Schubert’s Large-Scale Sentences: Exploring the Function of Repetition in Schubert’s First-Movement Sonata Forms

Caitlin G. Martinkus

KEYWORDS: Schubert, musical form, nineteenth-century form, sonata form

ABSTRACT: In this article, I share findings from analysis of first-movement sonata forms composed by Franz Schubert from 1810 to 1828. This work builds on prior studies of nineteenth-century sentences (e.g., BaileyShea 2002/2003, Bivens 2018, Broman 2007, Vande Moortele 2011, and Krebs 2015), offering an in-depth investigation of Schubert’s use of expanded sentence forms. I theorize the typical qualities of Schubert’s large-scale sentences and highlight a particularly common type, in which the large-scale continuation phrase begins as a third statement of the large-scale basic idea (i.e., a dissolving third statement). I present four examples of this formal type as representative, drawn from the C Major Symphony (D. 944/i), the C Minor Piano Sonata (D. 958/i), the C Major String Quintet (D. 956/i), and the D Minor String Quartet (D. 810/i). My analytical examples invite the reader to contemplate the negotiation of surface-level paratactic repetitions with deeper hypotactic structures. These large structures invite new modes of listening; exemplify the nineteenth-century shift away from the relative brevity of Classical precursors in favor of expanded forms; and problematize facile distinctions between inter- and intrathematic functions. This formal type would eventually flourish over the course of the nineteenth century, underpinning many composers’ strategies for formal expansion.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.3.2

Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory

I. Theorizing the Sentence

[1.1] Throughout the nineteenth century, the sentence served as a locus for formal expansion.(1) The format of these sentences varies widely, not only in their individual realizations, but also in terms of how perceptibly they project the sentence paradigm across large-scale units of musical form.(2) Elements of variability include the size of the basic idea, how it is repeated (and how many times), and what markers of continuation function are present.(3) Nevertheless, sentences and larger sentential units (passages that expand the length, but retain the formal functions, of a tight-knit eight-measure sentence) share two fundamental features: proportions and repetition. BaileyShea emphasizes the role of proportion, suggesting that “the sentence has two essential elements,” the first of which is its “short/short/long” proportion (2004, 7). Similarly, one of Callahan’s three criteria for a phrase to be considered sentential is the presence of “typically proportioned” presentation and continuation phrases (2013, 1.2). As for the importance of repetition, Callahan notes that presentation phrases “almost always” contain two basic ideas—that is, an initial statement and its repetition (2013, 1.2) while BaileyShea observes that “without the repetition of a basic idea, there can be no sentence” (2004, 8).

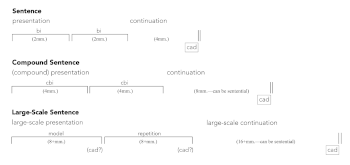

Example 1. Diagrams illustrating the move from sentence to large-scale sentence

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[1.2] Schubert’s large-scale sentences retain many characteristics of the tight-knit, eight-measure sentence, as codified in Schoenberg 1967 and Ratz 1973 and formalized in Caplin 1998. For example, projecting the proportions of an eight-measure sentence (simplified as short-short-long) onto a sixteen-measure unit produces a compound sentence (Caplin 1998, 69). Schubert’s large-scale sentences often double again those proportions, resulting in passages that stretch thirty-two measures and beyond. Critically, in expanded sentences, phrase functions from the eight-measure model are retained, along with their intrinsic markers; see Example 1. Large-scale sentences likewise contain a basic idea (n.b., also a formal function) which, combined with its repetition forms a presentation phrase; this is followed by a continuation phrase. The resulting large-scale sentence can be broken down into three parts: the initial statement of the model (with the function of a basic idea), its repetition, and the large-scale continuation, or LSC.(4)

[1.3] As in compound sentences, we find in large-scale sentences the nesting of formal structures within phrases. Where a compound basic idea (referred to as “cbi” in both text and examples) takes on the function of basic idea in a compound sentence, in a large-scale sentence the model—again, functioning as basic idea—often takes the form of a theme or theme-like unit.(5) From a listening perspective, the degree of nesting can obfuscate the role of a large-scale basic idea within a larger formal structure. A related issue concerns cadences: unlike eight- or even sixteen-measure sentences, large-scale sentences often contain multiple cadential articulations. Rather than interpret these events as cadences of limited scope (as one would treat a cadence ending a four-measure presentation), or as progressions with cadential content but not cadential function (as one would treat a V-I progression in a two-measure basic idea), cadences occurring at the ends of formal units (e.g., if the model and its repetition are sentences) bring about functional ends on lower hierarchical levels of form.(6) In Schubert’s large-scale sentences, these cadences either elide with a repetition of thematic material, contain deviations such as evasion and abandonment, or occur in “wrong” keys. By virtue of Vande Moortele’s “PAC axiom”—the rule that only a subordinate-key PAC is sufficient to end a subordinate theme—these cadences are insufficient to end a subordinate theme (2020, 213).(7) Elision alone does not constitute a deviation; however, in large-scale sentences, when elision is accompanied by a repetition of thematic material, the repetition rhetorically “undoes” the preceding cadence.(8) Taken together, these strategies surrounding cadential articulations delineate hierarchical levels of form, and can be seen and/or heard as cues to shift our perception towards the expanded scale of Schubert’s sentences.

[1.4] Given the issues raised above, one might ask whether the sentence is a useful heuristic to analyze passages comprising upwards of thirty measures. For one, continuation phrases in particular might be considered “too big,” especially sixteen-measure LSCs that can also be read as developmental episodes. The displacement of formal functions that results from the presence of developmental processes into expositional space blurs together supposedly discrete categories of interthematic functions. This slippage is possible because continuations, transitions, and developments share markers of intrinsic functionality: all are defined by loose construction. Furthermore, the hierarchical level on which these functions operate is often distinguished by proportions; as such, the expanded proportions under consideration problematize facile functional distinctions.(9)

[1.5] Another factor complicating the identification of these structures as sentential is the presence of exact repetition, which obscures the overarching hypotactic construction. This issue is particularly thorny in Schubert, given his preference for literal repetition of large-scale basic ideas (which are often structured as theme types), in contrast with later composers such as Wagner and Liszt.(10) Here, analysis comes to the fore as a crucial tool for elucidating these structures by revealing previously unheard configurations which, in turn, guide subsequent listenings. As we will see in Section 4, it is not until the LSC that the listener might comprehend the scope of the overarching sentential design for a given formal unit.(11) Listening with adjusted expectations for proportions and pursuing score-based analysis offers a different listening experience.(12) Repetitions of larger swaths of material invite the listener to attend to the elements of variation that permeate these works. As perceptions of formal scale are reevaluated, the listener is activated as an agent participating in the process of musical form as it “becomes.”(13)

[1.6] Admittedly, these expanded sentential structures are functionally distinct from their tight-knit, eight-measure relatives.(14) My use of the term sentence follows BaileyShea’s assertion that “the sentence is an extremely malleable form; its very nature defies strict definition” (2004, 7). In Schubert’s large-scale sentential structures, the “sentence” serves as a template, a method of organizing formal expansion through the nesting of thematic units, rather than as an immediately perceptible gesture. Keeping in mind some similarities between Schubert’s large-scale sentences and the tight-knit model will make the former easier to recognize. Returning to repetition, Caplin notes how its presence in an eight-measure sentence “helps the listener learn and remember the principal melodic-motivic material of the theme” and demarcates “the actual boundaries of the [basic] idea” (1998, 10). For Caplin, as for BaileyShea and Callahan, repetition is crucial for setting up expectations with regards to grouping structure and proportions. In large-scale sentences, the repetition of the basic idea (model) plays a crucial role in demarcating boundaries—a process that is even more important when parsing expanded formal units. For Schubert, the expectation that a basic idea will take up two or four measures makes repetition at the eight-measure level all the more necessary in order to clarify expanded proportions. On an initial pass, hearing or analyzing, the model and its exact repetition may suggest a compound period; however, this reading is often thwarted, both by cadential articulations (i.e., if the first and second are of equal strength) and the onset of an LSC. Due to the scale at which these sentences unfold, it is the LSC that clarifies how the previous two statements of thematic material function as a large-scale presentation (LSP), rather than an antecedent/consequent pair.

[1.7] In Schubert’s large-scale sentences, the LSC plays a vital role in contextualizing thematic repetitions within larger passages characterized by loose functional, harmonic, and phrase-structural construction: it is the essential “long” in the “short-short-long” sentential paradigm. As such, my analyses focus on Schubert’s strategies for structuring continuations within large-scale sentences, particularly on those continuations that begin as third repetitions of thematic material that become continuational.(15) Before delving into examples of the large-scale sentence in Schubert’s idiom, I first situate his practice in a larger historical context.

II. Precedents and Offshoots

[2.1] Schubert’s expansion of the Classical sentence reflects its new role in the nineteenth century as a vessel of experimentation and transformation. Many nineteenth-century composers, in fact, employed expanded sentential structures, each exploring different approaches. This section begins with consideration of some examples by Beethoven, Liszt, and Wagner—three composers whose sentence technique have been discussed at length in the literature—to contextualize Schubert’s treatment of the large-scale sentence in his instrumental music and illustrate its impact on other composers.(16)

[2.2] Janet Schmalfeldt analyzes three large-scale sentences by Beethoven in her monograph, In the Process of Becoming, specifically, the main theme (mm. 19–45), transition (mm. 45–90), and first subordinate theme (mm. 91–144) from the Kreutzer Sonata, op. 47 (2011, 96–102).(17) For Schmalfeldt, we can understand the structure of the main theme as an outgrowth of the duo-sonata convention, or what she calls “‘equal opportunity’ openings,” in which each instrument is given “a chance to present the initial phrase or phrase-group” (2011, 96).(18) However, Beethoven reframes thematic repetition in this sonata to function as part of something even larger rather than employing an antecedent/consequent structure or, in the case of the main theme, having the repetition “retrospectively become the beginning of a transition” (2011, 96). In all three large-scale sentences, it is the third phrase—following a theme or theme-like unit and its repetition—that brings the form into being. When two initial statements of material are followed by a marked continuation phrase, the first two phrases retrospectively take on the function of a presentation.

[2.3] The repetitions in Schubert’s large-scale sentences to be discussed here differ in at least four ways. First, while they are often subject to variation in some form—e.g., the revoicing of material, the introduction of a new countermelody, or a change in texture—they often cannot be rationalized via extant conventions such as that of the duo-sonata. Second, in using a third repetition of thematic material to initiate the LSC, the sentences I analyze below delay not only the perceptual arrival of continuation function, but also the onset of processes of retrospective reinterpretation that ultimately reveal connections between smaller-scale units of musical form. Third, the fast tempo of Beethoven’s op. 47 makes “the eight-bar repetition” sound “more like a repeated cbi than a repeated presentation” (Schmalfeldt 2011, 98–9). In other words, tempo helps render the form audible. Conversely, the majority of Schubert’s large-scale sentences unfold at slower tempi, retaining the one-to-one relationship between real and notated measures. Fourth and finally is the use of compression in all three large-scale sentences: in the main theme of Beethoven’s op. 47, the LSC is compressed, creating an “effect of urgency” that in Schmalfeldt’s view is necessary to make perceptible its relationship to the massive presentation phrase (96). Similarly, the transition is compressed to twelve measures (as opposed to sixteen). In the first subordinate theme compression occurs in two units: (1) the model is structured sententially but with its repetition compressed: Beethoven eliminates the continuation phrase, creating a structure in which the repetition of the model ⇒ continuation, and (2) the continuation is compressed.(19) Beethoven’s dramatization of the continuation phrase distinguishes it from the large-scale presentation, making it essential to the perceptibility of the overarching large-scale sentence. Experiencing a Schubertian sentence with dissolving third statement is markedly different. This is due to the problematization of continuation function, which results from the scale of and grouping structure within the LSC and which is further destabilized by the treatment of repetition.

[2.4] In Liszt’s large-scale sentences, different types of repetition are used to differentiate between hierarchical levels of form. Within a complex model, Liszt prefers exact repetition of the basic idea; sequential repetition, in contrast, is generally reserved for the repetition of the model itself, thus immediately drawing the listener’s attention to the larger-scale sentential impulse (Vande Moortele 2011). BaileyShea likewise observes the importance of sequential repetition in Wagner’s sentences, many of which “begin with the statement of an idea and an exact, sequential repetition” (2002/2003, 9–12). Sequential repetitions fit squarely with our understanding of hypotactic, sonata-style discourse, which is likely why sequential repetitions are often regarded as imbued with significatory power. In many passages by Liszt and Wagner, this treatment of repetition so strongly implies a subsequent continuation that the listener can almost immediately comprehend the overarching sentential organization.(20) Conversely, in many of Schubert’s sentential designs, repetition seems to mute the underlying sentential impulse. As previously noted, Schubert’s use of exact repetition at the level of the model foregrounds apparent paratactic constructions, obscuring a group’s functional role in the overarching formal unit.(21) Listeners, lacking a clear sense of proportion, may engage closely in a series of shifting reinterpretations as new formal information is revealed through the passage of time. Alternatively, they may suspend their formal expectations, preferring to luxuriate in the composer’s parataxis. Neither of these modes of listening is available when an initial sequential repetition foreshadows the eventual proportions and goal of the large-scale structure. Indeed, this treatment of repetition offers a characteristically Schubertian mode of engagement.

III. Schubert’s Large-Scale Sentences

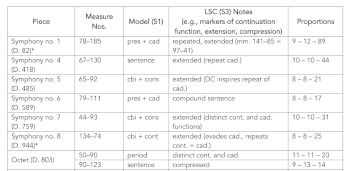

Example 2. Large-scale sentences and related structures in Schubert’s sonata forms

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.1] Among the fifty-two first-movement sonata forms I surveyed, from a variety of instrumental genres, twenty subordinate theme complexes were seen to contain formal units structured as large-scale sentences.(22) The first two columns of Example 2 catalog the works with large-scale sentences and note where each occurs with measure numbers. The example further details the structure of each model (column 3); proposes information regarding the structure of the large-scale continuation, or LSC(23) (column 4); and tracks the proportions of the model, repetition, and LSC components by indicating the length of each section (column 5).

Example 3. Complex model in a Schubertian large-scale sentence (D. 82, mm. 78–86)

(click to enlarge)

[3.2] Most of Schubert’s models are theme types familiar to the Classical style (e.g., sentence, period, or hybrid themes). Only two have a “unique” structure: the Unfinished Symphony, D. 759 and the String Quartet in D Minor, D. 810 employ a compound cbi (cbi + cbi repeated).(24) Example 3, from Schubert’s Symphony no. 1, D. 82, illustrates a prototypical model comprising a relatively tight-knit nine-measure sentence.

Example 4. Sentential LSC with melodic fragmentation (fr) above cadential progression (D. 589, mm. 95–111)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.3] LSCs are less consistently organized. In column 4, I note salient features of each LSC, including prominent markers of continuation function and phrase-structural features, such as extension versus compression. The continuations of most large-scale sentences follow a full repetition of the model. They often display the same markers of continuation function present in tight-knit, eight-measure sentences but increase the scale upon which markers of continuation function unfold.(25) For example, in an eight-measure model, fragmentation (“fr.”) begins at the four-measure level.(26) Example 4, reproducing a passage from Schubert’s Symphony no. 6, D. 589, illustrates this sort of “proper” LSC. In the sententially-structured LSC, fragmentation—with respect to the preceding large-scale presentation—begins immediately. The initiating group is a double presentation (a four-measure presentation that is repeated), thus halving the eight-measure grouping structure established in the model and its repetition. The double presentation is followed by an apparent third statement of the presentation, repeated sequentially(!). After two measures, however, it dissolves; further fragmentation of melodic material supported by an expanded cadential progression in G major (beginning in m. 107) ensues.

[3.4] The scale of these sentences can obscure processes of fragmentation in LSCs, which in turn complicates the assessment of intrinsic functionality in real time. When the model is eight or sixteen measures long, a four- or eight-measure phrase will not register immediately as fragmentation. Rather, such a phrase is more likely to be heard as the beginning of a new theme or theme-like unit, grouping forward with what follows rather than backwards with the preceding large-scale presentation. This perception is amplified when an LSC is structured internally as a compound sentence or some other type of sentential structure.(27) Let us again observe Example 4. Following the repetition of the model, which modulates from G minor to B-flat major, this LSC (mm. 95–111) could initially be heard as a “new theme” in a second, albeit unconventional, subordinate key. In Schubert’s LSCs, model-sequence technique becomes a primary marker of continuation function; this is reinforced by the fact that sequential repetitions are often reserved for LSCs. However, the music’s ability to convey the phrase function of continuation may be undermined by the scale on which these processes unfold. The fact that sequential models are often four measures or more makes it likely that an analyst/listener familiar with the High Classical style will hear the passage as, or in dialogue with, a developmental core rather than a continuation.(28)

Example 5. Large-scale presentation (D. 845, mm. 40–62)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 6. Masked LSC (D. 845, mm. 64–77)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.5] LSCs structured as “proper” continuations need not display all markers of continuation function. As such, they can take many forms. Moreover, other rhetorical features—for example, dynamics, texture, and range—can influence how “continuational” a passage appears to be. Consider the subordinate theme complex in the A Minor Piano Sonata, D. 845, shown in Example 5. Following the varied repetition of mm. 40–50 in mm. 51–63, one could retrospectively hear the entire passage from mm. 40–63 as a large-scale presentation. This is reinforced by the fact that these measures lack cadential closure. Instead, full-measure rests in mm. 60 and 62, often shaped in performance by intense rubato (cf. Uchida 2004), demarcate the LSP.(29) The outset of the LSC is shown in Example 6. The music here, rather than projecting intrinsic markers of continuation function in a manner that imparts the familiar “energy gain” associated with the latter stages of tight-knit sentences, subverts these processes.(30) Rhetorical features contribute to the masking of this LSC. These include a pianissimo recollection of the main theme in the subordinate key in mm. 64–77 and the stark, two-voice texture, which disguises the underlying “proper” LSC marked by fragmentation and sequential repetition.

[3.6] My reading of the subordinate theme complex in D. 845 as a large-scale sentence resolves two analytical problems and opens a hermeneutic window. For one, Schmalfeldt (2011, 122–25) and Vande Moortele (2013, 415), for example, analyze mm. 40–77 as a subordinate theme group: subordinate theme 1 and its repetition comprise mm. 40–63 (my LSP) and subordinate theme 2 spans mm. 64–77.(31) However, it is hard to reconcile the lack of cadential closure at the end of subordinate theme 1 with the analysis of a subordinate theme group.(32) With respect to interpreting the passage as a large-scale sentence, the absence of cadential articulation becomes an asset: it aides in conveying the formal function of presentation. For another, the repetition of “subordinate theme 1” takes on a form-functional role, operating as the repetition of the model in a large-scale presentation. As a result, mm. 40–63 function as a large-scale presentation in relation to mm. 64–77, a compressed LSC that is itself structured sententially (and not as subordinate themes 1 and 2). By means of this large-scale sentence, Schubert deftly manipulates musical time. He uses silence, in conjunction with energy loss, at the end of the LSP to impose a new, cyclical sense of time manifested through the return of main theme material.(33) Through this subtle blending of teleologic and lyric time (i.e., process versus stasis), the subordinate theme complex evokes that Schubertian nostalgia for a home to which we can never return.(34)

IV. Third Repetitions ⇒ Large-Scale Continuations

[4.1] My survey of first-movement sonata forms by Schubert reveals three strategies for initiating the LSC: (1) it can begin as a third statement of the model, (2) it can begin as an apparent closing section, or (3) the repetition of the model can become (⟹) the LSC. Due to the relative frequency of which it occurs in my corpus (see asterisk in Example 2), I will concentrate on the first strategy of beginning the LSC as a third statement of the model. In analyzing this type of large-scale sentence, I explore the intersection between critiques of Schubert’s repetitions and the formal function of repetition in Schubert’s sonata forms. Where past critics have struggled to see past the apparently unnecessary use of repetition, I establish not only the formal function of “excessive” repetitions, but also their role in the expansion of musical forms.

[4.2] Caplin’s taxonomy of hybrid themes rejects the possiblity of threefold statements of the basic idea for the “result[ant] redundancy of material.” (Caplin 1998, 63). He does, however, acknowledge that three basic ideas may appear in subordinate theme groups where loose phrase-structural construction is to be expected (99). Complementing this, recent studies of the sentence have uncovered multiple examples of either complete (Richards 2011, 192) or dissolving third statements of the basic idea in a variety of repertoires (BaileyShea 2004, 11–12; Broman 2007, 121; Callahan 2013, 2.4; Vande Moortele 2011, 137–39).(35) In the corpus I examined, six out of twenty-seven large scale sentences exemplify this formal type; four of these will be analyzed in greater detail as representative samples. Discussion of the Symphony in C Major (D. 944), the Piano Sonata in C Minor (D. 958), and the String Quintet in C Major (D. 956) will establish the relevance of this formal type to Schubert’s idiom. The final analysis, of the String Quartet in D Minor (D. 810), will illustrate the utility of this heuristic in formally complex situations.

D. 944

Example 7. Subordinate theme 1 as large-scale sentence (D. 944, mm. 134–75)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.3] The first subordinate theme of Schubert’s Symphony in C Major, D. 944/i may serve as a prototype for large-scale sentences with dissolving third statements in Schubert’s subordinate themes (see Example 7). Following a non-modulating transition, the E-minor tonality of subordinate theme 1 is striking. The model comprises mm. 134–41. It takes the form of a sentential hybrid ending with a half cadence, followed by two measures of standing on the dominant. In light of the subordinate theme PAC axiom, the half cadence that appears at m. 139 would cause the keen listener/analyst to note that this hybrid functions intra- rather than interthematically. Its repetition begins in m. 142, accompanied by a shift in perceived proportions: the listener is now apt to project a sixteen-measure formal unit, perhaps a compound period in which the repetition ends with a stronger cadence. However, this new expectation must be revised when the repetition ends with a half cadence, in effect redoubling the length of the subordinate theme to a potential thirty-two measures (divided proportionally, 8 + 8 + 16).

[4.4] It is the third iteration of thematic material that ultimately clarifies the function of repetitions within this subordinate theme 1. Although m. 150 begins with the basic idea—implying yet another repetition of the model—it diverges in m. 152 with significant alteration of material. Like the model and its repetition, the internal structure of mm. 150–74 is a sentential, theme-like unit. The first phrase is compressed, leaving only the basic idea; it is followed by a new, expanded continuation phrase which secures a PAC in the second subordinate key of G major (m. 174). In loosening its relationship to the model and ending with a V: PAC, this passage retrospectively reveals the overarching sentential impulse of the entire section, comprising a model, its repetition, and an LSC (supplying continuation and closure). Within this framework, mm. 142–49 are not a superfluous repetition of thematic material; rather, they repeat the model, forming a large-scale presentation, and suggest a new proportional framework to listeners. As this occurs, the function of mm. 150–74 as LSC comes to the fore.

D. 958

Example 8. Model (= loose compound sentence) in the large-scale sentence used to structure the subordinate theme complex (D. 958, mm. 39–53)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 9. Repetition of the model (D. 958, mm. 53–67)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.5] The subordinate theme complex of the Piano Sonata in C Minor, D. 958, is perhaps best known for its commingling of variation and sonata forms.(36) Indeed, the complex can be read as a theme and two variations—the first employing gradatio, the second in the parallel minor (minore).(37) In my analysis, the constituent elements of the nested theme-and-variation set function within a large-scale sentence. While the comprehension of this subordinate theme complex as a large-scale sentence is delayed until well into the LSC, elements of variation present from the theme’s outset direct our attention to the nested theme-and-variation set. In this mode of listening, we are pulled out of the teleological framework of sonata time and into the additive, paratactic realm of variation.(38) My reading of this passage as a large-scale sentence thus serves to supplement, rather than contradict, the variation interpretation, demonstrating how thematic repetitions (typically associated with an additive form) can take on formal functions more typically associated with sonata form, transporting us back into sonata time.

[4.6] A unique feature in the D. 958 theme is the expansion of the model, which leads to considerable complexity, both formally and categorically. The model is a loose compound sentence spanning mm. 39–53 and ending with a III: IAC (see Example 8). The authentic cadences at the end of the model and its repetition potentially obscure the function of these phrases as comprising a presentation. Like D. 944, Schubert deploys an “exact” repetition of the model, suggesting at first an overarching compound period design (mm. 54–67, see Example 9). With the repeat of the III: IAC in m. 67, this possibility is abandoned, as we have yet to achieve a PAC in the subordinate key. Thus, in a manner wholly analogous to D. 944, repetitions with equally-weighted cadences are employed to proportionally expand the subordinate theme.

Example 10. LSC as compound sentence

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.7] The third iteration of thematic material in mm. 67–85 (see Example 10) is structured as a compound sentence, altering the form of the model. Like D. 944, sentential structures govern form-functional logic at multiple hierarchical levels: processes of formal and tonal loosening convey continuation function both locally (the continuation phrase in mm. 76–85) and more globally (within the subordinate theme complex, writ large). Such markers of continuation function include model-sequence technique, increased surface rhythm, fragmentation, and a shift to the parallel mode. Again, it is the third thematic statement that brings the subordinate theme complex to a close with a III: PAC in m. 85 and clarifies the form-functional organization of mm. 39–85 as a large-scale sentence—and along with it, the intrathematic function of internal repetitions.

D. 956

[4.8] The sentential organization of the subordinate theme complex in Schubert’s String Quintet in C Major, D. 956 is easily overlooked for at least two reasons: the model and its repetition comprise expanded themes (each an expanded period), and they end with subordinate-key PACs. While the large-scale sentence structuring this complex (mm. 60–138) is likely not readily apparent, a close reading of the passage highlights the presence of both of the sentence features established at the outset as essential, repetition and proportions.(39)

Example 11. Model (D. 956, mm. 60–79)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.9] The model shown in Example 11 comprises a twenty-measure modulating period, starting in E-flat major (m. 60) and cadencing in G major (m. 79). It may strike some readers as potentially problematic that the model modulates from

Example 12. PAC ending the model vs. elided cadence in repetition (D. 956,

(click to enlarge)

[4.10] The repetition (mm. 81–100) retains the periodic structure and modulatory trajectory of the model; however, an alteration in cadential articulation occurs. Whereas the model ended with a non-elided PAC, the PAC that closes its repetition is elided with the onset of the LSC (see Example 12). In this moment, cadential elision combined with thematic repetition promotes continuity between large-scale presentation and continuation phrases.

Example 13. LSC (D. 956, mm. 100–38)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.11] A third thematic statement is initiated in m. 100 (see Example 13) which, like the LSCs in previous examples, soon charts a new course. This LSC manages to merge all three strategies for initiating a continuation (see Paragraph [4.1]). Measures 100–38 are structured as a large-scale sentence, in which the repetition of the model ⇒ LSC, and the treatment of thematic material—a varied repetition of the model—suggests the onset of a closing section.(42) Continuation function comes to the fore as several processes of formal loosening ensue, among them faster surface rhythm, model-sequence technique, fragmentation, and extension via weak and evaded cadences (e.g., the elided IACs in mm. 112 and 121 and evasions in mm. 125 and 131). For Martin and Vande Moortele, this reopening of thematic space results in a “closing group that becomes a subordinate theme” (2014, 147).

[4.12] Through the articulation of multiple, expanded cadential progressions, the LSC shifts its focus from continuation to cadential function, effectively dramatizing the achievement of the subordinate-theme-ending PAC in m. 138. In retrospect, we are able to read the entire seventy-eight-measure theme complex as a large-scale sentence created through varied repetitions of thematic material. In mm. 60–100, the model and its repetition form a large-scale presentation. The third statement, initiated in m. 100 atop an elided PAC, spans mm. 100–38 and functions as the LSC. It is remarkable that, in spite of the length of its constituent parts, this large-scale sentence retains the short-short-long proportions of a tight-knit sentence nearly exactly—21:20:39.(43)

D. 810

[4.13] The foregoing analyses demonstrated how Schubert employs large-scale sentences with dissolving third statements as a means of organizing subordinate themes and/or theme complexes. Thus far, these sentences have been self-contained formal units, ending with authentic cadences in the subordinate key. My final example of a large-scale sentence governing the organization of a subordinate theme complex comes from the String Quartet in D Minor, D. 810. This formal unit embodies multiple meanings of the term “complex.” The noun form of the word applies to its being composed of multiple, distinct sections, and the adjectival form to the fact these sections resist easy categorization. Prominent thematic repetition at the phrase level and a distinct lack of cadential articulations prevent intrathematic formal units from functioning as part of an overarching subordinate theme group. That said, sentential logic does govern mm. 61–101, a substantial formal unit comprising the middle section of a three-part subordinate theme complex that spans mm. 52–134 in its entirety.(44)

Example 14. Model, with motive x (D. 810, mm. 61–70)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 15. Repetition of the model (D. 810, mm. 71–83)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.14] The middle section of the subordinate theme complex begins in m. 61, following a III: HC in m. 60, which serves as the MC. The expansive passage, which spans mm. 61–101, is almost entirely derived through chaining repetitions of thematic material (Example 14); note that this material is characterized by the one-measure motive marked as “x.” The short nature of the repeated thematic unit (a five-measure cbi) prompts listeners to continually reinterpret their position within the large-scale form taking shape. Take, for example, mm. 61–82, where an extended cbi comprises mm. 61–65, repeating exactly in mm. 66–70. Upon being asked to project from this point, we might guess that the complex will take the form of a compound sentence. Yet this apparent presentation is followed by a third statement of the cbi—mm. 71–75, employing a variant of motive x—which is itself repeated and extended (see mm. 76–82 in Example 15). Harmonically, mm. 71–82 serve as a dominant-functioning repetition of the ten-measure basic idea presented in mm. 61–70. The statement-response repetition in this passage departs from previous examples, which employ exact repetitions within large-scale presentation phrases. The passage in D. 810 is nonetheless analogous to a presentation phrase. Similar to D. 956/i, this large-scale presentation leads to a potential cadence (mm. 82–83); however, it is problematized in a number of ways. First, the bass line in m. 82 is a repeat of mm. 65 and 70, where it does not bear cadential function. Second, the would-be cadential dominant initially appears in first inversion (albeit briefly). Third, the promised III: PAC is elided with not only the onset of the LSC, but also with the onset of a third varied repetition of thematic material (again recalling D. 956/i).

Example 16. LSC (D. 810, mm. 82–102)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4.15] A variant on motive x sounds in the viola in the second half of m. 83. This utterance undermines the sense of closure provided by the PAC on the downbeat of the measure by implying a third repetition of the large-scale basic idea (cbi + cbi). At the same time, compression resulting from the deletion of two beats from the thematic introduction metrically shifts the position of the new idea and displaces the downbeat. This palpable loosening of formal construction immediately suggests the onset of continuation function, which comes to fruition as processes of fragmentation are accompanied by model-sequence technique. The contrasting idea of the original cbi is replaced by further iterations of variations on motive x (see Example 16) to form a model that is liquidated through sequential repetition upward by a third. These markers of continuation function lead to a PAC in m. 90 in the key of the dominant (A), which is again elided with a new continuation: mm. 90–101 signal a possible varied repetition of mm. 83ff. This new continuation brings the entire passage to a close with a half cadence in m. 97, followed by a standing on the dominant. Of note, the LSC in this sentence blurs the boundaries between phrase and theme functions. Indeed, one might say that this continuation becomes a two-part transition as it effects a modulation from the first to the second subordinate key in the exposition.(45)

[4.16] Following the large-scale sentence in mm. 61–101, a second formal unit begins within the complex that comprises mm. 102–34. The form-functional role of this formal unit is unclear in relation to preceding material. Given that it follows an apparent transition, is this a new subordinate theme group? Or is the complex better understood as a trimodular block, in which case this formal unit constitutes TMB3?(46) Regardless, this third group comprises varied repetitions of thematic material introduced in the preceding large-scale sentence; it brings the entire complex to a close in m. 134 with a PAC in the minor dominant (A minor).

[4.17] The subordinate theme complex in D. 810 challenges traditional form-functional analysis. This is due in large part to the number of structural changes incurred as repetitions progress and to the distinct lack of clear cadential articulation between phrases. Viewing it through the lens of the large-scale sentence, however, aids in identifying the organizational framework of a significant portion of the complex’s otherwise unruly design. In cases where a passage’s motivic saturation draws our attention to lower-level units of form, the overarching design is often unclear. It is through this bottom-up approach to analysis that the processual nature of form—and the function of individual units—is revealed. The further advantage of my approach is that it facilitates an alternative, large-scale type of listening. In this mode of engagement, one focuses less on small-scale motivic connections and instead attends to larger-scale processes of repetition and variation.

V. Conclusion

[5.1] The large-scale sentences analyzed in this article push the boundaries of perception unaided by analysis. To reiterate, this is due to Schubert’s preference for models that are at least eight measures long and for exact repetition. Schubert’s strategies for instituting repetition are key in this regard: the time-scale at which these repetitions unfold, the proportions of thematic material involved, and the manner in which repetitions are treated (especially with regard to models) all obscure the function of repetition. A solution emerges, however, when we recognize how the large-scale formal units exemplify Schmalfeldt’s notion of form as process. It is through analysis—and the birds-eye view made available from score study—that that process is revealed. To say it another way: in Schubert’s inimitable sonata forms, repetition drives us as listener and analyst to constantly reevaluate our perceptions of formal scale.

[5.2] Schubert’s use of repetition, sadly, has long attracted criticism of the composer’s instrumental music. Sir George Grove, for example, used relatively mild language to denigrate Schubert’s “often very diffuse” use of repetition (1908, 327; first published in four volumes between 1879 and 1889). Later critiques are more pointed, going so far as characterize Schubert’s repetition technique as explicitly improper and/or symptomatic of misunderstanding sonata form. Writing in 1883, Henry Heathcote Stratham observed: “[Sonata form demands] something more than beautiful melodies . . . [In Schubert’s sonata forms] lovely melodies follow each other, but nothing comes of them; or he repeats an idea without apparent aim or purpose beyond the wish to spin out the composition to a certain orthodox length” (1883, 267). Claims of structural inadequacy in Schubert’s sonata forms long played an undeniable role in his marginalization as a composer of instrumental music.(47)

[5.3] In this article, I participate in contemporary discourse on Schubert (including Fisk 2001, Mak 2006, and Hyland 2016a), recasting his repetitions in a positive light. Specifically, I address repetition from an as-yet unexplored perspective, considering its form-functional role in Schubert’s oeuvre. By showing repetitions in subordinate theme complexes operating intrathematically within the context of an overarching, large-scale sentence, I demonstrate their formal function. My analysis of larger structures, moreover, reveals Schubert’s contributions to the trend of expanded formal units in nineteenth-century sonata forms. Schubert’s large-scale sentences exemplify a shift away from the relative brevity of Classical precursors in favor of expanded forms throughout the nineteenth century. In the unassuming guise of “merely” repeating beautiful melodies, Schubert’s innovations contributed to the rise of large-scale sentences and expanded sentential structures as unique nineteenth-century formal types.

Correction: This article was originally published with an incorrect version of Example 4. The corrected version was uploaded on 8/24/2023.

Caitlin G. Martinkus

School of Performing Arts

Department of Music

Virginia Tech

242-L Squires

Blacksburg, VA 24061

cmartinkus@vt.edu

Works Cited

BaileyShea, Matthew. 2002/2003. “Wagner’s Loosely Knit Sentences and the Drama of Musical Form.” Intégral 16/17: 1–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40214003.

—————. 2004. “Beyond the Beethoven Model: Sentence Types and Limits.” Current Musicology 77 (Spring): 5¬–33. https://doi.org/10.7916/cm.v0i77.5033.

Beeftink, Eildert. 2018. “Tonal Strategy and Phrase Structure in Bruckner: On the Influence of Tonal-Strategic Procedures on Classical Phrase-Structural Models in the Main Theme Groups of the Eighth and Ninth Symphonies.” MA thesis, Conservatory of Amsterdam.

Bivens, Sam. 2018. “Form and Forms in Wagner’s Die Walküre.” PhD diss., The Eastman School of Music.

Black, Brian. 2005. “Remembering a Dream: The Tragedy of Romantic Memory in the Modulatory Processes of Schubert’s Sonata Forms.” Intersections 25 (1–2): 202–28. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013312ar.

—————. 2009. “The Function of Harmonic Motives in Schubert’s Sonata Forms.” Intégral 23 (1): 1–63.

—————. 2017. “Schubert’s Late Sonata Forms and the ‘Lyrical Impulse.’” Paper presented at the Ninth European Music Analysis Conference, Strasbourg, France.

Broman, Per F. 2007. “In Beethoven’s and Wagner’s Footsteps: Phrase Structure and “Satzketten” in the Instrumental Music of Béla Bartók.” Studia Musicologica 40 (1/2): 113¬–31. http://doi.org/10.1556/SMus.48.2007.1-2.7.

Callahan, Michael R. 2013. “Sentential Lyric-Types in the Great American Songbook.” Music Theory Online 19 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.19.3.2.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2004. “The Classical Cadence: Conceptions and Misconceptions.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 57 (1): 51–118. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2004.57.1.51.

—————. 2009. “What Are Formal Functions?” In Musical Form, Forms, and Formenlehre: Three Methodological Reflections, ed. Pieter Bergé, 21–40. Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qf01v.5.

—————. 2018. “Beyond the Classical Cadence: Thematic Closure in Early Romantic Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 40 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mty002.

Caskel, Julian. 2016. “Musical Causality and Schubert’s Piano Sonata in A Major, D 959, First Movement.” In Rethinking Schubert, Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Julian Horton, 207–24. Oxford University Press.

Clark, Suzannah. 2011. Analyzing Schubert. Cambridge University Press.

Dahlhaus, Carl. 1978. “Die Sonatenform bei Schubert.” Musica 32 (2): 125−30. Translated as “Sonata Form in Schubert: The First Movement of the G-major String Quartet, Op. 161 (D. 887).” In Schubert: Critical and Analytical Studies, translated by Thilo Reinhard, ed. Walter Frisch, 1–12. University of Nebraska Press (1986).

Duane, Ben. 2017. “Thematic and Non-Thematic Textures in Schubert’s Three-Key Expositions.” Music Theory Spectrum 39 (1): 36–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtx007.

Fisk, Charles. 2001. Returning Cycles: Contexts for the Interpretation of Schubert’s Impromptus and Last Sonatas. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520225640.001.0001.

Godin, Jon-Thomas. 2014. “Schubert and Sonata Rhetoric.” Paper presented at the Eighth European Music Analysis Conference, Leuven, Belgium, September 20.

Grant, Aaron. 2018. “Schubert’s Three-Key Expositions.” PhD diss., The Eastman School of Music.

—————. 2022. “Structure and Variable Formal Function in Schubert’s Three-Key Expositions.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (1), forthcoming.

Grove, Sir George. 1908. “Franz Schubert.” In The Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 4, edited by John Alexander Fuller-Maitland. MacMillan.

Guez, Jonathan. 2015. “Schubert’s Recapitulation Scripts.” PhD diss., Yale University.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195146400.001.0001.

Hunt, Graham. 2009. “The Three-Key Trimodular Block and Its Classical Precedents: Sonata Expositions of Schubert and Brahms.” Intégral 23 (January): 65–119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41219903.

—————. 2014. “When Structure and Design Collide: The Three-Key Exposition Revisited.” Music Theory Spectrum 36 (2): 247–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtu017.

Hyland, Anne M. 2010. “Tautology or Teleology? Towards an Understanding of Repetition in Franz Schubert’s Instrumental Chamber Music.” PhD diss., King’s College, University of Cambridge.

—————. 2014. “The ‘Tightened Bow’: Analysing the Juxtaposition of Drama and Lyricism in Schubert’s Paratactic Sonata-Form Movements.” In Irish Musical Analysis, ed. Gareth Cox and Julian Horton, 17–40. Four Courts Press.

—————. 2016a. “In Search of Liberated Time, or Schubert’s Quartet in G Major, D. 887: Once More Between Sonata and Variation.” Music Theory Spectrum 38 (1): 85–108. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtv023.

—————. 2016b. “[Un]Himmlische Länge: Editorial Intervention as Reception History.” In Schubert’s Late Music: History, Theory, Style, ed. Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Julian Horton, 33–51. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/doi:10.1017/CBO9781316275887.004.

Hyland, Anne M., and Walburga Litschauer. 2016. “‘Records of Inspiration’: Schubert’s Drafts for the Last Three Piano Sonatas Reappraised.” In Rethinking Schubert, Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Julian Horton, 173–206. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190200107.003.0010.

Krebs, Harald. 2015. “Sentences in the Lieder of Robert Schumann: The Relation to the Text.” In Formal Functions in Perspective: Essays on Musical Form from Haydn to Adorno, ed. Steven Vande Moortele, Julie Pedneault-Deslauriers, and Nathan John Martin, 225–51. University of Rochester Press.

Mak, Su Yin. 2006. “Schubert’s Sonata Forms and the Poetics of the Lyric.” Journal of Musicology 23 (2): 263–306. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.2006.23.2.263.

—————. 2010. Schubert’s Lyricism Reconsidered: Structure, Design and Rhetoric. Lambert Academic Publishing.

Martin, Nathan John, and Steven Vande Moortele. 2014. “Formal Functions and Retrospective Reinterpretation in the First Movement of Schubert’s String Quintet.” Music Analysis 33 (2): 130–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12025.

Martinkus, Caitlin. 2017. “The Urge to Vary: Schubert’s Variation Practice from Schubertiades to Sonata Forms.” PhD diss., University of Toronto.

Ratz, Erwin. 1973. Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre: Über Formprinzipien in den Inventionen und Fugen J. S. Bachs und ihre Bedeutung für die Kompositionstechnik Beethovens. 3rd ed. Universal Edition.

Richards, Mark. 2011. “Viennese Classicism and the Sentential Idea: Broadening the Sentence Paradigm.” Theory and Practice 36: 179¬–224. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41784512.

Rodgers, Stephen. 2014. “Sentences with Words: Text and Theme-Type in Die schöne Müllerin.” Music Theory Spectrum 36 (1): 58¬–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtu007.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. 2011. In the Process of Becoming: Analytic and Philosophical Perspectives on Form in Early Nineteenth-Century Music. Oxford University Press.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1967. Fundamentals of Musical Composition. Edited by Gerald Strang & Leonard Stein. Faber & Faber.

Sisman, Elaine R. 1993. Haydn and the Classical Variation. Harvard University Press.

Stratham, Henry Heathcote. 1883. The Edinburgh Review 158 (324): 162–318.

Taylor, Benedict. 2014. “Schubert and the Construction of Memory: The String Quartet in A minor, D. 804 (‘Rosamunde’).” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 139 (1): 41–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690403.2014.886414.

Tovey, Donald Francis. 1967. The Forms of Music. London: Oxford University Press.

Uchida, Mitsuko. 2004. Mitsuko Uchida Plays Schubert. Recorded 1998. Philips 4756282, 8 compact discs.

Vande Moortele, Steven. 2011. “Sentences, Sentence Chains, and Sentence Replication: Intra- and Interthematic Functions in Liszt’s Weimar Symphonic Poems.” Intégral 25: 121–58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41979583.

—————. 2013. “In Search of Romantic Form.” Music Analysis 32 (3): 404–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12015.

—————. 2016. “Expansion and Recomposition in Mendelssohn’s Symphonic Sonata Forms.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting for the Society of Music Theory.

—————. 2020. “Expansion and Recomposition in Mendelssohn’s Symphonic Sonata Forms.” In Rethinking Mendelssohn, ed. Benedict Taylor, 210–35. Oxford University Press.

Webster, James. 1978. “Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity (I).” 19th-Century Music 2 (1): 18–35.

Wollenberg, Susan. 2011. Schubert’s Fingerprints: Studies in the Instrumental Works. Ashgate. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315607726.

Footnotes

1. The sentence, as a theme type, was first named in Schoenberg 1967 and, more recently, formalized in Caplin 1998.

Return to text

2. For more on how individual composers engaged with the sentence, see, for example, BaileyShea 2002/2003, Bivens 2018, Broman 2007, Krebs 2015, and Vande Moortele 2011.

Return to text

3. For example, BaileyShea notes that many of Wagner’s sentences, “begin with the statement of an idea and an exact, sequential repetition; “he cites the “Faith” theme from the prelude to Parsifal, which “opens with a short basic idea and is followed by a sequential repetition up a minor third” (2002/2003, 9). I return to the importance of sequential repetition of the basic idea in projecting “sentence” later in this article. While BaileyShea (2002/2003) identifies sentences with more typical Classical length and proportions (i.e., 2+2+4), analysts acknowledge the potential for composers to modify proportions, especially within larger structures. For example, Bivens (2018) theorizes a different type of sentence in Wagner’s idiom, the manifold sentence, which greatly distorts the length and proportions of Classical models. These sentences, moreover, incorporate multiple basic ideas (and their repetitions) within an overarching “manifold presentation” before proceeding to the continuation phrase, which is often structured sententially (Bivens 2018, 113–38). Vande Moortele’s investigation of Liszt’s sentences similarly reveals structures that not only range in length from “eight to sixty-two measures” (2011, 132) but also rarely conform to Classical proportions (2011, 131). It not only that sentences are treated differently between composers in respect to Classical precedents, but that individual composers engage with a variety of sentential constructions in their own practice.

Return to text

4. My use of the terms model and repetition echoes the taxonomy codified in Vande Moortele (2011), and stems from the desire to disentangle formal type from formal function when dealing with large-scale units of musical form. For example, a basic idea is both a formal type—“a two-measure idea that usually contains several melodic or rhythmic motives constituting the primary material of a theme” (Caplin 1998, 253)—and function (initiating). As Vande Moortele (2011, 130) notes, “the terminological conflation of formal function and formal type at this level is problematic, because it can lead to correct but awkward statements such as that ‘the basic idea is a compound basic idea (the beginning of which is a basic idea).’” For more, see Caplin (2009) and Vande Moortele (2011, 129–40).

Return to text

5. For more on the term “compound basic idea” (cbi)—a phrase containing a basic idea (bi) and contrasting idea (ci) but does not end with a cadence, thus distinguishing it from an antecedent—see Caplin 1998, 61.

Return to text

6. For more on the distinction between content and function in cadential progressions, and cadences of limited scope in presentation phrases, see Caplin (2004, 81–89). Vande Moortele 2013 discusses the role of cadential articulations in large-scale sentences with periodic presentations. For him, such cadences result from the music’s “expanded scale,” and “give rise to the presence of an additional formal level” (412–13).

Return to text

7. In theorizing the PAC axiom, Vande Moortele summarizes the work of Caplin (1998, 97), as well as James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy (2006, 18).

Return to text

8. Hepokoski and Darcy view elided cadences within Mozartean loops as similarly “undone” by repetition (2006, 84–85).

Return to text

9. While the presence of developmental episodes in Schubert’s sonata forms has been acknowledged in the literature for over half a century, they remain largely undertheorized. Anne Hyland has done the most work in this area recently; she takes her cue from the writings of Tovey (1967) and Dahlhaus (1978). In her 2014 essay, Hyland frames these episodes as dramatic, juxtaposed with the otherwise lyrical contexts in which they appear, ultimately emphasizing the paratactic nature of Schubert’s sonata forms. In her later work (Hyland 2016a), she identifies similar passages in the subordinate theme complex of D. 887 as “sequential episodes” (96). Godin (2014) sees Schubert’s use of these episodes as developing a new sonata form rhetoric; Black (2017) investigates similar processes as “form functional anomalies” but is more concerned with harmony and motive than phrase-structural analysis. These scholars present an alternate reading to the one I present here—that these episodes function as continuations within large-scale sentences. I do not mean to say that these analysts are wrong. My point is that these coexisting interpretations reveal the limits of a theory derived from the proportions of music from the High Classical style when applied to this repertoire in which proportions are expanded.

Return to text

10. See, for instance, Example 4, a large-scale sentence from subordinate theme one of Schubert’s Symphony in C Major (D. 944/i). The model, a hybrid theme (cbi + continuation) that ends with a half cadence is followed by an exact repetition—together, these two iterations of thematic material function as the large-scale presentation.

Return to text

11. In this article I maintain a distinction between listener and analyst, unless otherwise noted (“listener/analyst”). When I appeal to the listener in my analyses, I am referring to an individual listening to these pieces for perhaps the first time, without the aid of analysis to influence their perceptions.

Return to text

12. One situation in which a listener may take advantage of multiple exposures to musical materials is through the expositional repeat, or the return of thematic material in the recapitulation. Both situations afford another chance for the listener to perceive the overarching organizational framework.

Return to text

13. For more on the notion of becoming (denoted by ⇒ in both the text and my analyses) and form-as-process in the nineteenth century, see Schmalfeldt 2011.

Return to text

14. The distinction between tight-knit and loose organization is crucial, as this concept defines formal relationships on nearly every level of formal structure; see Caplin (2004, 84–85).

Return to text

15. This is similar to the approach of BaileyShea (2004).

Return to text

16. Parallels with Bruckner come to mind when thinking of formal expansion and the critical reception of repetition. However, little work has been done to investigate form in Bruckner at the phrase level. Beeftink (2018) considers elements of tonality and phrase structure in the Eighth and Ninth Symphonies. He concludes that “the first movements of the Eighth and Ninth Symphonies . . . [employ] Classical phrase structure as a baseline, with a marked tendency towards expansion. The influence of Wagner can be detected in the employment of expanded sentential structures. As a general rule, the Caplinian sentential formal functions (presentation, continuation and cadential) emerge with relative clarity” and the extension of presentation or continuation phrases significantly expand these formal units. Moreover, Beeftink notes that boundaries between continuation and transition can be blurred (as in D. 810/i, which I analyze in section 4) when continuations are “significantly expanded to accommodate the transition to an ensuing theme group” (Beeftink 2018, 49–50).

Return to text

17. The large-scale sentences structuring the main theme and transition have compressed continuations. In the main theme each unit (model, repetition, LSC) is nine measures. In the transition we find proportions of 8 – 8 – 12 (followed by a substantial, eighteen-measure standing on the dominant). In the first subordinate theme, both the repetition of the model and the continuation are compressed, resulting in proportions of 16 – 10 – 28.

Return to text

18. Schubert transplants this duo-sonata convention into works for both large- and small-ensemble, as well as solo instrumental pieces. He often varies the repetition of a model by giving the melody to a different instrument (in larger ensembles) or altering register (on the piano, e.g. what was a melody in the right hand now sounds in the left). For more on revoicing as a technique of variation, and on the role of variation in Schubert’s instrumental music more generally, see Martinkus 2017.

Return to text

19. Regarding the former scenario, Schubert sometimes makes use of such compressions (four of twenty-seven large-scale sentences). For more information, see Table 1 in section 3.

Return to text

20. Sequential repetition takes on a heightened role in conveying sentential functions when continuation phrases are proportionally truncated, abandoning the 1:1:2 scheme so indicative of Classical sentence construction. In Liszt’s sentences this is a common construction. As noted in Vande Moortele 2011 (132): “strikingly, the largest single group is those sentences in which the continuation is cut short to such an extent that it amounts to less than half the length of the presentation.”

Return to text

21. For more on parataxis in Schubert’s sonata forms, see, for example, Mak 2006 and 2010, Clark 2011, Hyland 2010, and Caskel 2016.

Return to text

22. Two points merit clarification. First, while my corpus comprises works composed between 1810–1828, I limited my analysis to first-movement sonata forms of complete, multi-movement works; I did not incorporate overtures or fragments. The resulting corpus therefore includes roughly 50% of the sonata-form movements Schubert wrote. Future studies looking at interior movements and finales would be necessary to fully codify a sentence typology in Schubert’s output; however, this is not the aim of the current study. Second, I maintain a distinction between the terms “complex” and “group” because many of these subordinate themes either lack the necessary cadential closure to distinguish one theme from another, or a subordinate-key PAC is undermined, thus problematizing the status of a given passage as a true group.

Return to text

23. I adopt the term large-scale continuation to avoid confusion among hierarchical levels (e.g., between a sententially-structured LSC with a continuation phrase and the LSC proper). However, some large-scale continuations are structured as large-scale sentences, leading to an LSC with an LSC (e.g., D. 956/i). Fortunately, these are rare.

Return to text

24. Vande Moortele (2011, 134–35) identifies this structure as a double compound basic idea. Double compound basic ideas are classified as “complex models” which “consist of three or more distinct elements” and include a variety of possible realizations (e.g., “a single basic idea combined with a double complementary idea or with two different complementary ideas ... or a double basic idea may be repeated in its entirety”). “Complex models” comprise twenty-two percent of models in Liszt’s sentences. Notably, in Vande Moortele's survey the least common type of model takes the form of a sentence (less than seven percent)—in this case, the opposite of what we find in Schubert’s large-scale sentences, where most models take the form of a familiar theme-type.

Return to text

25. Apart from these “proper” continuations, there are also situations in which the repetition of the model ⟹ LSC (cf. Paragraph [2.3]) and situations in which an apparent closing section ⟹ LSC. I identify these in column 4 of Example 2. These strategies for negotiating the onset of continuation function in Schubert’s large-scale sentences merit further study, as they illustrate the malleability of the sentence as a formal heuristic through the diversity of structures found within a single composer’s catalog. Such a project, however, lies beyond the scope of this article, which focuses on the most common LSC configuration: dissolving third statements.

Return to text

26. I address issues that stem from larger proportions in Paragraph [3.4].

Return to text

27. This phenomenon occurs in eight-bar sentences as well; see BaileyShea (2004), 12–16.

Return to text

28. As previously noted, this has led to the identification of developmental episodes (or the analysis of displaced formal functions) in Schubert’s subordinate themes (cf. note 9).

Return to text

29. This is similar to what happens in the subordinate theme complex in the first movement of the Unfinished Symphony, D. 759. The large-scale presentation is marked by silence, ending abruptly prior to the onset of the LSC, the beginning of which is marked initially by the presence of new material before processes such as fragmentation ensue. For more on this theme complex, see Caplin (2018, 11–14).

Return to text

30. Caplin (1998, 125) notes this sense of increased “dynamic intensity” and “forward drive” with respect to transition, going so far as to state that “the beginning of the transition is often the moment when the movement seems to be ‘getting under way.’” I suggest that, in sharing medial function, similar characteristics are often projected onto continuations.

Return to text

31. Vande Moortele (2013, 415) gives more detail with regards to the analysis of phrase functions in subordinate theme two. He reads it as a large-scale sentence with periodic presentation, even though—given proportions and the premature dominant arrival in m. 65—one might analyze a compound sentence here.

Return to text

32. For Caplin, PACs play a crucial role in demarcating themes within a group, as “each one of these themes ends with a perfect authentic cadence in the subordinate key” (1998, 121).

Return to text

33. Hepokoski and Darcy (2006, 50n23 and 141) offer a hermeneutic interpretation of the main theme’s return following the subordinate theme’s inability to secure a subordinate-key PAC. For them, the subordinate theme is doomed to fail from the outset because of issues surrounding the medial caesura (or possible lack thereof). As the subordinate theme “breaks down in extremis at mm. 59–63” the task of ending the exposition falls on the shoulders of the main theme, which appears in C minor (creating a “lights-out” moment) and achieves a subordinate-key PAC (the “EEC”) in m. 77.

Return to text

34. For more on cyclical readings of Schubert’s use of thematic restatement, see Fisk (2001). Such cyclical elements of Schubert’s compositions have long been framed in terms of memory, recollection, or nostalgia. These studies not only consider the various temporal states engendered by repetition within a work, but also suggest the ability of musical topics to engage with processes of recollection, inducing in the listener a sense of nostalgia. For more, see, for example, the essays published in the special issue of The Musical Quarterly 84, no. 4 (2000), Black (2005), and Taylor (2014).

Return to text

35. Schubert’s use of three-fold statements of the basic idea transcends hierarchy. While my analyses focus on LSCs that are dissolving third statements, he often uses a similar structure for sentential LSCs. See, for example, the LSCs of D. 589/i and D. 845/i. In D. 589/i, Schubert uses sequential repetition to destabilize the apparent third repetition and to distinguish this statement from the preceding presentation phrase.

Return to text

36. This is due in no small part to Schubert’s modeling of this piece after Beethoven’s Thirty-Two Variations in C Minor (WoO 80).

Return to text

37. Following Sisman, I use the term gradatio to describe the gradual process of increasing diminutions from one variation to the next (e.g., variation 1 uses eighth notes while variation 2 employs triplets, etc.). This, along with the use of a minore variant, are indicative of the Classical variation (see Sisman 1993).

Return to text

38. For more on the impact of variation on sonata time, see Hyland 2016a and Martinkus 2017. Regarding parataxis and hypotaxis in music, see Sisman (1993) for an elaboration on the additive, or paratactic nature of theme and variation sets, and Mak (2006), who examines the paratactic nature of Schubert’s lyricism, contrasting it to the hypotactic construction of sonata form.

Return to text

39. A comprehensive form-functional analysis of this piece, published by Nathan Martin and Steven Vande Moortele (2014), considers in great detail moments of retrospective reinterpretation throughout the exposition.

Return to text

40. “The eight-measure sentence begins with a four-measure presentation phrase, consisting of a repeated two-measure basic idea in the context of a prolongational progression [emphasis in original]” (Caplin 1998, 35–9).

Return to text

41. Other analysts have acknowledged the weakness of

Return to text

42. According to Martin and Vande Moortele, mm. 100–137 (what I analyze as the LSC) initially convey closing function due in large part to the relatively static melody and G pedal in mm. 100–104 (2014, 131). Viewing this passage from a textural perspective, in contrast, Duane (2017) analyzes mm. 60–137 in their entirety as the subordinate theme.

Return to text

43. This is sometimes but not always the case with dissolving third stages. For more on proportions in these large-scale sentences, see column five of Table 1.

Return to text

44. Previous analyses of the work have focused on motivic connections, either within the first movement or the piece as a whole. Susan Wollenberg (2011), inspired by the variation movement and the quartet’s allusion to Schubert’s Lied, focuses on “death motives” connecting all four movements of the quartet. Brian Black (2009) investigates coherence in the first movement by exploring harmonic motives that function as referential, modulatory, or gestural. Graham Hunt (2009), 98–201, offers a Formenlehre-style analysis, interpreting this movement as a three-key trimodular block; however, he does not offer a form-functional analysis. Grant (2022) offers a different but complementary form-functional understanding of this subordinate theme complex that situates D. 810 within the context of other three-key expositions. While my analysis considers briefly the outer sections (1 and 3) to contextualize the complex nature of this subordinate theme’s organization, my most detailed remarks regard the sentential organization of the second section (mm. 61–101). Specifically, I illustrate how thematic repetitions at the phrase level concatenate to form a large-scale sentence with dissolving third statement. While this final example is perhaps merely “in dialogue” with the formal type, my analysis demonstrates the explanatory power of the large-scale sentence as an idiomatic means of structuring expansive sections of musical form in Schubert’s oeuvre. Considering the sentential elements of the second section in further detail exemplifies the benefits of a bottom-up analytical approach: I rely primarily on recognizable two- and four- bar functions (basic and contrasting ideas at the two-measure level, cbi at the five-measure level). Unlike previous examples, this section lacks discernible eight-measure theme types.

Return to text

45. For more on the role of modulation as a marker of transition function in Schubert’s sonata forms, see Martinkus 2017 (89).

Return to text

46. For more on the Trimodular Block, see Hepokoski and Darcy (2006), 170–77. Thorough discussions of this formal type in Schubert’s works appear in Hunt 2009 and 2014. Guez posits a reading of D. 810/i as a “deformational trimodular block . . . since its last module is so similar to its first” (2015, 244); Grant (2018) analyzes this piece from the perspective of the three-key exposition, viewing mm. 102–34 as the third tonal area (3TA).

Return to text

47. The practical ramifications of such claims went beyond public perception. In the twentieth century, some editors in musical publishing houses began to take an active role in correcting perceived foibles in Schubert’s instrumental music, posthumously revising his sonata forms (Hyland 2016b, Hyland and Litschauer 2016). In 1918 and 1942, for instance, Harold Bauer published “abridged editions” of the Piano Sonata in B-flat Major, D. 960, in Schirmer’s Library of Musical Classics. Bauer cut 389 bars in the 1918 edition and 406 in 1942; many measures not cut were altered, condensed, or re-written (Hyland 2016b, 75–76).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2021 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

10692