Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase and the Experience of Time, or Why Does Process Music Work?*

Mariusz Kozak

KEYWORDS: time, dance, Reich, Violin Phase, affect, embodiment

ABSTRACT: Reich’s Violin Phase has been mired in questions of time since its inception. In this article I present a theory of time in process music based on the notion of kinesthetic knowledge, and the synthesis of musical temporality through the generative (chronopoietic) and transformational (chronopraxial) acts of the body. I illustrate this theory with an analysis of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s choreography to Violin Phase, arguing that the dance serves as a proto-theory of the piece by creating and transforming its temporal trajectory. I draw attention to the role of structural convergences and divergences between dance and music, as well as of the emerging “resulting patterns,” in establishing and maintaining an emotional connection between the dancer and her audience. By closely examining the relationship between the music and De Keersmaeker’s movements, how together they create the space of the dance, and how the energy accumulated through incessant repetition gives shape to the aesthetic event, I argue that the choreography draws attention to novel temporal aspects of Reich’s piece.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.2.11

Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory

[1] SPEAKING OF TIME

[1.1] If Lawrence Zbikowski is right that “to speak of time, in any substantive way, is to court madness” (Zbikowski 2016, 33), then to do so again and again, willingly and with unassailable conviction, must surely be the pinnacle of absurdity. Yet to speak of music, in any substantive way, without also speaking of time, is to court discontent (or worse), for it almost goes without saying—and, when actually said, is taken on principle—that music, owing to its immateriality and ephemerality, is a fundamentally temporal art.(1) Whether it takes time, or makes time, or is made up of time, music needs time as its vector (Kozak 2020), and so to understand the former we must also get a handle on the latter, even if it seems like we are nowhere near reaching consensus about the nature of either.

[1.2] To speak of time, in any substantive way, without the use of analogies and metaphors is to court obscurity. Some shopworn, others newfangled, they expedite our cognitive grasp by placing the less understood concept in dialogue with a more concrete, embodied experience (Zbikowski 2017). We draw timelines; we imagine rivers; we follow arrows. Sometimes we move; at other times time moves.(2) All of these add to the vast repertoire of resources for time-thinking that we humans have amassed over the course of millennia and consolidated in a variety of representations, including clocks, calendars, charts, tables, and even monuments. And all rely on a cognitive dissonance that always takes place when two different domains are placed side by side, a dissonance that allows—to borrow from David McNeill’s (1992) work on speech-accompanying gestures—for the emergence of a growth point, or an unstable, dynamic unit of thought that spurs further intellectual discovery.

Example 1. Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Violin Phase

(click to watch video)

[1.3] Here, I place the sonic art in dialogue with its (equally temporal) sister, dance, in the hopes of creating just such a growth point, a moment of mild discord that can augment our repertoire of resources for music- and time-thinking. In particular, I examine the relationship between Steve Reich’s Violin Phase (1967) and its choreographic interpretation by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker in her homonymously titled piece from 1982, seen in Example 1. My goal is to show how the combination of the two media brings exposure to the process through which time emerges out of basic human actions, and how this process in turn colors our emotional and bodily experiences of music.

[2] LINEAR, NONLINEAR, AND VERTICAL TIME: A CRITIQUE

[2.1] Reich’s interminably repetitive process music—a subset of minimalist music in which each piece’s compositional design is coextensive with its audible materiality,(3) and which, in addition to Violin Phase, includes such works as Piano Phase (1967) and Clapping Music (1972)—has always been mired in questions of time.(4) Often emphasizing its goalless (non-teleological) nature, descriptions are rife with references to an endless present, to temporal suspension, to hypnosis and stasis.(5) Jonathan Kramer, for example, singles out Violin Phase as an example of music that is “uncompromisingly vertical” (1988, 386). By verticality, Kramer means extremely nonlinear music, or music that obstructs listener’s normative processes of memory and expectation by severing connections with its own past and future. The listener encounters only an extended present, a static moment in which they are allowed to “merge with the music” (385) in an act reminiscent of Eastern meditative techniques.(6) Vertical music is said to force the listener to attend to “an arbitrarily bounded segment of a potentially eternal continuum” (386), which Kramer contrasts with a linear, “processive” temporality that arises when “some characteristic(s) of music are determined in accordance with implications that arise from earlier events in the piece” (20).

[2.2] For Kramer, the verticality of Violin Phase is evident in its lack of a structural hierarchy to which listeners could pin their cognitive efforts. Its musical features are determined on the basis of “implications that arise from principles or tendencies governing an entire piece” (20), whereby the music is constituted by “immutable relationships” present from the very beginning. There is nothing to help the listener gather up events into larger groups or to dissipate the momentum that accumulates over the course of the work; there is no possibility of growth or transformation. Kramer writes: “we lose any point of reference, any contact with faster or slower motion that might keep us aware of the music’s directionality” (57). Attempts to fight this disorientation and locate oneself in the flux risk provoking boredom or frustration.

Example 2. Steve Reich, Violin Phase. Basic pattern.

(click to enlarge)

[2.3] Picking up Kramer’s temporal categories but using them to justify a contrary interpretation, Richard Cohn (1992) has shown that Reich managed to create a fairly typical narrative trajectory by subjecting the basic pattern(7) of Violin Phase (shown here in Example 2) to the process of phase shifting. In a meandering fashion, this trajectory ends up saturating the musical surface with some of the pitches that Cohn considers to be the most salient.(8) In particular, Cohn offers a formally rigorous, mathematically grounded analysis to demonstrate that this indirect saturation is due to a so-called deep scale property of the rhythmic pattern made up of the lowest and highest pitches in the repeating unit:

[2.4] Cohn’s conclusion is that the narrative trajectory of Violin Phase serves as evidence that the listener’s experience of this piece is shaped by a linear temporality.(9) More importantly, I think, Cohn’s analysis also demonstrates that the distinction between Kramer’s temporal categories loses much of its traction once it leaves the comfort of the philosopher’s armchair and finds its way into the analyst’s toolbox. It is obvious that Reich’s piece is characterized by growth and transformation because the very process of phase shifting is necessarily transformational.(10) In consequence, linearity and nonlinearity end up exerting limited explanatory power because, at heart, their primary concern lies in the musical meaning of continuity and a special kind of predictability that this continuity supports.(11) Kramer’s tipped hand reveals that his default mode of listening relies on what might be called “orienteering” strategies—strategies that allow one to find their place in the music, to know where they are at any particular moment, to know (more or less) how much time has passed and how much is left, and so on. Such task-based listening, in which the listener is saddled with mapping out the temporal terrain, always deflects the point of contact with the music to some moment that is not explicitly given to the listener’s consciousness. The focus implied by this strategy is at all times precisely on what is not happening right now, precisely on what is not the immediate content of experience. If the music fails to support this kind of listening—for example, when it consists of an unchanging context—then all that the listener is able to attend to is the present, which, for Kramer, makes this present “timeless,” hence vertical.

[2.5] Yet the present is never a naked presentation of raw facts about the perceived world. Instead, it is always already framed by what Edmund Husserl called retentions and protentions, fragments of consciousness that spill out beyond what is explicitly given to perception and gradually drift off into the past and the future, respectively.(12) Thus, to say that an unyielding focus on the present is “timeless” is neither true, nor fully comprehensible. The present is one of the constitutive dimensions of time—by definition, it cannot be “timeless.”(13)

[2.6] To Kramer’s credit, his temporal categories of linearity and nonlinearity refer to listening strategies, not objective facts about the score.(14) The listener approaches the music with one or another strategy, and the degree to which this strategy is rewarded depends on the technical aspects of the piece. But while this rightly acknowledges the agency that this listener brings to the musical encounter, the encounter itself is ultimately described in passive terms. The point here is subtle, but it bears emphasizing because it has profound ramifications for the way musical time is conceptualized and experienced. By positing different temporalities as characteristic of musical materials and systems governing how these materials are organized, Kramer paints himself into a corner in which the listener needs to conform to those temporalities if their experience is to be meaningful.(15) Missing from Kramer’s account is the recognition of the potential of the listener to effect one or the other strategy and what might fall out of the listening situation if this potential were actualized. By contrast, active listening is a process in which the relationship between the agent and the music undergoes constant change. Active listening to nonlinear music—even of the “uncompromisingly vertical” variety like Violin Phase—with a linear strategy does not have to be boring or frustrating; the piece does set up its own expectations, and these expectations are useful in guiding the experience of the listener, even if the nature of this experience is of a different kind than what interests Kramer.

[2.7] This is not to deny that process music shapes temporality in ways that feel different from the music of “Beethoven, Brahms, Berg, [and] the Beatles” (Fink 2005). However, by pitting the different styles against one another, and using them as evidence of ontologically differentiated forms of time, Kramer ultimately leads us down a blind alley. His dualist framework results in a hearing of Violin Phase that, for me at least, robs the piece of layers of significance by forcing the analyst to assume a definitive stance regarding the terms of the binary opposition. At best, these terms may lie on a continuum, but even then there is an injunction to spell out the exact placement of the experience along a single axis.(16) Is this moment 40% linear and 60% nonlinear? Or closer to 50/50? Our choices seem to swivel between black-and-white and infinite shades of grey.

[3] AN ALTERNATIVE TEMPORALITY

[3.1] We can cut across Kramer’s linear/nonlinear binary by shifting our focus toward the inherent mutability of each listening situation and enumerating the factors that precipitate its transformation. This not only promises to enrich our analytical narratives and unveil new points of contact with the music, but, by opening up different temporalities that are not bound to metaphors of linearity, also indexes music’s relationship to our experience of time in general.

[3.2] This essay thus takes a step toward explicating a particular temporal trajectory in Violin Phase by drawing on the synthesis of processes that unfold not just in the audible materiality of the music, but also in the visuo-sonic fabric that spins out from the combination of this music with dance.(17) Specifically, I will consider how time in Reich’s piece is illuminated through Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase (1982), one of the movements in her Fase: Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich. (See again the video in Example 1.)(18)

[3.3] From the outset, I must stress two points. First, although the film depicting De Keersmaeker’s 1983 performance is heavily mediated through the use of dynamic camera techniques, I treat it not as an aesthetic object in its own right (which, of course, it is), but rather as a stand-in, or a convenient anchor, for a more general aesthetic event that outlives any of its visually captured exemplars (similarly to how we treat musical scores). My own experience of the dance encompasses not just this video, but also several live performances that I attended over the years, including those featuring different dancers. It is from this position that I embark on my discussion. This means, among other things, that I will not consider how the film’s director, Thierry De Mey, manipulates the camera to focus our attention on different aspects of the dance: De Keersmaeker’s facial expressions, her moving feet, the sand-covered stage, or the dramatic sequence in the final minutes of the performance.(19) This also means that I will not address the sand on which De Keersmaeker draws the enigmatic rosette, simply because for more than three decades Violin Phase has almost always been performed on an empty stage, and there is some evidence that the arenaceous inscription was an afterthought in the choreographic process.(20) While this has many implications for a hermeneutic reading of the piece—most obviously regarding the relationship of the dancer to herself through the traces of the steps she makes and subsequently erases—I will not explore any of them in this article. Moreover, in 2018 De Keersmaeker passed the baton to a new generation of dancers, Yuika Hashimoto and Soa Ratsifandrihana (De Keersmaeker 2019), both of whom are members of De Keersmaeker’s dance troupe Rosas. I included Hashimoto’s rendition—from a 2018 performance at the “Échelle Humane” dance festival at Lafayette Anticipations—as an insert to the accompanying video because it illustrates very clearly both the steps and how the dance unfolds in space. Whereas the large screen in Example 1 illustrates De Keersmaeker’s performance, Hashimoto’s dance can be viewed in the bottom right corner within the video. Most importantly for my purposes, the video also demonstrates the striking difference in how the two dancers approach the timing of the dance and the relationship of their movements to the music.

[3.4] The second main caveat is that what I present below is not a conventional music analysis in the sense of deciphering systems that underlie how the piece had been put together. Nor is it an analysis of the dance as a standalone aesthetic event. Instead, it is a move that considers De Keersmaeker’s choreography as a prism for Reich’s Violin Phase, a notion emboldened by Ian Quinn’s comments about the role of analysis in process music. Specifically, Quinn points out that the high redundancy and low information content that characterize this music present a challenge to the analyst because the familiar act of “decoding” surface events and linking them to an underlying structure has already been “short-circuited” by the composer. There is no need here for a puzzle-cracking Enigma machine, so the analyst’s response to this challenge is to “turn the normal function of analysis on its head. Traditionally, analysis aims to reduce the information content of a piece . . . by parsing it relative to some well-understood system of formal conceptual categories. Process music comes to the table already digested; its challenge to the analyst-as-interpreter is precisely the minimal challenge it presents to the analyst-as-parser” (2006, 292–93). To me, turning analysis on its head suggests that instead of asking how the piece works, the interpreter starts by inquiring why it works. According to Quinn, this ultimately amounts to fantasizing: to creating theoretical frameworks that can enfold other musics, or even other phenomena, in an effort to generate new insights about the piece. After all, the etymological roots of theoria include sight, spectacle, speculation, feelings of wonder and astonishment. As I will argue, De Keersmaeker enacts just such a framework by creating a space in which we find process embodied both in the spectacle of the dancer’s gestures, as well as more transiently in the relationship between her and the audience. My goal is to encourage a new mode of hearing Violin Phase by reframing relentless repetition within the temporal trajectory created in front of the viewer by a moving human body. In short, trying to imagine an alternative to the linear/nonlinear binary stipulated by Kramer, I reflect on the ways in which De Keersmaeker’s dance unlocks a different avenue for experiencing time in Reich’s piece.

[3.5] What makes De Keersmaeker’s work auspicious for this kind of speculative project—an experiment in listening, really—is the ease with which it incorporates the audience into the spectacle by leveraging what Arnie Cox (2017) calls a “mimetic invitation,” his term for the sense that auditory and visual phenomena solicit from listeners and viewers congruent bodily responses. There is clarity to the choreographic process, likely the result of its sheer simplicity: “It is in essence the movements children make when you ask them to dance: turning, jumping, waving their arms about. And walking” (De Keersmaeker quoted in Gyselinck 2018).(21) This austere, vagabond lexicon of gestures draws viewers into De Keersmaeker’s aesthetic universe. The choreographer continues: “It’s a vocabulary which will make the audience members believe they’ll be able to do, too—movements people can see themselves doing as non-dancers.” Inspired by the unpretentious display, viewers repeatedly try out the material “at the bus stop after a performance. The potential for imitation is important, it is an important way for dancers to make a connection with their audience.”(22) With its insistent invitation to enact a congruent bodily response, the piece displaces the fourth wall, folding spectators into the performance and according their presence a vital role in co-creating the aesthetic event.

[3.6] Even if the invitation is not explicit and the solicited response remains covert—there obtains the usual separation between the performer and a motionless audience—the child-like movements are crucial to the temporal unfolding of the piece, and so I encourage the reader (if possible) to perform De Keersmaeker’s gestures to get a sense for what they feel like, especially in combination with Reich’s music. The reason for this will become apparent over the course of my discussion, but it essentially has to do with how I conceive of musical time.

[3.7] I have argued elsewhere that time as it shows up in the course of a musical experience is neither an objective fact of the world embedded in the acoustical signal, nor a fiction we fabricate independently of things that happen while we are listening (Kozak 2020). Instead, time in music is constituted by a skillfully moving body having a particular kind of knowledge of what it feels like to experience and make sense of certain sonic events. This perspective is in line with the philosophical tradition rooted in the work of Henri Bergson and post-Husserlian

[4] DE KEERSMAEKER’S Violin Phase

[4.1] Mirroring the discourse surrounding Reich’s process music, comments on De Keersmaeker’s piece are equally replete with references to themes of altered temporal states, including stasis, the extended present, the collapse of time and space, and infinity.(26) However, the choreographer is unequivocal about the timeline of her Violin Phase, stating that “unlike the musical score, my dance is not a mere slice of eternity. There is a clear beginning, a middle, and an end, with plenty of tension in between. It is not a display of Eastern meditation” (De Keersmaeker quoted in Bellon 2018). Although suggestions that the score slices through eternity are debatable in light of Cohn’s (1992) abovementioned analysis, De Keersmaeker’s reflection does imply that we can understand and experience the temporality of her Violin Phase as having a specific trajectory. I propose that this trajectory is shaped by three vectors converging onto the aesthetic event: (1) the extraction of “hidden” melodies from the musical surface by the violinist (what Reich calls “resulting patterns” or “resultants”); (2) the synthesis of the technics of time in moments of structural convergence and divergence between the dance and the music; and (3) the accumulation of physical and emotional intensity through the incessant repetition of the music and the co-occurring movements.(27)

“Hidden” melodies

[4.2] Marion Guck writes that “any analysis of music derives necessarily from personal experience of music” (1994, 266), which reminds us that the role of the human subject who turns silent inscriptions into audible vibrations (either playing them on their own, or listening to a recording) is of utter importance to the kinds of interpretive statements the analyst can make.(28) Consequently, we must carefully consider the creative interventions by the violinist, Shem Guibbory, in the 1980 recording of Violin Phase used by De Keersmaeker. Guibbory’s involvement is especially relevant because in the published score Reich (1979) personally thanks him for drawing attention to several resultants that emerge from the surface of the piece.

[4.3] Guibbory’s interpretation, which lasts some fifteen minutes and ten seconds (excluding the silence at the beginning of the track), is decidedly faster than the first commercially available recording of Violin Phase, made in 1968 by Paul Zukofsky on an album titled Steve Reich: Live/Electric Music. Guibbory’s tempo is a brisk 150 bpm, compared to Zukofsky’s 100 bpm. This makes Guibbory’s rendition flow much more smoothly, while Zukofsky’s, by comparison, feels more halting and pedantic.

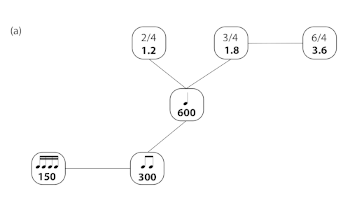

Example 3. Multiply related metric periodicities in (a) Zukofsky’s and (b) Guibbory’s recordings of Reich’s Violin Phase

(click to enlarge)

[4.4] The contrast between the two recordings can be elucidated using Justin London’s (2012) graph of multiply related metric periodicities, as shown in Example 3. Assuming the quarter note as the tactus (in the middle of each graph), of particular interest is the timing of the whole 6/4 measure that encompasses the basic pattern: in Zukofsky’s version the duration is 3.6 seconds (s), while in Guibbory’s it is 2.4s. This places the former much closer to the upper limit of entrainment. On the other end of the spectrum, Zukofsky articulates each eighth note at around 300 milliseconds (ms), while Guibbory does the same at 200ms. Again, the disparity here is considerable, such that the former is within the range of pulses that can be further subdivided into sixteenth notes, while the latter falls outside of that range. In effect, this means that, given the cognitive and bodily limits of the listener, the eighth-note pulse can function as the tactus in Zukofsky’s, but not in Guibbory’s, rendition (London 2012).

[4.5] The different candidates for the role of the tactus account for each version’s distinct feeling. Guibbory’s tempo places the tactus in a “temporal no-man’s land” of 400ms (London 2012, 34), a liminal space in which the beat level is malleable and yields flexibly to the listener’s shifting attention. As such, it creates a higher ceiling of metrical levels than does Zukofsky’s recording, which means that it presents to the listener more possibilities for larger note groupings. One grouping that De Keersmaeker exploits in her dance is the non-isochronous division of the metrical cycle into 7 and 5 eighth notes. By using Guibbory’s recording, that grouping results in 1.4s for 7 eighth notes, and 1s for 5 eighth-notes. By contrast, Zukofsky’s would have resulted, respectively, in 2.1s and 1.5s. The former of these values is close to the duration of the entire basic pattern as played by Guibbory. We also see from the graph that, at 1.5s, the 5-grouping in Zukofsky’s version is slower than the 7-grouping in Guibbory’s. In all, the body’s own limits on entrainability would have made it difficult to articulate the 7+5 pattern with the kind of drive, energy, and fluidity that is evident in De Keersmaeker’s dance.

[4.6] This suggests that had De Keersmaeker gone with Zukofsky’s recording, she would have likely correlated her movements with the eighth- and quarter-note levels, resulting in a choreography that stayed close to the musical surface. In turn, this would have made it difficult to embody processes of phasing, repetition, and accumulation of energy, because the amount of detail at this level would have been overwhelming for the viewer. Instead, following Guibbory’s tempo allowed De Keersmaeker to correlate her movements with larger groupings, creating a choreography that centers on some of the deeper levels of musical structure. One might posit that the choice of the recording made it possible for the dancer to convincingly embody processes evident in Reich’s music, while enfolding longer time spans within her gestures allowed for a greater sense of a coherent temporal trajectory than if De Keersmaeker had directed our attention to the details.

[4.7] These observations are consistent with De Keersmaeker’s own reflections about what drew her to Reich’s piece. Although the compositional techniques of phase shifting and gradual transformation provided her with the basic movement vocabulary and a roadmap for its development, what she heard in Violin Phase first and foremost was that “this was music that [she] would like to dance to” (De Keersmaeker 2012, 23). Referring on a number of occasions to the “Stehgeiger idiom”—a (typically Jewish) figure of a violinist conductor of Weimar Republic salon orchestras, later associated with German jazz—she remarks that “there is something klezmer-like about [Reich’s music]; somebody in the village grabs a violin and people start dancing their rondo” (quoted in Bellon 2018).(29)

Example 4. Steve Reich, Violin Phase, “resulting patterns”

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.8] We can be even more precise about what inspired De Keersmaeker: it was the melodies—the abovementioned “resultants,” shown here in Example 4—that precipitate from the saturated sonic surface. She writes that the piece “has a strong pulse that naturally invites one to dance, a beautiful melody and a kind of physical texture characteristic of Yiddish violin playing, of a Stehgeiger, and a clear process unfolding through the system of accumulation” (De Keersmaeker 2012, 25). She later adds that one of her aesthetic goals was to highlight the emergent melodies with her movements: “I play the red marker that underlines the resulting pattern so that the spectator is invited to join me in the coupling of the music and the dance that occurs in that moment” (ibid., 36).

[4.9] Reich himself considered these melodies to be the key to his Violin Phase, and already in the liner notes to the 1968 recording he writes:

In two sections of the piece the performer gives a sort of auditory “chalk talk” by simply playing one of the pre-existent inner voices in the tape a bit louder and then gradually fading out, leaving the listener momentarily more aware of that particular figure. The choice of these figures (there are many of them) is largely up to the performer, and I want to thank Paul Zukofsky for bringing out several very interesting ones I never would have thought of without him. (Zukofsky 1969)

The producer, David Behrman, describes his own impression:

From [m. 17] to the end, the loops are heard alone to allow the listener to hear all the figures available to him. In listening, one can bring out these and other combination figures by concentrating on them—a little like those puzzle drawings of geometric three-dimensional figures that can be flipped back and forth in space by an effort of will. (ibid.)

Example 5. Derivation of the Violin Phase basic pattern from the gankogui/makwa pattern

(click to enlarge)

[4.10] In his analysis of Reich’s Electric Counterpoint, Martin Scherzinger (2019) shows that the idea of “hidden” melodies precipitating from a supersaturated musical surface points to African sources for the composer’s process-based pieces. One rhythmic figure in particular, the gankogui/makwa pattern originating in Ewe drumming (shown here in Example 5), lends itself especially well to the process of phase shifting because each phase creates a unique pattern of attacks and rests, effectively “saturating the unfolding musical field with variety” (Scherzinger 2019, 291). It also happens to form the rhythmic backdrop of the basic pattern in Violin Phase.(30) Consider the non-double-stopped pitches of the basic pattern,

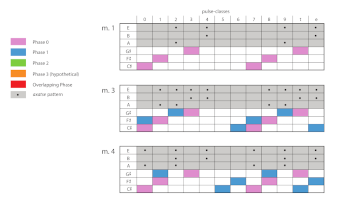

Example 6. Steve Reich, Violin Phase. Phasing of the gankogui/makwa pattern

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

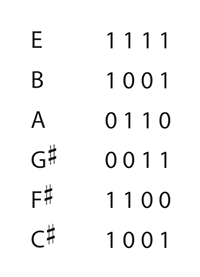

[4.11] Example 6 illustrates what happens to the gankogui/makwa-derived pattern in Violin Phase when it is subject to phase shifting. Each row refers to a single pitch of the basic pattern (shaded rows show double-stopped pitches of the axatse pattern), and each new phase is indicated with a different color. Thus, in m. 1 we hear the pattern by itself (purple), then in m. 3 the first phase is added (blue), which in m. 4 is shifted by one pulse-class to the left (assuming the pattern wraps around), and so on. In addition, pulse-classes where the shifted phase overlaps with an already-sounding pattern are indicated in red (e.g., m. 13).

Example 7. Steve Reich, Violin Phase. Rotations of pulse-classes in m. 16

(click to enlarge)

[4.12] Following Cohn and identifying each articulation by its location in the pulse cycle, let us focus on m. 16, a point where the phasing process of the entire basic pattern stops, and violinist starts bringing out different resultants. First, notice that the musical surface derived from the gankogui/makwa pattern is maximally saturated without any overlap between the voices: each pulse-class is articulated at least once with a unique pattern at any one time (the shaded axatse region will not concern us here). Had Reich added another violin and continued to phase shift the basic pattern (see “hypothetical phase 3” on the bottom of Example 6), a similar saturation would have occurred after two more phase shifts, as I highlighted with a red border. Here, the added hypothetical phasing voice is marked in orange; as before, every pulse-class receives at least one articulation without any overlapping phases. However, there is an important difference with the pattern in m. 16, which leads me to a second point. With the exception of E, each pitch in m. 16 exemplifies a different rotation of the form [1 1 0 0] (where 1 indicates an attack, and 0 a rest; pitches

Example 8. Steve Reich, Violin Phase. 4-eighth note subcycles in m. 16

(click to enlarge)

[4.13] Finally, the process of phase shifting over the course of the whole piece results in a situation in which the 12-eighth-note cycle is divided into three equal subcycles (see Example 8). The basic pattern is truncated to a 4-cycle, which leads to two further observations. One is that the subdivision of the basic pattern engenders a sense that the tempo had increased: things simply change at a faster rate than before. This adds to the overall forward momentum of the piece, even in the absence of any alterations to the pulse. Second, the shorter motifs that the violinists bring out in mm. 19–21 fill the empty beats through the process of phasing, but they do not extend beyond the 4-count length of each subcycle. Such a tight confinement of the patterns to 4-eighth-note units may contribute to the feeling of mentally flipping back and forth between different impressions of the same multistable figure (as described above by Behrman), or perhaps of rotating a single layer on a Rubik’s cube.(34)

Example 9. Steve Reich, Violin Phase. Final “resulting pattern” (mm. 22–22g)

(click to enlarge)

[4.14] Out of this tightly woven structure emerges one last melody (mm. 22–22g; see Example 9). Apparently first worked out by Guibbory,(35) it differs from the other melodies in several respects: spanning thirty-two eighth notes, it is much longer; it makes extensive use of syncopation; it features a smooth, stepwise contour; and it is made up almost entirely of the “inner” elements of the pitch space (

[4.15] What makes it interesting, paradoxically, is how conventional it is as a melody. Note how easily it can be parsed into two contrasting yet symmetrical parts. The first, which I labeled α, consists of four measures that form a stepwise arc that begins and ends on

[4.16] By itself, the melody is surprisingly ordinary, textbook even: it features an archetypal shape, a limited pitch range, and an amusing rhythmic offset that gives it just enough momentum to make it lively but not particularly spellbinding. Yet when stacked up against the incessant 4-cycle still heard in the other auditory layers, the contrast between the smooth arc of α and the more jagged shape of β, together with the alternating on- and off-beat articulations, imbue this breakthrough with a special kind of significance. Hardly laden with Kramerian boredom and frustration, the moment fully and vigorously engages the listener’s faculties of memory and expectation by simultaneously pointing to the past—where the scaffold allowing for the melody’s emergence had been assembled with some labor and diligence—and to the future—where the horizon of possibilities is suddenly blown wide open: What other melodic combinations lurk within this supersaturated audile solution?

[4.17] The importance of this melody for the dance, and for the meaning this dance imparts to the music, cannot be overstated. Indeed, in his praise of De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase, Reich is explicit that she “not only captures the formal aspects of the piece, but, during the extended resulting melodies near the end, goes to the heart of its underlying lyricism” (Reich 2002a, 214). Whereas Cohn’s analysis focused solely on what he considered to be the “invariant” features of the piece—the beat-class organization of pitches—it is here, in this extra-compositional excess, that the drama of the work and the telos that Cohn painstakingly demonstrated are realized to the fullest extent. The significance of this moment is especially clear when one compares Guibbory’s recording to Zukofsky’s: with an exuberant, ecstatic gesture, the former unravels a knot that had been assiduously tied over the course of the piece; the latter mechanically fulfills what had been inevitable from the start.

Structural inclinations: convergence and divergence

[4.18] Of the four movements that constitute De Keersmaeker’s Fase, Violin Phase is perhaps the most difficult to conceptualize because it involves a solo dancer embodying a piece that consists of four distinct auditory layers: a recording of three mixed tracks plus a live violinist (less often, of four live violinists).(37) Unlike the dance duets in Clapping Music, Piano Phase, and Come Out, Violin Phase does not permit any clear mapping between the musicians and the dancers, in which the latter could visually represent the melodic lines produced by the former. This obscures in the visual domain what is perhaps the most audibly distinctive aspect of this corpus: the process of phase shifting. At the same time, it makes clear that De Keersmaeker was not interested in supplying a mere “music visualization” to Reich’s piece.(38) Rather, the dancer’s body adds another element that unfolds in counterpoint with the violins.(39)

[4.19] De Keersmaeker’s corporeal counterpoint consists of gradually introducing and transforming a very basic vocabulary of movements that begin with a twist of the torso. Each twist demarcates the subphrases that make up the basic pattern of the music, dividing it into asymmetrical groups of 7 and 5 eighth notes. After several iterations, De Keersmaeker adds a quarter turn to each twist, which eventually turns into a walk. Still twisting to the same 7+5 count, De Keersmaeker walks clockwise outlining a circle; after reaching the starting point she reverses direction, then once more after another full circle.(40) This could be described as the main “theme” of the dance, and it unfolds over the course of eight measures of the musical score (about four minutes of the fifteen-minute work). After this, coinciding with the start of m. 9 (3:57), a series of eleven “variations” (De Keersmaeker’s term; see De Keersmaeker and Cvejić 2012, 29) adds and transforms movements that are similarly abstract:

- a jump in Variation 2 (5:13),

(click to animate)

- a version of rond de jambes en dedans in Variation 3 (6:17),

(click to animate)

- a pirouette and a floor knock in Variation 5 (8:35),

(click to animate)

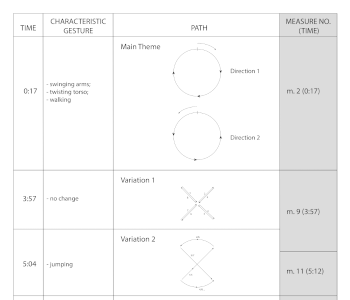

Example 10. Formal diagram of De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

and so on.(41) These movements accumulate over the course of the piece, coming to a head in the virtuosic, breathless sequence of Variation 10 (beginning at 13:20; more on this later). The exact shape and content of each variation, as discussed in De Keersmaeker and Cvejić (2012), are summarized here in Example 10 together with the time markers from the accompanying video and corresponding measures in Reich’s score (in the rightmost column, shaded grey).

[4.20] My decision to view the dancing body as corporeal counterpoint is supported by the observation that De Keersmaeker’s choreography does not emphasize musical structure, opting instead to “develop an independent movement idiom that doesn’t merely illustrate the music but also adds a new dimension to it” (De Keersmaeker and Rosas n.d.). It is curious, for example, that although De Keersmaeker claims to have found in Reich’s music an invitation to dance, except for the 7+5 grouping in the beginning of Violin Phase, she mostly remains out of sync with the beat. Rather, there are relationships between music and dance that can be considered emergent, meaning that they cannot be known by examining the component media in isolation, but instead fall out of the dynamic interaction between sound and body. Each medium seems to have its own pulse. (Here I use the term to nominate a general sense of regularity, rather than the more narrowly construed musical tactus.) Note, for example, the very beginning (1:17ff): walking along the circumference of the circle during the exposition of what I called the main theme, De Keersmaeker falls in and out of synchrony with the steady beat of the music.

[4.21] Indeed, structural convergences and divergences—moments in which structural changes between the two media are correlated and uncorrelated, respectively—create a space in which dance and music can “operate collaboratively in the construction of meaning” (Duerden 2007, 76). The dancer’s movements at times exhibit a high degree of independence from the music in terms of small-scale tempo and duration, while also remaining sensitive to broader articulations of musical form, such as the emergence of new resulting melodies. “As the piece continues,” remarks De Keersmaeker, “I try, by changing the movement, to emphasize the melody that emerges out of the process. In that way, some variations do react to the changes in the music. But choreographically speaking, the accumulation in the music is treated differently, because I am alone” (De Keersmaeker and Cvejić 2012, 36). The union of bodily and auditory channels in the aesthetic event brings to the surface elements of music that may ordinarily remain submerged, while obscuring aspects that typically focus the listener’s attention.

[4.22] De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase contains structural convergences at both global and local levels. Global convergence occurs when changes between “prolongation regions” (Cohn 1992) in the music are correlated with changes from one dance variation to the next. Several examples of this can be found throughout the piece (see Example 10): the coincidence between the beginning of Variation 1 in the dance and m. 9 in the music (3:57); Variation 3 and m. 12 (6:17); and Variation 8 and m. 20 (11:12). By contrast, local convergence designates moments in which individual gestures are synchronized with individual sound events. As described above, the twisting pattern at the beginning of the piece is one example of such convergence, where the dancer clearly articulates the musical phrase into 7 and 5 eighth notes.

[4.23] Structural convergences are juxtaposed with moments of structural divergence, which occur when structural changes in the two media are not correlated with each other. Once again, this can take place at both local and global levels, and a sense of correlation can either be attenuated, or altogether nonexistent. On the one hand, attenuation can be seen when the transitions from one dance variation to the next are imprecisely coordinated with transitions in the music. One example occurs at the onset of m. 19. By the time De Keersmaeker marks the transition from Variation 6 to Variation 7 by standing in the middle of the circle and swinging her leg (10:04), we are well into the shifting B–E double-stop that characterizes m. 19 (9:50). On the other hand, after the 7+5 twists at the beginning of the dance, there seems to be a general lack of coordination on the local level between the musical pulse and the rhythms of the body.(42)

Chrono-technics

[4.24] The flexible and dynamic structural inclinations between the dance and the music serve as the source for the emergence of the temporal trajectory of De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase. The ease with which her basic vocabulary of movements enfolds the audience in the aesthetic events is instrumental to this emergence, because it allows the viewer to enact the very processes and techniques through which it happens—through which time itself comes into being.

[4.25] Imagine that, perhaps imitating De Keersmaeker’s choreography, you are walking in synchrony with a musical beat: two pulses—the auditory and the corporeal—fusing into a single event. Each new step you take participates in this fusion in two ways. On the one hand, it reinforces the sense of regularity by maintaining the pulse. In other words, it adds to the already accumulated feeling of regularity established by all the previous steps; it keeps the pulse going while simultaneously constituting it as such—as a pulse (in contrast to, say, an irregular sequence of steps). On the other hand, each step also creates a bodily response that is absolutely new, one that emerges from a field of pure possibility in which synchronization is but one option. Walking is not just a realization of the potential inherent in the situation, but an active response to the contingencies of the environment (for example, an uneven surface, a wobble in the body’s sense of balance, and so on). Coordinating bodily actions with sound is an achievement that results in the emergence of a unique temporality that both transforms existing patterns and generates new ones. Let us take a closer look at this twofold process.

[4.26] Our ability to synchronize movements with an external signal by entraining to its periodicity is a visible diagnostic not just of how we understand sonic processes but also of our socio-cultural belonging more generally. Although it has recently been found to hide a pernicious side (Gelfand et al. 2020), synchronization is usually seen as a positive contribution to the wellbeing of a social group because it disciplines individual bodies and helps to obviate the tendency to freeload. Numerous studies have focused on the ways in which entrained behavior appears to increase empathy, a sense of social belonging, altruism, pleasure, and so on.(43) Broadly speaking, then, the reinforcement of regularity that happens when walking is synchronized with an external auditory pulse can be seen as a form of commitment to existing regimes of temporality. Such regimes include the habits of thought with which we conceptualize the process of abstracting objects from flux—for example, events that we call beats—and the techniques and technologies that serve as material support for these habits—for example, metrically organized music.(44) Though immaterial and ephemeral, beat and meter, together with the entire constellation of related concepts, exert powerful social pressures, to the point where change is incorporated into extant temporal schemata without much resistance, for instance when we claim that we somehow feel compelled to synchronize our walking with the music. Our commitment to these regimes means entrusting them with the authority to delimit the possibilities for conceptualizing change, or conceptualizing the ways in which we are able to enact the process of abstracting temporal objects from incessant flow. As we place ourselves in the custody of those regimes, compliance with their strictures ensures access to cognitive and bodily schemata that make interpersonal encounters and life in general more efficient.

[4.27] Our enactment of gestures and movements that comply with existing temporal frameworks constitutes what I call chronopraxis. Describing praxis, Steven Vogel (2017) writes that “to be a living human being is to be active in the world, and to be active in the world means at the same time to change the world. All activity is transformative activity; the doings or practices the human beings engage in are constantly altering the world around them” (20; emphasis original). Chronopraxis, despite its grounding in habits of time keeping, thus exhibits a propulsive creativity that pushes against the boundaries of temporal regimes. Each technically or technologically supported enactment of temporal regularity, for example, modifies the collective knowledge that undergirds the praxis of synchronizing our movements with sound. As Jonathan De Souza (2017) points out, habits are not immutable: they are subject to change through learning and unlearning, through use, reuse, and misuse. They are not re-enactments of stored motor programs, but instead contain within them mechanisms for adjusting to the contingencies of the environment. In consequence, every action we perform—each step we take in the walking scenario—engenders irreversible changes in how we conceptualize the category to which this action belongs—categories such as beats, meter, and others that we extricate from the sonic process with which we are synchronizing.

[4.28] Chronopraxis transforms current methods of producing and reproducing temporal relations. In the case of movement synchronized with music, this transformation may involve the articulation of different periodicities in different parts of the body. For example, we might decide to add a clap on every other beat, thus articulating a backbeat (familiar from popular music). Or we might occasionally skip a beat, creating a syncopation. Or we might even clap on every beat, step on every other beat, and bob our head twice as fast as we clap, producing a multi-layered rhythmic texture typical of many musical interactions. Importantly, transformation works within an existing system, making it possible to discover relationships between some new entity (for example, a musical event) and the method by which this entity came to be. Transformation thus implies that the temporal relations which are constituted through chronopraxis are ontologically the same, having merely undergone a change of form.

[4.29] In the case of De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase, structural convergences emphasize not just the correspondence between the music and the dance, but also the sense of transformation from one musical state or bodily gesture to the next. They reveal, in other words, how an operation performed on a single entity results in a change of this entity’s formal properties. Because they create a conjoined rhythm which, in turn, facilitates predictability and aids in recollection on the part of the viewer/listener, structural convergences highlight the continuity between movements, linking them into a succession no part of which can be extricated from the others. As such, these points expose the chronopraxial dimension of Violin Phase by folding both the music and the gesture into a temporal regime that imparts special value to synchronicity. The practice of synchronized activity shows up as a technique that organizes events relative to a common time axis.

[4.30] Yet the exercise of walking along with the music is also a manifestation of another dimension of chrono-technics: chronopoiesis. Chronopoiesis designates the becoming of time, specifically its constitution both by the moving body and by the world with which this body copes in skillful ways. Here, I am drawing on the relational ontology developed by the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1968), who argued that each present is necessarily open to the contingencies of the future.(45) Each present contains within it an inherent absence, an incompleteness that demands fulfillment. This absence imbues the present with infinite potential which is actualized by a skillfully acting body. The present thus actualizes the future by crystallizing this potential into a singular event. Komarine Romdenh-Romluc, Merleau-Ponty’s ardent commentator, puts it succinctly: “Through one’s activity, the future—what is presented implicitly as yet to come—becomes present and the present becomes past—what is presented implicitly as having been” (2010, 249). Chronopoiesis is my term for this activity, a gesture or movement which, as it is enacted, brings into existence something that is absolutely unknowable in the darkness extending beyond our perceptual horizon. It is a generative gesture that enacts novelty, an improvisational bodily propulsion that constitutes the then of then-a in the <a, then-a> string explicated by John Rahn (1993) in his essay on repetition.

[4.31] Chronopoiesis takes place in a small temporal gap between ourselves and the world, a gap that allows time to be enacted in the first place (Dufourcq 2014). This gap is the very basis of our relationship to the world—it designates our position as perceiving agents by creating an asynchrony between ourselves and this world. Such asynchrony is necessary if there is to be a perceiver perceiving a percept, as Merleau-Ponty illustrated with a simple exercise. As you grasp a nearby object—say, a cup of coffee—touch your grasping hand with the other. Now focus on sensations flowing between the touched and the touching, between the felt and the feeling, between the subject (touching-you) and the object (touched-you).(46) Can you mentally grasp both of them at the once? The inability to do so suggests that the shift in perspective, like between two versions of a multistable percept (e.g., the duck-rabbit illusion), generates a brief moment in which you are neither the subject nor the object, but exist suspended in an interval that is absolute possibility, absolute becoming. It is in this interval that time becomes an ontological reality as possibility/becoming is actualized as a concrete being (subject or object).

[4.32] Where chronopraxis transformed already existing temporal relations, chronopoiesis constitutes the technê of time by generating the absolutely new as the body actualizes the temporal potential of any given moment. Note, in particular, how in the walking exercise there is nothing inherent in each coordinated step that suggests the necessity of continuation, and, while we can imagine that a sequence of synchronized movements will keep going in the foreseeable future, imagination and embodied experience are two drastically different things (Gallagher and Varela 2003). At best, we might feel an absence that demands fulfillment, but the nature of this fulfillment is not a given. Instead, each step that accompanies sound provides the necessary ground for conceiving of a continuity, because it carries the body’s physical energy, and this energy must dissipate or be transferred to another body part. Hence, it is the necessity to dissipate or transfer energy that brings about the next gesture, and the entirety of the bodily situation then determines which sound this gesture will correlate with.

[4.33] In contrast to transformation, the generative dimension of temporality consists of enacting the absolutely unknowable. Knowledge, of course, requires recognition, which implies that the new entity is already in existence when the cognitive capacity is put to use. Accordingly, an entity that is only coming into being cannot be known; it can only be felt as pure possibility, or what Francisco Varela describes as “an openness that is capable of self-movement, indeterminate but about to manifest” (1999, 296).(47) Even while we remain ontologically open to this pure possibility, we balance at all times on the edge of a perceptual, cognitive, and bodily chasm separating the present from the future.

[4.34] The feeling of this precarious balancing act permeates moments in which De Keersmaeker’s dance diverges structurally from the music, giving rise to a sense that the two media unfold along different time axes: the music on a pre-inscribed, technically generated line on which events can be located with mathematical precision using Cohn’s notion of beat-classes, and the dance along a path that meanders in accordance with the indeterminacy and inexactitude of human movement.(48) We can think of the two temporal streams as representing the two stimuli in Merleau-Ponty’s touching/touched experiment above, where one is never quite able to simultaneously capture the two media in a single act of consciousness. Time, in this case, is generated in the gap between them, that brief asynchrony when our attention, driven by the sonic-corporeal counterpoint, switches between dance and music.

Synthesis, repetition, and accumulation

[4.35] Time is inextricable from chrono-technics—techniques and technologies of time keeping and time criticality. We rely on these to fold the uncertainty of the ever-changing world into the sphere of our own temporality. The technê of time is the knowledge we bring into this process of folding-into, knowledge of producing and reproducing temporal relations both within ourselves and between us and the external world. Chronopraxis and chronopoiesis constitute this technê as they synthesize in the moment when the body actualizes potentiality it encounters at the cutting edge of what is knowable.

[4.36] To consider this synthesis, let us return to the walking exercise. No sooner is each time-generating step taken than it is folded into an existing system of knowledge in which it is possible to conceive of it as a transformation of the previous one, and the one before that, and before that, in an unbroken but gradually fading chain leading to the originary step at the start of the sequence. No sooner is the absolutely new enacted than it becomes subsumed within ongoing practice. In this sense, the chronopoietic act is always concealed by the chronopraxial ground against which it unfolds. Our commitment to existing regimes of time is inescapable, even if we make deliberate attempts to break out of them. These regimes are culturally installed upon our kinesthetic experiences, and hence support our relationships with the world and with others (Noland 2009). Even on the bodily level, our actions are shaped and constrained by culture, and while we can push against these constraints to some extent, they never disappear completely (Mauss 1973). Only gradually does our system of chrono-technics expand and transform through the pressures enacted by individual bodies. The counterpoint between poiesis and praxis slowly turns into new practices, coagulating into new regimes that are never completely solidified and yet always retain a semblance of cohesion.

[4.37] This continual synthesis of generative and transformational chrono-technics constitutes the temporality of De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase, an on-the-edge balancing act that, through incessant repetition, coalesces into the dramatic arc of the piece. But this is not the kind of mechanical repetition that Kramer decried as quickly exhausting the work’s information content; instead, it is a vital repetition in the sense articulated by Rahn (1993). In particular, Rahn distinguishes between three forms of repetition, each one characterized by a specific relationship to the goal of the repeated action. The most passive category is what he calls “slavery,” or a kind of repetition that “lacks telos” (50). There is no goal, no trigger that would end the incessant cycle of repetition, not even for its own sake. For Rahn, this is a state of boredom, of “Sartre’s hell” (1993, 50). In his second category, répétition, or rehearsal, the global goal with respect to the repeated gesture is given in advance. “There is already an idea or picture of the whole thing repeated, to which successive presentations are supposed ever more closely to approximate” (ibid.). With a clearly defined end state, rehearsal thus forecloses any possibility of change or growth, imparting only a “wan glow of pseudo-life” to the thing that is repeated (ibid.). Every consecutive iteration is merely an improvement over the previous ones, a zombie-like approximation of “life” or “growth” that amounts to nothing more than “reanimation.” Finally, repetition proper “is repetition within a larger thing whose telos . . . is in the process of being formed” (ibid.). The essence of this repetition is “to point beyond the thing repeated to the thing being formed” (ibid.). In contrast to rehearsal, repetition is alive and focused on opening toward the unknown, “a process of continual transcendence” toward a goal that is always at an arm’s length (ibid.).

[4.38] The goalless boredom that Kramer feared in vertical music is replaced by the vitality of reaching toward a telos that refuses to be specified. Rahnian repetition is essentially a generative process, a process of creating structure, a change of context from which the repeated thing is abstracted and which gives the thing its meaning. It is through this repetition that a musical work becomes a temporally bounded event in which the bodily and affective trajectories of life can play themselves out, again and again. The piece becomes a model for life, or for possible lives, allowing the listener to “live alongside . . . and learn from” the temporal curves emerging from the music (Rahn 1993, 56).(49) In music, each repetition changes the context in which the thing is repeated, thus also changing the goal that is in the process of emergence.(50)

[4.39] Taking up Rahn’s perspective, we find that in the brief moments when De Keersmaeker’s body falls in and out of sync with the music, and corporeal and auditory structures oscillate between convergence and divergence, we become witnesses to that ontological gap through which time emerges. These are moments in which the body is at its most vulnerable as the dancer alternates between breaking out of the “violence” of synchronicity (Ernst 2016) and surrendering to its force. And it is here, in the transitions between structurally convergent and divergent gestures, that we find apertures through which we catch glimpses of the creative power of chronopoiesis, where temporality is still pliable.

[4.40] These moments unveil the body’s chronopoietic potential because they open up a horizon of possibilities before us, the viewers. They reveal the very edge of becoming, an edge full of promise and excitement. Each gesture, each twist of the torso, each resolute step and brazen twirl adds to the overall intensity of the piece in a manner that does not follow an algorithm. This, in turn, is balanced by chronopraxial processes that fold the dancer’s movements into large-scale convergences with the musical structure, altogether creating a flexible and vital rhythm that breathes life into the piece. While it is true that the sequence of events has long been planned, their timing remains indeterminate, hence lacking a sense of inevitability that comes from a technologically imposed temporal mechanicism. Time, no longer an abstract entity that measures the duration of this interaction, itself begins to pulsate, as if set off by the resonance of the repetition. In other words, rather than repeating in time, the dancer’s transitions between synchronous and asynchronous movements trigger the repetition of time.

[4.41] Between the deliberate twists of the opening, and the sudden gasp at the end, De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase is marked by miniature temporal dramas, moments in which the coherence of the relationship between music and dance hangs in balance. Will the dancer succumb to the choronopraxial pressure of the musical time axis? Or will she persist in her emancipation and assume agency through acts of chronopoiesis? Folded into the aesthetic event by virtue of the intimacy that the dancer establishes with us—making us privy to the visual and auditory signs of her exhaustion—we are forbidden from remaining indifferent. These dramas build up momentum in a relentless drive toward the climax in Variation 10 (13:20), which absorbs all of the emotional and physical intensity accumulated over the course of the preceding variations. Note back in Example 10 how by this point in the performance the dancer is no longer bound by the radii, but instead traverses the entire length of each diameter, even several times, as if breaking through the space she herself created. Accompanied by a melody that also spills out of the rigid confines of the basic pattern—a pattern, recall, that through the process of phase shifting had already shrunk to a mere fraction of its former self—she launches into a spirited, vertiginous “gambol that ends in a near sob” (Kisselgoff 1998, 7).

[5] DANCING TIME

[5.1] Reich stated that his phase pieces “turn machine fantasies into human events” (quoted in Auner 2017, 80). And yet, what do machines fantasize about? Do their fantasies unfold in accordance with the unquestionable logic of algorithmic operations? Or, like us in our own dreams, do they imagine that which is beyond imagination itself, resonating with temporal perturbations and chronopoietic wobbles, glitches that expose the possibility of nothing short of life? Of course, there is no temporal regime more repressive and implacable than that which takes technological operationality as the source and model for human behavior. Reich found the blurred lines between electromechanical and human performance to be “a liberating and impersonal kind of ritual” (Reich 2002b) but it is necessary to filter his comments through the historical context of the late 1960s, when the public enthusiasm for space- and cybernetics-driven American technophilia was yet to be dampened by the industrial technological interventions in the Vietnam War (Goodyear 2008). Today, when anxieties about the adverse impact of cybernetic interference in human lives—for example, in the form of surveillance technologies, or the AI-based criminal justice system (Benjamin 2019)—are at an all-time high, the childlike excitement of merging human and technical media in the act of performance seems quaint, at best.(51)

[5.2] I see the walking and twisting figure of the dancer as an antidote to the technological entrapment posed by such a merger. De Keersmaeker’s Violin Phase, according to Brian Seibert (2014, C2), was “an acknowledgement of the unavoidably human dancer in the mechanical process.” Her body is inscribed with the miniature temporal dramas that constitute the piece’s temporal trajectory. The dancer not only enacts the chrono-generative power of the human gesture, but invites us to participate in the event, and to take it with us as we leave the performance space. This gesture is infectious, addictive, even seductive in its apparent familiarity and lexical transparency. The audience embodies the very chrono-technical acts that unfold on stage, pushing and pulling and stretching the temporal regimes that, perhaps only for a moment (but maybe that is enough?), expand under the pressure of novelty. This is vividly underscored by the differences in timing between De Keersmaeker’s and Hashimoto’s performances, as seen in Example 1. The two dancers enact different pulses and create different moments of structural inclinations, signaling that it does not matter when exactly these occur, only that they occur. With each live performance, the temporal trajectory will be different, but each one will draw on its own terms to set up a dramatic contrast with the other movements of Fase, where there is a direct correlation between musical and kinesthetic pulse streams.

[5.3] Yet, as Gyselinck (2018) astutely observes, it is not just the dance that touches the viewer: it is the “pleasure that may very well be akin to that of a reliving of the choreographer’s initial discovery.” Pleasure is contagious as it condenses around attentive viewers and listeners. The viewer, brought into the circle of intimacy drawn with painstaking effort—whether literally on sand or only in their imagination—cannot remain indifferent to the rainbow of emotions engendered by the spectacle. In fact, the feeling, like the dance, does not end with the final convulsive gesture, but spills out and contaminates other encounters with this music. The price of indulging in emotional flights may be high for some, perhaps not enough for others, but we all must be ready to pay. Watching De Keersmaeker’s dance in different contexts, under different conditions (some analytical, others more leisurely), has profoundly changed how I listen to Reich’s Violin Phase when I hear it on its own. The same waves of intensity, of sliding in and out of synch with the pulse, of building momentum until the final melody bursts through the thick surface, have infected my auditory experience. The mechanically unfolding process no longer seems so mechanical, and I can begin to imagine what machines might fantasize about.

[5.4] The French philosopher Jean-Marie Guyau wrote that “the idea of time is the product of an accumulation of sensations, muscular efforts, and motives put in order with some difficulty” (Guyau 1988 (1890), 113). In this article I have argued that De Keersmaeker’s choreography can be seen as a proto-theory—a fantasy, an awe-inspiring spectacle—of Reich’s Violin Phase, in which the dancer does precisely that: she draws on the chronopraxial and chronopoietic dimensions of the technics of time to meticulously construct a dramatic temporal arc of her dance out of the accumulation of sensations and muscular efforts that her viewers are invited to co-create. Crucially, unlike the dualist framework proposed by Kramer, the generative and transformative powers of a moving body are not diametrically opposed endpoints of a continuum, but ingredients that we ourselves combine to enact the temporal trajectory of life.

[5.5] “What is at stake in a turn to corporeality in music analysis?” Answering his own question, Chris Stover (2016) suggests we “turn away from certain quantifiable aspects of sonic materiality (pitches, chords, rhythms, formal designs), towards the ways in which sounds are articulated by bodies in interactive contexts.” In particular, he centers on “affective forces, eventful subject-formation, and performativity as identity.” My aim here has been more modest: rather than refocusing the analytical beam on elements that are in excess of sonic materiality, I hope to have shown how the analytical body itself can shed new light on the structural elements of music, reshaping them in the process of enacting and enfolding time. Even if this body happens to be of a highly trained dancer emotionally engaging her audience in an unfolding aesthetic event, the relationship that emerges between her and us, the viewers, already helps to shift the question from how process music works, to why. In the end, perhaps the contagious nature of this dance is precisely what is needed: the answer is that it works because our listening and viewing bodies resonate with those of the performers in ways that highlight their creative and transformative powers.

Mariusz Kozak

Columbia University

816B Dodge Hall

2960 Broadway

New York, NY 10027

m.kozak@columbia.edu

Works Cited

Arom, Simha. 1991. African Polyphony and Polyrhythm: Musical Structure and Methodology. Translated by Martin Thom, Barbara Tuckett, and Raymond Boyd. Editions de la maison des sciences de l’homme. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511518317.

Auner, Joseph. 2017. “Reich on Tape: The Performance of Violin Phase.” Twentieth-Century Music 14 (1): 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147857221700007X.

Bear, Laura. 2016. “Time as Technique.” Annual Review of Anthropology 45: 487–502. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102313-030159.

Begbie, Jeremy. 2000. Theology, Music, and Time. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511840142.

Bellon, Michaël. 2018. “Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker Revisits The Debut: Back to the First Fase.” Rosas (website). Accessed December 27, 2019. https://www.rosas.be/en/news/685-anne-teresa-de-keersmaeker-revisits-the-debut-back-to-the-first-ifasei.

Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soz162.

Bergson, Henri. 1971. Time and Free Will. Translated by F. L. Pogson. George Allen & Unwin.

Bernard, Jonathan. 1995. “Theory, Analysis, and the ‘Problem’ of Minimal Music.” In Concert Music, Rock and Jazz Since 1945: Essays and Analytical Studies, ed. Elizabeth West Marvin and Richard Hermann, 259–84. University of Rochester Press.

Bräuninger, Renate. 2014. “Structure as Process: Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Fase (1982) and Steve Reich’s Music” Dance Chronicle 37 (1): 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2014.877273.

Brown, Galen H. 2010. “Process as Means and Ends in Minimalist and Postminimalist Music.” Perspectives of New Music 48 (2): 180–92. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23076970.

Burrows, David L. 2007. Time and the Warm Body: A Musical Perspective on the Construction of Time. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004158702.i-144.

Cohn, Richard. 1992. “Transpositional Combinations of Beat-Class Sets in Steve Reich’s Phase-Shifting Music.” Perspectives of New Music 30 (2): 146–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090631.

Cole, Ross. 2014. “‘Sound Effects (O.K., Music)’: Steve Reich and the Visual Arts in New York City, 1966–1968.” Twentieth-Century Music 11 (2): 217–44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478572214000085.

Cook, Nicholas. 2013. Beyond the Score: Music as Performance. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199357406.001.0001.

Cox, Arnie. 2017. Music and Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking. Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt200610s.

De Keersmaeker, Anne Teresa. 2012. “Dance Can Embody Abstract Ideas.” TateShots (website). Accessed December 27, 2019. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/anne-teresa-de-keersmaeker-0/anne-teresa-de-keersmaeker-fase.

—————. 2017. “Social Bodies: Inside Work/Travail/Arbeid.” Interview with Gillian Jakob. The Brooklyn Rail. Accessed December 27, 2019. https://brooklynrail.org/2017/05/dance/Anne-Teresa-de-Keersmaeker-with-gillian-jakab.

—————. 2019. “‘The Greatest Step of Them All’: Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker Passes On her Fase to the Next Generation.” Interview with Floor Keersmaekers. Go Deeper (blog). Fringearts. Accessed December 27, 2019. https://fringearts.com/2019/07/16/the-greatest-step-of-them-all-anne-teresa-de-keersmaeker-on-fase.

De Keersmaeker, Anne Teresa, and Bojdana Cvejić. 2012. A Choreographer’s Score: Fase, Rosas Danst Rosas, Elena’s Aria, Bartók. Mercatorfonds: Rosas. Distributed by Yale University Press.

De Keersmaeker, Anne Teresa, and Rosas. n.d. “Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich.” Accessed December 17, 2019. https://www.rosas.be/en/productions/361-fase-four-movements-to-the-music-of-steve-reich.

De Souza, Jonathan. 2017. Music at Hand: Instruments, Bodies, and Cognition. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190271114.001.0001.

Duerden, Rachel. 2007. “Dancing in the Imagined Space of Music.” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 25 (1): 73–83. https://doi.org/10.3366/dar.2007.0017.

Dufourcq, Annabelle. 2014. “The Ontological Imaginary: Dehiscence, Sorcery, and Creativity in Merleau-Ponty’s Philosophy.” Filozofia 69 (8): 708–18.

Dufrenne, Mikel. 1973. The Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience. Translated by Edward S. Casey. Northwestern University Press.

Ernst, Wolfgang. 2016. Chronopoetics. Rowman & Littlefield International.

Fase. 2002. Dir. Thierry De Mey, chor. Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker.

Fink, Robert. 2005. Repeating Ourselves: American Minimal Music as Cultural Practice. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520938946.

Fried, Michael. 1998. Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. New ed. University of Chicago Press.

Gallagher, Shaun. 1998. The Inordinance of Time. Northwestern University Press.

Gallagher, Shaun, and Francisco J. Varela. 2003. “Redrawing the Map and Resetting the Time: Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 33 (sup1): 93–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00455091.2003.10717596.

Gallope, Michael. 2011. “Technicity, Consciousness, and Musical Objects.” In Music and Consciousness: Philosophical, Psychological, and Cultural Perspectives, ed. Eric F. Clarke and David Clarke, 47–63. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199553792.003.0030.

Gelfand, Michele J., Nava Caluori, Joshua Conrad Jackson, and Morgan K. Taylor. 2020. “The Cultural Evolutionary Trade-Off of Ritualistic Synchrony.” Philosophical Transactions B 375: 20190432. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0432.

Goodyear, Anne Collins. 2008. “From Technophilia to Technophobia: The Impact of the Vietnam War on the Reception of ‘Art and Technology.’” Leonardo 41 (2): 169–73. https://doi.org/10.1162/leon.2008.41.2.169.

Grandt, Jürgen E. 2018. Gettin’ Around: Jazz, Script, Transnationalism. University of Georgia Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt22nmbs1.

Guck, Marion A. 1994. “A Woman’s (Theoretical) Work.” Perspectives of New Music 32 (1): 28–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/833150.

Guyau, Jean-Marie. 1988 (1890). The Origin of the Idea of Time. Translated by John A. Michon, Viviane Pouthas, and Constance Greenbaum. In Guyau and the Idea of Time, ed. John A. Michon, with Viviane Pouthas and Janet L. Jackson, 93–148. North-Holland Publishing Company.

Gyselinck, Wannes. 2018. “Flipping the Hourglass: Notes on Fase: Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich.” Rosas (website). Accessed December 16, 2019. https://www.rosas.be/en/news/687-flipping-the-hourglas.

Hall, Edward T. 1984. The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time. Doubleday.

Hartenberger, Russell. 2016. Performance Practice in the Music of Steve Reich. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316584965.

Hasty, Christopher. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. Oxford University Press.

Hickey, Michael, and Clive King. 2001. The Cambridge Illustrated Glossary of Botanical Terms. Cambridge University Press.

Horlacher, Gretchen. 2019. “The Embodiment of Piano Phase: De Keersmaeker’s Choreography.” Keynote address presented at the 28th Annual Meeting of the West Coast Conference of Music Theory and Analysis, Vancouver, CA, May 2019.

Hoy, David Couzens. 2009. The Time of Our Lives: A Critical History of Temporality. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262013048.001.0001.

Jordan, Stephanie. 1993. “Agon: A Musical/Choreographic Analysis.” Dance Research Journal 25 (2): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2307/1478549.

Kisselgoff, Anna. 1998. “Slipping In and Out of Phase With Steve Reich.” The New York Times, September 26, 1998, 7.

Kozak, Mariusz. 2020. Enacting Musical Time: The Bodily Experience of New Music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190080204.001.0001.

Kramer, Jonathan D. 1988. The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies. Schirmer Books.

Kriegsman, Alan M. “Ecstasy.” The Washington Post, May 30, 1969, 7.

Leaman, Kara Yoo. 2021. “Dance as Music in George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco.” SMT-V 7 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/smtv.7.2.

Leong, Daphne. 2020. “Embodying Music: Three Questions from Practice.” Paper presented at the Plenary Session of the Annual Conference of the Society for Music Theory, online, November 2020.

Lewin, David. 1986. “Music Theory, Phenomenology, and Modes of Perception.” Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal 3 (4): 327–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/40285344.

Lochhead, Judy. 1982. “The Temporal Structures of Recent Music: A Phenomenological Investigation.” PhD diss., SUNY at Stony Brook.

London, Justin. 2012. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199744374.001.0001.

Margulis, Elizabeth Hellmuth. 2013. On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199990825.001.0001.

Mauss, Marcel. 1973. “Techniques of the Body.” Economy and Society 2 (1): 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147300000003.

McNeill, David. 1992. Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal about Thought. University of Chicago Press.

McNeill, William H. 1997. Keeping Together in Time: Dance and Drill in Human History. Harvard University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible. Edited by Claude Lefort. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Northwestern University Press.

—————. 2012. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Donald A. Landes. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203720714.

Mertens, Wim. 1983. American Minimal Music: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass. Translated by J. Hautekiet, with a preface by Michael Nyman. Kahn and Averill; Alexander Broude.