Prosodic Dissonance*

Eron Smith

KEYWORDS: prosody, accent, stress, text setting, enjambment, Kesha, Royal & the Serpent, Rina Sawayama

ABSTRACT: In popular and scholarly discourse on texted music and music-speech intersections, the prevailing assumption is that the linguistic features of the lyrics (e.g., syllabic stress) align with the way the lyrics are sung (e.g., phenomenal accent in or affecting the melody)—or, if not, that they should. However, not only can text and music conflict, but they do so in a variety of ways, to varying degrees, and with different effects on our listening experience. I define prosodic dissonance as any conflict between the prosodic linguistic features and musical rendition of text. This could include misalignment between syllabic and durational/registral stress, between spoken and sung phrases, or between spoken and sung intonation. Prosodic dissonance/consonance can also interact with rhyme, vowel shape, parallelism, and syncopation. To recognize prosodic dissonance, I (1) determine the prosody for the lyrics as spoken, (2) determine the prosody for the melody as sung, (3) identify mismatches as dissonances, (4) consider the effect of the surrounding melody/lyrics, (5) consider alternate pronunciations or hearings that might account for it, and (6) consider the perceptual and analytical implications. This article focuses on prosodic dissonance in popular music, with longer analyses of Kesha’s “Tonight” (2020), Royal & the Serpent’s “Overwhelmed” (2020), and Rina Sawayama’s “This Hell” (2022).

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.2.6

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

Unconditionally Rejected

Audio Example 1. Katy Perry, “Unconditionally,” chorus (0:34)

[1.1] Katy Perry released her 2013 single “Unconditionally” to mixed reviews.(1) Some critics focused on cultural appropriation in live performances (e.g., Feeney 2013), some connected the song’s sound to their Christian beliefs and the artist’s Christian music roots (e.g., Lynch 2016), and others noted its “self-help-y lyrics” (Brown 2013). In reviews and across the internet more broadly, however, one particular feature of the song has received consistent—and consistently negative—attention: the singer’s apparent delivery of the title as “uncondiTIONal.” Professional and amateur critics across the internet noted Katy Perry’s rendition of “unconditional,” extracted in Audio Example 1, as weird, ridiculous, laughable, and wrong. For some listeners, this setting went so far as to “ruin” the song entirely.(2) Despite songwriting credits from four experienced songwriters (Katy Perry, Dr. Luke, Max Martin, and Cirkut), the song’s reception framed the chorus as containing a “mistake.”

[1.2] While negative value judgments are common in internet responses to pop music releases, the singular focus on the title word reveals an attached set of music-theoretical takeaways. When reviewers and writers criticize “emphasis on the wrong syllable” in song rather than in speech (also referred to as “bad text setting”), the logical progression of this argument is that

the text has a stress pattern of its own,

the musical setting has a stress pattern of its own,

these two stress patterns are incongruous, and

this incongruity produces the aural impression of mispronunciation of the text.

[1.3] The consistent responses of amateur and professional critics alike point to the important interactions between music and the musical qualities of language itself. This article investigates this interaction, focusing on the dissonance and consonance between musical and linguistic prosody. Before combining the two, let us establish some of the prevailing understandings of prosody, accent, and text-setting as they relate to speech and music—matters explored at length in music theory, cognitive science, and linguistics.(3)

Defining and Perceiving Stress and Its Role in English

Stress has always seemed to resist all attempts at definition: the closer one investigates the nature of stress, the more difficult it becomes to define. One of the reasons for this is that a stressed (or prominent) syllable is distinguished not only by acoustic features, but it is also a perceptual phenomenon, i.e., in defining it, one must account not just for its production, but also for its perception by the interlocutor. (Frost 2011, 68)

[1.4] While music theorists tend to discuss rhythm in conjunction with meter and accent, linguists often frame speech rhythm in terms of stress.(4) Spoken English differentiates between stressed and unstressed syllables, tending to use more pitch movement, more distinct vowel qualities, and longer durations for stressed syllables. Historically, English has been categorized as a “stress-timed” language, tending to evenly distribute stressed syllables in time regardless of the number of syllables between them (as opposed to “syllable-timed” languages such as Spanish or French, which more evenly distribute syllables regardless of stress).(5)

[1.5] Though the stress-timed/syllable-timed dichotomy is widespread, some scholars have disputed it, proposing alternative ways of describing languages’ stress patterns. Bertinetto (1989) provides a summary of this debate and offers “compressibility” as an improved means of distinguishing syllable stress distribution. Arvaniti (2009) argues that research on speech rhythm should be based on the same principles for all languages, proposing a focus on grouping and prominence. Cross-linguistic metric differences are not robust, and metric differences between different speakers and dialects of the same language can be substantial (Arvaniti 2012, Bertinetto 2021). Nevertheless, stress does seem to be a widely perceptible phenomenon, even in species other than humans (Hoeschele and Fitch 2016), and despite dwindling evidence in favor of clear stress-timed/syllable-timed language categories, it does seem to vary between languages. Although individual speakers of a language may use a wide variety of stress metrics, stress can still inform whether we hear speech as foreign (Patel 2010), and our native language can have both contextual and perceptual effects on how we hear stress, as in the “stress deafness” effect observed in native French speakers (Degrave 2019, Frost 2011).

[1.6] In short, stress is a language-specific phenomenon made up of multiple acoustic factors, which enables the distinction of homonyms and the segmentation of words and phrases, facilitating our understanding (Cutler 2008). Since stress is a particularly important aspect of understanding and speaking English, the acoustic factors mentioned above—pitch movement, vowel quality, and duration—would intuitively seem more influential in English-language music than they would be in languages without such an emphasis on stress.(6) This intuition, however, is dependent on the assumption that musical stress (particularly melodic stress) and linguistic stress have mutual influence.

Between Speech and Song

[1.7] Some of the evidence for permeability between musical and linguistic features in texted music comes from the categories of song and speech themselves. Song and speech—much like syllable- and stress-timed languages—are better described as a continuum than a dichotomy. The distinction between the two, as well as the categorization of speech and song as such, is culturally specific.(7) Even within the same culture, the same sounds may be perceived as sung, spoken, or some combination of both, based on pitch stability, duration, timbre, rhythmic regularity, repetition, and context. Diana Deutsch’s famous “sometimes behave so strangely” illusion (2019) illustrates this phenomenon, as does the social media trend of harmonizing unaltered speech with jazz transcriptions (Liberman 2021).

[1.8] Furthermore, some cultures do not distinguish between song and speech categories (Trehub, Becker, and Morley 2015), and even in cultures with such a distinction, some forms of expression occupy a gray area between them. Some art forms situated between song and speech originate thousands (e.g., religious chant and poetry) or hundreds of years ago (e.g., recitative). Others are more recent developments that combine song and speech, like the mutual merging of singing and rap (Komaniecki 2019; 2020), and the “orationality” of speech-like singing in emo and punk music (Chiu and Howie 2022), which can serve as generic and formal markers as well as means of emotional expression.

[1.9] Even when speech and song are clearly distinguished, each still affects the perception of the other. Various effects of musical ability and musical context on prosody have been documented, such as links between the effects of amusia and prosody perception (Hausen et al. 2013), rhythmic cues establishing expectations about speech prosody (Cason, Astésano, and Schön 2015), effects of musical familiarity on spoken delivery of lyrics (Albert 2021), and links between familiarity of musical excerpts and prosody (Palmer, Jungers, and Jusczyk 2001). Furthermore, musical training improves the perception of lexical stress, even for speakers of “stress-deaf” languages (Degrave 2019, Kolinsky et al. 2009). The link also holds in reverse: prosody may inform how we hear meter and syncopation, affect ease of performance (Reed, Maxwell, and Temperley 2019), or affect our ability to understand the words (Gordon, Magne, and Large 2011).(8)

Speech-song Interactions in Compositional and Analytical Practice

[1.10] In addition to studying the perception of language, music theorists and linguists have investigated the effects of language on compositional practice. Language and dialect have repeatedly been shown to correlate with text setting practices and poetic meters in both texted and untexted music. Some authors describe this correlation in terms of meter-accent alignment probabilities (Temperley and Temperley 2013), while others posit that nationality affects composers’ preference for certain poetic meters or rhythmic practices (Rothstein 2008, Vukovics and Shanahan 2020, Daniele and Patel 2013). Generally, even while examining to what degree linguistic stress aligns with meter, most of these studies assume that stressed syllables align with musical accent.(9)

[1.11] Though music and speech differ in communicative capacity and degree of periodicity, both “involve the systematic temporal, accentual, and phrasal patterning of sound”—i.e., rhythm—as well as syntactical structures that group into higher-level units (Patel 2010, 176). In both media, this patterning and grouping involves varying pitch and duration (Wennerstrom 2001, Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1983). Likely owing to the commonalities described above, some similar hierarchical analytical conceptions and visual representations of meter have been used for music, poetry, and speech. Among these are tree diagrams, poetic “feet,” and metrical grids, all capturing the potential for these modes of expression to suggest multiple layers of accent.(10) Examining more qualitative criteria, authors have shown that text painting and text setting are fruitful subjects for in-depth analysis of expression, genre, individual composers’ style, and narrative.(11)

[1.12] Throughout the vast and growing literature above on texted music and music-speech intersections, ranging from music theory and analysis to cognitive science and linguistics, the assumption is that the linguistic features of the lyrics (e.g., syllabic stress) either align with the way the lyrics are sung (e.g., phenomenal accent in or affecting the melody)—or that they should.(12) However, not only can text and music conflict, but they do so in a variety of ways, to varying degrees, and with different effects on our listening experience.(13) I define prosodic dissonance as any conflict between a text’s prosodic linguistic features and its musical rendition. This could include misalignment between syllabic and melodic stress, between spoken and sung phrases, or between spoken and sung intonation.(14) Note that melodic stress refers to phenomenal accent rather than metric accent, meaning that prosodic dissonance is a distinct phenomenon from syncopation. Whereas syncopation describes the relationship between the meter and a given musical stream (e.g., the melody), prosodic dissonance describes the relationship between the melody and the text. For example, in Example 1, the syllable “-tion-” is not syncopated, but it is dissonant. I will explore some intersections and differences between syncopation and prosodic dissonance further below.

[1.13] The remainder of this article comprises five parts. Part 1 presents the spectrum of prosodic dissonance to consonance in terms of pitch and timing. Part 2 delves into the language elements (prosody), exploring English linguistic features such as vowel reduction and rhyme as they interact with sung melody. Part 3 returns to the musical sphere, specifically parallelism, syncopation, and phrase breaks. Combining these elements, Part 4 presents three analytical vignettes from Kesha, Royal and the Serpent, and Rina Sawayama. Part 5 concludes by positing how future research might expand or incorporate the concept of prosodic dissonance.

2. Definitions and Parameters

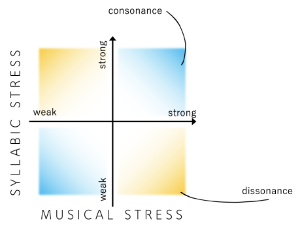

Example 1. A visualization of stress discrepancy and prosodic dissonance

(click to enlarge)

[2.1] If prosodic dissonance is a mismatch between linguistic and musical features, then the more these features conflict with each other, the stronger the dissonance. Similarly, the more they align, the stronger the consonance. Some aspects of language and music lend themselves more easily to such an alignment or misalignment. English has some features that music lacks (at least explicitly), such as lexical categories, semantic content, and consonants/vowels.(15) Similarly, music has some components that language does not explicitly, such as multiple simultaneous streams and a high degree of repetition. What they do have explicitly in common is stress—the most natural avenue for prosodic dissonance in English. We might imagine a stress discrepancy space as shown in Example 1,(16) where for any given moment, the more stress in the music (particularly the melody) compared to the less stress within the corresponding lyric, the more prosodically dissonant that moment will sound. Inversely, when the relative stress or accent levels between music and text align, the more prosodically consonant it will sound.

[2.2] In English, stress can occur at the level of an individual word, such as “unconditionally,” or at a phrase level, such as “I’m reading a book about music.” The default stress of a spoken phrase adds an additional layer, particularly given that phrasal stress is the only way of accounting for prosodic dissonance on monosyllabic words. Nevertheless, word stress has more potential for dissonance: For multisyllabic words, an unusually stressed word upends the prosody of the entire phrase (“I’m reaDING a book About music”), while increasing the relative emphasis of a word within the phrase can in some cases simply change the meaning (e.g., “I’m reading a book about music; she’s reading something else”).(17) For this reason, word stress is usually involved in the sense of misalignment, but particularly uncommon or semantically irrelevant phrase emphasis can also evoke prosodic dissonance. The less common a word’s default stress within a phrase (e.g., “I have an idea”), the more likely it becomes that emphasizing it melodically would sound dissonant.

[2.3] At this point, one major issue emerges: pronunciation, including prosody, depends on language, dialect, and individual speech expression. Syllable stress cannot be absolutely quantified without flattening the variety and identity attached to language. Though there are “official” recognized pronunciations for individual words, available in dictionaries, textbooks, and public educational resources, it bears remembering that these accounts capture (at best) the pronunciation of the majority of speakers and (at worst) the pronunciation in the dialect(s) of those in power. There are overall trends in pronunciation at population levels that make the discussion still worthwhile—or mutual intelligibility would be more of an obstacle than it is—but keeping that in mind, I do not advocate for strictly quantifying prosodic dissonance. Rather, I prefer to frame the degree of dissonance or consonance comparatively, relative to the surrounding context—with the understanding that the analyst’s own speech will be reflected in their interpretations.(18)

[2.4] Regardless, despite variations on the stress of individual words, stress is typically easily audible and intuitive for native speakers of English. In particular, the relationship between sung and spoken stress will likely be felt in relation to two main elements present in both: pitch and timing.

Pitch

Audio Example 2. Audio of false “sentence” made up of neutral syllables

[2.5] In English, one way of indicating spoken stress is by placing the stressed syllable on a higher (or, less commonly, lower) pitch than its surrounding contexts. In short, pitch changes mark distinctions. For instance, given wordless sentences with intonation only, as in Audio Example 2, it would be possible to determine which syllable is stressed, or even to match up the wordless sentences with text. Similarly, in music, the highest (or, less commonly, lowest) note of a phrase lends itself more easily to perception of accent, particularly if approached by leap.(19) For a prosodically consonant setting, then, we would expect the highest or most distinctive pitches in the music to align with the highest or most distinctive pitches in the text as we’d expect it to be spoken.

Example 2. A proposed consonant set of lyrics for Taylor Swift’s melody (for “You Need to Calm Down”, first verse)

(click to enlarge)

[2.6] Examples 2–4 are based on the first line of Taylor Swift’s “You Need to Calm Down” (2019). If we consider the melody without the text, we could compose a prosodically consonant set of lyrics, such as “going for a run in the morning” (Example 2). Similarly, if we consider the text alone, we could compose a prosodically consonant melody such as the one in Example 3, which emphasizes the stressed syllables “you,” “some-,” “don’t,” and “know.” In Taylor Swift’s rendition (Example 4), the single higher pitch in a stream of repeated pitches produces the effect of emphasis on “-dy.”(20) Here and for the remainder of the article, yellow circles show musical stress, while purple rectangles show stressed syllables.

Example 3. A proposed consonant melody for Taylor Swift’s text (for “You Need to Calm Down”, first verse) (click to enlarge) | Example 4. Taylor Swift’s actual text and melody (for “You Need to Calm Down”, first verse (0:08)) (click to enlarge and listen) |

Timing

[2.7] Coincidentally (or perhaps not), the highest pitch in the preceding phrase is also the longest, compounding the sense of accent. As discussed above, English has been described as a stress-timed language; its speakers expect stressed syllables to last longer on average than unstressed syllables. When sung, the lengths of syllables may be longer, with more flexible lengths. However, we still tend to hear longer notes, or longer inter-onset intervals (IOIs), as more stressed, and shorter notes or IOIs as weaker.(21) Furthermore, unlike conversational speech, music adds a metric component, which can compound or conflict with the effect of pitch. (I will discuss intersections with syncopation below in Part 3.)

Example 5. Taylor Swift’s actual text and melody for “

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 6. “

(click to enlarge)

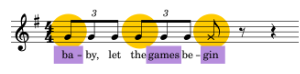

[2.8] In another one of Taylor Swift’s songs, “. . .Ready For It?”(2017), the bridge provides another example of durational prosodic dissonance, as shown in Example 5. The repeated lyric “Baby, let the games begin” would be consonant with a musical setting placing “ba-,” “games,” and “-gin” on the longest (and if unsyncopated, metrically strongest) notes. Instead, Taylor Swift sings the syllables completely evenly, pausing only after “-gin.” The syllables “ba-” and “-gin” are consonant here, but the equal duration and (unsyncopated) metric placement facilitate hearing “the” rather than “games” as the accented syllable, creating a moment of dissonance. In addition to “the” occurring on the beat, what furthers this effect is not so much a lengthening of “the” as a relative shortening of “games.” If we recompose the excerpt with a longer duration of this syllable, as in Example 6, the dissonance would be eliminated.

Example 7. Excerpt from Dua Lipa, “Levitating,” verse (0:13)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 8. Excerpt from Olivia Rodrigo, “good 4 u,” verse (0:54)

(click to enlarge)

[2.9] “. . .Ready For It?” also falls into a broader paradigm of prosodic dissonance that I see emerging in recent years: an evenly spaced melodic rhythm paired with an irregular rhythm in the lyrics. I call this prosodically dissonant isochrony, referring to the fact that the equal subdivisions of the melody (isochrony in the music-theoretical sense) conflict with the “equal” spacing of stressed syllables (isochrony in the linguistic sense). To illustrate this paradigm, compare the following excerpts from Dua Lipa, “Levitating” (2020) and Olivia Rodrigo, “good 4 u”(2021) (Examples 7 and 8). I encourage the reader to speak the text to each example aloud before and after listening to the musical renditions. Dua Lipa’s verse aligns the “isochronies” of the text and the melody, placing “had,” “-ni-,” “fell,” “rhy-,” and “mu-” on the pitch changes (and on the beats, with no syncopation) and lengthening the longer words “don’t” and “stop.” By contrast, the stressed syllables “car” and “-reer” land on less musically stressed moments of Olivia Rodrigo’s phrase: the pitch accents, which reinforce rather than undermine the beats, seem to emphasize the unstressed syllable “ca-.” As with Example 5, the even spacing seems to “shorten” the syllables that would be lengthened in speech. Though Examples 7 and 8 both feature evenly subdivided melodies landing squarely on the beats, the rhythmic experiences of the two differ enormously through the lyrics. Prosodically dissonant isochrony provides a uniquely clear illustration of how our rhythmic experience changes with our linguistic expectations.(22)

Prosodic Dissonance Litmus Test

[2.10] With pitch and timing as our basic parameters, we can begin to build a procedure for identifying prosodic dissonance.

Determine the prosody for the lyrics as you’d expect them to be spoken, ideally by speaking them aloud. Which syllables are strongest (most pitch-accented; longest) and weakest (least pitch-accented; shortest)?

Determine the prosody for the melody as sung, ideally by singing it aloud. Where are the phenomenal accents (particularly registral and durational)? If the moment in question is not syncopated, where are the strongest metric positions?

Given the first two steps, identify and interpret prosodic dissonance:

Identify places where the most stressed spoken syllables match up with the most unstressed sung notes or vice versa. These are moments of prosodic dissonance. The stronger the contrast, the stronger the dissonance.

If the moment in question does not sound prosodically dissonant, consider: Is there an alternate pronunciation of the text (e.g., contrastive stress, multiple accepted pronunciations), or an alternate hearing of the melody (e.g., different interpretation of the accent structure), that can account for the unexpected consonance?

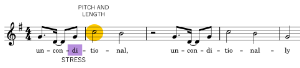

Example 9. Transcription of Katy Perry, “Unconditionally” (see Audio Example 1)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.11] To demonstrate this method, we can apply our litmus test to our initial Katy Perry example (transcribed in Example 9). The word “unconditionally” places stress on “un-” and “-di-” and the least stress on “-con-” and “-tion-”; the melody places the highest, longest, and (given a lack of syncopation) metrically strongest note on “-tion-.” In other words, the “mispronunciation” effect comes from an interaction of pitch and timing that produces strong prosodic dissonance. With the definitions and variables in place, we can proceed to examine some intersections and interactions between prosodic dissonance and linguistic and musical features.

3. Linguistic Features

Vowel Reduction: Accented and Created Schwas

[3.1] In English, stress strongly depends on the phenomenon of vowel reduction.(23) Weaker syllables occur more quickly to reach the next stressed, long syllable. In this process, vowels on weak syllables become more centralized in the mouth, most often becoming schwas.(24) Conversely, schwas are associated with weaker syllables. In fact, this may be the most aurally salient marker of stress/unstress in English, and intensifies difficulty understanding familiar words with shifted stress.(25) These sonic signals of “weakness” open up at least two possibilities for creating and/or intensifying the effect of prosodic dissonance: accenting a typically reduced vowel or creating a new schwa from a syllable not typically reduced.

Example 10. Lady Gaga, “Applause,” accented schwa in verse 2 (1:21)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.2] As an example of an accented schwa, see the second verse to Lady Gaga, “Applause,”(2013) transcribed in Example 10. In Lady Gaga’s English, the first and third syllables of the word “nostalgia” contain reduced vowels, with only the middle syllable emphasized: “nə-STAL-jə.” In her sung rendition, however, the pitch accent on the third beat lands on an unstressed syllable, creating prosodic dissonance. I argue that this dissonance is at least more noticeable, if not further intensified, by the melodic accent’s coincidence with a schwa.

Example 11. 5 Seconds of Summer, “Easier,” created schwa in prechorus (0:40)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.3] In the opposite case, some English-language singers reduce the vowel on a stressed syllable in prosodically dissonant contexts. Not only does this indicate that the singer also likely experiences this moment as prosodically dissonant, but it further contributes to the melody’s effect on the internal rhythm of the text for the listener. The prechorus to 5 Seconds of Summer, “Easier”(2019) includes one moment where this occurs (Example 11). At multiple points, Luke Hemmings reduces the vowel in the word “damn,” which would (particularly being an expletive) typically be emphasized in speech. This “created schwa” effect calls additional attention to the prosodic dissonance, compared to the timing alone.

Rhyme Creation and Emphasis

Example 12. Janelle Monáe, “Make Me Feel,” rhyme creation in verse (0:29)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.4] Prosodic dissonance often appears in relation to rhyming words and syllables. In this case, dissonance may seem to create a rhyme in the music that does not exist—or that exists in a much more subtle or understated fashion—in the text as it would be spoken. With the placement of musical (usually melodic) emphasis on typically unstressed syllables, weaker syllables and even reduced vowels become available for rhyming for expressive purposes.(26) This phenomenon is well documented in rap, where rappers sometimes use pitch, timing, or vowels to emphasize rhymes and create rhythmic variety.(27) However, it also occurs outside of rap, prosodically consonant contexts, and syncopated contexts as well. Example 12 shows an excerpt from a verse of Janelle Monáe, “Make Me Feel” (2018). Here, Janelle Monáe emphasizes the first syllables of “compression” and “confession” with pitch and timing, creating a rhyme between the weaker, typically vowel-reduced syllables “com-” and “con-.”(28) The words’ stressed syllables already rhyme, but that rhyme becomes secondary in the melodic context.

Example 13. The Kid LAROI and Justin Bieber, “Stay,” internal rhymes strengthened through prosody in chorus (0:07)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.5] While the previous example seems to create a rhyme that would otherwise be absent, prosodic dissonance can also strengthen weak internal rhymes at a phrase level. An excerpt from the song “Stay”(2021) by The Kid LAROI and Justin Bieber, reproduced in Example 13, uses strong pitch and timing indicators in the melody to shift the primary rhyme effect from “would/could” to “same/change/can’t/stay.” Though none of these vowels are reduced, only “change” and “stay” would receive stress in a spoken context. The repetition of the same melodic gesture reinforces the other two rhyming syllables, “same” and “can’t”—in other words, using parallelism to emphasize less prominent rhymes.(29)

[3.6] These linguistic features can be incorporated into our litmus test for additional nuance as follows (additions in underlined bold):

Determine the prosody for the lyrics as you’d expect them to be spoken, ideally by speaking them aloud. Which syllables are strongest (most pitch-accented; longest; with the clearest vowels) and weakest (least pitch-accented; shortest; vowel-reduced)?

Determine the prosody for the melody as sung, ideally by singing it aloud. Where are the phenomenal accents (particularly registral and durational)? If the moment in question is not syncopated, where are the strongest metric positions?

Given the first two steps, identify and interpret prosodic dissonance:

Identify places where the most stressed spoken syllables match up with the most unstressed sung notes or vice versa. These are moments of prosodic dissonance. The stronger the contrast, the stronger the dissonance.

If the moment in question does not sound prosodically dissonant, consider: Is there an alternate pronunciation of the text (e.g., contrastive stress, multiple accepted pronunciations), or an alternate hearing of the melody (e.g., different interpretation of the accent structure), that can account for the unexpected consonance?

Consider how the prosody changes the hearing of the text. Does it create or emphasize aspects of the lyrics (e.g., rhyme)?

4. Musical Features

Parallelism

[4.1] In Example 13 above, the rhyme is emphasized not only by pitch and timing within each individual line, but also by the repetition of the melody. The establishment of sameness and difference makes a strong impact on listener expectations through the effect of parallelism: If the pitches, rhythms, and duration repeat, we expect the prosody of the text to repeat as well. If the prosody changes while the melody does not, this has the potential to create prosodic dissonance through parallelism. Prosodic dissonance increases in salience and intensity when a stress pattern for a melody has already been established only to be changed on a subsequent reiteration. For highly repetitive melodies, this can also serve as a means for musical artists to add rhythmic variety through the text, even while maintaining consistency in other elements of the music.

Example 14. Ava Max’s original text and lyrics to “My Head and My Heart,” showing parallelism effect in first verse (0:00)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 15. Third line of “My Head and My Heart” recomposed to be syncopated and prosodically consonant

(click to enlarge)

[4.2] Example 14 transcribes an excerpt from Ava Max, “My Head and My Heart”(2020), which follows exactly the trajectory described above. The melody, including its stress pattern, remains the same through the first two and a half lines. The text also remains relatively constant in prosody: “I think about me now and who I could’ve been / And then I picture all the perfect that we lived.” Without the text, the third line sounds as an exact repetition of the first two; however, the lyrics change emphasis: “‘til I cut the strings on your tiny violin.” The lyrics’ emphasis moves from the fourth syllable (“the”) to the fifth (“strings”), creating prosodic dissonance through contrast with the previous lines and through the high-pitch, downbeat placement of “the.” One could imagine a recomposition of this passage to place the pitch accent on “strings,” creating a syncopation effect instead of prosodic dissonance (Example 15). Even then, the effect of parallelism creates fertile ground for dissonance, particularly in comparison to the consonant end of the line, “tiny violin.”

Interactions with and Differences from Syncopation

Example 16. Excerpt from Billie Eilish, “bad guy,” second verse (1:13)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.3] Previous scholars have documented a separate but related phenomenon regarding prosody and music: the use of syllable stress to create or reinforce syncopation (Temperley 1999, VanderStel 2021).(30) In both (stress-based) prosodic dissonance and syncopation, stress patterns misalign. However, as mentioned above, syncopation involves one or more musical layers (for our purposes, the text) misaligning with the stress pattern of the meter, while in prosodic dissonance, the stress pattern of the text (prosody) is dissonant with the stress pattern of the melody (typically defined by patterns of durational and registral accents)—whether it aligns with the meter or not. Prosodic dissonance may occur between the text and metric accents, but syncopation has the potential to undermine that effect. For example, the verses to Billie Eilish’s “bad guy” (2019) frequently anticipate the meter with the melody (Example 16), with many of the notes shifted off the beat. Despite the shifting, this doesn’t feel particularly dissonant: “like,” a strong syllable, gets a longer duration, as does the stronger syllable in “control.” The line “I told you I’d change” in Example 13 above also matches syllabic and melodic stress that does not land on the beat. Because the two phenomena involve different types of interactions between musical layers (text/metric accent vs. text/melodic accent), syncopation and prosodic dissonance can interact or operate independently. A moment may be syncopated but prosodically consonant, it may be prosodically dissonant and syncopated, it may be prosodically dissonant without syncopation, or, of course, it may be prosodically consonant and unsyncopated. Examples 17–20 provide hypothetical, simple examples of each.

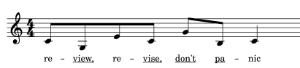

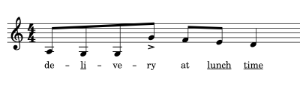

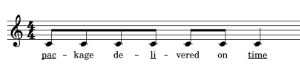

Example 17. An unsyncopated, prosodically consonant setting (click to enlarge) | Example 18. An unsyncopated, prosodically dissonant setting (click to enlarge) |

Example 19. A syncopated, prosodically consonant setting (click to enlarge) | Example 20. A syncopated, prosodically dissonant setting (click to enlarge) |

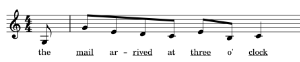

[4.4] In Example 17 an even, unsyncopated quarter-note pace pairs with four consecutive iambs (or weak-STRONG pairs): “mail,” “-rived,” “three,” and “clock.” Although the rhythm changes from the spoken rendition, which would shorten the weaker syllables compared to the stronger ones, the relative emphasis of the lyrical and musical accent streams still align, making the excerpt prosodically consonant. Contrast this with Example 18, which takes the accented syllables “-view,” “-vise,” “don’t,” and “pa-” and places them musically in various states of stress. Yet, the accent pattern of the melody does not allow for a syncopated hearing; it is unclear which events would be stressed to allow such an interpretation. Example 19 provides the opposite context, with the stressed syllables of the text evoking a tresillo.(31) Because of this pitch accent and apparent syncopation, “de-” and “-vered” do not sound prosodically dissonant, particularly if we reduce the vowel for the first syllable. Finally, Example 20 uses both prosodic dissonance and syncopation: syncopation in the melodic stream (which, like Example 19, is grouped by contour into 3+3+2), and prosodic dissonance in the resulting emphasis of “de-” and “-ry” as well as a relative shortening of “lunch.”

[4.5] Given that word/sentence stress can specifically lead us to hear syncopation, the two effects can sometimes be difficult to differentiate. In these cases, a prosodically dissonant hearing and a syncopated hearing can be framed as competing modes of listening: If the linguistic features (such as syllabic stress patterns) are prioritized, or seem to overwhelm the musical features, the lyrics can create or reinforce syncopation—in other words, the features of the language are superimposed onto the music. If, in contrast, we mentally prioritize the musical features, this can overwrite the features of the lyrics, causing us to hear prosodic dissonance.

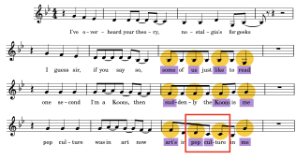

Example 21. Parallelism in the melody of Lady Gaga, “Applause” (second verse) causing prosodic dissonance (1:21)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 22. Prosodically consonant syncopation when focusing on the background synth in “Applause”

(click to enlarge)

[4.6] The ambiguity between syncopation and prosodic dissonance is particularly salient when we move beyond the accent structure of the melody to other musical layers, as in Example 21 (another excerpt from “Applause”). The moment in question is the sung rendition of “art’s in pop culture in me” at the end of the verse. The stressed syllables here as spoken are “art,” “pop,” “cul-,” and “me.” Without any clear syncopation in the melody, and with a repeated step down gesture on each of the four quarter notes, the emphasis ends up on “-ture” instead of “cul-,” causing a moment of dissonance. Parallelism intensifies this further, with the previous phrases ending with “some of us just like to read” and “suddenly the Koons is me,” both of which have a prosodically consonant strong syllable on beat 3.(32) However, drawing our attention to the accompanying tracks rather than the melody alone can lessen the experience of prosodic dissonance and even shift it to a syncopated hearing. The melodic synthesizer present from the very beginning of the song, transcribed in Example 22, articulates a tresillo pattern behind each phrase, which conflicts with the first two lines of the lyrics but comes to fruition with the similarly tresillo-evocative prosody of “art’s in pop culture in me.” While this article has so far focused exclusively on melody, since the singing itself is a natural place to look for prosodic dissonance, this example demonstrates that other musical layers can also affect the prosody, if less overtly. By shifting our focus to different aspects of the music, we can toggle between two distinct rhythmic listening experiences of this passage—parallelism or the synthesizer, speech or song, syncopation or prosodic dissonance.

Example 23. Modification of Example 19 increasing musical emphasis on “-vered”

(click to enlarge)

Example 24. Modification of Example 19 demonstrating default prosodic consonance

(click to enlarge)

[4.7] In cases like “Applause,” we may be able to control or choose our hearing by shifting our focus, but there are elements that contribute more generally to the possibility of hearing something as syncopated or prosodically dissonant. The more musical emphasis on a weak syllable—through pitch, duration, metric position, timbre, articulation, or a combination of the above—the more prosodically dissonant a moment will sound. Similarly, the less musical differentiation or accent there is—or the more musical support for a strong syllable there is—the more possible it becomes to hear syncopation. Parallelism, vowel shape, and rhyme, discussed above, can further reinforce one of these hearings. For example, if we removed the octave leap in Example 19 and lengthened the weak syllable, the resulting musical emphasis on “-vered” would tip the balance back toward prosodic dissonance, as shown in Example 23. Yet if we were to change the setting to be as uniform as possible, as in Example 24, we would likely still favor a syncopated hearing. In other words, when possible, we prefer a hearing that aligns features of music and lyrics.(33) Since rap frequently uses only minimal melodic features, this preference also accounts for the relative lack of prosodic dissonance—and relative prevalence of lyric syncopation—in rap music as compared to sung music.(34)

[4.8] The availability of a syncopated hearing also connects to the accent structure of the text itself. If stressed syllables in the lyrics are more evenly distributed, we may be able to mentally shift our musical accent structure to hear syncopation. If, however, the text has adjacent stressed syllables (sometimes called a spondee in discussions of poetic rhythm) or long strings of weak syllables, it may be much more difficult to conjure a syncopated version of the text. We can speak with adjacent stressed syllables in English, but we cannot perceive two quick adjacent accents in music as easily (Ohriner 2019b). In Example 18, the three adjacent accents in “-vise, don’t pa-” render it more difficult to “shift” our sense of accent to hear it as syncopated. In short, features of the music and language can privilege or exclude prosodic dissonance, privilege or exclude syncopation, or contribute to a paradoxical experience where both are simultaneously present.

Phrase Breaks

[4.9] Thus far, all the features discussed linguistically and musically have centered on stress and accent. However, prosodic dissonance consists of any conflict between linguistic and musical features. Another related but distinct feature of music and language is the concept of phrase, particularly boundaries between phrases, marked most frequently by pauses (timing). Particularly since streams of spoken language do not usually place pauses between individual words, what pauses and breaths are present usually indicate breaks between ideas and thoughts. Similarly, we teach our students to listen for resting points to distinguish musical phrases.(35)

[4.10] When the phrases in the music and lyrics begin and end at different times, this produces a distinct category of prosodic dissonance, which I call enjambment dissonance.(36) More specifically, enjambment dissonance occurs either when a musical phrase continues across what would constitute a phrase boundary in speech, creating a run-on effect, or when a musical phrase boundary occurs in the middle of a spoken phrase, creating an interruption effect.

Example 25. Frankie Bird, “Paper Doll,” enjambment dissonance through omission of “line break” in first verse (0:02)

(click to enlarge)

Example 26. Ariana Grande, “positions,” enjambment dissonance through addition of “line break” in first verse (0:04)

(click to enlarge)

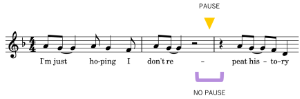

[4.11] For an example of the former, see Example 25 from Frankie Bird, “Paper Doll”(2017). The song begins with an ambiguous case of prosodically dissonant isochrony, creating an effect somewhere between syncopation and prosodic dissonance as she sings “wake up in the morning.” The following lyric would normally be composed of two units, with a brief lengthening of the duration between them: “got no makeup on / that’s fine by me.” However, Frankie Bird’s rapid, even delivery eliminates the space between the two lines of text, creating enjambment dissonance on top of the prosodically dissonant isochrony of the individual phrases. Compare this sound to Example 26, an excerpt from Ariana Grande, “positions”(2020). The lyrics to this passage, “I’m just hoping I don’t repeat history,” would typically be spoken as one unit. Ariana Grande’s delivery separates them into two segments, adding space between the two syllables of “repeat” to create a feeling of interruption. Furthermore, her choice to pronounce rather than reduce the vowel in “re-” further reinforces the phrase-ending emphasis on this syllable.(37)

[4.12] As these two examples show, enjambment dissonance can co-occur and interact with syllable-stress-based prosodic dissonance. The elements in common between music and language offer more than just opportunities for text painting, musical speech or speech-like music—they highlight a fundamental difference between texted and untexted music. Text and music can constitute two distinct layers of sound: layers whose independence is imperceptible without illuminative conflict between them. Such conflict—prosodic dissonance—is rife with analytical and interpretive questions.

[4.13] Before applying these principles to some more extended musical examples, it bears updating our procedure one final time:

Determine the prosody for the lyrics as spoken, ideally by speaking them aloud. Which syllables are strongest (most pitch-accented; longest; with the clearest vowels) and weakest (least pitch-accented; shortest; vowel-reduced)? Where do we put pauses or resting points? Is there any parallelism with the prosody of the surrounding lyrics?

Determine the prosody for the melody as sung, ideally by singing it aloud. Where are the phenomenal accents (particularly durational and registral)? If the moment in question is not syncopated, where are the strongest metric positions? Where do we hear pauses or resting points? Is there any parallelism with the prosody of the surrounding melody? Does the melody, or one of the other musical layers, lend itself to hearing syncopation that changes any of the above interpretation?

Identify places where the most stressed spoken syllables match up with the most unstressed sung notes or vice versa.

Identify places where the most space between spoken syllables matches up with the least space between sung notes or vice versa (enjambment).

Consider how previous material shapes our hearing of prosody. Does any parallelism intensify or lessen the apparent misalignment?

If the moment in question does not sound prosodically dissonant, consider: Is there an alternate pronunciation of the text (e.g., contrastive stress, multiple accepted pronunciations), or an alternate hearing of the melody (e.g., syncopation, different interpretation of the accent structure, parallelism with a previous event), that can account for the unexpected consonance?

Consider how the prosody changes the hearing of the text. Does it create or emphasize aspects of the lyrics (e.g., rhyme)?

Given the first two steps, identify and interpret prosodic dissonance:

These are moments of prosodic dissonance. The stronger the contrast, the stronger the dissonance.

5. Analysis and Tension

[5.1] To showcase this more nuanced version of this process, I offer three brief interpretive vignettes featuring prosodic dissonance in different ways.

Variety and Destabilization in Kesha, “Tonight”

[5.2] Kesha’s 2020 song “Tonight” depicts an energetic, drug-filled night of partying. In this song, Kesha alternates between the powerful and emotional pop-ballad vocal persona of her more recent songs (e.g., “Praying”) and the pitch-expressive, creaky-voiced rapping characteristic of her earlier hits (e.g., “TiK ToK”).(38) The verses embody the latter persona, each consisting of four two-measure streams of even subdivisions.

Okay, we’re going out tonight, don’t wanna stay home

I got my girls to call the Uber ‘cause I can’t find my phone

I’m getting ready, mani-pedi, fancy shit with the leathers

Now we’re looking for some trouble like we hunting for treasure

Example 27. Contour and rhythm for first verse of Kesha, “Tonight” (0:48)

(click to enlarge)

[5.3] These four lines group into two pairs, with each pair having matching rhythms and rhymes. The second pair of lyrics contrasts with the first by adding a syllable and changing the rhyme. However, the distribution of stressed syllables stays the same between the first and second pairs, which is also reflected in Kesha’s musical delivery. “Home” and “phone,” despite occurring ahead of the beat, receive a longer duration such that the melodic accent still aligns with the syllabic stress. In the following two lines, Kesha places a higher relative pitch on the strong syllables “lea-” and “trea-” such that the text is still prosodically consonant. We could represent the contour of this verse, as well as its corresponding stress pattern, as shown in Example 27.

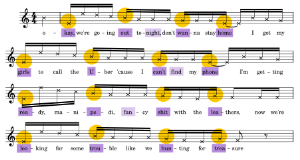

[5.4] The second verse’s prosody follows a different trajectory. Once again, Kesha raps in even sixteenth-note subdivisions with anticipatory syncopations on the last syllable of each line. This time, however, all four lines have exactly the same rhythm of twelve sixteenth notes, each ending with an [æk(t)] rhyme.(39) The first two lines follow the same pattern as the first verse:

Okay, we staying out tonight, there’s no turning back

I got my shorties up so high, bet y’all think I’m running track

The second couplet, in contrast to the first verse, makes significant changes to the prosody while maintaining the same number of syllables.

Just found out me and Elton John have the same shoes, that’s a fact

Hey Chelsea, do you mind if I put this wine in your backpack?

[5.5] The stressed syllables “me” and “John” sound consonant in parallelism with the previous line, particularly since they align with the beat (and a slight heightened pitch on “John”). From here, we would expect “same,” “shoes,” and “fact” to be emphasized, with a pause where the comma is. Instead, five elements contribute to a prosodically dissonant setting that beautifully summarizes the above. First, Kesha’s rapping intonation places pitch accents on “the” (a weak syllable) and “shoes,” higher than the intervening “same” (a strong syllable). Second, the text itself has two consecutive stressed syllables (“same shoes”), making a mental shift to syncopation impossible. Third, the emphasis on the vowel-reduced syllable “the,” coupled with a slight backing-up and near monophthong-ization of the diphthong in “same”—[seɪm] becomes something closer to [sɛɪm]—adds phonetic emphasis to the dissonance. Fourth, the parallelism from the previous two lines’ consonance makes the text stick out by comparison. Finally, the short duration between “shoes” and “that’s” (where we would expect a pause) creates enjambment dissonance before bringing the listener abruptly out of the prosodic dissonance and back into the following consonance (“that’s a fact”). Within a few seconds, this third line of text begins with prosodic consonance (“Just found out me and Elton John”), abruptly shifts to dissonance (“have the same shoes”), and ends with brief consonance (“that’s a fact”). In contrast with the previous verse and two preceding lines, this drastically upends Kesha’s established prosodic flow, introducing instability and ambiguity.

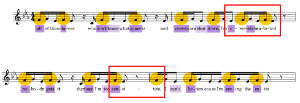

Example 28. Kesha, “Tonight,” prosodic dissonance shifting to syncopation in second verse (1:30)

(click to enlarge)

[5.6] The next line of lyrics, “Hey Chelsea, do you mind if I put this wine in your backpack?” achieves a different effect from any of the previous three lines. If we listen according to the prosodic rhythm established by the first two lines—the same rhythm that contributed to the dissonance of the previous line—this lyric would also begin from a point of relative consonance (“hey Chelsea, do you mind”) and move to dissonance (“if I put this wine in your backpack”). However, Kesha’s delivery pitches “I,” “wine,” and “back-” slightly higher relative to the surrounding syllables, supporting a prosodically consonant, syncopated hearing with a tresillo starting on beat 2. This supports and is supported by the internal rhyme “mind” and “wine.” The dissonance in the third line upends the established prosodic rhythm, providing a transitory state to move to a consonant, but more syncopated, flow.(40) Example 28 shows a transcription of the second verse.

[5.7] The interaction of prosody and syncopation here adds variety and direction to four otherwise rhythmically identical lines of lyrics with the same rhyme. At this point, we could add an interpretive “step 7” to the litmus test. In this case, I would suggest that the messy and fluid transition between prosodic states adds to the narrative of the song, effecting a loose, clumsy, spontaneous sound to match the drunken, carefree attitude of Kesha’s narrator. As the verse progresses, the text moves from rigid, consistent, and organized to loose and flexible, just as the narrator moves from sobriety to inebriation. The narrative of a wild night out extends to the delivery of the lyrics themselves.

Expressive Enjambment and Text Painting in Royal & the Serpent, “Overwhelmed”

Example 29. Royal & the Serpent, “Overwhelmed,” line breaks for first verse excerpt as one would expect it to be spoken (0:10)

(click to listen)

[5.8] Royal & the Serpent’s song “Overwhelmed,” also released in 2020, makes pervasive use of prosodic dissonance, including enjambment dissonance and rhyme interactions. This relationship begins right from the start of the song, with a stark discrepancy between the musical delivery and groupings of the lyrics (Example 29).(41)

Example 30. Royal & the Serpent, “Overwhelmed,” line breaks for first verse excerpt as sung

(click to enlarge)

[5.9] The first few words, “Turn off the TV,” already sound slightly dissonant on their own; the relative high pitch of “T-” suggests a syncopated hearing that emphasizes this syllable (whereas “TV” would often be pronounced with two consecutive stressed syllables). The next lyric, however, overwhelms this sense of dissonance with a much more noticeable instance: “it’s starting to freak me—.” Royal & the Serpent breaks off the musical phrase in the middle of the text’s phrase, using silence to reinforce the effect, and then continues as the next musical idea begins, omitting the break between “out” and “it’s.” Parallelism from the first line (“starting to freak

[5.10] This visual representation of enjambment dissonance in the lyrics, altered to reflect the musical context rather than the structure of the lyrics alone, is also used by all three of the top “lyrics videos” for the song on YouTube at this time of writing, indicating that the perception of this enjambment dissonance is widely heard by listeners.(42) The lyrics and the music both use a short-short-long motivic structure, but whereas the melody uses two short ideas of equal length, the text’s short ideas have different numbers of syllables, with phrases gradually increasing in length. The notion of “short-short-long” therefore effects different rhythmic experiences as we hear conflicting phrase rhythms through the prosody. In this way, Royal & the Serpent outlines a metaphorical arch shape from accent-based prosodic dissonance to enjambment dissonance and back again, affecting the perception of tension in the first two lines. Setting a precedent that will recur throughout the song, the enjambment-dissonant placement of “out” also reinforces the internal rhyme with “loud.”

Example 31. Royal & the Serpent, “Overwhelmed,” strong syllables in second half of first verse (0:16)

(click to listen)

[5.11] The following two lines, despite having the same melody and rhythm, provide contrast with relative prosodic consonance in the places where dissonance occurred previously (Example 31). The first verse leading up to the prechorus, then, follows a path from dissonant to consonant phrase breaks, creating tension and release between the first and second couplets. Before discussing the prechorus and chorus sections, let us compare this verse to the second verse, which heightens and develops some of these effects.

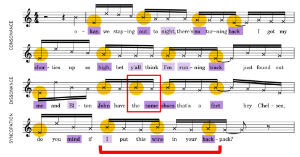

Example 32. Royal & the Serpent, “Overwhelmed,” second verse (0:55)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[5.12] Liaising with the title line that ends the chorus, the second verse also begins with prosodic consonance: “All of these faces who don't know what space is.”(43) From here, Royal & the Serpent’s prosody begins to desynchronize with the melody once more, culminating with an apparent delivery of “overstimulated” (rather than “overstimulated”), a hearing supported by previous parallelisms as well as the recurring melodic accents on F. I interpret this prosodic dissonance as a form of text painting, illustrating the narrator’s discomfort, sense of nonbelonging, and difficulty conforming to expected social norms. This process continues in the next line, which once again begins with consonance (“nobody gets it”) before placing the strongest dissonance on a word describing the narrator (“sensitive”). The placement of “-tive” in the following musical subphrase creates the same enjambment dissonance pattern as the very first couplet, this time breaking a musical phrase in the middle of a word. In the line following “sensitive,” Royal & the Serpent adds more syllables, creating the most syllable-dense line of both her verses together. The setting is relatively consonant, stressing the strong syllables “list-,” “eye-,” and “ex-” as shown in Example 32); however, the inserted additional syllable contributes to the information density, further expressing the sentiment of the song.

[5.13] In both verses, particularly the second, prosodic dissonance reinforces the narrative, conveying the speaker’s feelings of overstimulation and sensitivity. The sense of social rigidity or expectation is further supported by the insistent repetition of the pitch F as every single melodic accent. Interestingly, this rigidity does not always match the meter; anticipatory syncopation is plentiful throughout this song. At some points, the prosody aligns with this syncopation; in other places, prosodic dissonance arises as an effect of ignoring this syncopation. The awkwardness and disjointedness of some of the lyrics, coupled with the rigidity of the metronomic texture, make the lyrics themselves sound overwhelmed and out of place, as if the speaker’s emotions are struggling to fit into the confines of the song and conveying the sentiment in the song’s lyrics.

[5.14] The prechoruses and choruses are more consistently consonant by comparison, suggesting a prosodic variant on the “loose verse, tight chorus” model (Temperley 2007)—or textural stratification, if we consider text to be a textural element (Covach 2018). While the verses play with strong enjambment and accent dissonances to convey discomfort, the percussion and repetition in the chorus express the narrator’s anxiety through a rigid, inflexible melodic accent structure. Finally, one additional moment of timing-based prosodic dissonance in the chorus further contributes to the text painting: Royal & the Serpent’s delivery of the line “makes it hard to breathe” slightly condenses the expected pacing of these syllables, placing “hard” and “breathe” closer together compared to “makes.” This suggests a rushing through the syllables, directly conveying the breathlessness expressed in the lyrics themselves.

Shifting Parallelism and Rhyme in Rina Sawayama, “This Hell”

[5.15] The first verse of Rina Sawayama’s “This Hell”(2022) establishes the song with a high degree of prosodic dissonance before a largely consonant chorus. Unlike the previous two examples, however, the effect of the prosodic dissonance resists parallelism and recontextualizes lyric emphasis rather than evoking clear text painting.

[5.16] The opening line conveys persistent dissonance throughout as Rina sings, “Saw a poster on the corner opposite the motel.” Whereas the strongest syllables in speech would be “post-,” “cor-,” “op-,” and “-tel,” the musical context suggests an alternative distribution of stress. First, the rhythmic repetition in the melody groups “poster on” with “corner op-,” deemphasizing the latter syllable in favor of the weaker “-site.” The two slightly higher pitches on “-site” and “mo-” then suggest stress for these syllables.

Example 33. Rina Sawayama, “This Hell,” shifting perceptions of prosody at the start of the first verse (0:20)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[5.17] The next line, “Turns out I’m going to hell,” reshapes the dissonance on “motel.” With a rhyme and a stressed syllable in the same (final) position of each line, and with a longer duration between the onsets of “-tel” and “turns,” the slight pitch accents on C are overwhelmed by the possibility of a consonant, syncopated hearing, as shown in Example 33. The third line’s rhyme, “’fI keep on being myself,” further intensifies the shift, to the point where any dissonance on “motel” vanishes in retrospect. Parallelism and rhyme here lead us back to prosodic consonance—as opposed to a hypothetical alternative set of lyrics with a stress pattern reinforcing the initial dissonance and removing the rhyme, such as “although I’m doing nothing” / “they say I’m sinning daily.”

Example 34. Rina Sawayama, “This Hell,” prosody across the whole first verse (0:20)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[5.18] Just as this consonance solidifies, the second half of the verse undermines it by beginning abruptly on the downbeat, truncating the length of the stressed syllable “-self” (Example 34). This enjambment dissonance is particularly salient in combination with the consecutive stressed syllables “-self” and “don’t.” Softening this effect, the official music video for the song also places a sudden cut between the two syllables, even though the previous three lines are all lip-synced in a single shot. The resulting rapid and difficult consonant cluster “lfd” contributes to a feeling of “self-interruption,” particularly audible in live performances.(44)

[5.19] The following line, “Don’t know what I did,” returns to prosodic consonance momentarily, with the longest pitches placed on the longest spoken syllables “don’t,” “know,” and “did.”(45) This time around, both “don’t” and “know” sound consonantly accented with the even quarter notes and corresponding hits in the backing track, slightly contrasting with the stress pattern of “saw a” in the previous instance.(46) The consonance is short-lived as the next lyric begins: “they seem pretty mad about it.” As an effect of the pacing that lengthens “they” and “pret-,” Rina reduces the vowel in “seem” to a schwa, creating a disjuncture between the lyrics’ and melody’s stress tendencies. Furthermore, whereas the emphasis in the text “mad about it” would be consonant with stress on “mad” and “-bout” (supported by the pitch accents), the parallelism of the previous lyrics, “going to hell” and “being myself,” gives the conflicting impression of emphasis on the last syllable, “it.” The ending rhyme with “did” intensifies the viability of this hearing.

[5.20] Thus far, in under 13 seconds of music, Rina Sawayama fluctuates rapidly between consonant and dissonant states in her delivery, each state intensifying the effect of the other. Parallelism first changes us to the less dissonant, syncopated hearing in Example 33, which in turn increases the prosodic dissonance of “mad about it” (see Example 34). Rhyme, parallelism, and syncopation constantly vie for auditory priority, contradicting one another and presenting a variety of possible experiences of the verse—all of which will include some degree of prosodic dissonance.

[5.21] While “This Hell” proceeds to a more consonant prechorus, chorus, and second verse, seeming to respond to some of the tensions of this first verse, one more salient moment of dissonance stands out: the phrase “damned for eternity,” with the final syllable “-ty” emphasized through length, pitch, rhyme with the following line, and parallelism with the previous lines. This moment signals a possible expressive correlation of prosodic dissonance in this song: an association with the homophobic perspective of others. The conflicting prosody of the lyrics seems to represent the restrictiveness of societal expectations, with the consonance that follows expressing the comfort of pride and authenticity. Rina’s prosody seems to mock the discomfort of the angry rioters who would damn her for her queerness.

[5.22] Prosodic dissonance plays a different role structurally and expressively in each of these three examples. By recognizing and qualifying it not (or not only) as a mark against artistic value, but as another avenue for expression, conflict, and variety in texted music, we gain an entirely new layer of analytical opportunities: prosody. This layer cannot exist without the musical setting, since the text would have no pitch, timing, or phrasing to conflict with; it similarly cannot exist without text, since prosodic dissonance would be imperceptible and meaningless without an intuition for that language’s pronunciation.

6. Future Study of Prosodic Dissonance

[6.1] Because they are interdisciplinary by definition, investigations of prosodic dissonance lend themselves well to a variety of further research topics, including intersections with structure and form, corpus studies, differences between languages, cognitive studies, questions of compositional process and reception, analysis of text and musical accent alone, stylistic norms, linguistic change, music theory pedagogy, and notational/visual representations.

[6.2] In all three of the analytical examples in Part 4, the majority of prosodic dissonances occur within the verse, suggesting a prosodic link to Temperley’s (2007) “loose verse, tight chorus” phenomenon. Whereas Temperley’s paradigm describes coordination or separation of melody and harmony (the “loose” descriptor applying to the “melodic-harmonic divorce”), further research could be done on prosodic dissonance as analogous to a “text-melody” divorce.(47) My initial impression is that prosodic dissonance is less common in choruses, marking “Unconditionally” as a notable exception and offering a partial explanation as to why it received more negative attention than other prosodically dissonant songs. Further analyses, either at the level of individual pieces or entire corpora, could shine light on the formal associations of this phenomenon. Regardless of how verses and choruses interact with prosodic dissonance, we could also experiment with prosodic dissonance as form-defining in the sense that it can shape our experiences of tension, rhythmic complexity, and consonance.

[6.3] As discussed in the introduction, there is some precedent for encoding linguistic stress in musical corpora. This type of feature can be extended to include vowel reduction, distinctions between primary and secondary stress, or even the presence, absence, or ambiguity of prosodic dissonance itself. Prosody could be added as an additional layer to existing corpora or used as the basis for new encoding. Corpus studies that include prosodic dissonance will enable a much wider array of large-scale analytical questions, including tracking the historical or stylistic development of prosodic dissonance, connections to particular artists or years, or even the overall presence or absence of prosodic dissonance within popular songs conceived broadly.

[6.4] This article has restricted its purview to English prosody, but each spoken language will have different elements to align or conflict with musical ones. How does prosodic dissonance change for syllable- or mora-timed languages, such as French or Japanese? Languages with different indicators of syllable stress or phrasing could lead to new types of prosodic dissonance not available or common in English. Tonal languages, such as Cantonese, also open up the possibility of a new dimension of dissonance based on pitch or contour.(48)

[6.5] I have consistently referred to the strength or presence of prosodic dissonance; behavioral and cognitive studies will be necessary to determine its impact. How do different musical contexts for the same text, or different texts for the same musical context, produce, strengthen, or weaken prosodic dissonance? Which types produce negative value judgments and which do not? What circumstances might lend themselves to “prosodic paradoxes” that split a pool of listeners between syncopated and prosodically dissonant interpretations? Are prosodically dissonant lyrics more difficult to remember or reproduce? These and other research questions offer new avenues into the exploration of music-language intersections.

[6.6] Though participant studies can illuminate one category of causes for prosodic dissonance, we might adopt a musicological approach and search for causes in the songwriting process. Can we trace a rise in prosodic dissonance to particular songwriters or songwriting teams? In cases where the melody and lyrics are penned by different authors, is prosodic dissonance more common? Is syllable alignment a common consideration in the music industry? In short, to what degree are these types of effects compositionally intentional and to what degree are they byproducts of other priorities and processes?

[6.7] The organization of the text or music itself could also be a line of investigation. In cases of prosodic dissonance, we can examine patterns of syllabic stress, regularity, and phrasing. I would hypothesize that a text with a more irregular distribution of stressed syllables would correlate with higher instances of prosodic dissonance, as would highly isochronous streams of equal subdivisions in the melody. In cases with spondees, or two consecutive stressed syllables, I would similarly expect that one rather than both would be musically accented. Lastly, we could propose certain types of musical contour that facilitate or preclude the commonality of prosodically dissonant settings.

[6.8] All of the examples used in this article have been pop (or pop-adjacent) music. However, as noted in the introduction, prosodic dissonance occurs in genres from rap to emo to early-twentieth-century French art song. These contexts all differ from one another; while prosodic dissonance in rap may offer more intersections with rhyme creation/emphasis and syncopation (Duinker 2022), many instances in punk and emo music of the last two decades contribute to the DIY aesthetic noted by previous authors (Chiu and Blake 2021). Analyzing prosodic dissonance in classical genres opens a new, if related, set of questions, since many of the texts predate their musical settings rather than being co-created. Prosodic dissonance can be a marker of musical style or individual artistry, helping to define or cross genre boundaries. The perception of its presence or absence, therefore, will likely be affected by the genre and by the typical listening habits of those asked.

Audio Example 3. Olivia Rodrigo, “brutal,” first verse (0:18)

[6.9] Continuing the long list of fruitful future research topics, prosodic dissonance also relates to vocal delivery and timbre. Not only might vowel sounds other than reduction be grounds for prosodic dissonance on their own—e.g. re-pronouncing words in order to rhyme them—I also hypothesize that how speechlike or songlike an artist’s delivery sounds can intensify or weaken the effect of prosodic dissonance. For instance, Audio Example 3 contains an excerpt from Olivia Rodrigo, “brutal,” which evokes a speaking quality. The prosodic dissonance in this example is particularly jarring, owing in large part to her delivery: the combination of her low conversational tone with the apparent shift in emphasis from the musical context suggests the very awkwardness depicted in the lyrics. Similarly, some melodies with more songlike qualities might soften the effect of dissonance—unless the pitch of the melody seems to add to that conflict. The timing of artists’ breaths can also affect the suggestion of phrase breaks, perhaps independently from duration itself (Beaudoin 2024). The growing subfield of timbre studies benefits from the inclusion of interdisciplinary, linguistic notions such as phonetics, dialect studies, and vocal tone.(49)

Audio Example 4. Queen, “Somebody to Love,” emphasis on first syllable (0:47)

Audio Example 5. Smash Mouth, “All Star,” emphasis on second syllable (0:00)

[6.10] Of course, language constantly shifts and changes as a result of many interacting social factors. When a mispronunciation of a word becomes common to a group of speakers rather than one individual, it ceases to be a mispronunciation and becomes a marker of style, dialect, or other meanings. Another area for future research would be to choose music performed by speakers of different dialects (British dialects, American dialects, Australian dialects, Singaporean dialects, AAVE, etc.) and compare their treatment of prosody. It also follows that the perception of prosodic dissonance will depend on the rarity of a given pronunciation—what I call the “somebody effect.”(50) Even if a word’s pronunciation does not change in speech, its expected sung emphasis can migrate, for example, in the common placement of stress on either of the first two syllables of “somebody” (see Audio Examples 4 and 5).(51) Further cognitive and linguistic studies would be necessary to understand more fully the extent and conditions of this overexposure effect.

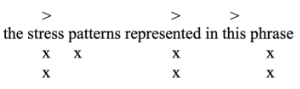

Example 35. One possible visualization of accent-based prosodic dissonance, with > showing sample musical stress and x showing syllable stress

(click to enlarge)

[6.11] One interesting area for future research, alluded to earlier in the article, is the potential for visualization techniques for prosody as set in music. While there is precedent for using visual elements of the written text itself for this purpose, such as CAPitaliZAtion, italics, line / breaks, or

[6.12] Finally, the pedagogical opportunities of prosodic dissonance will in turn illuminate more about this phenomenon, its perception, and its creation. Students could experiment with writing prosodically dissonant and consonant settings for a particular text—or prosodically dissonant or consonant text for a particular melody. Other assignments might challenge them to adjust existing songs to increase, lessen, or change elements of prosodic dissonance and consonance, to find some examples themselves, to identify it aurally, or to write analytical essays on patterns and roles of prosody in particular songs or artists’ discographies.

[6.13] I conclude this article with a plea for descriptivism: introductory linguistics textbooks begin by highlighting that the goal of this field is not to “correct” language, but to observe it.(54) I believe music theory could benefit from this shift at every structural level. When we encounter what we initially interpret as bad text setting, or any other type of “mistake,” particularly in popular music, it would serve us better to approach it with curiosity in addition to or instead of arbitration. While one anomaly could be a sign of misunderstanding what musical traits a genre typically employs, or of importing traits from one style to another, repeated instances of the same anomaly make a pattern that changes what the traits are of the style itself.(55) Rather than—or at least in addition to—laughing at apparent “mispronunciation” or heralding it as a sign of the decline of art (as amateurs and professional theorists have done throughout history), we only stand to gain from setting aside our value judgments and asking why this sounds mispronounced and what that does to our musical experience.

[6.14] So what of “Unconditionally”? We could craft a variety of narratives accounting for Katy Perry’s prosodic dissonance in Audio Example 1 and Example 9. Is it a simple case of bad text setting, a byproduct of music and lyrics composed separately, an unintentional use of prosodic dissonance that can nevertheless support our analytical agendas, a reflection of a larger growing discrepancy between English as sung and spoken, or a deliberate “mispronunciation” to gather media attention or make a comment about the conditional love of pop fans? If it is the clarity of compositional intent that determines the difference between artistic expression and bad text setting, we may be missing the point of analysis altogether. There is not, nor can there be, a single “correct” interpretation, but any of the above could be supported or at least investigated. Whether or not Katy Perry and her songwriting team intended it, I choose both to laugh uncomfortably at her rendition of the title word, then to interpret my own discomfort exactly in line with the intended message of the song: regardless of apparent flaws, embarrassing missteps, or music-theoretical naïveté, the narrator proclaims acceptance and love of the whole listener.(56) The song expects the discomfort of our angry tweets and well-meaning pedagogy and dares us to enjoy it unconditionally—whether we ultimately choose to or not.

Eron Smith

Oberlin College & Conservatory

77 W College St, Oberlin, OH 44074

esmith9@oberlin.edu

Works Cited

Adams, Kyle. 2008. “Aspects of the Music/Text Relationship in Rap.” Music Theory Online 14 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.14.2.3.

—————. 2009. “On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music.” Music Theory Online 15 (5). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.15.5.1.

Albert, Sara W. 2021. “A Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of Prosodic Dissonance in Post-Millennial Pop Music.” Bachelor’s capstone project, University of Pennsylvania.

Aroui, Jean-Louis, and Andy Arleo. 2009. Towards a Typology of Poetic Forms: From Language to Metrics and Beyond. John Benjamins Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1075/lfab.2.

Arvaniti, Amalia. 2009. “Rhythm, Timing, and the Timing of Rhythm.” Phonetica 66 (1-2): 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1159/000208930.

Arvaniti, Amalia. 2012. “The Usefulness of Metrics in the Quantification of Speech Rhythm.” Journal of Phonetics 40 (3): 351–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2012.02.003.

Attas, Robin. 2011. “Sarah Setting the Terms: Defining Phrase in Popular Music.” Music Theory Online 17 (3).

BaileyShea, Matt. 2021. Lines and Lyrics: An Introduction to Poetry and Song. Yale University Press.

Beaudoin, Richard. 2024. Sounds as They Are: The Unwritten Music in Classical Recordings. Oxford University Press.

Bertinetto, Pier Marco. 1989. “Reflections on the Dichotomy ‘Stress’ vs. ‘Syllable-Timing.’” Revue de phonétique appliquée 91 (93): 99–130.

—————. 2021. “Rhythm in the Romance Languages.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.431.

Brown, Helen. 2013. “Katy Perry, Prism, review.” The Telegraph, October 17, 2013. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rockandpopreviews/10386191/Katy-Perry-Prism-review.html.

Burzio, Luigi. 1994. Principles of English Stress. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511519741.

—————. 2007. “Phonology and Phonetics of English Stress and Vowel Reduction.” Language Sciences 29 (2-3): 154–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2006.12.019.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2004. “The Classical Cadence: Conceptions and Misconceptions.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 57 (1), 51–118.