Schoenberg at the Movies: Dodecaphony and Film

David P. Neumeyer

KEYWORDS: twelve-tone method, Opus 34, commutation test, Frankenstein, cinema

ABSTRACT: Composers used the twelve-tone method in film scores from the 1950’s and 60’s. This essay, however, focuses on a much earlier work: Schoenberg’s Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielszene, Op. 34 (1930), which was, however, commissioned for a cinema-music library, not a specific film. I apply simple commutation tests to gauge how Opus 34 might actually function as background music, and I assess the implications of questions that arise about musical culture and class differences.

Copyright © 1993 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[1] The play on words is tantalizing, but, alas, no evidence to date suggests that twelve-tone music was written for any of the serials so popular in American film theatres in the Thirties and Forties. Serial music, however, did eventually find its way into feature films of the psychological-drama, sci fi, and horror genres. The majority of film composers who used serial methods picked them up about the same time Stravinsky did, in the early to mid Fifties. Leonard Rosenmann, for example, claims to have written the first fully serial score for a full-length feature film in 1955, for The Cobweb,(1) though by that time Roman Vlad, Kenyon Hopkins, Elisabeth Lutyens,(2) Roberto Gerhard, and perhaps others, had already used serial methods to varying degrees in their own work for films produced in Britain and Hollywood. By 1962, one might have been excused for thinking that the gulf between concert and film composition, and between the movie theatre and television, had been fully and irrevocably bridged—with Jerry Goldsmith’s serial score for the film biography Freud and NBC television’s premiere of The Flood, which had been commissioned from Stravinsky.

[2] Any number of questions arise from the historical circumstances sketched above. Among those that interest me is the obvious “Does twelve-tone music work, by the professional and critical standards of film composition?” Since “twelve-tone” designates a technique, not a style, however, the question becomes more meaningful if we substitute for “serial music” the broader “atonal music”; that is, the style of Viennese Expressionism. Research to this question can be carried out to a surprising extent without scores, by close study of film prints. Obviously, however, traditional close analysis—such as row- counting, location and interpretation of subtle intertextual references (such as B-A-C-H motives) or of relationships between row choice, row “progression,” and film action—does require scores, which are not generally accessible.

[3] I will pass by the “does it work?” question here, remarking only that I think the answer (for the classical Hollywood repertoire at least) is “yes, it does”—the most compelling instances, by far, to my ear, being not in the serial scores mentioned above, but in Rosenmann’s music for East of Eden, which transplants the manner of Schoenberg’s Opus 16 to turn-of- the-century Monterey and the inner turmoil of the James Dean character. In what follows, I shall concern myself with the earliest of all twelve-tone film scores—Schoenberg’s Begleitungsmusik zu einer Lichtspielszene, Op. 34 (1930). In particular, I discuss application of some simple commutation tests to gauge how this composition might actually function as background music. In the conclusion, I touch on a broad question that aims directly at matters of music and musical culture, namely, “How does film composers’ early use of serial methods affect widely held notions of class differences in twentieth- century composition?”

Schoenberg’s Opus 34

[4] As Dika Newlin has it, Schoenberg’s Opus 34 “was not really for the movies, but only symbolically.”(3) The facts, however, do not quite support this ideologically convenient assessment. The composition was requested by Heinrichshofen’s Verlag, which at the time specialized in music for use in silent-film performances.(4) Walter Bailey discusses Schoenberg’s contacts during this period with the German society of film-music composers; these clearly suggest that he had practical, not “symbolical” motives in accepting Heinrichshofen’s commission.(5) Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that the publishers thought they might receive something more than a “prestige” item—in fact, a composition they could license for performance. If they were disappointed, it would have been by the music’s difficulty, rather than its style, but, indeed, “it’s hardly to be assumed that this piece was played in theaters in the early Thirties.”(6)

[5] Opus 34 is not a single-movement composition; it consists of three more-or-less independent cues given titles by Schoenberg himself: “Threatening Danger” [Drohende Gefahr] (=bars 1–43), “Fear” [Angst] (=bars 44–155), and “Catastrophe” [Katastrophe] (=bars 156–219). The first cue is divided into two main sections of similar duration (1:21, 1:10, respectively). The first of these begins slowly with sinister ponticello string tremolos and motivic fragments cast about between the woodwinds and brass. This builds to a fortissimo tutti by 0:38, at which point the tempo picks up a little. Till the beginning of the second section at 1:22, tutti with abrupt changes between dynamic extremes (especially sharp brass chords at 1:08) must be treated as stingers. The second subdivision of the first part (“Maessig”) is somewhat more consistent. At first it hints at a waltz, with a clear, continuous melody in doubled winds. A short sforzando brass chord at 1:41, however, begins a slow process of melodic/thematic development that coincides with increasing tension until the end (2:21 ff), which is another tutti, very heavy and slowing down greatly. The music goes out loudly with a strong cutoff.

[6] The second cue (“Angst”) has four main divisions, the first and last very fast, the second a stretto (increasingly fast), the third section slower. The tempi of the first and last sections are stable, those of the intermediate sections vary. Timings are: 1:05, 0:22, 1:40, and 0:17. The final cue (“Katastrophe”) has two main sections. The first begins “Presto” and gradually slows down over the course of 43 seconds. A triple-forte climax is reached after 9 seconds and a loud dynamic level persists till approximately 9–10 seconds before the beginning of the second section, which is a long spun-out adagio (2:31) with a clear melody, mostly consistent (and relatively light) texture and low dynamic level.

Commutation Tests for Film Music

[7] The descriptions given above concentrate on characteristics

that point to certain practical problems of film underscoring—

timings of cues and their subdivisions, dynamic range, tempi, and

unusually marked events. In this, they prepare for comments on my

informal experiments using Schoenberg’s Opus 34 as a cue for

scenes from several early films. This process amounts to a simple

commutation test,which, as Claudia Gorbman describes it, “focuses

attention on the existing music versus the music that might have

been [and so] brings out stylistic and cultural information that

goes unrecognized in the usual processes of film viewing.”(7)

Commutation assumes that cinema is a well-defined code including

several clearly recognizable, separable sub-codes (images,

dialogue, sound, music). The normal mode of cinema is to invite

the spectator/listener to coordinate those several elements

during each segment of the film. This constitutes cinema’s

cognitive baseline, so to speak, and thus “whatever music is

applied to a film segment will do something, will have an

effect

[8] Gorbman herself considers the effects of altering Georges Delerue’s music for a scene from Jules and Jim by changing the mode to minor, making the tempo faster, or altering orchestration or articulation. She also substitutes for the cue a diegetic song from later in the film, a piano boogie-woogie, or Beethoven’s Fifth. In every case, it’s not difficult to predict the effect created, but what may be surprising is the extent to which a viewer’s basic understanding of visual and narrative contexts may be influenced by the musical accompaniment.

[9] For my purposes, it was convenient to flip the terms of Gorbman’s test—I took the first cue from Schoenberg’s Opus 34 (“Drohende Gefahr”) and applied it to three scenes from Frankenstein (1931), as well as to scenes from several other films released in the period 1929–1932, including The Blue Angel (1930) and Public Enemy (1931).(9) It was perhaps a bit unfair to Schoenberg that these are all sound films, but they are closely contemporary to Opus 34 and very early in the history of sound cinema. Furthermore, it was easier to make comparisons with the familiar conventions of Hollywood sound-film scoring practice, many of which were established in the years immediately thereafter (roughly 1932–35). In the following paragraphs, I make some general comments about the tests and discuss certain details of the “Monster’s Birth” scene from Frankenstein.

[10] The “Monster’s Birth” lies at the end of a long (11 minute) scene in which preparations are made in the lab, unexpected visitors arrive, and the Monster is “born.” Next to the ending scenes (Maria’s father carrying her body through the town square, and the search for the Monster), this is the most famous sequence in the film. It contains opportunities for some fairly continuous writing, the biggest obstacle being an active (and complex) sound-effects track, with much storm noise, “sizzling” of electrical gadgets, and so on. The “Monster’s Birth” begins with a flash of lightning and quickly following thunderclap which spur Henry Frankenstein and his assistant Fritz into action, while their three guests sit and watch. (The guests are concerned friends of Henry: his former professor Dr. Waldman, his close friend Victor, and his fiancée Elizabeth.) There is no substantive dialogue until Henry’s increasingly hysterical response to the Monster’s first auto-movements at the end of the scene. The action consists of Henry and Fritz moving about the lab, first checking electrical equipment, then unrolling covers from the Monster, raising the carriage up to an opening in the ceiling, later lowering same, the movements of the Monster’s right arm, and Henry’s response.

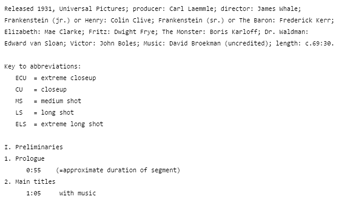

Figure 1. Segmentation (scene list) for Frankenstein

(click to enlarge)

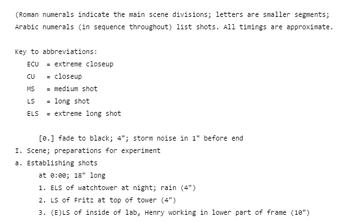

Figure 2. Shot list for Frankenstein, scene 8 (Watchtower)

(click to enlarge)

[11] Below is a detailed description and shot list for the “Monster’s Birth.” (For a segmentation of the entire file as well as a shot list for the scene which ends with the “Monstor’s Birth,” see Figure 1 and Figure 2)

- a. Flash of light at 8:39, then loud crash of thunder, at 8:39; 44" long then electronic sizzles as Fritz and Henry go to work. Very little dialogue through this

- 1. LS of lab from behind carriage (8")

- 2. carriage (3")

- 3. Visitors in their seats (2")

- 4. as in 2 (14")

- 5. Henry & Fritz at carriage (roll away blankets) (11")

- 6. as in 3 (Visitors sitting) (2")

- 7. as in 2, 4 (carriage) (4")

- b. Monster goes up in carriage; at 9:23; 70" long

- 8. LS from above; carriage goes up, camera following (22")

- 9. MS Henry (3")

- 10. CU Fritz (1")

- 11. LS lab, as at the end of shot 8 (3")

- 12. CU Victor & Elizabeth (2")

- 13. CU Dr. (2")

- 14. Carriage from a different angle (5")

- 15. as in 9 (MS Henry) (2")

- 16. as in 12 (CU Victor & Elizabeth) (2")

- 17. MS Henry (2")

- 18. carriage (as in 70) (2")

- 19. CU Fritz (2")

- 20.–21. Electrical equipment (3")

- 22. MS Henry (2")

- 23. Carriage followed down from ceiling (17")

- c. The Monster’s hand moves; Henry goes wild at 10:33; 30" long

- 24. CU Monster’s hand (3")

- 25. MS Henry, with hand in foreground (7")

- 26. as in 24 (3")

- 27. MS Henry at carriage, others enter shot (18")

- d. End of scene at c. 11:05

[12] Mapping any kind of music onto a sequence will cause problems because of the force of film-music conventions. I leave aside whether these conventions have arisen from natural (universal?) cognitive biases that would set up probabilities for most of us whenever we combine film and music, or whether they were something established in the silent and sound film cultures of the Hollywood production companies. The practical problems can be understood in terms of Gorbman’s seven “principles of composition, mixing, and editing,” her summary of the conventionalized solutions to practical problems of film-music composition.(10) Several do not apply to the matter at hand, but others—emotion, narrative and connotative cueing, formal and rhythmic continuity, and unity—flow directly out of the immediate task of spotting a film or film scene.

[13] I will start with the problem of the stinger, a sforzando chord or sharply marked short gesture which draws attention to something on the screen, a sudden turn of action or a shocked response—as it were, an accent in the imagetrack coordinated with an accent in the music. Stingers were used in silent-film accompaniment but came into their own with the recorded soundtrack and extensive employment by Max Steiner. (Later on, they were used most often in cartoons.) Any unusually marked music—but especially if marked by dynamics—must be regarded as a potential stinger. Opus 34 is full of them, especially the second section, but, in fact, since the stinger is meant to be an unusual event, the second section is actually easier to use as a cue. The first section has only a few potential stingers, and their use has to be planned fairly carefully so as not to seem silly (like the misplaced chords of a bad silent-film accompaniment). In one early application to the “Monster’s Birth” scene, I found that the lack of a stinger actually emphasized the failure of clear motivation for the exaggerated wincing of Victor and Elizabeth in shot 12 (lightning is seen and thunder heard throughout, but nothing unusually sharp either before or during the shot). The discrepancy was the more obvious because a stinger did coincide with the Doctor’s similar gesture in the following shot. In later moments, I caught myself asking why the Doctor was singled out in this way—and was even able to answer the question: the “scientific triumph” of Henry over the doubts (and even obstruction) of the establishment (the Doctor) is given physical interpretation by this sudden, involuntary (and undignified) gesture.

[14] From the above, two points arose which couldn’t be resolved with the means at hand—solutions would require rerecording using a mixer or a newly recorded performance. First, the volume levels of the music needed to be flattened—the range was too great to work well throughout the scene. Dialogue was sometimes lost under the music, the music sometimes inaudible under soundtrack noise. (In general, I actually found myself “disappointed” that the piece was less heavily scored and much less emotionally intense than I expected. On the other hand, the strong—and somewhat unexpected—build-up at the end of section one (bars 36 ff) matched very neatly Henry’s surprisingly intense (and overly dramatic) reaction to the Monster’s first movements.) Second, the tempi would need adjusting in several places in order to shift events such as stingers forward or back a few seconds. This “elasticity” has long been a requirement of film music and obviously arises from close temporal constraints unknown in concert music.(11)

[15] Another significant factor is that Frankenstein already has some music in the soundtrack: cues for the main and end titles, as well as source music for the dancing of Goldstadt citizens. We may safely ignore the music for the end title and cast list—even in the silent-film era, this was heavily conventionalized “framing” music whose source is the “up-and-out” closing progressions for opera and operetta overtures and scene or act conclusions. The dance music, likewise, is conventional, its melodies usually less clear than one might like, as the music competes with crowd noise. (Nor is any one tune linked closely enough with the citizens to become a naming theme.) More important, perhaps, is that it is very difficult to think of other places in the film where this music might appropriately be used. After this scene, the citizens are heavily involved in the film’s action, but the extended search for the monster and the burning of the windmill both call for “hurries,” a topos which can incorporate fleeting references to naming themes but is more likely to be thematically indifferent.

[16] The music for the main titles is another matter. David Broekman’s cue is rich in “exotic,” “grotesque,” and “sinister” affects , but it is poor in narrative referential functions (no suggestion of the general physical locale of the film nor even that of the opening scene; no suggestion of attributes of the main characters). Indeed, it relies in the earlier moments rather too heavily on a conflated exotic/oriental affect and so threatens to misplace the locale to (at least) the Caucasus rather than the mountains of middle Europe. As in the opera/operetta overture, the clearly presented theme would be expected to play a very important role in any underscoring for the film. Thus, the lack of any reference to this theme in the Schoenberg cue has to be taken as a disadvantage.

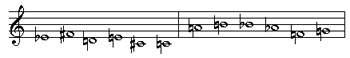

Example 1. Schoenberg, Opus 34, oboe melody, bars 9ff

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Schoenberg, Opus 34, series (P0 form)

(click to enlarge)

[17] A related problem is recurrent themes or motives within the cue itself. If a theme is established in relation to something—a character, place, situation, or even object—then recurrence of that theme will tend to recall or “name” that thing. (Indeed, the recurrence is necessary: the appearance of a melody sets up a referential possibility, but the recurrence confirms it as a narrative referential function.) The oboe theme at 0:38 (bar 9) is the first strongly melodic entity—extended melody rather than fragmentary motive—but it arrives just a bit too late: beginning at 0:26, the eleven seconds of shot 5 would have been perfect, as Henry & Fritz roll away blankets to give us our first full view of the Monster (see Example 1 and Example 2). The oboe theme, thus coordinated with a long shot, might have “named” the Monster (and, at another level, set up a conjunction of terms Monster/theme/(oboe)/Po.) At 0:38, we see the visitors sitting, not an occasion for a naming theme, even if the shot were longer than two seconds.

Conclusion

[18] As I suggested earlier, cognitive paths apparently make creating a film score no more difficult than playing a CD while the film is running; but commentary to the commutation tests should also have suggested that the interplay between cognitive biases and the traditions of film composition are such that standards of judgment are available—in short, that we can tell what a good film score is. I would further claim that the practical problems with the tests support an assertion that composing a good film score is not at all easy.

[19] The fact that film and “non-film” composers were experimenting with twelve-tone method at the same time also tends to undercut the assumption that popular culture lags behind the intellectually aristocratic “avantgarde,” a notion that goes back to the earliest days of the Romantic/modernist conjunction. One might also ask about implications of the fact that I found little use for the typical language or methods of musical analysis in my “mix-and-match” commutation tests. But then, I suppose it is no secret that our language or methods are not designed to facilitate judgments of value, but only to support them after they have been made. Perhaps the most far-reaching implication is that the link between the tools of technical musical criticism and the ideology of masterwork culture is not at all secure. If this suggests a crisis (I hope it does), possible solutions would seem to be: (1) entrenchment (a strategy of which music theorists were accused—with hilarious irony—by Joseph Kerman some years ago); (2) adoption of the socio/anthropo-logical stance (whose ideal—if not whose practice—emphasizes ideological detachment from the cultures being studied); or (3) serious modification of the dominant humanistic stance music theorists have shared with historical musicologists (in the direction of self-consciousness and inclusiveness). The first option doesn’t appeal to me; either of the others seems plausible.

[20] The class distinctions that have been supported by humanistic music scholarship can no longer be concealed. But, if so, where do we go from here? Where’s the real tinsel, anyway?

David P. Neumeyer

Indiana University

School of Music

Bloomington, IN 47405

neumeyer@ucs.indiana.edu

Footnotes

1. Roy Prendergast, A Neglected Art: A Critical Study of Music

in Films (New York: NYU Press, 1977), 119.

Return to text

2. According to an unpublished finder to film-music holdings in

the British Museum. I am grateful to Alfred W. Cochran for

sharing his copy.

Return to text

3. Dika Newlin, Schoenberg Remembered (New York: Pendragon,

1980), 206.

Return to text

4. Arnold Schoenberg, Saemtliche Werke, IV, vol. 14,1:

Orchesterwerke III, ed. Nikos Kokkinis and Jrgen Thym (Mainz:

Schott, 1988), B (Critical Report), xiii–xiv.

Return to text

5. Walter Bailey, Programmatic Elements in the Works of

Schoenberg (UMI Research Press, 1984), 21–22.

Return to text

6. Schoenberg, Werke, xiv.

Return to text

7. Claudia Gorbman, Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 18.

Return to text

8. Gorbman, 5. I am grateful to Stephen Simms for his recent

reminder that David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson use simple

commutation tests in their Film Art: An Introduction, third

ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 1990).

Return to text

9. Newlin (207fn) writes that Opus 34 was “used as background for

several films; I have seen only Jean-Marie Straub’s, in which a

narrative of anti-Jewish atrocities is imposed on it.” I haven’t

been able to verify her claim to date and would be very pleased

to hear from anyone who knows of films which use Schoenberg’s score.

Return to text

10. Gorbman, 73.

Return to text

11. Gorbman, 76.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1993 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Natalie Boisvert, Cynthia Gonzales, and Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistants

Number of visits:

6785