Integration, Urbanity, and Multi-Dimensionality in Schoenberg’s First Quartet*

Sam Reenan

KEYWORDS: sonata form, program music, Arnold Schoenberg, two-dimensional sonata form, Nervenkunst, genre systems, forms-as-genres, narrative levels, mise en abyme

ABSTRACT: This article addresses the network of forms and genres at play in Schoenberg’s First String Quartet, op. 7, proposing a conception of the work as a representation of urban life in fin-de-siècle Vienna. I offer a summary of the emotionally volatile program and prior analyses, highlighting the central points of contention between analysts. Most especially, these include the relationship between an overall sonata form and a set of intervening cyclic movements. I then problematize Steven Vande Moortele’s notion of “two-dimensional sonata form,” drawing from theoretical investigations into narrative levels and embedded forms in literary theory. The bulk of the article revolves around a thoroughgoing analysis of the large-scale form of the Quartet, presenting a novel reading that situates the work within a complex web of interacting forms and genres. The Quartet begins as a large-scale sonata form, which is interrupted by a juxtaposed cycle of interpolated movements. Upon the arrival of the rondo finale, the sonata is complete. I demonstrate that the rondo finale may be construed as a mirror to a large-scale overarching rondo that can explain the multiple dimensions of the entire work.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.28.1.8

Copyright © 2022 Society for Music Theory

Civitas verbi: artistic wholes and literary systems are, like great cities, complex environments and areas of integration. (Guillén 1971, 13)

1. Cities, Circles, and Networks: Metaphors of Form and Historical Progression

[1.1] In his notes to a lecture on his First String Quartet, op. 7, Arnold Schoenberg ([1935] 2016, 157) directly associates the historical progress that preceded his early compositions with the contemporaneous evolution of cities like his own home of Vienna. Schoenberg planned to begin the lecture with a discussion of “development,” principally the expansion of large cities and their populations, a byproduct of which was “large concert halls” and “high fees.” He might have included the Musikverein among such halls, which had been built near the Ringstrasse just a few years before the composer was born and had a capacity for over two thousand audience members, making it the largest concert hall in the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time of its construction.(1) Schoenberg identifies a consequence of this physical urban development: an “aim for monumentalism.” He compares this to monumentalism in music, including J. S. Bach’s Matthäus-Passion, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, as well as more recent works by Anton Bruckner, Franz Liszt, Gustav Mahler, and Richard Strauss, many of which were cast in a single movement.(2) While describing the First Chamber Symphony, op. 9 (1906), and later works in 1949, Schoenberg ([1949a] 2016) would demonstrate an about-face along the artistic lines of Adolf Loos’s aesthetic anti-ornamentalism:

Students of my works will recognize how in my career the tendency to condense has gradually changed my entire style of composition; how, by renouncing repetitions, sequences, and elaboration, I finally arrived at a style of concision and brevity, in which every technical or structural necessity was carried out without unnecessary extension, in which every single unit is supposed to be functional.(3) (166)

Yet fifteen years earlier, Schoenberg was still connecting the First Quartet to the expanding city and the extensive, so-called “maximalist” works of his peers, to borrow Richard Taruskin’s (2005, 5) term. What might have motivated the composer to associate his Quartet with the interconnected notions of development, urbanity, and musical monumentalism?

[1.2] In this article, I argue that Schoenberg sought to reconstitute in music the characteristic urban activity of Vienna, which had become an artistic and intellectual hub by the early twentieth century. Holly Watkins (2011) analyzes the fin-de-siècle urbanization of Vienna alongside the psychological effects, as articulated by Georg Simmel, that it had on its citizenry. For Simmel ([1903] 2013), the cityscape featured an “intensification of nervous stimulation that results from the swift and uninterrupted change of outer and inner stimuli” (25; emphasis in the original), forcing inhabitants to exist at a “heightened level of consciousness in order to keep up with constant sensory bombardment and an accelerated pace of movement” (Watkins 2011, 197). Quoting the critic Ernst Décsey, Watkins argues that the effect on Schoenberg was provocative: “Far from retreating to a protected inner sphere, Schoenberg composed in a ‘virtual frenzy of confession’” (200). Schoenberg’s early atonal works reflect Viennese urban development in part by their shifting tempi and rhetorical capriciousness—as Watkins puts it, they “might be better understood as psychographs of the overstimulated urban subject, a ‘metropolitan type’ who experiences an unrelenting flux of ‘outer and inner impressions’” (206).(4) The fixation on direct expression of interior subjectivity was, for Schoenberg, supported historically by the work of those whom he admired, including Bruckner, Mahler, and Strauss: “Much of [the] extension in my own works was the result of a desire, common to all my predecessors and contemporaries, to express every character and mood in a broad manner” ([1949a] 2016, 165). This trait of early modern Viennese living resulted in the Nervenkunst artistic movement, an inscription in art of the heightened consciousness of daily life.(5) For Schoenberg, the emotionally volatile private program for the Quartet, which he drafted in 1904, offers evidence from the period of the work’s composition for his interest in the experience of fin-de-siècle urbanity.

[1.3] By conceptualizing his own compositional efforts in the Quartet along the lines of a goal-directed historical development, Schoenberg suggests a framework of history that seems compatible with more recent work by Carl Dahlhaus and Steven Vande Moortele. The latter proposes a graphic depiction of the lineage of Romantic form as a series of concentric circles, reminiscent of Dahlhaus’s ([1980] 1989) “circumpolar” history of the symphonic genre:

This multidimensional model [of musical form] might be conceptualised as a set of concentric circles, at the centre of which stand the Classical norms and conventions casting, as a kind of prima prattica, a long shadow across the nineteenth century. The outer circles stand for a multifarious seconda prattica, with every circle representing the normative practice of a different period (including a composer’s personal practice). With each new generation of composers, the canon grows, and a new layer is added to the stack of available formal options. For any specific piece, a composer may choose to activate—or, perhaps more accurately, the analyst may choose to emphasize—certain sets of conventions while ignoring others.(6) (Vande Moortele 2013, 411)

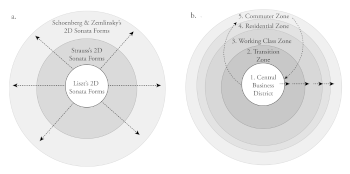

Example 1. Concentric circles as metaphorical models

(click to enlarge)

Vande Moortele suggests that concentric circles model a historical extension and expansion of the genres of Classical music, transcending the boundaries of the eighteenth century into and through the Romantic era. This model presupposes the resilience of a formal practice, a resilience which is also on display in his 2009 monograph on “two-dimensional sonata form.” There, Vande Moortele touts the “remarkable continuity that spans more than half a century and connects the works of Liszt and Strauss to those of Schoenberg and Zemlinsky” (2009, 6). Following Vande Moortele’s model, Example 1a summarizes this continuity, conceptualizing Schoenberg’s op. 7 and Zemlinsky’s op. 15 String Quartets as direct descendants of Liszt’s B-minor Sonata, S. 178 (1854).

[1.4] As a cognitive metaphor, the concentric circle model is commonly applied, and it can suggest a variety of conceptual entailments. Abstract notions of inclusion and recursion are implied in the image of concentric circles, a representation that has itself been employed in the study of urbanity. Ernest W. Burgess ([1925] 1967) writes that the expansion of American cities “can best be illustrated, perhaps, by a series of concentric circles, which may be numbered to designate both the successive zones of urban extension and the types of areas differentiated in the process of expansion” (50). As indicated in Example 1b, Burgess notes two tendencies: first, that of “each inner zone to extend its area by the invasion of the next outer zone”; and second, that of the competing forces of concentration at the downtown and decentralization to the suburbs (52). The concentric zone model of urban development thus carries notions of extension and expansion but also of delimitation, centralization, and dissociation.(7) Although devised in relation to Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia, Burgess’s scheme can also model the impact of the Ringstrasse in Vienna during the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Spurred by a surging city population (Schorske 1980, 25), the sixty-meter-wide boulevard was completed in 1870 and effectively defined an internal old city while increasing transit between the center and the suburbs. It also stood as an icon of the capitalism, secularism, and liberalism that dominated the Empire at the time (26–27, 45).(8) Watkins sees in some of Schoenberg’s atonal music a manifestation of the social dissociation enacted by the Ringstrasse: “In its reliance on images of disorientation and irresolute motion, Schoenberg’s depiction of spiritual waywardness in Die Jakobsleiter pointed to contemporary concerns over the alienated and soulless movement generated by modern urban planning” (2011, 226).

[1.5] Despite its applications in musical form as well as urban development, the concentric circle model is too inflexible to serve as a conceptual interpretation of Schoenberg’s First Quartet. Schoenberg manipulated conflicting structural and rhetorical procedures in op. 7, coordinating the hybridization of multiple genres to express the unpredictable inner world of the urban subject. We are therefore in need of a correspondingly fluid interpretive frame. In his theory of literary genre systems, Claudio Guillén (1971) offers such an alternative approach, as evidenced by the epigraph to this article. Guillén’s model—once more calling upon the concept of the city—relies on “complex environments” and “integration,” rather than the notions of hierarchy and recursion that are central to a concentric circle model. Its foundation is the metaphor of genres as institutions.(9) Literary systems (represented as cities in this analogy) involve complex interactions between literary genres (as institutions). The historical development of genres, like institutions, reflects identity through change, whereby the institution replicates and reifies its norms and principles while simultaneously adapting to its environment. We can liken institutions to individual musical genres. The historical development of genre systems, featuring a limited number of institutionally resilient genres, involves assimilation and the absorption of change and innovation over time. Like a city, the system undergoes constant compromise between the (institutional) norms and principles of multiple genres. Integration of genres is neither expansive nor recursive, because genres exist at the same level within the system. This flattened model, resisting hierarchy as a necessary component (at least at the system level), foregrounds interactions themselves, allowing for the freedom to orchestrate references to multiple generic prototypes. In adapting Guillén’s theory, I propose that musical forms be understood as genres, combining within systems made of the intersections of multiple, competing formal processes.

[1.6] Following Guillén, we might retain the concentric circle model for the historical development of a single form-as-genre. But at the turn of the twentieth century, Schoenberg found expressive potential in the combined forces of several forms-as-genres; the individual work is thus better interpreted as a singular event within a system of comingled genres. Multiple network-like interactions are possible within a system of genres. They create what Guillén terms “structures,” “the interrelations (of significant dependence) between constituent units,” where the units are genres (1971, 12). Because I conceive of form as constitutive of genre, an individual instantiation of form has the capacity to integrate several genres that coexist within a system, creating new structures.

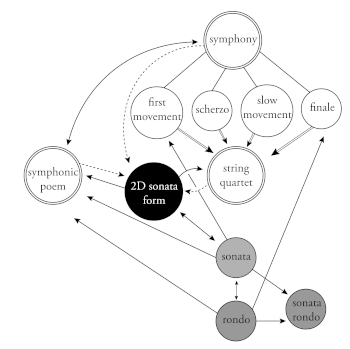

Example 2. A generic network for Schoenberg’s First String Quartet, op. 7

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[1.7] The system of interacting genres in Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet involves, at a minimum, those charted in Example 2. It includes single-movement forms (in gray), multi-movement forms (in black), single-movement genres (in white, with a single circular outline), and multi-movement genres (in white, with two circular outlines). A legend is provided, which encodes various interactions between genres and forms-as-genres. Note that formal procedures (like sonata form) should be understood as genre defining but as distinct from generic categories in which they might appear (like a first movement). The forms-as-genres of two-dimensional sonata form, sonata, rondo, and sonata rondo, while capable of manifesting as coextensive with a particular genre, function in this network as formal procedures distinct from those genres. As an example, the arrow connecting the sonata form to the first-movement genre represents the notion that Schoenberg’s Quartet, by invoking the sonata cycle, draws on the standard procedure for a first-movement genre to appear in sonata form. Vande Moortele’s two-dimensional sonata form is a contributing form-as-genre within this network, and the role of two-dimensional sonata form is in part intertextual. Schoenberg himself leaves some evidence to suggest a correspondence between the formal organization of op. 7 and the single-movement cyclic forms of Liszt and Strauss; yet shortly after summoning these earlier composers’ work, he remarks that his Quartet will represent “a new attempt to organize such a form” (Schoenberg [1935] 2016, 158). As the analytical sections of this article will show, the formal procedures of sonata, rondo, and two-dimensional sonata form combine in their interaction with first movement, finale, symphonic poem, and string quartet genres to produce the work’s large-scale form.

[1.8] By imagining the String Quartet as “the future of symphonic thought,” in Hans Keller’s (1974b) words, the network in Example 2 highlights the influences of symphonic forms and genres on the early Modernist string quartet genre.(10) The network reflects a characteristic that Alban Berg identifies with Schoenberg’s compositional practice more generally: “the drawing together of all existing compositional resources from the music of past centuries” ([1924] 2013, 193). As Dika Newlin writes, Schoenberg had already accomplished in Verklärte Nacht, op. 4 (1899), the composition of “a piece of chamber music in the style of a symphonic poem” ([1947] 1978, 211), thus making the symphonic poem genre appropriate in the present generic analysis. Combined with the private program, which will be discussed momentarily, we can view the programmatic, symphonic poem elements of the work along the lines of the expression of urban interiority.

[1.9] Each genre in Example 2 should be understood to constitute its own historically continuous development (which may be represented by individual series of concentric circles).(11) The significance of the network model lies in the interactions between these genres. The various manifestations of the single-movement/multi-movement generic structure are of particular interest, as they demonstrate that a work like op. 7 has the potential to engage in several multi-dimensional relationships. Two-dimensional sonata form—which features the interaction between a sonata “cycle” (including a “local sonata form”) and an “overarching sonata form”—constitutes one such manifestation of a generic structure based on the fusion of a single-movement form and a multi-movement structure. But many other intersections can be considered, and they imitate the processes of interaction, commingling, absorption, and hybridity that are encountered by institutions within a city ecosystem. An institution persists as an entity within the city environment, but the city itself endures through the interactions of those institutions. A singular event within the city ecosystem depends on the interconnectedness of many institutions; Schoenberg’s Quartet, likewise, exists by virtue of its coarticulation of multiple distinct formal procedures. Working within the genre system that comprises forms and types of musical compositions at the turn of the twentieth century, the network accounts for many of the stated or implied large-scale genres at play in op. 7. Across the levels of large-scale form, individual movements, and particular themes, the Quartet’s nervous urban psychology manifests in multiple forms: as a network of interacting forms, as a progression of emotional states, and as a musical surface featuring intense, conflicted thematicism.

[1.10] Schoenberg’s First Quartet thus summons the formal and generic rhetoric of several competing large-scale single-movement forms, and this article addresses the network of forms at play from the perspective of generic multiplicity. First, I summarize the private program—placing the work in dialogue with the symphonic poem—while also addressing prior analyses to highlight the central points of contention between analysts. Then, I draw on the notion of narrative juxtaposition from literary theory to account for the interaction between sonata form and sonata cycle in op. 7. In this discussion, I problematize the linkage between musical form and hierarchy in two-dimensional sonata forms. I subsequently offer an analysis of the large-scale form of the Quartet as an instance of retrospective “mise en abyme,” proposing a novel rondo-form reading inspired by the writings of Keller. The system/city metaphor is central to the interpretive conclusions from that analysis, as it models the Nervenkunst mentality of the program as well as the generic mixture that underpins Schoenberg’s monumentalism. As Keller quips: “all good works are in more than one form; a single form is always boring” ([1974a] 1999, 15).

2. Schoenberg’s Musical Nervenkunst and Prior Approaches to the op. 7 Quartet

[2.1] Among the first to analyze op. 7 was the composer himself. Schoenberg drafted several documents concerning the Quartet, including an analysis published in Die Musik ahead of the 1907 Dresden premiere, private notes for a 1935 lecture to the general public at the University of Southern California, and 1949 program notes for the Juilliard String Quartet’s performance of all four of his Quartets. In the latter, Schoenberg describes the “achievements” of the op. 7 Quartet, first among them “the construction of extremely large forms” ([1949b] 2016, 358). Themes were manipulated in such a way as to “produce one integrated, continuous composition” ([1935] 2016, 154). Although in 1949 Schoenberg sought to dispel the notion that the work might be considered program music, in her memoir of the composer, Newlin notes a class discussion from 1940 in which Schoenberg claimed that “the extravagances of the form were because the piece was really a sort of ‘symphonic poem’” with a “very definite—but private!” program (1980, 193).(12) Christian Schmidt (1986) uncovered the only known iteration of the op. 7 program, and Mark Benson (1993) gives the first comprehensive account of the program’s potential structural import.

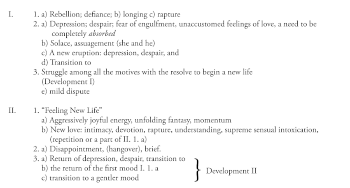

Example 3. The “very definite—but very private” program for Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.2] The program, drafted in 1904, is reproduced from a translation by J. Daniel Jenkins (Schoenberg [1904] 2016, 151–53) in Example 3. Benson argues convincingly that it was written after Schoenberg had already completed several months of composition. Overall, the narrative projects a Romantic premise: “anxiety over a love relationship” (Benson 1993, 378). Featuring a chaotic series of mental states, the program is emblematic of the Nervenkunst tradition, the artistic manifestation of Simmel’s notion that the mental state of the fin de siècle was stimulated by heightened sensuousness. Keller makes a similar point, noting that Schoenberg’s compositional agenda in op. 7 was to integrate “the widest possible range of expression” ([1974a] 1999, 11). Schoenberg’s series of disjointed emotional states are represented, as we will see, by corresponding music that shifts abruptly between various musical textures and styles. The program is grouped into three large segments, marked with Roman numerals, and Schoenberg indicates two development sections—one parenthetical, the other seemingly more substantial. Although the work is devised as a single movement, “not in fact four movements separated by pauses” (Schoenberg [1907] 2016, 154), a large division should be understood before the section marked III, as the score includes a Grand Pause at the corresponding moment.(13)

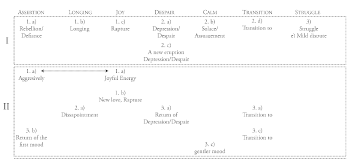

Example 4. A paradigmatic analysis of the program to Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.3] Beyond the overt references to musical form—the two developments, as well as terms like “transition,” “return,” and “repetition”—structural cues in the program come in the form of explicit restatements of programmatic terms and more abstract sequences that may be interpreted as beginning-middle-end patterns. Example 4 offers a paradigmatic analysis of the program,(14) grouping various terms into seven expressive categories: Assertion, Longing, Joy, Despair, Calm, Transition, and Struggle. These seven categories appear in order in Section I of the program. In Sections II and III, all of the moods reappear, except for Struggle. Section II launches with the description “Aggressively joyful energy,” which combines the Assertion and Joy expressive categories. It is also labeled in the program in Example 3 with the words “Feeling New Life,” an optimistic outlook that is reinforced in the subsequent “New love” unit. Section III lacks the Assertion category, presenting a trajectory from negatively valenced emotions (Longing and Despair) toward positive emotions (Joy and Calm). Sections I and II of the program are organized around the two development sections, leading finally to a reprise of the first mood and a gentler close, whereas Section III seems to imply a second, independent part, presenting a clear teleology toward the joyful and contemplative ending. The programmatic information provides some cues for how we might interpret structural musical events. Alongside the two developments, we might expect a recapitulation of the “defiant” theme from the very opening near the close of Section II because of the phrase “the return of the first mood I. 1. a” in the program. Furthermore, we might anticipate some thematic integration between the various Longing and Despair thematic states, as they represent contrasting moods to the Assertion and Joy that begin and end the program.

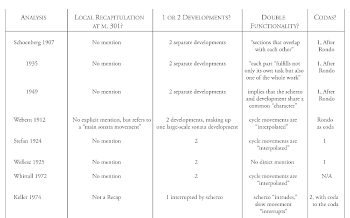

Example 5. A table highlighting the main differences among the most significant analyses of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.4] In the analyses that follow in §4–5, I fold these elements of the private program directly into the music-analytical observations to demonstrate Schoenberg’s musical depiction of the mental overstimulation that characterized his social and compositional environment. Despite the existence of the program, most scholars have focused on the score when studying op. 7.(15) Besides the three analyses by the composer himself ([1907] 2016, [1935] 2016, [1949b] 2016), important published discussions of the Quartet have been written by Anton Webern (1912; cited in translation in Rauchhaupt 1971), Paul Stefan (1924), Egon Wellesz ([1925] 1985), Arnold Whittall (1972), Jim Samson (1977), Severine Neff (1984), Dahlhaus (1988), Walter Frisch (1988, 1993), and Michael Cherlin (2007), beyond the previously discussed writings by Benson (1993) and Vande Moortele (2009). Rather than rehearse each of these analyses in detail, I focus here on the main differences that arise among these analysts’ readings of the work’s large-scale form, which are summarized in Example 5. As noted in the table, four formal questions garner particular attention. First, the analysts all grapple with the interpretation of a recapitulation in the “local” sonata form. Second, the puzzling relationship between the scherzo movement and the development of the sonata form causes divergent interpretations of either one or two development sections.(16) Third, as Schoenberg ([1935] 2016, 158) himself writes that the parts of the Quartet are “in such a manner linked together that [every one] fulfills not only its own task but also one of the whole work,” the independence of the internal movements is of central dispute.(17) Finally, the question of coda space leads to controversy—analysts disagree over whether there is a single coda, or two, or a coda-to-the-coda.

[2.5] Among all the discourse surrounding Schoenberg’s First Quartet, one veritable outlier remains. Keller propounds a tantalizing alternative reading, an until-then unrealized “basic structural feature” of op. 7: “a macrocosmic sonata rondo reflecting, mirroring, the microcosmic rondo that is the finale section of the continuous movement” (1974b, 10). This is, in effect, a “two-dimensional sonata-rondo,” the role of local mirror played by the rondo finale. Keller continues: “It is a feature of outstanding importance for the future of symphonism”—a future that comprises the very subject of his article—“this promotion of the sonata rondo, a structural upgrading of what used to be a last-movement, lighter-movement form. The inventor or promoter was not Schoenberg, but Mahler, who thus reacted, functionally, to the beginning disintegration of tonality and its unifying power: the power of the theme itself had to be reinforced” (1974b, 10). A more thoroughgoing account appears in the transcription of a radio lecture Keller gave for the BBC on September 1st, 1974.(18) Keller’s description of the form involves not two but three dimensions, namely, the sonata, the rondo, and the four-movement cycle:(19)

On the one hand we are confronted with a four-movement structure which is compressed into a single movement. On the other hand we are confronted with a large-scale sonata movement which at various stages is interrupted, and meaningfully interrupted, in order to make way for the contrasting elements of a four-movement work. On the third hand, however, we are confronted—and this is what the coda tells us, or rather confirms—with a rondo structure, or rather with two rondo structures.. . . There is, in short, the little sonata form and the large sonata form, that is to say the first movement and the entire movement (because, as I have reminded you, the first movement is interrupted at a stage where all the important sonata events have happened); and there is the little rondo form—that’s the last movement—and the large rondo form—which is again the entire work—on top of or at the bottom of which all is the four-movement scheme. ([1974a] 1999, 14–15)

In the analytical sections to follow, I reimagine Keller’s proposed form. The work is generically complex: a symphonic poem and string quartet; a multi-dimensional sonata, or rondo, or both; and a single movement that still incorporates distinct internal “movements.” Over the course of the work, interpolations weaken the sonata form. The rondo finale, on the other hand, is quite intact. My analysis below presents a formal process involving the gradual transfer of organizing power from a discontinuous and proleptic sonata form to an embedded, analeptic, and epiphanic rondo finale, which reveals the overarching rondo that spans the entire work.(20) The integrated overarching rondo form is mirrored by the local rondo finale that concludes the cycle.

3. Refining Multi-Dimensionality Through Narrative Levels and Formal Juxtaposition

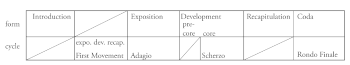

Example 6. A reproduction of the form chart for Vande Moortele’s (2009) two-dimensional sonata form analysis of Liszt’s B-Minor Sonata

(click to enlarge)

[3.1] In order to reconceive form and genre in Schoenberg’s First Quartet, we first need to re-examine Vande Moortele’s model of two-dimensional sonata form, focusing on the assumption that “musical form is hierarchically organized” (2009, 11). Two-dimensional sonata form involves “the combination of the movements of a sonata cycle and the sections of a sonata form at the same hierarchical level of a single-movement composition” (23).(21) The prototype is Liszt’s B-minor Sonata. As shown in the diagram reproduced in Example 6, Vande Moortele proposes a process of “identification”: “The first movement of the sonata cycle (the local sonata form) coincides with the introduction and the exposition of the overarching sonata form. The recapitulation and the coda of the overarching sonata form coincide with the scherzo and the finale in the dimension of the cycle” (24). These are “double-functional” components of the two-dimensional sonata form, to borrow William Newman’s ([1969] 1983, 131) term; they have roles in both Vande Moortele’s “dimension of the form” and his “dimension of the cycle.” In Liszt’s Sonata, the development of the overarching sonata form and the slow movement of the sonata cycle evidently only function in their own dimensions, as indicated by the slashes in the corresponding parts of the diagram; Vande Moortele terms the former an “exocyclic unit,” the latter an “interpolated movement” (2009, 25–26). In nearly every case, Vande Moortele’s two-dimensional sonata forms require the identification of a local sonata form in the overarching sonata form (usually as an exposition and development, where the local recapitulation may be interpreted as a false recapitulation in the overarching development).(22) Moreover, the complete sequence of the local sonata is always understood to proceed uninterrupted.

[3.2] The interaction between the dimension of the cycle and the dimension of the form appears to be hierarchically complex. There is a “high frequency of complex interactions between different levels of formal hierarchy” in two-dimensional sonata form: “elements of a single-movement sonata form and elements of a multi-movement sonata cycle, which normally operate at different hierarchical levels, reside at one and the same hierarchical level” (14). Yet since each dimension presupposes its own hierarchy—a “complete” cyclic hierarchy (comprising levels of the cycle, form, section, segment, and part) and an “incomplete” overarching sonata-form hierarchy—Vande Moortele asserts that there is an oblique relationship between the two dimensions: “A cycle in the complete hierarchy is a form in the incomplete hierarchy, while a form in the complete hierarchy is a section in the incomplete one,” and so on (21). This process of identification assumes a hierarchical relationship between three components: the overarching sonata form, which provides the large-scale organization for the sonata cycle, which includes the local sonata as a form within the cycle but a section within the overarching sonata form.

[3.3] Vande Moortele’s classification of works by Liszt, Strauss, Schoenberg, and Zemlinsky as examples of two-dimensional sonata forms therefore implicitly interprets the works through the lens of organicist recursion. Consider, for example, Vande Moortele’s discussion of analogies between different hierarchical levels (2009, 17–20). Drawing on A. B. Marx and Hugo Riemann, he suggests that abstract homologies exist between, at the macro level, the three-section sonata (exposition–development–recapitulation) and the three-or-four-movement sonata cycle (first movement–interior movement[s]–finale). Vande Moortele then zooms in, articulating a cognate relationship that he terms “self-evident” between the (now) four-section sonata (exposition–development–recapitulation–coda) and the four-part sonata exposition (main theme group–transition–subordinate theme group–closing group). This discussion, in which Vande Moortele does offer some counterarguments to Marx and Riemann, ultimately centers around a set of recursive affordances that, I argue, reinforces the assumption that a two-dimensional form will include a local sonata form mirroring the overarching sonata.(23) Michael Cherlin (2007) extends the recursive model to an extreme dimension in his formal analysis of Schoenberg’s First Quartet. Since all four movements are divisible into three-part forms, the units of which themselves comprise three parts, Cherlin contends that “in each case the resultant is a miniature version of the larger three-part form” (2007, 168).(23) While these recursive interpretations do exist, the two quartets that conclude Two-Dimensional Sonata Form—Schoenberg’s op. 7 and Alexander von Zemlinsky’s op. 15—are better interpreted along the lines of a network of generic interactions, because in each work the double functional potential of the local sonata does not in fact materialize.

[3.4] In relation to the specific case of Schoenberg’s First Quartet, Vande Moortele’s model of two-dimensional sonata form suffers from three principal shortcomings. First, the model depends too heavily on the Lisztian prototype, ascribing to it what Monahan, speaking more generally, terms a “direct, disproportionate, and undiminished influence” (2011, 40n30). It therefore privileges Liszt’s approach in the B-minor Sonata over other precursors (especially Franz Schubert’s “Wanderer” Fantasy, D. 760, and Robert Schumann’s Fourth Symphony, op. 120).(25) Second, the model is too rigid, insisting that the single-movement form that mirrors the overarching form must be a sonata. Third, the model is simultaneously too general, associating within the same formal category works that are completely “double functional” with those that (almost) entirely lack multi-dimensional identification—namely, Schoenberg’s op. 7 and Zemlinsky’s op. 15.

[3.5] I propose an alternative framework for envisioning the relationship at the macroformal level between single-movement form and multi-movement cycle. This framework draws on literary scholarship regarding the theory of narrative levels and embedded narrative. I consider recursive hierarchy as one option among several. The single-movement/multi-movement generic structure might imply a single-movement form that is hierarchically subordinate to a multi-movement cycle or overarching form, as in two-dimensional sonata form. But, there are some alternatives: the single-movement form and multi-movement cycle might combine to create a large-scale formal hybrid; any single-movement form might be embedded within a large-scale form but not necessarily in a recursive relationship to the overall form; parts of the cycle and/or parts of the single-movement form might be engaged in double functionality across multiple dimensions while others are not; or multiple forms-as-genres might play out simultaneously, sequentially, or in parallel. More than fifty years after Liszt’s Sonata, two-dimensional sonata form had become one possible hierarchically dependent way of organizing the interaction between multiple dimensions. At the level of large-scale form, this hierarchical dependence is not, however, entailed by such interactions.

[3.6] In his account of “narrative levels,” Gérard Genette delineates a relationship between “narration” and the “narrated”: “any event a narrative recounts is at a diegetic level immediately higher than the level at which the narrating act producing this narrative is placed” ([1972] 1980, 228; emphasis in the original).(26) Interactions between levels can be grouped, according to Genette, by their function: relationships may be “explanatory,” whereby a “direct causality” exists between, e.g., the main narrative and an embedded narrative; “thematic,” whereby a contrast or analogy exists between components of different levels; or “narrational,” whereby an act of narrating itself functions in the main narrative, usually by obstruction or distraction (232–33). Lucien Dällenbach argues that a basic property of embedded narrative is “an analogy between an utterance and an aspect of the narrative” ([1977] 1989, 46). However, the analogy need not be literal—Dällenbach allows for such abstract relationships as “resemblance, comparison, parallel, relation, and coincidence.”

[3.7] Responding primarily to the work of Dällenbach and Genette, Mieke Bal refines the theory of embedded narrative in a manner that becomes applicable to the present account of Schoenberg’s Quartet. For embedding to occur, Bal proposes that three characteristics are necessary:

- (i) Insertion: the embedded narrative must be distinguished by some perceptible transition from the primary narrative into the embedded one;

- (ii) Subordination: a hierarchical distinction must exist between narrative levels;

- (iii) Homogeneity: “the embedded units must be members of the same class” as the primary narrative. (1981, 43–44)

Bal makes an important acknowledgement, though, regarding “subordination”: narratives at different levels can be related by “juxtaposition,” in which no subordinate relationship exists between parallel phenomena of the same class. While an embedded narrative requires that a “narrative object” become “the subject of the following level” (45), no such double function is required of juxtaposed narratives. Judith Ofcarcik has offered a preliminary approach to such parallel musical event sequences in the context of musical narrative. In her account, moments of disjunction are particularly important, as they prime the listener to imagine a narrative shuttling from one strand to another. As she writes, “the hermeneutic point of this structure is the multiplicity itself, the idea that the meaning cannot be contained in a single plot” (2020, [1.4]). Ofcarcik’s work in musical narrative is motivated by a pluralist mindset not unlike the one I bring to bear in accounting for the generic interactions in Schoenberg’s First Quartet. Here, I view the relationship between the local sonata form and the remaining movements of the sonata cycle as a case of juxtaposition, where the local sonata is interrupted by the remaining cyclic movements.

[3.8] Elsewhere, Bal distills the relationship between an embedded narrative and the primary narrative (or “fabula”) along the lines of the placement of the embedded narrative (which she describes as a “mirror-text”) within the overarching narrative:

When the mirror-text occurs near the beginning, the reader may, on the basis of the mirror-text, predict the end of the primary fabula.. . . When a mirror-text has been added more towards the end of the primary text, suspense presents itself less emphatically. The course of the fabula is then largely familiar, and the function of the mirror-text is no longer predictive, but retrospective. A simple repetition of the primary fabula in a mirror-text would not be as interesting. Its function is mostly to enhance or inflect significance. ([1985] 2017, 57)

In essence, the predictive and retrospective functions of the mirror-text are refinements of Genette’s “explanatory” function, serving to guide the reader to an understanding of the overall narrative in either a proleptic or analeptic manner. The potential for the embedded text to function in a predictive manner may apply to Vande Moortele’s conception of two-dimensional sonata form. The local sonata, appearing at the outset of the work, offers a structural clue as to the unfolding of the overarching form, itself a sonata form. In Schoenberg’s Quartet, however, we will see that the role of embedded form is played not by a local sonata at the outset of the piece, but rather as a local rondo, appearing at the end of the work and performing a retrospective critique of and revelation about the work as a whole.

[3.9] In Vande Moortele’s theory, the preference for a hierarchical model of form precludes the possibility of two juxtaposed forms (the single-movement sonata and the multi-movement cycle) working in parallel at the level of large-scale generic interactions. This is because Vande Moortele defines his theory around a corpus of works espousing a similar structural principle: “every two-dimensional sonata form discussed in this book begins as if it were a one-dimensional sonata form” (2009, 27). In other words, all of the works cast in two-dimensional sonata form include some degree of identification between the exposition of the sonata form and the opening of the sonata cycle. To account for a situation in which the sonata form does not participate in identification with part of the sonata cycle, Vande Moortele would have to consider the local sonata form an “exocyclic unit,” even while it is the movement that launches the cycle.

Example 7. A hypothetical form chart of a two-dimensional large rondo, in which the first-movement sonata is double-functional as the initial refrain-episode-refrain paradigm

(click to enlarge)

Example 8. A hypothetical form chart of a two-dimensional sonata form that features an interpolated first-movement sonata

(click to enlarge)

[3.10] My approach to the network of generic interactions at the level of large-scale form draws from Bal, Genette, and Dällenbach, and the competing notions of narrative levels and generic juxtaposition. With the freedom to imagine alternative generic structures, we might imagine two-dimensional large-scale forms wherein the overarching form is ternary, rondo, or another large-scale form, or where that form is itself interrupted by interpolation. Alongside the array of possibilities for overarching forms, recursion and double functionality are likewise generic options, rather than explicit requirements, in devising structures that fuse single-movement and multi-movement forms. Example 7 demonstrates a hypothetical two-dimensional rondo form, in which the rondo finale serves a double function as the final refrain of an overarching seven-part rondo. The local rondo serves as Bal’s mirror-text, arriving at the close to provide something of a summary and recontextualization of past events. The first-movement sonata could—but need not—serve a double function at the level of the form. For instance, Example 8 shows a two-dimensional form in which the local sonata form, the first movement, is “interpolated” after a slow introduction and before the dimension of the overarching form officially launches. This construct is possible because of the leniency with which Vande Moortele defines interpolation. A comparable situation arises in Mahler’s Eighth Symphony. A complete first movement—indicated as such and separated from the remainder of the work—occurs in Part 1 of the Symphony. Subsequently, Part 2 comprises candidates for the remaining three movements of the sonata cycle and has also been analyzed (de la Grange 1999) as an overarching sonata form.

Example 9. A form chart of a single-movement/multi-movement structure that involves shuttling between the dimension of the sonata form and the dimension of the cycle, with no double-functional components

(click to enlarge)

[3.11] Multi-dimensional forms that combine the components of a sonata cycle and a sonata form accordingly need not depend upon a mirroring relationship between the local sonata form and the overarching form. Besides, the empirical support for a sustained practice of mirroring between a local and overarching sonata form remains suspect because of the stark differences between, e.g., the Lisztian two-dimensional sonata forms and those that Vande Moortele identifies by Schoenberg and Zemlinsky. If we abandon the assumption that the local sonata must function both as the first part of the overarching sonata, then we can instead view the exposition of the overarching sonata as just that: the exposition of an as-yet unfinished sonata. Then, it becomes possible to imagine a large-scale form that employs not two hierarchical dimensions but two parallel dimensions in juxtaposition: a large-scale single-movement form and a multi-movement cycle. Example 9 offers a model for such a form. The hypothetical movement is, at its most abstract, a large-scale sonata form with the slow movement, scherzo, and rondo finale all interpolated between sonata formal functions, never entering into multi-dimensional identification. I contend that Schoenberg’s First Quartet and Zemlinsky’s Second Quartet are both better understood along these lines.(27)

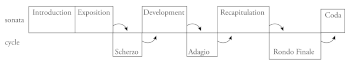

Example 10. An account of the large-scale form of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.12] The form charts in Example 10 outline my overall interpretation of Schoenberg’s First Quartet. Example 10a is a view of the form at the broadest scale, while Examples 10b and 10c zoom in on the “outer” movements of the symphonic cycle. Note that Example 10b presents the sonata-form “movement” as if it were continuous; this is of course not the case. The moments when the scherzo and slow movement interrupt the sonata-form movement are indicated by the wavy lines in the form chart. The influence of Schoenberg’s own analyses (ca. [1907] 2016, [1935] 2016, [1949b] 2016) will be felt throughout the discussion below. I will focus on the sonata and the rondo, as the thematic characters of the scherzo and the slow movement can be deduced by their relationship to those two outer movements. As the piece progresses, the initial stages present the exposition and development of a sonata form with no signals of multi-dimensionality. The exposition previews the thematic material for nearly the entire quartet and establishes, primarily via texture, the emotional states of the private program’s first section. Once the scherzo arrives and interrupts the sonata, a second layer (that of the sonata cycle) becomes juxtaposed with that of the sonata. The disconnected recapitulation that follows reflects the program’s call for “the return of the first mood I. 1. a.”(28) Not until the arrival of the local rondo is the overarching five-part rondo revealed, as a process of epiphany and summary plays out in the local form.

4. The Discontinuous, Proleptic Sonata Form of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet

[4.1] The exposition of the sonata form serves to launch the Quartet as a whole and provides the thematic content for every major section until the Grand Pause. It can thus be considered a proleptic microcosm of the Quartet, functioning to a certain degree like the foreshadowing mirror-texts that Bal associates with the beginning of a narrative. Yet, several factors preclude an interpretation of the movement as an embedded sonata form, thus problematizing its relationship to two-dimensional sonata form. Following Bal, the sonata’s discontinuous presentation disqualifies its interpretation as an embedded form, because an embedded narrative “must form an isolable whole, constituting an interruption, or at least a temporal shift, in the story” (1978, 124).(29) Likewise, we will see that no sufficient recapitulation occurs prior to the scherzo. The local exposition and development are better understood as the beginning of a sonata-form movement that plays out in juxtaposition with the interpolated movements of the cycle.

Example 11. Excerpts from the sonata exposition of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 1. The initial presentation of the primary-theme complex, mm. 1–29

Audio Example 2. The transition theme, mm. 97–103

[4.2] In my analysis of the exposition, I follow Schoenberg’s ([1907] 2016, 154) thematic labeling, in which the primary-theme complex comprises three parts: Pa, Pb, and Pc. The beginnings of these components are reproduced in Examples 11a–c. Each of the three primary-theme components involves a theme and a countertheme (labeled, e.g., Pa.1 and Pa.2), as can be heard in Audio Example 1.(30) This characteristic combination of themes and counterthemes represents for Berg ([1924] 2013, 188–89) part of the psychological complexity of the work, as Pa.1 and Pa.2 are not metrically coordinated. The Pa theme stands for the first emotional state of the music: “Rebellion; defiance.” Initially in D minor, the Pa theme reappears in

[4.3] Schoenberg ([1907] 2016) identifies a single transition theme, which I divide into two motives in Example 11d. Later on, he notes the theme’s proleptic role as an “anticipation of the Scherzo-theme” (Schoenberg [1935] 2016, 159); as Benson argues, the scherzo theme was composed first, and the transition and secondary-theme complex were conceived purposefully to simulate a process of thematic development.(32) Beginning in m. 99 (A.3(33)), the transition involves a churning fugato combination of Tr1 and Tr2, with systematic transposition of the motives.(34) Listen in Audio Example 2 for the dramatic change in texture from the primary-theme complex, which reflects the shift in mood toward Despair. If the transition theme was designed with forward compatibility to the scherzo in mind, one might expect a corresponding mental state in the latter part of the program. Yet the scherzo is marked as “Feeling New Life,” and its first mental state is described as “aggressively joyful energy.”(35) Instead of parallel mental states, Schoenberg reconstructs the aforementioned thematic continuity between the transition and the scherzo all while presenting diametrically opposed dynamics and textures, encoding in musical material the emotional volatility of the program. The piano fugato polyphony of the Despair transition contrasts with the forte coordinated homophony in the Joyful scherzo to signal these different emotions.

Example 12. Excerpts from the sonata transition of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet, which demonstrate the evolution of the chromatic neighbor figure

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 3. Excerpts from the transition: mm. 97–103, mm. 127–32, and mm. 140–51

Audio Example 4. The secondary-theme complex, mm. 152–181

[4.4] The tonal volatility at the opening of the transition, coupled with subsequent Fortspinnung of the two transition-theme motives, identifies the music as transitional in the form-functional sense. But this section also creates crucial thematic links between the primary-theme complex and the secondary-theme complex. Consider the motivic transformations indicated in Example 11. By manipulating motives and Gestalten from the main components of the primary-theme complex, the transition simultaneously abandons the thematic forms of P and prepares the lyrical themes of S. In Example 12 and Audio Example 3, compare the opening motive of Pa with the second half of Tr2, as presented in m. 100 (A.4) in the violin 1, and in the violin 2 in mm. 127–32 (A.31). The original lower neighbor first transforms into a twice-repeating neighbor motion, before becoming a long, chromatically ascending line of repeated neighbor tones. Imitating the fugato treatment of the earlier transition motives, this longer chromatic line then transfers to each of the voices of the Quartet after m. 140 (A.44), which can be heard at the end of Audio Example 3.

[4.5] The secondary-theme complex presents yet another dramatic shift in texture, as the mental state expressed by the music changes from agitated Despair to lyrical Calm (the program indicates “Solace, assuagement [she and he]”). Reinforcing the change, Schoenberg adds for the first time the marking ausdrucksvoll (“expressive”). The near homophony at m. 153 (A.57) is so far unprecedented, contrasting unmistakably with the polyphonic primary theme and fugato transition. Reproduced in Example 11, Schoenberg identifies three components of the secondary-theme complex: Sa, Sb, and Sc, the last of which is a variant that combines Sa and Sb. Extending merely thirty-five measures, the secondary-theme complex (Audio Example 4) performs its rhetorical function quickly. The textural and thematic contrast to the primary themes is paired with a tonal and modal contrast with the D-minor tonic, established not only by the

[4.6] As outlined in [2.4] above, analysts have handled the “interrupted” development that ensues after m. 213 (B.14) in primarily three ways: either (i) the developmental process genuinely pauses, to resume after the scherzo; (ii) the development continues unabated through the scherzo, supported by the thematic integration of the scherzo and the transition theme; or (iii) the sonata involves two developments, the first concluding before the scherzo, with the second beginning thereafter. The status of the sonata form’s development also figures in the private program, where Schoenberg expressly indicates two developmental sections. The first is aimed toward the emotional state of the scherzo, as the development involves a “struggle among all the motives with the resolve to begin a new life,” which evidently begins with the scherzo (labeled “Feeling New Life”). We might then describe the function of the first development in double-functional terms: it simultaneously forms the development of the sonata form and creates a programmatic transition to the scherzo.

[4.7] Schoenberg’s own description of sonata-form developments provides useful insight into an interpretation of the two development sections of the Quartet. In Fundamentals of Musical Composition, he establishes several functional events unique to development sections:(36)

Because the exposition is basically stable, the elaboration tends to be modulatory. Because the exposition uses closely related keys, the elaboration usually includes more remote regions. Because the exposition “develops” a wealth of differing themes from a basic motive, the elaboration normally makes use of variants of previously “exposed” themes, seldom evolving new musical ideas.

. . .

It consists of a number of segments, passing systematically through a number of contrasting keys or regions. It ends with the establishment of an appropriate upbeat chord or retransition, preparing for the recapitulation.

. . .

The thematic material may be drawn from the themes of the exposition in any order.

. . .

In approaching the retransition, shorter and shorter segments, often accompanied by more rapid change of region, provide both a climactic condensation and a partial liquidation. (1967, 206)

Schoenberg’s analytical comments about op. 7 are remarkably consistent on this point. The 1904 program includes two distinct developments, as do each of the analyses of 1907, 1935, and 1949. Additionally, the composer distinguishes the single-movement/multi-movement structure employed in op. 7 from that of the op. 9 Chamber Symphony: “While in the First String Quartet there are two large sections of Durchführung, that is, elaboration (or development), here [in op. 9] is only one, and it is much shorter” (Schoenberg [1949a] 2016, 164–66). The development section that precedes the scherzo executes the principal roles that Schoenberg outlines above, while also creating a tonal and rhetorical transition to the scherzo. It should thus be considered independent from the second development, where the juxtaposed design of this piece repurposes the retransition at the end of the development as a transition out of sonata space. The scherzo, then, interrupts the large-scale sonata form, but not the development itself.

Example 13. The false recapitulation during the first development of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet, mm. 301–9

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 5. The false recapitulation, mm. 299–310

[4.8] Since the scherzo begins in the key of

It is not until m. 301 that dimensions are really disconnected, since mm. 301–398 are the first formal unit to fulfill two completely different functions simultaneously. While in the dimension of the form they are yet another unit in the development section, they function as a recapitulation of the first movement in the dimension of the cycle. This conflict between non-identical functions sheds new light on the preceding portion of the composition, revealing that there were two different dimensions at work all along. Only here is the listener urged to reconsider what he or she has heard before and to interpret it not only as the exposition and the beginning of the development in one sonata form, but also as the exposition and the entire development in another, smaller-scale sonata form. (2009, 138–39)

Vande Moortele goes on to argue that the double functionality of the primary-theme statement at m. 301 is a prime example of how the “tension between [the demands of both dimensions] can be kept under control at a point at which it threatens to become most problematic” (139). His attempt to describe a recapitulation at this stage serves to establish a mirroring relationship between a complete, local sonata form in mm. 1–398 and an overarching sonata form that spans the entire work. If this interpretation were to hold, the local sonata form would satisfy the terms of Bal’s embedded text: it would be complete and isolable with clear delineation from the subsequent scherzo (Bal’s “insertion”), would be hierarchically “subordinate” to the large-scale form, and would be “homogeneous” with the overarching sonata form.

[4.9] Borrowing the notion of the juxtaposition of two different structural processes, I propose that the music in mm. 301–99 constitutes a developmental rotation of some of the exposition’s themes, without performing double function as a recapitulation. Instead, the sonata-form component of the Quartet is yet to be completed, existing in a discontinuous form because of the interpolations of the second and third movements of the cycle. To be sure, the primary theme does appear to return at m. 301. But the rhetorical cues hardly signal a moment of recapitulation. The restatement is restricted to the Pa.1 motive, and even then, only its first five measures. It appears in the lower strings in

[4.10] As a recapitulation, these various main-theme returns would be insufficient. However, as transposed statements of a large-scale passage of prior thematic material, they accomplish the rhetorical task of the development as described by Schoenberg above. Indeed, they launch a rotation of parts of the entire exposition as a third unit of the development, treating, in order, the Pa.1 motive (301–34), the transition theme (335–48; C.35), and the Sa and Sb themes (349–63; C.49) as sources for elaboration. Each component theme complex undergoes significant abbreviation and modification, processes that flout the form-functional expectations of a recapitulation. The transition theme is highly chromatic and in stretto, unraveling into “Z” motives after only seven measures. Moreover, the Sa theme is only hinted at by an initial motive, repeated five times in the first violin and viola, with an agitated accompaniment that ignores the original texture. Finally, the retransition in mm. 366–98 (D.1) concludes with a circle-of-fifths progression to reinstate the preparatory dominant of the ensuing

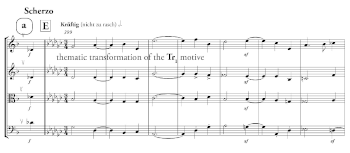

Example 14. The scherzo theme of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet, m. 399–414, which is based on the transition theme.

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 6. The scherzo theme, mm. 399–414

[4.11] After the interpolated scherzo, the second development follows a similar script to the first, although it is thematically cumulative and thus incorporates themes from both the sonata exposition and the scherzo. In particular, this development primarily features the themes of the scherzo and trio sections—which are, nevertheless, integrated with the thematic content of the sonata’s exposition. The cumulative nature of this second development initiates a transfer of power from proleptic to analeptic musical integration. In a further instance of generic mixture, this section can be construed as a development of the scherzo, proposing a possible hybridization of the genres of scherzo middle movement and sonata form. As shown in Example 14 and Audio Example 6, the scherzo recalls the sonata, repurposing its Tr1 motive as the principal thematic material of the scherzo and, in inversion, the trio. The second development then begins with a fugato treatment of that same scherzo theme, where subject entries outline a minor-third cycle. Texturally and thematically, this material returns to the Despair of the exposition’s transition section (as indicated in the program at II. 3. a). The transpositional pattern seems to launch once more in m. 846, but a rush of ascending gestures leads into the arrival of the retransition in m. 872 (I.1), corresponding to the terms “transition to” in the program. Beginning in C major, the retransition employs a large-scale circle-of-fifths progression to land on Bb minor in m. 889 (I.18), after which two sudden whole-tone ascents lead to a downbeat D major in m. 893. The music intensifies, primary-theme motives arrive in earnest, and the sforzando

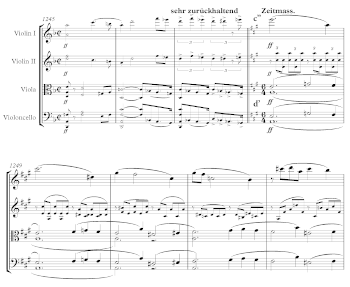

Example 15. The primary theme from the sonata recapitulation of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 7. The primary theme of the sonata recapitulation, mm. 906–31

[4.12] At m. 909 (I.38), the sonata’s veritable recapitulation begins in the tonic D minor. Following the program, the initial mental states of “rebellion” and “defiance” return (II. 3. b), reflected in a re-enactment of the texture and thematic counterpoint of the exposition’s primary theme. Pa.1 is doubled and fortissimo in the middle voices and counterpointed by two instances of Pa.2: an elaborated version with octave leaps in the violin 1 and an inverted diminution in the cello (see Example 15). The doubling of the Pa.1 idea repurposes a textural choice from the exposition—the moment of “rapture”—to reinforce the recapitulatory effect of the moment, which can be heard in Audio Example 7. The Pa theme now extends all the way through its original continuation. The primary-theme complex continues, reintroducing the Pb theme in m. 927 (I.56) before a passage of liquidation. A short transitional solo in the cello leads ultimately to a Grand Pause, the end of the first half of the composition and likewise the end of Section II of the private program.(37) The subsequent slow movement interrupts the process of the recapitulation, giving way at m. 1082 (L.52) to the secondary-theme complex. A complete restatement in rotational order of Sa, Sb (1100; L.70), and Sc (1108; L.78) occurs, and the stability of the global tonic, D, is confirmed by the return to D minor at the start of Sc.

[4.13] The sonata form is therefore complete, if discontinuous. Its exposition is proleptic because it offers the thematic and motivic material for nearly the entire Quartet, serving as a source for thematic development in the scherzo and the slow movement (save its initial theme). The sonata is not, however, an embedded form, because it encounters two interpolated movements: the scherzo and the slow movement. Instead, it charts a parallel path, juxtaposing its form with the middle movements of the sonata cycle. The music shuttles between parallel dimensions of the sonata movement and the sonata cycle without creating a double functional relationship between the two structures. If this sonata form is indeed a discontinuous but “single-functional” form, though, what of Schoenberg’s contention that the parts of the Quartet are “in such a manner linked together that [each one] fulfills not only its own task but also one of the whole work” ([1935] 2016, 158)?

5. Mise en Abyme, Embedded Narrative, and the Quartet’s Transfer of Organizing Power

[5.1] At this juncture, Keller’s intriguing interpretation of the rondo finale becomes relevant. By the time the rondo begins, the sonata form is complete, its rhetorical work accomplished by the tonic return of S. The subsequent rondo is a true embedded form, meeting Bal’s criteria of “insertion,” “subordination,” and “homogeneity.” As an “inserted” form, the rondo is prepared by a transition out of sonata space and left by a transition into coda space. The “subordination” of the local rondo relates to its completeness, capacity for isolation, and role in the analeptic summary of previous music. Finally, the local rondo mirrors a large-scale five-part rondo that encompasses the entire work, thus representing a “homogeneous” relationship between part and whole. As shown in Example 10a, the overarching rondo is in five parts, with transitions between each part.(38) The opening sonata exposition serves as the large-scale rondo refrain, while the first development functions doubly as a transition to Episode 1, the scherzo. The scherzo’s reprise shuttles back to the second development which serves a double function as a retransition at the level of the large-scale rondo. The short refrain that follows—the primary-theme recapitulation of the local sonata—is followed by a Grand Pause, after which the second developmental episode arrives. This second episode is in two parts, encompassing both the slow movement and the local rondo finale, and it incorporates the only theme (labeled c in Example 10) that seems to lack obvious antecedents in the sonata’s exposition. After a short retransition, the large-scale final refrain arrives in the major tonic at m. 1270 (O.1), serving a double function as a coda at the level of the sonata cycle. Contrasting with the large-scale rondo refrain (in the form of the primary-theme complex) are two theme groups: the scherzo themes and the slow movement and rondo themes. The two episodes are prepared in different ways—the scherzo is preceded by the first development as a large-scale transition, whereas the slow movement arrives after the articulating Grand Pause. Each episode ultimately leads back to a tonic-key restatement of the overarching main theme, in standard rondo fashion.

[5.2] In order to address the functional role of the rondo finale of Schoenberg’s First Quartet, a brief return to literary theory will prove useful. In particular, I propose that the rondo finale constitutes a musical rendering of the concept of mise en abyme, the representation of an artwork within the same or similar artwork. Traditionally, mise en abyme refers to recursive structures. André Gide coined the term, defining it through self-reflexivity: “In a work of art I rather like to find transposed, on the scale of the characters, the very subject of that work. Nothing throws a clearer light upon it or more surely establishes the proportions of the whole” ([1893] 1947, 30–31).(39) In a monograph dedicated to mise en abyme, Dällenbach ([1977] 1989, 24) distinguishes between the “simple” reflection described by Gide and the “infinite” reflection of, for example, Don Quixote, in which the character, Don Quixote, becomes a reader himself of the text in which he takes part, thus initiating an infinite series of Dons reading Dons about Dons. Genette situates mise en abyme as an “extreme form” of his thematic functional relationship, featuring an analogy between components of the overarching level and some lower level. One could conceivably view the relationship between local and overarching form in Vande Moortele’s two-dimensional sonata form along the lines of simple reflection: the local sonata reflects and projects itself onto the overarching sonata.

[5.3] The concept of mise en abyme represents a metaphor that can be applied to the situation of any artwork containing within itself a miniature of itself, where the relationship between the overall form and the miniature is construed in terms of abstract similarity. As Patricia M. Lawlor puts it, “what is reflected [in mise en abyme] is not images or even words, but language in process” (1985, 144; emphasis in the original). In Cherlin’s analysis of Schoenberg’s op. 7, for example, we might reinterpret the tripartite recursion paradigm as an instance of form-functional mise en abyme across several levels. The proposed isomorphic relationships between sonata cycle, sonata form, exposition, and primary theme embody the same reflexive property, evoking for Cherlin notions of “symmetry, hierarchy, and stability” (2007, 170). Simple mise en abyme similarly features a single, isolated structure subsumed within a larger structure that it mirrors, while one may infer further correspondences between the component parts of each structure.

[5.4] Bal generalizes the notion of mise en abyme as “any sign, having as its signified a relevant and continuous aspect of the text, narrative, or story that it signifies by means of similarity, once or multiple times” (1978, 123).(40) As the concept of juxtaposition makes apparent, while mise en abyme “must form an isolable whole, constituting an interruption, or at least a temporal shift, in the story,”(41) a more general relationship of “iconicity”(42) need not depend upon an interruption of the overall narrative by an “isolable whole.” In other words, interactions between narrative levels come in a variety of types, not merely the recursive relations between a large-scale form and its embedded miniature. When considering mise en abyme in a musical context, we can borrow Bal’s framework: a text embedded “en abyme” will necessarily feature “insertion,” “subordination,” and “homogeneity.” In Schoenberg’s First Quartet, the local sonata form does not fulfill these requirements, as demonstrated in §4 above. Instead, it is the rondo finale that represents the embedded mirror to an overarching, large-scale five-part rondo form.

[5.5] The local rondo mirrors the overarching form by comprising five parts, as charted in Example 10c. At this stage in the composition, the specifics of the private program become difficult to interpret because the program appears to combine the slow movement, rondo, and coda all under a single section III. It seems plausible that the euphoric coda represents the “Homecoming,” which might then suggest that the rondo involves the “dream image” leading to the “decision to return home” (see Example 3, emphasis in the original). Likewise, since the exposition’s secondary-theme complex represents “Solace,” it would make sense for the recapitulation of the secondary theme to constitute the corresponding “Falling into sleep” that precedes the dream. The subsequent rondo finale performs an overall function of epiphany, revealing, for the first time, the contrapuntal combination of all of the themes that have occurred. Interpreting it along the lines of a “dream image,” that recalls “the deserted ones, each grieving in his own way for the distant one” therefore seems conceivable. The epiphany of the rondo also concludes the transfer of organizing power that has taken place across the entire piece, by revealing the overarching rondo that spans the entire work, which is not made apparent until the arrival of its mirror in miniature. Whittall suggests that the rondo’s analeptic role is presaged by the developments that precede it:

The dynamism of the developments, by making themes from different expositions compatible, renders any large-scale separate recapitulation unnecessary and, indeed, impossible. The potentialities of the material are fully utilized in development, and so the rondo “finale” section introduces no new main themes but concentrates instead on further discussion of material from all three areas of exposition. (1972, 14)

Across the entire rondo, thematic ideas from earlier in the piece are recast in a new light and treated in combination, thus revealing the overall thematic integration of the entire work.

Example 16. The first refrain of the local rondo of Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet, mm. 1122–42

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 8. The first refrain of the local rondo, mm. 1122–42

[5.6] The rondo’s first refrain, spanning mm. 1122–49 (M.1), deputizes a rhythmically energized variant (at pitch) of the slow movement’s main theme c as the rondo theme, c’’, in A major (see Example 16 and Audio Example 8). The theme is a series of disjointed, three-beat descending gestures leading toward a cadence, the last portion of which borrows the sonata primary-theme’s X motive. Then, the violin 1 recalls Sa motives in a sequential passage that is mimicked by the cello in mm. 1133–36 (M.12). The viola immediately follows with the Pa.1 motive in E minor, which repeats in transposition twice. To borrow the evocative words of Adele Katz (1945, 373), the opening theme of the sonata “insinuates itself” even here in the rondo refrain, as it has in each of the preceding “movements.” The rondo theme’s presentation reappears in the violin 1 at m. 1143 (M.22), back in A major to conclude the refrain. A short, three-measure transition follows, which foreshadows the first episode’s borrowed d’ theme in the viola, counterpointed by a reference to Pa.1 in the cello.

Example 17. The second episode of the local rondo in Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet, featuring counterpoint between themes from P, Tr, and S of the sonata form as well as the trio’s b theme

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 9. The second episode of the local rondo, mm. 1181–94

Example 18. The rondo’s final refrain in Schoenberg’s op. 7 Quartet, in which the rondo theme and its own contrasting theme are placed in counterpoint

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Audio Example 10. The rondo’s final refrain, preceded by the end of the previous episode, mm. 1245–57

Audio Example 11. Excerpts from the coda and the coda-to-the-coda, mm. 1274–88 and mm. 1303–end

[5.7] In the first half of the first episode (mm. 1150–68; M.29), the thematic content is restricted to a version of the adagio’s contrasting theme, d (see mm. 1003ff; K.52). The pitch center, having launched in E major, descends through a minor-third cycle of keys before returning to E on the downbeat of m. 1158 (M.37). Subsequently, the b theme from the trio is referenced in the violins, before a rhythmic allusion to Pb drives the music to the punctuated C-major harmony at m. 1165 (M.44). The short burst of energy that ensues is a retransition preparing the second refrain. Serving as an embedded mirror, the d’ episode of the local rondo employs markedly similar techniques to the scherzo and second development that function as the large-scale Episode I and retransition. Both of these passages are largely developmental in nature, employing cyclic transposition, rhythmic intensification, and similar thematic content. The second refrain that follows is brief, arguably a formality, reflective of the short refrain of the overarching rondo that appears at m. 909: here, the rondo theme recurs in the A-major tonic of the local rondo, is truncated to eschew much of the thematic counterpoint of the initial refrain, and leads after twelve measures to the second, more developmental episode.

[5.8] The rondo’s e episode, spanning mm. 1181–247 (N.1–67), functions akin to a development, combining components of themes from across the entire Quartet. As shown in Example 17 and Audio Example 9, the section begins with the Tr1 theme in counterpoint with Sa in the cello and motives from Pa.1 in the violin 2. The trio’s main theme, b, appears in m. 1189 before a return to the episode’s initial combination of themes at m. 1195 (N.15). The counterpoint persists until m. 1208 (N.28), when the Pa.1 theme occurs first in

[5.9] To close the Quartet, a substantial coda follows the rondo finale. In D major, the coda continues the counterpoint of themes from across the piece, beginning with references to the slow movement in the cello, to the scherzo in the viola, and to the trio in the violin 2. The Pa.1 theme arrives in D at m. 1274 (O.5), with its Pa.2 contrapuntal partner in all lower strings (see Audio Example 11). A second iteration follows eight measures later, interrupted by the scherzo theme. The D–A pedal in the cello at m. 1288 (O.19) signals tonal stasis as a third statement of Pa.1 passes from viola to violin 2 to violin 1, before the music dissolves and the dynamics lower to the pp D-major harmony at m. 1308 (O.39). In the context of the large-scale coda, the arrival of the Pa.1 theme in the cello at m. 1308 signals the end-of-the-end, the coda-to-the-coda in Keller’s interpretation ([1974a] 1999, 14). In the dimension of the cycle, the large-scale coda is necessary after the rondo finale. It provides the final refrain, following the episode that included the slow movement and rondo. The coda-to-the-coda thus responds to this final refrain with a sense of stasis, the music progressing slowly and with minimal counterpoint. Following the program, this moment offers a sense of “quiet joy and the contemplation of rest and harmony.” The piece closes with three statements of the D-major tonic, the violin 1 ascending two octaves on the

6. Epiphany and the Quartet’s Modernist Urban Subject

[6.1] Not unlike the Ringstrasse in Vienna, the Place Charles de Gaulle in Paris is a monumental feat of urban planning. At the center lies the Arc de Triomphe. Twelve avenues and three arrondissements converge on a circle 240 meters in diameter. Prior to 1970, the location was known as the Place de l’Ètoile, which may have inspired Marcel Proust’s metaphor of “star-shaped crossroads” (“étoiles des carrefours”). Just as roads converge at and radiate from the Arc, for Proust, ideas form networks of the mind: “The fact is that from each of our ideas, as from a crossroads in a forest, so many paths branch off in different directions that at the moment when I least expected it I found myself faced by a fresh memory.”(43) Gerald Gillespie’s account of epiphany in Proust finds its source in this same metaphor: “like persons and societies, artworks are ‘real’ intersections in time.