Sociable Musicopoetics in Vijay Iyer and Mike Ladd’s In What Language*

Vilde Aaslid

KEYWORDS: interactivity, improvisation, Vijay Iyer, Mike Ladd, poetry, jazz, musicopoetics

ABSTRACT: Through an extended analysis of an excerpt from Vijay Iyer and Mike Ladd’s In What Language, this essay engages with the ongoing deepening of the theory of improvised interactivity. Few studies within music research have considered the rich body of works combining music and poetry in improvising contexts. This article advocates for listening to Iyer and Ladd’s co-created work through the lens of sociable musicopoetics, an analytical stance that hears the interactivity in their creative processes. Through analysis and interviews, this article suggests that the sociable musicopoetics framework helps work against the restrictive binaries of music/language and composition/improvisation and enriches the understanding of improvised music and poetry combinations by highlighting the meaningfulness of interaction itself.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.28.3.1

Copyright © 2022 Society for Music Theory

Any project is a dialectic between you and not you. That’s sort of what it amounts to. I think I learned the most from non-musicians. I certainly learned a lot from musicians and I’ll continue to. But, working with film makers, choreographers, poets . . . you get to hear from the outside.

— Vijay Iyer(1)

[1.1] While interactivity has long been a prominent framework for thinking about the sociability of jazz improvisation, “the concept of interaction in jazz nevertheless remains somewhat undertheorized,” as Benjamin Givan has noted (2016, [1]). In the last several years, new analyses such as Tilley 2020, Steinbeck 2016, Michaelsen 2019, and Givan 2016 have begun addressing this shortfall. The bulk of this scholarship has focused on interactivity between musical improvisers or between musicians and dancers.(2) Relatively few analyses, however, have considered improvised interactivity and musicopoetics, the relationship between music and poetry.(3) Through a case study analysis of an excerpt from In What Language, created by Vijay Iyer and Mike Ladd, I demonstrate the value of listening for interactivity in musicopoetics, both to enhance the understanding of the immediate case and to deepen the theorization of the two discourses of musical interactivity and the relationships between music and poetry.

[1.2] Throughout his career, Vijay Iyer has steadily collaborated with artists from other disciplines, among them poetry, film, and dance.(4) He has described these collaborations as fundamental to his artistic practice, as the projects in which he learns the most (Iyer and Aaslid 2021, 96). A recurrent figure in his intermedial work is poet Mike Ladd. Over a ten-year period, the two artists have collaborated on a series of projects that combine Iyer’s intricate, moving music with Ladd’s rich verse. During their decade of collaboration, they have developed a deeply intertwined process, and the works that have emerged from this practice show a nuanced and multi-faceted relationship.

[1.3] Approaching this material with interactivity as a guiding paradigm effaces two troublesome binaries that have long plagued the analysis of texted and improvised musics. First among these is the divide between music and language, often understood as “(inarticulate) music/(articulate) writing,” as Brent Hayes Edwards (1998, 580) frames it. Analyses that listen primarily for the musicality of the music and the linguistic qualities of the language constrain the expressive possibilities of each medium. This shortcoming has particular significance for the study of art connected with or influenced by Black expressive cultural practices, many of which move through music and language on a generative continuum rather than as discrete modalities. The analysis that follows listens for interactivity between artists in process rather than between “music” and “text.” The second binary, with perhaps an even more extensive discourse than the first, is the distinction between composition and improvisation. Distinguishing between these types of creative processes is of little import for this analysis, as doing so draws firm boundaries where, in practice, there is fluid movement. Instead, I attend to traces of sociability from across the whole of Iyer and Ladd’s creative activity.

[1.4] In his introduction to a volume on Walt Whitman and modernity, Daniel Albright writes, “To study one artistic medium in isolation from others is to study an inadequacy” (2018, ix). His stance here is not that a single medium alone is lacking, but rather that it is almost never alone. Through analysis and interviews, this essay demonstrates that the study of musical interaction is enhanced by the inclusion of intermedial examples, when music is quite literally not alone.(5) Through poetry, we can “hear from the outside,” attending to the dialectic of improvised musical relationships from a new perspective.

History of the partnership

[2.1] In 2000, when his collaboration with Mike Ladd began, Iyer had recently moved to New York.(6) While studying music cognition in the 90s at the University of California, Berkeley, Iyer developed his artistic approach amongst the Bay Area Improvisers, a collection of musicians with a wide stylistic range and influences from electronic music, experimental music, and creative music or jazz. Widespread recognition came shortly after his move to New York, and the early 2010s brought a flurry of awards and critical recognition, including the Greenfield prize (2012), the Doris Duke Performing Artist Award (2012), and the MacArthur fellowship (2013); he topped the Downbeat Jazz Critics Poll in multiple categories in multiple years. He has collaborated with many artists, among them Das Racist, DJ Spooky, Burnt Sugar, and Butch Morris; among the ensembles who have commissioned his work are Bang on a Can, the Silk Road Ensemble, and the International Contemporary Ensemble.

[2.2] Mike Ladd’s work is also defined by an experimentalist core, which is informed by his academic background.(7) He grew up in an academic household and went on to earn a graduate degree in poetry from Boston University, studying with Robert Pinsky and David Ferry. During these studies, he further honed his interest in poetic form and metered verse, extending this focus into his hip-hop practice: “I began to understand hip-hop as a specific form and explore the use of form and lyric in the music I was making” (2013). His underground hip-hop albums layer influences from a wide range of musical styles—funk, punk, dub, experimental jazz, and bhangra, to name a few—with Ladd’s high concept lyrics. He is now based in Paris, where he teaches and performs. With a fluency in both academic and hip-hop cultures (and in the places where they meet), Ladd melds their distinct jargons in his fast-paced conversational tone.

[2.3] Iyer and Ladd first met during a period of time in which they were attending the same shows; later, Iyer saw Ladd perform.

I saw him sitting in with this group. . . called Antipop Consortium. They’re hip hop, I guess, you know. . . And then Mike was there with them on stage, in the corner with some very weird analogue synthesizer from the 1970s. . . smoking a cigarette and making all these really weird sounds with echoes and noise and chaos out there (laughs) (2012).

As the two came to know each other better, Iyer was intrigued by Ladd’s artistic approach to lyric construction, which he would later describe as “literary.” He continued: “It just seemed to have all these pointers to other things that you don’t usually hear in performed hip hop lyrics. . . It seemed grounded in literary traditions. He seemed to have a working knowledge of the craft and history of poetry, both oral and written, from many times and places” (2012). Iyer appreciated the “global sensibility” of Ladd’s politicized subject matter. Last, he admired Ladd’s approach to combining his text with music: “Its relationship to the music was more ambiguous, in just an interesting way. . . it just seemed to cut diagonally across the music. (laughs) Like it wasn’t squared off in meter, I mean sometimes it was, but a lot of the time it was just sort of penetrating the space of music in a more. . . in a richer way, I felt” (2012). Ladd was decidedly pithier in his description of the history of their relationship: “We click, we’re friends. We clicked when we met years ago before we even started playing together” (2012).

[2.4] When I spoke with Ladd about his and Iyer’s approach to the projects, he told me, “This combination of words and music is something that we’re both very accustomed to already.” He continued, adding,

I’d already been in punk-rock bands, hip hop bands. . . and then I was entering into the poetry scene in ’93 which in New York was very intentionally referencing the Black Arts movement of the late 60s and 70s. And the Nuyorican arts movement. . . That already was an immediate marriage of text and music” (2012).

Ladd’s approach, which avoids the “squared off” or stilted deliveries that sometimes happen when spoken language and music are combined, builds on performance practices of poets like Amiri Baraka and Jayne Cortez. Iyer played with Baraka’s band from 2000 through 2004 and cited that experience as having primed him for his work with Ladd. “I remember Mike came and saw me play with him a few times, too. That was really helpful for our process. But Mike’s been a lifelong admirer of Amiri Baraka, so it wasn’t like any of that was news to him exactly, it just galvanized us, I think” (2012).

The Series

[3.1] Through over a decade of collaborative work, Iyer and Ladd have produced three concert-length works.(8) All three projects engage actively with politics, and in each case Ladd gathered material from fieldwork and interviews. The first piece, In What Language, explores globalization through the experiences of people of color in the ecosystems of international airports. Still Life with Commentator darkly satirizes the 24-hour American news cycle. For the final work, Holding it Down: The Veterans’ Dreams Project, Ladd interviewed veterans of color about their dreams and wove their stories into the work’s haunting landscape of self-medication, surrealistic humor, and PTSD. This final work is distinct from the others in that some of the interviewees became participants in the collaborations, contributing poems and performances to the piece. Whereas both Iyer and Ladd had personal experiences related to In What Language, and Still Life with Commentator dealt with the public sphere of the media, Holding it Down dealt with a topic with which neither Ladd nor Iyer had personal experience. Their collaboration with veterans was both deep and sustained, through the project and beyond. “We wanted to enact a gesture of listening between veterans and civilians, build something together, and create community through that process” (Iyer 2020, 82). Each of the large works was the result of a commission by an art institution in New York City, and each was realized in the form of both a live multi-media performance and a recording.(9)

[3.2] Critical reception of these projects makes clear that they defy easy genre categorization. A review of the album version of their third piece called the trilogy “a series of unclassifiable blends of music, theater and spoken word that paint a vivid oral history of post-9/11 America” (Barton 2013). Another characterized the live performance of the second collaboration as “a blizzard of word, sound, image and movement” and described the results as “not just galling, but gripping” (2006). A third, by Siddhartha Mitter, called the first collaboration “a triumph of a genre that doesn’t yet exist. . . It is aggressively ambitious yet unfailingly accessible and deeply empathetic” (2005). While generally celebratory, these descriptions reflect the way that thwarted genre categorization has been central to the pieces’ reception.

[3.3] The three works share the same basic structure: a series of short pieces, generally between two and eight minutes, organized into a larger whole. Vocal and musical characteristics shift, sometimes dramatically, between the small pieces. The individual texts do not progress through a larger narrative, but rather offer a variety of insights that coalesce into overarching themes. In general, the works take a fluid approach to the speech/song spectrum. In What Language contains all spoken text, but a fair amount of Holding It Down is sung. In both live performance and recording, the sung material is often processed electronically. The spoken texts range in delivery as well, from prosaic personal narrative to slow-paced academic poetry reading, to high-energy MCing. Iyer approaches his collaborator’s texts with an expansive style range, blending acoustic and electronic methods in all three works.

Sociable musicopoetics

[4.1] In the course of developing their projects, Iyer and Ladd maintained a singular focus on telling the stories they had collected.

It really wasn’t about us as players. . . I mean, there’s a lot of playing in it. People take solos and there’s a lot of improvisation. But. . . I had to kind of keep it in check in a way. I remember having to tell the horn players: this isn’t about you grandstanding. (laughs) It has to be about, think about the story we’re telling here. Basically, they had to deprioritize their own musical fixations and think more about the energy of the stories that were being told and also just the energy of the moment we were in. And what this project was meant to represent (2012).

Iyer and Ladd’s commitment to representing the stories of their interlocutors shaped, in part, the relationship between their artistic contributions. Iyer has given considerable thought to the narrative potential of music, especially improvised music (2004). He proposes that musical narratives are not just told via structural parameters, but that they emerge from the “minute laborious acts that make up musical activity” performed by individual musicians in embodied dialogue (2004). These, in turn, generate a rich field of meaning different from the linear form often implied by the story-telling model. When envisioning the role of his music in the trilogy, Iyer sought to create a generative relationship between the musical and poetic narratives:

The poetry could coexist with the music and penetrate it. . . the music was a frame for these characters, like an environment for these characters to tell their stories. But then at crucial moments in the narrative the music would shift. . . it would seem to be this kind of static environment, but then suddenly it would turn or, you know, the color of it would change or the intensity or the rhythm. And internal rhythmic stuff would change, or something about it would develop as the story develops (2012).

[4.2] To foster this relationship between Ladd’s verse and Iyer’s music, they used a creative process that Ladd characterizes as “embarrassingly simple. You know, I write something. He checks it out. He then comes back with a couple of rough sketches, tracks that are usually computer generated. . . I give him more, then he gives me more, I give him more, he gives me more” (2012). Iyer’s music making encompasses the full range of determinacy, from completely open to entirely fixed. In his work with Ladd, he came to the workshopping sessions with some structural ideas in place: “what I didn’t want to do was start by jamming. . . it’s not that I don’t trust improvisation, but I like, as a composer, to have an idea in place. And then you can improvise with the idea” (2012).

[4.3] From these preliminary ideas, improvisation shaped the development of the projects. As Iyer described it to me:

Basically the ways in which these different energies manifest with the same structure is because of improvisation. Through improvisation we sort of settled on dynamic and textures and the way people would enter and leave the musical space. . . I guess I would say that a lot of it was arrived at through improvisational process, in terms of just building that stuff (2012).

Thus, improvisation affects aspects of the works that may appear to be strictly composed. Decisions made collaboratively and often improvisatorily become fixed components of the pieces. This workshopping approach, which has a long history in jazz practice, extends the interactivity of improvisation into a collaborative compositional process, here between Ladd and Iyer.(10) Although, in a sense, improvisation occurs throughout the timeline of the project, the improvisation is not the point: the dialogic nature of the process is. “Let’s start with the same premise, with the same set of elements, and see if the same thing happens, you know? It could be described as a process of stripping away improvisation through coordinated collective action” (2020, 89).

[4.4] It is through their collaboration, a human relationship, that the interaction between music and word is constituted. Neither text nor music takes precedence in this process, according to Iyer. “We had to find that relationship. And that meant adjusting on all sides. And sometimes I’d write something and it’d just be wrong. . . And other times Mike was compelled after hearing the stuff to rewrite the poems” (2012). Sometimes segments of music originally written for one poem or story would work better with another, and vice versa. Either person could initiate the compositional process for a particular story, meaning that “it was a very organic process” (2012). Each took direction from the other as well as from the stories being told. Both Ladd and Iyer repeatedly emphasized that the pieces were not about the music or the poetry, but about the stories shared with Ladd in his interviews. When they had something that resembled a relatively complete work, they brought the piece to the full ensemble. After hearing the work with live instruments and improvising musicians, they resumed their revisions. Ladd characterized this final stage as when the work began “to take a lot of shape musically” (2012). In short, their process is fundamentally collaborative, fluid, and responsive to the material and performers with which they work.

[4.5] In striving to engage analytically with Iyer and Ladd’s work, my approach draws on recent thinking on improvisation and interaction. Sociable interactivity in improvisation has been a central site of inquiry in jazz studies since the mid-1990s, influenced by Ingrid Monson’s Saying Something, among others.(11) Recent work on the topic has broadened and enriched the conversation on two fronts. The first centers around convergence, a process through which improvisers’ material interactively becomes more similar over time, which has sometimes been assigned a default positive value. Garret Michaelsen has pushed back on this assumption in his analysis of the Miles Davis Quintet’s The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965. There, he argues, the band uses divergent interactional strategies “with the goal of subverting each other’s typical expectations as much as possible” (2019, 2). The second front is concerned with the analysis of interactivity, which has long suffered for lack of specificity. Benjamin Givan has argued that it is not enough to simply indicate the existence of interactivity (2016). Instead, he and others (Steinbeck 2016; Michaelsen 2019) have worked to deepen music theory’s consideration of the multivalence of interactivity. My analysis that follows explicitly engages with and aligns with both of these developments.

[4.6] The uncritically celebratory view of improvised interactivity not only flattens a complex subject but also has political implications. Fumi Okiji points to the stark contrast between the historiography of improvisation as individual liberation and the realities of constraints on Black subjectivity: “If jazz presents itself as an embodiment of the individual in an age in which that mode of subjectivity has become impossible to maintain, then it must be propaganda in the service of society's repressive forces” (2018, 20). Iyer himself has written from a related perspective, examining critical improvisation studies’ “almost entrepreneurial investment in the term ‘improvisation’” (2019, 4). Whereas leading texts in that subdiscipline see community as a foundationally positive facet of improvisation-based practices, Iyer reminds us that communities also contain violence and terror.(12) “If we understand that humans can also improvise murderous alliances, we might think twice about this banal category, with its implications for race, nation, and kinship, and its use as a premise for war, hyperpolicing, and other blood rites” (Iyer 2019, 7). Considering agency within musical practices, Iyer turns to the work of Black feminist theorists like Hortense Spillers, Sylvia Wynter, Audre Lorde, Saidiya Hartman, and Christina Sharpe to support the assertion that agency is relational: “the self must be understood in terms of its position in the realm of the social, which is to say, in a network of power relations with other subjects. There is not one subjectivity, but many. There is no transcendent subjectivity; there is only intersubjectivity” (2019, 12). And so he comes to a description of improvisation as “movement in relation” (2019, 13), a kind of intersubjectivity that situates interactive encounters in their broader systemic contexts.

[4.7] In the following analysis, I aim to describe this “movement in relation” between Iyer and Ladd, music and word. I focus on a brief two-and-a-half minute long excerpt: the opening piano and voice section of the first track of In What Language.(13) As an outsider listening in, I attend to the resonance of a collaborative process and the possibility of intermedial interactivity; hearing the sociability of the musicopoetics is the primary aim and interpretive moves are secondary.(14)

[4.8] The main principle of what I am calling sociable musicopoetics is that listening to the combination of music and text from improvising contexts is enriched when guided by the principles of interactivity. The approach is fundamentally oriented towards the analyst’s process: the listening.(15) In spoken language, we attend to monologues differently than we do conversations. Jazz studies has long argued that listening to improvised music is most rewarding when attuned to the always-present possibility of interactivity. Sociable musicopoetics extends that stance into the realm of text and music relationships, asserting that the musicopoetics of pieces like Iyer and Ladd’s are best served by an analytical stance that listens for the push and pull of a dialogic exchange between musician and poet, between music and word. By “music and word,” I mean not just this music and these words, but also between the conceptual categories of musical sound and language. Similar to the productive tension discussed above, here I listen for how Iyer and Ladd move in relation within and against the constraints of musical and poetic systems.

[4.9] Crucially, listening for the resonance of interactivity is not the same as listening for interactions; sociable musicopoetics does not stake a claim of intentionality. Like much scholarship on jazz interactivity, my analysis does not seek to identify specific moments of interaction between Ladd and Iyer that they would necessarily also identify as such. Much of what I hear could well be coincidental or an artifact of my particular listening. My discussion of Iyer and Ladd’s creative processes is meant to lay the groundwork for what kind of interactivity their processes afford, not to serve as evidence of a particular interaction.

[4.10] Sociable musicopoetics as an analytical stance shapes the analysis that follows, even when it may resemble a conventional analysis of music and text relationships. Such hermeneutics, again, are not the goal of the analysis but a side effect of listening for dialogic exchange. The larger point is that, throughout the process of analysis, sociable musicopoetics works (at times subterraneously) as a foundational guide. In the realm of text/music relationships, this guidance is especially needed; although the music studies literature on text and music interrelation is rich and varied, little of it explores the multi-agential context of interactive improvisation. Word and music studies, unlike literary studies, has tended to avoid close examination of the improvised intersection of music and word.(16) Invoking “sociable musicopoetics” preemptively opens text/music relationships to the possibility of improvised interactivity. Listening in on Iyer and Ladd’s interaction in one select project segment makes clear that the improvised intersection of music and word has much to offer, not only in providing a multitude of sites for analysis but also as prompts for further theorization of interactivity in music.

In What Language – Genesis and Cycle

[5.1] In What Language is made up of seventeen tracks of music with spoken word that explore globalization through the experiences of people of color in international airports. When Vijay Iyer received his commission from the Asia Society, he carefully considered what kind of piece he would like to write and how to relate to his sponsoring institution. In some ways, the Asia Society is an unlikely patron for the politically progressive Iyer. As he relayed to me:

[It] is this New York Institution on Park Avenue that was basically founded to uphold orientalism on some level, so I thought. . . that my response to it would be, just to completely disrupt that narrative, and offer a different one that had to do with a different notion of community that wasn’t even specific ethnicity. But more specific to a particular moment in history and a common predicament which had to do with being brown at the turn of the millennium in the West, or in these global centers (2012).

[5.2] The phrase “In What Language” comes from Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi; Iyer considers his story the “crystallization” of the project. In early 2001, airport authorities in New York’s JFK airport detained Panahi when he was en route from Hong Kong to Buenos Aires. When he refused to be fingerprinted and photographed—he was, after all, just passing through the airport, at no point attempting to enter the United States—they detained him overnight and eventually sent him back to Hong Kong. He remained handcuffed on the entire return flight. Iyer relates more of the story: “And he says, I wanted to tell the people next to me I’m not a criminal. I’m just a man. I’m an Iranian man. But how can I say this? He says, in what language? Anyway, that became this resonant phrase. In what language can you assert your humanity in the face of ignorance and oppression?” (2012). While clearly resembling the intense cultural scrutiny on airports following the attacks on September 11, 2001, Panahi’s experience predates that event. Reflecting on Panahi’s experience eventually led to Iyer and Ladd focusing on a project to tell the stories of people of color in international airports. Ladd conducted fieldwork while preparing his poetry, interviewing people from all strata of the airport ecosystem, from janitors to business travelers.

[5.3] The piece is unquestionably political, from its broad topic to the details of its content, as is typical of the Iyer/Ladd collaborations. Both artists contextualized these politics as related to their lived experience of race. As Ladd says,

This work is political as much as everything I am ever going to do is political even if it is just an album of whistling. This is just my understanding of politics. I am continuously asked whether I consider myself a political artist, and in fact I don't think of it in those terms. I consider myself someone who is always expressing my life in its entirety. . . This is a very old point, but if you have any shade that is not white it is difficult to extract politics from what you are doing” (Iyer and Ladd 2003).

Iyer frames it in much the same way:

I have always seen my work as politicized in a certain way. It is also very much about my life experiences transduced into this other medium. Not only are they representing my life experiences, they are literally my life experiences: the act of making music is my life experience. Within that is my perspective as a person of color in this country and that is utterly fundamental to everything I do and to every human interaction that I have in this culture” (Iyer and Ladd 2003).

The sociability of Ladd and Iyer’s musicopoetics is embedded in their racialized lives, and attending to their interactions is also listening for the politics of these acts.

“The Color of My Circumference I”

[6.1] Compared with the rest of In What Language, the opening of “The Color of My Circumference I” is relatively simple, involving only acoustic piano and spoken text. As such, it can be viewed as a distillation of the interactivity of In What Language, allowing for a close examination of the conversational dynamics between Iyer and Ladd. Moving through the different layers of the work, this analysis begins with an introduction to Ladd and Iyer’s individual contributions before shifting attention to their combination.

[6.2] Ladd gleaned most of the narrative material of In What Language from his interviews. The piece relays his reimaginings of his interlocutors’ stories. Also included within the work, however, are four reflections by Ladd about his own experiences traveling as a person of color. These examples, each a numbered “Color of My Circumference,” form a sub-cycle within the work. They are related poetically, of course, but also musically.

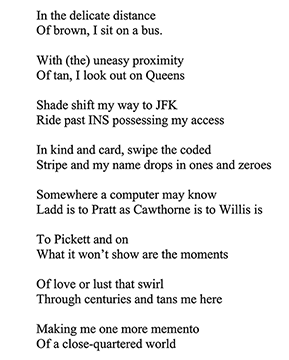

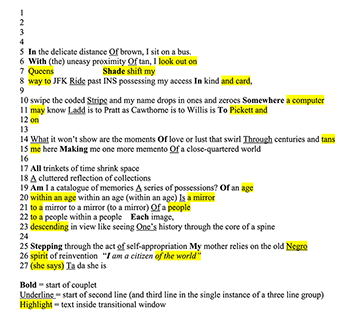

Example 1. Full text of “The Color of My Circumference I,” as printed in the liner notes for In What Language

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[6.3] Formally, the poetry of “Color of My Circumference I” (presented in full as Example 1) is straightforward: fourteen couplets with a single group of three lines appearing after the tenth couplet. The majority of the lines have between seven and ten syllables, with a few outliers up to thirteen and down to four. There is no set rhyme scheme and no meter. Within the form, Ladd plays with rhythm, stepping in and out of metrical senses. Iambs and anapests dominate, from the opening “In the delicate distance of brown” to the closing “Tada she is.” The central question of the poem is entirely iambic: “Am I a catalogue of memories / a series of possessions?” This iambic lilt veers into a series of anapests, with text that shifts in meaning through prepositional permutations (“Of a people, to a people, within a people”). The third couplet’s line-starting spondees contrast sharply with the iambs and anapests, a departure that lends emphasis to the spondees and pairs them aurally (“Shade shift my way to JFK / Ride past INS possessing my access”).

[6.4] Proliferation of assonance and consonance imparts a melodic quality to the poem. A striking instance of this musicality occurs during the above-mentioned spondees. The broadness of the A sounds in “shade,” “way,” and “K” slow the pace, intensifying the spondee. Ladd follows this broadening with the hissing sound of the consonant S (“Ride past INS possessing my access”). Alliteration is prominent as well, first in the opening line and continuing throughout as in lines 7, 13, and 17. The analysis will later return to explore in greater depth the role these sound devices play; here, however, I want to pause to note Ladd’s literary approach. As he told me, “It’s always been my intent that the poetry can also stand alone. That you can read the text outside of the context of the music, away, outside the context of the performance and get just as much out of it as with the other two components” (Iyer 2012).(17) Ladd’s commitment to the poetry’s potential autonomy here signals, in part, his orientation towards poetry’s formal elements and perhaps a distancing from the “spoken word” moniker. Though the poetry emerged from a collaborative and improvisatory process, it should still meet the expectations of poetry written for the printed page. As Ladd explained in an interview, “All these efforts, through engaging lyric, were strictly poetic. If hip-hop and spoken word were included, it is only in my effort to explore different disciplines within poetry” (Diggs 2013).(18)

[6.5] With its themes of transit, race, global awareness, and the (im)personal, the opening poem of In What Language distills many of the ideas of the larger cycle. It interrogates identity in transit: what is this thing, exactly, that embarks on global journeying? What, from our identity, do we bring with us, and what do we leave behind? The opening image of the bus ushers the reader/listener into the suspended state of the transit-world. The “brown” and “tan” of the opening two couplets are at first ambiguous in their reference, but later in the poem Ladd anchors that “tan” to his body: “What it won’t show are the moments / Of love or lust that swirl / Through centuries and tans me here.” As he leaves New York behind, Ladd takes race with him.

[6.6] Ladd builds his opening poem on the disjunction between personal histories and the depersonalizing force of global mass transit, each of which he metaphorically renders as an archive. In lines nine through eleven, Ladd’s digitized identity (swipe the coded / Stripe and my name drops in ones and zeroes) encounters a one-dimensional archive of names, placing him in relation to other equally disembodied names. The lines evoke the rootless experience of travel, the contradiction of feeling both anonymous and heavily identified. He asserts his body as an archive of the “moments / Of love or lust that swirl / Through centuries” through the poem’s later image of the articulated length of a spine as a record of one’s family narrative (Each image, descending in view like seeing / One’s history through the core of a spine). Through this personal, bodily archive, he answers the central question of the poem, rhetorically, in the affirmative: “Am I a catalogue of memories / A series of possessions?” The final six lines of the poem turn the themes of family, race, and identity onto a self-determinative aphorism. Here, Ladd invokes his mother’s voice, her apparent power attributed to a stance learned from her family’s cultural history. The questions of identity and archive are seemingly dispelled by Ladd’s mother, as she speaks her own identity: “I am a citizen of the world.”

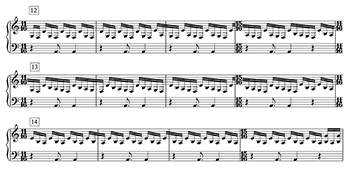

Example 2. Transcription of piano [1:06–1:24]—Emergent pulse against ostinato

(click to enlarge)

[6.7] The surface of Iyer’s music for these first few minutes of In What Language is deceptively simple: the solo piano left hand articulates a single pitch ostinato while the right hand traces out sixteenth-note arpeggios with individual voices that crawl in stepwise motion; see Example 2 for a transcription. Undergirding this spare surface is an elusive rhythm that seems to constantly slip away while propelling the piece forward. The rhythmic makeup of “Color of My Circumference I” gives the piece its unsettled quality while it interacts significantly with the poetry. Before exploring its connection with the poetry, I first describe the two distinct pulses that contribute to this drive—the bass ostinato and the highest pitch of the arpeggios—and the effects created by their continual variation against each other.

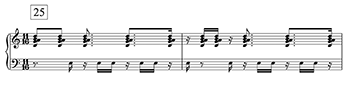

Example 3. CoMC meter

(click to enlarge)

[6.8] Iyer bases all four of the “Color of My Circumference” tracks on an additive meter, illustrated in Example 3 and referred to from this point forward as the CoMC meter. The structure of the meter is audible to varying degrees in the four tracks—perhaps most clearly in “Color of My Circumference II”—with different realizations in each. As Iyer described it to me, the basic metric unit is 48 sixteenth notes, but this larger group divides into three groups of eleven plus a group of fifteen as shown. The groups of eleven subdivide into a four-three-four pattern, and the group of fifteen adds an extra four sixteenths. Whenever Iyer uses the CoMC meter on In What Language, the tempo is roughly the same: quarter note = 112 bpm. At that speed, in the most audible iterations of the meter, the first three measures parse as an uneven triple time, made occasionally uneasy by the extension of the 15/16 group. For this analysis I use “cycle” to refer to each full occurrence of this 48 sixteenth-note group.

[6.9] In “Color of My Circumference I,” the sense of meter is rooted primarily in a gentle bass ostinato, played on A2 for nearly the entire excerpt. As shown in Example 2, a transcription of 1:06–1:24, this ostinato articulates only the second and third groups, leaving the low register empty on each downbeat as well as during the extra group of the 15/16 measure. It is a heartbeat with an occasional skip. In contrast to the more insistent versions of the CoMC meter that appear later, the gentleness of the ostinato here leaves open other possible hearings of the rhythmic structure, including an even 3/4 time with the ostinato phasing across the meter. No matter how one hears it, the ostinato’s persistent presence makes truly stable metrical ground elusive.

[6.10] Over this bass line, Iyer layers his mutable arpeggios. He plays the figures from top to bottom, one pitch at a time, with dynamic emphasis on the top pitch.(19) The repetition of the top note forms another layer of pulse that cuts through the wash of the pedaled arpeggios (see Example 2). In the first two measure of the example, the emphasized D4s pulse every third sixteenth note. But as Iyer adds and subtracts pitches from his arpeggios while continuing his strict top-to-bottom figuration, this emergent pulse changes. In the fifth measure, for example, it is five sixteenths long; in the eighth measure, it reverts to three sixteenths.

[6.11] Constantly in flux, this pulse thwarts the listener’s attempts to hold onto a predictable rhythm. Each of its permutations is maintained just long enough to be recognized before shifting to something new. These shifts are layered above the already restless CoMC meter. Iyer’s rhythmic structure for the piece, then, performs the complex work of imparting the music with the sense of propulsion without predictability. Recalling Iyer’s characterization of his music as the “environment” for Ladd’s poetry, here he offers a churning, unsettled world for those words to inhabit. What better way to initiate a travel-themed work than with a rhythmic frame that drives constantly forward but offers no comfort of rooted meter?

[6.12] The timing of Iyer’s movement between his pitch sets adds to the unsettled effect. Recall that Iyer’s approach to the meter in “The Color of My Circumference I” obscures the downbeat, articulating the second and third divisions of the meter with his low ostinato while avoiding the downbeat and the four-beat extension The eight beats that span the final four of one cycle and the first four of the next form a kind of transitional window, feeling more like suspension than arrival.(20) It is generally during this suspension that Iyer changes his arpeggiated figures, as you can see on the final sixteenths notes of lines 1 and 2 of Example 2. First the arpeggiation changes, and then the metrical extension comes; stability then returns with the first bass articulation of the ostinato on the second group of the next rhythmic cycle. If the arpeggios tumble forward as a river, these transitional windows arise at it turns. River bends are not tidy pivot points; the momentum of the water drives forward even as the banks curve. Here, it sounds as though the arpeggios stretch the metrical fabric as the chords change, with each time the forward drive of the previous chord echoing in the seemingly delayed start of the next rhythmic cycle.

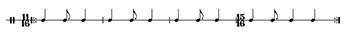

Example 4. Transcription of pitch stacks and poetry, numbered by rhythmic cycles, CoMCI excerpt

(click to enlarge)

[6.13] Example 4 presents a simplified transcription of the first two-and-a-half minutes of “The Color of My Circumference I” that I will refer to often throughout this analysis. I have reduced Iyer’s arpeggiation to pitch stacks and have overlaid the text approximately as it occurs in the recording. The boxed numbers represent the rhythmic cycle, each one being an iteration of the meter shown in Example 3. For example, the passage transcribed in Example 2 appears in Example 4 at cycles 12 through 14. Note that although the cycle numbers appear aligned with the change of pitch stacks, in the recording they are actually offset during the transitional window for all cycles except 19.

[6.14] Having introduced the main structures of the poetry and the musical rhythm, I turn now to discuss their interaction. I note first that improvised and composed parameters structure the performance of the music and text, and their interaction reflects the collaborative environment. Iyer contributes the composed structure of the rhythmic cycle, with the rest, including the pitch material being improvised.(21) As described above, Iyer’s left-hand rhythmic pattern is pre-established. The pitch content, on the other hand, remains undetermined up to the moment of performance in most regards, including the number of pitches in the right-hand arpeggiations—and, hence, the emergent pulse. The text has two composed structures: the couplets of the written poem, and the grammatical units within and across those couplets. Ladd’s improvised delivery distributes these in time, which causes yet another structure to emerge from his pauses and clusters of spoken text. As such, the placement of the poetry against the music is improvised. There are certainly some planned features—beginning with a piano introduction, for example—but the details are improvised. The alignment of the text against the music is particularly rich for sociable musicopoetic analysis, partly because it is a facet of the performance over which neither Ladd nor Iyer have complete control.

[6.15] The first twenty seconds of the track establishes a responsive relationship between Iyer and Ladd’s performances. In the opening solo piano passage, Iyer changes pitch groupings every three seconds, or two stacks per rhythmic cycle. Iyer maintains this three-second pattern for the first twenty-four seconds of the piece. When Ladd enters with his text, Iyer maintains his stacks for a full six seconds, halving the harmonic rhythm. The slowing of the harmonic rhythm encourages the listener to turn their attention to the poetry. Without adjusting volume or texture, the musical content shifts to the background.

[6.16] Iyer’s specific pitch choices further frame Ladd’s entrance. The range is quite narrow, defined within the reach of a relaxed right hand. Iyer changes pitch with stepwise motions, a measured process under the active surface. Discounting the left-hand ostinato on A2, Iyer’s first eight stacks (the entirety of the introductory section) all fit within the span of F3 to E4. At stack 9, Iyer narrows his stack, bringing the bottom up to G3 and, more markedly, the top down to D4. After twenty-four seconds of repetitions of E4, even this tiny degree of contraction in range is striking. With it, Iyer gives an aural bow of his head as a welcome to Ladd’s voice.

Example 5. Distribution of poetry across rhythmic cycles

(click to enlarge)

[6.17] Example 5 offers an overview of how the different structural elements of the poetry and the music intersect in the recording. The numbers on the left represent Iyer’s rhythmic cycles and are the same as the numbers in Example 4; the text following that number is spoken within that cycle. Bold and underlined words mark the start of the first and second lines of a couplet, respectively. The shading, last, serves to indicate passages that fall within the transitional windows.

[6.18] While Ladd and Iyer created these structures during their collaborative compositional process, their interrelation only emerged in improvised interaction. Ladd’s performance necessarily determined the ways in which the poetry’s internal structural elements interrelated, but it also sets them against the cyclical musical meter. During Ladd’s first entry, which occurs just after the start of the fifth cycle, he aligns the poetry with the rhythmic structure. Here he delivers both lines of the first couplet, finishing before the transitional window begins. He pauses for a breath as Iyer’s music takes its curve around the bank. His next entry occurs shortly after the downbeat of the cycle. He reads the second couplet, with “I look out on Queens” falling in the transitional window. Ladd then pauses for nearly an entire cycle.

[6.19] There is clarity in the formal overlap in this passage. Within the poetry, grammar and line breaks align: there is one complete thought per couplet. Ladd’s placement of the lines within the musical form draws attention to its structures, serving as an introduction to the piece’s sonic organization. Musical and poetic boundaries line up, each emphasizing the other. In addition to introducing the formal elements, Ladd and Iyer’s first interaction foregrounds listening by displaying how one hears and responds to the other. The attentive alignment, moreover, invites the audience to orient their own listening towards the interactivity of Iyer and Ladd, music and word.

Example 6. Transcription of piano and poetry cycles 16–18 [1:30–1:48]—Blurring of figuration

(click to enlarge)

[6.20] Where Ladd’s delivery may initially seem to be the more determinative factor in the formal interrelation, Iyer is able to push back against alignment, as an example from later in the track demonstrates. In cycles 17 and 18, Ladd delivers his text within the rhythmic cycles again, but now with only one line of poetry per cycle. Ladd opens the passage at [1:37] with “all trinkets of time shrink space” followed by a long pause for the transitional window, and then continues with “a cluttered reflection of collections” (Example 5). One might assume that this passage—with its long central pause—would exhibit a clarity of form similar to those heard earlier. But text placement is not the only factor here; Iyer’s music subverts Ladd’s clarity. By this point in the piece, Iyer has broken down the stack-per-cycle approach that he used for the opening couplets, now phasing in and out of it improvisatorily. In cycle 16, his stacks dissolve. While I have transcribed the cycle as having four stacks in Example 4, the boundaries between them are not nearly as discrete as earlier examples. They are blurred by shifting figuration, as shown in Example 6.(22) He continues this into cycle 17, changing stacks halfway through Ladd’s line. The sense of stable cycles separated by transitional windows is gone. While Ladd places his lines carefully within the rhythmic cycle, Iyer complicates the structure with his improvised pitch movements.

[6.21] Ladd’s straight ahead performance of the first two couplets is simplified by their preexisting structure, in that each of the first four lines tidily contains an entire clause. But in the third couplet, Ladd’s poetry breaks this pattern. After uttering a complete clause in line five (“Shade shift my way to JFK”), he delivers lines six and seven as a longer passage by means of enjambment: “Ride past INS possessing my access / In kind and card.” But Ladd unites the passage by exploiting the transitional window. Instead of waiting to enter after the downbeat of the cycle, he anticipates it, jumping in at the start of the transitional window [0:41] and speaking “shade” at the same moment Iyer changes pitch stacks. This allows him more time to stretch out his lines, with the words “and card” trailing into the next transitional window.

[6.22] Iyer described Ladd as intensely musical, as someone who has “an ear for what’s happening. He’s not someone who’s like, ‘oh this is in 11/16.’ I mean he doesn’t know that stuff or deal with it at all, but he can feel it though” (2012). Clearly, Ladd is attuned to Iyer’s musical structures, and is sensitive to their boundaries. In his improvised performance, he exploits their flexibility to play off of his own structures. Iyer contributes to the formal dialogue improvisatorily by alternately strengthening and undermining his own structural parameters.

[6.23] Example 5 offers a view into Ladd’s distribution of text in time. Note the clusters and spaces, with entire cycles left text-free throughout the excerpt. One challenge artists face when working to combine music and spoken word is what Iyer calls the “abundance, maybe hyperabundance of text” (2012). Text flows by at a speed that challenges intelligibility, much less the contemplative stance often required for poetry appreciation and comprehension. Ladd partially mitigates this challenge by using his “golden rule” for improvisation: “give space. Give lots and lots of space” (2012).

[6.24] But of course, these pauses in the poetry are not truly empty; they teem with Iyer’s arpeggios. Ladd describes their turn taking as a social dynamic:

The trick just becomes . . . everyone already being comfortable enough that they can live in those blank spaces and live in them well. So that what people are hearing is comfortable space and not a place where people are trying to be too polite and so they’re not stepping on each other or the opposite, where one person’s stepping on everything cause he or she feels that they have to carry the whole thing (2012).

Each time Ladd steps back it makes space for Iyer. Example 4 illustrates how Iyer often increases the harmonic rhythm during Ladd’s breaks, with multiple stacks per cycle common in cycles with no text, as in cycles 1–8 and 16, or with little text, as in cycles 9, 12, 17, and 18.

[6.25] Ladd and Iyer demonstrate their reciprocal responsivity from [1:52–2:10], a span I call the echo passage. The text for this passage, lines 21–23, is in many ways unlike the rest of the poem. As noted in the earlier poetry analysis, the rhythm is anapestic. Ladd avoids repetition elsewhere in the poem, but here he exploits it with a trance-like echoing effect. The otherwise strict couplet form fractures into the poem’s only group of three lines. In its written form, Ladd sets off the passage even further through italics.

[6.26] In his performance of these lines, Ladd aligns his repetitions with Iyer’s rhythmic cycle. The presence of the left-hand ostinato has until this point been the strongest rhythmic component of the performance, and at line 21 the rhythm finally makes its way into the poetry. Each of Ladd’s repeated nouns—“age,” “mirror,” and “people”—loosely coincides with Iyer’s ostinato. Ladd’s alignment is inexact, likely intentionally so to avoid breaking the flow of the poetry’s delivery, but unmistakable.

[6.27] Ladd deviates slightly from the written version of the poem in this passage to bring his poetry and Iyer’s music into full chorus. Recall that the ostinato has four pairs of A2s. In the printed poetry, each noun repeats three times, separated by shifting prepositions. But in performance, Ladd adds an iteration to the first two sections, tagging on “within an age” and “to a mirror” to lines 21 and 22, respectively. These extensions position his verse within Iyer’s cycle while maintaining the tie between the nouns and the ostinato; “age” and “mirror” each fill an entire cycle. In the third cycle of the passage, Ladd adheres more closely to the written poetry, repeating “people” three times and pausing for the final ostinato iteration. However, during the nearly twenty seconds of chorus, the repeating nouns and the ostinato begin to intermix waters. Though Iyer’s final ostinato articulation of the passage is now unaccompanied by the poetry, the nouns still echo, as they do for the remainder of the track.

[6.28] Iyer’s musical approach to the passage has the effect of bracketing it off from neighboring ones. In the cycles immediately preceding and following it, Iyer alters the texture to include some simultaneities. This textural change, which I will discuss more below, frames the arpeggiation of the echo passage. The pitch choices in the section further set off these cycles as a group. Iyer explores downward arpeggiation, removing the highest pitch (or two) when he moves from one stack to the next, and replacing it with another pitch at the bottom. This is the only instance of this kind of movement in the entire piece, again marking the passage as distinct from the rest of the poem. Iyer and Ladd communally create this italicizing effect; it emerges from Ladd’s attention to the framing power of Iyer’s cycles, and from Iyer’s recognition of the support he can offer Ladd’s poetic structure.

Example 7. S texture, rhythmic cycle 15 [1:24]

(click to enlarge)

Example 8. S1 texture, rhythmic cycle 25 [2.24]

(click to enlarge)

[6.29] At several points in the track, Iyer’s swirling right-hand pattern consolidates into simultaneities. These textural changes last for the duration of the rhythmic cycle in which they occur; these cycles are marked as S and S1 on Example 4. In the S stacks, Iyer groups the top two pitches as a simultaneity; see Example 7. The disruption of the earlier strict figuration creates additional rhythmic interest along with the texture change. As can be seen in Example 8, S1 intensifies the textural shift. Here, Iyer groups his right-hand pitches into a chord texture and alternates it against the left hand, breaking the ostinato pattern. In the subtle soundscape of “The Color of My Circumference I” these small changes in texture stand out, inviting listeners to draw interpretive associations between them. It is in these improvised turns of texture that I hear the music’s most potent influence on the poetic content.

[6.30] The first instance of S texture arrives on Ladd’s enunciation of the word “Tans” [1:24] at cycle 15. Here, Ladd reflects the earth tones mentioned in the opening lines onto his own body; the family narrative that resists the depersonalization process is also made visible by association with his skin. Iyer’s texture change underscores the word “Tans,” further pointing the listener toward the racial theme of the cycle. The top of the stack leaps from an E4 to a G4, a high point reached only once before in the track.(23) Iyer further marks the passage by adding a low octave to his ostinato, alternating between the A2 drone pitch and the new A1. This moment, which is not at all emphasized in the printed poem, finds a spotlight in Iyer and Ladd’s improvised performance. It is as though Ladd’s assertion punches through the blurry anonymity of travel, affording listeners a moment of stability in an otherwise unsettled landscape. Immediately after Ladd finishes line 16, Iyer returns to the lower, muddier texture from before.

[6.31] The next instance of S texture comes at [1:47] as the central question of the poem is voiced: “Am I a catalogue of memories / A series of possessions?” Iyer’s pitch choices here resemble those of the previous S passage; the high note is G4 and the lower two pitches oscillate stepwise. Iyer lands directly on the downbeat of the cycle with the open fifth that starts the S texture. He collapses the transitional window, changing pitch and rhythmic cycle in the same moment. This alignment happens only once in the piece, and Iyer marks it further with his textural modification.

[6.32] The arrival of the third and final S texture at [2:11] draws a thematic link between the bodily awareness of the first example and the metaphysical questions of the second. It arrives immediately after the echo passage and has the same pitch content as the first S, including the plummeting A1. The text now makes explicit the centrality of the body to the poem’s imagery: “Each image descending in view like seeing / One’s history through the core of a spine.” Having recognized his body as a vessel of his history in the first passage, Ladd turns to questions of the nature of identity. Who are we in relation to our histories? The imagery of the spine as a repository of one’s history connects the first two passages. In other words, knowledge here, is physical, residing in the raced body. And it is Iyer’s texture that draws this interpretive link.

[6.33] In all the foregoing music, Iyer has maintained the ostinato unwaveringly. At the very opening of the track, Iyer played a fleeting E2 before landing on the ostinato pitch, hinting at movement to come. By 2:20, the low A has taken on a permanence. Concurrently, the poem works to establish a self that is constituted by faceless intelligence systems and by family history and race. With Ladd’s final lines comes a fundamental turn in the poetic tone, a move from object to agent. By way of Ladd’s mother and the “old / Negro spirit of reinvention,” the closing lines assert a new possibility: a self-proclaimed. “I am a citizen of the world” / Ta da she is.”

[6.34] At this climactic moment of the track at [2:24], Iyer reinvents his ostinato as a conversation between his previously independent hands. The low A leaps up to E3, and in the S1 texture this E dances with the right hand’s chord. After two minutes of darkness and disorientation, here Iyer introduces a new clarity and brilliance. All of the conflict between the rhythmic ostinato and the shifting subdivisions of the arpeggiation is abated: there are just two hands, joining in bright rhythmic play. When Iyer returns to the lower register for the closing “Ta da she is,” it, too, is shaped by this reinvention. Iyer’s two hands now work in concert as he ushers in the other musicians to the instrumental portion of the track and opens the door for the remainder of the album.

Conclusion

[7.1] Iyer has indicated the centrality of listening to his artistic practice, saying “Music is made of us listening to each other” (Wilkinson 2016). With interactivity as a guiding principle, this analysis has listened for that listening. By attending to their conversational dynamics, this analysis demonstrates the deep responsivity between Iyer and Ladd, music and word, in their co-created work. Even as one of the simplest excerpts in the body of work they have produced, this segment richly rewards close attention. One conclusion to draw from this analysis is that the large body of recorded intermedial improvised music awaits further examination.

[7.2] Approaching this recording with a focus on sociable musicopoetics decenters the traditionally hermeneutic preoccupation of text/music relationships, and in response seeks to highlight the meaningfulness of interaction itself. Meaning emerges from the audible trace of negotiations, frictions, and concord between artists in process. In centering on this process, a reading grounded in sociable musicopoetics relinquishes some degree of interpretation, embracing opacity not as an analyst’s problem, but as a human inevitability.(24)

[7.3] What surfaces in listening to Iyer and Ladd in this way is, in part, a negotiated incommensurability. Each of them seeks common ground with the other, but at the same time each is bound by the most basic aspects of their art forms. In that middle ground between music and language, one can hear the interactivity of their creation most clearly as they find a way to converse across difference. Here, sociable musicopoetics offers something to the study of musical interaction, writ large. The divergence between language and music is just one extreme of a spectrum of differences that occur in improvising contexts. There are uncountable such discrepancies that shape musical interaction, from the instrumental divide between a pianist and a drummer to the fundamental irresolvability of two subjectivities. Listening to musical negotiations in these gaps is challenging. In part because of its degree of difference, language can offer another way in, through hearing the interactions of artists across mediums. As the study of musical interactivity continues to deepen, these intermedial analyses can remind us to “hear from the outside.”

Vilde Aaslid

University of Rhode Island

Fine Arts Center, Suite E

Kingson, RI 02281

aaslid@uri.edu

Works Cited

Agawu, Victor Kofi. 1992. “Theory and Practice in the Analysis of the Nineteenth-Century Lied.” Music Analysis 11 (1): 3–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/854301.

Albright, Daniel. 2018. “Series Editor’s Foreword.” In Walt Whitman and Modern Music: War, Desire, and the Trials of Nationhood, ed. Lawrence Kramer, ix–xv. Routledge.

Alperson, Philip. 1984. “On Musical Improvisation.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 43: 17–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/430189.

Ariff, Alexander Gelles. 2013. “Off the Beat: History and Analysis of Selected Jazz/Poetry Collaborations (1956–1959).” MA thesis, Rutgers University; Graduate School - Newark. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3805171.

Bacon, Peter. 2009. “Grand Pianoramax at the Hare & Hounds, Kinds Heath.” Birmingham Post, March 17, 2009. http://www.birminghampost.co.uk/whats-on/music/grand-pianoramax-hare--hounds-3949062.

Barton, Chris. 2013. “Review: ‘Holding It Down’ Awakens Us to Veterans’ Dreams.” Pop and Hiss: The L.A. Times Music Blog (blog), September 10, 2013. http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/posts/la-et-ms-veterans-dreams-20130910,0,5918965.story.

Berliner, Paul. 1994. Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226044521.001.0001.

Bolden, Tony. 2003. Afro-Blue: Improvisations in African American Poetry and Culture. University of Illinois Press.

Borgo, David. 2016. “Openness from Closure: The Puzzle of Interagency in Improvised Music and a Neocybernetic Solution.” In Negotiated Moments: Improvisation, Sound, and Subjectivity, ed. Gillian Siddall and Ellen Waterman, 113–30. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smt46.10.

Carter, Curtis L. 2000. “Improvisation in Dance.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 58 (2): 181–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/432097.

Chinen, Nate. 2006. “Life During Wartime, in a News Media Bombardment.” The New York Times, December 8, 2006, sec. Arts / Music. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/08/arts/music/08iyer.html.

Dempsey, Nicholas P. 2008. “Hook-Ups and Train Wrecks: Contextual Parameters and the Coordination of Jazz Interactions.” Symbolic Interaction 31 (1): 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2008.31.1.57.

Diggs, Latasha N. Nevada. 2013. “Vijay Iyer and Mike Ladd: The Hypermeter of Collaboration by LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs.” Poetry Foundation, December 2013. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet-books/2013/12/vijay-iyer-and-mike-ladd-the-hypermeter-of-collaboration.

Doffman, Mark. 2009. “Making It Groove! Entrainment, Participation and Discrepancy in the ‘Conversation’ of a Jazz Trio.” Language & History 52 (1): 130–47. https://doi.org/10.1179/175975309X452012.

Edwards, Brent Hayes. 1998. “The Seemingly Eclipsed Window of Form: James Weldon Johnson’s Prefaces.” In The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, ed. Robert O’Meally, 580–601. Columbia University Press.

—————. 2004. “The Literary Ellington.” In Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies, ed. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin, 326–56. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/omea12350-017.

—————. 2017. Epistrophies: Jazz and the Literary Imagination. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2d8qwqm.

El-Hadi, Nehal. 2018. “Ensemble: An Interview with Dr. Fred Moten.” MICE Magazine, June 6, 2018. https://micemagazine.ca/issue-four/ensemble-interview-dr-fred-moten.

Feinstein, Sascha. 1997. Jazz Poetry: From the 1920s to the Present. Greenwood Press.

Ferrandino, Matthew E. 2017. “Voice Leading and Text-Music Relations in David Bowie’s Early Songs.” Music Theory Online 23 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.4.5.

Fischlin, Daniel, and Ajay Heble, eds. 2004. The Other Side of Nowhere. Wesleyan University Press.

Fischlin, Daniel, Ajay Heble, and George Lipsitz. 2013. The Fierce Urgency of Now: Improvisation, Rights, and the Ethics of Cocreation. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smsxm.

Gillespie, Luke O. 1991. “Literacy, Orality, and the Parry-Lord ‘Formula’: Improvisation and the Afro-American Jazz Tradition.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 22 (2): 147–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/836922.

Givan, Benjamin. 2016. “Rethinking Interaction in Jazz Improvisation.” Music Theory Online 22 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.3.7.

Glissant, Édouard. 1997. Poetics of Relation. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10257.

Hannaford, Marc. 2017. “Subjective (Re)Positioning in Musical Improvisation: Analyzing the Work of Five Female Improvisers.” Music Theory Online 23 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.2.7.

Heble, Ajay, and Rob Wallace, eds. 2013. People Get Ready: The Future of Jazz Is Now! Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822399728.

Hisama, Ellie M. 2016. “Improvisation in Freestyle Rap.” In The Oxford Handbook of Critical Improvisation Studies, ed. Benjamin Piekut and George E. Lewis, 250–57. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199892921.013.24.

Hodson, Robert. 2007. Interaction, Improvisation, and Interplay in Jazz. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203944103.

Hsu, Hua. 2003. “Invisible Cities, Invisible Men.” Village Voice, May 6, 2003. http://www.villagevoice.com/2003-05-06/news/invisible-cities-invisible-men/.

Iyer, Vijay. 2004. “Exploding the Narrative in Jazz Improvisation.” In Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies, ed. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin, 393–403. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/omea12350-020.

—————. 2012. Interview with author.

—————. 2019. “Beneath Improvisation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Critical Concepts in Music Theory, ed. Alexander Rehding and Steven Rings. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190454746.013.35.

—————. 2020. “‘Opening Up a Space That Maybe Wouldn’t Exist Otherwise’/ Holding It Down in the Aftermath.” In Playing for Keeps: Improvisation in the Aftermath, ed. Daniel Fischlin and Eric Porter, 81–93. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478009122-006.

Iyer, Vijay, and Vilde Aaslid. 2021. “‘Between You and Not You’: A Conversation with Vijay Iyer.” Jazz & Culture 4 (1): 87–97. https://doi.org/10.5406/jazzculture.4.1.0087.

Iyer, Vijay, and Mike Ladd. 2003. “In What Language? A Song Cycle of Lives in Transit.” Interview with Nermeen Shaikh. Asia Society, April 3, 2003. https://asiasociety.org/what-language-song-cycle-lives-transit.

Jones, Meta DuEwa. 2011. The Muse Is Music: Jazz Poetry from the Harlem Renaissance to Spoken Word. University of Illinois Press.

Khan, Imran. 2018. “There’s a Good Ladd: An Interview with Rapper and Musician Mike Ladd.” PopMatters (blog), February 16, 2018. https://www.popmatters.com/mike-ladd-interview.

Ladd, Mike. 2012. Interview with author, by telephone.

Lewis, George E. 1996. “Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives.” Black Music Research Journal 16 (1): 91–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/779379.

Lockwood, Alan. 2006. “Dimensions in Music: Soft Power: Jazz Meets the Subcontinent.” Brooklyn Rail, November 2, 2006. http://www.brooklynrail.org/2006/11/music/dimensions-in-music-soft-power-jazz-meet.

Mackey, Nathaniel, Daniel Fischlin, and Ajay Heble. 2004. “Paracritical Hinge.” In The Other Side of Nowhere: Jazz, Improvisation, and Communities in Dialogue, ed. Daniel Fischlin and Ajay Heble, 367–86. Wesleyan University Press.

Michaelsen, Garrett. 2013. “Analyzing Musical Interaction in Jazz Improvisations of the 1960s.” PhD diss., Indiana University.

—————. 2019. “Making ‘Anti-Music’: Divergent Interactional Strategies in the Miles Davis Quintet’s The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965.” Music Theory Online 25 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.25.3.3.

Mitter, Siddhartha. 2005. “Exhilarating Jazz, Spoken Word Take off in Airport Setting.” The Boston Globe. March 28, 2005. http://www.boston.com/news/globe/living/articles/2005/03/28/exhilarating_jazz_spoken_word_take_off_in_airport_setting/.

Moten, Fred. 2003. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. University of Minnesota Press.

Nielsen, Aldon Lynn. 1997. Black Chant: Languages of African-American Postmodernism. Cambridge University Press.

Okiji, Fumi. 2018. Jazz as Critique: Adorno and Black Expression Revisited. Stanford University Press.

Robbins, Allison, and Christopher J. Wells. 2019. “Playing with the Beat: Choreomusical Improvisation in Rhythm Tap Dance.” In The Oxford Handbook of Improvisation in Dance, ed. Vida L. Midgelow, 719–34. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199396986.013.10.

Siddall, Gillian, and Ellen Waterman. 2016. Negotiated Moments: Improvisation, Sound, and Subjectivity. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smt46.

Simpson-Litke, Rebecca, and Chris Stover. 2019. “Theorizing Fundamental Music/Dance Interactions in Salsa.” Music Theory Spectrum 41 (1): 74–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mty033.

Steinbeck, Paul. 2011. “Intermusicality, Humor, and Cultural Critique in the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s ‘A Jackson in Your House.’” Jazz Perspectives 5 (2): 135–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/17494060.2011.637680.

—————. 2014. “Improvisation, Identity, Analysis, Performance.” American Music Review 44 (1): 16–19.

—————. 2016. “Talking Back: Performer-Audience Interaction in Roscoe Mitchell’s ‘Nonaah.’” Music Theory Online 22 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.3.8.

Tilley, Leslie A. 2020. Making It Up Together: The Art of Collective Improvisation in Balinese Music and Beyond. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226667744.001.0001.

Wilkinson, Alec. 2016. “Time Is a Ghost: Vijay Iyer’s Jazz Vision.” The New Yorker, January 24, 2016. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/02/01/time-is-a-ghost.

Footnotes

* I am sincerely grateful to Vijay Iyer and Mike Ladd for their time and generosity during our conversations, without which this article would not have been possible. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers; the article benefitted from their careful attention.

Return to text

1. Iyer here refers to dialectical relationships that extend beyond the participating performers, which allows even solo performances to fall under his claim (Iyer and Aaslid 2021).

Return to text

2. See, for example, Robbins and Wells 2019; Carter 2000; Simpson-Litke and Stover 2019.

Return to text

3. One exception is Steinbeck 2011. Scholarship on intermedial interactivity has been rich outside of music studies as in Nielsen 1997, Jones 2011, Edwards 2017, Bolden 2003, Moten 2003 but tends to avoid detailed engagement with musical details. Another related area of study is the analysis of freestyle hip hop as in Hisama 2016.

Return to text

4. Iyer and Ladd’s collaborations are part of a long tradition of combining poetry with jazz and creative music, with important precedents set by Langston Hughes, Charles Mingus, Amiri Barka, Archie Shepp, among many others. For more on the history of collaboration, see Feinstein 1997 and Nielsen 1997. Collaborative practice continues to flourish in current times, as in the work of Ambrose Akinmusire, Nichole Mitchell, Shabaka Hutchings, Arturo O’Farrill, and many others.

Return to text

5. For an argument in favor of including the musicians’ perspective in the analysis of improvised music, see Steinbeck 2014; for another example of this approach in analysis see Hannaford 2017.

Return to text

6. For further reflections from Iyer and Ladd on their artistic relationship and their own histories with music and poetry combinations, see Ariff 2013.

Return to text

7. For a detailed interview with Ladd that includes much information about his background and career, see Khan 2018.

Return to text

8. Recently, Iyer and Ladd have extended some of the practices that shaped the last of these pieces, Holding it Down, into a series of performances, expanding their work beyond the trilogy frame. For an account of this expansions, see Iyer 2020.

Return to text

9. In What Language emerged from a 2003 commission by the Asia Society and was released that year on Pi Recordings. The Brooklyn Academy of Music commissioned Still Life with Commentator, which was then released on Savoy Jazz in 2007. The last collaboration, Holding it Down, was commissioned to open the 2012–2013 season at The Harlem Stage at the Gatehouse and was released in September 2013 on Pi Recordings.

Return to text

10. The relationship between the conceptual structures of composition and improvisation is more nuanced than this passage allows. My work in this regard has been influenced in particular by Alperson 1984, Lewis 1996, and Gillespie 1991.

Return to text

11. Along with Monson’s foundational work, another early examination of jazz interactivity is Berliner 1994. Other texts that followed include Fischlin and Heble 2004, Borgo 2016, Dempsey 2008, Michaelsen 2013, Hodson 2007, and Doffman 2009.

Return to text

12. The centrality of community to inquiry in critical improvisation studies has emerged, in part, from the work of the Improvisation, Community, and Social Practice research project. This initiative has led to a number of publications including Heble and Wallace 2013, Fischlin, Heble, and Lipsitz 2013, and Siddall and Waterman 2016 among others.

Return to text

13. All of Iyer and Ladd’s collaborative projects exist in both live and recorded forms. My analysis of the recorded track does not capture the variability in the piece that is enacted in live performance.

Return to text

14. This approach stands in contrast to much of the text/music work influenced by Agawu 1992 such as Ferrandino 2017 as well as a significant portion of the scholarship emerging from the International Association for Word and Music Studies in the Word and Music Studies book series edited by Walter Bernhart, Michael Halliwell, Lawrence Kramer, and Werner Wolf.

Return to text

15. My use of an unexpanded “listening” here is intentional. I use it to connect the “listening” of improvisational practice with the “listening” of analysis.

Return to text

16. Although the many literary studies on the intersection of music and language in improvisation do not, in general, examine musical materials closely, there is much to learn from the insightful and deep engagements with textual analysis, as in examples such as in Mackey, Fischlin, and Heble 2004, Edwards 2004, Jones 2011, Bolden 2003, Nielsen 1997, and Feinstein 1997.

Return to text

17. The two components Ladd references here are the music, of course, but also the video art that accompanied each of the live performances.

Return to text

18. In 2020, Iyer and Ladd released the instrumental tracks of In What Language as a separate release, InWhatStrumentals, suggesting that Ladd’s view of the poetry’s autonomy also holds for Iyer’s view of the music.

Return to text

19. Exceptions include a simultaneity texture that I will discuss later; there are also a few instances when Iyer breaks a strict top to bottom ordering in his arpeggio, but these are quite infrequent.

Return to text

20. Iyer occasionally begins the pitch change one or two subdivisions before what I’m calling the “transitional window,” because of how the figuration unfolds.

Return to text

21. In our interview, Iyer described the opening part of the movement as fully improvised except for the metrical structure (Iyer 2012).

Return to text

22. This texture change makes clear the shortcomings of transcription as a tool both for creating and reading analysis. I have provided track timings throughout in the hope that readers will listen for themselves.

Return to text

23. The stacks that contain these Gs are identical; however, the textural difference masks their pitch relationship.

Return to text

24. In using “opacity” in this way, I am drawing on Édouard Glissant and Fred Moten’s read of Glissant. First, Glissant: “How can one reconcile the hard line inherent in any politics and the questioning essential to any relation? Only by understanding that it is impossible to reduce anyone, no matter who, to a truth he would not have generated on his own. . . [opacity is] the force that drives every community: the thing that would bring us together forever and make us permanently distinctive. Widespread consent to specific opacities is the most straightforward equivalent of nonbarbarism. We clamor for the right to opacity for everyone” (Glissant 1997, 194). Marc Hannaford first directed my attention to the possible applicability of this passage to music analysis. Fred Moten sees Glissant’s opacity as an opening for a certain relation to the object: “I feel like what opacity implies is a kind of ongoing devoted thinking, but again, for me, it’s not only a thinking of the object in question, but it’s also a thinking that is, at the same time, through the object in question. Or another way to put would be, again not just seeing something, but also seeing through something. And within that context, knowing is a project, is an activity, that doesn’t come to an end” (El-Hadi 2018).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2022 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.