering this moment as the start of Fear comes from the grandiose ending of the preceding section: with its molto ritardando, fortissimo dynamics, and the brass sonorities sustained in a long simultaneity for the first time in the piece, the ending features a grand sectional closing. Fear stands out as the only emotion in Begleitungsmusik’s program, a response to a Threatening Danger and a transition to the Catastrophe. One would expect it to be a notable moment in the piece, and m. 44 seems the most likely candidate in representing the starkest contrast to the events that precede it.

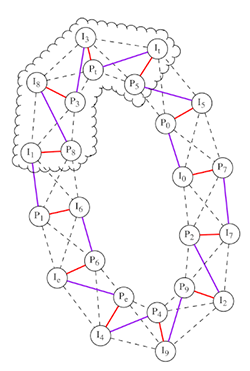

Example 2. The space defined by series forms in Threatening Danger

(click to enlarge)

[20] The two divergences from Schoenberg’s compositional habits that I identified above further support an interpretation in which Fear begins in m. 44. Measures 1–43 exclusively include series forms related by either inversional-hexachordal combinatoriality or inversion around the first note. Moreover, the series forms in mm. 1–43 form a path in the space shown in Example 2. The cloud in the example circumscribes all the series forms used in Threatening Danger. The space as a whole includes all transpositions and inversions of Begleitungsmusik’s series (which are indeed eventually used in the piece), and alternating first-note inversion and combinatoriality—the two transformations dominating Begleitungsmusik—defines a cycle that passes through each of the twenty-four transpositions and inversions exactly once. The ostinato section in mm. 44–59 includes the first series form outside the cloud in Example 2.

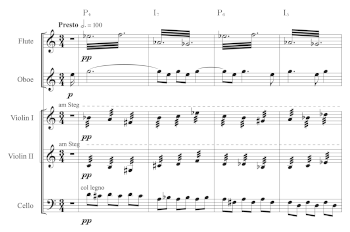

Example 3a. The opening theme in Threatening Danger

(click to enlarge)

Example 3b. The flute foreshadows the section’s ending

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. A score reduction of the stinger in mm. 42–43

(click to enlarge)

[21] The periodic melody that begins Threatening Danger (shown in Example 3a) is the first indication that inversion around the first note is significant in the piece. The melody consists of two four-measure phrases related by inversion. The high degree of invariance and intervallic similarity between the counterpart hexachords of each phrase, as well as their shared rhythmic construction of alternating long and short durations, are obscured by the consequent’s rhythm, dynamics, and articulation; its melody is syncopated and accented, expanding the antecedent’s pitch and dynamic range. In terms of the overall dramatic development, the consequent’s climax in m. 14 (including the preceding leap of a ninth) foreshadows the stinger that ends Threatening Danger in m. 42 (presented here on the top staff of Example 4) not only in its intervallic content and contour, but also in its dynamics. Another connection between these moments is created by the descending figure that follows the consequent’s climax, played by the flute and shown in Example 3b, which presents a truncated version of the stinger’s descending figure shown in lower staff of Example 4.(23)

Example 5. A phrase and its variants in Episode III (Threatening Danger)

(click to enlarge)

[22] The variation in episode III—a lively waltz—demonstrates the way in which inversion and combinatoriality are used for thematic development. Example 5 includes the woodwinds’ phrase in mm. 18–26, its variant in mm. 27–30, and the following variant in mm. 36–39. Like the original theme, the phrase and its two variants feature similar rhythmic profiles. Each of the three phrases contains hexachords taken from two series forms. The first phrase alternates a series form and its inversion around the first note, building on the same relationship from the original theme. The next phrases expand the relationships to include combinatorially related forms.

Example 6. Reduction of the ostinato that opens Fear

(click to enlarge)

[23] The first series transformation outside the complex delineated in Threatening Danger is part of the ostinato in mm. 44–59 and provides structural motivation to consider this moment as beginning a new programmatic section. Example 6 presents a reduction of this passage, in which each measure equals four measures in the score. The example shows that—although the connection between this variation and the preceding is looser—the two transformations that dominate Threatening Danger still govern Fear. Four series forms are realized in this passage, each occupies a stretch of four bars. The two forms in each pair of consecutive four-measure stretches are hexachordally combinatorial, and therefore their opposing hexachords are invariant, a quality highlighted in this excerpt. For instance, the bassoon part in mm. 48–51 is invariant with the four preceding measures, mm. 44–47. In addition, the seam between the two pairs of combinatorial row forms also presents a high degree of invariance, the result of inversion around the first note. Therefore, the two eight-measure segments are closely related as well.

Example 7. Beginning of the buildup towards Catastrophe, mm. 156–159

(click to enlarge)

[24] While there is consensus that Catastrophe includes the climactic moment in mm. 170–71, analysts differ in their interpretations of the exact moment in which the Catastrophe cue starts. The musical structure supports Neumeyer’s and Haimo’s interpretations that the first episode of Catastrophe starts in m. 156: it includes the last series form needed to complete all twelve transpositions and inversions of the series. In the buildup to the climax, whose beginning is shown in Example 7, the oboe sustains the only invariant dyad between the different series forms, creating a continuous thread throughout the passage, which features forms not related by inversion or combinatoriality. But this passage is striking for its rapid intensification and sense of distress created by the change in tempo and the repetitive oscillations of the oboe and flute, which together with the violins’ rising tremolos of whole-tone dyads create a powerful buildup that continues with a ringing crescendo (from pianissimo to triple forte), registral ascents, and timbral intensification with more instruments gradually joining in tremolo until the entire ensemble is heard in a climactic ritardando that brings back the work’s prime series. Indeed, it would be difficult to detach this climactic moment from the preceding buildup when using the piece as a soundtrack, and therefore I followed Haimo and Neumeyer by including mm. 156–169 in Catastrophe. After the climax, the piece ends with a varied repetition of its opening. Structural relationships prove helpful, then, in determining not only the boundary between Threatening Danger and Fear, but also the boundary between Fear and Catastrophe.

[25] Bailey characterized Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto, whose program is somewhat similar to Begleitungsmusik’s, as “more accessible” compared to his String Trio that was composed around the same time (2010, 240). The reason for the concerto’s accessibility, Bailey postulates, is Schoenberg’s consideration of the audience, in this case symphony subscribers (the String Trio was commissioned for a music criticism conference at Harvard University). Indeed, it appears that Schoenberg considered the commission’s purpose also in Begleitungsmusik, whose theme and variations create the series of cues given in Neumeyer’s account. Àine Heneghan points out that Schoenberg differentiated in his writings between theme and variations—which he defined as the juxtaposition of themes linked by “primitive” techniques that are essentially ornamental—and developing variation, which is associated with motivic treatment across larger forms and the Viennese “homophonic style” (2006, 101–102).(24) Heneghan’s analysis of Schoenberg’s Serenade, op. 24 shows that Schoenberg did not refrain from developing variation in his theme and variation forms, yet used it on a smaller scale as one of several linking techniques between variations.(25) Similarly, developing variation does not serve a large-scale function in the theme and variations of Begleitungsmusik. Instead, it is one of several kinds of links used between variations, which also include harmonic, rhythmic, and textural repetition. Schoenberg considers theme and variation characteristic of popular music; that he chose to set his accompaniment music to a film in this form could be indicative of an approach to film music as entertainment.(26)

[26] Indeed, it is common for film music to consist of a succession of unrelated cues that support cuts and scene changes. When such scores are worked into concert pieces, the cues are often morphed into a suite or a medley; Begleitungsmusik could be compared to such concert works, which have been adapted from collections of somewhat independent cues.(27) At the same time, changes in tempo and texture between Begleitungsmusik’s episodes fit the general narrative presented in its program: the first significant acceleration in m. 44, in which the tempo is increased by 175 percent, works well with the programmatic theme. Since the sensation of fear is physically related to accelerated heart rate, it is not surprising that both Neumeyer and Haimo suggest m. 44 as the beginning of Fear.(28) Another significant acceleration, of approximately 140 percent, takes place at the beginning of Catastrophe in m. 156, however its climactic moment features a sudden ritardando (as well as a dynamic peak, making this moment the loudest in the piece). This temporal profile fits a narrative of intensifying fear that develops into a major calamity, in which time appears to stand still.(29) In the film that we made for the piece, the intensification toward Catastrophe is expressed by a quick succession of footage; the accelerated rate of visual change, which arrives at its peak in this moment, parallels the musical intensification, creating a visual effect of impending disaster. In this way Begleitungsmusik’s role in our film is extended from soundtrack to dramatic design.

Begleitungsmusik as a Soundtrack

[27] The film scene that we created for Begleitungsmusik consists of short clips from films released around the time of Begleitungsmusik’s composition.(30) Most of our source films, listed in the Appendix, are commercial features, but there are also two avant-garde films of the type Schoenberg suggested could be made for his composition: Hans Richter’s Ghosts before Breakfast (1928; featuring music by [?] Paul Hindemith and Darius Milhaud) and Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929). In the following I explain how Begleitungsmusik’s program, together with other musical features, informed and shaped the selection of footage and design of the scene.

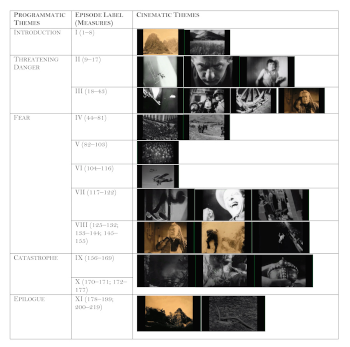

Example 8. The film’s outline

(click to enlarge)

[28] Example 8 includes images of representative shots chosen for each musical episode.(31) The introduction is set to images that present some of the environments featured in the film, such as scenic mountains and expansive fields, showing a calm setting before the appearance of a threatening danger.(32) Threatening Danger, in episode II, is set to images that give the impression of escalating urgency. First, it is expressed as danger within the confines of one’s mind using footage from Un Chien Andalou that shows a man in the midst of a psychotic episode threatening a woman, and then her fearful response. Then, in conjunction with the thematic variation in episode III, the danger is externalized to war and natural threats using footage from most of the films listed in the Appendix. Starting in episode IV, Fear is depicted with footage of panicked masses that eventually become violent and chaotic towards Catastrophe. In the epilogue, the aftermath is shown by returning to the introduction’s original locations and showing them in ruins.

Video Example 1. The setting of Episode II

(click to watch video)

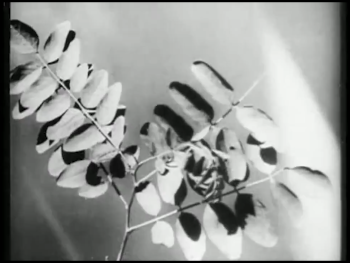

[29] The setting of each of Threatening Danger’s episodes supports its thematic construction. Video Example 1 shows the film’s setting of episode II, which pairs its phrases with footage that depicts escalating danger. The antecedent is accompanied by a dream-like omen: stop-motion footage of an olive tree branch, gradually stripped of its leaves, which then disappears. In the consequent a male character, seemingly in psychotic hallucinations, threatens a woman. Her horrified response—turning around and hiding her face against the wall—happens at the sudden fortissimo on

Video Example 2. The setting of Episode III

(click to watch video)

[30] In its accelerated tempo and triple meter, episode III is an intensified variation of the theme from episode II. The snare drum heard towards the end of the episode introduces a military topic, expressed in the film with images of armored vehicles and weapons that imply impending conflict. The footage for episode III, shown in Video Example 2, reflects the musical fragmentation of the melody’s second part in mm. 27–39 (Example 5) through visual disjunction featuring abrupt cuts between brief clips, some of which are separated from one another with a dark screen that intensifies the sense of disassociation. Some moments are especially notable: starting at 39 seconds into Video Example 2, the shift to dissonant, floating trichords in the strings in mm. 34–35 is paired with a military vessel sailing in fog. In this context, the fog expresses the strings’ airy quality of harmonies. The following military trope in the horns and snare drum, in m. 36, is paired with a moving tank with its aim directed forward at 45 seconds into the example, and the percussive and high ranged syncopations of the piano and flute in mm. 39–40 are expressed visually in the crystal chandeliers starting 50 seconds into the example, presenting a visual parallel to the heard timbres.

Video Example 3. The setting of the ostinato passage that opens Fear

(click to watch video)

[31] The musical relationships in the swift ostinato that opens Fear (shown in Example 6) afford our film with two pulse streams that regulate cuts between scenes. The footage for the sequence is presented here in Video Example 3. The first pulse stream is based on the four-measure units regulated by changing series forms. The second pulse stream originates in measure-long repetitions played by the strings and piano. In the film, the four-measure stream is visualized by scene changes, as material for each four-measure group originates in a different film. To avoid an excessive rate of visual change at this point in the film, we augmented the single measure stream to pairs of measures, which indicate cuts between pieces of footage taken from the same film. Therefore, cuts in the middle of each four-measure group feature footage from a single source, and cuts between consecutive four-measure groups feature footage taken from different films. The overall effect, of masses escaping an unseen threat at different locations simultaneously, connects to the military theme from the preceding episode.

[32] The intensification towards Catastrophe is expressed by quick succession of footage from different films and an accelerated rate of visual change, creating the impression of impending disaster. The footage includes depictions of violence and fear intertwined with frightening and shocking images of a deer carcass and a plague of locusts. The sudden musical ritardando and fortissimo are expressed in the film by a sense of dramatic climax as the motion comes to a halt with images of rising smoke and reverse-motion footage of a dynamite explosion, as if cementing the preceding gush of violence.

Example 9a. A thematic return in Fear

(click to enlarge)

Example 9b. The thematic thread continues in Episode XI, after Catastrophe

(click to enlarge)

Video Example 4. The last thematic variation in measures 178–190

(click to watch video)

Video Example 5. The ending

(click to watch video)

[33] Generally, each of Begleitungsmusik’s programmatic sections has distinct textural and temporal characteristics. Therefore, an effective moment occurs when the heightened sense of drama in the middle of Fear is suspended, in m. 125, by a variation of episode II’s theme from Example 3a. This moment is significant not only for breaking the gradual acceleration that began at the start of this section, but also for establishing a thread from the periodic structure of episode II’s theme, through its sentential variation in episode III (shown in Example 5), and up to m. 125 (shown in Example 9a). This last thematic variation draws from the sentential structure of episode III while inverting episode II’s theme melody. This thematic return is supported in the film by a return to a dramatic thread from Threatening Danger, which is continued and developed in Fear. In m. 125, when the theme returns, the film returns to a scene (not included here) of snowy mountains and a worried-looking woman from the film’s opening, showing—through overlapping cuts between the character and the mountains—that she fears for the safety of two climbers caught in a severe snowstorm.(34) The cinematic narrative continues when another variation of the theme is heard in m. 178, immediately following the climax (Example 9b). This melody is paired in the film with footage that returns to the mountain in the aftermath of the storm, as the mountaintops collapse during the snowstorm, and the lights of hikers are seen, searching for the stranded climbers (Video Example 4). The final scene—a modified repetition of the introduction—shows one of the hikers hiking up to the summit with the sun finally shining (Video Example 5). This conclusion implies that the danger has passed, so that the film as a whole combines the two programmatic alternatives from Schoenberg’s draft mentioned above—catastrophe is followed by salvation.(35)

Analyzing Schoenberg on Film

[34] Whereas other analysts have heard an “extraordinary incongruence” in Begleitungsmusik (Hush 1984, 30), I aimed to show in this analysis that musical continuities and contrasts in Begleitungsmusik can become meaningful when approaching the work as a blueprint for a film scene. Schoenberg approached Begleitungsmusik similarly to his programmatic concert works in the sense that contrasts—both structural and textural—express the program’s dramatic elements. Begleitungsmusik’s form projects a trajectory from an initial calm state, through a gradually escalating sense of urgency, to a dynamic and textural climax that is followed by a modified return to the beginning. However, other features suggest that Schoenberg experimented with expressive strategies for film music, including stinger chords and sudden tempo changes that express fear and alarm, as well as the work’s “popular” theme and variation form, which allows easy division into cues and allows repeating themes as well as a sense of dramatic development. In addition, the piece evokes musical topics—particularly the military and the waltz—albeit for a dark and ominous effect.

[35] Begleitungsmusik’s brief episodes and overall sense of acceleration accommodate a cinematic rhythm that supports the program’s escalating drama from Threatening Danger, through Fear, to Catastrophe. Inspired by Schoenberg’s attempt to compose film music that was closely related to the dramatic narrative evident in his initial work for The Good Earth, our creative choices were guided by the textural, thematic, and structural observations outlined in this analysis. At the same time, moments in the film may direct viewers’ attention to musical features related to articulation and timbre that may not be intentional, such as the crystal chandeliers in episode III discussed above. Such coincidental connections express the dialectical tension that Adorno and Eisler articulate between the musical and visual aspects of film, in which music seems to be expressing visual motion while at the same time providing impetus for it:

The photographed picture as such lacks motivation for movement; only indirectly do we realize that the pictures are in motion, that the frozen replica of external reality has suddenly been endowed with the spontaneity that it was deprived by its fixation. . . At this point the music intervenes, supplying momentum, muscular energy, a sense of corporeity. . . Its aesthetic effect is that of a stimulus of motion, not a reduplication of motion. . . Thus, the relation between music and pictures is antithetic at the very moment when the deepest unity is achieved. (Adorno and Eisler 1947, 52)

The film we created for Begleitungsmusik, then, is not only the product of an analysis, but also a text that could motivate further analytical insights and supplement a written analysis. While expressing musical analysis through film proves remarkably appropriate to Begleitungsmusik in particular, in fact, analytical visualization can contribute to an array of interpretive approaches, allowing listeners to connect an analytical reading in real time to their experience.

Orit Hilewicz

Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester

1482 East Ave, Rochester, NY 14610

ohilewicz@esm.rochester.edu

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor and Hanns Eisler. 1947. Composing for the Films. The Athlone Press.

Babbitt, Milton. 2003. “Three Essays on Schoenberg (1968): Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 36.” In the Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt. Edited by Stephen Peles, 222–226. Princeton University Press.

Bailey, Walter. 1984. Programmatic Elements in the Works of Schoenberg. UMI Research Press.

—————. 2010. “Listening to Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto.” In The Cambridge Companion to Schoenberg. Edited by Jennifer Shaw and Joseph Auner. Cambridge University Press.

Boss, Jack. 2014. Schoenberg’s Twelve-Tone Music. Cambridge University Press.

Eisler, Hanns. 1941. “Film Music: Work in Progress.” Historic Journal of Film, Radio and Television 18 (4): 591–594.

Evans, Brian. 2005. “Foundations of a Visual Music.” Computer Music Journal 29 (4): 11–24.

Evans, Joan. 1988. “New Light on the First Performances of Arnold Schoenberg’s Opera 34 and 35.” Journal of the Arnold Schoenberg Institute 2: 163–173.

Feisst, Sabine M. 1999. “Arnold Schoenberg and the Cinematic Art.” The Musical Quarterly 83 (1): 93–113.

Gorbman, Claudia. 1987. Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Graff, Peter. 2016. “Re-Evaluating the Silent-Film Music Holdings at the Library of Congress.” Notes (September): 33–76.

Haimo, Ethan. 1990. Schoenberg’s Serial Odyssey: The Evolution of his Twelve-tone Method, 1914–1928. Clarendon Press.

—————. 2002. “Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielszene Op. 34.” In Arnold Schönberg: Interpretationen seiner Werke. Edited by Gerold W. Gruber, 511–526. Laaber.

Heneghan, Áine. 2006. “Tradition as Muse: Schoenberg’s Musical Morphology and Nascent Dodecaphony.” PhD diss., The University of Dublin, Trinity College.

Hilewicz, Orit and Stephen Sewell. 2021. “A Film Scene for Schoenberg’s Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielscene.” SMT-V 7.3, http://www.smt-v.org/archives/volume7.html

Hush, David. 1984. “Modes of Continuity in Schoenberg’s Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielszene Opus 34.” Journal of the Arnold Schoenberg Institute 8 (1): 83–85 (S1–S45).

Jenkins, J. Daniel. 2016. Schoenberg’s Program Notes and Musical Analyses. Oxford University Press.

Lehman, Frank. 2018. “Film-as-Concert Music and the Formal Implications of ‘Cinematic Listening’.” Music Analysis 37 (1): 7–46.

Maus, Fred Everett. 1988. “Music as Drama.” Music Theory Spectrum 10: 56–73.

Neumeyer, David. 1993. “Schoenberg at the Movies: Dodecaphony and Film.” Music Theory Online 0 (1).

Newlin, Dika. 1980. Schoenberg Remembered: Diaries and Recollections (1938–76). Pendragon Press.

Robinson, Jenefer, and Robert S. Hatten. 2012. “Emotions in Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 34 (2): 71–106.

Rudd, Melanie, Kathleen D. Vohs, and Jennifer Aaker. 2012. “Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being.” Association for Psychological Research 23 (10): 1130–1136.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1975. Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg. Edited by Leonard Stein, tr. Leo Black. University of California Press.

—————. 1994. Coherence, Counterpoint, Instrumentation, Instruction in Form: Zusammenhang, Kontrapunkt, Instrumentation, Formenlehre. Edited by Severine Neff, tr. Charlotte Cross and Severine Neff. University of Nebraska Press.

Thayer, Julian F., Fredrik Åhs, Mats Fredrikson, John J. Sollers III, and Tor D .Wager. 2012. “A Meta-Analysis of Heart Rate Variability and Neuroimaging Studies: Implications for Heart Rate Variability as a Marker of Stress and Health.” Neuroscience and Behavioral Review 36: 747–756.

APPENDIX: List of Source Footage

APPENDIX: List of Source Footage

Ghosts before Breakfast [Vormittagspuk]. Directed by Hans Richter. 14 July, 1928.

The Good Earth. Directed by Sidney Franklin, Victor Fleming, Gustav Machaty, and Sam Wood, Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer. 6 August, 1937.

The Holy Mountain [Der Heilige Berg]. Directed by Arnold Fanck, UFA. November 1926.

King Kong. Directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, RKO Radio Pictures. 7 April, 1933.

Metropolis. Directed by Fritz Lang, UFA. 13 March, 1927.

October (Ten Days that Shook the World). Directed by Grigoriy Aleksandrov and Sergei Eisenstein, Sovkino. 24 September, 1928.

Un Chien Andalou. Directed by Luis Buñuel, 6 June 1929.

Footnotes

* I am grateful to Joe Dubiel, Ellie Hisama, Danny Jenkins, and the two anonymous readers for their illuminating comments on early drafts of this paper, and to SMT-V, the Society for Music Theory, and especially Poundie Burstein and Jocelyn Neal for their generous support of the film project. The analytical film discussed in this article appears in Hilewicz and Sewell 2021.

Return to text

1. The program’s brevity and its themes remind of the Piano Concerto op. 42 (1942), which includes the following section markings in the score: “Life was so easy;” “Suddenly hatred broke out;” “A grave situation was created;” and “But life goes on.” Schoenberg composed the concerto after fleeing Germany following the rise of the Nazis, and its program is usually assumed to be autobiographical. According to Walter Bailey, Schoenberg had already thought of the program when he worked on the concerto’s earliest drafts, but it seems that Schoenberg did not intend to publish the program, and indeed it is missing in the published score (1984, 137).

Return to text

2. “I would further claim that the practical problems with the tests support an assertion that composing a good film score is not at all easy” (Neumeyer 1993, [18]; italics in the original). Claudia Gorbman (1987) introduced commutation tests. On a sidenote, it would have been surprising if Neumeyer’s tests had succeeded; as I elaborate below, Begleitungsmusik includes several climactic moments, and the odds of these moments synchronizing with existing dramatic climaxes in a scene are slim. (Neumeyer included in his experiments scenes from Frankenstein [1931], The Blue Angel [1930], Public Enemy [1931], and other films.) There are few examples of successful synchronizations between existing music and films, including the fabled pairing of Pink Floyd’s The Wall (without “Comfortably Numb”) with Disney’s animated Alice in Wonderland (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtExVJlgEC0&list=PLM2QHoPZnLwr0fZ0AA3Wtnw-On5O9PksQ&index=2).

Return to text

3. “When Berlin’s UFA made its first successful experiments with talking pictures, about 1928 or 1929, I was invited to record myself in picture and sound. The speech I delivered was an enthusiastic address of welcome to the new invention through which I expected a renaissance of the arts” (Schoenberg 1975, 153). Schoenberg composed Begleitungsmusik around the time he delivered that speech. His remarks on films were first published a decade later, and they specifically concern the film industry, not the medium: “The production of moving pictures abandoned entirely every attempt towards art and remained an industry, mercilessly suppressing every dangerous trait of art” (ibid.).

Return to text

4. Feisst’s article includes a letter Schoenberg wrote to MGM’s legendary producer Irvin Thalberg, in which the composer restates his enthusiasm about the project. Feisst also relies on the heavily annotated copy of Pearl S. Buck’s eponymous novel found in Schoenberg’s library, as well as the score drafts Schoenberg had already started producing for some scenes and characters (1999, 93–94). I should note that, referring to the same pieces of evidence, Walter Bailey concludes that Schoenberg did not take film music seriously (1984, 24).

Return to text

5. This film has been published as Hilewicz and Sewell (2021).

Return to text

6. By editing the footage to accompany the music rather than let a scene play over the music, we were able to avoid many of the practical problems Neumeyer (1993) encountered. For example, the montage design allowed us to synchronize musical and cinematic moments of climax.

Return to text

7. In its structural and expressive reliance on aspects of Schoenberg’s piece, our film resembles “visual music”: rhythmic animated films representing musical pieces (Evans 2005).

Return to text

8. Newlin 1980, 207. A study of compilation scores available at the Library of Congress shows that the three components of Begleitungsmusik’s program could potentially serve as the titles of musical cues for silent films (Graff 2016).

Return to text

9. The piece was first performed on a radio broadcast without a live audience in April 1930—about six months before its official premiere—by Hans Rosbaud and the Südwestfunk Symphony Orchestra. Joan Evans stipulates that “the absence of a live radio audience led Schoenberg to consider the event as something other than a full-fledged premiere” (Evans 1988, 167, quoted in Feisst 1999 and Jenkins 2016).

Return to text

10. “Wie herrlich ist das bei Dir! Wieder ist ein Werk da: die Lichtspielbegleitmusik. Ich besitze es natürlich schon und bin - nach kurzem Studium schon - begeistert. Es ist natürlich auch ohne Film ein vollständiges Kunst-werk; aber wäre es nicht wunderbar, wenn diese Musik synchronistisch (oder wie das heißt!) zu einem von Dir erfundenen Film ertönte. Wenn Du dazu Lust hättest, müßte das doch in Berlin leicht durchführbar sein!” (Translated by the author.)

Return to text

11. Feisst 1999, 98 (italics added). Klemperer is referring to Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy.

Return to text

12. On a different occasion, Schoenberg emphatically suggested that, when used as film score, Begleitungsmusik would be best matched to art films (Feisst 1999, 98).

Return to text

13. Jenefer Robinson and Robert Hatten (2012) observe that listening to music in general often involves this kind of dramatic interpretation: “as we listen to some complex music, we seem to be moving on an emotional journey in which our

Return to text

14. Ethan Haimo (1990, 7) provides an overview of Schoenberg’s mature style, which he considers as starting with Von Heute auf Morgen, op. 32.

Return to text

15. While inversional hexachordal combinatoriality is considered a token of Schoenberg’s style, (Haimo 1990, 8–11), inversion around the first note is not common as a significant relationship in Schoenberg’s works. Haimo (2002) has hypothesized that Schoenberg may have chosen to use inversion around the first note in Begleitungsmusik in order to avoid excessive repetition. In his notebooks, Schoenberg described unmodified repetition as a “primitive” device that could degenerate to monotony, and Haimo shows that inversion around the first note allows greater harmonic variety (517).

Return to text

16. Jack Boss (2014) refers to the palindromic dyads in mm. 1–5 and 7–9 of the Suite op. 25, created by inversion around the first note of P4, as the driving force for the entire Prelude (45).

Return to text

17. Each of the Violin Concerto’s thematic areas features a distinct combinatorial series-form complex: series forms in the second thematic area are inversions of the first. However, the Concerto’s series is more symmetrical than that of Begleitungsmusik; the former is comprised of segmental trichordal invariance between series forms inverted around the first note (Babbitt 2003, 222–26).

Return to text

18. Hush (1984) compares Begleitungsmusik to Erwartung (1909) and Die glückliche Hand (1913), which he presents as earlier attempts by Schoenberg to employ contraction as an expressive strategy.

Return to text

19. Notably, Haimo suggests that Catastrophe is represented in just a pair of measures, in which the piece arrives at its dynamic and dramatic high point.

Return to text

20. “Der gewaltige Höhepunkt in den Takten 170–171 klingt zwar wie eine Katastrophe

Return to text

21. Fred Maus proposes that, in presenting a series of actions performed by fictional characters (which in music would be indeterminate), happening in real time for the audience, a musical work can be understood as a “kind of drama that lacks determinate characters.” The plot provides the dramatic structure that holds the series of actions together (1988, 71–72). Robinson and Hatten explain expressiveness in music somewhat similarly as “the genuine expression of genuine emotion in an imagined persona. Expressiveness has psychological reality, even though it is a fictional person, not a real one, who is expressing the emotions in question” (2012, 78; italics in the original).

Return to text

22. Jenkins 2016, 328–29. The cues provide an idea of the work’s dramatic arc: Starting with “the calm before the storm,” then “the threatening danger appears” and “the threatened become anxious,” the cues indicate a gradually escalating danger. They culminate in one of two possible endings: either “catastrophe” and “collapse,” or “the danger passes,” followed by “alleviation of the tension of the threatened (salvation, deliverance).”

Return to text

23. The identical succession of interval classes in Examples 3b and 4 is derived from hexachords of I3 and RI1, respectively.

Return to text

24. Schoenberg makes this distinction in his 1917 notebooks (see Schoenberg 1994, 38–43).

Return to text

25. For example, Heneghan interprets the motives in variations 4 and 5 as derived (through developing variation) from a fourteen-note succession in variation 2 (2006, 135).

Return to text

26. I further stipulate the significance of the theme and variation form in the conclusion of this article.

Return to text

27. Film scores turned into orchestral works, and the ways in which one listens to them are the topics of an illuminating account by Frank Lehman (2018). One can conceive of the reverse process in Begleitungsmusik, in which extracted episodes would be combined as non-diegetic cues in a full-length feature.

Return to text

28. Numerous studies confirm that fear is characterized by higher heart rate (Thayer et al. 2012, 749). Robinson and Hatten discuss this basic type of representation, in which musical gestures resemble gestures or behaviors characteristic of a human (2012, 75).

Return to text

29. The sensation of frozen time is commonly related to the experience of awe and shock (either positive or negative). Indeed, research shows that feeling overwhelmed leads to a sensation of time standing still (Rudd et al. 2012, 1135). While the research concentrated on positive experiences of awe, its suppositions hold for negative awe-generating events (such as, for example, natural disasters) as well.

Return to text

30. Our film features the recording by Takuo Yuasa and Ulster Orchestra (2002), courtesy of Naxos of America, Inc.

Return to text

31. I follow Hush’s episode labels, which for the most part (except for episode X) conform to tempo changes in the score.

Return to text

32. This setting agrees with Schoenberg’s cue for the beginning in his draft: “the calm before the storm” (Jenkins 2016, 329).

Return to text

33. The musical foreshadowing of the stinger in episode II is discussed in paragraph [23] above, and the footage for the stinger that closes Threatening Danger appears towards the end of Video Example 2.

Return to text

34. The quickly darkening sky, anticipating this storm, appears during Threatening Danger in episode III (Video Example 2).

Return to text

35. Admittedly, my motivation for this ending was not Schoenberg’s programmatic notes, with which I was not familiar at the time, but rather the introduction’s return at the end, which implies to me a sense of hope in the aftermath of the catastrophe. I am grateful to the anonymous reader who brought Schoenberg’s program sketch (in Jenkins 2016, 329) to my attention and pointed to the dramatic similarities.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2021 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Lauren Irschick, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

7754