Who is Allowed to Be a Music Theorist? Sarah Mary Fitton and Conversations on Harmony (1855)*

Stephanie Venturino

KEYWORDS: Sarah Mary Fitton, women in music theory, history of music theory, pedagogy, augmented sixth chords, chromatic-scale harmonization

ABSTRACT: As a field, we must work to recognize and elevate music theorists traditionally excluded from our histories of music theory. In this article, I introduce and examine one such excluded figure, Sarah Mary Fitton (ca. 1792–1874). Fitton’s Conversations on Harmony (1855), a series of dialogues between the fictitious young Edward and his mother, was popular with students and amateur musicians in Great Britain and France during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Study of her work (Shteir 1996; Rainbow 2009; Maust 2022) has centered almost exclusively on its pedagogical merit and not its music-theoretical content. I take Fitton’s Conversations beyond its usual music-educational context: while affirming all of her work as music theory, I highlight Fitton’s distinctive approach to augmented sixth chords, which encompasses generation, resolution, enharmonic reinterpretation, modulation, and chromatic-scale harmonization. Her work represents an important contribution to our historical understanding of chromatic harmony.

I also consider several crucial questions about Fitton and her Conversations. How might Fitton’s gendered dialogue both reinforce and subvert contemporaneous stereotypes about gender and professionalism? Why has her pedagogically oriented Conversations been largely ignored by the field of music theory? Why do Fitton and other women—such as Anne Young (Raz 2018a, 2018b), Oliveria Prescott (Lumsden 2020, 2022), Nanine Chevé, Louisa Kirkman, Fannie Hughey, Clare Osborne Reed, and Amy Dommel-Diény—traditionally not count as music theorists? How can the study of these authors and those from other marginalized communities help us reframe our music-theoretical questions? How can such studies help us understand and reform our methods of discipline formation?

DOI: 10.30535/mto.30.4.4

Copyright © 2024 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[0.1] “Why are C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, called the Scale of C?” This is the first question that little Edward poses to his mother in Sarah Mary Fitton’s Conversations on Harmony (1855), a dialogic harmony manual written for young British students and amateur musicians.(1) Over the course of thirty-six dialogues or “conversations,” Edward and Mother progress from notes and scales to extended chords, enharmonic modulation, and florid melodic accompaniment in four parts. The book’s author makes her purpose clear: she aims to “explain the rules of Harmony, in so simple a manner, as to bring their practical application within the reach of young students, and, also, to increase the pleasure of mere lovers of music, by enabling them to understand, in some degree, the theory of ‘sweet sounds’” (Fitton 1855, v).

[0.2] Fitton’s “theory of ‘sweet sounds’” was a resounding success across Great Britain.(2) Contemporaneous reviews laud its “remarkable clearness” and “ingenious diagrams,” which represent “a method eminently successful in awakening the interest, fixing the attention, and lessening the difficulties of youthful learners” (Morning Post 1855; Daily News 1855; Sun 1856). “This present publication,” opens an anonymous review in The Sun, “evidently from the pen of a highly-gifted person, will be welcomed by all who desire to please the ear, and through the ear to afford delight to the mind” (1856). The reviews do not attempt to identify the manual’s “highly-gifted” author, whose name does not appear on the title page.(3) Instead, they highlight its dedicatee, Cipriani Potter, principal of the Royal Academy of Music.(4) His approval of Conversations on Harmony “may be taken as a guarantee of its excellence” and “sterling merit” (Morning Post 1855; Sun 1856).

[0.3] Motivated by the success of her English-language book, Fitton swiftly published a French version: Manuel pratique et élémentaire d’harmonie: à l’usage des pensionnats et des mères de famille (1857). The Manuel pratique is much more than a translation; it is a complete reworking for an audience of female boarding school students and mothers.(5) Attributed to the gender-neutral “S. M. Fitton,” the book bears a mark of approval from the Paris Conservatory and a dedication to Fromental Halévy, a respected composer and member of the Institut de France. Again, Fitton’s work met with success: according to the Revue et gazette musicale, the first edition nearly sold out within three months of publication.(6) Several reviews from the time confirm a positive reception. Adrien de La Fage (1857, 131) lauds Mr. [sic] Fitton’s clear presentation, thoughtful ordering of material, and particularly helpful coverage of the rule of the octave. Hector Berlioz extends even higher praise in a satirical review: he cautions that Mr. [sic] Fitton’s “perfectly written” manual will certainly corrupt “the musical morality of young people and the safety of their parents and friends,” inciting innocent female boarders “to compose sentimental romances, passionate airs, love scenes, even damnable and damned comic operas.” Be warned, remarks Berlioz—over a thousand copies of the textbook have already been sold (1857, 228).

[0.4] Despite her work’s international popularity, Sarah Mary Fitton has largely been forgotten. The Irish writer, also a co-author of the celebrated Conversations on Botany (1817), remains virtually unknown in scholarly circles.(7) The few existing studies on Fitton focus almost exclusively on her pedagogical contributions, emphasizing her clear instructional approach and effective use of dialogue form. Ann Shteir’s (1996) discussion of Conversations on Botany highlights Fitton’s pedagogical style and her male influences.(8) Shteir credits Fitton’s brother William, a gentleman scientist who regularly hosted scientific conversazioni at the family home, with facilitating her botanical literacy. By virtue of her male guidance, Fitton’s work is both “exemplary in substance” and “exemplary in method”: she “educates the mother by giving her content and teaches her so that she can teach her children” (Shteir 1996, 91). Likewise, Bernarr Rainbow (2009, 247) describes Conversations on Harmony as a “domestic primer,” “lesson-notes of a student teacher” “framed as to prompt the reader who wished to instruct a child to go about it methodically.”(9) As detailed in Rainbow’s account, Fitton’s music-theoretical training “depend[ed] upon her upbringing as the younger daughter of a village clergyman of good family who had been educated at Eton and Oxford”: her father, who made a “serious study of harmony as a youth,” taught his daughter “all she knew” (2009, 245–47).(10) Following Shteir and Rainbow, Paula Maust (2022) emphasizes Fitton’s role as an educator.(11) According to Maust, Fitton’s explanations of quadruple meter and parallel perfect intervals in Conversations on Harmony testify to her “effective pedagogical strategies and her skillful prose.” Maust does not discuss Fitton’s music-theoretical contributions.

[0.5] In this article, I move the discussion of Fitton and her Conversations on Harmony beyond its usual music-educational context. Fitton’s pedagogical acumen is certainly noteworthy, as Shteir, Rainbow, and Maust rightfully attest. But she is much more than an exemplary educator: her work as a music theorist should be recognized. This shift is long overdue. Why should other instructional dialogues—such as Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum (1725), Joseph Riepel’s Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst (1752–68), and Jérôme-Joseph de Momigny’s La seule vraie théorie de la musique (1821)—warrant critical study while Fitton’s Conversations on Harmony does not?(12)

[0.6] This article proceeds in three parts. First, I provide a brief introduction to Fitton’s background and her harmony manual, both of which are practically unknown within the music-theory community. Then, I examine Fitton’s distinctive approach to augmented sixth chords, which encompasses generation, resolution, enharmonic reinterpretation, modulation, and chromatic-scale harmonization. While affirming all sections of Fitton’s Conversations as music theory, I intentionally highlight her music-theoretical inventiveness: her work on augmented sixth chords represents an important contribution to our historical understanding of chromatic harmony.(13) Finally, I suggest several historiographical lessons that we can draw from Fitton and her Conversations on Harmony. Why does the work of Fitton and other marginalized figures typically not count as music theory?(14) What does her modern reception tell us about our field’s construction of historical narratives? What can her story reveal about the values that underwrite our methods of discipline formation?

1. Sarah Mary Fitton and Conversations on Harmony (1855)

[1.1] Almost nothing is known about Fitton’s early life or musical training. She was born in the early 1790s in Dublin, Ireland.(15) An entry on Fitton’s brother in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography suggests that the family relocated to England around 1809, spending several years in London and Northampton.(16) The specific details of Fitton’s time in England are unknown. Her dedication of Conversations on Harmony to Cipriani Potter suggests a possible affiliation with the Royal Academy of Music; however, to my knowledge, no records link Fitton to the Academy.(17) She may have studied music privately with an Academy professor, but this cannot be confirmed.

[1.2] At some point, Fitton moved to France.(18) While clearly devised as a fictional coming-of-age novel, Fitton’s How I Became a Governess (1861) could have been inspired by her own experiences working abroad: during the nineteenth century, many British women were employed as governesses in France, where they enjoyed cheaper living costs and generous wages.(19) By the 1860s, Christina de Bellaigue remarks, “the number of English teachers in Paris was so large that it was feared that many would not find work” (2007, 207). Several letters written by Elizabeth Barrett Browning confirm Fitton’s Paris residence; in a letter dated May 29–30, 1852, the poet notes that “Miss Fitton had lived in Paris above twenty years & knew everybody” (quoted in Lewis 2000, 484).(20) Fitton apparently called Paris home for the rest of her life: she died on March 30, 1874, at 15, rue de la Ville-l’Évêque.(21)

[1.3] Fitton had a successful career as a writer of educational texts and children’s books. Her best-known work is Conversations on Botany (1817), distributed in nine editions between 1817 and 1840. Fitton’s earlier Conversations shares several features with Conversations on Harmony: beyond their similar titles, both books were published anonymously, employ dialogic form, and feature Edward and Mother as main characters. However, while Conversations on Harmony addresses both children and amateurs, Conversations on Botany is written expressly for children. The botany manual is also much shorter, comprising eighteen conversations in comparison to the thirty-six included in Conversations on Harmony. Furthermore, Fitton’s discussion of botany is largely derivative, as she adapts William Withering’s version of the Linnaean biological taxonomy.(22) In contrast, Fitton does not reference any outside sources or systems in Conversations on Harmony.

[1.4] The success of Conversations on Botany reflects botany’s widespread popularity during the Victorian

[1.5] Fitton published several other works after Conversations on Botany. In The Four Seasons: A Short Account of the Structure of Plants (1865), she adapts lectures given at the Working Men’s Institute in Paris. Her short stories—often misattributed to a Mr. John Robertson—appear in Household Words, Charles Dickens’s weekly literary magazine.(26) Fitton penned several fiction books, including The Grateful Sparrow (1859), How I Became a Governess (1861), Dicky Birds (1862), and My Pretty Puss (1866). In addition to Conversations on Harmony (1855), she also published Little by Little: A Series of Graduated Lessons in the Art of Reading Music (1863). While Conversations on Harmony offers comprehensive music-theoretical training, Little by Little—written for “young mothers with the hope that they may find it useful in teaching their children”—centers on piano playing and conveying “some slight knowledge of the theory of ‘sweet sounds’” (Fitton 1863, i). This later music manual is not written in dialogue form. Beyond introducing many of the music-theoretical concepts from Conversations on Harmony, its ninety-one short lessons focus on piano-specific topics, notably fingerings and finger exercises.(27)

Example 1. Table of contents in Fitton (1855, ix–xii)

(click to enlarge)

[1.6] The 248-page Conversations on Harmony is Fitton’s most substantial music-theoretical work. Example 1 shows the table of contents, which I divide into three main sections: music fundamentals, the basics of common-practice harmony and voice-leading, and advanced topics. The first section (Conversations 1–10) introduces notes, rhythm and meter, clefs, scales, intervals, and triads. The second section (Conversations 11–23) focuses on voice-leading, figured bass realization, and cadences. The third section (Conversations 24–36) covers various advanced topics, including extended chords, altered chords, augmented sixth chords, modulation, the rule of the octave, and florid melodic accompaniment in four parts. Augmented sixth chords first surface in the twenty-fifth conversation, which centers on altered chords. Fitton returns to the topic in the thirty-first conversation, where she discusses enharmonic reinterpretation and modulation. Her chromatic-scale harmonizations—several of which involve augmented sixth chords—appear in the thirty-second conversation, which examines the rule of the octave and the accompaniment of diatonic and chromatic scales.

[1.7] While not explicitly modeled after Gradus ad Parnassum, Fitton’s dialogic construction recalls Fux’s approach, albeit with teacher and student replaced by mother and son.(28) The conversations between Edward and Mother mirror those between Josephus and Aloysius: Edward typically asks short questions that elicit lengthy technical answers from Mother. However, unlike Fux’s Josephus, Edward does not submit model compositions for the instructor’s review. Mother—concerned with theoretical knowledge, not compositional practice—eschews error detection, arguably the cornerstone of Aloysius’s pedagogical approach.(29)

[1.8] Beyond linking to Fuxian precedent, Fitton’s Conversations on Harmony reflects a wider vogue for the “conversations” genre in nineteenth-century Britain. As Rainbow (2009, 245) describes, this “new type of elementary treatise” was popularized through Jane Marcet’s Conversations on Chemistry (1805). Marcet subsequently wrote several other manuals in the format, including Conversations on Political Economy (1816), Conversations on Natural Philosophy (1819), Conversations on the Evidences of Christianity (1826), and Conversations on Vegetable Physiology (1829). The success of Marcet’s books “prompted other anonymous writers to adopt both her manner of exposition and, perhaps somewhat less candidly, her use of Conversations as a title” (Rainbow 2009, 245). In her preface to Conversations on Botany, Fitton acknowledges Marcet’s influence: “it may be due to the author of the admirable ‘Conversations on Chemistry,’ to state, that the title of the present volume was chosen, because it was the only one that seemed to be adapted to the nature of the subject, which had not been appropriated by previous writers” (1817, v). While Fitton borrows from a popular trope for Conversations on Harmony’s title, she does not borrow any of its content: as the next section of the article shows, Fitton’s music-theoretical ideas are very much her own.

2. Fitton’s Approach to Augmented Sixth Chords

[2.1] In this section, I provide a thorough overview of Fitton’s unique approach to augmented sixth chords and their uses. In brief, Fitton derives augmented sixth chords from ascending and descending alterations of diminished triads, fully diminished seventh chords, dominant seventh chords, and minor triads. She focuses on linear processes rather than traditional scale-degree mapping and functional assignments. For Fitton, augmented sixth chords also trigger modulation and participate in various chromatic-scale harmonizations. As I discuss briefly at the end of this section, Fitton’s ideas alternately align with and depart from those of her British contemporaries, most notably John Holden (1770), Anne Young (1803), William Crotch (1812), Louisa Kirkman (1845), and Alfred Day ([1845] 1855). To be clear, it is not known whether Fitton engaged with any outside sources while writing Conversations on Harmony; she only references Cipriani Potter, who evidently provided her with “valuable suggestions” (1855, iii). However, this broader contextualization with contemporaneous music theory is necessary: it positions Fitton as an important voice in the historical conversation on augmented sixth chords.

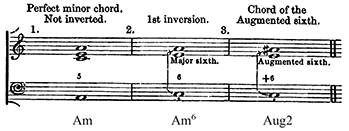

[2.2] Fitton offers three methods of augmented-sixth-chord generation, all linked to alteration. She does not invoke John Wall Callcott’s (1806) ethnic labels, which—as Daniel Harrison (1995, 182n29) remarks—did not become commonplace in British music-theoretical writing until the end of the nineteenth century.(30) Rather, she groups all three sonorities under the broad banner of “Chords of the Augmented Sixth” (Fitton 1855, 149).(31) To more closely reflect Fitton’s wide-ranging conception of augmented sixth chords, I abstain from using the traditional French, Italian, and German monikers: instead, I refer to these sonorities as Aug1, Aug2, and Aug3, respectively.

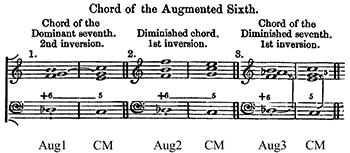

Example 2. (1.) An Aug1 chord derived from an altered second-inversion dominant seventh chord resolving to a root-position C major triad, (2.) an Aug2 chord derived from an altered first-inversion diminished triad resolving to a root-position C major triad, and (3.) an Aug3 chord derived from an altered first-inversion fully diminished seventh chord resolving to a root-position C major triad in Fitton (1855, 149)

(click to enlarge)

[2.3] Example 2 shows the first method. In the first progression, an Aug1 chord arises from a second-inversion dominant seventh chord with a lowered chordal fifth.(32) In the second progression, an Aug2 chord derives from a first-inversion diminished triad with a lowered chordal third. In the third progression, an Aug3 chord arises from a first-inversion fully diminished seventh chord with a lowered chordal third. Both Aug2 and Aug3 chords “have the leading tone for fundamental” (Fitton 1855, 149).(33) The D in each sonority is lowered to

[2.4] After introducing the first method of generation, Fitton turns to voice-leading guidelines. While she does not demonstrate how to resolve augmented sixth chords, she does use arrows to highlight the parallel perfect fifths in the third progression of Example 2. Mother quickly reassures Edward: “this fault is overlooked because the harsh effect of the two fifths is, a good deal, softened by the movement of three of the parts which, simultaneously, descend a half tone.” By contrast, a simultaneous descent by whole tone apparently would have made the effect of the parallel perfect fifths “much more disagreeable” (Fitton 1855, 191).

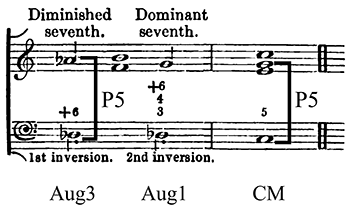

Example 3. An Aug3 chord transformed into an Aug1 chord to avoid parallel perfect fifths between the bass and alto voices (

(click to enlarge)

[2.5] As shown in Example 3, Fitton then provides a way to avoid this tricky situation entirely: a three-chord progression in which Aug3 transforms into Aug1, and Aug1 then resolves normatively to a root-position C major triad. This harmonic shift inserts a tritone between the two perfect fifths in the bass and alto voices, which are bracketed in the example. Surprisingly, Fitton does not suggest the conventional method for avoiding parallel perfect fifths; Mother never mentions to Edward that the Aug3 chord could resolve to a second-inversion triad or a cadential six-four.

Example 4. A dominant seventh chord enharmonically reinterpreted as an Aug3 chord in Fitton (1855, 189)

(click to enlarge)

[2.6] Example 4 illustrates Fitton’s second method of generation, which only involves the Aug3 chord. Mother explains that “when, in the chord of the dominant seventh, the seventh, only, is changed enharmonically, the chord is transformed into a chord of the augmented sixth” (Fitton 1855, 189). In Example 4, F4, the chordal seventh of the dominant seventh chord, is enharmonically reinterpreted as

Example 5. Derivation of the Aug3 chord in Example 4 from a first-inversion fully diminished seventh chord with a lowered chordal third in Fitton (1855, 189)

(click to enlarge)

[2.7] Example 5,(37) almost immediately following Example 4 in the harmony manual, illustrates Mother’s point. The first measure includes a root-position

Example 6. An Aug2 chord created by raising the fundamental of a first-inversion minor triad in Fitton (1855, 150)

(click to enlarge)

[2.8] Example 6 illustrates Fitton’s third method of generation, which focuses on the Aug2 chord.(38) She shows a root-position A minor triad in (1.) and a first-inversion A minor triad in (2.); in both measures, A4 is in the soprano voice. In (3.), the soprano voice rises to

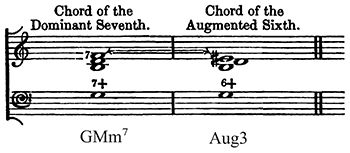

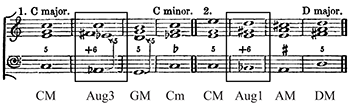

[2.9] Augmented sixth chords also play important roles in Fitton’s theory of modulation. Mother begins the discussion of modulation by telling Edward that “any transition from one scale into another scale is called Modulation” (Fitton 1855, 152). She presents three varieties: “Modulation into a Relative Scale,” “Modulation into a Distant Scale,” and “Half Modulation.”(39) When discussing the enharmonic reinterpretation in Example 4, Mother remarks that “this transformation of a chord of the dominant seventh into a chord of the augmented sixth, enables us to modulate into very distant scales” (Fitton 1855, 189). However, the augmented sixth chord does more than induce movement to distant scales; Mother notes that “we can use it [the augmented sixth chord] to modulate from one scale into all the others” (Fitton 1855, 190; italics added). Furthermore, any type of augmented sixth chord—if placed “immediately after a chord of the tonic”—initiates modulation (Fitton 1855, 190). This statement aligns with Mother’s earlier claim that “any chord of which the fundamental is either the dominant or the leading note of a scale, may be used in modulating” (Fitton 1855, 164).

Example 7. (1.) An Aug3 chord after a tonic chord initiates modulation from C major to C minor and (2.) an Aug1 chord after a tonic chord initiates modulation from C major to D major in Fitton (1855, 190)

(click to enlarge)

[2.10] Example 7 demonstrates the role of augmented sixth chords in modulation. The example shows the first two modulating progressions in a series of twelve; the following ten progressions illustrate the same modulatory process for the remaining diatonic and chromatic keys (Fitton 1855, 190–91).(40) The first progression (1.) shows modulation from C major to C minor. The initial root-position C major triad and subsequent Aug3 chord, boxed in the example, trigger this modulation. Fitton uses arrows to mark the parallel perfect fifths, which are acceptable here because the soprano, tenor, and bass voices descend by half step. The second progression (2.) modulates from C major to D major. The initial root-position C major triad and subsequent Aug1 chord, also boxed, initiate modulation. Not surprisingly, both augmented sixth chords resolve to root-position major triads a half step below.

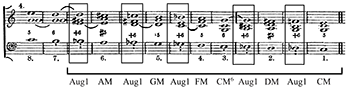

[2.11] Fitton’s coverage of augmented sixth chords extends beyond generation, resolution, and modulation: augmented sixth sonorities also feature in her inventive harmonizations of the chromatic scale. Mother explains that while the diatonic scale has a fixed rule, the chromatic scale does not, as “a chromatic scale is, in reality, a succession, by half tones, of every musical sound” (Fitton 1855, 196). Therefore, the harmonization represents “a succession of unfinished modulations” (Fitton 1855, 196). New diatonic collections, while constantly suggested by chromatic pitch classes, are always deferred. Precocious Edward notes that Mother’s exercises in chromatic-scale harmonization depart from musical practice, as “we seldom meet with an entire scale, completely accompanied, in music for the pianoforte” (Fitton 1855, 199). While acknowledging the artificiality of these studies, Edward recognizes their pedagogical merit. “The music I play will be much more interesting than it used to be,” he admits at the end of the thirty-second conversation, “now that I begin to see how each note helps to form a chord of some kind” (Fitton 1855, 199).

[2.12] Three of Fitton’s six chromatic-scale harmonizations feature augmented sixth chords.(41) Example 8 includes two augmented sixth chords, both boxed: an Aug3 chord resolves to a D major triad, and an Aug2 chord resolves to a C major triad. Per Fitton’s usual practice, both chords resolve downward by half step in the bass to a root-position major triad. The Aug3 chord derives from the preceding E fully diminished seventh chord; G4,

Example 8. Aug3 and Aug2 chords in a harmonization of a descending chromatic scale on C in Fitton (1855, 197); the numbers below the scale mark the diatonic scale members, and the number on the top left identifies the harmonization (third out of six) (click to enlarge) | Example 9. Alternating Aug1 chords and root-position major triads in a harmonization of a descending chromatic scale on C in Fitton (1855, 198); the numbers below the scale mark the diatonic scale members, and the number on the top left identifies the harmonization (fourth out of six) (click to enlarge) |

Example 10. Reverse small omnibus in a harmonization of an ascending chromatic scale on C in Fitton (1855, 197); the numbers below the scale mark the diatonic scale members, and the number on the top left identifies the harmonization (first out of six)

(click to enlarge)

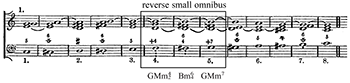

[2.13] Fitton also uses augmented sixth chords in various omnibus and passacaglia progressions. Example 10 shows her harmonization of an ascending chromatic scale on C. While not containing augmented sixth chords, this example sets up the forthcoming discussion of Example 11, where augmented sixth chords feature. The first and last five measures comprise an ascending chromatic sequence with applied chords. Boxed in the example, the middle three measures prolong a dominant seventh chord through what I call—adapting Paula Telesco’s (1998) term—a reverse small omnibus. A second-inversion B minor triad passes between third-inversion and root-position versions of a dominant seventh chord. B4 and D4 function as common tones throughout; the alto and bass voices form a voice exchange.

Example 11. Passacaglia progression and classic omnibus (prolonging C major) in a harmonization of a descending chromatic scale on G in Fitton (1855, 198); the numbers below the scale mark the diatonic scale members, and the number on the top left identifies the harmonization (sixth out of six)

(click to enlarge)

[2.14] Example 11, showing Fitton’s harmonization of a descending chromatic scale on G, extends her initial omnibus procedure via a classic omnibus progression. In the right-hand box, the progression (tonicizing C major) begins with a first-inversion dominant triad, not the conventional first-inversion dominant seventh chord: F5, the chordal seventh, enters with the second chord and continues for the rest of the progression. D5 and F5 hold throughout; the bass and soprano voices participate in a voice exchange. Fitton balances this classic omnibus with a chromatic harmonization of the passacaglia bassline, shown in the left-hand box.(43) The bassline continues chromatically beyond the dominant scale degree, denying the passacaglia progression’s typical harmonic goal: a root-position V(7) chord. Note that the initial tonicization of C major in mm. 3–4 foreshadows the extended tonicization of the same key via the classic omnibus progression in mm. 9–13.

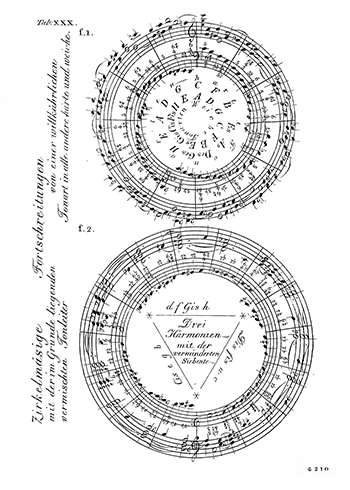

Example 12. Harmonization of the chromatic scale (Figure 2: “Drei Harmonien mit der verminderten Siebente”) in Vogler ([1776] 1778), table XXX

(click to enlarge)

Example 13. Harmonization of the chromatic scale in Vogler (1802), table XII; transcription from Wason (1985, 16)

(click to enlarge)

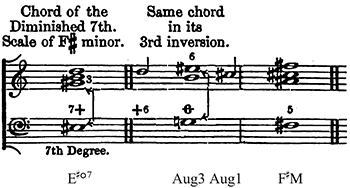

[2.15] Fitton’s approach to augmented sixth chords both aligns with and departs from ideas circulated in contemporaneous British music theory texts.(44) Notably, her coverage is much more comprehensive than that of most of her peers; beyond the typical topics of generation and resolution, she addresses enharmonic reinterpretation, modulation, and chromatic-scale harmonization.(45) To my knowledge, her chromatic-scale harmonizations find no precedent in British treatises from the time.(46) Her harmonizations vaguely recall those in Georg Joseph Vogler’s Gründe der Kuhrpfälzischen Tonschule in Beyspielen ([1776] 1778) and Handbuch zur Harmonielehre und für den Generalbass (1802), shown in Examples 12(47) and 13, respectively.(48) However, Fitton’s contributions stand apart. Departing from Vogler’s practice, her harmonizations do not represent modified extended omnibus progressions; furthermore, her fourth and fifth harmonizations include the Aug1 chord, which does not appear in Vogler’s harmonizations.(49)

[2.16] Fitton’s alteration-focused method of augmented sixth chord generation also intersects with work by compatriots Holden (1770), Young (1803), Crotch (1812), and Kirkman (1845), all of whom view augmented sixth chords as altered diatonic sonorities.(50) According to Holden, an augmented sixth chord arises when a diatonic chord is modified via “license” to include an “extreme interval”: “if the flat 6th be in the bass, and the

3. Concluding Thoughts and Questions

[3.1] Fitton offers much more than pedagogical clarity in Conversations on Harmony. She is doing music theory: her manual provides young students, amateur musicians, and their (presumably female) instructors with comprehensive training in music fundamentals, the basics of common-practice harmony and voice-leading, and advanced topics. While her approach to augmented sixth chords merits particular attention for its depth of coverage and originality, all of Fitton’s work reflects deep music-theoretical thought. Her contributions—along with those of other marginalized figures, female and otherwise—should be recognized, celebrated, and foregrounded within our decentered histories of music theory.

[3.2] In this section, I examine several crucial questions raised by Fitton’s work. First, how might Fitton’s choice of gender roles intersect with contemporaneous stereotypes about gender and professionalism? As Paula Gillett (2000, 3) describes, nineteenth-century British society was “sharply divided by gender.” In all areas of life, women “were subjected to the domination of the unfair sex”; “the law undoubtedly regarded almost every woman as under tutelage to some man, usually father or husband” (Perkin 1989, 1).(55) Women were considered physically, mentally, and emotionally fragile by nature: they “needed men to play the role of ‘sturdy tree’ to which their ‘vine’ could cling” (de Groot 2002, 99).(56) Put more bluntly, “women remained virtual chattels in the hands of their fathers, and later, their husbands” (Gay 1984, 174).

[3.3] As a result, many nineteenth-century British women—specifically middle- and upper-class white women—were restricted from the male-dominated public sphere and relegated to the home.(57) This widespread “cult of domesticity,” writes Deborah Gorham, “assigned to women both a separate sphere and a distinct set of roles” (1982, 4). Consider the so-called “Angel in the House”: this idealized woman was a meek, submissive, and comprehensively feminine figure wholly consumed with cultivating a domestic haven for her family.(58) While inhabited by women and children, this private sphere centered on men; it acted as “a place for renewal

[3.4] To be sure, the “Angel in the House” ideal did not apply to all nineteenth-century British women. “Women were seen as delicate and located within the home in the Victorian domestic ideology,” writes Radhika Mohanram, but “the reality was something different, given that vast numbers of women did not comply with the dominant ideology and worked outside their home for a living” (2007, 27; 32–33; italics original). Mohanram cites a 33-percent increase in British female domestic servants between 1851 and 1881, noting that “in short, millions of working-class women participated in heavy manual labor” (2007, 27). Nancy Reich comments that the “cult of domesticity” “caused considerable conflict for professional women musicians”: while recognizing their social deviance, they continued to work outside the home, as “earning money was a real necessity” (1993, 132).(59)

[3.5] These attitudes deeply influenced how white women of a certain class privilege engaged with music, both as amateurs and professionals. Women were certainly encouraged to play and teach music within their “allotted sphere” (Hyde 1998, 1); for instance, “a moderate level of skill at the piano was the core element in the ‘accomplishment’ curriculum of the well-bred girl, and an important prerequisite to success in the marriage market” (Gillett 2000, 4).(60) Ruth Solie points out that piano playing “had become thoroughly associated with young women by the middle of the nineteenth century; for better or worse, the piano-girl was ubiquitous” (2004, 89).(61) However, a well-to-do woman was discouraged from making music her profession.(62) As Matilda Pullan (1855, 81) proclaims in her Maternal Counsels to a Daughter: “Who would wish a wife or daughter, moving in private society, to have attained such excellence in music as involves a life’s devotion to it”?

[3.6] According to Gillett, the negative perception of female music professionals was largely driven by the widespread “belief that women [with music careers] compromised respectability by making themselves objects of the public—that is, of the male—gaze” (2000, 7). John Tosh (2005, 37) identifies a deeper issue, one tied to “the gender coding of the world of work.” While men readily accepted “the reality of women’s labor in the domestic setting as servants or home-workers,” they could not allow women to be paid workers outside of the home. Tosh explains that this refusal to admit women to the workplace did not stem from the fear that “there might be less work (or less well-paid work)” for men. Rather, these men feared that “their masculine identity as the working sex was at stake” (Tosh 2005, 37).

[3.7] In constructing her Conversations as a dialogue between mother and son, Fitton both reinforces and subverts these contemporaneous attitudes toward gender and professionalism. On the one hand, she portrays Mother as an “Angel in the House”: fulfilling her familial role, Mother, presumably an amateur musician, dutifully teaches her son the requisite music-theoretical concepts and analytical skills. This instruction takes place within the confines of the family home, Mother’s designated domain. On the other hand, Fitton characterizes Mother as a highly trained, intellectually gifted, and pedagogically savvy instructor. To recall Pullan (1855, 81), Mother exhibits “excellence in music”; she expertly explains a wide variety of music-theoretical topics without outside aids.

[3.8] Fitton’s mother/son casting also represents a striking departure from the student/teacher pairings in other nineteenth-century dialogic textbooks, where female teacher/male student duos rarely feature.(63) That Fitton includes Edward as a main character in her harmony manual is even more surprising given the subject at hand: at the time, music making and music teaching were viewed as highly effeminate endeavors, usually associated with women musicians.(64) In particular, “Victorian society rejected piano playing for the gentleman” (Burgan 1986, 60). Gillett notes that “piano-playing carried such strong feminine connotations that boys were often discouraged from studying the instrument” (2000, 5); as a result, piano instruction was generally “absent from male education” (Vorachek 2000, 26). This is certainly not the case for Edward, as both mother and son frequently reference the piano and piano playing.(65) “You must always play our examples on the pianoforte,” Mother advises, “that you may understand perfectly what we are about” (Fitton 1855, 21). Perhaps the study of music theory—a rational and seemingly scientific subject befitting the Victorian male mind—justifies the learning of a characteristically feminine instrument.

[3.9] Furthermore, how have Fitton’s gender and likely occupation as a governess affected her modern reception as a music theorist? Not surprisingly, misogynistic practices have played a role in Fitton’s omission from our histories of music theory. Her work, published anonymously and praised on the merits of its male endorsers, has never been recognized for its music-theoretical contributions. While perhaps not an unequivocal barrier in her own era, Fitton’s alleged position as a governess has likely not helped her modern reception. According to Bellaigue, governesses—especially those working during the first half of the nineteenth century—have historically been dismissed as “inexperienced and untrained amateurs,” a negative reputation that needs “substantial modification” (2007, 231).

[3.10] Unaided by her supposed occupation, Fitton’s work has been relegated to the educational arena, received as yet another unremarkable example of domestic pedagogical writing for young students, amateurs, and their instructors. Fitton has not benefitted from our field’s historically anti-pedagogical mindset, which deems music-educational works too elementary to merit serious study.(66) These pedagogical offerings may not meet contemporary demands for significance, originality, and rigor. They may not employ academic language. They may not propose new technologies or feature virtuosic analyses; instead, they may rehearse common tropes or highlight ostensibly uncomplicated repertoire. Our field’s degradation of music education has not been without consequence. We have shut out many music theorists and their ideas. Female music theorists, because of their frequent association with educational genres, have suffered particularly severe neglect from this bias against pedagogy. Fitton is just one of these victims: other pedagogically oriented writers—such Anne Young, Oliveria Prescott, Nanine Chevé, Louisa Kirkman, Fannie Hughey, Clare Osborne Reed, and Amy Dommel-Diény, to name just a few—have suffered similar fates.(67) The music theories of these women are not only “hidden,” to borrow Thomas Christensen’s ([2011] 2016, 69) description, but they themselves are invisible.(68)

[3.11] Thankfully, our notion of who counts in our histories of music theory has slowly begun to shift. Carmel Raz (2018a, 2018b) discusses Young, whose musical board games and 1803 treatise extend far beyond juvenile music pedagogy. Young’s theoretical approach, comments Raz, “neither entirely reflected the musical practice of the day, nor disclosed its own grounding in earlier traditions of speculative thought” (2018b). Despite her work’s originality, Young denies her own music-theoretical innovations, instead affording credit to two men: her brother Walter and the aforementioned theorist John Holden. The story of late nineteenth-century music theorist Oliveria Prescott, chronicled by Rachel Lumsden (2020, 2022), follows a similar path. Prescott’s discussions of fundamental and advanced topics reflect deep music-theoretical thought and strong engagement with the literature, particularly the writings of George Macfarren. Lumsden confesses her own bias against Prescott’s work, which she initially dismissed as “unscholarly,” “straightforward,” and “primarily pedagogical” (2020, [6.1]). “Sometimes music theory can be discovered in the most unexpected settings,” she concludes, “if we take the time to look—and if we dare to read with an open mind” ([6.2]).

[3.12] Lumsden is correct: we should engage all kinds of music theory with intellectual curiosity. Beyond broadening our music-historical and music-theoretical horizons, the study of music theorists such as Young, Prescott, and Fitton should also cause us to examine our own prejudices and historiographical habits. We must begin by admitting that our adherence to and glorification of music-historical and music-theoretical canons have deeply influenced the figures, musics, concepts, and technologies that we study.(69) We must also acknowledge our natural predilection for familiarity and convenience, our propensity to blindly protect the status quo. We return to the same composers and theorists; we recycle well-worn research questions. We continually grasp for neat, comprehensible, and untroubling historical narratives. These reductive, doxographical tendencies have severely limited our histories of theory: we assume that we have already answered all of the important music-historical and music-theoretical questions.(70) But what if this is not the case? What might happen if we entertained the idea—even provisionally—that there are historical figures we can learn from?

[3.13] This article has spotlighted Sarah Mary Fitton, a female music theorist who surely belongs within our decentered histories of music theory. However, Fitton is just one figure in a potentially wider, richer, and more complex music-historical narrative, one where women and members of other underrepresented communities not only count but are celebrated. While encouraging us to broaden our music-historical horizons, I also urge us to reflect on how we might initiate a historiographical transformation. How have we created and perpetuated disciplinary boundaries? How might these boundaries be re-negotiated? Can we weave together fresh perspectives, concepts, and contexts with our traditional narratives? Can we embrace a plurality of music-historical accounts, and in so doing open up a greater web of interpretation? Finally, how might these more diverse histories of music theory lead our discipline not only to deeper musical knowledge, but also to an increased sense of belonging, accessibility, and potential?

Stephanie Venturino

Yale School of Music

98 Wall Street

New Haven, CT 06511

stephanie.venturino@yale.edu

Works Cited

Aldwell, Edward, Carl Schachter, and Allen Cadwallader. 2019. Harmony and Voice Leading. 5th ed. Cengage.

Asioli, Bonifazio. 1819. L’allievo al clavicembalo. G. Ricordi.

Banister, Henry. 1891. George Alexander Macfarren: His Life, Works, and Influence. G. Bell & Sons.

[Beaufort, Harriet]. 1819. Dialogues on Botany, for the Use of Young Persons. R. Hunter.

Bellaigue, Christina de. 2007. Educating Women: Schooling and Identity in England and France, 1800–1867. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199289981.001.0001.

Benjamin, Thomas, Michael Horvit, and Robert Nelson. 2003. Techniques and Materials of Tonal Music: From the Common Practice Period to the Twentieth Century. 6th ed. Thomson-Wadsworth.

Bent, Ian. 2002. “Steps to Parnassus: Contrapuntal Theory in 1725; Precursors and Successors.” In The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, ed. Thomas Christensen, 554–602. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521623711.020.

Berlioz, Hector. 1857. Review of Manuel pratique et élémentaire d’harmonie à l’usage des pensionnats et des mères de famille, by S. M. Fitton. Revue et gazette musicale de Paris 24 (28): 228.

Biamonte, Nicole. 2008. “Augmented-Sixth Chords vs. Tritone Substitutes.” Music Theory Online 14 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.14.2.2.

Bradley, Deborah. 2017. “Decentering the European Music Canon.” In College Music Curricula for a New Century, ed. Robin D. Moore, 205–23. Oxford University Press.

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett. 1899. The Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Edited by Frederic Kenyon. Vol. 2. Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1093/oseo/instance.00121521.

Browning, Elizabeth Barrett, and Robert Browning. 1958. Letters of the Brownings to George Barrett. Edited by Paul Landis with Ronald E. Freeman. University of Illinois Press.

Burgan, Mary. 1986. “Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth-Century Fiction.” Victorian Studies 30 (1): 51–76.

Callcott, John Wall. 1806. A Musical Grammar, in Four Parts. B. Macmillan.

Chevé, Mr. and Mrs. Émile [Émile Chevé and Nanine Chevé]. 1856. Méthode élémentaire d’harmonie. Chez les auteurs.

Chevé, Mrs. Émile [Nanine Chevé]. 1844a. Méthode élémentaire de musique vocale. Chez l’auteur.

—————. 1844b. Nouvelle théorie des accords (servant de base à l’étude de l’harmonie). Durier-Marin.

Christensen, Thomas. [2011] 2016. “Fragile Texts, Hidden Theory.” In The Work of Music Theory: Selected Essays, 55–73. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315084879-3

Citron, Marcia. 1993. Gender and the Musical Canon. Cambridge University Press.

Clark, Suzannah. 2011. Analyzing Schubert. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511842764.

Clemmons, William. 2001. “Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum and the Traditions of Seventeenth-Century Contrapuntal Pedagogy.” PhD diss., The Graduate Center, CUNY.

Clendinning, Jane Piper, and Elizabeth West Marvin. 2021. The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis. 4th ed. W.W. Norton.

Cohen, Michèle. 2015. “The Pedagogy of Conversation in the Home: ‘Familiar Conversation’ as a Pedagogical Tool in Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century England.” Oxford Review of Education 41 (4): 447–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2015.1048114.

Crotch, William. 1812. Elements of Musical Composition. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown.

Daily News. 1855. Review of Conversations on Harmony, by the author of “Conversations on Botany,” October 20.

Damschroder, David. 2008. Thinking about Harmony: Historical Perspectives on Analysis. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511482069.

Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. 1987. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780–1850. University of Chicago Press.

Day, Alfred. [1845] 1855. Treatise on Harmony. 2nd ed. Edited, with appendix, by G. A. Macfarren. Harrison & Sons.

Dommel-Diény, Amy. 1953. L’harmonie vivante. Delachaux and Niestlé.

Dowd, Michelle M. 2018. “Navigating the Future of Early Modern Women’s Writing: Pedagogy, Feminism, and Literary Theory.” In Gendered Temporalities in the Early Modern World, ed. Merry Wiesner-Hanks, 261–82. Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048535262.012.

Edgeworth, Maria. 1795. Letters for Literary Ladies. J. Johnson.

Ehrlich, Cyril. 1985. The Music Profession in Britain Since the Eighteenth Century: A Social History. Oxford University Press.

Ellis, Mark. 2010. A Chord in Time: The Evolution of the Augmented Sixth from Monteverdi to Mahler. Ashgate. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315097787.

Fischer, David Hackett. 1970. Historians’ Fallacies. Harper and Row.

[Fitton, Elizabeth, and Sarah Mary Fitton]. 1817. Conversations on Botany. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

[Fitton, Sarah Mary]. 1855. Conversations on Harmony. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

—————. 1859. The Grateful Sparrow. Griffith and Farran.

—————. 1861. How I Became a Governess. Griffith and Farran.

—————. 1862. Dicky Birds. Griffith and Farran.

—————. 1863. Little by Little: A Series of Graduated Lessons in the Art of Reading Music. Hutchings and Cope.

—————. 1866. My Pretty Puss. Griffith and Farran.

[Fitton, Sarah Mary?]. 1857a. “Boulogne Wood.” Household Words, July 25.

—————. 1857b. “A Companionable Sparrow.” Household Words, August 8.

—————. 1858. “Mosses.” Household Words, December 11.

Fitton, S. M. 1857. Manuel pratique et élémentaire d’harmonie: à l’usage des pensionnats et des mères de famille. Brandus & Dufour.

—————. 1865. The Four Seasons: A Short Account of the Structure of Plants. Griffith and Farran.

Flannery, Mary C., and Carrie Griffin. 2024. “Introduction: Confronting Medieval and Early Modern Canons.” Textual Practice 38 (2): 201–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2024.2317002.

Fuller, Sophie. 2018. “Women Musicians and Professionalism in the Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth Centuries.” In The Music Profession in Britain, 1780–1920, ed. Rosemary Golding, 149–69. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315265001-9.

Fux, Johann Joseph. 1725. Gradus ad Parnassam. Van Ghelen.

Gauldin, Robert. 2004. Harmonic Practice in Tonal Music. 2nd ed. W.W. Norton.

Gay, Peter. 1984. Education of the Senses. Vol. 1. W.W. Norton.

Gillett, Paula. 2000. Musical Women in England, 1870–1914: “Encroaching on All Man’s Privileges.” St. Martin’s Press. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780312299347.

Girard, Aaron. 2007. “Music Theory in the American Academy.” PhD diss., Harvard University.

[Glover, Sarah]. 1834. German Canons or Singing Exercises and Psalm Tunes Expressed in the Sol-fa Notation of Music. Jarrold and Sons.

—————. 1835. Scheme for Rendering Psalmody Congregational: Comprising a Key to the Sol-fa Notation of Music, and Directions for Instructing a School. Jarrold and Sons.

Glover, Sarah. 1850. Manual, Containing a Development of the Tetrachordal System, Designed to Facilitate the Acquisition of Music, Be a Return to First Principles. Jarrold and Sons.

Goehr, Lydia. 2002. “In the Shadow of the Canon.” The Musical Quarterly 86 (2): 307–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdg012.

Golding, Rosemary. 2018. “Music Teaching in the Late-Nineteenth Century: A Professional Occupation?” In The Music Profession in Britain, 1780–1920, ed. Rosemary Golding, 128–48. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315265001-8.

Gorham, Deborah. 1982. The Victorian Girl and the Feminine Ideal. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203104095.

Grasso, Julianne, and Cory Arnold. 2022. “Music Theory YouTube.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Music Theory, ed. J. Daniel Jenkins. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197551554.013.32.

Grave, Floyd, and Margaret Grave. 1987. In Praise of Harmony: The Teachings of Abbé Georg Joseph Vogler. University of Nebraska Press.

de Groot, Joanna. 2002. “‘Sex’ and ‘Race’: The Construction of Language and Image in the Nineteenth Century.” In Sexuality and Subordination: Interdisciplinary Studies of Gender in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Susan Mendus and Jane Rendall, 89–128. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203402788-ch-3.

Gut, Serge. 1976. “Dominante—Tonika—Subdominante.” In Handwörterbuch der musikalischen Terminologie, ed. Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht, 1–15. Franz Steiner.

Hannaford, Marc E. 2021. “Fugitive Music Theory and George Russell’s Theory of Tonal Gravity.” Theory and Practice 46: 47–82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27251596.

Harrison, Daniel. 1995. “Supplement to the Theory of Augmented-Sixth Chords.” Music Theory Spectrum 17 (2): 170–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/745870.

Hexter, Jack H. 1961. Reappraisals in History: New Views on History and Society in Early Modern Europe. Northwestern University Press.

Hisama, Ellie. 2021. “Getting to Count.” Music Theory Spectrum 43 (2): 349–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtaa033.

Holden, John. 1770. An Essay Towards a Rational System of Music. Printed by Robert Urie for the Author.

Hughey, Fannie E. 1912. Color Music for Children. G. Schirmer.

Hume, David. [1779] 2007. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. Edited by Dorothy Coleman. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808449.

Hutchinson, Kyle. 2020a. “Chasing a Chimera: Challenging the Myths of Augmented-Sixth Chords.” Theory and Practice 45: 93–126. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27121054.

—————. 2020b. “From a Certain Point of View: Learning to Hear Consonance as Dissonance in Late Nineteenth-Century Tonality.” Theory and Practice 45: 127–62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27121055.

—————. 2022. “Chromatically Altered Diminished-Seventh Chords: Reframing Function through Dissonance Resolution in Late Nineteenth-Century Tonality.” Music Analysis 41 (1): 94–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/musa.12185.

Hyde, Derek. 1998. New-Found Voices: Women in Nineteenth-Century English Music. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429448416

Jacson, Maria. 1797. Botanical Dialogues Between Hortensia and Her Four Children. J. Johnson.

Jay, Elisabeth. 2016. British Writers and Paris: 1830–1875. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199655243.001.0001.

Jenkin, Henrietta. 1865. Once and Again. Bernhard Tauchnitz.

Joyce, Jeremiah. 1861. Scientific Dialogues. Longman.

Judd, Cristle Collins. 2000/01. “The Dialogue of Past and Present: Approaches to Historical Music Theory.” Intégral 14/15: 56–63.

Kennerley, David. 2018. “Professionalisation and the Female Musician in Early-Victorian Britain: The Campaign for Eliza Salmon.” In The Music Profession in Britain, 1780–1920, ed. Rosemary Golding, 53–71. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315265001-4.

Kim, Catrina. 2021. “Issues in Teaching Music Theory Ethically: Reframing University Directives of Antiracist and Decolonized Curricula.” Theory and Practice 46: 23–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27251595.

—————. 2023. “Orienting to Pedagogical Service.” Music Theory Spectrum 45 (1): 132–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtac019.

Kirkman, Mrs. Joseph [Louisa]. n.d. Improved Method for the Guitar. Printed by the author.

—————. 1845. A Practical Analysis of the Elementary Principles of Harmony. Cramer, Beale, and Co.

La Fage, Adrien de. 1857. Review of Manuel pratique et élémentaire d’harmonie à l’usage des pensionnats et des mères de famille, by S. M. Fitton. Revue et gazette musicale de Paris 24 (16): 130–32.

Laitz, Steven G., and Michael R. Callahan. 2023. The Complete Musician. 5th ed. Oxford University Press.

Lang, Robert. 2012. “Konversationen über Musik. Zur pädagogischen Qualität musiktheoretischer Lehrdialoge.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 9 (1): 101–12. https://doi.org/10.31751/677.

Leonard, Kendra Preston. 2022. “Reparations in Music Scholarship.” American Music 40 (4): 525–29. https://doi.org/10.5406/19452349.40.4.17.

Lester, Joel. 1982. Harmony in Tonal Music. 2 vols. Knopf.

Lett, Stephen. 2023. “Making a Home of the Society for Music Theory, Inc.” Music Theory Spectrum 45 (1): 109–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtac021.

Lewis, Scott, ed. 2000. “The Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Her Sister Arabella.” 2 vols. PhD diss., University College London.

Lumsden, Rachel. 2020. “Music Theory for the ‘Weaker Sex’: Oliveria Prescott’s Columns for The Girl’s Own Paper.” Music Theory Online 26 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.3.4.

—————. 2022. “Oliveria Prescott and the Musical Amateur.” In The Oxford Handbook of Public Music Theory, ed. J. Daniel Jenkins. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197551554.013.5.

Luong, Vivian, and Taylor Myers. 2021. “Reframing Musical Genius: Toward a Queer, Intersectional Approach.” Theory and Practice 46: 83–96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27251597.

Macfarren, George Alexander. 1883. “Cipriani Potter: His Life and Work.” Proceedings of the Musical Association 10: 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrma/10.1.41.

Madrid, Alejandro L. 2017. “Diversity, Tokenism, Non-Canonical Musics, and the Crisis of the Humanities in U.S. Academia.” Journal of Music History Pedagogy 7 (2): 124–29. https://www.ams-net.org/ojs/index.php/jmhp/article/view/238.

Malebranche, Nicolas. [1688] 1997. Dialogues on Metaphysics and on Religion. Cambridge University Press. Edited by Nicholas Jolley and David Scott. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139164092.

Manabe, Noriko. 2023. “How SMT Could Become More Welcoming.” Music Theory Spectrum 45 (1): 142–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtac023.

[Marcet, Jane]. 1805. Conversations on Chemistry. Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme.

—————. 1816. Conversations on Political Economy. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

—————. 1819. Conversations on Natural Philosophy. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

—————. 1826. Conversations on the Evidences of Christianity. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green.

—————. 1829. Conversations on Vegetable Physiology. 2 vols. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green.

[Marshall, Emily?]. 1844. Woman’s Worth, or Hints to Raise the Female Character. H. G. Clarke & Co.

Marx, Adolf Bernhard. 1837–47. Die Lehre von der musikalischen Komposition, praktisch-theoretisch. 4 vols. Breitkopf & Härtel.

—————. 1841. Die alte Musiklehre im Streit mit unserer Zeit. Breitkopf & Härtel.

—————. 1852. The School of Musical Composition, Practical and Theoretical. Vol. 1. Translated from the fourth edition of the original German by Augustus Wehrhan. Robert Cocks and Co.

—————. 1997. Musical Form in the Age of Beethoven: Selected Writings on Theory and Method. Edited and translated by Scott Burnham. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511582721.

Maust, Paula. 2022. “Teaching the ‘Theory of “Sweet Sounds:”’ Sarah Mary Fitton’s 1855 Conversations on Harmony as Public Music Theory.” History of Music Theory SMT Interest Group & AMS Study Group, December 15. https://historyofmusictheory.wordpress.com/2022/12/.

McCrindell, Rachel. 1840. The School Girl in France. R. B. Seeley and W. Burnside.

Mohanram, Radhika. 2007. Imperial White: Race, Diaspora, and the British Empire. University of Minnesota Press.

Momigny, Jérôme-Joseph de. 1821. La seule vraie théorie de la musique: ou Moyen le plus court pour devenir mélodiste, harmoniste, contrepointiste et compositeur. Au magasin de musique de l’auteur.

Morning Post. 1855. Review of Conversations on Harmony, by the author of “Conversations on Botany,” October 25.

National Probate Calendar for England and Wales (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858–1995. 1874. Probate record for Sarah Mary Fitton. Principal Probate Registry, London. June 2.

“Nouvelles.” 1857a. Revue et gazette musicale 24 (9): 70.

—————. 1857b. Revue et gazette musicale 24 (24): 197.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 1889. Edited by Leslie Stephen. Vol. XIX: Finch–Forman. Smith, Elder, & Co.

Palfy, Cora S., and Eric Gilson. 2018. “The Hidden Curriculum in the Music Theory Classroom.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 32: 79–110. https://digitalcollections.lipscomb.edu/jmtp/vol32/iss1/5.

Pall Mall Budget. 1874. “Births, Marriages, and Deaths.” April 10.

Patmore, Coventry. [1854–62] 1885. The Angel in the House. 6th ed. George Bell & Sons.

Perkin, Joan. 1989. Women and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century England. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203401958.

Perkins Gilman, Charlotte. 1891. “An Extinct Angel.” Kate Field’s Washington, September 23: 199–200.

Peter, Philip Henry. 1972. “The Life and Work of Cipriani Potter (1792–1871).” 2 vols. PhD diss., Northwestern University.

Posen, Thomas William. 2023. “Windows into Beethoven’s Lessons in Bonn: Kirnberger’s Die wahren Grundsätze zum Gebrauch der Harmonie (1773) and Vogler’s Gründe der Kuhrpfälzischen Tonschule in Beyspielen (1776/1778).” Music Theory Online 29 (4). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.29.4.5.

Prescott, Oliveria. 1888. “Beethoven’s Sonata in E Flat, Op. 7: Analysis of Its Design and Harmony.” The Girl’s Own Paper, Saturday, March 24: 408, 410–12.

—————. 1904. About Music, and What it is Made Of: A Book for Amateurs. Methuen & Co.

Pullan, Matilda. 1855. Maternal Counsels to a Daughter. Darton and Co.

Rainbow, Bernarr. 2009. Four Centuries of Music Teaching Manuals, 1518–1932. Boydell Press.

Randel, Don Michael. 1992. “The Canons in the Musicological Toolbox.” In Disciplining Music: Musicology and Its Canons, ed. Katherine Bergeron and Philip V. Bohlman, 10–22. University of Chicago Press.

Raz, Carmel. 2018a. “Anne Young’s Musical Games (1801): Music Theory, Gender, and Game Design.” SMT-V: Videocast Journal of the Society for Music Theory 4 (2). https://doi.org/10.30535/smtv.4.2.

—————. 2018b. “Anne Young’s Introduction to Music (1803): Pedagogical, Speculative, and Ludic Music Theory.” SMT-V: Videocast Journal of the Society for Music Theory 4 (3). https://doi.org/10.30535/smtv.4.3.

—————. 2018c. “An Eighteenth-Century Theory of Musical Cognition? John Holden’s Essay towards a Rational System of Music (1770).” Journal of Music Theory 62 (2): 205–48. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-7127670.

—————. 2022. “To ‘Fill Up, Completely, the Whole Capacity of the Mind’: Listening with Attention in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland.” Music Theory Spectrum 44 (1): 141–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtab012.

Reed, Clare Osborne. 1927. Constructive Harmony and Improvisation. Clayton F. Summy Co.

Registre des actes d’état civil (décès), 8e arrondissement. 1873–74. Entry for Sarah Mary Fitton. Act no. 461: 59. Archives de Paris, V4E 3398.

Reich, Nancy B. 1993. “Women as Musicians: A Question of Class.” In Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship, ed. Ruth A. Solie, 125–46. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520916500-008.

Riepel, Joseph. 1752–68. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst. 5 vols. J. J. Lotter.

Rohr, Deborah. 1999. “Women and the Music Profession in Victorian England: The Royal Society of Female Musicians, 1839–1866.” Journal of Musicological Research 18 (4): 307–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411899908574762.

Scott, Derek B. 2002. “Music and Social Class in Victorian London.” Urban History 29 (1): 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926802001062.

Shield, William. 1815. Rudiments of Thorough Bass. J. Robinson.

Shreffler, Anne C. 2011. “Musikalische Kanonisierung und Dekanonisierung im 20. Jahrhundert.” In Der Kanon der Musik: Theorie und Geschichte: Ein Handbuch, ed. Klaus Pietschmann and Melanie Wald-Fuhrmann, 1–18. Edition Text + Kritik.

Shteir, Ann B. 1996. Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora’s Daughters and Botany in England, 1760–1860. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Slater, Angela Elizabeth. 2021. “Invisible Canons: A Reflective Commentary on the Formation of My Personal Canon of Women Composers.” In The Routledge Handbook of Women’s Work in Music, ed. Rhiannon Mathias, 177–86. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429201080-18.

Smith, Charlotte. 1795. Rural Walks. T. Cadell, Jr., and W. Davies.

—————. 1796. Rambles Farther. T. Cadell, Jr., and W. Davies.

—————. 1804. Conversations Introducing Poetry Chiefly on the Subject of Natural History. Vol. 1. J. Johnson.

Snodgrass, Jennifer Sterling. 2020. Contemporary Musicianship. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

Solie, Ruth A. 2004. Music in Other Words: Victorian Conversations. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520238459.001.0001.

Sun. 1856. Review of Conversations on Harmony, by the author of “Conversations on Botany,” January 17.

Table alphabétique des successions et des absences. 1868–80. Entry for Sarah Marie Fitton. Ire partie, no. 52, entry 108: 98. Département de la Seine, Bureau des Successions. Archives de Paris, DQ8 1802.

Tables des décès, 8e arrondissement. 1873–82. Entry for Sarah Mary Fitton. 109. Archives de Paris, D1M9 812.

Telesco, Paula J. 1998. “Enharmonicism and the Omnibus Progression in Classical-Era Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 20 (2): 242–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/746049.

—————. 2002. “Forward-Looking Retrospection: Enharmonicism in the Classical Era.” The Journal of Musicology 19 (2): 332–73. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.2002.19.2.332.

Thackeray, Anne. 1863. The Story of Elizabeth. Bernhard Tauchnitz.

Tosh, John. 2005. Manliness and Masculinities in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Essays on Gender, Family, and Empire. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315838533.

Vágnerová, Lucie, and Andrés García Molina. 2018. “Academic Labor and Music Curricula.” Current Musicology 102: 93–113. https://doi.org/10.7916/cm.v0i102.5366.

VanHandel, Leigh. 2023. “Who Does the Society for Music Theory Gather?” Music Theory Spectrum 45 (1): 156–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtac028.

Vogler, Georg Joseph. [1776] 1778. Gründe der Kuhrpfälzischen Tonschule in Beyspielen. Mannheim.

—————. 1802. Handbuch zur Harmonielehre und für den Generalbass. Johann André.

Von Glahn, Denise. 2013. Music and the Skillful Listener: American Women Compose the Natural World. Indiana University Press.

Vorachek, Laura. 2000. “‘The Instrument of the Century’: The Piano as an Icon of Female Sexuality in the Nineteenth Century.” George Eliot—George Henry Lewes Studies 38/39 (September): 26–43.

Walker, Margaret E. 2020. “Towards a Decolonized Music History Curriculum.” Journal of Music History Pedagogy 10 (1): 1–19. https://www.ams-net.org/ojs/index.php/jmhp/article/view/310.

Wason, Robert. 1985. Viennese Harmonic Theory from Albrechtsberger to Schenker and Schoenberg. UMI Research Press.

Weber, Gottfried. 1817–21. Versuch einer geordneten Theorie der Tonsetzkunst. 3 vols. B. Schott.

—————. 1842. Theory of Musical Composition. Translated from the third German edition by James F. Warner. J. H. Wilkins and R. B. Carter.

Woolf, Virginia. 1942. “Professions for Women.” In The Death of the Moth and Other Essays, ed. Leonard Woolf, 235–42. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Wray, Ramona. 2016. “Editing the Feminist Agenda: The Power of the Textual Critic and Elizabeth Cary’s ‘The Tragedy of Mariam.’” In Editing Early Modern Women, ed. Sarah C. E. Ross and Paul Salzman, 60–76. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316424278.004.

Yellin, Victor. 1998. The Omnibus Idea. Harmonie Park Press.

Young, Anne. 1801. Instructions for Playing the Musical Games. C. Stewart.

—————. 1803. An Introduction to Music: In which the Elementary Parts of the Science, and the Principles of Thorough Bass and Modulation, as Illustrated in the Musical Games and Apparatus, are Fully and Familiarly Explained. C. Stewart.

Footnotes

* I am deeply grateful to Rachel Lumsden, Henry Klumpenhouwer, Kyle Hutchinson, Lynette Bowring, David Keep, Braden Maxwell, and an anonymous reader from MTO for their insightful feedback on drafts of this article. Earlier versions of this research were presented at the 2022 annual meetings of the South Central Society for Music Theory, the Music Theory Society of New York State, and the Society for Music Theory.

Return to text

1. Sophie Fuller (2018, 151) discusses notions of “amateur” and “professional” in nineteenth-century Great Britain: during the first half of the century, the professional musician was associated with “the lower social classes, often [stereotyped as] a European immigrant with a poor general education.” In contrast, the amateur musician “was regarded as widely cultured and firmly situated in the middle or upper classes of British society” (Fuller 2018, 151). Julianne Grasso and Cory Arnold (2022) highlight a twenty-first-century version of the “amateur”/“professional” binary: music theory YouTubers (“amateurs”) versus music theory academics (“professionals”). Grasso and Arnold conclude that an “overall freedom of knowledge-sharing distinguishes MTYT [Music Theory YouTube] from academic music theory,” and “this relative freedom

Return to text

2. The book’s publication coincided with the increasing professionalization of music in Britain. Rosemary Golding (2018, 129) identifies an important shift in the 1820s: while private music teaching remained popular (as detailed in Ehrlich 1985), teaching institutions—such as the Royal Academy of Music, founded in 1822—began to appear, creating “opportunities for formal teaching contracts and a steady income, together with an element of prestige for teaching as an aspect of a musical career.” However, as Golding notes, many women “were seeking to avoid exactly this [professional] identity, working part-time, avoiding professional ‘working’ status, and making money in a piecemeal way” (2018, 129).

Return to text

3. The title page identifies the author of Conversations on Harmony as the author of Conversations on Botany (1817). Fitton wrote two books on botany: Conversations on Botany (1817) and The Four Seasons: A Short Account of the Structure of Plants (1865). I discuss these books in more detail, as well as explain botany’s popularity during the Victorian age, in [1.3]–[1.5].

Return to text

4. Potter (1792–1871) was an important musical figure in nineteenth-century Great Britain. Born into a musical family, he studied with Thomas Attwood, William Crotch, and Joseph Wölfl, among others. He was the first piano teacher at the Royal Academy of Music, where he also held the title of principal from 1832 to 1859. In addition, Potter composed numerous instrumental works and served as a music editor. For more on his contributions and legacy, see Macfarren 1883 and Peter 1972.

Return to text

5. Fitton’s two harmony manuals differ in their organization, conversational modes, and music-theoretical content. The 248-page Conversations, discussed in more detail in [1.6] and [1.7], comprises thirty-six dialogues; the 164-page Manuel pratique includes twenty chapters. Fitton notes this size difference in her dedication to Fromental Halévy, remarking that—with his assistance—she has made the French manual as concise as possible. Out of twenty total chapters in the Manuel, twelve combine at least two English conversations; and the eleventh, twelfth, fifteenth, and sixteenth chapters each comprise three English conversations. Fitton also includes new material: an eleven-page summary (inserted after the fourteenth chapter) and a section on transposition with clefs (part of the eighteenth chapter). The latter addition aligns Fitton’s book with the pedagogical tradition of her new French audience. While both manuals are written in dialogue format, they feature different conversational modes: Edward plays a primary role in the English version; Mother is the main character in the French version. The books feature similar music-theoretical topics. However, in the French version, Fitton simplifies her discussions of augmented sixth chords and the rule of the octave, arguably her most novel material. I suggest that the changes from the English Conversations to the French Manuel reflect prevailing French attitudes regarding female education and gender ideals. Fitton’s revisions in the Manuel are neither minimal nor trivial: they represent a thorough and calculated reworking for a new French—and thoroughly female—audience. The French book does not present the science of harmony to a wide audience of children and amateurs. Rather, it offers practical skills for the supposedly delicate female mind.

Return to text

6. The Revue et gazette musicale provided extensive coverage of Fitton’s Manuel pratique. Two notices—circulated in March and June 1857, respectively—advertise the forthcoming French edition. The first notice (“Nouvelles” 1857a, 70) boldly claims that Fitton’s Conversations caused a sensation in Great Britain, where it quickly became the harmony manual of choice for all public and private schools. The second notice (“Nouvelles” 1857b, 197), appearing three months after the French book’s publication, announces that the manual has nearly sold out. Fitton’s Manuel also received two full-length reviews: one by Adrien de La Fage, published in April 1857, and one by Hector Berlioz, published in July of the same year. Both reviewers praise Mr. [sic] Fitton’s clear presentation of harmony.

Return to text

7. Elizabeth Fitton, Sarah Mary Fitton’s sister, is sometimes listed as a co-author of Conversations on Botany. Her exact contribution to the book is unknown. In 1865, botanist Eugène Coemans dubbed a type of Peruvian mosaic plant the “Fittonia” in honor of the sisters.

Return to text

8. Shteir (1996, 92) briefly mentions that Fitton wrote Conversations on Harmony but does not provide further detail.

Return to text

9. Rainbow (2009, 245) does not discuss Conversations on Botany in any detail: he merely mentions that “a clue to the true identity of the author of Conversations on Harmony appears on its title-page, where we are told that it was written ‘by the author of Conversations on Botany.’”

Return to text

10. Rainbow does not cite the source(s) of these biographical details, which he takes from Fitton’s How I Became a Governess (1861). This work is not autobiographical, as discussed in endnote 19.

Return to text

11. While providing a bibliographic entry for Fitton’s Conversations on Botany, Maust does not mention the book in the main text of her blog post.

Return to text

12. Fitton’s Conversations appears in Robert Lang’s (2012, 108) table of music-theoretical treatises written in dialogue form, but her work is left undiscussed.

Return to text

13. My approach is influenced by Michelle Dowd’s (2018) work on early women’s writing. Dowd highlights the “differential treatment” often given to these women: their writing is regularly divorced from broader literary tradition, “read instead in terms of what it can tell us about women’s historical circumstances, especially their resistance to gendered structures of power” (2018, 268–69). While this is an important critical lens, it can also have a “narrowing effect” (Wray 2016, 62). Fitton’s work—like the writing of these earlier women—deserves comprehensive coverage that considers both her historical circumstances and her music-theoretical ideas.

Return to text

14. Music theory has long excluded women, a practice recently documented by Ellie Hisama (2021).

Return to text

15. Fitton’s obituary in The Pall Mall Budget (April 10, 1874) notes that she was 78 years old at the time of her death. However, French records state that she was 82 years old; see the succession and absence table for the Département de la Seine (1868–80) and the civil status register for the eighth arrondissement (1873–74).

Return to text

16. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, the geologist William Henry Fitton moved to London in 1809, “where he continued to study medicine and chemistry” (1889, 85). He relocated to Northampton in 1812: his mother and three sisters (left unnamed) reportedly “kept house for him” until 1820.

Return to text

17. Per personal email correspondence (dated November 6, 2023) with Ilse Woloszko, library assistant at the Royal Academy of Music, Fitton does not appear in any Academy prospectuses, minute books, club magazines, or museum catalogs.

Return to text

18. Fitton presumably moved to France before 1841, as she does not appear on the United Kingdom census taken on June 6 of that year. Unfortunately, the 1841 census records for Ireland are incomplete: the majority were destroyed in a fire at the Irish Public Record Office on June 30, 1922.

Return to text

19. Rainbow (2009, 245) claims that Fitton’s How I Became a Governess (1861) “describes her early career.” This is speculation; Fitton does not characterize the book as autobiographical. Christina de Bellaigue (2007, 209) identifies How I Became a Governess as a “fictional account” aligned with contemporaneous English travel writing on France. Similarly, Elisabeth Jay (2016) connects Fitton’s book to popular coming-of-age stories from the time, including Rachel McCrindell’s The School Girl in France (1840), Anne Thackeray’s The Story of Elizabeth (1863), and Henrietta Jenkin’s Once and Again (1865). “All of these novels,” writes Jay, “depict a crisis in which, before the heroine can regain the healthy normality and respectable marriage promised on English shores, she, or a comparator female figure who exists merely to offer a timely warning, will have to endure a life-threatening illness brought on by the moral dangers to which France has exposed them” (2016, 280).

Return to text

20. For other letters that mention Fitton, see Browning 1899, Browning and Browning 1958, and Lewis 2000.

Return to text

21. This death date appears in several places, including a succession and absence table for the Dèpartement de la Seine (1868–80), a civil status register for the eighth arrondissement (1873–74), a notice in The Pall Mall Budget (April 10, 1874), and a record from the National Probate Calendar for England and Wales (June 2, 1874). The probate record notes that Fitton’s effects in England are under £20; two beneficiaries—Roger Trappes and Francis Roger Trappes, the executors of her will—are listed. Fitton’s connection to these beneficiaries is unknown. Another French table of deaths (1873–82) lists her date of death as March 21, 1874.

Return to text

22. Fitton (1817, iv) explains her alignment with Withering’s version of Linnaean classification: while Fitton dislikes the system, it is the only suitable method available in English.

Return to text

23. Several dialogic manuals cover botany. Representative examples include Maria Jacson’s Botanical Dialogues between Hortensia and Her Four Children (1797), Harriet Beaufort’s Dialogues on Botany, for the Use of Young Persons (1819), Jane Marcet’s Conversations on Vegetable Physiology (1829), and three selections by Charlotte Smith: Rural Walks (1795), Rambles Farther (1796), and Conversations Introducing Poetry Chiefly on the Subject of Natural History (1804).

Return to text

24. Fitton quotes from Maria Edgeworth’s Letters for Literary Ladies (1795, 66).

Return to text

25. Bellaigue (2007, 176) notes that women of the time were often charged with “safeguarding religion,” a responsibility that resonates with the “rhetoric of Protestant domesticity” that prevailed throughout the Victorian age.

Return to text

26. Fitton’s The Grateful Sparrow first appears as “A Companionable Sparrow” in Household Words (August 8, 1857), where it is attributed to John Robertson. “Mosses” (Household Words; December 11, 1858) is also attributed to Robertson. However, the text is lifted almost verbatim from Fitton’s Conversations on Botany and The Four Seasons. Fitton may have written “Boulogne Wood” (Household Words; July 25, 1857); the author is listed as “Robertson’s friend.”