Injury, Affirmation, and the Disability Masquerade in Ye’s “Through the Wire”

Jeremy Tatar

KEYWORDS: Ye, hip hop, disability studies, masquerade, sampling, Chaka Khan

ABSTRACT: Ye’s song “Through the Wire” exists in two versions. The first was recorded in late 2002 after a near-fatal car crash and features Ye rapping through a jaw wired shut as he recovered from reconstructive surgery. After he healed, a second version was recorded in 2003 and released as the lead single from his debut album. Although Ye raps unimpeded in this later version, it was still marketed as the authentic product of physical disablement.

This study explores Ye’s performance of disability across these two versions of “Through the Wire,” focusing on his engagement with a phenomenon known as the masquerade. Adapted from queer and feminist studies to a disability context by Tobin Siebers, the masquerade encompasses a set of strategies for the public negotiation of disabled identities. Two prominent approaches involve 1) exaggerating a disability through a performative act of disclosure, and 2) disguising one disability behind another. I argue that Ye engages in both strategies throughout “Through the Wire,” and that attending to their roles in the song greatly nuances the straightforward narrative of overcoming that he otherwise projects.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.29.2.4

Copyright © 2023 Society for Music Theory

Preface (February 2023)

[0.1] In the time since I originally wrote this article and its submission, review, and eventual acceptance for publication, the public discourse around Ye (formerly known as Kanye West) has shifted substantially. Ye’s career has always been marked by a certain degree of controversy, but he has often received a pass on the basis of the transgressive, supposedly “genius” qualities of his musical persona. In the latter half of 2022, however, Ye’s public comments and behavior became increasingly saturated with dangerous antisemitic, anti-Black, racist, and sexually abusive rhetoric. The subsequent media attention to these issues has also unearthed—or drawn renewed attention to—earlier and sustained instances of this behavior over a larger period of time, and the specifics of these incidents are all easily retrievable online should one wish to inquire further. The situation is further complicated by Ye’s well-documented struggles with his mental health, particularly concerning a 2016 diagnosis with bipolar disorder. Although this is an important topic for consideration, it is not the primary focus of the text that follows. I want to state unequivocally, however, that I do not condone or endorse Ye’s actions in any way, and that a mental health disorder is no excuse for bigotry and should never be treated as such.

[0.2] Briefly, I hope to instead address an existential question: should this study be published at all? Many public commentators have suggested that Ye should be “cancelled” and that we should just collectively move on. The power of a celebrity, such as it is, largely rests on the amount of attention we pay to them. At the time of writing, several high-profile companies have terminated lucrative business relations with Ye, including the brands Gap and Adidas. Both Spotify and Apple Music have likewise removed playlists dedicated to his music (though not, for the most part, any of his music itself).

[0.3] In considering the stakes involved in a public divestment from Ye, my thoughts have been especially shaped by two pieces of writing by William Cheng. In his book Just Vibrations (2016), Cheng suggests that one possible approach to the issue of problematic artists might rest in a “reparative” attitude that is informed by the work of Eve Sedgwick (2003) and Suzanne Cusick (2008). As Cheng (2016, 99) writes, “reparative endeavors involve holding accountable those who voice prejudice, sow injury, and do wrong. But just as important is learning to acknowledge people as more than the sum of their worst deeds and words. Mercy is an essential option, for others’ sake as well as our own.” In opposition to the “paranoid” modes of thought and writing that otherwise pervade academic discourses, Cheng positions the reparative as an orientation that prioritizes “love, care, empathy, respect, and other glints of good” (102). Ellis Hanson (2011, 105) suggests an outlook that seems particularly appropriate for Ye: “a reparative reading focuses not on the exposure of political outrages that we already know about but rather on the process of reconstructing a sustainable life in their wake.”

[0.4] Is it possible—or productive, or desirable—to extend such a reparative perspective to Ye? I understand that this attitude might seem overly naïve to some readers, and it is difficult to imagine what it might mean to hold Ye accountable (within a field such as music theory, no less) for the tangible harm his words and actions continue to cause. Furthermore, as Cheng (2016, 100) points out, the optimism of a reparative position is often a luxury only made possible by the security of safe living circumstances and sociopolitical privilege. I am a cis man born, raised, and residing in the Global North and so have plenty of both, though I recognize that not all readers might share these advantages.

[0.5] A slightly different approach, then, is offered by Cheng in a 2019 piece that persuasively addresses the ethical and moral questions around consuming the work of what Claire Dederer (2017) has called “Monstrous Men.” Though Cheng supports strategies that boycott and divest from certain artists, he offers a counterargument to the idea that they should be cancelled outright. Engaging with the work of monstrous men, he argues, offers us opportunities for sustained reflection on our own vulnerabilities. Referring specifically to R. Kelly and Michael Jackson, Cheng writes that

I feel strange nowadays—unsettled, enticed, guilty, complicit—whenever I hear, say, “I Believe I Can Fly” or “Man in the Mirror” on the car radio or in a mall. The emotions are too messy. But that

. . . is exactly why I do choose to play such songs—now more than ever—for the college students in my music classes. To feel uncomfortable and trapped in a relationship with lovable music made by problematic musicians is not so different from feeling uncomfortable and trapped in a relationship with a problematic partner. Our vulnerability to charismatic music offers a key to understanding our vulnerability to charismatic people, institutions, and ideologies more broadly. (Cheng 2019, emphasis in original)

The metaphor that Cheng builds between music and a (romantic) partner finds parallels in Vivian Luong’s (2017) work on music loving, which is informed by Marion Guck (1996). Describing the historic squeamishness around identifying as a lover of music—especially among music theorists—Luong (2017, [1.5]) notes that “talking about music loving would force us to admit that we are not always in positions of power when we deal with music.”

[0.6] For my part, I believe that both the reparative position and the opportunity for discomfort in vulnerability are reasons to continue engaging with Ye, although I ultimately leave it to the reader as to whether they feel the same. Perhaps more importantly, we should recognize that these kinds of questions should be asked of all the art that we consume, regardless of whether this art is deemed problematic or not. The people we write about (talk about, teach about) matter, the ways in which we do so matter, and none of these are decisions that should be taken lightly; music, after all, is always more than just vibrations.

1. Background and Introduction

Audio Example 1. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002), Verse 2 (2:53–3:04)

[1.1] In October 2002, American hip-hop musician Ye was involved in a near-fatal car crash following a late-night recording session in Los Angeles. Ye’s injuries included three fractures to his jaw, which required reconstructive surgery and was subsequently wired shut as part of his rehabilitation. Upon his release from hospital some two weeks after the operation Ye recorded the song “Through the Wire,” in which he reflects on his career, the crash, his recovery, and the impacts of the event on his loved ones—all while his jaw was still wired fast to his skull. Rapped through clenched teeth with diction that is noticeably slurred and muffled, the mood and message of his song nonetheless celebrates conquest in the face of potential debilitation (Audio Example 1):

But I’m a champion so I turned tragedy into triumph

Make music that’s fire, spit my soul through the wire.

Example 1. Front and back covers of Ye’s mixtape, Get Well Soon

(click to enlarge)

[1.2] Structured around a sped-up sample of Chaka Khan’s “Through the Fire” (1985), Ye’s “Through the Wire” initially saw a limited release in December 2002 on his independent mixtape Get Well Soon

Example 2. Screenshots from the video clip for the 2003 version of “Through the Wire.”

(click to enlarge)

[1.3] Aurally, this later version walks a tightrope of ambiguous disability disclosure. Although the re-recording features significantly clearer vocals in the verses due to Ye’s unimpeded rapping, it still retains several spoken ad-libs from the earlier version that directly refer to his injuries. Example 2 captures six stills from this video, which features a montage of photographs and video footage as if they were polaroid images on a cork board. The scenes of Ye include footage of him at a dentist’s surgery, cash payments passed to a nurse since he was apparently without health insurance at the time, and various clips of him in the recording studio and around his hometown of Chicago. This re-recording effectively superseded the earlier version and received significantly larger public distribution. At the time of writing, some twenty years later, it remains the only version that is available for streaming on platforms such as Spotify and Apple Music. When necessary, I refer to the “2002” and “2003” versions of the song to differentiate these two recordings.

[1.4] The 2003 version of “Through the Wire” was hailed upon its release as “an innovative and intensely personal song that helped lay the foundation for his well-received debut” (Davis 2004, 92), and more recent assessments have further recognized its key role in establishing Ye’s early-career popularity. Andy Cush (2016), writing for SPIN magazine, calls Ye’s car crash and its commemoration in the song “a foundational element of his origin myth,” and Morgan Hunt (2017) in WIUX remarks that Ye’s recording of “Through the Wire” was “the moment that, retrospectively, defined his career.”(2) Through its lyrics, video clip, and promotional imagery, Ye’s body emerges as the central focus of “Through the Wire”—a body that is bruised, swollen, broken, and muffled, but also one that is proud, Black, and resilient. We hear this body viscerally with each slurred word and inhalation through gritted teeth, and the title card of the video clip (shown in Example 2) informs us that Ye “recorded this song with his mouth still wired shut… so the world could feel his pain!”(3)

[1.5] This article draws upon recent developments in cultural disability studies to explore the conception, recording, and reception of Ye’s “Through the Wire.” In particular, the 2003 re-recording suggests parallels with the disability masquerade (Siebers 2008), in which the by-then recovered rapper “crips up” for his performance of an impaired bodily state. By interpreting disability as a form of “performance” (Sandahl and Auslander 2005), I use the framework of the masquerade to analyze the bodily dynamics of Ye’s rapped delivery between the two versions. Furthermore, musical elements of the song itself can also be viewed through the lens of disability. Ye’s sampling of Chaka Khan significantly deforms her voice, invoking a physically non-normative body that offers a counterpart to his own physical impairment. As Chaka Khan’s supernaturally high tessitura is juxtaposed against Ye’s audibly irregular rapping, “Through the Wire” stages a cripped resistance to what Robert McRuer (2006, 35) calls the “compulsory able-bodiedness” of contemporary society. Although Ye appears to frame his encounter with disability as a straightforward narrative of heroic overcoming, one where disablement is a foil that he ultimately conquers, I argue that the functions of disability in “Through the Wire” and its accompanying imagery are significantly more nuanced. Recognizing and unpacking Ye’s participation in the masquerade helps reconcile aspects of his disability representation that might initially seem disingenuous, while also providing a useful context within which to situate other concerns of his early career.

[1.6] Section 2 of this article presents an overview of the existing scholarship on the relationships between hip hop and disability, examining how the presence of disability has been an important but largely overlooked feature of mainstream hip hop. Drawing particularly on the work of Laurie Stras (2006) and George McKay (2013), I further suggest how qualities of damage and impairment can be treated as positive and even desired attributes in hip-hop culture, a factor that greatly contributed to the success of Ye’s song. In Section 3, I focus on two manifestations of the disability masquerade in “Through the Wire.” The masquerade is related to strategies of passing employed by queer and other minoritized groups and involves a public negotiation of a disability identity that deliberately obscures its dimensions.(4) As Tobin Siebers (2008, 100) writes, the masquerade occurs when people with disabilities “disguise one kind of disability with another or display their disability by exaggerating it.” Reflecting on his own public performances of disability to illustrate the masquerade’s malleability, Siebers recalls both using a different injury—a broken knee—as a disguise for the leg also affected by post-polio syndrome, as well as exaggerating his limp when boarding planes to avoid confrontations with check-in personnel about a mobility impairment insufficiently marked without a wheelchair. Following Siebers, I will refer to these two tactics as a “disguised” and “exaggerated” masquerade, respectively.

[1.7] In Ye’s case, I first explore the relationship between Siebers’s “exaggerated” disability identity and the 2003 re-recording of “Through the Wire,” and consider whether this later version of the song should be interpreted as a form of “cripface” (2019, 91). Since this re-recording is effectively the performance of a disabled body by one that has subsequently healed, I compare Ye’s song with the longstanding Hollywood practice of casting nondisabled actors for the roles of disabled characters.(5) If the audible presence of the wires in Ye’s mouth is what makes “Through the Wire” so compelling in its original form, does the nondisabled re-recording undermine the credibility of the song itself? Second, I suggest that Siebers’s theory of a “disguised” disability identity emerges when Ye’s crash and subsequent impairment are viewed in dialogue with his reputation as a rapper with a limited technical ability, something that proved to be a major obstacle in his early career. For close to five years, he struggled to gain recognition as a legitimate rapper and was considered by many in the recording industry to be “wack”—as in weak, weird, unconventional, and, perhaps most importantly, unprofitable. Just as Siebers uses an injury to deflect questions about his post-polio-afflicted leg, I argue that in “Through the Wire” Ye used the crash as something of a cover: it offered a pass for his perceived lack of rapping ability, where the sheer feat of recording the song eclipsed any of his other shortcomings. Examining Ye’s lyrics from the song, as well as from other tracks on The College Dropout such as “Last Call,” demonstrates that he believed overcoming his physical debilitation via “Through the Wire” to also represent overcoming his critics and doubters. To close, the final section will consider Ye’s sampling of Chaka Khan’s “Through the Fire” from a crip perspective and investigate the interactions between the two voices—both of which are non-normative—within the song. Exemplary of the “chipmunk soul” movement in hip hop that flourished in the early 2000s, the sample of Chaka Khan’s voice is sped up by about 28% (from an original 66bpm to 84bpm in Ye’s song) and pitched up by four semitones, eventually reaching a stratospheric C6 at its melodic peak. Chaka Khan’s voice and body are rendered cartoonish and artificial by this process, in turn drawing attention to Ye’s own physical presence. Finally, this speeding-up affords the slippage in Chaka Khan’s sung lyrics from “through the fire” to create Ye’s hook “through the wire” in a deft moment of aural misprision and playful signifyin’ characteristic of Black expressive cultures (Gates 1988).

2. Hip Hop and Disability: Damage as Value

[2.1] Disability and hip hop might initially seem an odd intersection, yet closer inspection reveals many qualities in common. Consider, first, their intimate relationships with minoritized identity categories, whose members face stigmatization, segregation, and discipline for apparent societal disobediences. Just as disabled bodies are scrutinized according to their deviances from the normal—too short, too slow, too weak, too ugly(6)—the Black bodies of hip hop “are similarly scrutinized against norms of whiteness” (Adelman 2005). Disabled populations such as those represented by d/Deaf communities have long been the targets of eugenicist anxieties (Davis 2013), a situation that is mirrored in the racialized anxieties around popular music that have shaped much of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The hip-hop group Public Enemy, for instance, didn’t title their 1990 album Fear of a Black Planet for nothing. Furthermore, both disability studies and hip hop can be understood as outgrowths of activism, as tools for social change fighting against discrimination and disenfranchisement; they are both “meaningfully embodied counterdiscourses” (Adelman 2005). And the two also find joint histories in the freak and minstrel shows of the nineteenth century, highly influential forms of popular entertainment whose casts of stock characters (the bearded lady, the racialized “primitive,” Jumping Jim Crow, the Zip Coon, and so on) are still echoed in today’s stereotypes and prejudices (Morrison 2019).(7) Within both disability and hip hop, in short, we find countless examples of the “physically extraordinary figure” that is “essential to the cultural product of American self-making” (Garland-Thomson 2017, 5).

[2.2] Alex Porco (2014) surveys manifestations of disability in several hip-hop artists, uncovering a widespread presence that has nonetheless remained largely unacknowledged. Disabilities have shaped the lives and music of these musicians in numerous ways, and Porco connects the distinctive voices of rappers Fat Joe, Raekwon, Guru, and Coolio with their chronic asthma, as well as Biz Markie, Kool G Rap, Biggie Smalls, Cappadonna, Cormega, and Mos Def with their lisps. MF Grimm and 50 Cent suffered physical debilitation following gunshot injuries, and the obesity of Big Pun, who was close to 700 pounds when he died of a heart attack in 2000, affected his mobility as well. Ghostface Killah of the Wu-Tang Clan is diabetic, and Phife Dawg of A Tribe Called Quest died at age 45 from diabetes-related complications in 2016. To Porco’s examples, I add J Dilla, who died in 2006 (aged 32) from the blood disease thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and performed from a wheelchair toward the end of his career; Bushwick Bill, whose dwarfism resulted from achondroplasia (Hinton 2017, 301); Fetty Wap, who had one eye surgically removed as a child due to congenital glaucoma; producer Noah “40” Shebib, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2005; Scroobius Pip, who stutters (McKay 2013, 84); Lil Wayne, who is epileptic; and Prodigy, who had sickle-cell anemia (Breihan 2007). Many of these conditions—such as diabetes, obesity, asthma, and sickle-cell anemia—are disproportionately present in Black and other marginalized communities, suggesting that there are also racialized and systemic inequities that contribute to their prevalence.

[2.3] More broadly, the stage names of hip-hop artists often engage with ideas of bodily norms and deviances. Given the ubiquity of the qualifiers Big and Lil’ (Boi, Daddy Kane, Gipp, K.R.I.T., Noyd, Pokey, Pun, and Sean in the former; B, Jon, Kim, Nas X, Reese, Uzi Vert, Wayne, and Yachty in the latter, among many others), we might well consider: big or lil’ compared to whom? A growing body of literature has focused on the practices of d/Deaf rappers (e.g., French 2016; Holmes 2017; Maler 2015; Maler and Komaniecki 2021), and Porco’s work suggests that the other, more concealed presences of disability in the lives of hip-hop musicians remain rich sites for future excavation. And considering that Black Americans are statistically more likely to experience disabilities than other racial and ethnic groups, the foregoing survey is undoubtedly only a very small glimpse of a much larger picture.(8)

[2.4] Aside from these examples of disabilities in the lived experiences of hip-hop musicians, metaphors of disability are also found throughout the music’s vernacular, where they often signify freedom, liberation, and abandon (Bailey 2011). Through this valorization of the non-normative emerges what Siebers (2010) has called a “disability aesthetic,” a disruption of the traditional markers of health, beauty, or wholeness. The word “ill” appears frequently in hip-hop culture, for example, as in the albums Licensed to Ill (1986) and Ill Communication (1994) by the Beastie Boys, throughout Nas’s 1994 debut Illmatic, or in the song “The Illest Villains” (2004) by the duo Madvillain. In Ye’s song “N—as in Paris” (2011) with Jay-Z, he raps: “Doctors say I’m the illest / ‘Cause I’m suffering from realness / Got my n—as in Paris / And they goin’ gorillas.”(9) The use of “freak” is also widespread in song titles and generally celebrated as a positive attribute: Missy Elliot’s “Get Ur Freak On” (2001), Beyoncé’s “Freakum Dress” (2006), Future’s “Freak Hoe” (2015), Megan Thee Stallion’s “Big Ole Freak” (2019) and “Freak” (2020), and Mos Def’s “Freaky Black” (2004). Krayzie Bone is part of the group Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, YG released My Krazy Life in 2014, and Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy” (2006) was rated by the publication Rolling Stone as the best song of the 2000–09 decade. Quasimoto (a reference to Victor Hugo’s hunchback) is a side-project of the producer Madlib, and MF DOOM conceals his face behind a metal mask.(10) Cyprus Hill are “Insane in the Brain” (1993), Future is “Codeine Crazy” (2014), Lil’ Durk is “[Ye] Krazy” (2021), Ne-Yo is “So Sick” (2005), Young Thug is a “Beast” (2015), and Missy Elliott tells us to “Lose Control” (2005) while LL Cool J attempts to “Control Myself” (2006). In extraordinarily poor taste, the Black Eyed Peas sing “Let’s Get Re—ded” on their 2003 album Elephunk, which was minimally altered to “Let’s Get it Started” for its release as a single. “Let’s Get it Started” would go on to win the Grammy for “Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group” in 2004, along with a nomination for “Record of the Year.”

[2.5] The prevalence of these references, along with their almost universally positive valence, suggests that hip hop claims disability as a desirable quality.(11) Or, at the very least, embraces certain kinds of it. But while this acceptance of disability and disabling metaphors might charitably be read as inclusive or empowering, we cannot forget hip hop’s parallel role in propagating harmful and discriminatory structures such as misogyny, homophobia, and racism. There is also an ongoing tension between hip hop’s prominent “disability aesthetic,” on the one hand, and a kind of covert ableism on the other, which is particularly evident when considering its stigmatization of mental health issues. Kid Cudi’s entry into rehab for “depression and suicidal urges” (Setaro 2016) was openly mocked by Drake in “Two Birds, One Stone” (2016); Troy Ave’s song “Badass” (2016) jokes about the suicide of rival rapper Capital Steez; and J. Cole uses autism as a punchline in his verse on Drake’s “Jodeci Freestyle” (2013).(12) So while in certain circumstances, hip-hop musicians might take performative ownership of being “crazy,” “sick,” “ill,” “mad,” a “freak,” “wild,” “out of control,” or even “re—ded,” in different contexts they might mock the neurodiversities of other rappers. As hip hop continues its growth at the center of popular consciousness (Ta-Nehisi Coates [2009] describes its shift in the late 1990s “from American cult music to American pop music”), critiquing and opposing its perpetuation of toxic attitudes will become an increasingly urgent task for disability advocates. Projects such as Leroy Moore’s Krip-Hop Nation (https://kriphopnation.com), for example, are committed to dismantling ableist structures within hip-hop discourse, although much work remains to be done.

[2.6] Ideas of disability find a different manifestation in hip-hop culture if considered in terms of the kinds of vocal damage that might signal authenticity or “realness.” It is from this perspective that we can better understand the positive reaction to Ye’s “Through the Wire” and its continued popularity throughout his career. A 2004 review of The College Dropout for the online publication PopMatters, for example, affirms that the song “is as riveting and moving as everyone says it is” (Heaton 2004). In her essay “The Organ of the Soul: Voice, Damage, and Affect,” Laurie Stras suggests that the kinds of vocal damage potentially indexical of disability in other situations can achieve a desired status within the value systems of popular music:

The damaged voice continues to be accepted, even preferred, in many genres within popular music, to the point of optimum levels of damage appearing suitable for different types of singing: the gravel-voice of the rock singer is not interchangeable with the subtle hoarseness of the jazz vocalist. Many singers have learned to simulate or manipulate damage in the voice, so further revealing the affective value of the sound; and in a reversal of what might be considered normate associations, damage here seems to be linked with concepts of authority, authenticity, and integrity. (Stras 2006, 174)(13)

While hip hop is not explicitly addressed in Stras’s account, such ideas clearly resonate with what rapper 50 Cent (who was shot nine times in 2000) describes as “the damage” in a 2020 interview with the Guardian:

In hip-hop, people are looking for the damage. And you come in and they look at you, and they can see the damage. They can see the experience, the story, why you are where you are. You can offer something unique. (Hattenstone 2020)

Stras’s work argues that this damage might find outward expression through the qualities of the voice itself, which “conveys meaning even before it conveys language” (173). This pre-verbal meaning, in turn, imparts a greater sense of authenticity to a performance. The drug-dealing, street-hardened gangster persona of 50 Cent is therefore made more credible, more “real,” if we can hear the traces of his lived experiences within his voice. In Ye’s case, “Through the Wire” invites listeners into his rehabilitation, where we can hear the bodily pain communicated through his voice, rather than merely imagining it through his lyrics (Porco 2014). We are offered, in other words, the aural equivalent of that old writer’s maxim: “show don’t tell.”

[2.7] By experiencing Ye’s pain firsthand through the aural trace of his vocal damage, and by further gaining greater appreciation of his mental and physical determination in the act of recording “Through the Wire,” we are prompted to view him through a rhetorical mode that Rosemarie Garland-Thomson (2002, 59) calls “the wondrous,” which “capitalizes on physical differences in order to elicit amazement and admiration.” Comparing Ye's performance with the clumsiness we would experience trying to speak a sentence through clenched teeth—let alone the 600-odd words that constitute “Through the Wire”—makes his feat seem truly superhuman. This “wondrous” mode of disability representation also includes narratives of inspiration and even adulation, which are characteristic of the rhetorical shift in depictions of disability following the disability rights movements of the 1960s and 70s (Garland-Thomson 2002, 62). This framework of wonderment then helps situate reflections such as the following from MTV journalist Rahman Dukes, who eventually finds inspiration in “Through the Wire” despite initial misgivings about its video clip:

On my way out the door, I thought to myself, “Was that video a little too over the top? Is he capitalizing too much off his accident? Be thankful you’re here.”

Not even two days later, I found myself in a position similar to his. The day after the 4th of July, I was hospitalized for two weeks after surviving a near-fatal car accident. After months of rehabilitation, I finally returned to MTV.

One of the first projects that came across my plate was covering a [Ye] video shoot out in Brooklyn. The troops and I made our way out to the video set, and as soon as we walked in the door, there stood [Ye] in the back with his friends. He came over to say waddup, and while attempting to shake my hand, [Ye] realized a cast was on my arm. “What happened?” he asked me. I informed him of the accident and saw the concern in his face. To make the convo a little more positive, I told him that at first I had my doubts about his “Through the Wire” video until it came on while I was on a visit with my cousin, who was also injured in the accident. “Look at him,” I told my cousin, pointing to the monitor. “He went through it and made it out stronger. And so will we.” (Dukes 2008)

Audio Example 2. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002), Verse 1 (0:32–0:49)

[2.8] George McKay’s (2013, 71) work expands on Stras’s to consider the “other ways in which disabled singers have used their voices to sound their embodied difference.” Rather than the involuntary markers of vocal damage surveyed by Stras, however, McKay focuses on the deliberate articulations of disability in popular music (primarily in British and American rock-and-roll from the 1950s onward) and the different ways that their affective potential can be deployed. In this category we find screams, stutters, falsetto, stage banter, and even code-switching accents, which together mark “a continuity between the peculiar sounds of the voice and the peculiarities of the singer’s disabled body or mind, and his or her

I drink a Boost for breakfast, an Ensure for dessert

Somebody ordered pancakes, I just sip the sizzurp

That right there could drive a sane man berserk

Not to worry, Mr. H-to-the-Izzo’s back to wizzerk(15)

Audio Example 3. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002), Ad-lib 3 (2:59–3:21)

Though Ye’s vocal dexterity is hampered by his physical impairment, it also allows a greater sense of play and freedom in his verbal articulation. And just as performers such as Mel Tillis and Ian Drury mined the comedic possibilities of the stutter (McKay 2013, 80–83), Ye turns the wires in his mouth into a joke about his penchant for jewelry—a coded flex of his wealth—in a spoken ad-lib over the song’s outro (Audio Example 3):

Y’know what I’m sayin’?

When the doctor told me I had to, um

That I was gonna have to have a plate in my chin, I said

“Dawg, don’t you realize I’ll never make it on a plane now?

It’s bad enough I got all this jewelry on!”

You can’t be serious, man. . . (16)

[2.9] Stras’s and McKay’s theorizing of the acceptance (and even preference) of certain kinds of vocal damage raises a difficult question: does spectacle supersede substance? Stras offers the example of Julie Andrews, whose voice was permanently damaged by surgical complications following the removal of a vocal nodule. When Andrews attempted to sing a few measures of “Singing in the Rain” at an AIDS benefit in 2000, “the audience gave her a standing ovation, perhaps moved by the quality of her voice, but certainly moved by what they saw as her courage in the face of suffering” (Stras 2006, 181; emphasis mine). Likewise, Stras describes listening to a 1964 performance of “Over the Rainbow” by Judy Garland as “a painful experience. The voice cracks, wavers, and fails in both tone and pitch; the song is sung more or less at full belt all the way through, as there is no appreciable dynamic range left to exploit” (181). And yet, the performance received rapturous applause from its attendees and was considered by one audience member to be “the most moving thing she felt she had ever heard” (181–2). As I describe in more detail below, Ye’s rapping abilities in the early 2000s were broadly considered inferior to his skills as a beat producer, and Porco particularly notes that his vocal performance in “Through the Wire” exhibits “a lack of expressive range in terms of pitch, articulation, accent, and speed” (2014). To use a similar distinction that Stras employed for Julie Andrews, positive reactions to Ye’s “Through the Wire” were perhaps responding to the musicianship of his performance but were certainly moved by the story behind it.

[2.10] In any case, Ye appeared deeply aware of the pathos of his circumstances, which he leveraged to his advantage during the song’s promotion. In an interview two weeks before the release of The College Dropout, he spoke candidly about the positive reception of “Through the Wire,” which had been released as a single in advance of the album:

But I have to just thank God for the situation that I am in, you know. It’s like, you turn the worst thing into the best thing. “Through the Wire” is the worst thing that could’ve possibly happened to me, and now it’s obviously the best thing. Look how it exploded! And it made people care. And it made people realize that I was a human being.

I recorded the song two weeks later, with my mouth still wired shut. I felt like even if the song didn’t blow up, that once other songs did blow up—which I knew they would—people would just look back and say, “Man, do you remember his first song? He recorded it with his mouth wired shut! He’s crazy!” (Johnson 2004)(17)

Similarly, in another interview with the magazine Ebony:

I feel like the album was my medicine

. . . . It would take my mind away from the pain—away from the dental appointments, from my teeth killing me, from my mouth being wired shut, from the fact that I looked like I just fought Mike Tyson. . . The record wouldn’t have been as big without the accident. . . I nearly died. That’s the best thing that can happen to a rapper. (Davis 2005, 160)

[2.11] It is here that Ye is closest to claiming disability as a positive identity, and to recognizing the potential benefits of bodily difference. But there is also a certain naïveté to his comic narrative of “the worst thing” turning out to be “obviously the best thing”—how many of the other approximately 2.5 million Americans injured every year in traffic accidents are able to say the same?(18) In a survey of autobiographical accounts of breast cancer, Thomas Couser (1997, 40) notes that the very nature of these authors’ recoveries means that their first-person retrospectives “may be a misrepresentation of the disease.” Couser writes that “because breast cancer is rarely considered cured—because having ‘had’ cancer almost always means being susceptible to recurrence, being constantly vigilant—the retrospective closed-end autobiographical narrative is always somehow false to the experience” (41). Ye’s case is somewhat different, given the minimal threat of a relapse to his former condition, but the possibility that his comic narrative of overcoming is a misrepresentation of violent automobile trauma remains worth scrutinizing.(19)

[2.12] Finally, Stras’s ontology of vocal damage helps answer an important methodological question: is Ye’s temporary physical debilitation resulting from his car crash really a disability? Is it analogous to being deaf or blind, to having autism, or to being an amputee? Stras’s work, which draws heavily on the context-specific principles of the social model of disability, suggests that the answer would be “yes.” In opposition to the frequently essentialist nature of the medical model of disability—which “defines disability as a pathology or defect that resides inside an individual body or mind” (Straus 2011, 6)—Stras argues that disability is better understood as

the result of social barriers or restrictions experienced by the impaired person

. . . . So, in the case of the voice, the significance of vocal disruption or damage to an individual will be in proportion to his or her reliance on vocal function for daily activity, and the more significant it is, the more disabled that person may be seen to be. (Stras 2006, 174)(20)

Vocal hoarseness, for example, is not an objectively disabling condition, but it can be increasingly regarded as such if the person it afflicts relies on vocal clarity for their day-to-day functioning. Stras recounts her own experiences willfully damaging her voice pursuing the appropriately breathy timbre of a nightclub singer, remarking that she now has “slight, but permanent, vocal damage—damage that does not prevent me from doing anything (except, perhaps, resuming a career I understood I was physically unsuited to, anyway), but damage nonetheless” (175; emphasis mine). The porous boundary between disability and impairment is highlighted by this reflection, since Stras’s vocal damage poses little disabling threat to her daily life but would become immediately apparent in certain musical situations. Joseph Straus (2011, 126) suggests a similar category of “bodily differences that become disabilities only in a musical context,” and points to the focal dystonia (uncontrollable muscle contractions) that affected the pianists Leon Fleischer and Gary Graffman. This contextual understanding of disability for Ye’s situation helps clarify that while a wired-shut jaw would not be disabling for everybody, for an aspiring rapper at a pivotal moment in his career it is a significant disability indeed. Such a perspective also allows “injury” and “disability” to find greater common ground, and further reminds us that the (usually) temporary nature of an injury does not necessarily make it any less disabling.

3. Exaggeration and Disguise: The Disability Masquerade

[3.1] This section focuses on the masquerade, which was adapted to a disability context from its origins in queer and feminist theory by Siebers (2008). The masquerade engages with similar negotiations of identity and power relations as the more familiar practice of “passing”—broadly understood as “a form of imposture in which members of a marginalized group present

[3.2] In a disability studies context, the masquerade involves “claim[ing] disability as a version of itself rather than simply concealing it from view” (Siebers 2008, 101). Siebers suggests two ways that this embrace of “disability as a version of itself” might be realized: 1) a disability may be exaggerated in an almost performative act of disclosure; or 2) one kind of disability may be disguised behind another. Despite the apparent contradiction between these two strategies—between exaggeration and disguise—understanding them as both belonging to the broader practice of the masquerade helps emphasize their structural similarities and their shared engagement with issues of agency and self-representation. Petra Kuppers offers an example of this performative exaggeration of disability, set evocatively in the second person:

Your social worker comes for her annual visit, and you crip up: your limp is more pronounced as you open the door for her, you are not even thinking about it, but you somehow seem to modulate how you reach across the table when you sit down to review your service hours. (Kuppers 2015, 137)

Likewise, Siebers recounts the experiences of the artist Joseph Grigely, who had an altercation with a security guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that perhaps could have been avoided were his deafness better marked. After the guard physically strikes and verbally reprimands him, Grigely wonders, “Perhaps I need a hearing aid, not a flesh-colored one but a red one” (Grigely quoted in Siebers 2008, 102).

[3.3] The second variation of the masquerade, where one disability is concealed behind another, is explored by Isaac Stein (2010). After breaking his thumb playing football, Stein finds himself with a bright blue cast on his right hand, assured by doctors that it would make his thumb “as good as new.” The twist, however, is that the right side of Stein’s body is affected by a form of cerebral palsy that significantly reduces the sensations and fine-motor skills of his hand. By masquerading behind the temporary plaster cast (with its own paradoxically sporty signification of able-bodiedness), Stein then finds social acceptance for a thumb that was previously stigmatized for its impairment:

Quite literally overnight, it seemed as though all the confusion, uncertainty and social awkwardness I deal with around my right arm on a daily basis had disappeared. When I was introduced to people, nobody extended their right hand to shake mine and was discombobulated when I responded with my left. Everybody knew that my right hand was off-limits as a shaker (and shakee) without my having to say anything, and nobody had any issue with it! I could barely conceal my delight at this sudden but profound alteration in my daily social interactions. This change alone almost made me feel like keeping the cast on permanently. . . .

The smiles, the shared stories, the left hands extended to shake, the acknowledgements of my injury without hesitation or uncertain pauses—all of these are examples of how my arm was now being done as a socially legitimate impairment by the people around me. The contrast with my typical social experiences around my right arm couldn’t have been more stark. By breaking my thumb, I’d finally made my right arm ‘normal.’ (Stein 2010)

The irony of the situation deepens when Stein points out that there was almost no change in the day-to-day functionality of his palsied hand post-accident; what had changed, rather, was the way that it was perceived by others. Stein’s masquerade reveals the complexity of “claiming disability as a version of itself,” where repackaging a bodily impairment as a sporting injury (rather than a result of cerebral palsy) potentially lets him pass as able-bodied.

[3.4] The exaggerated masquerade is a useful lens through which to examine Ye’s 2003 re-recording of “Through the Wire.” Audiences encountering this version receive numerous prompts concerning his physical condition and are led to believe that the entire song was recorded while his jaw was wired shut. But a problematic disjunction emerges between the song’s explicit packaging as a product of Ye’s facial injuries and the largely unacknowledged reality that his verses were re-recorded almost an entire year after his accident, long after the eponymous wires were removed from his mouth. He appears to be playing disabled from a nondisabled body, in other words, with at best opaque disclosure of this slippage. When considered instead as the “performative exaggeration” version of the disability masquerade, however, his apparently deceptive actions seem less egregious. The masquerade emphasizes the performed and unstable nature of disability, and helps us examine the complex entanglement of illness, recovery, and the legibility of impairments. If we adopt a position akin to Couser (1997) in his examination of illness narratives, we might better understand Ye’s song along similar lines to that of a memoirist recounting the moment of a cancer diagnosis from a time some five years since recovery, or as an instance of autism life-writing that was composed predominantly on the “good days.” Recovery does not mitigate or invalidate the experiences that necessitated it.

Example 3. Formal outline of “Through the Wire.”

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] I will now use this frame of the “exaggerated” masquerade to compare the 2003 re-recording of “Through the Wire” with the 2002 version originally released on Get Well Soon

Audio Example 4. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002), Ad-lib 2 (1:21–1:51)

[3.6] Ye’s vocal quality in these spoken ad-libs is muffled, and in the second of the three he directly acknowledges that his mouth is wired shut (Audio Example 4):

I really apologize for everything right now

If it’s unclear at all, man

They got my mouth wired shut

For like. . . I dunno, the doctor said like six weeks

Y’know, he had reconstruc-, I had reconstructive surgery on my jaw

I looked in the mirror

And half my jaw was in the back of my mouth, man

I couldn’t believe it

But I’m still here for y’all right now, man

This what I got to say right here, dawg

Yeah, turn me up, yeah, uh

This ad-lib makes sense in the context of the original, 2002 version, since Ye’s rapped delivery in the preceding verse is indeed somewhat slurred. Yet in the later version, with its newly recorded and cleaner vocal take, its inclusion is more puzzling. The third ad-lib in the song, which was featured in Audio Example 3 previously, also directly addresses Ye’s impaired condition. In the context of the 2003 version of “Through the Wire,” if his verses were not recorded through clenched teeth, they why insert ad-libs that proclaim that they were? I argue that this stems from a deliberate decision on Ye’s part to “play up” the drama of the song and its backstory, and thus better engage in the commodification of damage described earlier. As the lead single for his debut album, “Through the Wire” is simply a more compelling narrative if audiences are encouraged to understand that the wires Ye describes are present throughout the entire song, even if they are only actually there in the ad-libs. By exaggerating the scope of his disablement, Ye participates in the same form of the disability masquerade as playing up a limp at the airport.

[3.7] Aspects of the music video for the 2003 version of “Through the Wire” also reinforce this narrative of impairment. As mentioned above, the title card states that “Last October grammy nominated producer [YE] was in a nearly fatal car accident. His jaw was fractured in three places. Two weeks later he recorded this song with his mouth still wired shut

Audio Example 5. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002), Verse 1 (0:45–1:24); followed by Ye, “Through the Wire” (2003), Verse 1 (0:45–1:24)

Audio Example 6. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002), Verse 1 (1:08–1:15); followed by Ye, “Through the Wire” (2003), Verse 1 (1:08–1:15)

Audio Example 7. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002),Verse 1 (0:50–0:58); followed by Ye, “Through the Wire” (2003), Verse 1 (0:50–0:58)

Example 4. Lyrics of the first verse as excerpted in Audio Example 5, with changes between the two versions marked in bold

(click to enlarge)

[3.8] This claim is undercut, however, when one considers the 2002 and 2003 versions of the song side-by-side. Audio Example 5 compares the first verse from each of the two versions to highlight the differences between Ye’s respective performances. The audio excerpt begins with the original mix on Get Well Soon

[3.9] I now return to the question posed earlier: should the 2003 re-recording of “Through the Wire” be considered as “cripface,” also known as disability drag?(21) The classic example is Dustin Hoffman’s Academy Award-winning portrayal of autistic savant Raymond Babbitt in Rain Man (1988); Dustin Hoffman is not an autistic savant, and so plays disabled from a position of able-bodiedness. This practice has been criticized on numerous fronts from disability activists. One argument could be summarized through the popular disability rights slogan “nothing about us without us,” which advocates for genuine self-representation for and by people with disabilities. Disabled characters, in other words, should be played by disabled actors. A related critique focuses on the narratives that surround disability representations in media, especially in situations where only non-disabled people are involved in their production. In such cases, disability often becomes a plot device: disabled characters function primarily to develop the lives of other characters while otherwise remaining unchanged themselves (consider, again, the respective arcs of the characters portrayed by Hoffman and Tom Cruise in Rain Man), or else a disability is something to be overcome or even cured over the course of narrative. Both instances reify an ableist gaze.(22)

[3.10] Are there structural similarities here with Ye performing disability from a body that has subsequently healed? Yes and no. Ye’s claims toward authentic bodily impairment represented by the video clip’s title slide and the second ad-lib, in particular, are problematic bordering on outright deceptive, though charging him with cripface overlooks the deeply performative acts that constitute the identities of people who live with disabilities. Building on the work of Erving Goffman and Judith Butler, Carrie Sandahl and Philip Auslander (2005, 2) write in the introduction to their collection Bodies in Commotion that “the notion that disability is a kind of performance is to people with disabilities not a theoretical abstraction, but lived experience.” As well as the kinds of unconscious identity performances described in Butler’s work, the performances of people with disabilities are often mindful, deliberate, and pre-meditated: they are very much “onstage” anytime they are in public.(23) When considered along these lines, Ye’s 2003 re-recording participates in the same system of curated identity that Siebers (2008, 96) invokes when he admits to “keeping secrets and telling lies.” The cripface charge also misses other factors that might influence an individual’s decision to masquerade, ranging from commercial (the story behind Ye’s song greatly contributed to its success, and more legible records are easier to sing along with and ultimately purchase) to personal (masquerading, like passing, might assist in therapeutic constructions of selfhood through boundary testing). Without downplaying the issues of the 2003 version of “Through the Wire,” understanding it within the context of the masquerade helps foreground the performative aspects of a lived disability identity.

[3.11] Moving now to the dimension of the masquerade that involves disguising one disability with another, I argue that Ye used the physical debilitation following his car crash to conceal, or at least mitigate, his perceived limitations as a rapper. To begin, it is worthwhile reviewing the definition of “disability” as it appears in the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (under Section 3, Definitions):

The term “disability” means, with respect to an individual— (A) a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities of such individual; (B) a record of such an impairment; or (C) being regarded as having such an impairment.(24)

My focus here is primarily on the third axis of this definition, “being regarded as having such an impairment,” especially to the extent that it relates to appraisals of Ye’s abilities. While it is possible to quantify a rapper’s flow by examining features such as their average rate of syllabic delivery, number of syllables per word, number of rhyme instances, relative saturation of metric space, diversity of vocabulary, and so on, and thereby establish certain measures of their aptitude (see Ohriner 2019 for one such methodology), I am substantially more interested in the ways in which the perception of Ye’s weaknesses as an MC might itself be understood as disabling for him, especially in terms of the social model of disability described by Stras above.

Audio Example 8. Ye, “Last Call” (2003), Verse 2 (2:27–2:42)

[3.12] Ye’s early career was marked by some successes as a beat-maker, where he produced hit songs for artists such as Jay-Z and Alicia Keys. Yet he also harbored ambitions as an MC that garnered minimal industry interest. Hindered by the widespread perception among label representatives that he lacked sufficient abilities as a lyricist and performer, as well as other concerns about his “clean-cut and seemingly soft image” (Bailey 2014, xviii), Ye struggled for close to five years to secure a recording contract. He references this situation several times on The College Dropout, and his bitterness is perhaps most evident on the album’s closing track, “Last Call.” A rambling, thirteen-minute toast to his career, the song is split into two parts: the first four minutes unfold in a conventional verse-chorus structure before Ye then gives an extended autobiographical monologue as the beat continues to loop. The song’s second verse contains the following lines (Audio Example 8):

Some say he arrogant, can y’all blame him?

It was straight embarrassing how y’all played him

Last year shoppin’ my demo, I was tryin’ to shine

Every motherfucker told me that I couldn’t rhyme

As corroborated by footage from the 2022 Netflix documentary jeen-yuhs: A [Ye] Trilogy, Ye was greeted with awkward bemusement and indifference when he performed his song “All Falls Down” in the New York offices of Roc-A-Fella Records in 2002. Other scenes in jeen-yuhs capture his frustrated attempts to gain respect as a rapper, and as he relates in one conversation: “People used to tell me not to rap. Now if I don’t got the best voice and I don’t have this hard image, or I don’t have a jail record, or whatever. So people are saying these are the reasons why I can’t rap.” In another scene, Ye expresses his excitement after securing an interview on the MTV series “You Hear it First,” through which he might greatly expand his audience. “They’re gonna do a ‘You Hear it First’ on your boy,” he says, before breaking into a tongue-in-cheek semi-rap: “wack-ass me / can’t rap-ass me / so stick to track-ass me.”(25) Talib Kweli, an early collaborator, similarly recounts that

nobody was taking [Ye] seriously. He wanted to be on Rawkus [Records] and Rawkus were like “nah we want his beats.” Everybody was trying to figure out a way to get [Ye] to give up his beats, without wanting to hear him rap.(26)

The recollections of John Legend, another early collaborator, are much the same:

Dame Dash and Roc-A-Fella signed him but I don’t think they really took him seriously. They just signed him because he was such an important producer for them and they wanted to keep him in-house

. . . . I was there during the early time when he was just developing a lot of the material. When I first started working with him, I honestly didn’t think his album would be special. As a rapper, he wasn’t that great. (Ahmed 2014)

Audio Example 9. Ye, “Last Call” (2003), Verse 1 (1:24–1:36)

[3.13] Ye was eventually able to sign a recording contract with Roc-A-Fella Records, though it was only after the successful release of “Through the Wire” as a single that the label would commit to a release date for his album The College Dropout. In addition to the commodification of “damage” described above, I believe that his crash and “Through the Wire” also gave him the opportunity to disguise any technical shortcomings behind his physical circumstances. Recall, for example, Porco’s (2014) description of Ye’s vocal performance in “Through the Wire” as lacking “expressive range in terms of pitch, articulation, accent, and speed.” But do these deficiencies stem from his physical impairment, or are they really just qualities of his flow itself? The masquerade of disguise means that it is impossible to answer this question, and this is precisely the point. The accident transformed the perception of Ye’s abilities—apparently unexceptional up to that point—and rendered his performance through clenched teeth “wondrous” (to use Garland-Thomson’s term). As he raps in the closing couplet of his first verse in “Last Call” (Audio Example 9):

It’s funny how wasn’t nobody interested

‘til the night I almost killed myself in Lexus.

[3.14] Stein’s masquerade with his plaster cast—and his musings about keeping it on permanently—offers another point of comparison here, since it reveals the fundamentally finite powers of this mode of disability performance. Stein’s cast must eventually be removed, returning his arm to its “regular” palsied state. Ye’s jaws, likewise, would eventually heal, and the apparent pass offered by his physical incapacitation would then expire. Given the issues that Ye had with his perceived abilities as a rapper before his mainstream debut, it is therefore notable that assessments critical of his flow also regularly featured in reviews of his early major-label releases. In their reviews of The College Dropout, Michael Endelman (2004), for example, notes in Entertainment Weekly that Ye possesses “a clunky flow and an off-key warble,” while Jon Caramanica (2004) writes that Ye “isn’t quite MC enough to hold down the entire disc,” pointing to the large number of guest artists who fill out its verses. In his review for Pitchfork, Rob Mitchum (2004) argues that Ye hides “his occasional technical shortcomings with his gift for comedic timing,” a description that Sasha Frere-Jones (2005) later echoes in The New Yorker: “[Ye] is a relentlessly clever, funny thinker

Audio Example 10. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002), Ad-lib 1 (0:00–0:08)

[3.15] “Through the Wire” therefore served something of a dual function for Ye. The act of recording the song represented overcoming the physical disability imposed by his near-fatal car crash, demonstrating his toughness in the face of adversity. Yet in the process, it also represented overcoming the social disability imposed by those who doubted his potential as a rapper, those who thought he was simply too wack for an opportunity as a recording artist; it proved his commercial viability. Similar to the way in which the masquerade of Stein’s cast complicates his arm’s functionality (is he impaired by cerebral palsy or by a broken thumb?), Ye blurs the boundaries of these two obstacles in “Through the Wire.” Such a reading enriches the potential significance of some of the song’s other features, and over the introduction, for example, he ad-libs the following (Audio Example 10):

Yo, Gee, they can’t stop me from rappin’, can they?

Can they, Hop?(27)

Audio Example 11. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2002), outro, which cuts into in extended sample from Elton John, “I’m Still Standing” (1983) (3:21–4:00)

Ye doesn’t elaborate any further, leaving an ambiguity open: are “they” the wires in his mouth or the industry executives who only wanted his beats and not his rhymes? Ultimately, however, neither could have prevented him from realizing his ambitions as an MC. The song’s original placement on the mixtape Get Well Soon

I’m still standing better than I ever did

Looking like a true survivor, feeling like a little kid

And I’m still standing after all this time

Picking up the pieces of my life without you on my mind

I’m still standing (yeah, yeah, yeah)

I’m still standing (yeah, yeah, yeah)

[3.16] Exploring the correspondences between the masquerade of disability disguise and Ye’s narrative of overcoming offers another perspective on his decision to embrace a disability identity. But as with the problematic dimensions of his disability exaggeration discussed above, there are also issues with certain aspects of his engagement with this kind of masquerade. Although tempering his perceived weakness as a rapper with his physical incapacitation effectively allows him to triumph over both (notwithstanding lingering doubts about his technical abilities), it is difficult not to discern shadows of opportunism in his situation. Disability approaches the status of a prop for Ye, the spectacular springboard from which he would ultimately launch his career.

4. Cripping Chaka Khan, Claiming Disability, and Closing Thoughts

Audio Example 12. Chaka Khan, “Through the Fire” (1985), Chorus (3:10–4:05)

[4.1] My final section will briefly consider Ye’s sampling of Chaka Khan from a “crip” perspective, exploring how the distortion of her voice (and, by extension, body) resists contemporary society’s “compulsory able-bodiedness” (McRuer 2006, 35). As McRuer writes in Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability, crip theory “emerges from cultural studies traditions that question the order of things, considering how and why it is constructed and naturalized; how it is embedded in complex economic, social, and cultural relations; and how it might be changed” (2006, 2). While a more complete assessment of hip hop’s relation to such a project is beyond the scope of this article, Ye’s song offers a productive entry point into such a discourse and suggests several directions for future study. The original excerpt from Chaka Khan’s song “Through the Fire” (1985) is presented in Audio Example 12:

Through the test of time

Through the fire, to the limit, to the wall

For the chance to be with you

I’d gladly risk it all

Through the fire

Through whatever, come what may

For a chance at loving you

I’d take it all the way

Right down to the wire

Even through the fire

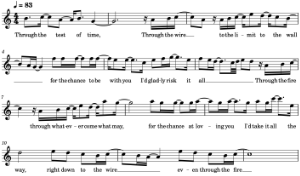

Example 5. Transcription of Chaka Khan’s chorus as it appears in the opening measures of “Through the Wire.”

(click to enlarge)

Audio Example 13. Ye, “Through the Wire” (2003), Introduction (0:00–0:36). Note that this excerpt is drawn from the 2003 version of the song due to the slightly better audio quality of the Chaka Khan sample

[4.2] When Ye samples this excerpt as the backbone of “Through the Wire,” he speeds and pitches it up by about 28%, moving it up roughly four semitones from

[4.3] Next, consider Chaka Khan’s extraordinary voice and impossible body against the voice and body of Ye’s, which is also extraordinary but in a different way. The two collide in the song’s chorus, where their affects are strikingly opposed: the extreme register and timbre of Chaka Khan’s sample is ethereal and otherworldly, while Ye’s presence through his muffled ad-libs (left intact from the original version in the 2003 re-recording) is viscerally physical. There is really very little that is outwardly “normal” about the bodies presented in “Through the Wire.” Following McRuer (2006, 34), we can then begin to imagine how these two voices work in tandem to resist the ideologies of ability and able-bodiedness, and how they “come out crip” to claim stigmatized positions. A certain logic emerges in this pairing: the deformation of Chaka Khan’s body inverts the deformation of Ye’s, and the two together perform a spectacle of otherness. I am not suggesting, however, that every instance of a pitched-up vocal sample demands a parallel impairment in the rapping voice, or that non-normative hip-hop voices of the kind described earlier require a correspondingly deformed accompaniment. Rather, I believe that attending to aspects of disability in “Through the Wire” shines new light on the relationship between Ye and Chaka Khan, and more broadly on the interface between hip hop’s layers of rapped vocals and sampled accompaniments. Chaka Khan’s sample forms Ye’s chorus, and gives rhythmic, harmonic, and melodic shape to the song as well as providing its title. But her presence is significant from a bodily perspective, too, adding a deeper layer of meaning to the narrative of “Through the Wire.” Analyzing the interactions between the rapped vocal parts (or “flow”) and beat layers in hip hop has been subject to a wide variety of approaches in recent years (Adams 2009; Adams 2016; Adams 2020; Duinker 2021; Krims 2000; Manabe 2019; Ohriner 2017; Ohriner 2019), and this brief comparison indicates that the spectrum of ability suggested by the voices and bodies present is another axis of possible inquiry.

[4.4] Despite the potential insights of a disability-based reading of “Through the Wire,” I am nonetheless wary of positioning the song as an exemplary celebration of disability and difference, given the asymmetrical—and gendered—power relation between Ye and Chaka Khan. Chaka Khan’s vocal deformations are entirely imposed upon her by Ye, and the sampling process strips her of any agential control. Chaka Khan spoke candidly about her displeasure with the song in a 2019 interview, which she called “stupid.” Although she initially agreed to his use of her song and legally cleared the sample, she later told interviewer Andy Cohen that “when it came out [here Chaka Khan imitates the high-pitched, sped-up hook] I was pissed. I thought it was a little insulting

[4.5] Given the ubiquity of sampling in hip-hop practice, the potential for a “crip” reading of sampling might productively uncover other functions of disability within this culture. And just as queering a text often involves altering and even subverting its meaning, Ye’s revision of Chaka Khan’s “through the fire” to “through the wire” is itself an act of cripping, reasserting its potential connotations from a profession of love to an expression of disability. In this respect, Ye’s cripping of Chaka Khan also belongs within the framework of signifyin’ (Gates 1983; Gates 1988), a Black American expressive practice concerning double-voicedness, revision, play, and meaning-making in opposition to dominant hegemonic forces. While the relationship between hip hop and signifyin’ has already been well established (Demers 2003; Garrett 2014; Gaunt 2006; Potter 1995; Schloss 2004; Williams 2013; Williams 2015), the potential role of disability within this cultural tradition remains to be explored in detail.

Audio Example 14. Common, “They Say” (2005), Verse 2, emceed by Ye (2:04–2:18)

[4.6] An often-repeated sentiment in disability studies is that disability is all around us. There is almost no-one whose life is untouched by it to some degree. If nothing else, consider the impairments of mind and body that reach us—or our loved ones—in old age. As Douglas Baynton (2001, 52) writes, “disability is everywhere in history, once you begin looking for it, but conspicuously absent in the histories we write.” Those familiar with Ye will know that issues related to disability in his life and work extend far beyond “Through the Wire,” and that there are indeed plenty of absences even in the account that I write above. In a widely publicized incident in late 2016, for example, Ye was admitted to hospital after a cancelling a concert mid-tour in Sacramento, California, following a “psychiatric emergency” (Coscarelli 2016). He would later announce that he had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and his 2018 album Ye features the handwritten statement “I hate being Bi-Polar its awesome” on its cover, in lieu of any other text. Even as early as 2005, in a guest verse on Common’s song “They Say” (which he also produced the beat for), Ye raps (Audio Example 14):

They say because of the fame and stardom

I'm somewhere in between the church and insane asylum

I guess it’s messin’ with my health then

And this verse so crazy when I finish

I’m just gon’ check myself in, again

[4.7] Ye’s diagnosis of bipolar disorder has the potential to drastically reshape our understanding of him as both an artist and as a public figure. As noted in one study, “up to 60% of individuals with bipolar disorder present before age 21 years” (Grande et al. 2016, 1567); Ye was 25 at the time of his accident in 2002. In focusing primarily on the physical dimensions of Ye’s “Through the Wire,” however, the analyses presented above have deliberately avoided attempting to draw connections between his actions and any nascent markers of the affective disorder with which he would later be diagnosed. Although some of Ye’s behavior at the time might invite interpretation along such lines, and such perspectives could offer valuable insight into his early work, I nonetheless believe that it is too fraught to speculate about the influence of a condition clinically post-dated by close to fifteen years. There is simply too much we don’t know. In any case, however, Ye’s overtly—even defiantly—non-normative relationship with his body and mind makes him a productive subject through which to explore disability’s function in hip hop, and I hope that others might continue to work in this area, particularly concerning the music he has released in the years following his diagnosis. Since 2017, hip hop has been the most-consumed style of music in the United States; there seems no place better, then, for affirming Baynton’s pointed reminder that “disability is everywhere.”(29)

[4.8] In this article, I have demonstrated the various ways in which the concept, recording, promotion, reception, and musical qualities of “Through the Wire” interact with concerns drawn from disability studies. I have argued that a public fascination with disability (despite its ongoing stigmatization in other contexts) was at least partially responsible for the widespread success of “Through the Wire,” and that two different dimensions of the disability masquerade are present throughout the song’s two versions. My analyses demonstrate how Ye both exaggerates and disguises different disabling conditions, which together serve to complicate the song’s seemingly straightforward narrative of triumphant overcoming. The masquerade-as-exaggeration helps reconcile the inclusion of ad-libs projecting a disabled bodily state in an otherwise nondisabled context as a kind of performative embellishment, while the masquerade-as-disguise suggests a path through which Ye was able to reach success despite widespread concerns about his rapping abilities. Finally, the two kinds of bodies in the song—Ye’s and Chaka Khan’s—also work together in making non-normativity visible and even celebrated.

Jeremy Tatar

Schulich School of Music

McGill University

555 Rue Sherbrooke Ouest

Montreal, QC H3A 1E3

jeremy.tatar@mail.mcgill.ca

Works Cited

Adams, Kyle. 2009. “On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music.” Music Theory Online 15 (5). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.15.5.1.

—————. 2016. “Playing with Beats and Playing with Cats: Meow the Jewels, Remixes, and Reinterpretations.” Music Theory Online 22 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.3.1.

—————. 2020. “Harmonic, Syntactic, and Motivic Parameters of Phrase in Hip-Hop.” Music Theory Online 26 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.2.1.

Adelman, Rebecca A. 2005. “‘When I Move, You Move’: Thoughts on the Fusion of Hip-Hop and Disability Activism.” Disability Studies Quarterly 25 (1). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v25i1.526.

Ahmed, Insanul. 2014. “The Making of [Ye’s] ‘The College Dropout.’” Complex, February 10, 2014. https://www.complex.com/music/2014/02/kanye-west-college-dropout-making-of/.

Bailey, Julius. 2014. “Preface: The Cultural Impact of [Ye].” In The Cultural Impact of [Ye], ed. Julius Bailey, xvii–xxvii. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137395825.

Bailey, Moya. 2011. “‘The Illest’: Disability as Metaphor in Hip Hop Music.” In Blackness and Disability: Critical Examinations and Cultural Interventions, ed. Christopher M. Bell, 141–48. Michigan State University Press.

Baynton, Douglas. 2001. “Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History.” In The New Disability History, ed. Paul Longmore and Lauri Umansky, 33–57. New York University Press.

Breihan, Tom. 2007. “Review: Prodigy, Return of the Mac.” Pitchfork, April 20, 2007. https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/10116-return-of-the-mac/.

Caramanica, Jon. 2004. “College Dropout.” Rolling Stone, March 4, 2004. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/college-dropout-255465/.

Cheng, William. 2016. Just Vibrations: The Purpose of Sounding Good. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9293551.

—————. 2019. “Gaslight of the Gods: Why I Still Play Michael Jackson and R. Kelly for My Students.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, September 15, 2019. https://www.chronicle.com/article/gaslight-of-the-gods-why-i-still-play-michael-jackson-and-r-kelly-for-my-students/.

Christgau, Robert. 2005. “Growing by Degrees.” The Village Voice, August 30, 2005. https://www.villagevoice.com/2005/08/30/growing-by-degrees/.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. 2009. “The Mask of Doom: A Nonconformist Rapper’s Second Act.” The New Yorker, September 14, 2009. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/09/21/the-mask-of-doom.

Collins, Hattie. 2005. “[Ye] – ‘Late Registration’ review.” NME, September 12, 2005. https://www.nme.com/reviews/reviews-kanye-west-7752-312902.

Couser, Thomas G. 1997. Recovering Bodies: Illness, Disability, and Life-Writing. University of Wisconsin Press.

Coscarelli, Joe. 2016. “[Ye] Is Hospitalized for ‘Psychiatric Emergency’ Hours After Canceling Tour.” New York Times, November 21, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/21/arts/music/kanye-west-hospitalized-exhaustion.html.

Cush, Andy. 2016. “Here’s Definitive Proof That [Ye’s] ‘Through the Wire’ Accident Wasn’t Faked.” Spin, September 15, 2016. https://www.spin.com/2016/09/kanye-through-the-wire-accident-not-fake/.

Cusick, Suzanne. 2008. “Musicology, Torture, Repair.” Radical Musicology 3. http://www.radical-musicology.org.uk/2008/Cusick.htm.

Davis, Kimberly. 2004. “The Many Faces of [Ye].” Ebony 59 (8): 90–95.

—————. 2005. “[Ye]: Hip-Hop’s New Big Shot.” Ebony 60 (6): 156–61.

Davis, Lennard J. 2013. “Introduction: Normality, Power and Culture.” In The Disability Studies Reader, 4th ed., ed. Lennard J. Davis, 1–16. Routledge.

Dederer, Claire. 2017. “What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?” The Paris Review, November 20, 2017. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/11/20/art-monstrous-men/.

Demers, Joanna. 2003. “Sampling the 1970s in Hip-Hop.” Popular Music 22 (1): 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143003003039.

Duinker, Benjamin. 2021. “Segmentation, Phrasing, and Meter in Hip-Hop Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 43 (2): 221–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtab003.

Dukes, Rahman. 2008. “[Ye’s] ‘Through the Wire’ Has Extra Meaning for One MTV Staffer.” MTV, November 24, 2008. http://www.mtv.com/news/2574810/kanye-wests-through-the-wire-has-extra-meaning-for-one-mtv-staffer/.

Endelman, Michael. 2004. “College Dropout.” Entertainment Weekly, February 13, 2004. https://ew.com/article/2004/02/13/college-dropout/.

Foley, Brenda. 2013. “Passing Strange: Illness, Shame and Performance.” In Chronicity Enquiries: Making Sense of Chronic Illness, ed. Zhenyi Li and Sara Rieder Bennett, 111–17. Inter-Disciplinary Press. https://doi.org/10.1163/9781848881501_012.

French, Martha M. 2016. “A Show of Hands: The Local Meanings and Multimodal Resources of Hip Hop Designed, Performed, and Posted to YouTube by Deaf Rappers.” PhD diss., University of Rochester.

Frere-Jones, Sasha. 2005. “Overdrive: [Ye’s] high-octane ego.” New Yorker, August 14, 2005. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/08/22/overdrive.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 2002. “The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography.” In Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities, ed. Sharon L. Snyder, Brenda Jo Brueggemann, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, 56–75. Modern Language Association.

—————. 2017. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. 20th anniversary ed. Columbia University Press.

Garrett, Charles Hiroshi. 2014. “‘Pranksta Rap’: Humor as Difference in Hip Hop.” In Rethinking Difference in Music Scholarship, ed. Olivia Bloechl, Melanie Lowe, and Jeffrey Kallberg, 315–37. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139208451.011.

Gates, Jr. Henry Louis. 1983. “The ‘Blackness of Blackness’: A Critique of the Sign and the Signifying Monkey.” Critical Inquiry 9 (4): 685–723.

—————. (1988). The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. Oxford University Press.

Gaunt, Kyra. 2006. The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double-Dutch to Hip-Hop. New York University Press.

Goodman, Nanette, Michael Morris, and Kelvin Boston. 2017. “Financial Inequality: Disability, Race and Poverty in America.” National Disability Institute. https://www.nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/disability-race-poverty-in-america.pdf.

Grande, Iria, Michael Berk, Boris Birmaher, and Eduard Vieta. 2016. “Bipolar Disorder.” The Lancet 387 (10027): 1561–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00241-X.

Grant, Shawn. 2019. “Chaka Khan calls [Ye’s] ‘Through the Wire’ Sample ‘Stupid.’” The Source, June 27, 2019. https://thesource.com/2019/06/27/chaka-khan-through-the-wire/.

Guck, Marion A. 1996. “Music Loving, Or the Relationship with the Piece.” Music Theory Online 2 (2). Journal of Musicology 15 (3): 343–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/763915.

Hanson, Ellis. 2011. “The Future’s Eve: Reparative Reading after Sedgwick.” South Atlantic Quarterly 110 (1): 101–19. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-2010-025.

Hattenstone, Simon. 2020. “50 Cent on Love, Cash and Bankruptcy: ‘When There are Setbacks, There Will Be Get-Backs.’” The Guardian Online, May 4, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/may/04/50-cent-on-love-cash-and-bankruptcy-when-there-are-setbacks-there-will-be-get-backs.

Heaton, Dave. 2004. “[Ye]: The College Dropout.” Popmatters, March 4, 2004. https://www.popmatters.com/westkanye-college-2496110889.html.

Hinton, Anna. 2017. “‘And So I Bust Back’: Violence, Race, and Disability in Hip-Hop.” CLA Journal 60 (3): 290–304. https://doi.org/10.1353/caj.2017.0013.

Holmes, Jessica. 2017. “Expert Listening beyond the Limits of Hearing: Music and Deafness.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 70 (1): 171–220. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2017.70.1.171.

Hunt, Morgan. 2017. “Though the Wire: 15 Years Later.” WIUX, October 23, 2017. https://www.wiux.org/article/2017/10/though-the-wire-15-years-later.

Ingham, Tim. 2009. “Chaka Khan.” Metro UK, October 27, 2009. https://metro.co.uk/2009/10/27/chaka-khan-241120/.

Johnson, Jr., Billy. 2004. “Live Wire.” Yahoo! Music, April 11, 2004. https://web.archive.org/web/20070611213809/http://music.yahoo.com/read/interview/12033791.

Krims, Adam. 2000. Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity. Cambridge University Press.

Kuppers, Petra. 2015. “Performance.” In Keywords for Disability Studies, ed. Rachel Adams, Benjamin Reiss, and David Serlin, 137–39. New York University Press.