Vocal Production, Mimesis, and Social Media in Bedroom Pop

Alyssa Barna and Caroline McLaughlin

KEYWORDS: voice, timbre, gender, bedroom pop, vocal production, physiology, mimesis

ABSTRACT: Bedroom pop, as a subgenre of indie pop, has recently grown rapidly in popularity. The primary characteristics of bedroom pop encompass the self- or home-production of musical material, digital production techniques, layering, limited instrumentation, and, most notably, the use of a stylized breathy, quiet vocal timbre that we call the “bedroom pop mixed voice.”

This article applies music theory and analysis, media and gender studies, and vocal science studies to two ends. First, we describe how the bedroom pop mixed voice is produced, offering both physical and anatomical definitions of it. Grounded in embodiment, mimesis, and physiology, we show how the bedroom pop mixed voice is used for stylistic and narrative purposes through the analysis of recent popular bedroom pop artists such as Billie Eilish, dodie, Lizzy McAlpine, and Olivia Rodrigo. Second, in tracing the use and propagation of the bedroom pop mixed voice through social media, we aim to discover bedroom pop’s social and cultural impact on Gen-Z music makers. Through the lenses of antiphony and mimicry (Shelley 2020, Cox 2016), we show how amateur performances and covers of bedroom pop songs replicate this vocal production style. These covers have proliferated through social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram, and they have influenced a new generation of (primarily female-identifying) singers (Wolfe 2012, Barna 2022).

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.1

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[0.1] Bedroom pop is a genre defined by location and sound. Bedroom pop artists—many of whom began musical pursuits under the age of 20—start their careers by producing their music within the four walls of their bedrooms. With their parents often in the next room, these musicians quietly perform to no one, producing music and uploading it to streaming services such as SoundCloud or Bandcamp. Bedroom pop harnesses the raw, intimate, and textured lo-fi sounds of the 1990s, but the genre creates these sounds through digital means, giving them new life in the modern era.(1) This has led to the development of a genre-defining vocal style marked by singing that is hushed and light, which evokes the ecology in which the music was created. The bedroom-as-studio is essential to understanding the intimacy behind bedroom pop as expressed in the lyrics and heard in the muted timbres and instrumentals. Bedroom pop artist mxmtoon notes, “Anyone can make music, and I think that is the ideology behind bedroom pop. Bedroom, it’s more of an idea, of a person sitting in a small space and using whatever resources you have to make songs that you’re proud of” (Roos 2020, [4]). Despite the intimacy of the music’s creation, its spread via social media (especially TikTok) has led to widespread popularity and viral musicking (Harper 2020).

[0.2] Who are the musicians of bedroom pop? Journalist Jenessa Williams states: “Defining bedroom pop is a slippery entity. As journalistic shorthand, it’s been flung around for decades as a flattering way to dress up homespun demos and slacker aesthetics, recalling middle-aged white men noodling aimlessly for their ‘art’” (Williams 2020, [2]). The reference to “middle-aged white men noodling”is far from the reality of the genre in the twenty-first century. Indeed, the genre has become a home for marginalized voices, particularly those of women, queer, and BIPOC artists. As Williams notes, “To dismiss bedroom pop as merely another flash in the pan is to disregard the power it has to elevate marginalised voices. The lack of gatekeepers in this self-shaped world is particularly advantageous for young artists of colour or non-binary identity, resisting boundaries faster than the music industry can keep up”(Williams 2020, [5]).

[0.3] Though the term “bedroom pop” has been used for decades, the burgeoning interest in home-/self-produced music was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the absence of live performance and collaborative musical and studio experience, artists turned towards writing and producing music within the confines of their homes. Although the feedback and resonance of live audiences was lost, the accessibility of technologies and platforms for music circulation was unmatched, allowing bedroom pop to flourish for people of many identities and backgrounds. The origins of the genre, and the popularity it garnered during the pandemic, have created a sense of authentic intimacy. Listeners are hearing an artist’s minimally filtered voice and, when videos are included, they gain an up-close-and-personal view into the artist’s daily life at home.

[0.4] Bedroom pop’s most characteristic features are intimacy and quietness, which generally arise from three techniques: 1) self- or home-production of musical material, 2) limited instrumentation, and 3) consistent use of breathy, quiet vocal delivery. This vocal timbre is a result of a manipulation of the mixed voice that we call the “bedroom pop mixed voice.” In this article, we describe how the bedroom pop mixed voice is produced in the voice by situating it in the context of other extant and well-defined vocal production techniques. We discuss the multifaceted approaches to analyzing vocal timbre to define our methodology and present the physical and anatomical definitions of the bedroom pop mixed voice. Using a methodology grounded in embodiment, mimesis, and physiology, we show how the bedroom pop mixed voice is used for stylistic and narrative purposes through the analysis of recent popular bedroom pop artists such as Billie Eilish, dodie, Lizzy McAlpine, and Olivia Rodrigo.(2)

[0.5] The final section of the article describes the use and propagation of the bedroom pop mixed voice through social media. Through the lenses of antiphony and mimicry (Shelley 2020; Cox 2011; 2016), we show how amateur performances and covers of bedroom pop songs replicate this vocal production style, which has proliferated through platforms like TikTok and Instagram and influenced a new generation of (primarily female-identifying) singers (Wolfe 2012, Barna 2022). The bedroom pop mixed voice has become such an indelible auditory artifact in the musical style that it often appears with little digital manipulation or suppression in studio-produced music by bedroom pop artists. The rapt and viral attention commanded by social media and its musical platform has allowed the bedroom pop mixed voice to spread rapidly via replication and repetition, contributing to the remaking and reshaping of the timbre and style of the genre online. This article combines music theory and analysis, media and gender studies, and vocal science to better define the genre of bedroom pop and discover its social and cultural impacts on Gen-Z music makers.

1. Before Bedroom Pop

[1.1] An antecedent for the vocal intimacy and production style of bedroom pop can be found in the pop singing trend dubbed “singing in cursive.” According to journalist Jumi Akinfenwa, this term was “first coined by Twitter user @TRACKDROPPA back in 2009, writing, ‘Voice so smooth its [sic] like I’m singing in cursive. . .’ The term applied to singers such as Corinne Bailey Rae and Amy Winehouse, whose nostalgic but modern combination of jazz and vocal fry dominated the late ’00s and has dominated pop music over the years since (e.g. Sia, Lorde, Shawn Mendes and Billie Eilish)” (Akinfenwa 2020, [2]). Also termed the “indie (girl) voice,” cursive singing made its way into mainstream pop production beginning in the 2010s, as heard in the music of artists like Bebe Rexha, Of Monsters and Men, MisterWives, and Halsey (Burgos 2021). The singing styles of singing in cursive and the bedroom pop mixed voice are culturally related by their proximity in time and style, the prevalence and spread of the style on online platforms, and the female-coded implications of the vocal techniques.(3)

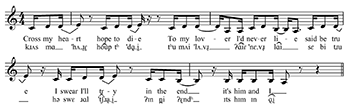

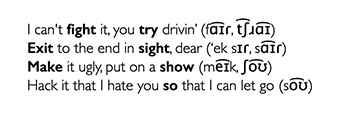

Example 1. G-Eazy featuring Halsey, “Him and I,” 0:00–0:11

(click to enlarge and listen)

[1.2] Halsey’s particular brand of singing in cursive best exemplifies the strongest trait of the style: an exaggerated diphthongization of vowel sounds. While diphthongs occur naturally in spoken and sung English, the process present in cursive singing involves breaking the present monophthong or diphthong into two separate vowel sounds, with emphasis often placed on the second. This process—where a single vowel sound is made into two (also called vowel breaking)—is sometimes referred to by its critics as sounding intoxicated, with the artist affecting slurred speech. On “Him & I” (2017), Halsey, as a featured artist on G-Eazy’s track, sings each chorus in an exemplary performance of singing in cursive; the opening chorus is shown in Example 1. In this song, the vocal sounds close-miked, where the listener can very distinctly hear Halsey sing overemphasized vowels as well as her breathing. Halsey overemphasizes the final words of phrases, sometimes rhyming, like “die,” “lie,” and “I.” Each of these words is treated slightly differently, depending on the setting of the text: words containing diphthongs (or that have been diphthongized) that are sung on a descending note change or only one note (I, lie, I’d, and hope) are not broken into two distinct vowel sounds, while those sung on an ascending note change (heart, die, and try) are. IPA transcriptions are written beneath the lyrics to demonstrate this effect, with tie bars above the unbroken diphthongs, as seen in the transcription for “I” as “ɑ͡i.” Other included diacritics mark other aspects indicative of cursive singing.(3) Halsey engages with the growing popularity of the bedroom pop sound in her more recent music—still utilizing overemphasized and extended vowels. Writing about Manic, Halsey’s 2020 release, Stephanie Burt (2020, 5–6) notes that the album is a “sparkling example of late-teen and quarter-life crisis bedroom-pop angst, the shiny-enough-for-radio version of a generation that crushed up Ritalin to earn the degrees that will let them, someday, quit driving for Lyft. ‘clementine,’ with its bedroom-pop instrumentation and its wearable angst, could almost pass for Billie Eilish, latterly taken as a voice of that same generation.”(4) We analyze cursive singing as an earlier version of bedroom pop singing style, thus later releases from Halsey (like Manic) transition into the new medium and style, and Burt suggests this bridge here.

[1.3] Beyond exaggerated diphthongization, Karen Burgos of Ace Linguist explains that another prominent feature of singing in cursive is the lack of aspiration (2021). When consonants lack aspiration, they sound “soft”—Burgos likens cursive singing to the breathy tone and unaspirated consonants of bossa nova singer Astrud Gilberto. However, as seen in Example 1, some of the aspirated consonants persist, and other consonants, like the /d/ in “end” are assigned aspiration contributing to the overall sense of breathiness. Other traits common to cursive singing include softening final consonants in words (like “forever,” akin to a British “r”), altering /s/ sounds into “sh” sounds, vocal fry, and retracting the tongue to create a smaller pharyngeal space (Jones et al. 2017).(5) The performance of soft consonants, breathy tone, and irregular pronunciation in singing in cursive invites listeners closer to the artist as we hear them manipulating their voice, and serves as a precursor to the intensity of the breathiness and intimacy produced and heard in the bedroom pop mixed voice.

[1.4] The gender of the singer is relevant to the analysis of both singing in cursive and the bedroom pop mixed voice. Singing in cursive was often critiqued in the media, with commentary like “It sounds to me like a digitized yodel; [music writer Reggie] Ugwu described it as ‘hipster riffs on Alanis Morissette’ (Ugwu 2015, [4]). Either way, Halsey is one of its most chronic practitioners, straining to coat each of her vowels in a jewel-toned sheen” (Zoladz 2017, [7]). Implicit in many critiques is gender: even if it’s described as the “indie-pop voice,” it is coded as a critique of the indie girl voice given that the strongest and most numerous examples of the style are sung by female-coded voices. Race and class are relevant in this discussion as well, as both singing in cursive and the bedroom pop mixed voice prominently feature white-presenting singers. For example, in her discussion of depression and white femininity in the music of Billie Eilish, Jessica A. Holmes calls attention to the intersection of race, digital culture, depression, and music, noting that “virtual content also calls valuable attention to the implicit whiteness of her image and fan base in ways that inadvertently point to the racial disparities underlying the cultural logics of depression more broadly, and its persistent representation as a predominantly white, class-bound affliction” (2023, 792). All women may be subject to specific critiques of the gendered perception of their voices, but white women are inevitably afforded privilege that women of color are not: “if Eilish’s claim to depression is subject to ongoing adultism and misogyny, her whiteness also affords an implicit privilege” (Holmes 2023, 806).

[1.5] Cursive singing directly influenced the bedroom pop mixed voice. When practicing and mimicking popular indie songs at home, often utilizing the cursive singing technique, many amateur singers began to develop a style and technique of their own that would eventually become more clearly defined as the bedroom pop mixed voice. As an extension of ethnographic work in (pre-)teen girlhood and music listening habits in the home (Davies 2013, Baker 2004), we hypothesize that Gen-Z teens or young adults—sharing a space with others—practice in their bedrooms and attempt to sing quietly enough to not be heard beyond their four walls. They may never perform for anyone else before uploading, and only have their own ears to rely on for dictating the quality of the end result. The rise of pop made at home also highlights the bedroom as a gendered social space, where women and girls confront both opportunities and challenges making music at home (Barna 2022).

2. Vocal Physiology

[2.1] Analyzing vocals in bedroom pop mix relies on understanding vocal physiology of both external and internal cues. This methodology is paired with aural analysis of timbral quality and phonation, which provides the fullest picture of the creation and propagation of the bedroom pop voice. Visuals (both still pictures and video) will be shown to illustrate the external mechanisms of vocal physiology and physical performance. These images also assist the analyst in the mimetic methodology of studying and replicating specific vocal production styles.

[2.2] Bedroom-pop vocal physiology can be distinguished from other pop styles primarily by the vocalist’s breathy timbre in the middle to higher range. The most common techniques used to achieve higher ranges are called belting, falsetto, and mix.(6) Singers use these three styles when singing in their higher register, and other techniques, like whistle tone, are occasionally used for embellishment. In their falsetto or mixed voice, the timbre used by bedroom pop singers is typically breathy (and belting is rare), as it only needs to fill a small space and can be amplified by production equipment. Creating this timbre, then, involves manipulating and combining elements from each of the aforementioned styles of vocal physiology to create the unique sound that has become a genre staple. In this section, we analyze the physical techniques used in chest and head voice and examine the vocal production techniques of the mixed voice.

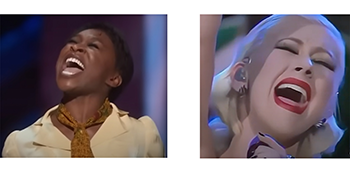

Example 2. Cynthia Erivo, belting during “I’m Here” (from The Color Purple); Christina Aguilera, belting during the National Anthem (NBA Finals 2010)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.3] Belting remains one of the most common vocal techniques used in modern popular music. An emulation of the natural chest voice resonance present in the lower-register speaking voice, this style of singing extends the placement and sound into higher registers. This results in a timbre that is often described as bright and nasal. In belting, “The vocal folds are pressed firmly together and the vocalis muscles remain contracted into higher pitches, keeping the vocal folds thickened” (Harrison and Watson 2020, 104); this firm contraction of vocal folds allows for a more amplified chest voice timbre at a higher register. In the chest voice, belting creates sympathetic vibration in the chest and sternum in the lower range, and in the “mask,”(7) which contributes to the more nasal sound in the higher range (Heidemann 2016, [3.22]). Belting also raises the larynx and narrows the pharynx, using a “megaphone” mouth formation with a wide, open mouth with the corners of the lips pulled back (Heidemann 2016, [3.20]). The mouth shape creates little resonance within the mouth, but ensures more space for the sound to emit. Example 2 provides visual and aural displays of a belted performance as shown in the exterior (face of the performer).

Example 3. Joni Mitchell using head voice in “A Case of You”; Kathleen Battle using head voice in “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.4] In contrast, falsetto and head voice (M2) are the vocal physiology methods preferred in classical vocal technique to perform the higher range for (typically) female-coded vocal types like sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, altos, and countertenors—these techniques are typically used in operatic singing. This style of vocalization uses a lower larynx position than used in belting, and a higher soft palate to produce a sound that is often described as soft, light, and seemingly effortless in tone. The name “head voice” is attributed because the performance of this style places most sympathetic resonance in the head (Heidemann 2016, [3.24]). Producing head voice involves the use of the inverted megaphone shape of the mouth (Titze et al. 2011, 562). This formation allows the sound to resonate in the mouth and create a richer tone before it leaves the lips, which further focus the sound due to their more rounded shape and smaller point of exit. Example 3 provides visual and aural displays of a head voice performance as shown in the exterior (face of the performer).

[2.5] Between these two styles occurs the “mixed voice” (or “the mix”), which is the style most frequently heard in the bedroom pop genre.(8) In university and professional study, the mix is taught most frequently as part of Contemporary Commercial Music (CCM) training.(9) As a perceptual blend of head and chest voice, Kochis-Jennings et al. study the mixed voice in commercially trained singers and divide it into “chestmix” (perceptually and acoustically closer to chest voice) and “headmix” (perceptually and acoustically closer to head voice). Results show that “unlike chest and falsetto, which do not appear to require training, the singers’ ability to produce chestmix or headmix appeared to be related to type of singing training. In general, those with commercial singing training were less likely to produce headmix, whereas those with classical singing training were less likely to produce chestmix” (2012, 190). They also determined that there is greater engagement of the thyroarytenoid (TA) muscles and increased adduction of the vocal processes (VP) in chestmix than in headmix. “

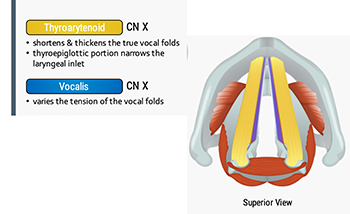

Example 4. Thyroarytenoid and vocalis muscles

(click to enlarge)

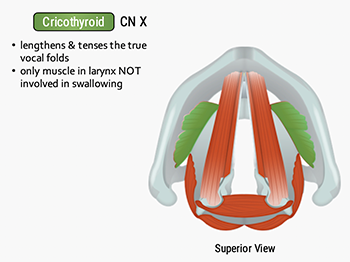

Example 5. Cricothyroid muscles

(click to enlarge)

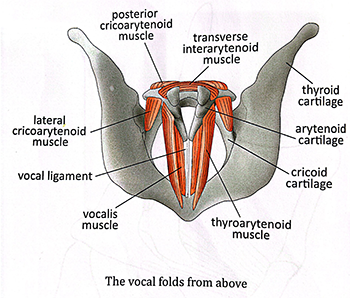

[2.6] Raising pitch, typically through ascending melodic lines, is essential to hearing the bedroom pop mixed voice, and thus an understanding of the anatomical process for its production in mixed voice is important. The mix is created by a coordinated effort between the thyroarytenoid muscles (including the vocalis muscles) and cricothyroid muscles, which lengthen and tighten the vocal folds to change pitch. The mixed voice, lying between M1, chest voice, and M2, head voice, requires a careful balance between these musculatures.(10) As Malde et al. note: “Between the chest voice and head voice, there is a part of the range where the contraction of the thyroarytenoids and cricothyroids is more or less equal. Because this register combines the color elements of chest and head voice, it is called mixed voice” (2020, 153). To raise the pitch through the mix, the cricothyroids take over and they “pull the thyroid cartilage down and forward on its hinge, which increases the distance between the arytenoids and the thyroid notch (the laryngeal prominence), thereby lengthening and tightening the vocal folds; this causes them to vibrate faster, thus raising pitch,” (Lions Voice Clinic, § 2, [4]). Example 4 shows the thyroarytenoids and vocalis, and Example 5 highlights the cricothyroid muscles.(11)

[2.7] While the standard mix brings a stronger, brighter tone to the mid and higher range, bedroom pop artists focus on highlighting softer, breathier tones in the bedroom pop mixed voice. Though this style of vocal production functions fundamentally like the standard mix in its combination of techniques, its specific usage and defining characteristics have created a standard sound we refer to as the bedroom pop mixed voice. As we will show through analysis, bedroom pop artists frequently utilize chest voice in their lower range, then use the bedroom pop mixed voice to transition to higher pitches. Occasionally they will utilize head voice, often with the bedroom pop mixed voice to navigate the transition up to this register. The use of the bedroom pop mixed voice is an artistic choice to create smooth transitions between vocal registers while imparting a light and breathy tone.

Video Example 1. dodie and @lynlapid perform a duet on TikTok using external vibrato

(click to watch video)

[2.8] Another common technique used in the production of the bedroom pop mixed voice is external vibrato.(12) Singers often introduce external vibrato at the ends of phrases, shaking their head as they produce subtle vibration. This behavior is likely observed and recreated by singers as a strictly learned behavior, and it has a clear effect on the resonance the singer feels and hears, especially when amplified by a microphone. Typically, internal vibrato is produced through fluctuations of a collection of intrinsic and extrinsic laryngeal muscles, affecting both the vibration of the vocal folds and “oscillation in the height of the larynx which occurs in phase with the vibrato” (Harrison and Watson 2020, 111). Other aspects of the vocal tract may also play a role in producing vibrato, including “the tongue, epiglottis, soft palate and pharyngeal wall” (Harrison and Watson 2020, 111). However, the external head shaking technique that many bedroom pop musicians utilize does not actually create vibrato unless it is used in combination with internal vibrato—the external vibrato mimics its effect. By shaking one’s head, the sound produced will appear to fluctuate like vibrato in the ears of the singer; this will be most audible when the singer is already producing internal vibrato but will not be audible to anyone but the singer when occurring as a head shaking technique alone.(13) This can be seen in Video Example 1, where musician dodie performs a duet on Tiktok with user @lynlapid. Anticipating Lyn’s use of external vibrato (as she’s seen the video before creating the duet) dodie preemptively shakes her head before she begins. Then, both singers subtly shake their heads at the end of phrases, or when performing an ascending leap into the bedroom pop mixed voice register (on “know” and “closed,” for Lyn). This effect can then be emphasized to an audience through the use of a microphone. By shaking the head while singing into a microphone, the sound will be amplified somewhat inconsistently, again mimicking and supplementing the effect of vibrato more recognizable to the audience with little effort from the singer.

3. Analyzing Vocal Timbre and the Bedroom Pop Mixed Voice

[3.1] Music theorists have developed various approaches to vocal analysis and the study of timbre over the last decade within music studies. These studies variously incorporate computational approaches, spectrographic analysis, perceptual and empirical studies, embodiment and space, and the analysis of meaning and identity. In this section, we discuss the core texts that aid in the identification and analysis of the bedroom pop mixed voice; these sources also unlock the interpretive potential of bedroom pop as it relates to gender, age, and identity.

Embodied Analysis

[3.2] Kate Heidemann’s Four-Part Embodied Comprehension of vocal timbre conceptualizes the perceived vocal production to be classified by four elements: the movement of true vocal folds, position of vocal tract, location of sympathetic vibration, and degree of breath support and body engagement (2016, [3.2–3.3]). Each of these can be determined through listening, observing, and engaging mimetically with this vocal style—the analyst is encouraged to actively imitate the sounds they hear, noting the activation of muscles, tension and relaxation in muscles, and the feeling of the sounds produced. For example, in her discussion of breathy phonation, Heidemann states that “the range of expressive possibility presented by breathy vocal timbre—e.g. relaxation, intimacy, or sensuality—illustrates the distance between the basic description of a vocal timbre and the explanation of its impact in the context of a popular song” (2016, [3.6]). After imitating this phonation style in her own voice, Heidemann attributes this to a sense of muscular relaxation—an effect that we are able to replicate in our analysis of the bedroom pop voices.(14) Heidemann acknowledges the personal and subjective nature of this style of analysis but emphasizes the importance of an embodied perspective—a view that is grounded in Arnie Cox’s mimetic hypothesis (2016). Cox and Heidemann’s methodologies do not account for the influence and use of production and technology, so these factors must be considered separately (see the discussion of Malawey below). The analysts rely on their embodied experience, as they are the primary listeners. We authors position ourselves as trained musicians and cisgender women, a bias which we acknowledge may be evident in the analysis.(15)

Example 6. Forms of MMI (after Cox 2011, 2016)

(click to enlarge)

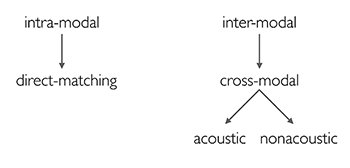

[3.3] To theorize how amateurs imitate and replicate the bedroom pop mixed voice online, Cox’s mimetic hypothesis allows us to connect our musical responses to physical responses in the body as it relates to imitation and motor imagery. Cox defines two types of mimesis, or imitation, that together comprise the mimetic hypothesis: mimetic motor action (MMA) and mimetic motor imagery (MMI). MMA is overt and often intentional (Cox gives the examples of playing air guitar or performing karaoke) (2016, 20–21). MMI comprises covert and imitative imagined actions, and these images “are in some respects the most significant in the construction of musical meaning” (12). Assuming that using the bedroom pop mix is a subconscious decision for most singers (and it would be an impossible task to compile data to demonstrate intention), our method focuses primarily on MMI. Example 6 shows Cox’s forms of MMI (45).

[3.4] In the application of the mimetic hypothesis to bedroom pop, Cox’s method asks us to use inter-modal/cross-modal MMI, both acoustically and non-acoustically. When singers use the bedroom pop mixed voice both visually and aurally, the performer creates cross-modal MMI. It is possible to engage and participate with musical content on social media through only intra-modal MMI as well—if they produce aural or visual cues of the bedroom pop mixed voice, but not both. In the analyses included here and in Section 5 below, we replicate the vocal examples with our own instrument—acoustic cross-modal MMI—and pay attention to external facial cues of vocal physiology—nonacoustic cross-modal MMI—to imagine and reproduce these, too.

Timbral Analysis

[3.5] In her in-depth study of the popular singing voice, Victoria Malawey (2020) examines the role of quality, technology, identity, and the body in vocal delivery of popular song. Of particular use to analyzing voice in bedroom pop is her discussion of vocal quality, the use of spectrograms as an analytical tool, and the interpretation of meaning and identity conveyed by the vocal analysis. For an example related to bedroom pop production, Malawey ties together perception of the recording with technological mediation by showing that “Recording distance, or the placement of the singer in relationship to the microphone, impacts how listeners imagine spatial placement of the singer and perceive the level of intimacy” (2020, 136). Several analyses that follow refer to the close proximity of the microphone, which imbues a sense of intimacy between the bedroom pop performer and the listener. In versions of bedroom pop songs posted to social media (primarily YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram), this closeness is visually mimicked by the video, which shows an isolated performer facing the camera in very close proximity, even when a microphone is not visible.

[3.6] The technology and production style in bedroom pop tends towards a dry sound, defined on Malawey’s continuum of technological processes as “natural,” “organic,” or with “more subtle mediation” (2020, 128). The presence of audible breathing, for example, suggests a drier production, and we read this dry and bare style as inviting intimacy and vulnerability. Technological meditation is downplayed in the bedroom pop genre because of the DIY aesthetic, but as Malawey (145) notes, all recorded sound is technologically mediated. We can never truly replicate the exact production style used by the artists in our analysis; attention to proximity, dryness, and placement will allow us to support claims of closeness and intimacy.

[3.7] Blending the concepts of embodied analysis and the study of meaning and identity vocal timbre, Nina Sun Eidsheim’s method of “critical performance practice” aids in the comparison and analysis of contrasting performances by various singers. This method “offers a tool that allows tracking between, among, and within measurable, symbolic, and articulated (or performative) modes

Video Example 2. Billie Eilish and FINNEAS perform “Everything I Wanted” (NPR Tiny Desk Concert, 2020)

(click to watch video)

Example 7. Lyrics to the chorus of “Everything I Wanted”

(click to enlarge)

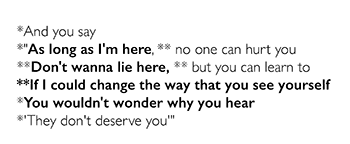

[3.8] Let’s take a moment to examine how these methodologies aid in analysis of the bedroom pop mixed voice. Listen to Video Example 2, featuring Billie Eilish (accompanied by her brother and producer FINNEAS) singing “Everything I Wanted.” The breathy tone used by Eilish in her upper register is accented by quick inhalations audible due to the close microphone position. As shown in Example 7, these breaths are marked with asterisks (* for a quick breath and ** for a longer breath) and create subtle yet integral paralinguistic features that mark phrases (Malawey 2020, 121). Her voice alternates between use of the bedroom pop mix and chest voice styles on each line of the text (see mixed voice lines in bold and chest voice lines in plain font).

[3.9] As analysts, when we listen to Eilish’s style of singing and use Heidemann’s embodied approach, the most obvious vocal quality is the breathy, light tone. Bedroom pop vocals are marked by soft diction that accentuates the sibilant sounds (also known as fricative consonant sounds, such as /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, and /Ʒ/), and the mouth sounds that accompany the “close miked” sound. These sounds prevent sharp punctuations in the melodic line and establish the whispered quality; they also permit the singer to hold and sustain various notes and words without maintaining a strong resonance in the chambers above the vocal folds. The de-emphasis of consonant sounds is reminiscent of the emphasis of vowel sounds (via diphthongization) heard in the singing-in-cursive style, and here creates a sense of reduced clarity, establishing the contrast heard in “Everything I Wanted” between the lines that are performed in the bedroom pop mixed voice and those performed in the chest voice. In “Everything I Wanted,” you can hear slight deviation into the standard mix on the higher range of the fourth line of the excerpt, on the words “way that you see yourself,” which are marked by the greater sense of clarity and resonance in the vocals and depart from the breathier tone of the bedroom pop mix mixed voice. The diction, resonance, volume, and miking choices create a sense of intimacy and introspection (Malawey 2020, 136). Eilish invites us into her innermost monologue and personal space by revealing her breathing.

Example 8. The Phonatory Gap present in vocal anatomy (Reproduced with permission from Harrison and Watson 2020, 64)

(click to enlarge)

[3.10] Anatomically, breathy vocals can be generated in two ways due to air escaping through the separated vocal folds as a result of a phonatory gap. The gap begins when the cricoid cartilage moves backwards, causing the arytenoid cartilages to slide. The interarytenoid muscle in the back then activates during this transition; if it does not, then the gap appears, and the tone becomes breathy as air escapes past the folds. A phonatory gap can occur when the lateral cricothyroid muscles remain too loose, creating a gap in the folds. Example 8 shows an anatomical diagram of the larynx and the aforementioned cartilages and muscles that could create a phonatory gap.

[3.11] As the bedroom pop mixed voice occurs in the same general range as the standard mix, it mimics its placement. The sound is significantly darker than the standard mix, however, and maintains a breathier tone, indicating that the resonance does not occur in exactly the same manner. While the sympathetic vibrations can still be felt in the mask and head, they are reduced, and more tension can be felt in the larynx. Despite this tension, there is also an overall reduction in the “body engagement” used to produce the sound, and a lower level of pressure used to expel air, which again contributes to that breathier tone (Heidemann 2016, [3.27]).

Register and Facial Expression

[3.12] In addition to the hallmark physiology and timbre of the bedroom pop mixed voice, the register and contour of vocal lines is essential to hearing and analyzing the vocal type. The young, predominantly female-coded voices that use the bedroom pop mixed voice often used it in vocal lines that ascend in contour from the chest voice, as has been discussed by voice scientist Christian Herbst (2021). These artists are quite literally working through hysteresis of their passaggio zone in full view of their audience, and so the “middle” of the mix has become a stylistic feature rather than a bug. The ascent is yet another marker of vulnerability, as this is a difficult transition to make in the voice that can lead to a vocal break or lack of clarity.

Example 9. Bedroom pop mixed voice mouth shapes as used by Billie Eilish (singing “idontwannabeyouanymore” and Olivia Rodrigo (singing “drivers license”)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.13] Internal physiology is essential to understanding how vocal types are created in the body, but externally visible aspects also contribute to the production of specific vocal sounds. The lips and cheeks, for example, can be manipulated (consciously or not) by the vocalist because of modifications to the internal anatomical structures. It is common to see cheeks, lips, or even eyebrows aid in vocal production (and/or used simply for expressive effect). Notice in Example 9 how vocalists Billie Eilish and Olivia Rodrigo raise their cheekbones, nose, and/or upper lip—they are doing so while performing an ascending melodic line through the bedroom pop mixed voice. This external cue acts as a clue to be used in tandem with aural analysis to detect the use of the bedroom pop mixed voice and analyze its expressive and musical purpose.

[3.14] Facial expressions and visible cues can indicate the bedroom pop mixed voice, and they have a relationship with internal mechanisms of vocal physiology. The mouth shape involves a closed-mouth grimace displaying at least the top row of teeth and the corners of the lips retracted, often only on one side. This indicates the tension along the vocal tract used to restrict and manipulate the sound. This tension can further impact the breathy quality of the vocals created, but it likely has the greatest effect on the singer’s own perception of their tone. As the production of this tone utilizes a nearly closed mouth with the teeth exposed, the chamber inside the mouth creates a more enclosed space where the sound will resonate through the body, traveling to one’s own ears through the head rather than only projected outwards. This creates a sound even more resonant to the individual singing than those listening, indicative of its development as a style born from singing to oneself.

[3.15] External cues are also essential to the transmission of the bedroom pop mixed vocal style from artists to amateurs because they are a readily apparent part of the performance. When amateurs and fans take to social media to listen to—and, importantly, watch—videos of their favorite vocalists, they may quickly adopt the practice of using external facial cues in attempts to sing in a similar style because it is so visually striking. Upon finding the style so easy to mimic and execute sonorously to their own ears, amateurs will continue to use it as an everyday singing practice. The mimetic and cultural engagement with this vocal style will be discussed in the final section of the article.

4. Analysis

[4.1] English artist dodie’s origin story as a musician encapsulates the ideology of bedroom pop. An early adopter of YouTube in 2007, dodie began recording and posting music as a teen in 2011. Her music is now released through a label (The Orchard), but she continues to upload videos to YouTube and other forms of social media, including videos branded as “bedroom demos.” The following analysis examines the bedroom demo version of “hot mess,” the titular track from her 2022 EP.(18) The song features dodie performing solo at home, accompanying herself on guitar and layered clarinet, with a choir of overdubbed dodies proving vocal harmonies.

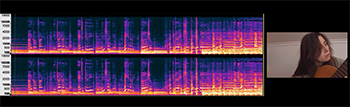

Video Example 3. Spectrogram and live video of dodie, “Hot Mess,” final chorus and outro

(click to watch video)

Example 10. Lyrics to the chorus of “hot mess”

(click to enlarge)

[4.2] The entire vocal performance is hushed and uses the bedroom pop mixed voice on and off, especially in ascending melodic lines and at the end of phrases. One particular use of the bedroom pop mixed voice is shown in Video Example 3, which features a quiet chorus section following the bridge (beginning at 2:15 in the full video). This section in particular demonstrates the bedroom pop mixed voice used in connection with several different consonant sounds (fricative, plosive, and nasal), as shown in the lyrics in Example 10. The bedroom pop mixed voice comes to the fore in this excerpt because it is nearly unaccompanied—the breathiness is a feature not obscured by background vocal harmonies or layered instrumentals, which seem to encourage a more full-voiced (specifically, chest voice) performance from dodie to rise above the texture. In the video, the spectrogram illuminates the articulation of these sounds. Each voiceless consonant creates a band on the y-axis, corresponding to bolded words in Example 10. The consonants also create a brief moment of visual static, emphasized aurally through the breathiness of the bedroom pop mixed voice.(19) Amplitude noise complements the breathy tone of the bedroom pop mixed voice used in the excerpt. The ensuing postchorus uses predominantly chest voice, but dodie leaps repeatedly into a higher register on the final word, “let me let GO,” placing the word and sound in her head voice. The articulation of the consonants in the chorus breaks the narrative of constant repetition (she sings in the verse, “Why am I so alright to do it again and again?”) (Malawey 2020, 87). The jagged melodic line of the chorus, sung with these accented consonants (confirmed through an embodied analysis à la Heidemann), creates prosodic gymnastics that reflect dodie’s fraying mental state.

Example 11. The word “sight,” performed by dodie (2:23 from “hot mess - original song | bedroom demo”)

(click to enlarge)

[4.3] Visually, dodie is seen manipulating external features as part of her execution of bedroom pop mixed voice: Example 11 shows a screenshot of dodie saying “sight” with raised eyebrows, cheekbones, and mouth shape of the sibilant /s/ sound. Sibilants are emphasized in the bedroom pop mixed voice because they rush air towards the teeth, creating and complementing the exposed teeth and retracted lips frequently used as external features of the mix. As a fricative, this consonant creates a high-frequency noise in the spectrogram shown in Video Example 3, like the other fricatives found in the chorus. The presentation of this song—as a “bedroom demo” released on YouTube—invites mimetic engagement from viewers. Mimetically analyzing the song requires some discomfort and effort to create the phonation she performs here. With dodie pictured extremely close to the camera (implying close proximity to the microphone as well), this allows an intimate setting to support the lyrical narrative that she wants to break from complacency.

[4.4] An early song from dodie, “She” is sung in a similarly hushed and quiet tone.(20) Recorded in her bedroom, this song was first released on YouTube in 2014, when dodie was 19. The starkest use of the bedroom pop mixed voice can be found on the title lyric. The chorus follows the four-phrase statement–restatement–departure–conclusion (SRDC) form (Everett 1999, 16), wherein the statement, restatement, and conclusion all begin with the sibilant /sh/ sound of the word “she” [ʃiː]. The range of the melody starts high, descending into the chest voice at the end of the phrase. The chorus’s conclusion inserts a nearly five-beat rest after “she,” drawing out the word and placing narrative emphasis on the meaning of the pronoun. The breath escaping via the phonatory gap in dodie’s voice, which uses a very lax phonation, emphasizes this sense of length and longing by creating an aural sigh sound.(21)

[4.5] In all, the wistful, longing voice heard on “She” utilizes the bedroom pop mixed voice as part of the narrative for a coming-out story, where dodie shares her story of falling in love with a girl shortly before the artist came out as bisexual. In various live re-recordings of “She” from the last nine years—still predominantly recorded in a home or bedroom setting—dodie’s voice becomes richer over time as her voice matures. Significantly, these re-recordings show that dodie has grown beyond her teenage bedroom; as listeners imitate the shifting vocal style, we, too, age with dodie. As the bedroom pop mixed voice acts as a transitory mechanism for singers between chest and head voices (why we often hear it used in ascending melodic lines), dodie continues to use the style to express retrospection and youth.

[4.6] The earlier works of dodie present an amateur musician’s beginning, incorporating simple accompaniment alongside her soft vocals. Her later releases often incorporate more orchestral accompaniment, intricate countermelodies, harmonies, and varied timbres. Like “She,” dodie’s song “When” demonstrates this development through several re-recordings. “When” originally premiered as a live recording on her debut EP Intertwined (2016). dodie re-recorded it for her debut album Build a Problem (2021). The song describes the feelings of regret accompanied with aging, and it recognizes a strong desire to hold on and return to the nostalgia and whimsy of the past rather than live in the present, a common theme throughout many of her pieces. “When-Live” (2016) promotes an overall more youthful sound, with the young quality of dodie’s voice accentuated further by the use of speech-like diction.(22)

Example 12. External vocal production by dodie on “When” 2016 (12a) and 2023 (12b)

(click to enlarge)

[4.7] An embodied Hedeimannian analytical perspective tells us that each verse of “When” is performed primarily in the chest voice (e.g. 0:15, 1:21 of “When-Live”), with the vocal line transitioning into the mixed voice consistently only in the higher range of the chorus (e.g. 0:51, 1:55 of “When-Live”). Clipped consonants and breathy releases emphasize the lyrics, making her sound slightly uncertain and nervous, illustrating her vulnerability in the voice and lyrics. This prosody can also be experienced visually in the accompanying live video. In this video, dodie appears to chew each individual word, often displaying gritted teeth and a wider mouth cavity, as seen in Example 12a. This tense vocal physiology presents another view of the narrative nostalgia and regret: dodie is braced and stiffened towards change and aging. When we mimetically engage with this song, the physicality of the phonation and the enunciation and prosody both evoke a sense of chest tension within us and direct our attention to how the tongue works to produce the consonant articulation. During embodied analysis, cheekbones elevate and an open mouth has visible top teeth.

[4.8] “When-Live2016”(2016) shows an early form of bedroom pop, particularly due to its clear use of dodie’s bedroom as a studio, and the later re-recording demonstrates how the style has continued to develop into its own distinctive sound. “When - Live at NPR’s Tiny Desk,” recorded for the online series in 2023, provides a matured perspective on the song.(23) The originally sparse accompaniment of one piano, cello, and violin has been replaced with a sweeping collection of strings, providing a more cinematic quality to the piece. In this version, although the vocals still retain the spoken quality of the original recording, they are performed more hastily, clipped, and unpitched. The melody of the verse appears almost secondary to the whispered diction of each consonant. Visually, dodie maintains a much smaller and more relaxed mouth posture, with less prominent gritted teeth, as seen in Example 12b. These qualities make an embodied analysis of the song more difficult, but demonstrate the reflective and mature tone of the 2023 version.

Video Example 4. Two versions of “when” by dodie, (2016 and 2023)

(click to watch video)

[4.9] The 2023 version has less distinction between the vocal quality of each verse and chorus than the 2016 version does, and there is almost no use of strong chest or standard mixed voice. While each verse is still performed in the chest voice range, the whispered diction creates a bridge between the lower-register verses and the bedroom pop mixed voice employed in the choruses, which centers around the breathy, soft timbre (e.g. 8:03, 9:12). These features give the piece an overall warmer and more mature sound. Video Example 4 begins shortly before and plays through the second chorus of the 2016 version, then proceeds to the 2023 version at the same point in the song form. Note the breathier style heard in the later version, which creates an aural paradox: although dodie’s voice inevitably has matured over seven years, her performance of the bedroom pop mixed voice in the 2023 Tiny Desk Concert keeps her voice sounding young through its short phrases and breathy tone, evocative of the narrative of “When.” The vocal performance in 2023 solidifies dodie’s choice to signal youthfulness; as researchers have documented, a breathy tone naturally occurs in the second phase of an estrogen-dominant adolescent voice when the focal folds do not fully close due to growth (Welch 2015, 452). While dodie got her start in her teens, she no longer fits in the young age range of modern bedroom pop performers. As if the idea of aging was not daunting enough, dodie is now threatened by aging out of the genre many credit her with originating. It is no surprise that a majority of her music directly addresses the passage of time, her age, and this continued fear of aging represented aurally and narratively.

[4.10] Singer-songwriter Lizzy McAlpine garnered fans beginning in 2020 at age 21 through her videos on Instagram and TikTok, which were recorded at home in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The song “reckless driving,” from her sophomore album five seconds flat (2022), provides rich opportunities to study her use of the bedroom pop mixed voice alongside vocal physiology, digital production techniques, and a male-coded voice.(24) In the studio version, instrumental and digital production techniques amplify the use of the bedroom pop mixed voice. The muted sound of the guitar in the verse is likely due to the use of a rubber bridge guitar, a popular choice for indie pop musicians in recent

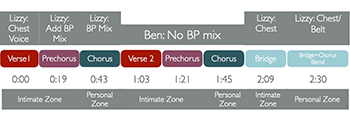

Example 13. Form diagram, “reckless driving”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4.11] In “reckless driving,” the specific use of the bedroom pop mixed voice throughout the chorus—but not in the verses or bridge—suggests that the choice to switch between modes of vocal physiology can be dependent on specific formal functions. Example 13 shows a form diagram of the song, with McAlpine’s specific vocal types highlighted over the formal units. Notably, her duet partner Ben Kessler does not use the bedroom pop mixed voice in the verse, prechorus, or chorus. McAlpine predominantly uses chest voice at the end of the song, reclaiming the chorus with the power of the chest voice as, narratively, she fears the worst for their relationship.

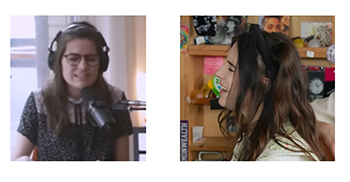

Video Example 5. Lizzy McAlpine, “reckless driving” on Instagram Live

(click to watch video)

[4.12] This formal delineation by vocal physiology is also reinforced with the consideration of Allan Moore’s proxemic zones, used to measure the perceived spatial distance between the listener and the recorded singing voice (2012, 187).(26) In the verse, McAlpine performs in the “intimate zone”—the closest possible position: her voice sounds within “touching distance,” the lyrics promote a sense of intimacy and physical contact, and the vocals are in the front of the mouth. In the chorus, she moves into the “personal zone”—still close, but a bit more separated—through the use of the bedroom pop mixed voice. The bedroom pop mixed voice’s breathiness creates less clarity in the vocal sounds, and the lyrics are less intimate, addressing slightly broader themes. The registral space between low instrumentals and high vocals in the chorus emphasize the open space within the personal proxemic zone. In the bridge, the lead vocal has moved into her chest voice and features a close mic position. At the same time, McAlpine has many layers of background vocals in the production mix, singing close-voiced chords using the bedroom pop mixed voice.(27) Combined with the dry digital production style, these additional vocal layers in the breathy, high style of the bedroom pop mixed voice imbue a sense of anxiety and vulnerability that builds to the end of the song. Video Example 5 shows Lizzie McAlpine performing an early version of “reckless driving” in her bedroom, accompanying herself on keyboard. Notice her use of external vibrato at 0:39 and 1:40, as well as the integration of the bedroom pop mixed voice in the prechorus and chorus of the song as she expands the upper vocal range of the melody (e.g. 1:43ff.). These external cues, alongside the sonic portrayal of the bedroom pop mixed voice, are ripe for mimetic engagement from other bedroom pop performers, like Kessler, as well as amateurs on social media.

[4.13] As noted, Ben Kessler does not use the bedroom pop mixed voice in his performance. For his verse and additions to the chorus, Kessler sings in the octave below McAlpine, predominantly using his chest voice. In his verse, Kessler alters the melody slightly, reaching an E4, which is the first instance of Kessler stretching beyond the chest into the standard mixed voice. Throughout his performance of the remainder of the verse and prechorus, Kessler frequently employs the standard mixed voice when performing above this note up to A4 and, occasionally, just below at D4. While he does not use the bedroom pop mixed voice, Kessler still attempts to match or complement the stylistic and timbral choices of McAlpine, most noticeably in his lower range during the verses. This comparison illustrates the gendered dynamic of the bedroom pop mixed voice—it is typically found in female-coded voices only, but both genders imitate and reflect the visual hallmarks of the style.

[4.14] In the verse, McAlpine focuses on the overproduction of words, highlighting at the ends of phrases the Americanized (or rhotic) “r” in words like “car” and “far” as well as in less-noticeable words like “you’re” in the line “you’re not convinced that I am real.” While McAlpine defines the words more sharply, Kessler uses a softer pronunciation like that of cursive singing. Like Halsey (as discussed above), Kessler pushes /s/ and /z/ sounds back in his mouth to create a /ʃ/ or “sh” sound in words like “exactly,” while pushing other sounds more forward, such as the /d/ sound in “don’t” to create a more dental quality, removing aspiration. Though these types of pronunciation changes can occur in bedroom pop to mimic the spoken or whispered quality, these specific changes appear to align more with the cursive singing style.

Video Example 6. Ben Kessler, “reckless driving” on TikTok

(click to watch video)

[4.15] Analyzing for cross-modal mimetic imagery becomes chiefly important in Kessler’s live reproduction of the song. While Kessler does not use the bedroom pop mixed voice, he replicates the associated facial expressions and mouth orientation throughout his performance, seen in Video Example 6. In this video, originally shared on TikTok, Kessler performs his verse accompanied by sparse guitar. He is singing in a range where mixed voice, chest voice, or head voice are accessible, and he demonstrates telltale physical indicators of the use of the bedroom pop mixed voice: external cues (lips, mouth shape, and cheekbones) and head shaking to induce vibrato. The grimace facial expression is noticeable primarily near the end of the video, when the vocal range is slightly higher, while the external vibrato can be seen throughout. His externalized vibrato represents intramodal MMI—he is not performing the sounds of the bedroom pop mixed voice but is, nevertheless, imitating the visual cues of the style.

[4.16] Kessler’s clearest use of the bedroom pop mixed voice mouth shapes occurs at the high notes of the final two lines of the verse, most noticeably at the words “exactly” at 0:17 and “lost” at 0:20. These are two of the only instances of Kessler using the standard mixed voice in this video, and they match up with his mix voice usage from the professional recording. Though he does not use his mixed voice throughout most of this performance, he continues to manipulate the creation of particular words, mimicking the bedroom pop mixed voice style. For example, at 0:14 of the video, on the word “tell,” Kessler’s mouth shape changes dramatically over the course of the word. Kessler sings this word twice in this cut of the song, each with significantly different mouth shape. The word “tell” can be formed using only interior mechanics and limited movement to create the sounds necessary to produce the word, and this is demonstrated in his first use of “tell” at 0:03. However, in his second iteration of the word at 0:13, Kessler performs the external cues associated with the use of the bedroom pop mixed voice, simultaneously moving his lips, eyebrows, and cheeks. Despite this movement, there is no noticeable timbral change from the rest of the vocal line, indicating no use of the bedroom pop mixed voice. Like McAlpine, Kessler implements breathiness and creakiness into his performance, creating the classic bedroom pop sound without using the associated bedroom pop mixed voice. These qualities are particularly noticeable in the earlier part of the verse, as in the second line “that I feel safe when you sit shotgun,” and can also be heard in the higher range in the fifth line “I know exactly where we’re going.” In the lower range, phrases like “that I feel” are almost completely obscured by vocal fry. This foray into cursive singing further bleeds into Kessler’s word pronunciation, giving his verse a hazier quality than McAlpine’s performance.

[4.17] The bedroom pop mixed voice contains several dominant traiths that are female-coded and that, together, provide an important counterpoint to the frequent criticisms that women and female-coded singers sometimes face. Other feminine-coded vocal techniques—vocal fry, up talk, lisp, and singing in cursive—are often treated as non-authoritative, infantilized, or amateurish.(28) Kessler does not perform using the bedroom pop mixed voice, despite visual and external cues that demonstrate his understanding of this vocal technique. Kessler may understand the use and purpose of the bedroom pop mixed voice, but seems to rarely produce the precise timbre (perhaps due to the thickness of his vocal folds(29)). Thus, the sound of the bedroom pop mixed voice is a particularly gendered technique.

5. Social Media, Mimetic Engagement, and Gender

[5.1] Media and digital culture have undeniably impacted the development and propagation of the bedroom pop mixed voice technique. The rise of Instagram and TikTok as primary modes of communication, especially for Gen-Z, has changed how music is distributed by artists and labels and consumed by audiences. The abundant covers, duets, and versions of songs made available on TikTok provide an example of how the vocal physiology of the bedroom pop mixed voice proliferates through online discourse and into the bedrooms of Gen-Z aspiring vocalists.

[5.2] In her study of vocal performance in cover songs, Malawey notes that “. . . live performance contexts provide additional attention to physical aspects of performance, which impact meanings listeners ascribe to the music and identities they attribute to performing artists” (2020, 9). Artists have direct access to fans through social media accounts, leading to increased communication, both of musical material and otherwise. YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok are rife with live versions (in whole or part) of songs and new material that artists easily and freely share with their followers, especially from artists still self-producing at home. Because the bedroom pop mixed voice is most readily identified with an aural and visual cue, the availability of live recordings (whether on apps like TikTok or in more produced settings via YouTube) is paramount to the identification and proliferation of this vocal style.

[5.3] The virality of bedroom pop songs on social media invites amateur participation in various forms. On a large scale, this sort of participation includes covers of an entire song by fans and other musicians. On smaller scales, apps like TikTok or Acapella invite participation through features that allow users to “duet” with original recordings, creating multi-track works that directly engage with prerecorded content. This sort of engagement creates a dialogue between users and artists that goes beyond mere repetition or replication: for example, performers also sometimes duet with amateurs on social media performing their own works, as seen in Video Example 1. These covers and versions of the song bring new meaning to the original songs by virtue of the new musical layer, allowing for new interpretations and analyses of voice, style, and (re)composition. On the subject of imitation, Nina Sun Eidsheim writes that “There is no essential or unified voice. Instead repeatable patterns where divergences are ignored create the sense of one. From a voice and sonority perspective, what is repeated in what may be perceived as vocal imitation is a degree of vocal pattern that is sufficient for recognition to take place. . . we create an image of a unified voice” (2019, 165). By imitating performers online, anyone can participate in and contribute to the “image of a unified voice”—in this instance, the specific aspect of the unified voice is the bedroom pop mixed voice. The bedroom pop mixed voice exists because of imitation taking place amongst artists and amateurs striving to “create the sense of one.”

Antiphonal Creation and Music Making

[5.4] When multiple musicians—professional, amateur, or otherwise—participate in the making and remaking of a work in a public sphere, the music essentially becomes antiphonal, as discussed by Braxton Shelley (2020). Shelley specifically focuses on meme culture, a uniquely digital and 21st-century phenomenon. He defines digital antiphony as the

. . . Emphatically intertextual and intermusical product and process of meme culture. Digital Antiphony is a rich, emergent conversation that simultaneously materializes and refigures social categories and concepts like race and gender, belief, and authorship. As antiphony’s animating form, the meme reveals a digital preoccupation with form. The meme, then, offers one sense of what it might mean to be musical in the 21st century” (8:42).

[5.5] Digital antiphony practice inherently requires participation and imitation at various scales and through different mediations online. TikTok users do not simply imitate works, they create new and emergent forms and propagate stylistic practices. Paula Harper (2020) discusses the concept of virality in social media, noting that

On TikTok, more so than on any preceding platform, music and sound function as fundamental components of contagion and spread. With music as an architectural platform feature designed to condense participation around sound files as hooks, performing along with a popular sound functions as a gateway to visibility, affording guaranteed inclusion in a potentially viral archive. Across videos, sound and music thus serve as sites for both sink and sync, ensnaring user attention and behavior as they construct digital communities of shared affect and practice.

[5.6] Videos on TikTok (and other platforms) create a form of community engagement and implicitly promote a mimetic and imitation-based vocal pedagogy that impacts physiology. As Harper shows, both the music and the sound are important; our intervention here is to show that the bedroom pop mixed voice, in addition to the songs themselves, creates a timbral thumbprint that is disseminated widely—antiphonally—through digital social platforms. Further, social media use blurs the distinctions between artist and amateur by inviting any user into the music and encouraging participation through features like duet (performing alongside original media) and stitch (adding video content following an existing TikTok). TikTok, in fact, relies on the idea that participants of all backgrounds should upload, share, and refashion content—this relates to Turino’s concept of participatory performance (2008, 29).(30) For many, social media engagement in this participatory and antiphonal way becomes the fabric and sound of social life (Turino 2008, 37).

Video Example 7. Olivia Rodrigo and @kaylagracemusic perform versions of “deja vu”

(click to watch video)

[5.7] Olivia Rodrigo, like other recent superstars such as Billie Eilish, was a teen star, and her music career grew rapidly in 2021 as she wrote music at home and posted excerpts on TikTok. While she quickly outgrew her bedroom walls with the immense success of “drivers license” (January 2021), she retains a keen ability to switch between vocal styles and recapture the timbre and vocal physiology of bedroom pop mixed voice on particular songs (see also “Lacy” from her 2023 sophomore album GUTS). Video Example 7 shows a brief clip of Rodrigo in a live performance of her 2021 song “deja vu.” Note the prominent use of the breathy bedroom pop mixed voice on each repetition of

[5.8] Immediately following Rodrigo’s chorus in Video Example 7 is a cover from an aspiring musician, @kaylagracemusic, also posted to TikTok. This cover imitates the use of the bedroom pop mixed voice on

[5.9] Watching the video reveals that, while the bedroom pop mixed voice is not consistently used in @kaylagracemusic’s performance, the physical markers are. Through analyzing amateur videos, it becomes clear that the facial traces of the bedroom pop mixed voice become the primary cues of the genre on social media. Returning to Cox’s mimetic hypothesis, it is unsurprising that purely visual intra-modal MMI would happen naturally over TikTok, as the app’s origins began as a platform for lip-syncing (known as Musical.ly, before its merger with TikTok in 2018). Intra-modal (direct visual imitation) MMI is commonly seen in bedroom pop covers and originals performed by male-coded voices, as they tend to perform without the aural cues of breathiness in the upper registers. Amateurs may even be conscious of the phenomenon, as seen in Video Example 8, where user @shots_by_sophia lip syncs to Olivia Rodrigos’ “Strange,” an unreleased song that leaked and circulated throughout TikTok in 2022. The user notes that “my mouth moves like Olivia Rodrigo’s,” bringing the user’s awareness of intra-modal MMI to the fore (an overt and intentional use of MMI) and imitating the physical movements but not the analogous sound-producing actions. In Video Example 9, singer @nate_poshkus performs all the visual cues of the bedroom pop mixed voice, but he does not have the breathiness and quietness found in the aural characteristics of the style. The sound-producing actions, thus, do not conform to the bedroom pop mixed voice timbre, even if the visual cues are the same. Both videos show the users moving their lips, baring their teeth, raising their eyebrows, and chewing the text in the upper register. User @nate_poshkus predominantly uses chest voice (the lower register in the verse) and a belt (the upper register in the chorus), lacking the breathy timbre heard in the bedroom pop mixed voice. In both examples, intra-modal MMI is still present due to the visual actions present, despite a lack of aural cues.

Video Example 8. @shots_by_sophia lip sync with Olivia Rodrigos’ “Strange” (click to watch video) | Video Example 9. @nate_poshkus on TikTok showing intra-modal MMI (click to watch video) |

Bedroom pop mixed voice and the performance of gender

[5.10] As we have previously addressed through the analysis of the bedroom pop mixed voice, gender and identity play significant roles in the style. Gender dynamics are also strongly tied to the reception and creation of the music and often act as a democratizing force for women and female-coded, or marginalized voices. For example, Paula Wolfe describes how the bedroom-as-studio has opened the door for more women in digital production roles and has contributed to an increase in women’s creative activity due to ease of access (2012, 2–3). Emília Barna describes how the proliferation of bedroom pop in a home studio alleviates issues of gendered labor in domestic spaces (2022, 197). The accessibility of digital platforms as a means to connect artists (again articulating Turino’s participatory performance) combined with the intimacy of the bedroom space has allowed women and people of marginalized identities to more fully participate in and gain traction in the musical community. The artist mxmtoon notes in an interview, “‘As a woman of color and someone who has a lot of different intersections in a lot of marginalized identities, I have a whole lot that I could say all the time

[5.11] L. J. Müller defines their idea of the “real voice,” wherein “realness is constructed through this intersection of aesthetic belie[fs] and singing techniques which in the end construct a particular relation between outer and inner self, body and subject” (2022, 95). The idea that outer pressures contribute to the sense of “real voice” is most frequently correlated with privilege and the white, cisgender, male voice. The opposite of the “real” voice is to be othered: the artist and/or the listener can be othered. To eschew the ideal “real voice” and its external forces is to reject the norms and embrace otherness. The examples of female-coded voices shown by Müller demonstrate that “musically, the listening subject is separated from the singing subject and placed in the center of the song” (2022, 174). We argue that the musical examples and artists presented in this article, and the use and propagation of the bedroom pop mixed voice broadly speaking, is a result of female-coded voices reclaiming their “real” voice. This reclamation is a two-part process: first, artists center their “real” voice by creating and producing the music themselves, exerting control over the process from start to finish. This process opens a direct line of communication to the listening subject, creating “congruence” (2022, 173) between the artist and the audience. Second, listening subjects can then become participants in the music and develop their own real voice. Female-coded voices in particular have the ability to create the bedroom pop mixed voice in their own performance, adding another line of congruence between musical voices.

[5.12] Returning to Eidsheim’s ideas on imitation, the lack of an essentialized voice fits perfectly within the bedroom pop genre. Vocal performances in the genre resist homogenization because of the importance of artist control and identity in the creation of the music. Yet imitation can still be recognized; according to Eidsheim, there is “1. Knowledge of the original voice, 2. A memory of the original voice, 3. The ability to hear the imitator’s original voice, and 4. Recognition of the imitation voice as superimposed on the imitators [sic] original voice” (2019, 166). Thanks to social media, the first three conditions are typically met, and the fourth is implied in the case of cover songs.

Conclusion

[6.1] At its most basic level, the bedroom pop mixed voice is one example of a musical gesture or a timbral artifact that carries meaning in its usage and transmission, like the Nokia ringtone, Apple’s marimba tone, or a Hammond Organ.(31) Utilizing the bedroom pop mixed voice in a song marks sonic intimacy and vulnerability, and transports the listener to the soundworld of the artist’s bedroom. During times of quarantine and isolation, listeners and artists craving community and collaboration foster connection by sharing their most intimate spaces. The transmission of the bedroom pop mixed voice (and arguably, most new musical content in pop, broadly speaking) relies on social media. If and when platforms evolve (due to the introduction of new technology or government intervention against platforms like TikTok), the industry will adapt, and the aesthetic will inevitably change.

[6.2] As time moves farther away from the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, the intimacy of bedroom pop may no longer be as desirable, and artists who started in the bedroom have found and will find commercial success. A paradox arises: if an essential part of bedroom pop’s creation and consumption involves a strong sense of intimacy and youth, then the forward march of time may render bedroom pop dormant in a few short years. We suspect, however, that musicians’ and listeners’ hunger for connection, vulnerability, and engagement will always be present.

Alyssa Barna

University of Minnesota

Ferguson Hall

2106 S 4th St.

Minneapolis, MN 55454

barna@umn.edu

Caroline McLaughlin

Minneapolis, MN

caroline.et.mclaughlin@gmail.com

Works Cited

Akinfenwa, Jumi. 2020. “A Brief History of ‘Cursive Singing,’ From Amy Winehouse to TikTok.” Vice, July 21, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en/article/pkyqkv/cursive-singing-tiktok-trend-explained.

Baker, Sarah Louise. 2004. “Pop in(to) the Bedroom: Popular Music in Pre-Teen Girls’ Bedroom Culture.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 7 (1): 75–93.

Barna, Alyssa. 2018. “No, iPhone Ringtones Aren’t Bad. They’re Musically Sophisticated.” The Washington Post, June 7, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/no-iphone-ringtones-arent-bad-theyre-musically-sophisticated/2018/06/07/e0c5d75a-69a1-11e8-bea7-c8eb28bc52b1_story.html.

Barna, Emília. 2022. “Bedroom Production.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music, Space and Place, ed. Geoff Stahl and J. Mark Percival, 191–204. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501336317.ch-015.

Burgos, Karen. 2021. “Dialect Dissection: Indie Voice/Cursive Singing - The Definitive Post.” Ace Linguist (blog), May 3, 2021. https://www.acelinguist.com/2021/05/dialect-dissection-indie-voicecursive.html.

Burt, Stephanie. 2020. “Precarity, or, Halsey: How Manic Comes Apart Like a Millennial.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 32 (3): 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1525/jpms.2020.32.3.3.

Castellengo, Michèle, Bertrand Chuberre, and Nathalie Heinrich. 2004. “Is Voix Mixte the Vocal Technique Used to Smoothe the Transition across the two Main Laryngeal Mechanisms an Independent Mechanism?” Proceedings of the International Symposium on Musical Acoustics (ISMA2004), Nara, Japan.

Chandler, Kim. 2014. “Teaching Popular Music Styles.” In Teaching Singing in the 21st Century, ed. Scott D. Harrison and Jessica O’Bryan, 35–51. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8851-9_4.

Chao, Monika, and Julia R. S. Bursten. 2021. “Girl Talk: Understanding Negative Reactions to Female Vocal Fry.” Hypatia 36 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/hyp.2020.55.

Chappell, Whitney, John Nix, and Mackenzie Parrott. 2020. “Social and Stylistic Correlates of Vocal Fry in a cappella Performances.” Journal of Voice 34 (1): 156.e5–156.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.06.004.

Cox, Arnie. 2011. “Embodying Music: Principles of the Mimetic Hypothesis.” Music Theory Online 17 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.17.2.1.

—————. 2016. Music and Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking. Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt200610s.

Davies, Helen. 2013. “Never Mind the Generation Gap? Music Listening in the Everyday Lives of Young Teenage Girls and Their Parents.” Volume! 10 (1): 229–47.

Eidsheim, Nina Sun. 2019. The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478090359.

Everett, Walter. 1999. The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. Oxford University Press.

Gopinath, Sumanth. 2013. The Ringtone Dialectic: Economy and Cultural Form. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262019156.001.0001.

Hall, Edward T. 1969. The Hidden Dimension. Anchor/Doubleday.

Harper, Paula. 2020. “Music as Sync and Hook in the TikTok Bedroom.” Paper presented at the American Musicological Society 86th Annual Meeting, virtual.

Harrison, Nicola, and Alan Watson. 2020. A Singer’s Guide to the Larynx. Compton Publishing.

Heidemann, Kate. 2016. “A System for Describing Vocal Timbre in Popular Song.” Music Theory Online 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.22.1.2.

Herbst, Christian T. 2021. “Registers—The Snake Pit of Voice Pedagogy, Part 2: Mixed Voice, Vocal Tract Influences, Individual Teaching Systems.” Journal of Singing 77 (3): 345–58.

Holmes, Jessica A. 2019. “The ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl of the Synth-Pop World’ and Her ‘Baby Doll Lisp’: Grimes and the Disabling Logics of the Feminization and Infantilization of Lisping.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 31 (1): 131–56. https://doi.org/10.1525/jpms.2019.311011.

—————. 2023. “Billie Eilish and the Feminist Aesthetics of Depression: White Femininity, Generation Z, and Whisper Singing.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 76 (3): 785–829. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2023.76.3.785.

Hunter, Eric, Marshall E. Smith, and Kristine Tanner. 2011. “Gender Differences Affecting Vocal Health of Women in Vocally Demanding Careers.” Logopedics, Phoniatrics, Vocology 36 (3): 128–36. https://doi.org/10.3109/14015439.2011.587447.

Jones, Colin, Murray Schellenberg, and Bryan Gick. 2017. “Indie-Pop Voice: How a Pharyngeal/Retracted Articulatory Setting May Be Driving a New Singing Style.” Canadian Acoustics 45 (3): 180–81.

Kennedy, John. “Lizzy McAlpine Breaks Down ‘Reckless Driving’ Acapella.” Tape Notes (podcast), December 14, 2022. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11ckNwSwk6M.

Kochis-Jennings, Karen Ann, Eileen M. Finnegan, Henry T. Hoffman, and Sanyukta Jaiswal. 2012. “Laryngeal Muscle Activity and Vocal Fold Adduction During Chest, Chestmix, Headmix, and Head Registers in Females.” Journal of Voice 26 (2): 182–93.

Lions Voice Clinic. n.d. “Your Voice & How it Works—Anatomy.” University of Minnesota, Department of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://med.umn.edu/ent/patient-care/lions-voice-clinic/about-the-voice/how-it-works/anatomy.

Malawey, Victoria. 2020. A Blaze of Light in Every Word: Analyzing the Popular Singing Voice. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190052201.001.0001.

Malde, Melissa, MaryJean Allen, and Kurt-Alexander Zeller. 2020. What Every Singer Needs to Know About the Body. Plural Publishing.

Marchand Knight, J., and Crystal Marchand. 2020. “Them and the Timbre of Gender.” In Public: The Gender-Diverse Lens 62, ed. Wayne Baerwaldt, 41–59. https://publicjournal.ca/product/62-the-gender-diverse-lens/.

Miller, Donald G., and Harm K. Schutte. 2005. “‘Mixing’ the Registers: Glottal Source or Vocal Tract?” Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica 57: 278–91. https://doi.org/10.1159/000087081.

Moore, Allan. 2012. Song Means: Analyzing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Ashgate.

Müller, LJ. 2022. Hearing Sexism: Gender in the Sound of Popular Music. A Feminist Approach. Translated and revised with Manu Reyes. transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839458518.

Newton, Elizabeth. 2020. Audio Quality as Content: Everyday Criticism of the Lo-Fi Format. PhD diss., The Graduate Center, CUNY.

Pennington, Stephan. 2022. “Transgender Passing Guides and the Vocal Performance of Gender and Sexuality.” In The Oxford Handbook of Music and Queerness, ed. Fred Everett Maus and Sheila Whiteley, 238–75. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793525.013.65.

Roos, Olivia. 2020. “What’s Bedroom Pop? How an Online DIY Movement Created a Musical Genre.” NBC News, February 6, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/music/what-s-bedroom-pop-how-online-diy-movement-created-musical-n1131926.