On the Ubọ-Aka of the Igbo: An Interview with Gerald Eze*

Quintina Carter-Ényì

KEYWORDS: lamellaphone, ubọ-aka, Igbo, organology, tuning

ABSTRACT: Most scholarship on lamellaphones, such as the excellent work by Paul Berliner and Cosmos Magaya in The Art of Mbira (2019), focuses on Zimbabwean practices. However, much of the African diaspora practice in the Caribbean and Americas is related to (1) West African musical practices, and (2) the commercial marketing and distribution of the instrument to Europe and North America as a “kalimba” by ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey (Tracey 1972; Moon 2018). This article presents an interview with Gerald Mmaduabuchi Eze, a music lecturer at Nnamdi Azikiwe University in Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria, recorded on November 1, 2021 in Enugu city. A performer and scholar, Eze presents a practical and academic knowledge of a lesser-known tradition of lamellaphone making and playing: the ubọ-aka of the Igbo of southeastern Nigeria. Kubik and Cooke (2019) note that “The ubo-aka of the Igbo people, exceptionally for the [Central and West African] region, has metal tongues.” Contrary to the mbira, which often has the lamellae and soundboard (vibrator) placed inside a gourd resonator and held inside by the performer, makers of the ubọ-aka conventionally permanently affix the vibrator to the resonator, which is made of a hollow cross-section of hardwood in the example instrument presented in this study. In our conversation, Eze touches on traditional practices including religious contexts, instrument design and tuning, his contemporary performance practices and the potential to preserve and maintain the tradition of ubọ-aka playing through African-centered music education and knowledge transfer.

PEER REVIEWER: Maduabuchi Sennen Agbo

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.7

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

[1.1] I have been making lamellaphones (also known in English as thumb pianos) since 2017 and offered instrument-making workshops at the African Studies Association in 2018 and the Society for Music Theory in 2019. Most scholarship on lamellaphones, such as the excellent work by Berliner (2019) and Berliner and Magaya (2020), which focuses on Zimbabwean practices. However, much of the African diaspora practice in the Caribbean and Americas is related to West African musical practices, and the commercial marketing and distribution of the instrument to Europe and North America as a “kalimba” by ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey (Tracey 1972; Moon 2018). As I studied the literature on lamellaphones, I became more interested in my culture’s own version of the lamellaphone, which in Igbo we call the “ubọ-aka.” I had the opportunity to interview Gerald Eze, a music lecturer at Nnamdi Azikiwe University on 1 November, 2021. Eze is among a few scholar-artists who are revitalizing the instrument, another being Emmanuel Nwankwo (Ezeani 2021).

2. Overview of the Ubọ-aka

Example 1. Gerald Eze’s ubọ-aka made in Nri

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Still from an interview with Gerald Eze of Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Anambra, Nigeria, November 1, 2021

(click to enlarge)

[2.1] Example 1 shows Eze’s ubọ-aka, which is made of hardwood, likely iroko, by craftsmen in Nri, Anambra state.(1) The ubọ-aka is a traditional Igbo musical instrument classified as a lamellaphone (Lo-Bamijoko 1987). The instrument holds a significant cultural and historical value within the Igbo music history but has gone out of use in most of the present Igbo communities. Most information I was able to collect is about the Nri community of Anambra state through the interview with Eze, an indigene of the town of Umuchu, in the Aguata local government area of Anambra. Nri is a significant historic place in the history and mythology of the Igbo people as a cultural center, particularly because of the Nri priests and oracles’ leadership in odinaani (or odinala), which comprises Igbo religion and spirituality and related customs. The importance of the ubọ-aka for the Nri people in traditional practices, including prayer and meditation, is emphasized in Ezegbe’s dissertation (1977). Eze, a current player of the ubọ-aka, provided information that contributed to shaping my exploration of the ubọ-aka. His instrument from Nri served as the model for my organological experiment. Example 2 shows Eze holding his instrument. In Spring 2024, I produced an ubọ-aka using a laser-cutter and materials purchased on Amazon at my home in Athens, Georgia. According to Eze, the ubọ-aka has a unique construction and playing techniques that reflect its cultural importance to the Igbo. These make it a compelling subject for organological study. The fact that the literature on the ubọ-aka is sparse and its physical presence is decreasing makes this an endangered material knowledge.

[2.2] Lamellaphones are classified under the category of idiophones by Hornbostel and Sachs (1961), who describe this category as musical instruments that make their sound by vibrating by themselves following an impact, such as striking or plucking. The Igbo people have a different method of categorization. According to Lo Bamijoko (1987), “ubọ” describes an instrument that is plucked, and “aka” means hand. The name therefore means “hand-plucked” and could be confused with other instruments, such as string instruments, which are also hand-plucked. The instrument’s name not only describes how it is played but also indicates how it is used. The ubọ-aka is an instrument used more for private leisure than large gatherings. Another Igbo idiophone is the ogene, which is similar to the western “cowbell”. The information gathered in this research is useful for modern generation of Igbo people such as myself who often misconstrue the term “ubọ” for anything shaped and played like the guitar, like the ubọ-aákwarà. In Affa, my Igbo hometown in Enugu state, I was only able to find the ụbọ-aákwarà with one family who have saved in their home where it is preserved it to show people as evidence of its existence. They no longer play it, as both the repertoire and occasion for playing it were long lost.

[2.3] The ubọ-aka serves as a medium of communication, transmitting the society’s folkways and traditions orally from one generation to another. The music conveys information, storytelling, proverbs, and idiomatic statements, allowing the listeners to learn about the mores and norms of the society. Additionally, the ubọ-aka is a symbol of masculinity and manhood, reflecting the patrilineal nature of social organization among the Nri people. It also plays a role in socialization, as it is used for leisure and relaxation, and is associated with courtship and marriage, conveying love and expectations in married lives.

[2.4] While the Igbo have many female deities, such as ani the earth goddess, leadership roles within religious and musical practices are often male. This is the case with the Priests of Nri. Chukuemeka Ezegbe’s 1977 dissertation explains the religious beliefs and practices associated with the ubọ-aka in Nri, including its use by the well-known Nri priesthood which had wide influence throughout northern Igbo land in pre-colonial times (33–44). Ezegbe also notes that there are folktales that warn against “over-indulg[ing] in playing ubọ-aka or other related instruments such as oja (flute), ụbọ-akwara (seven string harp) which are believed to possess the power of attracting spirits” (46).

[2.5] Furthermore, the ubọ-aka has the potential for inclusion in African music education in schools, colleges, and higher institutions of learning. It can be used to teach traditional scales, melodic and rhythmic patterns, interval relationships, and the Igbo tonal language due to its eight metal keys, which, according to Eze, are linguistically tuned and representative of the Igbo traditional modal structure. As an ancient tradition of lamellaphone making and playing, ubọ-aka music may be a basis for increased understanding of the lamellaphone throughout the African diaspora, including the Caribbean and the Americas.

[2.6] However, the significance of the ubọ-aka is also limited by factors such as the loss of much of its music following the death of traditional performers and the effect of social change, which has prevented modern youths from actively participating in ubọ-aka music. Additionally, there is a lack of literary surveys in the field, and the history and evolution of the instrument are not well-documented. Despite these limitations, the ubọ-aka remains a valuable cultural and musical artifact with deep-rooted significance in Igbo society.

3. Why the Ubọ-aka is Unique

[3.1] Gerhard Kubik and Peter Cooke’s entry on lamellaphones in Oxford Music Online mostly focuses on the traditions of southern and eastern Africa (Kubik and Cooke 2001). The entry does list the ubọ-aka in a table of African instruments but does not describe the ubọ-aka’s tuning. Kubik and Cooke note that the ubọ-aka is unique within the eastern Nigeria and Cameroon grasslands region for having metal tines. Therefore, this write-up provides novel information on the tuning of the ubọ-aka partially based on an interview with Eze, and the recorded practice of famed ubọ-aka recording artists Chief Akunwafor Ezeigbo Obiligbo. The following is an excerpt from Kubik and Cooke’s (emphasis mine) entry on Eastern Nigeria and the Cameroon grasslands:

This is a cohesive distribution area with a long history. The predominant material for constructing the instrument comes from the raffia palm. The soft pith of a raffia leaf stem is used to construct its body, while the tongues are cut from the hard outer skin. The box-shaped ‘Calabar’ lamellaphones from the coast of eastern Nigeria generally have Nsibidi ideographs carved on them. A ‘chain stitch’ holding the lamellae in place is also characteristic of many instruments from this area.

The Tikar and the Vute in the Cameroon grasslands also have raffia lamellaphones. Among the Vute they are tuned in paired octaves. The ubo aka of the Igbo people, exceptionally for the region, has metal tongues. The soundboard is firmly attached to the gourd-resonator, and has crescent-shaped openings on either side of the lamellae into which the player can put his hands. The organological characteristics of the Bini’s asologun include a metal chain laid across the lamellae to cause sympathetic resonance.

[3.2] In Nigeria, the instrument would be made of a medium hardwood like iroko (African teak wood) with iron tines. I note that Eze’s ubọ-aka has a gourd ring with a wood top and bottom, differing from designs shown in Ezegbe (1977) and described by Kubik and Cooke (2001). He also installed a piezoelectric sensor pickup for amplification and application of effects processing (which is not traditional to pre-colonial practices).

4. Repertoires

Example 3. Transcription of the opening of an ubọ-aka performance by Gerald Eze on November 30, 2021

(click to enlarge)

[4.1] Igbo ubọ-aka music is an oral tradition maintained through intergenerational transmission and rote learning. However, Eze is among a small group of ubọ-aka players in Anambra state who use standard music notation to record and transmit ubọ-aka pieces, particularly the purpose of teaching the instrument. The transcription shown in Example 3 is not by Eze but is that of music he played during the interview. Jonathan Eldridge II of Morehouse College prepared a transcription in standard music notation. I will be gathering more songs in the future; for now I have three. The song utilizes a minor scale, emphasizing a droning pitch of la, the first note of the scale. In Nigeria, la-minor is commonly known (not do-minor). Additional transcriptions are available in the Appendix for a total of three recording excerpts from the interview.

5. Tuning

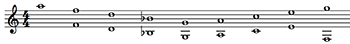

Example 4a. The Two Octave or Double Step Ubọ-aka which is tuned to the F Major diatonic collection

(click to enlarge)

Example 4b. Diagram for the Two Octave or Double Step Ubọ-aka which is tuned to the F Major diatonic collection

(click to enlarge)

[5.1] Eze sent me the following tuning description in 2024 which indicates F Major as the instrument’s tuning. Eze’s written description of the tuning and the photograph of the tine arrangement is the basis for Example 4a and Example 4b. However, the transcription in Example 3 is of Eze’s playing during the interview in 2021 and indicates an E major/C♯minor tuning The transcription was made by Jonathan Eldridge, who has perfect pitch. I note that F major and E major are one semitone apart, so maybe Eze has retuned his instrument over the past three years. The following is Eze’s written description of the tuning:

The one octave ubọ-aka is tuned to

Solfa(2): d r m f s l ta [flat] d’

Or “cross/alternative mode”: s l t d r m f s [hypo-ionian]

Ezeigbo Obiligbo’s tuning often has the seventh note a tone to the Octave. Sometimes the third would also be flat, and this suggests similarity with blues music. Using the alternative tuning also allows me to play music with this same ubọ, for instance in key

F G A

Generally, the tuning of the Ubọ-aka can vary; it can start from any frequency and be arranged in any style the performer may want. I have taught my students the tuning principles and they are free to tune in any style they want. However, the size of the calabash and the length of the prongs determine the range that is possible from the lowest note to the highest note. Once the lowest note and the highest note is determined, arranging the prongs to any tuning of choice is more like setting the prongs in a style that enables one to express in a certain way. The kind of melodic and harmonic expressions one can produce with the cross tuning (s, l, t, d r m f s) is different from those one can produce with the standard diatonic scale (d r m f s l ta d) or the major scale variation of it which can be achieved by tuning the “taw” note upwards (d r m f s l t d’).

6. Translation of Interview

|

Igbo |

English |

|---|---|

[Eze demonstrates the instrument] | [Eze demonstrates the instrument] |

Carter-Ényì: Daalu nke oma. Biko gosigodu anyị iru ihe a ị kpọrọ, | Carter-Ényì: Thank you so much. Please show us what you just played, |

gosigodu anyị ihu ya ka anyị fụ ya | show us the face let us see it |

Kee ihe a na-akpọ ya? Kee ihe o bụ? | What is it called? What is it? |

Eze: Ihe a m ji n’aka bu ubọ-aka, ubọ-aka | What I’m holding is called ubọ-aka, ubọ-aka |

ọ bụ ngwa ndị Igbo | It’s an Igbo musical instrument |

Oo ihe ndi igbo ji eme onwe ha obi añụri- ọ bụ ihe ... | It’s what the Igbo used to entertain themselves and be joyful in the past |

Ee, o dịrịrị n’ala igbo na mbụ, o tego rii ọ dị | It has been in existence in Igbo land, it has been long in existence |

Mana emechazii ọ dị ka ọ na-ana ana | But it appears it is now going into extinction |

Carter-Ényì: ọ bụ ihe i na-ekwu kita bụ na ọ dị ya? | Carter-Ényì: From what you are saying now, is it still available in the society? |

Eze: ọ dị ya, ọ ka dịrịrị | Eze: Yes, it is still very much around |

Mana ndị na-eme ya, ndị na-akpọ ya erizighị nne | But the players, are not many |

ọ kwanu ya ka munwa ji mụta ya, jiri ya na- akpagharị | That was why I learnt it, taking it to places |

Na-enye ya ụmụakwụkwọ m, na-egosi ha ya | Giving it to my students, showing it to them |

Naa, ndị otu egwu m ejirikwuo ya na-akpọ egwu | And my band also uses it to perform live music |

O nwe ebe a kpọrọ m ka m kuzie piano, nke ndị ọcha, | Anywhere I’m called to teach piano, the Western piano, |

Ka m kuziere ụmụazi piano, | To teach children piano, |

M kuzie kuzie, | After teaching the piano for some time, |

O zuo, o ruo ihe dị ka onwa nabọ, | Once it gets to about two months, |

M were ubo-aka tikwuo, | I will add ubọ-aka to the lesson, |

Si ha ngwa gotere ụmụazi a ụbọ-aka, | And then suggest to them to buy ubọ-aka for the children, |

O na-aga | So, it keeps going |

Emeketego ya, ọtụtụ ụmụazị amutago ya na ọka | Continuing this practice, a lot of children have learnt it in Awka |

Ọtụtụ ụmụakwụkwọ amụtagokwa ya na UNIZIK, | Some students have also learnt it in UNIZIK, |

Nnamdi Azikiwe University, ebe m na-akuzi | Nnamdi Azikiwe university, Awka, where I teach |

M werekwa ya na-aga ihe dị ka orụ obodo, | I also take it to impact on the community, |

Ihe ndị ọcha na-akpọ community service, | What the English people call “community service,” |

N’Umuoji. | In a town called Umuoji(3) |

Abụrọ m onye Umuoji, | I’m not from Umuoji, |

Mana e nwere m (Dr. May Blossom Brown) onye nyere m ebe m na-araghu. | But someone (Dr. May Blossom Brown) gave me where to stay at Umuoji. |

M bịa ebe ahu, | Each time I go there, |

Mkpọkulota ụmụazi na akuziri ha ụbọaka | I bring children together to teach them ubọ-aka |

Ndị nke ahu, ụmụazi ka uche m dị na ya | In this kind of teaching, I am more interested in teaching the young |

Ihe m ji eme ya otu a bụ na onweghị otu ọzọ | This is because there is no other way to sustain the practice |

M dee ya ede n’akwụkwọ, | But if I just write it in essays, |

M na-edekwa ya ede, | I write essays about the ubọ-aka |

Mana m mee so i de ya n’akwụkwọ | But when I just write only Academic essays |

Ọ dị ka i sị: | It will be like saying: |

“Hei! mmiri adịrọ mmiri , mmiri adịrọ mmiri adịrọ!” | “Hey! There is no water, there is no water!” |

M nọkwa n’iru taapụ. | Yet, I am standing in front of the tap. |

“Mmiri adịrọ”, meghenu taapụ ka mmiri dịrị. | Yes, “there is no water,” so just open the tap and let the water flow. |

M na-ewegara ya ụmụazi | I actively take it (the ubọ-aka) to children |

Na emekwa ya n’egwu m | I use it in my musical ensemble |

Na-akpọkwa ya n’egwu | I perform it in songs |

Mmekata mekata, ihe dị ka ndị BBC Igbo | From these practices, organizations like the BBC Igbo |

Ma ọ bụ ụfọdụ ndị midia, | Or other media groups, |

Afu ya, | Would see my work, |

Ndị na ezisa ozi, | That is, media groups that spread news, |

Sị ka ha zie ndị ụwa, ka ha makwara na ụdị ihe a dị | They share it with the world, so that people know it still exists |

Ndi mmadụ a fụ ya sị heei! Nke a nke a | Then people will see it and express excitement, saying this and that |

M sị otu a na-aga | This is how I keep progressing with the music |

Mana ewezuga onye mụ na ya na-arụ ya | But apart from the person I produce the ubọ-aka with |

Amakwaha m ebe m fugoro ya n’ala Igbo | I don’t know where I have seen it in Igbo land |

N’Eke-ọka n’ọka, | At Eke-Awka Market in Awka, |

Ọka Sautu Lokal Gooment nke Anambra Steeti | Awka South Local Government of Anambra State |

Onweho ebe a na-ere ihe egwu ofu mkpuru | In the markets where traditional Igbo musical instruments are sold |

Ụbọaka dị na ya | one cannot find any ubọ-aka. |

O gosii na ndị mmadụ enwezighị ihee, uche ha adikebezi na ya | This shows there are not many people do with interest in the ubọ-aka |

Carter-Ényì: ọya ka o ji dịrị gị mkpa ikuziri ụmụaka? | Carter-Ényì: Is this why it is important for you to teach children? |

Ajuju m Chọrọ iju gị ọzọ bụ enwechara ihe ndị ọzọ ndị igbo na-akpọ, | There are other instruments the Igbo people play . |

Mana kee Ihe ojiri dịrị gị mkpa ka i welite ụbọaka a, kpasaba ya? | why is it very important for you to showcase and promote ubọ-aka? |

Eze: Mm, ka ndụ m dị, | Eze: Mm, in the natural flow of my life |

Ọ bụ ihe ndị a dị mkpa uche ndị mmadụ anaghị agakebe na ya, bụ ihe na amasi m iche | It is these important things that people’s mind does not go to that interests me most |

O tu a ha ka ndụ m dị | That is how my life is |

Ụbọaka a, ka m fụrụ ya izizi, | when I first encountered the ubọ-aka, the sound interested me |

Ọ ma mma n’anya, tọkwa m ụtọ na ntị | It was pleasant to my eyes and sweet to my ears |

Mana a chọpụtara m na ya bụ Ife na-ewe ọtụtụ oge na ọtụtụ uchu, mmadụ imụta ya | But I found out that it takes a lot of time and commitment for one to learn it |

I ma ọ bụ ihe ndị n’ee, ihe ndị n’epe mpe na-adị ka o nweghoo, ọ ragha ahu, | You know it is the seemingly small or easy things |

Ọ ya bụ Ihe ndị na-ara ahu n’uwa | They are the things that eventually turn out to be difficult |

M tinye uchu were mebe ya. | So, I committed myself to do this |

M fụkwa na m menwụrụ ya. | And I found out I could do it. |

Ebe ọtụtụ ndị emeghughị ya, ka m menwụrụ ya, | Since many people are not able to practice this, and I could do it |

Ka m meruzie nụ ya gaba | Then let me keep on doing it |

O nweziri oge o ruru, m sị mba noo munwa ya na akpọzị ya, | At a time, I firmly decided that I will be performing it, myself |

M ga na-ebughari ya; m ga na akuzikwa, na-egosikwa ndị mmadụ | I will carry it to places, teach it, and show it to people |

Na emekwa ihe ndi a m na-eme | And continue doing all these things I do, |

Mana mụnwa gana akpọ ya | But I will be performing it as well |

Ya bụ Ihe, o digho fechaa, o digho fechaa | It not easy, it is not easy |

Ama m ihe m ji ekwu; | I know why I’m saying it; |

Ọ garaadị fecha, ọ ka bụ ịpụta i ga na-afụ ya ebe nịịle | If it were easy, it could have been seen everywhere |

O digho fechaa | It is not easy |

Carter-Ényì: O nwekara ndị ọzọ n’Afrika na-akpọ ihe yiri ihe a? | Carter-Ényì: Are there other people in Africa who play what looks like this? |

Kedụ ihe a na-akpọ ya and kedụ ka ha si emekọrịta? | What are they called and how do they interact with each other? |

Eze: Ndị Zimbabwe, mụ na ọtụtụ n’ime ha dịkwa na mma | Eze: I know some Zimbabwe people |

Ndị Mbira Center na Zimbabwe, | The Mbira Center in Zimbabwe, |

Mụ na ha na-arụ ọrụ eri, ee, anyị bidoro afo gara aga | I have been working with some of them since the beginning of last year (2020) |

Ihe a na-akpọ Mbira Festival | In events like the Mbira Festival |

O nwekwa nke ọzọ ha na-akpọ Pan African Mbira Festival | There is also another event that is called, Pan African Mbira Festival |

Hanwa (ndị Zimbabwe) na-akpo ya “Mbira” | They (the Zimbabweans) call it (the ubọ-aka) “Mbira” |

Ha elego anya fụ na m bụ nwaikorobia ihe a na-amasi na-akpọ ya | They saw that I’m a young man who is interested in this ubọ-aka music |

M ghotakwa ka esi eji igwe eji ekwu okwu (fonu na komputa) were na-ezisa ụdị egwu ụbọaka a | And that I understand how to use the new media to spread awareness of this ubọ-aka music |

Ha e wee kpọtụrụ m, m na ha a na-arụ | So, they called me to work with them |

Ha nwa na-akpọ ya Mbira | They call it mbira |

Be ha, ọ dị ri’nne, | It is popular in their place |

Ọ na-adị m ka ọ dị be ha, ka Mbira ahu o dị be ha karia guitar. | It appears that mbira is more popular and available in Zimbabwe than the guitar. |

Maka o di rinne, | Because it is found in many places |

Ha ejidighị ya egwu egwu | They do not play with it |

And ha na ndị mmuo na-eji ya akpakari ụka. | And they use it to communicate with the spirits |

Ndị Shona na Zimbabwe, ha chọrọ ifu ndị nna nna ha ndị ochie gagoro aga, | When the Shona people of Zimbabwe want to commune with their departed ancestors, |

Ọ bụ mbira ka ha na etinye aka na ya. | It is mbira that they use |

O nwekwa ndị na-akpọ ya Kalimba, ndị Cameroon | Some people call it Kalimba, people of Cameroon |

O nwekwa ndị na-akpọ ya Ilimba (ndi Tanzania) | Some people call it Ilimba (Tanzanians) |

Nwekwa ndị na-akpọ ya, I think o na-adi m ka o nwekwaa ndị na-akpọ ya Marimba | Some others call it, I think that there are some people who call it Marimbạ |

Mana nke doro m anya bụ Mbira, Ilimba, na Kalimba | But I’m sure of mbira, ilimba and kalimba |

Ilee anya, chee ka ndị a si akpọ ụbọ (ụbọaka) nke ha, ọ dịwagaa iche | when you look to see how they play their ubo (ubọ-aka), it is unique |

O buho otu e si ahazi, eee, ụda, ihe igwe a eji akpọ ụbọaka anyị, ka ndị Zimbabwe si hazi nke ha | It is not the same way that we arrange the metal prongs of our own ubọ-aka that the Zimbabweans arrange theirs |

Ihe a na-akpọ tuning, | What we call tuning, |

Tuning ya dị iche n’iche | Their tuning system is unique from ours |

O tu anyị si hazi nke anyị dị iche, e tu ha si hazi nke ha dị iche | The way we tune ours is unique, the way they tune theirs is unique |

Ọ bụ ya ka o ji a bụ mgbe ụfọdụ akpọ ya Thumb Piano, ọ ra ahu | That is why it is confusing to generalize all as Thumb Piano |

Ị sị Thumb Piano, kedụ nke i na-ekwu maka ya | When you say Thumb Piano, which of them are you referring to |

Ọ bụ mbira, ka ọ bụ ụbọaka ka ọ bụ ilimba ka ọ bụ kalimba? | Is it the mbira, or ubọ-aka or ilimba or kalimba? |

Ihe a bụ afa digasi iche iche a na-akpọ | These are different names they are called |

O nwekwalụ ebe ihe a dị n’Ikwere, | You can also find this (ubọ-aka) in Ikwere |

Ọ dị rinne | It is popular there |

Ihe a na-akpọ ya bụ Eri ọbọ | They call it Eri Obo |

N’ikwere, ee, ebe wụbụ Igweocha, Port Harcourt | In ikwere, the place that is formerly Igweocha, now Port Harcourt, |

A na-akpọ ya rii nne | It is a common practice to play it (ubọ-aka/Obo) |

Jimi Conta, eee, Jimi Conta bụ ofu n’ime ndị ama ama n’akpọ ya | Jimi Conta, eee, Jimi Conta is one of the popular performers of the Eri Obo |

Obo, Eri ọbọ ka a na-akpọ ya | Obo (ubo) they call the music Eri Obo |

Nke aha kwa, ka e si ahazi igwe eji akpọ ya dị iche na ụbọaka nke ndị Enugu, Anambra, Imo | Their tuning system is also different from ubọ-aka of Enugu, Anambra and Imo people |

Carter-Ényì: Gwam e tu o si bụrụ ndị Igbo bụ ndị na akpọ ụbọaka a nunwa? | Tell me how it is only the Igbo that play this ubọ-aka |

Eze: Ndị igbo | The Igbo people, first of all, it is called ubọ-aka |

Aka bụ aka mmadụ, | Aka means someone’s hand, |

Nee aka m leenu aka m, | Look at my hand, look well at my hand, |

Ụbọ bụ ihe a na-akpọ akpọ, | Ubo means something that is plucked |

Ndị Igbo nwere ụbọ-akwara | The Igbo has ubo-akwara |

Ụbọ, nke eji akwara were kwe | Ubo that is made from the strings of palm tree |

Nke ahu alago laa pii | That one has completely gone extinct |

O teene m chọbara ya na achọ onye ga-egosi m ka ọ dị | For long, I have been looking for it, looking for one who will show me how it appears |

Maka na afubeghị m k’o si ada na ntị | Because I have not come to know how it sounds |

M nụ ka o si ada na ntị, egosi m ka ọ dị, ọ ga-adaba | Once I hear how it sounds with my ears, if I am shown how it is, it will be great |

Egosi m ka ọ dị, o ga-adaba | If I am shown how it is, it will be great |

Nke ahu bụ ụbọ-akwara | That one is called ubo-akwara |

Ụbọ bụ ihe a na-akpọ akpọ | Ubo is something that is plucked |

Ọ bụrụ na ọ bụghị ndị Igbo nwe ya ọ gaghị aza afa ahu na mbụ | If it did not originate from the Igbo people, it would not have that name |

Nke mbu bụ na ọ ụbọaka, | First thing is that it is ubọ-aka |

Gosi na o ihe ndị Igbo were tinye be ha | To show that it something the Igbo have put in land |

Were ya na-agwa onwe ha okwu | And they contemplate life in conversations with it |

Were ya na-anọrị ọnọdụ | They use it for social purposes of relaxation |

Were ya na-atughari uche | They meditate with it |

Ọ bụ ndị Igbo nwe ụbọaka | It is the Igbo that owns ubọ-aka |

Carter-Ényì: E tu a nunwa i siri mata maka ụbọaka a nunwa, | Carter-Ényì: From the way you have come to know this ubọ-aka, |

O nwere ihe gosiri gị e tu ndị Igbo si wee nwekọrịta ya, With ndị ọzọ nọ n’Afrika? | Is there anything that shows you how the Igbo people own it together, with other people in Africa? |

Kedụ ife o jiri bụrụ sọsọ ndị Igbo na ndị gbasara ụmụ afo Igbo dị ka ndị a ị kpọrọ afa kita n’Ikwere, | Why is it that it is the Igbo people and those connected to the Igbo, just like those you mentioned now who are from Ikwere, |

Ha bụkwa ndị Igbo bụ ndị na akpọ ihe a | Who are also Igbo and also play this ubo |

Ndị Yoruba anaghị akpọ ya? | Does the Yoruba people not play it? |

Ndị awusa anaghị akpọ ya? | Does the Hausa people not play it? |

Ha nwekwe nke ha? | Do they have their own? |

But ka m gwara gị gwa m ndị ọzọ na-akpọọ ya, | But, when I asked you to tell me other people who play it, |

Ị sị na ọ bụ ndị nọcha outside Nigeria | You mentioned those who are outside Nigeria |

So, o nwe ihe i mutara | So, have you learnt anything about |

O nwe ihe ọ bụ kọnetiri anyị na ndị ahu? | Is there any connection between us and those people (outside Nigeria)? |

Eze: Haaa Ndị Yoruba nwekwara Agidibo, ha nwere Agidibo | Eze: The Yoruba people have Agidibo, they have agidibo |

Ee, ọ dị n’ụdị nke ya | Eh, it is in its own unique style |

Ọ bụkwa ofu ihe a e tu ndị Zimbabwe si nwe nke ha a na-akpọ mbira | They are all the same type of instrument, the Zimbabweans call their own mbira |

Na Shona, na Zimbabwe, Mbira ka a na-akpọ ya | In Shona, in Zimbabwe they call it mbira |

Na Yoruba, Agidigbo | Yorubas call it Agidigbo |

Ndị be anyị nwe ya | Our people also have it |

Nke bụ eziokwu bụ na ndị gboo e jeka ije | The truth is that our ancestors traveled a lot |

Ndị oji ndi gbo, echiche ha tọrọ atọ | Our ancestors possessed enduring thoughts |

Anya rulu ha ana. | They were down to earth. |

Akọ na uche akọrọ ha. | They do not lack wisdom. |

Ọ na a bụ ha na-eje njem, | It happened that when they travel, |

Ọ dị m ka ọ site na njem | It seems to me that it is through traveling, |

Ka ihe a si gazuo Afrika | That this music spread through Africa. |

Maka ndị nke wete nke ha | Because when each community, collects their own |

Ọ dị n’ụdị ha | It is in their own unique style |

Ha agaghị eje wete ya otu ahu, wenata ya, ọ di. | They do not bring it back the way it is in another place, to make it available |

Mana ihe mu a maa kọwazi bu, | But what I cannot explain is, |

Ndị si na aka ndị we mụrụ. | Who learnt from the other |

Mana nke dolu anya | But what is clear enough, |

Bụ na o site na njem | Is that it is through traveling, |

Ka ihe a si gbasa | That this knowledge spread. |

Maka ị checkie, ị nee anya, | Because when you think about it, |

Ofu ihe a ka ọ bụ. | It is the same thing. |

ị nee anya, ofu ihe a ka ọ bu. | If you observe, it is the same thing. |

Ndị Igbo, munwa onwe m ji ụbọ a, akpakọ, ee | Igbo people, I also, holding the ubo, |

Mu onwem, mụ na ndị mmụọ ji ụbọ akpa. | I myself, I communicate with the spirits through ụbọ (ụbọaka) |

Ị nekwa, ịfụ na ọ bụ ofu ihe a a na-eme na Shona, na Zimbabwe. | If you observe, it’s the same thing the Shona people of Zimbabwe do. |

Ọ dị m ka ọ bụ njem. | It seems to me like it’s through traveling. |

Ndị be anyị mgbe ahu, ndị gboo awụghọ | Our people then, our ancestors do not |

Ha jee njem, ha eje kọpilụ ka ndị si eme, tọ na ya | Travel to copy the way of life of other people and stick to it. |

Ọ ha jee, ha amụta, nọta n’ụnọ, | The case is that when they travel, they learn, come back home, |

Tọ ntọ ala ya e me | Create structures that will make |

Ka ihe aha dimma ha muta, bulụ nke ha, kpọm kwem. | What they learnt to be good, to become theirs specifically. |

Ọ bụ ya ka ha jiri were ụbọaka, ọ bụlụ nke Igbo. | This is why they have adapted the ubọ-aka to be for the Igbo |

Ị nekwa ya anya, ifu ihe dị iche. | If you observe, you will see the uniqueness. |

Ọ nwe akụkọ akọrọ m n’obodo anyi, | There is a story told in my hometown |

Na eji ya (ụbọaka) eduje ndị | That it is used to accompany |

Anụtachaa nwanyị, ị bịa n’Umichu nụọ nwanyị | After the wedding ceremony, if you come to Umuchu to marry a woman |

Ndị Ibughubu Umuchu ka ha si na-akpọ ya rinne mgbanwu. | It is said the Ibughubu people of Umuchu played the instrument a lot then |

Ị bịa n’umuchu nụọ nwanyị, | If you come to Umuchu to marry, |

Abani mgbọsi ahu, makana ka mkpọtụ we benata, | The night after the marriage, for the noise to be less |

Ka sound ya we na agami kwu agami, | So that the sound will be audible and travel far |

Ụbọ ka ha ye-eji kpọlụ nwoke ahu bia nụta nwanyi na ndi ọgọ, | They use the ubọ-aka to accompany the groom and in-laws to the wedding |

Kpọghalia be ndị nwanyị ahu, | Around the house of the bride’s relatives, |

Egosi cha ha, ha a naa, mgbọsi n’esote ya. | After showing them around, they leave the next day. |

Ihe ihe a pụtara bu; ọ dị ụzọ ihe n’abu, | What this practice means is; it means two things, |

Ị jekata ịje, pụta ihe dika n’Uga, tọ, | When you are traveling and you come to a place like Uga(4) |

Chi jinarị gị, | And the night has come upon you, |

ị jisizie ike rute n’Umuchu, | Once you manage to get to Umuchu(5) |

Ị malụgo be ndị ọgọ gị, ebe i ya-eje zuo ike. | You already know the house of your in-laws where you can go and rest. |

Ị ba be ofu onye. | You just enter the house of one of them |

Ifugo ya; hotel, hospitality. | You see it; hotel, hospitality |

Ọ dị rii na ani Igbo. | It has always been natural to the Igbo |

Ọ ka ndị mbụ si debe ndụ. | This is how the ancestors planned life |

Ụbọaka a bụ ihe a na-akpọ, na-agụ egwu, | ubọ-aka is the musical instrument that is played, while people sing |

Wee na agaghari ụdị agaghari a. | While the in-laws are shown the bride’s relatives |

Ndị b’anyi na-abụ ha puo mgbe ahu, | When our ancestors travel in the olden days |

Ha mụta ihe, ha nọta, e jiri ya na-ahazi ndụ. | When they learn something, they return, and employ that thing to make life better |

Kita dizi m ka ọ | Now it seems to me that |

Anyi atunata ihe ahu atunata otu ahu ọ dị. | We import things the way they are from the place we have traveled to |

A nadighi eche ya n’echiche. | No one hardly applies thought to it |

Atu nata ya, a fanye ya na ndụ anyi, | When we import it back, we impose it on our lives |

Ọ mairi fanye onwe ya. | And it ends up imposing itself |

Ọ dikwa m ka o so n’ihe na-etisa obodo. | I feel it is one of the things that disintegrates the (Igbo) society. |

Carter-Ényì: Afuru m ka I na hazi ihe a, | Carter-Ényì: I saw you tuning the instrument. |

Gwam e tu ndị Igbo si a hazi nke ha. | Tell me how the Igbos tune their ụbọaka. |

Eze: Mmm, Onye mee ka ụbọ a gazuo, | Eze: Mmm, the person who made the ụbọ popular |

Igbo nịịle, n’ụwa nịịle, | Across the Igbo land and the world, |

Bukari Obiligbo. | Is mostly Obiligbo |

Obiligbo agbaka mbọ. | Obiligbo did a lot |

Ezigbo Obiligbo, onye Nteje. | Ezigbo Obiligbo. From Nteje. |

Ọ na-abụ, ị gee egwu ya, | If you listen to his music, |

I ya-anụ ihe, I nụ ka ọ si hazi ya | You would hear something, how he tunes it (ubọ-aka). |

M kpọ egwu ya, kpọtaya, | When I play his music, and play it well, |

M wee kpọzie nhazia | I will now play the scale |

Site na, nke mbụ, igwe nke mbụ, ruo n’igwe nke ikpeazu. | From the first, the first prong, to the last prong. |

(Proceeds to pluck the ụbọaka; lowest pitch first, then the highest pitch) | (Proceeds to pluck the ụbọaka; lowest pitch first, then the highest pitch) |

Mana m ga-akpọgodu k’egwu Obiligbo na-adi. | But first of all, I will play Obiligbo’s music the way it is. |

M nwete ya, m ma na m hazite ya. | When I get the music, I will know that the tuning is correct. |

Ọ ka e si ahazi ihe gbo | That is how tuning is done in the olden days. |

Ị hazie ya, ọ bụlu n’ichọ iji ya kwuo okwu, | When you tune it, if you want to do speech surrogacy with it, |

Ị hazicha ya, ị kwuonu okwu ahu | After tuning it, you use it to say what you want to say |

Ihe ị kwuru dabaa, ị ma na ị hazitego ya. | If what you say sounds correct, then you know that the tuning is correct. |

(O na-akpọ egwu eji mara Ezeigbo Obiligbo na ụbọaka) | (He plays Ezeigbo Obiligbo’s musical standard on the ụbọaka) |

O tua ka egwu Obiligbo na-adịba. | That is how Obiligbo’s music normally is. |

Ị nezie anya, ị fụ na ụbọ a, ihe ọ ga enye gị bụ | When you listen, you will notice that the ubo gives you |

(Scale ascending and descending) | (Scale ascending and descending) |

(Continues playing the Ezeigbo Obiligbo ụbọaka standard) | (Continues playing the Ezeigbo Obiligbo ubọ-aka standard) |

O tu a ka ndị Igbo si hazi ya. | That is how the Igbos do it. |

Mana emeketezi, | But after some time, |

Mụ na enyi m nwoke, Emmanuel Nwankwo, | My friend, Emmanuel Nwankwo and I, |

Wee fụkwa na, e nwekwa ike | Noticed that, it is possible |

Agbakwunye ihe n’enu ya. | To add some prongs on top. |

Nke ndị Igbo gboo, anaghị adị ota a. | This was not the Igbo Ubo-aka was in the olden days |

Mana a sị ndị Igbo, ndị Igbo abụrọ ndị tochago nu, | But when you talk about Igbo, the Igbo people are not done with progress, |

Ndị Igbo bụ ndị ka n’eto eto | The Igbo people are still progressing |

Ndị nwere akọ n’uche | They are a people with deep thoughts |

Ndị na-etinye onwe ha, tinye uche ha n’ọlu | They are a people who apply themselves and their thoughts to work |

Na-eme ka ihe onye jekwudo, | Ensuring that the practices anybody encounters |

Ihe Agburu obuna jekwudo | The practices each generation encounters |

Eme ya, ọ ka mma, | Is enhanced to be better, |

O wee na-aga. | Therefore, the growth continues. |

E jeghị m asi, na nke a awuhọ nke ndị Igbo. | I would not say that this one is not the Igbo ubọ-aka. |

Maka ọtụtụ ụmụ Igbo akpọwago ya. | Because some Igbo people are playing it already. |

Mụnwa, na-eme ya. | I perform with it |

Ọ bụ mụ na enyi m nwoke, Emmanuel Nwankwọ | It is I and my friend, Emmanuel Nwankwo |

Bido, tinyebe nke a; | That started putting the additional prongs; |

Tinye ya, anyị wee na-akpọ ya. | We fix it, we then play it |

(Plays the two octave ụbọaka) | (Plays the two octave ubọaka) |

Ngwa nee ka anyị si hazi nke a. | Okay, now observe how we tuned it. |

(Plays the scale of the two octave ubọ-aka, ascending and descending) | (Plays the scale of the two octave ubọ-aka, ascending and descending) |

(Continues playing tunes on the two octave ubọ-aka) | (Continues playing tunes on the two octave ubọ-aka) |

Mgbe ụfọdụ, ọ na-enye m ohere ikpọ ya, dị ka mụnwa na-akpọ piano. | Often, it allows me to play it like the piano. |

Dị ka m a na, e, e, a na, a na | Just like I am, eh, eh, I am, I am |

Egwu mụ ete aka, nwee nkeji dị iche iche | My songs become longer, and have different sections |

Doo anya, tọ ụtọ. | Become clearer and sweet. |

(Plays the two octave ubọ-aka) | (Plays the two octave ubọ-aka) |

Ihea bu egwu (mmonwu) anyi na agu n’umuazi, | This is a (masquerade) folk song we sang when I was a child, |

“M ma emekwa ebere” | “I will not have mercy” |

“Ebere, ebere” | “Mercy, mercy,” |

“M ma emekwa ebere” | “I will not have mercy” |

Carter-Ényì: ọ otogbuo onwe ya, Daalụ (laughter) | Carter-Ényì: It is really sweet |

Ajụjụ ọzọ m ga-ajụ gị bụ, | Another question I would ask you is, |

Ọ kwa ị ma ndị Gambia, | You are aware of the people of Gambia, |

E tu ahu ha si we nwee ‘Kora’, | How they have the kora, |

Ọbụhọ mmadụ nịịle na-akpọ ya. | It is not everyone (in Gambia) that plays it. |

Ọ bụ ezinaulọ and ndị mụtalụ ha, | It is only specific families and the parents in such families |

Ndị so ha, bụ ndị nwe ike ikpọ ya. | And their apprentices that can play it |

Carter-Enyi: ọ ofu ife, n’ihe gbasalu ụbọaka, | Carter-Ényì: Is it the same thing for the ubọ-aka, |

Ka ọ di iche? | Or is it different? |

Eze: Mmm, ọ bụcharo ofu ihe. | Eze: Mmm, It’s not exactly the same thing. |

Mana ọ nwekwa ihe yitelu ya. | But there are similarities. |

Ị nee anya, | When you look into it, |

Kora ndị Gambia, | The kora of Gambia, |

Ihe ha na-akpọ onwe ha bụ ‘Jali’ | What they call those who play it is ‘Jali’ |

Ndị na-akpọ ya, Jali; Minstrels. | Those who play it, the Jali; Minstrels (Griots) |

So, and ha na-akọwa na, o nwelu ihe dị iche | So, and they are show that there is a difference |

Minstrels na musician. | Between minstrels (griots) and a musician. |

Na Gambia ị bụ a Minstrel, | To be a minstrel (griot) in Gambia, |

Dị ka ihe omimi | Is a deep thing |

Ọ dị ka onye | It is like a person with great intellect |

Maka ọ ha ka a na-akuziri k’obodo si bido; | Because it is the minstrel (griot) who knows the history of the community. |

“Kee onye, onye chiri mbu?” | “Who ruled the community first?” |

“Onye chiri, onye chiri ka a chichalu?” | “Who ruled next?” |

Ihe nịịle gbasara obodo aha, | The entire history of that community, |

A na-akwuzilie | They teach this history to generations in songs. |

Ya wụ ihe yara ahụ. | It’s not a common practice. |

Ọ dị ọnọdụ ka, na Jali na Gambia dika dictionary. | The ‘Jali’ of Gambia are like a dictionary. |

Ọ dị ka library. | He/she is like a library. |

Ị kpaghaa ya na music, ọ gụsisiba. | Once they are asked to perform music, they render historical accounts. |

So, ihe dị na ya bụ, | So, the thing about it is, |

N’ala Igbo, nke dị be anyị yitelu ya bụ, | What resembles it in the Igbo land is, |

Onye na akpọ ụbọ, | A person who plays the ubo, |

Ụmụ ihe nịịle a na dịkwanụ n’ọbara. | Things like this are mostly in the bloodline. |

Onye na akpọ ụbọ mụta nwa, | Once a person who plays the ubo has a child, |

Ndụ o biri, | The life he lived, |

Ka o si che echiche, | How he thinks, |

Ka o si meso mmadụ omume, | How he treats his fellow human beings, |

Udị ọru ọ nọ na-arụ, | The kind of work he does, |

Udị egwu ọ nọ na-ege, | The kind of music he listens to, |

Ọ ya aba nwa ya n’ọbara. | Will be in that child’s blood. |

Ọ ihe a na-akpọ DNA. | That is what is called DNA. |

So, ọ dị nwa ya n’ahu, karia ka ọ dị nwa onye ọzọ. | So, it becomes a part of his child more than the child of another person |

Nwa ya aha na-etokwa, jekwude ya ka ọ na-eme ihe a, | When the child grows and encounter him in performances, |

Ọ na-ene, maka asi nne ewu na-ata agba ya, | He will be observing, because our people say: When the mother goat is chewing, |

Nwa ya a na-ene ya anya n’ọnu, na-amụta. | The kid goat watches her mouth, and learns. |

Ọ nwerọ ụlọ akwụkwọ a na-akụ | There is no school where one knocks |

Kpọm kpọm kpọm kpọm, | “Kpom kpom kpom kpom kpom” (knocking sound) |

Bịa mụta ụbọ, | Come and learn the ụbọ, |

Bịa mụta ọja, | Come and learn the ọja, |

Bịa mụta ufie. | Come and learn the ufie. |

Ọ ị nọlụ n’obodo, | The point is, when you are in the community, |

Ị na-amụta ya. | You learn. |

Nwatakiri, nna ya na-akpọ ụbọ, | A child whose father plays the ụbọ, |

Ka nwere ohere ị muta ya karia | Has the chance to learn more than |

Nwatakiri nna ya anaghi akpọ ụbọ. | The child whose father does not play the ụbọ. |

Mana ọ dichaghọ otu aha nke ndị Gambia di. | But the family system is not exactly like that of Gambia. |

Nke wụ na ị ga-amacha akụkọ nịịle aha | Where you would be formally “trained” in all their history and stories. |

Nke ndị Gambia dị rii ka, | For the people of Gambia, |

Otua ka omenala ha dị. | That is how their tradition is. |

Nke anyị adịchaghị out a. | Ours is not exactly the same. |

Maka mgbe Obiligbo na ahanye Ajani nwa ya egwu, | Because when Obiligbo was passing on his music to his son Ajani, |

Mgbe Obiligbo na-ahanye Ajani nwa ya egwu | When Obiligbo was passing on his music to his son Ajani, |

O nwekwa ebe ọ bịa si, | There is a place he said, |

‘Onye emekwana ka Obiligbo n’egwu’. | Let no one do like Obiligbo in his music, |

Ndị Igbo, ị ma, | For the Igbo, you are aware that, |

A bịa na ihe gbasara ndọrọ ndọrọ ọchịchị, | When it comes to politics for instance, |

Anyị dị, Republican. | Our system of government is Republican. |

Onye owụna, anyị nwere ofu obi, | Everyone, we all have one heart, |

Mana onye ọbụna wụ onye Igbo nwe obi nke ya. | But everyone who is Igbo also has their own unique nature. |

Obiligbo wee dọ aka na-nti mgbe ahu si, | Obiligbo now made it clear in his music, saying, |

‘Onye emekwana ka obiligbo n’egwu.’ | ‘Let no one do like Obiligbo in music.’ |

Nya pụta, onye mụta ụbọ a, | What it means is that, when a person learns the ụbọ, |

Ya mụta ya n’udi nke ya, kpọba. | He learns it in his own style and performs it. |

So, ọ bụchaghọ ofu ihe na kora ndị Gambia. | So, it is not exactly the same with the kora in Gambia. |

Carter-Ényì: Ihe ọzọ m chọrọ ị mata bụ, | Something else I would like to know is, |

Kedụ ụdị n’ụdị egwu e nwelu ike iji, | What kind of songs can you |

Ụbọaka a nụnwa kpọ? | Play with the ụbọaka? |

E nwelu ike iji ya kpọ egwu ndị oyibo? | Can it be used to play non-African songs? |

Eze: Ihe nịịle dị n’echiche. | Eze: Everything is in the mind. |

Ebe uche gị rudebe, | Where one’s mind can extend to |

Ka I ga-erudebe. | That is the limit of what one can do. |

A ga-ejinwụ ya kpọ egwu oyibo. | You can use it to play non-African songs. |

E mego m ya rinne. | I have done it so many times. |

Ị je na Instagram mụ, | If you go to my Instagram page, |

I ga-afu ebe m ji ya kpọ, | You will see where I used it to play, |

Egwu Bob Dylan; | A Bob Dylan song; |

‘Blowing in the wind.’ | ‘Blowing in the wind.’ |

A ga-ejikwa ya kpọ, | It can also be used to play, |

Ma egwu ndị Igbo eji ekpe ekpere. | Even songs the Igbo use to worship in Christian churches |

Ma ihe anyị na-akpọ gospel music. | Including what we call gospel music. |

M’egwu ana agụ n’ụnọ ụka. | Indeed, songs that are performed in the churches. |

Egwu dị iche iche. | Different songs. |

E mechago m ya. | I have done all these |

M’egwu choir, a ga-ejinwụ ya. | It can also be used in choral music. |

Onye chọ kita, o tinye ụbọ na choir ya. | If a person desires, he can use the ụbọ in his choir. |

Ọ na echiche. | It is in the mind. |

O nwerọ ebe ede na anaghị etinye ya na ya. | It is not written anywhere that you cannot apply it there (the ụbọ) |

Ị che ya, si ka e tinye ya, e tinye ya, | If you think creatively about how to use it, you apply it, |

ọ daba, ọ mebe. | if it makes sense, then that is it. |

Ọ tọba ndị mmadụ ụtọ, ọ gbasa siba ebe nịịle. | When people like it, then it becomes popular. |

Appendix

Additional videos provided by Gerald Eze (the interview participant):

1. Ubọ-aka and Music Education

https://youtu.be/JeV6FOmAo5I?si=Q_u4kTQs-QaRb2kG

This is a short documentary on Ichoku Academy, showing the study of ubọ-aka and various Igbo musical instruments. This documentary also features commentaries by Dr. May-Blossom Brown, who, as cited in the interview, provided her house for the training of children on ubọ-aka music in an Igbo town, Umuoji, Idemili North Local Government Area, Anambra State. The rehearsals and performances shown in the documentary were being held at the Ichoku Academy Center and Obalende Restaurant, both in Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria.

2. Ubọ-aka in Choral Music

https://youtu.be/oBGKjndXK0w?si=2FLUtGGwctqi0_w1

Gerald Eze performing “Abuoma 6: Ukwe Ndi Nsogbu Biara” (popularly known as Yahweh Gi Ejine Iwe), a choral music composed by Rev. Fr. Raymond Arazu (PhD).

Notes drawn from the YouTube link to Gerald Eze’s channel:

Fr. Arazu played a huge role in developing indigenous Igbo liturgical music for the Catholic Church. He translated the psalms to Igbo and used the Ubo-aka to compose original tunes for the psalms. He died on 26 December, 2021. This performance was done by his graveside on the 26th of January 2022. Here is the Ubo-aka playing his Abu. Before his death, I gifted him one ubọ-aka after performing in his parish severally with the ubọ-aka. He was trying to play this particular chant with the ubọ-aka and it took him some time but he eventually got it. I played it for him with different variations and he said to me: “you are the master.” Fr. Arazu is late but his legacies live on.

3. Cultural Fusions of the ubọ-aka

https://youtu.be/8649lGvRd54?si=Zo-Bu95EQ9-LdSWA

Gerald Eze and Daniel Flori on ubọ-aka and Guitar Fusion performance of an Igbo folk song originally composed by Mike Ejeagha.

https://youtu.be/-7n-r9VSTpo?si=Aj-pKyDv1W4ij4BM

Gerald Eze and Claire Merlet on the ubọ-aka and Violin playing an Igbo Choral music of the Catholic Church, composed by Rev. Fr. Udoka Chinedu Obieri at the Art Omi music residency, New York, United States of America.

4. Ubọ-aka music played to Western popular music

https://youtu.be/WsqbbOUJCJY?si=rzNmVAIx-I3acgI4

Gerald Eze playing “Despacito” originally by Luis Fonsi, and popularized by Justin Bieber.

https://youtu.be/WHYE11Lv2g0?si=DBWgyqDfaygDIjuQ

Ubọ-aka accompaniment of Shape of You by Ed Sheeran, performed by Gerald Eze (ubọ-aka) and Benita Amaluwa (voice).

5. Ubọ-aka played to an Igbo Christian Music

https://youtu.be/3h6OKskievM?si=mrg7eUuBMEFTnzxT

Gerald Eze plays the one octave ubọ-aka to Sir. Sam Ojukwu’s Jesus Aha na-aso m Uso.

Quintina Carter-Ényì

University of Georgia

Hugh Hodgson School of Music

Athens, Georgia, United States

quintina.enyi@uga.edu

Works Cited

Berliner, Paul, and Cosmas Magaya. 2020. Mbira’s Restless Dance: An Archive of Improvisation. University of Chicago Press.

Berliner, Paul. 2019. The Art of Mbira: Musical Inheritance and Legacy. University of Chicago Press.

Carter-Ényì, Quintina. 2021. Interview with Gerald Eze. (Audiovisual recording) https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLUJsepdZhr7wfZnorSeLYC9jy8_QCypA6

Ezeani, Ifunanya P. 2021. “Revitalization of ubọ-aka Igbo Traditional Musical Instrument: The Case Study of Emmanuel Nwankwo (Onye ụbọ).” The Pedagogue: Festschrift In Honour of Professor Chukwuemeka Eleazar Mbanugo 1 (3): 360–64.

Ezegbe, Clement Chukuemeka. 1977. “Igbo ubọ-aka: Its Role and Music among the NRI people of Nigeria.” Master of Music Thesis, The University of British Columbia.

Hornbostel, Erich M. Von, and Curt Sachs. 1961. “Classification of Musical Instruments: Translated from the Original German by Anthony Baines and Klaus P. Wachsmann.” The Galpin Society Journal 14: 3–29.

Kubik, Gerhard, and Peter Cooke. 2001. “Lamellaphone.” Grove Music Online. Accessed May 3, 2024. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000040069.

Lo-Bamijoko, J. N. 1987. “Classification of Igbo Musical Instruments, Nigeria.” African Music: Journal of the International Library of African Music 6 (4): 19–41.

Moon, Jocelyn. 2018. “Karimba: The Shifting Boundaries of a Sacred Tradition.” African Music: Journal of the International Library of African Music 10 (4): 103–25.

Tracey, Andrew. 1972. “The Original African mbira?” African Music: Journal of the International Library of African Music 5 (2): 85–104.

Footnotes

* I extend my gratitude to Gerald Mmaduabuchi Eze for the generous time and effort he committed to the interview and subsequent correspondence. Jonathan Eldridge II provided the musical transcriptions of the interview. Participant support, research services and technological resources were funded by a National Endowment for the Humanities grant awarded to Morehouse College for the Africana Digital Ethnography Project, a digital collection hosted by the Atlanta University Center Woodruff Library (radar.auctr.edu/adept).

Return to text

1. All of the video clips from the session are available in a single playlist at this YouTube link, and also listed in the works cited as Carter-Ényì 2021.

Return to text

2. Solfa is the term used in Nigeria, as in “Tonic Sol-Fa” which is what the missionaries called it.

Return to text

3. In Idemmili North Local Government, Anambra State.

Return to text

4. a town in Aguata Local Government Area of Anambra State.

Return to text

5. a neighboring town to Uga.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Leah Amarosa, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3239