Translation of Martha Tupinambá de Ulhôa’s “Métrica derramada: Musical Prosody in Brazilian Popular Song”*

Chris Stover

KEYWORDS: microtiming, “métrica derramada,” prosody, expression, Elis Regina

ABSTRACT: Martha Ulhôa’s essay on musical prosody in Brazilian popular song develops the theoretical concept of métrica derramada, which I have translated as “fluid meter.” Drawing in part on the work of her musicological forebear Mário de Andrade (also represented in this special issue) and contemporary Luiz Tatit, Ulhôa considers how speech timing, vowel “tensity,” and other factors crucial to expressive speech influence sung musical melody, resulting in a musical structuring that is essentially malleable rather than produced by expressive stretchings of an underlying stable, isochronous grid. To illustrate, Ulhôa considers passages from a recording by the luminary Brazilian singer Elis Regina, suggesting how a number of musical parameters (not just timing) work together as an expressive whole, all animated in large part by the way the singer interprets the text.

PEER REVIEWER: Kjetil Klette Bøhler

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.15

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Translator’s introduction

[0.1] Brazilian musicologist Martha Tupinambá de Uhlôa has written extensively about nineteenth- and twentieth-century Brazilian music, spanning a range of styles and historical and theoretical topics. Ulhôa received her PhD in musicology from Cornell University in 1991 and taught at Universidad Federal Rio de Janeiro until her recent retirement. She remains active as a researcher and editor. Among many important theoretical contributions is this 1999 article on “métrica derramada,” which approaches the issue of musical microtiming from the perspective of the speech prosody of Brazilian Portuguese. Drawing in part on the work of her musicological forebear Mário de Andrade (also represented in this special issue) and contemporary Luiz Tatit, Ulhôa considers how speech timing, vowel “tensity,” and other factors crucial to expressive speech influence sung musical melody, resulting in a musical structuring that is essentially malleable rather than produced by expressive stretchings of an underlying stable, isochronous grid.

Métrica Derramada: Musical Prosody in Brazilian Popular Song

[1.1] One of the musical parameters most discussed by Mário de Andrade in Ensaio sobre a músical brasileira, and a key point that permeates his entire work, is the issue of rhythm. In Brazil, a musical performance is influenced primarily by one’s manner of accentuating words in speech, whose “prosodic values transfigure the melody” (Andrade 1972, 23). The resulting rhythm becomes so subtle that it is almost impossible to register it through traditional notation. Andrade observed this rich rhythmic imagination primarily in the examples he studied from northeastern Brazil.

[1.2] One of the basic principles of European rhythmic construction, which was in the process of being developed at the time of the discovery of Brazil, as Manuel Veiga would say, is the concept of meter (compasso), or the metric verticalization of musical structure.(1) Meter allows several voices to present a homogeneous (musical) discourse by providing an internal organization of pulsations into strong beats, propelling energy, and weak, inertial beats. In this case, the beginning of the measure is very important, as it presupposes a notion of linear time, of energy that progresses in an organized and predictable manner.

[1.3] When this accepted natural order is questioned and the musical phrase begins on a weak beat and continues onto the next strong beat, it is said that a “syncopation” has occurred. For there to be syncopation, the presence of metric structure is necessary, with the beats hierarchically arranged so that the configuration of metric strength can be challenged by the displacement of the strong beats.

[1.4] As Andrade says in the Ensaio: “Brazilian music has in syncopation a consistency but not an obligation” (Andrade 1972, 30). The academic concept of syncopation, that is, “sound articulated over a weak beat or weak part of a beat, prolonged over the strong beat or strong part of the next beat” (the definition given by Aurélio(2)) does not always correspond to what actually happens in performance situations.

[1.5] In Brazilian music, there is a conflict between temporal process in the traditional European rhythmic conception, which would seek the simultaneity of linear time, and Amerindian and African concepts of circular time. In the Amerindian case certainly, and possibly in the African case, Andrade supposes, rhythm derives directly from speech (30). This “oratory rhythm,” free from the notion of the predictable succession of measures, conflicts with traditional European rhythmic processes, which operate within a metric structure conceived as having an autonomous musical sense.

[1.6] The Brazilian musician makes this ambivalence “an element of musical expression” (32), and much of what is called syncopation in reality would not be syncopation in the traditional usage of the term, but rather “rhythms that accept the physiological determinations of arsis and thesis, but ignore (or purposefully infringe on) the false dynamic doctrine of [Western European] meter” (33–34). Song melodies would not be syncopated, the ambivalence emerging from their counterposition with the accompaniment, which would accentuate the beat. Instead, the melodic flow would be non-metrical, its accentuation driven by a “musical fantasy, pure virtuosity, or prosodic precision

[1.7] In this text I expand on some aspects raised by Andrade, putting up for discussion a hypothesis about musical prosody in Brazilian popular song, the concept of fluid meter [métrica derramada], which refers both to aspects of synchronization between singing and accompaniment and to issues of accentuation in the song.

[1.8] In popular song, melody and lyrics closely influence each other. There are elements in the lyrics, especially their narrative or lyrical quality, that suggest different types of melody, and there are particularities in the melody, especially its melodic contour and the types of intervals used that define the character of the song. A complete study of musical prosody—including intonation, accent, melody, rhythm, and specific interpretative practices—is beyond the limits of this article, which is limited to discussing melody, melody and spoken language, and the relationship between melody and accompaniment in Brazilian popular song.

Melody

[2.1] The melody of a popular song is generally composed of the repetition or grouping of short melodic motifs: melodic-rhythmic formulas that function as “blocks of meaning,” as Gino Stefani (1987) puts it, ready to be incorporated, repeated, combined, or associated in creating the song. In his study “Melody: a Popular Perspective,” Stefani describes a model of “typical melodies,” which emerges from what he calls “common melodic competence” (22), that is, people’s ability to recognize and evaluate the song.(3) First of all, popular melodies are “singable music,” and second, they emerge from an “oral matrix” connected to the singing voice and a primary sense of pleasure. In an obvious reference to Freudian psychoanalysis, Stefani considers the singing voice, especially when vocalizing, that is, singing vowels, as corresponding to “the principle of pleasure, just as the speaking voice corresponds to the principle of reality” (23). One hypothesis to be inferred from this assumption is that the sung melody can connote sensations that are difficult to express verbally, becoming a powerful vehicle for communicating deep, rooted, even hidden or unconscious feelings, in addition to moral values and worldviews.

[2.2] Melody, therefore, is the common thread that identifies a song or popular music. When a song has lyrics, we sometimes have to hum them to be able to describe or remember them. Song lyrics are made in order to be sung, acquiring meaning only when a voice transforms its verses into singing.

[2.3] Melody is generally associated with the human voice; we think of it in terms of the continuous sound of singing. Singing, in turn, uses verbal language, whose minimum components are vowels and consonants. A song made only with vowels intoned in a continuous melodic line produces a melody in its closest state to human expression.

[2.4] A quality of characteristically melodic phrases is their lyricism. Even an instrumental phrase can have a melodic quality when its musical notes flow in a sequence of scale degrees relatively close to each other so as not to break the melodic movement. A lyrical melody usually has an undulating melodic contour. Leaps between notes are used economically, for emphasis or expression.

[2.5] The continuity of this sound flow is transformed, driven, broken by another musical parameter, rhythm, which gives the melody vitality and character (Toch 1985). Rhythm is characterized by temporal discontinuities. In singing, it is the consonants that break the fluidity of melodic speech.

[2.6] Luiz Tatit, in his work on song, discusses in detail the role vowels and consonants play in the song. According to Tatit (1996), vowels are responsible for what he calls “passionate tensivity” [tensividade passional], produced both by the stabilization of the melodic curve and by the discursive intonation of speech.(4) In another process of tensividade, which he describes as “somatic” or “thematic,” consonants generate movements, outline rhythms, build characters, establish genres.

[2.7] In the Brazilian conception of song, the melody is the starting point for the composition, with the rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment acting as elements of melodic support. Harmony, in this conception, expands the expressive possibilities of melodic singing, with the accompanying instruments able to create other melodies in counterpoint to the main melody, responding to or opposing it. The emphasis on the melody is so striking that all the notes that compose it are essential to the song’s identity, including those that would be considered surface-level ornaments in the European classical-romantic music that has so influenced popular Brazilian music. What could be considered superfluous for melodic evaluation, such as notes that are foreign to the basic harmonic structure of the song (grupetos, mordants, appoggiaturas) have a functional importance in popular Brazilian song.

[2.8] This autonomy of melody appears very frequently in the romantic song tradition that I call modinha-type songs.(5) In the performance of modinhas, the vocal solo stands out in front of the arrangement, with the instrumental harmonic accompaniment laying out a known and predictable structure, a bed for the unveiling of lyrical and undulating melodies.

[2.9] However, with bossa nova, there was an aesthetic shift in the relationship between melody and harmony. Before the bossa nova “revolution,” harmony functioned mainly as support for a relatively autonomous melody.(6) The emergence of bossa nova, with its emphasis on a “parlando” style and colloquial singing, as well as its use of complex harmonic progressions, represented a break with the romantic style of the time, which had become cliché. Bossa nova favored a cool and more restrained diction, with artistic and literary intentions.

[2.10] The move in bossa nova melodies toward more restricted and narrow melodic range helped to strip away the melodramatic qualities of the samba canção of previous decades. In reality, the melodic contour of bossa nova is much closer to the roots of traditional samba with its emphasis on text and the rhythms and intonation of spoken language. Bossa nova’s attitude toward lyrics is, however, of a different nature, due to its intention of distancing itself from “necessity”, of adopting a “disinterested” stance, as Andrade would say. In fact, bossa nova fulfills in urban samba the modernist-nationalist ideal advocated by Andrade: that of making the “functional” “aesthetic.”(7)

Melody and Spoken Language

[3.1] To better understand how spoken language and musical language intertwine in popular Brazilian song, let us recall some aspects of Portuguese, especially as spoken in Brazil. Brazilian Portuguese, like many other languages, uses syllabic stress as a means of phonological identification. One of the main characteristics of its accentuation patterning is the presence of a large number of paroxytonic words. This gives the language, and consequently the metric/prosodic structuring of its musical paradigm, an anacrustic tendency or feel.

[3.2] In Western music, a phrase is said to be anacrustic when it begins before and ends after the first beat of the measure. For each anacrustic beginning we have an equivalent unstressed or “feminine” ending. Linguists call this anacrustic sensation “right-hand prominence,” in reference to the direction of accentuation in each phrase (Ester Scarpa, personal communication(8)).

[3.3] Brazilian prosody is syllabic, verses being specified by their number of syllables (from one to twelve, generally, counted up to the last accented syllable); each type of verse has a fixed number of syllables, limited by an obligatory final tonic accent. Although each word may have its stressed and unstressed syllables, it is the logic of the sentence that prevails. Depending on its location in a verse or phrase, an accented word or syllable may have its accent nullified, or the phrase may vary in terms of syllable limits, and its syllables may even be prosodic or metric, as in the word luar, which can be counted as a monosyllabic word, like “luar,” or two-syllable, like “lu-ar” (Carvalho 1990). The scansion, or separation and counting of syllables, will depend on the total number of syllables in the verse. Another very important aspect in terms of the structural organization of the sentence is that words with more important meaning are located towards the end of the sentence; as Câmara Júnior (1972, 222) comments, “the last member of an utterance has a greater information content.”

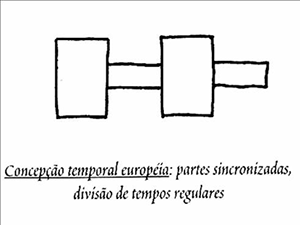

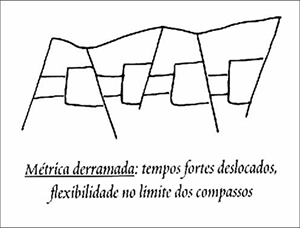

[3.4] In Portuguese versification, the verse is the metric measure, while the syllables, the minimal pulsations, are combined in varied rhythmic groupings. Comparing this metric organization of spoken language with Western and non-Western musical metric organization, we can say that the prosody of Portuguese verse is more like a sub-Saharan African metric notion (composed of periods or “time lines” without recurring accents) than a classical-romantic European metric notion (whose measures of determined limits follow one another regularly [see Example 3.1—translator’s note]). In the Portuguese metric conception, the size of the periods and the subdivisions of the syllables are variable, so that we have a “flexible” metric (see Example 3.2—translator’s note). There is also a tendency to place emphasis on the final part of an utterance, which is far from the Western understanding of time signature, whose beginnings are metrically prominent.

Example 3.1. European temporal conception: synchronized parts, regular divisions of time (click to enlarge) | Example 3.2. Métrica derramada: strong beats dislocated, flexible metric limits (click to enlarge) |

[3.5] It is interesting to note that, in certain European languages, such as English, accentuation patterns are isochronous; that is, the same amount of time takes place between one accented syllable and another (Cruttenden 1996, 24). Therefore, at least in the case of English, spoken language itself appears to be organized into regular “measures.” This characteristic appears in an especially striking way in rap (a word formed from the initials of rhythm and poetry) where a text is recited over a rhythmic basis. In the first raps used at funk dances in Brazil, English was imitated or overlaid with onomatopoeia (see Vianna 1988). Both in these “melôs” and in the case of rap in Portuguese, two prosodic issues appear. First is the use in Portuguese of a metric typical of English, that is, of regularly spaced thetic accents, which contributes to a sensation of regular measures. And second, there is the issue of successive ruptures typical of rap, produced by scratches, which makes music more of a “rhythmic partnership” than a complete interconnection between lyrics and melody (see Rose 1997, 207–8).

Métrica derramada

[4.1] A popular song is accompanied singing. The interference in the rhythm of the spoken word’s temporal organization does not pose any problem for monodic singing, but it becomes a complicating element for the performance of a song, precisely because it makes synchronization between the melody and the accompaniment difficult. Here we are faced with a problem of rhythmic incompatibility between the prosodic freedom of the song and the measured regularity of the accompaniment.

[4.2] One of the basic principles of European rhythmic conception is the notion of the measure [compasso], or the metric verticalization of musical structure (Copland 1974). The measure allows several voices to present a homogeneous speech by organizing the internal pulsations into strong beats that propel energy and weak, inertial beats. In this case, the beginning of the measure is very important, as it presupposes a notion of linear time, of energy that progresses in an organized and predictable manner.

[4.3] Another type of temporal organization that marked and greatly influenced the formation of popular Brazilian music was the conception of African rhythm-temporal organization, which is polyrhythmic. In this conception, there are independent but intertwined parts. Each part repeats a rhythmic “phrase,” incommensurable with one another, which make sense precisely due to their interweaving. Traditional samba itself, as we can see in the first recordings with this name, was formed by the repetition of small melodic-rhythmic patterns.

[4.4] What is quite prominent in sub-Saharan African music is the establishment of a temporal order based on the interaction of multiple parts that produce a polyrhythmic texture. The structure of its rhythmic organization is based on asymmetrical groupings of minimum time units or “fastest pulses,” as explained by Kwabena Nketia in The Music of Africa (1974). There is no vertical alignment at the beginning of the measure, as in European notions of meter [compasso].(9) As Simha Arom explains in his work on polyrhythm in Central Africa (1994), there is no regular pattern or intermediate level (such as measures and downbeats) between the pulse level and the musical period. This period, often formed by the addition of rhythmic patterns of varying size, can be externalized through claps that mark the dance steps or by a guide instrument that plays what is known as a time-line. The resulting sound mesh of an African percussion ensemble is quite complex from the point of view of interweaving and texture, although the individual rhythmic phrases of each part may be repeated groupings of quite simple motifs. The rhythmic-musical sense emerges in African music from the interweaving of parts, with musicians finding their way in not by counting beats, but by adjusting to other parts that are independent, and often in metric groupings different from their own.

[4.5] In popular Brazilian song, the notion of measure, as in the European temporal conception, is maintained, but this measure is made more flexible, both in its limits and in its internal structure, which is modified in terms of its hierarchy of pulsations. The focus of energy in these measures can be displaced or diluted. The most obvious example of this “overflow” [derramamento] is samba, where there is a binary measure, but with the accent transferred from the beginning of the measure to its second half.(10)

[4.6] It is significant that in one of the first musical manifestations to acquire “national status,” according to Andrade, an example of métrica derramada appears. It is a lundu by Cândido Inácio da Silva, “Lá no Largo da Sé Velha,” composed in the first half of the nineteenth century and discussed by Andrade in 1944. Beginning with a strophic text, a melody is created with “Brazilian accents,” identified by Andrade as “syncopated anticipation, passing from one measure to another, with cadential movements” (Andrade 1944, 27). The prosodic solution strikes a happy balance: when adding an undulating, quasi-operatic melody to a short, fast-paced text, it would not make sense to wait for the arrival of the downbeat of the next measure to place the syllable prominently. The text excerpt is: “cobra feroz que tudo ataca / té d’algibeira tira a pataca.”(11) The tonic accents are in “roz” for feroz, “ta” for ataca, “bei” for algibeira and “ta” for pataca. Only in “algibeira” do the metric accents of the melody and lyrics coincide. In other instances, Inácio da Silva “spills” [derrama] the meter to accept the rhythmic exigencies of Portuguese not only in terms of syllabic accentuation, but also in terms of “character.” The author could not have composed a modinha, which would accept melismas and elongations of the text, to talk about surucucus (venomous vipers) in an iron cage in Largo da Sé or, the subtext of the song, to suggest a certain ironic criticism when speaking the refrain of “speculation” and “progress of the nation.”(12)

[4.7] In Brazil, the songwriter’s technical-aesthetic mastery was gradually refined as melody and lyrics became free from the formulaic patterns borrowed from traditional strophic song or the operetta or opera aria. To experience this transformation, simply listen to the first recordings of Casa Edison, then the productions from the 1930s, and then the recordings of the bossa nova and MPB movements, to have an example of different moments in this process.(13)

[4.8] From the hard prosody of the first recordings, where, most of the time, singers like Cândido das Neves and Baiano(14) are heard trying to adapt new lyrics to existing melodic formulas, we move through a period of fluid and mischievous “spoken song” by songwriters like Noel Rosa(15) and other samba musicians, voiced by singers such as Aracy de Almeida, Carmen Miranda, Nelson Gonçalves, Linda Batista, and others, to arrive, mainly through João Gilberto’s masterful conduction, at a kind of “sung speech,” an essential rhetoric of Brazilian sensibility—the distillation of several trajectories marked by different worldviews and ways of being-in-the-world.

Métrica derramada and performance

[5.1] Métrica derramada appears frequently in the performance of popular Brazilian music, not only in songs such as samba, bossa nova, and so-called MPB, but also in essentially instrumental music. In instrumental choro, for example, there is a relative independence of parts, which intertwine without merging into a synchronized sound mass in terms of temporal division. In Brazilian song, a very striking example of métrica derramada is Elis Regina’s performance of Gilberto Gil’s “Amor até o fim,” where singing and accompaniment seem “detached” from each other, in a relaxed synchronization. As Andrade would say, the general feeling is not of syncopation, but almost of a temporal independence of voices.

Example 5.1. Opening phrase of “Amor até o fim.”

(click to enlarge)

[5.2] The song begins in a “musical” meter, that is, with a clear accentuation of the strong beat of the measure, even if subverting spoken Portuguese, as in the first phrase, where the word “amor” begins on a strong beat (á-mor), instead of use the usual oxytone accentuation (a-môr) (See Example 5.1).

[5.3] Part of this problem (some would call it a “prosody error”) is that both the solo singing and the accompaniment begin on the downbeat of the bar. This may even be the reason why so many popular Brazilian songs have an instrumental introduction: to give the singer the tonality of the song and allow them to start with an anacrusis. In the case of “Amor até o fim,” however, the prominence given to love, rather than an error, seems like a deliberate attempt to bring a certain freshness to a reference so worn and abused in popular song.

Example 5.2. Voice and drums in “Amor até o fim.”

(click to enlarge)

[5.4] About fifty seconds after the song begins, it seems that melody and accompaniment separate into an apparently quite “syncopated” relationship. Now it is the lyrics (“Pra crescer, pra crescer”) that command the performance, the accompaniment accentuating the melody. In Example 5.2, the bottom staff shows the drums in the final and most important ten seconds of the song, before the recap of previous material. It is significant that both the lyrics and the music, at the moment of major “discrepancy” between the sung melody and the accompaniment, articulate an anacrusis announcing the main point made by the lyrics (“a rosa do amor tem sempre que crescer / a rosa do amor não vai despetalar / Pra quem cuida bem da rosa / Pra quem sabe cultivar”(16)).

[5.5] J. A. Prögler (1995), when testing Charles Keil’s (1995) proposed concept of “participatory discrepancies,” documented how there are minute durations of time between the attacks of notes played by jazz bassists and drummers. These metric spaces are very difficult to illustrate with conventional Western notation. Ethnomusicologists have created signs to express these “early” or “late” attacks. There is a specific moment, however, in Elis Regina’s performance, together with César Camargo Mariano (piano), Luizão (bass) and Toninho (drums), of “Amor até o fim,” in which this space between solo and accompaniment can be clearly noted, because it lasts almost half a beat. Note as well how, in Example 5.2, when Elis sings “A rosa do amor” she maintains the accentuation pattern predominantly “to the right” of how it would take place in spoken language, if we consider the principle of forward displacement or métrica derramada, i.e., the dilution of the measure, for prominence is given to the second rather than the first half of the measure. Note that it is a prominent duration, and not a dynamic accentuation that achieves this, since, especially in Brazilian Portuguese, the accents of the words are quite attenuated by the “soft and sing-song” intonation of the pronunciation spoken in Brazil.

[5.6] The pitch B is also the highest point in frequency in the piece. The tensity, which Tatit would call passionate tenseness, is intensified by the “participatory discrepancy” between solo and accompaniment. The last B articulates a hemiola on the final syllable of “cres-cer” and “A ro-sa,” at first with simultaneous attacks and then almost like an echo of “rosa.” Finally, the drums play a fill, before gradually returning to the metrical regularity of the accompaniment.

[5.7] Another instance of the use of métrica derramada appears in several interpretations by Milton Nascimento. As described in Carvalho (1990), Nascimento expands or compresses the timing of the songs he sings, not to adjust the words to a longer or shorter melody, but to fulfill their expressive demands in terms of sound and meaning. In “Canção da América,” the words expand by leaps with or without portamento, melisma, tremolo, the most diverse appoggiaturas, mordents, and grupetos, highlighting the emotional content of the song: the heart cries for escape—the feeling trapped in the chest—and to reestablish the bonds of friendship you have to listen to your heart, no matter what happens. (Carvalho 1990, 325–30(17)).

[5.8] These rhetorical gestures, as well as the spaces between musicians’ attacks or note endings in a musical performance, contribute greatly to making people move their bodies in specific ways and to hearing the “grain” of the song. The friction, discrepancy, or imbalance between melody and accompaniment in the song has the effect of grabbing the listener’s attention, soliciting their participation in sharing a level of tension and intensified energy in the moment of the performance.

[5.9] Evidently, these indeterminacies should appear at significant moments, at the times and places in which the lyrics or emotional content of the song demands them. Some performances can sound very “distant” and cold if the performer homogenizes their meter, systematically positioning their attacks always in front of, above, or behind the pulse. By “spilling” [derramar] the structure of strong and weak beats through the bar and accepting the prosodic coherence or “magic of the word sung in the Brazilian way,” as Caetano Veloso says, we gain “fantasy,” vitality, and freshness.

[5.10] We must be aware, however, that this is a very broad principle. Musical phrases, even from the classical-romantic tradition, as well as in spoken prose, appear in different shapes, so it is not always mandatory that all the beginnings of the measure are prominent. There is a lot of room for flexibility and innovation when it comes to prosody, whether spoken or musical. Speech articulations can be constructed in different ways, not only through dynamic accent, but also with intonation or pauses. In spoken articulation, prosodic aspects other than volume (duration, pitch, and vocal quality being some of them) can contribute to giving certain syllables prominence (Cruttenden 1996). In measured tonal music, although dynamics play a central role, duration and frequency (both in pitch class and harmony) also contribute to musical accentuation.

[5.11] In music of the classical-romantic European tradition, the articulation of the phrase can be inferred from the written score, at least in its most obvious aspects, such as duration, metric placement, harmonic rhythm, cadences, melodic direction, and so on. However, much of the musical meaning only emerges during the moment of performance. In performance, and especially in the case of popular song, singers use their interpretative skills to articulate and highlight the emotional content of each song. The vocal style of many Brazilian performers—Linda Batista, Elis Regina, João Gilberto, and Milton Nascimento, to name just a few—is as important to the effectiveness of the song as the compositions themselves. First of all, the performer can play with the meter, using or avoiding the strong beats of the measures, or expanding or contracting their limits. Second, they can accentuate certain words by changing the duration of the note they want to emphasize, either in the value of the sustained note or through ornamentation. Finally, another interpretive move may be a change in frequency; higher notes have more tension and are more prominent than lower notes; leaps attract more attention than stepwise movement. Therefore, when considering the interpretative practice of song, we must keep in mind that musical prosody is not just a matter of strong or weak beats.

[5.12] In rhythmic terms, the conception of fluid meter has to do with notions of meter both African and Western. In metric music of the European tradition, all parts tend to synchronize precisely; time is counted in regular pulsations, generally contained within binary or ternary measures, whose limits are represented by barlines, with an accent at the beginning of each measure. In the African music that had an impact on industrialized Brazilian popular music, independent parts intertwine. The dynamically stronger beats do not have a divisive function, but occur more through the increase in volume that results when an instrument has a note from its own circular musical period coinciding with that of another instrument. In métrica derramada there is a displacement of the measure’s strong beat (like what occurs in samba), thus there is a flexibility in the measure’s limits (while the accompaniment generally maintains a certain regularity in terms of the size of each measure, the solo voice can expand it or compress it). And to reiterate this point in the words of Mário de Andrade, at the conclusion of his article on Cândido Inácio das Neves and the lundu (Andrade 1944): “It’s not white but it’s not black anymore. It’s national.”

Chris Stover

Queensland Conservatorium

Griffith University

S01 3.16, South Bank Campus

140 Grey St, South Brisbane QLD 4101

Australia

c.stover@griffith.edu.au

Works Cited

Arom, Simha. 1994. African Polyphony and Polyrhythm: Musical Structure and Methodology, trans. Martin Thom, Barbara Tuckett, and Raymond Boyd. Cambridge University Press.

Andrade, Mário de. 1944. “Candido Inácio da Silva e o Lundu.” Revista Brasileira de Música 10: 17–39.

—————. 1972. Ensaio sobre a música brasileira. Livraria Martins Editora.

Buarque de Hollanda Ferreira, Aurelio. [1986] 2004. Novo Dicionário Aurélio da língua portuguesa. Edição Positivo.

Câmara Júnior, Joaquim Mattoso. 1972. The Portuguese Language, transl. Anthony J. Naro. University of Chicago Press.

Carvalho, Amorim de. 1974. Tratado de versificação portuguesa. Edições 70.

Carvalho, Martha de Ulhôa. 1990. “Canção da América: Style and Emotion in Brazilian Popular Song.” Popular Music 9 (3): 321–49.

—————. 1991. “Música popular in Montes Claros, Minas Gerais, Brazil: A Study of Middle-Class Popular Music Aesthetics in the 1980s.” PhD diss., Cornell University.

Copland, Aaron. 1974. Como ouvir (e entender) música, transl. Luiz Paulo Horta. Ed. Artenova.

Cruttenden, Alan. 1996. Intonation (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics). Cambridge University Press.

Cunha, Celso and Cintra Lindley. 1984. Nova grammática do português contemporâneo. Edições João Sá da Costa.

Galter, Vidal. 2013. Dicionário de música: teoria musical, danças, festas, ritmos, definições e conceitos gerais, folclore e ilustrações. Edição Brasilia.

Keil, Charles. 1995. “The Theory of Participatory Discrepancies: A Progress Report.” Ethnomusicology 39 (1): 1–19.

Nketia, J. H. Kwabena. 1974. The Music of Africa. Norton.

Prögler, J. A. 1995. “Searching for Swing: Participatory Discrepancies in the Jazz Rhythm Section.” Ethnomusicology 39 (1): 21–54.

Rose, Tricia. 1997. “Um estilo que ninguém segura: política, estilo e acidade pós-industrial no hip-hop.” In Abalando os anos 90, ed. Michael Herschmann. Rocco, 190–212.

Stefani, Gino. 1987. “Melody: A Popular Perspective.” Popular Music 6 (1): 21–35.

Tatit, Luiz. 1996. O cancionista—composição do canções no Brasil. EDUSP.

Toch, Ernst. 1985. La melodía. Editorial Labor.

Vianna, Hermano. 1988. O mundo funk carioca. Jorge Zahar Editor.

Works Cited (added)

Works Cited (added)

Bailey, Todd M., Kim Plunkett, and Ester Scarpa. 1999. “A Cross-Linguistic Study in Learning Prosodic Rhythms: Rules, Constraints, and Similarity.” Language and Speech 42 (1): 1–38.

Campos, Augusto de. 1968. Balanço do bossa e outras bossas. Perspectiva.

Scarpa, Ester M. 1999. “Interfaces entre componentes e representação no aquisição da prosódia.” In Aquisição da linguagem: questões e análises, ed. R.R. Lamprecht. EDIPUCRS, 65–80.

Stover, Chris 2019. “Contextual Theory, or Theorizing Between the Discursive and Material.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 7 (2): 13–40.

Treece, David. 2013. Brazilian Jive: From Samba to Bossa to Rap. Reaktion Books.

Ulhôa, Martha Tupinambá de and Luiz Costa-Lima Neto. 2013. “Memory, History, and Cultural Encounters in the Atlantic: The Case of Lundu.” The World of Music 2 (2): 47–72.

Footnotes

* This article first appeared in Revista quadrimestral da Academia Brasileira de Música 2 (1999). It extends work on sung prosody in Brazilian popular song and its relation with the music’s underlying temporal framework, which the author, Martha Tupinambá de Ulhôa, began in her doctoral dissertation (Carvalho 1991). Beyond its main introduction of the concept of métrica derramada, which roughly translates as “malleable meter” but which is put to work in a way that is not quite captured by that English word, it also considers how multiple musical factors, not just timing, contribute to music’s temporal profile. Thanks to Martha Ulhôa and Kjetil Klette Bøhler for their comments on the first draft. All footnotes are the translator’s annotations.

Return to text

1. Manuel Veiga is an ethnomusicologist and pianist and emeritus professor at Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Return to text

2. This reference is to Aurélio Buarque de Hollanda Ferreira’s Novo Dicionário Aurélio da língua portuguesa (Positivo, [1986] 2004), 1850. This definition is repeated in Vidal Galter’s Dicionário de música: teoria musical, danças, festas, ritmos, definições e conceitos gerais, folclore e ilustrações (2013).

Return to text

3. Stefani’s notion of “common melodic competence” refers to culture-specific understandings of how melodies tend to go. Stefani frames popular music as “post-ethnic” in the sense that its cultural boundaries (and hence what kinds of melodic features scan to what kinds of perceptual competencies) cut across time and place more than so-called traditional musics. While Stefani’s language could be updated, the broader point is important.

Return to text

4. Tatit’s vast work on tensive grammar and “tensividade” is a highly original theory of the semiotics of sung text, which also deserves to be translated for Anglophone readership.

Return to text

5. Modinhas are sentimental nineteenth-century Brazilian songs, the lyrical aspects of which were influential on later developments in Brazilian popular song.

Return to text

6. On the idea of bossa nova as a revolution (which appears to be more of an Anglophone than Brazilian construct), see Treece (2013), 56–96.

Return to text

7. Bossa nova’s connection to high modernist aesthetics is explored in Campos (1968).

Return to text

8. Ester Scarpa is a Brazilian linguist who has worked extensively on speech prosody: see Scarpa 1999 and Bailey, Plunkett, and Scarpa 1999.

Return to text

9. See Stover (2019) for more on the multivalence of the word compasso in the discourse of Brazilian musicians.

Return to text

10. Ulhôa is referring here to the phenomenally and metrically strong surdo (bass drum) stroke that sounds on each beat 2 of a two-beat measure in samba. The implication is that the beat-1 metric accent (as a strictly orienting phenomenon) has ‘spilled’ over onto beat 2, which is felt by expert insiders as what holds the measure together.

Return to text

11. A contemporary (but historically informed) recording of this song by Cafuzos do Lundu can be heard at https://open.spotify.com/track/383FnFetVrbHIArWsTXMiS?si=df1682fe52df45e9. The passage (the song’s chorus) in question begins at :31.

Return to text

12. Largo da Sé was an important landmark in the center of São Paulo during this period. Inãcio da Silva’s lundu is an early example of how scathing political commentary has been woven into popular music in Brazil. Lundu is an important stylistic precursor to samba—see Ulhõa and Costa-Lima Neto (2013).

Return to text

13. Casa Edison was the first recording studio in Rio de Janeiro, in operation from 1900 to 1960. MPB refers to música popular brasileira, an umbrella term for a wide range of Brazilian artists, primarily from the 1960s to 1980s.

Return to text

14. Manuel Pedro dos Santos, a singer who recorded in the early Casa Edison days, most famous for his recording of Xisto Bahia’s lundu “Isto é bom.”

Return to text

15. Noel Rosa was an influential samba composer, known for his scathingly satirical political lyrics.

Return to text

16. The subject “a rosa do amor” does not translate very smoothly into English (“the rose of love”), but the lyrics read, roughly: “the rose of love must always grow / the rose of love will not lose its petals / for those who take good care of the rose / for those who know how to cultivate it.”

Return to text

17. See Carvalho (1990) for a detailed prosody analysis of Nascimento’s performance on this recording. (Carvalho and Ulhôa are the same author.) A recording can be heard at https://open.spotify.com/track/5iWwT43swbnBR7Cr0uTe0g?si=d8401d3c50034473. A typo in the original lists the wrong page range for this citation.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2024 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Amy King, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

3026