Rotational Principle as Teleological Genesis in the “Annunciation of Death” Scene from Wagner’s Die Walküre

Ji Yeon Lee

KEYWORDS: Richard Wagner, Die Walküre, opera, rotational form, teleological genesis

ABSTRACT: Structured as a dialog, the “Annunciation of Death,” a duet in Act 2, Scene 4 of Wagner’s Die Walküre, centers on the changing dramatic relationship between Brünnhilde and Siegmund. A hardhearted, obedient warrior at the beginning of their first encounter, Brünnhilde learns sympathy and compassion from Siegmund’s profound love for Sieglinde; this knowledge transforms her into the woman who eventually sacrifices herself through love to redeem the divine world at the end of the cycle. The article examines how this narrative dynamic is reflected in the musical architecture. It reads the scene’s overarching form as a three-stage process in which the characters struggle for narrative control, from Brünnhilde’s declaration of Siegmund’s fate to his rewriting of that fate in his favor. The rotational principle is the primary formal function clarifying the transformations and interactions of leitmotifs in the playing-out of the dramatic narrative. The article thereby demonstrates the effectiveness of the rotational principle for understanding the scene’s teleological process as embedded in the music and drama.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.28.2.5

Copyright © 2022 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[1.1] The “Annunciation of Death” scene, a dialogic duet for Siegmund and Brünnhilde in Act 2, Scene 4 of Wagner’s Die Walküre (152/4/1–172/4/1), is a dramatic turning point in the Ring cycle.(1) The warrior goddess Brünnhilde appears to the mortal Siegmund to deliver the decree that he shall die in an upcoming battle. However, as Siegmund expounds upon his history with and feelings for his lover and sister Sieglinde, Brünnhilde’s resolve weakens, and she ultimately decides to defy her orders and save Siegmund from his fate. Moreover, the sympathy and love she gains through this encounter ultimately motivates her later great deeds, culminating in her world-redeeming self-sacrifice at the end of Götterdämmerung.(2)

[1.2] Owing in part to its pivotal role within the unfolding plot, the scene has attracted much scholarly attention. Four scholars in particular—Alfred Lorenz (1924), Thomas Grey (1995), Matthew Bribitzer-Stull (2016), and Karol Berger (2016)—provide considerable insight into the scene’s musical structure.(3) All of these analytical precedents read the scene as a three-part form and illuminate important facets of the scene’s structure. None, however, closely inspects the relationship between Wagner’s textual and musical organization on both the global and foreground levels. A new analytical approach is therefore necessary to fully appreciate the extensive dynamism of scene’s drama and music: as Siegmund and Brünnhilde struggle for narrative control, their power dynamic gradually changes in the course of time—and thus within the course of the scene’s musical organization.(4) This article explains how the musical form of the scene closely mirrors and even embodies the changing narrative between the two characters. Rather than reading the scene’s form in terms of a fixed formal template, this approach views it as a dynamic process animated by deliberate textual and musical interaction.(5) Indeed, the essence of Wagner’s music drama lies in this reciprocal relationship. The textual content and its formal organization shape the musical structure, while the musical structure transforms the text into sounding form. My analysis consequently presents Wagner’s structural design as a continuously changing process, an instance of Wagner’s art of transition.(6)

[1.3] In the following analysis, I first examine the dramatic structure of the scene, which acts as the basis for the musical form. I follow this with an analysis of the scene’s musical and textual organization, which relies heavily on the rotation principle. I take leitmotifs as the principal rotational criteria, tracing their transformation to establish the rotational principle in the music. I then proceed to an in-depth analysis of the scene as a three-part structure, focusing throughout on the close intertwining of the rotational principle and dramatic narrative in the scene’s teleological progression.

Dramatic Structure and Three-Part Form

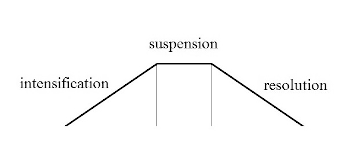

Example 1. Dramatic structure as ABA’ form

(click to enlarge)

[2.1] The dramatic structure of the scene will ground my analysis of its textual and musical form. Its dramatic structure resembles a ternary ABA’ form, which is dominated by the tense conflict between Sigmund and Brünnhilde. As shown in Example 1, the scene’s tension rises, plateaus, and then decreases in a three-stage process denoted as intensification, suspension, and resolution. At the same time, the narrative progression imbues the scene with goal-oriented directionality, moving from Brünnhilde’s initial control of the situation to Siegmund’s victory at the end.(7)

[2.2] In Stage 1, the dramatic tension increases as Siegmund steadfastly faces the divine messenger Brünnhilde and presses her for the information most important to him. The buildup of tension is due to Siegmund’s gradual redirection of the topic, from Brünnhilde’s presentation of the promised afterlife in Valhalla to his overriding interest in Sieglinde; it culminates with his direct question as to whether Sieglinde will be with him. Upon receiving an unsatisfactory answer, Siegmund suspends this narrative progression in Stage 2 by resolutely refusing any fate that separates him from Sieglinde; in turn, Brünnhilde obstinately reminds him of his inescapable death. Neither advances nor retreats from their position. The narrative progression resumes in Stage 3. As the questioner-questioned roles flip, Brünnhilde gradually bends to Siegmund’s demands, and, in doing so, resolves all adversarial tension.(8)

[2.3] Siegmund’s gradual persuasion of Brünnhilde and her burgeoning sympathy is coordinated with the recurring question-answer format of the text: Siegmund questions Brünnhilde on his fate in Stage 1, while Brünnhilde becomes the questioner in Stage 3. Notably, the back-and-forth dynamic established by the dialog also distinguishes the scene from the linear narrative style of text delivery that is typically predominant in Wagner’s music dramas. Rather than looking backward or pausing the drama of the scene, the question-answer process produces strong, forward momentum in real time. Wagner uses the rotational principle alongside a teleological process to musically articulate this progressive organization.

Rotational Principle and Teleological Process

[3.1] Leitmotifs provide the basis for the scene’s rotational form. The motivic play is not, however, simply caused by or dependent on the dramatic content. Gradual intra- and inter-motivic changes form musically recurring patterns within the larger three-part context, most clearly in Stages 1 and 3. This balance between recurrence and change in the motivic play can be clearly explained through rotational principle.

[3.2] Rotational form is one of the most frequently used analytical tools applied to Wagner’s music dramas. The concept derives from James Hepokoski’s analysis of Sibelius’s symphonies (1993). In rotational form, a referential unit consisting of a series of themes or motives recurs cyclically, reworked with each appearance.(9) Although observed primarily in sonata form analysis, scholars have used the rotational principle in analyzing non-sonata forms as well.(10) Thematic or motivic content plays a critical role in the rotational workings of both sonata form and Wagner analysis. In the latter, the dramatic content is often read in terms of and/or coordinating with the activity of leitmotifs.(11)

[3.3] A rotational process may result from something as simple as a reiteration or variation of a referential statement. However, it can also be progressive and develop toward a telos, a goal point achieved through gradual intensification or buildup of initial thematic or motivic content. In such a teleological genesis, the rotational proceedings are analogous to organic growth from seed, to germination, blossom, and full fruiting.(12)

[3.4] The strong directionality that teleological genesis conveys readily maps onto certain narrative types, such as heroic achievement or per aspera ad astra. Hepokoski holds that when a rotational structure is combined with teleological genesis, it produces an elemental, mythic effect, akin to ritualistic preparation for the birth of something new (1993, 26). The Annunciation of Death scene is particularly well suited to such a teleological reading, as the narrative is basically a process of persuasion, in which Siegmund and Brünnhilde set out to achieve their conflicting ends by convincing the other of their rightness. No visually or physically remarkable event on the stage depicts this; there is only the two characters’ rhetorical battle of wills. Yet this clash must come to an all-or-nothing end, as Siegmund rejects any compromise. The moment when the winner is declared thus embodies the telos.

Example 2. Three-part structure of the Annunciation of Death scene

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] The Annunciation of Death scene exhibits teleological process on two levels. At the large-scale, the scene proceeds as a revelatory process of rotational operation, with the telos proper at the end. In the interior of each of the outer stages, the rotations clearly advance the drama toward the goal point. Example 2 provides an overview of the scene’s structure in terms of its formal division, rotational function based on leitmotifs, narrative mastery, tension trajectory, and the location of the telos proper.

[3.6] Leitmotiv plays an essential role in determining sectional division. Each rotation in the A and A’ sections starts with the Question motive.(13) The referential module in A consists of the Question motive and the motives related to divinity; that in A’ consists of the Question motive followed by the Freia and/or the Love motive. The rotational function comes to a standstill in the B section, where the previously established referential unit is now absent. The section below investigates the process by which specific musical attributes and the semantics of the leitmotifs generate the rotational form.

Leitmotifs as the Primary Rotational Criterion

[4.1] The analytical approach advanced in this article views leitmotifs as fundamental to the rotational operations taking place in both small- and large-scale formal divisions. The form-generating function of leitmotifs derives from continual variation in their shape and semantic meaning, as opposed to their fixed associations. Individual leitmotifs continually transform and interact with each other over the course of the scene, and this leitmotivic work drives the textual narrative.(14) Consider, for example, the Fate motive. Even as it initiates each stage, its semantic meaning changes each time along with dramatic progression.

Example 3a. Question motive

(click to enlarge)

[4.2] The Question motive is the primary motive in the scene’s rotational process. It first appears in 152/5/3–152/5/6 (Example 3a). Over the course of the scene, the motive goes through considerable changes, for example in character assignment, topical gesture, mode, melody, rhythm, instrumentation, and signification (see Appendix 2 for the motivic transformations).(15) The Question motive, based partially on a stock interrogative gesture, first appears as a musical question. Yet that form and function will be modified by the end of the scene, which contributes to the rising dramatic intensity and suspense throughout.

[4.3] The motive is also flexible in terms of its character as sung and its rhetorical significance. In general, when a motive or theme is repeated in an operatic work, its meaning often changes depending on which character sings it and the context in which they do so. The Question motive, for example, is commonly understood as a fixed signifier for Siegmund and his death. However, the motive’s initially elegiac quality gradually disappears as Siegmund gains controlling power.(16)

Example 3b. Fate motive

(click to enlarge)

[4.4] Despite these shifts, one aspect of the Question motive remains unchanged throughout; it is fundamentally about Siegmund’s fate, tragic or otherwise. In this regard, it is highly meaningful that the Question motive contains the Fate motive (Example 3b), despite their different harmonizations. The Fate motive’s melodic line—a descending minor second followed by an ascending minor third—appears in mm. 2–3/2 of the Question motive’s original form and is sequenced a whole step higher in mm. 3–4.(17) This melodic entanglement intimates the Question motive’s dramatic purpose beyond merely signifying “interrogation”: regardless of who carries the Question motive at any given point, the Fate motive is the key to its transformations. Indeed, even as the Question motive’s harmonic and rhythmic profile is considerably altered by the scene’s conclusion, the Fate motive’s melodic trace remains. In this sense, the Fate motive is revealed as the inevitable, core component of the Question motive.

[4.5] The other motives that shape the musical-dramatic form may be classified into two categories, based on their semantic relation to Siegmund. Those in the first category clash with Siegmund’s interests and will: these are the Valhalla and Walküre motives, both representing divinity. These motives are salient in Stage 1, appearing without conspicuous musical or semantic alteration; moreover, their identification and signification is generally uncomplicated, since they are not incorporated with other motives.

Example 4. Freia motive consisting of x and y

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Love motive, from the Freia motive

(click to enlarge)

[4.6] The motives in the second category symbolizes Siegmund’s priorities: these are the Freia and Love motives. The name of the Freia motive notwithstanding, both motives symbolize Siegmund’s overwhelming love for Sieglinde as well as what this love entails. In its original statement, the Freia motive consists of a preparatory gesture, x, and a main phrase, y (Example 4). The y phrase later transforms into the first part of the Love motive, y’, which is followed by a second part, z Example 5).(18) Both motives undergo considerable musical alteration over the course of the scene, feeding the contradictory elements of pain and pleasure engendered by Siegmund and Sieglinde’s love. This is particularly notable in Stage 3 (164/2/1–172/4), where the Freia and Love motives are distorted. The soaring, exciting diatonic melody of Freia motive’s x portion is transformed into an anxious chromatic ascent of scalar triplets. Furthermore, although the x portion is initially an introduction for the y phrase, it eventually appears as a singular motivic fragment.

The A Section, Stage 1: Brünnhilde’s Narrative Mastery and Rise in Tension

Example 6. Analysis of Stage 1 (152/4–159/1/1)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[5.1] In Stage 1 (152/4–159/1/1), the dialog between Siegmund and Brünnhilde takes the form of an end-accented climax structure for Siegmund, with him gradually steering the topic from her statement to his own concerns. The scene plays out over six musical rotations, bookended by a prologue and epilogue. Example 6 outlines its rotational structure, while accounting for the scene’s dialog format.

[5.2] Stage 1 features periodicity and predictability from rotation to rotation, as Brünnhilde formally—and formulaically—tells Siegmund of his fate. With one exception, each rotation opens with Siegmund singing the Question motive and continues with Brünnhilde responding with divinity-related motives; Rotation 6, the final rotation of Stage 1, contains the Question motive only. Siegmund’s questions frequently end with half cadences, reflecting his status as an information-seeker. By contrast, all of Brünnhilde’s answers conclude with either an IAC or PAC, in accordance with her role as envoy and information-provider.

[5.3] The first prologue (152/4–154/1/2) is in bar form (aa’b), with the two a sections further divided into smaller bar forms by means of motivic deployment. In the b section, the orchestra presents the Valhalla motive in the associative tonality

[5.4] The arrival of Rotation 1 (154/1/3–154/4/4) marks the onset of the main drama. Siegmund asks for Brünnhilde’s identity over the Question motive in its original form—in

[5.5] After a short transition in unison in the low strings (154/4/5–155/2/3), Rotation 2 (155/2/4–155/4/4) begins with Siegmund asking about Valhalla. The overall shape of the Question motive is maintained, but the half-cadential ending is replaced with a plagal motion, still in

[5.6] Brünnhilde’s message receives further emphasis through motive and cadence in Rotation 3 (155/4/5–156/2). Picking up the E from the orchestra, Siegmund wonders if he will see Walvater in Valhalla. His dialog is delivered over the Question motive sounding in A minor and ending on a half cadence in F. Brünnhilde answers that other fallen heroes will welcome Siegmund, over a combination of the Valhalla and the Walküre motives. Her answering music concludes with a resolute PAC, in D major; this is her first PAC demarcation, reflecting her omniscient assurance of his welcome in the divine world.

[5.7] Rotation 4 (156/3–156/4/2) essentially restates Rotation 3 without the Walküre motive.(20) Siegmund asks whether he will see his father, Wotan, as the Question motive is heard in B minor, ending on V7/E; Brünnhilde’s affirmative reply uses the complete form of the Valhalla motive in C major. Her vocal line again comes to a PAC, while the orchestra ends with the Valhalla motive’s IAC.

[5.8] Encouraged by Brünnhilde’s answers so far, in Rotation 5 (156/4/3–157/3/3) Siegmund advances the drama by raising questions about his main concern. Inquiring whether “a woman” will greet him in Valhalla, he sings the full Question motive in A major with orchestral support. This new key recalls Rotation 3, where Siegmund asked in A minor if he will see Walvater “alone.” The subtext of that question—whether he will see or be accompanied by others—is now articulated slightly more explicitly in the parallel major, ending on V7/D—as if he expects Brünnhilde’s PAC in D major confirmation again.

[5.9] Brünnhilde, missing the subtext, answers that Wotan’s daughters will expect Siegmund. The sudden chromatic shift from A to

[5.10] Dissatisfied with Brünnhilde’s grandiose but to him empty answer, Siegmund in Rotation 6 (157/5/5–158/3/1) finally asks whether he will see Sieglinde in the afterlife. This poignant question, and its importance to him, receives significant musical and dramatic preparation in the transition (157/3/4–157/5/4). First, as Siegmund prepares to ask it (“tell me one thing, you immortal”), the orchestra gears up for the

[5.11] Brünnhilde’s answer, that Sieglinde cannot accompany him, lays bare the clash between their respective interests and intimates the ensuing tug-of-war for narrative dominance. Unlike other rotations, Brünnhilde’s answer embraces neither the Valhalla nor Walküre motive, proceeding only as an extended cadential punctuation. As in Rotation 5, Brünnhilde shifts the bass line a semitone down from Siegmund’s B to her

[5.12] In the epilogue that follows, part of the Love motive accompanies Siegmund as he kisses the slumbering Sieglinde. No more rotations will occur, since Siegmund has no more questions to ask of Brünnhilde; he merely summarizes what she has told him over the Valhalla motive. The established pattern of the rotations—with Siegmund questioning over the Question motive and Brünnhilde answering over divinity-related motives—works steadily throughout Stage 1 to signal Brünnhilde’s command of the narrative situation. Nonetheless, Siegmund’s gradual self-assertion regarding his real concerns, as well as, crucially, his agency in stopping the ongoing rotational process, sets up the struggle between the two characters that will manifest more fully in Stage 2.

The B Section, Stage 2: Dramatic Stalemate and Rotational Suspension

Example 7. Analysis of Stage 2 (159/1/2–164/1)

(click to enlarge)

[6.1] The narrative struggle between Siegmund and Brünnhilde reaches a plateau in Stage 2 (159/1/2–164/1), as the conflicting purposes of the characters produce a stalemate. Siegmund’s role changes from listener to aggressive challenger; now when asking Brünnhilde more questions, he is not so much soliciting information as attempting to turn the narrative tables. As such, Stage 2 presents a contest in which Siegmund seeks to enact his will. No less willful, Brünnhilde does not budge from her role as Wotan’s untouchable messenger—at least in her words. Example 7 shows an analysis of Stage 2 that traces both the leitmotivic content and the dramatic tug-of-war between the two characters.

[6.2] In Stage 2, the dramatic stalemate involves the temporary suspension of the rotational operation. This stage is divided into three sections, according to dramatic progression. Section 1 (159/1/2–160/4/3) is initiated with Siegmund’s first declaration of his refusal to go Valhalla, followed by Brünnhilde’s relentless reminder of his inescapable fate.(24) Section 2 (160/4/4–162/3) reopens their argument, once more resuming the question-and-answer format. In Section 3 (162/4–164/1), Siegmund reaffirms his decision, despite his new knowledge that the sword will not save him.

[6.3] Throughout this stage, the Fate motive prevails.(25) In Section 1, which is structured aba’, a Fate-Fate-Question module constitutes the first and last subsections and Love-Fate-Fate the middle subsection. Over this ordinary three-part form, however, a significant turning point in Siegmund and Brünnhilde’s dramatic struggle occurs: Brünnhilde assumes the Question motive for the first time at 159/2/2.(26) She does not ask a question, but only repeats her message about Siegmund’s doom. Her Question motive therefore does not land on a half cadence, instead progressing to diminished seventh chords and E minor triads through a chromatic descent in the bass (

[6.4] The question-answer dialog format momentarily returns in Stage 2, Section 2, although it is not extended to the point that it resumes the rotational procedure. The circumstances are, in fact, considerably different than that in Stage 1, due to Siegmund’s changed attitude and the intent of his questioning. His inquiries regarding his foe and sword are not a matter of curiosity, but a challenge to Brünnhilde’s proposed narrative. As such, Siegmund does not carry the Question motive, instead singing in a declamatory manner over the Fate and Sword motives in the orchestra.(27)

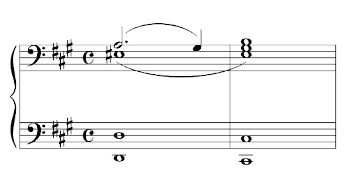

Example 8. Love motive, distorted

(click to enlarge)

Example 9. Freia motive, distorted

(click to enlarge)

[6.5] In Section 3, solely sung by Siegmund, the Question and Fate motives disappear from both the voices and orchestra. Only the Love and Freia motives appear in this section, both significantly distorted. With Brünnhilde successfully parrying his challenges, Siegmund’s realization of his adversity and intensified psychological struggle are expressed in an even stronger declamation and more intense chromaticism. A chromatically altered, triplet-contoured Love motive (Example 8) provides a counterpart to Siegmund’s lamentation at the beginning of this section. In its first entrance in distorted form, from 163/3/2, this triplet rhythm becomes the chromatically altered anacrusis of the Freia motive (Example 9).

The A’ Section, Stage 3: Siegmund’s Victory and Tension Resolution

[7.1] The tension between Brünnhilde and Siegmund eventually dissolves in Stage 3, as Siegmund’s stalwart dedication to Sieglinde gradually sways Brünnhilde. Where Brünnhilde repeatedly missed Siegmund’s intent in Stages 1 and 2—his need to be with Sieglinde, above all —in Stage 3 she comes to understand him; the shift is signaled as she adopts the questioning role he initially occupied, along with his Question motive. The form of the questioning changes as well, as Brünnhilde this time pursues her inquiry through suggestion, testing out what will meet Siegmund’s approval.

Example 10. Analysis of Stage 3 (164/2/1–172/4)

(click to enlarge)

[7.2] The resumption of the rising tension arc restarts the rotational process as well, with Siegmund’s ascendency telegraphed by a remarkable change in the music. As in Stage 1, each rotation is initiated by the Question motive. However, it is now incorporated with the Freia motive and its derivative, the Love motive, which together encompass Siegmund’s motivation and the reason for all his deeds. These two motives become part of the primary leitmotivic module for this stage. Example 10 summarizes the rotational structure of Stage 3, both in terms of its motivic content and the shifted functional roles of questioner and answerer.

[7.3] The prologue of Stage 3 (164/2/1–164/4) is initially quite similar to that of Stage 1; Brünnhilde sings alone over the two statements of the Fate motive in Tempo I. But in stark contrast to the Stage 1 prologue’s imperative (“Siegmund! Look on me!), she not only asks a question proper for the first time, but does so three times in a row.(28)

[7.4] Brünnhilde’s growing sympathy and Siegmund’s wresting of narrative control is mirrored by a shift to the Fate-Fate-Freia motivic module, which anticipates the Freia motive’s enhanced role in the upcoming rotations. The Fate motive’s second statement dissolves to an enervating gesture at 164/3/1, which repeatedly ascends only to descend again.(29) At 164/4/2, Brünnhilde’s final note initiates the Freia motive on V/

[7.5] Rotation 7, sung by Siegmund alone, is a dramatic enhancement in terms of the protagonist’s reaction. Siegmund’s full resolve in facing his fate is on display in force, as he goes so far as to scold Brünnhilde for being cold and merciless. This dramatic situation is reflected in Rotation 7 as a musical intensification of part of Rotation 6. Where Siegmund’s Question motive was earlier presented first in

Example 11. Analysis of Rotation 7 (165/1/1–166/2/4)

(click to enlarge)

[7.6] We note further that, although Siegmund takes up the Question motive again here, it is neither a textual nor musical question any longer. First, the rhythmic shape of the Question motive in

[7.7] Rotation 8 (166/3–167/2) repeats the Question-Freia module of Rotation 7. Brünnhilde opens the rotation with Variant 1 in A minor (166/3/1–166/3/2) and follows it with Variant 2 (166/3/3–166/3/4). Her adoption of Siegmund’s Rotation 7 music reflects her new inclination to address his concerns, which she does by suggesting that Siegmund commend Sieglinde to her care. However, Siegmund rejects this outright. Accordingly, Brünnhilde’s attempt to make a PAC in D major is evaded by the Freia motive’s early entry at 167/1/2, as Siegmund declares that he will kill Sieglinde and himself if he is doomed to die.

[7.8] Another Question-Freia module (and another suggestion-rejection) occurs in Rotation 9 (167/3/1–168/4/2), with the leitmotivic content varied. Brünnhilde now expands her suggestion to include protecting Sieglinde and the unborn baby. The orchestra accompanies this offer with Variant 3 of the Question motive, which transposes the first four notes of Variant 2 in sequential motion (167/3/1–167/3/2). The orchestra follows this with the Love motive’s y portion at 167/3/3, which is the first time it is tied to Brünnhilde.

[7.9] As Siegmund declares his answer, the Love motive proceeds to the x portion of the Freia motive over V7/Am (167/4/4). The orchestra plays the turbulent triplet rhythm and tremolos derived from the distorted Freia motive, carrying the urgency of Siegmund’s extreme action as he attempts to kill Sieglinde. The Sword motive briefly emerges at 168/2/4 as he points Nothung at Sieglinde, but the orchestra soon dissolves into the restless trills.(32)

Example 12. Rotation 10 (168/4/3–172/4)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 13. Analysis of Rotation 10 (168/4/3–172/4)

(click to enlarge)

[7.10] Rotation 10 (168/4/3–172/4, Example 12) finally brings about the telos proper of the scene, in which the dramatic process concludes with Siegmund’s victory. Dramatically, the telos is a fulfillment of Siegmund’s determination to stay with Sieglinde as Brünnhilde confirms that she will make this happen. Musically, the telos arrives at the final phase of the leitmotivic transformation, exhibiting the highest energy of the teleological process in terms of rhythm and tempo and the use of major mode. Formally, the telos in its expanded structure caps off all of the foregoing rotational development. The final rotation creates its own nested rotational structure, producing an overarching aba’ form (a, 168/4/3–170/2/1; b, 170/2/2–171/1/3; a’, 171/1/4–172/4). The a and a’ sections go through four and three subrotations respectively, each of which is based on the Question-Freia module. This referential module momentarily disappears at the beginning of the b section, despite the Freia motive’s reemergence at 170/4/4 (The process here mirrors the suspension of the rotational operation during Stage 2 and its resumption in Stage 3). See Example 13; this three-part structure of the final rotation also corresponds to Brünnhilde’s dramatic actions. These are her announcement that she will save Siegmund (a), her encouraging him (b), and her exit from the stage, followed by the orchestral postlude and scene change (a’).

[7.11] The first a section centers the Question-Freia module with a radical transformation of the Question motive.(33) As such, the final transformation of the Question motive, Variant 4, features maximum rhythmic diminution and melodic truncation, resulting in a soaring gesture that contrasts sharply with its originally morbid character. The first subrotation, r1 (168/4/3–169/2/2; mm. 3–10), opens with Variant 4, which is then combined with embellished Variant 2 and the exact return of Variant 3. The inversion of the x part of the Freia motive then enters. A similar but slightly altered process continues in the following subrotations: r2 (in

[7.12] The Question-Freia module briefly disappears at the beginning of the b section, but returns in a’: r5 (171/1/4–171/3/1; mm. 44–50) consists of Variant 4, Variant 2, and the inversion of the Freia motive’s x part, while r6 (171/3/2–171/4/1; mm. 51–54) is comprised of Variant 4 and the Freia motive’s y part. Subrotation r7 (171/4/2–172/4; mm. 55–78) incorporates Variants 4 and 2 and the y portion of Freia motive in extended measures. The music then seamlessly transitions to scenic change over the Fate motive and the Love motive’s z part. The Annunciation of Death scene arrives at its conclusion without a clear cadence or cadential gesture except for the return of the Fate motive, which signals the end of the motivic module and, thus, the end of the rotational process.

Conclusion

[8.1] The question-answer dialog in the Annunciation of Death scene is an essential component of its musical architecture. The rotational structure, as viewed in terms of an early-established referential module, has been shown to be an effective analytical prism with which to parse the form and drama. That being said, the increasing flexibility with which the involved motives and the rotational operations are treated defies any static, one-dimensional formal template. Indeed, the rotational process in the scene essentially precludes a fixed arrangement of the motives. It is not merely a matter of the questions and answers being regularly exchanged, but rather of the transformations and interactions among the motives being minutely integrated into the dynamic dramatic narrative.

[8.2] The dynamic treatment of the leitmotifs affects not only their identification and nomenclature, but also the extent to which they may be used for sectional division, and thus formal understanding. By tracing how the motives evolve as they create rotational structures, the present analysis extends the findings of its predecessors by delving into leitmotivic morphology beyond surface similarity and difference. The Question motive, the leading motivic agent in the rotational operation, for example, evolves from its original form into a drastically altered shape, transfiguring its signification from the godly imperatives of death, interrogation, and fate’s inexorability to Siegmund’s insistence on life, confidence, and self-determination. Likewise, the Freia motive shifts from the distressed urgency surrounding the Wälsung couple to Siegmund’s triumph and joy at the end of the scene. The rotational principle thereby enhances our understanding of the dynamic playing-out of the motives and their meanings, and of how they create dramatic immediacy and continuity as part of a teleological process. In this drama-generating process, the rotational journey of the scene can be appraised as a realization of Wagner’s art of transition, thereby distinguishing his use of rotational principle from that found in non-theatrical works by other composers.

Appendices

Appendix 2: Question motive and its transformations

Ji Yeon Lee

University of Houston

Moores School of Music

3333 Cullen Blvd.

Houston, TX 77204

jlee136@uh.edu

Works Cited

Abbate, Carolyn. 1989. “Wagner, ‘On Modulation’, and Tristan.” Cambridge Opera Journal 1 (1): 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954586700002755.

Bailey, Robert. 1977. “The Structure of the ‘Ring’ and Its Evolution.” 19th-Century Music 1 (1): 48–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/746769.

BaileyShea, Matthew. 2002. “Wagner’s Loosely Knit Sentences and the Drama of Musical Form.” Intégral 16–17: 1–34.

Berger, Karol. 2016. Beyond Reason. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520292758.001.0001 .

Bribitzer-Stull, Matthew. 2001. “Thematic Development and Dramatic Association in Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen.” PhD diss., Eastman School of Music.

—————. 2016. “Die Geheimnisse der Form bei Richard Wagner: Structure and Drama as Elements of Wagnerian Form.” Intégral 30: 81–98.

Cooke, Deryck. 1979. “Wagner’s Musical Language.” In Wagner Companion, edited by Peter Burbidge and Richard Sutton, 225–68. Cambridge University Press.

Darcy, Warren. 1990. “A Wagnerian Ursatz; Or, Was Wagner a Background Composer After All?” Intégral 4: 1–35.

—————. 1994. “The Metaphysics of Annihilation: Wagner, Schopenhauer, and the Ending of the Ring.” Music Theory Spectrum 16 (1): 1–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/745828.

—————. 2001. “Rotational Form, Teleological Genesis, and Fantasy-Projection in the Slow Movement of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony.” 19th-Century Music 25 (1): 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1525/ncm.2001.25.1.49.

—————. 2005. “’Die Zeit ist da’: Rotational Form and Hexatonic Magic in Act 2, Scene 1 of Parsifal.” In A Companion to Wagner’s Parsifal, edited by William Kinderman and Katherine Syer, 215–41. Camden House.

Davis, Andrew, and Howard Pollack. 2007. “Rotational Form in the Opening Scene of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 60 (2): 373–414. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2007.60.2.373.

Donington, Robert. 1974. Wagner’s Ring and its Symbols. Faber & Faber.

Grey, Thomas. 1995. Wagner’s Musical Prose: Texts and Contexts. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511470301.

Harper-Scott, J. P. E. 2005. “Elgar’s Invention of the Human: Falstaff, Opus 68.” 19th-Century Music 28 (3): 230–53. https://doi.org/10.1525/ncm.2005.28.3.230.

—————. 2009. “Medieval Romance and Wagner’s Musical Narrative in the Ring.” 19th-Century Music 32 (3): 211–34. https://doi.org/10.1525/ncm.2009.32.3.211.

Hepokoski, James. 1993. Sibelius, Symphony No. 5. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511620188.

—————. 1996. “The Essence of Sibelius: Creation Myths and Rotational Cycles in Luonnotar.” In The Sibelius Companion, edited by Glenda Dawn Goss, 121–46. Greenwood Press.

—————. 2004. “Structure, Implication, and the End of Suor Angelica.” Studi Pucciniani 3: 243–66.

—————. 2010a. “Clouds and Circles: Rotational Form in Debussy’s Nuages.” Dutch Journal of Music Theory 15 (1): 1–17.

—————. 2010b. “The Second Cycle of Tone Poems.” In The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss, edited by Charles Youmans, 78–104. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL9780521899307.006.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195146400.001.0001.

Hunt, Graham. 2007. “David Lewin and Valhalla Revisited.” Music Theory Spectrum 29 (2): 177–96. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2007.29.2.177.

Lorenz, Alfred. 1924. Das Geheimnis der Form bei Richard Wagner, Vol. 1: Der musikalische Aufbau des Bühnenfestspieles Der Ring des Nibelungen. M. Hesse.

McClatchie, Stephen. 1998. Analyzing Wagner’s Operas: Alfred Lorenz and German Nationalist Ideology. University of Rochester Press.

Monahan, Seth. 2007. “Inescapable Coherence and the Failure of the Novel-Symphony in the Finale of Mahler’s Sixth.” 19th-Century Music 31 (1): 53–95. https://doi.org/10.1525/ncm.2007.31.1.053.

—————. 2011. “Success and Failure in Mahler’s Sonata Recapitulations.” Music Theory Spectrum 33 (1): 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2011.33.1.37.

—————. 2014. “Negative Catharsis as Rotational Telos in Mahler’s First ‘Kindertotenlied.’” Intégral 28–29: 13–51.

Moynihan, Sarah. 2018. “Sibelius and Material Formenlehre: Projections beyond the Edges of Musical Form.” PhD diss., Royal Holloway, University of London.

Newcomb, Anthony. 1981. “The Birth of Music out of the Spirit of Drama: An Essay in Wagnerian Formal Analysis.” 19th-Century Music 5 (1): 38–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/746558.

Spencer, Stewart, and Barry Millington, eds. 2000. Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung: A Companion. Thames & Hudson.

Tarasti, Eero. 2012. Semiotics of Classical Music: How Mozart, Brahms and Wagner Talk to Us. Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614511410.

Wagner, Richard. 1905. Richard Wagner to Mathilde Wesendonck. Translated by William Ashton Ellis. H. Grevel.

Weiner, Marc. 2014. “The Political in Opera.” In The Oxford Handbook of Opera, edited by Helen M. Greenwald, 706–31. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195335538.013.032.

Wolzogen, Hans von. 1895. A Guide Through the Music of Richard Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung. Translated and edited by Nathan Haskell Dole. Schirmer.

Footnotes

1. In this article, measure indications follow page/system/measure in Schirmer vocal score of Die Walküre. The Schirmer vocal score is publicly accessible on two websites: Indiana University’s Variations Prototype website hosts a copy of the score (https://dlib.indiana.edu/variations/scores/bhr9607/large/index.html); IMSLP includes it alongside a table of leitmotifs. Note that its page numbers are different from those of the physical copy (https://s9.imslp.org/files/imglnks/usimg/d/d1/IMSLP16815-Wagner_-_Die_Walk%C3%BCre_(vocal_score).pdf).

Return to text

2. Several scholars have noted the dramatic significance of the Annunciation of Death scene in Die Walküre and the Ring cycle: Robert Bailey holds that it is “the crucial scene in Act 2 of Die Walküre where the two stories of the opera come together each with a decisive effect on the outcome of the other. The Siegmund-Sieglinde story reaches its crisis with Siegmund’s fatal decision, and the future of the Brünnhilde-Wotan story is determined by the change in Brünnhilde’s character that results from her confrontation with Siegmund” (1977, 55). In a similar vein, Karol Berger appraises the scene as “one of the artistic high points of the cycle, one of those scenes that compel us to take seriously Wagner’s pretentions to be the reviver of Attic tragedy. For the first time, in the Ring we witness directly the devastating mythic encounter between a human and a divine power, an encounter of momentous consequences to both, since it brings death to the human and transforms the divine” (2016, 103). Likewise, Eero Tarasti mentions that “the most essential dramatic event in the second act of Die Walküre is Brünnhilde’s change of mind,” in which the Annunciation of Death scene plays a key role (2012, 198).

Return to text

3. These four scholars analyze the scene as a three-part structure. Lorenz reads the scene as a bar form, comprised of two Stollen followed by one Abgesang, usually represented as AAB (152/4–159/1/1; 159/1/2–164/4/1; 164/4/2–172/4); see Lorenz 1924, 179–84. For detailed discussion on his reading, refer to Appendix 1. Thomas Grey interprets the scene as an ABB’ form (152/4–159/1/1; 159/1/2–164; 165/1/1–172/4), referring to dramatic and leitmotivic configuration (1995, 228–41). Matthew Bribitzer-Stull also considers the scene an AAB structure based on leitmotivic content and arrangement (152/4–153/3; 153/4–155/2/2; 155/2/3–172/4) (Bribitzer-Stull 2016, 87–91). As part of his larger project to analyze all of Wagner’s music dramas according to the Italian conventional form (la solita forma), Berger analyzes the scene in reference to the Italian conventional duet form, albeit loosely: cantabile (153/3/5–159/2/1), tempo di mezzo (159/2/2–164), and cabaletta (165/1/1–172/4) with a final stretto (168/4/2–171/1/2) and orchestral postlude (171/1/3–172/4) (Berger 2016, 103–13). Additionally, Bailey divides the scene into seven parts plus interlude, according to the recurrence of the

Return to text

4. In this article, the word “dynamic” is used in the context of kinetics, as opposed to indicating sound volume.

Return to text

5. An advantage of doing so is that it adheres to Wagner’s compositional aesthetic, which is known as treating music and text as equal and codependent.

Return to text

6. Wagner’s first known use of the phrase “art of transition” appears in a letter to Mathilde Wesendonck. He considers the Act 2 love duet from Tristan und Isolde exemplary of the concept: “My greatest masterpiece in this art of subtlest and most gradual transition is assuredly the big scene in the second act of Tristan und Isolde. The commencement of this scene offers the most overbrimming life in its most passionate emotions, its close the devoutest, most consecrate desire of death. Those are the piers: now see, child, how I’ve spanned them, how it all leads over from the one abutment to the other! And that’s the whole secret of my musical form, as to which I make bold to assert that it has never been so much as dreamt before in such clear and extended coherence and such encompassing of every detail” (Wagner 1905, 185). Wagner’s “art of transition” is synonymous with his use of the term “modulation,” which, rather than referring to key changes, denotes flexibility of harmony, rhythm, and leitmotif (and its semantic meaning), etc. On modulation in the context of “poetic-musical period,” see Stephen McClatchie 1998, 90–94. Carolyn Abbate makes the (radical) argument that “Wagner’s motifs have no referential meaning,” providing examples of textual-motivic disjunction (1989, 33–58). My interpretation of the Question motive and the form of the Annunciation of Death scene are grounded on Wagner’s aesthetics of art of transition, as I do not consider the motive and form as fixed and unchangeable.

Return to text

7. It should be clarified that Siegmund’s victory as the resolution of his conflict with Brünnhilde is applicable only within the context of Act 2, Scene 4. Although Siegmund succeeds in persuading Brünnhilde to help him, she ultimately fails to save him from Wotan’s will in Scene 5. Siegmund’s temporary victory is merely one small event in the larger, interlaced narrative structure of the whole Ring cycle. For this full-scale narrative structure, see Harper-Scott 2009, 211–34.

Return to text

8. The gradual change in the power dynamic—from Brünnhilde’s primacy as an avatar of Wotan’s will in deference to Fricka’s enforcement of the marriage contract, to Siegmund’s victory through his love and passion—reflects Wagner’s attitude toward social contracts and laws. Marc Weiner notes the advocation of free love in Wagner’s music dramas: “institutional, contractual unions are inferior, while ‘free love’ is emancipating by being insurrectionary: it is an emotion of revolution, and therefore, it is only consistent that the union of the Wälsung siblings Siegmund and Sieglinde produces the amoral and revolutionary Siegfried.” Notably, only natural union through free love can bear issue in Wagner’s music dramas; in Die Walküre, the conception of Siegfried results from Siegmund’s rescue of Sieglinde from her loveless marriage (Weiner 2014, 706–31). The journey towards free love can be projected onto the Annunciation of Death’s musical and textual organization. In Stage 1, Brünnhilde’s role as a messenger is realized with regular cadential demarcation and rhythmic pace; that is, according to formula and convention. This stability is shaken in Stage 2 as Siegmund’s emphatic passion begins to stir Brünnhilde’s emotional response. Stage 3 reaches maximum rhythmic and motivic freedom, a musical triumph of free passion over received institutional order.

Return to text

9. According to Hepokoski, “a rotational structure is more of a process than an architectural formula [. . .] The referential statement may either cadence or recycle back through a transition to a second broad rotation. Second and any subsequent rotations normally rework all or most of the referential statement’s material, which is now elastically treated. Portions may be omitted, merely alluded to, compressed, or contrarily, expanded or even ‘stopped’ and reworked ‘developmentally’. New material may also be added or generated. Each subsequent rotation may be heard as an intensified, meditative reflection on the material of the referential statement” (1993, 25). Sarah Moynihan, discussing rotational form in Sibelius’s symphonies, further proposes the concept of “rotational projection” in her 2018 dissertation.

Return to text

10. The following references examine rotational form applied to various genres, including sonata, symphony, tone poem, opera, and so on: Hepokoski 1996 (121–46), 2004 (243–66), 2010a (1–17) and 2010b (78–104); Darcy 2001 (49–74); Harper-Scott 2005 (230–53); Hepokoski and Darcy 2006; Davis and Pollack 2007 (373–414); Monahan 2007 (53–95), 2011 (37–58), and 2014 (13–51).

Return to text

11. A number of articles, including several by Warren Darcy, deal with rotational form in Wagner. Darcy 1990 uses “cyclic structure” as a synonym for rotational form, in which dramatic content plays a determinant role; he also employs the leitmotifs and the hexatonic cycle of transformational theory as rotational criteria (2005, 215–41). Graham Hunt treats the leitmotifs and their transformational process as primary criteria for the analysis of Götterdämmerung, Act 1, Scene 3 (2007, 192–96).

Return to text

12. Rotational operations do not necessarily require teleological processing or end-accented directionality, and can be analyzed without reference to telos, as seen in musical analyses from Hepokoski and Darcy’s book (2006) and Monahan’s two articles on Mahler (2007 and 2011).

Return to text

13. What I call the Question motive has also been referred to as “Sterbegesang” (Hans von Wolzogen, Lorenz, and Tarasti), “The Annunciation of Death” (Deryck Cooke, Warren Darcy, and Bribitzer-Stull), “Relinquishment” (Robert Donington), “Question” (Grey), and “Death Lamentation” (Berger, translation of “Todesklage”). Tarasti, Grey, and Berger all point to the motive’s interrogative nature. Tarasti notes that the motive is “rather like a question thrown into the air, for which one awaits an answer” (Tarasti, 201). Grey labels the motive “Question.” Berger suggests “Questioning Fate” or something similar to reflect the organizational principle of the question-answer dialog. These points are the basis of my decision to use the designation “Question motive” in this article. For more on the various names of the motive, see Wolzogen 1895 (53–55), Lorenz 1924 (179–84), Robert Donington 1974 (303), Cooke 1979 (225–35), Grey 1995 (233–38), Bribitzer-Stull 2001 (372) and 2016 (88), Tarasti 2012 (201–2), and Berger 2016 (104–105).

Return to text

14. Anthony Newcomb discusses motive as a form-defining element in Wagner’s music drama in the absence of traditional harmonic and tonal ingredients: “Traditional functional tonality does not operate over large stretches of Wagnerian music drama. Many large stretches of Wagnerian music drama are not functionally tonal [. . .] The primary element in defining the formal return and rounding-off is not tonality, but rather some other element or group of elements, such as motive, instrumentation, tempo, and dramatic situation” (1981, 47). The leitmotif-based approach and resulting three-part form used in my reading recalls Lorenz’s methodological prototype. However, my reading emphasizes motivic flexibility, approaching leitmotifs according to their transformation and adaptability. Lorenz assesses motivic enumerations without considering their developmental progress.

Return to text

15. Bailey notes the double and quadruple diminution of the original Question motive in his analysis: the motive transforms from its initial four measures in Section 1 to two in Section 5, then to one in Section 7 (1977, 57–58). Bailey’s take is distinguished by the weight he puts on the Question motive and its key as the form-defining element. The Question motive most clearly exemplifies the concept of Klang mediation, which Hepokoski regards as a primary expressive and structural element in content-based forms, ever-deepening rotations, and teleological genesis. As the scene progresses, the Question motive undergoes multiple transformations, each time rendering a distinct Klang effect. The motive is first played by brass ensemble, topically signifying an elegy or funeral march, but this Klang gradually evaporates in the transformational process. By the end of the scene, the motive has become an exciting, soaring gesture mainly played by strings. For more on the discussion of Klang mediation, see Hepokoski 1993, 27–29.

Return to text

16. Darcy gives the variants of the Question motive different leitmotivic names. He calls the motive’s rhythmic diminution by half at 165/1/1 “Brünnhilde’s Growing Compassion,” although it is sung by Siegmund; he names the motive’s final transformation at 168/4/3 “Brünnhilde’s Exultation.” This indicates that the Question motive is not fixedly attached to Siegmund, but flexible according to the dramatic progression. For Darcy’s nomenclature of these leitmotifs, see Bribitzer-Stull 2001, 373.

Return to text

17. Cooke traces historical precedents for the Fate motive’s melodic pattern and its questioning gesture, as one of “the cadential clichés in German operatic recitative, when a character asked a question” (1979, 227–28). He finds examples in Mozart, Spohr, Weber, Marschner, and Wagner. Cooke also briefly mentions how the motive’s melodic pattern resembles the ‘Must it be?’ (Muss es sein?) motto in the Grave opening of Beethoven’s String Quartet in F major, Op. 135, final movement. Berger notices that the interrogative motto is immediately answered in the following Allegro with ‘It must be!’ (Es muss sein!) (Berger 2016, 106). This question and answer pattern could be extended to an interpretation of the Question motive in Die Walküre, “Must Siegmund die?” followed by the fatal answer, “He must die.”

Return to text

18. Darcy argues that the Freia motive’s x portion “will later express the sensual aspect of love,” and the y portion “the compassionate aspect of love.” He also points out that the motive has nothing to do with Flight. See Bribitzer-Stull 2001, 342.

Return to text

19. The return of the Fate motive at 153/4/1 should not be mistaken for the beginning of the main section, as the rotational criterion is not the Fate motive but the Question motive initiated by Siegmund.

Return to text

20. This musical repetition is motivated by the text: Wotan and Walvater are the same character, but Siegmund does not know that. In this sense, his questions in Rotations 3 and 4 share textual content.

Return to text

21. Lorenz considers Brünnhilde’s 12-measure answer the highpoint of the first Stollen in the bar form, although he does not provide specific reasons for this reading (1924, 181). The answering music is the most elaborate and sensual rendition of the Valhalla motive in Stage 1. Apart from this aural effect, it is a peak from the dramatic standpoint as well, being the culmination of Brünnhilde’s presentation.

Return to text

22. English translations of the libretto in this article refer to Stewart Spencer’s translations in Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung: A Companion, eds. Stewart Spencer and Barry Millington (2000).

Return to text

23. In the Fricka scene in Act 2, Scene 1, first half, Fricka insists on killing Siegmund and separating the Wälsung couple in retaliation for their offense against the marital vow between Sieglinde and Hunding. Although Wotan’s aim was to unite the Wälsung children happily in the mortal world, he ultimately gives in to Fricka. During this scene,

Return to text

24. The starting point of Stage 2 (159/1/2) coincides with that of the second Stollen in Lorenz’s bar form (1924, 181) and that of the middle section in Grey’s ABB structure (1995, 238). The narrative supports Lorenz and Grey’s demarcation, as Siegmund’s statement of refusal decisively initiates the confrontation between the two characters.

Return to text

25. Darcy calls the turning figure that accompanies the Fate motive the “Death motive.” For this leitmotivic nomenclature, see Bribitzer-Stull 2001, 372. The present article, however, does not view the figure as a new, independent leitmotif but as part of the embellished accompaniment figure for the motive.

Return to text

26. Another significant motivic change from Stage 1 is that the beginning of the Fate motive is reharmonized, from a minor triad to a French sixth chord (F, A, B,

Return to text

27. Siegmund’s melody ascends chromatically, creating a sequential progression (161/2/2–161/3/1; each statement consists of an ascending sixth and descending fifth). This sequence strives towards a PAC in A major, but another premature Fate motive in the orchestra thwarts it. It seems to successfully land on a PAC in B major, but the B major turns out to be the beginning of Brünnhilde’s chromatically ascending gesture (

Return to text

28. Brünnhilde’s text is: “You’re so little heedful of bliss everlasting? Is she all to you, this pitiful woman who, tired and sorrowful, lies there, faint, in your lap? Is there nothing else you hold dear? (So wenig achtest du ewige Wonne? Alles wär’ dir das arme Weib, das müd’ und harmvoll matt auf dem Schooße dir hängt? Nichts sonst hieltest du hehr?)”

Return to text

29. In 164/3/1–164/3/2, Brünnhilde’s vocal line descends stepwise and in unison with the orchestra’s uppermost melody from B4 to E4, and then rebounds to G4. In 164/3/3–164/3/4, it descends further to

Return to text

30. The quarter-dotted eighth-sixteenth rhythm of Variant 1 recurs in Variant 2; the stepwise melodic ascent from the second to fourth note (

Return to text

31. Siegmund’s cadential attempt in E minor is another remarkable departure from Rotation 6, where his statements of the Question motive in

Return to text

32. Lorenz calls the four-measure trill passages “Loge’s sixths with trills” (Logesexten mit Triller) (Lorenz 1924, 183). I consider the trills to be a highly unstable gesture developed from the Freia motive’s triplet figure, and not an independent motive.

Return to text

33. The first statement of Variant 4 at 168/4/3 is the same as Lorenz’s Variant 2 of the Death-Song (Sterbegesang) motive and Darcy’s “Brünnhilde’s Exultation.” Each following subrotation opens with slightly altered versions of Variant 4.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2022 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Lauren Irschick, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4399