Review of John Paul Ito, Focal Impulse Theory: Musical Expression, Meter, and the Body (Indiana University Press, 2020)

Jonathan De Souza

KEYWORDS: meter, performance analysis, embodiment, music cognition

Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory

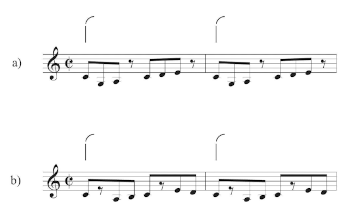

Example 1. Bach, Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin, BWV 1006, Loure, mm. 1–2

(click to enlarge)

Audio Example 1. Bach’s Loure for solo violin, performed by Jascha Heifetz (1952)

Audio Example 2. Bach’s Loure for solo violin, performed by Sergiu Luca (1977)

[1] Example 1 presents the beginning of the Loure from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin. With this movement, there seem to be two main performance traditions. Jascha Heifetz (1952, Audio Example 1) represents one approach, along with Itzhak Perlman (1988), Hilary Hahn (1997), and Midori (2015). Sergiu Luca (1977, Audio Example 2) represents another, along with Suyoen Kim (2011) and Gil Shaham (2015). How can we compare these interpretations? We might start from individual musical elements: Heifetz’s articulation is more legato, Luca’s tempo is slightly faster, and so forth. Alternatively, we might consider the overall character of these performances. As I hear it, Heifetz’s is more stately, while Luca’s is more dance-like, in keeping with descriptions of the loure as a slow gigue (Little 2001). Similarly, one YouTube viewer appreciates Hahn’s interpretation for its “tenderness,” though Shaham’s is “maybe more FUN” (simiamens n.d.). But how can we connect the performances’ musical details to these expressive qualities? John Paul Ito’s new book offers a principled way to integrate these levels, based on performers’ bodily movement. For Ito, these interpretive traditions differ in their placement of focal impulses.

[2] What is a focal impulse? It is a kind of motion, produced by a performer’s body (271). “An impulse,” Ito explains, “is a muscular contraction with a clearly observable moment of initiation” (56). A focal impulse (as opposed to a subsidiary impulse) launches a musical gesture that continues throughout some consequent span. This impulse might create a sound, but it also creates a context for events that follow. Various physical analogies help to clarify the concept: skipping a stone, hitting a racquetball that ricochets around the court, or, in skateboarding, pushing off the surface of the half pipe to set up an aerial trick (63–64). In each case, a focal impulse injects energy into a dynamic system of motion and shapes its possibilities. The book’s central claim, then, is that “motion in performance is organized around and segmented by the focal impulses, with the performer playing or singing from focal impulse to focal impulse” (57)—or, more succinctly, that “some motions play a special role in organizing other motions” (336).

Example 2. Focal impulse placement in two performances of Bach’s Loure for solo violin (78, Example 4.3)

(click to enlarge)

[3] In the Loure, Heifetz’s focal impulses form an uneven long-short pattern, while Luca places them only on strong beats (77–78). Example 2 reproduces Ito’s analysis of their performances. In the example, focal impulses are indicated above the staff: these symbols combine a vertical line, which shows the moment of initiation, with an open-ended slur, which indicates the consequent span. Slower tempos generally require more focal impulses per measure to maintain energy (65), and this helps to account for the rate of focal impulses in Heifetz’s performance. Notes that coincide with focal impulses are often accented through louder dynamics, distinctive articulation (92), or subtle agogic accents that give slightly more time at or just before the focal impulse (87). This is particularly audible in the Loure’s opening anacrusis. For Heifetz, the quarter-note B5 is weighty, sustained with both bow and vibrato. Luca, by contrast, lets go of the note almost immediately, leaving a brief space before the focal impulse on the downbeat. Focal impulse placement, then, brings together differences involving bodily motion, timing, and expression—effectively, the three elements in the book’s subtitle.

[4] How do these elements relate? Ito states that “focal impulse theory is, first and foremost, a theory about the body” (334), suggesting that performing bodies ground both musical timing and expression. Focal impulses interact with meter in subtle ways. They often coincide with strong positions in the metrical grid, but as Heifetz’s long-short pattern shows, they do not always reproduce a particular metrical level or an isochronous sequence of beats. At the same time, focal impulses are expressive. Bodily movements, in this view, do not simply transmit preexistent musical meanings, which would originate in the mind; instead, bodies are an essential source of musical meaning.

[5] This trio of concepts—body, meter, and expression—invites the engagement of a wide readership. Obviously, it will interest music theorists who work on these topics. Ito’s accessible and insightful prose may also inspire performers and music psychologists, especially those who study timing and motor control. Ito’s pedagogical strategy is effective in reaching this wide readership: his book first cultivates experiences of focal impulses—through musical examples, bodily exercises, analogies, and thought experiments—before presenting theoretical terms and symbols. The book’s sound and video examples, in which Ito and numerous collaborators demonstrate varied focal impulses, were particularly helpful.(1) They show Ito in a double role as a theorist and a violist—that is, as a scholar who analyzes scores and recordings, and a practitioner who seeks satisfying creative possibilities. Focal impulse theory, then, supports analysis of and for performance. Throughout his book, Ito aims to be evaluative but not prescriptive. He hopes to enliven performance, listening, and analysis by developing a “new conceptual framework for an old, familiar experience” (343).

[6] The book is organized in five parts. Chapter 1 introduces focal impulses through familiar experiences, such as feeling the music in two or in four. Key examples here involve focal impulses on strong-beat rests. The notes that follow a silent focal impulse have a distinctive rhythmic character, which changes if the rest is replaced by a note. Moreover, Ito claims that musicians often move on the rest in a way that facilitates the subsequent attack. “If we viewed performance as the stringing together of isolated motions,” Ito observes, “there would be no need to move on these rests—after all, when rests do not fall on strong beats, they do not usually inspire motion of this sort” (7). To make the book more accessible to performers and students without extensive theory training (23), Chapter 2 reviews some relevant concepts from music theory and cognitive science: Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s (1983) distinction between meter and grouping, metrical grids, prototype categories, syncopation, metrical dissonance, and hypermeter. Even readers who are already well acquainted with this material will benefit from Ito’s concise and effective presentation, which includes many apt musical illustrations.

Example 3. Ito’s recompositions of a theme from Beethoven’s Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43 (62, Example 3.5)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[7] Part 2 lays out the basics of focal impulse theory. Though Chapter 3 provides “an abstract, general definition” (55), its central goal is again to make the definition experientially relevant, through examples, exercises, and analogies. One strategy for finding focal impulses involves removing notes, a kind of reduction analysis for investigating rhythm and performance: “If all of the notes except those produced by the focal impulses are stripped away, playing the result reveals a simple sequence of motion; the motion needed to play the actual passage is an elaboration of this simple sequence” (62–63). Example 3 presents Ito’s reductive recompositions of a passage from Ludwig van Beethoven’s Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus, op. 43. The original melody involves a constant stream of eighth notes, but Ito filters out notes according to a consistent rhythmic pattern (e.g., Example 3a omits the final eighth note from each four-note group, and Example 3b omits the second eighth note from each group). Examples 3a to 3c eliminate notes that do not correspond to focal impulses, as a means of uncovering this “simple sequence of motion.” By contrast, Example 3d removes notes on the downbeats that are produced by focal impulses. Here the character of the melody changes more substantially, and when performing the passage, Ito feels compelled to move on these active rests. Chapter 5 further examines focal impulses’ sonic traces, which can be detected in the domains of tempo, articulation, microtiming, and dynamics. As Ito notes, often it is hard to disentangle the contributions of these individual musical elements, yet the overall gestalt of each focal impulse pattern is clear. In other cases, he admits that the sonic cues are too ambiguous to determine a particular focal impulse pattern (86). Despite these challenges, his holistic approach in these chapters—combining close listening, visual attention to performers’ motion, and kinesthetic exercises—makes focal impulses perceptible.

[8] Chapters 4 and 6 consider the relation between focal impulses and meter. Usually, focal impulses align with some level of the metrical grid and appear at least on each downbeat. This placement tends to be consistent throughout a passage that has a consistent type of motion. Ito’s theory is based on meter rather than grouping because the former is more regular and hence supports more efficient motor organization. Moreover, focal impulses show how “leaning on and pushing off from things that are stable and predictable makes possible the freedom, variety, and shape of rhythmic performance; without a skeleton to pull against, muscles can be nothing but twitching blobs” (252). But he also considers differences between meter and focal impulses: where Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s metrical hierarchy is abstract and deep, Ito’s impulse hierarchy is physical and relatively shallow, with no more than three levels (195). Though they do interact, focal impulses and metrical processes are distinct.

Example 4. Three types of syncopation, distinguished by their relation to focal impulses (113, Example 7.1)

(click to enlarge)

[9] Chapter 7 asks how syncopated notes push off from focal impulses. Ito proposes three types of syncopation, which are illustrated in Example 4. With vigorous syncopation, focal impulses and syncopated notes are misaligned but they move at the same rate. In this prototypical kind of syncopation, each focal impulse produces only one note. With grounded syncopation, the rate of syncopation is slower than the focal impulses. The syncopated notes align with focal impulses, so they typically feel more restful, heavy, and sustained. Finally, with floating syncopation, the syncopated notes are more rapid than the focal impulses. As their descriptive names show, the three types involve particular impulse patterns but also distinct characters.

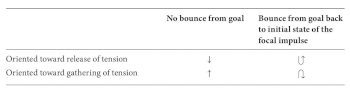

Example 5. Categories of qualitatively inflected focal impulse (172, Table 10.1)

(click to enlarge)

[10] More advanced aspects of Ito’s theory are discussed in Part 3. This section addresses non-prototypical focal impulse patterns, such as those involving asymmetrical meters, conflicts between notated and heard meter, hemiolas, anticipations, and the impulse polyphony that emerges when “members of an ensemble place focal impulses differently” (129). Chapter 9 also introduces secondary focal impulses, which organize lower-level subsidiary impulses but are simultaneously organized by a higher-level primary focal impulse. Yet some of this part’s deepest insights result not from these exceptional cases but from revisiting and deepening the basic principles from Part 2. For example, Chapters 10 and 11 describe qualitative differences between focal impulses. Ito guides readers through a series of physical exercises that involve conducting in two and conducting in one, closely attending to movement, muscular tension, weight, and gravity. This analysis of bodily experience sets up two theoretical oppositions: between downward (tension-releasing) and upward (tension-gathering) focal impulses, and between focal impulses that do not bounce back and those that do (cyclical impulses). Combined, these two oppositions create four focal impulse qualities, represented by arrows in Ito’s Table 10.1 (172, reproduced here as Example 5). As Ito emphasizes, “Focal impulses that gather tension and focal impulses that release tension are hierarchically equivalent: neither governs the other or provides a motional context for the other’s consequent span” (167).

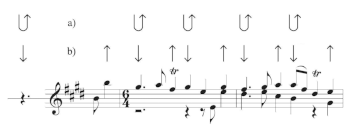

Example 6. Focal impulse quality in two performances of Bach’s Loure for solo violin

(click to enlarge)

[11] Let me illustrate these qualitative differences by building on Ito’s analysis of Bach’s Loure. Heifetz’s long-short pattern involves an impulse cycle. On the strong beats, downward focal impulses release tension, alternating with upward focal impulses that gather tension (172). To feel this distinction, conduct the long-short pattern indicated in Example 6b with a down-up motion, paying attention to the increase in muscular tension as the upstroke resists gravity (in Ito’s image, this is like pulling a bungee cord). The gathering tension of the upward focal impulses, combined with the relatively slow tempo, grounds the deliberate character of Heifetz’s performance. Meanwhile, Luca’s performance involves cyclical focal impulses, which correspond to the standard pattern for conducting in one (see Example 6a). They release tension but bounce back to a state of readiness, so Luca’s performance feels light and springy. Of course, these are not the only possibilities here, and Ito considers less-common options in the Loure (201, Video 11.2). Still, these inflected focal impulses help to explain why Heifetz’s performance recalls a noble procession, while Luca’s suggests joyous leaps. They imply particular kinds of movement or, in Lawrence Zbikowski’s (2017) terms, sonic analogues for dynamic processes.

[12] Part 4 connects the book to other scholarship. Chapter 13 considers its relation to psychology, including music psychology, speech psychology, and motor psychology. A brief history of motor control research in Section 13.4 has fascinating implications for musical practice (e.g., changing tempo also affects movement, so slow practice and fast performance involve different physical actions). Ito believes that some aspects of his theory are empirically testable, and he alludes to relevant experiments in progress. He considers other aspects to be an “extended metaphor” that might have explanatory value as a model, even if it is not literally true. Chapter 14 considers earlier work on music and embodiment, including practically oriented thinkers such as Émile Jacques-Dalcroze (1916) and Alexandra Pierce (2007). Ito notes that focal impulse theory is consonant with Arnie Cox’s (2016) mimetic hypothesis, according to which listeners overtly or covertly mirror performer’s actions. In certain respects, focal impulse theory also resembles Christopher Hasty’s (1997) theory of metrical projection: both emphasize beginnings and treat meter as an active process (270–71). Nonetheless, Ito suggests that projection is more mental and listener-centered, while focal impulses are physical and performative, and he believes that the two theories “are simply talking about different things” (271). This wide-ranging discussion continues in the book’s conclusion.

[13] Part 5 applies focal impulse theory to compositions by Johannes Brahms. Ito showcases the process of developing an analytical or performative interpretation, including false starts and unsatisfying options, trade-offs and personal preferences. While Chapter 15 consolidates the preceding material, it also previews an unpublished corpus study of metrical dissonance in Brahms’s music, sharing selected results (without all of the methodological details that will presumably appear in future publications). Chapter 16 presents analyses of the first movements from Brahms’s op. 120 sonatas for clarinet and piano. The book’s supplementary materials include complete performances, by the author (on viola) and the pianist/theorist David Keep. A full annotated score is also available online, making it easy to conduct along with their interpretation.(2) The dark, restless first movement of the F-minor sonata contrasts with the lush calm of the E-flat-major sonata. Yet they develop and resolve similar metrical conflicts: in both, meter and hypermeter are relatively stable in the first theme, but as the exposition progresses, metrical dissonance and hypermetric irregularity increase. Here Ito offers insight into challenging moments for analysis and performance, while also clarifying metrical and rhythmic aspects of large-scale form and musical narrative.

[14] The book’s conclusion considers dance, ethnomusicological studies of rhythm in music from West Africa, Bali, and Iran, and meter in Western popular music. Ito briefly analyzes focal impulses in three versions of “Stop in the Name of Love,” performed by the Supremes, Jonell Mosser, and the Sons of Serendip. These topics are a departure from the book’s main focus on the Western art music canon from Bach to Brahms, and, while Ito is confident in his analysis of Western popular music, he is uncertain about which aspects of the theory might generalize to repertories from other cultures. On the one hand, the theory addresses basic aspects of movement and timing; on the other, focal impulse theory emerges from a historically specific performance practice, and it is not yet clear how relevant it is to musical practices such as Malian drumming (340). Like experimental testing, cross-cultural research would help to clarify the possibilities and limits of the theory.

[15] Focal Impulse Theory centers temporality in musical embodiment (337), a goal it shares with books such as David Burrows’s Time and the Warm Body (2007) and Mariusz Kozak’s Enacting Musical Time (2019). While it is less philosophical than those texts and does not draw on phenomenological literature, Ito’s contribution is still phenomenological in a general sense (269). That is, his theory is founded on lived experience while also aiming to enrich it. He attends to musical phenomena that are familiar and often taken for granted. Like the phenomenological analysis of everyday life, this work helps us “to rediscover the world in which we live, yet which we are always prone to forget” (Merleau-Ponty 2008, 32). For music theorists, performers, and students alike, this remarkable book will open up new ways of feeling and thinking about meter, expression, and embodied performance.

Jonathan De Souza

Western University

Don Wright Faculty of Music

Talbot College

London, ON N6A 3K7

Canada

jdesou22@uwo.ca

Works Cited

Burrows, David L. 2007. Time and the Warm Body: A Musical Perspective on the Construction of Time. Brill.

Cox, Arnie. 2016. Music and Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking. Indiana University Press.

Hasty, Christopher. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. Oxford University Press.

Ito, John Paul. 2020. Focal Impulse Theory: Musical Expression, Meter, and the Body. Indiana University Press.

Jacques-Dalcroze, Émile. 1916. La rythmique: Enseignment pour le développement de l’instinct rythmique et métrique, du sens de l’harmonie plastique et de l’equilibre des mouvements, et pour la régularisation des habitudes motrices. Vol. 1. Jobin.

Kozak, Mariusz. 2019. Enacting Musical Time: The Bodily Experience of New Music. Oxford University Press.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. MIT Press.

Little, Meredith Ellis. 2001. “Loure.” Grove Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.17043

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2008. The World of Perception. First edition. Translated by Oliver Davis. Routledge.

Simiamens. n.d. Comment on Grandesmusicos, “Gil Shaham - Partita N°. 3 BWV 1006 - Loure.” YouTube video, May 19, 2011. https://youtu.be/_smG-o1lVMc

Pierce, Alexandra. 2007. Deepening Musical Performance through Movement: The Theory and Practice of Embodied Interpretation. Indiana University Press.

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. 2017. Foundations of Musical Grammar. Oxford University Press.

Hahn, Hilary. 1997. Hilary Hahn Plays Bach. Sony Classical SK 62793.

Heifetz, Jascha. 1952. J. S. Bach: Sonatas and Partitas for Unaccompanied Violin. RCA Victor 7708-2-RG.

Kim, Suyoen. 2011. J. S. Bach: Sonatas and Partitas. Universal Music (Korea).

Luca, Sergiu. 1977. Johann Sebastian Bach: The Sonatas and Partitas for Unaccompanied Violin. Elektra Nonesuch 9 73030-2.

Midori. 2015. Bach: Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin. Onyx Classics ONYX 4123.

Perlman, Itzhak. 1988. Sonaten und Partiten. EMI CDS 7 49483 2.

Shaham, Gil. 2015. J. S. Bach: Sonatas and Partitas for Violin. Canary Classics CC14.

Footnotes

1. Supplementary sound and video examples are available online at https://media.dlib.indiana.edu/media_objects/765376507.

Return to text

2. Annotated scores are hosted on their own webpage: https://kilthub.cmu.edu/articles/media/Focal_Impulse_Theory_Supplemental_Online_Scores/13150388.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2021 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4075