Female Subjectivities in the Words, Music, and Images of Progressive Metal: The Case of Tatiana Shmayluk (Jinjer)*

Lori Burns

KEYWORDS: Jinjer; Tatiana Shmayluk; female metal vocalist; progressive metal; female subjectivities; femininities; gender studies; multimodality; spectrogram analysis

ABSTRACT: Heavy metal scholarship affirms the genre to be dominated by male performers and points to a preponderance of patriarchal values and hypermasculinity, with performances contributing to an aesthetic production of misogyny, power, and intensity. The notion of heavy metal as a hegemonic discourse has been queried, however, by recent scholars who reveal metal to support a range of gendered and sexualized subjectivities. This paper examines how a specific metal vocalist—Tatiana Shmayluk (of the Ukrainian band Jinjer)—navigates the discourse of progressive metal to challenge hegemonic norms and create space for alternative female subjectivities.

Jinjer’s defiance of genre boundaries and Shmayluk’s metal vocal expression emerge through a multi-faceted dialogue with an array of cultural references. To illuminate the unique blend of referentiality and creative expression within Jinjer’s work, this article offers analyses of three music videos: “I Speak Astronomy,” “Perennial,” and “Pit of Consciousness.” With the aim of understanding how Shmayluk navigates the discursive space of metal music, the selected songs are situated in relation to the subgenres to which they refer, and specifically to male-fronted metal bands that mobilize similar thematic materials. The close readings of these music videos are grounded in the existing analytic literature on metal music, with consideration of genre-based compositional, stylistic, and expressive elements to unveil Shmayluk’s challenges to the constraints upon “femininity” in metal music.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.29.4.2

Copyright © 2023 Society for Music Theory

Gender constructions in heavy-metal music and videos are significant not only because they reproduce and inflect patriarchal assumptions and ideologies, but more importantly because popular music may teach us more than any other cultural form about the conflicts, conversations and bids for legitimacy and prestige that comprise cultural activity. Heavy metal is, as much as anything else, an arena of gender, where spectacular gladiators compete to register and affect ideas of masculinity, sexuality and gender relations. (Walser 1993a, 111)

Introduction

[1.1] Robert Walser’s 1993 commentary on heavy metal remains relevant today: as a significant popular music genre, metal music is an arena in which dominant ideologies guide representations of gender, sexuality, and power relations; my concern with this statement lies in its privilege of masculinity as the primary point of reference. Three decades later, despite an expanding music-analytical literature on metal music, the discourse is still primarily focused on “masculinity” and the music of male metal vocalists and musicians. Music analysts are investing considerable energy to define and illustrate complex rhythmic, metric, harmonic, formal, and sonic structures in this genre.(1) By contrast, there is insufficient music-analytical work on female(2) metal vocalists and musicians;(3) rather, in the consideration of female metal artists, the scholarly writings tend to focus on representations of femininity and sexuality in the lyrics and visual images of metal music,(4) and gendered aspects of the industry and subculture scenes,(5) often with critical reception and ethnographic methodologies guiding the work. If we are to begin to build an understanding of the musical expression of female metal artists, it is important to situate their work within the subgenres of metal music composition and performance, and to illuminate the specific ways in which they occupy space—not just in lyrics and images, but also in the musical structures and expressive strategies. I thus adopt a material-based multimodal analytic methodology to conduct close readings of the words, music, and images of a specific female-fronted metal band—Jinjer. With the aim of understanding how a female artist navigates the discursive space of metal music, I situate the selected songs in relation to the subgenres to which they refer, and specifically to male-fronted metal bands that mobilize similar thematic and expressive materials.

[1.2] Within the domain of metal music, female artists occupy an extremely small minority of the performing musicians and vocalists (Berkers and Schaap 2018, 104). Scholarship on metal affirms that the genre is dominated by male performers, with female participation beginning to grow around the turn of the millennium (Weinstein 2016, 20). Metal scholars also point to the preponderance of patriarchal values and hypermasculinity, with the lyrical, musical, and visual content contributing to the aesthetic production of blatant misogyny and sonic power.(6) The participation of women in metal scenes is often reduced to “tokenism” (Schaap and Berkers 2014), wherein female performers are understood to be staged for the patriarchal gaze and critiqued according to sexist ideologies and archetypes.(7) In 2009, Weinstein went so far as to assert that “seemingly the best that women can do is make fun of the sexism while embodying it” (2009, 69), however, this reductive position has been disputed by other scholars (DiGioia and Helfrich 2018).

[1.3] Walser’s claim that heavy metal is “a discourse shaped by patriarchy” exhibiting “fantasies of masculine virtuosity and control” (1993a, 108–109) has been queried by recent scholars who are beginning to reveal metal to be a cultural space that supports a range of gendered and sexualized subjectivities. Such scholars explore the ways in which women navigate—as fans, writers, and performers—the terrain of metal subgenres, putting hegemonic norms into dispute. Keith Kahn-Harris encourages a departure from white, heteronormative masculinity (what he calls “the metal identity triad” [2016, 28]) and Amber Clifford-Napoleone identifies metal with queer space by opening up new perspectives on metal scenes (2015). These approaches introduce the notion of genderplay into the discourse around metal and serve to disrupt the restricted binary constructions of “hegemonic masculinity” and “emphasized femininity” (Connell 1987, 184–185). They also call for analysts to do the necessary interpretive work to build understanding and engagement with individual examples, rather than reducing artists to fixed categories. In the interest of challenging the restrictive hegemonic mythologies of gender representations in metal, Niall Scott advises us to “ground a constructed perspective of masculinity from examples in heavy metal itself, rather than the use of myth” (2016, 122). With this article, I take up Scott’s call, apply his analytically grounded approach to representations of femininity, and analyze the work of an individual female artist in metal music.

[1.4] As subgenres have progressed and new generations of artists and bands have appeared, female participation in metal has evolved to feature women as band members in a range of metal subgenres and there is a growing number of “female-fronted” metal bands. It is the latter category that I seek to investigate here, to address the particularly complicated gender dynamics created when a woman is the “star” vocalist in an otherwise male metal band. In popular music, the role of the singer has been described reductively as a feminine position (Auslander 2004), subject to an objectifying male gaze. This position is particularly fraught in the subgenres of metal, given the dominance of an extreme binary split between masculinity and femininity in metal subcultures (Krenske and McCay 2000; Riches 2015). Berkers and Schaap posit femininity as a “double-edged sword that women in metal music production have to deal (and often struggle) with” (2018, 106). They see the higher visibility attached to being a woman in metal as offering “both positive and negative tensions” (99).

[1.5] Some scholars view the role of the female lead singer as an empowered female subjectivity, yet the locus of that power is yet to be separated from gendered and sexualized stereotypes. Weinstein declares that “metal’s defining cultural characteristics like power, strength, and rebellion are ‘culturally masculine’ and that all members of the subculture including female musicians are playing with [...] cultural masculinity’” (2009, 24–25). She specifically sees cultural masculinity as “available to others” (19). This interpretation would understand the performance of female metal singers to exemplify Halberstam’s (1998) notion of “female masculinity,” in which a female adopts and exhibits attributes associated with maleness. The strategy of playing along with masculine codes is interpreted by Andrew Cope as a gesture of “solidarity” (2010, 79), however, in some examples, female metal bands reclaim and reverse violent spaces; for instance, Joan Jocson-Singh (2019) studies transgressive “vigilante feminism” in bands such as Castrator.

[1.6] Challenging the binary assumptions of gender, Rosemary Hill finds such assumptions about the “masculine” attributes of metal to constitute a “rejection of femininity” that “positions women fans as involved in the disparagement of their own gender as they align themselves with a masculine culture that writes out the feminine” (2016, 117). In her ethnographic research, Hill poses questions about the availability of aggression as an expressive strategy in metal music. Adopting a similar stance, Gabby Riches declares that if “physical exertion, power, aggression, anger, pain and heavy metal identities are only intelligible on the male body it inevitably marginalizes women and the kinds of questions we can ask about heavy metal’s significance in the lives of the ‘Other’” (2015, 205). As instances of how to challenge assumptions about performative aggression, Florian Heesch examines Angela Gossow’s production of the growling vocal, asserting that “the musical phenomenon of death metal growling has the potential to confuse widespread notions about male and female voices” (Heesch 2018, 3) and Jocson-Singh considers the guttural vocals of M.S. (in the band Castrator) as “inverting the discourse of what is typically described as hyper-masculine” (2019, 268).

Theorizing Multiple Femininities

[2.1] In response to theoretical discussions of “female masculinity” at one extreme (Halberstam 1998; Messerschmidt 2004) and “subordinate femininity” at another (Pyke and Johnson 2003), gender theorist Mimi Schippers (2007) proposes that we have not adequately conceptualized “multiple femininities” at a level that is comparable to R.W. Connell’s (1995) influential ideas about “multiple masculinities.” Connell’s understanding, not only of hegemonic masculinity, but also a range of subordinated and marginalized masculinities (e.g., masculinities arising from intersectional identities), allows for the exploration of multiple expressions of masculinity. How and where femininity figures into this formulation is less nuanced: Connell and Messerschmidt formulate “emphasized femininity” in relation to “hegemonic masculinity,” seeing these configurations to be compliant with dominant patriarchal ideals, nevertheless calling for “closer attention to the practices of women” (2005, 848; cited in Schippers 2007, 85). Taking up that call, Schippers (2007, 86) opens the discussion of gender hegemony to build a framework that “allows for multiple configurations of femininity.” She summarizes the challenge for women as follows:

If hegemonic gender relations depend on the symbolic construction of desire for the feminine object, physical strength, and authority as the characteristics that differentiate men from women and define and legitimate their superiority and social dominance over women, then these characteristics must remain unavailable to women. (Schippers 2007, 94–95)

[2.2] Instead of reducing behavior that disrupts these constraints to “pariah femininities” or “male femininities,” Schippers (2002) refers to “alternative femininities and masculinities,” using the example of rock subcultures that reject hegemonic norms and indicating that specific cultural contexts and relational structures are vital to the interpretation of gender ideals. Understanding masculinity and femininity as symbolic constructions, it is possible to mobilize an alternative model for gender performativity that “allows for those occupying the social location ‘woman’ to engage in practices or embody characteristics that are defined as masculine” (Schippers 2007, 92). Ultimately, Schippers’ model promotes “multiple configurations” of femininity (91) and advocates for a dynamic discursive process, in which gender is produced and contested (94). For Schippers, cultural gender maneuvering is “a process of negotiation in which the meanings and rules for gender get pushed, pulled, transformed, and re-established” (Schippers 2002, 37). This model offers a perspective for understanding gendered performance in rock music by examining “the efforts to manipulate the relationship between masculinity and femininity as it takes shape in rules for the general patterns of social relations within any culturally specific milieu” (2002, 40). The role of power in this conceptualization of gender is significant as Schippers’ goal is not merely to account for behaviors, but rather for “the power relations and distribution of resources among women, men, and others and how masculinity and femininity as networks of meaning legitimate and ensure that structure” (2007, 101). In the face of this challenge, and in keeping with her call for more nuanced work on femininity, I will not interpret masculinity and femininity as a “fixed set of behaviors” but rather will see gender practices as being “constituted through the proliferation of a network of cross-cutting, sometimes contradictory discourses” (Schippers 2007, 93).

Tatiana Shmayluk and Jinjer

[3.1] As scholars seek to situate female performance in metal, it is evident that they are invested in and troubled by the gendered cultural spaces that women occupy within the genre. Lacking in the scholarship is a thorough examination of the musical contributions (i.e., vocal expression and song writing) of the leading female vocalists in metal. This is a vital gap to fill if we are to move beyond a reductive and objectified view of female artists in metal and to receive them as crucial actors in the musical expression of metal music. The goal of this article is to “ground a constructed perspective on [femininity] from examples in heavy metal itself. . . ”(8) by examining the musical contributions of Tatiana Shmayluk, an artist who claims and occupies space in performative strategies that expand the constraints upon and definitions of “femininity” in metal music.

[3.2] Since forming in 2009 under the leadership of female vocalist Tatiana Shmayluk and guitarist Roman Ibramkhalilov, the Ukrainian metal band, Jinjer, has created a well-received and genre-defying body of musical work.(9) Their EP Inhale, Do Not Breathe led to the band’s recognition as the Best Ukrainian Metal Act by InshaMuzyka in 2013. The self-produced Cloud Factory of 2014 was re-released by Napalm Records, and they have stayed with Napalm for their album King of Everything (2016), the EP Micro (2019), the album Macro (2019), and their most recent album, Wallflowers (2021). Probably best identified as progressive metal, they draw upon the influences of death metal, metalcore, groove metal, djent, and alternative metal.(10) Critics reveal the band’s genre complexity when they mention the blend of genres. The band itself resists stylistic restrictions, claiming “Any sort of stylistic boundaries, they do not exist for us. It’s diversity and diversity, and again, diversity” (Graff 2019).

[3.3] In the reception of Jinjer’s work, much attention is accorded to Shmayluk for her performances of extreme or “harsh” (growling and screaming) vocals in juxtaposition with “clean” vocals.(11) A reviewer of King of Everything (2016) comments, “Feisty growls and soul-shattering clean vocals, front-woman extraordinaire Tatiana Schmailyuk holds the balancing elements that keep it all together and guarantee to rattle your bones” (FrontView Magazine 2016). This same article lists several journalistic remarks, including the following comment that appeared in Rock Hard: “The melodic voice of Tatiana is a cuddle for the heart betrayed by the brutality of a fresh, exhilarating, destructive progressive metalcore sound!” (FrontView Magazine 2016). J. Bennett of Revolver Magazine describes the EP Micro as “a groove-laden fusion of techy nu-metal and staccato djent spearheaded by Shmayluk’s vocals, which seesaw from feral roars to R&B-inflected melodies” (2019).(12) One Jinjer video that continues to attract a great deal of attention (currently over 66 million views) is their live session recording (2017) of “Pisces,” a clip that showcases Shmayluk’s ability to shift between harsh and clean vocal styles (Jinjer 2017).(13) Another clip of special note is her one-take performance of “Judgement (& Punishment)” in which she performs the vocal part, maintaining a profile stance in order to allow a full capture of her jaw, throat, and chest as she shifts from clean, belted vocals to deep guttural growls (Jinjer 2020).

[3.4] Jinjer’s defiance of genre boundaries and Shmayluk’s expansion of female metal vocal expression emerge through a multi-faceted and complex dialogue with an array of cultural and popular music references in words, music, and images. To illuminate the unique blend of referentiality and creative expression within Jinjer’s work, this article offers analyses of three music videos: “I Speak Astronomy,” “Perennial,” and “Pit of Consciousness.” For artists of all popular music genres, the music video is a significant site for the expression of cultural themes and messages and in order for that cultural expression to be both intelligible and meaningful, videos rely upon the workings of musical genre.(14) I explore the thematic content in words and images, as these are in dialogue with the genre-based compositional, stylistic, and expressive elements of the music. I reveal that thematic content to comprise “a system of references to other [works], other texts, other sentences. . . ” (Foucault 1972, 23)—thus, an intertextual engagement with the creative output of bands whose work has been significant in the establishment of the metal subgenres to which Jinjer refer.(15) Elsewhere, I have defined intertextuality simply as “the web of interrelated creative elements that link a text to other texts” (Burns, Woods, and Lafrance 2015, 4). More specifically, the aspect of Jinjer’s intertextual framing that I will examine is the representation of femininity in metal music videos. As lead vocalist of the band, Shmayluk achieves a unique performance of gendered subjectivity through a complex intertext through which she revisits, challenges, and transforms existing representations of metal femininity.

Analytic Objectives

[4.1] Thus motivated to understand representations of gender and sexuality within the specific contexts of metal subgenres, and considering a female metal vocalist’s material and expressive work as the object of inquiry, I explore the following questions:

- How does a female metal artist occupy (claim) performative space in the expressive channels of words, music, and images?

- What cultural themes and whose gendered practices are being conveyed through these expressive channels?

- How might a female artist complicate these themes and practices to transform the conventional representations of gender and sexuality within metal subgenres?

[4.2] In order to ground these interpretive questions within a material analysis of content and expression, my analytic methodology involves several steps of consideration:

- situating the music video in its intertextual contexts in order to identify and better understand the larger cultural discourse—grounded in subgenres—in which the artist/band participates;

- examining how these intertexts shape cultural expressions of power, authority, and aggression in relation to gender;

- exploring music–analytic data in dialogue with lyrics and images to illuminate how the selected artist engages with cultural messages and genre-based meanings; and

- interpreting the gendered aspects of the expressive multimodal attributes over the narrative arc of the song.

[4.3] To clarify further, the music–analytic data will include form; metric, rhythmic, and harmonic structures; vocal and instrumental content and expression; and production elements. As I elaborate this data, I will refer to spectrogram images and sound for selected passages, as well as to specific segments of the music videos. Multimodal analysis requires rigorous and systematic attention to the three individual channels of expression (words, music, images) across all sections of the song; the analysis presented here is thus meant to create a narrative immersion and reflective interpretation of these expressive channels in a fully integrated multimodal dialogue.(16)

[4.4] In Jinjer’s multimodal work, material and expressive information emerges in the lyrical, musical, and visual domains that point to complex levels of cultural commentary about the role of gender in progressive metal music. Drawing from a large discourse of metal music and developing intertexts with clusters of bands that explore specific themes, Jinjer—with Tatiana Shmayluk at front and center—manipulate and transform those themes in ways that implicate gender. With the chosen music videos as illustrative case studies, I illuminate how Jinjer address representations of femininity in metal music, manipulating and transforming these representations to invite new ways of understanding the female voice in metal. For each music video, I present the thematic analysis and intertextual points of reference to other metal bands; I offer a close reading of the song form with the aim of intersecting analytic elements from words, music, and images; and I consolidate my primary interpretive arguments in a brief closing section.

Analysis I: Cosmic Bodies

“I Speak Astronomy” (King of Everything, 2016)

[Track produced by Max “Morton” Pasechnik; Video directed by Ingwar Dovgoteles]

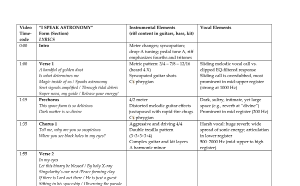

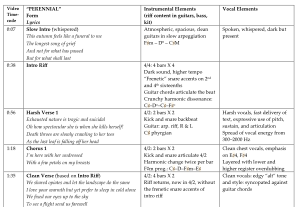

Example 1. “I Speak Astronomy,” Lyrics and Formal Structure

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[5.1] “I Speak Astronomy” offers a reflection on human subjectivity in relation to the universe. Tatiana Shmayluk’s lyrics (Jinjer 2016b), provided in Example 1, convey the perspectives of a subject whose understanding of identity is shaped by astronomical contexts, for instance, in the opening line that declares the subject to be determined by “golden dust.” Signals sent through space provide humans with energy, satisfying spiritual needs as the subject reflects on human desire and cosmology (“dark matter is so divine”). At the same time, the human–cosmic relationship is shown to be mysterious and potentially intimidating, as expressed in the line, “When you see black holes in my eyes.” The subject, fully aligned with these interstellar attributes, invites an implicit subject to unite with her in an astronomically determined relationship.

[5.2] Lyrical topics invoking extraterrestrial space are well worn in the genres of progressive and art rock, with early examples in the work of Pink Floyd (The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, 1967), David Bowie (Ziggy Stardust. . . , 1972), as well as space rock developments such as T.Rex (Electric Warrior, 1971) and Hawkwind (Space Ritual, 1973). In the genre of metal, we can look to Black Sabbath’s Master of Reality (1971) as an early venture into the theme of space travel. More recently, and specifically in the context of progressive metal, the cosmos and otherworldliness are strikingly evident in the work of bands such as Between the Buried and Me, Born of Osiris, Gojira, and Scar Symmetry.

[5.3] This latter development in progressive metal reveals a profound concern for the environment and looks hopefully to new galaxies in response to fears about environmental catastrophe. For instance, in the song “Astral Body” (Between the Buried and Me, The Parallax II: Future Sequence, 2012) the subject floats in space following the destruction of his planet, deconstructing his corporeal self through lyrics that connect to the Jinjer song under consideration: “Blacked out eyes in an existence overgrown.” Similarly, Gojira’s “Heaviest Matter of the Universe” (From Mars to Sirius, 2005) presents a subject on a journey from his physical world (“I cross the clouds and colours / The black hole is calling me”), ultimately coming to understand that “. . . in the centre stands the light of love,” thus offering hope through transformation. Scar Symmetry’s title track from Holographic Universe (2008) questions the truth of space and time by proposing a new form of consciousness through holographic light (“. . . the beam will underline the birth of the universe”). Born of Osiris’s “Goddess of the Dawn” (Soul Sphere, 2015) asks the vital question, “Can we avoid our absolute destruction?” but seeks human solace in the notion that “It’s love that connects us.” Although the treatment of this theme is apparently without gender specificity, nevertheless the song title introduces a divine feminine essence that is implicitly associated with the concept of human love.

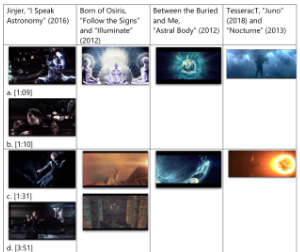

Example 2. Screenshots from “I Speak Astronomy” and visual references to the work of progressive metal bands

(click to enlarge)

[5.4] Not exclusive of female reference points, this discursive treatment of cosmic power presumes human universality and is presented primarily by all-male and white progressive metal bands. Women do not emerge in the visual economy of these works; these are omniscient male perspectives on the fragility of the physical world and the potential of an altered state in the cosmos. Example 2 reproduces a few stills from music videos (by Born of Osiris, Between the Buried and Me, and TesseracT) that engage with this theme and juxtaposes these images with stills from Jinjer’s music video, “I Speak Astronomy.” In this visual realm, bodies of epic proportions, often in god-like forms, appear in dark scenes where they interact with material elements in otherworldly contexts and emit celestial powers: asteroids and star constellations surround the figures and their physical forms have a dynamic function in space, not delimited by natural human boundaries. Astronomical patterns dominate the sky and horizon with illuminated geometrical designs. Celestial bodies and columns of light create a sense of cosmic connections. My point of primary concern here is that throughout these works, cosmic power is not made intelligible on the female body (Riches 2015).

[5.5] Compared to the male god-like figures in the work of these progressive metal bands, Jinjer mobilize this topic to showcase Tatiana Shmayluk in the role of the other-worldly figure. Larger than life (Examples 2a and 2d) and sometimes distorted and fragmented in appearance, her body is nonetheless feminine in her style of make-up and dress (Example 2c). She is unconstrained by gravity in relation to her fellow band members (Examples 2a and 2b) until the closing scenes, when her feet appear to be grounded on the interstellar land (Example 2e). Even there, she interacts with her spatial surroundings in unearthly ways as her hand intersects with the celestial column of light (Example 2f). By inserting herself into this story and specifically adopting the role of the god-like (omniscient) figure, she claims an image of power for female metal vocalists, asserting that such a status is available to women (a point of concern for Hill 2016; Riches 2015; and Schippers 2007).

[5.6] Turning to the musical expression, I now consider how Shmayluk conveys this transcendent story of human subjectivity in relation to the universe. Content in the lyrical and visual channels invites consideration of the impact of a female vocalist upon this space-rock topic. I analyze elements of Shmayluk’s expression within the song narrative to understand how this particular story is conveyed in musical time and space. The song form, outlined in Example 1,(17) presents two statements of a verse–prechorus–chorus sequence, a vocal bridge, and a novel section—heard three times in increasingly intensified textures—which functions as a terminally climactic chorus (Osborn 2013). The formal design is developed by Shmayluk’s exploration of vocal strategies, including the contrast of clean (undistorted) and harsh (distorted screaming) styles, a shift that is familiar to metalcore and progressive death metal (Kennedy 2017, 87).

[5.7] The materials presented in the verse–prechorus–chorus sequence reveal constantly shifting metric patterns and vocal styles. The sequence illustrates the “telos principle” (Nobile 2022) as musical energy builds from verse to prechorus to chorus. Following a lengthy intro that establishes a heavy riff characterized by meter changes and syncopation typical of progressive metal, the first verse features call and response patterning in which a seductive, sliding vocal call is answered by a clipped, filtered response. The changing metric pattern (

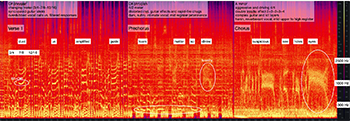

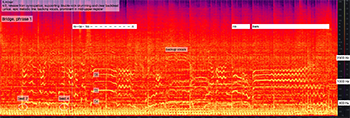

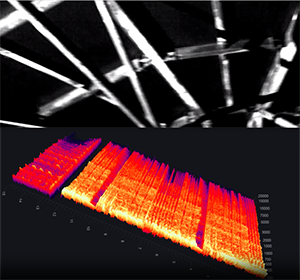

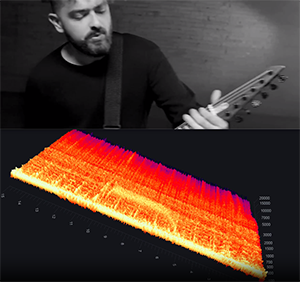

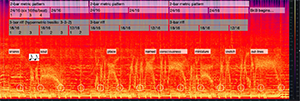

Media Example 1. “I Speak Astronomy,” Verse 1 – Prechorus – Chorus, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[5.8] These changing vocal qualities and expressive gestures emerge clearly in Media Example 1, an annotated spectrogram for the first verse, prechorus, and chorus.(23) The sonic image of the verse illuminates the strength of the overdubbed sliding vocal calls, with intensity in the mid-upper register; for instance, at “dust,” she slides from B3 to

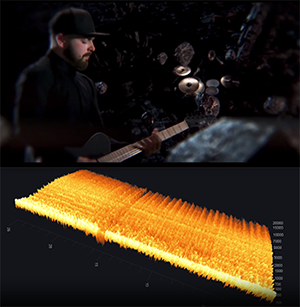

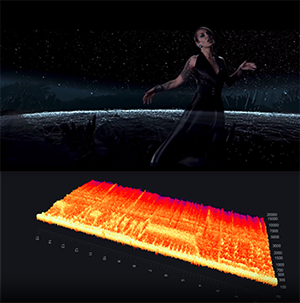

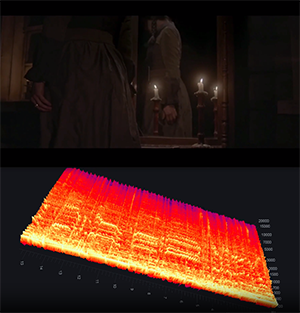

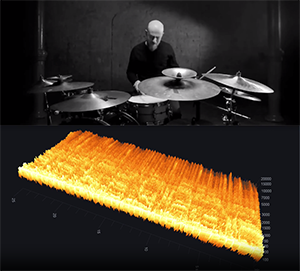

Media Example 2. “I Speak Astronomy,” Verse 1 – Prechorus – Chorus, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[5.9] Media Example 2 situates these sonic strategies in relation to the aesthetic materials and strategies of the music video treatment.(25) In the verse, Shmayluk’s sliding vocal is visually linked to her presentation in black clothing and heavy makeup, while the clipped, filtered (distorted) vocal response is demarcated by the post-production treatment of her head and shoulders image with black and white pixelation to evoke an analogous distorted effect. In the context of the body dimensions in the neighboring shots, this head and shoulders image stands out as larger than life. The prechorus, with the low-register and breathy delivery, is treated visually by shifting black and white pixelation over her body, now in a glamourous black satin dress with plunging neckline. The band members are no longer visible and the black backdrop includes points of light that suggest a star constellation. Shmayluk’s gently floating arm and hand gestures invoke a seductive or invitational address. For the dramatic shift to harsh metal screaming in the chorus, the video passage captures her in a more aggressive stance, often directly facing the camera, as compared to the profile or semi-profile shots (prechorus); she is no longer wearing the dress with plunging neckline and she stands in dynamic relationship to the band members. Over the course of the distinct song sections, the female subjectivity that is displayed is fragmented, distorted, unfixed, but also omniscient, while the music is ever changing, shifting in qualities and gestures.

Media Example 3. “I Speak Astronomy,” Bridge (phrase 1), sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

Media Example 4. “I Speak Astronomy,” Bridge (phrase 1), music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[5.10] The bridge section (mapped in Media Example 3) presents a new texture, characterized by the return of the

Media Example 5. “I Speak Astronomy,” Climactic Chorus, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[5.11] The song culminates in a final section of new material that functions as a terminally climactic chorus (Osborn 2013). Media Example 5 reveals a gradual shift from her dreamy chest register in the first statement of the climactic chorus (CC1) to an overdubbed statement in CC2, to a saturated belt in CC3. The first iteration of the material (CC1) is delivered in a metric alternation of

Media Example 6. “I Speak Astronomy,” Climactic Chorus, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[5.12] In the music video (Media Example 6), during the dreamy passage of CC1, Shmayluk’s giant, disembodied facial profile (in black and white) is presented in disproportion to her full body (in the black satin dress), while the background illuminates vast constellations and floating rocks; this scene thus juxtaposes a supernatural figure with a glamorous feminine body. The distant vocal delivery at the center of an ambient and detailed texture complements this visual portrayal of female strength and grace. Section CC2, with its galloping texture, situates the full band in an outdoor stage-like arrangement, with extraterrestrial rock formations and space technologies. Shmayluk now wears futuristic clothing—a tight suit in a shiny dark material—and slicked-back hair. Standing in the foreground in relation to the band members, she conveys authority and performative weight as her comfortable chest-range melody is treated to octave overdubbing, beginning to lead the voice to the upper range. The unified head-banging gestures and heavy delivery of guitars and kit lend support to that performative power. During this performance scene, the stars in the background begin to rise and the sky brightens, anticipating the emergence of a light source. As the cathartic culmination of the track, section CC3 offers an arresting scene to close the song. Following a five-second pause in the sound, with no image of the band, the performers reappear, now with a column of light rising behind them and with Shmayluk’s hand rising into the beam as she delivers her belted vocal in the upper octave. Here we witness the vocalist in a marked articulation of female vocal power at the front of band members performing their roles in conventional metal patterns.

“I Speak Astronomy”: Interpretive Conclusions

[5.13] In this music video, Shmayluk’s form is attributed otherworldly attributes as she transmits her message across time and space, yet there are moments when her human femininity is mobilized to create seductive effects. Her vocal expression shifts from persuasive to harsh to dreamy to belted, but across all expressive styles, her voice reverberates within the sonic space of the recording texture. Connecting to other progressive metal representations of supernatural figures, Shmayluk assumes this role herself and suggests an alternative to gendered assumptions about universal power. Not deified as a one-dimensional image of universal power, she is shown to be multi-faceted, in dynamic relationality to her band members, occupying an array of positions in the visual space of the video as well as in her vocal space. She is not reduced to a single archetypal category: in this single song, her performance (in words, music, and images) defines femininity in cosmic metal as at once seductive and aggressive, deified, and grounded. Her cultural gender maneuvering, from male progressive metal representations of cosmic power to this female representation, operates within a network of conventional meanings, but constitutes an alternative representation of strength that she claims for the female body.

Analysis II. Lament, Death, and Precarious Femininity

“Perennial” (Micro [EP], 2019)

[Track produced by Max Morton; Video directed by Shah Talifta]

Example 3. “Perennial,” Lyrics and Formal Structure

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[6.1] Shmayluk’s lyrics for “Perennial,” reproduced in Example 3 (Jinjer 2019d), are characterized by gothic symbols of lament and death, with the cycle of nature serving as an allegory for human loss. Despite the imagery of decay, in lines such as, “the autumn feels like a funeral,” the song closes with a cathartic sense of renewal and release. These lyrics connect strongly to song examples in death, doom, gothic, and progressive metal, for instance, with bands such as Opeth, Katatonia, October Tide, Evanescence, and Gojira. Opeth’s “Demon of the Fall” (My Arms, Your Hearse, 1998)—a significant instance of this gothic theme—sees the subject lamenting the loss of love while references to autumn winds and grey skies build a gloomy atmosphere. Katatonia’s “Velvet Thorns (Of Drynwhyl)” (Dance of December Souls, 1993) focuses on death and bereavement with a strong poetic reliance upon the natural elements to convey an emotional atmosphere; the line, “Through the ashes of a dying love, a new soul is born,” resonates profoundly as an intertext with the moment of catharsis in “Perennial”: “From the ashes of my roots, the new me will rise to live again.” Gojira’s “The Fall” (L’enfant sauvage, 2012) relies upon the themes of falling leaves and cold wind to explore the human need for strength in the face of disappointments and loss. By contrast, October Tide’s “Blue Gallery” (Rain Without End, 1997) offers no catharsis, but sees the subject lamenting his own death in the October rain, Daylight Dies’ “Dreaming of Breathing” (A Frail Becoming, 2012) laments an “atrophied soul,” and Evanescence’s “Bring Me To Life” (Fallen, 2003) invokes the cold and dark that have numbed the subject’s spirit into sleep.

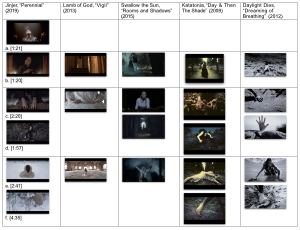

Example 4. Screenshots from “Perennial” in relation to the work of progressive metal, death metal, and death-doom bands

(click to enlarge)

[6.2] The “Perennial” music video features Shmayluk in four spaces: in vocal performance (Example 4a), spot-lit in a dark space; inside a candlelit country house, with old-fashioned décor and dress (Example 4b); outdoors in the dark of night, digging (Examples 4c and 4d); and ultimately outdoors in the bright snowy forest, wearing an ivory vintage dress with bare feet (Examples 4e and 4f). The representation of a sole female character, stylized to evoke a feminine form from the past, whose vulnerable body is exposed to harsh natural surroundings, is linked to the representations in male-fronted bands such as Lamb of God (groove metal/metalcore), Swallow the Sun (death-doom), Katatonia (alternative/death-doom), and Daylight Dies (death-doom). The gothic imagery in their videos (Example 4) is remarkably similar to that of “Perennial,” with visual codes and aesthetics that romanticize the past, showcase the contrast of light and dark, and represent female subjectivity as vulnerable and oppressed. In these videos, the long-haired female subjects wear old-fashioned dresses, they walk (and run in fear) through old buildings or forests, they are framed in darkness, their hands are represented in demure positions or reaching for help, and their feet are often bare to the elements. Within this discourse, the network of gendered meanings legitimate and ensure (Schippers 2007) the status of the female subject as overpowered and threatened by overbearing and dangerous forces. The following analysis illuminates what the members of Jinjer accomplish in their handling of this representational material.

[6.3] In addition to providing the lyrics, Example 3 maps the formal and expressive content of “Perennial.” Following a slow intro, a frenetic riff leads into a harsh verse, followed by a chorus; these sections are repeated with new lyrics and some musical transformations, followed by a unique bridge and a climactic chorus outro. As was the case in “I Speak Astronomy,” the formal structure is made more complicated by the contrasting clean and harsh vocals. In the latter song, energy increases as clean vocals for the verse and prechorus lead to a harsh chorus, which is later “resolved” in a clean delivery of the terminally climactic chorus group. Here, in “Perennial,” an intense riff and harsh verse lead into a clean chorus, which later culminates in a cathartic harsh delivery of the previously established chorus material. Let’s consider how this unfolds in the song and music video.

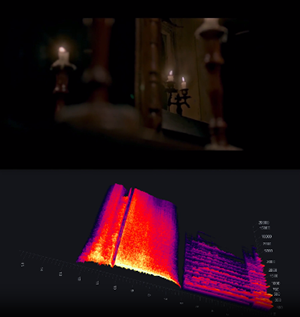

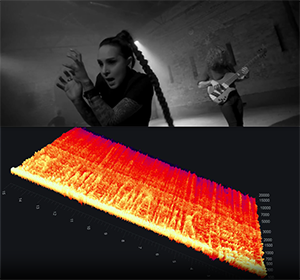

Media Example 7. “Perennial,” Slow Intro and Intro Riff, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[6.4] Media Example 7 presents both the slow intro and the frenetic intro riff section in the music video. A dark, whispered vocal and clean-toned guitar introduce the song, while we witness a reclining female subject in a candlelit room, wearing a long dark dress in a late nineteenth-century (Victorian) style. The sombre image of the subject, ominous whisper, and dissonant harmonic treatment expound the moody ode to autumn. An

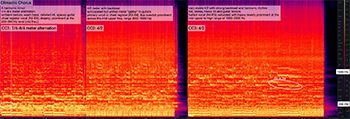

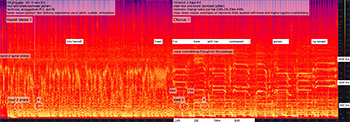

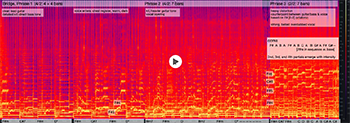

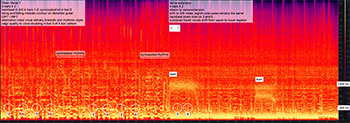

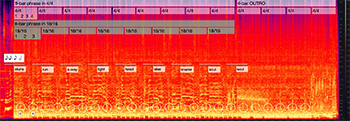

Media Example 8. “Perennial,” Harsh Verse 1 – Chorus 1, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[6.5] The musical intensity established by the riff section continues into harsh verse 1, for which the spectrogram image is annotated along with chorus 1 in Media Example 8. A metric shift to

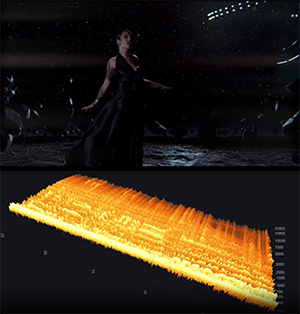

Media Example 9. “Perennial,” Harsh Verse 1 – Chorus 1, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[6.6] In the video treatment of harsh verse 1 and chorus 1 (Media Example 9), the woman in the candlelit scene and the headbanging vocalist continue as the primary subjects. The deep harsh vocal, aggressive riff, and headbanging image seem incongruous in relation to this figure, but as the scene develops, we understand the headbanging vocalist to be a shrewd narrator of this story. Shmayluk’s words call for a critical reflection on what is being represented here, especially with respect to femininity. Lyrically extolling the beauty of nature in its process of autumnal death, she explicitly identifies nature as female—as “spectacular” in her own suicide—while the female subject in the video (dressed in clothing that symbolizes a historical tradition of constrained femininity) is performing her beauty ritual, grooming and braiding her hair. Her deliberate gestures (scrutinized by her own gaze in the mirror) are attributed a solemn and foreboding quality by harmonic effects that are calculated to suggest and disrupt directional tonality. Contributing to the ominous effects, the candlelit scene is interrupted with Shmayluk’s image as performer, outdoors, where it is cold enough to cause the condensation of her breath. It is evident from this juxtaposition of two realities for female subjects (one constrained within the domestic sphere, the other with freedom of movement, yet exposed to the harsh elements) that the lyrical theme of death and the vulnerability of nature are metaphors for female experience.

Media Example 10. “Perennial,” Clean Verse – Harsh Verse 2 – Chorus 2, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[6.7] Media Example 10 provides the video sequence for the clean verse (based on the intro riff), harsh verse 2, and chorus 2. Continuing with the indoor scene, the subject prepares to go outside, putting on her shoes and ominously retrieving some digging tools. During this passage, material from the intro riff returns in a modified form to become a clean verse. Although the snare no longer articulates the frenetic sixteenth pattern, the role of syncopation now resides with the voice: against the crunchy dissonance of the harmonic pattern

Media Example 11. “Perennial,” Bridge, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[6.8] Media Example 11 annotates the spectrogram image of the lengthy bridge section. Returning to the atmospheric qualities of the intro, the first phrase features a clean lead guitar, detailed kit and direct bass tone in a progression (

[6.9] The harmonic tension in the bridge is complemented by the development of tension in the metric structure. Phrase 1 continues the symmetrical four-bar phrasing in

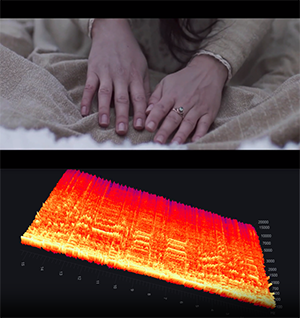

Media Example 12. “Perennial,” Bridge, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[6.10] This tension-building musical section connects to the video images, which situate the female subject in a completely new setting that creates a striking aesthetic contrast to the preceding scenes (Media Example 12). Just as the bridge begins, the video shifts to the image of a Shmayluk in a light-colored Victorian dress, sitting in a snowy forest during daylight hours. As the lyrics of phrase 1 reflect introspectively upon the cycle of destruction and restoration, the video subject kneels in the snow, surrounded by trees while the camera focuses on her elegant, feminine hand gestures and her slow rise to standing position. During phrase 2, which begins the process of metric destabilization, she spins with arms outstretched and dances barefoot through the snow; in keeping with her lyrical “confusion” and the vocal layering, the camera rotates, capturing an upward view of forest trees. Following the subject’s refuge in a suspended “breathless” state, the melismatic “coma” section begins with its heavier texture, metric shift to

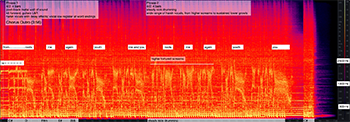

Media Example 13. “Perennial,” Chorus Outro, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[6.11] The tension that has developed to this point in the song and video culminates in the final chorus outro. The spectrogram of the passage is annotated in Media Example 13. Within a post-black metal wall of sound in guitars and kit (presenting the earlier

Media Example 14. “Perennial,” Chorus Outro, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[6.12] The music video images for the chorus outro, provided in Media Example 14, contribute to the cathartic effect of this climactic section. To begin the passage, Shmayluk, in her performing role, pounds her chest in the delivery of her first harsh words. The video treatment focuses primarily on the performing musicians, with sporadic quick cuts to the digging scene and the spinning scene in the forest. All of the images convey frantic movements and high energy until, ultimately, the figure in the forest stretches her arms and falls backward, the singer’s hands reach forward, and the digging figure is shown to be immersed in the ground, with only a hand emerging from the ground. With this final sequence, the narrative of “exhausted nature” as a metaphor for femininity arrives at its morbid conclusion: the female figures in the grave and in the snow are both shown to descend. The performing subject, however, remains as a defiant voice, asserting her own resistance to this narrative, and declaring that in this process of decay and rebirth, she will “rise to live again.”

[6.13] Shmayluk’s strategic mobilization of harsh vocals for this final statement reinforces her place as an extreme metal vocalist even while she critiques its patriarchal assumptions. In this regard, it is important to reflect upon the gendered practice of harsh vocalization and to appreciate the work of female vocalists to claim space in this discourse. Heesch interrogates this practice with the example of Angela Gossow (Arch Enemy), challenging the stereotype of aggression as a masculine trait. Identifying several ways in which the growling is associated with a male voice (low, dark, rough, aggressive), he argues that the “cultural presence of female growlers could potentially change our preconceptions about the gendering of vocal sounds with regard to pitch, roughness, and aggression” (Heesch 2018, 8). Shmayluk’s handling of vocal styles in “Perennial” certainly challenges the stereotype: by choosing to adopt a harsh style for the final chorus statement, she explicitly declares that a new femininity must “rise.”

“Perennial”: Interpretive Conclusions

[6.14] “Perennial” tells a story of loss and restoration through reference to the natural autumnal cycle, which is presented as a metaphor for female vulnerability. Here, Shmayluk offers a compelling critique of gothic femininity by connecting to the iconic imagery of death, doom, gothic, and progressive metal; she inserts herself into the role of exposed subject but at the same time performs her own role as a defiant and virtuosic extreme metal vocalist. Moving from domestic enclosure to harsh external conditions, the story casts a harsh light on female subjectivity within oppressive circumstances. Her vocal expression shifts from introspective serenity to critical growls, always claiming space and depth in the musical texture while she portrays herself in the role of the precarious female subject as well as the resistant critic, on the outside of the oppressive scene. The cathartic effect of the final chorus is brought about by the development of tension in the bridge—with its topics of “confusion” and “disillusion”—followed by Shmayluk’s remarkable harsh delivery of the climactic chorus material. Implicitly, the cycle of loss leads to rejuvenation, however the video images do not convey the restoration of an oppressive femininity; instead, that kind of femininity is buried in its own grave while Shmayluk looks on. With this song and its intertextual links to specific metal subgenres, she challenges the illusion of a beautiful, “natural,” gothic femininity and asks her spectators to critique its dark effects.

Analysis III. Fragile Subjects

“Pit of Consciousness” (Macro, 2019)

[Track produced by Max Morton; Video directed by Oleg Rooz]

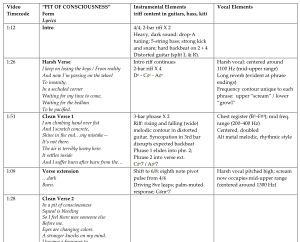

Example 5. “Pit of Consciousness,” Lyrics and Formal Structure

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[7.1] Turning now to “Pit of Consciousness,” I will begin, once again, with a few points about Shmayluk’s lyrics (Jinjer 2019c), reproduced in Example 5. On a thematic level, the song explores the subject’s internal mental struggles to hold onto sanity and reality, as well as the fragmentation and loss of self (e.g., “a stranger knocks on my mind”); the subject fears that in her mind, someone else is “setting snares for my soul.” Similar themes are developed in several key tracks by progressive and alternative metal bands; for instance, Meshuggah’s “Soul Burn” (1995), Korn’s “Insane” (2016), Gojira’s “The Cell” (2016), and Of Mice & Men’s “Pain” (2016). In an early Meshuggah example, “Soul Burn,” the subject asks, “who’s my mind” and “what’s real?”; he experiences “perpetual pain” as his “soul burn[s].” In Gojira’s “The Cell,” the subject is “locked inside” himself, while his brain is “overcrowded.” In the song “Pain,” Of Mice & Men also refer to “pressure in my brain,” while the subject is at the limit of the anguish he can experience. In “Insane,” Korn’s lyrical subject laments the loss of his soul while a destructive force is “growing deep within my head.” The topic of mental anguish—driven by the threat of mental and spiritual autonomy—connects these tracks, which are all presented in the genre contexts of progressive and/or alternative metal. Jinjer step effectively into this discourse, not only in the lyrical dimension, but also in the visual and musical realms.

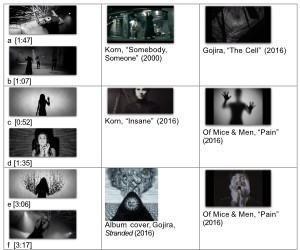

Example 6. Screenshots from “Pit of Consciousness” in relation to the work of progressive and alternative metal bands

(click to enlarge)

[7.2] Example 6 reproduces some screenshots from the video as well as images from the work of Korn, Gojira, and Of Mice & Men. The “Pit of Consciousness” video was shot in a space with an exposed lighting truss in the ceiling (Example 6a), with an anamorphic lens (evident in distant shots such as Example 6b) using a cinemascope aspect ratio. It is shot entirely in black and white, with minimalist lighting and an emphasis on dramatic contrast. Post-production effects are also important, as for instance with the fire that arises from the singer’s arms (Example 6e) and with the superposition of shots to suggest a fragmented subjectivity (Example 6h). Shmayluk is featured as three different figures, each with their own style and setting. At first, she performs in a large, atmospheric, empty space, in a long black dress, heavy boots, and a lengthy braid. A second style reveals her body to be more relaxed, with flowing hair, and gentle feminine contours that are silhouetted by back-lighting (Example 6c), although the light is sometimes cast upon her to show the irises of her eyes as extremely large and black (Example 6d). In the third setting, she is outdoors, in a white shirt and jeans; this scene leads to her immersion in water at the close of the video (Example 6i), from which position she delivers the final vocal line (Example 6j). Throughout the video, Shmayluk’s arm gestures convey her emotional state, sometimes with a high level of mental anguish as she clutches her head (Examples 6f and 6g).

[7.3] Several visual intertexts point to the bands mentioned earlier. An alternative metal style can be traced from her attire in the opening scene to Jonathan Davis’s long black dress and boots in Korn’s “Somebody, Someone.” Connections to Korn’s “Insane” also emerge, with its female figure whose eyes are blackened, and whose face is treated to superimposed images. Gojira’s “The Cell” features similar spatial and lighting aesthetics; also, the cover of the album on which “The Cell” appears (Stranded, 2016) features a stylized rising fire image that is similar to the post-production effect (Example 6e). Of Mice & Men’s “Pain” offers many striking connections, with the backlit body, the female body struggling on the floor, and the singer’s anxious hand gestures on his face. Returning to Daylight Dies’ “Dreaming of Breathing” (which was mentioned in connection to “Perennial”), the water immersion sequence at its close is remarkably similar to the closing water immersion sequence of “Pit of Consciousness.” With all of these connections, there is a significant distinction to be made: the fragmented and struggling subject in the narrative sequences is shown to be a woman, not a member of Korn, Of Mice & Men, or Daylight Dies, but an actress featured in the video as an object of the gaze. This is not unusual: metal bands often feature female characters in flight, in peril, and in struggle. By contrast, in Jinjer’s “Pit of Consciousness,” it is the singer who places herself into the role of the fragmented and struggling subject. Visually and lyrically, she writes this challenging role upon her own body, however she complicates and critiques the role by claiming musical and vocal resources that are not associated with a female body in such a vulnerable position.

[7.4] Returning to Example 5, the musical form is straightforward, based on an Intro–Verse–Chorus–Bridge–Chorus–Outro model (which Hudson 2021 identifies as the “normative” form in metal); however, unique content in each section leads to a progressive design in the musical narrative. Shmayluk’s vocal content occupies a dynamic relationship to a complex temporal (rhythmic and metric) structure, in addition to offering a range of expressive vocal qualities and strategies.

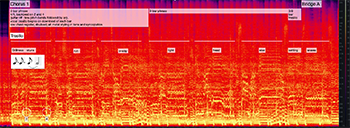

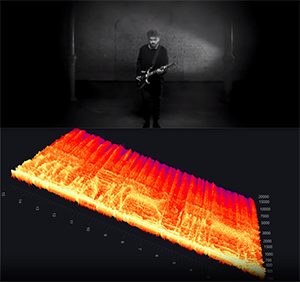

Media Example 15. “Pit of Consciousness,” Harsh Verse, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

Media Example 16. “Pit of Consciousness,” Harsh Verse, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.5] A brief intro establishes a heavy and dark two-bar guitar riff in

[7.6] The lyrics of this verse convey the subject’s feelings of isolation and anxiety, as well as the ominous threat of “insanity.” In the video treatment of this section (Media Example 16), the wide-angled lens isolates the singer in the center of the space, connecting to the theme of isolation in the lyrics. Her costuming is dark, dramatic, constraining, and modest (much like Jonathan Davis’s clothing shown in Example 6). Lighting effects and fog enhance the room depth and create a murky atmosphere. She is alone, while images of the band members are cut in from a different space. Fast Steadicam movement and editing, with blurred transition effects, suggest a state of disequilibrium and the choreography is tied closely to Shmayluk’s gestures, for instance as a strobe black and white inversion takes place on her high vocal scream at “bedlam.”

Media Example 17. “Pit of Consciousness,” Clean Verse 1 – Verse Extension, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.7] Contrasting the harsh verse, the subsequent clean verse offers new material, marked by the guitar’s rising and falling contour and Shmayluk’s change in vocal style. As evident in Media Example 17, she now delivers a repeated three-bar melodic phrase in her chest register (B3–

Media Example 18. “Pit of Consciousness,” Clean Verse 1 – Verse Extension, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.8] The lyrics of this section present themes of searching and struggling and the subject internalizes external forces, such as heavy air and fire. In the video images (Media Example 18), the singer is featured in a backlit silhouette, trapped behind glass (as in Of Mice & Men’s “Pain,” shown in Example 6). The theme of climbing in the lyrics is represented by her hands, with match on action shots as the image moves back and forth between the backlit figure and the figure in long black dress from the harsh verse. The fast pacing, camera angles, and movement communicate the turmoil and trauma of the subject’s suffering. Post-production techniques represent the burning fire that takes over her body.

Media Example 19. “Pit of Consciousness,” Chorus 1, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.9] The chorus returns to the previously established

Media Example 20. “Pit of Consciousness,” Chorus 1, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.10] The chorus lyrics convey the subject’s desire to take action, to move towards light. Her internal conflict intensifies as she struggles with a split identity (“in my head someone else”), and this conflicting identity entraps her, “setting snares.” The video images present the singer in white clothing in a natural environment, however an artificial spotlight from the left builds drama, as do the lightning strikes which are well coordinated to the music. Her hand gestures, reaching towards the light, are matched through quick cuts that return to the figure in the black dress (Media Example 20). As this subject interrogates her fractured identity, complemented visually by the changing representations of the subject (from the figure in the long dark dress, to the feminine silhouette, to the outdoor scene), it is fair to interpret the struggle as one that concerns female subjectivity. This interpretation is reinforced by the strong intertextual links to music videos by male-fronted alternative metal bands (identified in Example 6), where female actresses embody the unstable and split subjects while male musicians perform the song. With Shmayluk’s performance in “Pit of Consciousness,” she is both the performing musician and the fragile subject, appropriated and reclaimed from the existing metal discourse.

Media Example 21. “Pit of Consciousness,” Final Chorus, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.11] This interpretation is further reinforced through a strategic intensification of the final chorus material. Skipping past the bridge sections for the moment, I will turn to the final chorus, which is mapped with careful attention to its complex metric treatment in Media Example 21. Metal scholars have addressed the complexity of rhythmic and metric content, identifying metric uncertainty (Capuzzo 2018), rhythmic difficulty (Hannan 2018), and polymetric grooves (Hanenberg 2020) as characteristics of extreme and progressive metal. “Pit of Consciousness” illustrates these characteristics, with Shmayluk’s vocal expression contributing significantly to the resulting complex structure. In this final chorus statement, the voice again leads with the syncopated tresillo pattern (beginning with two dotted eighth notes), but now as an anacrusis rather than downbeat, while the pattern shifts in relation to a new polymetric patterning in which nine bars of

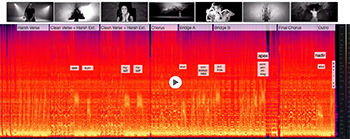

Media Example 22. “Pit of Consciousness,” Final Chorus, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.12] Let’s consider how this emerges in full multimodal expression of the video clip (Media Example 22). The lyrics once again suggest her desire to run while her internal conflict persists. With the final outro line (“waiting for my mind to be pacified”), we understand the subject to be waiting for the fragmentation to desist, but it does not. The outdoor figure is now seen to fall into water and descend. Cutting to the figure in the long dress, her gestures also suggest movement through water. The voicing of the final outro line is filmed under water and the song/video ends abruptly, with the female figure fully immersed.

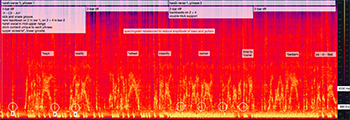

Media Example 23. “Pit of Consciousness,” Complete spectrogram of song with sound recording of Bridges A and B

(click to open in new tab)

Media Example 24. “Pit of Consciousness,” Bridge A, sound recording and spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.13] Media Example 23 provides sonic data for the complete song, a few of its key lyrics, and selected screenshots to create a summary snapshot of the overall narrative of “Pit of Consciousness”; this media example plays the two distinct bridge sections (now to be discussed), which present the subject in a crisis of deep fragmentation. As Shmayluk explores a range of expressive harsh vocals, a low growl on “soul” takes mid-range emphasis (centered at 700 Hz) while the scream on “outlines” carries into a much higher register (centered at 1300 Hz). Her highest scream at the word “compromising” is centered, at the peak level of 1400 Hz.

Before considering the music video images for these bridge passages, I would like to take a closer look at their complex metric design. Media Example 24 maps the patterning. Bridge A offers a polymetric groove (Hanenberg 2020), in which the kit establishes a two-bar pattern with strong backbeat in

Media Example 25. “Pit of Consciousness,” Bridge A and B, music video and 3D spectrogram

(click to open in new tab)

[7.14] Media Example 25 presents the music video for these bridge passages. Bridge A discloses the subject to be in a “dark place,” struggling to find a clear path through her own consciousness. The video shifts from the established images of Shmayluk (in the long dress, the back-lit figure, and the outdoor figure) in alternation with images of band members; compared with the previous sections, these shifts offer greater disruption to the visual continuity. Words, music, and images work together during this passage to convey a fragmented subject, as multiple layers operate to suggest her confounded and complicated sense of self. In bridge B, the lyrics evoke the theme of a vessel that is fragmented within (“outlines,” a “hive”). The multiple selves do not back down, do not become unified into one. Visually, the three different identities are shown in central positions, although with patterns that evoke fragmentation: the post-production fire effect, a shaking gesture, the superimposition of her image. As she sustains “compromising” at the apex point of her screams—while lying flat on the ground—this juxtaposition of extremes offers a contradictory simultaneity of vulnerability and incredible human strength. To put it ironically and possibly defiantly, this is a powerful scream from a “weak” female subject.

“Pit of Consciousness”: Interpretive Conclusions.

[7.15] How does Shmayluk claim performative space and embody the complex subjectivity that emerges in this song and video? The contrast between clean and harsh vocals, a feature of the subgenre of metalcore, is one of her most striking strategies to convey the subject’s struggle. In her treatment of this technique, each clean vocal section elides into a harsh vocal section, with those moments of elision delivering a marked contrast of timbre and register. The clean vocal sections are challenging in their own right, due to their rhythmic and polymetric complexity—typical of progressive metal—as Shmayluk gradually moves further out of metric phase over the course of the song. Her harsh vocals convey the turmoil of the subject, rising to a screamed apex on “compromising” in bridge B and descending to a growled nadir on “soul” at the end of the final chorus. Both moments—scream and growl—offer space for the expression of a troubled subject. Shmayluk assumes this subjectivity not only in her musical, but also her visual, performativity. As she descends into the water, the musical content is at its most complicated and fragmented. The subject remains split, struggling with multiple identities, however she does not occupy this space passively but rather delivers her deep, growling vocals from the water. This image is in marked contrast to those of the videos by male-fronted bands mentioned earlier (Korn; Of Mice & Men; Daylight Dies) in which the female actors are not attributed vocal space. Shmayluk’s performative expression in words, music, and images conveys a multi-dimensional representation of femininity and a willingness to represent human struggle while not capitulating to the archetype of a weak female. I would suggest this to be a distinction of female metal singer subjectivity more generally and Shmayluk’s intervention more specifically: she is not merely a visual asset in the music video, but rather a performer who embodies, critiques, and transforms the roles that are being represented.

Conclusion

[8.1] At the level of genre, Tatiana Shmayluk and the band members of Jinjer offer a unique intersection of extreme metal, metalcore, alternative metal, and progressive metal elements. In dialogue with their lyrics and images, this unique genre blend creates space for the negotiation of alternative femininities. Shmayluk claims that performative space in words, music, and images to deliver compelling narratives that feature and problematize powerful, vulnerable, and destabilized female subjectivities. Establishing herself as a crucial actor in progressive metal, she emerges as a dynamic performer in relation to her band, however she is also shown in costumed roles of various sorts, with complex dialogues emerging between the video images of Shmayluk performing with the band and Shmayluk as costumed figure. Consistently, she embodies—in the expressive channels of words, music, and images—representations of femininity that are salient within metal music cultures, but that she demonstrates to be deserving of critique and transformation.

[8.2] It is important for female performers to have the full toolkit of emotional expression available to them, including expressions of strength, aggression, vulnerability, and pain. These expressions are not the domain of masculinity alone—although typically attributed as such—but female metal artists can and do accomplish the necessary cultural gender maneuvering (Schippers 2007) to confuse notions about male and female voices (Heesch 2018) and to destabilize gender stereotypes. With this paper, I have situated Tatiana Shmayluk’s multimodal expression in relation to the work of comparable metal bands to illuminate—through the detailed analysis of the content and expression of her work—how she complicates and transforms the conventional understanding of gendered subjectivities in metal music. With hundreds of active female metal vocalists, a great deal of work remains to be done to know and understand what these artists can and do bring to the genre of metal music.(31)

Lori Burns

University of Ottawa

School of Music

50 University Private

Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5

Canada

laburns@uottawa.ca

Works Cited

Allain, Florence. 2018. Musiques extrêmes, sexe et orientation sexuelle: la culture Métal face au genre: de 1970 à nos jours. PhD diss., Paris 1. http://www.theses.fr/2018PA01H028.

Arnett, Jeffery Jensen. 1996. Metalheads: Heavy Metal Music and Adolescent Alienation. Westview Press.

Auslander, Philip. 2004. “I Wanna Be Your Man: Suzi Quatro’s Musical Androgyny.” Popular Music 23 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143004000030.

Barron, Lee. 2013. “Dworkin’s Nightmare: Porngrind as the Sound of Feminist Fears.” In Heavy Metal: Controversies and Countercultures, ed. Titus Hjelm, Keith Kahn-Harris, and Mark Levine, 66–82. Equinox.

Beebe, Roger, and Jason Middleton, eds. 2007. Medium Cool: Music Videos from Soundies to Cellphones. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv123x5x2.

Bennett, J. 2019. “From Warzones to Mosh Pits: The Evolution of Jinjer’s Tatiana Shmailyuk.” Revolver, April 2. https://www.revolvermag.com/music/warzones-mosh-pits-evolution-jinjers-tatiana-shmailyuk.

Berkers, Pauwke, and Julian Schaap. 2018. Gender Inequality in Metal Music Production. Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781787146747.

Biamonte, Nicole. 2014. “Formal Functions of Metric Dissonance in Rock Music.” Music Theory Online 20 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.20.2.1.

Borthwick, Stuart, and Ron Moy. 2004. Popular Music Genres: An Introduction. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474428767.

Burns, Lori. 2019. “Dynamic Multimodality in Extreme Metal Performance Video: Dark Tranquillity’s ‘Uniformity,’ Directed by Patric Ullaeus.” The Bloomsbury Handbook to Popular Music Video Analysis, ed. Lori Burns and Stan Hawkins, 183–200. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501342363.ch-011.

—————. 2020a. “Understanding Gender and Sexuality in Rock Music Discourse.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Rock Music Research, ed. Allan F. Moore and Paul Carr. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501330483.ch-028.

—————. 2020b. “Femininity and Vocal Subjectivity in Metal: Floor Jansen’s Negotiations of Expressive Space.” Keynote Address, International Association of the Study of Popular Music, UK and Ireland, June 20, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Vo7FRCl3j0&t=2s.

—————. 2020c. “Intersections of Gender, Race, and Genre: Cammie Gilbert and Black Female Subjectivity in Metal Music.” American Music Perspectives 1 (2): 98–118. https://doi.org/10.5325/ampamermusipers.1.2.0098.

—————. 2022. “Framing the Female Voice in Doom Metal: Formal and Sonic Elements in The Gathering’s ‘Strange Machines’ (Mandylion, 1995).” In Analyzing Recorded Music: Collected Perspectives on Popular Music Tracks, ed. William Moylan, Lori Burns, and Mike Alleyne, 323–38. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003089926-27.

Burns, Lori, and Stan Hawkins, eds. 2019. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music Video Analysis. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501342363.

Burns, Lori, and Serge Lacasse, eds. 2018. The Pop Palimpsest: Intertextuality in Recorded Popular Music. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9755813.

Burns, Lori, Alyssa Woods, and Marc Lafrance. 2015. “The Genealogy of a Song: Lady Gaga’s Musical Intertexts on The Fame Monster (2009).” Twentieth-Century Music 12 (1): 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478572214000176.

Capuzzo, Guy. 2004. “Neo-Riemannian Theory and the Analysis of Pop-Rock Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 26 (2): 177–200. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2004.26.2.177.

—————. 2018. “Rhythmic Deviance in the Music of Meshuggah.” Music Theory Spectrum 40 (1): 121–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mty005.

Chaker, Sarah, and Florian Heesch. 2016. “Female Metal Singers.” In Heavy Metal, Gender and Sexuality, ed. Florian Heesch and Niall Scott, 133–44. Routledge.

Clifford-Napoleone, Amber. 2015. Queerness in Heavy Metal Music: Metal Bent. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315851723.

Connell, Raewyn W. 1987. Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics. Polity Press.

—————. 1995. Masculinities. University of California Press.

Connell, Raewyn W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender and Society 19: 829–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639.

Cope, Andrew L. 2010. Black Sabbath and the Rise of Heavy Metal Music. Ashgate.

De Clercq, Trevor. 2016. “Measuring a Measure: Absolute Time as a Factor for Determining Bar Lengths and Meter in Pop/Rock Music.” Music Theory Online 22 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.3.3.

Diehl, Aurore. 2013. “Write of the Valkyries: An Analysis of Selected Life Narratives of Women in the Heavy Metal Music Subculture.” Master’s Thesis, University of New Mexico. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/11.

DiGioia, Amanda, and Lyndsay Helfrich. 2018. “‘I’m Sorry, but it’s True, You’re Bringin’ on the Heartache’: The Antiquated Methodology of Deena Weinstein.” Metal Music Studies 4 (2): 365–74. https://doi.org/10.1386/mms.4.2.365_1.

DiVita, Joe. 2019. “Ukraine's Jinjer Unleash Brutal + Reflective New Song ‘Perennial.’” Loudwire, January 10. https://loudwire.com/jinjer-new-song-perennial/.

Foucault, Michel. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. Pantheon Books.

FrontView Magazine. 2016. “Jinjer Releases King of Everything.” FrontView Magazine, July 12. https://www.frontview-magazine.be/en/news/jinjer-releases-king-of-everything.

Garza, Jose M. 2021. “Transcending Time (Feels): Riff Types, Timekeeping Cymbals, and Time Feels in Contemporary Metal Music.” Music Theory Online 27 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.27.1.3.

Graff, Gary. 2019. “Ukrainian Metal Band Jinjer Delivers on Its Promise with New Album 'Macro'.” Billboard, November 1. https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/rock/8541798/jinjer-macro-album-interview.

Gruzelier, Jonathan. 2007. “Moshpit Menace and Masculine Mayhem.” In Oh Boy! Masculinities and Popular Music, ed. Freya Jarman-Ivens, 59–75. Routledge.

Hainaut, Bérenger. 2020. “Des vocalités « bestiales »? Caractériser les voix bruitées du black metal.” Volume ! 16 (2)/17 (1): 145–61. https://doi.org/10.4000/volume.8008.

Halberstam, Jack. 1998. Female Masculinity. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822378112.

Hannan, Calder. 2018. “Difficulty as Heaviness: Links Between Rhythmic Difficulty and Perceived Heaviness in the Music of Meshuggah and The Dillinger Escape Plan.” Metal Music Studies 4 (3): 433–58. https://doi.org/10.1386/mms.4.3.433_1.

Hanenberg, Scott J. 2020. “Using Drumbeats to Theorize Meter in Quintuple and Septuple Grooves.” Music Theory Spectrum 42 (2): 227–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtaa005.

Heesch, Florian. 2018. “‘Voice of Anarchy’: Gender Aspects of Aggressive Metal Vocals. The Example of Angela Gossow (Arch Enemy).” Criminocorpus (Revue) 11. https://doi.org/10.4000/criminocorpus.5726.

Hill, Rosemary Lucy. 2016. Gender, Metal and the Media: Women Fans and the Gendered Experience of Music. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-55441-3_7.

—————. 2018. “Metal and Sexism.” Metal Music Studies 4 (2): 265–79. https://doi.org/10.1386/mms.4.2.265_1.

Hillier, Benjamin. 2020. “Considering Genre in Metal Music.” Metal Music Studies 6 (1): 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1386/mms_00002_1.

Hudson, Stephen. 2021. “Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Metal.” Music Theory Online 27 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.27.1.5.

—————. 2022. “Bang Your Head: Construing Beat through Familiar Drum Patterns in Metal Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (1): 121–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtab014.

Hutten, Rebekah, and Lori Burns. 2021. “Beyonce’s Black Feminist Critique: Multimodal Intertextuality and Intersectionality in ‘Sorry.’” In Beyoncé in the World: Making Meaning with Queen Bey in Troubled Times, ed. Christina Baade and Kristen McGee, 313–38. Wesleyan University Press.

Jocson-Singh, Joan. 2019. “Vigilante Feminism as a Form of Musical Protest in Extreme Metal Music.” Metal Music Studies 5 (2): 263–73. https://doi.org/10.1386/mms.5.2.263_1.

Kahn-Harris, Keith. 2016. “Coming Out’: Realizing the Possibilities of Metal.” In Heavy Metal, Gender and Sexuality: Interdisciplinary Approaches, ed. Florian Heesch and Niall Scott, 39–54. Routledge.

Kartheus, Wiebke. 2015. “The ‘Other’ as Projection Screen: Authenticating Heroic Masculinity in War-Themed Heavy Metal Music Videos.” Metal Music Studies 1 (3): 319–40. https://doi.org/10.1386/mms.1.3.319_1.

Kemble, Katrice. 2019. “Sex Metal Barbies: Feminism and Frontwomen in the Alternative Metal Scene.” MA thesis, Wesleyan University.

Kennedy, Lewis F. 2017. Functions of Genre in Metal and Hardcore Music. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Klein, Michael L. 2005. Intertextuality in Western Art Music. Indiana University Press.

Kozak, Mariusz. 2021. “Feeling Meter: Kinesthetic Knowledge and the Case of Recent Progressive Metal.” Journal of Music Theory 65 (2): 185–237. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-9143190.

Krenske, Leigh, and Jim McCay. 2000. “‘Hard and Heavy’: Gender and Power in a Heavy Metal Music Subculture.” Gender, Place, and Culture 7 (3): 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/713668874.

Kummer, Jenna. 2016. “Powerslaves? Navigating femininity in heavy metal.” In Heavy Metal Studies and Popular Culture, ed. Brenda Gardenour Walter, Gabby Riches, Dave Snell, and Bryan Bardine, 145–66. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lafrance, Marc, and Burns, Lori. 2017. “Finding Love in Hopeless Places: Complex Relationality and Impossible Heterosexuality in Popular Music Videos by Pink and Rihanna.” Music Theory Online 23 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.2.5.

Lucas, Olivia R. 2018. “‘So Complete in Beautiful Deformity’: Unexpected Beginnings and Rotated Riffs in Meshuggah’s obZen.” Music Theory Online 24 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.24.3.4.

Machin, David. 2010. Analysing Popular Music: Image, Sound, Text. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446280027.

McCandless, Gregory. 2013. “Metal as a Gradual Process: Additive Rhythmic Structures in the Music of Dream Theater.” Music Theory Online 19 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.19.2.2.

Messerschmidt, James W. 2004. Flesh and Blood: Adolescent Gender Diversity and Violence. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Moylan, William. 2020. Recording Analysis: How the Record Shapes the Song. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315617176.

Nobile, Drew. 2022. “Teleology in Verse-Prechorus–Chorus Form, 1965–2020.” Music Theory Online 28 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.28.3.8.

Nordström, Susanna, and Marcus Herz. 2013. “‘It’s a Matter of Eating or Being Eaten’: Gender Positioning and Difference Making in the Heavy Metal Subculture.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 16 (4): 453–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549413484305.

Osborn, Brad. 2010. “Beats that Commute: Algebraic and Kinesthetic Models for Math-Rock Grooves.” Gamut 3 (1): 43–68.

—————. 2013. “Subverting the Verse–Chorus Paradigm: Terminally Climactic Forms in Recent Rock Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 35 (1): 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2013.35.1.23.