Review of Megan Kaes Long, Hearing Homophony: Tonal Expectation at the Turn of the Seventeenth Century (Oxford University Press, 2020)

Gregory Barnett

Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory

[1] In her detailed and wide-ranging study, Megan Kaes Long shows how the balletto and canzonetta created a novel sense of tonal expectation for late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century listeners—a significant but under-appreciated first step in the emergence of what we recognize as tonality. As she explains, her view of tonality follows the precedents of Edward Dent (1930) and Brian Hyer (2002) and “centers not pitch, but rhythm and meter” (3), so that rhythmically incisive text-setting and metric regularity within a homophonic texture prove crucial to this new tonal idiom. Within a larger historical context, Long links the balletto and canzonetta to earlier homophonic and distinctly tonal-sounding genres of the Renaissance (frottola, chorale, musique mesurée) as similar products of a pervasive humanist spirit. Thus, to simplify Long’s thesis radically: humanism begets homophony begets tonality. In the course of making this larger argument, Long analogizes her repertory’s balanced phrases and clear-cut forms with Renaissance dance, painted miniatures, cartography, and clocks. In sum, the book is richly informative, its scope ambitious, and its subject matter vast. But there are questions that will nag at the reader throughout. First is whether the repertory’s metrically supported tonal style was the result of its poetic texts rather than its association with dancing. Next and more consequential is whether the repertory initiated the style of European music that we recognize as tonal. Was it simply caught up in a larger trend? Ultimately (and enigmatically), Long leaves us wondering: can we even describe this repertory as “tonal”?

[2] Analytical descriptions of this music lie at the heart of Long’s book, which details how partsong composers guide listener expectation throughout these brief pieces. To take an example, Long shows how Orazio Vecchi’s “Chi vuol goder il mondo” (61–63) achieves this guidance by prioritizing metric regularity and harmonic drive. Each line of poetry comprises two measures of music, the rhymed couplet makes four, and the concluding fa-la, refrain balances this with four more. That much comprises the first strain of this binary-form piece, the second half of which follows the same pattern except to add two measures for a concluding line of poetry (thus 8 + 8 + 2). Beyond its clear periodicity, Vecchi’s balletto pulls the listener along by closing the first strain with a half cadence and the second with an authentic cadence. That relationship between the two strains, in which the second completes the first, replicates not only the pairing of phrases in which the second completes the rhyme of the couplet (2 + 2), but also the pairing of couplets and refrains in which the fa-la refrains respond to the couplets (4 + 4).

[3] The significance of Long’s close look at such examples of schematic text-setting—a term from Ruth DeFord (2015) that describes the priority of the text’s structure, as opposed to its emotions, images, and meanings (see Long, 63)—proves vital to our understanding of the relationship between music and text. Partsong composers took poetry from three different languages and hammered it into balanced phrases supported by cadences that establish an underlying tonic-dominant polarity. Because the rhythmicized settings of the verses were crucial in forming the building blocks of partsong forms and their metrically articulated tonal style, Long guides the reader through the details of Italian poetic meter. Italian composers translated the three variations of poetic line—piano (end-line accent on the next-to-last syllable), tronco (on the final syllable), and sdrucciolo (on the antepenultimate syllable)—into stereotyped phrases. As Long explains (65), five-syllable lines often conform to a stock triple-meter pattern (

|

|

) and seven-syllable lines to a stock duple pattern (

) and seven-syllable lines to a stock duple pattern ( 𝄀

𝄀

|

|

). Even readers familiar with the metrics of Italian verse from studies, say, of the madrigal or opera, will gain an appreciation for the way that Italian composers matched poetic lines and their end-line accento comune (common accent) to the partsong’s carefully proportioned musical lines. German and English composers, who wrote in a stress-timed language as opposed to the syllable-timed Italian, adjusted the Italian model with specific musical consequences for each language. Germans adopted a practice of “additive text-setting” (89) whose rhythms and less predictable phrases reflect the multiple stresses of German poetry. English composers, by contrast, followed Italian practice more closely because, as Long argues, they prioritized the tidy periodicity of the Italian partsongs. Thus, they adapted their texts according to Italian poetic meters. Common to the partsong repertory across the three languages, however, is a tonal style wedded to strong metric organization.

). Even readers familiar with the metrics of Italian verse from studies, say, of the madrigal or opera, will gain an appreciation for the way that Italian composers matched poetic lines and their end-line accento comune (common accent) to the partsong’s carefully proportioned musical lines. German and English composers, who wrote in a stress-timed language as opposed to the syllable-timed Italian, adjusted the Italian model with specific musical consequences for each language. Germans adopted a practice of “additive text-setting” (89) whose rhythms and less predictable phrases reflect the multiple stresses of German poetry. English composers, by contrast, followed Italian practice more closely because, as Long argues, they prioritized the tidy periodicity of the Italian partsongs. Thus, they adapted their texts according to Italian poetic meters. Common to the partsong repertory across the three languages, however, is a tonal style wedded to strong metric organization.

[4] As advertised by her book’s subtitle, “Tonal Expectation at the Turn of the Seventeenth Century,” Long’s primary task is to show how strong metric organization creates listener expectation. She does this mainly in Chapters 3–6 of the book’s seven, proceeding from the level of the phrase to the complete form. Thus, Chapter 3 centers on the metrically ordered, harmonically articulated phrase; Chapter 4, the assembly of phrases subordinated to harmonic progressions; Chapter 5, the possibility for experiencing the whole of a partsong in hypermetric terms; and Chapter 6, the crucial role of repeated sections in our unfolding comprehension of the piece and its tonal coherence. Long’s discussions are enriched throughout by analytical tools drawn from a variety of authors: form theory (Caplin 1998), dynamic attending theory (Jones 1992), schematic vs. dramatic text-setting (DeFord 2015), hypotactic vs. paratactic sections (i.e., functionally related vs. merely adjoined—Dahlhaus 1990), and polar vs. solar tonality (i.e., pivoting between tonic and dominant vs. touring a series of related keys—Ratner 1980), to name a few. The framing chapters of Long’s book (1, 2, and 7) treat the broader topics of how we might redefine tonality on the basis of the balletto and canzonetta, how Renaissance print culture facilitated their international dissemination and historical impact, and how they fit into a larger collection of humanist-inspired homophonic genres.

[5] A further feature of this book—and testimony to Long’s deep engagement with the partsong repertory—is the energetic and assured performances by the author and her students that are available as recordings on a website maintained by Oxford University Press. (Take note, OUP, that I had trouble accessing these recordings, because the hyperlink in my PDF copy of the book took me to OUP’s homepage and not to the recordings. A copy-and-paste solution worked, but only for a while.) Long is an engaging writer, too, as reflected in her penchant for catchy titles: for example, “Phrase structure has a voice problem”; “What to expect when you’re expecting (a cadence)”; “Listening to the future.”

[6] Although stimulating, this book isn’t an easy read, because Long sometimes takes a winding route into her material. For example, the title of Chapter 2, “La questione della lingua: Transmission and Translation of Musical Style,” points to the dissemination of the Italian partsong to northern European markets, but it begins with Thomas Morley’s account of an Englishman’s distress over his lack of musicianship, a case of anxiety over musical literacy. This leads to a discussion of the important place of amateur performance in English society and then to the repertory that Englishmen performed. That repertory included the madrigal and also the lighter partsong genres, as attested by the library of Sir Charles Somerset. Long then briefly describes the emergence of these lighter genres, the canzonetta and balletto, before turning to the main topic of her chapter: the international dissemination of Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi’s popular 1591 and 1594 balletto collections and the region-to-region or language-by-language transmissions of the Italian partsong repertory. The topics flow smoothly, but after ten pages (24–33) packed full of added information (a quick analysis of a Gastoldi balletto, the size of a typical Venetian press run, a review of the printings, anthologies, and contrafacta of Gastoldi’s music), Morley’s anecdote and Somerset’s music collection seem more diversion than proper orientation.

[7] Likewise, Chapter 4, “Halves Requiring Completion,” begins with Shakespeare’s description of ideal lovers, which nicely complements the chapter title. Long then turns to the symmetries in Cesare Negri’s description of Renaissance dancing and, following this, makes the point that the equalized male and female roles in dancing contradicted their otherwise unequal relationship in European society at the time. The focus of this chapter, however, isn’t Renaissance dance. Instead, Long attributes the multilevel symmetries of the balletto not to the influence of dance but to the requirements of schematic text-setting. This is an important point to which I’ll return below; in this chapter, however, the feint toward dancing throws the reader off track. Long’s discursiveness can be charming, but it can also shroud her arguments when their detail and sophistication require a clearer focus.

[8] Further to this point, Long sometimes gets into material that hampers our understanding of the partsong repertory, as in her detour into mensural notation (73–74 and especially 91–96). Briefly summarized, mensural notation prescribes the rhythmic principles of music composed before c. 1600, in which a set of symbols— 𝇈, 𝇋, dot, note colors, and numerical proportions—determines the relationship between note values and the overall flow of music, which is regulated not by barlines but by a pulse known as the tactus. Long’s interest in Renaissance mensural practice centers on the correlation she sees between the tactus and the periodic cadences of the partsong repertory. The problem is that the mensural principles as invoked by Long don’t explain the characteristics of partsong rhythm. Her discussion instead illustrates how phrases, sections, and forms are founded on repeated accentual patterns that function like measures within metrically (and not mensurally) conceived rhythm (91–92):

Composers rely on musical accent to render poetic meter and verbal accent intelligible, while at the same time poetic meter and verbal accent contribute to regular musical accent. This apparent tautology in fact illuminates the process by which metrical regularity came to be established first as a norm and ultimately as a value in homophonic secular music. But schematic text-setting yields not only metrical regularity, but also metric hierarchy [original emphasis].

Further on, she describes the “new metrical style of the partsong repertory” (96):

In homophonic songs with schematic text-setting, verbal, poetic, and metrical accents are all coordinated and occur at regular periodicities. Deviations from these periodic norms are not uncommon, though they reveal a respect for the underlying metrical grid as often as they suggest a distance from it.

[9] This sounds like a description of periodicity founded upon musical meter, and not mensural notation, which raises the question of what is explained by mensural principles and terminology, or how they are significant. This question is underscored by the mensural notational symbols in Long’s musical examples that she never explains. For example, tripla (3) and sesquialtera (

[10] If her discussion of mensural rhythm doesn’t illuminate balletto and canzonetta style, it is also not central to the overall thrust of Long’s book, which rightly seizes upon the metric regularity and periodicity of the partsong repertory as defining and historically significant features. The connection of those features with the tonal style of this music on the one hand and its distinctive technique of syllabic text-setting on the other are the more crucial topics. They flesh out Long’s larger perspective summarized above (humanism begets homophony begets tonality), in which the Renaissance humanist Zeitgeist prioritized musical settings of vernacular poetry, and the syllabic, homophonic, and metrically regular settings of the partsong repertory forged a new tonal style.

[11] Yet, in the final chapter of her book, Long retreats from this argument (251):

Attentive readers have probably noted that I’ve been quietly agnostic about declaring the balletto (or the frottola, musique mesurée, the cantional) a tonal repertoire.

Long’s assertion of agnosticism clearly contradicts my summary above, but I’d argue that the contradiction originates in her book. In stating her aims early on, she writes (22): “I situate the international circulation of these partsongs within a broader culture of early modern translation to show how tonality emerged in distinct ways in different regions.” In her introduction to Chapter 3, she adds (57), “homophonic partsong reveals that text plays a signal role in the emergence of tonality—but the words are both much more important and much more banal than Dahlhaus and Chafe suppose.” Still later (165), Long wonders whether the “clearer harmonic progressions” heard by earlier scholars in the balletti of Morley but not Gastoldi or Hassler would therefore exclude Gastoldi’s and Hassler’s from being tonal. Her answer there was no, Gastoldi and Hassler would not be excluded because “they illustrate how different rhetorical, harmonic, and even formal approaches can accommodate tonal expectation.”

[12] Up until the end of her book, Long is unambivalent: this is tonal music. Her seeming change of heart is more a matter of caution about calling anything “tonal” and thus inadvertently defining “non-tonal” (or worse, “modal”) by omission from what she describes as a “membership repertory” (251). This is an understandable caution, but it sows unnecessary doubt about the rhythmically articulated tonal style of the partsong repertory. More specifically, it muddles our understanding and appreciation of how Gastoldi, Hassler, and Morley could each adopt a system of pitch organization that is both distinct and tonal, which we perceive from Long’s expert description of how they individually channel tonal expectation (149–65).

[13] Long’s hesitancy over calling the balletto a tonal repertory reveals the bigger problem of tying tonality and its historical emergence so closely to the strong metrical organization of the homophonic partsong. To do so raises the question of whether the fugue—which is not homophonic, not metrically regular or evincing a similar periodicity, not necessarily texted, and not typically exhibiting a polar tonal plan, but often a solar one—didn’t also follow a path toward clearer tonality between, say, a Frescobaldi ricercar and a Bach fugue. We know that it did by tracing the emergence of the so-called tonal fugue between the late sixteenth and early eighteenth centuries, a period in which, ironically for us, the tonal answer was described as a better exemplification of the modal octave (see Walker 2000, 64–74). Using Long’s own sensitive and nuanced understanding of the history of tonality, we can appreciate the different ways that different genres created and guided our sense of tonal expectation. Indeed, it seems that she recognizes as much when she distinguishes a “fully mature” tonal practice of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that was “divorced from its initial homophonic environment” (248).

[14] The main business of Long’s final chapter, “Humanism and the Invention of Homophony,” is otherwise the gathering up of diverse homophonic repertories—frottola, musique mesurée, and Lutheran chorale—to argue for an underlying humanist, vernacular-text-centered impulse that subsumes these repertories along with the balletto. Ultimately, Long argues that tonality itself is a byproduct of humanist “intellectual and cultural innovations that transformed sixteenth-century artistic thought” (204). Her case rests on a series of relationships in which text-setting acts as the prime mover (246):

We might imagine homophonic style as a kind of pyramid: text-setting supports meter, which supports phrase structure, which supports form, and the interaction of these elements may be more or less tonal depending on the sorts of melodic and harmonic frameworks composers employ.

Shortly after, she observes, “the more distant our view of the repertoires, the more homogenous their style. All of them use goal-directed melodies, large-scale harmonic trajectories from V to I, and strophic sectional forms with refrains.”

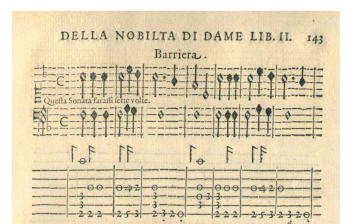

Example 1. Fabritio Caroso, Nobiltà di Dame (1600), 143–44: “Barriera”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[15] This is a compelling argument in its scope, and it is historically plausible, but Long’s account of Renaissance homophony and incipient tonality overemphasizes the influence of text-setting at the expense of the instrumental dance repertory. It also contradicts her earlier explanation of Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi’s designation “per ballare” (for dancing) on 51–54. As she summarizes there (52), “Gastoldi’s rhythmic structure and phrase design draw on dance.” This crucial statement bears illustrating, and just one example of instrumental dance music illustrates its close kinship to the partsong repertory. The piece is a balletto titled “Barriera” (Example 1) that appears in each of Fabritio Caroso’s published treatises (1581 and 1630). Audio Example 1 provides an excerpt. It begins with a Pavane-like movement that exemplifies the metrically reinforced tonal style. Noting that Caroso’s musical examples use barlines, the 24 measures of the opening Pavane comprise six four-measure phrases arrayed across a 16 + 8 binary form before the beginning of the next dance in triple meter (second system on 144). These phrases divide into two-measure units, each defined by its rhythmic motif. Pairs of phrases are coordinated with tonal motion between tonic and dominant, such that the opening strain culminates in an authentic cadence on the dominant, and the concluding strain in an authentic cadence on the tonic. Homophony is assured in these dance pieces either in their lute intabulation or in their two-part homorhythm in traditional notation.

[16] This and similar examples illustrate how the partsong’s homophony and metric-tonal style are intrinsic to instrumental dances, which accommodate the patterns of dance steps rather than poetic lines. Caroso’s description of the dance-steps to “Barriera” shows how the musical features cue the dancers. Their steps take up the opening strain’s sixteen measures (called battute or beats), always in two- and four-measure periods (Nobiltà di dame, 1600, 140, my translation):

progressing together, you will do two passi puntate brevi (each in two beats [i.e., whole-note measures]), four passi semibrevi (each in one beat) and a seguito ordinario (in two beats), beginning these steps with the left foot. Then you will do two saffici (each in a beat), and at the end two continenze (with two beats per continenza), beginning the saffici and continenze with the left foot.

[passeggiando insieme, faranno due Passi puntati brevi di due battute l’uno, quattro Passi semibrevi d’una battuta per passo, un Seguito ordinario di due battute, principiando gli detti Moti con il piè sinistro; poi faranno due Saffici d’una battuta per uno, & al fine due Continenze di due battute per Continenza, principiando detti Saffici, & Continenze col piè destro.]

This single example hardly topples Long’s broader argument, but it does call for more nuance in her text-centered view of partsong tonal style and its origins. Long’s connection of tonality to humanism through the partsong repertory must also make room for Renaissance courtly dancing, which prioritizes the timing of dance-steps rather than the rhythms and phrases of poetry.

[17] Notwithstanding these criticisms, the scope and ambition of Long’s book establish its importance. Readers will come away rethinking big questions: What was the historical significance of “lighter” genres? What was the impact of homophony on listener expectation? And what do we mean when we utter the words tonal and tonality? Long has accomplished this while peering at genres, the balletto and canzonetta, formerly cast into the historiographic margins. Fa la la merriment may flow through this repertory, but Long has shown us, comprehensively and persuasively, just how consequential it is.

Gregory Barnett

Rice University

Shepherd School of Music – MS 532

PO Box 1892, Houston, TX 77251-1892

gbarnett@rice.edu

Works Cited

Caplin, William. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

Caroso, Fabritio. 1581. Il ballarino. Ziletti. Revised 1600 as Nobiltà di dame. Muschio.

Caroso, Fabritio. 1630. Raccolta di varii alli fatti in occorrenze di nozze e festini da nobili cavalieri e dame di diverse nationi. Facciotti.

Dahlhaus, Carl. [1968] 1990. Studies on the Origin of Harmonic Tonality [Untersuchungen über die Entstehung der harmonischen Tonalität]. Translated by Robert O. Gjerdingen. Princeton University Press.

DeFord, Ruth. 2015. Tactus, Mensuration, and Rhythm in Renaissance Music. Cambridge University Press.

Dent, Edward J. 1930. “The Musical Form of the Madrigal.” Music & Letters 11 (3): 230–40.

Hyer, Brian. 2002. “Tonality.” In The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, ed. Thomas Christensen, 726–52. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521623711.025.

Jones, Mari Riess. 1992. “Attending to Musical Events.” In Cognitive Bases of Musical Communication, ed. Mari Riess Jones and Susan Holleran, 91–110. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10104-006.

Ratner, Leonard. 1980. Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style. Schirmer.

Ulsamer Collegium. 1985. “Barriera” by Fabritio Caroso. Terpsichore: Renaissance Dance Music and Early Baroque Dance Music. DG Archiv 41523942.

Walker, Paul Mark. 2000. Theories of Fugue from the Age of Josquin to the Age of Bach. University of Rochester Press.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2021 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3826