Embedded Music Theory: Oral Poetry, Rhythmic Language, and Drumming in Sri Lanka*

Eshantha Peiris

KEYWORDS: Translation, Implicit theory, Oral poetry, Vernacular music, Drumming

ABSTRACT: Around the world, music theory is commonly understood as knowledge cultivated by specialist musicians and scholars. It is also assumed to require analytical terminology supplemented with visual representations. However, even in performance traditions less concerned with explicit formulations of musical processes, musical theorizations can be embedded in the minds of the performers and their audiences. This article aims to broaden common understandings of music theory through the lens of orally transmitted ritualistic verses from Sri Lanka, which are sung or recited along with drumming. Versions of these Sinhala verses have been previously published in Sedaraman, J.E. 2008 [1964]. Uḍaraṭa Näṭum Kalāva [The Art of Up-country Dance] (Colombo: M.D. Gunasena). Transliterations and translations of these verses are presented alongside audio recordings of performances (some including video), to illustrate the ways in which the oral transmission and performance of such lyrics involves different modes of theorizing—such as knowledge of how conventional poetic meters can be sung, shared understandings of how to interpret vocables as drum strokes, and the association of different drum timbres with cosmological references. The article provides socio-historical context for the verses, details their form, explains the underlying conventions of versification, and analyzes the relationship between recited syllables and drum strokes, while highlighting the various processes of theorizing that undergird them.

PEER REVIEWER: Garrett Field

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.13

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[0.1] Around the world, music theory is commonly understood as knowledge cultivated by specialist musicians and scholars. It is also assumed to require analytical terminology supplemented with visual representations. However, even in performance traditions less concerned with explicit formulations of musical processes, musical theorizations can be embedded in the minds of the performers and their audience.

[0.2] This article aims to broaden common understandings of music theory through the lens of orally transmitted ritualistic verses from Sri Lanka, which are sung or recited along with drumming. I have chosen to present audio recordings of these verses being performed (some including video), along with transliterations and translations, to illustrate the ways in which the oral transmission and performance of such lyrics involves different modes of theorizing—such as knowledge of how conventional poetic meters can be sung, shared understandings of how to interpret vocables as drum strokes, and the association of different drum timbres with cosmological references.(1) In what follows, I provide socio-historical context for the verses, detail their form, explain the underlying conventions of versification, and analyze the relationship between recited syllables and drum strokes, while highlighting the various processes of theorizing that undergird them.(2)

1. Historical Contexts for Sinhala Oral Poetry

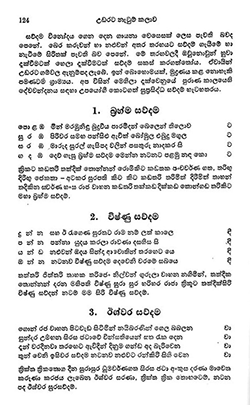

Example 1. A page from J.E. Sedaraman’s “Uḍaraṭa Näṭum Kalāva” (2008 [1964]), showing three Sinhala quatrains (recognizable from the formatting that isolates the syllable at the end of each line) paired with stanzas of mostly non-lexical vocables

(click to enlarge)

[1.1] In 1964, the Sri Lankan hereditary ritualist J.E. Sedaraman published a book in Sinhala, “Uḍaraṭa Näṭum Kalāva” (“the Art of Up-country Dance”), containing the lyrics of hundreds of ritual quatrains that had previously existed in oral tradition (Guruge 2008 [1964], i). As shown in Example 1, he paired many of these quatrains with stanzas of mostly non-lexical vocables, which model rhythm patterns that are to be played on a drum.(3)

Example 2. Muddanave Sunil (center) preparing to lead a group of gäṭa beraya drummers in a Bera Pōya Hēvisi ritual in Mavanella, Sri Lanka

(click to enlarge)

[1.2] Today, the melodies and rhythms that were associated with these verses are largely unknown (along with the protocols for the rituals in which they were once performed). However, there are a few senior hereditary ritualists who recall how some of them were performed. This article draws on two such sets of verses, as performed by hereditary ritualist Muddanave Sunil and his disciples.

[1.3] Muddanave Sunil (Example 2) hails from a caste-based lineage of male dancer-drummer ritualists, which has roots traceable to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.(4) During those centuries, when written material was not readily accessible to the Sri Lankan general populace, many forms of knowledge (including ritual esoterica) were embedded in verse (Sin. kavi) and transmitted orally through singing.(5) The poetic meters and rhyme schemes of these verses likely helped dancer-drummer ritualists to compose and memorize them.(6) Verses such as the ones featured here were sung to drum accompaniment in Sinhalese Buddhist rituals such as the Bera Pōya Hēvisi, which were performed to propitiate deities and bring prosperity to the village while entertaining the attendant devotees with displays of competitive showmanship.(7)

[1.4] The supernatural characters and mythological contexts referenced in these oral verses (e.g., the primordial king Maha Sammata and the deities Sakra and Panchasikha) would have been familiar to listeners from the well-known Buddhist narratives found in ancient literary chronicles such the Mahavaṃsa.(8) This supports the idea that in many cases, “the oral and literate are mixed, interrelated, or overlaid” (Saussy 2016, 59).(9) The mythological stories featured in these verses are also consistent with long-established Sinhalese Buddhist cosmological worldviews, and arguably served to give value and meaning to the dancing, singing, and drumming associated with religious rituals.(10)

[1.5] In these verses, one finds the beliefs that the sound of drums, the traditional drum repertoire played by humans, and the associated dances are linked to the origins of the universe and to the movements of celestial objects, and also that the sounding of drum timbres can serve as a tribute to the supernatural. Taken in the context of the broader repertoire performed by these ritualists, the various numbers mentioned in the verses would have been recognized as having numerological significance, functioning as a form of analogical explanation (Peiris 2020, 171–76). More esoterically, the voicing of particular combinations of long and short syllables(11) in sung and recited texts (and by extension, in drum patterns) was believed to have resonance with astrological movements, thus having potential to trigger positive or negative real-world consequences (Peiris 2022, 9–14).

2. Guide to the Featured Repertoire

[2.1] The first set of sung verses presented here—in Paragraphs 2.2 and 2.5—belongs to the genre known as däkum ata, which is performed as an “offering of sound” (śabda pūjāva) during a Bera Pōya Hēvisi ritual.(12) Each line in these verses contains eighteen poetic morae.(13) Although this repertoire is more closely associated with dawula drums (Example 3), in the recording featured here—split between Video 1 and 2—they are performed with gäṭa beraya drums (Example 4). The performers begin by singing two verses with Sinhala words (Paragraph 2.2, Video 1) using a stock melody commonly heard in the tradition, accompanied by a stock accompaniment pattern on the drums.(14)

Example 3. A dawula drum played by the drummer Lakshman Polgolla (click to enlarge) | Example 4. Gäṭa beraya drummers performing at a ritual in Mavanella, Sri Lanka (click to enlarge) |

Video 1. Two däkum ata verses with Sinhala words (click to watch video) | Video 2. Däkum ata stanzas with bera pada (drum vocable phrases) (click to watch video) |

[2.2] The following is a transliteration and translation of the opening quatrains of a Sinhala däkum ata poem (Video 1), with the names of drum strokes indicated in bold:

tat-ki akura kāṭada namaskārayaki?

jit-ki akura kāṭada namaskārayaki?

ton-ki akura kāṭada namaskārayaki?

nam-ki akura kāṭada namaskārayaki?

Unto whom is the syllable tat a salutation?(15)

Unto whom is the syllable jit a salutation?

Unto whom is the syllable ton a salutation?

Unto whom is the syllable nam a salutation?

tat-ki akura muniduṭa namaskārayaki

jit-ki akura deviduṭa namaskārayaki

ton-ki akura rajuhaṭa namaskārayaki

nam-ki akura guruhaṭa namaskārayaki

The syllable tat is a salutation unto the Buddha.

The syllable jit is a salutation unto the deities.

The syllable ton is a salutation unto the monarch.

The syllable nam is a salutation unto the teacher.

[2.3] The text of this däkum ata piece in which the narrator witnesses/salutes their superiors is reminiscent of the historical practice of däkum (literally, “seeing”) in eighteenth-century Sri Lanka. In this tradition, tenants of a feudal lord would gather to pay respect to him by presenting gifts (Obeyesekere 1967, 220) as part of “a chain of däkum ceremonies binding subordinates of various types to superordinate personnel above them who in turn paid homage to persons of superior rank” (Roberts 2004, 61). Given how the patterning of the pantheon in Sinhalese-Buddhist cosmology can be seen to resemble some of the relational principles of the historical state (Obeyesekere 1966), it is not surprising that this “offering of sound” given to the supernatural Buddha and deities (along with the monarch and teacher) reflects the tribute-paying däkum practices of the mundane world.

[2.4] This is followed by the singing of stanzas that consist of bera pada (drum vocable phrases)—except for the last two words of each stanza, which are Sinhala (Paragraph 12, Video 2).(16) Then begins a sequence of phrase reduction, in which new stanzas are formed using phrases excerpted from the four initial stanzas.(17) The entire set of bera pada stanzas is then sung again, but this time, following each of these stanzas, the timbral-rhythmic pattern modelled by these vocables is replicated on the drums. The piece ends with a concluding wish in Sinhala that forms its own line of verse.

[2.5] The following is a transliteration (and translation, where applicable) of the vocable stanzas of the däkum ata poem (Video 2), with the names of drum strokes indicated in bold:

tat jek kinaṃ takaṭa kaḍataka jeṃgu jeṃ takaṭa

tat takaṭa – muni dakin (1)(18)

[vocables. . .] – witness(19) the Buddha

jit jek kinaṃ takaṭa kaḍataka jeṃgu jeṃ takaṭa

jit takaṭa – devi dakin (2)

[vocables. . .] – witness the deities

ton jek kinaṃ takaṭa kaḍataka jeṃgu jeṃ takaṭa

ton takaṭa raja dakin (3)

[vocables. . .] – witness the monarch

nam jek kinaṃ takaṭa kaḍataka jeṃgu jeṃ takaṭa

nam takaṭa guru dakin (4)

[vocables. . .] – witness the teacher

tat takaṭa muni dakin (1’)

jit takaṭa devi dakin(2’)

ton takaṭa raja dakin (3’)

nam takaṭa guru dakin (4’)

[vocables. . .] – witness the Buddha

[vocables. . .] – witness the deities

[vocables. . .] – witness the monarch

[vocables. . .] – witness the teacher

tat dakin jit dakin

ton dakin nam dakin

Witness tat; witness jit;

Witness ton; witness nam

muni(20) dakin (1’’) devi dakin (2’’)

raja dakin (3’’) guru dakin (4’’)

Witness the Buddha, witness the deities

Witness the monarch, witness the teacher

dakin dakin matu met munituman dakin

Witness, witness, witness the Maitreya Buddha in the future.(21)

[2.6] The second set of sung verses (transliterated and translated at the end of this article in Paragraphs 6.1–6.8, and performed by Muddanave Sunil in Audio 1–8; see section 6 below) consists of eight verses that belong to the category of upat kavi (origin verses). Upat kavi are rarely performed today; however, in the past they were often sung of chanted as introductory prefaces during rituals (Muddanave Sunil, pers. comm.). They typically detail the (often supernatural) origins of things of spiritual significance, such as deities (Kulatillake 1976b, 3–4), types of repertoires (Karunaratne 2008, 23; Sykes 2018, 58–59), and drums (Sedaraman 2008 [1964], 37–42).

[2.7] Verses 1–3 (Audio 1–7) of the upat kavi ascribe primordial, supernatural origins to the four primary drum timbres associated with gäṭa beraya and dawula drums. Verses 4–7 (Audio 4–7) each focus on one of these respective drum timbres, and are paired with a stanza of vocables that is recited and imitated on the drum one phrase at a time. Verse 8 (Audio 8) offers a conclusion.

3. Theories of Poetic Meter

[3.1] As with many pre-modern forms of poetry, these verses were intended to be sung and listened to, not published and read silently. Theories of poetic meter and rhyme scheme have been part of literary discourse for centuries (Hallisey 2003, 723–38); the value given to these ideas of sonic patterning is reflected in the fact that sung Sinhala poetry was prized as much for its sonic aesthetics (ṣ́abda rasa) as its semantic aesthetics (artha rasa).(22)

[3.2] The Sinhala verses in both the däkum ata (Paragraph 2.2) and the upat kavi (Paragraphs 6.1–6.8) follow the cyclic format known as sivpada (Sin. quatrain), in which each line of poetry contains an approximately equal number of morae and ends with eli-väṭa (Sin. rhyming/assonant phonemes). As mentioned, the Sinhala däkum ata verses (Paragraph 2.2) contain eighteen morae per line. As defined in the thirteenth-century poetic treatise Elu Saňdäs Lakuna (“Characteristics of Sinhala Poetic Meter”), this poetic meter is named Samudraghōṣa (Sin. sound of the ocean) (Sorata 2004, 56). While the Samudraghōṣa poetic meter has been used in many genres of Sinhala versification (Makulloluwa 2009, 33–49), musicologist C. de S. Kulatillake has observed that it is rare in ritual repertoire (Kulatillake 1976b, 9), making this example rather unusual. The upat kavi Sinhala verses (at the end of this article) feature a variation on the sivpada format: while each line contains twenty-six morae, following the line-ending rhyme at the end of lines 1 and 3 of the quatrain, there is an extra two-morae word that leads into the next line.(23) In keeping with traditional performance practice, Muddanave Sunil’s performance of these verses includes introductory drumming before each verse is sung and a drummed interlude between the second and third lines of the stanza.

[3.3] While the poetic meter itself provides the nominal quantity of morae in each line, in sung performance, certain prescribed syllables are elongated with a melisma, for example in the rhyming syllable at the end of each line in the Sinhala verses featured here. These caesurae that are added into the poetic meter during performance are known as yati. While this sung elongation of syllables veils the rhythm implied by the poetic meter, the rhythmic structure of the melody remains closely tied to the poetic meter, as the melody (Sin. tanuva) needs to accommodate all the syllables in the text. While oral poets may have not consciously engaged with literary theories of yati when deciding which syllables to elongate in performance, the act of choosing which stock melody to use to sing a verse requires an implicit analytic understanding of how the morae in the poetic text are grouped.

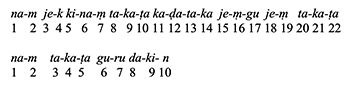

Example 5. The fourth drum-syllable stanza of the däkum ata piece (Video 3, transcribed in Example 6) written as a couplet (each line starting with the syllable nam), with the morae numbered according to the conventions of Sinhala poetic scansion to show the irregular patterning

(click to watch video)

[3.4] In contrast with the Sinhala sivpada verses, which contain a similar number of morae in each line, the patterning of morae in the bera pada stanzas is irregular; this is particularly evident in the recited texts that are paired with the upat kavi (transliterated in Paragraphs 6.4–6.7). However, such irregularity can also be constrained; for example, in the däkum ata, all the sung stanzas of bera pada share the same (irregular) morae pattern—namely, twenty-two morae in the first line and ten in the second, as shown in Example 5. This is to be expected since each stanza only differs by one “word,” but it also suggests that the bera pada have likely been composed with an irregular poetic meter in mind. This irregularity is particularly apparent in performance (Video 3) because the musical rhythm corresponds closely to the syllabic rhythm inherent in the text, with one mora performed as one musical pulse (except for the four morae ka-ḍa-ta-ka, which are sung within two pulses).(24) Example 6 is an approximate transcription of the fourth drum-syllable stanza of the däkum ata (as sung to a stock melody by Lakshman Polgolla), followed by a transcription of the replication of that syllabic rhythm on the gäṭa beraya drums. (The transcription key for the drum strokes is shown in Example 7). In contrast with the bera pada of the däkum ata (Paragraph 2.5, Video 3), the bera pada in the upat kavi (Paragraphs 6.4–6.7, Audio 4–7) are performed in a more metrically free manner, although the relative lengths between the shorter syllables (one mora) and longer syllables (two morae) are largely maintained.

Video 3. The fourth drum-syllable stanza (bera pada) of the d�kum ata piece. (click to watch video) |

Example 6. Approximate transcription of the fourth drum-syllable stanza (as sung to a stock melody by Lakshman Polgolla), followed by a transcription of the replication of that on the gäṭa beraya drums

(click to enlarge)

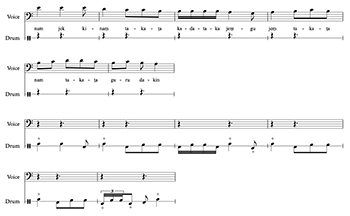

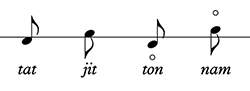

Example 7. Transcription key for the four primary drum strokes/timbres of the gäṭa beraya drum

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] It should be noted that not all historical Sinhala poetic meters feature the equal quantities of morae characteristic of sivpada quatrains. In contrast, poetic meters labelled as gī (blank verse) were known for having different amounts of morae between lines in a couplet (Kulatillake 1976b, 3). Further, there is historical precedent for regular sivpada verses being paired with irregular gī verses,(25) suggesting that the pairing of Sinhala sivpada quatrains with irregular non-lexical phrases might indeed have been following an established technique of poetry composition.

4. Spoken syllabic models for drumming

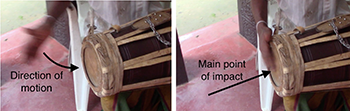

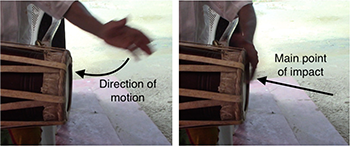

[4.1] On two-headed drums such as the gäṭa beraya, each drumhead can be struck in a way that allows it to resonate or struck in a way that dampens the vibration; ritualist drummers recognize these four strokes as producing four distinct timbres (Examples 6 and 7). These four strokes (and associated timbres) are termed “seed syllables” (bīja akṣara) and they are named as follows: tat—a damped stroke on the lower drumhead (Example 8; see also Video 4), dit (or dik or jit)—a damped stroke on the higher drumhead (Example 9; see also Video 5), ton (or tom or toṃ)—an undamped stroke on the lower drumhead (Example 10; see also Video 6), and nam (or naṃ)—an undamped stroke on the higher drumhead (Example 11; see also Video 7).(26) In terms of their relationship to the timbres that they index, the labels tat, dit, ton, and nam could be understood as onomatopoeic icons: for example, the names of the two damped strokes (tat and dit) end with oral stops (i.e., consonants that stop all airflow), the names of the undamped/resonant strokes (ton and nam) end with nasals (i.e., stopped consonants that allow air to continue through the nose), and the name of the lowest pitched timbre (ton) has a “deeper” vowel (i.e., a vowel with a relatively low second formant) than the others.(27) The videos linked in the captions of Examples 8–11 show repeated iterations of these four strokes being performed on the gäṭa beraya by Muddanave Sunil.

Example 8. Playing tat (click to enlarge) | Example 9. Playing dit (click to enlarge) |

Video 4. The drum stroke tat, demonstrated by Muddanave Sunil. (click to watch video) | Video 5. The drum stroke dit, demonstrated by Muddanave Sunil. (click to watch video) |

Example 10. Playing ton (click to enlarge) | Example 11. Playing nam (click to enlarge) |

Video 6. The drum stroke ton, demonstrated by Muddanave Sunil. (click to watch video) | Video 7. The drum stroke nam, demonstrated by Muddanave Sunil. (click to watch video) |

[4.2] While the upat kavi translated here (at the end of this article in Paragraphs 6.1–6.8) ascribe the four seed syllables primordial, supernatural origins, the däkum ata verses (Paragraph 2.2) prescribe these syllables—tat, dit, ton, and nam—as ritual salutations to the Buddha, deities, monarch, and teacher respectively. For reasons perhaps linked to their ritual significance, ritualists also use the four seed syllables as a basis for classification, categorizing pieces in the drum and dance repertoire based on the drum timbre with which they begin (Sedaraman 1966, 17).

[4.3] As with many drumming traditions from around the world, musical phrases played on the gäṭa beraya drum are represented by spoken phrases of bera pada (drum vocable phrases), which function as “oral notation.” While the four primary drum timbres are referred to in the däkum ata and upat kavi Sinhala verses by their seed syllable names (i.e., tat, dit, ton, and nam), spoken bera pada draw on a much larger vocabulary of drum vocables—which for the most part index the same four primary drum timbres.(28) This extended vocabulary of spoken syllables is known as garbha akṣara (Sin. womb syllables).(29) Like the names of the seed syllables, the spoken sounds of many womb syllables loosely resemble the timbres of the corresponding gäṭa beraya drum strokes, however, the resemblances are far from systematic.(30)

[4.4] How do gäṭa beraya drummers translate recited bera pada into strokes on the drum? One strategy is simply to draw on one’s existing knowledge gained from oral and aural assimilation and/or explicit teaching. For example, ta-ka-ṭa ku-jiṃ is a typical drum vocable phrase (comprised of womb syllables) known by all gäṭa beraya drummers. Trained drummers would know from experience to play this phrase on a drum using the stroke sequence tat-dit-dit ton-nam; i.e., using all four seed syllable timbres.(31) In contrast, the bera pada that follow the däkum ata Sinhala verses contain drum vocables associated with dawula drums (e.g., jeṃgu jeṃ) as well as actual Sinhala words with referential meaning (e.g., guru dakin, meaning “witness the teacher”), and the bera pada that follow the upat kavi Sinhala verses use non-lexical phrases that are mostly not part of the established drum vocabulary (e.g., kunḍala kura kata). In these cases, interpreting these timbral-rhythmic phrases as drum strokes on a gäṭa beraya requires informed creativity.

[4.5] By now, it should be clear to readers that the Sinhala verses in the däkum ata and upat kavi poems embed conventional syllable structures (through poetic meter and rhyme scheme) and analogical explanations (through relating drum strokes to the supernatural), and that the durational patterning of the recited bera pada models the rhythm patterns that are to be replicated on the drum. These are all techniques of composition (with underlying theories) that were employed during the creation of this repertoire. However, the existence of unconventional bera pada (such as muni dakin and kunḍala kura kata) that need to be creatively reinterpreted as drum strokes/timbres raises the following question: how might gäṭa beraya drummers be actively theorizing while performing this repertoire, especially if they are hearing the recited bera pada for the first time while a ritual is in progress (as is sometimes the case)?

Video 8. Excerpt from the d�kum ata stanzas.

(click to watch video)

Example 12. Transcription of an excerpt of the däkum ata stanzas, showcasing the imitation of spoken syllables as drum timbres, with the seed syllable names in bold

(click to enlarge)

[4.6] Although not all music scholars agree that theories can be non-verbal, tacit, and/or implicit,(32) we can think of the drum patterns played here as an outcome of theorizing if we define a theory as, “a conception or mental scheme of something to be done, or of the method of doing it; a systematic statement of rules or principles to be followed” (OED online, s.v. theory). To be able to create a drum pattern based on a spoken phrase such as “guru dakin,” a drummer must access a schema—learned through observation during lessons and performances—that suggests appropriate options for which drum strokes to use to play the pattern. Methods for doing this are not explicitly taught (to my knowledge); however, I have observed that, in many cases where spoken syllables precede drumming, gäṭa beraya drummers consistently interpret certain phonemes as modeling particular drum timbres, as evident in the following excerpt from the däkum ata stanzas (Video 8, transcribed in Example 12).

[4.7] The second word in each line— takaṭa—is, as mentioned, a standard motif that is typically played on the drum using the stroke sequence tat-dit-dit, indicated with box 1 in Example 12. Unsurprisingly, the first words in each line—tat, jit, ton, and nam—are respectively interpreted as the four primary drum strokes that they normally index, as indicated in Example 12 with boxes 2, 3, 4, and 5.(33) Where the drummers need to creatively access their shared schematic knowledge is when interpreting the Sinhala phrases “muni dakin,” “devi dakin,” “raja dakin,” and “guru dakin.” Some noteworthy techniques are as follows:(34)

- The sound “in” (found in the word “dakin”) is played as an undamped stroke on the high drumhead (i.e., nam), indicated with box 6 in Example 12.

- The vowel “u” is played as an undamped stroke on the low drumhead, indicated with box 7 in Example 12.

- The consonant “r” is played as a quick double stroke (played by rotating the wrist) on the high drumhead, indicated with box 8 in Example 12.

[4.8] As with the names of seed syllables, the above-mentioned syllables could be considered icons, in that the drum strokes imitate the timbres of the phonemes. For example, “in” features a “bright” vowel (with a relatively high second formant) with a nasal consonant and is played on the higher drumhead whose overtones give it a “nasal” quality. And “u” is a “deep” vowel (with a relatively low second formant) which is imitated on the lower drumhead. I posit that the conceptual mechanism that enables this creative translation from spoken phrase to drum phrase is indeed a theory shared among practitioners, albeit an unverbalized, implicit one.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] Through my transliteration, translation, and recording of Sinhala däkum ata and upat kavi verses, I have demonstrated some of the ways in which musicians in Sri Lanka have employed established techniques of versification to embed and disseminate ritual knowledge. I have further shown how every step in the process—from composition to performance—has involved musicians making decisions about how best to communicate this knowledge through the medium of patterned sound, in ways familiar and stimulating to the target audience. Given that these decisions involve choosing between culturally acceptable alternatives, I argue that these processes are all forms of theorizing, although they may vary in their levels of formalization. (35)

[5.2] As with the Middle East, East Asia, and Europe, South Asia is home to speculative music theoretical traditions of ancient origin (Rowell 1992) and to sophisticated traditions of concert musics (such as Hindustani and Karnatak music), which carry their own discourses and evolving conventions of composition. In contrast, the theory-like phenomena highlighted here—such as the use of poetic meters and rhyme schemes, the use of analogical explanations, and the translating of spoken vocables into drum rhythms and timbres—may seem far removed from the philosophical analyses of professional scholars. However, I posit that taking seriously vernacular traditions of functional musics—such as Muddanave Sunil’s ritual-based music—will enable us to look beyond the cultural and intellectual prestige of explicitly formulated theories of art music to become more aware of the diverse ways in which humans have sought to prescribe, document, transmit, describe, and explain their musics as an integral and consistent part of their worldviews. This will afford us a more complete picture of what music theorizing can encompass.

6. Bījākṣara Upat Kavi (Origin Verses of Seed Syllables)(36) (Audio 1–8)

Audio 1

[6.1] Origin Verse 1 [Audio 1]

sadā sapiri maha sammata raja saha – viṣnu da isuru suran – ema

vidāna kara giya sudam sabhāvaṭa – näṭum balana vilasin

edā esakpura divanalu pirivara – gāndharva esuran – dev

soňdā enaradevi piligena divanalu – nerta paṭan ganimin

The eternally bountiful king Maha Sammata(37) and (the elite deities) Vishnu and Ishwara

ordered the assembly of devotees to observe the dances;

that day the assembly of divine dancers and musicians in the abode of the deity Sakra

began the dances and presented them from the deities to the humans

Audio 2

[6.2] Origin Verse 2 [Audio 2]

paṃcasikhaya devi ran berayak gena (x2) – sak raja peradiga mayi – siṭa

saṃkanāda pim̌ba takāre mul koṭa (x2) –tatyana tāle yodayi

punsaňda men siṭi sammata raja eya (x2) – däka sit prīti unayi – ema

sundara rajugē dakunu pasin siṭa (x2) – sabba bamunu uganiyi

The deity Panchasikha took a golden drum (while Sakra stayed in the east) and

blew the conch shell beginning with [the sound] “ta,” using [creating?] the rhythm “tat;”

King Maha Sammata—who looked like the full moon—saw this and was delighted;

[the rhythm of tat] was learned by the brahmin named Sabba who stayed on the right side of the beautiful king

Audio 3

[6.3] Origin Verse 3 [Audio 3]

onna assannaṭa mula siṭa silpaya nertaya mula mehemayi – tava

binna novannaṭa dahamē saha isivākiyavala livivayi

sanna solō gī vena vena kīvat (x2) – nerta mulē mehemayi – ema

sammata mula siṭa pävatī gena ena (x2) – häṭiyaṭa pada getuvayi

Listen from the very beginning; this is the origin of the craft of dancing.

Ishwara wrote it down so that the teachings would not be further divided/destroyed

Though slokas, songs, and commentaries may say otherwise, this is the true origin of dance

The verses/patterns were woven together in the way that they have come down since the primordial time of king Maha Sammata

Audio 4

[6.4] Origin Verse 4 (Tat) [Audio 4]

sǟma silpa dat sabba bamunu tema maha sammata muladī –dev

lōma suran kala nertaya rajuhaṭa däkum tabā pähädī

sōma dinaya sita näkata edā tava kaṭaka rǟ sada pǟdī –meya

pǟma palamu tavatatyana padayaṭa varna noyek , bändī

The brahmin Sabba who knows every art, presented to the king Maha Sammata as a homage,

the dance that pleased the entire world of deities;

it was an auspicious time when the crescent moon came out on the night of the zodiac period of Cancer

when this happened, other colors [timbres?] became tied to the first sound “tat”(38)

[bera pada:]

takkrutākiṭa talaṃgu tākiṭa(39)

teyi teyi tarkiṭa krata hrata targat

takitala hatitat hatakita taharta tā

Audio 5

[6.5] Origin Verse 5 (Dik) [Audio 5]

kālacandra saha mitra nämati yasa cūlōdara bamunā – devu

sāla näṭum sata palamu ugattā sabba bamunu vetinā

pālā däkumaṭa ravidina kuṃburäsa anurē näkatada yodā genā – soňda

tālaya dik yana pada kara bhēdaya nätuwayi varna yenā

Brahmins named Chūlōdara, Kālachandra, and Mitra

first learned seven divine dances from the brahmin Sabba

paying homage on the day of the sun (Sunday); at the auspicious astrological time “anura” during the zodiac period of Aquarius

they danced divisions [variations?] with color [other timbres?] based on the tone “dik”

[bera pada:]

diṃga draviḍa diḍa

dika dadita natari

dīna dōmat

dikatari gurulaḍi

druta dhedī dikuňdat

jikutaku jit

Audio 6

[6.6] Origin Verse 6 (Toṃ) [Audio 6]

dawul bhēri horanǟ nāsinnam däkki mepasa gattayi – räňgu

lakal mepas dena gadam̌ba suransē naralova nertakalayi

nimal niriňdu haṭa kividina tunaturusiharäsa yodä genayi –mema

tumul ṣilpa pada toṃ yana tālaya varna rajuṭa pǟvayi

Taking the five instruments—dawula drum,(40) other drums, horanǟwa,(41) nāgasinnam,(42) and däkkiya(43) drum

The five divine musicians presented the dances in the human world

It was given to the pure king, on the day of Mars (Tuesday) at the triple auspicious time of “uturupal,” “uturupuṭupa,” and “utursala” during the zodiac period of Leo

Through this whole art, the characteristics of the rhythm of “toṃ” were danced/showed to the king

[bera pada:]

toṃ tari toňga tari

tōdikitānam

tolīkēta toňga

khētājavitā

vēḍunu ruttuṃ

toṃtula trayi trayi

toṃ naṃ gitkiṭa toṃ

Audio 7

[6.7] Origin Verse 7 (Naṃ) [Audio 7]

ṣabda paṃca pada paṃca tāla saha sural abhina yodalā – tava

ladda esilpaya budadina mulayada mituna räsin lakalā

sudda me silpaya maha narapati saha pirisaṭa pennālā – naňda

ṣabda gigum kara naṃ yana tālaya siv väni vara gasalā

The genres surala, abhina, the five rhythms and tunes, and other sonic offerings

were presented on the day of Mercury (Wednesday) at the auspicious astrological time of “mula” during the zodiac period of Gemini

This pure art was shown to the great leader and their crowd

The sound of the tone “naṃ” reverberated when hit (played) for the fourth time

[bera pada:]

naňgina bhrana gidiḍa

kunḍala kura kata

kukuňda kukuňda naṃga

krallat takkaḍa

neyina kalēnaṃ

arula kirula naṃgaḍa naṃ

Audio 8

[6.8] Origin Verse 8 [Audio 8]

tat jit ton nam bhēdat ättē vattaṃ satara tamā – pera

suran atin maha sammata mula siṭa genā sabba utumā

suran rajun saha budun mudun koṭa vena vena bhēda yomā – meya

bälun satun sura sit pinavannaṭa häkivē danu niyamā

The classification of [drum strokes] tat, jit, ton, andnamis part of the four sections [of a ceremonial drumming piece?]

Was brought by Sabba from the hands of the deities in the primordial times of king Maha Sammata

Different sections are dedicated to the deities, to the king, and to the Buddha

Know that all being who witness this will have their minds gratified

Eshantha Peiris

University of British Columbia

Department of Music

Vancouver, BC,

Canada

eshantha@mail.ubc.ca

Works Cited

Blum, Stephen. 2023. Music Theory in Ethnomusicology. Oxford University Press.

Brown, Robert. 1965. “The Mṛdan̄ga: A Study of Drumming in South India.” PhD diss., University of California at Los Angeles.

Deegalle, Mahinda. 2006. Buddhism, Conflict and Violence in Modern Sri Lanka. Routledge.

Guruge, Ananda W.P. 2008. [1964]. Introduction. In Uḍaraṭa Näṭum Kalāva [The Art of Up-country Dance], by J.E. Sedaraman, i-v. M.D. Gunasena.

Hallisey, Charles. 2003. “Works and Persons in Sinhala Literary Culture.” In Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia, edited by Sheldon Pollock, 689–746. University of California Press.

Karunaratne, Udeni Kudabanda. 2008. Uḍaraṭa Nartana Shilpīngē Pärani Gāyanā [The Old Songs of Up-country Dancers]. S. Godage and Brothers.

Kulatillake, C. de S. 1976a. A Background to Sinhala Traditional Music of Sri Lanka. Department of Cultural Affairs. https://dds.crl.edu/crldelivery/13278

—————. 1976b. Metre, Melody, and Rhythm in Sinhala Music. 2. Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation. https://dds.crl.edu/item/94776

—————. 2013. [1982] Daha-ata Vannama [Eighteen Vannamas]. Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

Makulloluwa, W. B. 1996. [1962] Hela Gī Maga [The Way of Sinhalese Song]. Department of Cultural Affairs.

—————. 2009. [1969] Samudurugosa Virita [the Samudurugosa Meter]. In Mānavavaṃṣ́a saṃgīta vimarṣ́ana [Ethnomusicological Investigations], edited by P.D. Ranjith Fernando, W.A. Nishoka Sandarawan, and Dhammika Dissanayake, 33–49. University of Visual and Performing Arts.

Obeyesekere, Gananath. 1966. “The Buddhist Pantheon in Ceylon and its Extensions.” Anthropological Studies in Theravada Buddhism 13: 1–26.

—————. 1967. Land Tenure in Village Ceylon. Cambridge University Press.

Oxford English Dictionary. n.d. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://www.oed.com

Paranavitana, Senarat. 1956. Sigiri Graffiti. Oxford University Press.

Peiris, Eshantha. 2020. “The Gäṭa Beraya Drumming Tradition of Sri Lanka.” PhD diss., University of British Columbia. https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0394161

—————. 2022. “Vocal Models and Musical Rhythm in Sri Lanka.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 10 (1). https://journal.iftawm.org/previous/2022-volume-10-number-1/10-1-peiris-2/

Reed, Susan Anita. 2010. Dance and the Nation: Performance, Ritual, and Politics in Sri Lanka. University of Wisconsin Press.

Roberts, Michael. 2004. Sinhala Consciousness in the Kandyan Period 1590s to 1815. Vijitha Yapa Publications.

Rowell, Lewis. 1992. Music and Musical Thought in Early India. University of Chicago Press.

Saussy, Haun. 2016. The Ethnography of Rhythm: Orality and its Technologies. Verbal Arts: Studies in Poetics. Fordham University Press.

Sedaraman, J.E. 1966. Uḍaraṭa Tāla Shāstraya [The Art of Up-country Tala]. Gunasena.

—————. 2008 [1964]. Uḍaraṭa Näṭum Kalāva [The Art of Up-country Dance]. M.D. Gunasena.

Sorata, Weliwitiye. 2004 [1963]. Elu Saňdäs Lakuna [Characteristics of Sinhala Poetic Metre]. Vidyodaya Pirivena Past Pupils Association.

Sykes, Jim. 2018. “On the Sonic Materialization of Buddhist History: Drum Speech in Southern Sri Lanka.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 6 (2). https://iftawm.org/journal/oldsite/articles/2018a/Sykes_AAWM_Vol_6_2b.html

Wolf, Richard K. 2014. The Voice in the Drum: Music, Language, and Emotion in Islamicate South Asia. University of Illinois Press.

Footnotes

* This article would not have been possible without Muddanave Sunil—a living repository of ritual knowledge, Pabalu Wijegoonawardane—who facilitated the audio recording with Muddanave Sunil in Sri Lanka and provided valuable feedback on the translations, and Isuru Kumarasinghe, who made the audio recordings. Special thanks are also due to Garrett Field, for his insightful suggestions offered through the collaborative peer review process.

Return to text

1. I have digitally edited the recordings in collaboration with the performer Muddanave Sunil, to best represent the way he wanted them to be heard. Transliterations are based on the ALA-LC romanization table for Sinhala: https://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/sinhales.pdf. Bear in mind that some “a” vowels are pronounced as “a,” whereas other “a” vowels are pronounced as a shwa; Sinhala orthography does not distinguish between these two sounds.

Return to text

2. My observations here complement the extended arguments that I have made elsewhere regarding the relationship between sung poetry, drum vocables, and drumming in Sri Lanka (Peiris 2022).

Return to text

3. Examples of such verse-pairs can be found in the verse-genres named tālama, savudama, and däkum ata. The following is a translation of the introductory blurb at the top of the page in Example 1:

“We also see that the savudama is a type of singing that brings amusement. We see that there was a practice among drummers and dancers of singing and dancing savudamas competitively. In these competitions they formed the savudamas so that they could upstage each other. From these we get the änumpada (verses of criticizing) repertoire found in upcountry [i.e., central Sri Lankan] villages. Many of these are too provincial/unsophisticated to even be published. We show here sixty-four famous savudamas that were used in deity worship in ancient times.”

Return to text

4. For socio-historical context on this caste-based lineage, see Reed (2010, 79–84). I do not use the caste name here, as many ritualists today prefer to distance themselves from its historically negative connotations.

Return to text

5. As musicologist C. de S. Kulatillake notes, “even the fundamentals of music and also dance have been laid down in sivpada [quatrain] verses” (1976b, 5).

Return to text

6. As anthropologist Michael Roberts argues, “in its purely oral modality of chant, song or poem, the communicative power of these messages [. . .] derives from their tune. [. . .] The simple metrical representation was a mnemonic device that assisted memorisation of extended tracts of poetry” (2004, 23). For a summary of broader ethnomusicological perspectives on processes of formulaic “oral composition,” see Blum (2023, 91).

Return to text

7. Sinhalese-Buddhism (i.e., the practices of Buddhists of Sinhalese ethnicity) in Sri Lanka is generally perceived to include two strands of belief: a high regard for the canonical Buddhist doctrine as recorded in ancient Pali texts and belief in supernatural powers/beings that directly impact one’s fortunes in this life. Sinhalese Buddhist cosmology is by no means a unitary belief system, but rather an umbrella term that is useful for referring to the many layers of historical convictions that have driven the actions of Sinhala-speaking Buddhists in Sri Lanka. For contrasting interpretations of the history and focus of Bera Pōya Hēvisi rituals, see Sykes (2018, 47–48) and Peiris (2020, 178–79).

Return to text

8. The Mahavaṃsa—which chronicles histories of early rulers—was first compiled around the sixth century. Even though the Mahavaṃsa and other chronicles are “literary” in nature, and they contain verses in the scriptural language Pali rather than a commonly understood vernacular dialect, it is likely that their contents were circulated and interpreted orally in the context of Buddhist preaching in Sri Lanka over the centuries (Deegalle 2006, 8).

Return to text

9. For a discussion of some of the contrasting scholarly views on orality, aurality, and literacy, see Blum (2023, 52–53).

Return to text

10. For translations of a variety of other historical Sinhala oral verses, see Kulatillake (1976a, 19–25, https://dds.crl.edu/crldelivery/13278)

Return to text

11. Sinhala is a mora-timed language. A short syllable is one mora long, while a long syllable takes up two morae.

Return to text

12. Another version of this däkum ata poem is transliterated in Sykes (2018, 60–61). As Sykes noted in a Bera Pōya Hēvisi ritual of a different regional tradition, “the drumming alternates between verbally recited drum speech, drum words played on a drum (with no hint of a pulse), and sung poetry in a mixture of Sinhala, Sanskrit, Pali, and a Tamil-sounding drum language” (ibid., 3).

Return to text

13. My English translation also contains eighteen morae per line; however, this is of little significance since English is a stress-timed (rather than mora-timed) language.

Return to text

14. The unrehearsed nature of the recorded performance is typical of such rituals. The loosely coordinated timing of the drumming is characteristic of ritual drumming and could be considered an aesthetic choice.

Return to text

15. I have translated namaskāra as “salutation” rather than “greeting” to emphasize the superordinate status of those being greeted.

Return to text

16. While Muddanave Sunil is leading the ensemble, the performance of this däkum ata is led by Lakshman Polgolla.

Return to text

17. I draw attention to this reducing phrase structure in my transliteration, for example, indicating progressively shorter versions of the same phrase as (1), (1’), and (1’’) respectively. Similar techniques of phrase reduction are also found in traditional drum compositions (Peiris 2020, 75–79), and were also likely applied spontaneously by performers in the past (Kulatillake 2013 [1982], 14).

Return to text

18. I have included numbers here to draw attention to the structure in which the phrases are increasingly truncated in successive verses. For example, (1’) is a truncated version of (1), and (1’’) is an even shorter version.

Return to text

19. “Witness” (dakin) is the verb form of the gerund “appearance” (däkum). Given that däkum could refer to a tribute-paying ceremony, dakin could also be translated as “pay tribute to.”

Return to text

20. During the second time around, the order of words becomes switched to the following, likely by mistake: raja dakin, muni dakin, devi dakin, guru dakin.

Return to text

21. In Buddhist eschatology, Maitreya Buddha is the future Buddha of this world.

Return to text

22. The Elu Saňdäs Lakuna has been influential among poets since the thirteenth century. For an overview of the different types of poetic meters that have been historically used for Sinhala poetry, see Kulatillake (1976a, 1–14) and Makulloluwe ([1962], in Sinhala).

Return to text

23. For this recording, Muddanave Sunil chose to showcase a few different melodies. Fitting the text to the melody used for Verse 2 requires that the first part of each line is sung twice, which distorts the nominal number of morae per line.

Return to text

24. In other words, most of the short syllables last for one musical pulse, and the long syllables last for two pulses.

Return to text

25. For example, Sīgiri graffiti nos. 247 and 661 (scribbled by medieval tourists at the ruined palace complex of Sīgiriya in Sri Lanka) both contain a sivpada verse followed by a gī verse (Paranavitana 1956, clxxxviii).

Return to text

26. On the gäṭa beraya, the damped strokes do not have an identifiable pitch (i.e., the overtones produced are inharmonic); however, even damped strokes on the two drumheads can perceived as producing respectively “lower” and “higher” sounds because they vibrate at different fundamental frequencies. The undamped (i.e., resonant) drum strokes do have identifiable pitches; however, these pitch identities are not so strong that (for instance) they need to match the pitch of singing; compositionally, undamped drum strokes are treated as timbral rather than pitch categories. When playing a damped stroke on one drumhead, drummers often simultaneously dampen the other drumhead.

Return to text

27. These names tat, dit, ton, and nam are also used to refer the four primary strokes on other drums historically used in Sri Lanka such the dawula, tammäṭṭama, mattalam, and tavil; they also “appear in recognizable form in all the diverse styles of barrel drumming, ancient and modern, all over India” (Brown 1965, 105), and are similar to the drum syllables ta, di, tom, and nam found in the thirteenth-century Sanskrit treatise Saṅgītaratnākara and the tenth-century Tamil treatise Mattaḷaviyal.

Return to text

28. As with many other South Asian performance traditions, this repertoire of drum vocable phrases is shared by dancers—who use them to represent combinations of dance movements.

Return to text

29. While womb syllables are commonly understood to index the timbres associated with the four seed syllables, Sedaraman defines sixteen different womb syllables that are to be sounded using subtly different playing techniques (1966, 7–8).

Return to text

30. For a general discussion regarding the connection between mnemonic syllables and percussion timbres in the broader context of South Asia, see Wolf (2014, 20–22). Speaking of vocables more generally, Blum notes that “names with an iconic relation to the sound frequently stand for both the sound and how to produce it,” arguing that […] sets of names for timbres linked to actions result from analytical thinking that labels attributes of an event’s successive phases in combinations musicians need to learn and remember” (2023, 111).

Return to text

31. This explanation is a bit oversimplified; while ta-ka-ṭa is indeed performed with the timbre sequence tat-dit-dit, the two dit strokes are performed with different hand motions (Peiris 2020, 67–69).

Return to text

32. For a discussion on the various types of theorizing recognized by ethnomusicologists, see Blum (2023, 52–59).

Return to text

33. A similar process of interpreting versions of the seed syllables as primary drum strokes happens in the non-lexical stanzas that follow the upat kavi verses. For example, since Origin Verse 4 (Paragraph 6.4) is about the stroke tat, many of its vocable phrases for reciting (including the initial and final syllables) begin with ta or tā (underlined in the transliteration); these syllables would be interpreted on the drum with a tat stroke. Since Origin Verse 5 (Paragraph 6.5) is about the stroke dit (jit), many of its vocable phrases for reciting (including the initial and final syllables) begin with d or j; these syllables would be interpreted on the drum with a dit stroke (underlined in the transliteration). Since Origin Verse 6 (Paragraph 6.6) is about the stroke tom, many of its vocable phrases for reciting (including the initial and final syllables) begin with to or tō; these syllables would be interpreted on the drum with a toṃ stroke (underlined in the transliteration). Since Origin Verse 7 (Paragraph 6.7) is about the stroke naṃ, many of its vocable phrases for reciting (including the initial and final syllables) begin with na; these syllables would be interpreted on the drum with a naṃ stroke (underlined in the transliteration).

Return to text

34. As I have described elsewhere (Peiris 2022, 4–6) in terms of “drumming as surrogate speech,” a subset of these same musicians used these same techniques when performing a different type of piece (known as “tālama”) at a different Bera Pōya Hēvisi ritual.

Return to text

35. As Blum argues, “All humans theorize as we reflect on relationships we perceive or imagine in our various worlds and compare alternate courses of action, remembering or imagining their distinctive features and possible uses, and weighing possible reasons for unsatisfactory performances. We are theorizing when we analyze parts of a whole and reflect on their interrelations, when we recognize analogies or resemblances and ponder their implications, and when we evaluate new possibilities as ecological and social conditions change” (2023, 1).

Return to text

36. In these upat kavi, I have bolded the syllables belonging to the same rhyming class, to draw attention to the sonic patterning of assonance within the poetic meter. As detailed in endnote 33, I have underlined the vocables that would be interpreted on the drum using the seed syllable with the same (or similar) name.

Return to text

37. In the chronicle Mahavaṃsa, Maha Sammata is the primordial king of the universe.

Return to text

38. Varna in Sinhala usually refers to colors, but “timbres” makes sense to me in this context.

Return to text

39. Following the end of each line of bera pada, the rhythm/timbral pattern of the vocables is imitated on the drum.

Return to text

40. Double-headed cylindrical drum.

Return to text

41. Small quadruple-reed shawm.

Return to text

42. Larger shawm.

Return to text

43. Hour-glass shaped variable-tension drum.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Aidan Brych, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

4225