Review of Here for the Hearing: Analyzing the Music in Musical Theater, ed. Michael Buchler and Gregory J. Decker

John Y. Lawrence

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.31

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

INTRODUCTION

[0.1] For years, musical theater fans hungry for a book-length analytical treatment of this repertoire have been in the position of Tony from West Side Story, singing:

Could it be? Yes, it could

Something’s coming, something good,

if I can wait.

Something’s coming, I don't know what it is

But it is gonna be great.

That something has come in the form of the volume Here for the Hearing: Analyzing the Music in Musical Theater, edited by Michael Buchler and Gregory J. Decker, featuring chapters from eleven scholars, including the editors themselves.

[0.2] As the volume’s subtitle indicates, a central premise is that most prior scholarship on musicals has been carried out by musicologists, not music theorists and analysts, and thus tends to focus on “the genre’s historical and social contexts” and “critical readings of musicals” (2). This volume, on the other hand, focuses on “examin[ing] the role musical structures play in conveying aspects of drama” (2). “Structures,” in this case, is not shorthand for form, although that is one of many parameters discussed in the volume. Indeed, one of the volume’s strengths is the staggering diversity of the contributions: a diversity of repertoire (the major case studies span the 1950s through 2010s, and there are further musical examples stretching back to the 1920s); musical parameters (including harmony, rhyme, rhythm, tonality, and topicality); and methodological orientation (including intertextuality, literary criticism, queer studies, and temporality). The field’s breadth is on full display.

[0.3] Some of the chapters in this volume are indeed great, as Tony’s words predicted; but for others, greatness is (as he sings) “out of reach.” Musical theater’s expansive stylistic vocabulary poses a potential problem for analysts: some musical conventions conform to standard music-theoretical models, but others diverge in important ways. In general, this volume’s more successful chapters manage to use customary tools constructively by tweaking them adroitly to fit the needs of the repertoire. Others, however, have a tendency to apply existing theoretical concepts uncritically to this new repertoire, sometimes resulting in questionable analytical results.

[0.4] The editors have divided the volume into two parts: “Chapters that Engage Multiple Works” and “Chapters that Engage a Single Work.” In the body of the review to follow, I adhere to that structure, reviewing each chapter in order. I then close by offering thoughts on what the field might learn from the volume’s strengths and weaknesses and where musical theater analysis should head next.

1. CHAPTERS THAT ENGAGE MULTIPLE WORKS

[1.1] Here for the Hearing opens with one of its strongest entries, Nathan Beary Blustein’s “‘Was It Ever Real?’: Tonic Return via Stepwise Modulation in Broadway Songs.” The chapter’s basic premise is quite simple. In most Broadway songs, the final modulation (usually up a half or whole step) is an act of tonal departure that closes the song in a new, higher, more energized key. But some songs traverse circular paths, such that the final upward modulation enacts a tonic return, restoring the original key. Blustein examines a variety of such songs to show how an ascent back to tonic “expands a song’s rhetorical potential” (11).

[1.2] Blustein groups applicable songs into four main categories. One category is “direct modulations to tonic in final choruses” (12). A second is songs that descend by step for the bridge and then ascend by step for the final chorus, but do this via indirect modulations. A third is songs that modulate to tonic somewhere other than the final chorus. (I will address the fourth in paragraph [1.4].) What makes this chapter so effective is that it never becomes a mere catalogue of these songs and their techniques. In his analyses, Blustein not only attends to the unique musical features of each song; he also finds a way to turn their tonal trajectories into metaphors for the characters’ psychology.

[1.3] For example, the three songs he examines for direct modulation are “What a Game” from Ragtime, “The Wizard and I” from Wicked, and “So Much Better” from Legally Blonde. “What a Game” features a double return of theme and key. Blustein suggests that achieving this traditional goal via an unusual modulation shows that the old formal conventions of the rag can be sustained only through new sorts of modulations, the kind of changes that unnerve the character Father. “The Wizard and I” features a thematic return before the tonic return (the chorus starts in B, but is wrenched into C partway through). This extra effort to return the music to C mid-chorus becomes an illustration of Elphaba’s “determination to overcome her obstacles” (12). The final chorus of “So Much Better” begins with a double return but then continues to modulate further. This manic upward modulation reflects Elle’s racing thoughts and “unbounded excitement” (13).

[1.4] The fourth category Blustein considers is songs whose “intensifying direct modulations provide an opportunity for interpretive elements that often lie beyond the purview of composers” (18)—that is, songs whose modulations are best credited to the arranger. Although most of the volume’s other contributors are careful not to ascribe too much to the composer (and thus often resort to speaking only about the musical works’ properties, and not about who created them), Blustein, Drew Nobile, and J. Daniel Jenkins are the only ones who explicitly consider the work of arrangers/orchestrators and actually name some of them: in Blustein’s case, those include arrangers William David Brohn and Alex Lacamoire and orchestrator Stephen Oremus, who worked with Stephen Schwartz on Wicked.

[1.5] With that being said, Blustein doesn’t quite go far enough. He states that in songs without extended breaks, “a majority of the melodic, harmonic, and tonal material most likely originated with the composers” (18). This is not a safe assumption. Some musical theater composers supply basically nothing but the tune.(1) For example, that quotation from Blustein comes directly before he analyzes “’Til Him” from Mel Brooks’s The Producers. Brooks wrote every song in that show (not just the ones with extended breaks) by singing melodies into a tape recorder and having Glen Kelly (whom Blustein does not name) transcribe and arrange them (Brooks 2001). Blustein’s baseline acknowledgment of arrangers is a huge and laudatory step in the right direction, but I wish he had mentioned them more consistently, where they were possibly relevant, and that the editors of the volume had advised the other authors to do the same.

[1.6] One can easily guess the subject of Drew Nobile’s chapter, “Sondheim’s Dissonant Tonality,” from its title. Nobile’s point of departure is Sondheim’s own claim that “harmony is what makes music” while rhythm and melody are “secondary” (36). But, although Steve Swayne (2005) has identified various classical influences on Sondheim’s harmony, no one has really shown how Sondheim regularly draws upon those twentieth-century classical harmonic influences in his compositional practice. Nobile aims to do precisely that, connecting Sondheim to the “contemporary tonal” vocabulary previously explored by Daniel Harrison (2016).

[1.7] Nobile’s chapter divides into separate theoretical and analytical halves. In the former, he identifies some key features of Sondheim’s harmonic style. More specifically, he notes that Sondheim’s melodies tend to be diatonic and his bass lines tend to be functional, just embellishing , , and ; when there are dissonances, they tend to be present in what Nobile calls the “chordal zone” in between the bass and the melody. Four characteristic features of Sondheim’s chordal zones are (a) the use of a “five-note tonic” chord, consisting of , , , , and ; (b) oscillations between and over a tonic pedal; (c) the use of “suspended dominants” that omit the leading tone; and (d) the use of the set class (0148) to derive “colored triads” (Harrison’s term).

[1.8] The analytical half of the chapter begins with a discussion of dissonance in the first act of Sunday in the Park with George, including a harmonic reduction of the title song that highlights appearances of the (0148) sonority. Here, Nobile modifies Stephen Banfield’s suggestion (Banfield 1993) that the act progresses from chromaticism to diatonicism, suggesting instead that the act “[absorbs] [its] signature chromaticism in a diatonic context” (52), to capture dissonance within order rather than erasing it. Nobile’s reading of Into the Woods discusses why so many tonic chords in the musical are thirdless, substituting for throughout most of the show. His proposition is that is added to tonic chords late in the show, at the pivotal moments at which characters learn communal responsibility.

[1.9] These analyses are lucid and helpful. Their only drawback is that they isolate harmony from lyrical content and form. But that is a product of their deliberately limited scope. A logical next step for future analyses would be to consider all of these musical parameters in tandem. When that happens, the theoretical foundation Nobile has provided will be indispensable.

[1.10] In contrast to the two chapters preceding it, which discuss phenomena particular to musicals, Gregory J. Decker’s chapter, “Topical Interpretive Strategies in American Musical Theater: Three Brief Case Studies,” operates squarely within the field of mainstream topic theory. Decker makes a good case for how musical-theater scholars can use topic theory for more than just labeling everything within sight, and how topic theorists can see musical theater as more than yet another genre to conquer.

[1.11] The first of Decker’s two title strategies is to use topics to generalize characters. Decker illustrates this strategy with The Secret Garden, whose music is filled with markers of social class (e.g. folk music, contredanses, and nursery rhymes for the lower class, and a more contemporary Broadway style for the upper class). Decker suggests that we, as listeners, first use these markers to divide the characters by class, and eventually come to correlate class with the characters’ emotional temperaments, when the upper-class characters are revealed to be emotionally closed while the lower-class ones are emotionally open.

[1.12] By contrast, the waltz topic in Sweeney Todd is an illustration of the opposite strategy: particularizing (rather than generalizing) characters by portraying their varying relationships to the genre. The music-hall-style “Bowery waltz” topic in “A Little Priest” is a channel for Sweeney Todd’s class anger on the one hand and Mrs. Lovett’s class aspirations on the other hand. The troping of waltz and ombra in “Johanna” depicts the conflict between Judge Turpin’s socially respectable public life and his foul private life.

[1.13] According to Decker, The Fantasticks occupies something of a middle ground between The Secret Garden and Sweeney Todd. Like the former, it separates groups of characters by style: contemporary musical theater for Matt and Luisa, vaudeville for their parents, and various “exotic” styles for El Gallo. Yet additionally, within a single topic (the waltz once again), it allows for particularization. In the opening number, “Try to Remember,” “the waltz serves as a signal for nostalgia” (80), its circularity keeping listeners rooted in the past. This nostalgia may seem innocent but is turned into something grotesque in “Round and Round,” in which the circularity becoming a source of exhaustion and preventing the progress of love. The waltz becomes a vehicle for real love only in “They Were You,” when all circularity is shed.

[1.14] Some of the details in Decker’s harmonic and stylistic analysis of The Fantasticks strike me as dubious. Decker identifies “It Depends on What You Pay” as a bossa nova (80), despite the fact that it includes the double-harmonic scale, flamenco-style stomps and claps, and a son clave rhythmic pattern, and is sung by a character with a Spanish rather than Portuguese/Brazilian name. Later, he lists the main progression of “Try to Remember” as I–I6–IV5–6–V7. (Even if one thinks the chord is IV and not first-inversion ii, it should be IV6–5.) Then, he omits all of the sevenths from his Roman-numeral analysis of the descending fifths sequence, even though they could play an interesting role in his reading of this passage as perpetuating a sense of circularity. Despite these quibbles, I think his treatment of its waltzes delivers genuine insights, ones that would not have been as clear without the background of his preceding readings of The Secret Garden and Sweeney Todd. I can imagine this chapter being of use to scholars of many media beyond music theater, as the mixing of generalizing and particularizing strategies could operate just as easily in film, opera, or myriad other genres.

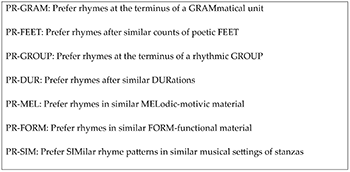

Example 1. Plotkin’s preference rules for rhyme

(click to enlarge)

[1.15] Richard Plotkin’s chapter “A Phenomenological Approach to Music Theater Rhyme” describes the most general phenomenon over the widest swath of repertoire in the volume, and thus ranks as its most ambitious contribution. Plotkin aims to show how “rhyme creates expectations for resolution,” demonstrating “[t]he way those expectations are created, and the myriad ways in which they are satisfied, denied, and often toyed with” (91). To this end, he constructs a series of “preference rules” that are meant to “describe different situations in which we either expect or prefer to hear rhyme” (96); these rules are collected in Example 1.

[1.16] Unfortunately, there are problems with this ruleset that prevent it from being usable in its current form. The phrase “expect or prefer” already hints at some of these problems. What could Plotkin mean by “expectation” and “preference” such that they are interchangeable enough to be governed by the same rules? This is unclear, because Plotkin doesn’t engage with (or cite) any prior literature on these concepts, not even the work of Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff (1983), with whom the term “preference rule” is virtually synonymous in music theory.(2) For Lerdahl and Jackendoff, preference rules kick in when there are multiple grammatically well-formed ways to parse a passage of music: they explain which readings a listener is more likely to select. For Plotkin, the preferences seem to be about aesthetic pleasure: they explain which rhyme schemes a listener is more likely to enjoy. Evidence that this is what Plotkin means appears when he rewrites the lyrics to “Tonight” from West Side Story in ways that violate the preference rules and seem less satisfying (101–2). These particular examples are well-executed and convincing.

[1.17] This does not generalize, however. Violation of expectation is not inherently unpleasurable; in fact, it can be the source of the greatest pleasure under certain circumstances. This is a central premise of most theories of musical expectation, particularly that of Leonard Meyer (1956; 1957). Plotkin seems to acknowledge this in his description of denying and toying with expectations. But his system cannot accommodate this kind of enjoyment because it portrays listeners as always preferring to predict correctly. For delight in surprises to occur, expectation rules and preference rules can have some overlap, but cannot be identical.

[1.18] Additionally, there are issues with at least three of the individual rules. First, the concept of “poetic feet” is irrelevant to most musical theater styles, which makes PR-FEET a questionable assumption.(3) Second, PR-DUR comes into such frequent conflict with PR-MEL and PR-FORM that one might wonder why it exists as a rule at all. PR-DUR entails a baseline assumption that e.g. the fourth bar of an eight-bar phrase will rhyme with the second bar. But eight-bar parallel periods in musical theater songs tend to be rhymed abab. Unless presentations statistically dominate over antecedents in this repertoire by a significant margin, why should a listener automatically prefer the former? A listener can expect that the second musical idea will conclude with a word that is part of the rhyme scheme, but not more than that. Third, PR-FORM clashes with how sentences are customarily rhymed. Plotkin writes that PR-FORM is satisfied “by rhyming the end of two measures of continuation function with the end of the subsequent two measures of cadential function” or “by rhyming the end of a presentation and the end of the subsequent continuation” (98). But in some musical theater styles, the conclusion of a sentence is as likely (or, in the first half of the 20th century, much more likely) to rhyme with the end of the next sentence, not with its own presentation or with the first half of its continuation.(4)

[1.19] With all this in mind, I would encourage all scholars considering rhyme in this repertoire to read Plotkin’s chapter. At the same time, though, I would not encourage them to adopt his rules without revising them first. In doing so, it might be more profitable for future scholars to construct new rules that incorporate insights from other existing models of expectation, prediction, and/or projection, with Hasty 1997, Huron 2006, Mirka 2009, and Murphy 2022 and 2023 being prime candidates.(5)

[1.20] The first half of the book closes with Rachel Short’s “The Changing Rhythms of Bridges and Ends,” which itself serves as a bridge of sorts to some of the more rhythm-focused work in the book’s second half (such as Rachel Lumsden’s and Robert Komaniecki’s chapters). Short’s chapter is, along with Plotkin’s, one of the most theoretical (rather than analytical) in the book. She looks at ballads from the 1920s to the 2010s “where melodic rhythms deviate significantly from those found elsewhere in the song” (113) and describes four distinct strategies for creating these rhythmically differentiated sections.

[1.21] The first strategy is to vary “rhythmic density,” which Short defines as “how many notes occur proportional to each beat” (115). “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz is an example of a song whose bridge, with its steadily wavering eighth notes, is denser than its slower, dreamier A sections. “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man” from Show Boat and “On the Street Where You Live” from My Fair Lady are examples of songs with denser A sections and more open B sections. The latter exemplifies a “soaring” bridge, whose rhythms are not only more open but also steadier and smoother (117).

[1.22] The second strategy is to vary how phrases begin, the major distinction being between those that begin with a downbeat and those that begin with an anacrusis or with a “loud rest” (a clearly absent downbeat) (119). The third strategy is to vary “rhythmic distribution,” which “describes the location of rhythmic density across longer musical time spans, portraying where in the phrase or motive the density occurs” (123). Short uses the term “front-loaded” for phrases that are dense at the beginning and “back-loaded” for those that are dense at the end. She notes that in AABA song forms and their variants, “the A sections are often more front-loaded, dense, and rhythmically complex. These contrast with central sections that are relatively more open, with rhythmic distribution that is smoothly spaced” (124). She then provides examples from South Pacific, The Fantasticks, and Fiddler on the Roof.

[1.23] The last of the four main strategies is to vary the degree of syncopation. Here, Short focuses on songs that are not in strict AABA forms whose “highly syncopated rhythms in central sections [that] contrast [with] declarative straight rhythms in the culminating sections” (130) symbolize characters progressing from internal conflict to making a decision. The examples in this case are drawn from Avenue Q, In the Heights, and Hamilton.

[1.24] As mentioned at the outset, Short’s emphasis in this chapter is more theoretical—constructing a taxonomy of rhythmic formal processes—than analytical. As such, the songs serve more as examples of the categories than as objects of analytic interest in their own right. That said, the musical examples do a good job of showing how useful the categories are, and Short astutely draws attention to ways that these strategies can manifest and interact. Short’s chapter will hopefully become a standard reference text when we talk about bridges in this repertoire.

2. CHAPTERS THAT ENGAGE A SINGLE WORK

[2.1] The title of Michael Buchler’s chapter, “Three Notions of Long-Range Form in Guys and Dolls,” might set off alarm bells. Isn’t long-range form precisely the kind of classical-only idea that is inapplicable to musical theater? Exhibiting a clear awareness of and sensitivity to this issue, Buchler begins by addressing this skepticism head-on. He quotes two musical theater historians arguing that Guys and Dolls is constructed like a “jigsaw puzzle” (Ewen 1958, 189, quoted on pg. 146) or has “tonal and structural cohesion rare in the annals of American Musical Theatre” (Bordman 2001, 631, quoted on pg. 146). And he suggests that “long-range form” is of a piece with the mid-twentieth-century musical’s undeniable focus on formal integration. In keeping with this premise, Buchler’s “three notions” are not really about what most classical theorists would think of when they hear the word “form.” They are about (a) character development, (b) the placement and disposition of songs overall, and (c) “the placement and meaning of duets” (146) in particular.

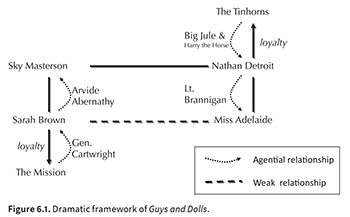

Example 2. Buchler’s dramatic framework for Guys and Dolls, showing character relationships

(click to enlarge)

[2.2] Buchler’s understanding of the show’s character development is best summarized by Example 2 (Figure 6.1 from the volume), which shows the relationships among the characters. Sarah is pulled between love for Sky and her obligations to her mission. Nathan is pulled between promises he made to Adelaide and those he made to his gang of tinhorns. Each of these central characters has two agents that push the conflict toward resolution, represented by dotted arrows. The result is a neatly balanced symmetry.

[2.3] Buchler’s analysis of the associative network formed by the musical’s songs is too complex to be fully explicated here. It includes the varied ways that the tinhorns and the missions draw upon religious musical tropes (with the tinhorns’ being more Catholic/Lutheran); the ways the two groups are symbolized by different keys (with flatter keys reserved for the tinhorns); and the way that the mission starts off singing square rhythms, while the tinhorns sing in a syncopated style, until the two styles blend by the end of the show. This chapter is thus usefully read in tandem with Decker’s and Short’s.

[2.4] For duets, Buchler sets up a distinction between argumentative ones, in which characters trade lyrics (a development he credits to Frank Loesser), and traditional, consecutive ones, in which each character has a verse and a chorus and then the characters unite. As Buchler shows, the original version of Guys and Dolls was intended to have an argumentative duet for Sky and Sarah in Act 1, another for Nathan and Adelaide in Act 2, then more agreeable ones for the men in Act 1 and for the women in Act 2, with one love duet for Sky and Sarah as the keystone to this arch.

[2.5] In his eagerness to draw some of these connections, Buchler fudges a few points. In order to focus on tonic-dominant polarity across songs, he eliminates the ii7 chords from his transcription of “Fugue for Tinhorns” without telling the reader (151–3). To emphasize the continuity between Miss Adelaide’s numbers across the show, Buchler reports that “Sue Me” and “Adelaide’s Lament” are both in 6/8 (161); in actuality, the latter is in 4/4 with running triplets.(6) Nonetheless, Buchler’s chapter works well, due in large part to its eclecticism. Even if one does not accept every individual link he attempts to establish—e.g., how many audience numbers are likely to draw his denominational distinction between religious styles?—one is likely to accept enough of them to add up to a convincing argument. Not to mention that it is rewarding to view a classic musical from so many new angles.

[2.6] If Buchler’s chapter provides a predominantly positive example of how to talk about long-range connections, a less positive model may be found in Nicole Biamonte’s chapter, “Style, Tonality, and Sexuality in The Rocky Horror Show.” Her thesis is that in the musical, “flat keys and softer pop-music styles are loosely correlated with the conservative, heteronormative human characters, and sharp keys and hard-rock styles with the sexually open, queer alien characters” (169). Awareness of this dichotomy, she suggests, can allow us to chart two characters’ dramatic trajectories over the course of the show: “Janet’s sexual awakening is marked by a significant shift sharpward, from the keys of

[2.7] A musical theater fan’s first reaction to these claims should be, “Which production are you talking about?” Biamonte explicitly models her approach on Verdi scholarship, but Verdi operas do not, as a rule, undergo key changes from production to production. Productions of The Rocky Horror Show do, however. Biamonte is clearly aware of discrepancies among versions of the show, mentioning some on pg. 175; nevertheless, she presents her chapter as an analysis of “tonal and sexual relationships in The Rocky Horror Show,” full stop.

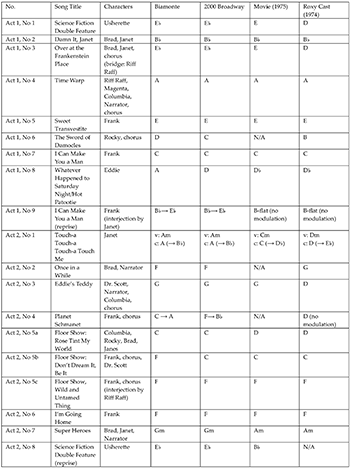

Example 3. Key relationships in The Rocky Horror Show according to Biamonte and in different productions

(click to enlarge)

[2.8] Even at present, I remain unsure which production her analysis is based on. In Example 3, I list the keys she provides and the keys of the four most widely available cast albums. Biamonte’s stated keys most closely match the 2000 revival, fifteen of whose nineteen songs accord with hers. This means that Biamonte’s reading does not work for what are arguably the three most canonical versions of the musical: London, Roxy, and the film. Frank’s trajectory may remain flatward in all of the productions listed in the example, but Janet’s trajectory—which is supposed to provide a vital sharpward contrast—is flatward in the London version (D to

[2.9] Given its stated focus, it is not surprising that Jonathan De Souza’s chapter, “Music, Time, and Memory in Jason Robert Brown’s The Last Five Years,” ended up categorized as one of the “Chapters that Engage a Single Work.” But actually, the chapter’s strongest moments occur when De Souza situates The Last Five Years within the broader context of musical theater’s experiments with chronology.

[2.10] The chapter is flush with literary theory. The term that performs the most labor is Gérard Genette’s (Genette 1980) concept of “anachronies,” which are departures from the first narrative temporal progression. De Souza illustrates four forms of anachrony—external, internal, subjective, and objective—with the narrative structures of Wicked, Hamilton, Fun Home, and Merrily We Roll Along. This section is an enormously helpful introduction to the intersection between narrative theory and practice in the musical. De Souza’s suggestion is that The Last Five Years blends elements of all four of these anachronies, thus altering the implications of a standard musical theater practice: the reprise.

[2.11] In most musicals, reprises are present echoes of past musical material. The “double anachrony” of The Last Five Years, however, creates cases where it is difficult to determine which appearance of the material should count as the original and which as the echo. I must admit that I find it hard to invest in this problem. It is unambiguous which appearance comes first in the sequence of the story (as opposed to the sequence of the show). Given that chronology is not in dispute, the question of whether a certain motivic event should count as “analeptic prolepsis” or “proleptic analepsis” (200), to use De Souza’s framing, seems like a problem created by the application of narrative theory, rather than an extant problem that narrative theory helps us solve.

[2.12] The closing section of the chapter, in which De Souza applies Frederic Jameson’s (1991) definition of “parody” (which is irony-laden, unlike neutralized “pastiche”), departs from the strictly temporal theme of the earlier sections but provides the chapter’s keenest psychological insights. We see how the character Cathy uses genre markers as a coping mechanism and mask for her emotions, and how Jamie’s self-expression becomes more sincere as the musical goes on, as he sheds the genre markers that made his earlier songs parodic. This is a thought-provoking analysis of how style functions in the musical, and it could be assigned fruitfully in a class in combination with Decker’s chapter.

[2.13] Rachel Lumsden’s chapter “Lesbian Desire in Fun Home” sustains the temporal emphasis of De Souza’s chapter. Prior scholars, such as Ann Cvetkovich (2008), have related the narrative structure of Alison Bechdel’s original graphic novel to topical discussions of “queer temporality.” Lumsden extends these ideas through analysis of two songs from Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori’s musical adaptation: “Ring of Keys” and “Changing My Major.”

[2.14] According to Lumsden, in “Ring of Keys,” sentential structures are interrupted and fragmented in ways reminiscent of how queer theory understands ellipses: as punctuation used “to express the unspeakable” (216). The chorus depicts Alison’s confidence through its more regular and tight-knit phrase structure, while a bit of metrical dissonance in the bridge highlights Alison’s outsider status as she sings “Why am I the only one who sees you’re

[2.15] Lumsden’s chapter is, along with Decker’s, one of the essays that would be most at home on a syllabus for an analysis class that does not necessarily have a musical-theater focus. It is a good model of how to draw upon easily audible features of meter, form, and harmony and knit them into an easy-to-appreciate and convincing analysis. If it has any flaws, it is that it assumes that we can treat traditional sentence structures as the “heteronormative” formal model that is being queered, when, in fact, we do not know how much normative power the sentence paradigm retains in 2010s musical theater. If the sentence paradigm has grown much weaker, continuing to hold it up as a model allows us to interpret most phrase structures too readily as acts of queer resistance. Lumsden cannot be faulted for this, however. Her analyses are about as good as is possible to produce given currently available tools. We simply need more tools. I will return to this point in my conclusion to this review.

[2.16] There is wordplay at work in the title of Robert Komaniecki’s chapter, “The Hip-Hop History of Hamilton.” Komaniecki ties Hamilton’s songs to two kinds of history: the American history being portrayed, and the history of the genres of hip-hop and musical theater, to which Lin-Manuel Miranda pays tribute. Few of the musical details Komaniecki mentions will have gone unnoticed by Hamilton enthusiasts, as the musical’s hardcore devotees already have some analytical tendencies. Still, Komaniecki finds rewarding ways to connect these details to things outside of the musical.

[2.17] Komaniecki’s analysis of the show begins with a review of the role of rhythm and meter in the score. He discusses how in “Aaron Burr, Sir,” John Laurens’s use of old-school rap style is meant to contrast with Hamilton’s more forward-thinking style; how Lafayette’s music increases in rhythmic complexity and virtuosity as he gains political acumen; and how the use of 7/8 time in “Meet Me Inside” depicts the characters’ discombobulation after the duel. All of these are useful points, but they are not original to Komaniecki. They are distillations of things Miranda himself has said in Hamilton: The Revolution (Miranda and McCarter 2016), which Komaniecki quotes copiously.

[2.18] Komaniecki’s original contributions appear in a section on rhyme. He notes that Hamilton’s verse in “My Shot” is distinguished not merely by its density, but also by the absence of “a single monosyllabic rhyme [

[2.19] The chapter’s few shortcomings pertain more to presentation than content. Hip-hop scholarship, including some of Komaniecki’s prior work (2017), has tended to be very good at representing rhyme in intuitive and easily legible ways.(7) Of course, a print volume like this does not allow for the resource of color coding. But this does not explain why, for example, Komaniecki includes a lengthy excerpt from “My Shot” with no annotations (e.g., underlining, italics, etc.) to mark the rhymes (243). Komaniecki’s Figure 10.1, showing wordplay in “Farmer Refuted,” gets the job done, but providing a score excerpt showing Hamilton’s line layered over Seabury’s might have made these points more user-friendly. Thus, I could imagine happily teaching this chapter to students, as its points are informative and accessible; but I would probably create some supplemental visuals, if I did so.

[2.20] The volume closes with what, for many readers, will likely be the most unfamiliar material: J. Daniel Jenkins’s chapter, “Isn’t It Queer: The Kinsey Sicks and the Art of Broadway Parody.” The Kinsey Sicks advertise themselves as “America’s Favorite Dragapella Beauty Shop Quartet.” Jenkins aims, first, to present the Kinsey Sicks’ general parody practice; but, then, to explain how their song “Send in the Clones” (a parody of “Send in the Clowns” from A Little Night Music) differs from this general practice, crafting a sharper critique.

[2.21] Two positive elements stand out in Jenkins’s discussion of these matters. One is the way that he surveys The Kinsey Sicks’ shtick for those (like myself) who were entirely unacquainted with them. With a few well-chosen examples that are quickly but clearly explained—and ripe for a bit of Spotify bingeing—he quickly paints a vivid picture of their style. The other is Jenkins’s perceptive account of how the genre of the musical theater song poses special problems for theories of parody. While some musical theater songs have what Kurt Mosser (2008) calls a “base song” (a paradigmatic performance that is the reference point for future covers, parodies, etc.), some do not. They have, instead, a network of possible past referents to draw upon.

[2.22] Jenkins attempts to solve these problems using prototype theory, drawn from Lawrence Zbikowski’s work (2002). This is where things go awry in the chapter. Jenkins writes:

Conceptual models rest on the principle that humans categorize items from most to least typical. Zbikowski calls those items that are “securely inside the category” Type-1 examples, while those that are “in danger of being excluded” are called Type-2. Consider birds as a category: Type-1 examples would include robins and sparrows, while emus and penguins would be Type-2 examples. (257)

This is not how Zbikowski uses those terms, however. Zbikowski’s Type 1 refers to categories that have graded memberships, and Type 2 refers to categories that have necessary and sufficient conditions for membership (2002, 36–41). Thus, emus and penguins are not Type-2 examples, as Jenkins states; rather, they are the least typical members of a Type-1 category (birds). The real issue here is not that the numbering is incorrect; rather, it is that prototype theory is meant to allow one to escape these sorts of crisp categories altogether.

[2.23] To his credit, Jenkins writes, “these types represent opposing poles on a continuum rather than clear points of demarcation” (257). Even so, his actual analysis of “Send in the Clones” refers to various musical performances (or performance elements) as being, simply, Type-1 or Type-2. The binary categories remain operative. This is a pity, because the core of Jenkins’s analysis is intriguing. He makes the case that the Kinsey Sicks replaced Sondheim’s original musical features with ones borrowed from doo-wop, and that doo-wop is meant to represent the dated heteronormative values reinforced by a certain type of gay men (the title “clones”). A more faithful use of prototype theory—one that tracks the ebb and flow of prototypical elements across the song as a means of establishing a changing relationship with our conceptual models of the song—could have served this reading quite well.

CONCLUSION

[3.1] The highs of this collection show how much rich hermeneutics can be wrung from musical theater. The lows do nothing to suggest the unfitness of this repertoire for thoughtful analysis. If anything, they show all the lingering challenges that this repertoire presents—challenges we should be excited to meet. I would like to close by suggesting four things we can do to help us along this path.

[3.2] Escape the classical work concept. Biamonte’s chapter provides a useful cautionary tale about what can go wrong if we heedlessly treat musicals as if they were operas, where most of the parameters are fixed by the text of the original production.(8) Although I closed my review of Jenkins’s chapter by criticizing his application of prototype theory, I think he had fundamentally the right idea in choosing it in the first place. For while there are some cases where all productions of a musical refer back to the original, there are many others where there are multiple competing versions that are canonically enshrined, with no one version epitomizing “the musical itself,” so to speak. Treating such musicals as conceptual models that integrate individual features found across productions is a handy solution.(9) It allows us to view the discrepancies as opportunities for comparison and interpretation, not as sources of embarrassment that we must evade.

[3.3] Escape the classical composer concept. In [1.5], I noted that many chapters wisely avoid crediting all musical decisions to the composer. However, in talking about just the score instead, they erase the labor and agency of the arrangers and orchestrators in creating the musical text. It would be overly burdensome to demand that theorists go hunting in archives every time they want to write about a show, to figure out who did what. But for cases where there is already some documentation of these facts, they should be acknowledged. And in cases where we remain unsure, mentioning the other hands that played a role (however fuzzy that role might be) would allow those forgotten contributors to be remembered.

[3.4] Be prepared to abandon parts of Caplin’s Classical Formenlehre. All thoughtful readings of individual works consider their dialogue with norms. Blustein, De Souza, and Short do a particularly good job of establishing what some of these norms are. They are able to do this because they can derive the norms by looking only at musicals. But the works of authors like Lumsden and Plotkin have to rely on existing theories of form, which derive largely from repertoire outside of musical theater. While there has been some work on form in musical theater, including Callahan 2013, Lawrence 2024, Tawa 1990, and Wood 2000, none of these advances beyond the mid-twentieth century. If we want to write about the kind of contemporary musicals this volume already addresses, we should be prepared to encounter different norms, and we should be willing to learn from works on form in rock and pop music, such as Attas 2011, Nobile 2020, Stoia 2021.

[3.5] Remember that musical theater is a genre, not a style. Most of the chapters in this volume already handle this issue well; some of them, indeed, focus on the mixture of styles. Still, it is worth emphasizing (as a follow-up to my previous point) that genres are constituted of varied styles, lest we take the insights we glean from one musical and leap to apply them to another. Once we move beyond generalities, it will become difficult to continue articulating rules (of most of the topics of this volume, such as form, harmony, rhyme, rhythm, etc.) that govern across all or most musicals. The conventions of one style do not necessarily carry over.

[3.6] Hopefully, some of these agenda items will be addressed by future volumes. In the meantime, scholars, teachers, and readers interested in studying the music in musical theater will find a useful starting point here, in Here for the Hearing.

John Y. Lawrence

University of Chicago

jylawrence@uchicago.edu

Works Cited

Adams, Kyle. 2009. “On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music.” Music Theory Online 15 (5). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.15.5.1.

Attas, Robin. 2011. “Sarah Setting the Terms: Defining Phrase in Popular Music.” Music Theory Online 17 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.17.3.7.

Banfield, Stephen. 1993. Sondheim’s Broadway Musicals. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bordman, Gerald Martin. 2001. American Musical Theatre: A Chronicle. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press.

Brooks, Mel. 2001. “Springtime for the Music Man in Me.” The New York Times, April 15, 2001. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/15/theater/springtime-for-the-music-man-in-me.html.

Brower, Candace. 1993. “Memory and the Perception of Rhythm.” Music Theory Spectrum 15 (1): 19–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/745907

Callahan, Michael. 2013. “Sentential Lyric-Types in the Great American Songbook.” Music Theory Online 19 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.19.3.2.

Cvetkovich, Ann. 2008. “Drawing the Archive in Alison Bechdel’s ‘Fun Home.’” Women’s Studies Quarterly 36 (1/2): 111–28. https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.0.0037.

Ewen, David. 1958. Complete Book of the American Musical Theater. Holt.

Furia, Philip and Laurie J. Patterson. 2022. The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America’s Great Lyricists. Oxford University Press.

Genette, Gérard. 1980. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. Translated by Jane E. Lewin. Cornell University Press.

Harrison, Daniel. 2016. Pieces of Tradition: An Analysis of Contemporary Tonal Music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190244460.001.0001.

Hasty, Christopher. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. Oxford University Press.

Huron, David Brian. 2006. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6575.001.0001.

Jameson, Frederic. 1991. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Komaniecki, Robert. 2017. “Analyzing Collaborative Flow in Rap Music.” Music Theory Online 23 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.23.4.8.

Lawrence, John Y. 2020. “Toward a Predictive Theory of Theme Types.” Journal of Music Theory 64 (1): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-8033408.

—————. 2024. “Lyricist as Analyst: Rhyme Scheme as Music-Setting in the Great American Songbook.” Music Theory Spectrum 46 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtad015.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray S. Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. The MIT Press.

Meyer, Leonard B. 1956. Emotion and Meaning in Music. University of Chicago Press.

—————. 1957. “Meaning in Music and Information Theory.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 15 (4): 412–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/427154.

Miranda, Lin Manuel, and Jeremy McCarter. 2016. Hamilton: The Revolution. Grand Central Publishing.

Mirka, Danuta. 2009. Metric Manipulations in Haydn and Mozart: Chamber Music for Strings, 1787–1791. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195384925.001.0001.

Mosser, Kurt. 2008. “‘Cover Songs’: Ambiguity, Multivalence, Polysemy.” Popular Musicology Online 2. Accessed on June 11, 2024. http://www.popular-musicology-online.com/issues/02/mosser.html.

Murphy, Nancy. 2022. “The Times Are A-Changin’: Metric Flexibility and Text Expression in 1960s and 1970s Singer-Songwriter Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (1): 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtab017.

—————. 2023. Times A-Changin: Flexible Meter as Self-Expression in Singer-Songwriter Music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197635216.001.0001

Nobile, Drew. 2020. Form as Harmony in Rock Music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190948351.001.0001.

Stoia, Nicholas. 2021. Sweet Thing: The History and Musical Structure of a Shared American Vernacular Form. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190881979.001.0001

Suskin, Stephen. 2009. The Sound of Broadway Music. Oxford University Press.

Swayne, Steve. 2005. How Sondheim Found His Sound. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.99247.

Tawa, Nicholas E. 1990. The Way to Tin Pan Alley: American Popular Song, 1866–1910. MacMillan.

Tsur, Reuven. 1996. “Rhyme and Cognitive Poetics.” Poetics Today 17 (1): 55–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1773252.

Wood, Graham. 2000. “The Development of Song Forms in the Broadway and Hollywood Musicals of Richard Rodgers. 1919–1943.” PhD diss., University of Minnesota.

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. 2002. Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195140231.001.0001

Footnotes

1. Suskin 2009, 182–202 is essential reading on this issue.

Return to text

2. He says that his preference rules are inspired by Candace Brower (1993) and Reuven Tsur (1996), neither of whom actually uses the term “preference rules.”

Return to text

3. Indeed, the abandonment of poetic meter is considered one of the watershed developments of musical theater in the early 20th century. See Philip Furia and Laurie J. Patterson’s discussion of lyrics as “The Tinpantithesis of Poetry” (2022, 1–20).

Return to text

4. See Callahan 2013 and Lawrence 2024 for contrasting examples of possible sentential rhyme schemes.

Return to text

5. Lawrence 2020 and 2024 may also have utility, but I admit that the latter might not apply as well to musicals written post-1970 or so.

Return to text

6. There is one other error that is not in support of any particular point: Buchler states that the “reciting tones” of “The Oldest Established” are

Return to text

7. Adams 2009 is another example of doing this well.

Return to text

8. To be clear, there are some musicals where this approach would be more workable. For example, the original production of My Fair Lady and the four subsequent Broadway revivals (1976, 1981, 1993, and 2018) have all used the same vocal arrangements and orchestrations. It is therefore a relatively stable text. (At least, musically. Not all five versions keep the same ending!) Most other shows from its era are not.

Return to text

9. What Zbikowski does with the song “I Got Rhythm” (2002, 204–23) is a great example of what could be done not merely to individual songs from musicals, but also to musicals as a whole.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Aidan Brych, Editorial Assisstant

Number of visits:

2768