Translation of the section on nuclear tones from Koizumi Fumio’s “Research on Japanese Traditional Music”*

Liam Hynes-Tawa

KEYWORDS: nuclear tones, tetrachords, tonality, tonic, ethnomusicology, Koizumi Fumio

ABSTRACT: This article presents an English translation of most of a section from Koizumi Fumio’s influential Research on Japanese Traditional Music 日本傳統音楽の研究 (Ongaku no Tomo Sha, 1958). The section appearing below is the one in which he introduces the concept of “nuclear tones,” which have the gravitational properties of a tonic, but differ importantly in that they come in pairs, not requiring one member of the pair to dominate the other, and in that they neither presume nor encourage an octave- or scale-based way of construing pitch material. Nuclear tones are a necessity for understanding Koizumi’s conception of the tetrachord, which remains important in Japanese music analysis to this day. To illustrate his points, Koizumi calls on a diverse range of examples, ranging across many different regions and styles of Japanese music, demonstrating how despite these differences, the nuclear tone remains a vital and useful concept for understanding nearly all of them—and how, in the rare cases when it does not seem relevant, that is a sign about the music’s probable origins.

Though Koizumi’s project in this particular book was Japanese music, he was interested in a wide variety of musics across the world, and theoretical tools of his like the nuclear tone and tetrachord were meant to be similarly widely applicable. I hope that by making this work more visible to the English-speaking world, it may help Koizumi’s ideas to reach audiences he had always wanted them to.

PEER REVIEWER: Tomoko Deguchi

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.9

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction (Liam Hynes-Tawa)

[0.1] Here follows a translation of most of chapter 3, section 3 from Koizumi Fumio’s(1) Research on Japanese Traditional Music ([1958] 1977). This section is an important one because it is the one in which Koizumi introduces his most pivotal notion: the nuclear tone. Koizumi’s nuclear tones act in pairs, both exerting gravitational force on the music at the same time, allowing for multipolar senses of pitch-centricity. This idea is fundamental to the idea of the tetrachord, for which he is perhaps most famous, and which follows not long afterward in the book. In this section, he presents Japanese music from a variety of genres, times, and regions to demonstrate how nuclear tones act differently in them, while remaining a meaningful attribute in all of them.

[0.2] Koizumi was working in an environment in which resources were limited and difficult to come by. Given how poor Japan still was in this time directly after the end of the Second World War, it is remarkable that Koizumi was able to gather as much music as he did. The transcriptions, as we can see from the various credits given to them, come from quite a diverse array of sources even within this small section, and the fact that he could make something so coherent and lasting out of them would not be a small feat even today. Owing mostly to the state of the resources he was working with, it is inevitable that some of his examples and analytical choices may strike today’s readers as odd in some way or other, which I will address in footnotes as they occur—but they do not detract from the enduring value of the basic premise, and serve only to highlight how eclectic his pool of resources was.

[0.3] This excerpt unfortunately does not have the space to include a full introduction of the notion of the tetrachord as Koizumi uses it, but what is most important to remember is that the system he is developing here resists and refuses the notion of the octave-bounded scale. A great many Japanese melodies have a narrow ambitus of only a fourth or a fifth, and much of Koizumi’s work is based on the sense that an octave-framed scale is inaccurate to the realities of the music in question—specifically, he sees the perfect fourth as the most meaningful structural frame, and constructs a system that is based on fourths rather than on octaves, and which also allows for steps larger than a whole step without the sense that any note has been “skipped.” The notion of the nuclear tone accomplishes two relevant, foundational goals at once, both establishing the boundaries of this structural fourth and doing away with the notion of a unitary tonic in favor of a pair of equal poles.

[0.4] A brief half-paragraph from early on in the section has been omitted because its discussion of the specificities of nō performance and its difficulties for transcription did not seem to add much within the limited context available to this excerpt.

Translation of Koizumi

Nuclear tone, Kernton

Example 1. Koizumi’s example 25A

(click to enlarge)

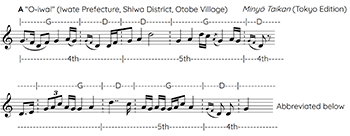

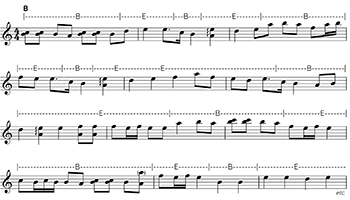

[1.1] The observations in the previous section on ending notes indicate two new directions to explore. One is the meaning of ending notes themselves within melodies, while the other is the interval of the perfect fourth that is based around these two ending notes. For both of these, the differences between Japanese musical rules and those of Europe are of course the elements make Asian music seem so extremely peculiar. But here, let’s first think about the former. Example 25A (Example 1) takes an arbitrarily-chosen example of a folk song, and above the notation divides the various musical phrases into those controlled by the ending note G and those controlled by D. Below it, it divides the phrases bounded by the interval of a fourth from those bounded by a fifth.

Example 2. Koizumi’s example 25B

(click to enlarge)

[1.2] In this example, I have omitted the bar lines,(2) but the vertical lines based on the analyses above and below the notation, to a certain point, agree with where the bar lines would be. Although these will become the biggest divisions when making comparative observations about melodies, let’s for now put this problem aside. For now, in A, I have made narrower divisions in the upper analysis than in the lower, but the relation between the two is certainly hard to determine as a rule. On the other hand, for the part of the melody controlled by one of the ending notes, the other ending note does not function as the ending note but simply appears in passing. Also, fourths and fifths may not purely limit the range of notes, and extra notes might be added above or below. I have brought out example B (Example 2) in order to make this relationship clearer. This bon-odori(3) song from beginning to end is under the control of the interval of a fourth between

[1.3] Although I have narrowly divided the melody into phrases controlled by

Example 3. Koizumi’s example 26

(click to enlarge)

[2.1] In cases like these, the ending note on the one hand holds meaning not only as a simple ending note to the piece, but also holds meaning as a central nucleus of upward and downward movement in the melodic line. On the other hand, among songs like “Counting Song” and “Net-Pulling Song” whose melodies tend to be repeated continuously, there are many songs with melodies that certainly do not end on the ending note (even in those cases, the ending notes do not lose the meaning of a central nucleus of the melodic line). For that reason, rather than calling them ending notes, it may be more appropriate to call them central nuclear tones or simply nuclear tones. These nuclear tones appear extremely clearly in Japanese art music, especially in the utai of nō(4) music and shamisen vocal music like nagauta,(5) even more than in folk songs. The melodies in those (art music) cases have the characteristic of revolving around only one nuclear tone, and bobbing up and down around it. For example, in the nagauta “Oimatsu (Old Pine),” if we take honchōshi(6) on the third string (in which it matches the first string of the shamisen, which is tuned to B), it will be transcribed as in example 26 (Example 3).

[2.2] In this case, the nuclear tones would be E (for 10 measures) – B (2) – E (3) – B (5) – E (2) – B (4) – E (3) – B (2) – modulation,(7)

[

[3] I will discuss the meanings of nuclear tones in comparative musicology in section 4, but in Western music, we do not generally see things like this. Therefore, in European music theory terminology, there is no word that appropriately expresses this. In biology, the nucleus is the central part in the middle of the cell that has the shape of a ball or a string. Normally there are one or two nuclei in a cell. All of the protoplasm is around the nucleus, and when a cell divides, this nucleus’s division is the first thing it carries out. What it means to be a melody’s nuclear tone also comes from this. When we see that the notes around a nuclear tone do not easily leap from the nuclear tone, we can hypothesize that their nature is subordinate to the nuclear tone. In other words, we can also say that the nuclear tone controls the notes around it. It is also often the case that it puts another nuclear tone under its control. In the cases of

[4] Also, I learned after having written my thesis that Mr. Itō Ryūta has used the word “central tone” with almost the same meaning as nuclear tone.(9) It is understood that Mr. Itō applied the word “central tone” as something commonly used in Japanese traditional music, in the same way European music used it in a free pitch language(10) after it gradually began to pull away from its original major- and minor-key organization of tonal music. The more recent usage of this word is most appropriate for analyzing the melodic construction of Japanese traditional music, especially the music of the recent past in the Edo period [1603–1867 CE]. Therefore, the nuclear tone that I speak of points to exactly the same thing as this central tone in the Japanese music of the recent past that has a well-established pitch organization. However, the materials that I intend to handle are not simply art musics that are already established, but also include folk musics in which the tonic pitch is less clear. Also, to take that point further, starting with the Ryukyus, Korea, and China (which pose some difficulty), I want to apply this concept to a generalized organization of notes in Asian music, and explain them afterward in detail, analyzing their melodies using the unit of the tetrachord,(11) which spans the interval of a fourth. In such cases, two or three of these nuclear tones can appear within an octave as “important notes that make a melodic frame.” For that reason, the word “central tone” has a somewhat one-dimensional ring to it, and I think its meaning is too narrow. Therefore, it includes the concept of a central tone, but in some situations I will use the word “nuclear tone” with a broader meaning than it has had up till now.

[5.1] Now then, how does the control over melodies that nuclear tones have manifest in various different genres of traditional music? We cannot know anything for certain about music before the importation of gagaku, and even that old original music that does remain in the present has probably undergone some change as eras have passed. Thus in opposition to the usual order of music history, I have decided to begin my investigation from what exists close at hand.

Example 4. Koizumi’s example 27

(click to enlarge)

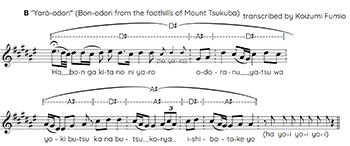

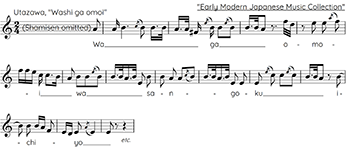

[5.2] First, our points of departure were children’s songs and folk songs. As I have said above about nagauta, nuclear tones strikingly control the melodies, but example 27 (Example 4) is an example of utazawa,(12) and the pitches B and E clearly make up the skeleton of the melody’s construction as its nuclear tones.

Example 5. Koizumi’s example 28A

(click to enlarge)

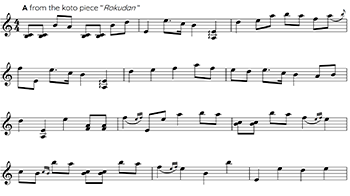

[6.1] Without even bringing up examples one by one, among recent Japanese music, vocal music accompanied by the shamisen generally does not differ much from this example. It is not at all rare in these genres, whether song or jōruri,(13) for the control of a single nuclear tone to cross a few measures much more clearly than in folk song. In instrumental music such as pieces for the koto or shakuhachi, we can see extraordinary freedom of melodic leaps, and so one may think that they have broken away from the control of their nuclear tones. For example, in example 28A (Example 5), leaps appear that are almost never seen in vocal music, like sevenths, octaves, ninths, and in the last measure even a twelfth.

Example 6. Koizumi’s example 28B

(click to enlarge)

[6.2] However, this melody is not essentially different from vocal melodies that make most of their material from conjunct motion. It is simply that leaps can be made more easily with instruments than when one has to tighten or loosen one’s vocal cords. Moving one part of the melody an octave away has no result other than to attain a richer sense of movement. As evidence for that, when we rewrite the notes an octave higher or lower, as in [example 28]B (Example 6), a melody with mostly stepwise motion, which is not at all different from those in vocal music, emerges.

Example 7. Koizumi’s example 29

(click to enlarge)

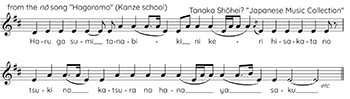

[7.1] That vocal melodies generally incline towards stepwise motion, and that instrumental melodies conversely include more leaping motion, is something that we can generally say about different types of music all around the world. But in the case of Japanese Sankyoku (music for the koto, shamisen, shakuhachi, and so on—gagaku essentially differs from this), we can safely say that even the instrumental melodies hold essentially the same type of fundamental construction as is in vocal music. In other words, as is clear from this example [28]B, the control of the nuclear tones E and B is also applicable in this case. Music from after the Edo period [1603–1867 CE] generally has influence from instrumental music (especially that of the shamisen, koto, or shakuhachi), and so even the vocal music has comparatively precise pitches, so one can determine the nuclear tones on its sheet music. However, in the sheet music of nō, which became prosperous in the Kamakura [1185–1333 CE] and Muromachi [1336–1573 CE] periods, the notes are extremely imprecise, and it is difficult to capture absolute pitch from what is displayed in the sheet music. Example 29 (Example 7), which I’ll bring up next, was transcribed by the scholar Tanaka Shōhei after he had thought thoroughly about these points.

[7.2] This is one part of something that might be called the kuse, and within the up-and-down motion across the interval of a fourth, we can clearly perceive the control of nuclear tones. In another part of the kuse, whose method of vocalization is called melodic yowagin, it is in a far more syllabic style (one word to one note) even than this. More than all the genres I have discussed so far, the control of the nuclear tones regulates the melody even more. In most places, only nuclear tones that make up the interval of a fourth with each other are the chief notes of the scale. Restrained melodic expression brings subtle changes of pitch to these nuclear tones. This sort of microtonal change in pitch is imagined to have been a technique of expressive principles that, from the beginning, had changed along with movement through the ages.

Example 8. Koizumi’s example 30

(click to enlarge)

Example 9. Koizumi’s example 31

(click to enlarge)

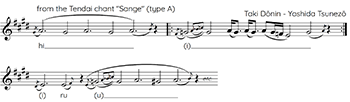

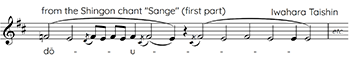

[8.1] In Buddhist chant, which is thought to be the original musical source of nō, these fluctuations in pitch did not happen so much. Thus conversely, the control of the nuclear tones in the melody are easily observed. Examples 30 and 31 (Examples 8 and 9) are examples of Tendai and Shingon chant respectively, but microtonal fluctuation is little in both, and both have simple melodies.(14)

[8.2] Looking historically, we cannot yet be as detailed as to the extent to which it is generally said that Buddhist chant had a definite influence on later Japanese music. But here we can see the most thorough control that the nuclear tones have in the melody. In Buddhist chant, there is already not much melody-like movement, and all that is there is some up-and-down fluctuation circling around one note. If this is indeed the original idea of the nuclear tone, and we have lost all clues about music before it, then we have to place the source of melodic construction controlled by nuclear tones here. However, the truth is more complicated. On the one hand, from the perspective of comparative-musicological investigations that I will discuss in the next section; and also on the other hand from the fact that the function of nuclear tones is clearly recognized even in the melodies of kagura(15) song and uta-hikō,(16) which hold origins from before the importation of gagaku and furthermore are thought to retain a trace of these functioning nuclear tones in the present; we cannot go so far as to say that this is a tendency that seeks its origins only in vocal music. These precise judgments can be allowed only from the results of intricate historical research and ethnological research. Buddhist chant is a type of music that was imported from India and passed through China, which originally came in the Nara period [710–794 CE] and then generally in the Heian period [794–1185 CE]. But gagaku, which was imported separately from China, Korea, and Manchuria, is imagined to have been transmitted to the present in a comparatively accurate form. Of all the types of traditional music, gagaku had the weakest connection to the common people, but musically it holds a special form. All aspects such as rhythm, melodic system, polyphony, and instrumental organization differ from other genres.

Example 10. Koizumi’s example 32

(click to enlarge)

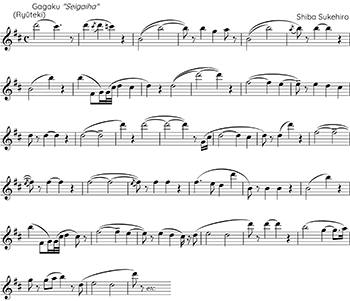

[9.1] Example 32 (Example 10) extracts only the ryūteki(17) melody from “Seigaiha,” a gagaku piece that is especially famous among the older ones.

[9.2] Because this melody is for a flute, the intervallic leaps are extreme, but as in the case with koto music, if you think of octaves as equivalent, its movement becomes surprisingly conjunct. And because this piece’s tonic was originally banshikichō (B), it is natural that the pitch B would hold an important meaning, but the pitch D also seems to have been given a sense of importance. And

[10] In sum, the function of a nuclear tone, excluding special cases, is the greatest foundational element at work in all of our traditional music. Furthermore, with this melodic construction based on nuclear tones we can reliably consider this as one aspect of “Japaneseness in music.” But because of this sort of Japaneseness, there is a need to know about musics of other ethnic groups outside of Japan, so let us next look at these nuclear tones in the manner of comparative musicology.

Liam Hynes-Tawa

Harvard University

Department of Music

Cambridge, Massachussetts

United States of America

lhynestawa@fas.harvard.edu

Works Cited

Hynes-Tawa, Liam. 2021. “Tonic, Final, Kyū: Tonal Mappings in the Meiji Period and Beyond.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 9 (1): 1–54. Accessed June 29, 2024. https://iftawm.org/journal/oldsite/articles/2021a/Hynes-Tawa_AAWM_Vol_9_1.pdf.

Koizumi Fumio 小泉文夫. (1958) 1977. Nihon dentō ongaku no kenkyū 日本傳統音楽の研究 [Research on Japanese Traditional Music], 10th printing. Ongaku no Tomo Sha.

Siddons, James. 1986–87. “Fumio Koizumi of Japan: An Asian’s Use of Concepts of Melody Found in the Works of Curt Sachs, Abraham Z. Idelsohn, and Robert Lachmann.” Musica Judaica 9 (1): 35–46.

Uehara Rokushirō 上原六四郎. 1895. Zokugaku senritsu kō 俗楽旋律考 [Thinking about the Melodies of Common Music]. Iwanami Shoten. Accessible online at https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/856052/1/1.

Footnotes

* I am very thankful to Tomoko Deguchi for her consistently excellent help with preparing this translation, and thinking with me about how to render so many complex concepts and ideas in English. This translation would have been much less accurate and clear if not for her input.

Return to text

1. In this publication I will be rendering all East Asian names in East Asian order, i.e., surname before given name. All footnotes are my editorial and explanatory additions, aside from one that comes from Koizumi’s original—Koizumi’s footnote will be preceded by “[KF].”

Return to text

2. When Koizumi refers to “omitting the bar lines,” he is probably referring to those in the Min’yō Taikan collection’s transcription from which he has extracted the song—before it was transcribed for that collection, it probably did not exist in a form with written bar lines.

Return to text

3. Bon-odori 盆踊り refers to a dance (odori) for the o-bon festival, one held in (usually) July or August, at which ancestral spirits are venerated. It is cognate with the Chinese Zhongyuan or Hungry Ghost Festival, and to the Korean Baekjung.

Return to text

4. Utai 謡, while etymologically meaning simply “song,” has come to refer specifically to the vocal music of the nō 能 theater tradition. It is accompanied by a hayashi 囃子 ensemble, which consists of a few drums and a flute.

Return to text

5. Nagauta 長唄, literally “long song,” is a song genre from the kabuki 歌舞伎 theater tradition, accompanied by shamisen and also often by a hayashi ensemble.

Return to text

6. Honchōshi 本調子 is the most basic shamisen tuning, which puts the strings at roughly B-E-B.

Return to text

7. The marking of this “modulation” may raise a few questions—clearly it is for the sake of accommodating the new status of

Return to text

8. In other words,

Return to text

9. [KF]: Itō Ryūta 伊藤隆太; analysis of koto pieces, “Gakudō 楽道 (The Road to Music),” Shōwa 30 [1955 CE], October edition.

Return to text

10. Literally 自由な音語, this is likely a translation of the German freitonal, and refers to the twentieth-century trends in Western classical music often called atonal or post-tonal in English.

Return to text

11. The tetrachord ends up being one of Koizumi’s most far-reaching conceptions—though understanding how his tetrachords work relies on understanding nuclear tones, hence this publication’s focus. A tetrachord, in Koizumi’s conception, consists of two nuclear tones a fourth apart and one movable tone between them. This means that, confusingly, his tetrachords feature only three notes—they gain their name from the interval of a fourth outlined by the nuclear tones. The name “tetrachord” also points to the concept’s inheritance from the early-twentieth century ethnomusicologist Robert Lachmann’s work on a wide variety of musics, and ultimately from ancient Greek music theory. For more, see Siddons 1986–87.

Return to text

12. Utazawa 歌沢 is a late-Edo-period song genre derived from the earlier hauta 端唄 genre. Both are genres of song accompanied by shamisen, the differences inhering mostly in performance style and affective subtleties.

Return to text

13. Jōruri 浄瑠璃 is another genre of shamisen-accompanied vocal music. It leans more towards narration than towards song, and is often used to accompany puppet theater genres like bunraku 文楽—this emphasis on narration is why Koizumi contrasts it with “song” (uta 唄).

Return to text

14. It is not at all clear to me what the key signatures in examples 30 and 31 are supposed to mean—the notes sharpened by the signatures are canceled out far more often than they are followed. It may have something to do with a wider context that these excerpts are not able to show, but in any case, this notational oddity may be taken as one sign of the limited resources with which Koizumi was working.

Return to text

15. Kagura 神楽 is music and dance connected to Shinto ritual, which has close ties to and overlaps with gagaku.

Return to text

16. Uta-hikō 歌披講 is unaccompanied melodic recitation of Japanese poetry, which survives in the utakai hajime 歌会始め event, where new poems are presented to and by the imperial family on New Year’s Day. Uta-hikō is, however, thought to have started in the Heian period, and so Koizumi may not be correct to place it before the importation of gagaku. On the other hand, it still may well preserve an older singing style, or at least be descended from one.

Return to text

17. The ryūteki 龍笛 is a wooden transverse flute used in gagaku.

Return to text

18. The ryo 呂 scale is primarily a major pentatonic scale, which is also sometimes extended to a Lydian or Mixolydian diatonic scale. Its opposite within the gagaku modal system is ritsu 律, whose pentatonic form has a perfect fourth rather than a major third above the tonic, and whose diatonic form is Dorian.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Lauren Irschick, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4609