Gestural Temporality in Sciarrino’s Recitativo oscuro*

Antares Boyle

KEYWORDS: Sciarrino, gesture, temporal function, multilinearity, organicism

ABSTRACT: Sciarrino’s writings describe a compositional philosophy that prizes multidimensionality and spatiotemporal discontinuity (1998, 2004). Yet his simultaneous allegiance to teleology, holism, and fractal hierarchies reveals an underlying unifying organicism with which these qualities may initially seem to conflict. I take Sciarrino’s 1999 piano concerto Recitativo oscuro as a case study for examining the composer’s gestural organicism and its various contradictions and double meanings. First, close analysis of the opening piano solo demonstrates how seemingly contradictory aesthetic priorities—organic unity and temporal multiplicity—co-exist within a single passage. Drawing from Kramer’s (1988) concept of “gestural time,” Hatten’s (2004) theory of gesture, segmentation theories, and scholarship on intensity and temporal function, I show how temporal multiplicity in the piano solo arises through conflict between gestural energetics and contextual segmentation. I then expand my analysis to the full concerto, arguing that the orchestra’s cyclic and naturalistic sonic ecosystem causes the piano gestures to take on representative functions in addition to their energetic syntax, creating what Sciarrino (2001) calls “dimensional intermittence” as they reference distant temporal realms both within and beyond the concerto. I conclude by arguing that while the intensity profile of the earliest gestures and phrases is eventually reproduced across the form of the entire work, the concerto’s form nevertheless resists reductive understanding. Instead, listeners are invited to hear form through the complex mechanics and idiosyncrasies of “gestural behavior” (Sciarrino 1998).

DOI: 10.30535/mto.29.4.9

Copyright © 2023 Society for Music Theory

Example 1. Gesture “X” at the opening of Recitativo oscuro (0:00–0:08): the notation conveys two pianistic motions, but the two cells combine into a single aural gesture

(click to enlarge and listen)

[1.1] Salvatore Sciarrino’s 1999 piano concerto, Recitativo oscuro, recorded by the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI under Tito Ceccherini (2008), opens with a propulsive gesture from the soloist (Example 1).(1) The pianist, Daniele Pollini, performs two spiky yet slightly ragged cluster chords, the second higher and louder than the first. This dramatic maneuver emphatically declares the start of the concerto, yet propels listeners into a sonic void—an abrupt cessation of action in which the piano strings thrum in hushed anticipation. The orchestra responds tentatively, bouncing bow sticks off strings and tongues against reeds to create an insect-like rustling.(2)

[1.2] The piano’s dramatic opening gesture, which I will call “X,” is created through a distinctive performance technique in which the pianist’s right hand rapidly strikes three ascending white keys while the left hand traces an intersecting journey across three descending black keys.(3) The black key/white key distinction, while felt kinetically by the pianist and visually apparent to a score-reader, is lost in the aural effect. Likewise, at Pollini’s tempo, the notated rhythm (in which each cluster chord consists of three distinct dyads) is heard only in the slightly blurred edges of the clusters and ultimately subsumed into the broader ascending gesture. The choreography and its sonorous effect direct my analytical attention to the interface of biological and mechanical, as the pianist’s hands meet the keyboard, or digital versus analog, as individual notes fuse into clusters and clusters into larger gestures. These fuzzy binaries become zones of productive tension within Sciarrino’s distinctive brand of organicism.(4)

[1.3] The distinctive gestural quality and wholeness of X results from its increasing intensity in two parameters, loudness and pitch height, and the near-silences that bound it on either side. Robert Hatten (2004, 94) describes gestures as “perceptually synthetic gestalts with emergent meaning”: some continuity of energy integrates consecutive events into a unified whole, and the communicative potential of the resulting holistic gesture is greater than that of its individual components. Hatten also defines gesture as a “significant energetic shaping through time” (95). Following Hatten, throughout this paper, I use the terms “energy” and “energetics” to refer to the complex sensations of motion (and related metaphors such as speed, force, and direction) that listeners may ascribe to musical change—particularly intensity change, as developed in Section 2.(5)

[1.4] Sciarrino’s own writings highlight the significance of holistic gestures and their connection to energetic shaping within his compositional practice. In his book Le figure della musica da Beethoven a oggi (henceforth Le figure), developed from a set of lectures he gave in 1992, he frames his ideas as a “future theory of form as analysis of gestural behavior” (translated in Song 2006, 5).(6) In a later essay on his compositional philosophy, he writes:

Meaning and representation finally unite the various components of a language and constitute its most intimate energy. Now, two apparently opposed aspects shape this music: the abstract construction, and at the same time the iconic immediacy, an indication [indice] of the newly rediscovered relationship withnature. . . . this language is based upon the relationship of figures and no longer upon predetermined pitches, upon sounds in motion and not on already givenintervals. . . Never in my life have I put together pitches, but rather I have thought of sonic figures. (Sciarrino 2004, 54)(7)

In his customary poetic style, the composer here highlights how “figures,” understood in terms of their kinetic properties (“sounds in motion”), contribute to the construction of meaning through their intrinsic energy. The passage emphasizes the importance of readily perceptible structures in his music, a theme that recurs throughout Sciarrino’s writing. In the essay, he goes on to criticize analysts who overly attend to the minutiae of individual pitch relationships rather than larger gestures, citing the laws of gestalt perception.(8) He concludes by reaffirming the organicist underpinnings of these concepts: “A music of wholes [insiemi]. What are the implications of this

[1.5] Sciarrino’s discussion of gesture also highlights an opposition between something like syntax (“abstract construction”) and semantics (“iconic immediacy”), suggesting opaquely that gestures can unify these two distinct elements of musical language. His use of the terms “icon” and “index” may suggest an engagement with Charles Peirce’s semiotic theory.(10) Although I do not make use of Peirce’s complex theory in any depth here, I retain the term “icon” for a sign that signifies through similarity or resemblance.

[1.6] In the staged drama of a concerto, with its built-in potential for dialogue and agency, the communicative potential of gestures is particularly overt.(11) Gesture X, as the first utterance of the soloist, is ripe for interpretation. Its escalation of intensity seems to promise the start of something big(12)—the soloist perhaps announcing: “I am here, I have begun”—only to be answered by crickets. Gesture X’s implication of an opening temporal function matches its prime position within the global context of the concerto, but at the local level, it leads to an abrupt ending. Thus opens a two-and-a-half-minute piano solo in which animated gestures abound with such contradictions and double temporal meanings.

[1.7] Throughout the solo that follows, gesture X is both ubiquitous and generative of larger forms and trajectories, serving as a kind of postmodern Grundgestalt derived from pure physicality and motion. To describe this tight motivic integration, I have invoked a term associated with the early–twentieth-century organicism of Arnold Schoenberg. It refers to a principal motive or “basic shape” that served as a source of coherence for an entire work, generating new content both through repetition and development or through composing out at higher structural levels.(13) Almost every sonority in the solo is created through X’s distinctive performance technique, that is, the layering of three-note white-key and black-key scale segments performed so quickly that they blur into a single cluster.(14) More significantly, as I demonstrate below, phrases and larger sections of the solo imitate and elaborate upon X’s emergent gestural shape and meaning.

[1.8] The highly integrated motivic construction of the piano solo is consistent with Sciarrino’s organicist leanings, already mentioned above. In addition to holism, Sciarrino’s physical and physiological metaphors often celebrate a hierarchy characterized by congruence between different structural levels.(15) For instance:

Since [my] music materializes in clusters of sounds that are already themselves complex, it resembles more than a little bit the physical world, whose atoms mirror the larger gravitational systems. Science and fractal theory are today rediscovering the coincidences of micro and macrocosm. Similarly, [my] music is configured as a plurality of groupings. (Sciarrino 2004, 54)(16)

Sciarrino explicitly connects this hierarchical organicism to linear temporality, stating that “the relationship between the individual figures, or the groupings of figures into logical units of various sizes, are of a functional nature, in other words, teleologic” (2004, 54).(17)

[1.9] Despite these assertions, Schoenbergian coherence and unity might seem aesthetically old-fashioned or out of place in Sciarrino’s avant-garde sound world.(18) In fact, privileging a unifying teleology expressed through continuity of gesture would seem to contradict Sciarrino’s self-stated allegiance to multidimensionality. One of the compositional devices described in Le figure (and alluded to in the program note for Recitativo oscuro, discussed below), “windows form,” refers to “discontinuity of the spatial-temporal dimension” (translated in Song 2006, 19). Using Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gruppen as an example, Sciarrino explains its effects as follows: “the related and non-contiguous blocks connect in the memory, creating, through the intermittence, a polyphony of relationships” (Song 2006, 21). Sciarrino specifically grounds this aesthetic in the temporality of contemporary experience, stating, “today, time does not flow as it did in the past: it has become discontinuous, relative, variable” (Song 2006, 19). “Windows form” is named for the late–twentieth-century experience of encountering information inside the frame of a computer processing window, and Sciarrino references the temporal juxtapositions caused by changing television channels or viewing photographs as other examples involving modern technology (Sciarrino 1998, 97). Analysts of Sciarrino’s music have described this aspect of his aesthetic as “a plurality of perceptible dimensions” (Song 2006, 22) or “a search for multi-dimensionality” (Giacco 2001, 66–67, trans. Song 2006, 22).

[1.10] Recitativo oscuro serves as a provocative case study for examining the dichotomies and double meanings inherent in Sciarrino’s gestural organicism. My analysis traces a trajectory from local gestural syntax to the more complex contradictions and associations raised through representation. First, in Section 2, I provide a framework for understanding how a gesture’s intensity profile can signal temporal function. This supports an analysis of the opening piano solo in Section 3, which demonstrates how seemingly conflicting aesthetic priorities—organic unity and temporal multiplicity—coexist within a single passage, as gestural energetics becomes the key force through which we experience temporal pluralism.(19) Finally, in Section 4, I turn to the rest of the concerto to examine how gestures are interpreted and reinterpreted iconically within a more complex sonic ecosystem. Throughout the concerto, listeners are invited to ponder the identity of gestural entities and their components, probing the surprisingly slippery boundaries between analog and digital or between animate and inanimate.

Gestural Time and Segmentation

[2.1] In music written within a particular style, familiar gestures can perform a syntactical function by serving as formal signals—for instance, a recognizable cadential formula signals the temporal function “ending.” Theorists such as Leonard Meyer (1973, 212–13; 1979), Jonathan Kramer (1973; 1988), Janet Levy (1981), and Robert Hatten (2006) have explored the effects that arise when a gesture’s conventional temporal association conflicts with its sequential position, as when a cadence with movement-ending finality occurs in m. 10 of Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 135, mvt. I (Kramer 1988, 150). For Kramer, such gestures’ functional associations create an alternative temporality that coexists with that of their ordering in real time: in one sense, the cadence of m. 10 is the true ending of the Allegretto, while in another, we know the movement has only just begun. Kramer called this alternative temporality “gestural time.”

[2.2] Kramer’s concept of gestural time was refined through an important philosophical dialogue with Judy Lochhead (1979).(20) Lochhead first clarifies the distinction at stake through a useful metaphor:

After rising, one usually eats breakfast. This meal may include coffee, toast, eggs, etc. The act of “eating breakfast” is usually associated with the morning, but it is possible to “eat breakfast” at any time of the day. The phrase has two possible meanings here. First, it may mean eating a meal in the morning; second, eating the types of food associated with the morning meal. (Lochhead 1979, 4)

Lochhead terms the first meaning “contextual” temporal function. Here, “breakfast” refers strictly to an event occurring at a time that we recognize through its surrounding context—in my sequence of daily events, it generally occurs sometime after the sun rises and before I begin work. In a musical analogy, we know Beethoven’s op. 135 has just begun because the performers have only recently taken up their instruments and begun to play; similarly, we might know that we are hearing the beginning of the development because something we recognized as the exposition’s closing theme has just finished. Lochhead’s second meaning is what I will call (after Kramer) “gestural” temporal function: thinking of your 6:00pm meal of eggs and toast as “eating breakfast” is like hearing the opening theme of op. 135 as an “ending.” We recognize these events as emblems of their standard temporal function due to their gestural (or culinary) content, even though there is a contextual mismatch. Lochhead goes on to clarify that gestural time cannot be considered “non-linear” because gestural temporal functions depend upon the “aesthetic of cause-and-effect continuity” of a linear temporal model (1979, 8). Gestural time, then, depends on the teleology that Sciarrino references when he describes the “logical unity” governing the disposition of figures. When gestural time conflicts with context, the result is multi-linearity.

[2.3] In their discussion of misplaced temporal signals, Kramer and Levy both focus on the holism of gesture. For Kramer, the meaning of these temporal signals is embedded in “the shapes and qualities inherent in entire gestures but not in the individual notes and durations that make up those gestures” (1988, 151), whereas for Levy “it is the particular interaction among parameters that creates the gestural types” (1981, 355). In other words, the temporal function of gestures is emergent, just as Hatten—and, it would seem, Sciarrino—argue of gestural meaning more broadly.

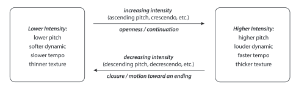

Example 2. Relationship between intensity change and temporal function, with examples of relative low/high intensity mappings

(click to enlarge)

[2.4] While the gestural signification that Kramer, Lochhead, and others describe in Haydn and Beethoven relies on the highly codified syntax of the Classical style, Kramer acknowledges that there are “a few fundamental conventions in Western music that transcend style” (1988, 160). He does not explore their implications for gestural time in less conventionalized styles, but other scholars have probed the relationship between perceived intensity or energy level and temporal function. Some sonic states (low pitch height, quietness, slow tempi, purer timbres, thinner texture) are typically perceived as low intensity, while their opposites (high pitch height, loudness, fast tempi, complex timbres, thicker textures) are perceived as high intensity.(21) Coordinated change in intensity levels over time can create a holistic gesture—Hatten’s “significant energetic shaping” (Hatten 2004, 95)—with temporal implications: processes of decreasing intensity imply impending closure, whereas processes of increasing intensity suggest openness and continuation (Example 2). In this way, a gesture can play a purely syntactic role even without the established conventions of style.(22)

[2.5] While processes of intensity change shape a gesture through implied temporal function, they cannot create firm boundaries. For instance, a decrescendo or slowing tempo can imply impending closure, but there is no specific state of quietness or slowness that indicates closure has definitively been reached. Leonard Meyer described this phenomenon in his famous distinction between so-called primary and secondary parameters (1989, 14–16, 208–11). Meyer designates as “primary” those musical elements that create “articulated hierarchical relationships” (209) through recognized syntactical categories and well-defined methods of closure. (Meyer named melody, harmony, and rhythm as primary.) By contrast, “secondary” parameters, such as loudness or textural density, are elements that “tend to be described in terms of amounts rather than in terms of classlike relationships” (15). Although aspects of Meyer’s distinction have proved problematic—e.g., the implied value judgment; the implication that complex higher-level relationships such as “melody” and “rhythm” can be separated and measured—his observations about the relationship between “classlike categories” and hierarchal forms remain astute. Relationships of intensity, by definition, are described in comparative quantities. The temporal functions illustrated by arrows in Example 2 are processes that point toward or away from boundaries, not discrete boundary events themselves.

Example 3. Recitativo oscuro, mm. 1–12 (0:00–0:46), piano solo with segmentation (occasional orchestral parts in this section are not shown)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.6] In the absence of style-specific conventions, boundaries are generally intuited based on segmentation criteria such as rest, change, and repetition.(23) Rests (or long temporal gaps between sound onsets) are consistently recognized as among the strongest grouping criteria,(24) and they play an important role in segmenting Recitativo oscuro’s opening piano solo.(25) Theories of segmentation based in gestalt psychology also recognize that substantial change in some musical parameter can indicate a segment boundary. In the piano solo, low level segment boundaries are formed by changes in pitch contour, while stronger disjunction results from occasional extreme register change. Finally, repetition can suggest segment boundaries, although its perception depends on a larger temporal context.(26) Within the context of the piano solo and its organicist procedures of replication and variation, repetition becomes especially important to the perception of formal units, confirming lower-level segment boundaries proposed by rests and creating higher-level phrase and section boundaries. Example 3 demonstrates the role of these criteria by providing a segmentation of the beginning of the piano solo that is grounded in my own hearing.(27)

[2.7] The segments and phrases depicted in Example 3 (and similar units in the rest of the piano solo) provide a temporal context in which gestures act, and in which the multiplicities of “gestural time” can arise.(28) In the analysis that follows, I explore the multilinearity that results when processes of intensity change—the same “energetic shaping” that sculpts Sciarrino’s holistic gestures—signal temporal functions that conflict with their position in relation to segment and phrase boundaries.

Gestural Time and Organicism in the Opening Piano Solo

[3.1] Describing the experience of a conflict between a gesture’s temporal signification and its context, Kramer writes that “we understand when a gesture seems to be misplaced in absolute time, and we await the consequences of this misplacement” (1988, 161). Similarly, for Hatten, these moments are significant because of their “creative yield”—that is, their potential for expressive meaning (2006, 66).(29) In the pregnant near-silence that follows the initial statement of gesture X, I experience the first sensation of temporal multiplicity, suggesting that attending to gestural shaping and temporal function may prove a rewarding listening strategy for the music to come. In the analysis that follows, I describe how gesture X is spun out organically to generate longer segments, phrases, and sections of the piano solo, which initially reproduce its temporal contradictions at larger scales. I then show how, as the solo continues, other gestures with contrasting temporal implications emerge, introducing additional conflicts between gestural time and segmentation while also destabilizing monolinear temporality in new ways.

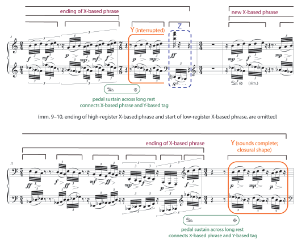

Example 4. First phrase of the piano solo

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.2] In the opening phrase (Example 4), both segments and phrase replicate the shape of gesture X—an intensity profile that continually opens outward, suggesting continuation, yet leads to an ending in context. Gesture X accumulates additional clusters to form longer segments. These segments roughly imitate X’s intensity profile, ascending in pitch height and becoming louder, and the initial cells of X itself or slight variations conclude each segment.(30) At a higher level, the entire phrase mirrors X’s energetic shape: it gains intensity through acceleration, as the rests between segments get progressively shorter and surface rhythms speed up during the final cells. The opening phrase thus embodies Sciarrino’s “coincidence of macro and microcosm” even as it complicates the simple beginning–middle–end paradigm of linear teleology.

Example 5. Recitativo oscuro, mm. 13–16 (0:47–1:03), piano solo only

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.3] Conflicts between energetic shape and segment boundaries continue to characterize the passage. A repetition of the opening phrase (see Example 3, mm. 8–10) and a short phrase based on a low-register version of gesture X (m. 11) also build continuously to their finish. In the phrase beginning in m. 13 (Example 5), X serves a more conventional phrase-opening function. Here, its gestural promise of continuation is realized at the phrase level—rather than insistently serving as a segment ending, as it has thus far, it is now treated in a quasi-sequential manner. The “sequencing” effect emerges from the repeated presentation of two-cluster segments, each with the same pitch and dynamic contour as X, and each heard on lower pitches and at a softer dynamic than the last. After reaching an intensity nadir at a muddy low-register ppp, the phrase reverses trajectory, gaining energy through ascent, increasing loudness, and accumulation of additional clusters, rather like the opening phrase did.(31) The holistic intensity profile of the phrase in mm. 13–16 ultimately inverts the conventional arch shape, beginning with energy loss and then regaining momentum to go out with an X-like bang.

[3.4] Interspersed with the X-based phrases in the opening measures of the piano solo are two other gestures, “Y” and “Z,” with distinct temporal implications. In his program note for the piece, Sciarrino evokes the spatiotemporal discontinuity of his “windows form” and its roots in modern life, writing:

Dimensional intermittence is an essential concept for understanding this type of form, where parallel musical streams seem to interfere with one another. A concept that should be familiar, given the ease with which distant beings and events come into contact today. (Sciarrino 2001, 185)(32)

Gesture Z (see Example 5 or Example 6) is an example of such “intermittence.”(33) It consists of a single high-intensity event, and therefore lacks a temporal gestural shape based on intensity change, but it is kinesthetically distinguished for the pianist by the motion of the fingers and arms—the hands, previously entwined for the performance of X-like clusters, disentangle and distance themselves to sound notes at registral extremes. Its disparate pitch content prevents any sense of gestural continuity with the clusters that otherwise dominate the solo. Gesture Z occurs four times in the first twenty measures, at unpredictable moments; and with its foreign material and aggressive dynamic, it always feels like an interruption from another plane—a hammer that falls without regard for any presently unfolding musical processes.

Example 6. Gesture “Y” emerges in mm. 1–12 (0:16–0:24 and 0:37–0:47)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.5] Gesture Y initially sounds following the final sustain of two X-based phrases (Example 6, m. 6 and m. 12; refer back to Example 3 to see these excerpts within a broader context). It uses the same unique pianistic syntax as X, and is thus in one sense a variation of the concerto’s original gesture, but its rhythmic and energetic features set it off as a new idea. It lacks a gestural connection with the preceding material due to the sudden change in dynamic and register in addition to the long rest. The events of Y also propose a dramatically different “tempo”: while the cells of the preceding X-based phrase have followed one another quite rapidly, the first cells of Y precede more slowly. Pollini performs the clusters of Y with great delicacy, bringing out its distinct gestural identity from its beginning. On Y’s first, partial presentation (m. 6), its first two clusters are interrupted by gesture Z. The second statement of Y material (m. 12), however, sounds complete and conclusive: its three clusters are followed by a rest, and unlike X-based segments and their larger phrases, its gestural shape suggests closing function by decreasing in intensity (an overall pitch descent and decrescendo into the final cluster). Thus, the two gestures, while sharing a common origin and language, are distinguished by rhythm and by pitch and dynamic contour, which result in contrasting intensity shapes.(34)

[3.6] Contextually, the first two iterations of Y each follow an X-based phrase, suggesting a higher-level ending—a Y-based tag that responds to the exuberance of the X-based phrases. While various factors—the long interval between the final X-segment cluster and the onset of Y, the repetition of the first X-based phrase without Y, the newness of the Y material—support hearing a phrase boundary following the final X-based segments in m. 5 and m. 11, the pedal sustain of the final X-segment also creates a bridge between the X-based phrase and the new Y material. Indeed, throughout the piano solo, pedal sustain is used almost exclusively across the phrase boundary between X-based phrases and Y-based tags, strengthening their expected pairing while subverting any expectation of a more conventional association between sustain/decay and significant phrase endings.

Example 7. Recitativo oscuro, mm. 18–21 (1:07–1:21)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.7] Gesture Y’s high-level closing function is consistent with its gestural properties when heard in its complete form in m. 13, but Y soon reveals its own temporal contradictions. The next time we hear it (Example 7), Y is extended, functioning most prominently as an opening, not a close. Here it is followed closely by new clusters, the first of which repeats Y’s final cell, and the remainder of which continue the overall downward pitch trajectory, spinning Y’s materials out into a longer phrase. The phrase loses intensity, but rather than regaining energy to mimic the inverted arch of earlier phrases, it is interrupted by a sudden return of X in m. 21.

[3.8] Although the rests that follow X in m. 21 would suggest grouping it with the Y-based tag that started in m. 18, this X in fact serves as a high-level beginning, setting off a varied repetition of the entire solo up to this point. The primary segmentation criteria for the passage, rests and repetition, are here in profound conflict for the first time, with rests suggesting a boundary after X and repetition (as well as registral disjunction) proposing a boundary before it. The fact that this conflict occurs at the moment of an upper-level formal boundary highlights the temporal and functional uncertainties signaled from the very beginning: is X a beginning or an ending? Example 7 does not include a definitive segmentation, since segments are somewhat ambiguous even at lower levels, but highlights the span of upper-level conflict.

[3.9] In summary, in the first half of the piano solo, both X and Y seem to serve the function implied by their gestural shape at higher levels, while contradicting that function at a lower level. Gesture X, with its implication of beginning, initiates the concerto and the piano solo’s larger sections, despite insistently ending its early segments and phrases. Gesture Y, with its potentially closural shape, nonetheless spins out a new phrase in mm. 18–21—but that incomplete-sounding phrase serves as a higher-level ending in context.

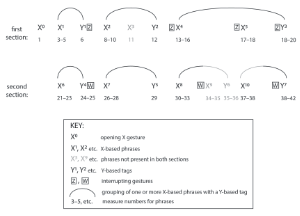

Example 8. Large-scale repetition in the piano solo

(click to enlarge)

[3.10] The second half of the piano solo (mm. 21–42) recapitulates the thematic processes of the first half (mm. 3–20), with its pairing of X-based phrases and Y-based tags. (The fact that the dramatic opening gesture of m. 1 is not included in this repeat supports interpreting it as an autonomous and portentous symbol, a microcosm of what is to come.) Example 8 diagrams the relationship between the two halves of the solo, vertically aligning corresponding phrases. Although there are some broad structural differences between the two sections—each contains one or two phrases omitted from the other—two smaller-scale variations have more significant implications for temporal perspective.

Example 9. Y-based tags in the second half of the piano solo (1:25–1:38, 1:44–1:56, 2:15–2:25, 2:25–2:43)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.11] First, while the X-generated phrases are still followed by Y-based tags, the duration of the Y-based material in each case is unpredictable. Example 9 illustrates by showing each Y-based tag within its surrounding context, labeling phrases and tags using the same numbering system as Example 8. While Y5 (m. 29) states the closural-sounding three-cell version from m. 12, the others (mm. 24–25, 35–36, and 38–41) continue past that point, each spinning the Y material out into a longer phrase, as occurred in mm. 18–20, with some elements of increasing intensity within their overall low-level energy state.(35) Gesture Y, therefore, is never able to step into the role of unambiguous closing gesture, instead embracing an equivocal phrase-opening function. The final tag, Y7, continues longest of all, eventually giving way to an X-like escalation of energy that ends the solo and thus replicating the full inverted arch shape of earlier X-based phrases.

[3.12] Second, in the repeated section, gesture Z is now replaced by a gentle, pp gesture (“gesture W”; see Example 9). Like Z, W separates the pianist’s hands in order to strike keys at registral extremes, and thus both feels and sounds like material from another world compared to the rest of the solo. W and Z interruptions occur in approximately the same places within the two sections (see Example 8), and they serve the same dramatic function: they provide interference in the form of distinctly misplaced material. Yet without the ff dynamic, W now lacks the affective implication of Z. The seeming fragility of the new version belies its power to disrupt and resist integration into the surrounding X- and Y-based phrase processes.

[3.13] My analysis has shown that the piano solo that opens the concerto is animated throughout by the inversion of expected relationships between gestural shaping, communicated by changing intensity levels, and contextual segmentation. Its fractal-like structural organicism, replicating the shape of gesture X at multiple formal levels, thus exists in tandem with a subversive multilinear temporality. As its lively gestures, phrases, and sections replicate and transform, this multilinearity extends beyond the single-level temporal conflict seen in the opening phrase, reverberating across formal levels. I will argue in the next section that at the formal level of the full concerto, the poetics of gestural syntax are further complicated by those of gestural representation, as the expanded context begins to invite iconic interpretations.

Gestural Energetics and Representation in the Full Concerto

Example 10. Elements of the cycle in Recitativo oscuro, which repeats with variations and occasional disruptions approximately

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.1] Throughout the piano solo, the orchestra only offers muted and amorphous interjections—soft brushing, scraping, clicking, or breathing sounds; ominous thuds; high-pitched shimmers. When the solo ends, these mysterious orchestral sounds coalesce into a coordinated set of repetitions (Example 10) that ultimately lasts for about twelve minutes, the majority of the concerto’s duration.(36) Persistent throughout most of this time is a soft, somewhat irregular pulsation articulated most audibly by percussion and tongue stops in the winds.(37) The repeated rhythm in the bassoon parts gives each attack a diffuse and complex edge similar to that of the piano solo’s clusters. Approximately every thirty seconds, woodwinds enter the perceptual foreground with a long slow trill that gradually swells and dies away, ending in a gentle flurry of descending tremolos. The regularity and smoothness of this intensity curve supports a sense of global cyclic repetition anchored by the woodwinds’ central trill, which is sometimes decorated by echoes or anticipations. In the temporal gap between woodwind swells, less predictable materials such as solo piano or brass interjections may occur. The gradual intensity changes, woodwind anticipations, and variations encourage hearing in the cyclic repetition a continuous ebb and flow, rather than a clear recurring unit with articulated boundaries.

[4.2] The slow cyclic material contrasts with the impulsive directed motion of the piano solo. While energetic shaping is still key to hearing the cycle’s undulating periodicity, its gestures seem to occur on a geophysical scale rather than a human one. In contrast to the piano solo’s frenzied accelerations and unpredictable decelerations, the cycle’s regularity evokes the inexorable change of the seasons. The quality of the sounds themselves also support an ecological interpretation of the orchestra’s role, although not necessarily one grounded in the natural world—Sciarrino’s own program note for the piece references in turn mythology (albeit somewhat obliquely), dreams, and a “monstrous landscape” (Sciarrino 2001, 186).(38) While the piano’s sonorities are traditional enough that they can be readily attributed to the soloist, the orchestral instruments often employ extended techniques that obscure the sounds’ origins. As Aaron Helgeson has pointed out, this defamiliarization can upset our settled habit of accepting musical sounds as abstractions, inviting us to seek instead environmental sources (2013, 11). At the same time, the use of unfamiliar instrumental sounds makes it more difficult to separate the utterances of individual members of the orchestra, allowing them to instead fuse into a complex and enigmatic sonic ecosystem.(39) I find that the interpretations that come to mind are those that retain a sense of mystery and strangeness—the buzz and swoop of prehistoric insects, the heavy footfalls of unseen animals in the brush, the snoring of mythological beasts.

[4.3] This new reality demands reinterpretation of the pianist’s opening soliloquy. Alone, the piano solo called for understanding as abstract music making, through its own internal gestural syntax. Now, with the curtain widened to reveal the rest of the stage, the soloist becomes a character within a broader context. The immediate impact is that, against the environmental backdrop, the piano music becomes more explicitly agential, perhaps even human. While the blunt piano clusters may initially have come across as crude and mechanical, they are now reframed as the improvisatory speech of a willed individual within an immense and mysterious soundscape. The vastness of the territory is communicated by the piano’s surprisingly peripheral role: throughout the cyclic passage, it occasionally interjects, but never regains its status as lead voice or upsets the orchestra’s steady pulsations.

Audio Example 1

[4.4] Sciarrino’s “dimensional intermittence,” introduced in the piano solo with the interruptions of gesture Z and W, now manifests on a much broader scale. It is most apparent in several explosive passages that momentarily distract from the steady ebb-and-flow of the cycle. These passages (beginning at m. 58/3:47, m. 98/7:15, and m. 139/10:44) involve much of the orchestra in outbursts of intense activity, yet ultimately fail to disrupt the regular cycle, as the woodwind trills that serve as cyclic markers continue to sound approximately every thirty seconds. Audio Example 1 (mm. 94–104/6:54–7:45) excerpts the second of these outbursts within the context of the surrounding cyclic material.

Audio Example 2

[4.5] Two distinct types of piano interjections also create more subtle intermittence through reference to another time.(40) The first type quotes the opening solo or mimics its techniques. Where earlier the piano’s gestures could be interpreted syntactically, as pure energetic shapes, they now become iconic—flashbacks or isolated shards of memory. This type first occurs in mm. 85–88. The next instance, heard shortly thereafter (mm. 92–93), incorporates an explicit echo effect never heard in the solo proper, a metareference to the broader déjà vu. Audio Example 2 (mm. 81–94/5:45–6:58) includes both interjections in context.

Example 11. Diatonic and quasi-diatonic piano part in the first outburst passage, mm. 98–99

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.6] The second type of referential piano interjection occurs during the outbursts. Here, the pianist sounds a joyous but chaotic string of quartal harmonies—thick stacks of fourths that ring out with an unabashed diatonicism. These are soon interspersed with harmonies whose manner of presentation (intersecting left- and right-hand runs) resembles that of the solo’s clusters, but whose pitch content is quasi-diatonic. Within the pitch context of Recitativo oscuro—a composition not merely post-tonal, but effectively post-twelve-tone-equal-temperament—such a reference can only point beyond the boundaries of the work itself, gesturing broadly at tonality with a kind of naive nostalgia. These gestures, too, are iconic, but on a different temporal scale than the references to the solo. Example 11 illustrates the beginning of the second of these interjections, which can be heard in context in Audio Example 1.

Example 12. Solo piano in mm. 113–114 takes on greater continuity of orchestral cycle

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 13. Dialogues between piano and orchestral instruments

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[4.7] Thus far my analysis has focused on the speech and actions of only a single character, but the title, translatable as Mysterious Recitative, suggests the potential for conversation. Sciarrino references this explicitly in his program note, writing, “The solo piano stands out as if it were a speaking character, and hints at previously inconceivable dialogues between keyboard and bursts of strongly naturalistic sound” (2001, 186).(41) And indeed, the piano and orchestra eventually begin to interact. In an early and subtle instance (Example 12), piano solo material takes on the enhanced continuity of its cyclic surroundings, losing the individual decrescendos that previously served to punctuate each cluster in favor of a more expansive undulation of intensity. Later, the soloist engages in an explicit call-and-response with the trumpet and then with the woodwinds (Example 13). What makes these dialogues “inconceivable” is that they reach across the intermittence: parallel musics, each previously representing distinct temporalities, now begin to affect one another.

Example 14. A dialogue between solo cello and solo bass in the sillabazione scivolata style

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.8] Finally, nearing the end of the cyclic material’s reign—perhaps even triggering it—entirely new voices enter. In mm. 183–85 (Example 14), a solo bass and cello engage in a strange conversation. They trade soft melodic utterances, each a delicately shaped < > gesture encompassing one or more glissandi of unpredictable pitch and speed. This is a minimal version of Sciarrino’s sillabazione scivolata (“gliding syllable articulation”), a distinctive style the composer initially developed for voice as an imitation of natural speech, and which has since become prominent in his writing for strings (Saxer 2008; Boyle 2021).(42) It is the only instance in the entire composition in which instruments besides the piano are given material that might plausibly be called “melodic,” and it upends interpretation of the drama and its characters one final time—perhaps these are the living and speaking characters, and the piano, with its clumsy clusters, is merely a mechanical imitation of life after all. The extremely soft dynamics would seem to belie the novelty and importance of this material, yet paradoxically require a listener to focus with great intensity to make out the sounds at all.(43)

Audio Example 3

[4.9] When the cycle finally breaks off (m. 185/14:47), the concerto’s final section instantiates an unprecedented escalation of energy. It begins with a passage reminiscent of the earlier outbursts—suggesting that those moments of intermittence were in fact looking forward within the time of the concerto even as their nostalgic content pointed to the past. Soon orchestral forces and soloist coordinate in the presentation of much faster cyclic repetitions (mm. 191–200/15:12–15:46). This gives way to a final passage in which the orchestra is reduced to a basic pulsation (mm. 201–208/15:48–end), between pulses of which the soloist squeezes in a frenzy of diverse material. Audio Example 3 (15:33–16:00) provides a representative excerpt of this passage.

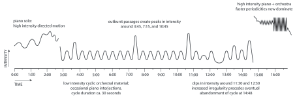

Example 15. Visual representation of intensity and cyclic material in Recitativo oscuro as a whole: form mirrors inverted arch shape of individual phrases from the opening piano solo

(click to enlarge)

[4.10] By ending with this high intensity music, the concerto replicates on a larger scale the gestural temporal contradictions of the piano solo. The inverted arch shape that pervades the solo—in which phrases end at high intensity and often dip in their middle—is ultimately reproduced in the form of the entire work. Example 15 provides a visual representation of this, mapping the concerto’s form as intensity (Y-axis) across time (X-axis). Here, holistic intensity levels are based on my own subjective assessment of factors discussed throughout this article such as dynamic and tempo. The qualities of sustained linear temporality described in my analysis of the solo also contribute to my perception of it as more energetic than the cyclic middle. Largely periodic passages are shown with wave shapes, with the outburst passages and significant variations represented by visible irregularities in the waves. Although this speculative diagram simplifies a more complex reality—most significantly, by omitting contrast between orchestral/solo voices—it captures the unusual proportions and energetic shape that characterize Recitativo obscuro’s unique form.

Example 16. The clearest reference to X and Y material after the solo occurs in the final moments of the concerto

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.11] In the final moments of the ending passage (Example 16), the piano sounds the clearest reference to the opening solo yet: X- and Y-based material, connected by the familiar sustain that linked X-based phrases with the Y-based tags throughout the solo. Here, only the final cell of X is heard, and while Y attempts to continue beyond its initial three clusters, it is quickly overpowered by the orchestra. In a classic organic form, this return to earlier material might be heard as an agent of closure, but here its function is more complex. Along with any feeling of closure comes lived knowledge of the original context, in which the Y-based tags consistently struggle to reach a definitive close on a local scale. Moreover, the reduction of the material to such a short form highlights most of all the in-between moment of the pedal sustain, a liminal zone with ambiguous temporal repercussions. Ultimately, interpretation of this final quotation remains open to multiple possibilities, just as the segments and phrases of the solo itself.(44)

Conclusion

[5.1] Recitativo oscuro demonstrates how Sciarrino’s organicist principles of gestural holism, teleology, and motivic unity coexist with a temporal multiplicity that reflects modern life. The pianist’s opening recitation exploits a limited palette of self-replicating cells to create a pure gestural syntax grounded in the manipulation of intensity levels. In the solo, this gestural syntax conflicts with contextual segmentation to yield a dynamic multilinearity in which endings are also beginnings and vice versa. Once the concerto expands to encompass the full orchestra and the solo’s linear temporality is suppressed by cyclic material, gestures begin instead to function iconically, referring to past and future events to generate Sciarrino’s distinctive “intermittence” of temporal dimensions and to script “inconceivable” dialogues.

[5.2] Considered as an emblem of the concerto genre, Recitativo oscuro reveals a delicate balance of old and new. Its inverted arch shape and long cyclic middle is a radical formal choice in a genre that lends itself to teleologic narrative arcs featuring the soloist as protagonist. In Sciarrino’s novel concerto form, the soloist’s contributions are disproportionately weighted toward the opening solo, and intermittent and disconnected thereafter. This renders impossible any dramatic interpretation predicated on a simple narrative teleology. Yet at the same time, the soloist playfully exhibits the three traditional concerto mannerisms that Joseph Kerman (1999, 68) collectively terms virtù: bravura, mimesis, and spontaneity. Bravura and spontaneity are readily apparent in the opening solo: the former in the extreme virtuosity required to realize Sciarrino’s score, and the latter in the interruptive gestures, accelerations toward abrupt endings, and fragmented or unpredictably lengthened repetitions. As the concerto’s context widens to include the full orchestra, mimesis becomes increasingly significant as the piano can alternately be heard to imitate a human voice, its orchestral colleagues, other musics, and its own past and future self. Ultimately, each of Kerman’s traits is essential to the concerto’s distinctive gestural temporality and organicist themes. Sciarrino’s contemporary revitalization of classical aesthetic tropes is thus situated appropriately within a similar updating of an eighteenth- and nineteenth-century formal model.

[5.3] Music theorists and critics have developed numerous lenses through which to interpret the mysteries of musical time. In seeking to better understand Sciarrino’s multidimensionality, I was drawn to the connections between gesture and temporality explored by Kramer, Levy, and others because of the way they intuitively link raw temporal implications with motional energy and communicative figures. Gestural temporality arises in Recitativo oscuro as the analog wins out over the digital—as discrete pitches, cells, and effects are subsumed into holistically perceived cycles, processes of intensity change, and recognizable signs—and as those processes of integration are continually disrupted, refracted, and reflected back to the listener for contemplation. This, I believe, is what Sciarrino means when he implies that the opposition between abstract construction and the immediacy of representation is a false one, and when he invites us to hear form through an analysis of gestural behavior.

Antares Boyle

Portland State University

School of Music and Theater

Post Office Box 751

Portland, OR 97207-0751

antares@pdx.edu

Works Cited

Atkin, Albert. 2013. “Peirce’s Theory of Signs.” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. Stanford University: Metaphysics Research Lab. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/peirce-semiotics/.

Berry, Wallace. 1987. Structural Functions in Music. Dover.

Boyle, Antares. 2018. “Formation and Process in Repetitive Post-Tonal Music.” PhD diss., University of British Columbia.

—————. 2021. “An Image of the Cosmos: Repetition and Temporality in Sciarrino’s Instrumental Sillabazione Scivolata.” Perspectives of New Music 59 (1): 129–77. https://doi.org/10.1353/pnm.2021.0000.

Bregman, Albert S. (1990) 1994. Auditory Scene Analysis: The Perceptual Organization of Sound. The MIT press.

Cambouropoulos, Emilios. 2006. “Musical Parallelism and Melodic Segmentation.” Music Perception 23 (3): 249–68. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2006.23.3.249.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2010. “What Are Formal Functions?” In Musical Form, Forms and Formenlehre: Three Methodological Reflections, ed. William E. Caplin, James Hepokoski, and James Webster, 21–40. Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qf01v.5.

Carpenter, Patricia. 1988. “A Problem in Organic Form: Schoenberg’s Tonal Body.” Theory and Practice 1: 31–63.

Carpenter, Patricia, and Severine Neff. 1995. “Commentary.” In The Musical Idea and the Logic, Technique, and Art of Its Presentation, by Arnold Schoenberg. Edited, translated, and with commentary by Patricia Carpenter and Severine Neff, 1–86. Columbia University Press.

Cumming, Naomi. 2000. The Sonic Self: Musical Subjectivity and Signification. Indiana University Press.

Deutsch, Diana. 2012. “Grouping Mechanisms in Music.” In The Psychology of Music, ed. Diana Deutsch, 3rd ed., 183–248. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-381460-9.00006-7.

Giacco, Grazia. 2001. La Notion de “figure” chez Salvatore Sciarrino. Editions L’Harmattan.

Hanninen, Dora. 2012. A Theory of Music Analysis: On Segmentation and Associative Organization. Eastman Studies in Music 92. University of Rochester Press.

Hasty, Christopher F. 1981. “Segmentation and Process in Post-Tonal Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 3: 54–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/746134.

Hatten, Robert S. 2004. Interpreting Musical Gestures, Topics, and Tropes: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert. Indiana University Press.

—————. 2006. “The Troping of Temporality in Music.” In Approaches to Meaning in Music, ed. Byron Almén and Edward Pearsall, 62–75. Indiana University Press.

Helgeson, Aaron. 2013. “What Is Phenomenological Music, and What Does It Have to Do with Salvatore Sciarrino?” Perspectives of New Music 51 (2): 5. https://doi.org/10.7757/persnewmusi.51.2.0004.

Hopkins, Robert G. 1990. Closure and Mahler’s Music: The Role of Secondary Parameters. University of Pennsylvania Press. https://doi.org/10.9783/9781512802757.

Hubbs, Nadine Marie. 1990. “Musical Organicism and Its Alternatives.” PhD diss., University of Michigan.

Keefe, Simon P. 1999. “Dramatic Dialogue in Mozart’s Viennese Piano Concertos: A Study of Competition and Cooperation in Three First Movements.” The Musical Quarterly 83 (2): 169–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/mq/83.2.169.

Kerman, Joseph. 1999. Concerto Conversations. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674182028.

Kramer, Jonathan D. 1973. “Multiple and Non-Linear Time in Beethoven’s Opus 135.” Perspectives of New Music 11 (2): 122–45. https://doi.org/10.2307/832316.

—————. (1988). The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies. Schirmer Books.

Lefkowitz, David, and Kristin Taavola. 2000. “Segmentation in Music: Generalizing a Piece-Sensitive Approach.” Journal of Music Theory 44 (1): 171–229. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090673.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff. (1983) 1996. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12513.001.0001.

Levy, Janet M. 1981. “Gesture, Form, and Syntax in Haydn’s Music.” In Haydn Studies, ed. Jens Peter Larsen, Howard Serwer, and James Webster, 355–62. W. W. Norton.

Leydon, Rebecca. 2012. “Narrativity, Descriptivity, and Secondary Parameters: Ecstasy Enacted in Salvatore Sciarrino’s Infinito nero.” In Music and Narrative since 1900, ed. Michael L. Klein and Nicholas Reyland, 308–28. Indiana University Press.

Li, Mingyue. 2022. “The Ecological and the Existential: Sound and Subjectivity in the Works of Salvatore Sciarrino and Helmut Lachenmann.” PhD thesis, University of Oxford.

Lidov, David. (1987) 2005. “Mind and Body in Music.” In Is Language a Music?: Writings on Musical Form and Signification, 145–64. Indiana University Press.

Lochhead, Judy. 1979. “The Temporal in Beethoven’s Opus 135: When Are Ends Beginnings?” In Theory Only 4 (7): 3–30.

Meyer, Leonard B. 1973. Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520333109.

—————. 1979. “Toward a Theory of Style.”” In The Concept of Style, ed. Berel Lang, 33–38. University of Pennsylvania Press.

—————. 1989. Style and Music: Theory, History, and Ideology. The University of Chicago Press.

Mirka, Danuta. 2014. “Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, ed. Danuta Mirka, 1–57. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199841578.013.002.

Neff, Severine. 1993. “Schoenberg and Goethe: Organicism and Analysis.” In Music Theory and the Exploration of the Past, 409–33. The University of Chicago Press.

Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI, and Tito Ceccherini. 2008. Salvatore Sciarrino: Orchestral Works. Recorded 2006. Kairos 0012802KAI, 3 compact discs.

Rothfarb, Lee. 2002. “Energetics.” In The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, ed. Thomas Christensen, 927–55. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521623711.032.

Saxer, Marion. 2008. “Vokalstil und Kanonbildung: Zu Salvatore Sciarrinos ‘Sillabazione scivolata.’” In Musiktheater der Gegenwart. Text und Komposition, Rezeption und Kanonbildung, ed. Jürgen Kühnel, Ulrich Müller, and Oswald Pangl, 475–85. Wort und Musik, Saltzburger Akademische Beiträge 67. Verlag Mueller-Speiser.

Sciarrino, Salvatore. 1998. Le figure della musica da Beethoven a oggi. Ricordi.

—————. 2001. Carte da suono. Edited by Dario Oliveri. Dialoghi Musicali 1. CIDIM.

—————. 2004. “Conoscere e riconoscere.” Hortus musicus 5 (18): 53–55.

Snyder, Bob. 2000. Music and Memory: An Introduction. The MIT Press.

Solie, Ruth A. 1980. “The Living Work: Organicism and Musical Analysis.” 19th-Century Music 4 (2): 147–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/746712.

Song, Ju-Ping. 2006. “Writing the Sonic Experience: An Analytical Narrative of a Journey into Salvatore Sciarrino’s Five Piano Sonatas (1972–1994).” PhD diss., New York University.

Tenney, James. 1988. Meta-Hodos and Meta Meta-Hodos: A Phenomenology of 20th Century Musical Materials and an Approach to the Study of Form. 2nd rev. ed. Frog Peak Music. https://doi.org/10.2307/1578336.

Tenney, James, and Larry Polansky. 1980. “Temporal Gestalt Perception in Music.” Journal of Music Theory 24 (2): 205–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/843503.

Utz, Christian. 2010. “Statische Allegorie und ‘Sog der Zeit’: Zur strukturalistischen Semantik in Salvatore Sciarrinos Oper Luci mie traditrici.” Musik & Ästhetik 14 (53): 37–60.

—————. 2013. “Die Inszenierung von Stille am Rande ohrenbetäubenden Lärms.” Die Tonkunst 7 (3): 325–39.

Footnotes

* I would like to thank the following individuals for their helpful comments and suggestions on this essay: my three fellow panelists in this symposium (Robert Hasegawa, Mingyue Li, and Christian Utz), my friends Janet Bourne and Kristi Hardman, and two external reviewers for MTO (one anonymous and one self-identified as Nicholas Reyland).

Return to text

1. Timings provided throughout this article refer to this recording.

Return to text

2. See the other two essays in this symposium (Li, [3.4] and Example 2.2; Utz [3.10]) as well as Utz 2010) for further examples and discussion of Sciarrino’s use of insect-like sounds.

Return to text

3. The technique in which the two hands play simultaneous intersecting lines is found throughout Sciarrino’s piano music. In the earlier sonatas, cells in which the two hands move rapidly in contrary motion are treated somewhat more loosely, with flexible rhythm and pitch material; by Sonatas IV (1992) and V (1994), where these sonorities play a more significant role, they are mostly limited to three-note groups with the white-key/black-key distinction as in the piano solo of Recitativo oscuro. Later passages in the concerto also use the technique with different pitch material; see Example 11. Song (2006, 144–45) discusses how Sciarrino’s later piano sonatas build upon and reference his earlier works. Sciarrino’s performance techniques are so distinctive that it can be difficult to distinguish between compositional style and self-reference (Boyle 2021).

Return to text

4. The nature of Sciarrino’s organicism is elaborated on in the rest of this section and explored in my analysis; for a complementary and detailed perspective see Mingyue Li’s essay in this symposium (especially Section 2) as well as Li (2022, 39–80).

Return to text

5. See Rothfarb 2002 for a history of ideas of energetics in music theory, the “centrality of form” in energeticist analysis, and the connections between energetics and organicist ideas.

Return to text

6. Song 2006 provides the most comprehensive English-language summary of the principles articulated in Sciarrino’s writings, with an emphasis on Le Figure.

Return to text

7. “Significato e rappresentatività riunificano infine le varie componenti di un linguaggio e ne costituiscono la più intima energia. Ora, due aspetti apparentemente antitetici profilano questa music: la costruzione astratta, e insieme l’immediatezza iconica, indice, questa, del rapporto nuovamente ritrovato con la

Return to text

8. See Utz 2013 for a contextualization of Sciarrino’s poetics within the “perceptual turn” of new music, which emerged most clearly in the 1980s but had roots in 1950s serial thought, and for a discussion of the origins of Sciarrino’s “figures” in a 1985 Milan conference also featuring Franco Donatoni and Brian Ferneyhough.

Return to text

9. “Una musica di insiemi. Cosa implica questo

Return to text

10. These terms are drawn from Peirce’s three categories of signs, defined by the relationship between the sign and the object. In the simplest terms, icons are based on a relationship of “likeness,” indices on a relationship of “causality,” and symbols on a relationship of “convention” (see Lidov 2005; Cumming 2000, 86–95; Atkin 2013). However, in practice these categories are complex and overlapping, and music semioticians have not always agreed on the distinction between “icon” and “index” in particular (Mirka 2014, 32–36). Naomi Cumming, who links indexicality to a physical response, points out that indexical qualities are embedded within iconic gestures, because “the energy and directedness of an index is not lost” (Cumming 2000, 92) even as the gesture takes on holistic meaning.

Return to text

11. Metaphors of drama and dialogue have long animated concerto analysis.; for relatively recent examples, see Kerman 1999 and Keefe 1999.

Return to text

12. Gesture X at the opening might be interpreted as an instance of Sciarrino’s “little bang” (Sciarrino 1998, 67–75). The little bang (comparable to his “big bang” figure, but smaller in scale) is an unexpected event that occurs within a static musical texture or at a piece’s opening and triggers new activity; Sciarrino provides the accented chord that opens Pierre Boulez’s “Don” (from Pli selon pli) as an example.

Return to text

13. For the purposes of my analysis, I offer a streamlined definition of this complex term; for a more nuanced elaboration of the concept within Schoenberg’s broader organicist thinking, see the works of Patricia Carpenter and Severine Neff (Carpenter 1988; Neff 1993; Carpenter and Neff 1995). Although it is not my primary purpose to elucidate connections between Sciarrino’s aesthetic and Schoenberg’s theory specifically, further contemplation does yield some interesting resonances not fully explored here. A slightly different interpretation that was suggested to me (although not in precisely these terms) by both of the journal’s thoughtful reviewers is that X poses a “question” at the start of the piece, akin to Schoenberg’s “tonal problem,” which the rest of the piece (in a contemporary updating of Schoenberg’s conception) investigates but declines to answer in any tidy way.

Return to text

14. The only exceptions are the interrupting gestures Z and W, discussed later in my analysis.

Return to text

15. In an exploration of organicist concepts and their application to musical structure, Nadine Hubbs 1990 refers to this ideal as “essential permeation,” defined as “an inter-hierarchic saturation of some particular essence” (Hubbs 1990, 13). Hubbs offers Schenker’s “hidden repetition” as an example. Hubbs considers essential permeation to be one manifestation of the necessary organicist attribute “unity of parts and whole” (Hubbs 1990, 13, 42). For further nuanced discussions of organicist concepts of part/whole relations, see Solie 1980, Carpenter 1988, and Neff 1993.

Return to text

16. “Poiché [questa] musica si concretizza in grumi già complessi di suoni, assomiglia non poco al mondo fisico, i cui atomi rispecchiano i grandi sistemi gravitazionali. La scienza, il pensiero frattale, proprio oggi riscoprono le coincidenze di micro e macrocosmo. Analogamente, [questa] musica si configura come pluralità di insiemi.”

Return to text

17. “La relazione fra le singole figure, o i raggruppamenti di figure in unità logiche di varia grandezza, sono di natura funzionale, cioè teleologica.”

Return to text

18. See Mingyue Li’s article in this symposium ([1.3]) on the association of nineteenth-century organicism with regressive social and political values.

Return to text

19. This balance resembles (and is related to) that between cyclic and teleologic temporal processes described by Utz 2010; see also Saxer 2008, Leydon 2012, and Boyle 2018. Li’s essay in this symposium (see especially Section 2) proposes that we embrace a nonreductive, biological-ecological understanding of Sciarrino’s organicism, one which recognizes a whole that is “distinctly plural” ([1.4]).

Return to text

20. Lochhead’s (1979) essay was written in response to Kramer’s earlier (1973) formulation of the idea of gestural time; Kramer’s later (1988) work revises and clarifies several concepts in response. I use the terms “contextual” and “gestural” temporal function here (borrowing one term from each theorist) in order to avoid potential confusion over the term “absolute,” which they use differently.

Return to text

21. Various scholars (Berry 1987; Tenney 1988, 36; Meyer 1989, 15–16; Hopkins 1990; Snyder 2000, 211–12) have discussed the association of decreasing intensity with closural function. Outside the context of specific style conventions (see, e.g., Caplin, 1998 and 2010), beginning function is undertheorized compared to ending (closure). See Boyle (2018) for discussion of “intensity curves” (after Berry 1987) as an archetypal beginning–middle–ending shape. The association of low intensity with closure may be broadly conventional within Western music at large, or within the tonal traditions in which most Sciarrino listeners are steeped, rather than innate or universal (Boyle 2018, 65). That distinction does not matter for the purposes of my discussion.

Return to text

22. While Example 2 may seem somewhat reductive, the simple framework here provides a workable context for exploring the source of more complex temporal sensations that may arise when processes of intensity change conflict with beginnings and endings suggested by factors such as repetition, as described below. See Utz’s essay in this symposium (especially [3.2–3.3]) for an alternative approach that also considers situations of consistent or static intensity levels and posits a distinction between “marked” and “unmarked” beginnings and endings, among other differences.

Return to text

23. See, for instance, Tenney and Polansky 1980; Hasty 1981; Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1996, 26–67; Hanninen 2012, 19–43. Hanninen offers a robust method for examining the relationship between individual segmentation criteria (her term, which I borrow here) and segments themselves.

Return to text

24. In her overview of grouping mechanisms, Diana Deutsch (2012, 209) concludes, “In general, grouping by temporal proximity has emerged as the most powerful cue for the perception of phrase boundaries.” Tenney and Polansky (1980) and Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1996) give temporal discontinuities their own category as a grouping mechanism, and equate its importance with that of spatial proximity in visual gestalt perception.

Return to text

25. A rest following a process of reduction in volume or rhythmic density may at first simply be perceived as a natural continuation of that process, and any rest takes time to be heard as such, so these boundaries tend not to be as cut-and-dried as they appear on paper.

Return to text

26. This makes it challenging to account for repetition within an algorithmic segmentation model (see Tenney and Polansky 1980; Lefkowitz and Taavola 2000; Cambouropoulos 2006). Hanninen (2012) separates sonic segmentation criteria, which are based on psychoacoustic properties and proceed “from the bottom up” (Hanninen 2012, 5), from more top-down contextual criteria based in repetition, association, and categorization.

Return to text

27. The segmentation in Example 3 is not “well-formed” in that it does not feature consistent nesting of hierarchical levels (Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1996, 37–39; Tenney and Polansky 1980, 218). (For instance, in m. 6, my segmentation shows a “missing” level where the two clusters and the new ff formation refuse to cohere into a higher-level segment.) The avoidance of a perfect classical hierarchy is prominent in my experience of the piano solo: its nested repetitions clearly intimate hierarchical structures, yet some shorter segments seem to resist cohering into higher-level phrases, instead remaining autonomous or occupying a more ambiguous formal level. This feature interacts provocatively with the contradictions of the solo’s “gestural time” by obscuring the formal level at which an implied temporal function operates.

Return to text

28. My analysis also explores the way that certain ambiguities of segmentation resulting from conflicting grouping criteria, which are omitted from Example 3 for simplicity, can mirror or amplify the contradictions between segmentation and gestural shaping.

Return to text

29. Hatten calls such composition techniques the “troping of temporality,” defined as “the complex syntheses that occur when composers explore unexpected relationships between the expected location of musical events and the actual location where they appear.” These apparent reorderings are “dramatically marked” against our unmarked experience of temporality as an ongoing present (2006, 62). Elsewhere, Hatten has defined “troping” as the “process by which new meaning emerges from atypical or even contradictory associations between more established meanings” (2004, 2).

Return to text

30. Since processes of intensity change cannot create firm boundaries, the identity of the gesture is somewhat flexible, expanding to include the new cells that participate in its upsweep of intensity. The pitch cells of the original gesture (boxed in the example) are aurally familiar, but no longer form autonomous segments. I label the last two occurrences with a prime symbol to indicate the more substantial variations (change in dynamic or pitch), but since they follow two segments that end with more literal repetitions, I still hear them as versions of the original X.

Return to text

31. The escalation of intensity also obliterates the clear demarcation of lower-level segments present in the first half of the phrase.

Return to text

32. “L’intermittenza dimensionale è un concetto essenziale per capire questo tipo di forma, dove musiche parallele sembrano interferire tra loro. Un concetto che dovrebbe risultare familiare, data la facilità con la quale oggi entrano in contatto esseri e avvenimenti lontani.”

Return to text

33. I do not consider gesture Z an instance of Sciarrino’s “little bang” (see note 13) for two reasons: first, because the situation on which it interferes is not static, and second, because it does not seem to have an effect on the unfolding of the surrounding X- and Y-based material.

Return to text

34. To my ears, the gestural shape also helps to associate specific pitch clusters with the start of each gesture. The original gesture X and all recurrences of X that serve as discrete segments lead with the B-C-D/

Return to text

35. For instance, Y4 and Y6 start to speed up. Y7 stays relatively low intensity, but with an unexpectedly forte cluster near its low-register nadir.

Return to text

36. Similar cyclic repetition occurs in Sciarrino’s Shadow of Sound (2005).

Return to text

37. This pulsation disappears toward the end.

Return to text

38. Most of the program note presents a kind of poetic ethics of listening. The references to mythology and dreams occur within a description of listening to repeated material yet hearing difference and change.

Return to text

39. This is what Albert Bregman (1994, 459–60) refers to as a “chimeric” assignment. In the opposition that Bregman sets up, “natural” assignments correctly attribute elements of the sonic field to their individual environmental sources, while chimeric assignments group sonic elements from disparate sources into a single “virtual” source. Bregman observes that while in normal listening, the auditory system tries to avoid chimeric assignments, music often cultivates them; for instance, principles of orchestration describe ways to create orchestral blend. However, I would argue that in standard orchestral listening, hearing auditory chimeras is a matter of habit and choice: it is usually not difficult to identify individual instrumental sounds if so desired.

Return to text

40. In addition to the two types of piano interjections I describe here, a third distinct type sounds only at the beginning (mm. 45–49) and towards the end (mm. 145–50; 175–83) of the concerto’s long cyclic middle section, creating a kind of transitional region or buffer zone separating that material from the opening solo and the climactic ending passage.

Return to text

41. “Il pianoforte solista viene a stagliarsi quasi fosse un personaggio parlante, e accenna dialoghi un tempo inconcepibili fra tastiera e scoppi di suono for temente naturalistico.”

Return to text

42. More effusive instances of sillabazione scivolata typically append each gesture with a flurry of rapid notes. The technique is used extensively in the vocal parts of Luci mie traditrici (1996–98) and Studi per l’intonazione del mare (2000), and in String Quartet No. 7 (1997), all written around the time of Recitativo oscuro. It becomes prominent in Sciarrino’s orchestral and chamber works with strings in the following decade; see for example the orchestral works Archeologia del telefono, Shadow of Sound, Vento d’Ombra, and Il suono e il tacere (all 2004–2005), the String Quartets 8 and 9 (2008 and 2012), or the solo violin works Fra sé and Capriccio di una corda (both 2009).

Return to text

43. See Helgeson (2013) for a phenomenological exploration of Sciarrino’s sounds lying at the threshold of audibility.

Return to text

44. The final moments of this ending (following the X and Y references) are what Utz, in his essay in this symposium ([2.3]) calls a “semanticized rupture”: an ending that is particularly marked in its enigmatic and unresolved nature and by its use of entirely new material. Endings like this are found in many of Sciarrino’s works.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2023 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Amy King, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4757