Ernst Friedrich Richter and the Birth of Modern Music Theory Pedagogy*

Bjørnar Utne-Reitan

KEYWORDS: music theory pedagogy, Roman numeral analysis, history of music theory, music theory in the nineteenth century, Leipzig Conservatory, Ernst Friedrich Richter

ABSTRACT: This article provides a detailed discussion of the pedagogy and legacy of Ernst Friedrich Richter (1808–79). A theory teacher at the Leipzig Conservatory since its founding in 1843, Richter is most famous for authoring one of the most enduring harmony manuals—the Lehrbuch der Harmonie (1853)—which, among other things, was instrumental in popularizing the use of Roman numeral analysis in harmony pedagogy. Gaining a hegemonic position in the Western music theory discourse of the late nineteenth century, he played a key role in shaping the common practice of modern music theory pedagogy. Richter’s legacy has been tainted by critiques from several later theorists. Applying a Foucauldian discourse-theoretical lens, this article attempts to look beyond this historically negative assessment by asking what enabled Richter’s work to become so influential. The article is structured in six sections. Following the introduction and a brief overview of E. F. Richter’s life and works, two sections discuss what characterizes “Richterian” pedagogy. As source material, these sections draw on Richter’s writings as well as the exercises of one of his most famous students, Edvard Grieg (1843–1907). The last section before the conclusion investigates Richter’s legacy, considering both his initial broad international success and later critiques of his influence on modern music theory pedagogy.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.3.7

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

[1.1] Ernst Friedrich Richter (1808–79) was arguably the single most influential Western music theorist during the second half of the nineteenth century. A theory teacher at the famed Leipzig Conservatory, his Lehrbuch der Harmonie (1853) became one of the most enduring and frequently translated harmony textbooks in history, and it remained in continuous print for a century (Damschroder and Williams 1990, 266–67; see also Perone 1997, 129–30). Despite (or perhaps because of) this success, Richter and his influence on modern theory pedagogy have been criticized by subsequent prominent theorists, tainting his legacy in the history of music theory. Attempting to look beyond this negative reception, I propose that a broader and more nuanced view of Richter’s pedagogy is essential to understanding not only the field of music theory in the late nineteenth century and beyond, but also the historical construction of modern music theory pedagogy.

[1.2] Despite his popularity, Richter has received comparatively limited scholarly attention. Although he is often mentioned as an influential textbook author in the now extensive literature on nineteenth-century music theory,(1) comprehensive research on Richter himself and the broad international success of his works remains scarce.(2) In The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, Richter is described as “perhaps the most internationally influential harmony and counterpoint teacher of the nineteenth century” (Bent 2002, 594), but a thorough discussion of his pedagogy is not included in the volume. One possible reason for the scholarly neglect of Richter is that there long has been a preference for studying what Thomas Christensen (2015, 210–11) calls “a canon of monumental texts” in the history of music theory more than “music theory as a true practica.”

[1.3] Music theory has traditionally been divided between “speculative” and “practical” (also called “regulative”) theory (see Riemann 1882b). This division was later theorized and expanded by Carl Dahlhaus (1984, 6ff.), who added a third paradigm (“analytic” theory). Dahlhaus characterized speculative theory “as the ‘ontological contemplation of tone systems’” and practical theory as “the ‘regulation’ and ‘coordination’ of these tone systems applied to compositional practice” (Christensen 2002a, 13–14). The term “practical” can be understood in several ways, and it is fruitful to distinguish between primarily non-written approaches, typically practiced at the keyboard or vocally, and primarily written approaches, typically practiced in the exercise book or on the blackboard (see Utne-Reitan 2022a, 43). Generally, more attention has been given to speculative systems of musical thought than to the practices of the music theory classroom. It is telling that Richter’s close Leipzig colleague, Moritz Hauptmann (1792–1868), who is primarily remembered for speculative theory, has been more thoroughly studied.(3) But, during the last two decades, practical theory has been accorded heightened attention in research into the history of music theory, particularly due to the rapidly growing research on partimento and related pedagogies.(4) This research has, however, focused on the primarily non-written, keyboard-based pedagogies of the eighteenth century. Thus, in some sense, Richter has fallen between two stools: too “practical” (i.e., non-speculative) for the study of monumental theory and too “theoretical” (i.e., written) for the study of practical theory pedagogies.

[1.4] The lack of scholarly attention to the work of Richter, therefore, represents a significant gap in the history of music theory. This article aims to redress this omission by providing the first extensive treatment of Richter in English-language scholarship. Thus, it adds to the growing research on music theory pedagogy in the nineteenth century, such as Michael Masci’s (2023) examination of the pedagogical work of Charles-Simon Catel (1773–1830)—which shaped the theory training at the early Paris Conservatory and greatly contributed to making “harmony” a fundamental part of formalized music education.(5) The present article addresses Richter’s similar shaping of theory pedagogy at the early Leipzig Conservatory, an influence destined to spread far outside that institution’s walls.(6)

[1.5] Despite his popularity in the classroom, Richter’s reputation was tarnished by the many negative judgments of his works by central theorists and textbook authors in the early twentieth century and beyond. Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935; see Schenker 1954, 175–81) and Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951; see Schoenberg 1978, 15 and 195) explicitly targeted Richter when demonstrating what they believed was wrong with then-current theory pedagogy. Riemann and, more explicitly, his disciple Emil Ergo (1853–1922) similarly targeted Richter (Holtmeier 2011, 4 and 9ff.). In 1906, Rudolf Louis (1870–1914), who co-authored with Ludwig Thuille (1861–1907) an influential Harmonielehre released the following year, argued that Richter’s work had been “bad from the start” (Louis 1906, 431).(7) Similar negative judgments of Richter persisted in later scholarly literature. Carl Dahlhaus (1989a, 25), for example, considered Richter a “banal pragmatic,” and Johannes Forner (1997, 34) argued that Richter’s harmony textbook was “outdated already at the time of its publication.” However, no one has denied the great historical significance of Richterian pedagogy, particularly his harmony textbook. In Ludwig Holtmeier’s (2005, 227–28) words, “Richter’s Lehrbuch der Harmonie was the first internationally marketed and successful practical harmony textbook. Arguably, no practical harmony textbook before or since has enjoyed similar success.”(8) Rather, the constant targeting of Richter has reflected his pedagogy’s broad popularity. Indeed, Louis (1906, 431) claimed that Richter had long managed to retain a kind of monopoly on harmony pedagogy.

[1.6] Taking as a cue Louis’s assertion of Richter’s longstanding monopoly, I will discuss Richter’s position as a form of hegemony. I employ a Foucauldian outlook in my discussion of how Richter’s work attained and maintained a hegemonic position in the discourse of Western music theory.(9) I also employ Foucauldian concepts (such as discipline and power-knowledge) when discussing what characterizes Richterian theory pedagogy. According to Foucault (1981), discursive practice is regulated by, and people are disciplined through, a range of procedures that limit what is acceptable to speak, think, and do; one risks being considered mad by straying too far from the discourse’s taken-for-granted notions (see also Foucault [1972] 2002). For Foucault ([1977] 1991, [1980] 2015), the disciplinary power dynamics of modern society are more relational than hierarchical, more productive than repressive, and inseparable from knowledge and knowledge production (hence the term “power-knowledge”). They are thus part of producing discourses where certain knowledges and practices are taken for granted; that is, they gain hegemony. In the Gramscian sense of the word, hegemony is broadly (and somewhat reductively) defined as “the formation and organization of consent” (Ives 2004, 2). Understood as social consensus, hegemony arises not only out of domination but also from processes of negotiation and is always a matter of degree (Jørgensen and Phillips 2002, 76). From a Foucauldian discourse-theoretical perspective, then, hegemony is achieved and maintained through the productive workings of disciplinary power-knowledge.(10)

[1.7] The article is structured in six sections including this introduction. In the next section, I provide a brief account of Richter’s life and works. In the third section, I present an overview of Richter’s pedagogy. The fourth section expands on this by presenting a more detailed look at Richter’s teaching practice. These two closely related sections rely on a comparison of the contents of Richter’s textbooks to the exercises of one of his students, Edvard Grieg (1843–1907). In the article’s fifth section, I consider the legacy of this pedagogical approach, investigating how Richter’s work attained and maintained a strong hegemonic position in the discourse of Western music theory in the late nineteenth century, a position that was later challenged from various perspectives. Lastly, a brief conclusion rounds off the article.

2. Ernst Friedrich Richter

[2.1] Ernst Friedrich (Eduard) Richter was born October 24, 1808, in Großschönau, Saxony.(11) He was a son of a schoolteacher, and from the age of 10 he attended the Gymnasium in the nearby city of Zittau. The city boasted a rich musical life, and the Gymnasium offered Richter ample opportunity to develop his musical abilities: he sang in the choir and explored composition and conducting. In 1831, Richter moved to Leipzig to study theology at the university. At the same time, he embarked upon more serious music studies with Thomaskantor Christian Theodor Weinlig (1780–1842), and music soon became his main focus. From 1843–47, Richter conducted the Leipziger Singakademie. He held several organ positions in the city: from 1851 at the Peterskirche, 1862 at the Neukirche, and shortly thereafter at the Nikolaikirche. In addition to being an active musician, Richter also taught and composed—primarily sacred works and organ music.

[2.2] Richter is primarily remembered as a significant theory teacher and textbook author. When Felix Mendelssohn (1808–47) founded the Leipzig Conservatory in 1843, Moritz Hauptmann was the first theory teacher. Richter was appointed the Conservatory’s second theory teacher, also in 1843; he would also later teach organ. During the 1852–53 school year, the city’s university appointed him “Universitäts-Musikdirector.” The latter position, which had been held by prominent musicians in the city since the seventeenth century, entailed overseeing musical performances rather than academic responsibilities (see Klotz and Loos 2009, 261). I have found no evidence that Richter taught at the university; Riemann (1882a) refers to this role as simply “an honorary title.” Richter admired Mendelssohn as both a person and an artist, and it was Mendelssohn who tasked him with writing theory textbooks for the newly-established conservatory (A. Richter 2004, 296; E. F. Richter 1872b, v), suggesting a mutual admiration.

[2.3] Following Hauptmann’s death on January 3, 1868, the City of Leipzig appointed Richter to succeed him in this important role in Leipzig’s musical life (Altner 2007, 42–53). He then became the music director of the famous Thomanerchor as well as organist for the city’s main churches—most famously, the Thomaskirche. In the same year, during the celebrations of the Conservatory’s twenty-fifth anniversary, Richter was awarded the title of professor, which “at that time was an extraordinary honor that had never happened to any teacher at the Conservatory” (A. Richter 2004, 299).(12)

[2.4] In the early 1850s, after having taught at the Conservatory for about a decade, Richter published his first textbooks: Die Grundzüge der musikalischen Formen und ihre Analyse (E. F. Richter 1852b),(13) Die Elementarkenntnisse zur Harmonielehre und zur Musik Überhaupt (E. F. Richter 1852a), and Lehrbuch der Harmonie (E. F. Richter 1853). The first two seem to have had short publication histories.(14) Although the Elementarkenntnisse zur Harmonielehre includes “harmony” in the title, this short, 24-page book deals with elementary theory (scales, intervals, keys, and rhythm) as preparations for the study of harmony and not with harmony per se. It was his third book, an actual harmony textbook, that put Richter’s name on the map. The Lehrbuch der Harmonie appeared in thirteen editions in Richter’s lifetime. The year 1853 became a landmark in the history of Western music theory, as key works by no less than three central theorists were published by Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig: Richter’s harmony textbook, Hauptmann’s Die Natur der Harmonik und der Metrik (Hauptmann 1853), and the first volume of Simon Sechter’s (1788–1867) Die Grundsätze der musikalischen Komposition (Sechter 1853–54).

[2.5] E. F. Richter’s son, composer Alfred Richter (1846–1919), edited the textbook editions that appeared following his father’s death, making some adjustments and additions. The harmony book would reach its thirty-sixth edition in 1953, a century after the first edition appeared. Most of these were reprints rather than revised editions, including only minor changes (if any). In E. F. Richter’s lifetime, the main text and structure of the book remained more or less constant, with only a few minor additions to the text; the only major change was the addition of more exercises to the second edition (1857). The only other major revision and expansion of the textbook was conducted by Alfred Richter for the seventeenth edition (E. F. Richter 1886).(15) Much of the book’s reception history (including several translations) refers to the editions edited by Alfred Richter, who taught theory and piano at the Leipzig Conservatory in the period 1873–84 (Kneschke 1893, 52).(16)

[2.6] Following the 1853 harmony textbook, E. F. Richter published three more textbooks: Lehrbuch der Fuge (E. F. Richter 1859), Katechismus der Orgel (E. F. Richter 1868a), and Lehrbuch des einfachen und doppelten Kontrapunkts (E. F. Richter 1872b). All of them appeared in several editions. The 1872 release of the counterpoint textbook marked an important milestone. This book was issued as volume two of a trilogy: Die praktischen Studien zur Theorie der Musik. In the same year, the ninth edition of the 1853 harmony textbook was issued as the first volume of the same trilogy (E. F. Richter 1872a), and two years later, the third edition of the 1859 fugue textbook was issued as the third volume (E. F. Richter 1874).(17) The counterpoint textbook thus bridged the formerly separate harmony and fugue textbooks, comprising one pedagogical whole that reflected the pedagogical practice of the Conservatory, where they were the official textbooks. That this was Richter’s intention is apparent in the preface of the harmony textbook where he claims that the exercises “extend to the beginning of contrapuntal studies; the doctrine of counterpoint itself will follow, however, in a later volume after the same plan” (E. F. Richter 1853, v; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, vii).(18) Even though the Praktische Studien trilogy is arguably Richter’s main achievement as a theorist and pedagogue, most of the reception history has focused exclusively on the harmony textbook. Below, I will suggest that this separation of the harmony textbook from Richter’s broader pedagogical framework was unfortunate for his legacy.

[2.7] Following a long illness (A. Richter 1879, preface), E. F. Richter died on April 9, 1879, in Leipzig, at 70 years old. The Leipzig Conservatory arranged a commemorative concert in his honor on July 4, 1879 (Röntsch 1918, 22). The Richter family remained closely tied to the musical city of Leipzig during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, retaining strong influence. Not only Alfred but also his younger brother, Bernhard Friedrich Richter (1850–1931), would follow in their father’s footsteps. Bernhard Friedrich became became a successful church musician and professor, publishing studies of the history of musical life in Leipzig with a special focus on the Thomasschule and Johann Sebastian Bach. He would also temporarily serve as Thomaskantor in the interim period of 1892–93 (Altner 2007, 100ff.).(19)

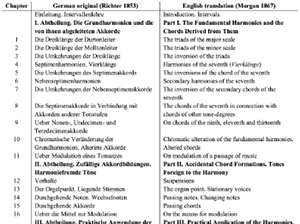

Example 1. Table of contents, E. F. Richter’s Lehrbuch der Harmonie (1853), from 1872 issued as the first volume of Die praktischen Studien zur Theorie der Musik

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

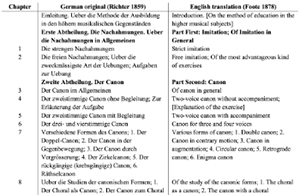

Example 2. Table of contents, E. F. Richter’s Lehrbuch des einfachen und doppelten Contrapunkts (1872), the second volume of Die praktischen Studien zur Theorie der Musik

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 3. Table of contents, E. F. Richter’s Lehrbuch der Fuge (1859), from 1874 issued as the third volume of Die praktischen Studien zur Theorie der Musik

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

3. Richter’s Pedagogy: An Overview

[3.1] Examples 1–3 reproduce the tables of contents for the three volumes of Richter’s Praktische Studien, showing the succession of topics in his pedagogical method.(20) One key feature of Richter’s approach is the smooth transition from harmony to counterpoint: the species-like exercises introduced in the third part of the harmony textbook are very similar to the exercises at the beginning of the counterpoint textbook.(21) In Richter’s framework, harmony primarily served as preparation for training in counterpoint and fugue (Frumkis 1995, 118; Utne-Reitan 2018, 63). The counterpoint training, following Johann Philipp Kirnberger (1721–83), begins with exercises in four parts and is further divided into Fuxian species—reduced to three rather than five—with two- and three-part exercises coming later.(22)

[3.2] Richter frames his pedagogy as a form of composition training. Like many other theory curricula of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the trilogy ends with the composition of fugues. The last chapter contains a note on the bridge from this to free composition. In Richter’s counterpoint textbook, he implies that the study of fugue is the best path to actual composition:

The end and aim of all these studies can be nothing else than actual composition, or an understanding of composition in general. In both cases the contrapuntal studies lead us by a straight path to the composition of the fugue and pieces of similar character; indirectly, however, to the composition of pieces of all other classes. (E. F. Richter 1872b, 90; trans., E. F. Richter 1884, 94, emphasis original)(23)

[3.3] Richter gradually expands the creative freedom of the student through his trilogy of textbooks. The harmony book consists primarily of technical exercises focused on voice leading in four-part harmony. Most of the exercises are figured basses to be written out in four parts. In the later chapters of the book, other parts (soprano, alto, tenor) are given but are still to be realized with predetermined harmonies. It is only starting from the counterpoint textbook that students can devise their own harmonies, initially within a strict diatonic style that limits their creative possibilities. The limits are gradually broadened, leading up to the culmination in fugal writing. There is thus a gradual pedagogical process from technical realization of four-part voice leading in predetermined harmonic progressions to composition of fugues. In the following close examination of how this works in practice, I will consider not only the textbooks but also Edvard Grieg’s notebooks with his student exercise solutions.

[3.4] Grieg studied at the Leipzig Conservatory in the period 1858–62 (with a leave in the fall of 1861 due to sickness). The students at the Conservatory attended two theory classes taught by different teachers. Grieg first took the theory classes of Richter and Robert Papperitz (1826–1903),(24) and later those of Richter and Hauptmann. Grieg thus studied continuously with Richter throughout his training. Grieg’s exercise books have been preserved and constitute a valuable primary source for researchers studying his theory training.(25) Rather than taking exams, almost all of students in Leipzig were assessed based on their exercise books alone (Navon 2020, 84). The students’ progress was thus also in a sense under continuous surveillance and assessment throughout the school year. This explains the care Grieg put into his exercise books, which he kept his whole life. There are three books directly connected to his theory education, filled with exercise solutions (967 exercises in total) and added corrections (Utne-Reitan 2018, 62).(26) One and a half books contain exercises completed for Richter, giving valuable insights into Richter’s teaching practice in the middle of his professional career. When Grieg arrived in Leipzig in 1858, Richter had already taught at the Conservatory for 15 years, his harmony textbook had appeared in a second edition, and his fugue textbook was in preparation for publication the following year. In addition to his already composition-oriented studies in theory, Grieg also studied composition with Carl Reinecke (1824–1910) at the Conservatory. These studies focused on free composition in larger forms (Christophersen 2016, 220; Utne-Reitan 2020, 50–51). Grieg, for example, composed a String Quartet in D minor (presumed lost) for Reinecke. While he studied theory during all his years at the Conservatory and always with two teachers, Grieg studied composition only during his last year and with only one teacher, indicating how strongly theory training was emphasized at the Conservatory.

[3.5] Grieg’s exercise books indicate that the Conservatory loosely followed the progression that was later codified in Richter’s Praktische Studien trilogy: four-part harmony (realizing figured basses), a smooth transition to four-part counterpoint, four-part chorales, counterpoint in fewer parts, double counterpoint, canons, chorale preludes, and, lastly, fugues.(27) In his dissertation on Johan Svendsen (1840–1911), another Norwegian composer who studied with the same theory teachers in Leipzig (1863–67), Bjørn Morten Christophersen (2016, Chapter 9) compared Grieg’s and Svendsen’s exercises and found a roughly similar progression of teaching topics and exercises.(28) Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the textbook trilogy is representative of Richterian pedagogical practice at that time.(29) Grieg’s exercises demonstrate the central position of counterpoint in Richter’s teaching. For Richter, harmony training functioned primarily as preparation for studying (tonal) counterpoint through learning basic voice-leading and doubling principles by way of realizing increasingly more complex figured basses (Utne-Reitan 2018, 67–68).(30)

[3.6] Dahlhaus (1989a, 26) claimed that the key feature of the Leipzig Conservatory’s theory pedagogy was a form of “poetic counterpoint“—combining the “poetic” aesthetic of the early Romantics, particularly Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann (1810–56), with the polyphonic writing associated with J. S. Bach—where the linear-contrapuntal perspective was foundational to the understanding and teaching of harmony.(31) In his counterpoint textbook, Richter indeed called Bach “the greatest of all Contrapuntists” before pointing to Mendelssohn and Schumann as the best models for the use of counterpoint in more recent styles (E. F. Richter 1872b, 7; trans., E. F. Richter 1884, 6).(32) According to Patrick Dinslage (2000, 102), all exercises at the Conservatory aimed at developing “harmony in a contrapuntal style.” Dahlhaus’s claim also signals a moderate aesthetic that is neither archaic (in the sense of strict Palestrina or Bach counterpoint) nor progressive (in the sense of the more recent chromatic harmony of Liszt and Wagner). This was a general characteristic of the Leipzig Conservatory—and the musical city of Leipzig—which had close ties to the traditionalist side of the so-called “War of the Romantics” (Forner 1997; Wasserloos 2004, 54–55). There seems to be no consensus in the literature on the stylistic norms put forward by Richter, however. Some commentators claim that Richter’s harmony textbook was extremely conservative, while others view it as rather progressive. Michael Fend (2005, 421), for example, asserts that “the level of harmonic complexity discussed by Richter does not go beyond the early classical style.” On the other extreme, Christophersen (2016, 228) posits that “Richter’s book progresses steadily and thoroughly to advanced modulation techniques and all kinds of altered chords,” and thus “must be regarded as rather modern even at the time it was written.” In my view, Dahlhaus’s characterization of the Leipzig Conservatory approach as one of “poetic counterpoint” (implying a moderate position) is fitting, and I find that Fend and Christophersen place Richter too far at either end of the spectrum. Richter’s moderate aesthetic positioning is also connected to the pragmatism that is so central to his pedagogy.

[3.7] Richter consistently called his pedagogy practical. The titles of most of his textbooks (and that of the main trilogy itself) contain the word “practical.” In the preface to his harmony textbook, he writes:

The advancing student of music has to apply his whole power to his technical education, because it will cost him time and trouble enough to attain the stand-point, starting from which he can with greater ease advance towards the position of a real artist. Here the question to be asked is not Why? the inquiry of immediate application is, How? (E. F. Richter 1853, v; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, vi)

[3.8] Richter mentions Hauptmann’s work in passing (perhaps out of courtesy to his friend and close colleague) but remains clear on the irrelevance of speculative work for conservatory students, who should focus on technical (i.e., compositional) matters. It should be mentioned, however, that the intertextual references to Hauptmann increased slightly during the publication history of Richter’s books. In the 1868 second edition of the fugue textbook, Richter added an explicit reference to Hauptmann in his discussion of tonal answers (E. F. Richter 1868b, iv and Chapter 11). In the edits he made to the harmony textbook following E. F. Richter’s death, Alfred Richter also added several references to Hauptmann (E. F. Richter 1886, 88 and 205–6). Partly due to the efforts of Alfred Richter, the gulf separating the two Leipzig theorists was made less apparent in the later editions of Richter’s works.(33) The focus on practicality in Richter’s publications nonetheless remained very strong. In Joshua Navon’s (2019, 142) words, Richter “regarded extensive regimes of written work as ‘practical.’ Richter’s perspective on what constituted practical training in music theory seems to have been based more on what his textbooks avoided: namely, the more speculative arenas of music-theoretical discourse.” Richter’s idea of practicality was closely connected to teaching composition technique. But, in the preface to his form textbook, Richter also distanced himself from the extensive and text-heavy composition manuals (Kompositionslehren) that had appeared in recent years, implicitly critiquing Adolf Bernhard Marx (1795–1866). Because Richter (1852b, iii) was convinced that “only the practical way can lead to the goal,” he favored a brief and to-the-point approach. Christophersen compares Richter’s approach to instrumental etudes, calling the exercises “compositional etudes”:

The student focused on one or a few technical problems at a time, and his or her repertoire of technical devices was gradually expanded as a result. The young composers wrote many exercises of the same kind before they proceeded to the next level. (Christophersen 2016, 226)

[3.9] This resonates well with Richter’s claim regarding species counterpoint that “the relation of our exercises to the real art-forms will be similar to that which the preparatory studies of a painter bear to a whole picture, if he repeatedly execute [sic] detached parts; such as a hand, foot, eye, tree, etc.” (E. F. Richter 1872b, 12; trans., E. F. Richter 1884, 11–12 ). This statement implies that Richter viewed other exercises (such as the treatment of chorales) as closer to real art forms. Arguing that “every art has its mechanical side” that first must be mastered, Richter intended his textbooks to progress “methodically from the particular to the general” (E. F. Richter 1868b, 1 and iii; trans., E. F. Richter 1878, 7 and 5). Through a Foucauldian lens, one can claim that the early training in voice-leading and doubling rules were essential in disciplining the students before gradually giving them more freedom, first writing counterpoint in strict style and later creating small student-compositions—chorale preludes and fugues—in a more “poetic” idiom (to echo Dahlhaus). Reflecting on the early stages of the disciplinary process, Grieg in 1903 vividly recalled how Richter reviewed each student’s exercises in the class:

In E. F. Richter’s class, where we were given a bass line, at first I always wrote harmonies that I myself liked instead of those prescribed by the rules of the thoroughbass. Later I could certainly invent many a theme suitable for use in a fugue, but to make this theme conform to the conventional rules—that, for the time being, was not for me. I started from the faulty premise that if my works just sounded good, that was the main thing. For Richter, on the other hand, the main thing was that the problem should be solved correctly. And when solving problems rather than creating music was the matter of greatest importance, then from his point of view he was certainly right. But this is what I could not comprehend at that time. I defied him obstinately and stuck to my own opinion. I did not yet understand that what I was supposed to learn was: to limit myself, to do as I was told, and—as it says in the preface to his harmony textbook—not to ask why. Fortunately, we never became enemies. He only smiled indulgently at my stupidities, and with a “No! Wrong!” he corrected them with a thick pencil-mark, which did not in fact teach me much. But there were many of us in the class, and Richter could not spend time with each of us individually. (Grieg 2019, 81)(34)

[3.10] In several sources, all stemming from rather late in his life, Grieg claimed he did not learn anything in Leipzig (Benestad and Schjelderup-Ebbe 2007, 41–42). However, most Grieg scholars hold that his remarks were colored by the four decades separating them from the actual events, ending with him (for different reasons) wanting to distance himself from the Conservatory and the city (Utne-Reitan 2018). The exercise books do not support Grieg’s claim that he just wrote what he thought sounded good, disregarded the given basses, and learned nothing. With few exceptions, they reflect diligent work with the given basses—showing clear progression—where the corrections are primarily those of common voice-leading and doubling errors typical of beginners.(35) While Grieg probably challenged his teachers on some points, his exercise books strongly indicate that he took part in (and was disciplined through) the power-knowledge regime of Richterian theory pedagogy at the Conservatory.

[3.11] Although much indicates that Grieg’s total dismissal of the Leipzig Conservatory’s teaching was exaggerated, there were indeed aspects of its pedagogical approach that teachers and students found far from ideal. In an 1844 letter to Franz Hauser (1794–1870), Hauptmann claimed that the Conservatory’s students would “learn their drill like a company of soldiers; it is only the awkward squad [die ganz ungeschickten] that gets noticed” (Hauptmann 1871, 2:25; trans. Hauptmann 1892, 2:20).(36) Even though he is most famous for his speculative works, Hauptmann primarily taught practical theory at the Conservatory (as Grieg’s exercises written for him attest to). While in the letter he laments the size of the student body, wishing for more time with each student,(37) the situation he describes is indicative of the mechanisms of power-knowledge in this discourse, where, in the most effective and timesaving manner, students were disciplined “like soldiers” while teachers focused on keeping “the awkward” in line making sure everyone followed the (voice-leading) rules. Hauptmann’s frustration reflects a broader transition from an individual master–apprentice pedagogy to an institutionalized group-based pedagogy that to a greater extent required homogeneity and obedience.(38) Christoph Hust (2019, 196–97) cites exam protocols in which Richter similarly laments the level of the students, but Richter seems to have considered this less a structural problem than a question of implementation. These sources are, after all, from the Conservatory’s second year of operation, and teaching practice within this new institutional context was thus naturally still in development. That said, student accounts suggest that at least some of the problems persisted. Clara Kathleen Rogers (1844–1931), who studied at the Conservatory at the same time as Grieg, described a typical lesson with Richter in her 1919 memoirs:

The study of harmony and counterpoint, which to me was of greatest interest, seemed to make but small appeal to the other members of Richter’s class. It is true that our instructor was not exactly what one would call inspiring. But his lack of spirit may well have been due to his ten years’ experience with pupils who would not take the trouble to learn what he was there to teach.. . . At the hour of our class lesson Richter took his seat at the head of a long table, on either side of which were ranged the pupils with their exercise books before them, pencil in hand. These books were handed up to him one by one for correction. In each was the chorale dictated by him in the foregoing lesson with a contrapuntal accompaniment for three or four voices which it had been our task to fit to it. His blue pencil was kept busy while he flung out every now and again “querstande” (false relation), “verdeckte quinten” (hidden fifths), and so forth, through the whole gamut of harmonic crimes which to-day form the bone and sinew of modern music! (Rogers 1919, 175, emphasis original)

[3.12] Similarly to Grieg and Rogers, Ethel Smyth (1858–1944)—who studied at the Conservatory in 1877–78—wrote in an 1878 letter that “the exercises you have worked are just glanced through and there is hardly time to explain why this or that is wrong, still less to go through the various ways of correcting it and then choose the best” (Smyth, cited in Navon 2020, 85, emphasis original). Although this regime certainly had its flaws, it also had its strengths, and its disciplinary procedures would (for better or worse) be mimicked around the world. In the following, I will—based on Grieg’s exercises and Richter’s textbooks—turn to the nuts and bolts of Richter’s instruction.

4. Richter’s Pedagogy: A Closer Look

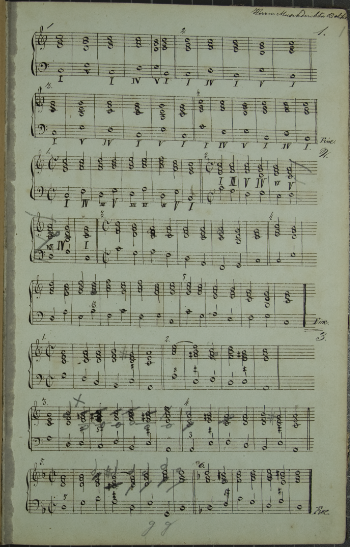

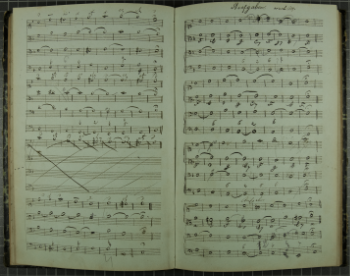

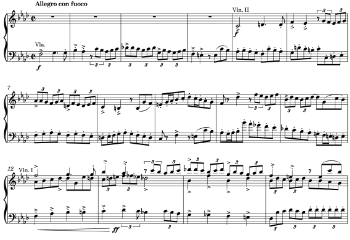

Example 4. Grieg’s first exercises for Richter (Bergen Public Library, The Grieg Archives)

(click to enlarge)

[4.1] Example 4 reproduces the first page of Grieg’s exercises for Richter’s class. The title page of the book reads “Edvard Grieg. October 1858.” Grieg used the book for both Papperitz and Richter, writing Papperitz’s exercises front-to-back and Richter’s back-to-front. This first page from the back of the book contains Grieg’s exercises for the first three lessons with Richter (the top right reads “Herrn Musikdirector Richter”). The exercises are written in ink with what are presumably Richter’s pencil corrections added in the lessons. The pencil markings eliminate voice-leading mistakes and fix wrong chords (e.g., those with missing accidentals). Richter quickly incorporates all diatonic triads in the exercises. For the first lesson (marked “1.” in the right-side margin), Grieg practices connecting root-position primary triads in major (I, IV, V). In the second lesson, he practices using all root-position triads in the major scale, including the diminished triad.(39) For the third lesson, Grieg practices connecting root-position triads in (harmonic) minor, already at this stage employing the augmented triad. The basses given for all these exercises are printed in the extended second edition of Richter’s harmony textbook (see E. F. Richter 1857, 18, 25, and 32).

[4.2] This page tells us much about Richter’s pedagogical approach. These sorts of exercises were intended to teach the students “the right and natural connection of the chords among themselves” (E. F. Richter 1853, 9; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, 21, emphasis original). Richter begins with a rather large vocabulary of chords (lessons 4 and 5 introduce inversions; from lesson 6, seventh chords are introduced) focusing on teaching how to properly connect them with good voice leading—what he calls the “pure leading of voices,” which gives rise to “the so-called pure harmonic structure, also called strict style,” better known in German as reine Satz (E. F. Richter 1853, 12; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, 24, emphasis original).(40) The student learned through trial and error—through practice rather than theoretical speculation. Indeed, Richter presents no progression rules typical of more speculative (and modern) approaches in his harmony textbook, only arguing on a case-to-case basis whether a chord progression is good based on the quality of the voice leading, often noting whether it is commonly used.(41) Note, for example, how in the very first set of exercise progressions, he asks for both IV–V and V–IV without implying that one progression is more “correct” than the other (the latter is sometimes called a “retrogression” in modern textbooks).

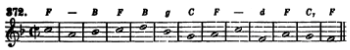

Example 5. Modulation exercise in Richter 1853, 85

(click to enlarge)

[4.3] That Richter includes all diatonic triads from the beginning also tells us a great deal about his conception of tonality. In the introduction to elementary theory, he wrote that “the term key is understood to mean the epitome of all harmonic and melodic combinations based on one and the same major or minor scale” (E. F. Richter 1852a, 15). The following year, he writes in the harmony textbook that “the diatonic scale makes up the content of a key, [and forms the foundation of the melodic successions,] so also the triads, which are founded upon the different steps of the scale, will form the essential part of the harmonic content” (E. F. Richter 1853, 10; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, 22).(42) He continues by stating that I, IV, and V “contain all the tones of the scale; that they form the fundamental features of the key, and that they are, and must be those most frequently employed in practice, if the key is to present itself clear and distinct” (E. F. Richter 1853, 10–11; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, 22–23). While Richter describes an interplay between scale and chords, his idea of what constitutes a key is heavily scale-based.(43) This is reflected in how quickly Richter shows how all diatonic triads can be employed. There is no speculative foundation leading him to focus extensively on certain chords or progressions. Rather, his approach is pragmatic and empirical. Because Richter considers all chords derived from different scales as modulations, his Roman numeral analyses of chromatic passages suggest rapid successions of modulations (Example 5).

[4.4] Richterian pedagogy is most closely associated with Roman numeral analysis. A system of Roman numerals (uppercase, all same size) for harmonic analysis was first introduced by Georg Joseph “Abbé” Vogler (1749–1814); subsequently, Gottfried Weber (1779–1839) developed this system in the three-volume Versuch einer geordneten Theorie der Tonsetzkunst (1817–21; see Bernstein 2002). Weber used large uppercase numerals for major chords and small uppercase numerals for minor chords. As early as 1820, this was adopted in a harmony textbook by Friedrich Schneider (1786–1853; see Schneider 1820). While Richter was not the first textbook author to adopt Weber’s Roman numeral system, he played an important role in securing its central position in modern music theory pedagogy. Although Richter explicitly cites only Weber, Janna Saslaw (1992, 373ff.) has argued that he also draws on ideas from Vogler.

[4.5] Weber’s theoretical project was primarily of an empirical and descriptive nature (Kopp 2002, 40ff.; Rummenhöller 1967, 11ff.), fitting well with Richter’s anti-speculative stance. Unlike Weber, Richter includes the augmented triad (labelled III’ in minor) as an independent chord, allowing all triads generated from the harmonic minor scale to be included as equal elements of the tonal system. He did remark, however, that the diatonic third-degree triad—in both major and (harmonic) minor—“is very difficult to connect naturally and effectively with other chords, and therefore seldom occurs” (E. F. Richter 1853, 30; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, 43). Rarely appearing as the fundamental harmony on the third degree of the minor scale, the augmented triad (which Richter notes is common in later music) belongs to the category of altered chords. He nonetheless included it in his early exercises (see Example 4). Apart from this acceptance of the augmented triad, Richter’s main contribution was the concise and practical approach to teaching theory employing Weberian nomenclature. As Hust (2016) notes, this entailed replacing Weber’s argumentation and reasoning with the description of compositional phenomena and their translation into rather dogmatic rules (which only to a certain extent would correspond with actual musical practice). Although it was based on Weber’s empirical and descriptive work and thus represented a step towards a more analytically oriented theory pedagogy, compared to the older figured-bass approaches, little suggests that the adoption of Roman numerals in Leipzig entailed a heightened focus on the analysis of repertoire. The great majority of the examples in the Praktische Studien trilogy were composed by Richter for pedagogical purposes; examples from the repertoire were exceptions, and are found mostly in the fugue textbook.(44)

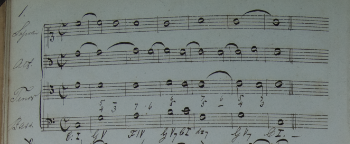

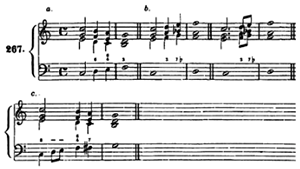

Example 6. Example of analytical annotation in Grieg’s exercises for Richter (Bergen Public Library, The Grieg Archives)

(click to enlarge)

[4.6] Although Roman numerals play a central role in Richter’s pedagogy, and popularizing them represents his most important contribution to the history of music theory, they were by no means the only system he used. The extensive use of Roman numerals in Richter’s work was mostly limited to his introductory harmony text. Richter’s harmony exercises were primarily given with figured bass notation, or, when another voice was given, Weberian chord symbols (i.e., uppercase letters for major chords, lowercase for minor chords). Richter consequently used three different systems for chord identification: figured bass indicating chord content and structure, Roman numerals indicating diatonic scale degree, and chord symbols indicating root tone. The latter two Weberian systems indicate whether a chord is major or minor and whether it is a triad or a seventh chord, but not its inversion, which was only shown by figured bass.(45) In Grieg’s exercise books, the amount of analytical annotation varies. Some harmony exercises have only the given figured bass, while other exercises use all three systems simultaneously. The counterpoint exercises include far fewer analytical annotations, providing only figured bass if any annotations are given at all. Example 6 shows Grieg’s solution to a harmony exercise with suspensions, demonstrating how all three chord-labeling systems (and the various C clefs) were used in teaching.(46)

[4.7] The suitability of maintaining the timeworn, primarily keyboard-based, figured-bass pedagogy was hotly debated among German theorists in the middle of the nineteenth century.(47) Richter did not want to be associated with the older figured-bass (or “thoroughbass”) manuals, making it clear in the preface to the third edition of his harmony textbook that the figured basses were only used “as means to the end” when teaching “the first exercises in harmonic connections” (E. F. Richter 1860, x; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, ix). In the counterpoint textbook, he argued that although Weber’s “work may contain much that is awkward and circumstantial, he has the credit of having brought system and clearness into the old confused methods of the ‘Thorough-Bass’ schools” (E. F. Richter 1872b, 10; trans., E. F. Richter 1884, 9). Richter had studied with Weinlig, who also taught Wagner, and who himself had studied in Bologna with Stanislao Mattei (1750–1825). Mattei directly connected Weinlig to Italian partimento pedagogy, which he adopted in his own teaching (Menke 2018, 54ff.). Richter thus knew the old pedagogy well but clearly wanted to distance his approach from it.(48) For example, the concept of the Rule of the Octave plays no part in his pedagogy. Richter retained the figured basses, and his practical focus remained strong; but his approach emphasized written exercises and compositional technique. Although Richter strived to keep his textbooks concise, they were nonetheless much more text-heavy than the old figured-bass manuals and collections of partimenti. In the modern Harmonielehre tradition, even practical teaching required a certain amount of written explanation and codification of musical principles. There are also no signs in Richter’s pedagogy of the improvisational-performative aspects typical of the partimento approach. Richter indeed contributed to a broader international “turn towards writing” in the history of music theory pedagogy, which would make written approaches the hallmark of modern instruction (see Utne-Reitan 2022b). But one thing he retained from the old pedagogy—although heavily transformed—was the close affinity between the domains of harmony and counterpoint.

Example 7. From Grieg’s exercises in plain four-part realizations for Richter (Bergen Public Library, The Grieg Archives)

(click to enlarge)

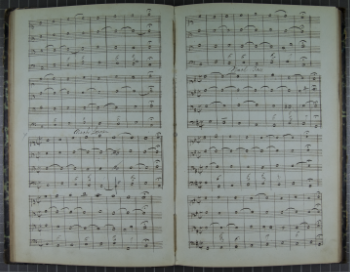

Example 8. From Grieg’s exercises in plain counterpoint for Richter (Bergen Public Library, The Grieg Archives)

(click to enlarge)

[4.8] The transition from harmony to counterpoint is even smoother in Grieg’s exercise books than in Richter’s Praktische Studien textbooks. During the spring of 1859, Grieg proceeded from varied exercises in four-part realizations (first plain, then figured) of cantus firmi with given harmonizations (Example 7), to exercises in writing both plain and figured four-part counterpoint alongside traditional and rhythmically embellished cantus firmi (Example 8).(49) In Richter’s publications, the former is covered at the end of the harmony textbook and the latter at the beginning of the counterpoint textbook. These types of exercises are very similar, the only difference being that the harmonies were given in the former, and should be composed (i.e., resulting from writing good counterpoint) in the latter. As Richter states in the harmony textbook:

The difference consists only in this, viz.; that here [the exercises in the third part of the harmony textbook], the succession of the chords is prescribed, and it only remains to form the leading of the voices, while in the contrapuntal exercises the knowledge of harmony, as well as certainty in its use, is assumed, so that the succession of the harmonies can be left to our own choice. (E. F. Richter 1853, 167; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, 194)(50)

[4.9] Comparing Grieg’s exercises to the structure of Richter’s textbooks (Examples 1–3), Richter seems to have skipped the last chapters of the harmony book to make the transition as smooth as possible in his lessons. These primarily diatonic exercises also demonstrate Richter’s previously mentioned focus on “pure harmonic structure,” or reine Satz. In his counterpoint textbook, as reflected in Example 2, he operated with three species: “plain counterpoint” (Fuxian first species), “figurated counterpoint” (combining Fuxian second and fourth species), and “counterpoint in quarter-notes” (Fuxian third species). After writing technical species exercises, the student puts the knowledge and craft acquired to practical use in chorales, writing both plain and figurated realizations. As with the harmony teaching, the types of exercises in Grieg’s exercise books roughly overlap with the progression of the counterpoint book, but with certain omissions.(51)

Example 9. Example of the development of melody in Richter 1853, 151

(click to enlarge)

Example 10. Example of the development of melody in Richter 1853, 152f

(click to enlarge)

Example 11. Example of the development of melody in Richter 1853, 153

(click to enlarge)

Example 12. Examples of passing chords in Richter 1853, 117

(click to enlarge)

[4.10] Richter, who explicitly framed his pedagogy as composition training, demonstrated the connection between technical training in this “pure” domain and actual composition. In the harmony textbook, this is particularly explicit in his presentation of non-harmonic tones and the chapter on melody construction (E. F. Richter 1853, 114ff. and Chapters 19–20). In the latter chapter, he first presented a cantus firmus with given harmony (Example 9), then with rhythmic embellishment (Example 10, bottom staff), then further rhythmic and melodic elaboration (Example 10, top staff), and finally, harmonic elaboration (Example 11).(52) Although the surface has been completely changed into a period in a prototypical Romantic style, Richter posits that this, in essence, “is just as simple as that shown before” (E. F. Richter 1853, 153; trans., E. F. Richter 1867, 180).(53) In the harmony textbook, Richter’s constructed demonstration is followed by a similar example that moves from a hypothetical “pure” background to the first phrase of the second movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet in E-flat major, op. 74. This is one of the very few examples in the book from the musical literature (there are only three, all Beethoven), and it serves to demonstrate a connection between the theory exercises and actual music. In these examples, Richter moves from background to foreground, focusing on demonstrating a compositional process more than an analysis. Although not rigorously theorizing it (which would go against his practical dogma), Richter clearly championed a multi-layered structural concept of music with a “pure” background and elaborated foreground.(54) This also enabled the explicit inclusion of the passing chord in Richter’s presentation (some of his examples of passing chords are reproduced in Example 12). In short, the aim of the theory training was to first teach the mechanisms of the “pure” background and then bridge this knowledge to actual composition by elaborating the foreground. This explicit idea of moving from background to foreground is one notable difference between modern theory pedagogy and the pedagogy associated with the partimento tradition of the eighteenth century.

[4.11] Richter admitted that sometimes—particularly when practicing diatonic strict-style species counterpoint—“the blooming land of musical poesy still lay far in the distance, invisible to the view” (E. F. Richter 1872b, 89; trans., E. F. Richter 1884, 93). As a countermeasure, he occasionally shows examples of what could be considered more “poetic” passages related to the technical exercises (e.g., Examples 9–11). Despite Richter’s focus on “pure voice-leading” and “strict style,” the contents of his textbooks (and Grieg’s exercise books) were not restricted completely to archaic writing. Here, Dahlhaus’s idea of “poetic counterpoint” is illuminating. It is particularly in Grieg’s later and more broadly conceived exercises that the term is warranted. The many chorale preludes and fugues are indeed to be regarded as student compositions, going beyond mere technical exercises. Many of them are Romantic in style, have posthumously been published, and are listed in the Grieg Work Catalogue (Fog, Grinde, and Norheim 2008): the Fugue for String Quartet in F minor, EG 114; the choir fugue Dona nobis pacem, EG 159; Seven Fugues for Piano, EG 184a–g; Nine Organ Chorales, EG 185a–i; and Seven Organ Fugues, EG 186a–g. The latter include the Double Fugue on the Name GADE, EG 186f, honoring one of Grieg’s composer idols. These exercise-compositions, from the end of Grieg’s theory studies, demonstrate some of the “poetic” potential of the Leipzig Conservatory’s theory pedagogy.

Example 13. Grieg, Fugue for String Quartet in F minor, EG 114, mm. 1–30, condensed score

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 14. Grieg, Fugue for String Quartet in F minor, EG 114, mm. 40–45, condensed score

(click to enlarge)

Example 15. Grieg, Fugue for String Quartet in F minor, EG 114, mm. 80–94, condensed score

(click to enlarge)

[4.12] In particular, Grieg’s string quartet fugue, written as an exercise for Richter in December 1861, has been well-received. In his ground-breaking study of Grieg’s student years, Dag Schjelderup-Ebbe (1964, 56 and 60) claims that it “is one of the most important and artistically satisfying compositions of Grieg’s earliest period on the whole,” also arguing that, since “Grieg did most significant work under Richter and wrote the remarkable string quartet fugue for him, Richter emerges as Grieg’s most important theory teacher, and to him major credit should be given for the forming of his early style.” Example 13 reproduces the exposition and the following stretto. Spanning 103 measures, the fugue develops its subject using common contrapuntal techniques (stretti, augmentation, etc.). At one point, Grieg superimposes a highly contrasting cantabile counterpoint in the first violin against the dramatically expressive fugue subject in the viola (Example 14). Toward the end of the fugue, the polyphonic texture momentarily breaks down in favor of a homophonic and chromatically coloristic passage (Example 15). Here, Grieg combines (inverted) pedal points, chromatic lines, and abrupt changes in dynamics. The result, in Schjelderup-Ebbe’s (1964, 59) assessment, “approaches twentieth century effects and is thus a very progressive passage for its time.” Schjelderup-Ebbe (1964, 58) rightly claims that this foreshadows Grieg’s later style. There is, for example, a clear link to the systematic linearity found in certain chromatic passages in Grieg’s later works (Utne-Reitan 2021b). We cannot know exactly how Richter reacted when reviewing this fugue, but its entry in Grieg’s exercise book does not have any corrections beyond a few pencil marks pointing out voice-leading errors.

[4.13] The expressiveness and large contrasts embedded in this fugue support Dahlhaus’s idea that a “poetic counterpoint” was taught at the Leipzig Conservatory. This is not to say that Grieg’s exercises necessarily reflect those of a prototypical student. While the majority reflect the moderate, “pure” style of Richter’s textbooks, some exercises (particularly those written for Papperitz) are more progressively chromatic and probably challenged the stylistically moderate music-theoretical discourse at the Conservatory.(55) To what extent Grieg was a typical student is a complex question that will require further research (see Utne-Reitan 2018). In any case, his exercise books indicate that Grieg was a diligent student who mostly followed his teachers’ instructions. He also received positive testimonies from them on his diploma (Benestad and Schjelderup-Ebbe 2007, 47–48). I therefore argue that the late student compositions, including the string quartet fugue, at least demonstrate some of the “poetic” potential of Richter’s pedagogy.(56)

5. The Reception and Legacy of Richterian Theory Pedagogy

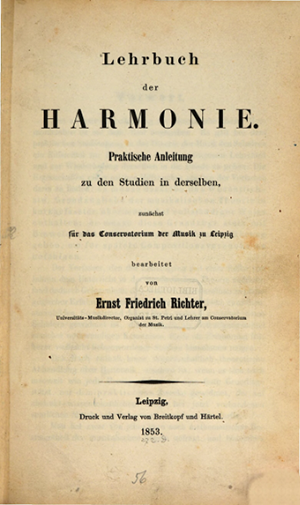

Example 16. Title page, first edition (1853) of E. F. Richter’s Lehrbuch der Harmonie (The Bavarian State Library)

(click to enlarge)

[5.1] Richter’s institutional affiliations and professional positions helped him gain legitimacy as a textbook author. Richter (or his publisher) intentionally highlighted Richter’s credentials on the title page of the books. The title page of the first edition of the 1853 harmony textbook is reproduced as Example 16. Its subtitle (Praktische Anleitung zu den Studien in derselben zunächst für das Conservatorium der Musik zu Leipzig) underlines that the method presented is employed in the Leipzig Conservatory, and beneath the author’s name, his roles are listed (Universitäts-Musikdirector, Organist zu St. Petri und Lehrer am Conservatorium der Musik). The latter is central in discursively constructing credibility through the text’s author-function, underlining Richter’s central position as teacher and musician.(57) Following Richter’s appointment as Thomaskantor and promotion to professor, the author-function is constructed as Professor, Cantor an der Thomasschule und Musikdirektor an den beiden Hauptkirchen, Lehrer am Conservatorium der Musik (E. F. Richter 1870b, title page).

[5.2] Due to the widespread international recognition of the Leipzig Conservatory and the Thomasschule (with its Thomanerchor and ties to J. S. Bach), this signature must have signaled a high level of professionalism and trustworthiness in the late nineteenth century. At this time, being affiliated with the Leipzig Conservatory in particular was no small matter. Although I will argue that this institutional affiliation was not the sole reason for Richter’s success, the importance of the association should not be underestimated. Earlier, in the first half of the nineteenth century, the Paris Conservatory (founded in 1795) had been widely considered the leading institution—and model—for professional music education. In the second half of the century, however, this position was claimed by the Leipzig Conservatory.(58) What Yvonne Wasserloos (2004) calls the “Leipzig model” spread widely and was central in shaping modern conservatory education in large sectors of the world (see also Grotjahn 2005 and 2006).

[5.3] Nonetheless, Richter’s work seems to have gained its central position in Western music-theoretical discourse gradually and rather quietly. Indeed, the initial publication of Richter’s Lehrbuch der Harmonie in 1853 caused no stir in German-speaking lands; it was not even reviewed in the leading musical periodicals (Hust 2017, 411; Rigaudière 2014, 4). As mentioned in the introduction, however, the original German version of Richter’s harmony textbook remained in print for a century. It would also have a significant impact beyond the German-speaking countries, appearing in many translations during the second half of the nineteenth century and in the early twentieth century: English (1864, 1867, 1873, 1896, 1912), Russian (1868), Swedish (1870), Danish (1871), Polish (1871), French (1884), Spanish (1892), Dutch (1896), Japanese (1913), and Italian (1935)—several of which appeared in many editions.(59) Due to the Leipzig Conservatory’s international profile—in addition to German-speaking countries, many students came from the UK, North America, Russia, and Scandinavia (Grönke 2021, 180–81; Wasserloos 2004, 65ff.)—many of Richter’s own students played a key role in this project. Of the five English translations, three of the translators were Leipzig Conservatory alumni (Rigaudière 2014, 2). As Hust (2019, 208ff.) has argued, the translated editions met different needs within, and were thus marketed somewhat differently for, the various national contexts.

[5.4] Adding to the translations are the many original harmony textbooks that were heavily influenced by Richter, implicitly or explicitly adopting key features of his approach.(60) By the time the third edition appeared in 1860, Richter’s harmony textbook had become something of a reference work, with textbook authors such as Benedikt Widmann (1820–1910) and Ferdinand Hiller (1811–85) explicitly citing and building on Richter’s work (see Rigaudière 2014, 4).(61) Richter was not only “famed as ‘Europe’s theory teacher’” (Forner 1997, 34), he also gained considerable influence across the Atlantic. David M. Thompson (1980, 75) describes harmonic theory in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century as “a field of thought dominated by Richter.”(62)

[5.5] In addition to Alfred Richter, whose contribution was discussed above, Salomon Jadassohn (1831–1902)—a Leipzig Conservatory alumnus and, from 1871, also a teacher there—was particularly instrumental in maintaining the predominance of Richterian pedagogy.(63) In the 1880s, Jadassohn published his five-volume Musikalische Kompositionslehre. His Kompositionslehre was divided into two parts, of which the first (Die Lehre vom reinen Satze)—consisting of his Lehrbuch der Harmonie (Jadassohn 1883), Lehrbuch des einfachen, doppelten, drei- und vierfachen Contrapunkts (Jadassohn 1884b), and Die Lehre vom Canon und von der Fuge (Jadassohn 1884a)—mirrored Richter’s Praktische Studien trilogy.(64) Jadassohn’s harmony textbook became particularly popular. Robert W. Wason (2002, 64) observes that, together, the textbooks of Richter and Jadassohn (which he considers “hardly distinguishable from Richter’s” apart from a stronger focus on chromatic harmony) continued “to be the standard harmony books almost everywhere that European classical music was studied through the rest of the century,” further arguing that “the fact that these books went into edition after edition is symptomatic of the dearth of new ideas, and the irrelevance that pedagogical theory was falling into.” Richterian harmony pedagogy was simply taken for granted as the standard in the theory discourse of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Richter’s approach held a dominant position in the discourse of Western music theory pedagogy in these decades, fixing (and thus limiting) the commonly held ideas of what music theory pedagogy was and could be. This Richterian hegemony—specifically the classroom teaching of written four-part harmony exercises accompanied with Roman numeral analysis—played a key role in the establishment of the paradigm of modern music theory pedagogy.

[5.6] Although influential in their own right, the other two volumes of Richter’s Praktische Studien did not receive the international recognition accorded to the harmony textbook, and were translated into fewer languages.(65) Thus, in many languages, only the harmony textbook was available. Even though all three books existed in several English translations, they seem not to have been issued as a series, thus effectively breaking the concept of a trilogy of textbooks explicit in the German editions since 1872. I will argue that the separation of the harmony textbook from the rest of Richter’s pedagogical framework has tainted his legacy in unfortunate ways. But despite this separation of his works, Richter nonetheless gained an international hegemonic position.

[5.7] Richter’s reception in Scandinavia is an interesting case in point. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, music theory discourse in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden was dominated by the Richterian framework for harmony pedagogy (Hvidtfelt Nielsen 2024; Utne-Reitan 2022a). Danish and Swedish editions of Richter’s harmony textbook were readily available in Scandinavia. Moreover, the most influential original harmony textbooks of the late nineteenth century in each country were adaptations of Richter (Bergenson 1899; Bondesen 1897; Lange 1897). All three books appeared at the very end of the century but nonetheless followed Richter’s model, which was then more than forty years old. The reception of the first Norwegian harmony textbook provides a window into Richter’s strong position in Scandinavia at the time. An explicit adaptation of Richter’s pedagogical approach, it was written in 1897 by Gustav Fredrik Lange (1861–1939). Its title translates as “Practical Harmony,” underlining the practical focus heralded by Richter. It appeared in several editions and remained the only Norwegian harmony textbook for a half-century.(66) Lange explains the benefits of Richter’s approach in the preface:

As one will see, I have largely used the method used in Richter’s well-known harmony textbook. Other methods have recently been tried, and several of these have their advantages. But I believe that with regard to the most difficult question, the voice leading, none of them leads as surely to the goal as the above-mentioned method. (Lange 1897, preface)

[5.8]. Lange follows Richter in the broad outlines: the book is concise, concentrates on teaching principles for good voice leading, contains as little speculative theory as possible, uses Weberian Roman numerals, and includes exercises in the form of given figured basses to be realized in four parts. The book is thus thoroughly Richterian and a typical example of how Richter’s approach was adopted outside of German-speaking territories. As with Richter, Lange’s great influence was partly secured by his position as a long-time teacher at the Oslo Conservatory, the country’s leading music school, established in 1883.

[5.9] A review of Lange’s book by Karl Svensen (1859–1932; see Svensen 1898) and Lange’s (1898) subsequent response reveal the extent of Richter’s influence. Indeed, the core of the debate was whether Lange deviated too much from Richter and whether the available Danish alternatives (either the translated editions or Bondesen’s Richter adaption) were, therefore, better.(67) The question was not if the harmony pedagogy should be Richterian but how Richterian it should be.(68) One key difference between Richter and Lange not raised in the debate was that the latter did not include a section comparable to Richter’s foreshadowing of counterpoint studies in the harmony textbook’s third part. In Richter’s works, these chapters had created a smooth transition from one domain to the other. In Lange’s book, harmony appeared as a completely separate discipline from counterpoint.(69) What had arguably been one of the greatest strengths of Richter’s own pedagogy was thus lacking in Lange’s work.

[5.10] Internationally, Richter’s pedagogical framework (or at least its core elements) retained a hegemonic position in several regions throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It attained and maintained this position through several factors. Most importantly, there was a market. As Riemann wrote in 1895, conservatories and music schools were “now shooting out of the earth like mushrooms” (Riemann 1994, 226). These institutions served a growing middle class of amateurs and aspiring professionals who sought musical education and thus needed textbooks. More generally, the nineteenth century was an age when “publications, readers, and writers proliferated as readerships rapidly expanded alongside the rapid growth of the reading public” (Watt 2020, 204). Compared to earlier periods in the history of music theory, there was a significantly larger international market to be filled, both within and outside of educational institutions. Richter was, however, not the only textbook author. There were many theory textbooks available,(70) so the question remains as to why his works became more successful than others.

[5.11] From the above discussions, we can sense several power-knowledge procedures at play in the discourse of Western music (theory) that helped secure Richter a hegemonic position. The first is connected to broader power structures in the nineteenth century, particularly those of

[5.12] Thompson (1980) argues that it was probably Richter’s practical approach as well as the brevity of the harmony book that made it so popular at the newly established North-American conservatories and music departments. He also acknowledges the significance of personal connections; several influential agents in the field of North-American music theory had studied with Richter in Leipzig (Thompson 1980, 3; see also Wasserloos 2004). The idea that music theory pedagogy should be practical training seems to have remained a central part of the power-knowledge regimes of music-theoretical discourse in the nineteenth century, and Richter’s methodically scaffolded, etude-like approach—working gradually and systematically from specific voice-leading issues and (if using all of his textbooks) toward fugue composition—was clear, rational, and easy to grasp. Most importantly, Richter’s textbooks (and his son’s additional volumes) offered exercises and solutions, making it ready-to-use and easy to implement at the many new conservatories.

[5.13] Thus, a Richterian hegemony in music theory discourse was made possible by a combination of the factors described above: a large market, German cultural preeminence, Richter’s institutional affiliations (including his many students), and the practical focus of his texts. But arguably the greatest strength of Richter’s approach—the smooth transition from harmony to counterpoint—is undermined when the harmony textbook is separated from the counterpoint and fugue textbooks. Nonetheless, Richter retained his authoritative status throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, and the core principles of his harmony book persisted as widespread, taken-for-granted notions in music theory discourse.

[5.14] Despite its longstanding and far-reaching success, the position of the Richterian framework was later challenged. Although the original German edition of the harmony textbook would long remain in print, its authoritative status was contested at the turn of the twentieth century. A 1907 survey showed that a wide range of textbooks were in use at the most influential German-speaking institutions, but Richter’s book was not among them (Fend 2005, 429). An important development at the turn of the century was, for instance, the increasing influence of Riemannian function theory.(71) Of course, Richter’s book was never the only textbook in use, and its elevated position was certainly contested before the early twentieth century. Rudolf Louis (1906, 431), for example, mentions theory pedagogy in Vienna (Sechter, Bruckner) and Munich (Rheinberger) as a “positive counterbalance” limiting the nineteenth-century Richterian hegemony. Although Richter’s name did not carry the same institutionally supported weight as before, it was still he who was targeted by early-twentieth-century theorists and textbook authors such as Schoenberg, Ergo, Louis, and Schenker when they argued for reforms in harmony pedagogy. While Schoenberg and Ergo (a disciple of Riemann) primarily critiqued Richter’s texts for their narrow and old-fashioned views on modulation (Holtmeier 2011, 4 and 9–10; Schoenberg 1978, 15 and 165), Louis (1906, 431) complained that Richter’s focus on realizing figured-bass harmonies reduced harmony training to a “completely primitive and purely mechanical work” rather than focusing on “the most important task of all harmony studies: to develop the student’s understanding of the meaning of harmonic relationships.” Schenker (1954, 177) singled out Richter as an example of everything wrong with then-current harmony textbooks, which “are all alike.” Thus, it seems clear that the idea of a Richterian hegemony remained strong in German-speaking countries during the early twentieth century.

[5.15] Schenker championed a clear separation of harmony (focusing only on the abstract concept of Stufen) and counterpoint (including all matters of voice leading). After discussing the unclear relationship between harmony and counterpoint in one of Richter’s constructed examples, he claims that “the whole book is based on such nonsense” (Schenker 1954, 176). However, as Michael F. Burdick (1977, 24) demonstrates, his Stufe concept “was not as original as Schenker would have us believe.” A precedent has been found in discussions of passing chords printed in several nineteenth-century textbooks, including Richter’s (see Example 10). Richard Cohn makes a similar point, claiming that “the seminal treatments, in the Lehrbücher of E.F. Richter (B1853) and Mayrberger (B1878), of passing chords

[5.16] To this day, the after-effects of the old Richterian hegemony are felt. Throughout the twentieth century, the growing focus on harmonic analysis—either with Roman numerals or post-Riemannian function symbols—created a harmony pedagogy with a “mania for naming and labeling chords” (Hyer 2011, 111), where harmony is presented from the perspective of “total verticalization” (Holtmeier 2011, 29). There is currently a movement to undo the “turn towards writing” effected by nineteenth-century theory teachers, returning to the practices of the older keyboard-based pedagogies. As part of this movement, the partimento resurgence of the last two decades has criticized the elevated position of Roman numerals, which dates back to Richter.(74)

[5.17] Given Richter’s central role in popularizing Roman numerals, it is not surprising that his name appears in recent critiques of the prevalence of Roman numerals in modern theory pedagogy. In these critiques, Richter’s popularization of Roman numerals is described as a turn to a pedagogy directed towards amateurs rather than professionals (see Gjerdingen 2021, 2023). Yet in fact, Richter primarily taught (and developed his method for) future professionals studying at a respected music school. Also, Ludwig Holtmeier (2012, 9) mentions the Leipzig theorists (Hauptmann, Richter, Jadassohn) as exceptions when presenting his historical analysis of a “hostile takeover” where “musical dilettantes,” rather than music professionals, gained major influence in German music theory. In his own summary, “many representative German theorists of harmony, such as Weber and Marx, were autodidactically trained music amateurs with only a rudimentary compositional and music-theoretical basic knowledge” (Holtmeier 2012, 25). But Richter was no amateur, even though he built on the work of Weber, and even though his works and particularly their reception contributed to the general situation criticized by recent scholars.

[5.18] Richter’s (to some extent undeserved) negative reputation has two primary causes. First, his critics’ focus on his popularization of Roman numeral analysis has overshadowed other key aspects of Richter’s pedagogy. Roman numeral analysis is just one dimension of his pedagogical framework—an additional conceptual tool in a harmony pedagogy largely reliant on the (written) realization of figured basses. Although the use of Roman numerals is significant, the aim of this pedagogy was never to write extensive Roman numeral analyses, but rather to teach voice leading in a practical and to-the-point manner within the context of a modern classroom setting. In Richter’s harmony textbook, one finds no exercises in performing Roman numeral analyses of excerpts from the musical literature. Secondly, and in line with the first point, Richter’s overall approach was focused strongly on counterpoint. Two of the three volumes of the Praktische Studien trilogy deal with counterpoint and contrapuntal forms. As outlined above, the harmony coursework was only the starting point, serving as preparation for the counterpoint instruction. The counterpoint and fugue textbooks did not get the same widespread international reception as the harmony textbook, implying that the latter in many places was separated from the former. The fact that later adoptions and adaptations increased the focus on Roman numeral analysis and more clearly separated harmony from counterpoint cannot be blamed on Richter, but these developments have nonetheless significantly tainted his legacy. My suggestion that Richter should not be blamed for some of the criticism leveled at his work does not imply that this pedagogy was without flaw, however. After all, Richter’s pedagogy can rightfully be criticized as “dry.”

[5.19] Today, there are broad calls to return to “practical” teaching methods, particularly keyboard-based systems. Indeed, modern theory textbooks drawing on the partimento tradition (e.g., Ijzerman 2018) have begun to appear. Somewhat paradoxically, Richter had the same aim: to adapt practical theory pedagogy for the modern classroom setting in a brief and to-the-point format. A key question in music theory pedagogy, then and now, is the definition of “practical.” Richter always explicitly intended his pedagogy to be practical and, by implication, anti-speculative; but his written approach was nonetheless very different from the earlier practical approaches, which emphasized non-written theory. The reasons for this broad turn in music theory pedagogy—which cannot be ascribed to Richter alone—are manifold: the modern institutionalization of music education, the Romantic notion of Genieästhetik, and the regulative work concept (Goehr 2007) all widened the gap between performer and composer. Although this (partly) explains the shift away from improvisatory and towards written approaches, it is something of a historical paradox that practical music theory pedagogy flourished in an age of Genieästhetik that emphasized genius, originality, and individuality (in the sense that many considered composition unlearnable), and saw several successful composers (Grieg included) attempting to dissociate themselves from their formal training (see Dahlhaus 1984, 116ff.; Holtmeier 2012, 10; Utne-Reitan 2021a, 84; 2022b, 81). Nonetheless, Richter remained firmly within the paradigm of practical theory and unequivocally aimed to teach compositional technique, not abstract theoretical concepts.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] Throughout this article, I have explored what characterized Richterian theory pedagogy and how it gained and maintained a hegemonic position in the discourse of Western music theory in the late nineteenth century. In doing so, I have focused on the workings of disciplinary power-knowledge in this discourse. The discussions have indicated that the Richterian dominance supported and benefited from a broader

Bjørnar Utne-Reitan

Mälardalen University

Academy of Music and Opera

Slottet 1, 722 11 Västerås, Sweden

bjornar.utne-reitan@mdu.se

Works Cited