Post-Recapitulatory Organization in Beethoven’s Early Sonata-Rondo Finales

Joan Huguet

KEYWORDS: Formenlehre, Classical, Beethoven, finale, sonata-rondo, coda

ABSTRACT: This paper proposes a new model of closure for Beethoven’s sonata-rondo finales that describes the wide variety of ways in which sonata and rondo elements can interact to create unexpected harmonic and formal possibilities after the recapitulation. The paper first considers what models of sonata form can and cannot tell us about sonata-rondo closure and develops a typology of constituent formal functions for sonata-rondo post-recapitulatory space. It then outlines how these formal functions combine to create a variety of post-recapitulatory prototypes in Beethoven’s early-period sonata rondos. Finally, it considers the analytical benefits of distinguishing between sonata and sonata-rondo modes of closure.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.3.2

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[1] Modern Formenlehre theories have long held that a coda functions in exactly the same way regardless of a piece’s overall form. For example, while scholars have extensively detailed numerous divergences between Classical sonata and sonata-rondo form initiating functions,(1) the different structural and rhetorical strategies for concluding these two formal types remain unexplored. These variances often occur due to sonata-rondo form’s inherently hybrid nature, as it is neither a purely sectional rondo nor a fully integrated sonata. Indeed, the tension between a sonata rondo’s oft-conflicting sonata and rondo elements gives rise to a unique compositional space in which lightness balances weightiness, sectional closure counteracts an incessant drive forward, and developmental processes exist alongside the inevitable return, again and again, of the refrain (Huguet 2015, 188). While this tension is inherent to all Classical rondo-form finale movements, it is often foregrounded in Beethoven’s early sonata-rondo finales, in which the relatively uncomplicated rhetoric of the Classical sectional rondo starkly contrasts with the goal-directed integration of Beethoven’s sonata form.(2) In this study, I will propose a new model of closure for Beethoven’s sonata-rondo finales, one that takes into account the wide variety of ways in which sonata and rondo elements can interact to create unexpected harmonic and formal possibilities after a sonata-rondo movement’s recapitulation.

[2] Following a brief review of Classical sonata-rondo form, I will reflect on what existing research on Beethoven’s coda practices and the new Formenlehre can tell us about sonata-rondo closure. I next develop a typology of constituent formal functions for sonata-rondo post-recapitulatory space and outline how these formal functions combine to create a variety of post-recapitulatory prototypes in Beethoven’s early-period sonata rondos.(3) Finally, I consider the analytical benefits of distinguishing between sonata and sonata-rondo modes of closure in this repertoire.

Analyzing Beethoven’s Sonata-Rondo Form

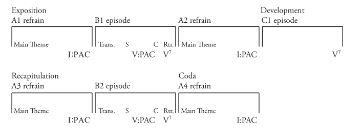

Example 1. Sonata-rondo form thematic structure

(click to enlarge)

[3] Sonata-rondo form is the most common finale type in early Beethoven.(4) It consists of a seven-part thematic structure, as shown in Example 1. Like all rondos, sonata-rondo form’s defining feature is the alternation of a thematic refrain (labeled A), most often in the global tonic key, with harmonically and thematically contrasting episodes (labeled B and C).(5) In addition to these thematic labels, we can apply form-functional designations such as exposition, main theme, transition, subordinate theme, development, and recapitulation to describe the sonata aspects of this genre. Both thematic labels and form-functional labels are necessary in order to capture the hybrid nature of sonata-rondo form (Caplin 1998, 235).

[4] Scholars have noted that sonata-rondo form differs not only in formal structure but also in character from its first-movement sonata-form counterpart. William Caplin, for example, notes that “rondos are normally not as dramatic in emotional expression: they tend to be light and more relaxed in character” (2013, 653). Charles Rosen further categorizes the differences between sonata-rondo form and first-movement sonata form, stating that the former most often features a relatively relaxed level of harmonic tension, a conventional, square theme, and clear phrase rhythm (1988, 123). In a more recent study, Jonathan De Souza, Adam Roy, and Andrew Goldman verify through both corpus study and a cognitive experiment that listeners can perceive the difference between sonata and rondo forms, concluding that they “vary in their long-range juxtaposition of thematic and tonal areas, but also

[5] Critically, Beethoven’s early sonata rondos serve as a significant point in the form’s evolution, driving it to become more integrated and sonata-like. Michael Talbot writes, “From Beethoven onwards, most rondos employed in prestigious genres have been sonata rondos. Their sonata-like features

Analyzing Beethoven’s Codas

[6] Research on Beethoven’s sonata-form codas provides a valuable starting point for our discussion of sonata-rondo closure. This topic proved a fruitful line of inquiry for many prominent scholars of the late twentieth century, including Joseph Kerman, Charles Rosen, Robert G. Hopkins, and Nicholas Marston. Kerman (1982) launched a dialogue on Beethoven’s codas, claiming that prior research on Beethoven’s sonatas inadequately treated this formal unit. According to Kerman, the coda differs from other sonata-form units in that it does not refer to a [formal] function, but merely to the unit’s position within the work. Indeed, much of the difficulty in analyzing codas arises precisely because this one unit can function in such a variety of ways (Kerman 1982, 141). In addition, Kerman describes the compensatory role that Beethoven’s codas often play, writing:

Again and again there seems to be some kind of instability, discontinuity, or thrust in the first theme which is removed in the coda. The aberration may be linear, harmonic, rhythmic, registral, or textural, but in any case the coda has a function over and above that of ‘saturating the ear with the tonic chord,’ in Rosen’s phrase. [Rosen 1971/1997, 394]. In addition to this harmonic function, it has a thematic function that can be described or, rather, suggested by words such as ‘normalization’, ‘resolution’, ‘expansion’, ‘release’, ‘completion’, and ‘fulfillment’ (Kerman 1982, 149).

Kerman’s concept of coda compensatory functions has been hugely influential, permeating all subsequent studies of closure in Beethoven. Here it leads naturally to an essential question to be kept in mind throughout subsequent discussion and to which I will return in this article’s conclusion: “Is it equally applicable to the composer’s sonata-rondo codas?”

[7] Beethoven’s position at the boundary of Classical and Romantic practices further complicates discussion of his codas. Rosen views the Beethovenian coda as firmly rooted in the style of Haydn and Mozart, adding weight and balance to the conclusion of a piece by mirroring the framing function of the slow introduction (1988, 304).(6) From there, Rosen expands upon Kerman’s concept of coda compensatory functions as an explicitly Classical device, suggesting that “it is not so much that the coda tidies up after the main structure, but that it realizes the remaining dynamic potential” (1988, 324). Hopkins, in contrast, suggests that viewing the nineteenth-century coda as equivalent to its eighteenth-century antecedents is overly simplistic. For him, Beethoven’s codas move beyond merely functioning as an afterthought, instead becoming an integral part of the movement’s overall structure (Hopkins 1988, 393). In noting how the coda became a required element of sonata form for Beethoven and subsequent nineteenth-century composers, Hopkins furthermore suggests that any structural theory of codas must be evolutionary in nature (1988, 393).

[8] The last author in the above list, Marston, differs from Kerman, Rosen, and Hopkins in that he does not attempt to theorize Beethoven’s codas, but rather offers a more general discussion of closure over the course of Beethoven’s multi-movement works. He writes:

In short, one might speak of a progressive easing of the demands made on the late eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century listener. . . Beethoven too ascribed to this aesthetic; yet he seems from an early age to have been interested also in subverting it, by writing finales that are not merely equal in weight to their respective first movements, but which actually overpower them (Marston 2000, 92).

While Marston acknowledges that Beethoven often declines to front-weight his multi-movement pieces in accordance with typical Classical practice, he does not explore how this shift plays out in the composer’s sonata-rondo finales.

[9] Taken collectively, these four views provide valuable context for our discussion of Beethoven’s means of creating closure in his sonata-rondo finales. All of them describe a multivalent process in which harmonic, thematic/formal, and rhetorical criteria combine to develop a strong sense of conclusion, a process which will be equally important to post-recapitulatory space as it is to the sonata-rondo coda.(7) They further suggest that a dialogic approach—in which Beethoven’s means of achieving closure simultaneously rely upon and subvert Classical norms—is essential to understanding the evolution of the coda.(8) Finally, Kerman’s distinction between a position and a function opens the door to a more nuanced understanding of how a variety of formal functions, not merely ending functions, may contribute to the complexity of Beethoven’s codas.

[10] And yet at the same time, their scope is limited in significant ways. First and most obviously, this scholarship largely predates the important developments of new Formenlehre at the turn of the twenty-first century, which will provide a detailed analytical framework for Beethoven’s formal structures. Second, with the exception of Marston’s brief comments on multi-movement closure, these authors almost exclusively discuss first-movement sonata-form codas, a common approach in Beethoven studies as well as in Formenlehre more generally.(9) Finally, they primarily are based upon Beethoven’s middle-period codas. Kerman explicitly defines this constraint, suggesting that expansive codas begin to become a defining feature of Beethoven’s music around the composition of the Symphony No. 2 in D Major, op. 36 (1982, 149). In this study I will take the opposite tack: calling upon the tools of the new Formenlehre, I illustrate how Beethoven’s early-period finales develop a complex and flexible means for closing sonata-rondo form. Having established this framing strategy, we may now consider what these theories can tell us about sonata-rondo closure.

New Formenlehre and the Sonata-Rondo Coda

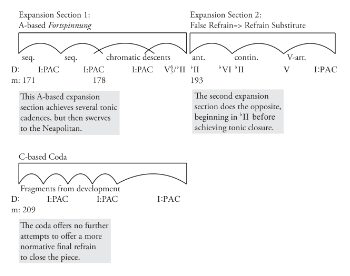

[11] William Caplin’s Classical Form and James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s Elements of Sonata Theory define the Classical coda in similar ways. Caplin states that the coda is “an optional section that follows, and is fully distinct from, the recapitulation” (1998, 179). Likewise, Hepokoski and Darcy describe the unit as an “add-on,” outside of the sonata form proper (2006, 281). Both theories suggest that the coda should be identified through correspondence bars, that is, by comparing the recapitulation to the exposition and determining the point at which the former deviates from the latter (Caplin 1998, 181; Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 281). Both base their definition of the term “coda” upon two assumptions: first, that the recapitulation is the final required unit of sonata form; and second, that successive events cannot negate the cadential closure achieved by the sonata recapitulation.(10) The first assumption clearly does not apply to sonata-rondo form as modeled in Example 1, as the B2 episode must be followed by the A4 refrain. The second, though, merits further exploration: does the I:PAC achieved by the recapitulation’s B2 episode establish closure for a sonata-rondo form as it does for a sonata form? I suggest that it is not the recapitulation that closes a sonata-rondo form, but the final refrain. In fact, it is precisely this deferral of closure that gives rise to the wide variety of formal and harmonic behavior that we find after the recapitulation in Beethoven’s sonata-rondo finales.

Conflicting Formal Functions and the Sonata-Rondo Coda

[12] To better understand how a sonata-rondo movement achieves closure, we must grapple with the fact that, unlike in the typical sonata-form coda, the material after a sonata-rondo recapitulation contains units with conflicting formal functions.(11) As is the case for every rondo refrain, A4 can serve as a new beginning, often providing the periodic rush of familiarity and stability that defines all rondo forms.(12) Coda material, on the other hand, fulfills an after-the-end function, celebrating closure that has already been achieved.(13) Further complicating the issue is the variety of temporal relationships possible between the A4 refrain and other post-recapitulatory material. The A4 refrain can appear immediately after the B2 episode,(14) between two non-refrain units, or after an extended coda-like unit. There may be multiple literal reprises of it, or in some cases none at all. In short, simply locating the final refrain can be an analytical challenge in and of itself.(15)

[13] Caplin acknowledges the problematic nature of a sonata rondo’s concluding section, writing, “It would seem, then, that there is no consistent relation between the beginning of the coda and the beginning of the final refrain. For that reason, it is perhaps best to say that the former encompasses the latter” (1998, 239). Such a view has the benefit of establishing a consistent location for the beginning of the sonata-rondo coda and highlighting the parallelism between the sonata recapitulation and the sonata-rondo recapitulation. However, it does so at the expense of having a consistent definition for the term coda: what once was a strictly optional function in Caplin’s sonata form now becomes a required element of his sonata-rondo model.

Post-Recapitulatory Formal Functions

Example 2. Three post-recapitulatory formal functions

(click to enlarge)

[14] The points made in the preceding discussion frame our present one: is it possible to better capture the wide variety of form-functional possibilities created by the sonata rondo’s complex juxtaposition of rondo and sonata elements in Beethoven’s finales? By way of answer, I propose that all of the material following the B2 episode of a sonata rondo comprises the movement’s post-recapitulatory space. Accordingly, post-recapitulatory space as I define it is not a formal function, but a location that can contain multiple formal units. Post-recapitulatory space can contain three types of form-functional units: expansion sections, refrains, and codas. Example 2 illustrates one possible arrangement of these units.

Any material preceding the tonic refrain, thus delaying the onset of the A4 refrain and by extension the formal closure of the movement, is an expansion section. In this model, the A4 refrain is a distinct unit that achieves closure for the sonata-rondo form. The term coda, in turn, is reserved for any material following a closed A4 refrain. As we will see in the analyses below, any of the three constituent units of post-recapitulatory space may be loosened, expanded, or even omitted, thereby creating a wide variety of possible formal and harmonic structures. Let’s examine each of these three functions in more detail.

Expansion Section

[15] The function of the post-recapitulatory expansion section is to delay the arrival of the final refrain and, consequently, the closure of the movement and the piece as a whole. Expansion space is defined as a relatively loose-knit section—i.e., exhibiting techniques similar to those often found in transitions or developments—whose function is distinct from that of a closed tonic refrain or a coda. In contrast to those latter two formal functions, which provide symmetry and stability, expansion sections are often highly unstable, creating harmonic and formal tension at the very point when the listener expects the sonata-rondo form to reach a tidy close. In many of Beethoven’s sonata rondos, expansion sections are responsible for the immense length of post-recapitulatory space, thus performing a similar function as the discursive coda in his sonata-form works.(16)

[16] Expansion sections may return to any material featured earlier in the movement, whether refrain or episode; as a result, they are often difficult to categorize in terms of the letter-based labeling system used to describe the rondo form proper. Most expansion sections, however, share several characteristic elements. Regardless of their thematic material, they typically commence with a clear initiating function, characterized by a thematic or harmonic restart, which may be either in the global tonic or in another key.(17) They are form-functionally loose in relation to both the refrain and any non-developmental episodes, often featuring tonicizations, sequences, or extensive sections of Fortspinnung. Most notably, expansion sections typically conclude with a half cadence or a dominant arrival, which can lead either into the A4 refrain or another expansion section.(18) The effect of their doing so echoes the long, rhetorically emphasized dominant retransitions that conclude Beethoven’s sonata-rondo episodes and build anticipation for the refrain’s return.

A4 Refrain

[17] The A4 refrain is widely acknowledged as an essential component of sonata-rondo form. Typically, it will retain the tight-knit nature of the initial refrain to a certain extent; however, in Beethoven’s practice, some measure of form-functional loosening often occurs.(19) Such modifications can be as simple as a change in accompanimental texture, cadential extensions to dramatize the point of closure, or the omission of a small ternary refrain’s digression and reprise. More complex modifications are also possible, including internal tonicizations or modulations, as long as the refrain both begins and ends in the global tonic.

Coda

[18] In most cases, a tight-knit and tonally closed A4 refrain is required before the piece can enter sonata-rondo coda space.(20) The sonata-rondo coda, like the expansion sections that lead to the refrain, evinces a variety of formal patterns. Its harmonic behavior, in contrast, is somewhat more restricted in ways that reinforce the closure already established by A4. For example, it cannot present a harmonically open version of refrain material—i.e., by concluding such material with a dominant arrival instead of an authentic cadence—without reopening the rondo form. In addition, it cannot reach an authentic cadence in any key other than the global tonic, regardless of the thematic material being employed.(21) These restrictions serve to align the concept of the sonata-rondo coda with its sonata-form counterpart, limiting it to the after-the-end function more generally associated with the term.

Post-Recapitulatory Space Prototypes

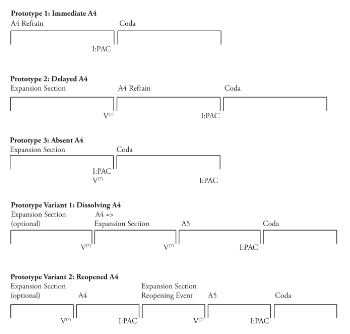

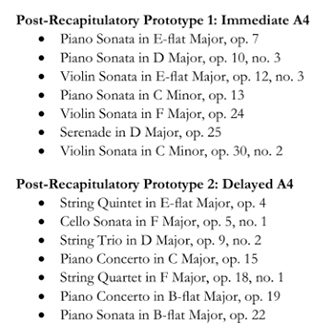

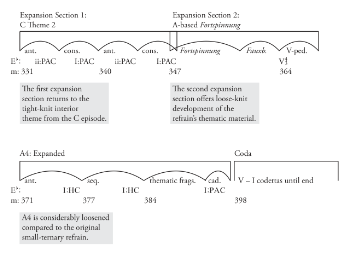

[19] In Beethoven’s early sonata-rondo finales, the three formal functions described above combine to create three prototypes and two variants for post-recapitulatory space. Each is defined (named) according to the location and behavior of its A4 refrain as follows: there is the immediate A4, the delayed A4, the absent A4, the dissolving A4, and the reopened A4. Example 3 provides schemata of all five prototypes and variants, and Example 4 categorizes Beethoven’s early sonata-rondo finales in accordance with this system.(22) Within each of these five models, varying degrees of form-functional loosening may expand or reopen any of its formal components, resulting in a wide range of formal and harmonic possibilities for each individual post-recapitulatory space.

Example 3. Post-recapitulatory space prototypes and variants (click to enlarge) | Example 4. Early Beethoven sonata-rondo finales by post-recapitulatory prototype (click to enlarge) |

Post-Recapitulatory Prototype 1: Immediate A4

[20] Many textbook definitions of sonata-rondo form present only a single prototype for the form’s conclusion: after the B2 episode, a complete A4 closes the rondo form, which is immediately followed by an optional coda (Green 1979, 163; Berry 1986, 213; Tovey 1935). Caplin correctly problematizes this limited model of sonata-rondo closure, suggesting that it inadequately describes the range of possibilities for this formal unit (1998, 239). Within the early Beethoven repertoire, however, this model successfully accounts for a number of post-recapitulatory structures. In the present study, I will refer to it as the immediate A4 prototype.

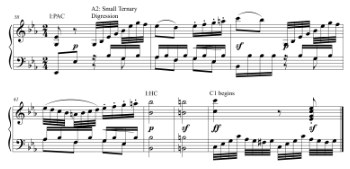

Example 5. Piano Sonata in D Major, op. 10, no. 3, iv, mm. 84–113

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[21] One notable example is the finale movement of the Piano Sonata in D Major, op. 10, no. 3 (see Example 5). This “textbook” example of sonata-rondo closure features a complete A4 refrain (mm. 84–92) concluding with a tonic PAC. This arrival is followed by an A-based coda that first expands upon the refrain’s motivic content and then offers an alternative, sequential continuation for the refrain’s basic idea before reaching another I:PAC (m. 106).(23) Because the music has already achieved a complete, tonally closed A4 refrain in m. 92, this second A-based unit serves an after-the-end function, playfully developing the refrain’s ideas without harmonically reopening the sonata-rondo form.

Example 6. Form diagram of post-recapitulatory space: Piano Sonata in E-flat Major, op. 7, iv

(click to enlarge)

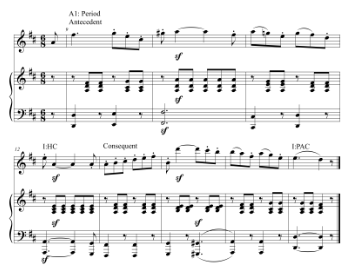

[22] The finale of the Piano Sonata in

Example 7. Piano Sonata in E-flat Major, op. 7, iv, mm. 150–66 (click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen) | Example 8. Piano Sonata in E-flat Major, op. 7, iv, mm. 58–64 (click to enlarge and listen) |

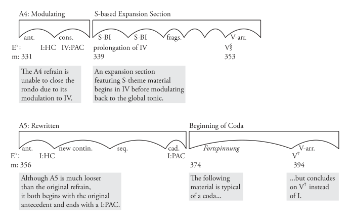

Post-Recapitulatory Prototype 2: Delayed A4

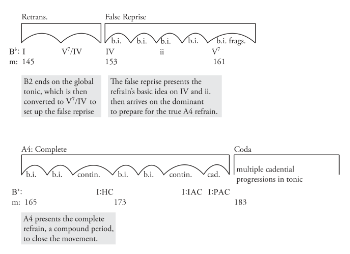

[23] The delayed A4 post-recapitulatory prototype employs all three of the post-recapitulatory functions described above, postponing the arrival of the A4 refrain with one or more expansion sections. The finale of the Piano Sonata in

Example 9. Form diagram of post-recapitulatory space: Piano Sonata in B-flat Major, op. 22, iv (click to enlarge) | Example 10. Piano Sonata in B-flat Major, op. 22, iv, mm. 144–68 (click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen) |

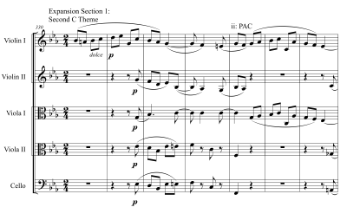

Example 11. Form diagram of post-recapitulatory space: String Quintet in E-flat Major, op. 4, iv

(click to enlarge)

Example 12. String Quintet in E-flat Major, op. 4, iv, mm. 330–53

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

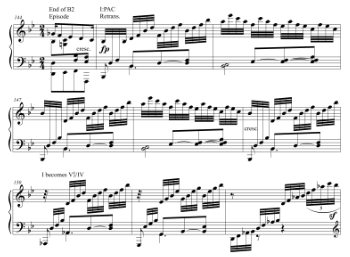

[24] The finale of the String Quintet in

Post-Recapitulatory Prototype 3: Absent A4

Example 13. Piano Sonata in A-flat Major, op. 26, iv, mm. 148–69

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

Example 14. Form diagram of post-recapitulatory space: Violin Sonata in D Major, op. 12, no. 1, iii

(click to enlarge)

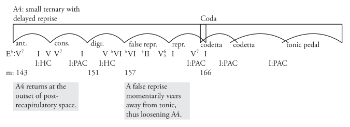

[25] In the third post-recapitulatory prototype, the A4 refrain is either harmonically and/or formally unstable, or absent altogether. Remarkably, this possibility is not mentioned in previous models of sonata-rondo form, all of which describe a stable A4 refrain as required. Nevertheless, the finale of the Piano Sonata in

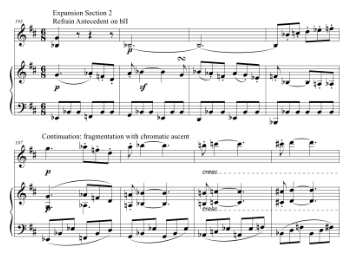

[26] The finale of the Violin Sonata in D Major, op. 12, no. 1 offers a more complex example of this prototype, demonstrating that expansive post-recapitulatory space development is possible even in the absence of a final refrain (see Example 14). In this movement, three different formal units follow the B2 unit: an expansion section, a second expansion section that achieves closure under unusual circumstances, and a coda. In the first expansion section (mm. 171–92), three sequences of A-based Fortspinnung follow B2, achieving authentic cadential closure in tonic several times. A chromatic descent then leads not to the global dominant, the expected conclusion of an A-based expansion section, but instead to V/

Example 15. Violin Sonata in D Major, op. 12, no. 1, iii, mm. 193–214 (click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen) | Example 16. Violin Sonata in D Major, op. 12, no. 1, iii, mm. 9–16 (click to enlarge and listen) |

Post-Recapitulatory Variant Prototype 1: Dissolving A4

Example 17. Form diagram of post-recapitulatory Space: String Trio in E-flat Major, op. 3, vi

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[27] The dissolving A4 post-recapitulatory variant—which is rare in the early Beethoven repertoire as attested to in Example 4—offers a fusion of the immediate and dissolving A4 prototypes. The defining characteristic of this prototype is that an initially normative refrain modulates or is otherwise unable to achieve closure, converting into an expansion section. An example of this occurs in the finale of the String Trio in

Example 18. String Trio in E-flat Major, op. 3, vi, mm. 372–457

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[28] This movement’s coda (see Example 18) merits further consideration, as it is considerably more complex than the simple cadential confirmations exhibited in previous examples. After the PAC that closes the A5 refrain (m. 373), a typical A-based coda begins, alternating between tonic and dominant harmonies. This coda unit does not lead to the end of the movement, but rather to a dominant arrival and a redundant reprise of the refrain’s initial period, concluding with an additional tonic PAC (m. 409).(29) After this, a new sentential theme that is loosely based on the texture and rhetoric of the movement’s B episode leads to yet another tonic PAC in m. 423; a subsequent repetition of this theme then dissolves into a dominant arrival (mm. 439–42). The analyst at this point might wonder: does this new sentential theme reopen the rondo form, thus creating a nine-part form? To answer this question, we may consult the standard accounts of rondo form, which universally hold that episodes must be in non-tonic keys with the exception of recapitulatory episodes in sonata-rondo forms. As neither is the case here, we can consider this to be a rare example of a new coda theme in a Beethoven sonata-rondo. Following this coda theme, fragments of the refrain’s basic idea return once more (mm. 443–52), offering the seemingly absurd prospect of an A7 refrain, after which the movement abruptly ends.

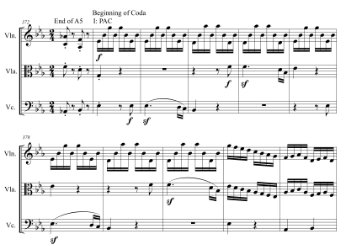

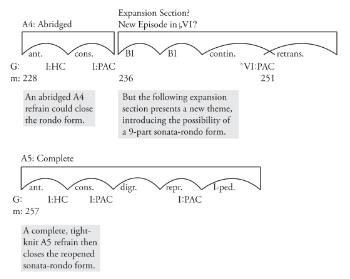

Post-Recapitulatory Variant Prototype 2: Reopened A4

Example 19. Form diagram of post-recapitulatory space: Cello Sonata in G Minor, op. 5, no. 2, ii

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

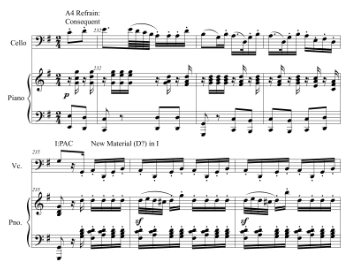

[29] The reopened A4 post-recapitulatory variant is similar to the dissolving A4 variant in that it becomes necessary for an A5 refrain to close the piece. It differs, however, in that it does not problematize the A4 refrain itself, but instead uses the ensuing musical material to reopen the closure that it just achieved. The reopened A4 variant, which is similarly rare in the early Beethoven repertoire (two instances, see Example 4), might productively be considered as a combination of the immediate and delayed A4 prototypes. In the finale of the Cello Sonata in G Minor, op. 5, no. 2 (Example 19), an off-tonic, cadentially confirmed coda theme reopens the previously closed structure and suggests the possibility of a nine-part sonata-rondo.(30)

Example 20. Cello Sonata in G Minor, op. 5, no. 2, ii, mm. 232–51

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

[30] After the recapitulation, the B2 episode gives way to an abridged statement of the refrain (mm. 228–35; see Example 20) that closes with a perfect authentic cadence in tonic. At this point, the piece has attained tonal closure at the end of both B2 and A4, and thus could readily conclude as a highly conventional sonata-rondo form. Instead, a new thematic unit follows (mm. 236–51; also shown in Example 19), which modulates to the remote key area of

[31] Once more we might entertain the possibility of analyzing this movement as a nine-part rondo. To do so, we would have to hear the material in

Conclusion

[32] Although the sonata-rondo arose initially as a hybrid of sectional rondo form and sonata form, its development as Beethoven’s default finale form led to characteristics that would register as distinctly out of the ordinary in either of its generating formal types. My post-recapitulatory space model thus suggests that our paradigm for evaluating Beethoven’s sonata-rondo closure strategies should rely on a distinct set of form-functional criteria as opposed to mechanically adopting sonata-form models. To appreciate the benefits of doing so more fully, let us return to Kerman’s characterization of Beethoven’s codas as compensatory zones of resolution. This view may indeed apply to Beethoven’s sonata-form codas, but does it accurately describe the dynamic arc that a sonata-rondo’s post-recapitulatory space brings to a close? Not at all. Instead of normalizing the earlier material of the piece, we have seen that post-recapitulatory space very often problematizes it, delaying and then formally loosening the refrain’s material to the point that the defining symmetry of rondo form is called into question. Far from confirming that sonata and sonata-rondo forms achieve closure through similar means, an examination of Beethoven’s sonata-rondo finales brings to light the unexpected, asymmetrical, and forward-driven ways in which this seemingly square and derivative form evolved in these works.

Joan Huguet

Knox College

2 E. South Street

Galesburg, IL 61401

joanchuguet@gmail.com

Works Cited

Agawu, V. Kofi. 1987. “Concepts of Closure and Chopin’s Opus 28.” Music Theory Spectrum 9 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/746116.

Berry, Wallace. 1986. Form in Music, 2nd ed. Prentice-Hall.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195104806.001.0001.

—————. 2009. “What are Formal Functions?” In Musical Form, Forms, and Formenlehre: Three Methodological Reflections, ed. Pieter Bergé, 21–40. Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qf01v.5.

—————. 2013. Analyzing Classical Form: An Approach for the Classroom. Oxford University Press.

Cole, Malcolm. 1964. “The Development of the Instrumental Rondo Finale from 1750–1800.” PhD diss., Princeton University.

De Souza, Jonathan, Adam Roy, and Andrew Goldman. 2020. “Classical Rondos and Sonatas as Stylistic Categories.” Music Perception 37 (5): 373–91. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2020.37.5.373.

Drabkin, William. 1994. “Early Beethoven.” In Eighteenth-Century Keyboard Music, ed. Robert L. Marshall, 394–424. Schirmer Books.

Galand, Joel. 1990. “Rondo-Form Problems in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Instrumental Music, with Reference to the Application of Schenker’s Form Theory in Historical Context.” PhD diss., Yale University.

—————. 1995. “Form, Genre, and Style in the Eighteenth-Century Rondo.” Music Theory Spectrum 17 (1): 27–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/745763.

Gosman, Alan. 2024. “Take It Away: How Shortened and Missing Sections Energize Rondo Forms.” In Perspectives on Contemporary Music Theory: Essays in Honor of Kevin Korsyn, ed. Bryan Parkhurst and Jeffrey Swinkin, 147–61. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003357797-8.

Green, Douglass. 1979. Form in Tonal Music, 2nd ed. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Hepokoski, James. 2002. “Back and Forth from Egmont: Beethoven, Mozart, and the Non-Resolving Recapitulation.” 19th-Century Music 25 (2–3): 127–53. https://doi.org/10.1525/ncm.2001.25.2-3.127.

—————.2009. “Sonata Theory and Dialogic Form.” In Musical Form, Forms, and Formenlehre: Three Methodological Reflections, ed. Pieter Bergé, 71–89. Leuven University Press.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195146400.001.0001.

Hopkins, Robert G. 1988. “When a Coda is More than a Coda: Reflections on Beethoven.” In Explorations in Music, the Arts, and Ideas: Essays in Honor of Leonard B. Meyer, ed. Eugene Narmour and Ruth A. Solie, 393–410. Pendragon Press.

Huguet, Joan. 2015. “Formal Functions and Voice-Leading Structures in Beethoven’s Early Sonata-Rondo Finales.” PhD diss., University of Rochester, Eastman School of Music.

—————. 2016. “Thematic Redundancy, Registral Connections, and Formal Expectations in the Finale of Beethoven’s Op. 14/1.” Music Theory and Analysis 3 (2): 197–208. https://doi.org/10.11116/MTA.3.2.4.

Hunt, Graham. 2014. “‘How Much is Enough?’ Structural and Formal Ramifications of the Abbreviated Second A Section in Rondo Finales from Haydn to Brahms.” Journal of Schenkerian Studies 8: 1–48.

Kerman, Joseph. 1982. “Notes on Beethoven’s Codas.” In Beethoven Studies 3, ed. Alan Tyson, 141–59.

Kinderman, William. 1995. Beethoven. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198165217.001.0001.

Laitz, Steven G. and Michael R. Callahan. 2023. The Complete Musician, 5th ed. Oxford University Press.

Marston, Nicholas. 2000. “‘The Sense of an Ending: Goal-Directedness in Beethoven’s Music.” In The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven, ed. Glenn Stanley, 84–101. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL9780521580748.007.

Rosen, Charles. 1988. Sonata Forms. Rev. ed. W. W. Norton.

—————. 1997. The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. Exp. ed. W. W. Norton.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. 2011. In the Process of Becoming: Analytical and Philosophical Perspectives on Form in Early Nineteenth-Century Music. Oxford University Press.

Segall, Christopher. 2018. “Rondo=>Sonata Conversion: The Finale of Beethoven’s String Quartet in C Minor, Op. 18, No. 4.” Music Theory and Analysis 5 (2): 203–15. https://doi.org/10.11116/MTA.5.2.5.

Talbot, Michael. 2001. The Finale in Western Instrumental Music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198166955.001.0001.

Tovey, Donald Francis. 1935. A Companion to Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas. Associated Board.

Yudkin, Jeremy. 2020. From Silence to Sound: Beethoven’s Beginnings. The Boydell Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787446885.

Discography

Discography

Beethoven, Ludwig van. 1987. Beethoven: The Complete Sonatas for Cello & Piano. Yo Yo Ma (cello); Emanuel Ax (piano). Sony Classical 2010737.

—————. 1997. Beethoven Complete Edition, vol. 10: String Trios. Anne-Sophie Mutter (violin); Bruno Guiranna (viola); Mstislav Rostropovich (cello). Deutsche Grammophon 28945375724.

—————. 1998. Beethoven: The Violin Sonatas. Anne-Sophie Mutter (violin); Lambert Orkis (piano). Recorded 1998. Deutsche Grammophon 28945761923.

—————. 2006. Beethoven: String Quintets (Complete). Zurich String Quintet. Recorded in 2004. Brilliant Classics 92857.

—————. 2010. Beethoven: The Complete Piano Sonatas. Alfred Brendel (piano). Recorded in 1970–77. Decca/Verve Label Group B0043UOQ26.

Footnotes

1. Both Caplin 1998 (237) and Hepokoski and Darcy 2006 (405) describe the rondo theme as the most conventional unit of the form. Rondo refrains are often highly repetitive and symmetrical in structure, favoring such theme types as the compound period and the small ternary. Additionally, unlike sonata-form main themes, rondo themes must close with a I:PAC. Cole 1964, Talbot 2001, and Galand 1990 and 1995 all describe the straightforward structure of the rondo theme as fundamental to the character of rondo form. On the other hand, characteristics of the non-refrain material in rondo forms have not been described in similar detail.

Return to text

2. William Drabkin writes, “Upon his arrival in Vienna, the young Beethoven began to cultivate a certain type of piano sonata that extended its utility beyond the drawing room and put it on the time-scale of the symphony, thus preparing the genre ultimately for the concert hall” (1994, 401–2). Elaborating and expanding sonata-rondo form would have played an important role in this process, particularly given its most common use as a finale form.

Return to text

3. Beethoven’s early-period pieces have been categorized in a myriad of ways in the musicological literature. While acknowledging that such boundaries are never completely satisfactory, I have chosen to focus on the sonata-rondo finales of opp. 1–30 for the present study. While the Bonn-era and other WoO works offer a number of sonata-rondo movements, they are largely shorter and more sectional than even the earliest works in opp. 1–30. After the op. 30 Violin Sonatas, Beethoven’s sonata rondo output slowed drastically. The rondos and sonata rondos of the middle and late periods, marked by their relative rarity, thus merit their own dedicated study.

Return to text

4. Other rondo finale types include five-part rondo, nine-part sectional rondo, the ABACBA rondo variant, seven-part symmetrical rondo, and seven-part chain rondo. For a complete list of these finale types in the early Beethoven repertoire, see Huguet 2015 (19). More recently, Segall 2018 has further expanded the possibilities for analyzing Beethoven’s finales, suggesting that the finale of the String Quartet in C Minor, op. 18, no. 4 can be interpreted as rondo=>sonata conversion and that the finale of the Violin Sonata in A Minor, op. 23 can conversely be interpreted as sonata=> rondo conversion. Here, Segall invokes Schmalfeldt’s concept of becoming, “the special case whereby the formal function initially suggested by a musical idea, phrase, or section invites retrospective reinterpretation within the larger formal context (Schmalfeldt 2011, 9).

Return to text

5. To distinguish between the individual refrains and episodes of a sonata-rondo movement, I employ both letters and numbers, following Laitz and Callahan 2023 (585). In this system, the first iteration of the refrain is referred to as A1, the second as A2, and so forth. This labeling system allows me to efficiently distinguish between different appearances of the same thematic material—for example, when discussing how the recapitulation’s B2 episode recomposes the B1 material from the exposition.

Return to text

6. Note that this point implicitly confirms what I view as a bias of both musicologists and music theorists towards basing analytical generalizations solely upon first-movement sonata forms. To my knowledge, there are no sonata-rondo movements with integrated slow introductions, yet these works almost always have substantial codas. Within the Beethoven repertoire, however, several finales are preceded by fragmentary or extremely brief slow movements, including those of the String Quartet in

Return to text

7. This approach aligns with that outlined in Agawu 1987, which distinguishes between cadence, closing, and ending in its exploration of the structural and rhetorical means of achieving closure in tonal music.

Return to text

8. The concept of dialogic form is central to Hepokoski and Darcy’s Sonata Theory. In Hepokoski (2009, 71), the author defines dialogic form as “form in dialogue with historically conditioned compositional options.”

Return to text

9. In both Caplin 1998 and Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, for example, rondo and sonata-rondo forms are discussed in a single chapter near the end of each respective monograph.

Return to text

10. This is, of course, assuming that a successful point of essential sonata closure (ESC) occurs in the recapitulation (Hepokoski 2002; Hepokoski and Darcy 2006). In Huguet 2015 (64–69), I consider whether this expectation is as true of sonata-rondo forms as of type 3 sonata forms. In the case of the early Beethoven repertoire, sonata “failure” is much more common we might expect: the ESC is problematic or altogether absent in twelve of the twenty-five sonata-rondo finales that Beethoven wrote in his early period (opp. 1–30).

Return to text

11. Caplin 2009 (23) defines five formal functions: before-the-beginning, beginning, middle, end, and after-the-end. A piece is comprised of multiple levels of nested functions: a functional beginning, for example, contains its own beginning, middle, and ending functions. In Caplin’s theory, the coda is the highest-level after-the-end function.

Return to text

12. Upon closer review, sonata theory’s application of the concept of rotation to sonata-rondo form raises some questions. Hepokoski and Darcy define rotation as follows: “Rotational structures are those that extend through musical space by recycling one or more times—with appropriate alterations and adjustments—a referential thematic pattern established as an ordered succession at the piece’s outset” (2006, 611). With the exception of the recapitulation, the thematic returns in a sonata-rondo do not typically present complete or even partial rotations of the exposition’s thematic layout, but only the refrain. In sonata-rondo form, it is thus the return of the refrain alone—not a succession of themes—that is form-defining.

Return to text

13. Sonata-rondo post-recapitulatory space typically performs this function as well. As a result, post-recapitulatory space deploys many of the same harmonic and rhetorical strategies as a sonata-form coda, including the recollection of main-theme ideas (distinct from the A4 refrain unit), the return of material from the subordinate theme or developmental episodes, the shaping of a new dynamic curve, or introducing other material necessary to bring the movement to a successful close (Caplin 1998, 186–87).

Return to text

14. The B2 episode, by definition, includes any closing and/or retransitional material that also appeared at the conclusion of the B1 episode in the sonata-rondo exposition. The closing material serves an after-the-end function at a lower level of function, reinforcing the closure of the sonata aspect of sonata-rondo form. Retransitional material, if present, can play a significant role in setting up either an A4 refrain or expansion section to begin post-recapitulatory space. In either case, we can employ correspondence bars to identify where, precisely, B2 ends and post-recapitulatory space begins.

Return to text

15. This condition leads me to believe that the final refrain plays a fundamentally different role in the overall trajectory of the piece than the earlier refrains. Indeed, recent scholarship on the sonata rondo suggests that each of the four refrains has a distinct role within the form as a whole; see, for example, Hunt 2014, Huguet 2015 and 2016, and Gosman 2024.

Return to text

16. In some sonata rondos, post-recapitulatory space comprises approximately one-third of the movement’s overall length. This is the case in the Piano Sonata in A Major, op. 2, no. 2; the String Trio in

Return to text

17. False-refrain expansion sections appear in the finales of the String Trio in D Major, Op. 9, no. 2 (

Return to text

18. In this way, expansion sections are similar to transitions and developments, which are also relatively loose-knit formal units that typically end on a structural dominant.

Return to text

19. Gosman 2024 describes how thematic liquidation can serve as a significant strategy for form-functional loosening in Beethoven’s sonata-rondo finales. In his discussion of the finale of the Violin Sonata in

Return to text

20. The absent A4 post-recapitulatory prototype accounts for a notable exception to this norm. We might view the omission of a literal A4 refrain from a sonata-rondo finale as veering away from a sectional rondo model towards a more goal-directed, sonata-like recalling of the refrain.

Return to text

21. This does not, however, mean that that coda cannot tonicize other keys. See, for example, the finale of the Piano Sonata in C Minor, op. 13, in which the coda contains a brief echo of the C episode’s parallel tenths counterpoint in

Return to text

22. This table lists every sonata-rondo finale in opp. 1–30. Pieces not listed here from Beethoven’s early period employ another finale type, most commonly standard sonata form, sectional rondo form, or theme and variations.

Return to text

23. Jeremy Yudkin suggests that Beethoven’s recompositions of this sonata rondo’s refrain serve to disambiguate its initial harmonic (is it in D major or G major?) and metric (does it begin on a downbeat or an upbeat?) ambiguities over the course of the movement (2020, 149–50).

Return to text

24. The A2, A3, and A4 refrains of Beethoven’s sonata rondos often feature a variety of loosening techniques relative to the tight-knit A1 refrain that typically opens the form, including both contraction and expansion. Hunt 2014 provides a study of abbreviated A2 refrains, and Huguet 2015 (30–34; 96–100) discusses the variety of loosening technique possible in the A2, A3, and A4 refrains. For the purposes of determining sonata-rondo closure, expansions of the A4 refrain do not affect its ability to close the form, provided that the refrain concludes with a tonic PAC.

Return to text

25. The String Quintet in

Return to text

26. A PAC does occur much earlier in both the B1 episode (m. 54) and the B2 episode (m. 294), offering unproblematic EEC and ESC closure from the perspective of sonata theory. However, ensuing events drastically loosen the B2 episode in relation to the B1 episode, creating a dramatic propulsion forward into post-recapitulatory space. For more information on the relationship between the exposition and the recapitulation in sonata-rondo form, see Huguet 2015 (67–69).

Return to text

27. Hepokoski and Darcy, for example, describe the retransitions that typically prepare rondo-form refrains as saying “Get ready, dear listener: here it comes again!” (2006, 398).

Return to text

28. The observant reader will have noticed that three of my eight examples are in the key of

Return to text

29. Does the final refrain close in m. 373, or after the second, redundant refrain in m. 409? This depends on whether one hears the A-based material beginning in m. 374 as a coda or as a digression within a rounded binary theme. I have chosen the former on the basis of its tonic-prolongational harmonic content, but both readings are valid. More important is to acknowledge the ways in which this redundancy expands post-recapitulatory space, saturating it with both the tonic harmony and the refrain’s thematic material.

Return to text

30. Another exploration of the idea of a nine-part sonata rondo (ABACADABA) occurs in the finale of the Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 23. In this piece, however, the B2 episode concludes with a i:HC instead of a i:PAC, avoiding essential sonata closure. After this surprising moment, the movement then cycles through fragmentary versions of the C and D episodes before the final A5 refrain. We therefore must ask whether this is an unusual nine-part sonata rondo in which the final episode does not achieve closure, or a seven-part chain rondo in which an expansion section reopens A4 with loosened versions of B, C, and D in succession, thus necessitating A5.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Amy King, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

5125