Translation of Shin Eun-Joo’s “Two Theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo in Pansori: Comparing Baek Daewoong’s and Lee Bohyeong’s Theories of Pansori Modes” (2018)*

Seokyoung Kim

KEYWORDS: Mode theory, Traditional Korean Music, Pansori, Sanjo, Ujo, Pyeongjo

ABSTRACT: This article presents a translation of Shin Eun-Joo’s “Two Theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo in Pansori: Comparing Baek Daewoong’s and Lee Bohyeong’s Theories of Pansori Modes,” an article published in Studies in Korean Music in 2018. Pansori and sanjo are small-ensemble genres of Korean folk music with many shared characteristics, such as modes, rhythmic patterns, and decorative notes. Shin offers a critical examination of modal theories in traditional Korean music by juxtaposing the analytical frameworks proposed by Baek Daewoong (1974–2011) and Lee Bohyeong (1937–2024), particularly focusing on the Ujo 우조 and Pyeongjo 평조 modes in pansori. The complexity of pansori modal theory is largely due to two features of the jo 조 (mode), particularly Ujo and Pyeongjo, in Korean folk music. First, a jo is not merely a collection of notes but involves a certain effect produced by each; for instance, Ujo is often described as “majestic” and “benevolent,” while Pyeongjo is less so. Second, certain notes of a given jo frequently incorporate ornamentations such as vibrato, glissando, and slides, which play a crucial role in constructing the mood of the jo. It is, therefore, difficult to distill the notes of a jo into a limited cardinality without an analyst’s input. For these reasons, scholarly discussions of the two melodic modes have not reached a consensus. In this context, Shin’s study is significant for emphasizing the embellishments and seongeum 성음 (vocal timbre) that enhance emotional expression (regarding Lee’s theory) beyond the constituent notes (regarding Baek’s theory) when constructing modal theories of pansori, which are then applied to sanjo.

PEER REVIEWER: Joon Park

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.10

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Notes on the Translation

[0.1] Pansori 판소리 and sanjo 산조 are small-ensemble genres of Korean folk music with many shared characteristics.(1) Pansori consists of a dramatic narrative performance by a sorikkun 소리꾼, a vocalist-narrator, and a gosu 고수, a drummer who provides rhythmic accompaniment on a barrel drum called a puk 북. During the pansori performance, a sorikkun narrates the story based on historical events or folk tales while incorporating song, speech, and gesture, all of which have been transmitted orally over several centuries. Requiring the highest levels of creativity and expertise, only five stories—based on folk tales—are in the current repertory; each is several hours long and allows for individual interpretation and development (Provine, Hwang, and Howard 2001).(2) Partly derived from pansori, sanjo was originally an improvised solo instrumental form accompanied by a drum, usually a janggu 장구; today, sanjo presents a fully predetermined melody, omitting improvisation. Sanjo may be played with a variety of traditional Korean string or wind instruments, including gayageum 가야금 (twelve-string zither), geomungo 거문고 (six-string zither), ajaeng 아쟁 (bowed zither), and daegeum 대금 (bamboo flute). It presents four or more rhythmic patterns 장단 (jangdan) in “ascending orders of metrical speed” (Provine, Hwang, and Howard 2001)—from slow tempo (e.g., jinyang 진양) to fast rhythmic cycles (e.g., hwimori 휘모리)—demonstrating the performer’s technical proficiency and expressive abilities.(3)

[0.2] Korean music theorist Shin Eun-Joo offers a critical examination of modal theories in traditional Korean music by juxtaposing the analytical frameworks of Baek Daewoong (1974–2011) and Lee Bohyeong (1937–2024), particularly focusing on the Ujo 우조 and Pyeongjo 평조 modes in pansori (Shin 2018).(4) Ujo and Pyeongjo are two jos 조 (modes) commonly used in pansori. The complexity of pansori modal theory is largely due to two features of the jo, particularly Ujo and Pyeongjo, in Korean folk music. First, a jo is not merely a collection of notes but involves a certain effect produced by each; for instance, Ujo is often described as “majestic” and “benevolent,” while Pyeongjo is less so. Second, certain notes of a given jo frequently incorporate ornamentations, such as vibrato, glissando, and slide, which play a crucial role in constructing the mood of the jo. It is, therefore, difficult to distill the notes of a jo into a limited cardinality without an analyst’s input.(5) This difficulty is compounded by the fluid nature of the two modes, which frequently intertwine and transition seamlessly. For these reasons, there is no scholarly consensus on the two melodic modes, not because of their inherent distinctiveness, but due to their interconnected and overlapping usage. A typical example of this is the conflicting and overlapping definitions provided by gugak (the national music of Korea) scholars of the modes: Ujo is described as a pentatonic scale comprised of a-c-d-e-g with little vibrato or glissando (Lee and Lee 2007, 134);(6) Pyeongjo is defined as a pentatonic scale of g-a-c-d-f but with vibrato or ornamentation causing the f to fall to or be pitched closer to e (Lee and Lee 2007, 134).(7)

[0.3] Due to these issues, introductory texts for Korean traditional music provide vague definitions for the two modes,(8) recognizing that the constituent notes are insufficient in determining the mode. In this context, Shin’s study is significant for emphasizing the embellishments and seongeum 성음 (vocal timbre) that enhance emotional expression (regarding Lee’s theory) beyond the constituent notes (regarding Baek’s theory) when constructing modal theories of pansori, which are then applied to sanjo.

[0.4] This translation presented unique challenges, particularly regarding the original author’s use of Western musical concepts such as letter names, solfège, staff notation, and the concepts of key (joseong 조성), half cadence (ban-jongji 반종지), and cadence (jongji 종지). These concepts, while familiar to practitioners of Western music theory, may seem out of place in the context of traditional Korean music. However, it is common practice among current music theorists of traditional Korean music to adopt these Western terms and interact with Western music scholarship.(9) Scholarly borrowing of these concepts is for convenience and does not imply a broader Western harmonic context, because it is difficult to say that traditional Korean music is tonal music.(10) Additionally, several specific Korean musical terms, particularly embellishments, pose difficulties in translation. To preserve the cultural and musical essence they embody, I will use the original terms without literal translation. For this reason, I encourage my readers to familiarize themselves with the terms given below before reading the translation.

- Sigimsae 시김새 refers to the sophisticated vocal techniques and idiomatically stylized ornaments, which serve as the initial prerequisites for singing, from which the emergence of creative expression with nuanced shading arises (Lee and Lee 2007, 121).

- Yoseong 요성 and toeseong 퇴성 are subcategories of sigimsae. Yoseong denotes a vibrating or wavering sound, comparable to the Western musical technique of vibrato but executed in a uniquely Korean style. Toeseong denotes a technique wherein the pitch descends towards the end of a note, thereby enhancing the expressiveness of the performance.

[0.5] In the translation, the modal categories (e.g., Ujo, Pyeongjo, and Gyemyeonjo) are capitalized to help readers distinguish between these and other Korean terms used, including rhythmic patterns (e.g., jinyangjo, jajinmori, and jungmori), musical genres (e.g., pansori and sanjo), ornamentations (e.g., yoseong and toeseong), and instrument names (e.g., gayageum and daegeum). Furthermore, I use various parentheses to separate my remarks from those in the original text: square brackets denote my explanatory remarks and additional context; curved parentheses are used for notes that appear in the original text. This is done to promote clarity and avoid confusion between the original author’s comments and my explanations. All the footnotes in this translation are credited to the original author, except for those in square brackets.

Translation: Shin Eun-Joo, “Two Theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo in Pansori: Comparing Baek Daewoong’s and Lee Bohyeong’s Theories of Pansori Modes (2018)

[0.6] Although Korean musicologists have long debated the melodic modes in pansori, there is a lack of consensus regarding the identification of the pansori modes, which they have attempted to define based on different modal theories. The theories of Baek Daewoong (1974–2011) and Lee Bohyeong (1937–2024) are the representative views of pansori scales. While Baek and Lee concur on the criteria for Gyemyeonjo, they diverge on the modes for Ujo and Pyeongjo. As a result, the same theatrical scenes performed by the same vocalists have been variously described—as either Ujo or Pyeongjo—depending on which theory has been applied in analysis. Additionally, an endeavor for consensus on modal theory in pansori is dearly needed because an individual instructor's academic background completely determines which modal theory to put at the forefront of their lectures.

[0.7] This paper cross-examines Baek’s and Lee’s modal theories, the two most widely adopted theories in academia for analyzing pansori’s mode, by observing different perspectives on Ujo and Pyeongjo’s characteristics while focusing on their theories’ similarities and differences. In addition, this study correlates pansori with sanjo to gain a deeper understanding of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori, as they share the same musical features [due to their common historical association with shamanic rituals in the southern region of Korea].

1. Redefinition of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori

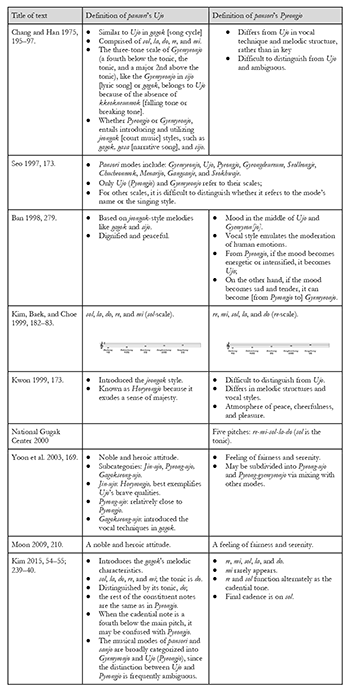

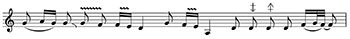

Example 1-1. Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori in introductory texts to traditional Korean music

(click to enlarge)

[1.1] Until recently, introductory texts for traditional Korean music have ambiguously defined pansori modes.

[1.2] Chang and Han 1975 claim that pansori’s Ujo incorporates jeongak styles, similar to gagok’s Ujo or the three-note scale, Gyemyeonjo. They specify that pansori’s Pyeongjo is distinguished from Ujo by its vocal style and melodic structure, rather than tonality. Other introductory texts give similar explanations; most characterize Pyeongjo as displaying “fairness and serenity” and Ujo as “noble and heroic” and “dignified and peaceful” (Chang and Han 1975, 195–97). The distinction between Pyeongjo and Ujo in pansori is, however, unclear, as Pyeongjo is described as “an intermediate character between Ujo and Gyemyeonjo” or “difficult to distinguish from Ujo” (Chang and Han 1975, 195–97).

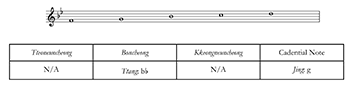

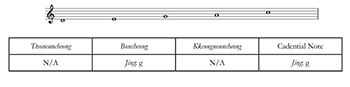

[1.3] Only two publications—Kim, Baek, and Choe 1999 and Kim 2015—provide scale degrees and tonics of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori. Baek’s pansori modal theory is presented in Kim, Baek, and Choe 1999, which he co-authored. According to Kim 2015, the note set of Ujo in pansori consists of sol, la, do, re, and mi, while that of Pyeongjo is comprised of re, mi, sol, la, and do. This connects to Baek’s theory, although Kim believes that Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori consist of the same notes, differing only in the tonic (the cadential note), that “The tonic [of Ujo] is the only distinction; the rest of the notes are the same as in Pyeongjo” (Kim 2015). Alternatively, “when the cadential note is a fourth below the tonic, it is challenging to discern from Pyeongjo” (Kim 2015).

[1.4] In addition to discrepancies in the introductory literature on gugak regarding the descriptions of Ujo and Pyeongjo, the majority of texts fail to define pansori modes with conceptual clarity. If Pyeongjo is said to offer “peace, cheerfulness, and pleasure” (Kwon 1999, 173) and “fairness and serenity” (Yoon et al. 2003, 169; Moon 2009, 210) and Ujo conveys a sense of “noble and heroic” (Yoon et al. 2003, 169; Moon 2009, 210), there must be a clear explanation of the fundamental musical qualities—sets of notes, the features of each pitch—that create these emotional expressions. Furthermore, they discuss how difficult it is to delineate Ujo from Pyeongjo as the boundary between the two is ambiguous, or they describe Pyeongjo as a sensation in between Ujo and Gyemyeonjo, or, rather than a difference in tonality, it is a difference in the styles of vocal technique and the melodic structure.

[1.5] The introductory texts demonstrate the absence of agreement on modal theory in pansori within academia. The text describing Baek’s pansori theory was published in 1982. Since then, extensive work has been done on transcription utilizing staff notation and analysis of pansori. The history of research on pansori has accumulated over more than thirty years, but it is still necessary to bring order to the disorganized Ujo and Pyeongjo concepts. As a starting point, this paper compares and reviews Baek’s and Lee’s respective theories on Ujo and Pyeongjo. By recognizing the similarities between the characteristics of each theorist’s understanding of Ujo and Pyeongjo and highlighting the issues with their disparities, a common ground may be found for these viewpoints.

2. Comparing modal theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo between Baek and Lee

[2.1] Baek’s and Lee’s pansori modal theories ostensibly appear distinct, but comparison of their in-depth descriptions of the functions and traits of each note reveals correlation. In this section, I will examine the traits of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori offered by each scholar.

2.1. Baek’s theory of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori

[2.2] Baek 1982 describes his modal theory of pansori in “Chapter 1: Ujo, Pyeongjo, and Gyemyeonjo in pansori.”(11) This was later reprinted in Baek 1996.

1) Baek’s Ujo in pansori

Example 2-1. Baek’s Ujo-gil in pansori

(click to enlarge)

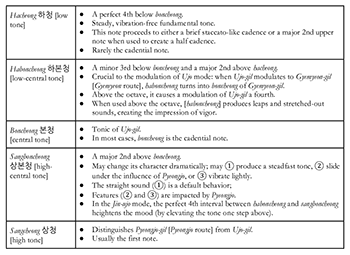

Example 2-2. Baek’s functions and characteristics of Ujo-gil tones

(click to enlarge)

[2.3] Baek introduces Ujo in pansori (Example 2.1) and thoroughly discusses each tone’s function (Example 2.2).

[2.4] When examining the qualities of each note in Ujo-gil [Ujo route] as Baek describes them, it is crucial to focus on the characteristics of sangcheong.(12) Baek claims that sangcheong “distinguishes Pyeongjo-gil from Ujo-gil” and that “it is crucial that the interval between boncheong and sangcheong is a major 3rd (a perfect 4th in the case of Pyeongjo-gil)” (Baek 1982, 1995, 1996). Therefore, if the gap between boncheong and sangcheong is a major 3rd, it is analyzed as Ujo according to Baek’s theory. If the interval between the two notes is a perfect 4th, it is Pyeongjo. In other words, a major 2nd between sangboncheong and sangcheong is Ujo, and a minor 3rd is Pyeongjo.

[2.5] Baek’s theory defines Ujo in pansori only as “the sets of five notes: sol, la, do, re, and mi” (Baek 1982, 1995, 1996) because the criteria for differentiating between the modes relies heavily on sangcheong and does not make extensive use of the qualities of each note. Nonetheless, Baek goes into great detail about the specific functions and characteristics of each tone in Ujo-gil.

[2.6] In Ujo, hacheong is the note of a half cadence, without the capacity for vibration. It plays a significant role in transposition and modulation and, when used above the octave, contributes to the distinctive and energizing quality of Ujo.(13) As shown in Example 2.2, sangboncheong has three qualities, which vary considerably. Sangboncheong in Ujo has a default behavior of producing a steadfast tone; in Pyeongjo, it influences the sliding or vibrating sound, which does not occur in Ujo. Pyeongjo and Ujo are used in conjunction with one another due to Pyeongjo’s impact on sangboncheong in Ujo.

[2.7] Furthermore, Baek assigns three subcategories to Ujo: Jin-Ujo, Pyeong-Ujo, and Gagokseong-Ujo. Jin-Ujo best expresses the nature of Ujo; in particular, the fourth interval (la-re) between haboncheong and sangboncheong heightens the atmosphere with the impact of raising one step the tonic [cheong]. That is, Jin-Ujo raises the melodic structure [between the two notes] by one step as it progresses.

[2.8] The five notes comprising Baek’s Ujo-gil in pansori are sol, la, do, re, and mi, with do serving as the mode’s tonic [boncheong]. The interval between boncheong and sangcheong, that is, the relative pitch of sangcheong, is the determining factor in distinguishing Ujo-gil from Pyeongjo-gil. Nevertheless, it should not be overlooked that he defines the functions and characteristics of the five notes and the intervals between them, even though they are not at all used to denote the modes.

2) Baek’s Pyeongjo in pansori

Example 2-3. Baek’s Pyeongjo-gil in Pansori

(click to enlarge)

Example 2-4. Baek’s functions and characteristics of Pyeongjo-gil tones

(click to enlarge)

[2.9] Baek introduces Pyeongjo in pansori and thoroughly explains each note’s function as follows.(14)

[2.10] Baek distinguishes between the re, mi, sol, la, and do of Pyeongjo-gil and the sol, la, do, re, and mi of Ujo-gil. In his description of the functions and features of each pitch, Baek claims that sangcheong [in Pyeongjo] “is a different note from the one in Ujo on the staff, and is a half step (minor 2nd) higher than sangcheong in Ujo” (Baek 1982, 1995, 1996). The interval between sangcheong and sangboncheong, or the pitch of sangcheong, therefore determines how Pyeongjo-gil and Ujo-gil are distinguished from one another.

[2.11] Baek concentrates on the functions and characteristics of each pitch in Pyeongjo-gil. The fourth interval between hacheong and boncheong is common, with hacheong often being the cadential note. Although Baek does not emphasize this point, it is implicit that hacheong in Pyeongjo vibrates more than that in Ujo.(15) Furthermore, haboncheong in Pyeongjo-gil serves a very minor function and appears rarely, so its removal has little effect on the determination of Pyeongjo-gil. This is in contrast to haboncheong in Ujo, which is crucial to modulation and transposition. In Pyeongjo-gil, boncheong frequently appears in fourths sequences with hacheong and seconds sequences with sangboncheong; the cadential note in these cases is hacheong, but the sequences sometimes conclude with boncheong. The most recognizable note in Pyeongjo, sangboncheong, is employed in a variety of ways, similarly to Ujo. Sangboncheong in Pyeongjo “flows down, trembles softly, and has decorative notes like daru in Gyemyeon-gil;” in Ujo-gil, sangboncheong “has a firm timbre” (Baek 1996). Baek explains that sangcheong in Pyeongjo is distinct from and a half step (minor 2nd) higher than that in Ujo. Nonetheless, Baek emphasizes the flexibility of sangcheong’s pitch: “the pitch is unstable; thus some people sing it a semitone lower” (Baek 1996). These descriptions of sangcheong go against the fundamental tenet of Baek’s theory, which says that the pitch of sangcheong (i.e., the interval between boncheong and sangcheong) is what separates Ujo from Pyeongjo.

[2.12] In summary, Baek’s theory outlines the constitutive tones of Ujo-gil and Pyeongjo-gil and thoroughly describes the features and functions of each note. The interval between boncheong and sangcheong is the criterion for separating the two modes; nevertheless, the pitch of sangcheong is what distinguishes Ujo-gil from Pyeongjo-gil. Consequently, the features and functions of each note have no bearing on how the mode is determined in Baek’s theory.

2.2. Lee’s theory of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori

[2.13] Lee 1998 summarizes pansori mode names’ history, such as Ujo, Pyeongjo, and Gyemyeonjo, and briefly organizes these concepts.(16) He presents a thorough conceptualization about Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori, including the constituent notes, sigimsae, melodic structures, and functions of each tone, in Lee 2002.

1) Lee’s Ujo in pansori

[2.14] According to Lee, scenes based on jajinmori jangdan [rhythmic pattern, literally means “long and short”], such as “Gungja norae” “궁자노래” [The Song of Gungja] and “Sinyeon maji” “신연맞이” [New Leader Inauguration] in Chunhyang-ga, are frequently referred to as Ujo by pansori singers. Through these, Lee encapsulates Ujo’s distinctive qualities.

Example 2-5. Lee’s Ujo in pansori

(click to enlarge)

Examining the melody of “Sinyeon maji” in the Jeong-Eungmin style reveals that the majority of its tunes follow the same basic melodic structure of re-do-La or La-do-re at the beginning; the pitches that make up this structure are La, do, re, mi, and sol, with La, re, and mi serving as the prominent pitches. It is a tori [musical dialect] with yoseong on sol, toeseong on do, and the cadence on La or re (Lee 2002, 216).(17)

[2.15] Lee’s description of Ujo’s traits recalls those of scenes in jajinmori jangdan.(18) Lee specifies “jajinmori-Ujo” to distinguish it from Ujo scenes in other jangdan. Additionally, he notes that Ujo based on jajinmori jangdan in pansori has the same La-re-mi structure as Ujo in jinyang jangdan in gayageum sanjo;(19) this indicates that gayageum sanjo and pansori strongly correspond with each other. The La-re-mi structure in pansori Ujo is also related to Kim Yundeok’s 1970s statement that Ujo is “a mode higher than a whole step,” since it is a step higher than the Sol-do-re structure in pansori Pyeongjo (Lee 2002, 218).

2) Lee’s Pyeongjo in pansori

[2.16] Based on the scenes of “Gisanyeongsu” “기산영수” [Gi Mountain and Yeong River] and “Hwacho taryeong” “화초타령” [The Song of the Flower] in jungjungmori jangdan,(20) which pansori singers frequently refer to as Pyeongjo, Lee outlines the qualities of Pyeongjo in pansori.

Example 2-6. Lee’s Pyeongjo in pansori

(click to enlarge)

I classify Pyeongjo in pansori as a tori, which in many cases has the basic melodic frame, Sol-do-re-do; the constituent notes from the frame are therefore Sol, La, do, re, and mi (or fa); the cadential note, do, is recognized as the tonic, as people call it “cheong”; Sol, do, and re are significant notes with a high frequency of appearance, among the constituent notes; sigimsae is distinctive, such as sol in a trembling voice (yoseong) and re in a flowing down sound (toeseong) (Lee 2002, 213–14).

[2.17] Lee’s Pyeongjo in pansori has the same features as Pyeongjo sequences in jungjungmori jangdan; to set it apart from the other Pyeongjo scenes, he refers to it as “jungjungmori-Pyeongjo.” According to Lee, mi and fa are flexible constituent notes; depending on the pansori performer, these notes could be sung a little higher or lower. This is where Lee’s theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo diverge most prominently from Baek’s. These flexible notes [mi or fa] are sangcheong in Baek’s Ujo and Pyeongjo theories. Baek distinguishes Ujo and Pyeongjo based on whether sangcheong is a high or low half step. Lee, however, considers these notes (mi or fa) fluid; whether they are high or low does not affect the mode because they are not important or frequently appearing notes.(21)

[2.18] Further, Pyeongjo in pansori is equivalent to Nambugyeong-tori (Seongjupuri-tori) in folk songs, connected to Pyeongjo in gayageum sanjo such as Seokhwajje 석화제 scenes of Ham-Dongjeongweol ryu 류 [school] gayageum sanjo,(22) and corresponds to Gyemyeonjo in contemporary gagok.

[2.19] Lee covers note sets and cadence notes (i.e., the functions of each tone), frequency of occurrence (i.e., weight of each note and main melodic structures), and sigimsae (e.g., yoseong and toeseong) in explaining Ujo and Pyeongjo. Lee’s explanation is related to his theory of tori; he lists four components as criteria for distinguishing tori of folk songs, constituent note set, each constituent note’s function, weight, and sigimsae (Lee 2000, 521–25). In other words, Lee’s Ujo and Pyeongjo theories in pansori are used in conjunction with the tori theory. As a result, the notes’ function, weight, and sigimsae are also considered significant factors along with constituent notes in determining modes.

[2.20] However, Lee claims that Ujo in pansori is clearly shown in the jajinmori jangdan sequences, Pyeongjo is primarily seen in the jungjungmori scenes, and jinyang and jungmori jangdan(23) scenes present the combined features of Ujo and Pyeongjo.(24) As a result, for jinyang sequences other than Gyemyeonjo, it is difficult to consistently determine the use of Ujo or Pyeongjo; it is reasonable to determine “jinyang-Ujo and Pyeongjo” or jinyang-Pyeongjo and Ujo,” and the same is true for jungmori jangdan. Until the 1960s, the appellation of the Pyeongjo scale was used specifically in gagok rather than pansori, hence, all modes that had not belonged to Gyemyeonjo were typically referred to as Ujo. In present days, the concept of Pyeongjo is applied to pansori, which enabled the concepts of Ujo and Pyeongjo. It is important to determine whether Ujo refers to a relative idea of Pyeongjo and Gyemyeonjo, such as jajinmori-Ujo, or whether it is a collective term for all of the counterpart modes of Gyemyeonjo.

[2.21] There needs to be more discussion of Lee’s idea of Ujo, specifically the difference between the term in a broad sense and a limited sense, as well as how to discuss Ujo when Pyeongjo and Ujo are mixed in jinyang and jungmori jangdan scenes.(25)

2.3. Comparing Baek’s and Lee’s modal theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo

[2.22] This section cross-examines Baek’s and Lee’s theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo, observes their differences and similarities, and organizes the traits that are frequently brought up in both theories.

Example 2-7. Baek’s and Lee’s Ujo theories in pansori

(click to enlarge)

[2.23] There is a difference in the constituent notes of Baek’s and Lee’s Ujo theories in pansori (Example 2.7). Baek identifies Sol, La, do, re, and mi; Lee uses La, do, re, mi, and sol.(26)

Example 2-8. Baek’s Jin-Ujo structure and Lee’s Ujo in pansori

(click to enlarge)

[2.24] According to Baek’s theory, the perfect fourths between haboncheong and sangboncheong in Jin-Ujo (Example 2.8) heighten the mood and cause the tonic to be raised a step (Baek 1996, 49–54). As a result, the “La-re” structure in Lee’s theory and the “haboncheong-sangboncheong” structure in Baek’s theory are identical.

[2.25] The three categories of Ujo that Baek specifies are Jin-Ujo, Pyeong-Ujo, and Gagokseong-Ujo. Among them, Jin-Ujo prominently displays the traits of Ujo; Pyeong-Ujo exhibits the qualities of Ujo-gil on seongeum in Pyeongjo; and Gagokseong-Ujo designates music that incorporates gagok’s singing styles (Baek 1996, 49–54). The qualities that appear in Jin-Ujo—not Pyeong-Ujo or Gagokseung-Ujo—clarify the features of Ujo in pansori where the note, re, serves as the tonic when the fourth interval of La-re in Jin-Ujo appears. This interval also falls within Lee’s La-re interval, which is his fourth interval structure. As a result, Lee’s “jajinmori-Ujo”—Ujo as a counterpart of Pyeongjo and Gyemyeonjo, not generally as a counter concept of Gyemyeonjo—and Baek’s Jin-Ujo share a resemblance. The following explanation in Baek’s text lends credence to this assessment.

The frame of Pyeongjo-gil elevates its key and intensifies its seongeum (vocal timbre), giving the qualities of the constituent notes energetic feelings similar to those of Ujo (Baek 1996, 58).

Example 2-9. Baek’s and Lee’s Pyeongjo theories in pansori

(click to enlarge)

[2.26] Following this, the constituent notes of Pyeongjo in pansori organized by Baek are re, mi, sol, la, and do’, and by Lee, Sol, La, do, re, and mi (Example 2.9).(27)

Example 2-10. Baek’s constituent notes and structures in Pyeongjo vs. Lee’s Pyeongjo in pansori

(click to enlarge)

[2.27] The individual notes that make up Pyeongjo have a set of purposes and features in accordance with Baek’s theory (Example 2.10). “1) haboncheong appears less often, 2) the frequent occurrence of the fourth interval progression between hacheong and boncheong and the second interval progression between boncheong and sangboncheong, 3) the property of vibration in hacheong, 4) sangboncheong flows down to boncheong, trembles lightly, or uses sangcheong as an appoggiatura, and 5) some of the performers sing sangcheong a semitone lower because of its unstable pitch.” These five characteristics correlate to Lee’s jungjungmori-Pyeongjo, which he explains using a tori theory.

[2.28] In other words, Baek’s and Lee’s theories of Pyeongjo in pansori are organized according to the same qualities. Baek adds that, in the case of Pyeongjo, the purposes of each note are crucial.

The only distinction in the scoring is that “sangcheong” [in Pyeongjo] is one semitone higher than that in Ujo. Ujo-gil and Gyemyeon-gil, however, can be written rather accurately when illustrating the interval relationship on the staff, but Pyeongjo-gil is not adequately conveyed by the common Western staff. In other words, the functions and attributes of each note must be considered in Pyeongjo-gil, and the progression of gil is more limited than in Ujo (Baek 1996, 55–56).

[2.29] As a result, the function and sigim[sae] of each note are stressed in Pyeongjo. The function and sigim[sae] of each note, as well as the notes that make up Pyeongjo, should therefore be taken into account while determining the mode. Also, Baek’s and Lee’s respective explanations of the function and sigimsae of each note of Pyeongjo are not different.

[2.30] Then, what distinguishes Baek’s and Lee’s modal theories of pansori? The contrast between the two theories lies in what is considered most important in determining the mode. Baek clarifies that “sangcheong” is a pitch that differentiates Ujo from Pyeongjo, focusing on the individual notes. Baek contends further that the component notes are crucial for establishing the mode rather than multiple functions and features of each note in Ujo and Pyeongjo, even though he provides details of those functions and features in his article.

[2.31] In Lee’s opinion, on the other hand, the pitch of “sangcheong” does not have a substantial impact on distinguishing the mode. “Sangcheong” is used infrequently and does not play a prominent role in the primary melodic structure; hence, its tiny variations in pitch do not impact the mode. Instead, the mode is determined based on the main melodic structure per the melodic progression among frequently used notes and sigim[sae]. The “La-re (the tonic)” structure of Ujo and the “Sol-do (the tonic)” structure of Pyeongjo, along with the weight of La, yoseong on Sol, and toeseong on re, are significant factors. Although Baek and Lee describe the melodic features of Ujo and Pyeongjo similarly, the determination of the mode for each is wholly different based on their focuses.

[2.32] The crucial consideration is therefore whether to prioritize the constituent notes or the primary melodic structure and sigim[sae] in identifying the mode in pansori, taking into account the musical attributes of pansori. Sigim[sae] is not a significant focus in court or aristocratic entertainment music. [When looking at instrumental court music’s modal theory by comparison,] the vibration of string, called nonghyeon 농현 [string play], is the shallowest, and chuseong 추성 [a slow rise in pitch] and toeseong have similar qualities. Furthermore, the similarity between sigim[sae] in Pyeongjo and Gyemyeonjo leads to a similar overall atmosphere of the two modes. Modal discrimination in jeongak is solely determined by the constituent notes, and sigim[sae] or other features of each note do not influence the mode decision. Pansori is a musical genre that emphasizes emotional expression based on dramatic situations. Ujo in pansori is often described as courageous and dignified. Gyemyeonjo is characterized as mournful and imploring. These descriptions reflect the mood of sasul 사설 [comparable to recitativo in opera], being the directly expressed in the melody. The intensity of emotions is most effectively conveyed through sigimsae, with the fourth and fifth degrees occurring more frequently than the second and third degrees; there is a distinct variation in the relative occurrences of each note. Pansori ultimately highlights sigim[sae] over jeongak, with the main melodic structure based on the fourth progression between the tonic (cheong) and the note below the fourth. These unique features are expressed differently in Ujo, Pyeongjo, and Gyemyeonjo. Therefore, when determining the mode, it is essential to consider the characteristics of each tone, including sigim[sae], proportion, and function, along with the constituent notes. When discussing tori in a folk song, it is important to not only list the individual notes but also include details like shaking, bending, falling, the value of each pitch, and the cadence.

3. Ujo and Pyeongjo in gayageum sanjo

[3.1] Although pansori is vocal music and sanjo is instrumental music, they are considered to be fundamentally the same genre. This is because pansori influenced the creation of sanjo, which originated with sinawi 시나위 [improvised instrumental ensemble], shamanistic songs from southwest Korea. Thus, the same mode theory ought to account for both pansori and sanjo. This section analyzes previous research on gayageum sanjo by connecting it to Baek’s and Lee’s modal theories of pansori.

3.1. [Kim Jeongja’s analysis] (Kim 1969)(28)

[3.2] Kim 1969 is the seminal work on gayageum sanjo modes. The preface of this article introduces the research object and purpose.

Gayageum sanjo typically comprises six movements: jinyangjo, jungmori, jungjungmori, jajinmori, hwimori, and danmori; it commonly utilizes Ujo, Gyemyeonjo, and Pyeongjo.

In this way, based on the jinyangjo movements of Kim Byeongho, Kim Yundeok, and Seong Geumyeon, I investigate Ujo and Gyemyeonjo, which occupy a considerable part among various modes. . . .

Korean music differs from Western music in terms of its constituent notes, known as scales with specific pitch relationships, which are inadequate for explaining the mode of Ujo or Gyemyeonjo.

In order to distinguish the qualities of Ujo and Gyemyeonjo in gayageum sanjo, I will thus search for the constituent notes that are present in both modes and compare the melodic pattern, pitch, and nonghyeon (i.e., timbre).(29)

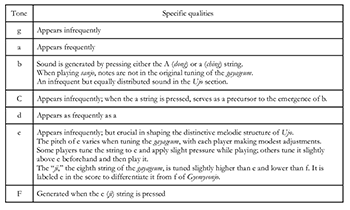

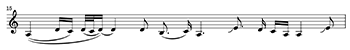

Example 3-1. Constituent notes and characteristics of the Ujo section tones in the jinyangjo movement in gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

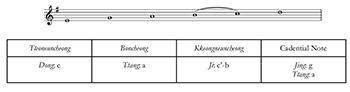

[3.3] Kim Jeongja analyzes the Ujo section of the jinyangjo movement in gayageum sanjo by Kim Byeongho, Kim Yundeok, and Seong Geumyeon. The analysis presents the seven constituent notes: g, a, b, c, d, e, and f. The following comprehensive explanation was provided for each of these notes (Example 3.1).

[3.4] Kim details the properties of each sound in Ujo, identifying the primary constituent notes as g, a, b, d, and e, while excluding c and f. She argues that a, b, d, and e are the distinctive tones of Ujo, as these four notes are seldom found in Gyemyeonjo. She also discusses the cadence type, the cadential note, and the tonic of the Ujo section.

Ujo of gayageum sanjo finishes with d (ttang), which is often a fourth rising cadence that ascends from A (dong) to d (ttang) and ends, with the exception of the ending with A (dong) in the Seong Geumyeon sanjo’s second chapter of Ujo.

It is challenging to identify the cadential note in Ujo of gayageum sanjo based on the difference in the frequency of appearances between a and d, but d provides significantly more stability than a. This is because the tonic is a pitch that appears frequently and provides stability. D is a cadential note, while a is before the cadential note, according to the cadence of Ujo. Based on this, d seems to be the tonic of Ujo in gayageum sanjo.

Example 3-2. Rhythmic cycle 10 in the jinyangjo movement of Kim Yundeok’s gayageum sanjo (Kim 1969, 12, 25)

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] Kim concludes by stating that the five notes g, a, b, d, and e are the constituent notes for the jinyangjo-Ujo part of gayageum sanjo; the cadence is a fourth ascending cadence from A to d; the cadential note is d; and the tonic is d. She proposes that the a-e-d progression is the primary melodic type of Ujo, and that Kim Yundeok’s gayageum sanjo, specifically the rhythmic cycle 10 of jinyangjo, is an example of it.(30)

Example 3-3. Rhythmic cycles 16–17 in the jinyangjo movement of Kim-Byeongho ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

Example 3-4. Rhythmic cycles 13–14 in the jinyangjo movement of Kim-Yundeok ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.6] Kim Jeongja states that the fundamental notes of Ujo in gayageum sanjo consist of the five notes g, a, b, d, and e, with the main range beginning at g. Upon examining Kim’s score, it is evident that the primary range in the Ujo section of the score is A–g, rather than G–e as indicated in Examples 3.3 and 3.4.

Example 3-5. Comparing Kim Jeongja’s analysis of jinyangjo-Ujo in gayageum sanjo with Baek’s and Lee’s modal theories in pansori

(click to enlarge)

[3.7] Kim categorizes the primary melodic structure as a-e-d; the cadence as a fourth ascending cadence from A to d; and the tonic as d. The constituent notes of Ujo in gayageum sanjo are A, B, d, e, and g, rather than g, a, b, d, and e. I will link Kim’s Ujo in gayageum sanjo, which alters the primary musical range, to Baek’s and Lee’s modal theories of pansori.

[3.8] Kim’s layout of the five notes A, B, d, e, and g consists of major 2nd–minor 3rd–major 2nd–minor 3rd intervals, which are identical to Baek’s constituent tones and intervals for Pyeongjo. In Lee’s Pyeongjo, the note mi/fa is interchangeable, indicating that the pitch intervals remain consistent. Both Baek and Lee emphasize the significance of yoseong on hacheong;(31) Kim’s score occasionally incorporates nonghyeon on the corresponding note, A. Furthermore, considering haboncheong’s infrequency, Kim’s Ujo is related to Baek and Lee’s Pyeongjo.

[3.9] Does this mean that Kim’s interpretation of the first Ujo section of jinyangjo in gayageum sanjo should be related to Pyeongjo in pansori? In this instance, the mode labels between sanjo and pansori become incongruent. Pansori Pyeongjo’s sangboncheong features toeseong, yoseong, and decorative sounds, while Kim’s Ujo in gayageum sanjo contains sangboncheong that does not have these traits. The infrequent usage of sigim[sae] on sangboncheong and the occasional use of yoseong on sangcheong are related to Lee’s Ujo. In Examples 3.2, 3.3, and 3.4, neither toeseong nor yoseong are used on e, which corresponds to sangboncheong, and yoseong is employed on g, which corresponds to sangcheong. It is difficult to determine if the note for haboncheong is c or b. It is because Kim initially presents both b and c as constituent notes, and the pitch of b is not originally tuned in gayageum when playing sanjo. To put it another way, Kim’s five constituent notes indicate that there is a connection between Baek and Lee’s Pyeongjo and jinyangjo-Ujo in gayageum sanjo. However, when considering the melodic progression and sigim[sae], Lee’s Ujo and jinyangjo-Ujo of gayageum sanjo are more closely related.

3.2. [Lee Jaesuk’s analysis] (Lee 1969)(32)

1) Lee Jaesuk’s jinyangjo-Ujo in gayageum sanjo

[3.10] Lee 1969 was published alongside Kim’s article. Lee Jaesuk examines the structure and various modes in the jinyangjo movement in gayageum sanjo from five different schools: Han-Seonggi ryu, Kang-Taehong ryu, Kim-Byeongho ryu, Kim-Yundeok ryu, and Park-Sanggeun ryu (Seong-Geumyeon ryu). The framework of the jinyangjo movement in gayageum sanjo consists of Ujo–Doljang–Pyeongjo–Gyemyeonjo and has consistent traits across the various schools.

Han-Seonggi ryu, Kim-Byeongho ryu, and Park-Sanggeun ryu follow a pattern starting with Ujo and ending with Doljang (modulatory passage), Pyeongjo, and Gyemyeonjo. Kang-Taehong ryu and Kim-Yundeok ryu also start with Ujo, progress through Doljang, Pyeongjo, and Gyemyeonjo, and conclude with Ujo in the final rhythmic cycle. The structures of sanjo in each ryu are identical in terms of the constituent modes and their sequence, with the exception of Ujo in the last rhythmic cycle of Kang-Taehong ryu and Kim-Yundeok ryu. The sanjos are all somewhat different, though, when each mode is broken down into smaller parts (Lee 1969, 136).

Example 3-6. Lee Jaesuk’s analysis of Ujo in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

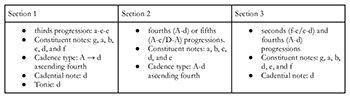

[3.11] The initial phase of the jinyangjo movement, known as the Ujo phase, is commonly segmented into three sections. Lee details the features of each section using Ujo in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu,(33) as shown in Example 3.6.(34)

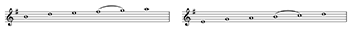

[3.12] Upon reviewing the summaries presented in the score, it is evident that the thirds progression is commonly utilized in the first section of Ujo, particularly in the rhythmic cycles 5 and 7 of Example 3.7. While the fourths progression prevails in sections 2 and 3, the fifths and seconds progressions are also employed, as observed in Examples 3.8 and 3.9.

Example 3-7. Rhythmic cycles 5 and 7 in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo (click to enlarge) | Example 3-8. Rhythmic cycles 13 and 15 in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo (click to enlarge) |

Example 3-9. Rhythmic cycle 21 in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo (click to enlarge) | Example 3-10. Comparing Lee Jaesuk’s analysis of jinyangjo-Ujo in gayageum sanjo with Baek’s and Lee’s modal theories in pansori (click to enlarge) |

[3.13] As in the rhythmic cycle 13 in Example 3.8, the rising fourth cadence type, from A to d, is used most of the time, with d being both the cadential note and the tonic. Sections 1–3 differ in how the constituent notes are presented. The main musical range for Lee Jaesuk begins at g, as it did for Kim Jeongja. However, as seen in Example 3.9, the main range actually begins at a. That being said, if starting on a and naming the constituent pitches of sections 1–3, they are a, b/c, d, e/f, and g.

[3.14] The features of Ujo in gayageum sanjo provided by Lee Jaesuk may be compared with Baek’s and Lee’s theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori.

[3.15] Lee Jaesuk proposes using six notes, instead of five, to comprise Ujo. However, due to variations in how the component notes are presented in different sections, it is uncertain whether the notes B or c and e or f should be considered as constituent notes in the mode. Upon examining the score written by Lee Jaesuk, B and c occasionally occur in conjunction within a rhythmic pattern (Example 3.11), and c appears frequently (Example 3.12). While the usage of c surpasses that of B, it is somewhat challenging to establish a connection between the findings of Lee Jaesuk’s analysis and the theories proposed by Baek and Lee on Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori, specifically in terms of the constituent pitches.

Example 3-11. Rhythmic cycle 15 in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo (click to enlarge) | Example 3-12. Rhythmic cycle 10 in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo (click to enlarge) |

[3.16] Therefore, while considering the fundamental melodic structure and the individual features of each note, the relationship to Baek and Lee’s Pyeongjo is not relevant. The score does not include any information about the weight of haboncheong, nonghyeon on hacheong, and toeseong and yoseong on sangboncheong, nor does it include these aspects in the transcription. Ultimately, the relationship between Baek and Lee’s Ujo can be attributed to the basic melodic structure, sigim[sae], and function of each note rather than the constituent notes and pitch intervals of each note.

2) Lee Jaesuk’s jinyangjo-Pyeongjo in gayageum sanjo

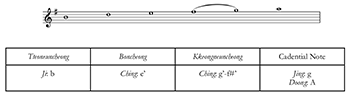

[3.17] Lee Jaesuk’s text does not clearly discuss the qualities of Pyeongjo in gayageum sanjo. The constituent notes are identified as c, d, f, g, and a, with the additional presence of e (Lee 1969, 142). However, the tonic is not explicitly defined, and there is a lack of elucidation regarding the function or attributes of each note. She writes that “g (jjing) does not have as much nonghyeon (vibrato) as in Gyemyeonjo” (Lee 1969, 150), indicating that g correlates to Gyemyeonjo’s vibrating sound. From this, we can only circumscribe that the scale consists of g, a, c, d, and f. In this perspective, c is supposed to be the tonic.

Example 3-13. Pyeongjo in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo (rhythmic cycles 33–36)

(click to enlarge)

[3.18] The score presented in the article provides a summary of the characteristics of Pyeongjo. In the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo, Pyeongjo exhibits the characteristics of Baek and Lee’s Pyeongjo (Example 3.13). The constituent notes of Pyeongjo are g, a, c, d, and e/f. Only in the rhythmic cycle 35, the melody is led by c, and various sigim[sae]s are added to d. Furthermore, the melody progresses differently in other sections, with g concluding the rhythmic cycle.

Example 3-14. Rhythmic cycles 26–30 in the jinyangjo movement of Park-Sanggeun ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.19] In the supplemental score of Lee Jaesuk’s article, the three rhythmic cycles of Pyeongjo in the jinyangjo movement of Park-Sanggeun ryu gayageum sanjo exhibit characteristics that are more firmly established than those of Han-Seonggi ryu.

[3.20] Lee Jaesuk analyzes rhythmic cycles 26–28 as Pyeongjo in the aforementioned scores.

[3.21] In the Pyeongjo section, similar to the Han-Seonggi ryu, it is ambiguous whether c’ is the tonic, as it appears that both g and c’ function as the tonic. Nevertheless, during the third and fourth beats of the rhythmic cycle 26, if it is held a long time, g becomes nonghyeon. Similarly, in the rhythmic cycle 27, a seconds progression between c’ and d’ [or vice versa] occurs often, and the fourth note of the rhythmic cycle 27, d, exhibits nonghyeon.

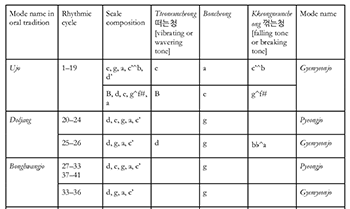

Example 3-15. The constituent notes and their characteristics of Pyeongjo in the jinyangjo movement of gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.22] Example 3.15 shows the constitutive notes and their features in Lee Jaesuk’s interpretation of Han-Seonggi ryu’s and Park-Sanggeun ryu’s transcriptions, focusing on the section Lee analyzes as Pyeongjo.

[3.23] The aforementioned features—namely, nonghyeon on g, the diverse sigim[sae] associated with d, and the seconds progression of c–d—are linked to the distinctive attributes of each note of Pyeongjo as identified by Baek and Lee if we interpret c as the tonic.

[3.24] Lee Jaesuk’s analysis of Ujo and Pyeongjo in the jinyangjo movement of gayageum sanjo reveals that the constituent notes of these modes cannot be distilled into five notes; instead, they employ various notes flexibly. Hence, it is challenging to connect the two modes above and the modal theories proposed by Baek and Lee based only on the constituent notes. Nevertheless, by examining the primary melodic structure, cadence pattern, the tonic, sigim[sae], and frequency of each note, it is possible to establish a correlation between the proposed hypotheses and Lee’s and Baek’s theories. Put simply, in sanjo and pansori, the primary factors influencing the mode are the melodic progression and sigim[sae], which establish the song’s mood, rather than the slightly higher or lower pitch of the constituent notes.

3.3. [Kim Haesuk’s analysis] (Kim 1987 and 1995)(35)

[3.25] Kim Haesuk has authored multiple studies that examine the melody of gayageum sanjo (Kim 1982, 1984, 1987, 1992, 1993, 1995, and 2005). In two of her publications—Kim 1982 and 1995—she provides a comprehensive analysis of the organization of notes of sanjo. The author’s analysis of Choe-Oksan ryu sanjo is enhanced and expanded upon in “Chapter 1: Tone organization of gayageum sanjo” of Kim 1987. This study examines Kim Haesuk’s analysis of Ujo and Pyeongjo in gayageum sanjo, with a specific focus on Chapter 1 of Kim 1987 and Kim 1995.

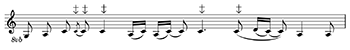

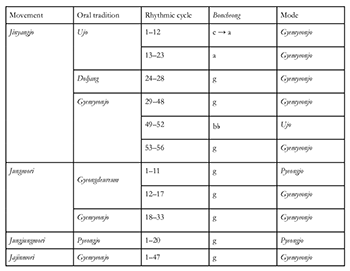

Example 3-16. Kim Haesuk’s interpretation of the jinyangjo movement of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[3.26] Baek’s mode theory is the foundation of Kim Haesuk’s research on gayageum sanjo (Kim 1987, 11). This differs from the research of Kim Jeongja and Lee Jaesuk, who provide a concise overview of Ujo and Pyeongjo attributes in gayageum sanjo, without considering the impact of Baek, Lee, and other pansori and sanjo modal theories.

[3.27] Based on Baek’s pansori mode theory, Kim analyzes the musical mode employed in the jinyangjo movement of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo.(36) The findings are presented in Example 3.16.

[3.28] Kim Haesuk interprets the rhythmic cycles 1–19 of the first half of the jinyangjo movement—designated orally as Ujo—as Gyemyeonjo, the rhythmic cycles 20–24 in Doljang, the rhythmic cycles 27–33 and 37–41 in Bonghwangjo as Pyeongjo, and the rhythmic cycles 52–53 in Byeon-gyemyeon and the rhythmic cycles 77–80 in Saengsamcheong as Ujo.

Example 3-17. Kim Haesuk’s interpretation of the modes of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.29] According to oral tradition, the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo consists of Ujo, Doljang, and Gyemyeonjo.(37) Kim Haesuk, on the other hand, construed the Ujo part as Gyemyeonjo and designated the rhythmic cycles 49–52, which constitute Gyemyeonjo, as Ujo. She also interpreted certain aspects of Gyeongdeureum in the jungmori movement as Pyeongjo, and viewed the entirety of the jungjungmori movement as Pyeongjo.

[3.30] In other words, Kim Jeongja and Lee Jaesuk accept Ujo, Pyeongjo, and Gyemyeonjo based on oral tradition and lay out their respective constituent notes and sigim[sae], while Kim Haesuk analyzes each part based on Baek’s mode theory. The result is that the part called “Ujo” in oral tradition is interpreted by Kim Haesuk as Gyemyeonjo, and the part called “Gyemyeonjo” in oral tradition is interpreted as Ujo.

1) Kim Haesuk’s analysis of Ujo in oral tradition

[3.31] The initial segment of the jinyangjo movement in Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo, specifically the rhythmic cycles 1–3, 11–19, and 4–10, which align with Ujo as per oral tradition, is interpreted by Kim Haesuk as Gyemyeonjo (Examples 3.18 and 3.19).(38)

Example 3-18. Kim Haesuk’s modal analysis of the jinyangjo movement of Ujo in oral tradition of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo (rhythmic cycles 1–3 and 11–19) (click to enlarge) | Example 3-19. The jinyangjo movement of Ujo in oral tradition of Choe-Oksan ryu (rhythmic cycles 4–10) (click to enlarge) |

Example 3-20. The jinyangjo movement of Ujo in oral tradition of of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo (rhythmic cycles 1–23)

(click to enlarge)

[3.32] Furthermore, it should be noted that the Ujo section in the jinyangjo movement of Han-Seonggi ryu gayageum sanjo begins with e (ching)-boncheong of Gyemyeonjo and transitions to a (ttang)-boncheong of Gyemyeonjo, shown in Example 3.20.

[3.33] However, Kim Haesuk explains that the oral tradition’s Ujo part is Gyemyeonjo from the perspective of the modal theory, but it is different from Gyemyeonjo in actual sanjo.

The emotional impact of kkeongneuncheong varies based on the string’s position or the technique employed. Kkeongneuncheong in the gaks [sub-units of four or six beats of each rhythmic cycle] 2 and 7 do not exhibit the characteristic of being kkeongneuncheongs, as they descend in a manner resembling toeseong. Furthermore, kkeongneuncheongs in the gaks 15–16 flow with trembling, while kkeongneuncheongs in the gak 11 are immediately broken, but the feeling varies when performed on strings, ddong or ttang. The observed variations in performance styles can be attributed to significant alterations in dynamics or timbre (seongeum). Hence, a musical composition employing the identical mode can be conveyed by either Ujo or Gyemyeonjo.

Ham Dongjeongwol elucidated that the Ujo section of the jinyangjo movement “concludes with Ujo including Doljang,” or it is referred to as “Gagokseong-Ujo.” This implies that the term “Ujo” is acknowledged as a means of musical expression or dynamics rather than a specific mode. The primary focus in actual musical performance is music’s intrinsic nature, rather than musical structure, form, or mode, which music theorists seek to reveal. Hence, within the context of oral transmission, this phrase would have been significant in effectively communicating the underlying significance of the music. Accordingly, the part that makes up Gyemyeonjo might be conceptualized as “Ujo” in terms of its dynamics.

[3.34] To clarify, Kim interprets the Ujo part in the jinyangjo movement of gayageum sanjo as Gyemyeonjo, comprised of mi, sol, la, do-si, and re. However, the note known as kkeongneuncheong is not broken—like that in Gyemyeonjo—but descends like toeseong. For this reason, this section is called Ujo rather than Gyemyeonjo. In this instance, the term “Ujo” is used based on musical expressions (i.e., seongeum) rather than the scale.

Example 3-21. Rhythmic cycles 2 and 7 in the jinyangjo movement of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.35] The musical notation for the rhythmic cycles 2 and 7, which exhibit a toeseong-like flow [between c and b] as quoted above, is as follows (Example 3.21).

Example 3-22. Rhythmic cycles 5–8 in the jinyangjo movement of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.36] The expression of kkeongneuncheong exhibits distinct characteristics compared to Gyemyeonjo, and this section of the melodic progression similarly deviates from the conventional progression observed in Gyemyeonjo. Example 3.22 shows a section in which the tonic on e and the tonic on a are combined. The tonic on e is played during the rhythmic cycle 5, the tonic on a during the cycles 6–7. G is commonly used at the end of the cycle 7 to lead into 8, which then transitions to e-cheong. The note g is used frequently throughout this transition. Specifically, during the initial and subsequent beats of the cycle 6, g is inserted into the ascending fourth progression e–a.

[3.37] Baek emphasizes on the role of haboncheong in modulation and transposition, specifically linking the function of g to the transformation process shown above. In contrast, g is nearly omitted in Gyemyeonjo. Baek’s theory, which Kim adopts, does not include any intermediate tones between hacheong (e) and boncheong (a). To clarify, Kim Haesuk analyzed the Ujo section of the jinyangjo movement in gayageum sanjo using the Gyemyeonjo scale. However, it is important to note that the characteristics and melodic progression of each note and sigim[sae] in the Ujo section are distinct from those found in the Gyemyeonjo mode. For these reasons, Kim Haesuk adopts an ambiguous stance by labeling this section as “considered to be Ujo from a dynamic perspective,” rather than clearly stating that this is Gyemyeonjo.

Example 3-23. The mode of rhythmic cycles 52–53 of Byeon-gyemyeon in the jinyangjo movement of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.38] Alternatively, while examining the part Kim Haesuk interprets as Ujo within the Gyemyeonjo section in gayageum sanjo, it becomes evident that this specific section has been interpreted as Ujo following Baek’s modal theory.(39)

[3.39] In some situations, it may be improper to identify Ujo as either mode or seongeum. Furthermore, this is inconsistent with Baek’s thesis, which differentiates seongeum from gil in the context of pansori and sanjo modes, but ultimately relies on gil to establish mode.

[3.40] Kim Haesuk’s analysis uncovers contradictory issues that arise from the assertion that, while examining sanjo, the mode and seongeum should be assessed jointly. An added problem regarding the interpretation of the oral-transmission Ujo section as Gyemyeonjo is that it has been customary to transcribe gayageum sanjo at a fifth higher than the actual sound.(40) That is, the notated pitches, e, g, a, b-c’, and d’, in fact, correspond to the sounding pitches A, c, d, e-f, and g.

2) Kim Haesuk’s analysis of Pyeongjo

Example 3-24. Pyeongjo in Doljang and Bonghwangjo in the jinyangjo movement of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.41] Kim Haesuk interprets the jinyangjo movement of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo, the gaks 20–24 in Doljang, and the gaks 27–33 and 33–36 in Bonghwangjo as Pyeongjo as shown below.

[3.42] Incorporating Baek and Lee’s theories, Kim Haesuk’s analysis of this section interprets it as Pyeongjo. It is understood as Pyeongjo due either to its constituent notes in Baek’s theory or its melodic progression and sigim[sae] in Lee’s theory.

Example 3-25. Rhythmic cycles 77–80 of Saengsamcheong in the jinyangjo movement of Choe-Oksan ryu gayageum sanjo

(click to enlarge)

[3.43] However, according to Kim Haesuk’s interpretation, the gaks 77–80 of Saengsamcheong can be identified as Ujo, specifically consisting of f, g,

[3.44] In other words, the interpretation of the mode in the rhythmic cycles 77–80 of Saengsamcheong varies depending on whether it adheres to Baek’s theory of note composition or Lee’s theory of the significance of each note based on the primary melodic structure and sigim[sae].

[3.45] Applying Baek’s mode theory to analyze gayageum sanjo, the Ujo section in the oral tradition may lack clarity. One is led to described ambiguously as “It should be Gyemyeon-gil, but due to the absence of kkeongnuncheong and its divergence from the typical progression, it is called Ujo, following seongeum.” Conversely, certain sections of Byeon-gyemyeon and Saengsamcheong [which are not typically referred to as Gyemyeonjo], should be interpreted as Ujo. Lee’s modal theory of pansori allows for analyzing and designating the initial phase of the jinyangjo movement, referred to as Ujo in oral tradition, as Ujo. In addition, Doljang, Bonghwangjo, and certain sections of Saengsamcheong can be interpreted as Pyeongjo. This aligns with the prior research on the structure of gayageum sanjo (Lee 1969, 136), which indicates that the initial segment of the jinyangjo movement, regardless of the specific school, commences with Ujo and then progresses to Doljang–Pyeongjo–Gyemyeonjo.

4. Conclusion

[4.1] A multitude of Korean musicologists extensively investigated modes in pansori. Nevertheless, they have not reached a unanimous agreement, and the music is examined through different approaches. Baek’s and Lee’s modal theories are most widely accepted. These two researchers have identical beliefs regarding Gyemyeonjo but diverge in their interpretations of Ujo and Pyeongjo. Furthermore, subsequent academics have utilized the distinct ideas of Ujo and Pyeongjo. This study focused on analyzing Baek’s and Lee’s theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori and examined their similarities and differences. The findings were cross-examined with the prior investigations into sanjo, which shares the same musical attributes as pansori.

[4.2] Baek’s Ujo in pansori consists of the notes sol, la, do, re, and mi, with do serving as the tonic; Baek’s Pyeongjo is re, mi, sol, la, and do, with sol as the tonic. The crucial factor in differentiating between Ujo and Pyeongjo is the height of sangcheong. If the distance between boncheong and sangcheong is a major 3rd, Ujo is indicated; if the interval is a perfect 4th, Pyeongjo is the mode. On the other hand, Lee’s Ujo in pansori, which is often showcased in the jajinmori jangdan portion, contains la, do, re, mi, and sol while the primary tones are la, re, and mi. These three notes form the primary melodic structure. Toeseong is on do and it ends with la or re. Lee’s Pyeongjo is widely used in the jungjungmori jangdan section, consisting of sol, la, do, re, and mi (or fa); mi and fa are interchangeable. The basic melodic structure consists of sol, do, and re, which appear frequently. Yoseong is on sol and toeseong on re, while do serves as both the cadential note and the tonic. As demonstrated, Baek distinguishes modes based on the constituent notes and the intervals between them, whereas Lee takes into account the constituent notes, the main melodic structure, sigimsae, and the cadential note wholistically.

[4.3] Thus, Baek’s and Lee’s theories appear to diverge considerably. However, the specific traits of each Ujo and Pyeongjo composition as described in Baek’s writings show a connection to Lee’s summary of the melodic structure and sigimsae of Ujo and Pyeongjo. These include the la-re structure in Jin-Ujo, the rare use of haboncheong in Pyeongjo, occasional yoseong on hacheong, frequent fourths progressions between hacheong and boncheong, and the seconds between boncheong and sangboncheong. It is noteworthy that sangboncheong features a flowing or slightly trembling note and may use sangcheong as an appoggiatura; and that the pitch of sangcheong can be unstable depending on the singers. In addition, Baek highlights the role and significance of each tone when compared to Ujo in the context of Pyeongjo, which aligns with Lee’s theory on Pyeongjo. In essence, Baek and Lee have similar beliefs regarding Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori. However, their contrasting viewpoints on the key factors that determine modes lead to divergent conclusions.

[4.4] What can be said about sanjo, a musical genre that shares the same characteristics with pansori? Upon reviewing analyses of sanjo by Kim Jeongja, Lee Jaesuk, and Kim Haesuk, it becomes evident that there are constraints when attempting to analyze sanjo solely based on its constituent notes. It is also essential to consider toeseong, yoseong, ornamental notes, and the melodic progression to accurately determine Ujo, Pyeongjo, and Gyemyeonjo. Furthermore, Kim Haesuk’s research, which examines sanjo using Baek’s theory, proposes that the term “Ujo” might potentially be attributed to the scale or utilized for seongeum. Furthermore, she interprets Byeon-gyemyeon or a section of Saengsamcheong as Ujo. However, this interpretation is solely based on the constituent notes in Baek’s theory and does not align with the real musical content.

[4.5] Consequently, it is insufficient to determine the modes in pansori and sanjo solely by looking at the constituent notes. It is necessary to look into each note’s function and characteristics. This is different from how one identifies modes based only on the notes played in court music or entertainment music for the nobility. Folk music, such as pansori and sanjo, is characterized by the presence of numerous embellishments in each tone and emphasizes the fullest expression of emotions. Therefore, when analyzing folk music, one should consider the additional characteristics of the tone alongside the constituent notes. This is similar to the inclusion of yoseong, toeseong, and kkeoknuneum in determining the character of tori.

Seokyoung Kim

The University of Texas at Austin

Butler School of Music

Austin, TX 78712-1555

seokyoung.kim@utexas.edu

Works Cited

Baek, Daewoong 백대웅. 1982. Hanguk-jeontong-eumak-eui seonyul-gujo 한국전통음악의 선율구조 [Melodic Structure of Traditional Korean Music]. Daegwang Munhwasa 대광문화사.

—————. 1995. Hanguk-jeontong-eumak-eui seonyul-gujo 한국전통음악의 선율구조 [Melodic Structure of Traditional Korean Music]. Oulim Books 도서출판 어울림.

—————. 1996. Dasi boneun pansori 다시 보는 판소리 [Pansori Revisited]. Oulim Books 도서출판 어울림.

Ban, Haesung 반혜성. 1998. Jeontong-eumak-gaeron 전통음악개론 [Introduction to Traditional Music]. Dunam Publishing House 도서출판 두남.

Chang, Sahun 장사훈 and Han Manyeong 한만영. 1975. Gugak-gaeron 국악개론 [Introduction to gugak]. Korean Musicological Society and Seoul National University Press 한국국악학회ᐧ서울대학교출판부.

Howard, Keith. 2006. Preserving Korean Music: Intangible Cultural Properties as Icons of Identity. Ashgate.

Howard, Keith, Chaesuk Lee, and Nicholas Casswell. 2008. Korean Kayagum Sanjo: A Traditional Instrumental Genre. Ashgate.

Jeong, Nosik 정노식. 1940. Joseon-changgeuksa 조선창극사 [The History of Korean Vocal Theater]. The Chosun Daily Press 조선일보 출판부.

Kim, Haesuk 김해숙, Baek Daewoong 백대웅, and Choe Taehyeon 최태현. 1999. Jeontong-eumak-gaeron 전통음악개론 [Introduction to Traditional Music]. Oulim Books 도서출판 어울림.

Kim, Haesuk 김해숙. 1982. “Choe-oksan-ryu gayageum sanjo seonyul-bunseok: jinyangjo-leul jungsimeulo 최옥산류 가야금 산조 선율분석: 진양조를 중심으로 [Melodic Analysis of Choe-Oksan Ryu Gayageum Sanjo: Focusing on Jinyangjo].” Studies in Korean Music 한국음악연구 12: 46–64.

—————. 1984. “Sim-sanggeon gayageum-sanjo-ui seonyul-guseong-wonli: jinyangjo-leul jungsimeulo 심상건 가야금산조의 선율구성원리: 진양조를 중심으로” [Melodic Composition Principles of Sim Sanggeon’s Gayageum Sanjo: Focusing on Jinyangjo]. Studies in Korean Music 한국음악연구 13·14: 45–66.

—————. 1987. Sanjo-yeongu 산조연구 [Research on Sanjo]. Sekwang Publishing House 세광음악출판사.

—————. 1992. “Yuseonggi-eumbanui ham-dongjeongweol gayageum-sanjowa hyenohaenggwaui bigyo 유성기음반의 함동정월 가야금산조와 현행과의 비교 [Comparative Analysis of Ham Dongjeongweol’s Gayageum Sanjo on Phonograph Records and Current Rendition].” Hanguk-eumbanhak 한국음반학 2: 171–89.

—————. 1993. “Yuseonggi-eumbanui natanan gayageum sanjoui teul: kim-haeseon-ui eumban yeonjuleul jungsimeulo 유성기음반에 나타난 가야금 산조의 틀–김해선의 음반 연주를 중심으로 [Structure of Gayageum Sanjo as Depicted in Phonograph Records, with an Emphasis on the Recording Performance of Kim Haeseon].” Hanguk-eumbanhak 한국음반학 3: 77–88.

—————. 1995. “Han-seonggi gayageum-sanjo yeongu 한성기 가야금산조 연구 [Research on Han Seonggi’s Gayageum Sanjo].” Hanguk-eumbanhak 한국음반학 5: 259–69.

—————. 2005. “Gayageum-sanjo-ui seonyul-hyeongsig-ui bichueo bon geomungo-sanjo-ui seonyul-hyeongsig: jinyangjo-ui hanhayeo 가야금산조의 선율형식에 비추어 본 거문고산조의 선율형식: 진양조에 한하여 [Melody Form of Geomungo Sanjoe Viewed in Reflection of Gajageum Sanjo’s: Concerning Only on Jinyangjoe].” Hanguk-jeontong-eumakhah 한국전통음악학 6: 207–20.

Kim, Jeongja 김정자. 1969. “Gayageum-sanjo-ui ujo-wa gyemyeonjo 가야금산조의 우조와 계면조 [Ujo and Gyemeonjo in Gayageum Sanjo].” In Yi Hyegu-baksa-songsu-kinyeom eumakhak-nonchong 이혜구박사송수기념 음악학논총 [Essays in Musicology: An Offering in Celebration of Dr. Yi Hyegu on His Sixtieth Birthday]. Edited by Yi Hyegu-baksa-songsu-kinyeom pyeonjib-wiwonhoe 이혜구박사송수기념 편집위원회, 1–33. Korean Musicological Society 한국음악학회.

Kim, Yeonsu 김연수. 1967. Kim-yeonsu changbon chunhyang-ga [Kim Yeonsu’s Changbon Chunhyang-ga]. Munhwajae-gwanligug 문화재관리국.

Kim, Youngwoon 김영운. 2015. Gugak-gaeron 국악개론 [Introduction to Gugak]. Eumaksekye Publishing House 도서출판 음악세계.

Kwon, Oseong 권오성. 1999. Han-minjok-eumangnon 한민족음악론 [Korean Music Theory]. Hangmunsa Publishing House 학문사.

Lee, Bohyeong 이보형. 1971. “Pansori kwon-samdeuk seolleongje 판소리 권삼득 설렁제 [Kwon Samdeuk’s Seolleongje in Pansori].” In Seok-ju-seon-seonsaeng hoegap-ginyeom minsokhak-nonchong 석주선선생 회갑기념 민속학논총 [Essays in Folklore Studies: An Offering in Celebration of Seok Ju-Seon on Her Sixtieth Birthday]. Edited by Seok-ju-seon-seonsaeng hoegap-ginyeom minsokhak-nonchong ganhaengwi 석주선선생 회갑기념 민속학논총 간행위, 169. Tongmungwan 통문관.

—————. 1998. “Pansori-wa sanjo-eseo ujo-wa pyeongjo-ui gaenyeom-suyong-e gwanhan gochal 판소리와 산조에서 우조와 평조의 개념수용에 관한 고찰 [A Study on the Acceptance of the Concepts of Ujo and Pyeongjo in Pansori and Sanjo].” Journal of National Gugak Center 국악원논문집 10: 195–209.

—————. 2000. “Tori-eui gaenyeonm-gwa yuyonglon 토리의 개념과 유용론 [Concept and Theory of Tori].” In Soam-kwon-oseong-baksa-hwagap-ginyeom eumakhak nonchong 소암권오성박사화갑기념 음악학논총 [Essays in Musicology: An Offering in Celebration of Dr. Kwon Oseong on His Sixtieth Birthday]. Edited by Soam-kwon-oseong-baksa-hwagap-ginyeom nonmunjip balhaeng-wiwonhoe 소암권오성박사화갑기념 논문집 발행위원회, 521–25. Minsokwon 민속원.

—————. 2002. “Pansori-wa sanjo-eseo ujo-wa pyeongjo yeongu 판소리와 산조에서 우조와 평조 연구 [A Study on Ujo and Pyeongjo in Pansori and Sanjo].” Journal of the National Center for Korean Folk Performance Arts 국립민속국악원 논문집 1: 209–22.

Lee, Byong Won 이병원 and Lee Yong-Shik 이용식, eds. 2007. Korean Musicology Series 1: Music of Korea. The National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts. https://www.gugak.go.kr/site/program/board/basicboard/view?currentpage=2&menuid=001003002005&searchselect=&searchword=&pagesize=10&boardtypeid=24&boardid=1408&lang=ko.

—————. 2009. Korean Musicology Series 3: Sanjo. The National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts. https://www.gugak.go.kr/site/program/board/basicboard/view?currentpage=2&menuid=001003002005&pagesize=10&searchselect=&searchword=&boardtypeid=24&boardid=1410&lang=ko.

Lee, Jaesuk 이재숙. 1969. “Gayageum sanjo-ui teul-e daehan sogo 가야금산조의 틀에 대한 소고 [Reflection on the Structure of Gayageum Sanjo].” In Yi-hyegu-baksa-songsu-kinyeom eumakhak-nonchong 이혜구박사송수기념 음악학논총 [Essays in Musicology: An Offering in Celebration of Dr. Yi Hyegu on His Sixtieth Birthday]. Edited by Yi-hyegu-baksa-songsu-kinyeom pyeonjib-wiwonhoe 이혜구박사송수기념 편집위원회, 135–68. Korean Musicological Society 한국국악학회.

—————. 1971. Gayageum-sanjo 가야금산조 [Gayageum Sanjo]. Korean Musicological Society 한국국악학회.

—————. 1986a. Gayageum-sanjo—kim-jukpa-ryu 가야금산조–김죽파류 [Kim-Jukpa Ryu Gayageum Sanjo]. Sumundang Publishing House 수문당.

—————. 1986b. Gayageum-sanjo—seong-geumyeon-ryu 가야금산조–성금련류 [Seong-Geumyeon Ryu Gayageum Sanjo]. Sumundang Publishing House 수문당.

—————. 1987. Gayageum sanjo—seong-geumyeon-ryu 가야금산조–성금련류 [Seong-Geumyeon Ryu Gayageum Sanjo]. Sekwang Publishing House 세광음악출판사.

Lee, Yong-Shik 이용식, ed. 2008. Korean Musicology Series 2: Pansori. The National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts. https://www.gugak.go.kr/site/program/board/basicboard/view?currentpage=2&menuid=001003002005&pagesize=10&searchselect=&searchword=&boardtypeid=24&boardid=1409&lang=ko.

Moon, Jaesook 문재숙. 2009. Ihaehamyeon salanghaneun hanguk eumak 이해하면 사랑하는 한국음악 [Learning and Loving Korean Music]. Minsokwon 민속원.

National Gugak Center 국립국악원. 2000. “Yeongu-jalyo–gugak-ilon 연구자료–국악이론 [Academic Research Publications—Gugak Theory].” National Gugak Center 국립국악원. http://www.gugak.go.kr.

Park, Chan E. 2003. Voices from the Straw Mat: Toward an Ethnography of Korean Story Singing. University of Hawaii Press.

Pihl, Marshall R. 1994. The Korean Singer of Tales. Harvard University Asia Center.

Provine, Robert C., Okon Hwang, and Keith Howard. 2001. “Korea.” Grove Music Online. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.45812.

Seo, Hanbeom 서한범. 1997. Gugak tongnon 국악통론 [Gugak Theory]. Taerim Publishing House 태림출판사.

Shin, Eun-Joo 신은주. 2018. “Pansori ujo-wa pyeongjo-e daehan du ilon: baek-daewoong-gwa lee-bohyeong-ui pansori agjolon bigyo geomto 판소리 우조와 평조에 대한 두 異論–백대웅과 이보형의 판소리 악조론 비교 검토 [Two Theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo in Pansori: Comparing Baek Daewoong’s and Lee Bohyeong’s Theories of Pansori Modes].” Studies in Korean Music 한국음악연구 63: 233–68.

—————. 2019. “Gayageum-sanjo ujo-e daehan bunseog ilon gochal 가야금산조 우조에 대한 분석 이론 고찰 [Review of Analytical Theories of Ujo in Gayageum Sanjo].” Studies in Korean Music 한국음악연구 66: 67–104.

—————. 2022. “Gugak-eseo jongjieum-gwa jueum(gung)-ui gwangye-e daehan nonui 국악에서 종지음과 주음(궁)의 관계에 대한 논의 [Discussion on the Relationship between the Cadential Tone and the Tonic (gung) in Gugak]. Studies in Korean Music 한국음악연구 72: 113–44.

—————. 2024. Discussion with the translator, May 27.

Seong, Aesoon 성애순. 1986. Choe-oksan-ryu gayageum-sanjo 최옥산류 가야금산조 [Choe-Oksan Ryu Gayageum Sanjo]. Eunha Publishing Company 은하출판사.

Willoughby, Heather. 2000. “The Sound of Han: P’ansori, Timbre, and a Korean Ethos of Pain and Suffering.” Yearbook for Traditional Music 32: 17–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/3185241.

Yoon, Myeongwon 윤명원 et al. 2003. Hanguk eumakron 한국음악론 [Korean Music Theory]. Eumaksekye Publishing House 도서출판 음악세계.

Discography

Discography

GugakTV. 2021. Park Aeri 박애리–“Hwacho taryeong 화초타령 [The Song of the Flower] from Simcheong-ga 심청가 [The Song of Simchung]. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://youtu.be/ifnqCE4ZFmM?si=O4hEoWzTsYKhy0v0.

—————. 2023. Lim Hyunbin 임현빈–“Sinyeon maji 신연맞이 [New Leader Inauguration]” from Chunhyang-ga 춘향가 [The Song of Chunhyang]. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://youtu.be/IqTUoUAv_Ts?si=gLhIt1dGI5z7Lhc9.

Jang, Seo-Yoon. 2021. “Blind Sim Opening His Eyes” from Simcheong-ga 심청가 [The Song of Simchung]. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://youtu.be/IK4ebVvfXtM?si=d0U_oU4lW3qNwqha.

National Gugak Center. 2021. Lee Seungho 이승호–Choe-oksam-ryu gayageum-sanjo 최옥삼류 가야금산조 [Choe-Oksam Ryu Gayageum Sanjo]. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://youtu.be/JYooPDqD3Gg?si=W3kJRp77GayFE2A9.

Footnotes

* Originally published as Shin Eun-Joo, “Pansori ujo-wa pyeongjo-e daehan du ilon: baek daewoong-gwa lee-bohyeong-ui pansori agjolon bigyo geomto 판소리 우조와 평조에 대한 두 異論–백대웅과 이보형의 판소리 악조론 비교 검토 [Two Theories of Ujo and Pyeongjo in Pansori: Comparing Baek Daewoong’s and Lee Bohyeong’s Theories of Pansori Modes],” Studies in Korean Music 한국음악연구 63 (2018): 233–68.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: I wish to extend my thanks to Joon Park for his insightful feedback and suggestions.

PEER REVIEWER: Joon Park

Return to text

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: I wish to extend my thanks to Joon Park for his insightful feedback and suggestions.

PEER REVIEWER: Joon Park

1. See Jang (2021) and National Gugak Center (2021) for aural examples of pansori and sanjo.

Return to text

2. The five pieces are Chunhyang-ga 춘향가 [The Song of Chunhyang], Simcheong-ga 심청가 [The Song of Sim Cheong], Heungbo-ga 흥보가 [The Song of Heungbo], Sugung-ga 수궁가 [The Song of the Underwater Palace], and Jeokbyeok-ga 적벽가 [The Song of the Red Cliff]. See Lee and Lee (2007, 106–9) for details of each piece.

Return to text

3. See Pihl (1994); Willoughby (2000); Park (2003); Howard (2006); Lee and Lee (2007, 2009); Howard, Lee, and Casswell (2008); Lee (2008), for further reading on pansori and sanjo.

Return to text

4. Shin has been conducting research focusing on the evolution of Korean folk music, particularly centered around pansori and minyo (folk songs). She has made significant achievements in transcribing and analyzing orally transmitted folk music. Additionally, she is interested in establishing modal theories in traditional Korean music. She is a professor in the Department of Korean Music at Jeonbuk National University in South Korea.

Return to text

5. This challenge occurs because jos in folk music were determined retroactively, having been examined and classified by later scholars; the two modes are similar and often intermixed in performance, making it difficult to conclusively and consistently label one Ujo and the other Pyeongjo.

Return to text

6. For an aural example of Ujo, see GugakTV (2023).

Return to text

7. For an aural example of Pyeongjo, see GugakTV (2021).

Return to text

8. Shin provides a summary of the definitions of Ujo and Pyeongjo in introductory texts published from 1975 to 2015: Chang and Han 1975; Seo 1997; Ban 1998; Kim, Baek, and Choe 1999; Kwon 1999; National Gugak Center 2000; Yoon et al. 2003; Moon 2009; Kim 2015. The majority of the introductory texts have ambiguously defined pansori modes. For example, Chang and Han describe Pyeongjo as “an intermediate character between Ujo and Gyemyeonjo” or “difficult to distinguish from Ujo” (Chang and Han 1975, 195–97). See Shin’s “1. Redefinition of Ujo and Pyeongjo in pansori” below, for further explanations.

Return to text

9. Korean musicians and scholars have mainly used traditional terms to describe five pentatonic positions—gung 궁 (宮), sang 상 (商), gak 각 (角), chi 치 (徵), u 우 (羽)—originating from the Joseon dynasty, and referring to Chinese music literature, before adopting Western concepts. According to Shin (2024), the exact period when the theory of traditional Korean music began as a modern academic discipline cannot be pinpointed; however, the two most likely instigating events are the publication of pioneering scholars’ writings (e.g., Yi Hyegu’s and Chang Sahun’s) and the establishment of the Korean Musicological Society, the most representative academic society for traditional Korean music in South Korea, in 1948. Borrowing Western terms and methods was deemed necessary for communicating with Western scholarship. Furthermore, Yi, having begun his musical career as a violist and studied Western music before delving into Korean music, readily incorporated Western concepts into his explanation of Korean music. Subsequently, Korean music scholars have used Western terms. For example, Chang and Han (1975)—the most frequently used textbook on gugak in South Korea—explain sambunsonigbeob 삼분손익법 (三分損益法), which is a formula for a twelve-tone tuning system, and modes (e.g., Pyeongjo and Gyemyeonjo) with Western concepts: “It is a scale that adds a perfect 5th above and a perfect 4th below the fundamental pitch, and is similar to the Pythagorean scale,” and “[Pyeongjo is] a pentatonic scale, in other words, sol-scale” (Chang and Han 1975, 4; 18–19). For further readings about adopting Western terms in Korean music theory, see Shin (2019; 2022).

Return to text

10. Shin acknowledges that “some scholars use Western terms, such as cadence and semi-cadence, because the cadence is neither necessarily the tonic nor the cadence set to a specific note in traditional Korean music. The cadence is also flexible, depending on each master. Some genres (e.g., sanjo) can be called tonal music because they usually end with a tonic, but it is hard to say that other genres are tonal music” (Shin 2024).

Return to text

11. In 1982, Daegwang Munhwasa released the first edition. In 1995, Oulim Books published a revised edition.

Return to text

12. The terms, “hacheong, haboncheong, boncheong, sangboncheong, and sangcheong,” are used in Baek’s theory. Regardless of my opinion, I will discuss Baek’s theory using his terminology exactly as it is.

Return to text

13. In accordance with Seolleongje, Baek explains that haboncheong (“la”) creates many leaps, stretches out, and sounds vigorous when employed above the octave. Seolleongje continuously stretches out with the high-pitched “la” (la’) and develops leaps because it contains the notes sol, la, re, mi, sol’, la’, and do’. See Lee Bohyeong (1971, 176) for an explanation of Seolleongje.

Return to text

14. Baek states that hacheong in Pyeongjo does not vibrate much; he also states that hacheong in Ujo “does not have the function of trembling.” He adds that, among the varieties of Ujo in the Gagokseong-Ujo section, “the vibrating nature sometimes shows in hacheong and sangboncheong, which is characteristic of Pyeongjo.” Hacheong in Pyeongjo thus possesses a vibrating quality (Baek 1996, 47–48, 53, 56).

Return to text

15. See the previous footnote.

Return to text