Buffy Sainte-Marie’s Self-Expressive Voice

Nancy Murphy

KEYWORDS: Buffy Sainte-Marie, singer-songwriter, self-expression, voice, vibrato, flexible meter, protest songs, activist songs

ABSTRACT: Buffy Sainte-Marie is a Cree singer-songwriter who emerged in the folk-inspired Greenwich Village coffeehouse scene in the mid-1960s. From her positionality as an Indigenous woman, Sainte-Marie wrote protest music (“activist songs”) on topics including antiwar themes and issues facing Native Americans. Her provocative 1966 activist song “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” is an anthem to decolonization that aims to educate her listeners about acts of genocide against Indigenous communities in the United States and Canada. The song’s lyrics, however, are only one aspect of its significance. In this article, I draw on studies of voice and flexible meter to explore Sainte-Marie’s self-expressive vocal rhetoric in three extant recordings of “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying”—two from 1966 and one from 2017. I explore how Sainte-Marie’s flexible hypermeter and vibrato techniques add layers of expressive impact to her performances and help to position Sainte-Marie as an innovator in the singer-songwriter tradition.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.29.3.5

Copyright © 2023 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

Video Example 1. Sainte-Marie, “Men of the Fields” (Rainbow Quest, 1966), Verse 1 (31:30–32:19)

(click to watch video)

[1.1] In 1966, Buffy Sainte-Marie appeared as a guest star on Pete Seeger’s television program Rainbow Quest, which ran from 1965 to 1966 and provided a venue for important voices in the mid-century folk revival.(1) On Sainte-Marie’s episode, she shares several songs with Seeger and demonstrates the range of her self-expressive performance style. Her performance of “Men of the Fields” (Video Example 1) includes regular meter and a relatively gentle vocal style, the latter of which displays her characteristic vibrato on both vowel and nasal sounds.(2)

Video Example 2. Sainte-Marie, “My Country ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” (Rainbow Quest, 1966), Verse 4 (21:39–22:29)

(click to watch video)

[1.2] Her vibrato in “Men of the Fields” is relatively unmarked when compared with some of Sainte-Marie’s other, more impassioned performances. Compare, for instance, her performance of “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” ten minutes earlier in her Rainbow Quest appearance (Video Example 2). In this song, Sainte-Marie demonstrates some of the more dramatic features of her singer-songwriter performance practice. First, there is a flexibility to the song’s hypermeter that offers an expressively timed four-beat framework. Second, and perhaps even more salient, a variety of vibrato-related pitch manipulations in the melody seem to arise as in-the-moment responses to the emotional content in the lyrics. This exhibits a much different performance rhetoric than the folk-song style in “Men of the Fields,” and it provides a rich text for analyzing Buffy Sainte-Marie’s singer-songwriter voice.

[1.3] It is not remarkable to find flexible meter and vibrato in popular singing, even within the singer-songwriter tradition. But it is remarkable to find the range of techniques that Sainte-Marie uses to manipulate her pitch for self-expression—from her typical consistent vibrato to more disrupted, animated vibrato effects—especially when considered alongside the effects of her flexible hypermeter. In this article, I explore Sainte-Marie’s self-expressive vibrato and meter across the three extant recordings of “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying”: (1) her 1966a studio recording for Little Wheel Spin and Spin, (2) the aforementioned 1966b performance on Rainbow Quest, and (3) her return to the song for her 2017 album Medicine Songs. For this investigation, I draw on my (2023) monograph on self-expressive flexible meter alongside research on voice by Kate Heidemann (2016), Victoria Malawey (2020), Steven Rings (2015), among others, to theorize flexible hypermeter and vibrato in Sainte-Marie’s performances of this song. I analyze her flexible hypermeter and identify six types of pitch manipulation in her singing, establishing consistent vibrato as the baseline approach from which Sainte-Marie transforms her vocal performance rhetoric within and between the 1966 and 2017 recordings.

[1.4] This study’s primary goal is to demonstrate that the expressive impact of Sainte-Marie’s “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” performances is the result of both flexible hypermeter and intensified vocal style, particularly her use of vibrato. But this work will also demonstrate the rhetorical import of these features for Sainte-Marie’s broader performance practice. This vocal rhetoric is a unique contribution to the 1960s singer-songwriter movement alongside her positionality as a Canadian-born, American, Indigenous (Cree) woman, her influence in the protest song tradition, and the broader significance of her inimitable artistic voice. Her music is largely understudied in comparison to her peers like Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell, but her output offers much to be explored in investigating singer-songwriter self-expression.(3)

Buffy Sainte-Marie and the Protest Song Tradition

[2.1] Buffy Sainte-Marie first gained prominence as a singer-songwriter in the mid-1960s Greenwich Village folk scene.(4) After a 1963 performance at the Gaslight Café—a central venue for the 1960s singer-songwriter performance community—music critic Robert Shelton (1963) called her “one of the most promising new talents on the folk scene.” In addition to performing folk revival song adaptations from the Delta blues and ballad traditions (like her peers in the folk revival movement), Sainte-Marie also displayed her individual perspective on protest songwriting.(5)

[2.2] Some protest songs from this period were created by repurposing folk revival songs as protest anthems, like the gospel hymn “We Shall Overcome.” Others were original song compositions that referenced specific events in the civil rights movement, like Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddamn,” which responded to the murder of NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers.(6) Bob Dylan often wrote songs specific to certain events, such as “The Ballad of Emmett Till” and “With God on Our Side” (the latter of which also addresses Evers’s Murder).(7) But Dylan also specialized in songs that reflected the more general mood of the 1960s, including “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

[2.3] Sainte-Marie calls her contributions to the protest song tradition “activist songs.”(8) Her most popular song in this category is “Universal Soldier,” which she wrote in response to the Vietnam War.(9) But her songs about Indigenous activism stand out in her catalogue in comparison to the output of her mostly white singer-songwriter peers. As a Cree woman, Sainte-Marie has a particular platform as a singer-songwriter, and she writes original activist songs to address issues facing Indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada.(10) Examples like “Now that the Buffalo’s Gone” and “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” demonstrate Sainte-Marie’s commitment to use her platform to educate her listeners about Indigenous lives—a commitment that began in the 1960s and continued throughout her public career, including in musical performances, interviews, and on television appearances, especially during her time as a cast member on Sesame Street.(11)

Example 1. “My Country ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” lyrics from Little Wheel Spin and Spin (1966)

(click to enlarge)

[2.4] “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” (hereafter “My Country”) is an activist song that provides a history of Indigenous life in the United States to counter the inaccurate and inadequate accounts existing in textbooks and school curricula in the 1960s.(12) Arden Ogg (2021) from the Cree Literacy Network describes the song as an “anthem to decolonization” that “packs a whole master class in Indigenous awareness.”(13) The 1966 lyrics (Example 1) recount the missing history of Native Americans in the education system, including descriptions of broken treaties and displaced Indigenous populations.(14) The 2017 recording targets Sainte-Marie’s birth country and surveys details about Canada’s Indigenous history.(15) This version’s lyrics often focus on residential schools, where children were abducted from Indigenous communities by government officials under the guise of education and faced abhorrently abusive conditions and a broader attempt to erase their Indigenous languages and cultures.(16) In this song, and in public discussions about the topic, Sainte-Marie frames residential schools as cultural genocide against Indigenous communities in the United States and Canada.

[2.5] The 1966 “My Country” lyrics provide details about Indigenous lives in the United States. The first verse, according to Sainte-Marie’s commentary (Ogg 2021), “expresses appreciation for the attention you are giving [these lyrics] by reading and listening and acknowledges that you have actually been hoodwinked throughout your education regarding Indigenous people, history and cultures.” Verse 1 references “school propaganda” that depicts Native Americans as “colorful, noble and proud” yet reduced in the 1960s public consciousness to their representation chasing cowboys across “America’s movie screens.”(17) The penultimate line in Verse 1 positions Sainte-Marie as a representative, who has been asked to comment on Indigenous history, both past and present. Her refrain for each verse is her response, which quotes the American patriotic song “My Country ’Tis of Thee” (itself a reworking of the British “God Save the King”). Through her lyrical reference and quoted melody, Saine-Marie implores her listeners to imagine the racism and power imbalances pervading the longstanding institutions in these countries with oppressive colonial histories. While some United States citizens can indeed “let freedom ring,” this freedom is not equally afforded.

[2.6] Later verses in the 1966 “My Country” recordings reference specific oppressive acts against Native American populations. For example, she sings about residential schools and the Kinzua Dam in Verse 2, smallpox blankets in Verse 3, and the trauma of colonization and hypocritical treaties in Verses 4 and 5.(18) Sainte-Marie includes these details both to make her listeners aware of historical events and to invite change in school curricula to more accurately portray the brutality and racism that pervades Native American histories.

Self-Expression

Example 2. Summary of Murphy (2023), four main features of self-expression in singer-songwriter music

(click to enlarge)

[3.1] The edifying lyrics in “My Country” show how Sainte-Marie’s songwriting aligns with her work as an Indigenous activist and educator.(19) However, the song’s lyrics are only one of its four central self-expressive features, alongside self-presentation, vocal production techniques, and flexible meter; see Example 2 for a summary.(20) For Sainte-Marie, lyrics convey her activist agenda as a representative for Indigenous communities. Her self-presentation as a female Cree folk singer, alongside other choices about her appearance and the ways she presents herself to audiences, shape her singer-songwriter persona. Her flexible meter and vocal style are performance aspects that contribute to her musical rhetoric. While her persona and lyrics reveal something about herself in performance, there is import in her music both in what she is saying and how she is saying it.

Flexible Hypermeter in Sainte-Marie’s “My Country,” Little Wheel Spin and Spin (1966a)

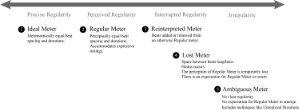

Example 3. Murphy (2023), five types of flexible meter

(click to enlarge)

[4.1] “My Country” was released on Little Wheel Spin and Spin as the longest track (6:48) and the only activist song on the album.(21) This song is also one of the few tracks on the album in which Sainte-Marie explores metric flexibility in her performance.(22) Example 3 reproduces the types of flexible meter that I explore in Murphy (2023), plotting Regular Meter and Lost Meter on a spectrum that accounts for the metric types that arise in singer-songwriter music.(23) In Sainte-Marie’s performances of “My Country,” her timings result in Regular and Lost hypermeter. Flexible meter provides the theoretical framework to illustrate how Sainte-Marie vacillates between passages with Regular hypermeter (a predictable but flexibly timed hypermetric structure) and Lost hypermeter (a scenario in which timings become so flexible that regularity can no longer be predicted).

[4.2] The song’s hypermetric flexibility arises from Sainte-Marie’s expressive timing.(24) Her performance yields four strong syllables per lyrical line, (i.e., “Now that your big eyes are fi-nally o-pened.”), which Sainte-Marie aligns with downbeats in a simple triple meter. Sainte-Marie changes the duration between each hyperbeat; at times this yields an expressively timed regular hypermeter, but in some passages it results in hyperbeats so spaced apart that the hypermeter becomes impossible to follow.

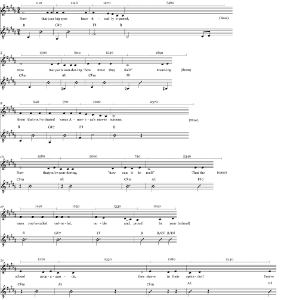

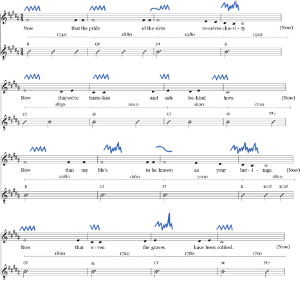

Example 4. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin, 1966), Verse 1 lines 1–2 (0:00–0:12)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.3] The perceived hypermetric regularity results from the expectation that four hyperbeats will occur in each line. Her line 1 timings (Example 4) include durations between hyperbeats 1–2 (1110 ms) and 2–3 (1140 ms) that are approximately equal in duration, followed by a similar duration between hyperbeats 3–4 (1270 ms).(25) These nearly isochronous durations create a Regular hypermeter with flexible timing. But the following duration (3460 ms between hyperbeat 4 and the next hyperdownbeat) is more than three times as long as the previous durations, creating Lost hypermeter before the second line begins. There is an implied fulfillment of metric potential—a sense that the expected hyperbeat will eventually occur—without knowing when that will happen. This creates an unpredictable metric effect that echoes the unsettling subject matter. In “My Country,” the durations between hyperbeats within each line are sufficiently consistent that hypermeter is Regular, but expressive timing between lines is so extreme that the hypermeter is Lost.(26)

Example 5. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin, 1966), Verse 1 (0:00–0:55)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.4] In Verse 1 from the Little Wheel Spin and Spin studio recording (Example 5), Sainte-Marie pauses and accelerates at unexpected moments, creating striking expressive effects.(27) In line 1, Lost hypermeter first arises during the long duration between the fourth and fifth measure. The second system (mm. 5–8) has a more predictably Regular hypermetric profile. The subsequent material (mm. 9–12) speeds up as Sainte-Marie sings about Native Americans being chased across movie screens. The refrain (mm. 29–32) stands out from the rest of the verse when Sainte-Marie tightens her timing. Though the refrain’s hyperbeat durations are longer than those of the previous hypermeasure (mm. 25–28), the quarter-note tactus subdivisions become regularized for the first time in the song, drawing attention to this metric level rather than the hypermeter. There is some syncopation in this refrain, but the overall impression is of the rhythms tightening into militaristic order to mimic the “My Country ’Tis of Thee” rhythm along with the melodic quotation (which spans the first five quarter notes).

[4.5] The second verse has more consistently Regular hypermeter than the opening verse, due in part to the increase in rhythmic density at the tactus level in Sainte-Marie’s guitar accompaniment, alongside the added bass line played by Russ Savakus. The third and fourth verses are similarly regular. It is somewhat of a surprise, then, in the fifth and final verse, when Sainte-Marie revives Verse 1’s hypermetric flexibility (which had been absent since then). Her accompaniment returns to the heavily accented downbeats from the opening, removing the tactus beat subdivisions of these hyperbeats to allow allowing for more timing flexibility between them. This creates a sense of drama that intensifies the more personal nature of the verse’s lyrics. In the passage from 5:08–5:22, Sainte-Marie slows her tempo and increases metric flexibility as she sings the lines “Now that my life’s to be known as your heritage/Now that even the graves have been robbed.” This is the first moment Sainte-Marie refers to herself since Verse 1, recounting her own experiences as a Cree woman to represent the way that Indigenous communities are relegated to figures of history rather than the present.

Vibrato

[5.1] Sainte-Marie’s voice demonstrates the most striking emotive techniques when she is singing about her own life, especially in the song’s fifth and final verse. Her flexible meter here occurs alongside her characteristic vocal style, driven in part by what Steven Rings (2015, 668) describes as her “tight vibrato” and “extraordinary timbral resources.” This vibrato arises in lines like “Hands on our hearts / We salute you your victory,” in which the heightened declaration causes wavering in Sainte-Marie’s voice that suggests an emotional outpouring.(28)

Video Example 3. Sainte-Marie, commentary on CBC about her vibrato (0:00–0:04, 1:01–1:47)

(click to watch video)

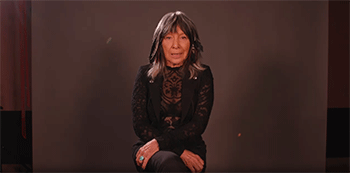

[5.2] In a televised segment for the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC), shown in Video Example 3, Sainte-Marie acknowledges the characteristic vibrato that occurs in her voice. To me, her vibrato sounds like an earnest singing method from an artist wishing to convey emotion through performance. But some critics are less charitable. Robert Shelton (1968), who previously praised Sainte-Marie, still acknowledges her “considerable technical skill” in a 1968 performance but thinks she “obliterated the impact” in her vocal effects by displaying a “wobbly intonation, mannered phrasing and an overworked vibrato that suggested the sound of an outboard motor on a choppy lake.”

[5.3] This unfavorable review overlooks the expressive possibilities of a vocal style that resists pure intonation and simple phrasing. In the CBC (2022) video, Sainte-Marie claims that her vibrato was not something she was “even really aware of” in performance—she was not, as some claim, “putting it on.” My impression is that Sainte-Marie’s vibrato was a feature of her singing that arose in developing her expressive singing voice, as a method of emulating singers like Édith Piaf and the folk and blues artists who were stylistic sources for the 1960s singer-songwriters.(29) Whether intentional or inadvertent, the result is a singing voice with occasional “wobbly” effects that are connected to the qualities of “imperfection” associated with 1960s songwriting: vocal breaks, irregular meter, and a broadly expressive rhetoric.(30) These features of imperfection are widely considered markers of “authenticity” in styles like the Delta blues. As historian Ted Gioia (2008, 73) suggests, these “supposed inadequacies” in Delta blues performances were not, as critics might suggest “limitations to be lamented” but instead are “rather inseparable” from the “brilliance” of these artists.

[5.4] I explore Sainte-Marie’s voice in “My Country” through the lens of her expressive musical rhetoric, where her baseline vocal techniques (consistent vibrato, explored below) are already emotive and markers of imperfection (like her vibrato becoming more animated) are further signifiers of an “authentic” singing style. In this section, I begin by exploring her characteristic vibrato and then analyze the ways that she modifies it in performance for expressive effect.

[5.5] Sainte-Marie’s vibrato is widely considered a hallmark of her singing voice. Andrea Warner (2018, 57) describes Sainte-Marie’s vibrato in “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone” as moving from “gentle insistence to thunderous desperation,” noting there’s a “sweetness to [Sainte-Marie’s] beseeching, and as her message intensifies, she pulls her vibrato up from the depths, the lower register of her vocals like a reluctant growl from the earth’s core.”(31) Regarding the 1966 “My Country” studio recording, Warner (93) suggests that Sainte-Marie’s vibrato seems to resonate “most deeply when exploring the in-between moments of rage and sadness, the space occupied by frustration, heartbreak, and hope.”

[5.6] Singer-songwriter scholars, too, recognize the profound effects that come from Sainte-Marie’s vocal style choices. Steven Rings (2015, 668) describes Sainte-Marie’s vibrato at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival “Cod’ine” performance as a feature that dramatizes Sainte-Marie’s rendition of this personal and painful song.(32) Guilherme Feitosa de Almeida (2021, 168) explores Sainte-Marie’s vocal production for “Soldier Blue” and states that her “vocal style of deep and rapid vibrato permeates the performance, with intense crescendos and choral interventions throughout the musical texture.” And Sofie Athanasia Tsatas (2018, 19) recognizes how dramatic vocal styles shape Sainte-Marie’s positionality, stating that in “comparison with other female folk singers at the time, such as Joan Baez and Judy Collins, Sainte-Marie’s voice is not smooth and clear; rather, she adds this vibrato, demonstrating her intensity, fueling her messages, and establishing a voice for herself and Indigenous peoples.”

[5.7] Research on voice in popular music positions pitch oscillation as a central and universal vibrato feature but suggests that it is highly individual in nature and tends to vary by genre. Victoria Malawey (2020, 37–38) defines vibrato as “tonal oscillation of perceived fundamental frequency and intensity” and suggests that it is an overlooked popular singing component that has the potential (in its presence or absence) to play “a significant role in vocal delivery.”(33) Nina Eidsheim (2019, 170) notes that vibrato “is a vocal stylistic trait that is closely associated with genre and the individual singer” and that “many singers have a signature vibrato that runs through every vocal line.”(34) Malawey (2020, 38) agrees, stating:

Though the use of vibrato may be subtler in popular music than in classical styles . . . its use varies widely among genres and artists, not only delineating genre by degree and nature of its presence, but also marking individual delivery style. Whereas vibrato is essential to unamplified Western classical singing practices, it is perhaps less so in many popular styles. . . . In popular music, vibrato tends to be contingent upon several factors, including genre or style, individual artistry, and emotive effect.(35)

[5.8] Malawey (2020, 38) defines “at least two” types of vibrato based on sound production physiology: “natural vibrato” (also called “laryngeal vibrato”), which occurs in classical and contemporary commercial singing and relies on pitch variation, and a second type called “pop vibrato” (also “hammer vibrato” or “intensity vibrato”) that “relies on variation in subglottal pressure.” To my ear, Sainte-Marie’s vibrato most often displays the first type (laryngeal vibrato), though there are passages when hammer vibrato techniques can be perceived in her singing.(36) In the sections that follow, I propose that Sainte-Marie’s vibrato is remarkable in its prevalence, profile, and variability in her “My Country” performances.”

Vibrato in “My Country” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin, 1966a)

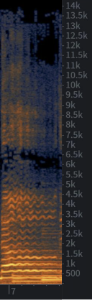

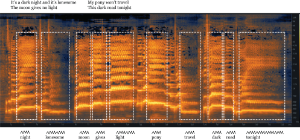

Example 6. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin, 1966), consistent vibrato on the word “say” (1:17)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[7.1] Buffy Sainte-Marie’s vibrato in the 1966a “My Country” studio recording demonstrates her most frequently used vibrato type and the ways that she varies this type for dramatic emphasis throughout the performance. I use the term consistent vibrato to classify her most common vibrato pattern: 8–10 oscillations per second with a pitch range typically spanning about a semitone.(37) The spectrogram in Example 6 shows her consistent vibrato on the word “say” in Verse 1, illustrating a typical profile.(38) The fundamental is the lowest wavering line, around 300 Hz, with overtones shown above, where the consistent vibrato patterns are visually clearer on the spectrogram. I use the term “consistent” to note the pitch range and oscillation regularity that results. This type of vibrato typically arises in her 1960s songs when she holds long durations, and I position this as the unmarked standard vibrato type from which Sainte-Marie’s vocal-style transformations can be observed.(39)

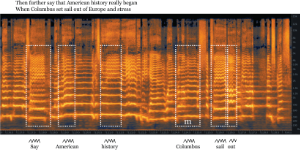

Example 7. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin, 1966), consistent vibrato in Verse 2 (1:16–1:29)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[7.2] This consistent vibrato becomes a relatively neutral sound in comparison to some heightened moments in this “My Country” performance. In Example 7, I have annotated a passage from Verse 2 to analyze some consistent vibrato examples in white boxes on the spectrogram. I include a wavy line above the instances of this vibrato type above the lyrics in this passage to illustrate the pitch profile as it is depicted on the spectrogram. Sainte-Marie uses vibrato both on open vowel sounds and on voiced nasal consonants. For example, here the nasal consonant with vibrato is an “m” sound, so I have included the IPA symbol to indicate the voiced bilabial nasal sound.

Example 8. Baez, “I’m a Rambler, I’m a Gambler” (0:40–1:03)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[7.3] The distinctive profile of Sainte-Marie’s most typical vibrato becomes more evident in comparison with other related vocal styles in the 1960s. Take, for example, Joan Baez’s vibrato in her 1965 live performance of “I’m a Rambler, I’m a Gambler” at the BBC Theatre (Example 8).(40) Baez is another artist from the mid-century folk revival whose singing consistently featured a distinctive vibrato. In this recording (and many others from her catalogue), Baez’s vibrato is consistent, but the pattern is much wider than Sainte-Marie’s, more closely resembling the pitch range and oscillations found in genres like opera and other styles more closely associated with extensive practice and polish—features that contrast the “imperfection” associated with the impression of authenticity in folk and blues performances.(41) In this recording, Baez’s vibrato pattern rarely changes (with around 7 oscillations per second), spanning approximately two semitones in pitch. Baez’s vibrato also rarely changes between performances. This vocal style is expressive, but her vibrato does not seem to respond to lyrical content in the same way that Sainte-Marie’s does. Where Sainte-Marie’s singing intensifies at moments with high emotion, Baez’s remain consistent. For Baez, then, vibrato is subsumed within a larger demonstration of a practiced vocal style from a capable singer displaying polish and perfection in performance.

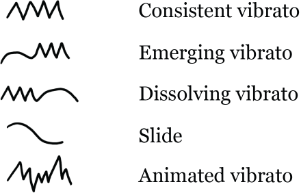

Example 9. Vibrato Types in “My Country”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[7.4] Buffy Sainte-Marie’s vibrato is altogether something different from that of her singer-songwriter peers in its pitch and oscillation profile and propensity to change within and across performances. I classify some vibrato techniques (Example 9) that occur in Sainte-Marie’s 1966 “My Country” performances. This is not an exhaustive list, but these are the vocal styles I see as possible transformations of her typical consistent vibrato. Emerging vibrato occurs when oscillations arise from a steadier or sliding pitch; dissolving vibrato involves oscillations thinning into a consistent or sliding pitch. A simple slide effect sometimes occurs in the place of her usual vibrato. The final type, animated vibrato, shows an uneven disruption to Sainte-Marie’s typically consistent oscillations. This pitch change effect with this technique resembles consistent vibrato in its oscillations (which remain approximately the same number per second as consistent vibrato) but its pitch span becomes less consistent, resembling the more jagged profile in my proposed annotation. (It is for this reason I classify this as a type of transformed vibrato and not an entirely different vocal effect.(42)) Sainte-Marie’s animated vibrato may be the “choppy motor” sound Shelton so dislikes. When this vibrato type arises in performance it often occurs both at moments of peak emotion and in coordination with other expressive vocal techniques like vocal placement and breathing.(43)

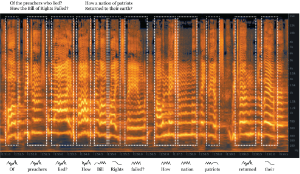

Example 10. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin, 1966), vocal style in Verse 2 (1:51–2:12)

(click to enlarge, listen, and see the rest)

[7.5] Several of these pitch manipulation types occur late in Verse 2 in the 1966a “My Country” studio recording. In one passage (Example 10), Sainte-Marie demonstrates various transformations of her consistent vibrato. Animated vibrato occurs most often alongside a few consistent vibrato moments (on the words “failed” and “nation”), emerging vibrato (on “Bill,” “where,” and “tell”), and some slide techniques (on “Rights” and “there”). In general, Sainte-Marie’s voice is impassioned as she sings about what “history books” should include to offer a more accurate representation of Indigenous lives in North America. Here I see resonances with work on voice and trauma in popular music.(44) In this verse, Sainte-Marie is recounting instances of shared trauma in Native American communities: from governmental manipulations and broken treaties to the metaphorical Liberty Bell ringing for displaced Seneca populations with the Kinzua Dam construction. The instances of animated vibrato in this passage arise in combination with extra breath support and more glottal attack. Each time, vibrato transformations highlight specific lyrics and evoke Sainte-Marie reliving (or at least emotionally reenacting) some of this trauma through her vocal performance.

Example 11. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin, 1966), beginning of Verse 5 (4:53–5:22)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[7.6] The moments of peak intensity in this “My Country” version occur when Sainte-Marie combines her vibrato changes with more flexible timing between hyperbeats. This arises in Verse 5 (Example 11), where the expressive timing is revived after being absent since Verse 1. For instance, in the second line, Sainte-Marie slows her timing at the word “harmless,” then speeds back up for “safe behind laws.” In the third system there is an emotional apex as she sings about her own life being positioned as United States heritage, not as an important feature of its present. Sainte-Marie’s animated vibrato on “life” emphasizes her presence as a representative for Indigenous communities, as a visible reminder of the populations the public is too comfortable ignoring after acts of colonization and genocide.

[7.7] Throughout this passage, consistent vibrato disappears in favor of more animated vibrato as the expressive timing becomes increasingly irregular. In the following lines (“Hands on our hearts / We salute you your victory / Choke on your blue, white and scarlet hypocrisy”), Sainte-Marie’s tempo increases again to the Regular hypermeter of the preceding verses. The loss of consistency in the vibrato pattern alongside the loosening hypermetric profile has a significant impact on lyrical reception in this passage.

“My Country,” Rainbow Quest (1966b)

Example 12 and Video Example 4. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Rainbow Quest, 1966), Verse 1 (17:42–18:37)

(click to see example and watch video)

[8.1] Buffy Sainte-Marie’s 1966b performance on Rainbow Quest exhibits some similar vibrato and flexible meter to her Little Wheel Spin and Spin studio recording. But in this televised performance, there is now access to the visual cues of her self-presentation, mediated by camera angles and lens types.(45) Verse 1, shown in Example 12 and Video Example 4, has an unpredictable profile similar to the studio recording: mostly Regular hypermeter with moments of Lost hypermeter arising mostly at line endings.(46) Her vocal production in this opening verse hints at the vocal intensity that will follow in subsequent verses.

Example 13 and Video Example 5. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Rainbow Quest, 1966), Verse 2 (19:19–20:05)

(click to see example and watch video)

[8.2] In the passage from Verse 2 shown in Example 13 and Video Example 5, Sainte-Marie’s vibrato placement—particularly her animated vibrato—conveys a sense of authentic emotion. The green section in Example 12 contains mostly consistent or emerging vibrato (with a few slide effects, moving both up and down). The word “genocide” stands out in this section, which I have indicated with a larger emerging vibrato annotation.(47) In the pink section, these techniques escalate, especially as she sings words like “liberty,” “brave,” and “Sam,” where her animated vibrato again arises with more breath support and glottal attack. Then, moving to the refrain (highlighted in gray), Sainte-Marie contrasts the heightened vocal drama by pulling back and reducing her pitch profile to mostly consistent vibrato. When coupled with the shift to hypermetric regularity at this moment, the change of vocal style draws attention to the emotional import of this refrain.

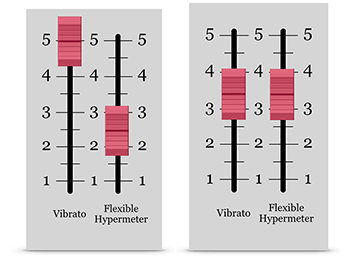

Example 14. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Rainbow Quest, 1966), mixing board interpretation of vibrato and flexible hypermeter (a) Verse 1 (b) Verse 2

(click to enlarge)

[8.3] For passages like these in the Rainbow Quest performance, I like to imagine flexible hypermeter and pitch manipulations as slides on a mixing board that Sainte-Marie can turn up or down at various moments throughout the song for emphasis. Whereas in Verse 1 I hear a similar level for both (Example 14a), in this Verse 2 excerpt (Example 14b) the hypermeter is more Regular, and her vibrato conveys the primary self-expressive rhetoric, mediated by her facial expressions and the producer’s choice for an extremely close-up camera angle.(48)

[8.5] Both of Sainte-Marie’s 1966 “My Country” performances help to build Sainte-Marie’s self-expressive rhetoric for this song, with options to turn the sliders up or down on flexible hypermeter and pitch manipulation (alongside other self-expressive features) to convey the song’s socio-political message and the emotions that come with performing it. These rhetorical decisions seem intentionally connected with self-expression in performance, as methods for conveying the “truth-to-personal experience” realism that scholars like Simon Frith associate with “authentic” storytelling in popular song performance (1988, 118).(49)

“My Country,” Medicine Songs (2017)

[9.1] Sainte-Marie’s social activism continued throughout her career.(50) By 2017, she was in her sixth decade of musical output, having completed seventeen albums and various musical projects including several film scores, a six-year tenure on Sesame Street, and the development of her Cradleboard Teaching Project school curriculum (founded in 1996). This public-facing work mostly focused on activism, and in 2017 Sainte-Marie’s album Medicine Songs echoed this agenda by reviving several activist songs from her earlier catalogue.(51) Four of these revived songs are from her 1960s albums: an updated, Canadian “My Country” version, her 1960s folk-revival style “Little Wheel Spin and Spin,” her famous anti-war protest song “Universal Soldier,” and her Indigenous activist song “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone.” While the rest of the album had ensemble performances, these four songs illustrate her solo singer-songwriter style, with self-accompanying guitar playing.(52)

[9.2] For her new “My Country” recording, the voice-and-accompaniment texture gave Sainte-Marie the opportunity to include the flexible timing of the 1966 versions.(53) Sainte-Marie not only revives the flexible hypermeter, but she also augments it, moving further into Lost hypermeter from passages with hypermetric regularity. Rhythmic values within each line are now shorter, creating greater contrast with the long durations at the ends of each line. There are also dramatic changes to her pitch transformation types. In this recording, Sainte-Marie forgoes long-held pitches with consistent vibrato in favor of shorter durations, more animated vibrato, and an overall breathier and more accented vocal style. Some of these changes to Sainte-Marie’s performance are due in part to the apparent limitations of her vocal age in 2017. Yet rather than being hindrances to new version of the song, these supposed restrictions on her voice can be recast as affordances for her instrument in developing new performance modalities.(54)

Example 15. “My Country ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” lyrics from Medicine Songs (2017)

(click to enlarge)

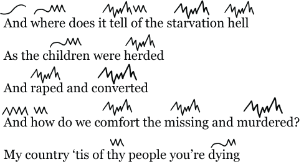

[9.3] The 2017 lyrics (Example 15) offer a Canadian perspective on colonization, this time directly targeting the country of Sainte-Marie’s birth—“From Vancouver Island to the Labrador Sea”—and its similar colonial and genocidal history.(55) These new lyrics were offered at a time when Canada was experiencing a broader public reckoning with its Indigenous history. Between 2008 and 2015, news reports increased about Canada’s history with residential schools and the abuses that took place therein. In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an apology (2008) to residential school survivors a few weeks after a commission was established to investigate these institutions.(56) The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report (2015), which was funded and established between 2007 and 2008, for the first time characterized Canada’s history with its Indigenous populations as a “cultural genocide”—a term Sainte-Marie had been using since the 1960s.(57) In the revamped “My Country,” Sainte-Marie’s lyrics offer some response to this news, with commentary on the children who were “herded and raped and converted” and the broader, horrific impact of residential schools on Indigenous peoples and cultures. She also speaks to broader issues in Canada, from specific references to missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls to more general comments on the supposed “blessings of civilization” that colonization has bestowed on the “few of the conquered” who have “somehow survived.”(58)

Example 16. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Medicine Songs, 2017), Verse 1 (0:00–0:38)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[9.4] The first verse (Example 16) is immediately striking in comparison to the 1966 versions primarily because of the changes in Sainte-Marie’s voice in the 51 years between the recordings. The pitch is slightly lower, with an A tonic—a whole step lower than the B in her 1966 studio recording and a major third lower than the

[9.5] The flexible hypermeter has a similar expressive importance. In the first line, the final duration (3460 ms) is almost five times as long as the previous duration (720 ms). While the first three durations can be heard as expressively timed versions of the same duration length, this too-long final duration results in Lost hypermeter when it disrupts entrainment. The effect is significant as Sainte-Marie sings about eyes finally being opened, almost fifty years after first inviting awareness to these issues. The long pause offers a moment to register how much awareness and change are still needed.

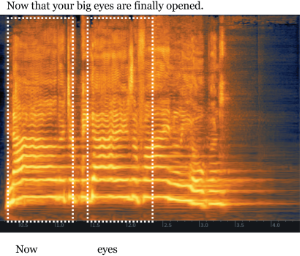

Example 17. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Medicine Songs, 2017), line 1 (0:00–0:04)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[9.6] In this recording I also hear changes to her pitch manipulation types in comparison with the earlier versions. In Verse 1, her voice rarely includes the typical consistent vibrato heard in the 1960s. In the first line (“Now that your big eyes are finally opened”), there is some vibrato on “Now” and “eyes” (Example 17), but it is not as consistent as the vibrato in her 1966 recordings (compare, for instance, with Example 7). On the word “eyes” the vibrato lasts for around half a second, with about 3 oscillations in that time. The pitch oscillation, too, is lessened, spanning about a quarter semitone. The consistent vibrato is, in general, comparatively rare throughout this performance.

[9.7] What occurs instead are pitch transformations that work within the seemingly more limited range of expressive possibilities in Sainte-Marie’s voice. Several studies on vocal aging effects, especially in women’s voices, suggest that developments in “the maturing singer’s voice” include a reduction in vocal endurance, an increase in breathiness, changes in timbre, and a noticeable change in “the rate and size (extent of vibrato).”(61) And indeed, the most significant changes I hear in Sainte-Marie’s voice are shorter durations, a reduction in consistent vibrato articulations, an increase in breathy vocal quality, more air pressure, points of shorter articulation, and a change to nasal vocal placement at emphatic moments, like the refrain.

Example 18. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Medicine Songs, 2017), end of Verse 2 (1:54–2:13)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[9.8] Several of these are audible in her second verse, which targets the Canadian “history books.” Here Sainte-Marie asserts that such texts must include details about residential schools and about missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. The end of Verse 2 (Example 18) demonstrates several new vocal approaches, Sainte-Marie’s voice revealing her passion for the subject matter through its pitch change and timbral features. There are mostly instances of animated vibrato in locations where consistent vibrato would have occurred in her 1960s singing. There is some consistent vibrato (on “of” in line 1, “And how” in line 4, and “thy” in the refrain) but this vibrato type generally occurs on shorter durations than it did in the 1966 versions of this song.

[9.9] In this recording, a new vocal style arises as Sainte-Marie increases vocal pressure on specific words, which creates arresting effects in combination with her raspier vocal timbre. This can be heard at the end of the first line in Example 16, on the words “tell” and “starvation hell,” arising with animated vibrato. It occurs again on “herded,” “raped,” and “converted,” and in the penultimate line on the words “comfort,” “missing,” and “murdered” (emphasizing the rhyming words “herded,” “converted,” and “murdered” with similar vocal timbre). Sainte-Marie’s raspy vocal quality combines with the extra emphasis on these words, increasing the power in her voice to match the intense subject matter.

Example 19. Sainte-Marie, “My Country” (Medicine Songs, 2017), breathy quality in Verse 2 (1:33–1:42)

(click to enlarge and listen)

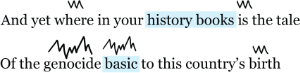

[9.10] Slightly earlier than this passage in Verse 2, Sainte-Marie demonstrates a breathier vocal timbre that is featured throughout this recording.(62) This arises as she sings the lines “and yet where in your history books is the tale / Of the genocide basic to this country’s birth” (echoing the same passage in Verse 2 from the 1966 versions). The blue highlighting in Example 19 denotes words that are marked for attention with breathiness (“history books” and “basic,” the latter of which also features animated vibrato). The most impactful word in this passage is “genocide,” which features animated vibrato and a more nasal placement.

[9.11] The drama in these lines is set into relief by the vocal techniques of the refrain. There is some vibrato during this passage, but the most noticeable effect is the timbral change that results from Sainte-Marie’s nasal placement. This line’s faster tempo combined with the “oral twang” results in a mocking effect, as if Sainte-Marie is feigning a patriotism while singing about her claim to a country that allowed, enforced, and funded genocidal violence against its Indigenous populations.(63)

[9.12] In the Medicine Songs recording, changes to Sainte-Marie’s voice present a different set of vocal techniques than her previous “My Country” versions. She is using a different instrument at age 76 than she did in 1966 (at age 25) but is still working within the affordances of her new voice to showcase different self-expressive modalities.(64) When Sainte-Marie returned to “My Country” for this 2017 album, she was still an Indigenous activist employing a unique vocal style and flexible timing that highlight her song’s message and position her as an important figure in the protest song tradition.

Conclusion

[10.1] This study of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s expressive voice arose from my work on flexible meter in 1960s and 1970s singer-songwriter repertoire. Through this lens I explored the correlation between (hyper)metric flexibility and narrative meaning in Sainte-Marie’s performances and discovered that her vocal effects are also salient participants in passages of expressive metric flexibility. Considering these two self-expressive performance techniques in this study has revealed how essential vibrato and flexible meter are to Sainte-Marie’s singer-songwriter rhetoric. Though they are not present in every recording, these techniques underlie Sainte-Marie’s capacity to maximize drama in performance—these are methods by which she can provocatively deliver her song’s messages.

[10.2] Sainte-Marie’s performances of “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” offer a network of signifiers of self, including group membership, agency, and her approach to building and sustaining relationships with her audiences, relationships that were critically mediated by requests from the United States government to keep her songs off the radio in the 1960s and 1970s.(65) With more attention in the last decade to Sainte-Marie’s output in biographies (Stonechild 2012; Warner 2018), documentaries (Coulter 2012; PBS 2022; Prowse 2014), a podcast (Johnson 2022), and a Canadian stamp, there are more invitations than ever to explore Buffy Sainte-Marie’s creative output and her important self-expressive voice.

Nancy Murphy

University of Michigan

1100 Baits Dr.

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

nemurphy@umich.edu

Works Cited

Attas, Robin. 2020. “Review of Dylan Robinson, Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies (University of Minnesota Press, 2020).” Music Theory Online 26 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.4.10.

—————. 2022. “The Many Paths of Decolonization: Exploring Colonizing and Decolonizing Analyses of a Tribe Called Re’s ‘How I Feel.’” Music Theory Online 28 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.28.2.11.

Bentley, Christa Anne. 2016. “Forging the Singer-Songwriter at the Los Angeles Troubadour.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Singer-Songwriter, ed. Katherine Williams and Justin A. Williams, 78–88. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCO9781316569207.007.

Brant, Jennifer. 2017. “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published March 22, 2017; Last edited July 8, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women-and-girls-in-canada.

Burns, Lori. 2004. “Meaning in a Popular Song: The Representation of Masochistic Desire in Sarah McLachlan’s ‘Ice.’” In Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis, ed. Deborah Stein, 136–48. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2005. “Feeling the Style: Vocal Gesture and Musical Expression in Billie Holiday, Bessie Smith, and Louis Armstrong.” Music Theory Online 11 (3). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.05.11.3/mto.05.11.3.burns.html.

—————. 2010. “Vocal Authority and Listener Engagement: Musical and Narrative Expression Strategies in the Songs of Female Pop-Rock Artists, 1993–95.” In Sounding Out Pop, ed. Mark Spicer and John Covach, 154–92. University of Michigan Press.

Chandler, Kim. 2014. “Teaching Popular Music Styles.” In Teaching Singing in the 21st Century, ed. Scott D. Harrison and Jessica O’Bryan, 35–51. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8851-9_4.

Davis, Dolly Caywood. 2000. “A Study of the Effects of Two Kinds of Vocal Exercises on Selected Parameters in the Singing Voices of Women Over Age Fifty.” PhD diss., University of Iowa.

de Bruin, Tabitha. 2013. “Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published July 11, 2013; Last edited January 16, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indian-residential-schools-settlement-agreement.

Diaz-Gonzalez, Maria. 2020. “The Complicated History of the Kinzua Dam and How It Changed Life for the Seneca People.” The Allegheny Front, February 12, 2020. https://www.alleghenyfront.org/the-complicated-history-of-the-kinzua-dam-and-how-it-changed-life-for-the-seneca-people/.

Dixon, Paul. 2022. “I Spent 10 Years in Residential Schools. This Is What I Want My Grandchildren to Know.” CBC News, July 22, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/first-person-facing-genocide-mohawk-institute-la-tuque-residential-school-1.6527631.

Eidsheim, Nina Sun. 2019. The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre & Vocality in African-American Music. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478090359.

Feitosa de Almeida, Guilherme. 2021. “The Anti-War Voice of Buffy Sainte-Marie.” New Sound: International Journal of Music 58 (2): 161–72. https://doi.org/10.5937/newso2158161F.

Frank, Alex. 2017. “Protest Songs Spell Out Problems. Activist Songs Spell Out Solutions.” The Village Voice, November 15, 2017. https://www.villagevoice.com/2017/11/15/protest-songs-spell-out-problems-activist-songs-spell-out-solutions/.

Frith, Simon. 1988. “Why Do Songs Have Words.” In Music for Pleasure, 105–28. Routledge.

Gioia, Ted. 2008. Delta Blues: The Life and Times of the Mississippi Masters Who Revolutionized American Music. W. W. Norton.

Green, Mitchell. 2007. Self-Expression. Oxford University Press.

Hardman, Kristi. 2022a. “Experiencing Sonic Change: Acoustic Properties as Form- and Meter-Bearing Elements in Popular Music Vocals.” PhD diss., City University of New York.

—————. 2022b. “The Continua of Sound Qualities for Tanya Tagaq’s Katajjaq Sounds.“ In Trends in World Music Analysis: New Directions in World Music Analysis, ed. Lawrence Beaumont Shuster, Somangshu Mukherji, and Noé Dinnerstein, 85–99. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003033080-6.

Hanson, Erin. 2009. “The Residential School System.” Indigenous Foundations. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/the_residential_school_system/.

Harper, Stephen. 2008. “Statement of Apology to Former Students of Indian Residential Schools.” Government of Canada (website). https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100015644/1571589171655.

Heidemann, Kate. 2016. “A System for Describing Vocal Timbre in Popular Song.” Music Theory Online 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.1.2.

Historica Canada. 2023. “Timeline: Indigenous Peoples.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/timeline/first-nations.

Humphrey, Hal. 1968. “She Has Reservations About Indian Roles.” Los Angeles Times, April 25, 1968.

Johnson, Falen. 2022. Buffy. CBC Podcasts.

Lavengood, Megan. 2020. “The Cultural Significance of Timbre Analysis: A Case Study in 1980s Pop Music, Texture, and Narrative.” Music Theory Online 26 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.3.3.

Malawey, Victoria. 2020. A Blaze of Light in Every Word: Analyzing the Popular Singing Voice. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190052201.001.0001.

Mayor, Adrienne. 1995. “The Nessus Shirt in the New World: Smallpox Blankets in History and Legend.” The Journal of American Folklore 108 (427): 54–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/541734.

Milius, Emily. 2021. “Voice as Trauma Recovery: Vocal Timbre in Kesha’s ‘Praying.’” Paper presented at the Society for Music Theory Virtual Conference, November 5.

Moore, Allan F. 2012. Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Ashgate.

Moore, Marlon Rachquel. 2018. “From Rage to Resignation: Reading Tina Mabry’s Mississippi Damned as a Post-Civil Rights Response to Nina Simone’s ‘Mississippi Goddam.’” In Sisters in the Life: A History of Out African American Lesbian Media-Making, ed. Yvonne Welbon and Alexandra Juhasz, 205–24. Duke University Press.

Murphy, Nancy. 2019. “Expressive Asynchrony in Buffy Sainte-Marie Performances.” Paper presented at the Performance Analysis Interest Group, Society for Music Theory Conference, Columbus, Ohio, November 9, 2019.

—————. 2020. “Expressive Timing in ‘With God on Our Side.’” Music Analysis 39 (3): 387–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12151.

—————. 2022. “The Times Are A-Changin’: Metric Flexibility and Text Expression in 1960s and 1970s Singer-Songwriter Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (1): 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtab017.

—————. 2023. Times A-Changin’: Flexible Meter as Self-Expression in Singer-Songwriter Music. Oxford University Press.

“National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.” 2019. mmiwg-ffada.ca. June 3, 2019. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/.

Nobile, Drew. 2022. “Alanis Morissette’s Voices.” Music Theory Online 28 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.28.4.6.

Ogg, Arden. 2021. “My Country ’tis of Thy People You’re Dying: Buffy Sainte-Marie.” Cree Literacy Network (website). Article published February 7, 2021. https://creeliteracy.org/2021/02/07/my-country-tis-of-thy-people-youre-dying-buffy-sainte-marie/.

“Residential School History.” 2023. National Center for Truth and Reconciliation (website). https://nctr.ca/education/teaching-resources/residential-school-history/.

Rings, Steven. 2013. “A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs ‘It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).’” Music Theory Online 19 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.19.4.3.

—————. 2015. “Analyzing the Popular Singing Voice: Sense and Surplus.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 68 (3): 663–70.

Robinson, Dylan. 2020. Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvzpv6bb.

Rosier, Paul C. 1995. “Dam Building and Treaty Breaking: The Kinzua Dam Controversy, 1936–1958.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 119 (4): 345–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20092990.

Roth, Lorna. 2009. “Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity.” Canadian Journal of Communication 34 (1): 111–36. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2009v34n1a2196.

Rothstein, William. 1989. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. Schirmer Books.

Sainte-Marie, Buffy. 1971. The Buffy Sainte-Marie Songbook. Grosset & Dunlap.

—————. 2002. “Cradleboard History.” cradleboard.org. http://www.cradleboard.org/2000/history.html.

—————. 2023a. “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying.” buffysainte-marie.com. https://buffysainte-marie.com/?page_id=785#5.

—————. 2023b. “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying.” buffysainte-marie.com. https://buffysainte-marie.com/?page_id=10878#4.

Shelton, Robert. 1963. “Old Music Taking On New Color: An Indian Girl Sings Her Compositions and Folk Songs.” New York Times, August 17, 1963.

—————. 1968. “Buffy Sainte-Marie Sings at Carnegie Hall.” New York Times, November 30, 1968.

Stonechild, Blair. 2012. Buffy Sainte-Marie: It’s My Way. Fifth House.

Straus, Joseph. 2022. “Musicking While Old: Old Performers.” SMT-Pod, April 28. https://smt-pod.org/episodes/season01/#e1.13.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Honoring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Government of Canada.

Tsatas, Sofie Athanasia. 2018. “She’s Ahead of the Times: A Study of How Buffy Sainte-Marie’s Music Addresses Indigenous Rights.” MA Thesis, University of British Columbia.

Van Rooij, Johannes H. J. M. 1995. Tint detection circuit for automatically selecting a desired tint in a video signal. US Patent 5,428,402 filed April 13, 1994, and issued June 27, 1995.

Warner, Andrea. 2018. Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography. Greystone Books.

Williams, Vicky. 2007. “The Kinzua Dam Controversy.” MA Thesis, State University of New York at Buffalo.

Discography

Discography

Sainte-Marie, Buffy. 1966a. Little Wheel Spin and Spin. Vanguard VRS 9211.

—————. 2017. Medicine Songs. True North TND681.

Videography

Videography

Sainte-Marie, Buffy. 1966b. “Buffy Sainte-Marie.” Rainbow Quest. Channel 47.

—————. 2022a. “Buffy Sainte-Marie: 5 Songs That Changed My Life.” CBC Music. YouTube video, 01:25. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b4OwSDzAhpE.

—————. 2022b. “Buffy Sainte-Marie: Carry It On.” 2022. PBS: American Masters.

Coulter, Philip, dir. 2012. “Still This Love Goes On: The Songs of Buffy Sainte-Marie.” CBC Music.

“Joan Baez—BBC In Concert (1965).” 1965. BBC.

Prowse, Joan. 2014. Buffy Sainte-Marie: A Multimedia Life. True North.

Footnotes

1. Seeger’s show featured various musical acts across the 39 Rainbow Quest episodes. This included, among others, Malvina Reynolds, Judy Collins, Johnny Cash, June Carter, Donovan, Elizabeth Cotton, The Stanley Brothers, Patrick Sky, and Mississippi John Hurt.

Return to text

2. Lavengood (2020, [1.19]) would classify the pitch as “wavering” in contrast to a possible “steady” pitch production; this recognizes that vibrato is often classified as a timbral aspect, though it has more to do with frequency (pitch). By contrast, Heidemann (2016, [2.6]) argues that inflections of pitch (including vibrato) are not timbral, “but may occur in tandem with timbral manipulations by the singer.” In this study, I follow how Heidemann categorizes vibrato as a pitch feature, and I discuss timbre only when it either occurs alongside pitch manipulations or when I perceive timbral changes to occur in place of vibrato.

Return to text

3. I approach Sainte-Marie’s music from my own positionality as a white woman trained in classical European and popular music traditions from the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Throughout this article, I use the word Indigenous to refer to the first inhabitants of lands that were later colonized by white settlers. In interviews and commentary, Sainte-Marie sometimes refers to herself as an Indian, a term I only use when quoting directly. When I am specifically discussing Sainte-Marie or Indigenous peoples in the United States, I use the term Native American. When referring to Canada, I employ the term Indigenous, since First Nations (though it encompasses Sainte-Marie’s Cree heritage) does not include Métis and Inuit peoples. Many thanks to Kristi Hardman for her insights on terminology. For more on positionality, see Attas (2020), Hardman (2022a), and Robinson (2020). See Attas (2022) for commentary on decolonizing music theory and analysis.

Return to text

4. Sainte-Marie was born in 1941 on the Piapot Cree First Nations reserve in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. Biographer Andrea Warner (2018, 16) notes that this was a time “when many Indigenous children were sent to residential schools, others were taken from their parents and adopted into white homes. Sainte-Marie was adopted out of her reserve—for reasons that are still unclear, muddied by time and a lack of historical records—by Albert and Winifred Sainte-Marie

Return to text

5. For more on the development of the 1960s singer-songwriter movement, see Bentley (2016) and Murphy (2023).

Return to text

6. For a background on Simone’s song, see Moore (2018).

Return to text

7. See Murphy (2020) for more on “With God on Our Side.”

Return to text

8. In a Village Voice interview (Frank 2017) she explained that “Protest songs spell out a problem, but activist songs spell out solutions.”

Return to text

9. Sainte-Marie released the song “Universal Soldier” on her 1964 album It’s My Way!, but the song gained a wider audience mostly through performances by Donovan, including on his 1965 album What’s Bin Did and What’s Bin Hid. Sainte-Marie (2023b) explains that the song was written “about individual responsibility for war and how the old feudal thinking kills us all.”

Return to text

10. On episode 1 (“Javex, USA”) of the CBC Podcast Buffy (2022), Sainte-Marie discusses difficulties she faced in her childhood, some of which resulted from her being one of the only Indigenous members in her community.

Return to text

11. Warner (2018, 162) explores Sainte-Marie’s reasons for joining the Sesame Street cast as related to a larger agenda for increasing the visibility of Indigenous life in the 1970s. Sainte-Marie “knew it would be a good opportunity to reach millions of young children and their parents with the same message she had been bringing to her concert audiences for years: ‘Indians exist.’”

Return to text

12. On Rainbow Quest (1966b), Sainte-Marie explains to Seeger that children from Indigenous communities are forced into schools far from home and are taught things about Indigenous life that “aren’t true,” representing a “distorted and one-sided view of history of the United States.” She argues that she would “very much like to see the history books corrected so that there’s a justified amount of space given to the true history of the American Indians that hasn’t been told.” This information is provided before she sings “My Country,” which she offers as a detailed perspective from “the other side” of Indigenous life in the United States.

Return to text

13. The Cree Literacy (2021) blog includes a Plains Cree y-dialect translation for the 2017 “My Country” (at Sainte-Marie’s suggestion) alongside annotations and commentary from the singer. The translation was suggested by Sainte-Marie “both as a teaching tool for decolonization, and as a language-teaching tool for speakers of nêhiyawêwin.”

Return to text

14. The formatting and punctuation for these lyrics are taken from Sainte-Marie (2023a); the lyrics have been changed from the website to match her 1966 studio recording performance.

Return to text

15. In the 2017 lyrics, Sainte-Marie retains the general format of the earlier versions. The primary changes are to locations and events. For example, in Verse 3, she changes the reference from “Los Angeles County to Upstate New York” to “Vancouver Island to the Labrador Sea.” In the same verse, she omits the section referencing Uncle Sam and smallpox blankets, adding instead lines in Verse 2 about residential schools and missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Return to text

16. See Hanson (2009) and “Residential School History” (2023) for resources about the residential school system in Canada. For an account by a Cree residential school survivor, see Dixon (2022).

Return to text

17. Sainte-Marie is referencing “Golden Age” Westerns as the primary representation of Native Americans in film. These roles were often filled by non-Indigenous actors. When she was cast on an episode of The Virginian in 1968, Sainte-Marie insisted that Native Americans in the Los Angeles area be hired for the rest of the Indigenous roles on the show; see Humphrey (1968) and Warner (2018, 101).

Return to text

18. The complete lyrics can be found on Sainte-Marie’s official website (2023a). Warner (2018, 92–93) discusses residential schools and how they are represented in “My Country.” One example of broken treaties that Sainte-Marie mentions in this song is the Kinzua Dam project on the Allegheny River that broke the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua and forced around 600 Seneca Nation community members to be relocated. Diaz-Gonzalez (2020) provides a detailed history of the Kinzua Dam and its impact on the Seneca population in New York and Pennsylvania. For more on broken treaties and the Kinzua Dam, see Rosier (1995) and Williams (2007). For a study exploring the plausibility of smallpox blankets and their framing as “contemporary legend,” see Mayor (1995).

Return to text

19. Furthering her educational initiatives, in 1997, Sainte-Marie founded the Cradleboard Teaching Project, which developed elementary, middle, and high school curricula focused on geography, history, social studies, music, and science from Indigenous perspectives. Sainte-Marie (2002) explains this project as a logical extension of her educational activist songs and her tenure on Sesame Street, claiming that she wanted “little kids and their caretakers to know one thing above all: that Indians Exist. We are not all dead and stuffed in museums like dinosaurs.” Concerning Cradleboard (2002), Sainte-Marie explains that they “provided curriculum and cross-cultural connectivity to hundreds of children and sponsored several face-to-face real world meetings between partnering classes of students in grades 5–12, together with their teachers and representatives from four foreign countries to learn Cradleboard Methods for maximizing cross cultural relations.”

Return to text

20. I explore this song in detail in chapter 6 of Murphy (2023). In that study, I use the term “vocal production” to encapsulate the ways that singers create different sounds and effects in their voices; this category includes features like range, timbre, pitch etc. The term “self-expression” captures the sense that in singer-songwriter music, something of the self is being communicated to audiences. In his book Self-Expression, Mitchell S. Green summarizes “Twenty dicta about self-expression” (2007), and several of these apply clearly to singer-songwriter music. Green describes self-expression as showing “one’s thought, feeling, or experience” (Green 2007, 2.1.2), which is “spontaneous or voluntary” (Green 2007, 2.1.6); it may be “directed toward an audience” (Green 2007, 2.1.8), and it express what “can be known by introspection” (Green 2007, 2.1.15). In singer-songwriter performance, artists seem to be conveying unmediated connections with their audiences, facilitated by musical features like direct address, personal pronouns, the absence of amplification, and location-specific features for live performances that foster intimacy between artist and audience. For more on self-expression in singer-songwriter music, see Murphy (2023); for more on singer-songwriters and the impression of intimacy, see Moore (2012, 11) and Bentley (2016, 79).

Return to text

21. “Men of the Fields” was released on this album and could also be framed as an activist song. On Rainbow Quest (1966), Sainte-Marie positions it as a tribute to the “disappearing way of life” for farmers, comparing them to immigrant and Indigenous populations. But this song’s style is more aligned with Sainte-Marie’s folk output than to her impassioned activist-song performance style.

Return to text

22. In Murphy (2023, 154–162) I explore her use of flexible meter (as Ambiguous Meter) in the song “Sir Patrick Spens.”

Return to text

23. In Murphy (2023) I define flexible meter as a metric structure that results from malleable performance timings (like those that arise in singer-songwriter music) that yield “ambiguous or vague meter or vacillations between ambiguous and regular meter

Return to text

24. I see this flexible hypermeter as equivalent to the flexible meter I explore in Murphy 2023. But it is also possible to hear this performance as an instance of flexible meter if it is considered to be in a compound quadruple meter (four dotted-quarter-note tactus beats each subdivided into three eighth notes). I notated the song’s meter as simple triple following the published sheet music in The Buffy Sainte-Marie Songbook (1971), which results in four hyperbeats each subdivided into three tactus beats. It is for this reason that I classify metric flexibility in this song as flexible hypermeter. My use of the term “hypermeter” follows Rothstein (1989, 12); it is defined by “conceptual combination of measures on a metrical basis” including “both the recurrence of equal-sized measure groups and a definite pattern of alternation between strong and weak measures.”

Return to text

25. Sainte-Marie performs the song in G with a capo on the fourth fret so it sounds in B; I have notated it in the sounding key. Following Murphy (2022) and (2023), I include inter-onset (IOI) interval values between hyperbeats in my transcriptions throughout this article, proportionally spaced to illustrate their relative durations within and between performances. In this transcription and those that follow, I decided to notate each vocal arrival point (each hyperbeat) as a downbeat. But in some cases, it is possible to hear Sainte-Marie syncopating her vocal downbeats, creating the type of expressive asynchrony I explore in Murphy (2019).

Return to text

26. In Lost Meter, a “process of interruption occurs

Return to text

27. I encourage readers to conduct the four hyperbeats in each line to feel the challenges to entrainment that Sainte-Marie’s timings present.

Return to text

28. I use the word “heightened” here (and analogous passages of “high emotion”) to suggest that the musical features associated with drama in performance (dynamic increase, more air pressure, intensified vibrato, etc.) are more prevalent, giving the impression of emotional intensity.

Return to text

29. For more on Piaf’s influence on Sainte-Marie, see Warner (2018, 40).

Return to text

30. Malawey (2020, 104) points to qualities like vocal rasp and various signifiers of “unpolished” vocal performance as signifiers of authenticity in popular music.

Return to text

31. Elsewhere, Warner (2018) describes Sainte-Marie’s vibrato as “shimmery” and “deep” (Warner 2018, 58), capable of producing “aftershocks” (Warner 2018, 66) and suggests that this vocal approach is among the reasons fans responded so favorably to the artist. Warner argues that those “who loved her—who understood the thunder in her vibrato and the spark in her words—cried and gave standing ovations at the end of her shows” (Warner 2018, 60).

Return to text

32. “Cod’ine” is an autobiographical song about Sainte-Marie’s unintentional narcotics addiction; see Warner (2018, 64–66).

Return to text

33. Malawey (2020) positions vibrato as a possible marker of vulnerability, especially for untrained singers. Observing Kate McKinnon’ performance of “Hallelujah” on Saturday Night Live after the 2016 election, Malawey states that McKinnon’s vibrato never sounds “deliberate or measured; instead, it combines several seemingly involuntary effects—nervousness, intense sadness, and emotionality—signifying loss of control” (Malawey 2020, 39).

Return to text

34. Eidsheim’s (2019, 170) discussion of vibrato in Billie Holiday’s music finds the singer’s use to be “economical and intentional,” often occurring to highlight rhymes in her lyrics.

Return to text

35. Malawey (2020, 38) explains this in connection to audio signals being amplified and electronically mediated in ways that mean “vibrato is not necessary to accommodate changes in intensity.” Kim Chandler (2014, 42) argues that popular music “requires the subtlest use of vibrato in comparison with other styles of signing,” noting some pop singers (like Chris Martin) who use relatively straight tones. Chandler (Chandler 2014, 49) defines “broad generalizations of stylistic variation” between popular music genres, noting that R&B is “characterized by a relatively light vocal delivery with heavy use of embellishment, melisma and fast vibrato.” She cites Reggae and Indie as genres that uses minimal vibrato, with the former generally including a “medium level of intensity” and the latter “characterized by a rawness & edginess in the vocal delivery” with “quirkiness in the vocals” as a feature embraced by the genre.

Return to text

36. There are occasions in Sainte-Marie’s songs where amplitude vibrato seems to be occurring. In these cases, it is not a pitch change and oscillation that creates vibrato but rather a volume change that produces a “bleating” effect. Thank you to one of the anonymous reviewers of this article for this observation.

Return to text

37. Most of Sainte-Marie’s consistent vibrato last less than a second, making it through only 4–5 oscillations. For the spectrogram diagrams in this study, I use iZotope RX 10, with vocals isolated from the guitar. I determine pitch in semitones approximating from the piano roll. Many thanks to Lori Burns for her suggestions about spectrogram analysis and software for Buffy Sainte-Marie’s music.

Return to text

38. For this example, I use a linear frequency scale to more clearly show the fundamental. All other spectrograms in this study use logarithmic frequency scales. This diagram and those that follow were inspired by the style presented in Rings (2013).

Return to text

39. In general, I do find Sainte-Marie’s vibrato to be marked in comparison with other singers. But within her own performances, the consistent vibrato type is standard, so as a vibrato type it is unmarked.

Return to text

40. This passage spans Baez 1965, 0:40–1:02 in the 68-minute video recording of this live (1965) performance.

Return to text

41. Baez‘s vibrato demonstrates “natural vibrato” (or “laryngeal vibrato”) that Malawey (2020, 38) notes is common in classical and commercial singing. Baez tends to demonstrate the tenets of folk authenticity in different ways: through her sincere and serious delivery to her practice of rejecting commercialism. For more on Baez and the folk scene, see Bentley (2016, 51).

Return to text

42. Further, I classify this as a vibrato type because animated vibrato arises at moments that Sainte-Marie would otherwise likely have used consistent vibrato, like long held notes on vowels or voiced nasal consonants.

Return to text

43. Heidemann (2016) positions vocal fold movements, position of the vocal tract, sympathetic vibration, and breath support as elements of singing that have related timbral classifications.

Return to text

44. See Milius (2021) and passages of Malawey (2020). Nobile (2022) explores the expression of Alanis Morissette’s “single, consistent persona” through her “idiosyncratic vocal delivery” on her 1995 album Jagged Little Pill. This includes investigations of how her voice displays “grief, pain, vulnerability, contentment, love, comfort, guilt, sarcasm, [and] anger.” Burns (2004; 2005; 2010) also explores the relationship between voice and expression in popular songs.

Return to text

45. The producers opted for a close-up angle on Sainte-Marie’s face for most of the performance. My interpretation is that the quavering in her voice indicated high emotional levels that the producers likely heard as signals that Sainte-Marie might cry. They may have chosen this close camera angle as part of an attempt to capture this emotion.

Return to text

46. In the full episode, Sainte-Marie precedes this performance by explaining to Seeger the activist intention behind the song: to provide an Indigenous perspective on United States history.

Return to text

47. On her website (2023b) and in interviews, Sainte-Marie claims to be one of the first people to use the word “genocide” in this context. In the written introduction to the lyrics for “My Country” for Medicine Songs, she states that she wrote the song “in the 1960s before people used the word genocide or acknowledged the indigenous holocaust of the Americas, or the horror of residential schools.”

Return to text

48. One other layer mediating Sainte-Marie’s self-presentation here is the 1960s-era camera designed and calibrated for the show’s white host. This was a prevalent issue with film processing until 1995, when a United States Patent (Van Rooij 1995, 5,428,402) was filed for a “tint detection circuit for automatically selecting a desired tint in a video signal” for film and television cameras (Van Rooij, 1995). In 1966, the cameras would not have been equally well-suited to Sainte-Marie’s complexion as they were to Seeger’s, and these clips alter her appearance. For more on cameras and colors, see Roth (2009).

Return to text

49. Frith also cites Alan Lomax in his discussion of authenticity in self-expressive folk traditions: “Lomax had once written that the ‘authentic’ folk singer had to ‘experience the feelings behind his art’

Return to text

50. Her first album, It’s My Way!, was released in 1964. She released six albums in the 1960s and six in the 1970s. Her output became less regular after that. She released no albums in the 1980s, retiring from music to focus on educational projects. She did write songs during this time, including co-writing the Oscar-winning song “Up Where We Belong” for the movie An Officer and a Gentleman and the music for the 1989 CBC film Where the Spirit Lives about residential schools in Canada. She released only one album in the 1990s (Coincidence and Likely Stories in 1992), one in 2009 (Running for the Drum), one in 2015 (Power in the Blood), and finally her most recent album (at the time of this article’s publication): Medicine Songs (2017).

Return to text

51. The album included only two new songs: “You Got to Run (Spirit of the Wind)” featuring Tanya Tagaq and two versions for “The War Racket” (one with an ensemble and one an acoustic solo). The rest of the songs are from releases prior to 2017: “Starwalker” (Sweet America, 1976), “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin, 1966), a rendition of “America The Beautiful” with new content (music and lyrics) by Sainte-Marie, “Carry It On” (Power in the Blood, 2015), “Little Wheel Spin and Spin” (Little Wheel Spin and Spin 1966), “No No Keshagesh” (Running for the Drum, 2008), “Soldier Blue” (She Used to Want to Be a Ballerina, 1971), “The Priests of the Golden Bull” and “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” (both from Coincidence and Likely Stories, 1992), “Universal Soldier” (It’s My Way!, 1964), “Power in the Blood” (Power in the Blood, 2015), and digital bonus tracks “Disinformation” and “Fallen Angels” (both from Coincidence and Likely Stories, 1992), “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone” (It’s My Way!, 1964), “Generation” (Power in the Blood, 2015), “Working for the Government” (2015 single), and “The Big Ones Get Away” (Coincidence and Likely Stories, 1992).

Return to text

52. The “unplugged” version of “The War Racket” is the only other unaccompanied song on the album. It merges her new activist song style with her 1960s singer-songwriter performance texture.

Return to text