Grazyna Bacewicz’s Second Piano Sonata (1953): Octave Expansion and Sonata Form

Ann K. McNamee

KEYWORDS: linear analysis, 20th-century sonata forms, Polish folk music

ABSTRACT: If Grazyna Bacewicz’s music is so “conservative” and “neoclassical,” why is it so difficult to define the beginning and ending of the Development in one of her best-known works, the first movement of her Piano Sonata II? Thirty students and colleagues arrived at nearly thirty different answers to this question. I propose a linear analysis to best define the Development’ parameters, an analysis which reveals a large-scale octave descent in the bass register. This octave descent spans neither the major nor the minor scale, but instead prolongs a Polish folk mode known as the Podhalean mode.

Copyright © 1993 Society for Music Theory

INTRODUCTION

[1] Internationally acclaimed as both a concert violinist and a composer, Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–1969) holds a place in history as “the greatest woman composer of her time, and the most prolific female composer of all time.”(1) Her national and international awards for composition are numerous, reaching their peak during the 1950’s. In terms of Polish music history, Bacewicz succeeded Szymanowski in the leadership role in her country, before relinquishing that position to Lutoslawski and Penderecki. Her relative obscurity in the U.S. may be due to the conservative language of her music, reflecting her choice to conform to the political pressures of her times. Bacewicz’s music most often receives the adjectives “neoclassical,” “conservative,” and “influenced by Polish folk music.” Perhaps this apparent passivity was of less interest to Americans than the rebelliousness and modernism of Lutoslawski.

[2] Whatever the reasons for the previous lack of exposure, one now finds increasing interest in the U.S. in the music of this outstanding composer. New recordings, books, and articles appear with growng frequency.(2) However, very little has yet to appear in the way of detailed analysis. A piece which is perhaps the most readily available, beautiful, and representative of Bacewicz’s work is the Second Piano Sonata, composed in 1953. With the adjectives conservative and neoclassical in mind, one might expect that a formal analysis of the first movement of this piano sonata would be straightforward. After discussing the question of form with about 30 students and colleagues, I learned with each differing answer that the exact form causes great confusion. Not about whether or not the movement is in sonata form—that was agreed to by all. But confusion arose as to where the Development begins and ends. Perhaps Bacewicz’s music is more “neo” than “Classical,” perhaps more innovative than previously thought, while still conforming to the political demands of the day.

[3] The present article offers work in progress. Its focus is extremely narrow, that of finding the exact parameters of the Development section of the first movement of Bacewicz’s Second Piano Sonata. In order to define the form, I offer a combination of linear analysis and modal analysis, as well as a glimpse at Bacewicz’s sketch material. I propose that a large-scale prolongation of an octave defines the Development section, overshadowing thematic coincidences. Because the essay is online, I hope that this topic, which has already generated many differing responses, will continue to spark discussion in an electronic forum.

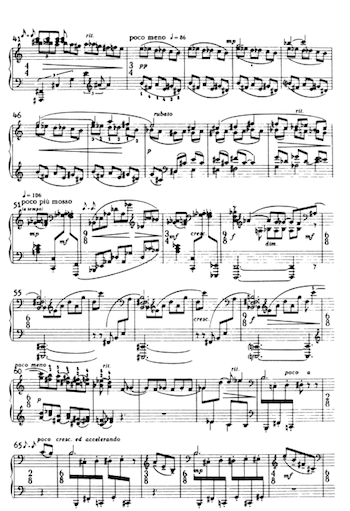

[4] The part of the score needed for this discussion can be found in Examples 1 and 2a–2d. For the entire score, see James Briscoe’s Historical Anthology of Music by Women, which contains all movements of the sonata.(3) The sonata has been recorded by the following four pianists: 1) Anna Briscoe, on the companion cassettes to the Historical Anthology of Music by Women, 2) Nancy Fierro, Avant AV 1012, 3) Krystian Zimerman, Muza SX 1510, and 4) Regina Smendzianka, Muza SXL 0977. Another alternative for hearing the piece is requesting that I send it to you electronically.(4)

[5] I will begin with a brief discussion of the opening phrases of the Exposition, then look for the start of the Development. After that formal point has been established, the start of the Recapitulation will be discussed. I will then consider the structure of the Development as a whole.

Exposition and the Beginning of the Development

Example 1

(click to enlarge)

Example 2

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 3

(click to enlarge)

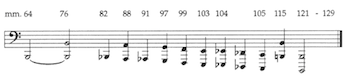

[6] As shown in Example 1, Bacewicz’s Second Piano Sonata opens with a two-measure Maestoso passage, followed by a change in tempo to Agitato. A critical feature of the link between these two musical statements is the bass motion, from the octave B in measures 1–2 to the octave E (the tonic). This simple, Classical gesture of a dominant to tonic motion also brings in the folk elements of the open octave pedal point and a melody which emphasizes perfect fourths. I view the first two measures as an anacrusis motive, a slow introduction to the first theme which begins in measure 3. The anacrusis motive becomes the central issue in deciding on the start of the Recapitulation. After the anacrusis motive, measures 3–10 contain the first theme, a full- bodied, 8-bar Agitato statement.

[7] Although a gap in the score occurs between Examples 1 and 2a (in order to keep the GIF files to a tolerable amount), the music shown in Example 2a introduces the second theme of the Exposition. I agree with Adrian Thomas that the second theme begins at the poco meno in measure 42. Thomas does not propose a starting measure for the Development, but instead characterizes Bacewicz as “a rhapsodist, constantly reshaping her materials through the developmental association of motivic ideas.”(5) This ambiguity of form is in keeping with Charles Rosen’s idea, that, after Brahms, sonatas often contain an indistinct link from the Exposition to the Development: “In general, it [sonata form] was considered a variant of ternary form, an ABA scheme in which the first A section does not really conclude, and the B section is characterized by fragmentation, thematic development, and a dramatic texture.”(6)

[8] Thomas and Rosen are perhaps supported by the varied, seemingly “random” answers I received for determining the start of the Development. Students and colleagues have selected almost every measure as a possible starting point between measures 65 and 91. I disagree with them all; I apparently alone hear the start of the Development at measure 64.(7) Somewhat of a cluster of responses seemed to favor measure 70 or 91 as the Development’s starting point. I believe that a detailed enough analysis of the form can yield a very convincing, quite innovative, structure. Examples 2a, 2b, 2c, and 2d contain the score for the entire Development section.

[9] Example 3 contains the sketch material for the disputed start

of the Development (reprinted by kind permission of the

University of Warsaw Library). Notice that the “poco a poco

cresc. ed accelerando,” which is buried a bit in the published

score (measures 64–66, Example 2a), is very prominently set off

in the sketch. This is fortuitous for me, because the start of

the “poco a poco cresc.” coincides exactly with what I call the

start of the Development. The sketch material raises several

questions, however. For example, in measure 64 of the published

score, a

[10] Of course, one should not read too much into the sketch

material in this instance. Other more compelling reasons support

the idea that the Development begins in measure 64. For example,

the measures preceding the Development, measures 55–59, contain

the anacrusis motive from measures 1 and 2, signaling an upcoming

important event. This sense of anticipation is extended in

measures 61–63 by a “trill,” F-

[11] All of these reasons lead to a clear decision that the

Development begins in measure 64: the anticipation of an

important formal event by both the anacrusis and trill motives,

the enharmonic

The Recapitulation

[12] While finding the start of the Development may be difficult for recent sonatas, finding the start of the Recapitulation for most sonatas, even non-tonal ones, should create less dispute. For this piece, however, student and colleagues’ responses clustered into three different places: measure 120, 129, or 130. (See Example 2d for the score.)

[13] One could argue that the music in measure 129 is so similar to the very first two measures of the piece that one must say the Recapitulation has already begun by this point. Alternatively, the choice of measure 120 as the start of the Recap presents a variant on this idea. The dramatic tempo shift in measure 120 after the long rests in measure 119, the similar melodic content of perfect fourths and minor sevenths, and the octave B in the bass all support this analysis. Proponents of this formal scheme say that the music of measures 1 and 2 has returned in measures 120–129, with an expansion and development. Charles Rosen mentions three examples of sonatas that contain slow introductions with reappearances at the same tempo later in the movement.(8)

[14] Both of these ideas (measure 120 or 129) for the start of the Recapitulation are flawed, and flawed for the same reason. Measures 1 and 2 do not present the first theme, but rather an introduction or anacrusis to the first theme, which does not begin until measure 3. Reasons for discounting the initial two measures as theme 1 are the brevity of melodic statement, the dramatic shift of tempo from slow to fast, and, most importantly, the bass note B which functions as a dominant, leading convincingly to E in measure 3. The theme in measure 3 has all of the characteristics of a sonata-allegro first theme, the allegro quality, a convincingly meaty melodic statement, and the tonic E as its bass. The melodic gestures in the first two measures, rising perfect fourths and minor sevenths, recur as upbeats at other points in the movement, at a faster tempo.

[15] While I am convinced that the Recapitulation cannot begin earlier than measure 130, I heartily agree with the idea that the first two measures of the piece are expanded in measures 120–29. But that supports the idea of Development or Retransition all the more, rather than Recapitulation. Of all the responses to my question of form, my most memorable was, “The Development ends in measure 119, and the Recapitulation begins in measure 130,” cleverly willing away the sticky issue of the Andante section.

Linear Analysis and Octave Expansion

[16] Something equally, if not more, important than all of the above reasons determines the form of this piece. Beneath the surface of the piece—the themes and the foreground progressions—the linear development and octave expansion at the middleground level best support the analysis of measures 64–129 as the Development. “Linear development” and “middleground” immediately conjure up the Schenkerian model, with its large-scale step-wise descents usually in the highest structural voice. Extending linear analysis to include twentieth-century music, several theorists have proposed more inclusive ideas of prolongation. Most prominent among them, Allen Forte proposes non-tonal prolongations in his many articles on linear analysis.(9) Other theorists, notably Paul Wilson, Joseph Straus, and Pieter van den Toorn, discuss linear motion over long spans of music in the works of Slavic composers.(10) These prolongations illuminate the structures of advanced tonal language and of nontonal music, and allow for prolongations of musical statements other than tonal ones. Registers other than the highest register may carry equal weight.

[17] Recognizing the inherent dangers of embarking on this slippery slope, I would like to continue down their path and introduce a modal prolongation of an octave, in the bass register. This octave expansion not only spans all of the Development section; it defines the Development section.

[18] Example 4a presents a preliminary version of a linear

analysis of the structure of the entire Development. During the

Development an octave is composed out in the bass, from the B in

measures 64–78 to the B in measures 121–29. One can easily find

comparable examples in the tonal literature for a Development

section being defined by a middleground prolongation of an

interval.(11) If one searches for a descending B Major or b minor

scale in the Bacewicz sonata, however, none would surface. A

particularly crucial part of a standard tonal investigation would

be the search for scale-degree 5,

The Podhalean Mode

[19] I propose a more logical choice for a scale, a Polish folk mode called the Podhalean mode, which infuses much of Bacewicz’s and Szymanowski’s music. Example 4b shows the pitches of a descending Podhalean scale on B. As in much of Slavic and Eastern European folk music, characteristic features of this mode are the raised fourth degree and the lowered seventh degree. Great importance is placed on the raised scale-degree 4, a tritone away from the tonic. Example 4c shows the same Podhalean scale on B, but written with enharmonic equivalents.

[20] This enharmonic form of the Podhalean mode appears very

prominently in the Development. As shown in Example 4d, a

middleground octave descent in the bass line spans the entire

Development section. I believe that this middleground descent is

compelling enough to be the main determining factor of form. The

start of the Development, in measure 64, presents a B in the

bass. A chromatic passing tone,

[21] Scale-degree 5 appears nowhere prominently. Instead, great emphasis is placed on the raised-fourth degree,

[22] If at this point in the Development one searches for scale-

degrees 3 and 2, one is tempted to assign great importance to the

descending

[23] Great anticipation of the Recapitulation begins in measure 105. The two-note motive develops both the trill idea and part of the theme from measure 29 (previously developed in measures 91ff.). A chromatic rising motion in the upper voice in measures 115–118 has appeared many times before. This chromatic figure first appears in the middle voice in measures 2–7 (especially in measure 6), as an accompaniment to the first theme. It is inverted in measures 41–47, as an accompaniment to the second theme. This chromatic figure begins the Development, in measures 64, 66, and 68, as part of a call-and-response juxtaposition with the trill figure in measure 65 and the fourths and sevenths figure in measures 67 and 69! The chromatic motive convincingly accompanies the arrival of B in the bass, which occurs in measures 115–119, but in the wrong, higher, octave. Or is it wrong? Perhaps the higher octave B in the bass during these measures, moving to the lower octave B at the Andante in measure 121, emphasizes linearly the vertical B octave itself. Put another way, the B-B motion summarizes the entire Development, and its linear expansion of that octave.

[24] The Development is not complete, therefore, without the arrival of the lowest B octave. After its arrival in measure 120, B structures the harmony over the next nine measures, creating an enormous development of the opening two measures of the piece. This long B is finally resolved to an E in measure 130. The Development is complete, the linear descent of an octave accomplished, and the Recapitulation perfectly prepared!(13)

Conclusion

[25] During the height of creative repression in Poland after the

War, Bacewicz chose to comply with Soviet directives and to use

traditional forms and Polish idioms for her compositions. The

neoclassicism in her music is obvious; no one hears this first

movement as anything other than sonata-allegro form. Yet, when

pressed for specifics, the “Classicism” has more depth than at

first glance; the exact form is not self-evident. Using my

analysis, we find an extraordinarily balanced movement, with

about two minutes of music each for the Exposition, Development,

and the Recapitulation. Halfway through the Development, the

second theme appears in the bass. The prolonged bass pitch for

the second theme is

[26] Many examples of folk influence occur in this piece. In measures 1–2, the slow introduction, great melodic emphasis is placed on the perfect fourth. This rising fourth generates the second theme of the Exposition by being filled in. Also, as shown literally in measures 1–2, two perfect fourths in succession create a rising minor seventh. This minor seventh echoes the lowered seventh scale degree of the Podhalean mode. The seventh also serves to intertwine the older folk idiom with the modern dissonance of exposed sevenths. As Adrian Thomas states so well, Bacewicz’s music is not formulaic.(14) Enter the term “rhapsodist,” a term which begs for clarification.

[27] Quite hidden to both characterizations of “rhapsodist” and “folk-influenced” is the large-scale expansion of the Podhalean mode throughout the Development section. While the rhapsodist seems to wander astray, the classicist subtly crafts a beautifully centered art form. The folk quality, reminiscent of Szymanowski’s last pieces, unfolds very differently for Bacewicz than for Szymanowski.

[28] As research continues, perhaps a new legacy for Bacewicz will take shape. The pejorative implications of the labels “formal,” “conservative,” and “non-innovative” may yield to an assessment of her music on its own terms, peacefully coexisting with the non-innovative music of her alphabetical neighbor, Bach. In fact, with respect to multilevel, modal structures, Bacewicz is indeed innovative. The first two measures of the Second Piano Sonata, with its vertical B octave in the bass moving to the E and to theme 1 in measure 3, anticipates the entire Development section. The Development takes the bass octave and prolongs it linearly by means of the Podhalean mode. This large-scale descent creates a remarkable middleground structure.

[29] I view the geneology in Polish music not as Bacewicz’s being a disciple of Szymanowski (just as Szymanowski was not a “disciple” of Chopin), but as a successor to the throne. During the 1950’s, Bacewicz was Poland’s leading composer, male or female. With further analysis, continued exposure and attention, Bacewicz’s music may come to be viewed in a similar light to the neoclassical work of Bartok.(15)

[30] Perhaps consensus can be reached that Bacewicz’s sonata is more “neo” than “Classical” in its use of Polish folk idioms, more rhapsodic than formulaic in its emotional content, and, at the same time, less rhapsodic and more formally structured in terms of thematic development at the middleground. The beautiful balance heard throughout many levels of the piano sonata brings an elegance of form which perfectly complements the concentrated, dramatic, virtuosic, and seemingly improvisitional quality of the piece. I like to imagine that Bacewicz, while satisfying the bureaucrats in power at the time, was able to save some individualism for herself.(16)

Ann K. McNamee

Swarthmore College

Swarthmore, PA 19081

amcname1@cc.swarthmore.edu

Footnotes

1. Rosen, Judith, Grażyna Bacewicz: Her Life and Works, Polish

Music History Series, vol. 2 (Los Angeles: University of Southern

California, 1984)

Return to text

2. In English sources, four scholars have done significant work

on Bacewicz’s music. Pioneering work was done by Judith Rosen in

“Grażyna Bacewicz: Evolution of a Composer,” as part of Musical

Woman, An International perspective, vol. 1 (Westport, CT and

London: Greenwood, 1983, pub. 1984), 105–17. In the same

publication, an article about two of Bacewicz’s seven string

quartets appears, written by Elizabeth Wood, “Grażyna Bacewicz:

Form, Syntax, Style,” 118–27. Judith Rosen authored the first

monograph in English, cited in footnote 1. Next in that series is

Thomas Adrian’s Grażyna Bacewicz: Chamber and Orchestral Music,

Polish Music History Series, vol. 3 (Los Angeles: University of

Southern California, 1985), which contains an excellent

bibliography on pages 119–21. A recent publication is Sharon

Guertin Shafer’s The Contribution of Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–

1969) to Polish Music (Lewiston, N.Y.: E. Mellen Press, 1992),

which discusses Bacewicz’s songs.

All of the above sources taken together add up to only 319

pages; research has just begun in the West.

Return to text

3. Historical Anthology of Music by Women James Briscoe, ed.

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 298–318. The two

pages preceding the piano sonata contain excellent commentary on

the piece by Adrian Thomas. Examples 1 and 2a–2d have been

reprinted by kind permission of Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne.

Another excellent two-page commentary on Bacewicz can be

found in Women and Music: A History Karin Pendle, ed.

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 197–99.

Return to text

4. If you e-mail me directly at amcname1.cc.swarthmore.edu I will

attempt to send you the six minutes of music in the FTP format.

Be forewarned that you must have at least 6 megabytes of memory

available to receive this amount of sound over the network. This

procedure is possible because of the kind permission of Indiana

University Press.

Return to text

5. Thomas, Historical Anthology of Music by Women, 298.

Return to text

6. Rosen, Charles, Sonata Forms [revised edition] (New York and

London: W. W. Norton & Co., 1988), 403.

Return to text

7. One respondent, a fifth-semester theory student, came the

closest to hearing the piece the way I do, choosing measure 65

for the beginning of the Development. That student was Roxanna

Glass, now a doctoral candidate at CUNY-Graduate Center.

Return to text

8. Rosen, Charles, 243. On the same page, Rosen also states,

“They [slow introductions] are best viewed rhythmically as large-

scale upbeats, and harmonically the dominant pedal is the most

important element in their structure—and in their emotional effect as well, as it creates a sense of something about to

happen.”

Return to text

9. Bibliographies for this relatively new direction in analyzing

non-tonal and extended tonal music can be found at the end of

Allen Forte, “New Approaches to the Linear Analysis of Music,”

Journal of the American Musicological Society 41/2 (1988): 315–

48 and Allen Forte, “Concepts of Linearity in Schoenberg’s Atonal

Music: A Study of the Op. 15 Song Cycle,” Journal of Music

Theory 36/2 (1992): 285–382.

Return to text

10. Wilson, Paul, The Music of Bela Bartok (New Haven and

London: Yale University Press, 1992). Straus, Joseph N.,

Introduction to Post-Tonal Theory (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-

Hall, 1991). van den Toorn, Pieter, The Music of Igor

Stravinsky (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1984).

Return to text

11. An especially beautiful example of an unfolded interval which

spans the entire Development section can be found in Heinrich

Schenker, Five Graphic Music Analyses (New York: Dover

Publications, Inc., 1969), 40–43. The Haydn sonata in this

example recurs as Figure 62 in Schenker’s Free Composition

trans. and ed. by Ernst Oster (New York and London: Longman Inc.,

1979), with some discussion on page 64.

Return to text

12. Talk of the tritone as “dominant” immediately brings to mind

Erno Lendvai’s axis system, as described in Bela Bartok: An

Analysis of his Music (London: Kahn & Averill, 1971). In order

to actually understand Lendvai’s ideas, one should read the

Appendix “Erno Lenvai and the Axis System” in Wilson’s book, The

Music of Bela Bartok, 203–208.

Lendvai refers to the Podhalean mode as the acoustic or

overtone scale (Lendvai, 67). Another name for this mode is

“heptatonia seconda” (Wilson, 27).

Return to text

13. Does it make any sense for Bacewicz to have structured the

Development in this way, that registral expansion is supreme?

Bacewicz was a world-class violinist, concertizing throughout

Europe. It is possible that her sensitivity to register developed

through her string playing. It is also possible that the

expansion of the bass register, so critical to solo violin music,

may have influenced her piano writing.

Return to text

14. Thomas especially dislikes the “logic of form” generality. “‘Logic of

form,’ on the other hand, is a particular and oft-repeated nonsense. As a

compositional attribute it is intrinsically indefinable, and few composers

would relish such a label when unaccompanied by an appraisal of the ideas

that create the form.” (Grażyna Bacewicz: Chamber and Orchestral Music,

117).

Return to text

15. Paul Wilson convincingly analyzes Bartok’s Piano Sonata with

several levels of pitch-class sets linked to levels of prolonged

linear motion (The Music of Bela Bartok, 55–84). An analysis of

Bacewicz’s sonata using set theory along with linear analysis is

in progress, but outside the scope of this article.

Return to text

16. I would like to thank Lee Rothfarb, Michael Marissen, and

George Huber for their help with this article.

Return to text

All of the above sources taken together add up to only 319 pages; research has just begun in the West.

Another excellent two-page commentary on Bacewicz can be found in Women and Music: A History Karin Pendle, ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 197–99.

Lendvai refers to the Podhalean mode as the acoustic or overtone scale (Lendvai, 67). Another name for this mode is “heptatonia seconda” (Wilson, 27).

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1993 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Natalie Boisvert, Cynthia Gonzales, and Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistants