Mixture Strategies: An Analytical Framework for Musical Hybridity

Bruno Alcalde

KEYWORDS: hybridity; style; genre; polystylism; mixture strategies; Schnittke; Rochberg; Maxwell Davies; Gubaidulina

ABSTRACT: This article presents a framework to approach musical hybridity, which is understood generally as any combination of musical identities. The framework focuses on the concepts of mixture strategies—perceptible processes of interaction and manipulation of styles, genres, and other identity markers. Mixture strategies are recurrent treatments of disparate musical identities in hybrid music, and not only do they define what the materials are, they more fully explore how these entities are put together. There are four distinct mixture strategies—clash, coexistence, distortion, and trajectory—and each have peculiar characteristics and significations contingent on their use structurally and contextually.

In the article I define and exemplify each of the four mixture strategies in composers from, or related to, the post-1960s polystylistic concert music such as Alfred Schnittke, George Rochberg, Sofia Gubaidulina, and Peter Maxwell Davies. In these works, hybridity itself is foregrounded, and articulates the musical discourse as much, and oftentimes more so, than other musical parameters. Thus, this repertory proves helpful to demonstrate a general framework that can, and should, be applicable to other hybrid repertories. As I discuss the mixture strategies, I will debate the potential interpretive tropes for each. Then, I apply these ideas in interpreting the entire second movement of Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, a work that explores all four mixture strategies. The second movement is then contextualized within the entire concerto.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.28.1.1

Copyright © 2022 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

[1.1] Hybridity refers to the process or result of combining two or more identities, objects, races, languages, or any other clearly bounded concept, be it physical, conceptual, or virtual. At times, it has been a contentious term used in a variety of contexts—from biology to culture—to support political and ideological projects such as those of racial theories in the nineteenth century. As such, the hybrid can be understood as a marker of the impure and unworthy, and denote asymmetrical power relationships, suiting political forces that wish to establish inequalities (Young 1995). But hybridity can also bring positive connotations, creating space for agency and subversion, such as in the empowering effects of creole cultures, for example (Bhabha 1994; Prabhu 2007). Thus, both positive and negative values are assigned to the hybrid category, depending on the conditions and motivations of the mixture, and the perspectives of the interpreter.

[1.2] Despite their contradictions, hybridities can be operationalized through investigating and deconstructing geographic, economic, cultural, physical, sonic, or imaginary boundaries, and tracking the associated biases and values of their contexts. The conceptual building blocks of hybridity are boundaries (segmentation and grouping), identities (labels and values), and difference (consolidation of identity and hierarchy of values). When an object, place, person, or process combines two or more identities, it disrupts the contextually constructed boundaries and—by making them permeable—questions their assigned hierarchy.

[1.3] Hybridity in music occurs whenever there are combinations of disparate identity markers, which are, most of the time, related to the framing capacities of styles and genres. These categories organize engagements with music at all levels—cognitive, sociocultural, economic, political, structural, technical, and aesthetic—and define the identity boundaries that are disrupted in hybrid cases. Styles and genres are the main, albeit not the only, agents of hybridity. The resulting combinations come about in a variety of ways and with varying degrees of prominence of the identities involved, which, for being idealized as a single hybrid environment, share a rich discursive space. Any musical characteristic that triggers an identity for a specific, situated listener can articulate hybridity when it contrasts with another identity in the same or different compositional realm.

[1.4] Many cases of cultural hybridity have been addressed by scholars in critical theory and postcolonial studies, who developed nuanced interpretations and frameworks.(1) Musical hybridity, however, has yet to be thoroughly addressed as a general concept. Specific types of hybridity in music have in fact been approached in the following cases: (1) exoticism and orientalism from the Western perspective, with the important contributions of Bellman (1998), Everett (2004), Locke (2009, 2015), Loya (2008, 2011), and Born and Hesmondhalgh (2000); (2) collage works in the research of Watkins (1994) and Losada (2004, 2008, 2009); (3) mashups in Boone (2011, 2013); and (4) specific composers whose personal style is based on disparate combinations like Charles Ives (Burkholder 1995) and Alfred Schnittke (Dixon 2007; Tremblay 2007; Marsh 2017).(2) This scholarship provides useful insights and an informative set of tools for engagement with, and reflection and interpretation of, hybrid expressions. However, few of them dialog with each other, which results in the impression that hybrid expressions are always sui generis, rather than arising from a common, creative process.

[1.5] The disconnect between scholarly analytical approaches is due primarily to the hybrid expressions’ use of multiple identity categories that are contingent on their context and purpose: a hybrid is only such if the listener recognizes the categories at play. But the disconnect also results from the lack of an embracing interpretive framework that addresses not only the objects, but also the process of hybridity.(3) Few of the works previously mentioned use the term hybrid to describe the combination of identities in the repertory with which they engage, and even fewer of them include the listener as a crucial part in the hybrid process.

[1.6] In this article, I propose a more generalist approach to the understanding of musical hybridity. The framework focuses on processes rather than labels. Not only does it define what the materials are, it more fully explores how these disparate entities are put together.(4) In sum, the framework does not simply objectify and restrict style categories, it reflects on the recurring processes that act upon them.

[1.7] This turn away from labels towards processes is the result of the way the framework foregrounds the experience of a listener. The recognition of musical hybridity is contingent on the individual’s background, familiarity, and purpose in a specific musical environment. However, based on shared knowledge within a community—especially through the notions of styles and genres, common both in mainstream media and academic discourse—many hybridities can be potentially generalized, even with enough room for variability of interpretations. Given that identity categories are idealized as bounded entities, the manner in which they interact, or are manipulated, becomes recognizable as processes, either as the performer or composer acting upon them or as an act of an autonomous work.

[1.8] Within this framework, the processes of interaction and manipulation of styles, genres, and other identity markers are called mixture strategies. Mixture strategies are recurrent treatments of disparate musical categories, their associations, and identities in hybrid music. They are, in fact, patterns of hybridity (a term borrowed from Nederveen Pieterse 2001). In hybrid music, then, styles and genres, as well as other identity markers, acquire structural functions that are coordinated by these general processes of interaction. This study defines four mixture strategies: clash, coexistence, distortion, and trajectory. Each of these strategies has peculiar characteristics and significations contingent on their use structurally and contextually.

[1.9] Because the more generalist approach proposed here addresses hybridity as an expressive and communicational process, it is adaptable to multiple contexts and uses. Furthermore, this processual approach foregrounds an active “style and genre” expressive layer in many different repertories or subtler works that are not usually discussed under these lenses.(5) Within this framework, musical hybridity can be found at several levels and under different guises in all repertories discussed, for example, by the authors in [1.4] (exoticism and orientalism in Charles Ives or collage repertory in Alfred Schnittke) and beyond. Any imagined or imposed boundaries between concert and popular, “serious” and “trivial” music can be potentially crossed.

[1.10] Unlike the way hybridity is usually exemplified, this framework is not restricted to the combination of widely disparate identities. That being said, the communicational potential of hybridity thrives in these more blatantly contrasting cases. Polystylistic music has in the combination of styles and genres, via quotations or allusions, its main agent of discourse. Clear examples can be found in the music of composers such as Alfred Schnittke, George Rochberg, and Peter Maxwell Davies. In these works, hybridity itself is foregrounded, and articulates the musical discourse as much, and oftentimes more so, than harmony, counterpoint, voice leading, or any other parameter or frame. Thus, this repertory proves helpful to demonstrate a general framework engaging with mixtures of styles and genres. Despite the choice of repertory for the purposes of demonstration, the proposed framework can, and should, be applicable to wider repertories as well.

[1.11] In what follows, I will define and exemplify each of the four mixture strategies in excerpts from several works of the polystylistic repertory post-1960s. As I discuss each mixture strategy, I will debate the potential interpretive tropes for each. I will apply these ideas to an entire movement—Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II—a work that explores all four mixture strategies. I will then situate Schnittke’s second movement within the entire Concerto Grosso no. 1, engaging with large-scale choices related to hybridity.

2. Four Mixture Strategies

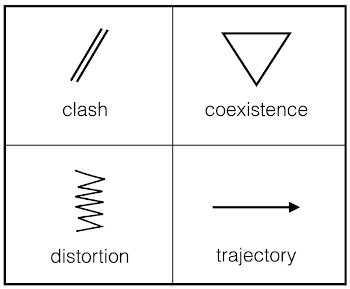

Example 1. Analytical symbols for the four mixture strategies

(click to enlarge)

[2.1] In principle, any hybrid repertory can be approached by four mixture strategies, each with different characteristics, effects, and potential interpretations, which I introduce here. Clash identifies harsh and abrupt juxtaposition or superposition of disparate styles and genres. Coexistence involves more unifying types of combinations. Distortion is the alteration of a recognizable style or genre by some incongruous musical agent. Finally, the compound strategy of trajectory describes cases in which there is a gradual transition from one style or genre to another. The symbols for the mixture strategies, which appear in the analyses below, are shown in Example 1.

[2.2] The interpretable hybrid environments can be of any size. Sometimes they embrace an entire movement, and thereby determine the overall activity of a piece. In other cases, they last a few measures and quickly give way to other hybrid or stylistically stable music as long as a combination of typical style characteristics (style markers) is perceived. These strategies can also be combined creatively, compounding the interpretive possibilities of a hybrid work.

[2.3] These mixture strategies also bring sociocultural and aesthetic associations that can be used to contextualize and interpret these musical moments. Mixture strategies evoke or highlight interpretive trends and tropes related to the categories being mixed, as well as to the way they are being handled compositionally and communicatively. These categories of style and genre interaction take into consideration and identify the more direct affordances of the work, focusing mostly on aurally evident characteristics, and hinting at possible modes of listener engagement with this music.(6) Establishing these processes as theoretical categories can help guide an analysis, but also inform an existing interpretation or mode of listening. These “processual categories” are always being informed by the listening experience, the analytical act, the potential signification of a piece, and its labeling. The categories are not fixed, nor should their boundaries be an obstacle. Rather they serve as tools that suggest a dynamic interpretation of a work.(7)

2.1 Clash

Example 2. Diagram of the clash mixture strategy (juxtaposition and overlap)

(click to enlarge)

[2.4] The first mixture strategy, clash, reveals an increased sense of friction between elements due to a lack of stylistic alignment. This friction is achieved by keeping the different strands structurally and perceptually distinct through the use of different tonalities, tempi, register, texture, instrumentation, and timbre. This friction does not necessarily imply the absence of organization. As we will see, clash can itself sometimes become a form-defining strategy. There are two basic types of clashes in which one unfolds vertically, and the second unfolds horizontally—overlap and juxtaposition clash, respectively (see Example 2).(8)

Example 3. Rochberg, String Quartet no. 3, Part A, Introduzione: Fantasia, mm. 81–95

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.5] An example of overlap clash occurs in the introductory part of George Rochberg’s String Quartet no. 3 (1971). The first portion of Part A, a Fantasia, displays stylistic and generic stability for approximately eighty measures. It has clear non-tonal vocabulary, and relies on bursts of short, repetitive gestures that orient its fragmented thematic identity. At m. 87, however, a chain of major seconds in the violins, derived from the whole-tone collection, is suddenly joined by a tonal chorale texture in B Major, which shows no relation to the previously established non-tonal ideas (Example 3).(9) This superimposition of whole-tone material and B-major chorale not only creates structural friction and instability, but it also contrasts references to two styles: the whole-tone sound can be associated with modernist sonorities, such as those found in turn-of-the-century French music, while the B-major chorale is potentially associated with sacred music by J. S. Bach.

[2.6] Acknowledging Rochberg’s selection of combined materials, and the references they trigger to different periods and styles or genres, is part of an informed listener’s engagement with this brief musical moment. But to arrive at a more nuanced interpretation of this passage, it is important to move beyond simply labeling the distinct references found in this musical moment and engage with the characteristics of the combination. In this case, there is no interaction between the layers other than their superimposition. The identity of each remains intact.

[2.7] The harsh friction among the elements, along with the almost stubborn avoidance of integration to preserve their separate identities, illustrates a clash mixture strategy. The strategy is not merely a structural phenomenon. In choosing to create friction between the styles, Rochberg also influences how one might ascribe meaning to the piece, especially after previous eighty measures of relative stylistic stability. The chorale seems to strive for its own, new, and sudden allotted space, while the whole-tone material in the violin, related more to the non-tonal vocabulary of the piece before that point, reclaims its former prominence. This specific moment of hybridity highlights a conflicted opposition between sacred and secular, distant and close past, as well as the relation of this music with the tonal tradition, all in service of Rochberg’s expressive endeavors.(10)

Example 4. Pärt, Sarabande, from Collage Über B-A-C-H, II

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.8] When separate identities occur successively rather than simultaneously, the strategy is characterized as a juxtaposition clash. In Pärt’s Sarabande from Collage über B-A-C-H (1964), the composer alternates two contrasting environments: (1) the Sarabande from Bach’s English Suite no. 6 in D minor, played by oboe, harpsichords, and strings, and (2) thick clusters in the piano and strings, which are completely disconnected from the previous material (Example 4). These widely divergent musical idioms alternate without any transition throughout the entire piece; they are two different worlds sliced and pasted together, evoking a gap between their associations that remains unfilled. In contrast with the fleeting moment of clash heard in Rochberg’s piece, Pärt’s Sarabande movement is organized entirely by the alternation of these two disparate environments. Thus, its hybridity, characterized by the juxtapositions of the clash mixture strategy, also determines its form.

[2.9] Some juxtaposition clashes often create an articulation between distinct formal sections. In these cases, I call them clash dividers—the change in style or genre is also articulating the form of the work at a higher hierarchical level. A clash divider occurs in Pärt’s example above, which uses the change between materials as a formal articulation. In other cases, clash dividers can be formed by a brief interpolation of unrelated material separating what came before and what comes next. As we will see below, an example of the latter occurs in Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II (Example 25, r.m. 15).

2.1.1 Interpreting Clash

[2.10] The clash strategy highlights discontinuity, displacement or disjunction, and disruption of cause and effect. On the more positive side of the spectrum, clash offers possibilities of commentary, or opening a new layer of discourse, which can elucidate or problematize matters via musical and referential friction of contrasting material, but characteristics of clash might also be interpreted negatively as shock, surprise, mistake, and lack of organization or incoherence.

Example 5. Maxwell Davies, “The Phantom Queen,” mm. 6–10, Clash

(click to enlarge and listen)

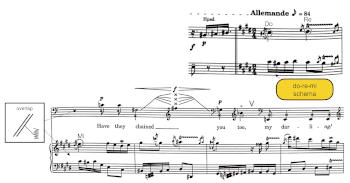

[2.11] For example, perceptions of incoherence and fragmentation of discourse have been historically attached to mental illness, which Peter Maxwell Davies seems to exploit in Eight Songs for a Mad King (1969).(11) Example 5 shows mm. 6–10 of the fifth song in the cycle. The Allemande starts with a do-re-mi schema in

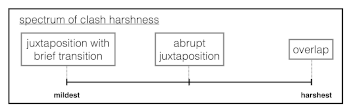

Example 6. Spectrum of clash harshness

(click to enlarge)

[2.12] The spectrum of clash types illustrated in Example 6 shows that each clash has distinct signification potential based on the levels of friction and contrast between disparate musical elements, the specific hierarchy perceived, and the presence or absence of silence or a brief transition. Overlap clashes are necessarily harsh because of the efforts needed to keep both strands separate while sounding simultaneously (see Example 3 by Rochberg, [2.5–2.7], and Example 5 by Maxwell Davies, [2.11]). Clashes through juxtaposition afford a more accessible, milder, kind of hybridity than overlap clashes. In parenthetical uses of juxtaposition clash it is possible to rely on the return to the “original” material as a way of creating a separation between the primary and a secondary layer of discourse. In the Pärt example above (Example 4, [2.8])—a juxtaposition clash that involves the abrupt alternation between disparate materials—this repeated clash can be interpreted as indicating the simultaneity of the two environments.(13) The mildest of juxtaposition clashes are those with some transitioning material or brief overlaps of the contrasting ideas (see Example 11, [2.23]). While this spectrum serves as a general guide, it is important to note that several other factors can further influence the perceived harshness of a specific clash, including volume, texture, and the level of musical contrast between the materials being juxtaposed or overlapped.

2.2 Coexistence

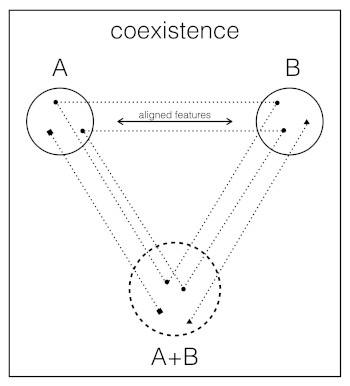

Example 7. Diagram of coexistence strategy

(click to enlarge)

[2.13] Coexistence designates not only existing at the same time or place, but it also implies a smooth, cooperative relationship. In this mixture strategy, contrasting materials are put together by aligning some of their characteristics, while maintaining the identity of their unaligned features, creating only slight friction. This alignment is normally formed by exploiting common traits of each of the style references, which serve as the linchpins of their coexistence; they cohabitate without struggling to assert or keep their separate identities. In this strategy, composers appear to use part of two distinct identities to create something new, forming an amalgam with its own hybrid identity (Example 7).(14)

Example 8. Kagel’s “Ragtime-Waltz” from Rrrrrrr

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.14] Example 8 shows mm. 1–9 of “Ragtime-Waltz,” from Rrrrrrr . . . : 8 Orgelstücke (1980/81) by Mauricio Kagel. The title, evoking two styles, might suggest a clash mixture strategy at first. However, careful examination of the excerpt reveals a more symmetrical combination of the two styles than what is implied by clash. In this case, the prominent triple meter of the waltz is counterbalanced by syncopations, and the melody brings clearer characteristics of a rag through the use of chromaticism and large leaps. Melodically, chromaticism is common both to ragtime and waltz, especially if we think of a Chopin waltz. Here it serves as a “bridge” that integrates the two styles in the piano right hand. The result is not a ragtime superimposed over a waltz in two distinct compositional strands, but rather, an amalgam. It is a ragtime-waltz, where neither of these styles is hierarchically more important than the other. It does not have the harsh friction of a clash because the two identities are combined, with a few concessions from each style, into a third compound identity.

Example 9. Thomas Adès, Overture to Powder Her Face, mm. 6–10

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.15] As shown in Example 9, in the overture to the opera, Powder Her Face (1995), Thomas Adès’s uses timbre to create a nuanced hybrid environment that mixes two popular styles—tango and jazz. Allusions to the tango are clear in the rhythmic and melodic patterns of the accompaniment, as well as in the use of an accordion to recall an instrument characteristic of the style, the bandoneon. Meanwhile, typical voicings of jazz harmony, chromatic runs, and glissandi on brass emphasize the jazz “style field.”(15) The overall emphasis on steady quarter-note accompaniment serves to align the stylistic interplay because of its associations with both the traditional tango rhythmic pattern and jazz. The string ensemble acts as a stylistic mediator, a neutral element that aggregates characteristics of both coexisting style fields. As a result, Adès merges both styles in a way that makes it difficult to disentangle them. He creates an amalgam that involves disparate potential meanings and values, by mixing idealized categories of popular African-American and South-American styles, all of which contrast with the expected royal “seriousness” of the Duchess. In this case, the overture establishes not only the materials that will be prominent throughout the two acts of the opera, but also the connection between stereotypical associations of these combined popular styles with the Duchess’s moral status.(16) Abrupt combinations of disparate materials are, to an extent, expected to occur in a “poutpourri” overture (Vande Moortele 2017, 75–107); however, the superimposition of markers of both styles in a coexistence environment, rather than their juxtaposition, alters this poutpourri effect to a compound identity instead of a sequence of disparate snippets.

2.2.1 Interpreting Coexistence

[2.16] Much of the potential signification in cases of the coexistence strategy directly contrasts with that of clash. Whereas clash highlights discontinuity, displacement, or disjunction between the disparate associations, coexistence can add a sense of coalescence. Thus, it brings unifying, integrative meaning by not relying on separation. As an integrative type of mixture, coexistence has innovative potential usually reflected in a third, compound identity created without much friction. While clash might be interpreted as shock, surprise, mistake, or incoherence, coexistence allows a more prominent sense of productive creativity, an enriched potential for development of the combination. The possibility for any hybrid to open a second layer of discourse as commentary is still valid in the coexistence strategy; however, the nature of the commentary tends to be interpreted differently in these cases. In the clash strategy, the second layer of discourse is mostly a critical, potentially subversive, or political act; on the other hand, coexistence tends to lean toward utopian and pacific cohabitation, albeit not restricted to it.

[2.17] The strategy of clash is associated with a fragmentation of the discourse and, in some specific cases, connected to mental illness (such as in the Maxwell Davies’s Eight Songs for a Mad King above). Coexistence, on the other hand, can be ambiguous; it lacks a defined identity, and can trigger a related sense of inconsistency or omission. In such cases, this ambiguity is interpreted as a negative characteristic. But it can also yield positive interpretations as an original blend that fosters innovation. Coexistence can be used to develop new styles and genres by merging previously established categories into new ones that might—with time, recurrence, and intersubjective acceptance—achieve a status or label of their own.(17)

[2.18] More so than in the clash strategy, where the perceptual separateness of the material is the crucial clue that alerts listeners to the presence of hybridity, examples of coexistence rely heavily on the listener’s recognition of the elements of each style. In cases where one of the coexisting elements is not clearly recognized, the listener may perceive a sense of inaccuracy, inconsistency, or strangeness in the initially recognized style, until the other is also identified. This strangeness and inaccuracy is not the intention of coexistence. It is, however, likely typical of another mixture strategy, distortion.(18)

2.3 Distortion

[2.19] Distortion occurs when a style, genre, or topic is altered by incompatible elements that are not clearly recognized as another category of musical identity.(19) These incongruous elements are clearly foreign to the primary style, but they cannot be identified with a second clear-cut category. Distortion differs from clash or coexistence because only one style or genre can be clearly recognized.

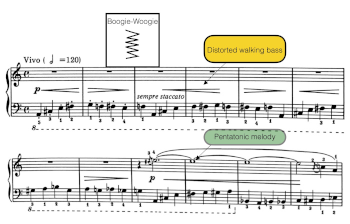

Example 10. Sofia Gubaidulina, Musical Toys, VIII, “A Bear Playing the Double Bass and the Black Woman”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.20] Example 10 shows an excerpt from the eighth piece of Musical Toys, “A Bear Playing the Double Bass and the Black Woman” (1969), by Sofia Gubaidulina. Throughout the entirety of this short piece, the left hand presents a boogie-woogie walking bass, and the right hand plays an A-minor pentatonic-based melody (the

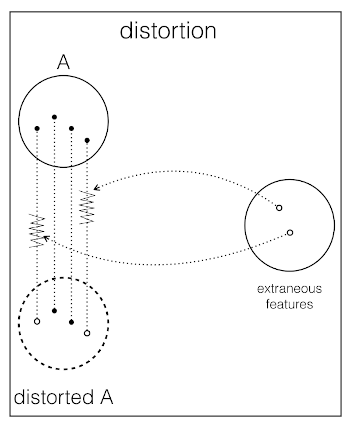

Example 11. Diagram of the distortion strategy

(click to enlarge)

[2.21] Cases of distortion where elements are more symmetrically present can very often be considered as (or confused with) coexistence. The decision is an interpretive one and relies on how strongly and well-defined the distorting agents’ identities are in each case. Since the mixture strategies are interpretive categories, labeling an excerpt as one or the other is less important than the meaningful layers each interpretation can highlight. Generally, in distortion, incongruous elements (the distorting agents) alter a fairly recognizable style or genre; the distorting agents do not establish a clear reference other than that of being external, unfamiliar, and inconsistent with respect to what they are altering. In coexistence, two recognizable identities are combined in a more symmetrical way. Finally, it is also common for distortion to be nested in other strategies, especially coexistence and trajectory, which will be addressed in the next section.

[2.22] Distortion is an instance of hybridity, even though it does not equally treat two distinct identities. The hybridity here is not created by alluding to two disparate styles, but by changing an established category and questioning its identity, thus opening space for instability. Example 11 displays an abstract graphic representation of the strategy, showing how extraneous features act upon a style or genre to create its distorted version.

Example 12. George Crumb, Makrokosmos, volume 3, V, “Music of the Starry Night”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.23] Distortions can also occur via timbre alteration or exaggeration. Example 12 shows George Crumb’s “Music of the Starry Night,” from Makrokosmos, volume 3, no. 5 (1974), which interpolates a direct quotation of the

2.3.1 Interpreting Distortion

[2.24] Baler discusses distortion and its opposite, clarity, as dynamic concepts that move between two poles along “the chain connecting a signifying center with its representation” (2016, 2). Distortion affects this chain by obscuring the connection. “The stylistic resource of distortion should be understood, from this angle, as a manifestation of imbalance (an intrinsic failure of agreement) destined to upset the mechanisms of transmission” (8).(20) In music, incongruities can be achieved by substitution, exaggeration, accumulation, and omission/suppression of typical elements, and often interpreted as “mistakes” of some kind. Due to such common reactions, it is not surprising that distortion tends to be perceived as ironic, with (potentially) comic significations.

[2.25] Both Schumann (2015) and Sheinberg (2000) mention distortion as a means of defamiliarizing. While discussing parody, Sheinberg writes: “‘conventionality’ is apprehended as the reason for our perceiving things without becoming aware of them. Things can be defamiliarized if our attention is attracted to their conventionality, an end that can be achieved by distorting the convention” (2000, 161). This process of defamiliarization is also the subject in Sheinberg’s investigation of the grotesque, a trope often related to hyperbole, and based on accumulation and exaggeration. But the author states that a “grotesque object is . . . never ‘comic,’ but rather ‘ludicrous’; never just ‘unpleasant’, but rather ‘repellent’ or ‘horrifying’” (2000, 210). Thus, the signification potential of the distortion strategy is broadened, even though still restricted to ironic utterances, in Sheinberg’s account. But irony can also be skeptical, not necessarily comical. When combined with other strategies in a hybrid expression, with a diverse range of incongruities, distortion can be located along a wider interpretive spectrum. Distortion can also be assigned negative values, such as in Schumann’s (2015) reading of Stravinsky’s “Soldier’s March,” in which the soldier’s lack of virtues is expressed musically by the composer through distortion.

[2.26] Finally, the complexity and apparent ubiquity of the concept of distortion makes it crucial to distinguish it from cases of coexistence. Coexistence and distortion both rely on ambiguity and incongruity, but these are emphasized differently in each strategy. Coexistence emphasizes the ambiguity—a dual reading derived from a more symmetrical combination of styles or genres. Distortion, on the other hand, emphasizes incongruity, the defamiliarization of one prevailing style or genre, altered with incompatible elements to that idealized category. Whereas some instances can certainly include more than one interpretation, the clear prevalence of one style is indicative of distortion, making critical one’s attention to the hierarchy between the distorted material and the distorting agent.

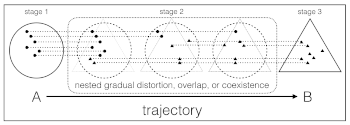

2.4 Trajectory

[2.27] Trajectory is the transformation of a musical environment into a contrasting one through a traceable, gradual process. This strategy can connect any setting, hybrid or otherwise, given that they are momentarily established—one before and the other after the transition process. In its clearer examples, both the initial and ending materials are uniform/stable styles or genres, but contrast with respect to one another—the transition serves to progressively change one into the other. The crucial characteristics of the strategy of trajectory are the perceptible process of somewhat gradual change (especially in large-scale examples), and the traceability of the elements of that change.

Example 13. Diagram of trajectory strategy

(click to enlarge)

[2.28] A trajectory consists of three stages: Stage 1 establishes the first style or genre; Stage 2 is a perceptible and traceable transition; and Stage 3 is the establishment of the second style or genre. This creates a linear process that embraces the two established environments and the transition between them. Trajectories often incorporate widely contrasting styles, with a common recurrence of an opposition between tonal and non-tonal materials in polystylistic music, as will be noted in some of the examples below. But they can potentially involve any two styles (or hybrid environments) that bring enough contrast in their structure and associations. An abstract diagram of the strategy is represented in Example 13.

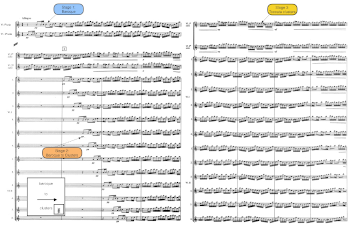

Example 14. Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.29] The second movement of Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1 (1977), entitled “Toccata,” begins with two violins, which play the same melodic line in canon at the unison and separated by a quarter note. With a casual hearing, one would not realize the piece was composed in 1977, the first few measures containing no hint of mixture (stage 1). Schnittke establishes this material as a traceable feature and, beginning at measure 6 (rehearsal mark 1), gradually transforms it through more canons at the unison, with entrances an eighth note apart (stage 2), into a different environment (stage 3). The “toccata clusters” keep the rhythmic profile of the initial material but bring in clusters resulting from the overlapping of the multiple lines in canon. Example 14 shows the beginning of this process.(21)

[2.30] One could perhaps read the transition between these two styles as an example of the distortion strategy, since one can follow Schnittke gradually altering the toccata material before finally forming it into clusters. Indeed, this distortion is nested, participating in a larger process called trajectory. The distorted environment cannot be isolated from the materials that surround it; thus, in this example, the process encompasses the initial stage of Baroque music, its gradual distortion through the reiterated canons, and its final stage as a hybrid non-tonal environment, keeping the rhythmic characteristics and imitation of the Baroque but with different pitch content. In this specific case, it is as if Schnittke sought to legitimize the non-tonal environment by rooting it in the “pure” past, while distorting it into an expanded, mixed idiom. It becomes difficult to understand the resulting environment apart from the initial one, since there is connection between all stages of the trajectory. One stage leads gradually into the other, forming a single hybrid environment.

Example 15. Possible matrix of oppositions from the beginning of Schnittke’s Toccata

(click to enlarge)

[2.31] The matrix of structural oppositions in Example 15, based on Hatten’s (1994) matrices, shows how this strategy shapes the first section of the piece, and affords interpretations that rely on the listener’s capacity to trace the gradual change, along with its contrasting characteristics and associations.(22) A focus solely on the distortion process that sets the trajectory “into motion” would overlook important characteristics of this particular hybridity. In the opening section of Schnittke’s piece, the strategy of trajectory exploits oppositions of past and present, and tonal and non-tonal, determining the initial form of the work and hinting at a specific kind of teleological engagement that might be interpreted narratologically.

[2.32] I propose trajectory as the last strategy of hybridity here because it is a compound strategy—unlike the previous categories of mixture, it requires another strategy to be incorporated during the transition. In this way, trajectories operate at a higher hierarchical level, and use gradual distortion, momentary coexistence, or brief overlap clash to achieve gradual and traceable changes. The transformation of one stylistic or generic environment into another occurs through addition, subtraction, overlap, expansion, or exaggeration of elements. Although the strategy of trajectory requires another nested strategy to exist, it is a specific and recurrent kind of interaction of disparate materials that achieves a particular effect, and thus warrants categorization as a separate strategy.(23)

[2.33] The transition or transformation process can range from strictly linear and cumulative to blocks of increasing alterations. The dimension of this strategy also varies, ranging from a short fragment to a movement-wide trajectory, as long as it is clearly perceived as a single transformation, not a plain juxtaposition. In larger examples of trajectory, the strategy itself can determine the formal aspects of a work, while “mini-trajectories” can take part in more complex hybrid environments formed by several strategies combined.

[2.34] Whereas one can find examples of coexistence and distortion (and, to a limited extent, clash) in other periods, trajectory occurs mostly in post-1960s music and is restricted to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. (24) It is the only mixture strategy of this study localized within a specific period, perhaps because of the heightened thematization of hybridity starting in the 1900s. To organize mixture strategies into the compound and linear hybrid environment of trajectory requires that the hybridity control the musical discourse, that it be at the forefront of the processes developing the piece; and there were few repertories before 1900 that could afford, both in terms of communication and syntax, such a prominence of hybridity. Trajectories always involve some combination of the mixture strategies placed along a timeline, and it is this linear status that allows this compound hybrid process to define the form of a piece—or parts of a piece—more easily than other strategies.

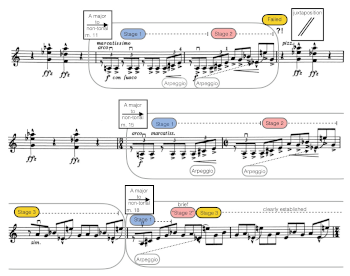

Example 16. Rochberg, Caprice no. 33, Moderato-con amore, mm. 11–23

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.35] A trajectory of considerably smaller proportions is found in Rochberg’s Caprice no. 33 from Caprice Variations for Unaccompanied Violin (1970; Example 16). In this example, the tonal/non-tonal opposition is still the main guide for the small-scale process, with the arpeggiation of an A-major triad quickly changing into a non-tonal melodic fragment: at m. 11, a repeated a3 creates momentum for an upward arpeggiation of the A-major triad, a gesture that carries the expectation of tonal continuity (Stage 1); however, it dissolves the briefly established tonal sense by adding notes outside the triad (Stage 2). This new environment is suddenly interrupted by a juxtaposition of pizzicato chords, and because trajectory is a goal-directed strategy, this first attempt is a failed one, lacking Stage 3. At m. 15, the trajectory from A major to non-tonal restarts, this time achieving Stage 3, and establishing the non-tonal environment for one measure. As a way of compensating for the failed initial trajectory, a third iteration appears at m. 18, now compressing Stages 1 and 2, while widely expanding Stage 3 with three measures of clear non-tonal material. The transition of all these trajectories involves a nested distortion, expanding and adding new elements to the triadic arpeggiation. The annotations in the score of Example 16 show this hybrid environment formed by three trajectories (the first of them failed), and their specific stages. The smaller scale of the excerpt raises the question as to whether an actual gradual process takes place, but the group should be clear as a unique block of ideas with directionality: an A-major triad moving, via brief distortion, toward the non-tonal melodic fragment. The style fields framing this process are both a kind of synecdoche: the A-major triad representing tonality, and the non-tonal line standing for post-tonal styles. Despite the lack of specificity of these style fields, their contrast works well in establishing the trajectory.

Example 17. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 3, III, r.m. 11+4

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.36] A similar use of triadic arpeggiation to represent tonality in the context of a trajectory appears in Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 3, III, r.m. 11+3–r.m. 12 (Example 17). In this case, the composer establishes a long initial environment of non-tonal counterpoint that gradually gives way to the D major arpeggio, enabled by an overlap clash, with notes from the triad appearing in one instrument at a time. At Stage 3, the texture is entirely composed of notes from the D-major triad, except for the solo violins, which keep their non-tonal material, sustaining dissonances, and clash against the newly established major chord.

[2.37] Example 17 also illustrates a hybrid environment formed not by one but multiple strategies, which interact through vertical combination. Vertical combination occurs when distinct layers or levels of the composition have different mixture strategies; here, the trajectory in lower layers clashes with the violin on top. Other possibilities are nesting and horizontal combination of hybrid processes. Nesting happens when one strategy is contained by a larger one. Horizontal combination occurs when a sequence of short strategies appears, not necessarily connecting, but still within the same hybrid environment. These compound hybrid environments, with simultaneous mixture strategies are usual in the polystylistic repertory and exponentially increase the perspectives for interpretation.

2.4.1 Interpreting Trajectory

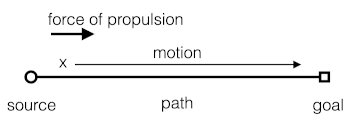

Example 18. Elements in the embodied schema of SOURCE-PATH-GOAL, as shown in Brower (2000)

(click to enlarge)

[2.38] Trajectory establishes a literal musical path or connection between disparate styles or genres, which can provide goal-directed organization to post-1960s works. This reliance on linking oppositions can be interpretively highlighted with matrices, such as the one used for Schnittke’s Toccata above, demonstrating the dynamics between the oppositions between styles and genres (or wider style and genre fields). Candace Brower’s (2000) suggested embodied schema of SOURCE-PATH-GOAL also relates to the trajectory strategy and can help inform potential teleological interpretations.(25) For Brower, this schema “organizes our experience of motion, specifically goal-directed motion” (2000, 331). If the trajectory strategy in music can be compared to the SOURCE-PATH-GOAL schema, it needs a force (or agent) that can propel that motion, as well as a definition of the goal of the process. Brower describes a general tension-release organization for the goal-directed schema: “the approach to a goal tends to be accompanied by an increase in tension and arrival at a goal by a relaxation and the slowing and/or stopping of motion” (2000, 331). This can indicate a gap to be filled, or an obstacle to be surpassed before reaching a stable level—something not clear in every case of trajectory. However, these ideas can help inform an interpretation. The status of agent of the trajectory can be assigned to the music, objectifying (or anthropomorphizing) the category of a style or genre that sets itself into motion, becoming the focus of the hybridity process and musical work. Alternatively (and perhaps the default option), one can consider the composer (or the performer, or even a combination of the two) as an agent, one who triggers the sonic/conceptual processes of the trajectory. Yet another perspective can place the listener at the center of the experience: they move along with the trajectory from one style and genre category to another. These perspectives on goal-directed agency focus on change, and the varying tension that it may establish can be combined, and will influence, the signification of a trajectory strategy. Example 18 shows Brower’s diagram for this schema.

[2.39] Situating the listener, performer, or composer within the embodied schema also relates to what the “goal” of the trajectory may be, as well as to the quality of the tension and release in the process—definitions that can afford different perspectives. By taking these variables into consideration, the interpretive leap from the SOURCE-PATH-GOAL schema to a narratological perspective of trajectories becomes feasible. In fact, narrative has been recurrently explored as an option, for instance, in studies of Schnittke’s music, which tends to rely on these kinds of processes more than that of any other polystylistic composer (see, for instance, Tremblay 2007; and Dixon 2007). The strategy of trajectory, with its marked oppositions and linear characteristics, has more teleological and narrative potential than any of the others discussed in this study. Narratological interpretations of trajectories are more convincing when dealing with larger examples of the strategy, but there is also a possibility of reading “mini-trajectories,” or a combination of trajectory environments, as being goal-directed.

[2.40] The objective of the transition from one material to another might be assigned different meanings, and this will be affected, among other things, by the kind and level of opposition they evoke. Nevertheless, the two main perspectives of a trajectory’s goal are related to change: (1) substitution, when one is taking over the other (as in Example 16 above by Rochberg, in which a haphazard non-tonal melody lacks any characteristic of the initial A-major arpeggio), or (2) unification, when they are being combined into a pluralist environment (as in Schnittke’s Example 14, in its clusters with traces of Baroque).(26) These interpretations vary case by case, and depend on several contextual and structural aspects, such as the characteristics of the materials, the length of the trajectory, and the processes used in Stage 2 to move from one to the other. Additionally, one has to deal with the interpretation of any other hybridity in Stages 1 and 3, in cases where styles are unstable.

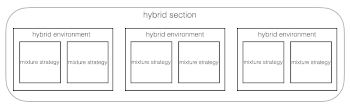

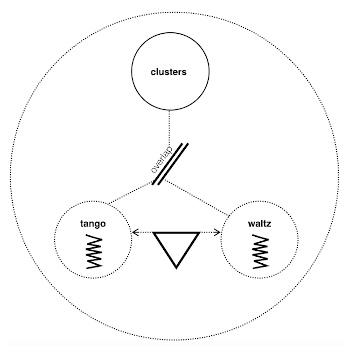

2.5 Mixture Strategies as Formal Devices and Hybridity Plan Graphs

Example 19. Formal hierarchy: mixture strategies→hybrid environments→hybrid sections

(click to enlarge)

[2.41] Mixture strategies can also raise expectations and goals of the musical discourse. In a similar way that Caplin’s (1998) and Hepokoski and Darcy’s (2006) theories focus on deeper details of Classical forms by assigning functions, harmonic goals, and signposts to elements of that repertory, the mixture strategies carry the potential to interpret how certain hybrid works develop in time. A hybrid environment occurs as a segmentation of a piece, articulating form. They can each constitute a section or belong to a clear formal articulation of a piece defined by aspects unrelated to hybridity. These environments can also be grouped into hybrid sections, a related group of hybrid moments in sequence, which might also articulate the form at a higher hierarchic level. In this way, a grouping hierarchy involves hybridity patterns: mixture strategies form hybrid environments, which can be grouped into hybrid sections as shown in Example 19.

Example 20. Visual representation stable and hybrid environments

(click to enlarge)

[2.42] In cases where hybridity influences form, the composer strings together hybrid environments or hybrid sections, creating a formal design particular to the work and connected to its mixtures. The perceived hybridity is then organized by the types of interaction of the material within each hybrid environment or section, as well as by their disposition and characteristics. The specific pattern of hybridity of a piece can be shown in a hybridity plan graph, serving both as a summary of the composition’s structure and a potential listening guide. A hybridity plan graph abstracts the main processes and materials of the work, showing the interpreter’s segmentation of the piece into hybrid environments (which can possibly form hybrid sections), and further defines these with common strategies of mixture, with their particular characteristics and set of variables. There is plenty of flexibility in how to notate hybridity plan graphs, but a general guideline is to use the symbols of each strategy within dotted line circles, which represent hybrid styles and genres, reserving solid line circles for stable moments (Example 20). These graphs work well in cases where hybridity influences the formal aspects of a piece; on the other hand, they inform little in works with sparse mixtures, which do not affect formal articulations.

Example 21. Hybridity plan graph of Pärt’s Sarabande from Collage über B-A-C-H

(click to enlarge)

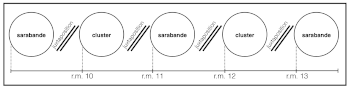

[2.43] Example 21 shows the simple hybridity plan graph of Arvo Pärt’s Sarabande from Collage über B-A-C-H. The piece, discussed in the section on the clash strategy, moves directly from one stable environment to the next. These environments, labeled “sarabande” and “cluster,” are shown as circles with solid lines. The parallel diagonal lines indicate the clash strategy, with the clarifying term “juxtaposition” indicating that these contrasting environments occur successively.

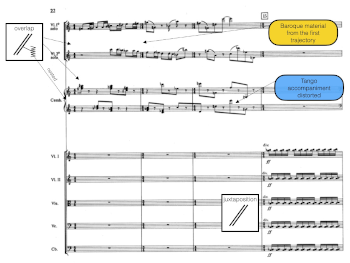

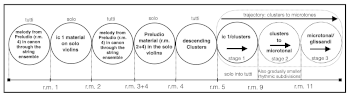

Example 22. Hybridity plan graph of Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II

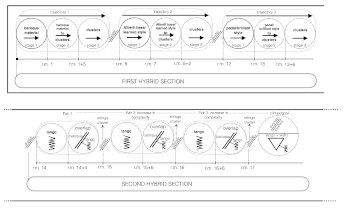

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.44] A considerably more complex hybridity plan graph represents such processes in Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II, which will be analyzed in detail in the following section (Example 22). In the analysis I tackle the musical intricacies of the work using the concepts and tools discussed so far. Next, I show how the framework also affords articulating extra-musical perspectives in dialogue with structural ones.

3. Analysis of Alfred Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, II

[3.1] Although the second movement of Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1 (1977), “Toccata,” exemplifies the strategy of trajectory, it, in fact, showcases all four mixture strategies. A recurrent descending minor-second motive and overall emphasis on ic1 establish a unifying sonority of the piece, with its predominance of clusters, minor seconds, major sevenths, and minor ninths. These sonorities help to make the mixtures throughout the piece more cohesive, despite their, at times, abrupt appearances and disparate stylistic references. The movement begins with three large trajectories with gradual distortion, which depart from stable tonal idioms into clusters or non-tonal counterpoint. After these linear, and less sudden, transformations, the hybrid environments are interpreted as containing coexistence, distortion, and clash with additional allusions to tango and waltz, creating a complex network of stylistic and generic associations. A bird’s-eye view of these processes is shown in the hybridity plan graph of Example 22, which summarizes the strategies and mixtures that develop the composition.(27)

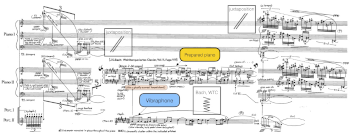

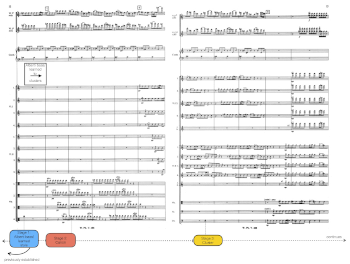

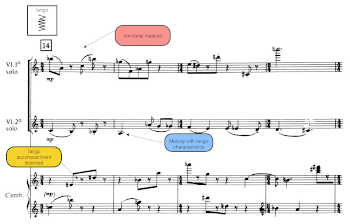

Example 23. Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II, r.m. 6–8, second trajectory

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 24. Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II, r.m. 12–13, third trajectory

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.2] The first trajectory (discussed earlier) begins with tonal material that references Baroque music. Schnittke gradually transforms this material through canons into a cluster environment that preserves the same rhythmic characteristics, i.e., “toccata clusters” (see Example 14 above). An abrupt change functions as a clash divider at r.m. 6, articulating a new version of the trajectory “tonal to non-tonal,” this time starting with an Alberti bass accompaniment and imitation in the two violins—referencing Classical style as well as, more specifically, a learned style topic. This gradual transition in Trajectory 2 establishes another clear non-tonal environment, which also incorporates ideas from the beginning of the movement, maintaining the cluster until the end of the trajectory at r.m. 11 (Example 23). Trajectory 3 begins at r.m. 12, articulated by another clash divider, when the sudden appearance of a “brilliant style” pedal is gradually taken over by clusters.(28) I interpret this trajectory as developed with a nested distortion, in which the pedal notes in the strings progressively imitate a chromatic line in the violins. All strings adhere to the chromatic motive at the trajectory’s final stage except the violins, which play motivically contrasting material that still aligns with the non-tonal style field of the established environment (Example 24).

[3.3] This group of three trajectory environments forms a hybrid section, not necessarily because of their motivic relationships, but in their related hybridity strategies. This hybrid section contains the only trajectories in the entire movement, which are placed together at the beginning of the piece as if to show the gap between the styles, genres, and style fields in use. Further, this section connects these references to Baroque and Classical music with Schnittke’s style, demonstrating how one can smoothly become the other through canons. The strategy of trajectory fittingly fulfills that role, setting the stage for the more complex non-linear hybrid environments that follow. Again, trajectories allow for more linear relationships interpreted, for example, as teleological narratives. In this case, the transformation of one stylistic reference into another can be heard as aiming at the “unified style,” which Schnittke mentions in his discussion of this piece.(29) The perspective of unification is also supported by the avoidance of abrupt interruptions, other than those separating the three trajectories, making the interpretation of parody or mockery more difficult.

Example 25. Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II, r.m. 14, distorted tango

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 26. Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II, r.m. 14+4, clash overlapping with distorted tango

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.4] Hybrid Section 2 involves faster changes of environments and the simultaneous use of several strategies through nesting, vertical, and horizontal combinations. This section begins with an abrupt change in material after Trajectory 3, which ends at r.m. 14, and this juxtaposition clash works as a divider, introducing a distortion environment entirely unrelated to the trajectories. Here, a tango accompaniment and melody (in harpsichord and Violin 2, respectively) are distorted by non-tonal pitch material (Example 25). The first violin plays tango-influenced rhythms with dissonant leaps evoking the minor seconds used by Schnittke as a motive throughout the piece. The melody in Violin 2 is based on a descending chromatic scale with octave displacement, but its rhythms and contour—a stepwise descent, followed by a large upward leap and another stepwise descent—are closer to the tango style. Additionally, the constant downbeat rhythmic profile in Violin 1 and harpsichord, along with the contour of the Violin 2 melody, reinforces the tango allusion. At r.m. 14+4, the harpsichord maintains the distorted tango accompaniment, but now with an overlap of the toccata material from the beginning of the movement, thus forming a clash environment with nested distortion: the clash between the Baroque material in the violins and the distorted tango accompaniment (see beginning of Example 26).

[3.5] This pair of related hybrid environments forms a unit that will appear twice more in this section. At r.m. 15 (Example 26), a sudden cluster interrupts the texture for a single measure. It works as a divider, after which the pair of environments—distorted tango (r.m. 15+1) and clash between tango and Baroque (r.m. 15+6)—repeat. The same alternation between distorted tango, overlap clash, and abrupt cluster interpolations appears once more at r.m. 16. This repetition creates a connection between these three pairs of hybrid environments within Hybrid Section 2, each presenting a simple distortion in alternation with the more complex process because of the added overlap clash.

Example 27. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, II, r.m. 17, coexistence, distortion and clash

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 28. Diagram of the climactic hybrid environment of Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso no. 1, II, r.m. 17

(click to enlarge)

[3.6] At r.m. 17, the last of these one-measure cluster interpolations (exactly like the one depicted at r.m. 15 in Ex. 26), functions as another clash divider, articulating a different but related environment formed by clash, coexistence, and distortion (Example 27). Violins 1 and 2 play a repeated-note pattern that creates a cluster sonority, which overlaps with the tango-like melody in the cellos, this time accompanied not by harpsichord, but by violas and double basses. The addition of double bass only on the downbeat changes the overall accent pattern to that of a waltz. This creates an intricate network of potential stylistic references seen more clearly in Example 28 and forming a coexistence of tango and waltz, both distorted, while overlapping with the cluster sonority of the solo violins. If we consider the previous hybrid environments at r.m. 14, 15 and 16—the three similar pairs articulated by cluster interruptions—r.m. 17 functions as an achieved goal. There is a small increase in complexity, as each new pair occurs. The three iterations of this process have linear/goal-directed characteristics, which find fulfillment and climax with the hybrid environment at r.m. 17. There is a sense of propulsion in this section, even though less prominent than in the first trajectories. After this environment, no more references to tango or waltz appear, reinforcing the segmentation of all this as one hybrid section.

Example 29. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, II, r.m. 18, overlap clash

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.7] Hybrid section 3 differs in its lack of linear processes. It begins at r.m. 18, with momentary stylistic stability for four measures of a strictly non-tonal environment. Here, the concertino (harpsichord and solo violins) play material based on the seconds motive, with a predominance of minor ninths in the violins, creating a fairly stable cluster environment. At r.m. 18+5, however, the harpsichord’s return creates a mixed environment, where the music suddenly changes to a “C-minor” lullaby, thus forming an overlap clash with the non-tonal material in the violins.(30) Here an abrupt change occurs only in the harpsichord material, rendering the segmentation of these two chunks ambiguous and subject to interpretation. I consider the remainder of r.m. 18 (from r.m. 18+5 onward) as a single hybrid environment (Example 29). A clash divider at r.m. 19 articulates a new stable environment formed again by descending seconds in the strings, interrupted by the interpolation of seven measures of non-tonal counterpoint in the solo violins at r.m. 20. The descending seconds resume in all strings at r.m. 21, but with material from the interpolation persisting in the solo violins, creating an overlap clash.(31) Finally, at r.m. 22, the full texture is interrupted by a stuttering motive in the solo violins and harpsichord, which then overlaps with triadic material a minor second apart in the other instruments at the last measure, thereby clearly articulating the end of the movement.

[3.8] This admittedly somewhat clinical analysis is important for demonstrating how the hybridity processes explained in the previous section may give rise to crucial interpretive insights that otherwise go unnoticed. Specifically, the characteristics of the mixture strategies and hybridity complexity of the hybrid environments foster a grouping of the Toccata into three large hybrid sections, each treating the disparate materials in a progressively harsher manner. Thus, there is a teleological sense to the movement’s often-contradictory surface both at the hybrid environment level (from one hybrid environment to the other), as well as at the hybrid section level, each with added friction.

[3.9] This framework is not limited to the structural analysis but can go beyond it offering perspectives of hybridity in context. Schnittke claimed that his intentions in using the “polystylistic method” are grounded in the search for a unified style (Schnittke 2002, 45)—a personal quest for settling the conflicts of his own plural musical background by combining, what he calls, “serious music” and “music for entertainment.” From this perspective, then, the Toccata becomes a field for the articulation of contrasting, and at times taboo, identities. His choice of references, according to this analysis, triggers different identities: baroque, classical, waltz, tango, along with non-tonal elements and clusters. Here, stylistic and generic aspects such as tonal/non-tonal, concert/popular, and past/present, become the building blocks with which to pursue a “unified style.” But the specific ways these elements are combined can also inform (and be informed by) the work’s connection with sociocultural and political layers of hybridity and difference.

[3.10] Cues for engaging interpretively with these layers come not only from the composer’s motivations and conditions—expressed thoughts and intentions on polystylism and the piece itself—but also directly from the musical articulation of the aforementioned markers of identities. As shown above, there is an emphasis on linear processes: first clearly in Hybrid Section 1 through the use of trajectories, then less evidently in Hybrid Section 2, with the increasing hybrid complexity of the pairs of hybrid environments. Finally, Hybrid Section 3 lacks any linear process, with harsher mixtures of disparate material. In this way, I interpret the Toccata movement as engaging with three potential axes of hybridity signification, organized here from subjective to collective: (1) past and present; (2) parody and pastiche; and (3) aesthetic, political, and power difference.

[3.11] The first axis deals with the notions of past and present. To that end, the ideas of Svetlana Boym (2001) on nostalgia are instrumental. Boym defines two types of nostalgia: restorative or reflective. The former focuses on the past, or an imaginary homeland, similar to the one articulated by “diasporic” accounts of hybridity; restorative nostalgia attempts to reconstruct a lost world or time. Reflective nostalgia, on the other hand, can be both about past and future, akin to “creolization” interpretations of hybridity, engaging with the past while embracing modernity and exploring the outcomes of its many contradictions (Boym 2001, xviii). The nostalgia in composing a concerto grosso is not necessarily related to a return to tradition, but rather to exploit it for developing new expressions: a fusion of past and present aimed at the utopian future of his unified style—and here the aim is quite clear if we follow the linear and gradual processes discussed in the previous paragraphs. For Boym, nostalgia “is a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy” (2), one that seems to be constantly at play in this movement and polystylistic output in general.

[3.12] Furthermore, Schnittke’s individual path as a composer during the Soviet “Thaw” (in the 1950s and early 60s) contributes to a more complex relationship with the constraints of tradition, pointing to the second proposed axis of signification—that of parody and pastiche (closely related with the trope of hybridity as a subversive space [Bhabha 1994). Commonly, musical hybrids are addressed as expressions of irony or parody. But a more nuanced view of mixtures allows also for a different interpretation, more akin to pastiche, in which there is no mocking or irony by default in the use of disparate styles or genres. The hybridity in the Toccata exemplifies such a nuanced approach. The composer claimed to “take them [the styles] all seriously” (Schnittke 2002, 45), but how, if at all, is this expressed in the way the materials are combined?(32) Does the Toccata sound like a parody? Are its processes reinforcing an expression of irony? I suggest neither is the case. The harsher mixtures in the piece are carefully prepared by creating linear and gradual hybrid environments in the first two sections. This care in treating stylistic oppositions distances the work from parody, and the sense of subversiveness it articulates does not rely on mockery. The subversion here is, in fact, that of attempting to treat musical hybridity seriously, as something more than a senseless combination of disparate material and, again in Schnittke’s words, “the right to give an individual reflection of the musical situation that is free of sectarian prejudice” (Schnittke 2002, 45).

[3.13] At this point in the discussion it becomes difficult to consider the mixtures in the Toccata as “pure aesthetic difference,” a question appropriately raised by Born and Hesmondhalgh (2000) in considering music and alterity. Hybridity in the Toccata engages with—whether the composer intended it or not—politics of difference and the geopolitical directionality involved in hybridity, our third and last axis of signification. For the most part, there are allusions to stylistic features and concepts that belong strictly to the Western concert music tradition (concerto grosso, toccata, learned style, Alberti bass, non-tonal counterpoint, and clusters), the only potential exoticism being the allusion to tango. However, as the composer writes, it was the tango his grandmother used to play for him, which provides a completely different take on the appropriation of a non-Western style: this is rather an autobiographical marker. Also, having lived during Krushchev’s Thaw, Schnittke’s status as a Western or non-Western composer is not completely clear. This ambivalence blurs the geopolitical lines of power, and mitigates an interpretation of the appropriation of popular references as a way to “reinvigorate the dominant culture”—in this case, the concert music tradition. Nevertheless, the Toccata is not a non-threatening hybridity, going much further than a simple mindless patchwork of appropriated styles. It is an engaged exploration of plural musical identity at the personal level (a search for expression), questioning the place for hybrids in the concert music tradition. Hybridity engenders, in this way, an empowering condition, one of taming tradition to fit the composer’s own project.

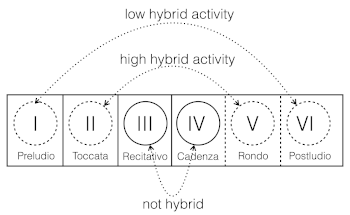

3.1 Situating the Toccata within the Six Movements

[3.14] Whereas a detailed analysis of all Concerto Grosso’s six movements would go beyond the space and scope of this text, it is important to situate the second movement within the entire piece and contextualize its large-scale hybridity. Hybridity processes work at a local level as shown in the many previous examples, but they can also help interpret the movement-level organization. Schnittke’s Toccata is connected to the other movements not only because of the type of materials, motives, and processes they share, but also because of the level of hybridity in each.(33)

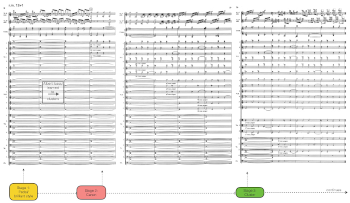

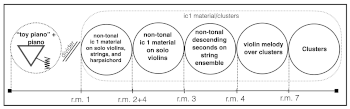

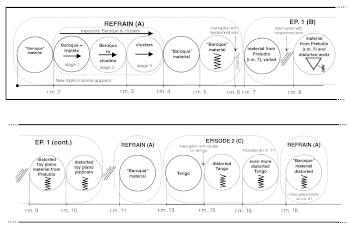

Example 30. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, I, hybridity plan graph

(click to enlarge)

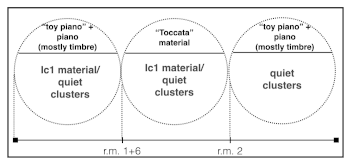

[3.15] The first movement, Preludio, presents distortion and coexistence in its first measures (Example 30). A prepared piano, having coins in the upper register strings, gets a little out of tune and reminds of a toy piano—a distortion of a traditional piano. There is also a constant low note, which is not affected by this distortion but coexists with the material in the higher register. The repetitive character of the low notes grounds the lullaby-like material of the distorted toy piano, which can be interpreted as a reminiscence.(34) This hybrid beginning in the first movement alerts to mixture processes as part of the compositional strategy right away. This is confirmed by the abrupt juxtaposition, at r.m. 1, of two violins, a harpsichord, and a string ensemble developing completely unrelated material based on a minor second sonority. The minor second sonority (ic1) introduced at r.m. 1 is a crucial motive of the piece because it serves as the entry point into the clusters environment that demarcates one side of the style polarization in the Concerto Grosso no. 1. The introductory toy piano is the other side, emphasizing tonality and past styles. Next, the Preludio presents several ic1 ideas that will be further explored in later movements of the piece. In terms of hybridity, after the first eleven measures of “prepared piano” material, the movement stays within the same “ic1” and “cluster” sonorities. This considerably simple clash juxtaposition has a larger rhetorical function—it indicates that the ic1 sounds that dominate the first movement (and recur throughout) are not there on their own, but in relation to the initial tonal reminiscence brought by the prepared piano. The toy piano provides a brief initial backdrop of tonality, past, and memory against which hybrid processes take place, and will only return in the fifth movement of the piece. There are some abrupt juxtapositions of materials and alternation of soloist group (the two violins) and tutti, reminiscent of the concerto genre. These are not considered clashes since the style markers are mostly the same despite the textural contrast.

[3.16] It is within the context established by the Preludio that the second movement, Toccata, starts to gradually develop the connection between these two general style polarities—tonal/past/reminiscence and cluster/ic1/present—in subtler ways. To briefly summarize the previous analysis, tonal styles are presented and transformed into clusters via trajectories. The second half of the movement is less subtle, creating ever more abrupt overlap and juxtaposition clashes, culminating in a coexistence of distorted waltz and tango overlapping with cluster material. The movement ends in cluster materials. The prepared piano does not return, but the tonal styles serve as markers for that side of the stylistic spectrum.

Example 31. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, III, hybridity plan graph

(click to enlarge)

[3.17] Whereas the second movement explores general changes from tonal ideas (thirds) into clusters (seconds). The third movement, Recitativo, departs from the clusters and takes it further toward gradually narrower intervals with the use of microtonal sonorities. Most of the movement is developed through alternation between soloist group and tutti and canons of the melody from r.m. 4 in the first movement. Similar to the process in the Toccata, these canons happen at minor second intervals, generating clusters. There is no reference to any tonal style in the entire movement, only the ic1 materials, with some quotations of ideas presented in the Preludio. At around r.m. 6, the microtones start appearing in the violins, slowly taking over the entire string ensemble, in a trajectory similar in process to the many presented in the second movement. Now, the minor seconds are transformed into ever smaller sonorities, changing into glissandi, and abruptly collapsing into a single note. A musical pitch blackhole of sorts. Example 31 provides the hybridity plan graph for the movement.

Example 32. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, IV, hybridity plan graph

(click to enlarge)

[3.18] The Cadenza, with only the two solo violins, brings the ic1 material from the first movement, but with microtonal inflections, as if affected by the previous movement’s trajectory into narrower intervals (Example 32). At r.m. 2, both instruments suddenly start playing pizzicato, which triggers a new trajectory into narrower realms. The third movement took care of narrowing the pitch interval in detail. The cadenza focuses on narrowing the rhythmic aspects, creating a gradual transition from metrically measured (and slower) to unmeasured (and faster) material. There are two trajectories separated abruptly by trills and fortissimo chords. The second of these trajectories start from faster rhythms, as if continuing the work done by the first, and getting further subdivided until it collapses. This time, however, the collapse is a temporal one. This is a trajectory into a “rhythmic clusters” blackhole. As the two violins cannot get any more chaotic, the trajectory stops abruptly, with the clash juxtaposition of an unforeseen cadential progression that starts in C major and soon changes to minor. This cadence prepares the highly hybrid fifth movement, Rondo.

Example 33. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, V, hybridity plan graph

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.19] The Rondo brings an amount of hybrid activity comparable in this work only to the Toccata. It revisits the processes of transformation from tonal styles into clusters, but it lacks the almost pedagogical series of trajectories from the second movement. Sticking generally to the formal plan of a 5-part rondo (ABACA), it relies on alternating many different materials with the “baroque” refrain (A). The first episode (B) of the rondo uses four different materials abruptly juxtaposed. The second episode (C) is dedicated to distorting the tango ideas presented in the first two movements, Preludio and Toccata. As the last refrain of the rondo appears, we are left with the now familiar baroque theme agonizing amidst intense distortion. Then a coda starts with ic1 ideas, followed by an overlap of the distorted Baroque material and a distorted tango material (r.m. 24)—a climactic moment comparable to the Toccata’s r.m. 17, mixing tango, waltz, and clusters (c.f. Example 27). This distorted overlap clash is interrupted by new tonal material in

Example 34. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, VI, hybridity plan graph

(click to enlarge)

[3.20] The Postludio has little activity, hybrid or otherwise (Example 34). It serves as a confirmation of the outcomes from the hybrid processes presented throughout the previous five movements. The clear result is that the clusters and the ic1 ideas remain strong whereas the tonal materials fade, even though they are still faintly heard. The toy piano shows up with small gestures, briefly cutting through the mass of clusters in the strings, connecting to the first ideas of the concerto. After two appearances, the toccata material, which had not shown up since the end of the second movement, appears softly for three measures in the middle of the decisive and final cluster environment that ends the piece.

Example 35. Schnittke, Concerto Grosso no. 1, symmetry of hybrid activity in all six movements

(click to enlarge)

[3.21] One can have a general idea of how hybridity also organizes the concerto at a large scale, with hybrid activity being reserved for the framing movements (I, II, V, VI) in a symmetrical way, as shown in Example 35.

4. Final Thoughts

[4.1] This article presented a framework to interpret mixtures of styles and genres structurally and applied these ideas to a selected repertory of 1960s polystylism. The aim of developing four basic mixture strategies—clash, coexistence, distortion, and trajectory—is, first, to afford general analytical and interpretive tools for a compositional layer that has lacked a detailed perspective. Second, the same basic strategies might be applied to a diverse range of musical works, and allow for a contextualized, diachronic comparison through the central perceptual and structural effects of hybridity. Furthermore, these strategies need not focus on one specific compositional aspect (pitch, rhythm, texture, for instance), nor do they reduce an analysis of this repertory to a listing of sources alluded to or quoted; they focus on flexible engagements with expressions of hybridity. Once we consider contextual aspects, conditions, and motivations of specific cases of hybridity, the present analytical framework provides a way to connect compositional strategies, values, ideologies, and perceptually evident patterns, thus emphasizing the communicative possibilities of this music. The framework also contributes to a dynamic analytical process, involving context, familiarity, and recognition as important variables of the musical experience. These variables highlight the potential for multiple meanings in the network of stylistic associations and the processes that affect them in hybrid compositions.

[4.2] I have engaged with the analytical layer of style and genre as a parameter—a variable means for musical expression and interpretation. This parameter affords opportunities to address the dynamic status of boundaries in a productive and contextually engaged manner. Once a reconceptualization of the notions of style and genre occurs, moving beyond an essentialist perspective, these more flexible categories may serve to guide and organize, while not rigidly defining or restricting musical engagements.

[4.3] Nederveen Pieterse writes that “the importance of hybridity is that it problematizes boundaries” (2009, 5). Furthermore, in music, a focus on matters of identity through hybridity can connect structural choices with their social, political, and economic contexts. This focus may elucidate as much about an individual musical work and its technical characteristics as the systems of categories that guide a specific creative community. Hybridity, understood as a common and ubiquitous cultural process, also helps to counter pejorative perspectives on mixture (which can have, for instance, connotations of impurity or inauthenticity). Instead, hybridity may highlight the fluid and contingent status of identities—a subject increasingly vital in the twenty-first century, as we face far-reaching discussions about identity politics. In this way, music is—as it always has been—a space for a projection of these matters; styles, genres, and their manipulations in hybridity become important tools in this equation.

Bruno Alcalde

University of South Carolina

813 Assembly St.

Columbia, SC 29208

balcalde@sc.edu

Works Cited

Baler, Pablo. 2016. Latin American Neo-Baroque: Senses of Distortion. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59183-8.

Bellman, Jonathan. 1998. The Exotic in Western Music. Northeastern University Press.