The Turn in the Finale of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony as Allusion to Wagner’s Parsifal*

Genevieve Robyn Arkle

KEYWORDS: Mahler, Wagner, intertextuality, ornamentation

ABSTRACT: The finale of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony is saturated with turn figures. More than a traditional Baroque embellishment, in this movement the turn establishes a densely motivic role while simultaneously, on three occasions, functioning as an allusion to the Heilandsklage motive (the “Savior’s Lament”) of Wagner’s Parsifal. Yet despite the wealth of literature on Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, the turn figure has been almost entirely overlooked in Mahler studies, both as motivic device and intertextual reference. This article fills this gap and provides a detailed investigation into the role of the turn in the finale of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony as both a motive and allusion to Wagner’s Heilandsklage. It begins by exploring Mahler’s relationship with Wagner’s last drama before examining the appearance of the Heilandsklage motive in Mahler’s songs and symphonies more broadly. Following this, it embarks on a detailed investigation into the turn in the finale of the Ninth Symphony and offers a fundamental rethinking of the turn, not simply as a musical ornament, but as a tool for musical and intertextual meaning in Mahler’s and Wagner’s works.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.1.1

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

“The question is still open as to what [the turn figure in Mahler’s Ninth] has to say. But it is unmistakable that it is of unprecedented importance, so much so that next to it, everything else almost dissolves into nothingness.”(1) (Ries 1989, 66)

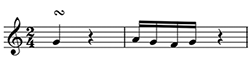

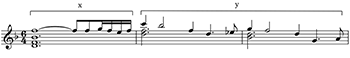

Example 1. Wagner’s Parsifal, Act I Prelude, mm. 99–100: first appearance of the Heilandsklage motive

(click to enlarge)

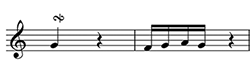

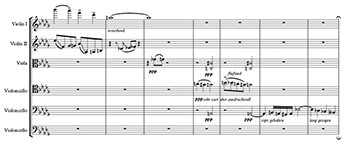

Example 2. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 1–4

(click to enlarge)

[1.1] Those who are familiar with the finale of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony will already be aware of the ubiquitous presence of the turn figure. It appears as a recurring motive across all four movements of the symphony before taking on a particularly striking role in the Adagio finale. Appearing in 82 of the movement’s 185 measures, the turn figure emerges in Mahler’s movement 125 times in various rhythmic variations and in all orchestral parts (save for infrequently used instruments such as the piccolo,

[1.2] The appearance of this Wagnerian motive in Mahler’s work prompts a question about the purpose of the turn not only as a central motivic idea but as a tool for musical expression. Scholars including Julian Johnson (2009), Hans Ries (1989), Kurt von Fischer (1975), Anna Stoll Knecht (2017), and Vera Micznik (1989, 2020) have all acknowledged the figure and hinted at its role in Mahler’s works. For Johnson, Mahler’s turns are full of vocality, indicative of an opera aria, emulating the turn figures commonly found at the end of a vocal cadenza (2009, 278).(4) Meanwhile, both Ries (1989, 64) and Fischer (1975, 99–105) have theorized that Mahler’s turn figures are indebted to the turns of Wagner’s Verklärungsfigur from Tristan und Isolde, where the figure is intimately connected to sentiments of life, love, and transfiguration through death (Arkle 2023). The notion of Mahler’s turns being in some way affiliated with Wagner’s is also briefly commented on by Stoll Knecht in her study of the allusions to Parsifal in Mahler’s First and Second Symphonies: “Several passages in Mahler’s symphonies can be heard as reminiscences of Parsifal—the last movement of the Third Symphony

[1.3] This article fills the gap highlighted by Micznik and offers an investigation into the role of the turn in the finale of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. It has two primary goals: it provides a reading of the finale from the perspective of the turn figure, examining the role it plays in the overall construction of Mahler’s movement, and it investigates the turn as an allusion to Wagner’s Heilandsklage motive, offering a contribution to the growing body of literature on Wagnerian allusions in Mahler’s songs and symphonies.(5) I begin this article by discussing Mahler’s relationship with Wagner’s works, specifically focusing on his role as a prolific Wagnerian conductor and his encounters with Parsifal. This section introduces the turn figure as a musical ornament and expressive device before briefly discussing how the turn is used more broadly in Mahler’s and Wagner’s works, taking Wagner’s Heilandsklage motive, Mahler’s Third and Tenth Symphonies, and “Der Abschied” from Das Lied von der Erde as case studies. The remainder of the article offers a detailed investigation of the turn in the finale of the Ninth Symphony, using the three appearances of Wagner’s Heilandsklage motive to anchor the investigation. In doing so, this article seeks to contribute to the growing body of literature on Mahler’s Wagnerian allusions while also providing a fresh perspective on one of Mahler’s most popular and enigmatic finales.

2. Mahler, Parsifal, and the Turn Figure

[2.1] Throughout his life, Mahler cultivated a keen interest in Wagner’s music and aesthetics. He remained a devoted Wagnerian until the day he died, even writing to his sister Justine in 1894 that he felt Wagner “belonged a little bit to my family” (2006, 373).(6) In July 1883, he traveled to Bayreuth, undertaking his own “pilgrimage,” to see Parsifal performed under the baton of conductor Hermann Levi.(7) Following this initial pilgrimage, Mahler was fortunate to spend much time in Wagner’s city. In 1891 he saw three performances of Tannhäuser and two of Parsifal (La Grange 1974, 236), and a few years later, in March 1894, he was requested by Cosima Wagner to assist the tenor Willi Birrenkoven in learning the role of Parsifal for his upcoming engagement in Bayreuth.(8) Mahler stayed in Bayreuth for the summer of 1894 to hear Birrenkoven perform his Parsifal under Richard Strauss’s baton, during which time he also attended performances of Tannhäuser and Lohengrin while seated in the Wagner family box (Mahler 1994, 27).(9) However, despite his proficiency as a Wagnerian conductor (conducting a total of 514 performances of Wagner’s operas during his lifetime), he was never invited to conduct Parsifal in Bayreuth (Peattie 2015, 41). He did, however, perform sections of the work in concert outside of Bayreuth. In February 1886, Mahler was the first to perform sections of the work, specifically the “Transformation music” and the final scene with chorus, in concert in the German Theater in Prague to commemorate the anniversary of Wagner’s death.(10) In 1887 Mahler took to the podium again to conduct passages of Parsifal in concert in Leipzig, performing the final scenes of Act I and Act III (2009, 43). Additionally, Mahler conducted sections of it twice in New York: the Prelude in March 1910 (at Carnegie Hall), and the Prelude and finale to Act III in January 1911 (La Grange 2008, 1611).(11)

[2.2] The close relationship that Mahler maintained with the music of Parsifal undoubtedly influenced his compositional style, as his music has often been criticized for its frequent allusions and borrowings from the music of his contemporaries and predecessors, as well as for its references to “popular and plebian” musical styles (Hefling 1997, 125). In recent years, there has been an increase in literature that aims to consider the references to Wagner’s music dramas in Mahler’s songs and symphonies, yet there is still a wealth of allusions that have yet to be uncovered and explored. One such allusion that remains unexcavated is Mahler’s use of the turn figure.

Considering the Turn Figure

Example 3. Standard turn; symbol and notation

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. Inverted turn; symbol and notation

(click to enlarge)

[2.3] The current body of literature concerning the turn figure is based primarily in the field of performance practice, with the majority of studies examining the turn as a Baroque ornamental embellishment and considering how it should be performed in various notational contexts.(12) Originally termed “Groppo” or “gruppetto,” the turn figure can be traced back to French and Italian instrumental tablature from the beginning of the sixteenth century; following its integration into the music of the time, it quickly came to be considered one of the most “pleasing of musical graces,” requiring delicacy and taste in its performance (Russell 1894, 28). The figure, known as the “standard turn” in literature on Baroque ornamentation, is described by Frederick Neumann as “the collective name for a group of graces that is related to one principal design . . . in which three ornamental notes start on the upper neighbor of the parent note and move scalewise to the lower one” (1978, 465). The turn figure also commonly appears in inversion and can be notated either by the symbol, in full notation, or in grace notes (see Examples 3 and 4).

[2.4] One of the fundamental features of the turn is its ability to create and resolve dissonance. Up until the 1600s, the vast majority of musical ornaments were strictly melodic, providing an improvisatory embellishment to a melody or phrase. However, Neumann argues that by the early stages of the seventeenth century, musical ornaments started to take on a more expressive role through the use of dissonance, allowing them to have an effect not only on the melody but also on the surrounding harmony. The appoggiatura became one of the first of these “harmonic” ornaments, as the delayed melodic resolution and creation of a suspension against the chord allowed the appoggiatura to use melody to create inherent harmonic conflict (Neumann 1988, 73). This same creation and resolution of harmonic tension from the appoggiatura is similarly found in the turn figure, as the turn functions as two appoggiaturas (one falling, one rising), one after another. This relationship between the two figures is characterized in the German terms for the figure, Vorschlag ( “appoggiatura,” or literally “pre-beat”) and Doppelschlag (“turn,” or literally “double-beat”), the latter implying that the turn is quite simply a double version of the appoggiatura. Yet just as not every descending or rising second is an appoggiatura, not every turn figure functions as a “harmonic” ornament, as it ultimately depends on where the weight or accent lies in the figure. Robert Donnington has differentiated between these harmonic and melodic turns by labeling the figures as either “accented” or “unaccented” turns. He writes,

The accented upper turn and the accented lower turn both serve a harmonic as well as a melodic function because their initial note, which receives the accent, is foreign to the harmony given by their main note, and often discordant with it. The accented main-note turn and all the unaccented turns are primarily melodic, and are more or less unstressed. (1963, 210–11)

These harmonic figures, as outlined above, are naturally more expressive than their melodic counterparts, as they provide a sense of discomfort through the creation and resolution of dissonance. It therefore becomes possible to distinguish between turn figures that are melodic and those that offer more substantial and meaningful contributions to a phrase based on their ability to manipulate and contribute to the underlying harmony.(13)

[2.5] The figure’s inherently expressive or animated character also stems from its rhythmic adaptability. The use of the turn symbol in the Baroque period allowed for greater rhythmic manipulation from the performer, enabling them to enhance the moments of chromaticism or harmonic tension created by the turn’s melodic shape. This perspective is clearly adopted by Hans Ries, who argues that the turn’s expressive nature rests primarily on its improvisatory origins and that it was through improvisation that the figure was brought to life as a tool for the expression of musical meaning (1989, 61–62). However, in the early stages of the nineteenth century many composers opted to retire the symbol in favor of writing the figure in full notation.(14) Of this change in notation, Frederick Neumann writes, “all ornaments are born of improvisation and as such they were born free, yet many modern writers endeavored to deprive them of their freedom and put them into narrow cages.” He continues his rather theatrical interpretation by comparing the restrictions of the ornament to the famous opening sentence of Rousseau’s Du contrat social: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains,”(15) with Neumann requesting that we consider exchanging the word “man” with “ornaments” (1988, 72). Yet, contrary to Neumann’s belief, this change in notation does not diminish the expression of the figure but instead allows for its expression to be used more intentionally. This becomes increasingly evident when we consider the turn’s adaptation into motivic contexts, as composers chose to draw on the turn’s creation of harmonic tension to intensify the expression of a musical passage, phrase, or motive. This trend emerged prominently in the nineteenth century, with the turn figure frequently becoming embedded into the fabric of a musical work rather than functioning as a mere decoration to a phrase.(16)

The Turn in Mahler’s and Wagner’s Works

Example 5. Wagner, Rienzi, Act V, sc. i, Rienzi’s Prayer aria: inverted turn figures

(click to enlarge)

Example 6. Wagner, Tristan, Act III, Isolde’s Liebestod: the Verklärungsfigur

(click to enlarge)

[2.6] Mahler’s and Wagner’s works function as a privileged space for examining the motivic role of the turn figure in the nineteenth century. For Wagner, from the early works such as Rienzi and Lohengrin to Tristan and Parsifal, the turn establishes itself as a central component of his motivic vocabulary. In the early dramas such as Rienzi, Wagner takes influence from the more traditional aspects of the figure—using the symbol rather than writing the turn in full notation—where it appears as a recurring musical device in passages that are affiliated with traditional, liturgical, or religious narratives.(17) Although easily dismissed as just a decorative embellishment, the turn and its subsequent descending phrase in Rienzi (Example 5) closely resemble the Verklärungsfigur motive of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (Example 6), therefore inviting a more motivic interpretation (Examples 5 and 6) (see Arkle 2023).

[2.7] The turn also develops as a principal figure in Wagner’s Lohengrin, most notably in Elsa’s Procession to the Cathedral (Act II, sc. iv). Appearing for the first time in the Act I Prelude, the turn is enveloped into the central themes of the drama, acting as a precursor to Wagner’s leitmotivic techniques, which would be firmly established in the Ring Cycle. However, by the time the turn is used in Parsifal, the frequency and prominence with which Wagner employs the turn figure undergoes a vast transformation, with the turn materializing in five of the work’s central motives: the Heilandsklage, the Wehelaute, the Waldesrauschen, the Karfreitagfigur, and the Totenfeierthema.(18) And, as their motive names suggest, the turn is used in leitmotivic and narrative contexts pertaining to themes of sighing, sorrow, or religious suffering. Although it is the Heilandsklage motive that is of primary interest for the study of the Ninth Symphony, the recurring nature of the turn figure in Wagner’s motives across many of his music dramas helps to firmly establish it as a valuable tool for expression.

[2.8] Similarly, the turn takes on a central role in many of Mahler’s songs and symphonies. From the Second Symphony until the final movement of the unfinished Tenth, turn figures can be found embedded into his works; however, of particular concern are those that function as allusions to Wagner’s turn motives, specifically Parsifal’s. The following section therefore focuses on the Wagnerian turn allusions in the Third Symphony, “Der Abschied” from Das Lied von der Erde, and the Tenth Symphony.

Example 7. Mahler, Third Symphony, Finale, mm. 205–12

(click to enlarge)

[2.9] Save for the Ninth Symphony, one of the most prominent examples of turn figures in Mahler’s works can be found in the finale of the Third Symphony (1896). The movement was titled “What Love Tells Me” in the supporting programmatic literature, and Mahler described it as “a summary of my emotions about all creatures” (1996, 127). Throughout the movement, the turn appears in both standard and inverted form as a key motive of the recurring A section. In addition to these A section turns, a rather more important turn figure is employed on four occasions in the movement, offering a clear allusion to the Heilandsklage motive of Parsifal.(19) These passages (mm. 210–11, 227–28, 280–28, and 290–91) offer an accented quintuplet turn figure followed by the interval of a minor third and a descending diatonic four-note scale, almost directly quoting the Heilandsklage motive (and subsequently, acting as a precursor to the motive at the opening of the finale of the Ninth Symphony). The first instance is shown in Example 7.

[2.10] Although from the title of the movement alone there appears to be no obvious connection between the themes of Parsifal and the religious, lamenting, or redemptive associations implied by the turn figure in the Heilandsklage, a rethinking of Mahler’s understanding of love in this context can help in viewing the work through a different, more religious lens. In a letter to Anna Bahr-Mildenburg in July 1896, Mahler wrote of the finale, “I could just as well call the movement ‘What God tells me,’ and indeed, just in the sense that God can only be grasped as Love” (1996, 108). Similarly, William McGrath writes of this movement, “in terms of the symphony’s philosophic structure this is the movement in which the struggling life force at least finds rest, resolution, and salvation in reunion with the divine essence of nature

Example 8. Mahler, “Der Abschied,” Das Lied von der Erde, mm. 84–90

(click to enlarge)

[2.11] Another prominent Heilandsklage reference emerges in Mahler’s lamenting “Der Abschied” from Das Lied von der Erde. In m. 87, the first horns offer a quintuplet turn followed by a triplet descending scale beginning a fifth higher than the final note of the turn in the following measure (labeled “x” in Example 8). This quintuplet turn is revived four measures before rehearsal number 17 in the solo cello line and again in the first violin at rehearsal number 17, accompanying the text “Um im Schlaf vergessnes Glück, Und Jugend neu zu lernen!”(20) The use of the eighth-note-quintuplet rhythm and the four-note descending scale provides a compelling parallel to the turn motives of the Third Symphony, which, aside from the leap of a fifth and the scale’s chromaticism in the “Abschied” figure, are nearly identical. Of course, both motives also function as an allusion to Wagner’s Heilandsklage theme, which, although not using the same quintuplet rhythm, provides the same standard turn followed by a descending scale beginning a minor third higher than the final note of the turn. The appearance of the Heilandsklage motive in a movement so clearly associated with notions of loss and farewell is perhaps not surprising. What is perhaps more curious is the fact that the figure predominantly appears in the finales of three of Mahler’s works: the Third, “Der Abschied,” and the Ninth. Although these final movements present a wide variety of moods, it seems significant that a figure and theme intimately associated with the notions of sighing, lamenting, and religious suffering should be used so consistently in Mahler’s final movements. In the finale of the Third Symphony, the quintuplet turn appears intimately connected to the traditions of Parsifal and the suffering and redemption inherent to the work’s narrative, while in “Der Abschied,” pain is embedded within the “farewell” of the work, with the figure appearing as the singer describes the world and all mortal desires as they transition from life into the dreams of youth found only through sleep.

Example 9. Mahler, Tenth Symphony, I,

(click to enlarge)

Example 10. Wagner, Parsifal: the extended Waldesrauschen motive

(click to enlarge)

[2.12] The final example of Mahler’s Parsifal allusions emerges in the opening Adagio of the Tenth Symphony. Although commonly examined from the perspectives of sketch studies, the Tenth Symphony is rarely the focus of discussions of allusion in Mahler’s works. However, the work provides fertile ground for an exploration of musical allusions in Mahler’s works, particularly in the case of the turn figure, which appears in the first, third, and final movements of the symphony. In the first movement, the figure appears for the first and only time in m. 55 in the first violins in sixteenth notes and is followed by a descending four-note eighth-note phrase that follows the intervallic pattern of a major second, perfect fourth, and a minor third (Example 9).(21) This turn figure and its subsequent four-note figure function as an allusion to Wagner’s Parsifal, but not to the Heilandsklage motive. Instead, it indicates a reference to the extended Waldesrauschen motive, which appears for the first time in Act I, scene i of the drama (Example 10).

[2.13] Although often extended later in the work, the Waldesrauschen motive comprises two basic parts: the turn figure (x) and the “Nature melody” (y), a four-note descending melody following the pattern of major second, perfect fourth, and minor third. In the drama, this motive appears repeatedly across the orchestra between mm. 269 and 279 and accompanies Amfortas’ text, ‘‘Nach wilder Schmerzensnacht nun Waldes Morgenpracht, Im heil’gen See wohl labt mich auch die Welle.” [“After a night filled with pain comes the forest’s glorious morning! In the holy lake may the waters refresh me” ]. In this motive, the turn itself is extracted from the turn of the Heilandsklage motive and draws upon its connotations of religious suffering. This is then combined with the “Nature” melody, indicating Nature’s ability to heal the pain of Amfortas (which throughout the drama functions as a symbol for the suffering of Christ). By combining these two themes, Wagner creates a form of motivic tone painting that expresses the healing properties of nature. Given the similarity between Mahler’s figure and Wagner’s motive, it is likely that Mahler is directly alluding (consciously or subconsciously) to the “Nature’s Healing” motive in his Adagio. Yet, despite the parallels between these two motives, it acts as an allusion rather than a quotation due to two primary differences: the rhythmic weighting of both the turn and the subsequent four-note figure, and the interval between the final note of the turn and the first note of the descending figure (a minor third in Mahler’s case, in contrast to Parsifal’s perfect fifth). Despite these differences, there is certainly enough resemblance to claim that it functions as an allusion to Wagner’s drama, and similarly, to consider whether the transference of meaning from Amfortas’s text applies to this passage of the Tenth Symphony. If this is the case, Mahler’s Adagio can be read as drawing upon the healing power of nature as thematized in Parsifal while simultaneously hinting at the overall intention or meaning of the movement and what role these Parsifalian themes may have within it.

Example 11. Mahler, Tenth Symphony, Finale, mm. 352–57

(click to enlarge)

Example 12. Mahler, Tenth Symphony, Finale, mm. 225–38

(click to enlarge)

[2.14] References to the Heilandsklage theme also emerge in the Adagio finale, albeit slightly more covertly. These figures and their possible Wagnerian roots have been observed by Constantin Floros, who argues that mm. 352–56 of the Tenth’s finale (Example 11) offers a compelling parallel to the Verklärungsfigur of Wagner’s Tristan (2012, 178). However, upon closer inspection, it is more likely that these turns function as a reference to the Heilandsklage figure instead due to the appearance of an accented descending scale two measures later (labeled “y” in Example 11). This same pattern of a quintuplet turn followed by a descending scale also takes place at m. 234 (Example 12), with the scale featuring two measures later in the flutes and violins. In this case, the final note of the phrase following the turn in m. 234 (

[2.15] Undoubtedly, there are far more turn motives to be discussed in Mahler’s works than have been mentioned here. However, this summary did not intend to examine every Mahlerian turn, but rather shine a light on the select few that carry the most weight and significance for showcasing the intertextual, and distinctly Wagnerian, roots of Mahler’s turns. Mahler’s role as a prolific Wagnerian conductor and dedicated Wagnerian undoubtedly influenced the construction of his own compositional and motivic vocabulary, as he commonly alludes to passages from Wagner’s dramas in various contexts across his oeuvre. The appearance of the Heilandsklage motive in his works is of particular significance, not only due to the frequency of its appearance, but because of its aesthetic themes of religious suffering, pain, and redemption which are pertinent to our interpretive understanding of the finale of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony.

3. The Ninth Symphony: Adagio, Finale

[3.1] Although turn figures appear across all four movements of the symphony, they appear most prominently in the Adagio finale. In each movement, the turn establishes a rather different musical identity. In the first movement, Andante comodo, the turn does not appear with the same prevalence as in the finale, but it certainly still appears frequently enough to be considered a motivic idea in the movement. Here, the turn appears as a five-note quintuplet sixteenth note figure and is localized to the development section of the work, featuring in mm. 288–89, 304–5, and 308. In the second movement, the figure seems to appear principally in an ornamental capacity, appearing as a decorative melodic idea in the material of the B section; this is in keeping with the Ländler dance-style of the movement.(23) The figure’s revival in the third movement Rondo-Burleske is somewhat more significant, appearing notably at mm. 356, 366, 383–84, 447, and 457. Constantin Floros has theorized that the turn figures in this movement act as a model for the turn figures of the finale, claiming that the turn figures of the Adagio are a direct allusion to those of the Rondo-Burleske (2003, 294). However, I believe it is more likely that the appearance of the figure in the third movement acts as a narrative prolepsis, offering a foreshadowing of the music to come in the fourth movement. This perspective is reinforced by Kurt von Fischer, who has argued that, although appearing prominently in the third movement, the figure’s status as a motive is only realized once the turn is employed in the finale, where it plays a central role in the symphony’s motivic vocabulary (1975, 102). It is clear that a wider investigation of the turn’s appearance across all four movements would be necessary to establish its meaning within the Ninth Symphony. However, it is the goal of this research to examine the figure in the finale, its most meaningful and important context in the symphony. Taking the three appearances of Wagner’s motive as anchors, this analysis is divided into three sections: the Opening Recitative and Chorale, the Prepared Climax and A section Reprise, and the Finale Coda.

Opening recitative and chorale

Example 13. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 1–4

(click to enlarge)

[3.2] From the very early stages of the movement’s conception, Mahler intended the turn to be an integral figure in the opening chorale. In the 1909–10 sketches of the movement the turn is drafted into the main body of the chorale passages, implying that the figure held significance as an important motivic component rather than a melodic embellishment added at a later date.(24) The first statement of the turn appears in the first measure of the opening two-measure recitative (Example 13), before going on to feature as a fundamental figure in the opening A section chorale (mm. 3–10). In this opening recitative, the unison violins play a thirty-second note turn that is followed by a descending scale leading into the chorale. The importance of this opening phrase is demonstrated by the exposed unison first and second violins and the accents that appear on each of the notes of the turn figure, which are reinforced by strong f dynamics.

Example 14. Wagner’s Parsifal, Act I Prelude, mm. 99–100: first appearance of the Heilandsklage motive

(click to enlarge)

[3.3] The parallels between Mahler’s opening and Wagner’s Heilandsklage motive are immediately apparent. In both cases a thirty-second note turn figure is followed by the interval of a minor third and a four-note descending scale (compare with Example 14). Had there not been a one-note deviation in the descending scale, it would be possible to label Mahler’s opening a direct quotation to Wagner’s motive rather than simply an allusion. Including this initial appearance, Mahler chooses to employ this Heilandsklage motive at three of the most central moments of the movement: in the opening recitative (mm. 1–2), the return to the A section following the climax of the movement (mm. 121–25), and the final transition to the coda (mm. 157–58).

[3.4] In Parsifal, the motive appears for the first time at the end of the Act I Prelude (mm. 99–100, p. 26(25)), and the presence of the turn in the Prelude affirms its status as an integral cog in the construction of Parsifal’s leitmotivic lexicon. Ulrike Kienzle asserts that the lamenting turn figure is one of the central aspects of the motive and claims that “in the context of the sparse ornamentation of the Parsifal score, this [turn] figure is anything but a playful decoration, and represents a poignant and meaningful expression” (Kienzle 2005, 117). As well as being used to reflect the suffering of Christ and Amfortas, the Heilandsklage motive is also adapted into narrative contexts associated with Kundry and her connection to the Savior, most notably in her revelation to Parsifal of her religious sin as she saw Christ suffering on the cross and laughed.(26) Kurt Overhoff has theorized that the Heilandsklage motive and its “mordent” (as he terms it) specifically represents the look Christ gave to Kundry as she mocked Him on the cross, providing an direct association between the motive, the turn figure, and the suffering of Christ (Overhoff 1951). In this way, Wagner clearly establishes the turn figure as an important tool for signifying the Christ’s suffering, pain, and lament.

Example 15. Wagner, Parsifal, Act I, Prelude, mm. 99–100

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] As well as being melodically similar, both Mahler’s and Wagner’s Heilandsklage motives maintain wider harmonic parallels and use harmonic and melodic dissonance or conflict to generate extra-musical associations of tension or uncertainty. In Parsifal, tension is not only created by the inherent cycle of dissonance and resolution created by the turn figure but is also central to the motive in its entirety (Example 15). The moment directly following the turn figure is one of great tension, created by the

Example 16. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 1–5: opening recitative from first perspective, Am / E major continuing from Rondo-Burleske

(click to enlarge)

Example 17. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 1–5: opening recitative as precursor to

(click to enlarge)

[3.6] In contrast to the Heilandsklage motive, Mahler’s opening turn motive is unharmonized and therefore requires a degree of interpretation. One of the most thought-provoking features of the opening turn and its subsequent scale is that it functions similarly to a harmonic “optical illusion,” as it presents a different reading depending on which direction you look at it. The first of these perspectives (Example 16) is to examine the recitative as following from the harmonic conclusion of the third movement Rondo-Burleske, while the second perspective is to examine the recitative retrospectively from the harmonic standpoint of the A section chorale (Example 17).

[3.7] In the first instance (Example 16), the recitative acts as a harmonic continuation of the previous movement, which concluded in A minor, the home key of the movement. In this case, the opening

[3.8] An alternative interpretation is to view the recitative as a precursor to the

[3.9] No matter which perspective you choose to adopt, both readings offer parallels to the Heilandsklage motive of Wagner’s Prelude. If one considers Mahler’s opening recitative in A minor / E major, the descending scale can be harmonized similarly to Wagner’s figure, using a IV–V–I pattern intending to land on the tonic in the third measure (a cadence that is prematurely halted by the appearance of

Example 18. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, m. 6: “turn within a turn”

(click to enlarge)

[3.10] Following its appearance in the opening recitative, the turn figure saturates the musical fabric of the passage (mm. 3–10). It is transported out of its Heilandsklage motivic context and instead featured in isolation, carrying the essence of the motive into the main body of the chorale. The A section resembles that of a Bach chorale, albeit not harmonically. The turn not only functions as a melodic addition to the line, but also generates motion through an endless cycle of dissonance and resolution against the surrounding harmony. A fusion of two appoggiaturas, the figure naturally transitions to the next chord, seeking out melodic and harmonic closure. However, the deeply embedded network of turn figures in this chorale can, at times, obscure where the tension lies or is created within the surrounding harmony, furthering the notion of ambiguity and heightened chromatic tension. For example, at m. 6 the creation of dissonance against the chord changes depending on how you choose to analyze it (Example 18). In addition to the eighth-note turn in the first violins, the cellos and basses play a “turn within a turn” beginning when the first turn meets its lower auxiliary. If one looks at the turn in the cello and basses within the surrounding

Example 19. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 1–15: chorale and brief two-measure B section

(click to enlarge)

[3.11] Wider notions of “turning” can also be found in the underlying harmonic scheme; see Example 19. The A section’s chorale can be divided into two four-measure phrases in an antecedent–consequent relationship (mm. 3–6 and 7–10). In the first five beats of the consequent phrase, the chorale typically follows a progression

[3.12] From a study of just the first ten measures of this movement it is possible to see the impact that the turn figure has on the overall construction of the work. The Heilandsklage’s revival at the opening of Mahler’s movement leads to an interpretation that the movement begins with a cry of religious suffering and pain emblematic of that experienced by Amfortas (and indicative of Christ) in Parsifal. Just as Wagner extracts the turn from its initial motive and repurposes it in a series of different motives in Parsifal, Mahler extracts the turn from its opening recitative and embeds it into the motivic fabric of the work, carrying the associated meanings of the turn throughout the remainder of the work. The result is not simply a musical allusion, but an obsessive manifestation of (Wagnerian) suffering.

Prepared climax and A section reprise

Example 20. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 99–105: fluctuating thirds in harp and bassoons

(click to enlarge)

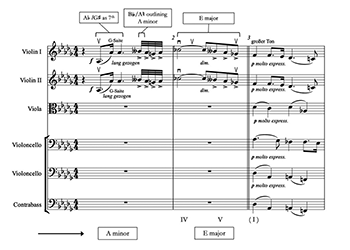

[3.13] The Heilandsklage motive is revived again at mm. 121–26, taking on a central role in the work’s climax. Although it is the turn figure that functions as the focus of this analysis, broader consideration of other Wagnerian allusions in this section of the movement can help substantiate a relationship between Mahler’s “Heilandsklage motive” and Wagner’s drama. Following a turn to

Example 21. Mahler, “Der Abschied,” Das Lied von der Erde, mm. 84–90

(click to enlarge)

Example 22. Wagner, Parsifal, Act III, mm. 623–31: fluctuating triplet figure in the lower strings and Heilandsklage motive in the first violins

(click to enlarge)

[3.14] In “Der Abschied,” these fluctuating triplet minor thirds and fourths are employed throughout the work’s B sections. At rehearsal number 7, they begin in the

[3.15] Wagner’s decision to recreate the “forest murmurs” and their associations with nature’s tranquility at this moment certainly seems more than coincidental as, directly following Kundry’s baptism, Parsifal becomes mesmerized by the beauty of the forest and learns that it is Good Friday. Wagner’s motivic tone painting is both subtle and significant, as he combines the musical suffering of Christ through the Heilandsklage motive with a former theme for the forest’s innate, fairy-tale-like magic. In both contexts, the forest murmurs theme leads to the protagonist’s enlightenment through the deepening of knowledge or understanding. For Siegfried, this manifests in his understanding of the wood bird’s song, while for Parsifal it is his knowledge of Good Friday. This association becomes important in the context of “Der Abschied,” as rather than drawing solely on the magic of Siegfried’s forest, the Parsifal variant resonates with a profoundly religious undercurrent that reframes the intended depictions of nature in Mahler’s work. It is not simply a representation of nature’s tranquility that Mahler intends to capture, but one that is tangled up in a web of Wagnerian, and distinctly Parsifalian, suffering.

[3.16] Therefore, although the passage of alternating thirds and fourths of the Ninth Symphony could easily be attributed to Wagner’s Siegfried (and a recollection of the former “Der Abschied”), consideration of the turn figure invites a different interpretation. As in Parsifal, the fluctuating thirds of the Ninth are preceded by two turn figures in the

[3.17] This relationship between the fluctuating-thirds theme and the Heilandsklage figure can also be further substantiated by a brief examination of mm. 225–28 of thefinale of the Tenth Symphony (Example 12). In this excerpt, a triplet fluctuating theme is replicated in the harp, but here it offers alternating triplet fourths and fifths rather than thirds (and fourths) as in Siegfried, Parsifal, the Ninth, and “Der Abschied.” Although the intervals of the passage are more varied than those of its predecessors, the Tenth Symphony’s fluctuating triplets still seem much connected to these previous versions due to the appearance of the turn figure. Here, the quintuplet turn figure appears just six measures after the conclusion of the triplet passage, providing a close resemblance to “Der Abschied,” the Ninth Symphony, and Parsifal, creating a thought-provoking network of quintuplet turns and fluctuating-third figures across the late works of these composers. This series of observations marks just the beginning of what would undoubtedly be an important investigation into the motivic and contextual parallels between these four works (or five, if we are to include Siegfried’s “murmurs”), and for considering the implied meanings of interactions between various Wagnerian allusions in Mahler’s late works.

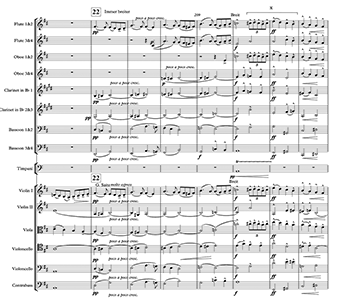

Example 23. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 117–27: end of climax and transition into A1 variation

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.18] Fifteen measures later (m. 121), Mahler calls for the Heilandsklage motive to be revived across the full orchestral texture, imbuing this climactic middle of Mahler’s movement with references to Kundry’s baptism, the enlightening “spell” of the forest, and the suffering of Christ on Good Friday. The lead-in to the work’s climax begins at m. 117 (Example 23), and the issue of harmonic and melodic instability presented in the opening is once again revived, recreating the sensation of “shifting sands” that was present in the chorale across the full orchestral texture. The quintuplet turn at m. 117, in all iterations, ends on a

[3.19] By recreating the opening of the movement in this passage, Mahler allows familiar material to take on an unfamiliar expression. The Heilandsklage motive of the opening recitative has progressed from its original lamenting character to form a desperate and intense variation in mm. 121–24, functioning as the moment of greatest tension and anticipation in the movement’s climax. In this middle section, the turn is not only integral to building tension for the lead-in to the climax and a fundamental part of the climactic musical material itself, but it also takes on a new, deeply expressive role with an alternative rhythmic character, and the associations of Parsifal’s religious suffering call out with greater resonance and desperation.

Finale, Coda

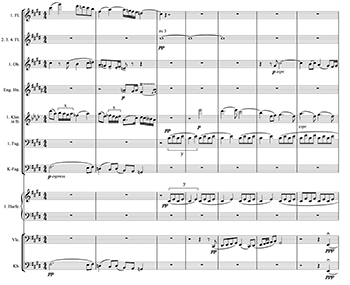

Example 24. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 152–58: turn leading into the coda

(click to enlarge)

[3.20] As the work draws to a close several transformations occur. The forward motion that was once so important to the movement, driven by the turn motive and its underlying harmony, is replaced with musical disintegration and an increasing temporal slowness, giving the impression of a work afraid of ending (Spears 2007). From mm. 120–26 on, there are various moments where the music is infiltrated by passages of extended empty time and space, permeating every aspect of composition—melodically, harmonically, rhythmically, and temporally. At m. 137, Mahler includes a one-measure time signature change to

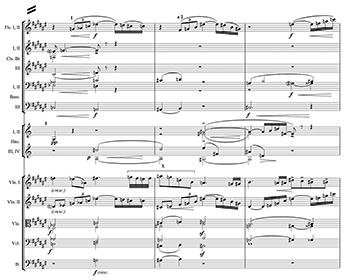

Example 25. Mahler, Ninth Symphony, Finale, mm. 159–85

(click to enlarge)

[3.21] As the coda unfolds with its sparse melodic lines, it demonstrates wider notions of musical dissolution, as the motivic material of the work is stripped down and accompanied by static, simple harmonic progressions and extended moments of full symphonic silence (Example 25). Adorno has previously claimed that “Mahler does not—as Beethoven does—shun lengthened measures or moments in which . . . nothing happens, but where the music becomes a state” (1996, 68); and here in the coda there is certainly no fear of lengthened measures or strung-out silences. While the overall sensation of dissolution in this passage is indebted to the lengthy measures of extended “nothingness” and the harmonic stasis of the passage, one of the most important factors for the conclusion of the work is the turn figure. In these final twelve measures, the only feature keeping the music “alive” and progressing forward is the momentum generated from the turn. Here the figure succumbs to the spent energy of the music that surrounds it——becoming rhythmically abstracted and lethargic——while still creating a feeling of propulsion, pushing the coda onwards amid passages of suspended silence and static harmony. At m. 163, the viola gives the first full statement of the turn in quarter-note movement appearing over an apparent

[3.22] When the full texture begins again in m. 172, the IV chord is reiterated before finally completing the plagal cadence on the third beat of the following measure. Two devices in particular are used to help create this final cadential resolution. The first is the turn figure, which provides a brief moment of forward movement through the creation and resolution of dissonance amid the static chords and suspended violin notes, driving the music over the edge of the measure to cadence. The second is the

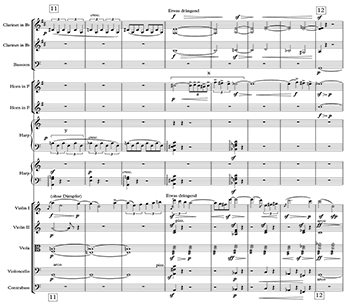

[3.23] Yet it is the final turn (mm. 184–185) that offers the most distinctive and thought-provoking variation. It subverts all expectations by no longer conforming to the rhythmic or melodic form that has made up the turn’s identity throughout the movement. Marked “ersterbend,”(33) Mahler’s inverted turn is written in marcato triplet half note movement after a time signature change to

[3.24] It is through the turn that the movement is brought to life and through the same turn that it reaches its end; as Micznik claims, “in the context of the saturation of the movement with the turn motive, its final usage appears as a crowning touch: it is basically through the disintegration of this motive that the Finale ends” (1989, 432). Although a few studies have acknowledged the inverted turn and its importance at the end of this movement, there has been very little consensus regarding the possible meanings of the figure at this moment. Nixon and Fischer believe that the inverted turn sets the scene for the work to begin again, reading a renewing and cyclical interpretation from these last two measures (Nixon 2008; Fischer 1975). This perspective is similarly adopted by Newcomb, who writes:

The motivic fragments that float through the thin ether of the last page of the score are drawn from the upbeat to the large-scale contrast of the movement (compare m. 159, violin II, p. 182 and m.28, cello, p.167) and from the third, slightly contrasting phrase of the main tune itself (compare mm. 160–61 and mm. 13–14, p. 166). They are drawn, that is, from the bits of musical material that had themselves offered the points of departure and contrast in the movement, and then the stimuli to return and rebegin. (1992, 136)

Samuels has also commented on the reworking of fragments of the primary material from the movement in this finale and remarks that, “while Mahler’s Ninth Symphony is a finished work in the ordinary sense . . . the unfinished quality of the gestures in its final pages betray an anxiety concerning the validity of the novelistic symphonic narrative whose nineteenth-century history Mahler did so much to extend” (2011, 254). Most notably, he comments on the “unfinishability” of both Proust’s and Musil’s novels, a quality that he believes resonates in Mahler’s finale and is exemplified by the ambiguity created in the final inverted turn figure. This, in turn, poses questions about the creation of closure in this coda, and whether harmonic closure is ever achieved. In Fischer and Nixon’s interpretation, the possibility that the movement is set to rebegin challenges any opportunity for closure. Micznik has theorized that this turn’s final landing on

4. Conclusion

[4.1] This article began with a quote from Hans Ries claiming that the turn figure is of unprecedented importance but that the meaning of the figure and its expressive associations were still very much open to interpretation. This analysis attempted to answer the question left open and unanswered by Hans Ries: what exactly is this turn trying to say? Whether there is a definitive answer to this question remains unclear, but this investigation endeavored to provide a reading of the turn that demonstrates its importance, value, and substance as a motivic figure in Mahler’s movement. Here, I demonstrated that no figure is too small to be investigated, and that the figure should not be ignored when undertaking analytical readings or investigations into the work. The Ninth Symphony has proven to be a privileged space for the exploration of narrative in Mahler’s works and continues to be of interest to scholars looking to evaluate extra-musical meaning in symphonic works; an evaluation of the turn figure in the context of musical narrative would no doubt result in some interesting and thought-provoking discussions and analyses. While the turn figure has been shown to appear across Mahler’s oeuvre, it is in this work that it embodies a compulsive quality that affects the fundamental construction of the movement and provides a valuable space for exploring the legacy of Wagner’s Parsifal, specifically through the reappearance of the Heilandsklage motif. If, as this article proposes, Mahler is alluding to the associated meanings of Wagner’s Heilandsklage turn motif at the pivotal moments of the finale of the Ninth Symphony, this offers an entirely new perspective on the overall meaning of Mahler’s so-called “farewell to life” movement; one which (through the associations of the Heilandsklage) can be read as being imbued with decidedly Parsifalian references of religious suffering. Looking forward, it is my hope that this study plants the seed for further conversation and investigation of Mahler’s Wagnerian allusions and the need for establishing innovative interpretations of not only the musical works in their entirety, but of the small musical figures that can transform our understanding of them.

Genevieve Robyn Arkle

University of Bristol

Victoria Rooms

88 Queens Road

BS8 1SA, United Kingdom

g.arkle@bristol.ac.uk

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor. 1996. Mahler: A Musical Physiognomy. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. The University of Chicago Press.

Arkle, Genevieve. 2021. “Investigating the Turn Figure as Allusion and Topic in Wagner’s Parsifal and Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. PhD diss., University of Surrey.

—————. 2023. “Expressions of Suffering: The Five ‘Turn Motifs’ of Wagner’s Parsifal.” The Wagner Journal 17 (1): 22–44.

Bach, C.P.E. 1753. Versuch über die wahre Art, das Clavier zu spielen. Part I. 1st ed. Christian Friedrich Henning.

Baragwanath, Nicholas. 2004. “Fin-de-siècle Wagner: Parsifal Analyzed through Berg's Programme to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony.” Music Analysis 23 (1): 27–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0262-5245.2004.00194.x.

Dannreuther, Edward. 1893. Musical Ornamentation. Part I. Novello, Ewer and Co.

La Grange, Henry-Louis de. 1974. Mahler: A Biography. Vol 1. Victor Gollancz.

—————. 2008. Gustav Mahler. Vol. 4, A New Life Cut Short (1907–1911). Oxford University Press.

Donnington, Robert. 1963. The Interpretation of Early Music. Faber.

Fischer, Kurt von. 1975. “Die Doppelschlagfigur in den zwei letzen Sätzen von Gustav Mahlers 9. Symphonie. Versuch einer Interpretation.” Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 32 (H.2): 99–105. Franz Steiner Verlag. https://doi.org/10.2307/930403.

Floros, Constantin. 2003. Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies. Amadeus Press.

—————. 2012. Gustav Mahler. Visionary and Despot: Portrait of A Personality. Translated by Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-01735-9.

Greene, David. 1984. Gustav Mahler: Consciousness and Temporality. Gordon and Breach.

Hefling, Stephen, ed. 1997. Mahler Studies. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 1999. “The Ninth Symphony” in The Mahler Companion, eds. Donald Mitchell and Andrew Nicholson. Oxford University Press.

Johnson, Julian. 2009. Mahler’s Voices: Expression and Irony in the Songs and Symphonies. Oxford University Press.

Kienzle, Ulrike. 2005. “Parsifal and religion: a Christian music-drama?” in A Companion to Wagner’s Parsifal, eds. William Kinderman and Katherine Rae Syer. Camden House.

Mahler, Alma. 1946. Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters. John Murray.

Mahler, Gustav. 1979. Selected Letters of Gustav Mahler. Edited by Alma Mahler. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

—————. 1986. Mahler’s Unknown Letters. Edited by Herta Blaukopf. Translated by Richard Stokes. Gollancz.

—————. 1994. Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss: Correspondence 1888–1911. Edited by Herta Blaukopf. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. The University of Chicago Press.

—————. 1996. Gustav Mahler Briefe. Edited by Herta Blaukopf. Paul Zolansky Verlag.

—————. 2003. Gustav Mahler: Briefe Und Musikautographen Aus Den Moldenhauer-Archiven in Der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek Berlin: Kulturstiftung der Länder.

—————. 2006. Liebste Justi:’ Briefe an die Familie. Edited by Stephen McClatchie. Redaction by Helmut Brenner. Weidle.

—————. 2009. The Mahler Family Letters. Edited and translated by Stephen McClatchie. Oxford University Press.

Matthews, David. 1995. “Mahler and ‘Parsifal.” Muziek & Wetenschap 5 (3): 385–404.

—————. 1999. “Wagner, Lipiner, and the ‘Purgatorio.’” In The Mahler Companion, ed. Donald Mitchell and Andrew Nicholson, 508–16. Oxford University Press.

McGrath, William. 1974. Dionysian Art and Populist Politics in Austria. Yale University Press.

Micznik, Vera. 1989. “Meaning in Gustav Mahler’s Music: A Historical and Analytical Study Focusing on the Ninth Symphony.” PhD diss., State University of New York at Stony Brook.

—————. 2020. “Intertextuality in Mahler.” In Mahler in Context, ed. Charles Youmans. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108529365.018.

Mitchell, Donald, and Andrew Nicholson, ed. 1999. The Mahler Companion. Oxford University Press.

Neumann, Frederick. 1978. Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music. Princeton University Press.

—————. (1988). “Interpretation Problems of Ornament Symbols and Two Recent Case Histories: Hans Klotz on Bach, Faye Ferguson on Mozart.” Performance Practice Review 1 (1): 71–106. https://doi.org/10.5642/perfpr.(1988)01.01.7.

—————. 1993. Performance Practice of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Schirmer Books.

Newcomb, Anthony. 1992. “Narrative Archetypes and Mahler’s Ninth Symphony.” In Music and Text: Critical Enquiries, ed. Steven Paul Scher, 118–36. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511518355.008.

Nixon, Mark. 2008. “The Construction of Closure and Cadence in Gustav Mahler’s Ninth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde.” PhD thesis, The Open University.

Overhoff, Kurt. 1951. Richard Wagner’s Parsifal. F. Perneder.

Peattie, Thomas. 2015. Gustav Mahler’s Symphonic Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139225243.

Reynolds, Christopher Alan. 2003. Motifs for Allusion: Context and Content in Nineteenth-century Music. Harvard University Press.

Ries, Hans. 1989. “Das Grupetto als symbolische Figur in Mahlers IX. Symphonie: Ein hermeneutischer Essay.” In Musik in Bayern. Halbjahresschrift der Gesellschaft für Bayrische Musikgeschichte e.V., Heft 39. Hans Schneider.

Russell, Louis Arthur. 1894. The Embellishments of Music. Theodore Presser.

Samuels, Robert. 2011. “Narrative Form and Mahler’s Musical Thinking.” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 8 (2): 237–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479409811000279.

Spears, Gregory. 2007. “The Final Page of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony.” PhD diss., Princeton University.

Stoll Knecht, Anna. 2017. “Mahler’s Parsifal.” The Wagner Journal 11 (3): 4–26.

Wolzogen, Hans von. 1890. Thematischer Leitfaden durch die Musik zu Richard Wagner’s ‘Parsifal’ nebst einem Vorworte über den Sagenstoff des Wagner'schen Dramas. Feodor Reinboth.

Footnotes

* My warmest thanks are extended to Jeremy Barham, Sam Reenan, and the members of the University of Bristol Writing Group for providing such detailed and thoughtful feedback during the editing process of this article.

Return to text

1. The translations from German texts used throughout are my own.

Return to text

2. For a table itemizing all the turn figures in the finale of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, see Arkle 2021, Appendix 3.

Return to text

3. “Savior’s Lament”, also sometimes simply referred to as “Agony”.

Return to text

4. “The turn figure propels the solo voice upwards in order to descend again to the return of the melody and accompaniment texture. It is found in countless vocal and instrumental compositions marking the end of a cadenza or simple extension of the solo voice prior to the repeat of the main melodic material . . . it underlines its essentially vocal, even aria-like character” (Johnson 2009, 278).

Return to text

5. For more information on Mahler’s Wagnerian allusions, see Baragwanath 2004, Floros 2012, Stoll Knecht 2017, Matthews 1995, Matthews 1999.

Return to text

6. 4 March 1894 to Justine. In this letter Mahler tells Justine how he has received yet another friendly letter from the Wagner family, so many in fact that he felt he had received a letter from all significant members of the family except for Wagner himself: “you have gotten the entire family together, except for him [Wagner], who, fortunately, also belongs a little bit to my family” (2006, 373).

Return to text

7. After seeing it, Mahler wrote to his friend Friedrich Löhr, “I can scarcely describe to you my present feelings. When I, incapable of speech, stepped out of the Festspielhaus, I knew that I had come to understand all that is greatest and most painful, and that I would bear it inviolate within me for the rest of my life” (1986, 200).

Return to text

8. Birrenkoven was the first of many singers Mahler trained in the city, the most famous of which being Anna von Mildenburg who Mahler had already an established a relationship with from their time together at the Opera in Hamburg. As soon as the tenor arrived in Bayreuth, Cosima wrote to Mahler thanking and congratulating him on his preparation of the singer, writing “no singer has ever arrived so perfectly prepared” (La Grange 1974, 888).

Return to text

9. Cosima warmed to the young conductor over time, resulting in her writing to Levi “[I] have nothing but praise for his character and method” (Mahler 1986, 199).

Return to text

10. The program comprised extracts from Götterdämmerung (conducted by Ludwig Slansky) alongside Mahler’s conducting of the Parsifal extracts, paired with a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in the second half, conducted by Karl Muck (La Grange 1974, 140).

Return to text

11. These performance took place despite Mahler’s agreement that he would not perform the work outside of Bayreuth. In her memoirs of Autumn 1907, Mahler’s wife Alma recalls how he inserted a clause into his contract with Conried for New York declaring that he would not, under any circumstances, conduct Parsifal, as he would not go against the statement in Wagner’s will that demanded Parsifal stay in Bayreuth (Mahler 1946, 125).

Return to text

12. See, for example, Bach 1753, 85–95, Dannreuther 1893, Donnington 1963, Neumann 1978, Neumann 1993, Russell 1894.

Return to text

13. For further arguments on how the turn figure could function as a musical topic, see Arkle 2021, 44–84.

Return to text

14. The turn symbol was still used in the nineteenth century, and there are many cases in which a composer who typically favors written-out turns might still use symbols alongside or in other works. However, broadly speaking there appears to be a trend for moving away from the turn symbol and integrating the figure into the work through full notation.

Return to text

15. “L’homme est né libre, et partout il est dans les fers.”

Return to text

16. Composers such as Grieg, Liszt, Chopin, Bruckner, and Schoenberg all provide ample examples of these more integrated and expressive turn figures. For more information on the turn in the nineteenth century, see Arkle 2021, 58–67.

Return to text

17. The figure appears most prominently as a recurring figure in Rienzi’s “prayer” aria in Act V.

Return to text

18. Labels for the motives are given by Wolzogen (1890).

Return to text

19. These turn figures and their similarity to Wagner’s Parsifal were first acknowledged by James Hepokoski in a workshop at the KeeleMAC 2015 Summer School.

Return to text

20. “To recapture in sleep, Forgotten happiness and youth.”

Return to text

21. All excerpts in this section are taken from Deryck Cooke’s performing version of the Tenth Symphony, published in 1989 by Faber Music Ltd.

Return to text

22. “To live for you, to die for you, Almschi!”

Return to text

23. Mahler uses the turn similarly in the second movement of his Second Symphony, which is also a Ländler.

Return to text

24. Score sketch analysis taken from Gustav Mahler: Briefe und Musikautographen aus den Moldenhauer-Archiven in der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Kulturstiftung der Ländler, 2003).

Return to text

25. As most scores for Parsifal do not contain measure numbers, I have provided page numbers to help readers locate the example in the work. Pages correspond to the 1986 Dover Edition which is available online through IMSLP and via the following link: https://ks4.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/c/cb/IMSLP515555-PMLP5713-Wagner_-_Parsifal.pdf.

Return to text

26. See Act II, mm. 1186 and 1197 (p. 397) following her text “Ich sah Ihn, Ihn, und lachte, da traf mich sein Blick!”

Return to text

27. Stephen Hefling has supported this perspective by commenting that this opening passage with “‘its focus on

Return to text

28. As termed by Donnington 1963, 210–11.

Return to text

29. This open-ended perspective is also adopted by Vera Micznik in her analytical study of the finale (1989, 408).

Return to text

30. See Wagner’s Siegfried, Act II, following Mime’s text “Fafner und Siegfried, Siegfried und Fafner: oh! brächten beide sich um!”

Return to text

31. “Receive baptism and believe in the Redeemer!”

Return to text

32. David Greene has theorized that in this coda the conflict created between the A and B sections of the movement has dissipated, and that the B section (which he terms “fanfare”) “is absorbed into the hymn.” Greene’s reading offers an interpretation of structural closure being achieved at the end of the movement, as the turning and alternating motion of the movement can only be halted by one engulfing the other (1984, 281).

Return to text

33. “dying away”

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Lauren Irschick, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

6013