A Survey of the Impact of COVID-19 on Music Theorists

Janet Bourne, Rachel Lumsden, and Inessa Bazayev

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, work/life balance, academic life, Society for Music Theory, qualitative analysis, Braun and Clarke

ABSTRACT: We administered an online survey to study the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the productivity and work/life balance of people who teach music theory and/or aural skills in higher education. The survey included quantitative and qualitative questions about research, 2020–2021 teaching, 2021–2022 teaching, service, and the relationship between work and personal life. According to the survey data, music theorists felt that their ability to work on research, the time they spent teaching, and satisfaction with work/life balance were, indeed, impacted by the pandemic. However, how people were disrupted by the pandemic varied from person to person, especially as demonstrated by the qualitative data. We conclude with several takeaways: (1) we should acknowledge the challenges we experienced living through a global pandemic; (2) we should recognize the pressure of time and overwork within our discipline; and (3) we could improve our disciplinary community through empathy and care.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.5

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[0.1] In November 2022, the Society for Music Theory (SMT) held its first in-person annual meeting since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.(1) At this conference, the SMT Work and Family Interest Group (WorkFam) met to discuss the results of a short pilot survey on the experience of music theorists during this difficult time.(2) The aim of the initial pilot survey was modest: the goal was simply to get a general sense of the challenges that people had experienced during this period.

[0.2] We were not prepared for the quantity and content of the responses that we received to this survey. Many respondents shared harrowing accounts that were often difficult to read. People described their experiences not just with overwork, exhaustion, and lack of motivation, but also with illness, disability, family care challenges, unemployment, depression, suicidal ideation, and death of friends and family. There was a clear feeling of overwhelm in the pilot survey responses.

[0.3] At the conclusion of the WorkFam meeting, attendees expressed relief at the personal, honest tone of the conversation, and contrasted it with the rest of the conference unfolding outside of that room, which, in general, did not address the collective experience since the last in-person meeting. One person poignantly noted that once our meeting ended, we would return to the conference and would have to keep pretending that nothing had happened over the past two years. They viewed the conference as a kind of performance. It was acceptable to discuss our challenges in the safe space of that particular room, but these conversations could not occur in the larger, more public space of the conference outside, where many attendees projected an upbeat, unflappable guise of constant productivity and professional achievement.

[0.4] This project arose from that conversation, and our desire to make space, publicly, for the experiences of music theorists during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic. This essay discusses how COVID-19 has affected the research, teaching, service, and work/life balance of music theorists. Our study has two primary aims. First, we share results from a second survey (which was substantially longer and more detailed than the pilot survey) that we designed and administered to music theorists about their experiences during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (defined here as 2020–2022).(3) These data provide a concrete record of the varied ways that the COVID-19 pandemic affected—and for some, continues to affect—the careers and personal lives of music theorists. Many of these responses also illustrate the larger, systemic problems in academia as a whole, in relation to taking care of physical and mental health, beyond the acute phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, we hope that the anonymous responses shared here will prompt both individual and collective reflection. We hope the comments included in this essay will inspire us to treat one another with more empathy, and to use this experience to work together to create a more supportive, equitable, and understanding discipline.

[0.5] Following this introduction, the essay is organized into five parts: 1. Methods and Data Collection; 2. Discussion of Quantitative Results; 3. Method for Analyzing Qualitative Data; 4. Discussion of Qualitative Results; and 5. Conclusion.

1. Methods and Data Collection

Design, Materials, and Procedure

[1.1] We administered an online survey through Qualtrics between April 10 and May 15, 2023. The purpose of this survey was to study the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the research, teaching, service, and work/life balance of faculty members who teach music theory and/or aural skills in higher education. The survey was a mixed design, with both quantitative and qualitative questions (see Appendix I for survey questions). It was organized into the following sections, where questions addressed: research; teaching during the 2020–2021 academic year; teaching during the 2021–2022 academic year; service; and work/life balance. The survey then ended with questions about respondent demographics. The survey contained a total of 32 questions. To analyze the quantitative data, we used standard statistical tests (see Appendix II for statistical results). We used Thematic Analysis to analyze the qualitative data, as practiced and described by Braun and Clarke (2006, 2019, 2021), a method that has previously been used with qualitative survey data (see Braun et al. 2021 ). We recruited participants by advertising the survey on the

Participant Demographics

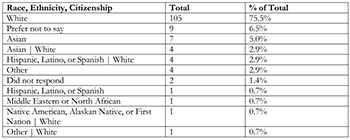

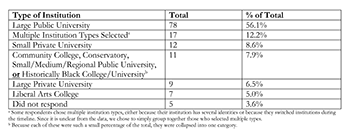

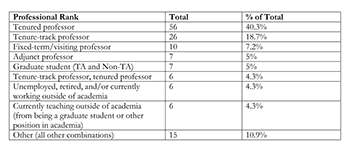

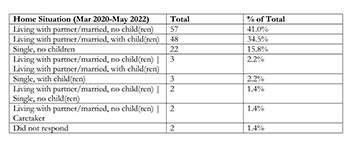

[1.2] 139 anonymous participants completed the survey. Of these respondents, 54% self-identified as Male, 38.8% self-identified as Female, 2.9% represented as Non-Binary/3rd Gender and 4.3% did not respond or preferred not to say.(4) When asked if they identified as a member of the LGBTQIA+ community, 70.5% of respondents chose no, 20.1% responded yes, 5.8% preferred not to say, with 1.4% choosing other. As can be seen in Example 1,(5) most respondents (75.5%) identified as White/Caucasian.(6) Similarly, a majority of people reported being at a large public university (56.1%) (Example 2). Example 3 reports the professional ranks of respondents from March 2020 to May 2022. Respondents were encouraged to select all that applied during this timeframe (e.g., if they changed jobs, were promoted, had multiple positions, etc.). Finally, we asked respondents to report their home situation from March 2020 to May 2022, checking all that applied to them (Example 4).

Example 1. Respondents’ self-identified race, ethnicity, and/or citizenship (click to enlarge) | Example 2. Type of Institution (click to enlarge) |

Example 3. Professional rank from March 2020 to May 2022 (respondents selected all that applied during this timeframe; all other combinations that represented less than a total of 4% collapsed into “Other”) (click to enlarge) | Example 4. Home Situation from March 2020 to May 2022 (respondents could check all that applied during that timeframe) (click to enlarge) |

2. Discussion of Quantitative Results(7)

Impact on Research

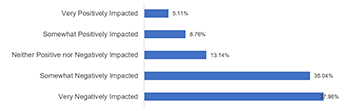

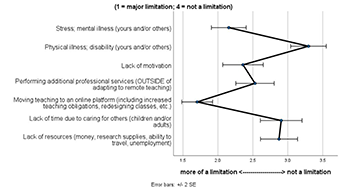

[2.1] Many music theorists felt that their ability to work on research and research productivity was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. When asked about the time frame between March 2020 and May 2022, 37.96% of all respondents indicated that their research and research productivity was “very negatively impacted” while 35.04% responded “somewhat negatively impacted” (Example 5). While the majority indicated that they were negatively impacted, a small percentage of respondents indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic positively impacted their research productivity in some way (8.76% were “somewhat positively impacted” and only 5.11% were “very positively impacted”). Of course, these are self-reported findings; a majority people indicated feeling as if their research and research productivity was impacted, no matter their situation. When asked what limited their engagement in research activities (between March 2020 and May 2022), people most frequently reported that moving their teaching to an online platform most significantly limited their ability to engage in research, with stress and mental health the second most-cited limitation (Example 6).

Example 5. How impacted their ability to work on research and their research productivity was, on average, between March 2020 and May 2022 (click to enlarge) | Example 6. How strongly each of the following limited their engagement in research activities between March 2020 and May 2022 (click to enlarge) |

Impact on Teaching

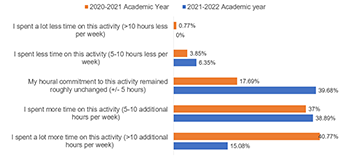

Example 7. Comparing how time spent on teaching changed in an average work week during the 2020–2021 and the 2021–2022 academic year compared to an average work week before the COVID-19 pandemic

(click to enlarge)

[2.2] Many music theorists reported that the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted the time they spent teaching. We asked how time spent on teaching changed for both the 2020–2021 academic year as well as the 2021–2022 academic year (Example 7). When we inquired about how teaching time changed during 2020–2021, 40.77% and 37% overall indicated that they spent a lot more time (>10 additional hours) or more time (5–10 additional hours), respectively, on this activity. For the 2021–2022 academic year, more people indicated that their hourly commitment remained roughly unchanged (39.68%). However, many theorists still reported spending 5–10 more hours on this activity (38.89%) and even >10 hours per week (15.08%). Respondents’ gender impacted the amount of time spent on teaching for both academic years: women reported spending significantly more time on teaching compared to men. When asked how time on various activities changed during the 2020–2021 academic year compared to an average work week before the COVID-19 pandemic, respondents across all genders indicated that emotional support for students in particular took significantly more time.

Impact on Work/Life Balance

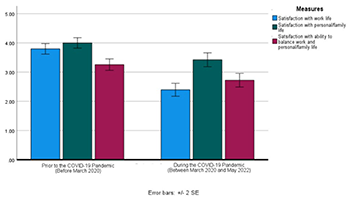

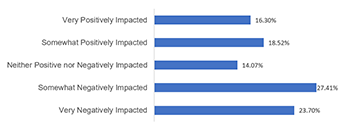

[2.3] Across the board, respondents unsurprisingly indicated that satisfaction with their work life, with their personal/family life, and with their ability to balance the two dropped significantly during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020–May 2022) compared to before the pandemic (Example 8). When asked about working from home and its impact on their work/life balance, respondents had mixed reactions: a quarter of respondents (23.70%) felt that it impacted them very negatively, while about a sixth (16.30%) felt that it impacted them very positively (Example 9). Depending on their situation, some people really enjoyed and thrived in a work-from-home environment while others were eager to return to campus (more on this in the qualitative results).

Example 8. Level of satisfaction for various measures prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and during the height of the pandemic (click to enlarge) | Example 9. How working from home at any point during 2020-2022 impacted their work/life balance (click to enlarge) |

3. Method for Analyzing Qualitative Data: Thematic Analysis

[3.1] To analyze the qualitative data, we used Braun and Clarke’s (2006, 2013, 2021) approach to thematic analysis, a “method for developing, analyzing and interpreting patterns across a qualitative dataset, which involves systematic processes of data coding to develop themes” (2021, 4). Our approach to the dataset was primarily inductive, in that we used the “dataset as a starting point for engaging with meaning” (rather than driven by existing theories) (2021, 56). In our survey, seven questions involved open-ended or freely formed responses, and we analyzed each question separately, generating codes and themes for the datasets generated by each question.(8) All three authors analyzed the data. As described by Braun and Clarke (2021, 35–36), thematic analysis has six phases:(9)

Phase 1: Familiarizing yourself with the dataset. Here, researchers immerse themselves in the dataset via reading and re-reading the data, making notes about analytic insights or ideas. In our analysis, all three authors read and re-read the data separately, making notes and discussing potential codes for the following phase in collaborative Zoom meetings.(10)

Phase 2: Coding. Researchers systematically work through the dataset to identify “segments of data” that seem meaningful or relevant, applying “analytically meaningful” descriptions via code labels where the code labels capture one facet, meaning and/or concept (Braun and Clark 2021, 35). In our analysis, we considered both semantic (explicitly-expressed meaning) and latent (conceptual or implicit meaning) features when coding the data. For this project, all authors coded all the data independently and then we had several meetings in which we discussed our codes in order to better understand and interpret the data. Therefore, we engaged in “collaborative coding” (Braun and Clarke 2021, 285), where we “work[ed] together to code data and develop codes through discussing and reflecting” on our “ideas and assumptions” (285).(11)

Phase 3: Generating initial themes. Here, researchers “start identifying shared patterned meaning across the dataset,” where they “compile clusters of codes that seem to share a core idea or concept” (35, italics in original). Initial theme development for the dataset of each question was performed separately (where Bourne developed initial themes for three questions, Bazayev for two questions, and Lumsden for two questions).

Phase 4: Developing and reviewing themes. In this phase, researchers “assess the initial fit of your provisional candidate themes to the data, and the viability of your overall analysis, by going back to the full dataset” (35). In thematic analysis, a theme “is a pattern of shared meaning organized around a central concept” (Braun and Clarke 2021, 77). As part of this process, researchers check that the themes “make sense in relation to both the coded extracts” as well as the “full dataset” (35). In this project, each author separately generated themes for their questions’ datasets, reviewing those initial themes by checking back to coded data extracts as well as the original datasets. We viewed developing themes as a flexible process that develops organically (Braun and Clarke 2019). Then, all authors met to review the initial themes.

Phase 5: Refining, defining and naming themes. At this point, each theme is “demarcated” and “built around a strong core concept or essence” (35). Here, all three authors collaboratively generated the final themes for each question’s dataset, agreeing on the themes that best “fit” the data. All authors finalized the theme names and wrote synopses. We collaboratively ensured that each theme had a well-defined central organizing concept.

Phrase 6: Writing up your analysis. All authors were involved in writing the paper.

4. Discussion of Qualitative Results

4.1 Research

[4.1.1] Question: “What were some of your biggest challenge(s) related to research or your ability to engage in research between March 2020 and May 2022?”

[4.1.2] We received an overwhelming number of responses to this question, even though it was optional. Some commenters provided intensely personal reflections on their experience with research during the pandemic, which were often difficult to read.

We identified three primary themes in the responses:

| Time went to other things | Lack of sufficient time for research due to increased teaching responsibilities, caring for family members, and/or increased administrative work |

| External barriers | Difficulties completing research because of lack of funding, problems with accessing materials, travel restrictions, unemployment, and/or restrictions on in-person interaction |

| Emotional and motivational challenges | Loneliness and isolation; lack of support; lack of motivation; mental health struggles (stress, anxiety, burnout, depression) |

Time went to other things

[4.1.3] Many music theorists struggled to complete their research during 2020–2022 because they did not have the same amount of time to devote to research as they did before the pandemic. Available time for music theory research was reduced due to significant increases in time spent on teaching, taking care of family members, and administrative work.

[4.1.4] Teaching experiences during the pandemic will be addressed in more detail below, but many respondents noted that their research productivity was negatively impacted because the majority of their available time was spent on teaching, due to having to shift their courses to online or hybrid formats (often on short notice, and often for the first time). One commenter succinctly explained how their “workload doubled due to online teaching needs” (P14).(12) Some commenters began new positions during the pandemic, which required them to design entirely new courses for online delivery at a new institution. Some tenure-track instructors had to design and redesign courses for various modes of delivery (online, hybrid, in-person) during the first years of their position. Two representative responses summarize the impact that online teaching had on research:

“Almost completely unable to find time to conduct research without cutting deeply into personal time because of the transition to online teaching, which multiplied my responsibilities and gave students a platform to demand constant engagement.” (P4)

“Converting all of my teaching to an online format was extremely time consuming and required more contact hours with students than I might normally need in a face-to-face setting for them to feel successful.” (P63)

[4.1.5] Other respondents were not able to complete their research because of family responsibilities, such as caring for children, or caring for ill, elderly, or disabled family members. One respondent described their experience with their hospitalized child and shared that “there were many months of my life in which I was caring for a child and not producing much work” (P20). Since many public schools and daycare centers were closed during acute phases of the pandemic, respondents with children had to juggle childcare and (for those with children in school) their children’s online schooling/homeschooling responsibilities, in addition to the increased time spent on their own music theory teaching. As one respondent explained, “Any time that was not needed for the immediacy of teaching—of being responsible for a group of people in the moment—was spent with my young children, focused on them and their health and safety in a way that I had not previously experienced. Any time that I dedicated to work with no immediate result caused incredible guilt over not being with my children” (P85). For many respondents, time spent on family care, especially when combined with new challenges from teaching, made research almost impossible.

[4.1.6] Finally, respondents working in administrative roles noted that their workloads increased because of time spent dealing with pandemic-related issues (which many respondents had to manage in addition to their teaching responsibilities). One commenter explained that they lacked research time because “It came down to capacity: teaching, chairing a department, supporting colleagues and students simply took up every bit of time and energy that I had” (P100).

External barriers

[4.1.7] Music theorists also faced material and financial barriers to completing their research. Many respondents were not able to access books or scores because their libraries were closed and were not able to receive materials on Interlibrary Loan in a timely fashion (or at all). Others could not use their offices because of university closures, such as the participant who remembered consulting online resources such as Hathitrust, but “there were still many resources that I could not access, and at one point I was calling friends for references in books in my own office that I could not access” (P93). Several respondents had no library access at all during this time (either in-person or online) because they were independent scholars or unemployed and lost their library privileges since they were no longer affiliated with a university. Some participants described losing their travel or research funding because of budget cuts or travel restrictions. Finally, respondents in some subfields of music theory simply could not work on their research at all, either because it required human participation or collaboration (experimental research, performance-based research) or travel (archival work, ethnographic work).(13)

Emotional and motivational challenges

[4.1.8] For many participants, their music theory research was negatively impacted by challenges with their emotional well-being and/or mental health. Respondents in all stages of their professional careers found it difficult to complete their research amidst the turmoil of the pandemic, and described experiencing loneliness, stress, anxiety, worries about getting sick, worries about the future, lack of motivation, lack of support, and depression.

[4.1.9] Isolation and loneliness due to social distancing and online interactions negatively affected some respondent’s research productivity. One participant described how shifting to online conferences “did not stimulate thinking regarding my research. It felt like I lost my community” (P88). Another commenter felt that their “executive function suffered terribly in lockdown as did my motivation. Being cut off from socializing had a huge effect on my desire and motivation to do research” (P134).

[4.1.10] Other participants began to question the relevance of their research or the relevance of music theory more generally, either because of the pandemic, sociopolitical conflicts, or even disciplinary shifts within music theory. Several respondents directly cited the 2019 SMT plenary (featuring Philip Ewell, Yayoi Uno Everett, Joseph Straus, and Ellie M. Hisama) and fallout from the publication of the 2020 volume of the Journal of Schenkerian Studies as impacting their research productivity.(14) As one commenter explained, “given the recent social and political upheavals of the last few years, I’m not sure how much my research matters” (P16). Another described how during the pandemic, in combination with the events following the 2019 SMT plenary, “I felt completely lost and did not have a strong sense of who I wanted to be as a music theorist” (P61).

[4.1.11] Many commenters at a variety of career stages struggled with stress and mental health issues; several specifically listed “depression” as significantly impacting their research during this time. Graduate students and recent PhD graduates seemed particularly vulnerable. One PhD student shared how they experienced “a lot of mental health

[4.1.12] Although most respondents to this question reported significant struggles with their research, a few respondents were able to continue their research without difficulty and listed “no challenges” when answering this question. Since our survey was anonymous, we do not know exactly how or why this small number of respondents were able to continue their research without major problems. (Our guess is that some combination of natural optimism, ability to compartmentalize, stable faculty position, access to resources, stable living/family situation, and their particular subfield of research allowed these individuals to continue researching and writing as before.) One respondent noted that their research was not impacted during this time because “I was single and bored and had lots of writing time” (P50). Another explained that “since I conduct research remotely anyway, there weren’t many challenges” (P66).

[4.1.13] For most commenters, a combination of various aspects of all three themes affected research productivity—most individuals did not face one single challenge, but many different (and often competing) demands. One final quote encapsulates the experience of not being able to complete one’s research because of being pulled in so many different directions simultaneously:

“No time and no mental bandwidth—all devoted to keeping my classes going, my graduate student teachers supervised and supported, and things going on at the university I am responsible for, PLUS two middle-schoolers at home taking classes online while I am teaching online” (P107)

[4.1.14] It is difficult to predict the long-term impact of these years on music theory research. Will there be fewer submissions to music theory journals and conferences for a few years, as we recover from the acute phase of the pandemic? Or will submissions increase the further music theorists get into post-pandemic lives? These questions are beyond the scope of this project, which is a general overview of the field as a whole from 2020–2022. We hope other scholars will use the information in this essay to pursue these questions of long-term research impact in future studies.

4.2 Teaching (2020–2021)

[4.2.1] Question: “What were some of your biggest challenge(s) related to teaching or your ability to engage in teaching during the 2020–2021 academic year?”

We identified four primary themes in the responses:

| Feelings of disconnection | Lack of human connection in online teaching; discouragement from lack of student engagement in online classes |

| Unrealistic expectations | Expectations that are ultimately unsustainable; faculty expected to do their job (or even additional labor) without support; increased workload |

| Teaching “starting from scratch” | Faculty feeling like they have to relearn how to teach; having to learn new technology to teach online; re-designing and making new materials for online teaching; frustration with not being able to re-use materials |

| What was easy before isn’t now | Challenges with teaching classes that were once easy to teach, but are not easy to teach online (e.g., aural skills) |

Feelings of Disconnection

[4.2.2] Numerous respondents shared that their teaching changed during the 2020–2021 academic year. Many universities shifted their classes to online or hybrid formats, and teachers noted strong feelings of disconnection or disengagement with these modalities. Instructors found it difficult to connect with their students in online classes. Many participants described a frustratingly lonely teaching experience where students often turned their Zoom cameras off, didn’t participate in class discussion, and overall were disengaged with the course and its content. In turn, this had a similarly negative impact on instructors, who felt as if they were teaching into a virtual abyss, facing rows of small black screens with white student names. Three representative comments summarize these challenges: “(l)ack of personal connection with students” (P55); “engagement was the largest issue, especially in large classes where it was black screens with names” (P89), and “the vast majority of my students kept their cameras off, and the university strongly discouraged us from requiring them to turn their cameras on! It was such a lonely, frustrating experience” (P113).

Unrealistic Expectations

[4.2.3] Many universities decided to shift classes to online or hybrid formats to try to keep students and faculty safe during the first year of the pandemic. However, respondents expressed frustration with increased workloads, including expectations by their university administration to teach online without adequate support or resources. In a general sense, this theme intersects with responses to other survey questions discussed throughout this section: people expressed difficulties with having to keep going no matter what, and without sufficient institutional support. Specific challenges described by respondents included increased workload, lack of appropriate technology provided to faculty and students, close to no training in using new technology, and expectations to accommodate students while there was no real support for faculty, who were struggling themselves. Four illustrative comments summarize these themes:

“Teaching loads were increased to an unsustainable degree.” (P132)

“University balanced budget by asking us to take on additional teaching (one extra course).” (P69)

“We received very little support in transitioning to online courses early on, so there were always A/V issues during synchronous classes.” (P122)

“I had to design an asynchronous course with little support or guidance. That was an enormous effort, and it felt like a risk not knowing whether it would “work” (whether students would embrace it, whether they would learn, whether they would be well enough to participate, etc.). It was a huge effort to plan, but a limited effort once the course was underway.” (P31)

Teaching “Starting from Scratch”

[4.2.4] Many participants described difficulties with designing online and hybrid courses. Some instructors began teaching for the first time during this year but felt unprepared since they had never been in any kind of classroom before (in-person or virtual). As one respondent explained, “I began teaching (virtually) in Fall 2020. I had no in-person teaching experience beforehand. Learning to teach via zoom without ever having been taught via zoom was challenging” (P97). Other instructors with previous teaching experience recounted feeling as if they had just begun to teach for the first time and had to reinvent the wheel, such as the instructor who expressed frustration with “the time-consuming need to redesign my materials and pedagogical approach for various online learning modalities” (P57). For many respondents, a big part of the challenge was learning to use new technology (often quickly, and without sufficient training), such as the instructor who emphasized their struggles with “learning new technology to create teaching videos, new online exercises” (P71).

[4.2.5] Instructors working in hybrid settings also faced additional challenges, as two illustrative comments demonstrate:

“Hybrid teaching was so much work and required so much extra prep.” (P17)

“Preparing and designing my typical classroom for hybrid learning—setting up multiple cameras and high fidelity microphones in the classroom, setting up a wireless microphone for myself to wear, configuring software to allow for streaming of all of this audio and video through zoom for remote students, and recording (and managing) all of the sessions for students to access asynchronously (if they were sick, for example).” (P8)

What was easy before isn’t now

[4.2.6] For many respondents, teaching took more time this year than it had previously: many class-related tasks became notably more time-consuming. As previously discussed, increased time spent on teaching negatively impacted the research productivity of many people. Three comments summarize some of the ways that time spent on teaching increased for participants:

“Small tasks that take hours to complete in technology, like moving a paper test to online format.” (P82)

“Preparing the materials in our LMS [Learning Management System](15) took a huge amount of time; I had used it minimally prior to COVID, as the LMS was not necessary when we met in person.” (P107)

“All the extra work needed to ‘thrive’ in an online space. Needing to make online content available, making videos for asynchronous sessions, finding new ways to teach concepts online that would otherwise only work in person.” (P25)

[4.2.7] Finally, many respondents noted specific difficulties with teaching music theory and aural skills online. Aural skills classes were consistently cited as particularly problematic:

“[M]y standard teaching techniques like singing in unison did not work over Zoom.” (P123)

“Teaching a large aural skills class online was very difficult to improve students’ sight singing. Students could not sing in person, and online meetings were at 9AM when they did not feel comfortable singing in their dorm rooms.” (P6)

“Teaching Aural Skills synchronously over Zoom was a NIGHTMARE—just very challenging with audio issues, playback, trying to teach polyrhythms when you can’t hear the students, etc. Theory was a bit easier of a transition but building the video lectures for asynchronous days was time consuming.” (P77)

[4.2.8] In short, teaching in 2020–21 posed many pedagogical and technological challenges. Often, instructors were left to figure things out for themselves, and to try to make the best of a grim situation on their own. The themes above reveal how teaching during the first year of the pandemic was a frustrating, isolating, and exhausting experience for many music theorists.

4.3 Teaching (2021–2022)

[4.3.1] Question: “What were some of your biggest challenge(s) related to teaching or your ability to engage in teaching during the 2021–2022 academic year?”

We identified five primary themes in the responses:

| Pressure to be in person | Faculty and students felt unsafe and/or uncomfortable about in-person classes, but university policies/administrators required a return to in-person or hybrid instruction |

| New challenges with teaching | Teaching in person came with extra safety precautions (masks, social distancing) that were challenging to navigate in music theory and aural skills courses; university policies for instruction changed frequently (and often without sufficient notice); delivering courses in hybrid format (with synchronous and asynchronous components); dealing with student absences |

| Re-designing courses again | Changing courses back to in-person modality after being online; frustration from spending so much time on course design; frustration from creating materials/lesson plans for online or hybrid classes that would not be used again |

| Re-adjusting to being in person | Exhaustion, burnout (instructors and students); students were not as prepared because of challenges during the 2020–2021 academic year; many students struggled with mental health issues; challenges navigating social dynamics after a year of isolation/social distancing |

| Pleased with trajectory | Less severe challenges than previous year; glad to be back in-person |

Pressure to be in person

[4.3.2] Many universities returned to in-person instruction in Fall 2021, after COVID-19 vaccines became widely available. However, because of the political polarization surrounding vaccines and COVID-19, university policies for instruction varied, and often seemed to hinge on the broader political climate in which an institution was located. For example, we each experienced different situations at our respective institutions, even though they are all large state universities with “R1” status (doctoral university—very high research activity).(16)

[4.3.3] Worries about illness permeated many classrooms and created feelings of anxiety for instructors and students. One respondent described being pregnant during the 2021–2022 academic year while being required to teach in person; their main concern was trying to not get sick. Other respondents had received vaccines themselves, but feared being in classrooms with others who were unmasked and unvaccinated. Three representative responses capture the heightened anxiety that many respondents experienced when returning to in-person classroom instruction.

“I also had to deal with increased mental health issues among the students and their fear of being in-person (and my

own). . . My students and I sometimes felt unsafe in the classroom.” (P25)“I felt very unsafe teaching here, which impacted my ability to interact with my students and my embodiment in a classroom

setting. . . For example, I had to acclimate myself to being in a roomful of students unmasked and singing in aural skills. This has certainly impacted my relationship to my employer and to academia in a negative manner—it’s as if my own health and well-being (as well as that of students) did not matter.” (P104)“I had a panic attack when I returned to the classroom after eighteen months. I was required to be in classrooms and my office with antivaxxers.” (P119)

New challenges with teaching

[4.3.4] In Fall 2021, those who returned to in-person teaching (or hybrid teaching, with a partial in-person component) faced new obstacles in their theory and aural skills classrooms. Teaching in masks created difficulties in learning, communicating, and student participation. Respondents emphasized how challenging it was to teach and learn while masked, especially in aural skills classes. One commenter shared that they seriously injured their vocal cords while teaching in a mask, since they had to speak more loudly than usual in order to be heard (P15).

[4.3.5] Instructors also struggled to manage student absences. Many commenters characterized this academic year as having a feeling of uncertainty in the classroom, due to the occurrence (and unpredictable timing) of large numbers of student absences during surges of new variants of COVID-19. Instructors spent additional time creating and grading make-up assignments, shifting course materials to an asynchronous format, or having extra office hours. One instructor characterized their experience during 2021–2022 as “lots of office hour meetings to re-teach material for students who missed class, especially during the Omicron wave” (P28).

[4.3.6] Some instructors taught hybrid courses during 2021–2022, either by choice or because of university requirements. Commenters with this experience noted how time consuming it was to teach in person while also designing an asynchronous option for students who might need to miss class due to illness; their workloads essentially doubled. As one respondent noted, hybrid classrooms “preserved many of the challenges of online teaching while compounding them with in-person responsibilities” (P4).

Re-designing again

[4.3.7] As discussed in the previous section, many instructors experienced frustration in 2020–2021 when initially shifting their classes to an online format. For some respondents, frustration returned in 2021–2022 when universities required hybrid formats or asynchronous options, which resulted in yet another year spent redesigning courses. Some new instructors (whose first year of teaching occurred online in 2020–2021) had to redesign their online courses for in-person or hybrid format.

[4.3.8] Instructors also struggled as university policies fluctuated. Policy changes often required instructors to make significant adjustments to their courses in a short amount of time, and without help or guidance. One instructor explained how they redesigned their online 2020–2021 courses for in-person delivery in Fall 2021, but in Spring 2022 their university suddenly pivoted back to online courses. They characterized their teaching experience as being “jerked back and forth between various forms of teaching, each requiring course redesign” (P69).

Re-adjusting to being in-person

[4.3.9] Returning to in-person (or partially in-person) instruction in 2021–2022 impacted students and instructors intellectually, mentally, and emotionally. Many respondents noted that the energy in their classrooms felt low, as students and instructors seemed tired and lacked motivation. Others emphasized how social dynamics felt awkward when returning to in-person instruction after being online. Many instructors felt their students were unprepared because of spending the previous academic year in online courses, both in terms of learning loss and lack of sufficient study skills. As one respondent explained,

“The students were exhausted and so was I. It seemed that we all struggled to resume in-person activities, and all found it overstimulating and draining. Things that I used to think were easy pre-pandemic, were/are noticeably much more taxing for students. They were all used to being on Zoom and muted; getting them to sing and actively participate (rather than watch me like I was a TV show) was a big struggle at all levels.” (P61)

Pleased with trajectory

[4.3.10] While many instructors continued to struggle during 2021–2022, some felt their experience was significantly more positive than the previous year. One respondent who continued teaching online in 2021–2022 explained that “it was actually better in 2021–2022 since by that time I was comfortable with Zoom and had no new teaching preps” (P53).

[4.3.11] Other instructors expressed relief about returning to in-person teaching. Two respondents summed up their experience with a noticeable sense of optimism:

“I loved being back in person, and my child was at this point in Montessori school. It was great.” (P20)

“I was really happy to be back in person, and while I was still spending a fair amount of time on teaching prep, I could see a future (the next year) in which I wouldn’t spend all my time on it anymore, so that was encouraging.” (P33)

[4.3.12] As we can see from these responses, the overall level of anxiety regarding the spread and contraction of COVID-19 remained high during the 2021–2022 academic year, even as vaccines became available and instructors and students returned to in-person instruction. Many people feared becoming ill or infecting family members; these worries were particularly acute for those who have immunocompromised family members or are immunocompromised themselves. Unpredictable and ever-changing university policies and modes of instructional delivery—which were different across the country, and largely dependent on local politics and regulations—also created frustration for instructors. Although a handful of respondents noted that their teaching situation improved during the 2021–2022 academic year, 92% of respondents explained that they (and their students) continued to feel exhausted, isolated, and unsupported by their universities.

4.4 Service

[4.4.1] Question: “What were some of your biggest challenge(s) related to service during 2020–2022?”

We identified four primary themes in the responses:

| Challenges of meeting online | Difficulties with communicating with colleagues, students, and administrators online; difficulties navigating social dynamics online; missing in-person interactions |

| Extra emotional burdens | Service work had additional emotional challenges due to feelings of burnout, exhaustion, responsibility for others, and frustration with lack of guidance |

| Always having to do more | Service workloads increased, along with demands for working outside “normal” hours |

| Adapting to new procedures | Learning new technology; learning new procedures for completing service tasks; colleagues working in administrative roles had to develop and implement new policies and protocols related to the pandemic (often without guidance) |

Challenges of meeting online

[4.4.2] During the pandemic, service meetings and student advising sessions shifted to an online format at many universities. Participants noted that such online interactions created difficulties with communicating effectively and problems with engagement. These issues arose in both faculty and student meetings.

[4.4.3] Online meetings exacerbated problematic social dynamics between faculty. As one respondent explained, “Meeting remotely negatively affected ability to communicate with colleagues and decreased civility of interactions among faculty” (130). Other respondents described how online meetings were frequently dominated by loquacious colleagues, such as a respondent who noted that Zoom meetings “seemed to exaggerate the divide between those who talk a lot and those who are more quiet” (P131).

[4.4.4] Participants also expressed difficulties with advising students online, noting that online meetings with students seemed “less effective” (P10) than meeting in person. (Faculty also encountered additional emotional challenges with advising students online, which will be discussed in more detail below.)

[4.4.5] In all, participants expressed ambivalent (and somewhat contradictory) reactions to online meetings. Although online meetings have obvious advantages (convenience, not having to travel), for some respondents these benefits did not outweigh the difficulties created by engaging with one another virtually rather than in-person. As one respondent pithily summarized, “The service work all got done, but the crucial community piece was missing” (P16).

Extra emotional burdens

[4.4.6] As with teaching, service work during the pandemic created additional emotional challenges. Faculty experienced feelings of stress, exhaustion, burnout, and frustration. One participant explained how they felt “underappreciated and undervalued” because their university offered no additional support for faculty mental health during this time (P13).

[4.4.7] This emotional strain often increased because of feelings of responsibility for others. Many commenters explained that they felt a strong urge to complete their service tasks effectively, and to help others who were struggling, but did not receive sufficient guidance about how to accomplish these things. Participants frequently described feeling unsure about how to meet the needs of others. These sentiments seemed especially acute for those working in administrative roles, and those who were advising students. One commenter described how their work as department chair resulted in “feeling responsible for the health and safety of all music students, staff, and faculty” (P100). Another respondent explained, “Students were

Always having to do more

[4.4.8] As with teaching, respondents experienced an upsurge in service work during the pandemic. Service work grew because of pandemic-related challenges, and respondents frequently noted that there “were many more online meetings to attend” (P15). Commenters also explained how shifting meetings online also meant that they were frequently expected to work outside of normal working hours (meetings occurred in the evenings, or on weekends). Workloads intensified for faculty working in administrative roles, such as the respondent who noted that “we had a lot more meetings, more documents/policies to review, and we had to respond to a lot more faculty concerns” (P123). Some faculty had more regional and national service work because they had to organize online conferences.

[4.4.9] Respondents also experienced frustration with their service work because they were expected to work harder and longer without receiving additional compensation or recognition. One commenter explained how in their role as conference organizer, they “essentially had to organize the conference twice, once in-person and once online due to changing pandemic needs. None of this does anything on my CV or promotion schedule but it took a lot of time and effort” (P25).

Adapting to new procedures

[4.4.10] Although completing service work online created difficulties with regards to social interactions, many respondents acknowledged that online formats were much more efficient for some service tasks, such as completing paperwork. However, other faculty expressed frustration with shifting some service tasks online because it ended up being more time-consuming, such as the respondent who noted that moving theory placement tests online “makes a ton more work” (P44).

[4.4.11] Similarly to experiences with teaching, some respondents struggled with learning new formats and procedures, or found it difficult to complete service work with colleagues who had varying levels of technological expertise. One commenter noted that they have “above average computer skills,” but explained that “engaging with colleagues on service issues with a variety of skill levels was challenging” (P117).

[4.4.12] Music theorists who also work in administrative roles faced new challenges, particularly since they often had to create new policies and procedures quickly, and frequently without clear guidance. This administrative work was wide-ranging and went well beyond serving music theory students and music theory faculty: respondents discussed having to devise solutions to a host of different issues related to the pandemic, such as policies for lessons, classrooms, practice rooms, rehearsals, and concerts; managing classroom technology and live streaming sessions for concerts; preparing for NASM (National Association of Schools of Music) evaluations; and even acquiring PPE (Personal Protective Equipment, such as masks) for students and faculty. One commenter characterized the experience as “endlessly developing new protocols” (P100); another explained that they needed to create safe policies “with essentially no useful guidance” (P76).

[4.4.13] Service-related work did not seem to negatively impact respondents as intensely as teaching and research during the pandemic. (Indeed, we received significantly fewer responses in the survey for this question than we did for the questions for teaching and research.) However, we also note some significant intersections with service, teaching, and research. Respondents acknowledged that online interactions felt different, and frequently were not as impactful as communicating in person. Workloads increased, along with expectations for working outside normal working hours. For many respondents, this created feelings of stress, burnout, and/or frustration.

4.5 Working from Home

[4.5.1] Question: “If you worked from home at any point, what were some of your biggest challenge(s) and/or more positive aspect(s) of working from home during 2020–2022?”

We identified four primary themes in the responses:

| Blurred boundaries | Lack of clear separation between work and personal/family time; lack of demarcation between work and personal/family spaces at home; inadequate work space; challenges of working while also caring for children/family at home |

| Stressed and exhausted | Fatigue; expectations to work longer hours; mental health challenges; physical health challenges; lack of motivation; decreased productivity |

| Isolated | Loneliness; lack of connection with friends, students, and colleagues; missed being in person |

| Appreciation for time at home | More personal/family time; saving time and money by not commuting; increased productivity |

Blurred Boundaries

[4.5.2] Working from home in 2020–2022 posed a major challenge. In addition to working longer hours, participants struggled to maintain clear divisions between work and home spaces, as well as work and personal/family time. As one participant summarized, “I never really had a break from work” (P4).

[4.5.3] There was a general sense of people physically being in each other’s way while they attempted to work from home, whether because of living in a small space with roommates, moving back home with one’s parents, spouses/partners both trying to work from home, or trying to work from home while also caring for family members. Many respondents lacked resources to do their jobs easily and effectively, such as a home office, piano, or technological equipment, but were expected to do their jobs anyway. Five representative comments capture some of these challenges:

“No clear divide between work and home spaces.” (P2)

“Sharing space with my partner, who also needed to work from home. Living life entirely in two rooms.” (P28)

“I do not have a suitable workspace at home and strongly prefer to work at my school office. I was physically crammed into a small corner of a guest bedroom for an entire year. Even worse, were the constant interruptions while working from home.” (P61)

“Kids everywhere!

. . . trying to oversee their useless online learning while I did my useless online teaching was awful.” (P19)“The biggest challenge was to find space in the house for two parents and two teenagers to do separate zoom classes/meetings. For my classes I had to use an unheated attic for my Zoom classes.” (P49)

Stressed and Exhausted

[4.5.4] Working from home created stress and exhaustion: in addition to frustrations related to sharing space, shifts to online platforms led to increased expectations for constant availability. Respondents described feeling like they were always on the job because of virtual classes and meetings. The expectation for prompt email replies at all times of the day became part of the norm. Three participants summed up the experience:

“Though it was perhaps convenient to be in my home more during Spring of 2020, I wouldn’t call it a positive aspect, as we were together a lot and in one another’s way, sharing limited internet resources, and all feeling the stress of the uncertainty of the moment.” (P8)

“Competing needs/demands in the same space, leading to noise and short tempers that reduce ability to focus.” (P82)

“I found myself working far more and being far more accessible to students/colleagues than was really wise.” (P25)

“There [wa]s no mental space for deep thinking or deep work.” (P44)

Isolation

[4.5.5] Beyond stress and exhaustion, isolation played a significant role in participants’ lives. This included feelings of lost community (both with colleagues at one’s university and the broader music theory community), lack of opportunities for socializing, and disconnection with students on Zoom.

“Lacking the social engagement and enthusiasm from my colleagues and students, I really struggled to keep a positive attitude and sustain energy.” (P41)

“Having no choice but to work from home for months, the isolation was the biggest challenge.” (P54)

Appreciation for Time at Home

[4.5.6] However, not all experiences were entirely negative. Many participants described some positive aspects of working from home, such as saving time and money on commuting, or wearing comfortable clothes. A few noted that working at home provided much-needed relief from a toxic work environment. Some participants cherished the opportunity to spend more time with family. Others expressed how being at home provided more time for research.

“Prior to the pandemic, my job required me to be geographically separated from my husband and family. When we went online I was able to move back home and we could be together again, so I was very grateful for that.” (P53)

“My spouse and I could more easily be in touch with each other if needed throughout the day and evening.” (P71)

“I saved about 10 hours a week by not having to go anywhere or teach in person. I think my dissertation would’ve taken longer without the pandemic.” (P43)

“I used the time normally spent commuting to accomplish more research than ever before. It greatly increased my productivity.” (P79)

[4.5.7] Working from home provides some obvious benefits, but for at least some respondents these benefits did not outweigh the challenges. Exhaustion and stress increased as boundaries between work and personal life became less distinct. Although some participants acknowledged the benefits of spending more time at home with family members, some also felt isolated from their larger community of friends and professional colleagues. As one commenter succinctly noted, “Having some time at home is always great to get work done and save time on commuting. But I find working remote full-time very isolating and depressing” (P33).

4.6 Institutional Changes Related to Work/Life Balance

[4.6.1] Question: “After your experiences in 2020–2022, what institutional changes would you like to see at your own university to assist faculty with issues of work/life balance?”

We identified four primary themes in the responses:

| Realistic workloads | Desire for realistic and sustainable workloads; fewer demands for outside of working hours; equity in workload distribution |

| Flexibility and understanding | Desire for flexibility in their work and being understood for that desire |

| More institutional support | Feeling unsupported by their institution; lack of sufficient resources; lack of support for students; wanting more transparency and guidance |

| Feeling valued | Wanting to feel valued by their institution as an individual and a person, but also wanting the work they’re doing as part of their institution to be valued |

Realistic Workloads

[4.6.2] Participants strongly desired realistic or sustainable workloads. People frequently described feeling like they were being asked to work an unsustainable number of hours, including outside of “normal” work hours and on weekends. For example, one participant wrote:

“Almost everyone I know works at least part of all seven days in the week. A stronger emphasis on the weekend as a pause.” (P5)

People also shared their feelings related to sustainability and their workloads. Consider the following response:

“I think clarifying tenure and promotion requirements would go a long ways [sic] to giving people permission to sometimes ‘turn off’ from work mode.” (P29)

[4.6.3] The evoking of “permission” in this response indicates that some people worry that unless they are constantly working—or in “work mode”—then they are going to fall short of their tenure case requirements or abilities to excel at their job. This expectation that they needed to be constantly working exhausted people. There were also feelings of frustration with constantly being asked to do just a “little bit more,” even if they already felt like they worked long hours. The pandemic exacerbated already-existing issues of work/life balance for music theorists.

Flexibility and Understanding

[4.6.4] Participants also expressed the desire for flexibility in their work, especially in the modality of their work (whether online or in-person). Technology was evoked as providing an opportunity for this kind of flexibility; many respondents expressed a desire for keeping some events online, such as committee and department meetings. Several respondents were glad that some meetings were still held via Zoom, even as the acute phase of the pandemic waned, and that some administrative tasks had shifted to an electronic format. Similarly, some people suggested having more freedom in the modality of their teaching:

“Allow us to implement lessons from online teaching by letting us choose when and how to teach online or in person.” (P25)

[4.6.5] Participants also noted that they wished their colleagues, departments, and administrators would understand why they wanted that flexibility. It was not just that they wanted various options; they also did not want to feel penalized or judged negatively for wanting flexible class format options. It may seem like a discrepancy that respondents were asking to potentially teach or meet online while also displaying frustration and lack of engagement with online modalities. However, we believe that these reactions reflect different considerations. A desire to retain some flexibility via electronic formats seems natural now that online platforms have become commonplace. In contrast, the sudden shift to online formats at the start of the pandemic was far more drastic and disruptive, as it occurred with little or no preparation. These respondents wanted accommodations and understanding from their colleagues and institutions, and the option to continue using online platforms when needed, especially regarding personal/family situations and preferences for certain types of work. As one respondent explained, “I would hope my institution (and we as a field) can continue extending the same degree of understanding and flexibility that was at least espoused during the pandemic (if not universally implemented) and can accommodate individual faculty members in individual ways so as to make room for personal/family needs, preferred working hours, preferred responsibilities, etc.” (P106)

More Institutional Support

[4.6.6] Along related lines was a desire for tangible support from their institution, either through increased staff, mental and physical health services, technological assistance, support for students, leaves/reduced teaching loads, and just more resources overall. For example, one respondent listed several ways their institution could support both them and their students:

“Support student mental health outside the classroom, and provide instructors with support when these issues impact the regular work of the semester.” (P25)

[4.6.7] People mentioned that they were expected—or wanted—to “keep going” and complete certain parts of their jobs but could not do this as effectively because there was not adequate institutional support. They felt frustrated by feeling they were held to expectations without adequate support to meet those expectations.

Feeling valued

[4.6.8] Similarly, people expressed strong feelings of wanting to be valued by their institution, both as a person—not just another “body”—but also for the work that they do. People worked hard and did good work but they felt like that work was not recognized, which created additional feelings of frustration or hopelessness. For example, consider the following responses:

“They could treat us as if our skills were valued.” (P13)

“I guess I’d love to see the amount of care and thought I put into designing inclusive, relevant, and accessible classes recognized more than it is.” (P33)

“Stop hiring so ma[n]y goddamn administrators and actually treat faculty like experts rather than bodies that are expendable.” (P87)

[4.6.9] In these quotes, people exhibit a level of self-awareness about their own skills and work (that their skills are to be “valued,” that they are “experts”) as well as that the work they do takes a lot of thought. There is a suggested dichotomy of “recognized” vs. “expendable,” where people feel as if their institution treats them as expendable—as just a rotation of bodies which could easily be replaced—instead of being valued as individuals and as human beings. Respondents suggest desiring a certain level of respect, rather than as someone from whom their institution can continuously ask for more.

4.7 Institutional Changes for Work/Life Balance within the SMT

[4.7.1] Question: “What disciplinary and/or institutional changes would you like to see within the field of music theory and the Society for Music Theory with regards to work/life balance?”

We identified four primary themes in the responses:

| Multiple ways to participate | More opportunity to participate remotely (especially in conferences); broadening online participation to include all members of the Society |

| Equity, diversity, and support for marginalized communities | More equity for junior, teaching (including adjunct and non-tenure track), and marginalized faculty; support for faculty working in different kinds of university settings |

| Reducing pressure to be productive | Don’t romanticize workaholic tendencies; more realistic approach to expectations for promotion and tenure |

| Fostering community (theory community and the community outside of theory) | More collaboration between people inside and outside of the Society for Music Theory |

Multiple ways to participate

[4.7.2] An overwhelming number of respondents recommended that conferences should include multiple ways for attendees to participate, both in-person and virtually, and noted that hybrid options are more inclusive of people with family care responsibilities and people with disabilities. Some of the comments included:

“I guess the main thing is continuing to make conferences accessible to everyone via Zoom so that no one’s excluded because they have family to care for at home or a

disability. . . I look forward to going to SMT in person this year, but I hope we can build on the accessibility lessons learned.” (P53)“Allowing presenters to present remotely at conferences. Some families, such as mine, have one spouse that works away from home much of the time, thus barring me from attending conferences in person (i.e., I need to take care of my kids).” (P15)

“I’d like to see more of an acceptance of online teaching and online conferences. Moreover, I think it’s important for SMT to consider moving to an online conference every 3 or 4 years, matching AMS.” (P44)

Equity, diversity, and support for marginalized communities

[4.7.3] Many respondents wanted more support from the SMT for members who work outside of R1 universities. Participants also discussed how SMT might consider reforming their peer-review processes to be more collaborative. The following three quotes encapsulate:

“More support and advocacy for those SMT members teaching at institutions with higher teaching loads and less support (financial and otherwise) for research and professional activities.” (P49)

“A wholesale reassessment of the peer review process. I find it exhausting to think of all the work I have to do just to get an article in, but then to have it rejected or asked for revise and resubmit with millions of comments that incur tons more work is just not tenable for me with my heavy teaching load and parenthood. I think it would be much better to pitch an idea to a journal then work collaboratively with reviewers to bring the project to fruition.” (P134)

“The SMT should actively solicit committee service from unemployed theorists (such as myself) who might have more time for such duties. Currently, we’re often overlooked for such invitations because we’re not ‘prestigious.’” (P64)

Reducing pressure to be productive

[4.7.4] People also discussed how they are affected by romanticized, unrealistic expectations of constant productivity. Many participants described feeling increased pressure to publish in order to earn tenure or promotion, and frustration that they are expected to always be doing more, even if their senior colleagues had seemingly earned tenure and promotion with much smaller achievements. Others expressed frustration that their tenure cases would be viewed negatively by external reviewers if they had tenure-clock extensions because of the pandemic or other major life events (such as illness or parenthood). Such comments included the following:

“Reduction in the ‘arms race’ for publications and productivity. The expectations just keep going up—just because an Ivy League university requires two books for tenure doesn’t mean that every institution should. The pressure to ‘always be productive’ means that junior faculty adopt very unhealthy work/life balances.” (P47)

“I’m sure this is true for every field, but I feel like the bar for achieving tenure and promotion just keeps getting higher. I would love for the senior colleagues in our field to be kinder to their junior colleagues, both in their mentorship and as outside reviewers. If I compare what my senior colleagues had accomplished at the time they earned tenure, to what I am expected to do now, I should (by their measure) be a full professor by now.” (P61)

“Tenure clock extensions often negatively impact the faculty member, particularly when it comes to external reviewers’ expectations. I think that SMT could help to combat this through acknowledgment generally and education of those likely to serve as external peer reviewers specifically.” (P85)

Fostering community (theory community and the community outside of theory)

[4.7.5] Finally, respondents felt that SMT could work harder to build community both within and outside music theory. Participants discussed how SMT could engage in more community building for its members, as well as outreach initiatives:

“Greater connectivity with members, easier access to peer networks and working groups, more regular meetups (online, in-person) with peer networks.” (P110)

“More outreach to primary and secondary school faculty, who after all send us our students.” (P120)

[4.7.6] Based on these responses, it is clear that participants felt that the SMT can work harder to be more inclusive, play a larger role in reassessing the peer-review process, and foster community within and outside the Society.

Conclusion

[5.1] It is no surprise our survey results indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted life for music theorists regarding their research, teaching, service, and work/life balance. One aim of this essay is to provide specific documentation of the ways that the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic directly affected music theorists and their work. We feel it is vitally important to have some kind of historical record available, to mark what happened during these difficult years.

[5.2] A second takeaway from this project is that music theorists were affected by the pandemic in different ways. There is no uniform pandemic experience. Everyone faced challenges, but precisely how people’s lives were altered, and why they struggled varied—sometimes drastically!—from person to person. For example, some people found it difficult to work at home because they lacked space and were surrounded by other people, while others felt that difficulty because they were extremely lonely and isolated at home. Some were eager to get back to campus, others were anxious at that idea. Many members of our community experienced (and continue to experience) disability and other health-related problems, including mental health difficulties and depression. Some respondents who self-identified as disabled noted that COVID-19 did not substantively change their day-to-day experience, such as the commenter who explained that “the pandemic didn’t really pose any new challenges” since they already had been dealing with unemployment and isolation (P64). If there is a lesson to be learned from the pandemic, it could be to recognize that we all face different challenges, and that our disciplinary community would improve if we extended more empathy and care to one another. This resonates with recent work such as Cheng (2016, 2020), Hisama (2021), and Lett (2023).

[5.3] Third, the concepts of “time” and “overwork” hummed below the surface of our data. Most respondents to our survey described working harder, longer, and outside normal working hours. The expectation to “keep going” no matter what, and often without sufficient support from one’s university, brings to mind Sumanth Gopinath’s research on neoliberalism, Marxism, and the academy (2009, 2023), in particular his recent call for us to push back against “the academy’s cheapening of labor costs at the expense of the livelihoods and wellbeing of music theorists” (2023, 129). In our opinion, the acute phase of the pandemic and its associated pressures on music theorists was not an anomaly—rather, it is illustrative of the larger, systemic problems of work/life balance in academia. The academy continues to demand more of all of us, and it is imperative that we examine the cost.

Example 10. This is What Happens When Both Our Parents Teach on Zoom. Mixed media installation (tempera paint, bottles, paint trays, chair, and other found objects). Thea López-Lumsden and Elliott López-Lumsden, 2021

(click to enlarge)

[5.4] Finally, we believe that the COVID-19 pandemic, like many life experiences, cannot and should not be reduced to a simple “good” vs. “bad” binary. Many respondents noted that they also experienced a newfound appreciation for what really mattered in their lives, such as one commenter who described “greater time spent appreciating and fostering interpersonal relationships when they did happen in person” (P88). We experienced these flashes of joy and comic relief amidst dark times, too—such as the impromptu “mixed media artwork” (read: giant mess of paint all over the floor) created by Lumsden’s two toddlers in April 2021, while she and her partner both were trying to teach their Zoom classes at the same time (Example 10).

[5.5] The COVID-19 pandemic was (and perhaps still is) a collective trauma. We don’t want to erase it, to simply go “back to normal” and forget it happened. We want to address it, to process it, to acknowledge it as members of a community. Writing this essay was one way we could shed light on this upheaval and give voice to those impacted by it. Moving forward, we hope to use what we learned from this collective experience to create positive changes in our music theory society, and our music communities as a whole.

Appendices

Appendix I: Survey Questions

Click this link to see a document with the whole survey. Some questions drawn or adapted from a similar survey for ecology and evolutionary biology faculty as reported in Aubry et al. (2021).

Appendix II: Statistical Analyses and Results

Impact on Research

Multiple Kruskal-Wallis H tests were run to determine if there was an impact of gender, race, caretaker status, or type of institution on respondents’ reported ability to work on research or research productivity. Median scores were not statistically significant different between groups for any of these variables (p > .05).

We asked how strongly each of the following conditions limited respondents’ engagement in research activities between March 2020 and May 2022: lack of resources (money, research supplies, ability to travel, unemployment); lack of time due to caring for others (children and/or adults); moving teaching to an online platform; performing additional professional services; lack of motivation; physical illness and/or disability (yours and/or others’); and stress and/or mental illness (yours and/or others’). Respondents rated each activity on a Likert scale from 1 to 4 (where 1 indicated a major limitation and 4 indicated a not a limitation). A Friedman test was used to see if some conditions were more of a limitation to respondents’ ability to engage in research than others. Pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used. Different conditions significantly impacted respondents’ research engagement, χ2(6) = 96.99, p < .001. In the post hoc analysis, it was revealed that respondents thought that moving teaching to an online platform impacted their research (Mdn = 2) statistically significantly more compared to other conditions. Similarly, stress and mental health also statistically significantly impacted their research (Mdn = 2) more so than other conditions (except for motivation).

Impact on Teaching

Respondents were asked how their time spent on teaching changed in an average work week during the 2020–2021 academic year as well as the 2021–2022 academic year compared to an average work week before the COVID-19 pandemic. People could choose whether they spent a lot more time on this activity (>10 additional hours per week), more time on this activity (5–10 additional hours per week), their hourly commitment remained roughly unchanged (+/- 5 hours), spent less time on this activity (5–10 hours less per week), spent a lot less time on this activity (>10 hours less per week). For the data related to the 2020–2021 academic year, multiple Kruskal-Wallis H tests were run to determine if there were differences in the amount of time changed for teaching between participants based on gender, race, caretaker status, course load and type of institution. There were only significant differences in teaching time based on gender: female (N = 49), male (N = 73), and non-binary/3rd gender (N = 4). As visually assessed by inspecting a boxplot, distributions of changes in teaching time were similar for all groups. Median changes were significantly different between groups, χ2(2) = 9.73, p < .05. To follow up, pairwise comparisons (with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons) were performed (with adjusted p-values). According to this post hoc analysis, there were statistically significant differences in median scores between men (M = 2.04, Mdn = 2) and women (M = 1.59, Mdn = 1) (p < .05), but not between men and non-binary/3rd gender (M = 2, Mdn = 2) and not between women and non-binary/3rd gender. While everyone spent more time on teaching overall, it seems that women in particular spent significantly more time compared to men. For the data related to the 2021–2022 academic year, we see a similar pattern. Again, multiple Krusal-Wallis H tests were run to see if there were differences between participants based on gender, race, caretaker status, courseload and type of institution. Again, only gender—female (N = 47), male (N = 73), and non-binary/3rd gender (N = 3)—was statistically significant, χ2(2) = 20.20, p < .001. The post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in median scores between men (M = 2.64, Mdn = 3) and women (M = 1.96, Mdn = 2). There were no significant differences between men and non-binary/3rd gender (M =2.33, Mdn = 2) or between women and non-binary/3rd gender. This result indicates that, once again, women reported spending more time on teaching than men.

A Friedman test was run to see if respondents’ time on various university, teaching, and service activities changed in an average work week during the 2020–2021 academic year compared to an average work week before the pandemic. These activities included: administration, service to the university, service to the department, professional mentoring and/or advising, and emotional support for students. Respondents could choose multiple options between having spent more time to having spent less time. Pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons indicate that respondents spent significantly different amounts of time on these activities, χ2(4) = 30.87, p <.001. Specifically, post hoc analysis indicated that respondents spent significantly more time on emotional support for students (Mdn = 2) compared to administration (Mdn = 3), service to the university (Mdn = 3), and professional mentoring and/or advising (Mdn = 3) (p < .05).

Impact on Work/Life Balance