The Melodic Organization of The Rite of Spring

Joseph N. Straus

KEYWORDS: Stravinsky, Rite of Spring, melody, drama, transpositional combination, voice leading.

ABSTRACT: Most previous analytical studies of The Rite of Spring have focused on its harmony and rhythm. This article shifts attention to its melodies—mostly short fragments that move repetitively within a narrow registral frame—and shows that they take on expressive meanings closely linked with the work’s dramatic scenario. In addition to operating in the manner of Wagnerian leitmotivs in relation to characters or dramatic situations, they are often bound together in expressive families through the manipulation of their dyads.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.28.4.8

Copyright © 2022 Society for Music Theory

[1] Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is a ballet with dramatic characters and a loose narrative arc. Although it is usually performed as a concert piece, its meaning is deeply bound up with its dramatic scenario. At the same time, the music itself creates meanings. These many-layered meanings are ambiguous, sometimes even self-contradictory; always, they are difficult to tease out. The expressive dimension of this music has many different aspects, including familiar topics like fanfare and march but extending far beyond them.

[2] In most analytical studies of the music of The Rite of Spring, attention has focused on its harmony (as in Forte 1978, whose title I have adapted here) and rhythm.(1) I focus here instead on its melodies, both on their construction and on the musical meanings they create.(2) Stravinsky is not much known as a melodist, and indeed the melodies in this work move repetitively within small registral frames and generally eschew any of the traditional markers of melodic beauty and emotional expression. I will show that the Rite’s melodies are aesthetically suited to their expressive purpose, and that they are systematically interlinked to create rich networks of musical meaning that dovetail in mutually reinforcing ways with the ballet scenario.

I. Drama, Expression, Meaning

[3] Stravinsky devised The Rite of Spring’s scenario—the basic dramatic plan—in collaboration with an artist and archeologist named Nicolas Roerich, widely considered at the time to be the foremost authority on pagan, prehistoric Russia.(3) Stravinsky and Roerich planned a series of loosely connected scenes associated with the coming of spring, culminating in the sacrifice of a young woman by a primitive, preliterate, preagricultural people to propitiate their Sun God, Yarilo. They arranged the ballet in two parts, each containing six or seven scenes, with many of the scenes further divided into distinct episodes.

[4] In Nijinsky’s choreography for the initial performances of the Rite, created with Stravinsky’s close involvement, the ballet deploys four groups of dramatic characters.(4)

- Girls/Young Women (including the Chosen One). Sometimes they are girls, as in Augurs of Spring, and sometimes they are fertile young women, as in Dancing Out of the Earth.

- Boys/Young Men. They are boys in Augurs (as they learn augury from the Old Woman), but fully sexualized men in the later scenes of Part One. They are entirely absent from Part Two, which is devoted to the Young Women and the Old Men.

- The Old Woman. This is a group of one. She appears onstage only early in Part One, although her tritone-based, chromatic music is prefigured in the Introduction to Part One and returns late in Part Two (in Ritual Action of the Ancestors). She is understood musically as an “exotic” character, superhuman in her age and her divining ability.

- Old Men (Sage/Elders/Ancestors). They are the embodiment of patriarchal power.

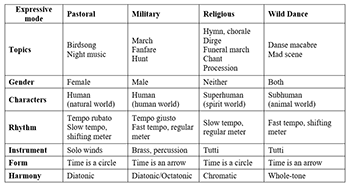

Example 1. Four expressive modes, with associated musical topics, dramatic features, and musical characteristics

(click to enlarge)

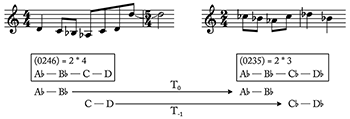

[5] These dramatic characters engage four expressive modes or registers: the pastoral, the military, the religious, and the wild dance. Although the boundaries between these modes are not always clear and may intermingle to some extent, most of the scenes (or the larger sections thereof) can be ascribed to one of the four. In that sense, each scene is thus a movement, both in the sense of a symphonic movement and in the sense of a set of characteristic gestures, motions, and musical actions (see Example 1). As described below the example, each of the expressive modes engages a distinctive group of musical topics, dramatic features, and musical characteristics.(5)

[6] 1. Pastoral. The pastoral is associated with nature and the sights and sounds of the natural world. It is springtime—the ice cracks and melts, new greenery emerges from the earth, people move outside from their cold-weather confinement. It is a time of fertility, of renewal and rebirth. This expressive mode is thus associated with the female, including the traditional linkage of women with fertility, birth, and time’s periodicity and circularity and, as a result, the Girls and Young Woman usually are characterized musically in pastoral mode. It is also associated with the night, in particular its mystery, irrationality, and enchantment. In the Rite, the pastoral mode is manifested musically in the sounds of the natural world (such as birdsong) and in the sound of shepherd’s pipes (the dudki to which Stravinsky refers in letters describing the ballet’s opening scene).(6) The instrumentation features solo winds. The ambient sound world skews toward the diatonic. The melodies often imitate folk styles of cantillation, with frequent grace notes. Pastoral scenes are often marked by an absence of a steady rhythmic pulsation (tempo rubato) and a sense of rhythmic haziness (in the manner of “night music”). Scenes in pastoral mode are often circular in design: they end where they begin.

[7] 2. Military. The military mode is associated with young men engaged in combat or symbolic combat. Hypermasculinity and violence against women are among its defining traits. The musical manifestations of the military mode include traditional musical topics, such as hunt and fanfare. While the pastoral emphasizes solo winds, the military deploys massed brass and percussion, including string and wind instruments used percussively. Tempos tend to be stricter, with steady, sharply articulated rhythmic pulsation. The harmonic ambience is often mixed octatonic and diatonic. The form of military-oriented scenes tends to be accumulative—a gradual buildup of layers toward a climax. In other words, it is directed rather than circular.

[8] 3. Religious. The religious mode is associated with old people (The Old Woman, the Sage, the Elders) and deceased people (the Ancestors). These figures are superhuman, understood to be above the normal human crowd of young men and women. To some extent, they are exoticized Others. The Old Woman has the gift of divination; the Sage and Elders are the religious priests, the leaders of the rites of spring. Musically, this expressive mode manifests as chant, ritual, procession, and chorale. Sometimes, in affiliation with the exotic, it manifests as sinuous chromaticism.

[9] 4. Wild dance. Wild dances represent the end (or before the beginning) of civilization, with its sense of restraint and decorum. These are savage, violent, animalistic descents into unrestrained sexuality and/or death. The Rite has two wild dances: Dance of the Earth (at the end of Part One) and Sacrificial Dance (at the end of Part Two). Dance of the Earth is an orgiastic dance of life; Sacrificial Dance is a dance of death. The same expressive mode also penetrates into other scenes, especially the Naming and Honoring of the Chosen One. If the religious mode has something of a spiritual aspiration upward toward the superhuman, these wild dances mark a frenzied, mad descent into the subhuman, the bestial. They also convey a sense of fate or fatality; if the pastoral is marked by gentle circularity of form, these wild dances are marked by a sense of inexorable forward movement toward an inescapable fate, with a corresponding accumulation of textural layers. The whole orchestra plays in these dances: tutti (the crowd) rather than soli (the individual). Percussion and brass are dominant. The ambient sound-world is shaped by the persistent presence of the whole-tone scale.

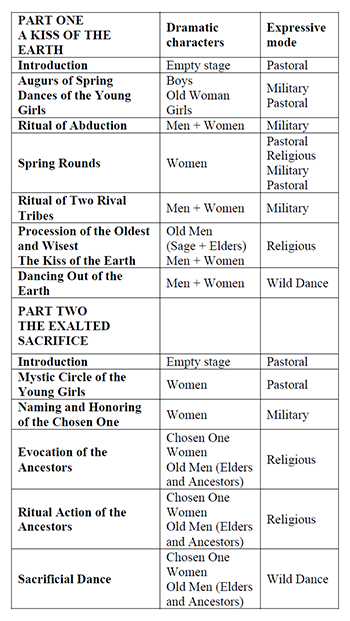

Example 2. The scenes of the ballet in relation to dramatic characters and expressive modes

(click to enlarge)

[10] As the ballet unfolds, these four expressive modes tend to occur in a particular order, and each of the two parts of the ballet roughly follows the same trajectory: PASTORAL → MILITARY → RELIGIOUS → WILD DANCE (see Example 2).

II. Melodic Frames

[11] Stravinsky’s melodies throughout his compositions are usually based on short fragments, often segments of scales, that are repeated and combined in various ways. In The Rite of Spring, the melodies are central to the drama. In an almost Wagnerian way, the melodies often denote a particular character or dramatic situation. On that basis, I have created descriptive labels for all the Rite’s principal melodies, from the Opening Folk Tune to The Chosen One’s Final Cry; these are given in the Appendix).

[12] Most of the melodies in The Rite of Spring span a perfect fourth, a tritone, or a perfect fifth. Melodies that span a perfect fourth usually represent human characters like the Young Women or the Young Men; melodies that span a tritone usually represent fantastic, exoticized characters like the Old Woman; and melodies that span a perfect fifth often represent the sounds of the natural world, or human nature in its more violent, animalistic manifestations.

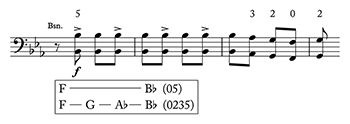

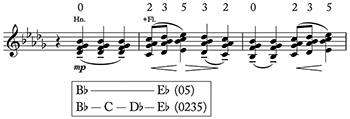

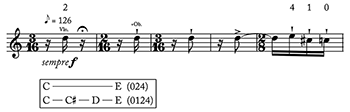

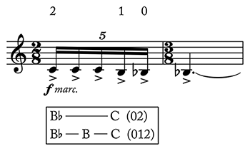

Melodies spanning a perfect fourth: (05) filled as (0235)

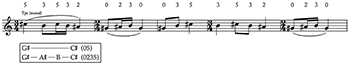

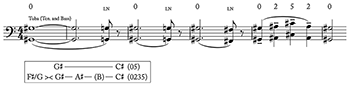

[13] Melodies that span a perfect fourth (05) generally fill that interval as a Dorian tetrachord: (0235). The melodies generally meander through the tetrachord, moving in fits and starts. In most cases, descending motion predominates, with the top note serving as the source and the bottom note as the goal, although usually not confirmed by a strong cadence. Their downward trajectory often gives them the feel of heaviness, of being pulled down to earth. In that way, they resonate suggestively with frequently remarked aspects of Nijinsky’s choreography. While they are primarily associated with human characters, their use is pervasive throughout the ballet, extending to the Sage and the other Old Men (see Examples 3–8).

Example 3. The Melody of the Young Men, as they learn divination from the Old Woman (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 4. The Spring Rounds Procession (click to enlarge and listen) |

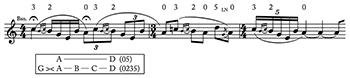

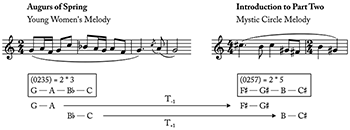

Example 5. The Women’s Entreaty, as they try to intercede in the warlike games among the men (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 6. The Earth Melody, part of a wild, orgiastic dance for male and female dancers (Dancing Out of the Earth, Reh. 75) (click to enlarge and listen) |

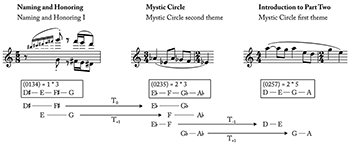

Example 7. Mystic Circle Second Theme (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 8. The Sentence of Doom, heard as the tribal Ancestors and Elders pass their final, fatal judgment on the Chosen One (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 9. The Opening Folk Tune is the only actual folk melody in the ballet that is complete and presented in something like its original form

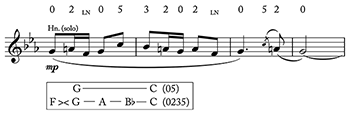

(click to enlarge and listen)

[14] Melodies that span a perfect fourth often feature a lower neighbor note, which decorates the lowest note of the span (see Examples 9–11). There is the possibility of interpretive ambiguity here, as the notes I am calling lower neighbors might be heard instead to extend the melodic frame from a perfect fourth to a tritone or perfect fifth. But, for the most part, these lower neighbor notes are short in duration and metrically weak, moving immediately to the more stable lowest note of the perfect fourth frame.

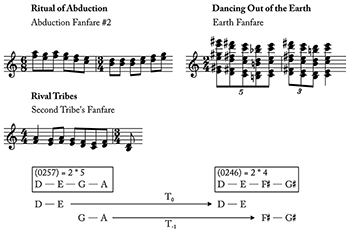

Example 10. The Young Women’s Melody marks their entrance onstage and accompanies their first dance (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 11. The Earth Melody (variant), now in chattering sixteenth notes (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 12. Nature Melody #3 is one of a number of melodies designed to represent sounds of nature, including ancient shepherd’s reed pipes called “dudki.”

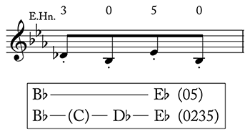

(click to enlarge and listen)

[15] The Dorian tetrachord is sometimes presented only in part, with (025) or (035) standing in for the complete (0235) (see Examples 12–14). In many cases, the implied (0235) is later stated in its entirety.

Example 13. The four-note Motto Ostinato that runs through the entire Augurs of Spring (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 14. The Sage’s Melody represents The Sage and the tribal Elders from the first moment they come onstage (click to enlarge and listen) |

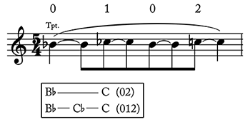

Melodies spanning a tritone: (06) divided as (0336) or (0246), or presented partially as (024) or (02)

[16] The second of the three principal melody types falls within the span of a tritone. Some of these tritone-based melodies divide the tritone into two minor thirds (3+3 or 0336), with the upper minor third often filled in chromatically. As with the (0235) melodies, the (0336) melodies usually descend. Melodies of this type are strongly associated with the Old Woman, who is described by Stravinsky as “half human and half beast.” She is hundreds of years old: a seer and a diviner.(7) More broadly, these melodies are associated with the exotic or the fantastic (see Examples 15–18).

Example 15. In the opening measures of the ballet, just after the Opening Folk Tune, we hear a brief premonition of the Old Woman’s Melody (Introduction to Part One, Reh. 1) (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 16. A bit later in the Introduction to Part One, still before any dancers have come onstage, there is a more extended preview of the Old Woman’s Melody (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 17. When the Old Woman does arrive onstage, at the beginning of Augurs of Spring, we hear her melody in its definitive form (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 18. Exotic Melody #2—chromatic, snaky, serpentine—is one of three such tunes with which the Ancestors and Elders seek to mesmerize and immobilize the Chosen One (click to enlarge and listen) |

[17] In addition to its division into two minor thirds, the tritone may also be divided into three major seconds, as 2 + 2 + 2, or (0246). Melodies organized like this, like most of the melodies in The Rite of Spring, tend to move downward. These (0246) melodies are particularly conspicuous in the wild dances of life or death that come at the ends of the two parts of the ballet, the Dance of the Earth and the Sacrificial Dance. They often seem to suggest either the mysterious/mystical or an implacable fate (see Examples 19–20).

Example 19. The Earth Fanfare is part of a wild, orgiastic dance of life (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 20. The theme of Final Judgment, representing an implacable fate (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 21. This short melody is part of a mysterious Sinuous Counterpoint

(click to enlarge and listen)

[18] The (0246) frame is sometimes presented only in part: as a major third divided into a pair of whole tones (0224) or as a single whole tone divided into a pair of semitones (0112). Even in partial presentation, these melodies often still carry the associative implications of the full collection: the mysterious/mystical or the implacable/fateful (see Examples 21–25).

Example 22. Exotic Melody #1 moves in a similarly sinuous and chromatic way within its (024) frame (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 23. This Circle Dance for Old Men is another chromatic melody used by the Elders and Ancestors as they circle their victim, but this one is more aggressive than charming (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 24. This is The Chosen One’s Cry—her principal tune as she enacts her dance of death (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 25. The Fatality Motive represents an implacable fate (click to enlarge and listen) |

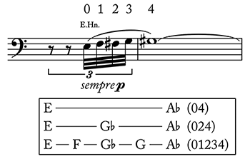

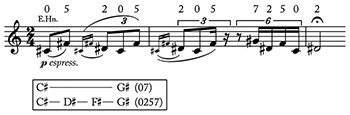

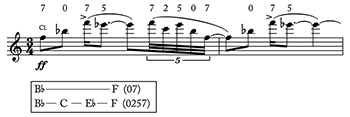

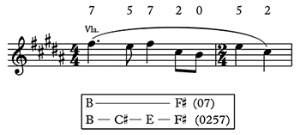

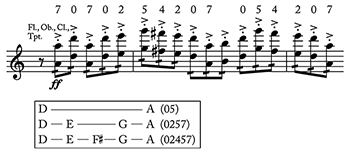

Melodies spanning a perfect fifth: (07) divided as (0257), sometimes further filled as (02357) or (02457)

[19] The third of the three principal melody types involves melodies spanning a perfect fifth. Usually, the perfect fifth is filled in as (0257). These melodies are often associated with the sounds of the natural world, in particular the gentler side of nature as evoked by the pastoral woodwind pipes known as dudki (see Examples 26–29).

Example 26. Nature Melody #1 is the first of several melodies in the Introduction to Part One that represent the sounds of the natural world (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 27. In Nature Melody #4, the shepherd’s pipes are now evoked by a solo oboe (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 28. In another nature melody from the Introduction to Part One, (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 29. The Mystic Circle Melody has a natural, sweet, unforced quality (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 30. Abduction Fanfare #1 is violent, martial music that represents the men seizing the women in an orgy of sexual violence

(click to enlarge and listen)

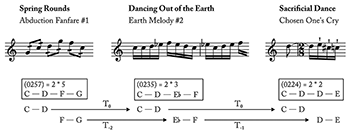

[20] Sometimes, the perfect fifth melodies are further filled in as (02357) or (02457), i.e., minor or major scalar pentachords. These filled-in tunes are often associated with a darker side of nature, including human nature in its animalistic, violent, and aggressive aspects (see Examples 30–32).

Example 31. Abduction Fanfare #2 is a musical celebration of male sexual violence (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 32. Abduction Fanfare #2 returns in a later scene, as the music for the second of the Two Rival Tribes (click to enlarge and listen) |

TC Voice Leading

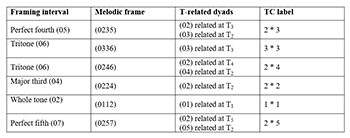

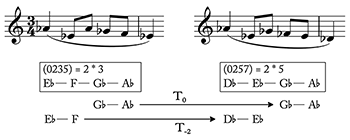

[21] The melodic frames we have discussed, which account for virtually all the melodies in The Rite of Spring, share the property of transpositional combination (TC). That is, they can be disaggregated into two subsets related by transposition.(8) More specifically, Stravinsky’s melodic frames are tetrachords that consist of T-related dyads (see Examples 33–34).(9)

Example 33. The TC property in the Rite’s principal melodic frames (click to enlarge) | Example 34. The TC property in three additional rarely used melodic frames (click to enlarge) |

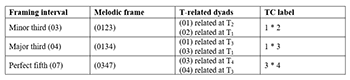

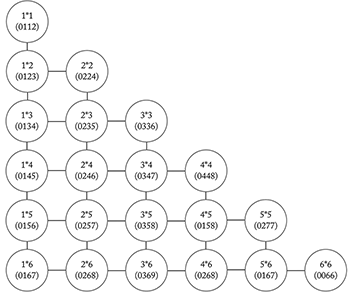

[22] Melodies that share the TC property can be varied and connected in a process of expansion or contraction. For example, two tetrachords might be related by holding one dyad fixed and moving the other dyad by a semitone. Or possibly both dyads might move, possibly by other intervals of transposition. The shared TC property can thus be the source of musical continuity and meaning, as chains of motives and families of related motives are forged. The linking of melodies in this way may call attention to subtle affinities among topics, characters, and events, or heighten a sense of affective contrast.

Example 35. Voice-leading space for tetrachordal set classes with the TC property

(click to enlarge)

[23] To enable a clear sense of the associative possibilities, Example 35 locates Stravinsky’s melodic frames on a TC voice-leading space.(10) The nodes in the space are the tetrachords (including multisets) with the TC property. The lines that connect the nodes represent parsimonious TC voice leading: one dyad stays the same while the other moves up or down by semitone.(11)

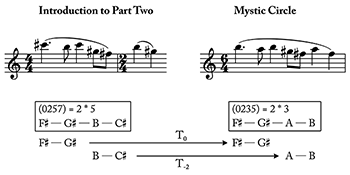

[24] In some cases, TC voice leading connects different versions of the same melody (see Examples 36–37).

Example 36. Two versions of the Final Judgment melody, representing (0246) and (0235) (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 37. Two versions of the Mystic Circle Second Theme, representing (0235) and (0257) (click to enlarge and listen) |

[25] TC voice leading has musical consequences beyond simple thematic variation: it can serve as a means for binding melodies into families of affinity, networks of melodies that not only share affective impact, but also move the narrative forward. It can subtly communicate narrative information. Much of the drama of The Rite of Spring is conveyed through its melodies, and much of the melodic story is told through TC voice leading.

Example 38. A network of melodies associated with the Sage and the other Old Men

(click to enlarge and listen)

[26] Melodies associated with the Old Men (Sage, Elders, Ancestors), for example, are bound together in a network of parsimonious TC voice leading (see Example 38). The melodies most closely associated with the Sage, The Sage’s Melody and The Sentence of Doom, occur within the same 0235-frame:

Example 39. A voice-leading network that further connects melodies associated with the Sage and other Old Men, and links them with the Old Woman

(click to enlarge and listen)

[27] Similarly, the Sinuous Counterpoint and the Fatality Motive share the same compressed tonal space:

Example 40. A voice-leading network that connects melodies associated with the Young Men, with male violence, and with the military expressive mode

(click to enlarge and listen)

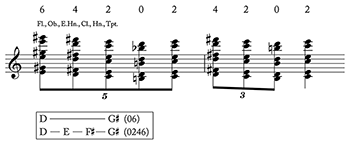

[28] A series of melodies depicting the young men at the center of the action are similarly bound together via TC voice leading in a network of affinities (see Example 40). All occur at moments of male assertion and predominance, two of which instantiate male violence against women (the Abduction Fanfares). All of them, especially the fanfares, epitomize the masculinized military expressive mode.

Example 41. The two Mystic Circle melodies (first theme and second theme)

(click to enlarge and listen)

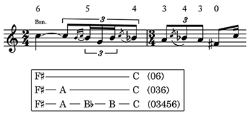

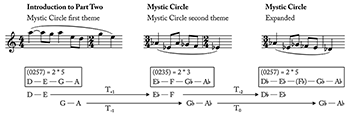

[29] We have already seen (Example 37) that the two versions of the Mystic Circle Second Theme, one moving within (0235), the other expanded to (0257), are linked by TC voice leading. Upon further examination, we discover that both Mystic Circle melodies—including their variants and transpositions—lie at the center of a network of melodies associated with the Young Women and with their feminized pastoral mode (see Example 41).

[30] Like the second theme, the Mystic Circle First Theme is also subjected to processes of expansion and contraction (see Examples 42–43).

Example 42. A larger transposition up by whole tone (T2) is achieved in stages, as each whole tone within the melody moves independently (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 43. A large-scale motivic contraction connects statements of the Mystic Circle First Theme (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 44. Two melodies associated with Young Women and exemplifying the feminized pastoral mode

(click to enlarge and listen)

[31] The Young Women’s Melody from Augurs of Spring, the tune that dominates the Dances of the Young Women, is part of the network of Young Women’s melodies centered on the Mystic Circle Second Theme (see Example 44).

[32] The principal melody for The Naming and Honoring of the Chosen One, moves within the melodic frame D#-E-F#-G (0134) (see Example 45). This frame is unique in the ballet, but can be related via TC voice leading to the network of melodies associated with the Young Women. Indeed, this scene is a dance for the Young Women as they encircle and taunt the Chosen One. Note that it is in a military rather than pastoral mode, reflecting Stravinsky’s intention to associate the women in this scene with Amazonian warriors.(12)

[33] An additional theme from the same Amazonian scene is similarly embedded in the network of women-centered melodies (see Example 46).

Example 45. The Amazonian principal theme of The Naming and Honoring of the Chosen One maintains the connection with Young Women, but transforms the expressive mode from pastoral to military (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 46. Another Amazonian, military theme from The Naming and Honoring of the Chosen One is also part of the women-centered network (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 47. Linkage of the Old Woman’s Tune, Exotic Melody #3 (which Craft calls “snake charming”), and the Chosen One’s Cry

(click to enlarge and listen)

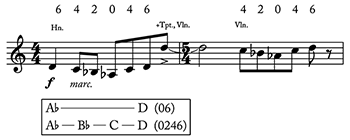

[34] A different network of melodies involving The Chosen One’s Cry connects this singular young woman with the singular Old Woman and with the exoticism she embodies (see Example 47). As noted earlier, the Young Women are primarily associated with the feminized pastoral mode but may also express the military mode. By virtue of shared gender with the Old Woman, they may be associated with a number of her aspects as well, such as supernaturalism and exoticism. Robert Craft apparently referred to the melody I am calling Exotic Melody #3 as “snake charming,” capturing something of its sinuous, beguiling quality (cited in Hill 2000, 19). In the Old Woman’s Tune, the upper minor third is filled in chromatically, as is the lower major second in The Chosen One’s Cry.

Example 48. Different musical characterizations of the female

(click to enlarge and listen)

[35] The transposition of the Chosen One’s Cry links it to women’s melodies from earlier in the ballet, and reminds us that the Chosen One, despite her special status, remains a Young Woman (the group from which she was chosen) (see Example 48). As in Example 47, the lower major second of the Chosen One’s Cry is filled in chromatically.

[36] TC voice leading can create affinities not only among associated characters but also among melodies that share an expressive topic. For example, the fanfare topic is common in the Rite and usually (but not always) associated with the Young Men and with the masculinized military mode. Various fanfares are linked via TC voice leading (see Examples 49–50).

Example 49. The Earth Fanfare in relation to Abduction Fanfare #2 and the Second Tribe’s Fanfare (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 50. A different melody from Dancing Out of the Earth also has fanfare qualities, and is linked via TC voice leading with other fanfare melodies in the ballet (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 51. The Women’s Entreaty as a compression of the Second Tribe’s Fanfare

(click to enlarge and listen)

[37] While TC voice leading is generally used to bind together affinity networks of melodies from different scenes, it may also be used to relate melodies with contrasting expressive modes that appear within the same scene. In the Ritual of the Two Rival Tribes, for example, the Women’s Entreaty at both of its transposition levels represents an expansion of the Second Tribe’s Fanfare at both of its transposition levels (see Example 51). The women compress the men’s music and change its affective impact from pastoral to military in the process.

Pitch location

Example 52. A basic opposition between feminine, pastoral melodies within A-D and ponderous, religious processions for Old Men within

(click to enlarge and listen)

[38] Previous discussion has largely focused on the voice leading connections among melodies that occupy different melodic spans and are found in different pitch locations. But, to some extent, pitch location itself conveys a reasonably consistent symbolic meaning. For example, melodies that lie within the perfect fourth,

[39] The opposition between pastoral, feminized A-D melodies and violently religious

Example 53. The transposition of the Opening Folk Tune from A-D to

(click to enlarge and listen)

[40] That musical shift from A-D to

[41] In the concluding section of the Sacrificial Dance, and of the ballet as a whole, the Chosen One resumes her dance, her Cry, and her Fanfare, with increasing intensity and wildness, culminating in her death. Her music appears not in its original pitch, but transposed up a perfect fifth, from D to A. At that higher level, it recalls and culminates musical events from earlier in the ballet, especially the opening scene. It is the end of a long journey, but also a symbolic return to its opening, the dark hour just before dawn and the bursting forth of spring.

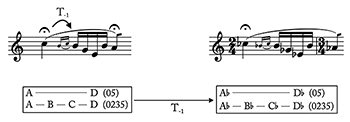

Example 54. The final measures of the ballet recall and demonically parody the Opening Folk Tune, especially the emphasis on the interval A-C within the A-B-C-D frame

(click to enlarge and listen)

[42] The harmony, which is expressed purely by the powerful alternation of A and C in the contrabasses, tuba, and timpani, affirms the A-centricity of the block and strongly recalls the opening folk tune (see Example 54). The final measures of the ballet—a musical representation of the violent, brutal, ritual murder of a young woman—recalls the feminized pastoral opening of the ballet and the gentle folk melody quoted there. The structure of the ballet is thus basically circular: the musical materials from the opening return at the end, but now in a radically different expressive mode, a demonic parody. The life of a young woman and the narrative arc of this ballet are now complete.

Appendix

Appendix: Principal Melodies [PDF]

Joseph N. Straus

Ph.D. Program in Music

Graduate Center, CUNY

365 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10016

jstraus@gc.cuny.edu

Works Cited

Agawu, Kofi. 2009. Music as Discourse: Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195370249.001.0001.

Antokoletz, Elliott. 1986. “Interval Cycles in Stravinsky’s Early Ballets.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 39 (3): 578–614. https://doi.org/10.2307/831628.

Berg, Shelley. 1988. “Le Sacre du Printemps”: Seven Productions from Nijinsky to Martha Graham. UMI Research Press.

Bernard, Jonathan. 2013. “Le Sacre Analyzed.” In Avatar of Modernity: The Rite of Spring Reconsidered, ed. Hermann Danuser and Heidy Zimmermann, 284–305. Boosey & Hawkes.

Boulez, Pierre. 1991. “Stravinsky Remains.” In Stocktakings from an Apprenticeship, ed. Paule Thévenin, trans. Stephen Walsh, 111–140. Clarendon Press.

Chua, Daniel. 2007. “Rioting with Stravinsky: A Particular Analysis of The Rite of Spring.” Music Analysis 26 (1–2): 59–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2249.2007.00250.x.

Code, David. 2007. “The Synthesis of Rhythms: Form, Ideology, and the ‘Augurs of Spring’.” The Journal of Musicology 24 (1): 112–166. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.2007.24.1.112.

Cohn, Richard. 1987. “A Theory of Transpositional Combination for Twentieth-Century Music.” PhD diss., Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester.

—————. (1988). “Inversional Symmetry and Transpositional Combination.” Music Theory Spectrum 10: 19–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/745790.

—————. 2003. “A Tetrahedral Graph of Tetrachordal Voice-Leading Space.” Music Theory Online 9 (4). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.03.9.4/mto.03.9.4.cohn.php.

Craft, Robert. 1988. “Counterpoint and Choreography.” The Musical Times 129 (1742): 171–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/965310.

Forte, Allen. 1978. The Harmonic Organization of The Rite of Spring. Yale University Press.

Frymoyer, Johanna. 2012. “Rethinking the Sign: Stylistic Competency and Interpretation of Musical Textures, 1890–1920.” PhD diss., Princeton University.

—————. 2017. “The Musical Topic in the Twentieth Century: A Case Study of Schoenberg’s Ironic Waltzes.” Music Theory Spectrum 39 (1): 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtx004.

Grabócz, Márta. 2002. “Topos et Dramaturgie: Analyse des signifiés et de la stratégie dans deux movements symphoniques de Béla Bartók.” Degrés 30 (109–110): 1–18.

Griffiths, Paul and Edmund Griffiths. 2013. “The Shaman, the Sage, and the Sacrificial Victim—and Nicholas Roerich’s Part in It All.” In Avatar of Modernity: The Rite of Spring Reconsidered, ed. Hermann Danuser and Heidy Zimmermann, 42–58. Boosey & Hawkes.

Hill, Peter. 2000. Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring. Cambridge University Press.

Hodson, Millicent. 1996. Nijinsky’s Crime against Grace: Reconstruction Score of the Original Choreography for “Le Sacre du Printemps.” Pendragon Press.

—————. 2017. “Death by Dancing in Nijinsky’s Rite.” In The Rite of Spring at 100, ed. Severine Neff, Maureen Carr, and Gretchen Horlacher, 47–80. Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt2005z70.11.

Hodson, Millicent, and Kenneth Archer. 2014. The Lost Rite: Rediscovery of the 1913 “Rite of Spring.” KMS Press.

Horlacher, Gretchen. 2011. Building Blocks: Repetition and Continuity in the Music of Stravinsky. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2017. “Rethinking Blocks and Superimposition: Form in the ‘Ritual of the Two Rival Tribes.’” In The Rite of Spring at 100, ed. Severine Neff, Maureen Carr, and Gretchen Horlacher, 331–38. Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt2005z70.28.

Jordan, Stephanie. 2007. Stravinsky Dances: Re-visions Across a Century. Dance Books.

Narum, Jessica. 2013. “Sound and Semantics: Topics in the Music of Arnold Schoenberg.” PhD diss., University of Minnesota.

O’Donnell, Shaugn. 1997. “Transformational Voice Leading in Atonal Music.” PhD diss., City University of New York.

Pople, Anthony. 1989. Skryabin and Stravinsky, 1908–1914: Studies in Theory and Analysis. Garland Publishing.

Russell, Jonathan. 2018. “Harmony and Voice-Leading in The Rite of Spring.” PhD diss., Princeton University.

Straus, Joseph. 2001. Stravinsky’s Late Music. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2014. “Harmony and Voice Leading in the Music of Stravinsky.” Music Theory Spectrum 36 (1): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtu008.

Stravinsky, Igor. 1913. “Ce que j’ai voulu exprimer dans ‘Le sacre du printemps.’” Montjoie! 8 (29 May).

Stravinsky, Vera, and Robert Craft. 1978. Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents. Simon and Schuster. https://doi.org/10.2307/3395620.

Taruskin, Richard. 1996. Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works Through Mavra. University of California Press.

Tymoczko, Dmitri. 2002. “Stravinsky and the Octatonic: A Reconsideration.” Music Theory Spectrum 24 (1): 68–102. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2002.24.1.68.

Van den Toorn, Pieter. 1986. “Octatonic Pitch Structure in Stravinsky.” In Confronting Stravinsky, ed. Jann Pasler, 130–56. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520332461-010.

—————. 1987. Stravinsky and The Rite of Spring: The Beginnings of a Musical Language. University of California Press.

—————. 2017. “The Physicality of The Rite: Remarks on the Forces of Meter and Their Disruption.” In The Rite of Spring at 100, ed. Severine Neff, Maureen Carr, and Gretchen Horlacher, 285–303. Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt2005z70.26.

Whittall, Arnold. 1982. “Music Analysis as Human Science? Le Sacre du printemps in Theory and Practice.” Music Analysis 1 (1): 33–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/853990.

—————. 2002. “Defusing Dionysus? New Perspectives on The Rite of Spring.” Music Analysis 21 (1): 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2249.00151.

Woodruff, Eliot Ghofur. 2006. “Metrical Phase Shifts in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.” Music Theory Online 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.12.1.1.

Footnotes

1. In addition to Forte 1978, principal analytical studies of The Rite of Spring include Antokoletz 1986, Boulez 1991, Bernard 2013, Chua 2007, Code 2007, Hill 2000, Horlacher 2011 and 2017, Pople 1989, Russell 2018, Taruskin 1996, Tymoczko 2002, van den Toorn 1986, 1987, and 2017, Whittall 1982 and 2002, and Woodruff 2006.

Return to text

2. Although melodies have not been the principal focus of previous studies, Taruskin 1996 considers at length their possible folk sources, and Hill 2000, Russell 2018, and van den Toorn 1987 provide valuable information about their construction. Horlacher 2011 and 2017 focus on the melodies’ temporal aspect, more specifically how they shape phrases and impart directionality, either fostering or resisting closure.

Return to text

3. The collaboration with Roerich and the resulting ballet scenario are discussed in Taruskin 1996 and Griffiths and Griffiths 2013.

Return to text

4. Nijinsky’s choreography was used only for the first nine performances of The Rite of Spring, and was undanced and forgotten until the Joffrey Ballet’s 1987 reconstruction by Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer. Their reconstruction has been staged by several dance companies in the years since and is widely available on video. My analysis of the drama makes frequent reference to this reconstruction, although more to its broad outlines than its gestural specifics. The Hodson/Archer reconstruction of Nijinsky is described in Hodson and Archer 2014 and Hodson 1996 and 2017. For additional commentary on Nijinsky’s choreography, where some of it critical of the Hodson/Archer reconstruction, see Berg 1988, Craft 1988, and Jordan 2007.

Return to text

5. For a valuable introduction to issues of topicality in twentieth-century music, and a topical analysis of The Rite of Spring that resonates with and underpins the current study, see Frymoyer 2012. On topics more generally in twentieth-century music, including the music of Stravinsky, see Agawu 2009, Frymoyer 2017, Grabócz 2002, Narum 2013, and Straus 2001.

Return to text

6. According to Stravinsky, “The orchestral introduction is a swarm of spring pipes [dudki]” (Letter from December 15, 1912, quoted in Taruskin 1996, 874).

Return to text

7. “In the first scene, some adolescent boys appear with a very old woman, whose age and even whose century is unknown, who knows the secrets of nature, and teaches her sons Prediction. She runs, bent over the earth, half-woman, half-beast.” Stravinsky 1913, cited and translated in Stravinsky and Craft 1978, 525.

Return to text

8. Transposition Combination (TC) and its theoretical development are the work of Richard Cohn. See Cohn 1987 and 1988.

Return to text

9. The combinations of two perfect fifths described in Straus 2014 as the basis for Stravinskian harmony also share the TC property. They can be represented as 5 * n, where n is any of the six interval classes. The relationship between melody and harmony is beyond the scope of this paper.

Return to text

10. This voice-leading space corresponds to one tier of the tetrahedron devised in Cohn 2003, with multisets added. It can also be thought of as an expanded version of Example 9 in Cohn 1988, rearranged as a voice-leading space.

Return to text

11. In slightly different terms, adjacent sets in the space are related by the “split transposition” T0/T+/-1 acting on the generating dyads of the set or set class. See O’Donnell 1997.

Return to text

12. Stravinsky’s sketch book initially referred to this scene as “Glorification—savage dance (Amazons).” See van den Toorn 1987, 24. Similarly, Stravinsky described the scene as a “martial dance”: “[The Chosen One] enters a stone labyrinth, and the other maidens celebrate her in a wild, martial dance.” Letter to N. F. Findeizen (December 15, 1912), cited in Stravinsky and Craft 1978, 92.

Return to text

13. Here is Stravinsky’s description of the scene from around the time of the work’s premiere: “The young girls dance about the Elect, a sort of glorification. Then comes the purification of the soil and the Evocation of the Ancestors. The Ancestors gather around the Elect, who begins the ‘Dance of Consecration.’ When she is on the point of falling exhausted, the Ancestors recognize it and glide toward her like rapacious monsters in order that she may not touch the ground; they pick her up and raise her toward heaven. The annual cycle of forces which are born again, and which fall again into the bosom of nature, is accomplished in its essential rhythms” (Stravinsky and Craft 1978, 525).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2022 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

24019