The Origins of Syncopation in Brazilian Music: An Unpublished Manuscript by Mário de Andrade

Enrique Valarelli Menezes and Carlos Eduardo de Barros Moreira Pires

KEYWORDS: Syncope; Mário de Andrade; Brazilian music; Colonization process

ABSTRACT: The present work aims to expose different stages in the development of an unpublished study on syncopation in Brazilian music conducted by Mário de Andrade, a central figure of modernism in Brazil. Initially understood as a rhythmic figure present in various musical practices of the Americas, the concept of syncopation ultimately reveals itself as an interesting analytical tool that is both musical and cultural in a complex context of colonization.

PEER REVIEWER: Cliff Korman

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.18

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

1. Commentary and Translation

[1.1] Mário de Andrade (1893–1945), a key figure in Brazilian modernism,(1) intended, alongside his many activities, to write a book about the origins of syncopation in Brazil. This project was announced in his 1928 Ensaio sobre a música brasileira in a brief suggestion that “syncopation [is] more likely imported from Portugal than from Africa (as I will certainly show in a future book)

[1.2] These manuscripts are intriguing in that they present the writer's efforts toward a more integrated interpretation of music in the Americas, resulting from the complex transcultural exchange on the continent, proposing less superficial concepts to organize the vast amount of data collected by Andrade. His notes, often unpretentious, indicate an examination of the flows, counterflows, and mutual influences among cultures in violent colonial contexts. They also point out continuities, discontinuities, and frictions among the musical cultures of the various peoples involved in the colonial dynamics, in complex processes that are part of the continent's history (Verger 2021; Alencastro 2000; Tsing 2011; Appadurai 1996; Massey 1993).

[1.3] Andrade’s method was to experiment with various approaches, maintaining organized and rigorous note-taking as much as possible. He used pocket notebooks to jot down ideas, thoughts, expressions heard, and other useful information. His practice included highlighting passages of interest in various books and making notes in the margins of the pages during readings, often referring them back to books in his library. This was the method he adopted to organize this planned book on syncopation in Brazilian music. These research materials remained inside an envelope stored among many others in his archive.

[1.4] This slower method of working, with careful notes made over the years, contrasts with his other admittedly urgent method with which he produced many of the essays published during his lifetime. In an essay called “A música no Brasil” (Music in Brazil), Andrade writes that:

African music became immensely enriched here, through contact with Iberian music. In the same way that African-Americans(2) appropriated certain characteristics of English folk music, especially Scottish, so too did this phenomenon occur in South America. The European syncopations, developed by African-Americans, gave us the main source of the prodigious rhythmic richness that manifests in our music. In contact with the European polka, which had great acceptance in the Second Empire, Brazilian blacks, in the same way that the enslaved blacks of the Colony had given us the samba, gave us the maxixe, our main urban dance (Andrade 2013).

[1.5] We will see in his notes, stored inside “Envelope 13 - Syncopation,” carefully curated throughout his life, that this theory of the origin of syncopation will be profoundly reviewed and complicated.

Note #1:

Africa - Portugal - Brazil

Now then, if we lack positive data on formulas and dates, how can we establish priority of creation and imposition in America and Brazil, of certain rhythmic and melodic manifestations that are now definitively ours? Who was the influencer? Who influenced? Or was it just a coincidence of Portuguese and African formulas that contaminated each other and thus gave rise to formulas that, by being born under the auspices of America, we can call American? Even this last hypothesis is not so. Contamination occurred and through it formulas of singing were created that are already specifically American. However, this statement is not enough. The problem of origins remains intricate and without current bases on which it can be resolved (Andrade n.d.).

This note points out some foundational methodological problems and directions in Andrade's approach to music in Brazil and the Americas in general. One of these directions is the sense of the absence of a sufficient corpus of “positive data on formulas and dates” on which the writer could rely to base an affirmative position. Throughout his notes, Andrade specifically exposes the clear need to establish more responsible studies on the traits and characteristics of African and Indigenous musical practices, insisting that the absence of this data would hinder a deeper analysis on “the problem of origins” of syncopation. The data and information gathered in that envelope are an effort in this direction. Andrade’s desired outcome is the possibility of considering how the “rhythmic and melodic manifestations” from different places on the planet may have coincided, converged, and overlapped in the new American context, in blending dynamics where original figures reinforce and repel each other in different directions.

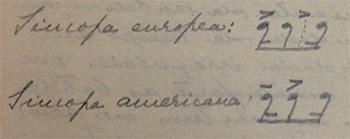

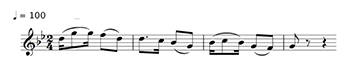

Example 1. Excerpt of Andrade’s (n.d.) original notation

(click to enlarge)

Note #9:

European syncopation seems to me an exclusively musical product, and furthermore, a true theoretical speculation stemming from the subdivision of the time unit into irregular quantities where strong beats persist in their theoretical places and thus become musically elliptical. Now in our American music (jazz, maxixe, and in general all Brazilian syncopation and even in the Argentine tango) what happens is a true displacement of the strong accent which passes from the theoretical place to a place where it should not fall, a true rhythmic anticipation of the thesis (Example 1).

But what makes me assert that European syncopation is a practical speculation of classical music is not only the almost nonexistence of the syncopated movementin European popular music (with the exception of Portuguese and Gypsy (Lavignac 1913)) as it is not common even in the choreographic music of the Western classical tradition. The use of syncopation in Bach, Schumann, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner, etc. etc. is rarely a consequence of physio-choreographic dynamism.

In the vast majority of cases, it occurs within the concept of lied. It is in the song, and mainly in the exclusively instrumental song (which is important for this observation), that syncopations occur. (Study the Flemish and pre-Monteverdian to see the syncopation in them). European syncopation is a practical consequence of the obtuse speculations of the Franco-Flemish and madrigalists. In America, the concept of syncopation arose from another necessity which, although more physiological and popular, could be called more essential. Here, syncopation is of immediate, constant, and directly choreographic application. In America, syncopation does not come from European syncopation. It is an immediate and spontaneous realization of our ways of dancing, more sensual, perhaps stemming from the climate, and the physiological softening of the races that melded to form us and also formed the remeleixo, the requebro, the dengue.(3) It is the languid body movement in dance that deformed the rhythm of the polka

first into the rhythm of the habanera

and then into that

of the maxixe. Furthermore, in habaneras and danzones, the element of triplet (check if the triplet occurs on the first beat) is common. Hence, one could form an etymology of our syncopation like this (Example 2):

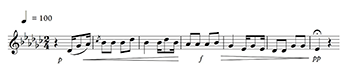

Example 2. Excerpt of Andrade’s (n.d.) original notation (click to enlarge) |

[1.6] Perhaps this note #9 is the musicologist’s most expressive intuition (even if not developed further) regarding the rhythmic structure of Brazilian music in general. Although it is not possible to pinpoint the exact date of its writing, we know that Andrade was working with this idea around 1926, when it appears formulated in a lecture about Brazilian composer Ernesto Nazareth.

Studying, for example, the evolution of syncopation, a mathematical offbeat of European music, as used both by Bach and in Portuguese fado (and still in colonial Brazil, as evidenced by the modinha "Foi-se Josino," recorded by [Johann] Spix and [Karl] Martius . . .) towards our syncopation, an absolute rhythmic entity and, so to speak, indivisible. This evolution is reflected in the work of Ernesto Nazareth. But all this would lead us to another two hours of talking. And I confess that, despite the abundant documents I am collecting and studying, many historical and even technical points would still remain uncertain, in a virgin territory where even the name "maxixe" is not very well understood. Nothing has been done about this, and it is a shame. (Andrade 2013)

[1.7] The intuition present in this passage is impressive for exposing—perhaps for the first time by a Brazilian musicologist—the theoretical formalization, albeit incipient, of a displaced but consistent accent in relation to the main meter, functioning as a regular, tensioning, and complementary element to the meter. The formulation of a second rhythmic support point emerges, which is structured and constant, yet displaced in relation to the main beat. What Andrade seeks to describe—without a clear formulation—is a type of accent displacement that does not occur as a deviation or rupture of the musical discourse, but as a rule of the structure, which, appearing constantly in the performance of musicians from various American cultures, gains a different status from European syncopation. A consistent theorization of this type of rhythmic structure only comes with later musicologists linked to the study of African music (Locke 1982; Nzewi 1997; Lacerda 2005; Danielsen, Johansson, and Stover 2023).

[1.8] Perhaps due to the lack of dialogue about processes in African music, Andrade coined confusing names for the process, such as “absolute constitutional rhythmic cell,” “indivisible accent and time entity,” and “indivisible entity,” among others, but always marking the character of the rule of Brazilian syncopation and the displaced rhythmic support. The main point is that, for the musicologist, this way of syncopating is structurally different from European syncopation, with the striking characteristic of “American syncopation” being the accentuation at a reference point that, in performance, does not fall exactly on the second eighth note, but blends with the triplet.

[1.9] The strong core of this intuition is the idea that in the modern music of the American continent “there is a true displacement of the strong accent,” which generates another set of rhythmic formations, different from European ones. It does not occur as a deviation but as a constancy. This “displacement” forms a second center of metric gravitation, which will attract accentuations from the sung text, the melodic structure, and the accompaniment, causing them to fall in a place different from the referential metric accent of the measure.

[1.10] Thus, in Brazilian music, some musical events respond to the metric accentuation of the established measure as a reference, while others respond to a displaced and oscillating point, which generates a music that we end up calling structurally syncopated, formed by the superposition of a second sliding rhythmic support point that is not exactly fitted into the theoretical binary or ternary subdivision.

Note #23:

Syncopation

Rodney Gallop, in his admirable study on Fado, studying the rhythm of Fado (which he actually considers better in 4/4), cites precisely a case of syncopation on the first beat, which is typically an American habanera, naturally brought through Brazil. And he recognizes other Portuguese songs in the same rhythm mentioned by Fernandes Tomás (“Velhas Canções e Romances”) as originating from black Brazil.

Note #24:

Syncopation

Rodney Gallop [1933a; 1933b] throughout his study on Fado, considers the syncopation of Portuguese Fado and other Portuguese dances, as well as American syncopation in general, as originating from Africa.

Note #25:

Syncopation

Rodney Gallop [1933a; 1933b], studying Portuguese Fado from Lisbon, noted that it has the rhythmic freedom of jazz, and shares with it certain ways of syncopation and rhythmic suspension. (Andrade n.d.)

[1.11] These three notes refer to Rodney Gallop's article “The Fado” (1933a, 199–213). Regarding a collection of fados (Thomas 1913), Gallop asserts that “it is noteworthy that in each case the collector was informed by the singer that the song was of Brazilian origin. It seems, therefore, that this characteristic is a Brazilian contribution (i.e. originally African) to the origin of Fado.” As Andrade notes, Gallop is realizing the network of connections between Portuguese, Brazilian, and North American music, in the somewhat unclear context of their connections to African musical imagination.

Note #28:

Syncopation

Anticipation

In number 26, p. 343, there is a Cuban Danzón with anticipations. Note in the same piece (3rd part) the strong Afro-Cuban character showing influence from Cuba on jazz. (Andrade n.d.)

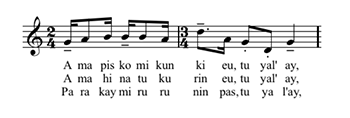

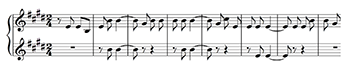

[1.12] Andrade analyzes here a passage from a book by Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes, Folklorismo (Fuentes 1928). On page 343, there is a reproduction of the danzón “Los Chinos,” by Raimundo Valenzuela, for piano. The piece, in 2/4, is structured around two recurring rhythmic motifs, which we refer to here (Example 3) as A and B:

Example 3. Rhythmic motifs in “Los Chinos,” by Raimundo Valenzuela (click to enlarge) |

Andrade begins to suspect that the presence of these same structures in various places across the Americas may be evidence of mutual influence, or even the possibility of a common origin for all of them. This origin might not be European, but rather African or Indigenous.

Note #35:

Scottish Syncopation?

154, 22 (Andrade n.d.)

[1.13] In this brief note, Andrade examines Newman Ivey White's book, “American Negro Folk-Songs” (1928), in which he seeks connections between American culture and traditional African cultures. Commenting on the relationship between African and African American cultures, White asserts that “there is practically no connection between the American Negro and Africa. Nor is there any reason for supposing that there is any connection in subject matter.” However, regarding music, White holds a different opinion, which Andrade highlights in the following passage:

As for the music, it seems probable that there is a much stronger connection, but on this point I have insufficient technical knowledge to do more than summarize and balance what has been said by trained musicians. [. . .] Mrs. Burlin,(4) whose work with Negro music seems on the whole to be more careful and reliable than that of most other critics, is of the opinion that, though American Negro music absorbed much from the music of the white man, all of its really distinctive features were brought from Africa (White 1928).

Note #54:

Syncopation in Africa

584, 24, 26 (Andrade n.d.)

[1.14] In this note, Andrade is studying the article “African Negro Music” by Erich M. Hornbostel (1928). As the director of the Phonographic Archive in Berlin, Hornbostel was a pioneer in the academic study of African music. In this article, Hornbostel identifies some characteristics that he considers fundamental, which will be further developed by later authors: a highly developed rhythmic structure and, in vocal music, the predominance of responsorial singing and polyphony.

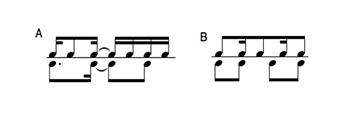

[1.15] In a passage highlighted by Andrade, Horbostel is analyzing the rhythmic structure of a recording of Fang (Pangwe) music from Central Africa, for xylophone and chorus. Recognizing a constant metric cycle of twelve time units, he expresses uncertainty about the possibility of gathering these units into a time signature formula and grouping them between bars. He suggests that the groups of twelve units (notated as eighth notes) adhere to an ambiguous organization between binary and ternary meters (Example 4):

Example 4. Hornbostel’s (1928) rhythmic analysis of a Fang music excerpt (click to enlarge) |

[1.16] The different interpretations of the rhythmic structure are interesting because they admit the possibility of different metric positions, the coexistence between binary and ternary meters, and constructions in hemiola (or cross-rhythm). However, in the copy of the book that is in his library, Andrade also underlines the passage: “the combination of binary and ternary division is characteristic of African metric in general,” noting next to the page: “syncopation?”. This gives clues to his doubts that hemiola or cross-rhythm processes would be linked to the idea of syncopation.

[1.17] Furthermore, Hornbostel, in his analysis, considers a rhythmic displacement in which some attacks by the xylophone (which according to his interpretation of the structure should be ‘upbeats’, therefore unaccented) are actually accented ‘downbeats’. And when the main theme returns in the choir, in another metric position, Hornbostel is led to consider that this entire theme is syncopated. At this point, he comments: “that the lower part [the returning theme] is syncopated surpasses our understanding,” a comment that is highlighted by Andrade. Hornbostel was identifying processes that would later be named (e.g. by David Locke 1982), among others, as offbeat timing, types of musical structures built on various rhythmic points or displaced from the regular metric pulse, common to various African musical styles. The process identified by Andrade in note #9, if applied to this example, would account for this incomprehension by Hornbostel.

[1.18] Forwarding his conclusions, Hornbostel proceeds to elaborate analyses on music and rhythmic conception in Black Africa in general, which Andrade annotates, curiously, in the margin of page 26: “Now it seems to me undeniable that the A.[uthor] always thinks and criticizes in a European attitude, Europeanly

Note #73:

There are pieces in the collection of Mme. Béclard D’Harcourt with syncopation.

And what if syncopation was American and developed by the Blacks before? (Andrade n.d.)

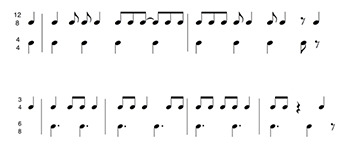

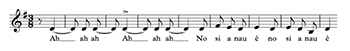

[1.19] In this note, Andrade considers the hypothesis of the French ethnomusicologist Marguerite Béclard d’Harcourt that syncopation could already exist in the traditional music of the pre-colonial American territory. In the fifth volume of the Encyclopédie de la Musique et Dictionnaire du Conservatoire, there is a section called “La musique indienne,” signed by Béclard d’Harcourt. In this section, the “Amerindian example” indicated by Andrade is as follows (Example 5):

Example 5. “Amerindian example” by Marguerite Béclard d’Harcourt, in Lavignac (1913) (click to enlarge) |

About this example, Béclard d’Harcourt writes:

These rhythms deserve attention because they are known throughout America. Are they really indigenous or are they black? We have not been able to clarify this point yet. [. . .] On the other hand, these rhythms are found, with the same characteristics, in indigenous songs from the USA, and all modern North American dances reflect them: two-steps, cake-walk, etc., as well as another dance of Argentine and Brazilian origin, the famous tango. In these dances, the dual influence of black and indigenous is noticeable. Were these rhythms common to both races? We believe so . . . . (Lavignac 1913)

Note #74:

In “El Canto Popular” edited by the Argentine Literature Institute, there are Inca songs with syncopations (I own the volume) (Andrade n.d.)

[1.20] This refers to the volume El canto popular (1923). Among the Peruvian and Bolivian traditional melodies transcribed in this magazine, Andrade highlights those “with syncopation,” from which I transcribe some small excerpts here (Examples 6 and 7):

Example 6. Excerpt from “Indigenous dance (collected in the surroundings of Cuzco)” (click to enlarge) | Example 7. Excerpt from “Aymara dance (collected in the highlands)” (Rojas 1923) (click to enlarge) |

Note #76:

Syncopation

“Clear syncopated movements can be noticed in some phonograms.” Such are those of numbers 14594 and 14595, where the bolero rhythm in 3/8 is distinctly found. Roq. Pinto, Rondônia, 89. (Andrade n.d.)

[1.21] Here, Mário de Andrade notes a passage from a book by Edgard Roquette Pinto (1919). In the cited passage, Roquette-Pinto is describing the music of the Pareci Indians, whose phonograms were recorded during a field trip conducted in 1912. Here are the beginning of two transcriptions from Pinto’s book (Examples 8 and 9):

Example 8. Excerpt from “Phonogram 14.594 e 14.595” (Pinto 1919) (click to enlarge) | Example 9. Excerpt from “Phonogram 14.596” (Pinto 1919) (click to enlarge) |

The note engages with Béclard d’Harcourt’s hypothesis, connecting it to examples of syncopation in the context of Brazilian Indigenous music.

2. Considerations on the manuscript

[2.1] At a first level of understanding, Andrade's investigation in this manuscript collection can be seen as a kind of ‘hunt for syncopations’: a sort of functional operation in which ‘white’, ‘Black’, and ‘Amerindian’ elements are juxtaposed, and the syncopation would come from one or the other; that is, its ‘origin’ would be either white, Black, or Amerindian. At a second, much more interesting level formed over the years, Andrade refines his musicological considerations by considering the formal analysis of musical structures through historical and socioeconomic perspectives: somewhat against his will, Andrade’s own notations reveal that American syncopation in general is not simply that of Blacks, whites, or Indigenous peoples—that is, a direct and preserved transposition of displaced traditions—but rather forms in complex dynamics involving colonizers, colonized, and deportees in a kind of transatlantic “rhythmic network” in which, as Luiz Felipe de Alencastro (2000) suggests, traditional cultures of various peoples are displaced, disbanded, and rearticulated within the complex system arising from modern transcontinental commercial expansions.

[2.2] Upon realizing that syncopation is a different process in each of the researched cultures, what comes into play is the very movement of the network: the encounter and coexistence, whether violent or not, syncretic or not, of the figures—syncopated or not—from the original systems. This movement triggers dynamic processes of disturbance of traditional cultures, outlined by the overall movement of this “rhythmic network,” which may undergo greater or lesser modifications. It is by operating at this second level of understanding—unpublished—that Mário de Andrade manages to escape the reification of the term “syncopation” and the consequent emptying of its meaning: until then the term seemed merely technical, frozen, as if it could float unchanged over time and space, as if it could exist outside of history and travel intact, from one place to another, across the Atlantic. The search—rather mechanical, by the way—for syncopations of eighth notes between sixteenth notes in the two-four time signature is a reflection of this reification. By considering the broader context of different dimensions, the interpretation of syncopation in this manuscript contains the possibility of abandoning its figural state of a dictionary term and gaining the life of the real, complex, dynamic, multidimensional, and meaningful event.

Enrique Valarelli Menezes

Universidade de São Paulo

Carlos Eduardo de Barros Moreira Pires

Works Cited

Alencastro, Luiz Felipe de. 2000. O trato dos viventes: formação do Brasil no Atlântico Sul, séculos XVI e XVII. Companhia das Letras.

Andrade, Mário. n.d. “Envelope 13.” Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, Universidade de São Paulo. Arquivo Mário de Andrade.

Arquivo Mário de Andrade. 1972. Namoros com a medicina. Martins ; Instituto Nacional do Livro/MEC.

—————. 2013. Música, doce música. Nova Fronteira.

—————. (1928) 2020. Ensaio sobre música brasileira. Editora da Universidade de São Paulo.

Andrade, Mário de, e Oneyda Alvarenga. 1987. As Melodias do boi e outras peças. Livraria Duas Cidades.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Public Worlds 1. University of Minnesota Press.

Danielsen, Anne, Mats Johansson, and Chris Stover. 2023. “Bins, Spans, and Tolerance: Three Theories of Microtiming Behavior.” Music Theory Spectrum 45 (2): 181–98.

Fuentes, Eduardo Sánchez de. 1928. Folklorismo: articulos, notas y criticas musicales. Imp. Molina y compañia.

Gallop, Rodney. 1933a. “The Fado.” The Musical Quarterly 19 (2): 199–213.

—————. 1933b. “The Folk Music of Portugal: I”. Music & Letters 14 (4): 343–54.

Hornbostel, Erich Moritz von. 1928. African Negro Music. Oxford University Press for the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures.

Lacerda, Marcos Branda. 2005. “Transformação dos Processos Rítmicos de Offbeat Timing e Cross Rhythm em Dois Gêneros Musicais Tradicionais do Brasil.” Opus (Salvador, Brazil) 11 (1): 208–20.

Lavignac, Albert. 1913. Encyclopédie de la musique et dictionnaire du conservatoire. Première partie, Histoire de la musique. Delagrave.

Locke, David. 1982. “Principles of Offbeat Timing and Cross-Rhythm in Southern Eve Dance Drumming.” Ethnomusicology 26 (2): 217–46.

Massey, Doreen. 1993. “Questions of Locality.” Geography 78 (2): 142–49.

Miceli, Sergio. 2012. Vanguardas em retrocesso: ensaios de história social e intelectual do modernismo latino-americano. Companhia das Letras.

Nzewi, Meki. 1997. African Music: Theoretical Content and Creative Continuum: The Culture-exponent’s Definitions. Inst. Für Didaktik Populärer Musik.

Pinto, Edgard Roquette. 1919. Rondonia. Imprensa nacional.

Rojas, Ricardo. 1923. El canto popular. Documentos para el estudio del folk-lore argentino. Tomo 1. imp. y casa editora Coni.

Sánchez de Fuentes y Peláez, Eduardo. 1923. El folk-lor en la música cubana. Imprenta “El Siglo XX.”

Thomas, Pedro Fernandes. 1913. Velhas canções e romances populares portuguêses. França Amado.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2011. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton University Press.

Verger, Pierre. 2021. Fluxo e refluxo do tráfico de escravos entre o Golfo do Benin e a Bahia de Todos os Santos dos séculos XVII a XIX. Companhia das Letras.

White, Newman Ivey. 1928. American Negro Folk-Songs. Harvard University Press.

Footnotes

1. Mário de Andrade “was the greatest literary figure and the hegemonic cultural leader at this key moment of transition in Brazilian intellectual history” (Miceli 2012, 106). Brazilian Modernism was an artistic, cultural, and literary movement that emerged in the early twentieth century, particularly from the 1920s onward. This movement sought to break away from the traditional and Europeanized conventions, promoting an art more aligned with Brazilian reality and identity.

Return to text

2. Andrade uses the term “America” in distinct ways, generally referring to the Americas, or the American continent, and sometimes as an adjective or descriptor of some aspect, as in this passage, with African-Americans.

Return to text

3. The terms are generally associated with dance and body movements. “Remeleixo” is informally used in Brazil to describe a lively dance with relaxed and sensual movements. “Requebro” usually describes a smooth and sinuous movement of the body, or how someone dances or moves in a seductive manner. “Dengue” has various meanings; it can be used to describe delicate movements and also refer to a dance or dance style that is very sensual, with hip movements.

Return to text

4. Translators’ note: Natalie Curtis Burlin (1876–1921) was a North American musicologist who made many studies on Indigenous and African-American music. Andrade had some of these studies in his library, which were an important reference for him.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Lauren Irschick, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4215