“At One End of the Endless Universe”: Akira Nishimura’s Interview with Isang Yun*

Joon Park

KEYWORDS: Isang Yun, Hauptton Technique, Post-1945 Music, Cold War, Korean Composers

ABSTRACT: This interview of Isang Yun was conducted by Japanese composer Akira Nishimura for Japanese periodical Musical Arts. Their conversation explores the social, cultural, and philosophical contexts for Yun’s compositional decisions. As a Korean native composer exiled in Germany, Yun was directly impacted by the Cold War politics while also living through the early days of globalization. Yun’s Hauptton technique could be understood as his response to the high-modernist trend of the 1950s and 60s Germany, in particular, dodecaphony and avant-garde experimentalism. The realization that new compositional trends that gained popularity in Europe at the time are still fundamentally rooted in Western musical concepts might have steered Yun toward a path to an authentically Korean musical expression. As Yun discusses in the interview, a tone in the East Asian context is not created by the composer. Instead, Yun remarks that “the universe’s tone flows without end,” which reflects his Daoist influence. The conversation paints a picture of Yun as a composer who envisioned a fundamentally different method of composing not only as a composer in search of original music but also as a Korean composer living in the West.

PEER REVIEWER: Ji Yeon Lee

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.12

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Translator’s Introduction(1)

[0.1] A Korean-born German composer, Isang Yun (1917–1995), lived through Korea’s tempestuous twentieth century, from enduring Japanese colonial rule to the Korean War and the resulting North-South divide of the Korean peninsula. From 1957, he lived in Europe. In 1967, he was abducted from Berlin to Seoul by the South Korean National Intelligence Service and initially sentenced to life imprisonment for espionage.(2) He was pardoned by the president in 1969, forcibly exiled, and denied reentry until his death in Berlin in 1995. During this period, however, Yun occasionally visited Japan and engaged in conversation with Japanese composers.

[0.2] This interview is from a Japanese music periodical, Musical Arts [The Ongakugeijutsu 音楽芸術], published in September 1984. It was first translated from Japanese to Korean by Jungbok Seo and published as a part of the collected essays on Yun’s music, Musical World of Isang Yun [윤이상의 음악세계], (Yun and Nishimura 1991). I translated from this Korean version, and my English translation was later proofread by Susumu Watanabe, a native Japanese composer, to ensure the integrity of the original Japanese publication. During the proofreading process, it was revealed that the Korean translation contained some errors. Most notably, the annotation for Yun’s drawing of the Hauptton schema (Example 2) contains misplaced labels for Hauptton’s three stages. (See note 9 for details.)

[0.3] This interview took place as a post-concert conversation between the two composers. The interview covers Yun’s compositional philosophy behind the Hauptton technique, in particular, its relationship to Korean traditional music. The conversation continues to his comparison of Western classical and East Asian musics, which shows his ethnocentric tendency in describing them. He then provides a short analysis of his Flute Concerto (1977) from the Haupttone perspective. The interview concludes with a brief discussion of his imprisonment in South Korea and his message to the new generation of composers.

[0.4] Yun’s Hauptton technique might be commonly known to anglophone scholars through numerous DMA dissertations and master’s theses, often written by Korean-speaking student scholars in North American academia.(3) Outside of this, there is a limited number of writings in English, although many of Yun’s writings and lectures are published in Korean and German. Yun’s Hauptton technique could be understood as his response to the high-modernist trend of 1950s and 60s Germany, in particular, dodecaphony and avant-garde experimentalism. Yun’s Hauptton technique questions the Western assumptions about a tone as the fundamental building block of musical works. From Yun’s perspective, a tone in the East Asian context does not exist in the abstract and, therefore, cannot be organized according to some taxonomic imagination. A tone must first come into being through the different stages of vitalizing motions. Because the unfolding of each tone takes time, the temporality is embedded in the concept of Hauptton. This contrasts a common separation of pitch and time in the West and, in particular, a treatment of beats as objects that exist as “durationless points in time” (Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1996, 334n3; London 2004, 24).

[0.5] Yun felt the need for a fundamentally different method of composing not only as a composer in search of original music but also as a Korean composer living in the West. The realization that new compositional trends that were popular in Germany at the time were fundamentally rooted in the Western musical tradition (no matter how new), steered him toward a path to an authentically Korean musical expression. Yun remarks in his interview with Luise Rinser that “I don’t think it is right to say that if you learn Western compositional technique, you can become a Western composer” (Byeon 2003, 286). He continues that, during his compositional education in Germany during the 1950s and 60s, he “was able to study to express that which is Eastern, that which is flowing in [himself], [with] the language of Western music.” In other words, his compositions express the elements from Korean culture that were already part of him through “sedimentation” during his upbringing in Korea (Merleau-Ponty 1962). This self-reflection provides a context to understand some of Yun’s compositional choices, in particular, his adherence to composing for Western orchestral instruments and not incorporating any East Asian traditional instruments as other composers with East Asian background (e.g., Toru Takemitsu, Chen Yi, and Tan Dun) often have. As Jeongmee Kim notes, “Yun’s Korean musical heritage is expressed through a more abstract, philosophical, and internalized use of ethnic materials” rather than through some apparent quotations of folk tunes or timbre (Kim 2004, 174). Likewise, it would have been considered as an extension of the Western musical tradition to establish some new structures through taxonomizing musical symbols and their ordered distribution.

[0.6] This interview has seven sections, and each section is titled with a quote from the interview. Over the course of the interview, Yun discusses the influence of Korean ceremonial court music and folk music in his compositions, describes his concept of “flowing line” that contrasts the Western Classical notion of voice leading, presents the Daoist and Buddhist contexts for his Hauptton technique, and provides a brief analysis of his Flute Concerto. He also discusses his experience of composing and premiering the opera Die Witwe des Schmetterlings (Butterfly Widow) while being incarcerated in a South Korean prison.

1. “Within a flowing line [流れる線], there is one important tone [音]. With this tone in the center, I call all sounds that surround it Hauptton [主要音].”

[1.1] Nishimura: Yesterday (August 24), we were greatly moved after listening to the collection of your compositions. Your works are being performed around the world, including in Europe, but this Kusatsu festival seems to be the first major exposure of your compositions in Japan.

Including the new composition, Quintet for Clarinet and String Quartet no. 1 (1984), there were five chamber pieces and two concerti, which enabled the audience to access the core of your artistic style, and the concert was filled with great enthusiasm. The performance level was excellent, and the audience listened intently with silence.

Today’s conversation is for Musical Arts. I would like to ask you about mainly technical aspects of your compositions that leave a strong impression on the listeners.

When looking at your list of compositions, I find numerous operas, orchestral music, chamber pieces, vocal pieces, and so on, but they all seem to be composed for so-called “Western” instruments and in “Western” configuration. For Japanese composers, there are some compositions written for Japanese traditional instruments. Have you composed a piece for traditional Korean instruments?

Yun: I have not. It is because I did not have the right opportunity. A composer, after all, is often influenced by their surroundings when choosing instruments and compositional content. Japanese social condition enables the composers to establish close correspondence with traditional Japanese instruments and performers. In contrast, I live far away from my home country and the political persecution by the Korean government severed all ties between me and Korean traditional musicians. I have not met Japanese traditional musicians and had no opportunity to pursue such occasions.

[1.2] N: Nevertheless, I can see that the titles of your pieces or the theme of your opera often incorporate Chinese or Korean elements. Have you always had the thought of reflecting such East Asian culture in your works?

Y: Of course. Because it is the basis of my organic being, I think it is common for any composer to start from their basis and to develop further.

[1.3] N: I would like to ask you more in detail about those ethnic aspects of your composition. For example, have you been influenced by Korean A-ak [Korean ceremonial court music]? I can sense its influence in your pieces

Y: Exactly as you said. Japanese court music has parts that are imported from Korea and parts that are from China. But its contents are qualitatively different from Korean A-ak. In addition, there is a vernacular musical tradition in Korea that is neither court music nor ritual music, which had been enjoyed by both the commoners and the aristocrats, similar to the musical sphere you would see in Western intellectuals. In addition to A-ak, which takes a strict stance, there are Korean art songs and folk music. One of them is called Namdo Chang [남도창, 南道唱], which is folk music that features a clear and loud voice and has been passed down in the southern Korean region. I have been greatly influenced by that genre.

[1.4] N: That underlies your linear [線的] musical language [語法]. It would be reasonable to say that the characteristic linear movements, ranging from fine microtonal tremors to tremolos wider than a third, come from the Korean singing [歌唱] style.

Y: Yes. I learned a lot from A-ak’s strict organization and philosophical content, and vocal music’s smoothly flowing linear beauty, such as Namdo Chang and Gagok [가곡], or other vocal genres.(4) Based on these, I organized my own musical theory of linear motion.

[1.5] N: When I listen to the lines in your music, these lines sound more vital, unlike the Western line. I feel that the lines are filled with abundant expressions and their flow transforms without end. Korean ethnic music also has abundant lines at its source, including various vocal music

Y: Yes. And it also expands to instrumental music. One could say that all instrumental music is developed by continuing ideas from vocal music. For example, a flute-like instrument made with bamboo [橫笛] called Dae-gum is one of the Korean traditional instruments. Melodies played by that instrument are inherited from singing. They have their own charm of linear music.

[1.6] N: So, you do not directly use Korean instruments or singing styles in your compositions but transform them into more general grammar [普遍的な語法] and construct a theoretical framework. And an idea derived from it is your Juyo-um (Hauptton, [主要音]) technique, which structures your compositions.(5)

Y: Yes. It’s Hauptton. In the West, music scholars who study my works also use the term Ton-Einheit. It means, the oneness of sound. Within a flowing line [流れる線], there is one important tone. With this tone in the center, I call all sounds that surround it Hauptton, and the scholars call them sonic oneness. There might be a better Japanese word for it.(6)

[1.7] N: This concept is not in some harmonic techniques that create certain functions, right?

Y: Of course, this is a linear concept. It refers to a singular note and a singular melodic line. But when linear elements are stacked, they become Hauptklang [主要音響].(7) Lines become a bundle and begin to flow. In short, each line is Hauptton, and when it is bundled and flows it is Hauptklang. In other words, each of the lines is analogous while the whole is uniform.

2. “Motion [動] is stillness [静] and stillness [静] is motion [動]. It is my music’s overall perspective.”

[2.1] N: I have sensed from your description, maybe I am off-topic here, but do you know the term “heterophony”? To put it concisely, it means the coexistence of the main melody and an embellishing melody. I think, in heterophony, an essential idea simultaneously takes various appearances [상, 像] and they coexist. Based on what you have described, wouldn’t there be a correlation between the Hauptton concept and heterophony?

Y: Yes there is. My music is monistic (monistisch). My music is not polyphonic or pluralistic. For example, Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s music is pluralistic. Elements from different roots flow together, maintain order, oppose, but ultimately come together to greatly elevate the music. But in my music, all flows are uniform, whether it is the mainstream or branch. “Uniform” [一元] may not be the best word. To use it here because of the lack of a better term, various lines flow through according to the same principle and aesthetic perspective, and the individual lines are in accordance with each other. In addition, even when a single line is used separately [分断的], when combined, the uniformity emerges from them.

[2.2] N: Your pieces often sound pluralistic depending on locations. It seems to me that they are not essentially in conflict with each other, but rather come from Eastern thinking, for example, like the yin and yang.

For this reason, toward the end of your works, they [the seemingly conflicting elements] are fused in a higher dimension and strongly express their bodily unity [一体]. That seems to be the reason why I always hear deeply moving codas. Am I right in feeling this way?

Y: Exactly, as you said.

[2.3] N: I feel that, in your works, a drastic contrast from our Japanese composers, a point where Japanese composers cannot reach, is their robust sustaining force. Including my contemporaries or our predecessors, regardless of which generation is composing, when a current Japanese composer premieres a piece, it seems extremely difficult to sustain the 15-minute length. For example, even if a piece can be sustained for a very charming 6 minutes, it cannot sustain that robust charm for about 20 minutes. But your music exceeds at least 10 more minutes over our [Japanese composers] duration. It is truly astonishing that not only 15 minutes, but 25 minutes of robust persistence is structured through constant tension and contraction. I think we lack some kind of rationality or logic to maintain such a level of persistence. Instead, we try to process through mental and emotional means, which leads away from achieving the persistence. What are your thoughts on these issues?

Y: That is the point. Modern music, the so-called “avant-garde” modern music flourished during the 50s and 60s and in the 70s, although these trends have thinned out, the pieces during these periods do not exceed 10 or 15 minutes in duration. But it is true that my pieces maintain tension for a long time. The foundation of my music, the linear element, possesses a deft persistence. That “nature” [ナチュール] itself enables the unlimited persistence. For example, the secret of not being bored while listening to the same line for hours, like Noh [能] or Kabuki [歌舞技] is this.

Perhaps Japanese composers follow the old Western traditional formalism even though the compositional materials [マテリアル] might be modern. Then, a contradiction will emerge from the formalism, the materials, and the piece’s own contents. Maybe they are blocked by the contradiction and are faced with the moment where the piece cannot last.

East Asian traditional music does not possess Western-style formalism. In Western music, there is a clear process [プロセス] to assemble a composition based on clear models. Outside of these models, music cannot be sustained.

Therefore, it would be dangerous for the Eastern sensibility to be dominated [支配] by Western formalistic thinking.

[2.4] N: You mean the way of thinking, which sees composition as the so-called “closed-off” [閉じた] world, cannot express the East Asian spirit?

Y: Yes. I think one would be freed from the world of enclosed tones [閉ざされた音] if one composes with the traditional East Asian way of thinking that music can begin and end at any point in time.

However, there still needs to be its own organizing principles [自体の秩序] and polished aesthetics [整然とした美学] for making and sustaining sound. I discovered one of those principles first as an East Asian composer. That is Hauptton. Many elements are implied in this concept. A line is not simply a line, but a moving point is also a line from a broader perspective.

Like this, a line can be endlessly varied depending on the interpretation and reception. This is possible for East Asians. From Western reasoning, it would not be called “a line.” An Asian would accept it as “this is a line.” Likewise, the East Asian way of thinking is intuitive. This intuition transcends the logical/illogical distinction and has the strength to take in and digest with creative force.

Therefore, people speak about my music as flowing, smoothly flowing, an endless repetition of the line. The smoothly flowing line is not a straight line but is a curved line (湾曲). And there are various ways a line can be curved. Within a curve, there are various parts. The part and the curve each contain a universe within itself. It means that within a universe, there is another universe.

In the case of a line, a smooth line would seem like it is in motion if we compare it with a straight line. But the same line next to a more vibrant line would look like it is rigid. It is always relative like this. All things, including dynamics and figurations, are absorbed and are expressed as a linear flow.

As you may know, there is a composition of mine called Reak (藝樂). In it, numerous notes are busily moving. Every single one of them is moving if we look at it through a microscope. From a broader perspective, we can see a wide current. If we zoom out a bit more, everything seems to stand still. Here lies the truth expressed in the East Asian philosophical maxim: stillness [静] is motion [動] and motion [動] is stillness [静]. These two distinctive elements, the yin and yang, are in harmony with each other. And they always need each other while supporting the force. Everything is in motion while, from afar, it almost seems to be at a standstill. Motion is stillness and stillness is motion. It is my music’s overall perspective.

3. “This universe’s tone flows without end. My works are merely an arrangement of a tiny little part of it.”

[3.1] N: After listening to what you said, your music feels like a living organism. The organism is formed with various cells, and each cell behaves according to its role, which makes it a complete unit on its own. But the whole organism is also a complete unit on its own. And the organism possesses a will in some direction. Therefore, it is not the Western style of accumulating small units but is having the whole first where each of its parts lives internally. And that forms a larger living being. In other words, there is a large universe and within it, there is also a small universe. I feel like this is what you are saying.

Y: Yes yes. The fundamental problem is—I give lectures about my music to Westerners—in these instances, I always state my methodology about the sound itself differs from the Western one. I do not use tones that abruptly begin or end. My tone must first be equipped with some elaboration or preparatory sound to be settled, and the movement begins to enliven that sound. After the movement begins, a great life force emerges. And then, the next sound is settled and so on.

[3.2] N: This might be too emotional a way to put it, but your music feels like traces of blood [血の跡] left by a tone that flows continuously through you from an infinite past towards an infinite future. In other words, it seems to me that the lines you employ do not have a beginning and ending, but endlessly continue, and you manifest [顕在化] a moment of the lines.

Y: As you said. Let me articulate it a bit more philosophically. I think a tone [音] is not created by a composer. You grasp it [つかむのです, 움켜잡는것]. You give order to the tones and organize them based on the techniques you have learned. You then supplement flesh and blood to it according to your own aesthetic goal to create an artwork.

I am not a practitioner of Daoism but I have profound respect for it. According to its teachings, this universe is filled with tones. Regardless of their ugliness or beauty, there are numerous tones. And each person has their unique character and specialty. According to the difference in one’s taste, morality, innate personality, and many other conditions, each individual possesses a unique antenna for the reception of different tones. One cannot hear all tones residing in the universe, therefore one receives through their antenna the tones that suit their constitution and instinct. One collects them and assigns arrangements to them to create music. I see compositions as being filtered through myriad spiritualities according to the composer’s character.

This universe’s tone flows without end. My works are merely an arrangement of a tiny little part of it. This is what I think. You erect your antenna; you organize according to your conscience, mental capacity, and the techniques you have learned; and then you present it as a composition.

The Western compositional method is not like this. A human being first creates tones based on their sensibility and assigns arrangements, and then they must create music according to the established procedure within a limited time and adds content to it. Therefore, for the Western people, the form and content, these two aspects are deemed important in artworks. But in our East, there is something else, this is what I am saying now.

[3.3] N: Then, you are saying that, about the tone that flows infinitely to the future, it is impossible for the people outside of the East to sense it.

Y: Yes.

[3.4] N: Then the “rationality” [合理性] you talk about is different from the Western rationality?

Y: Yes. I do not advocate for rationality, but as I have said earlier, I consider an orderliness [秩序] important. A good ordering as an artwork. But in my music, this order is not really rational in the Western compositional sense. In other words, I think my music resides somewhere in between rational irrationality or irrational rationality.

Therefore, I try to avoid rational elements in my compositions as much as I can. But I do not get into a mess. The reason why I do not get into a mess is that the Hauptton theory assigns its way of arrangement in my mind.

[3.5] N: Is this theory rigorous? In terms of its compositional methodology.

Y: Yes, because it has a model. Let’s hear the simplest model. First and foremost, a tone is prepared before its departure.

4. “A moment reflects eternity, and the eternity can be captured as a moment.”

[4.1] N: Looking at your Flute Concerto, the opening of this piece seems to be a Hauptton

Y: Yes. This piece is born within nothingness [無] and ends as nothingness. That is the Buddhist philosophy. From a complete void, some tones emerge. It is by coincidence. Therefore, there is no destined inevitability in my tone theory as to which tone should begin the piece. But while it seems that there’s no inevitability, there still is one.

Example 1. Yun’s Flute Concerto (1977), excerpt

(click to enlarge)

First of all, it begins with a low pitch [Example 1].(8) With the

The

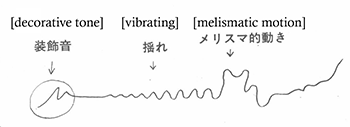

Example 2. Yun’s drawing of the Hauptton schema

(click to enlarge)

Now, it is a decorative tone. Beginning from the decorative tone, the trembling grows larger and, at times, the vibrato gets as wide as a fourth. The decorative tone exists to concentrate on the tone’s beginning, and it is meaningless by itself. It grants power through its existence. Once the powerful tone is initiated, it begins to run on its own. As it runs, it creates vibratos in order to heighten its lifeforce and tension. Through vibrato, the concentration and tension are increased. And melismatic elements are added [Example 2](9)

It is often the case that there are two Haupttones. When there are two, they form a relationship of yin and yang. For example, it is also a relationship between Motion (動) and Stillness (静).

Also, a Hauptton sometimes intermittently appears in the shape of little pieces. In any case, it appears as various lines. To represent one of the original forms as a drawing, it looks like the above. But there are cases where it is more active or more static. Also, there are cases where it has a tendency upward and downward. It might appear as disjunct, but theoretically, it always exists. You can say that it is hiding somewhere. Even if it is disconnected, there will always be its next part. Do not think too dogmatically, think more intuitively and you can understand this music.

For an example of a Hauptton, my piece, Etude for Solo Flute no. 1 would be easy to understand.

In the case of a Hauptton, the relative change between yin and yang can be understood through various steps from micro-timing or macro-timing. In it, a moment reflects eternity, and eternity can be captured as a moment.

That is the Eastern way of thinking about time (時), which is completely different from the Western conception of time.

[4.2] N: The Sonata form might be one example that reflects the Western formalistic view of time. In Sonata form, there are primary and secondary theme areas. They are contrasting sections that independently develop [the sense of] time. Therefore, it is completely different from yin and yang, which contain an eternity in a moment. This is what you’re saying.

Y: Yes. The Western Sonata form cannot be established without the first theme. It cannot be established without the second theme either. But in my music, any part can be omitted. It is constructed so that all that flows each possesses its own lifeforce.

[4.3] N: This is a terribly tasteless metaphor but a lizard’s tail can grow even after it has been cut off. The strength of an organic lifeform exists in your music.

Y: Correct.

5. “Purity comes from overcoming the contradiction within the whole.”

[5.1] N: With regards to the organization, you often write about the stories behind your compositions like Double Concerto [1977], Cello Concerto [1976], or the chamber music called Images [영상, 1968]. In reference to what stories these pieces tell. For example, your double concerto “Gyunwu and Jiknyeo” takes as its background the tragic story about “Chilseok” (七夕).(10) Do your compositions often take these kinds of tale-like elements underneath?

Y: In fact, I would like the listeners to hear my music without any of these background stories. Because my past life experience has tangled twists and turns, I hope to be the most humanistic artist. In the past, I once thought that composing music is akin to listening to tones in a near-celestial position and imbuing them with an order.

[5.2] N: Are you referring to a metaphysical [メタフィジカル] realm?

Y: It is not metaphysical, per se. For example, Reak contains elements from A-ak. It is the case in both Korea and Japan that A-ak largely expresses the world mostly beyond the human realm for me. In addition, many of my compositions during that period express human beings’ hope, wishes, and religious or metaphysical human desire as we have just discussed. But in recent years, I began to seek humanist fantasy with narrative potential during compositional processes, as is the case for Cello Concerto and Double Concerto. But it is not an absolutely necessary condition. Therefore, even though I composed these pieces with narratives in mind, I wish the pieces to be listened to without consideration for them. There are no depictive elements in music, and also no theatrical [舞台性] elements.

[5.3] N: It is like how not all sounds a bird makes become a birdcall.

Y: Yes. In other words, those imaginations are only captured here and there. As a composer, however, those fantastical stories greatly aid my creative process. I had been composing with pure sounds from the 1960s until the early 1970s. Dimensionen (1971) is one such example of transcending the mortal realm purely through the tones themselves. The realm that is in between the mortal world and the celestial world, or perhaps a contact between the two worlds. There are many other compositions that deal with a topic that is separate from the real world, such as purgatory and a transcendent universe.

But as time passes, I have been more and more influenced by human nature, being a modern citizen, and self-recognition as an artist. Even without my conscious awareness, these ideas are either overtly expressed or buried deep remaining latent in compositions.

[5.4] N: These elements became fantasy and possess a sense of narrative.

Y: Yes. At a deeper level, the purity of a human being, the purity, does not mean statically seeking the calmness of oneself or wanting a sanctuary. My perspective is that purity comes from overcoming all contradictions within the whole. Human society has numerous problems. Human rights abuse is one of them. You cannot reach purity by turning a blind eye to these issues. I was trying to musically represent the process toward this notion of purity. This idea runs through my compositions. This is what is important in my works. The underlying stories are just a guide for the listeners. It is not necessary to know the stories.

6. “The circumstances were the worst, however, the opera I completed in the prison was a comedy.”

[6.1] N: Regarding the opera you had composed while in prison [Die Witwe des Schmetterlings (Butterfly Widow)], at the time, you were in poor health, there was no perspective for its performance, and you weren’t even sure whether you could transport the score outside of the prison cell. How were you able to overcome senses [意識] and compose in these circumstances with one stroke?

Y: The situation was as you have described. The circumstances for my composition space were the worst, and the surroundings were not adequate to even maintain my body temperature. The nutrition was minimal. In a normal circumstance, I should be distant from noises, take enough sleep, and maintain calmness, but none of this was available. I had to lie down on the floor to write on staff paper because there was no desk.

The room, if you could even call it that, is about the size of three to four tatami panels.(11) The window is small and placed high on the wall. The temperature plunges to –10°C in winter. Although it was indoors, without any heaters, there was no warmth. The window was cracked so I had to stick vinyl tape onto it. It did not cover the chinks entirely, so the cold outside air rushes in occasionally. The temperature inside goes below –5°C. I did not have proper clothing and no blankets. I drew a couple of notes and had to thaw my fingers with my breath so that I could grab the pencil again.

[6.2] N: How long did you work under this condition?

Y: About 4 months for that piece, I think? The opera is in one act and takes about one hour to perform. Before I was kidnapped in Germany, the first 10 minutes’ worth was completed. The remaining 50 minutes were composed while in prison. It took 4 months.

[6.3] N: You would not have had any access to a piano during that time.

Y: Never! No piano, no desk, only pencil and paper. And the text. The reason why I could not stop writing the notes even in that situation was that if I die then and there, the music in me also dies. It will vanish. I thought I must leave it behind even just a little bit. Leaving it behind means leaving it in my dream even if I die. It was for myself and never meant for someone else.

Therefore, whether the composition was good or bad was of secondary concern. There existed only freedom to think about my music and to unfold my fantasy. Even though my physical condition was extremely poor, I had the freedom to unfold fantasy. Music gave me such fantasy and I drew it on paper over and over. Therefore, logical thinking was impossible. With that sole freedom and sole pleasure, I could survive the bleak condition despite the complete isolation.

Thankfully, the manuscript left the prison cell for Europe and it was premiered in Europe.

[6.4] N: In Nuremberg, right?

Y: Yes. It is a big deal to have an opera premiered in Europe. On the night of the premiere, I was still in a prison cell. Two months later, I heard the opera following my release. And I was surprised by the fact that the music was not scattered, but well-organized. In addition, the content of the music was comical. It is a comedy. The sections that are meant to be funny surely made people laugh. This instance shows human beings possess the mental capacity to transcend reality.

[6.5] N: It resembles the circumstances regarding Mozart’s late works.

Y: Yes it does.

7. “Ultimately, I think music is human blood and spirit.”

[7.1] N: Toward the end of yesterday’s program note, written by your pupil Tanaka Ken [田中賢], he paraphrased your statement, which he heard from you when you were returning to Japan. “The power of art sprouts from the genuine depth of humanity,” which he recalled from a personal conversation with you. After our conversation today, I can feel the weight of this statement. I would appreciate it if you could give a message to prospective young Japanese composers.

Y: Japan’s economy has grown tremendously and materialistic thinking is getting stronger. Also, foreign cultures, whether they are from the United States or elsewhere, are infiltrating and beginning to dominate. In this social context, it is very dangerous for the youth to think about art uncritically. They should look directly at the current situation and assess the problem through art. The problem each individual faces might still be varied, but there should also be a common ground. One does not pursue composition for wealth or status but does so because one is truly attracted to music. But our time does not allow one to naively enjoy music. A genuine lifeforce, strong message, and persuasiveness are necessary. My composition, Images für Flöte, Oboe, Violine und Violoncello (1968), does not have a direct relationship with social issues, but it still has solid and strong persuasiveness. I don’t think it is completely separate from our current social conditions. Anywhere in the world, one can comprehend the expressive method that comes from diligent and profound human integrity. It will possess the power strong enough to confront the contradiction and absurdity in any part of the World.

[7.2] N: In closing, your compositions reach the listening public through performers, which, I think, is grounded upon a deeply trusting relationship between you and the performers and faith in the performer’s whole personality. But compositions in new media, for example, computer music, do not have much relationship with the performers. What do you think about this aspect? In short, what do you think about computer music?

Y: I belong to an older generation. I have neither the energy nor the ability to compromise or approach the new technological generation. However, as a principle, my perspective on music is that it must contain elements of sanguinity. No matter how much a machine can do, the music coming from the machine is made by the machine. No blood flows through the music. This is a fundamental principle. Music must channel human blood and spirit. Ultimately, I think music is human blood and spirit. To speak naively, a person’s blood and spirit will remain even after my death.

N: Thank you for your time.

Joon Park

School of Theatre & Music

University of Illinois Chicago

1040 W Harrison St

Chicago, IL 60607

joonp@uic.edu

Works Cited

Byeon, Jiyeon, trans. 2003. “The Wounded Dragon: An Annotated Translation of Der verwundete Drache, the Biography of Composer Isang Yun, by Luise Rinser and Isang Yun.” PhD diss., Kent State University.

Kim, Jeongmee. 2004. “Musical Syncretism in Isang Yun’s Gasa.” In Locating East Asia in Western Art Music, edited by Yayoi Uno Everett and Frederick Lau, 168–92. Wesleyan University Press.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray S. Jackendoff. 1996. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. The MIT Press.

London, Justin. 2004. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. Oxford University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Colin Smith. Routledge & Kagan Paul.

Sparrer, Walter-Wolfgang. 1977. Program note for Isang Yun’s Double Concerto world premiere in Berlin, September 26, 1977. Online version available at https://www.boosey.com/cr/music/Isang-Yun-Double-Concerto/4998.

Turner, John W. 2019. “Performing Cultural Hybridity in Isang Yun’s Glissées pour violoncelle seul (1970).” Music Theory Online 25 (2).

Yun, Isang. 1991. “정중동 (静中動): 나의 음악예술의 바탕 [Stillness in Motion: the Foundation of My Musical Art].” In 윤이상의 음악세계; [Musical World of Isang Yun], Seongman Choe and Eunmi Hong, eds. Seoul: Hangil Sa. Originally published in 사회와 사상 [Society and Ideology] 8 (April 1989): 374–87.

Yun, Isang, and Akira Nishimura. 1991. “무한한 우주의 한 끝에서 [At One End of the Endless Universe].” Translated from Japanese to Korean by Jeongbok Seo. In 윤이상의 음악세계 [Musical World of Isang Yun], ed. Seongman Choe and Eunmi Hong. Hangil Sa. Originally published as “無限の宇宙の一端から.” 音楽芸術 [Musical Arts] 42 (1984): 50–61.

Footnotes

* I would like to express sincere gratitude to Susumu Watanabe for helping with my translation. In this translation, parentheses are used to indicate the texts that are present in the interview publication. Square brackets are used to show the translator’s insertion.

Return to text

1. Originally published in a Japanese magazine, Musical Arts [音楽芸術], (September 1984). This interview is translated from Japanese to Korean by Jungbok Seo and published in Sungman Choi and Eunmi Hong, eds., Yun Isang ui Umak Sekye [Musical World of Isang Yun] (Seoul: Hangil Sa, 1991).

Return to text

2. For Yun’s account of the kidnapping, see “The Wounded Dragon: An Annotated Translation of Der verwundete Drache, the Biography of Composer Isang Yun, by Luise Rinser and Isang Yun,” translated by Jiyeon Byeon 2003, 163–234.

Return to text

3. A notable exception is John Turner’s article in Music Theory Online (2019). In this article, Turner analyzes Yun’s composition Glissées pour violoncelle seul (1970) from the perspective of cultural hybridity. Another English source is a published conversation between Isang Yun and Luise Rinser that was translated from German as part of the dissertation by Jiyeon Byeon (2003). The Isang Yun International Society maintains an updated bibliography that includes the list of publications about Isang Yun. The list includes publications in English, German, and Korean. https://yun-gesellschaft.de/en/isang-yun-en/bibliography/

Return to text

4. The word “gagok” [가곡] can mean different musical genres in Korean. It can be a vocal genre in Korean traditional music or art songs written in the 20th century according to the Western style. Based on the context, it is likely that Yun is referring to the former. (I thank the reviewer for the clarification.) In Korean traditional music, Gagok involves a singer with a small ensemble with melodic instruments, whereas Namdo Chang only features a singer and a gosu (고수, a drum player). In addition to instrumentation, the two genres differ in their repertoires and intended audiences. For a brief description and video example of Gagok, see the entry on Gagok in UNESCO’s website for intangible heritage. https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-1657

Return to text

5. There is a difference in pronunciation between Korean and Japanese for the Chinese characters used for the word Hauptton [主要音]. This translation adopts transliteration from the Korean pronunciation, Juyo-um. Transliteration from its Japanese pronunciation is Shoyo-on.

Return to text

6. Yun’s description of Hauptton in this passage evidences his non-objective (i.e., not modeled after physical objects) and fluid (i.e., modeled after the attributes of liquid) view of sound. Similar to merging two water droplets to create a singular larger droplet, Hauptton, a singular tone, is created by merging different sounds (i.e., one important note and the sounds that surround it). The Hauptton, then, “flows” like a stream of water and creates a line, which is a concept different from the Western use of a melodic line.

Return to text

7. The term Hauptklang is used by Yun in his 1985 lecture at Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen to denote “sonic complex” [음복합체, 音複合体], which describes an orchestral use of Hauptton. The Korean lecture script is published in the South Korean left-wing periodical, Society and Ideology [사회와 사상 Sahoe wa Sasang], April 1989 (translated 1991).

Return to text

8. The Japanese original publication provides the first two pages of Yun’s Flute Concerto (1977) as a musical example.

Return to text

9. The Korean translation of this interview erroneously switched the second (“vibrating”) and third stages (“melismatic motion”) of this diagram. And it translates “melismatic” (メリスマ的) as a more abstract compound adjective, “decorative-tonal” (장식음적).

Return to text

10. Walter-Wolfgang Sparrer’s program note for the Double Concerto (1977) provides more context about the folklore. “In the Double Concerto, Yun goes back to a Korean fairy-tale: the harping princess [Jiknyeo, 織女] falls in love with the shawm-playing cowherd [Gyunwo, 牽牛]. The king, annoyed about a choice which is at discord with her social class, bans both of them as stars to the opposite ends of the Galaxy. As an only favour they are allowed to meet once a year, on July 7th, in the middle of the Galaxy.” The cowherd and the weaver girl story originated from Han China and spread throughout East Asia.

Return to text

11. One Japanese tatami panel is about 3 feet by 6 feet in size.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Leah Amarosa, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3989