“Feel the Emptiness”: Micro-Schemata in the Music of Henryk Mikołaj Górecki*

Evan Martschenko

KEYWORDS: Henryk Mikołaj Górecki, schema theory, micro-schemata, corpus studies, holy minimalism, Polish music, twentieth-century music

ABSTRACT: When filming a documentary about his Third Symphony, Henryk Mikołaj Górecki insisted on filming on the grounds of Auschwitz concentration camp, saying “To understand me and my symphony, we must go there

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.2

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[0.1] Henryk Mikołaj Górecki’s music shares a few key threads, despite the composer writing over a six-decade period and in styles ranging from Polish sonorism to repetitive tonality. These threads contribute to Górecki’s distinct compositional voice.(1) Adrian Thomas (1997b)> outlines three main strands in Górecki’s music that define this compositional voice: folk song influences, iconographic citations, and dynamic/expressive extremes. While Górecki’s music certainly does employ these characteristics, and Thomas provides sufficient evidence for each, they are far from unique to Górecki. With these accurate-but-broad generalizations, Górecki’s compositional voice as it pertains to his entire career, not just a few pieces, remains undefined. For a composer versed in such a wide range of compositional styles, the ability to trace what is consistent across highly varied music proves to be an interesting theoretical issue.

[0.2] In Music and Memory, Bob Snyder proposes that schemas “serve as frameworks for memory, increase chunkability, and help us form representations in long-term memory” (2001, 101). According to Gjerdingen’s seminal book Music in the Galant Style, a schema can be described as a “stock musical phrase” used by the galant-style composers in their music as building blocks (2007, 6). To apply the larger picture of Snyder and Gjerdingen’s work to Górecki’s music, some specific adjustments are necessary. Given the generally sparse textures of Górecki’s music (not to mention a frequent lack of tonal center), schemata cannot be identified in Górecki’s music using the same musical features as in galant music. Additionally, Gjerdingen’s schemata are “event schemata,” which have “determinable beginning and ending points” (1988, 61), but the intense repetitiveness of Górecki’s music does not allow for the consistent definition of such temporal designations. Instead, I define micro-schemata as distinct but flexible stock musical concepts that recur as basic particles of Górecki’s music. A micro-schema does not have to be an event schema. The word “concept” is chosen to encompass musical features as small and varied as three-note motives, specific harmonies, or particular voicings, all of which are “micro” characteristics for many works but assume larger roles in the empty and repetitive soundscapes of Górecki. In the examination of micro-schemata, this article argues that Górecki’s compositional style remained consistent in a few small facets across his career. Similarities between the early serialism and the late tonal works can be found when examining these micro-schemata. These few key threads define the “Górecki sound” in precise terms and outline how the composer’s style revolved around these commonalities.(2)

[0.3] It is natural to view works by a sole composer in a chronology, and Górecki’s music can be neatly placed in three chronological categories: the “geometric period”(as termed by Danuta Mirka, 2004), romantic modality, and sparse tonality.(3) True to his Polish experimental roots, Górecki’s early works use serialism (as in the First Symphony [1959] and Scontri [1960]), Polish sonorism (Genesis [1962–63]), and reductive constructivism (Old Polish Music [1969]). Despite these varied compositional techniques, Mirka has shown that this period shares a consistent interest in musical geometry, involving physical organization of performance space, geometrical aspects of the printed score itself, and various musical representations of geometry (2004).(4) Maintaining the large orchestral sound of the early works, Górecki’s middle period instead takes on a lush, romantic character, as in the Second Symphony (1972), the Third Symphony (1976), and Beatus Vir (1979). Lastly, Górecki’s later works evoke the stereotypical “holy minimalist” sound, moving further still from his avant-garde roots, and acquiring a deep sense of emptiness and sparsity, as in Totus Tuus (1987), Good Night (1990), and a large amount of chamber music (art song, string quartets, and other small ensembles). Spanning these divergent styles, micro-schemata can serve as the grounding, invariant factor from which we hear Górecki’s music in a holistic, yet musically specific sense.

[0.4] Górecki has consistently been labeled a “holy minimalist,” alongside Arvo Pärt and John Tavener (Fisk 1994; Teachout 1995; Rutherford-Johnson 2017). This term describes music with a certain simplicity reminiscent of spiritual or religious works.(5) Some have taken issue with this genre labeling; Tim Rutherford-Johnson (2017, 25) describes the term as a “critic’s invention” and a “branding convenience.” Kerry O’Brien and William Robin (2023, 307) point out that unlike the American minimalists, the “holy minimalists” did not know each other until record labels brought them together. The Third Symphony (1976), Three Pieces in Olden Style (1963), Miserere (1981), and Totus Tuus (1987) are among record labels’ favorite Górecki works because of their marketability as “holy minimalism,” though only a handful of other works by Górecki—if any—fit neatly into this commercial category. Album cover photos also impose a spiritual or Holocaust-oriented view of Górecki’s music, even if the music is entirely unrelated to the topic implied. While examining the micro-schemata in Górecki’s music, we find that the select few works characterized as “holy minimalist” are not in a category of their own, but rather function under the same basic parameters and are in dialogue with the rest of Górecki’s compositions.

1. Background

[1.1] Górecki’s life and career has been outlined in scholarly literature with great detail. Adrian Thomas’s Górecki (1997a) sets the cultural, societal, and personal stage for Górecki’s compositions. Thomas explains the ramifications of Górecki’s youthful fascination with Chopin and Beethoven, his largely self-taught keyboard and composition skills, frequent rejection from music schools, and, perhaps most importantly, the death of his mother was only two years old.(6) The history of Górecki’s most famous work, the Third Symphony, has been described in depth by Luke Howard in several publications (1998, 2003, 2007). Maria Cizmic (2012, 97–166) has discussed trauma and mourning in Górecki’s Third Symphony, asking whether the piece portrays a universal or a localized experience of grief. These historical considerations are key to understanding the progression of Górecki’s style from one of the Polish experimentalists to the purported “holy minimalism.”

[1.2] Thomas (1997b) describes three main strands key to Górecki’s music. The first of Thomas’s strands is the influence of folk song in Górecki’s music. The opening double bass lament from the Third Symphony, for example, has been traced to the Lenten Beggar’s song “Lo, Jesus is Dying” and the hymn “Let Him be Praised” (Thomas 1997b, 84–85). Folk melodies can also be heard in many of Górecki’s art songs, and in his motto motif, which I will discuss later. The next strand is Górecki’s iconographic citations and quotations, founded in his study of Romantic composers. The opening of the Third Symphony’s third movement features an oscillation between the first two chords of Chopin’s Mazurka in A minor, op. 17, no. 4,(7) and a few bars later a lone

[1.3] These concepts are undoubtedly relevant to Górecki, but these same three strands can be found in the music of a great many composers. Bartók is famous for his use of folk song, polystylists and composers of collage music inherently pull from outside sources and historical references, and countless composers have been noted for extremes in their music (see Galina Ustvolskaya’s sonatas for piano, where a dynamic marking below fortissimo is a rarity [Cizmic 2012, 67–96]). Because of the non-specificity of these strands, it would be easy to apply the three strands to most composers of the twentieth century, or to even older composers. But in addition to noting these familiar attributes, the examination of specific patterns, even if they are quite small, will elucidate the characteristic aspects of Górecki’s music.

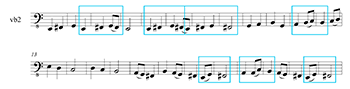

Example 1. Górecki, Symphony no. 3, mvmt. I, op. 36, mm. 25–39, double-bass duet

(click to enlarge and listen)

[1.4] For instance, roughly twenty-five minutes of the first movement of the Third Symphony (a half-hour movement) is based on one repeated melody. While this feature has contributed to many harsh critiques of the symphony, it shows Górecki’s inclination to manipulate small musical details.(9) The string section is split into ten parts, and starting with the second double basses, the long, slow, completely diatonic melody is played in its entirety. After each subsequent repeat, the next-lowest section plays the melody transposed up a diatonic fifth and offset by one measure (see Example 1). Cizmic talks about the experience of hearing the resulting counterpoint (2012, 144); when the second double basses reach the climax of their melody (m. 37, climaxes shown by red carets), the first double basses are about to reach theirs. The melody unfolds in such a way that the second-double-bass climax produces a vertical major second with the first double bass, a tight, cramped interval, whereas the first-double-bass climax (m. 38) produces a vertical major seventh, a larger but still harsh dissonance. Similar relationships occur at each line’s climax, compounding with each instrument, forcing the listener to hear the melodic climax many times in a row as if the grief is inescapable, always increasing in intensity with each new instrument. Expanding on Cizmic’s analysis, I would add that the climax is not the only moment that a listener is forced to hear many times in a row. Many phrases in the melody end on scale-degree 2 of the local key (circled in green), which may resonate with a listener each time an instrument reaches that moment; the seventeenth bar (relative to the starting point of the melody) is a unique rhythmic event, the only time eighth-eighth-quarter occurs (shown in blue boxes), and it therefore stands out when played in turn by each instrument; and the sequential ascent to the climax will also be heard over and over (orange slurs). The feeling of unending grief is composed into every measure of the melody, made evident by numerous small and simple musical materials, such as the scale degree on which a phrase ends or one moment of rhythmic variation. Similar “micro” materials will be examined throughout this article to highlight the manipulation of such aspects in Górecki’s music.

[1.5] When asked by Tony Palmer to film a documentary about the Third Symphony,(10) Górecki insisted that it be filmed on the grounds of Auschwitz concentration camp. He said, “to understand me and my symphony we must go there [Auschwitz],” later reminding Palmer that his symphony is “not about Auschwitz. Nor is it about the terrible regime the Poles suffered after the war under Stalin. It is not even about the struggles of Solidarity

[1.6] The discussion of Górecki’s micro-schemata can help musically define the “emptiness” that Górecki composes into his scores. I will introduce each micro-schema in turn alongside characteristic examples from all three of Górecki’s stylistic periods, showing a progression from geometric experimentalism to romantic modality to tonal sparsity, and showing greater similarity between highly varied works. Noticing the small patterns in such empty environments is not difficult, and they clarify the evolution of Górecki’s music: in this light, there are not large shifts in style, but pivots that hold onto these micro-schemata as grounding support.

2. Micro-Schemata

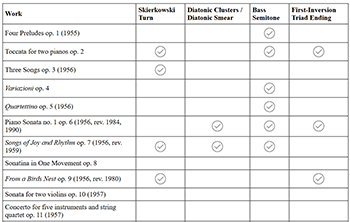

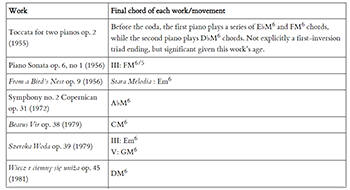

Example 2. Górecki’s list of works, their inclusion or exclusion from the corpus, and the micro-schemata found in each work

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.1] Micro-schemata are defined as stock musical concepts, recurring musical patterns that exist below the level of the melodic idea or subphrase—a voicing, a specific harmony, a three-note motive, etc.—that have particular significance in Górecki’s music. From the corpus study involved in this research, I define four distinct but flexible micro-schemata: the Skierkowski turn, the diatonic cluster (and a subcategory, the diatonic smear), the bass semitone, and the first-inversion-triad ending.(11) I found that 85.2% of Górecki’s works with available scores—including all major works—use at least one of these specific micro-schemata. Eighty-one of Górecki’s 88 works have available scores, and of those 81 only 12 do not use any of the four micro-schemata presented (though some of those 12 use less-common micro-schemata; see note 11). The seven works left out of the corpus do not have readily available scores.(12) See Example 2 for the data collected in this study. (All data were collected without computer-assisted analysis.) A checkmark in the micro-schemata columns shows that the work includes that micro-schema at least once, a blank row indicates the work does not include that specific micro-schemata, and blacked-out rows do not have available scores.

[2.2] The Skierkowski turn is a long-established staple of Górecki’s style, coined by Thomas (1997a, 84–85). Named after a collector of Polish folk songs, Władysław Skierkowski, the Skierkowski turn is an ascending minor third followed by a descending semitone (E-G-

Example 3. Górecki, Old Polish Music op. 24 (1967), reh. 25: Skierkowski turn micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 4. Górecki, Symphony no. 3, mvmt. I, op. 36 (1976), mm. 1–24: Skierkowski turn micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 5. Górecki, Symphony no. 3, mvmt. I, op. 36 (1976), mm. 367–70: Skierkowski turn micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

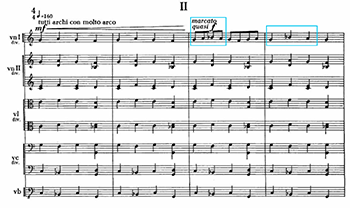

Example 6. Górecki, . . . songs are sung, mvmt. II, op. 67 (1995/rev. 2005), mm. 1–4: Skierkowski turn micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.3] Examples 3–6 show three different pieces that feature the Skierkowski turn, from 1967, 1976, and 1995 (revised in 2005). Example 3, from Old Polish Music, shows violins and violas sharing an extremely slow and quiet duet, a moment that stands out in the otherwise brass-dominated work. The Skierkowski turn occurs in the violin section,

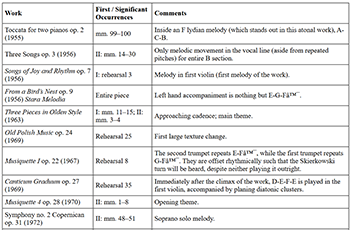

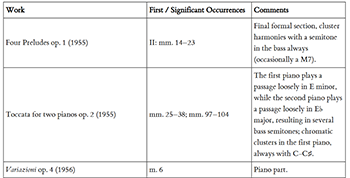

[2.4] Example 7 provides a catalog of pieces that use the Skierkowski turn.(16) Only initial or significant occurrences of the Skierkowski turn are shown in Example 7. If the data collected in this research aimed to number every individual instance of a Skierkowski turn in each piece by Górecki, the total would easily reach the thousands (in some cases, such a statistic is useful; see below, [2.7], and [3.1]). In many instances from Example 7, the Skierkowski turn is not just a significant part of the melody, but the only melodic material of a theme; it is even relatively common for the Skierkowski turn to be the only melodic material used in an entire piece, with only slight development. Example 8 presents the main theme of Three Pieces in Olden Style mvmt. II (1963). In the first four bars, the Skierkowski turn is heard twice, and the theme is repeated so many times that the two-minute movement has around 40 Skierkowski turns in just the first violin part. Whether it be the only event happening on the page (as in Old Polish Music and

Example 7. Skierkowski turn micro-schema catalog (click to enlarge and see the rest) | Example 8. Górecki, Three Pieces in Olden Style, mvmt. II, mm. 1–4: Skierkowski turn micro-schema (click to enlarge and listen) |

[2.5] Górecki has offered some insight into the key threads that run through his music. He says, “in every piece of mine, there is something of the Tatra Mountains,” referring to a mountain range in Poland that was rarely far from where he lived (Rockwell 1993, 136). He continues, “I need them like a fish needs water, like a man needs air. The folk music is still alive, right up to today. It’s not just in my ear, it’s in my blood.” As Thomas correctly points out (1997b), the influence of folk music on Górecki’s compositions is undoubtedly strong, and the same is evidenced by the overwhelming use of the Skierkowski turn throughout Górecki’s entire career. From this, it can be said that Górecki’s use of the Skierkowski turn micro-schema is inherently tied to Poland. Following the success of the Third Symphony, Górecki says he had ample opportunity to emmigrate from Poland, but “if everybody moved out of Poland, what would remain? And I have always asked myself whether my music would sound the same without these trees, clouds, houses” (Rockwell 1993, 136).

Example 9. Górecki, Old Polish Music, op. 24 (1967), reh. 95: Diatonic cluster micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 10. Górecki, Symphony no. 3, mvmt. I, op. 36 (1976), mm. 348–57: Diatonic cluster micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

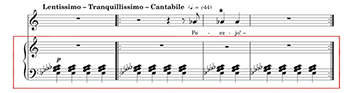

Example 11. Górecki, Three Fragments to Words by Stanisław Wsypiański op. 69, “Poetry! You are a Tranquil Siesta” (1996), mm. 1–4: Diatonic cluster micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

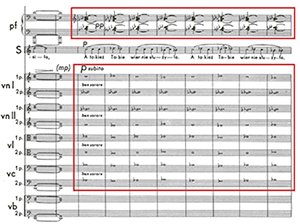

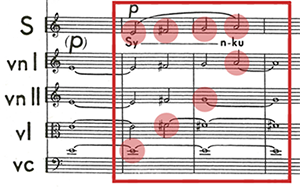

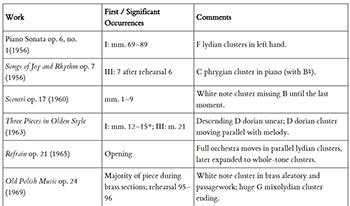

[2.6] A second micro-schema is Górecki’s use of diatonic clusters. These are usually all seven pitches of a diatonic collection presented simultaneously, typically within one octave. Depending on surrounding context or on which pitch is in the bass, these clusters can imply a variety of modes. As Thomas has pointed out (1997b), Górecki prefers Dorian and Aeolian; the data indicate a reliance on the Mixolydian and Phrygian modes (the latter often in conjunction with the bass-semitone micro-schema, see [2.9]). The excerpts shared in Examples 9–11 show the same progression as the excerpts shared in Examples 3–6—geometric experimentalism to romantic modality to tonal sparsity.

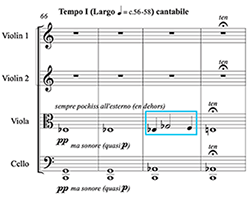

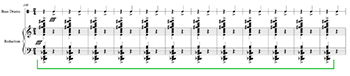

[2.7] Again from Old Polish Music, the notation in Example 9 is one that could be found in many scores of Penderecki, a contemporary of Górecki: a large black bar filling in the staff. Typically, this notation is used to portray a wall of fully chromatic or even microtonal pitches, divided among individual players in a section. However, Górecki has split each string section into eight parts, each part playing a pitch diatonic to G Mixolydian. The full brass section enters not long after, emphasizing the same diatonic cluster (not pictured). Example 10 shows another excerpt from the Third Symphony. Measures 348–57 comprise the only passage of music in the first movement that departs from E centricity. The strings and piano play a full

[2.8] Górecki’s diatonic clusters are often achieved by diatonic smears; multiple instruments move in a scalar direction, one instrument staying behind after each new pitch, resulting eventually in a diatonic cluster. Frequently, Górecki has strings follow a vocal melody, as in the excerpts from the second and third symphonies in Example 12 and Example 13. Diatonic smears can also be used to create a rich texture without tracing a melody, as in the first movement of Three Pieces in Olden Style (Example 14), in Old Polish Music (1967), or in the choral piece Euntes Ibant et Flebant (1972). Notice also that both Example 12 and Example 14 contain a Skierkowski turn in their uppermost voice. Example 15 provides a catalog of diatonic clusters in Górecki’s music, with asterisks by each instance achieved via diatonic smear.

Example 12. Górecki, Symphony no. 2, mvmt. II, op. 31 (1972), mm. 42–50: Diatonic smear micro-schema (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 13. Górecki, Symphony no. 3, mvmt. I, op. 36 (1976), mm. 329–332: Diatonic smear micro-schema (click to enlarge and listen) |

Example 14. Górecki, Three Pieces in Olden Style, mvmt. I, mm. 11–15: Diatonic smear micro-schema (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 15. Diatonic cluster micro-schema catalog (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Example 16. Górecki, Cantata for organ, op. 26 (1968), mm. 109–13: Bass semitone micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 17. Górecki, Beatus Vir, op. 38 (1979), mm. 1–4: Bass semitone micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 18. Górecki, Symphony no. 4, mvmt. IV, op. 85 (2006–2009, posth. 2015), mm. 160–167: Bass semitone micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.9] Rivaled only by the Skierkowski turn, the bass semitone is a noticeably common micro-schema. The bass semitone is a sonority in which the two lowest pitches are a semitone apart. This schema appears frequently in both atonal and tonal contexts (e.g., with a major seventh chord in third inversion). Usually, the bass semitone occurs in a low register (so frequently it might be a schema for the double bass alone), but it does occasionally occur in middle registers when the texture is sparse.

[2.10] Examples 16–18 show the bass semitone in pieces from 1968, 1979, and 2006–9 respectively. In the Cantata for organ (Example 16), low rumblings in 8’ oboe pipes are marked sempre staccato, but in the pedals is a D-

Example 19. Bass semitone micro-schema catalog

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.11] Once again, we can trace the evolution of Górecki’s compositional style with these three examples of the bass semitone micro-schema. In the cantata for organ, the extreme low register encourages the listener to feel the sound, rather than hear it (in its liberation of sound from pitch, this technique is characteristic of Polish experimentalism). In Beatus Vir, the oscillation between two consonant harmonies, C minor and B major, is muddied by one pitch lasting too long in the bass, consistent with the lush orchestral sounds of the romantic middle period. And in the Fourth Symphony, we hear incessant repetitions of a sound that is boisterous, but still the only event on the page (save for the bass drum syncopation), making this section of the symphony intense but sparse. Example 19 lists each piece from the corpus that uses the bass semitone.

Example 20. Górecki, From a Bird’s Nest “Stara Melodia” op. 9 (1956), mm. 15–24: First-inversion-triad ending micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 21. Górecki, Totus Tuus op. 60 (1987), mm. 150–58: First-inversion-triad ending micro-schema

(click to enlarge and listen)

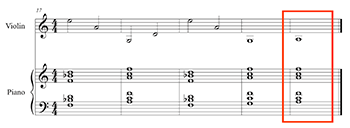

[2.12] A fourth micro-schema is the first-inversion-triad ending. Simply put, a large section, a movement, or a piece ends on a first-inversion triad. These triads are almost always major, and usually they are all “white keys,” such as F major or A minor. While there is no serial or sonoristic piece that includes the first-inversion-triad ending micro schema, it can be found in an early example from 1956. In a collection of piano miniatures (Example 20), likely written for children (Górecki 2021, iv–v), an E-minor melody is accompanied by one pattern in the left hand, E-G-

Example 22. Górecki, For Jasiunia op. 79 (2003), mm. 17–21: First-inversion-triad ending micro-schema (click to enlarge) | Example 23. First-inversion-triad ending micro-schema catalog (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

3. Corpus Examination and Conclusion

Example 24. Timeline charting all four micro-schemata across Górecki’s career

(click to enlarge)

[3.1] Example 24 shows the data collected in this corpus (another representation of Example 2). Each work is counted only once, including multiple movements, so one micro-schema occurring in multiple movements of the same piece is only represented once on the timeline (stacked data points are two or more pieces from the same year). Likewise, a piece is given only one data point regardless of the number of individual instances of a micro-schema (see again [2.4]). The timeline is also split into two halves, secular and sacred, to determine if any micro-schemata correlate with a work’s spirituality. A number of interesting observations can be made. First, the Skierkowski turn and the bass semitone can be found persistently across Górecki’s career with few noticeable gaps. Even in the smaller portion of sacred music, both are found consistently. The diatonic cluster micro-schema becomes increasingly rare as time progresses; perhaps as expected, the early sonorist and experimental works employ clusters, the romantic modal works continue this tradition, and the late sparsity opts for simpler and less brazen harmonic writing (Górecki’s output also slowed at the end of his life). Finally, the first-inversion-triad ending is the least common of all four in Górecki’s secular works but is relatively common in his sacred works. Furthermore, the first-inversion-triad ending is dispersed across the secular music, but unlike any other micro-schema, it appears within a narrow 9-year span within the sacred works (most of these pieces are unaccompanied choral works). The first-inversion triad ending is also the only micro-schema that did not have a representative example from the geometric period. A chord as simple and consonant as this would be rather out of place in a work of Polish experimentalism.

[3.2] Given that Górecki used these micro-schemata across his career, we can modify the perspective put forward during the theoretical discussion. The micro-schemata in this article were examined in a way that showed the progression from geometric experimentalism to romantic modality to sparsity. Instead, let us focus on the micro-schemata, considering them as a grounding, invariant factor in Górecki’s music while the styles in which they are used change. In this sense, the micro-schemata become a metaphor for Górecki’s distinct and discretely consistent compositional voice. The diatonic cluster is a particularly good example in this metaphor, as it was used like a typical sonorist “wall of sound,” then as a deeply romantic (and modally inflected) diatonic dissonance, and finally as a chord to be repeated over two hundred times, becoming white noise or a backdrop for the soprano text. In each of these examples, the diatonic cluster is what remains consistent, and the context it is found in is what changes.

[3.3] As a listener well-acquainted with Górecki’s oeuvre, when I listen to his music I recall how small the micro-schemata appear on the surface, and yet by focusing on the minuscule aspects of the score I am reminded of other instances of the same micro-schema from various points in Górecki’s career. The gigantic diatonic clusters of Old Polish Music are somehow not dissimilar from the piano’s endless repetition of the same sonority in “Poetry! You are a Tranquil Siesta.” Likewise, the somber first-inversion triads of Miserere are related to the same harmony in the bombastic Second Symphony, two works related to Polish history: Polish Solidarity and the story of Nicolaus Copernicus, a crucial Polish figure.

[3.4] Returning to Górecki’s words that to understand his music one must “feel the emptiness,” I have proposed that one can hear the “emptiness” as the communal experience, even trauma, of Polish people in the twentieth century. Musically, a listener may connect the small details that Górecki so frequently manipulates in his music to a feeling of emptiness. Just as the continually repeating lament at the beginning of the Third Symphony compounds upon itself, portraying a feeling of unending grief (see again [1.4]), the statistically overwhelming use of the four micro-schemata outlined in this article can similarly manipulate emptiness. Regular repetition of a musical idea as seemingly insignificant as a three-note motive is, in fact, the kind of expression that Górecki’s sparse and repetitive compositions make space for. The consistency of the micro-schemata is something that can grant Górecki’s music expressive license and can make such repetitive music appear to continually reinvent itself. The manipulation of small musical materials is, in some ways, a manner of compositionally feeling the emptiness.

[3.5] The micro-schemata in this paper are, as far as I can tell, unique to Górecki and tailored to his specific compositional style. The term “micro-schemata”reflects Górecki’s music and its sparsity, but the method of finding compositional consistencies and considering them an invariant principle is not necessarily tied to the study of Górecki. By means of conclusion, I offer a few ways in which micro-schemata can be applied largely to schematic theories of compositional organization, particularly for twentieth-century composers, or otherwise further refined. First, while Górecki is notably consistent, many composers are not as dedicated to a similar manner of repetition. Micro-schemata can still be clearly defined while maintaining flexibility—Górecki’s music simply requires no special exceptions. Another composer’s compositional signatures can still be easily recognizable despite small differences. Second, while the data collected in this study did not account for the exact number of times a micro-schema occurred in a given piece, such an analysis could bring out interesting aspects of minimalism or other pattern-based music. Lastly, the consistency of compositional signatures challenges notions of periodicity and genre labeling. Even this article perpetuates a familiar “early-middle-late”division of Górecki; however, it does so in order to reveal that the periods themselves are characterized more by similarites than differences. By finding a composer’s micro-schemata, we are provided a manner in which we can listen to a composer whose compositional style evolved through a plethora of contexts and associations but maintained a distinct musical voice, allowing us to pinpoint a few methods that define that composer’s sound.

Evan Martschenko

Eastman School of Music

Department of Music Theory

26 Gibbs St

Rochester, NY 14604

emartsch@u.rochester.edu

Works Cited

Belcher, Owen. 2020. “Caroline Shaw’s Musical Portraits.” Theory and Practice 45: 1–50.

Cizmic, Maria. 2012. Performing Pain: Music and Trauma in Eastern Europe. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199734603.001.0001.

Droba, Krzysztof. 1979–97. “Górecki.” In Encyklopedia Muzyczna Polskiego Wydawnictwa Muzycznego, ed. Elżbieta Dziębowska, 5 vols. 3: 420–33.

Fisk, Josiah. 1994. “The New Simplicity: The Music of Górecki, Tavener and Pärt.” Hudson Review 47 (3): 394–412. https://doi.org/10.2307/3851788.

Gershon, Grant, and the Los Angeles Master Chorale. 2012. Górecki – Miserere. Decca, compact disc.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. 1988. A Classic Turn of Phrase: Music and the Psychology of Convention. University of Pennsylvania Press.

—————.2007. Music in the Galant Style. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195313710.001.0001.

Górecki, Henryk Mikołaj. 2013. Symphony No. 4: Tansman Episodes. Preface by Mikołaj Górecki. Boosey and Hawkes.

—————. 2021. Piano Album. Edited by Anna Górecka. Boosey and Hawkes.

Howard, Luke B. 1998. “Motherhood, ‘Billboard,’ and the Holocaust: Perceptions and Receptions of Górecki’s Symphony No. 3.” Musical Quarterly 82 (1): 131–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/mq/82.1.131.

—————. 2003. “Laying the Foundation: The Reception of Górecki’s Third Symphony, 1977–1992.” Polish Music Journal 6 (2).

—————. 2007. “Henryk M. Górecki’s Symphony no. 3 (1976) as a Symbol of Polish Political History.” Polish Review 52 (3): 215–22.

Kholopov, Yuri, and Valeria Tsenova. 1995. Edison Denisov. Translated by Romela Kohanovskaya. Harwood Academic Publishers.

Mirka, Danuta. 2004. “Górecki’s “Musica Geometrica.’” The Musical Quarterly 87 (2): 329–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdh013.

Nelson, John, and the Chicago Symphony Chorus. 1994. Górecki – Miserere. Elektra Nonesuch, compact disc.

O’Brien, Kerry, and William Robin. 2023. On Minimalism: Documenting a Musical Movement. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.455898.

Palmer, Tony. 1993. “The Unknown Hero Who Outsells Madonna.” YOU Magazine, April 4, 1993.

—————. 2014. Gorecki – The Symphony no.3 (The Symphony of Sorrowful Songs by Tony Palmer). BBC documentary, TV movie. YouTube video, 50:34, October 6, 2014. Featuring performance of Henryk Mikołaj Górecki Symphony no. 3. https://youtu.be/mLt9aSWkMRk.

Pärt, Arvo, Henryk Górecki, and John Tavener. 2023. Holy Minimalism – Tavener, Pärt & Górecki. Various performers, compiler unknown. UMG Recordings, Inc. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/album/7Lh6gL6KfjsVyxgqLAKrny?si=IkNSppHOTt2GPjjvpzUZUA.

Piotrowski, Tadeusz. 1998. Poland’s Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. McFarland and Company.

Rockwell, John. 1993. “In East Europe: Minimalism Meets Mysticism.” The New York Times, July 4, 1993, 136–37.

Rotter-Kozera, Violetta. 2012. Please Find – Henryk Mikołaj Górecki. Instytucja Filmowa Silesia Film, TV movie.

Rutherford-Johnson, Tim. 2017. Music After the Fall: Composition and Culture Since 1989. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520283145.001.0001.

Simonov, Yuri, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and Susan Gritton. 2012. Górecki: Symphony No. 3 “Of Sorrowful Songs” (Op. 36)/Three Pieces in Old Style (For Strings). Alto, compact disc.

Snyder, Bob. 2001. Music and Memory: An Introduction. The MIT Press.

Teachout, Terry. 1995. “Holy Minimalism.” Commentary 99 (4): 50.

Thomas, Adrian. 1997a. Górecki: Oxford Studies of Composers. Oxford University Press.

—————. 1997b. “Intense Joy and Profound Rhythm: An Introduction to the Music of Henryk Mikołaj Górecki.” Polish Music Journal 6 (2).

—————. 2005. Polish Music Since Szymanowski. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511482038.

Trochimczyk, Maja. 2003. “Mater Dolorosa and Maternal Love in Górecki’s Music.” Polish Music Journal 6 (2).

Discography

Discography

Archer, Gail. 2022. “Kantata for Organ.” Spotify. Track 7 on Cantius. Meyer Media. https://open.spotify.com/album/7Lh6gL6KfjsVyxgqLAKrny?si=IkNSppHOTt2GPjjvpzUZUA.

Boreyko, Andrey, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. 2015. “Symphony No. 4, Op. 86 Allegro Marcato – Giocosa – Deciso – Marcatissimo ma ben tenuto.” In Henryk Górecki: Symphony No. 4, Op. 85 (Tansman Episodes). Nonesuch Records, compact disc.

Górecka, Anna. 2018. “From a Bird’s Nest, Op. 9a: III. Old Melody.” In Anna Górecka plays Henryk Mikołaj Górecki; Henryk Mikołaj Górecki: Piano Works. CD Ascord, compact disc.

Kronos Quartet. 2007. “II. Largo, Cantabile.” Spotify. Track 2 on Henryk Górecki: String Quartet No. 3 (

Kryger, Urszula, Jadwiga Rappé, Robert Gierlach, and Ewa Guz-Seroka. 2020. “3 Fragments of Stanisław Wyspiański, Op. 69: No. 3, Poetry! You Are a Tranquil Siesta.” In Górecki: Art Songs. Dux Recording Producers, 2 compact discs.

Pál, Tamás, the Fricsay Symphony Orchestra, and the Bartók Chorus. 1993. “Symphony No. 2, Op. 31 ‘Copernican.’” Spotify. Track 2 on Górecki: Symphony No. 2, Op. 31 “Copernican” & Beatus vir, Op. 38. Stradivarius. https://open.spotify.com/album/7Lh6gL6KfjsVyxgqLAKrny?si=IkNSppHOTt2GPjjvpzUZUA

Simonov, Yuri, Susan Gritton, and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. 2012. “Three Pieces in Olden Style (for Strings).” Spotify. Track 5 on Górecki: Symphony No. 3 (of Sorrowful Songs); Three Pieces in Olden Style. Alto. https://open.spotify.com/track/66q2kWfc4zTSLneAUHINrR?si=X1XnyTf1Rdm-waxF4soELQ&context=spotify%3Aalbum%3A4sl1tjzypK75oJrqPk334P

Storojev, Nikita, John Nelson, the Prague Philharmonic Choir, and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. 1993a. “Beatus Vir, Op. 38.” Spotify. Track 3 on Górecki: Beatus Vir/Totus Tuus/Old Polish Music. Argo. https://open.spotify.com/track/66q2kWfc4zTSLneAUHINrR?si=X1XnyTf1Rdm-waxF4soELQ&context=spotify%3Aalbum%3A4sl1tjzypK75oJrqPk334P

—————. 1993b. “Old Polish Music, op. 24.” Spotify. Track 1 on Górecki: Beatus Vir/Totus Tuus/Old Polish Music. Argo. https://open.spotify.com/track/66q2kWfc4zTSLneAUHINrR?si=X1XnyTf1Rdm-waxF4soELQ&context=spotify%3Aalbum%3A4sl1tjzypK75oJrqPk334P

—————. 1993c. “Totus Tuus, Op. 60.” Spotify. Track 2 on Górecki: Beatus Vir/Totus Tuus/Old Polish Music. Argo. https://open.spotify.com/track/66q2kWfc4zTSLneAUHINrR?si=X1XnyTf1Rdm-waxF4soELQ&context=spotify%3Aalbum%3A4sl1tjzypK75oJrqPk334P

Upshaw, Dawn, David Zinman, and the London Sinfonietta. 1992. “Symphony No. 3, Op. 36.” Spotify. In Górecki: Symphony No. 3. Nonesuch Records. https://open.spotify.com/track/66q2kWfc4zTSLneAUHINrR?si=X1XnyTf1Rdm-waxF4soELQ&context=spotify%3Aalbum%3A4sl1tjzypK75oJrqPk334P

Footnotes

* I am grateful for the generosity and thoughtful feedback from Christopher Segall, Catherine Losada, Zachary Bernstein, and the reviewers on earlier drafts of this article. I am also thankful for several suggestions given by attendees of the 2024 meetings of the Society for Music Theory and the Society for Minimalist Music.

Return to text

1. Critic Frank J. Oteri shares the statement below in a Polish documentary about Górecki and his career as a Polish composer:

All of this music across his life connects, but it connects once you really start studying it and seriously listening to it. But a casual listener of the Third Symphony who comes across, say the First Symphony, or comes across the Harpsichord Concerto or Lerchenmusik, these really intense, brooding, manic pieces—they might think it’s the work of a different composer if they’re not really focused on it. They’ll say “well wait a minute! I want more of that beautiful, peaceful, Third Symphony stuff. This isn’t beautiful and peaceful, this is [imitates the Harpsichord Concerto].” But it is coming out of the same place. And if you study the scores and if you look at the scores, you can see the gestures are there. And if you seriously listen to it, you can hear that those gestures are there. (Rotter-Kozera 2012, 28:00–29:11)

Proving that there is something inherently in these scores that ties them to the composer is not the interest of this research, and neither is pointing out the ignorance of a “casual listener.” However, the notion that Górecki’s music shares a few key threads is supported by these statements. In the same documentary, Adrian Thomas shares a similar sentiment.

Henryk Górecki is not just the Third Symphony. Henryk Górecki is much more. And the character of Henryk is the same throughout his career. It is made of granite; it is made of determination; it is truthful; it has got an essence about it which communicates. (Rotter-Kozera 2012, 55:20–56:38)

Return to text

2. Yuri Kholopov and Valeria Tsenova (1995, 40–83) identify many musically specific aspects of Edison Denisov’s music that can be seen throughout his career, largely unchanged for several decades, which they refer to as “genres,” “characters,” and “images.” These include (but are not limited to) “shooting” / “pricking” / sharply rhythmical dots, “dotting” and pointillistic “splashes,” sonoristic mixtures, and sonoristic arrays. These genres-characters are rather similar in design and practice to the use of micro-schemata in this research.

Return to text

3. For information on these stylistic eras and the geometric period (1962–70), see Mirka 2004. The titles “romantic modality” and “sparse tonality” are my own, but the time periods are in line with general groupings of Górecki’s career.

Return to text

4. For further information on the differences between Górecki’s Polish sonorism (1962–63) and his reductive constructivism (1964–70), see Doba 1979–97.

Return to text

5. Many have placed the blanket statement on Górecki as one of the “holy minimalists,” “spiritual minimalists,” or as a practitioner of the “new simplicity” (Teachout 1995, 50; Rutherford-Johnson 2017, 25; Fisk 1994, 394–412). Even in the album art of Górecki records, we see the marketing suggesting a mood for the music that may not be appropriate. Album photos for recordings of Miserere (1981)—a piece written in response to the government‘s assault against the Polish Solidarity Trade Union—show grey, desolate stone buildings, implying a war-torn Poland, and, for those that only know the Third Symphony, might suggest concentration camps and the Holocaust (Nelson and the Chicago Symphony 1994; Gershon and the Los Angeles Master Chorale 2012). Different albums show stained glass windows or an image of a woman praying (Holy Minimalism: Tavener, Pärt, and Górecki 2023; Simonov, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and Gritton 2012a), suggesting that there is a spirituality to the works included; however, the pieces on these albums include Three Pieces in Olden Style, the Third Symphony, Totus Tuus, and O Domina Nostra, of which only the latter two are overtly sacred.

The Third Symphony is intentionally ambiguous regarding its religiosity. The third movement’s text is about a mother losing her son in WWI-era uprisings, and so no religious association is made. The text in the first movement is originally meant to be the words of the Virgin Mary talking to her Son as He dies on the cross, but the words themselves have no mention of Mary or Jesus, just a mother and a son. The second movement’s famous text takes Helena Wanda Błażusiakówna’s words from a Gestapo prison wall inscription, in which she implores “Mamo nie płacz,” followed by a well-known Polish prayer to the Virgin Mary, “Zdrowaś Maryjo, łaski pełna,” the “Hail Mary.” However, mamo is frequently mistranslated as “mother,” when it is more closely related to “mama” or even “mommy,” often used by children talking to their biological mother, not to the holy Mother, where matka would be used instead. Furthermore, the declension mamo, from mama, implies the speaker is addressing their mother; “mama don’t cry.” My thanks to Derek Myler for his help in translating this passage.

Return to text

6. For further information on the death of Górecki’s mother and the effect it had on the composer’s music, see also Trochimczyk 2003.

Return to text

7. This Chopin mazurka was a frequent target for quotation by twentieth- and twenty-first-century composers. In addition to Górecki’s use of this mazurka, Caroline Shaw’s Gustave le Gray (2012) for solo piano is cast in a clear ternary form, with the outer sections being Shaw’s original composition, and the center section being the entirety of Chopin’s mazurka unaltered. For more on Shaw’s piece, see Belcher 2020, 1–50.

Return to text

8. This reference had gone unnoticed until the composer himself pointed it out to Adrian Thomas. Thomas does not provide any description other than “that biting chord which comes halfway through the first movement’s development” (1997b). This chord is most likely the chord heard in mm. 280–84. Both chords, from the third symphony of both Beethoven and Górecki, are identical in pitch structure. Each is spelled A-C-E-F, either an F major seven chord in first inversion, or an A minor chord with an added note.

Return to text

9. Part of the Third Symphony’s mythic appeal was a belief that the symphony was a complete failure until Dawn Upshaw and the London Sinfonietta recorded it in 1992, a record that would go on to sell more than a million copies. However, despite stories of a dramatic premiere heckled by a “prominent French musician,” (presumably Pierre Boulez), Luke Howard has provided a more accurate picture of the symphony’s earlier history, highlighting the symphony’s large success in Poland and parts of Eastern Europe. See Howard 1998, 2003, and 2007.

Return to text

10. See Palmer 2014. See also Cizmic’s discussion of Palmer’s documentary and its problematic and inaccurate portrayal of universal grief (2012, 97–166). Cizmic argues that Palmer likely felt there was a sense of universality to the Third Symphony. For example, Palmer uses images of both the Holocaust and modern-day images of starving African children while the Third Symphony plays in the background. Because Górecki’s symphony is tied so closely to Polish history, a universal understanding of the music may not be appropriate.

Return to text

11. These four are the most prevalent and the most statistically significant, though other micro-schemata occur often. Other micro-schemata include parallel major sevenths (Genesis III: Monodramma op. 19 [1963]), Phrygian twinge at the close of a work (Euntes Ibant et Flebant op. 32 [1972]), additive paragraphs (Third Symphony mvmt. 1; see Thomas 1997) or scale degree 2 melodic ending (Three Fragments to Words by Stanisław Wyspiański op. 69 [1995–96]).

Return to text

12. These seven remaining scores are “unavailable” in the sense that they are non-locatable, are out-of-print and sold-out by publishers, or are too difficult to obtain from the libraries that hold them (several scores are held in the Henryk Mikołaj Górecki Archive in Poland’s National Library, which has scanned and made public many scores and manuscripts).

Return to text

13. Also pointed out by Thomas is the Górecki motto motif, an ascending minor third without the descending semitone. Thomas calls it a “motto” because it is too small to be comfortably labeled a signature motif (1997b). Thomas also claims that Górecki prefers the Skierkowski turn to the motto motif following the Third Symphony, but the data collected in this corpus find this to be largely untrue; the Skierkowski turn can be found as far back as Górecki’s op. 2 in 1955. To illustrate this point, the collected data counts only Skierkowski turns that are given verbatim, a statistic that dwarfs the motto motif on its own. The motto motif may be considered another micro-schema, albeit a less-common relative of the Skierkowski turn.

Return to text

14. A listener may notice that the Skierkowski turn sometimes returns to its starting note (i.e., E-G-

Return to text

15. A proto-Skierkowski turn can be found in the main motivic content of Choros I op. 20 (1964). At some point, each instrument will incessantly repeat the motive of an ascending diminished third followed by a descending semitone. This is also expanded to an ascending major third followed by a descending major second. The same proto-Skierkowski turn can be found in the soprano line of Genesis III: Monodramma op. 19 (1963), rehearsal 11 and similar.

Return to text

16. The second movement of the Third Symphony features the Skierkowski turn with an ascending major third, as opposed to the normative minor third (E-

Return to text

17. Occasionally, the pianist adds a

Return to text

18. The first-inversion-triad ending micro-schema in the First Piano Sonata is the only instance I am aware of in which a first-inversion seventh chord is used at the close of a work. This may be due to the timeline—this is one of Górecki’s earliest works, and only the second piece included in Example 23. While first-inversion-seventh-chord endings are rare in Górecki’s music, first-inversion seventh chords in general are very common. For example, the passage discussed in note 8 is a first-inversion seventh chord (and many others occur in that same movement). The final sonority of the First Piano Sonata is also interesting in that it is one of only a handful of tonally reminiscent chords in the sonata—to end on a consonant harmony is shocking. However, the register and voicing hardly qualifies the chord as “consonant”; the final chord in the First Piano Sonata may be simply a first-inversion F-major chord with E as an added dissonance.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Amy King, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4444